PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [National Taiwan University] On: 25 September 2009

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 905688741] Publisher Psychology Press

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of Psychology

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713659663

Modernization of the Chinese Family Business

Kwang-Kuo Hwang ab

a National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan b Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Online Publication Date: 01 January 1990

To cite this Article Hwang, Kwang-Kuo(1990)'Modernization of the Chinese Family Business',International Journal of Psychology,25:3,593 — 618

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00207599008247915 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207599008247915

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

International Journal of Psychology 25 (1990) 593-618

North-Holland

593

MODERNIZATION OF THE CHINESE FAMILY

BUSINESS

Kwang-Kuo HWANG * National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

In order to study the modernization of the Chinese family business, the contrast between formal rationality and substantive rationality was used to characterize significant features of Western culture and Chincse culture respectively. A theoretical model of Chinese social behaviors as influenced by the substantive ethics of Confucianism was adopted to describe the organizational

behaviors which were frequently observed in Chinese family business. Scveral empirical studies comparing organizational climates as perceived by employees working in foreign-invested busi- ness, private business with Formal regulations, and family business were cited to support the argument that such Confucian virtues as loyalty to the organization, working hard, maintaining interpersonal harmony, ctc., are most likely to be manifested in organizations where formal regulations of Western-style management were enforced.

Despite hindrances and difficulties, modernization has been the trend of transformation of Chinese society since the end of the nine- teenth century. The modernization of the Chinese family business is but a part of the whole transformation. If we look at this issue from a broader view, the modernization of Asia, Africa, and the countries of Latin America is, in fact, the process of peoples acquiring Western civilization (Bellah 1970; Eisenstadt 1966). This is true for China.

T h e

modernization of the Chinese family business is, therefore, the process by which traditional Chinese industrial or commercial organizations model on the Western ways of management. But why is there a necessity of modernization for the Chinese family business? The ques- tion involves the essential nature of contrasts between Chinese and Western cultures. In order to discuss the question thoroughly, the basic differences between the Chinese and the Western cultures should be first mentioned.

The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Gayle Pnvettc for her help in earlier versions of this paper.

Author’s address: Kwang-Kuo Hwang, Department of Psychology, National Taiwan Univer- sity, Taipei 10764, Taiwan.

0020-7594/90/$03.50 8 1990 - Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. (North-Holland)

594 K -K. Hwang / Chinese jamit) business

It is a well-known fact that Confucianism has been the most influen- tial and lasting cultural factor in shaping social behavior of the Chinese people. The salient characteristics of traditional Chinese business organizations can be viewed

as

the results of arranging the interper- sonal relationship in the organizations according to the will of the men-in-power who are profoundly influenced by Confucian Ethics. Toelaborate this point, it will be worthwhile to mention Max Weber’s classical works on Confucianism at the beginning of this section. As a fact well known to most sociologists, the major concern in Weber’s academic career was understanding, finding, and uncovering the cult- ural factor which accounts for the rise of modem industrial capitalism in Western civilization. After questing the dialectical relationship be- tween Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism (Weber 1958), he made further attempts to explore reasons why industrial capitalism had never occurred in cultures other than Western civilization. Using the ‘ideal-type approach’ and citing materials from different dynasties of China, Weber’s book, The Religion of

China

examined the monetary system, cities and guilds, family and sib system, government and bureaucratic organizations, and law of Imperial China before the beginning of the twentieth century. According to his analysis, although there were many factors in the social structure of Imperial China unfavorable for the development of industrial capitalism, there still were positive factors such as no succession of status, the freedom of migration, education, and choice of career. Finally, it was concluded that the Chinese ethos with a core value of Confucian ethics might be the origin of all the unfavorable social structure which hindered the development of industrial capitalism in traditional China (Weber 1951; Bendix 1960).In recent years, economists have noted the rapid economic growth of

such East Asian countries

as

Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea after World War I1 (Balassa 1981; Bradford 1982; Chen 1979; Hicks and Redding 1984a,b; Little 1981; Morawetz 1977). Some soci- ologists assert that Confucian ethic has actually contributed to the promotion of economic growth in these areas (Berger 1983;Kahn

1979; Hofheinz and Calder 1982; MacFarquhar 1980), and some argue that the empirical fact of this rapid growth is a new challenge to Weber’s thesis about Confucian ethics (e.g. King 1985). However, the clarifica- tion of the complicated relationship between Confucian ethics and the economic miracle of Asian countries is beyond the scope of this article.1-1 Hwang / Chinese family business 595

It is discussed elsewhere (Hwang 1988). Here, a review of Weber’s theory about the nature of Rationalism which rose in Western civiliza- tion during the Renaissance and his criticism of Confucian ethics may help us to reveal the reason why the traditional Chinese business organization has to modernize, and the direction of its modernization. Therefore, the cultural differences between the East and the West by using Weber’s contrasting concepts of ‘formal rationality’ and ‘sub- stantive rationality’ w

i

l

l

be explained.

This is followed by a reinterpre- tation of these contrasting concepts in terms of a theoretical model of Chinese social behavior (Hwang 1987a). Finally, the characteristics of the Chinese family business and the direction of its modernization on the basis of empirical findings will be discussed.Formal rationality and substantive rationality:

a contrast between the East and the West

According to Weber, the development of modern capitalism in Europe is the result of the rise of Rationalism in Western civilization. Since the Renaissance of the sixteenth century, trends of rationalization have arisen in various fields of politics, law, economics, science, and religion in many European countries. Though there are differences in terms of their historical backgrounds, goals and speed of progress, the processes of rationalization in various fields are closely linked to each other, constitute a trend of Rationalism, and provide the necessary condition for the rise of modem industrial capitalism (Weber 1978b). This article will concentrate its discussion on the nature of Western Rationalism. In order to describe the unique and specific features of Rationalism as it emerged in Western civilization after the Renaissance, Weber made a distinction between the concept of ‘formal rationality’ and ‘substantive rationality’. Formal rationality refers to the calculabil- ity of means and procedures for achieving a particular goal, with emphasis on the value-free or value-neutral facts. On the contrary, substantive rationality refers to ‘ value of ends or goals’ in some clearly defined domains. For example, the calculability of means and proce- dures is very high in modem science, technology, and judicial or management systems, so we may say that they emphasize the impor- tance of formal rationality. In comparison to this, though magic, secret practices, and ethics might be highly valued in a traditional society, the

5% K. -A: Hwmg / Chinese family buiness

calculability of their means and procedures is very low; therefore, they possess substantive rationality but not formal rationality.

Since the Renaissance, the elites of various fields in Europe practised rational activities in various forms and thereby facilitated the rise of formal Rationalism. The rationalization in the fields of science, legal system, and administrative organizations thus created a kind of en- vironment with high predictability in which a capitalist entrepreneur can calculate accurately his or her investment and benefits; can also practise the so-called ‘rational act of calculation’ in the market to strive for the greatest possibility of profits.

This

is the reason why Weber asserted that the enhancement of formal rationality may contribute to the development of capitalism.Confucianism is, according to Weber, essentially a system of sub- stantive ethics in nature. It has nothing to do with formal rationality and is in sharp contrast to formalistic law in the modem Western world. The social decorum for regulating interpersonal interactions in traditional Chinese society is conditioned by the substantive ethics of Confucianism but not by formal rationality. In a social environment which emphasizes the value of conforming to substantive ethics, it is

very unlikely for an individual to perform economic acts on the basis of rational calculation.

This

may partially explain why it is difficult for Imperial China to develop capitalism.A theoretical model of Chinese social behavior

The rapid economic development of East Asian countries including Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea is mainly a result of their Westernization efforts. Confucian ethics imply in themselves a strong motive for pursuing achievement. Under the impact of the Western culture, some radical changes have also occurred in the social behavior of the Chinese living in these areas. In order to re-interpret Weber’s assertion about Confucian ethics and to explain the economic success of the Chinese, a model of social exchange behaviour has been proposed recently (Hwang 1987a). It describes the specific features of

Chinese social behavior as influenced by Confucian ethics and can be used to understand changes under the impact of modernization. It also defines the two parties concerned, the petitioner and the resource

K. -K. Hwang / Chinese family buriness 5 91

598 K. -K Hwang / Chinese jamily business

allocator, in a process of dynamic social interaction with heavy empha- sis placed on the relation (guanxi) between the two.

The model presupposes that under the influence of Confucian ethics, one generally classifies relationships into three categories and interacts according to different rules of social exchange:

Aflective ties: need rule. The affective tie is generally a kind of steady and long-lasting social relationship. It is also possible for an individual to use this kind of relationship as an instrument to obtain some particular social resources he needs (Lau 1981).

In Chinese society, the most important affective ties for an individ- ual are those between family members (e.g. Fried 1959; Lang 1946; Levy 1949; Yang 1988). Confucianism regards an individual’s life as the continuation of his ancestors (Hsu 1967), and his offspring’s life the continuation of his own. One of the most important goals for an individual is to do his best in continuing and making prosperous his family life. In keeping with

this

premise, a family has been regarded as a primary social unit with the function of sharing income and meeting expenditures (Shiga 1978). Before the brothers divide the family prop- erty so as to set up separate households, the principal rule for social interaction and distribution of resources within a family is the need rule. That is, every family member who has the ability to work shall d o their best and workas

hard as possible to obtain various social resources to satisfy the reasonable needs of themselves and that of their family members.Mixed ties: ‘renqing’ rule. Mixed ties mean the kind of interpersonal relationships an individual has with acquaintances outside the family including relatives, neighbors, teachers, classmates, colleagues, etc. (e.g. Fried 1969; Jacobs 1979).

This

kind of relationship is characterized by its temporal continuance and its affective component of various extent. Its temporal duration and affectional intensity depend on frequency and quality of the interaction between the two parties. A social rela- tionship of mixed ties can also be used as an instrument by anindividual to gain needed social resources.

According to Confucian ideals, the code for social interaction in mixed ties is that of harmony: one has to do one’s best to see that harmony is maintained (Hwang 1988). One has not only to make every attempt to save the other’s face, but also to put oneself in the other’s

K. -K. Hwang / Chinese/amib butiness 5 9 9

position. In ordinary times, individuals shall keep frequent contacts with people of their social networks; when any one of them encounters trouble in life, an individual shall have sympathy, think of the person, try their best to help, and do favors.

This

is what Confucius meant by generosity. Of course, the recipient shall always repay the favor with gratitude whenever the chance comes. This is the so-called renqing rule. The five cardinal ethics specified in Confucianism, such as affection between father-and-son, precedence between young and old brothers, distinction between husband and wife, trust between friends, loyalty between superior and subordinate, are mainly norms for regulating social interaction between two parties of affective or mixed ties. Viewed from Hwang’s model, to actualize these ethics in daily life is to encourage two people with any of these five relationships to interact in accordance with the need rule or the renqing rule (Hwang 1987a).Instrumental ties: equity rule. Confucianism never set up any norm for regulating social interaction between people of instrumental ties. In this kind of relationship, an individual’s motive to interact with others is to use this kind of relationship as an instrument to achieve his aims or goals, rather than to establish a long-lasting relationship with the other. The transaction between salesmen and customers or taxi drivers and passengers is an example of this kind of relationship.

The rule of social exchange for this kind of relationship is that of equity. To explain this in terms of Weber’s concept, a social act can be considered as rational only if it follows the equity rule such as market transactions (Weber 1978). In this kind of instrumental transaction, the two parties will evaluate the outcome of social exchange on the basis of a certain comparison (Homans 1961; Blau 1964; Adams 1965) involv- ing little affection.

Within the rectangle denoting guanxi (social relationship) in fig. 1, the affective ties and mixed ties are separated by a solid line, implying that it is not easy to penetrate the psychological boundary between these two kinds of relationship. That is, it is very hard for a person in a mixed tie to change his relationship with the individual to that of an affective tie. On the contrary, the instrumental ties and affective ties are divided by a dashed line, meaning that it is easier for a person to penetrate the psychological boundary between these two kinds of relationship. People of a particular instrumental tie may, by all means, try to establish a favorable relationship with others so that they may

600 K -I Hwang / Chinese jarnib business

change their relationship into a mixed tie and interact with each other according to the renqing rule.

A reinterpretation of Weber‘s thesis

Weber’s thesis about Confucianism can be reinterpreted in terms of

the afore-mentioned theoretical model. The economic miracle of East

Asia after World

War

I1 can be explained accordingly. Meanwhile, the same model can also be used to illustrate the direction of moderniza- tion of the Chinese family business. Before the beginning of the century, China, as Weber had observed, was deeply influenced by Confucianism, its major way of economic production was that of agriculture. In the traditional Chinese agricultural society, the family is the basic social unit and the center of an individual’s life. It serves the functions of satisfying an individual’s needs for living, education, recreation, work, religion, and so on (Lang 1946; Levy 1949; Winch . 1966). Apart from family members, the persons that an individual makes contacts with in ordinary life are neighbors, relatives, or close friends of stable relationship. An individual must follow Confucian ethics, specifically, the need rule or the renqing rule, in dealing with people within his social network.The higher a man’s position is and the more power he holds, the more respect for his ‘face’ he might obtain from his fellowmen, and the more frequently people may give him favors. In this kind of cultural background, if an individual has to make social dealings with people outside his social network, it is advantageous to change a relationship of instrumental tie into one of mixed tie by receiving and giving gifts, so that he may interact according to the renqing rule.

This

becomes, then, what Francis Hsu called pseudo-kinship ties (Hsu 1971). Inter- acting with family members in terms of the need rule, or interacting with acquaintances in terms of the renqing rule, one can expect a reciprocal relation on a favor-for-favor basis, but one cannot predict when or how the reciprocation will happen. Therefore this kind ofsocial exchange can be regarded as non-calculating behavior in contrast to Weber’s concept of the rational act. With a non-calculating attitude, an individual has a tendency of conformity in various social situations. While it may help to maintain harmony within a group, it discourages

K -K Hwang / Chinese family buriness 601

the development of Rationalism in the European tradition of the Renaissance.

Weber observed that the Chinese social behaviors in social organiza- tions before the 19th century were controlled and regulated by the substantial ethics of Confucianism, but not a formal system of law that treats everyone as an individual with equal rights. In such a cultural environment, an individual cannot deal with others with the so-called ‘rational act’ in a calculated manner. He therefore concluded that Confucian thoughts might be a hindrance to the development of capitalism in China. To explain from the theoretical model described in the previous section, Confucian ethics encourage an individual to deal with his family members in terms of the need rule and to deal with other people in his social network in terms of the renqing rule. Yet, it says nothing about how to manage social interaction with strangers in situations like marketing transactions on the basis of the equity rule. Moreover, there have been few opportunities available for this kind of transaction in the traditional Chinese society. Thus Weber drew con- clusion about Confucianism.

If Weber was right, how can one explain the economic miracle of the East-Asian countries after World War II? In order to answer this question, one has to analyze the content and structure of Confucianism first. Even though Confucianism does not contain any ingredient of formal rationality which is very necessary for the development of industrial capitalism, it implies a strong achievement motive in the

renduo (way of humanity) it celebrates (Hwang 1988). It encourages an individual to use the method of hard work to obtain and to save various social resources to satisfy the need of his family members. It also expects an intellectual to study with diligence, and to pursue achievement in order to enhance glory (or face) for himself and for the group he belongs to. Meanwhile, it endows the intellectuals with a mission to benefit the world with Dao and expects them to do things beneficial to society, the state, or the world.

Before the overturn of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the most important ladder of upward mobility for intellectuals in China was the mastery of

the Confucian rendao in order to pass the examination and obtain degrees for civil service. The Confucian rendao was certainly helpful in maintaining the social order of traditional society, but it has nothing to do with the development of formal rationality. Since the nineteenth century when the East Asian countries came in close contact with the

602 K -K Hwang / Chinese jomii) buriness

Western modem civilization, they began to send students abroad to learn scientific knowledge and the Western systems. The students, with their strong achievement motive and the spirit of diligence inherited from their tradition, studied hard in the West and returned with the mission of 'benefiting the world with &o' to serve their home coun- tries (Hwang 1988). They implanted the seeds of formal rationality in the Eastern societies.

Thus, one may sum up the difference between the processes of modernization in the East and West: the modernization of the West envolved from the inner part of the cultural system. It is the result of

the rise of Rationalism after the Renaissance. The modernization of the East is imported from outside: the elites of the Eastern society con- structed in their home society the structure of judicial and administra- tive system with formal rationality on the basis of Western civilization.

This

enables the Asian people with strong work motivation to use the technology of production imported form the West to pursue wealth for their families. In other words, the modernization of Western society evolved step by step from the inner part of its cultural structure, while the modernization of Eastern society proceeded the other way around, i.e., it was imported from outside, and penetrated from the top to the bottom of the society.The development of family business

As mentioned in a previous section, the modernization of the East- ern society is penetrating gradually from the top to the bottom. After the end of World War 11, the governments of Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Korea followed the capitalistic policy of economic devel- opment. They worked one after another

on

the construction of legal and administrative systems that are aimed to stimulate economic growth.This

encourages the entrepreneurs to set up firms, utilize the scientific technology imported from the West for industrial production, and sell their products to pursue benefits. But, viewed from the point of organizational psychology, most Asian entrepreneurs are still under the influence of Confucianism in managing their business. The situation may be explained by using the theoretical model of fig. 1.In managing

their

business, East Asian entrepreneurs still have the tendency to assign family members or persons of close relationships toK . -K. Hwang / Chinese family bwiness 603

orgmiution

I

hiring outsidersI

sepuatmg management unifeation of ownership

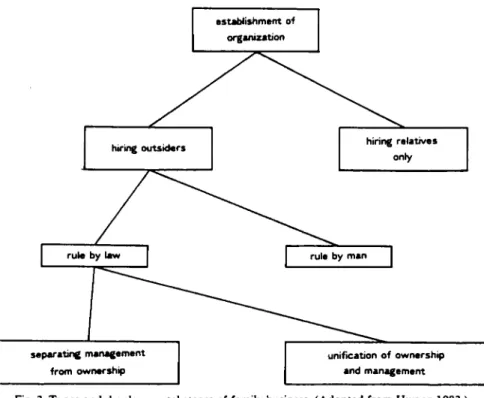

and management Fig. 2. Types and developmental stages of family business. (Adopted from Hwang 1983.)

occupy key posts in their business, and dealing with them according to the need rule or the renqing rule. Meanwhile, the transformation of the East Asian society from an agricultural to an industrial and commercial one gave owners of businesses more opportunities of establishing instrumental relationships with people outside the business organiza- tion, interacting with outside people according to the calculating equity rule to pursue the greatest benefits, and performing the vital rational economic act.

Nevertheless, constructing and managing business organizations in

modem society on the basis of Confucianism may lead to some organizational defects. When the organization is s t i l l on a small scale, the defects might be obscure and hard to detect. But, when its scale enlarges to a certain degree, many problems may emerge. Fig. 2 indicates the different stages of organizational development and vari- ous types of family business as it is found in Chinese society (Hwang

1983).

604 K - K Hwang / Chinesefamily business

In fig. 2, the first type of family business hires exclusively family members. In Chinese society, there are many small-scale food shops, drugstores, stationery stores and stores of daily necessities. These stores are mostly owned by families: the head of the family is the shopkeeper while the employees are mostly family members. Some heads of fami- lies may be good at certain skills, for example, watch-repairing, lock-re- pairing, carving, tailoring, car-repairing and the like. They may use their house

as

a store or a factory and work as master with help from the other family members.This

is the most typical family business. The rule of production and distribution of resource within the business is the need rule, namely, ‘Do what one can, and take what one needs.’ Every member has to do their best in their work and obtains the necessary resources for their life, not being concerned about getting reward in proportion to effort.When the scale of the business increases, the business may start hiring non-family members to join the work force. When the business organization is still on a small scale, the business activities are relatively simple, the owner may have the absolute power of business manage- ment, assigning his family members to key posts to help him operate the organization. Thus it manifests the typical characteristics of family business. Yet, when it continues to grow, the number of non-family members increases. The increase in business activities and the division of labor urge the owner to make the choice of adopting a Western style of management and setting up regulations for operating the business organization, or following the old way of administration by depending on family members. In other words, he has to choose between the practices of rule-by-man or rule-by-law. The choice has a significant implication for the modernization of the family business. If the owner decides to give up the old practice of rule-by-man, and follows the management of rule-by-law, he has to pay special attention to the equity rule in setting up polices for regulating organizational operation. He has to assess the duty and authority assigned to each post of the organization, design an objective method for evaluating job perfor- mance, and allocate fair rewards to each individual in proportion to their contributions to the organization. To view this from the model in fig. 1, when the business organization establishes regulations and requires employees to follow them closely, the instrumental relationship then outweighs the relationship of mixed ties and individuals in the organization tend to utilize the equity rule in dealing with other people.

K. -K Hwang / Chinese family buriness 605

However, in dealing with matters irrelevant to business, the owner might still be influenced by Confucianism. In other words, the individ- ual has to establish proper psychological compartmentalization be- tween personal affairs and business (Hwang 1987a): business is busi- ness, and the renqing rule is applicable to personal affairs only. Put in Weber’s concepts, the establishment of formal rules in an organization enables an individual with substantial ethics of Confucianism to un- dergo the rational act of calculation to pursue the greatest advantages for oneself.

Only when the organization has established formal rules of manage- ment can it lead to the division of power between ownership and administration, and it may employ experts in diverse fields to help with the operation of business. On the contrary, if the business fails to become formalized in its rules of management, managerial practices as performed by managers of each department might be influenced to a great extent by traditional culture. There might be a tendency to use the need rule or the renqing rule in dealing with other persons in the organization and thereby manifest the specific organizational pattern of the family business.

The organizational pattern of family business

Many social scientists who had studied the organizational pattern of

business in Chinese societies found that the organizational behavior of Chinese family business in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South East Asian regions has been influenced to a certain extent by Confucian ethics (Redding and Wong 1986); namely, the owner hardly values the establishment of formal rules of management, and tends to deal with his subordinates according to the need rule or the renqing rule. In other words, the organizational pattern of family business observed in these areas can be viewed as the logical consequence of managing the organization and dealing with the organizational members in terms of Confucian ethics. Thus we can examine the organizational pattern of the family business from the aspect of organizational structure and organizational processes, and trace the cultural causes of such organiza- tional pattern to Confucian ethics.

606 K - K Hwang / Chinese family h i n e s s

The organizational structure

The so-called organizational structure means stable relationships among individuals who play different roles in the work situation. Generally speaking, the organizational structure of family business can be described from the following aspects:

Family-ownedproperty. Confucian ethics regards the family as a basic social unit of shared income and expenditure (Shiga 1978). Every member in this unit has to give a great portion of their income to the family and they may take what they need from the family.

All

thefamily members regard the balance as their shared property which is controlled by the househead. With this concept, the owner of a family business usually views the enterprise as a family-owned property and would not like to share the ownership with other non-family members (Lau 1981). As a consequence, the ownership and the power of mana- gement in the family business is controlled by one single family.

This

is truewith

businesses in Chinese societies in South East Asia (Deyo1983; Lim 1983; Redding and Hicks 1983), also with business organiza-

tions in Taiwan. In 1978, the China Credit Agency in Taipei made an

intensive study of the organizational structure of one hundred top entrepreneural groups in Taiwan. The final report said that:

‘A closely knit family is the most characteristic social system in China. Our enterprises are mostly based on the family organization and gradually develop into a consortium. With few exceptions. the present one hundred consortiums demonstrate the characteristics of family business, while consortiums of other types are in small number. Therefore, in evaluating the nature of a consortium, it will make more sense to assess the substantial power of influence from the owner‘s family. This is especially true with the top one hundred consortiums in Taiwan.’ (China Credit

Information Service 1978)

Even the one hundred top consortiums in Taiwan demonstrate such a property, and needless to say, the enterprises of smaller scale do also. In the past, many institutions conducted survey research on organiza- tional patterns of enterprises in Taiwan. The findings repeatedly showed that most enterprises of small or medium scale possess the characteris- tics of family business: the owner monopolizes the power of supervising production, sales, and business administration; he knows very little about modem management, and cannot make use of the Western ways

K -K Hwang / Chinese family business 607

of management (China Productivity Center 1974; Sung 1979; Tseng

1978).

Small-scale business. Most family businesses in Chinese society are of rather small scale, and the number of employees hired is very Limited. For instance, in 1981, eighty-eight percent of Hong Kong manufactur- ing factories hired fewer than fifty employees each (Redding and Wong

1986). According to a general survey on industrial and commercial

sectors of Taiwan in 1986, a total of 712 state-owned enterprises hired

387,389 employees, with an average of 544. While 606,185 private enterprises hired 4,766,943 employees, ninety-eight percent of them hired fewer than fifty employees. Each private enterprise on the aver- age hired only eight employees (Ministry of Administration 1989).

Simple structure. The family business is not only small in size but also simple in structure. Most family businesses concentrate their functions on either production, sales, or service. Only relatively few businesses of

a larger scale set up different functional departments. But even such larger business may have no formal system of regulation, or have only a rough and simple one. The functions of each department in the organization are not clearly specified; the duty of each position is not well defined; and the working procedures are not standardized (Pugh

and Redding, 1985). The employee has to follow the orders from the owner-manager and do various tasks

in

different fields (King and Leung 1975).Nepotism. The formal system of regulations has the function of pre- venting individuals in authority from abusing power (Crozier 1964). In

an organization where the regulatory system is not specified, the owner-manager

has

control of the whole business and makes decisionby himself. By the time the scale of organization grows to the extent that the business activities are beyond his control, he w i l l usually appoint family members or relatives to key posts of the organization to help

him to

deal with the daily management (Lai 1978; Low 1973; Yong 1973). The result is that the family business often turns out to bea relation-oriented social unit: the boss is both the owner and the manager, the high positions are occupied by his family members or relatives; the intermediate ones are assigned to employees with long working experience in the organization or to those with certain special

608 K - K Hwang / Chinese family bwiness

skill and knowledge about technology of production. As for those who are laborers and who had no personal relationship with the owner, they are offered only basic positions. Thus in the business organization, the owner-manager has in his hand most social resources and tends to deal with people differently according to their personal relationships with him.

The organizational procedures

The organizational procedures in family business can be regarded as

the process by which the owner-manager deals with people differently according to his relationships with them. The characteristics of such organizational procedures can be understood from the following aspects:

Leadership style. The manager of family business usually assumes an authoritarian leadership style (King and Leung 1975; Redding and Casey 1976; Silin 1976). To protect and maintain his position of authority, he usually controls all the information in guiding his organi- zation, permitting an employee to know only part of the information about the operation of the organization. Information thus withheld, employees have to ask for his opinions in almost every important decision and thus have to, so to speak, yield to the boss (Silin 1976). As perceived by the members of the organization, there exists a rather large power distance between owner and employees (Hofstede 1980). Decision-making procedures. Because most of the owner-managers re- gard the family business as their personal property and decisions about major goals in the business are kept confidential, important matters are scarcely discussed with non-family members, especially the financial status and possibilities of obtaining benefits. Very often, many im-

portant policies are made at family conferences

(Mok

1973; Reddingand Wong 1986). Employees who are not family members have the obligation to follow, but have no chance to participate in decision making.

The controlprocedures. Due to the lack of a formal job description for each position, it is very difficult for the manager to evaluate employees’ performance on the basis of certain objective criteria. Because of this,

K. - K. Hwang / Chinese family k i n e s s 609

the owner-manager of the Chinese family business tends to emphasize ‘loyalty’ from employees and to evaluate them on the basis of his global impression about their general performance. To those who show

high loyalty and who seem to have done their best work, the boss must in turn give reward with an extra annual bonus or ‘small red envelopes’. By the same token, those who show ‘inadequate’ behavior or ‘dis- loyalty’ in daily work may get less reward.

It should be noted, however, that this under-the-table give-and-take usually exists between the owner-manager and staff members, espe- cially those with special skills and technological knowledge, and those of outstanding talents on whom the owner has to rely for managerial matters. They are capable and indispensable for the business. In fig. 1, this process can be regarded as an example of the owner-manager interacting with people of mixed ties on the basis of the renqing rule. Yet, in treating those employees of average ability or those who have no affective bond with the owner, the family business tends to keep the salary as low as possible, in relation to the payment level of the labor market. This becomes, then, an example of using the equity rule to deal with people of instrumental ties. In this kind of relationship, the employer always adopts a calculating manner in his personnel control and management, and is concerned with neither renqing nor mientze,

but only benefit (Wilson and Pusey 1982).

The modernization of family business

The characteristics mentioned above are typical organizational pat- terns of the family business. It shall be emphasized that the family business is not the only type of enterprise that exists in Chinese society. For instance, Negandhi (1973) conducted a large-scale research to compare the organizations and practices of management of nine US subsidiaries, seven Japanese subsidiaries and eleven local firms (Negandhi 1973). The contrasts between US subsidiaries and local firms as shown in table 1 are especially noticeable. We can see from table 1 that local firms have only medium- to short-range plans. The policies of the enterprises are not formally stated, so that they cannot be utilized as guidelines and control measures. This kind of enterprise seldom hires specialized staff; authority for each position is not clearly defined. The owner tends to assume a paternalistic-autocratic type of

610 K -K Hwang / Chinese famib buriness

Table 1

Profiles of management practices and effectiveness of the U.S. subsidiary, and the local firm.

Management US subsidiary Local firm

practices and effectiveness

Planning Long range

( 5 to 10 years)

Medium to short range

(1 to 2 yean)

Policy-making

Other control devias used

Organizational set-up Grouping of activities Number of departments

Use of specialized staff Use of service department Authority definition Degree of decentralization Leadership style

Trust and confidence in sub-ordinates Managers’ attitudes

toward leadership style and delegation

Formally stated, utilized as guidelines and control measures Quality control, cost and budgetary control. Maintenance. Setting of standards On functional-area basis 5 to 7 Some Considerable Clear High Consultative High

Would prefer autocratic style. Authority should be held tight at the top Manpower management practices

Manpower policies Formally stated Organization of Not separate unit

Job evaluation Done

Development of selection Formally done Training programs

personnel dept.

and promotion criteria

Only for the blue-collar employees

Formally not stated. Not utilized as guidelines and control measures Some cost control Some quality control. Some maintenance On functional-area basis 5 to 7 None Some Unclear L O W Paternalistic-autocratic L O W Would prefer consulative type Not stated Not separate unit

Done by very few Done by some Only for the blue-collar employees

K.-K Hwang / Chinese family business 611

Table 1 (continued)

Management US subsidiary Local fm

practices and effectiveness

Compensation and motivation Monetary only Monetary only Management effectiveness

Employees morale High Moderate

Absenteeism LOW Low

Turnover High High

Productivity High High

Ability to attract trained Able to do so

personnel

Somewhat able to do so

Interdepartmental rela tionships

Very cooperative Somewhat cooperative

Executives' perception of Systems optimization Sub-systems optimization as an important goal

the firms overall objectives

as an important goal

Utilization of high-level Effectively utilized Moderate to poor

manpower utilization

Adapting to Able to adapt without Able to adapt with environmental changes much difficulty considerable difficulty Growth in sales Phenomenal Considerable to modest Adopted from Ncgandlu 1973: 125-127.

leadership in managing his organization; he has relatively low trust and confidence in his subordinates, and delegation of power in the organi- zation is very limited. Moreover, man power policies are not formally stated, the criteria for personnel selection and promotion is developed by some staff members, and the tasks of job evaluation are done by very few. Therefore, it is comparatively difficult for this type of organization to attract trained personnel. The utilization of high-level manpower is moderately poor, executives tend to emphasize the irnpor- tance of sub-system goals instead of the firm's overall objectives, and interdepartmental cooperation may frequently have troubles. Thus the enterprise may face considerable difficulty in adopting to environmen- tal changes.

612 K. -K. Hwang / Chinese family business

In contrast to this, US subsidiaries usually have long-range plans. The policies of the enterprise are formally stated and utilized as guidelines to establish various standards for controlling quality, cost, budget, and maintenance. They prefer to hire some specialized staff to

serve as managers, and usually have considerable use of a service department. The authority and duty for every post in the organization are clearly defined, and the extent of decentralization is quite high. The managers have much trust and confidence in subordinates and tend to

adopt a consultative type of leadership. So far as manpower manage- ment practices are concerned, policies are formally stated, the criteria for personnel selection, job evaluation, and promotion are formally established, and all related tasks are executed accordingly and thor- oughly. The employees’ working morale is relatively high, and the organizations of this type are able to attract trained personnel. The executives tend to perceive the optimization of the firm’s overall objectives as an important goal, and interdepartmental relationships tend to be very positive resulting in a high degree of cooperation. The high-level manpower is effectively utilized, and the organization is able to adapt to environmental changes without much difficulty.

The contrasts between these two types of organization can be regarded as the contrasts of different extents of formal rationality implied in the organizational practices of two kinds of enterprises. Stated more precisely, when the Western enterprises set up subsidiaries in Chinese society, they tend to implant the Western ways of business administration from the main company which emphasize formal rules and standards for regulation and management, and make some neces- sary adjustments as required by the local socio-cultural environment. They look upon equity rules as the basic principle for resource allo- cation in the organization, therefore, the system of job descriptions is clearly defined, the criteria for personnel selection and promotion are established, and the evaluation of job performance by employees is

frequently made. In order to raise the employees’ working morale, the value of distributive justice is extraordinarily emphasized

-

each indi- vidual is rewarded in proportion to their contribution to the organiza- tion. In other words, this type of enterprise is characterized by a system of regulatory rules with a high level of formal rationality, which enables the Chinese employees who are deeply influenced by Confucian ethics to utilize such traditional virtues as diligence and respect for superiors to pursue various resources for themselves and their families. There-L -K. Hwong / Chinese family business 613

fore, this type of organization is more attractive even to the trained personnel; the employees’ working morale is higher, and the interde- partmental cooperation is better.

In comparison to US subsidiaries, the local firms underestimate the importance of the formal regulatory system and show the characteristic deficiency of the typical family business as discussed in the previous section. Stated in Weber’s concepts, the local firms emphasize the importance of substantial rationality, but disregard the value of formal rationality.

However, it should be noted that in Negandhi’s research, he classi- fied local firms as a homogenous group. In fact, as indicated in fig. 2,

local firms could be further sub-divided into several categories accord- ing to their stages of development. More precisely, some owners of enterprises who have been trained in Western ways of business admin- istration might apply what they have acquired in managing their enterprises. In addition to this, when the scale of an enterprise develops to such an extent as to go beyond the manager’s span of control, he may try to set up an administrative system of formal rationality in the organization. As a matter of fact, once a local firm adopts a complete system of formal regulation, the employees who have been socialized with Confucian ethics might behave in the same way as they have in an American-invested enterprise. If this is the case, the organizational patterns as perceived by staff members of these two types of enterprise must be very similar to each other. In order to test this hypothesis, I

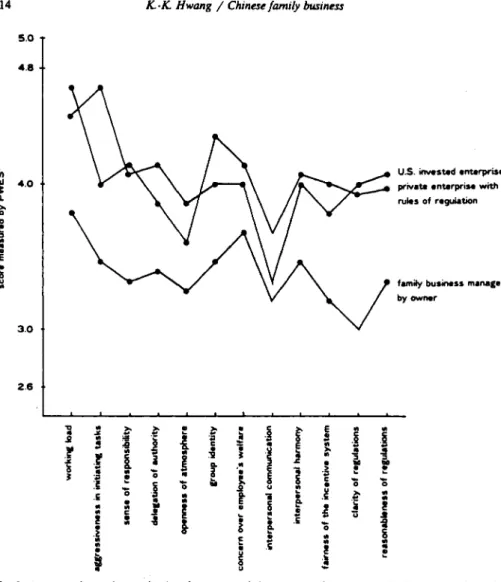

conducted an empirical research entitled ‘Business organizational pat- terns and employees working morale in Taiwan’ (Hwang 1983). It sampled 21 US-invested enterprises, 48 family business, and 35 private enterprises with formal regulatory rules. A scale for measuring the ‘Perception of Working Environment’ was developed and used to measure the organizational patterns of the enterprises as perceived by the employees. The results are shown in fig. 3.

It can be seen that there is no significant difference between Ameri- can-invested enterprises and local private enterprises with formal regu- lations in such aspects as clearity of regulations, reasonableness of regulations, fairness of the incentive system; but these two types of enterprise are functionally better than family business in these aspects. In other words, once the local enterprise adopts the Western ways of management, the formal rationality as implied in its regulation system

is hardly different from that of American-invested enterprises. Simi-

614 5.0 4.8 in n t $ 4.0 h a 0 m E ir :: 3.0 2.6

K.-K Hwang / Chinese family burinrss

us. mstd rnurprbr p ~ a t . r n u r p r w wrth r u k a of rrguhmn

family burmrr managed by ownor

Fig. 3. A comparison of organizational patterns of three types of enterprises in Taiwan. (Adapted from Hwang 1983.)

PWES: Perception of Working Environment Scale.

larly, in such aspects as work demands, delegation of authority, con- cerns about employees’ welfare, American-invested enterprises and private enterprises

with

formal regulations are also superior to family business. More importantly, when the aspects of aggressiveness in initiating tasks, sense of responsibility, open atmosphere, interpersonal harmony, interpersonal communication, group identity are taken into consideration, private enterprises are similar to American-invested en-1 -K. Hwang / Chinese farnib bwiness 615

terprises, and both are better than the family business. Thus, it may be concluded that only in a modernized organization, which emphasizes formal rationality in its regulations, can the Confucian virtues such as loyalty (group identity), diligence (aggressiveness in initiating tasks), sincerity (open atmosphere), and harmony (of interpersonal relation- ships) be developed to a relatively large extent.

Conclusion

In this brief thesis, Weber’s concepts have been first reviewed to sharpen the contrasts between cultures of the East and the West, and the nature of the modernization of the East Asian societies illustrated from a theoretical model. Then, on the basis of the characteristic features of Chinese family business, it has been pointed out that the direction of the modernization of family business should be the trans- plantation of the Western ways of business administration, namely, setting up a regulatory system of formal rationality which enables employees to actualize such traditional virtues of Confucianism as loyalty, sincerity, diligence and harmony. Finally, empirical findings have been presented to substantiate the validity of such a conceptuali- zation.

It should be emphasized that the family business is just one kind of organization in contemporary Chinese society. In the Chinese society, there exist many other kinds of political, economic, educational and social organizations. In these organizations, the Chinese who are in- fluenced by Confucian ethics may still follow the rules of social exchange as specified in the stated theoretical model in dealing with people of different relationships with them, and thus show the organi- zational patterns to be very similar to the family business as described in previous sections. While a sharp contrast between cultures of the East and the West has been adopted to define the direction of the modernization of Chinese family business, this general direction seems

to be the one that other types of Chinese social organization shall also adopt on their way to modernization.

References

Adams, J.S., 1965. ‘Inequity in social exchange’. In: L. Berkowitz (ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press. 267-299.

616 K. -K. Hwmg / Chinese family buiness

Balassa, B.A., 1981. The newly industrializing countries in the world economy. New York: Bellah, R.N., 1970. Tokugawa religion. Bostoa MA: Beacon Prcss.

Ben& R, 1960. Max Weber: An intellectual portrait. New York: Doubleday. Berger. P.L.. 1983. Secularization: West and East. Unpublished manuscript.

Blau, P.M., 1964. Exchange and power in social psychology. New York: Academic Press. pp. Bradford, C.I.. 1982. ‘The rise of the NlCs as exporters on a global scale’. In: L Turner and N. McMullen (eds.), The newly industrializing countries: Trade and adjustment. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Chen, Edward K.Y., 1979. Hyper-growth in Asian economics: A comparative study of Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. New York: Holmes & Meicr Publishers. China Credit Information SCMce, 1978. Business groups in Taiwan (in Chinese).

China Productivity Center, 1974. A sampling survey on the management of small- and middle-scale enterprises. China Productivity (in Chinest), 1-5.

Chou. Y.H., 1984. ‘The planning and control activities in large-scale enterprises of Taiwan’. In: K.S. Yang, K.K. Hwang and CJ. Chuang (eds.), Proceedings of the conference on Chinese ways of management (in Chinese). Taipei: Nation1 Taiwan University and China Daily. Pergamon Press.

267-299,

Crozier, M.. 1964. The bureaucratic phenomenon. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. &yo, F.C., 1983. ‘Chinese management practices and work commitment in comparative perspec-

tive’. In: L.A.P. Gosling and L.Y.C. Lim The Chinese in Southeast Asia: Vol. 11. Identity. culture and polities. Singapore: Manuen Asia. pp. 215-230.

Eiscnstadt, S.N., 1966. Modernization: Protest and change. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall. Fairbank, J.K. and EO. Reischauer, 1973. China: Tradition and transformation. New York:

Houghton Mifflin.

Fried, M.H.. 1959. ‘The family in China: The People’s Republic’. In: R.N. Anshen (cd.), The family: Its function and destiny (rev. ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 146-66.

Fried, M.H., 1%9. The fabric of Chinese society: A study of the social life of a Chinese county scat. New York: Octagon Books.

Hicks, G.L. and S.G. Redding, 1984a The story of the East Asian ‘economic miracle’. Part one: Economic theory be dammed! Euro-Asia Businas Review 2(3). 24-32.

Hicks, G.L. and S.G. Redding, 1984b. The story of the East Asia ‘economic miracle’. Part two: The culture connection. Euro-Asia Business Review 2(4), 18-22.

Hofheinz. R. and K.E. Calder, 1982. Eastasia edge. New York: Basic Books. Hofstede, G., 1980. Culture’s consequences. London: Sage Publications.

Homans, G.C.. 1%1. Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt, Bruce & World. Hsu, F.L.K., 1967. Under the ancestor’s shadow. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hsu, F.L.K.. 1971. Psychological homeostasis and jen: Conceptual tools for advancing psychologi- Hwang, K.K, 1983. Business organizational patterns and employe’s working morale in Taiwan

(in Chinese). Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academic Sinica 56. 145-193.

Hwang, K.K., 1986. Dao and the transformative power of Confucianism: A theory of East Asian modernization. International Alumni Association. East-West Center, Honolulu, HI, Working Paper no. 8.

Hwang, K.K., 1987a. Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology (97Y.944-974.

Hwang, KK., 1987b. Confucian tradition and motives for studying abroad and returning home. XVI Pacific Science Congress, Seoul, Korea

Hwang, K.K., 1988. Confucianism and East Asian modernization (in Chinese). Taipei: Chu-liu Book Co.

cal anthropology. American Anthropologist 73,2344.

K.-K. Hwang / Chinesejumily business 617

Jacobs, J.B., 1979. A preliminary model of particularistic ties in Chinese political alliances: Kahn, H., 1979. World economic development: 1979 and beyond. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. King, A.Y.C.. 1985. Confucian ethics and economic development: A re-examination of Max Weber’s thesis. Proceedings of the conference on modernization and Chinese culture (in C h i n e ) . Hong Kong: Faculty of Social Science and Institute of Social Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 133-145.

King, A.Y.C. and D.H.K. Leun& 1975. The Chinese touch in small industrial organizations (occasional paper). Social Research Center, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Lai, P.W.H., 1978. Nepotism and management in Hong Kong. Unpublished MS dissertation, University of Hong Kong.

Lang, 0,. 1946. Chinese family and society. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lau, S.K., 1981. Chinese familism in an urban-industrial setting: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Marriage and the Family 30. 977-992.

Levy, M.J. Jr., 1949. The family revolution in modern China Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Li, C., 1979. An empirical study on the functions of labour market in Taiwan area. Proceedings of the conference on Human Resources on Taiwan (in Chinese). Nankang: Institute of economy, Academic Sinica. pp. 935-990.

Lim, L.Y.C. (at), 1983. The Chinese in Southeast Asia: Vol.11. Identity, culture and polities. Singapore: Marwen Asia.

Little, I.M.D., 1981. ‘The experience and cause of rapid labour- intensive development in Korea, Taiwan province. Hong Kong and Singapore; and the possibilities of emulation’. In: E. Lee

(ed.), Exporcd industrialization and development. Geneva: International Labour Office. Low, N.K., 1973. Nepotism in industries: A comparative study of sixty C h i n e modern and

traditional industrial enterprises. Unpublished bachelcr’s thesis, University of Singapore. MacFarquhar, Roderick. 1980. The postConfucian challenge. The Economist 9 67-72. Ministry of Administration, 1989. The committee on industrial and commercial censuses of

Taiwan-Fukien district of the Republic of China The report of 1986 industrial and commer- cial census of Taiwan-Fukien district of the Republic of China, Vol. 1. General Report. Mok, V., 1973. The organization and management of factories in Kwun Tong (occasional paper).

Social Research Centre, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Morawctr D., 1977. Twenty-five years of economic development: 1955 to 1975. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

Negandhi, A.R.. 1973. Management and economic development: The case of Taiwan. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Pugh, D.S. and S.G. Redding, 1985. A comparative study of the structure and context of Chinese

businesses in Hong Kong. Paper presented at the Association of Teachers of Management Research Conference, Ashridge, England.

Redding. S.G. and T.W. Cascy, 1976. ‘Managerial beliefs among Asian managers’. In: R L . Taylor, M.J. OConnell, R A . Zawacki and D.D. Warwick (cds.), Proceedings of the Academy

of Management 36th Annual Meeting. Kansas City: Academy of Management. pp. 351-356. Redding, S.G. and G.L. Hicks, 1983. Culture, causation and Chinese management. Mong Kwok

Ping Management Data Bank Working Paper, Department of Management Studies, University of Hong Kong.

Redding, S.G. and G.Y.Y. Won& 1986. ‘The psychology of Chinese organizational behaviour’. In: M.H. Bond (ed.), The psychology of Chinese people. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. pp. 267 - 295.

Shiga, Shuzo, 1978. ‘Family property and the law of inheritance in traditional China’. In: D.C. Buxbaum (ed.), Chinese family law and social change: An historical and comparative penpec- tivc. Seattle. WA: University of Washington Press. pp. 109-150.

Kau-ching and Kuan-hsi in rural Taiwanese township. China Quarterly 78, 232-237.

618 K.-K Hwang / Chinese fami(v k i n e s s

Silin, R, 1976. Leadership and values. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

.Sun& Y.H.. 1979. A comparative study on the administrative behaviours of small- and middle-scale

enterprises in Taiwan area (in Chinese). Master Thcsis, College of Law, National Taiwan University.

T m & T.Y., 1978. A study on the administrative system of small- and middle-scale enterprises in Taiwan (in Chinese). Master Thesis. Graduate School of Public Administration, National Chcngchi University.

Weber. M.. 1951. The religion of China (trans. by H. H. Gerth). Glcncoe, NY: The Free Press. Weber, M., 1958. The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism (trans. by T. Parsons). New

York: Scribner‘s.

Wcber, M., 1978a. Economy and society, edited by G. Roth and C. Wittich, 2 Vols. Berkeley, CA: University of California

Wcber, M., 1978b. ‘The origins of industrial capitalism in Europa’. In: M. Weber: Selections in translation, Edited by W.G. Runciman, translated by E Mattews. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 331-340.

Wilson, R.W. and A.W. Pusey. 1982. ‘Achievement motivation and small business relationship patterns in Chinese society’. In: S.L. GreenblatS R.W. Wilson and A.A. Wilson (4s.). Social interaction in Chinese Society. New York: Praeger.

Winch, R.F.. 1966. The modem family (2nd 4.). New York: Holt. Rinhart and Winston. Yan& C.F., 1988. ‘Familism and development: An examination of the role of family in contem-

porary China Mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan’. In: D. Sinha and H.S.R. Kao (eds.), Social

values and development: Asian perspectives. New Dclhi: Sage Publications.

Yon& H.L., 1973. The practice of nepotism: A study of sixty Chinese commercial f m s in Singapore. Unpublished bachelor‘s thesis. University of Singapore.

Afin d’ttudier la modemisation de I’entrcprise familialc chinoise. le contraste entre la rationalit6 formelle et la rationalitt substantielle a t t t utilisc pour caracttriser la aspects significatifs des cultures Occidentalc et Chinoise. respectivemcnt. Un mod& thbrique des comportments sociaux chinois. tel qu’influend par l’tthiquc substantielle du Confucianismc, a ttt adopt6 pour dkrirc les comportments organi~atio~eh qui ttaient fr&uemment observb d a m I’entreprise familiale chinoise. Plusieurs ttudes empinqua comparant les climats organisationneh pequs par Ics employb d‘mtreprises Ctrangkres, d’entrcprisa privceS rtglemmtks ct d’entreprises familides sont mentionntes pour appuyer I’argument que les vertus Confuctennes, comme la loyautt B I’entrcpnse. le dur labeur, le maintien de I’harmonie intcrpmonnclle, etc. vont probablement se manifester davantage dans laentreprises qui sont rkglementks formellcment dans une adminis- tration de type Occidental.