新加坡、香港及臺灣外國勞動力移民政策之分析 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) An Analysis of Foreign Labor Migration Policies: Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. 研究生:邱曉蘋. Student: Chiu Hsiao-Ping. 指導教授:冷則剛. Advisor: Leng Tse-Kang. 國立政治大學 治. 政. 大. 學. ‧ 國. 立 亞太研究英語碩士學位學程 碩士論文. ‧. Nat. io. sit. y. A Thesis. er. Submitted to International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies. al. n. v i n C hChengchi University National engchi U. In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master in Taiwan Studies. 中華民國 102 年 7 月 July 2013.

(3) Abstract Under the trend of globalization, transnational migration has already become a common phenomenon. For fear that foreigners would pressure Taiwan’s labor market, the Taiwanese immigration policy has set up many restrictions on introducing economic migrants. However, in order to resolve the problem of brain drain and to attract more foreign talents to Taiwan, the government has started to review its immigration policies and has undertaken to loosen related regulations. On the other hand, with the improvement on the cross-strait relationship, the. 政 治 大. government has also released regulations to allow more mainland Chinese coming. 立. to Taiwan. This study adopts qualitative method, comparative case study analysis,. ‧ 國. 學. typology and in-depth interviews to explore the foreign labor policies of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan, in terms of analyzing their government policies,. ‧. immigration regulations, social problems, and the consequent feedbacks on. sit. y. Nat. government’s policy-making. Meanwhile, this study intends to focus on related. er. io. policies and problems involved with mainland Chinese workers as well. The. n. researcher hope that this astudy can make practical contribution for immigration v policy studies in the less. i l C n h e nAsian explored i Ureceiving g c hlabor. nations, especially in. Taiwan, and provide important policy implication for Taiwan’s foreign labor migration policies.. Key Words: foreign labor, foreign worker, immigration policy, migration policy, foreign talent, mainland Chinese.

(4) Acknowledgement Finally, I have accomplished my thesis writing and obtained my master degree. It is very difficult to juggle work, school and child-rearing. Luckily, my lovely husband, Lawrence Lin, fully supports me and often encourages me to continue my graduate study. Recalling the past, when my elder son, Andrew was one year old, he always waited in front of the bus stop at night, expecting me come home from school. Without my family’s full support and sacrifice, I would definitely not be able to complete my degree. I love you, my husband and two lovely sons, so much.. 政 治 大 In addition, I appreciate my thesis advisor, Prof. Leng Tse-Kang, and the other two 立 committee members, Prof. Mark Chen and Prof. Wei Mei-Chuan. With your kind and. ‧ 國. 學. patient guidance, I finally have my thesis accomplished. Meanwhile, I also appreciate. ‧. Mr. Zhang Zeng-Liang, my teacher at the Central Police University as well as my. sit. y. Nat. supervisor at the National Immigration Agency, and Mr. Wu Jin-Wei, my classmate at. io. er. the Central Police University as well as my colleague at the National Immigration Agency, and Adam Chou, my ex-colleague at the National Immigration Agency. Your. al. n. v i n Ch enthusiastic assistance and encouragement do help me to achieve my goal of getting engchi U this diploma..

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Motivation and Purpose ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Research Framework ................................................................................................................. 6 1.4. Literature Review ...................................................................................................................... 7. CHAPTER TWO 2. A Case Study on Singapore ........................................................................................................... 19 2.1 2.2. 政 治 大 The Main Types of Work Passes............................................................................................. 24 立. A City-State with Multi-racial Composition ........................................................................... 19. An Open Policy Is Only Applied to Foreign Talents? ............................................................ 29. 2.4. Who Are Eligible for Permanent Residence or Citizenship? .................................................. 32. 2.5. Better Integration with or More Xenophobic towards Immigrants? ....................................... 34. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.3. y. sit. Summary ................................................................................................................................. 42. io. CHAPTER THREE. n. al. er. 2.7. Nat. 2.6 Slow the Pace of Introducing Foreign Workforce? ................................................................. 37. i n U. v. 3. A Case Study on Hong Kong......................................................................................................... 43. Ch. engchi. 3.1. A Continuous Population Inflow from Mainland China ......................................................... 43. 3.2. The Main Types of Work Visas .............................................................................................. 49. 3.3. A Set of More Liberal Immigration Policies? ......................................................................... 52. 3.4. Who Are Eligible for the Permanent Residence or Citizenship? ............................................ 59. 3.5. Increasing Hostile Sentiment towards Mainland Chinese? ..................................................... 60. 3.6. A Continuous Open Policy on Attracting Foreign Talents? ................................................... 63. 3.7. Summary ................................................................................................................................. 64. CHAPTER FOUR 4. A Case Study on Taiwan ............................................................................................................... 66 4.1. Formosa with A Strict Control on the Inflow of Immigrants .................................................. 66.

(6) 4.2. Who Needs A Work Visa? ...................................................................................................... 70. 4.3. Strict Policies Are Transformed into More Open Ones? ........................................................ 71. 4.4 Who Are Eligible for the Permanent Residence or Citizenship? ............................................ 75 4.5 Discrimination against Specific Group of Immigrants? .......................................................... 76 4.6. Loosening Restrictions on the Influx of Foreign Workers? .................................................... 78. 4.7. Comparing Immigration Policies among Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan ....................... 81. 4.7.1 Similarities to Immigration Policies among Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan .......................................................................................................................................... 82 4.7.2 Differences in Immigration Policies among Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. 治 政 4.8 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 91 大 立 CHAPTER FIVE ...................................................................................................................................................... 85. 學. ‧ 國. 5. Conclusion and Suggestion............................................................................................................ 92 5.1 Ensure A Balance between Local Talents and Highly-skilled Foreign Workers..................... 93. ‧. 5.2 Adjust the Immigration Policies for Brain-gain ....................................................................... 93. sit. y. Nat. 5.3 Make Use of the Potential Foreign Workforce within Taiwan ................................................ 94. io. al. er. 5.4 Promote Multiculturalism for Better Social Integration .......................................................... 95. v i n Ch References ............................................................................................................................................ 99 engchi U n. 5.5 Control the Inflow of Mainland Chinese Workers................................................................... 95. Appendixes ........................................................................................................................................ 111.

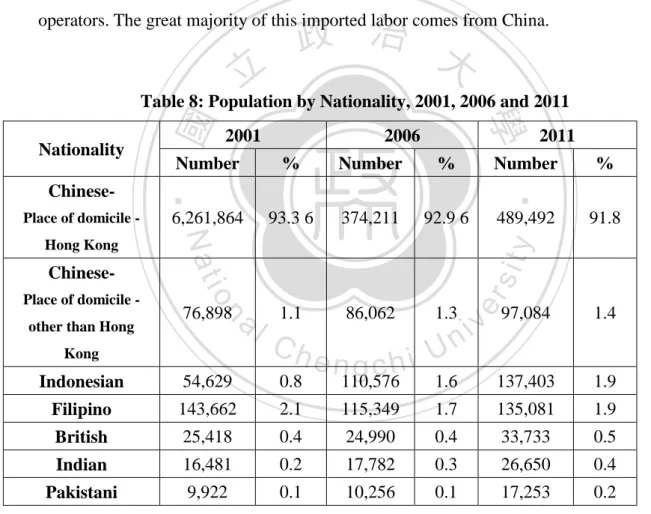

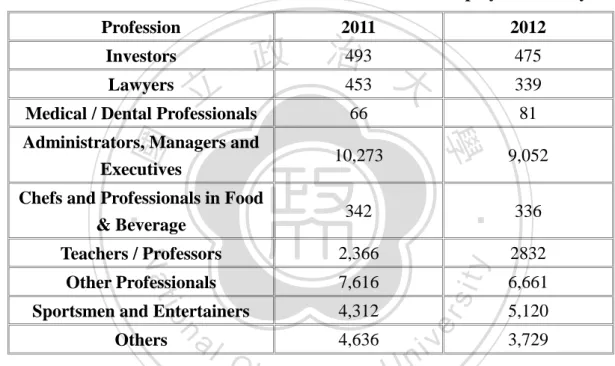

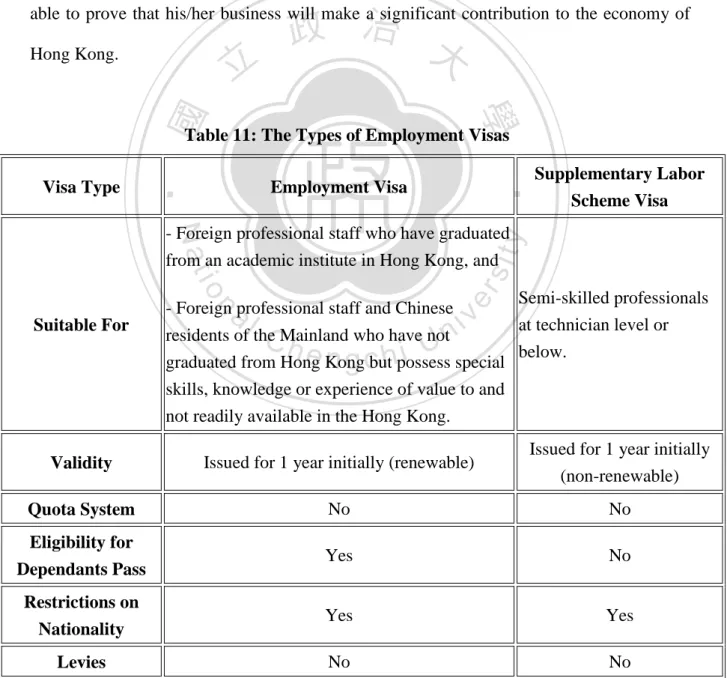

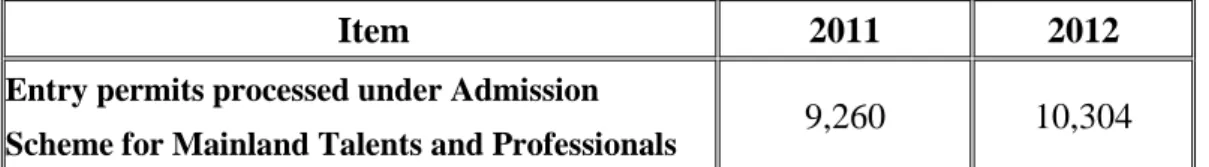

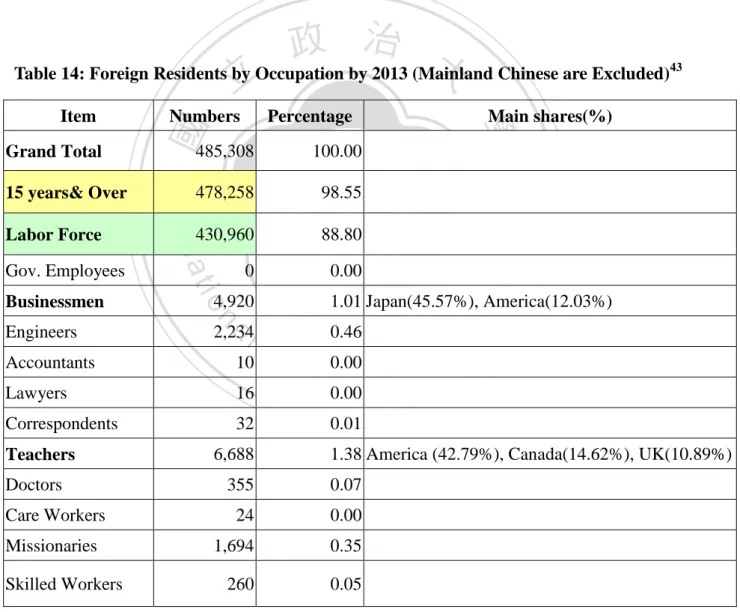

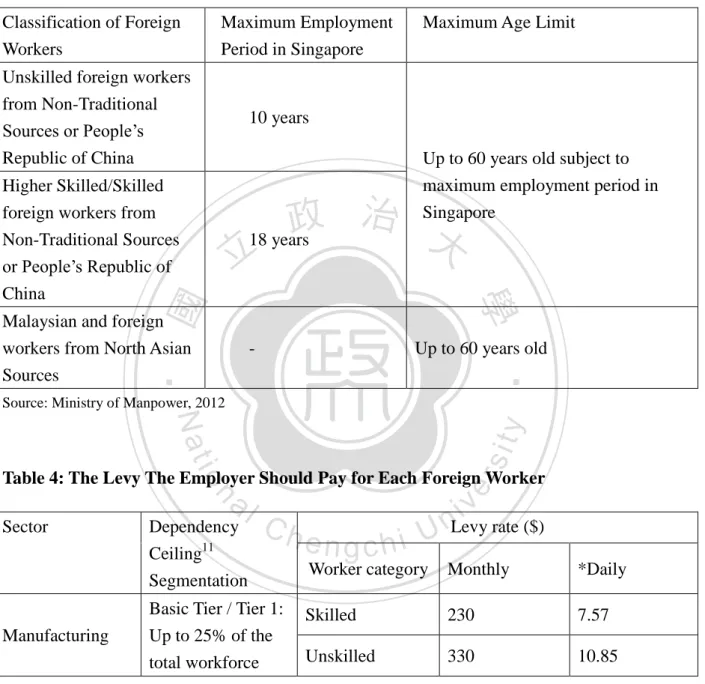

(7) LIST OF TABLES Table 1: The population of Singapore ................................................................................................. 21 Table 2: Resident Population by Ethnic Composition ......................................................................... 21 Table 3: Maximum Employment Period of Work Permit in Singapore .............................................. 22 Table 4: The Levy The Employer Should Pay for Each Foreign Worker ........................................... 22 Table 5: Types of Singapore’s Work Permit Schemes ........................................................................ 27 Table 6: Types of Singapore’s Work Passes........................................................................................ 27 Table 7: The numbers of Foreign Workforce ...................................................................................... 28. 治 政 Table 9: Statistics on Visas Issued under the General Employment 大 Policy ........................................ 48 立 Table 10: Statistics on the Capital Investment Entrant Scheme Breakdown of the Applicants under. Table 8: Population by Nationality, 2001, 2006 and 2011 .................................................................. 47. ‧ 國. 學. CIES ..................................................................................................................................................... 48 Table 11: The Types of Employment Visas ........................................................................................ 51. ‧. Table 12: Statistics on Admission Scheme for Mainland Talents and Professionals .......................... 59. Nat. sit. y. Table 13: The Numbers of Applying Naturalization and Nationality in Hong Kong ......................... 60. al. er. io. Table 14: Foreign Residents by Occupation by 2013 .......................................................................... 69. n. v i n C h Hong KongUand Singapore ................................... 90 Table 16: Numbers of Foreign Labors in Taiwan, engchi Table 15: Comparison of Characteristics of Foreign Labor Policies ................................................... 88.

(8) CHAPTER ONE 1. Introduction 1.1 Motivation and Purpose Under the trend of globalization, the world has become a boundaryless international community; transnational migration has already become a common phenomenon, and the immigrant population has been rising rapidly over the past few years. In recent years, many countries have faced some serious problems, such as the ageing population, labor force. 治 政 well. Attracting immigrants to this island is one of the大 measures to resolve the problems 立. shortage, and economic stagnation, and Taiwan inevitably encounters these problems as. above. Like other developed countries, more and more foreigners have migrated to Taiwan. ‧ 國. 學. after 1980s1. As marriage immigrants from mainland China and Southeast Asian countries. ‧. account for the majority of total number of immigrants in Taiwan, the government‘s. sit. y. Nat. immigration policy mainly puts emphasis on these foreign spouses, especially in terms of. io. er. social integration, guidance and assistance. As for other foreigners, the immigration policy has set up many restrictions on their migration to Taiwan, especially for economic. n. al. migrants.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. For fear that these foreigners would pressure Taiwan‘s labor market, Taiwan‘s immigration policy is not friendly to accommodate economic immigrants. A long-standing debate on Taiwan's immigration policies resurfaced following a speech in 2012 by Singapore's Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, in which he cited Taiwan as a cautionary tale to highlight the importance of attracting foreign talents. Taking up the issue, many Taiwanese business leaders, academics and journalists have blamed bureaucratic red-tapism for the island's inability to attract foreign talents. They called for 1. After 1980, Taiwanese males, who were unable to find spouses among the local female population due to economic or social disadvantages, married Southeast Asian women through efforts of marriage brokers. As a result, the percentage of foreign spouses in Taiwan grew rapidly. 1.

(9) changes to redress this serious problem as well as to stem the outflow of local talents (The Straits Times, 10 April 2012). In order to resolve the problem of brain drain and to attract more foreign talents to Taiwan, the government has started to review its immigration policies and has undertaken to loosen related regulations. On the other hand, with the improvement on the cross-strait relationship, the government has also released regulations to allow more mainland Chinese coming to Taiwan for economic investments, touring, and academic studies. For example, starting from 2011, mainland Chinese students have been allowed to study in Taiwan‘s universities under the government‘s ―three limits, six no‘s‖. 治 政 大 graduates. However, in January of deteriorating employment outlook for Taiwan university 立 (三限六不) policy which bans them from taking off-campus work to avoid adverse impacts. 2013, President Ma Ying-jeou announced that the government was considering allowing. ‧ 國. 學. Chinese students to work in Taiwan (Taipei Times, 17 Jan 2013).. ‧. Due to the special relationship between Taiwan and mainland China, it has always been. sit. y. Nat. a hot issue whether the government should lift regulations to allow Chinese labor force. io. er. entering Taiwan‘s market. Even the two sides have loosened many restrictions on mutual economic exchange since President Ma took office in 2008, Taiwan‘s government assured. al. n. v i n that it will not open mainland Chinese C h labors to TaiwanUso that Taiwan‘s labor market will engchi not be affected. However, with President Ma‘s recent announcement, it implies that. mainland Chinese students would be able to work in Taiwan in the near future while they are in undergraduate studies or after they obtain their diplomas. Consequently, like Singapore and Hong Kong, the government may eventually open the door to import Chinese labor force to Taiwan. Thus, it is important for the government to evaluate the impacts on importing Chinese labor force to Taiwan. Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan are among the Four Dragons economies in Asia-Pacific region. They have some similar characteristics on national conditions, such as having dense population in limited lands, being ethnic Chinese communities, facing the 2.

(10) problems of ageing population, economic downturn and brain drain. For Singapore, it is a city-state depending on foreign labor force, including skilled labor and unskilled labor; its foreign labor forces mainly come from mainland China. For Hong Kong, after its sovereignty was handed over to People‘s Republic of China by the United Kingdom in 1997, more and more Chinese migrates there to look for better lives. Both Singapore and Hong Kong have encountered some problems of importing labor force from mainland China. Thus, it is important and necessary for Taiwan to study their immigration policies and related impacts on importing the mainland Chinese labor force for future policy. 治 政 大for immigration policy studies in This study intends to provide practical contribution 立. reference.. the less explored Asian labor receiving nations, especially in Taiwan. Second, the study. ‧ 國. 學. updates and examines the development of foreign labor migration policies as observed in. ‧. Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Last but not the least, the study explores the social. sit. y. Nat. problems of introducing foreign labor from mainland China in Singapore and Hong Kong,. io. er. and furthermore it intends to provide important policy implication for Taiwan evaluating the impacts on importing mainland Chinese workers. Thus in this study, some issues are. n. al. raised as follows:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1. What are the immigration policies of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan in terms of attracting and managing foreign labor force? And how are these policies implemented? 2. What are the impacts on importing foreign labor force, especially on newcomers from mainland China? 3. What are the feedbacks to government‘s policy-making?. 1.2 Methodology This study uses qualitative method to explore the immigration policies of Singapore, 3.

(11) Hong Kong and Taiwan. In order to answer the research questions above, the primary and secondary data and information related to the issue on the immigration policy from newspaper, journals, text books, articles, research findings, government documents and reports are collected to establish the complete concept in this study.. The changes in the. development of foreign labor migration policies are analysed by using historical analysis. In this part, the most significant projects or events that contributed to the immigration policy-making will be discussed. Meanwhile, the study builds on comparative case study analysis using a most similar case study design. In case selection, the prime consideration is. 治 政 are (1) the Four Dragons economies in the Asia-Pacific 大 region, (2) have dense population in 立 the similarities of national conditions among Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan as they. limited lands, (3) being ethnic Chinese communities, (4) facing the problems of ageing. ‧ 國. 學. population and brain drain, and (5) competing for global talents. In addition, the study also. ‧. employs typology to make the classification of foreign labor migration policies according. sit. y. Nat. to Singapore‘s, Hong Kong‘s and Taiwan‘s characteristics. Furthermore, the research adopts. io. er. in-depth interviews with some officials in order to have more practical understanding in the government‘s policy-making. In-depth interviews with semi-structured questions were. al. n. v i n conducted in person or via internet in Taiwan and Singapore (two in C hwith 3 key informants engchi U. Taiwan and one in Singapore). These informants were selected based on their working. experiences within government agencies involved in immigration policies or foreign labor management. During the process of contacting the government officials for conducting the interview, the researcher encountered great difficulties in finding the volunteers for the interview. Even though the interviewees will be anonymous in this study, most officials are reluctant to be interviewed to talk about government affairs. As the author of this thesis works in the public sector, the NIA of MOI, I found that generally, Taiwanese officials tend to be more conservative to discuss or disclose their information and opinions on the government affairs 4.

(12) to academic researchers in order to avoid facing possible troublesome feedbacks. In addition, it is more difficult to find the interviewees who work involved with immigration affairs in the Government of Singapore or Government of Hong Kong. At first, the researcher tried to contact Singapore Trade Office in Taipei and Hong Kong Economic, Trade and Cultural Office (HKETCO) by telephone calls and emails, but failed to get positive response for the interview. Furthermore, the researcher tried to contact some personnel who work in Singapore and Hong Kong ( three persons work in the Ministry of Manpower of Singapore, one person works in Taipei Representative Office in Republic of. 治 政 by emails or telephone calls. Upon discussing the 大 study and non-disclosure of their 立. Singapore, and one person works for Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Hong Kong). institutional position and personal information within the study, eventually, only three. ‧ 國. 學. persons agree to be interviewed in person or online.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 5. i n U. v.

(13) 1.3 Research Framework This study intends to explore the foreign labor policy of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan, in the perspective of analyzing their government policies, immigration regulations, social problems, and the consequent feedbacks to government‘s policy-making. Furthermore, in Singapore and Hong Kong, mainland Chinese labor force makes up the majority of total number of foreign labor force while there still has many restrictions on allowing mainland Chinese to settle in Taiwan. This study would like to focus on related policies and problems involved with mainland Chinese workers as well.. 治 政 大 Political Factor 立 National Identity ●. io. Workers. n. al. Globalization ● Economic Competition among Countries ● International Labor Migration. Ch. engchi. Policy-making. 6. er. Mainland Chinese. sit. Nat. Foreign Workers. y. ‧. ‧ 國. Classism. 學. ●. i n U. v. Social Factor Demographic Changes ● Ethnic Integration ●. Economic Factor ● Industry Structure ● Knowledge-based Economy.

(14) 1.4 Literature Review In historic times, hunters, nomadic tribes, and farmers moved when the environment became no longer viable for their livelihood. In other words, human migration has existed since human existence. Large international migration began in the 16th century during the age of European expansion. In the 19th and 20th centuries, industrialization and innovations in shipping and railways accelerated the growth of international migration. Researchers in the field of migration generally agree that the reasons for migration include social reasons such as family reunion, political reasons, and more commonly, economic. 政 治 大 mainly to seek a better living. 立All these movements of people have been influenced by push. reasons (Chan, 2005). People leave their mother country and migrate to another country. ‧ 國. 學. and pull factors such as inadequate income levels in the home country, better jobs available abroad, opening of borders, easier mobility due to better communications and. ‧. transportation infrastructure, and the increasing need for services around the world. sit. y. Nat. (Calzado, 2007). Many universal theoretical frameworks have been applied to international. n. al. er. io. relations, from Marxist analysis of global capitalism to more recent presentations in terms. v. of world-systems theory. But these have essentially referred to relationships between states,. Ch. engchi. i n U. economies or cultures—that is, between relatively independent entities. The essence of globalization is that barriers between these entities are dissolving and open up the possibility of some kind of consciousness (Stalker, 2000). David Held and his collaborators define globalization as ‗the widening, deepening and speeding up of world-wide interconnectedness in all aspects of contemporary social life. They argue that contemporary processes of globalization are historically unprecedented and a product of unique conjuncture of social, political, economic and technological forces (Held et al., 1999). Globalization is a complex web of interrelated processes—some of which are subject to greater control than others. Of these, international migration is the one most likely to. 7.

(15) provoke intervention. Governments are less willing nowadays to block flows of trade or finance but take much more resolute action when it comes to people (Stalker, 2000). Despite the different interpretations of globalization, its most distinctive features or concepts can be summarized under four main headings: stretched social relations, intensification of flows, increasing interpenetration, and global infrastructure (Cochrane and Pain, 2000). There is no single, coherent theory of international migration. Current patterns and trends in immigration suggest that a full understanding of contemporary migratory. 治 政 focusing on a single level of analysis (Massey et al., 大 1993). Apart from ―push and pull‖ 立. processes will not be achieved by relying on the tools of one discipline alone, or by. factors of labor migration, there are many other migration theories. Neoclassical economics. ‧ 國. 學. focuses on differentials in wages and employment conditions between countries, and on. ‧. migration costs; it generally conceives of movement as an individual decision for income. sit. y. Nat. maximization. The resulting differential in wages causes workers from the low-wage. io. er. country to move to the high-wage country. As a result of this movement, the supply of labor decreases and wages rise in the capital-poor country, while the supply of labor increases. al. n. v i n and wages fall in the capital-richCcountry, leading, at equilibrium, to an international wage hengchi U. differential that reflects only the costs of international movement, pecuniary and psychic. Under the neoclassical economics theory, we can find that in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, numbers of foreign unskilled/semi-skilled workers from Southeast Asia and South Asia in manufacturing, construction, and domestic service sectors have grown due to the growing labor shortage and the attraction of higher wages; the factor on the demand side are the rapid economic development, and the factor on the supply side is the declining total fertility rate (TFR) and rising educational attainment of local people. With growing affluence and more available employment opportunities, even the lowly educated local people are increasingly loath to unskilled jobs or semi-skilled jobs that are usually 8.

(16) considered difficult, dirty, and dangerous (3D jobs) with lower pay. The ―new economics of migration‖ theory, in contrast, considers conditions in a variety of markets, not just labor markets. It views migration as a household decision taken to minimize risks to family income or to overcome capital constraints on family production activities. Dual labor market theory and world systems theory generally ignore such micro-level decision processes, focusing instead on forces operating at much higher levels of aggregation. The former links immigration to the structural requirements of modern industrial economies, while the latter sees immigration as a natural consequence of. 治 政 大 Although the truism holds that 1993). Labor migration may begin for a variety of reasons. 立 economic globalization and market penetration across national boundaries (Massey et al.,. economic forces often play an important role as one of the root causes of migration, and. ‧ 國. 學. people tend to move to places where the standards of living are better, this alone cannot. ‧. explain the actual shape of migration patterns (Salt, 1987:243; Schoorl, 1998). This draws. sit. y. Nat. our attention to the role of nation states, geographical proximity, institutions, social. io. er. networks, and cultural and historical factors in creating new migration patterns (de Haas, 2008). Due to economic globalization, the settlement of foreign population has been a new. al. n. v i n phenomenon in most Asian labor C hreceiving countries.UWhile government policy dealing engchi. with this intricate and challenging ―problem‖ converges partially with that of Western immigrant countries, Asian immigration policies have their unique elements and characteristics structured on the backdrop of its own socioeconomic, political and historical background (Cho, 2011). In all the receiving countries under study, both immigration rules and integration policies have increasingly been related to what is deemed to serve the national interests, including the national security, economic development and social order. Research revealed that student and skilled migration, in particular, is often circular, taking place in binational or wider international contexts; students and skilled migrants especially have adopted highly mobile and transnational lifestyles. This became evident especially 9.

(17) among highly skilled respondents, many of whom moved internationally because of their careers or studies. In all destination countries, the current tendency is characterized by selective immigration policies and the intention to recruit labor force, especially highly qualified professionals from abroad (Pitkänen, Içduygu and Sert, 2012). While most nation-states accept “ wanted ” foreign labor, they control the border to prevent “unwanted” influxes of foreigners from poor countries (Martin, 2003; Martin and Miller, 2000a, 2000b). Many recent migration flows were unanticipated, and they led to efforts by receiving. 治 政 大 have considerable control industrial countries has slowed, demonstrating that governments 立. countries to reduce the influx of migrants. The increase in the number of migrants in many. over entries and stays (Martin, Abella and Kuptsch, 2006). The preferred labor immigration. ‧ 國. 學. policies of most receiving countries tend to place most weight on economic efficiency,. ‧. distribution and national identity (including security) of their citizenry as collectives, less. sit. y. Nat. weight on individual rights (related to the employment of foreign workers), and least. io. er. weight on the impacts on migrants and non-migrant citizens of sending countries. This is perhaps best illustrated by the popular appeal of ―manpower planning exercises‖ behind. al. n. v i n many countries‘ labor immigration C hpolicymaking. Thus,Ua balanced approach to the design engchi. of labor immigration policy would, at a minimum, require policies that protect a citizen‘s right to preferential access to the national labor market; ensure that the receiving country derives net economic benefits from the employment of migrant workers, and prevent immigration from adversely affecting national security, public order and the social and political stability of the receiving country (Ruhs, 2005). Castles and Miller (2003: 249-252) categorize the acceptance of foreign migrant workers by different nations in the following three categories: the differential exclusionary model (hereafter “exclusionary model”), the assimilationist model, and the multicultural model. Seol Dong-Hoon (2004) noted that ―the exclusionary model admits foreign workers or 10.

(18) immigrants only in limited economic sectors, such as the 3D labor markets, and never accept them in civic and political sectors such as citizenship and voting rights. The assimilationist model sets it as ideal that foreign workers or immigrants totally give up linguistic, cultural, and social features of their origin and do not show any difference from the mainstream society. The multicultural model admits and supports the culture of immigrants and sets the goal of policy as coexistence rather than minorities‘ assimilation to the mainstream society‖ (Seol, 2004). By collecting related literature, the researcher finds that Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan may be defined as the mixes of the exclusionary. 治 政 大 and South Asian countries, and blue-collar foreign labor from the Southeast Asian countries 立. model and the multicultural model; the former model is applied to the management of. the latter is applied to the management of white-collar foreign labor.. ‧ 國. 學. In Singapore, a restrictive immigration policy has been enforced since its independence. ‧. in 1965. Singapore distinguishes between the highly skilled and the less skilled foreign. y. Nat. labor. The regulation of the latter rests mainly on two policies: first, a system of. er. io. sit. dependency ratio ceiling; second, the imposition of higher “ levies ” in order to discourage employers from over-reliance on cheap, less-skilled foreign labor (Yeh, 1995;. al. n. v i n Chiew, 1995; Hui, 1998). The situation is similar to Singapore‘s. Historically, C h of Hong Kong U engchi. having foreign domestic helpers used to be one of the most potent status symbols in Hong. Kong, but more recently it became more of a necessity for middle-class families with children. In double-income families, the relatively high wages of Hong Kong‘s middle class women allowed them to employ domestic helpers who relieved them of their domestic duties and child care (Tam, 1999). A similar trend has been observed throughout the region, for example, in Singapore (Yeoh and Huang, 1999) and Taiwan (Lan, 2002, 2003a and 2003b). Today, being incorporated into the global economy, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore are the draws for migratory laborers of Southeast Asian origins (Jones, 2004; Cheng, 2008). 11.

(19) While foreign domestic workers are seen as unskilled labor who are potentially competing with local workers for the decreasing number of low-waged jobs, foreign professionals were classified as ―foreign talents‖ that Hong Kong and Singapore wish to attract (Chiu, 2004a, 2004b; Wee and Sim, 2005). The job market of Hong Kong and Singapore has always been open to foreign professionals. Their admission has not been constrained by quotas or job sector restrictions. Under the Employment Policy, foreign residents could apply for work permits as well as residence permits (Wong, 2008). In Taiwan, there has had liberalized foreign labor policy in order to deal with labor shortage. 治 政 development of Taiwan for the two previous decades大 (Cheng, 2001; Lee, 2004; Weng, 立. since 1990s. The presence of foreign labor has resulted from the state-led capitalist. Tseng, Lee and Juan, 2004). However, compared with Singapore and Hong Kong, Taiwan. ‧ 國. 學. is far from adopting open immigration policy to attract foreign talents there as well as to. ‧. import foreign guest workers. Consequently, Taiwan has been suffering from the problems. sit. y. Nat. of brain drain of highly-skilled professionals and manpower shortage of 3D jobs. Currently,. io. er. the Taiwanese government is launching some schemes to attract more mainland China-based Taiwanese businesspeople to relocate their businesses back to Taiwan with. n. al. Ch. relaxing the flow of foreign investment and the. engchi. v i n quota of foreign U. workers (including. blue-collar workers, white-collar workers and mainland Chinese workers). Rapid economic growth elsewhere in East and Southeast Asia has also stimulated many new migration flows. The newly industrializing economies (NIEs) of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan have all attracted immigrant workers. Like Japan, they have been determined to increase levels of technology to avoid labor shortages, but have nevertheless had to permit immigration, particularly for industries such as construction that demand large of unskilled workers. Even the NIEs are discovering that the immigrant work force has become structurally embedded in their economies and societies and will not necessarily disappear. All have tried to control the inflows (Stalker, 2000). Singapore and Hong Kong 12.

(20) have launched some schemes to manage and moderate the inflow of foreign workers (especially subject to unskilled/low-skilled workers) in order to avoid becoming overly dependent on foreign workers; among these unskilled/low-skilled workers, a very high percentage of population comes from mainland China. In Taiwan, alongside the labor shortage, the globalization and internationalization of the Taiwanese economy caused the government to respond with a more liberalized immigration policy and to permit limited numbers of foreign workers to come to Taiwan. As Taiwan is moving towards a knowledge-based economy, the demand for highly skilled workers and professionals. 治 政 foreign talents to enter Taiwan. Meanwhile, Taiwan 大 is increasingly using cross-border 立 increase quickly. Thus the government is revising the immigration policies to attract more. marriages as one of the ways to deal with its domestic labor shortage (Lee, 2010). In these. ‧ 國. 學. three countries, foreign highly-skilled workers are welcomed to migrate to their country. ‧. with the convenience of permanent residence while classism has played a firm role in. sit. y. Nat. preventing guest workers from becoming permanent members. Bablibar (1991) uses ―class. io. er. racism‖ to refer to such conflations of race and class to divide people into categories that cannot easily be integrated. In anti-immigrant racism, it is most obvious that such racism. al. n. v i n has been used to exclude working-class C h people but notUimmigrants in general. Immigrants engchi. with a higher economic profile are considered acceptable as future members of society despite their ethnicity and nationality, while immigrants from lower-class background are excluded or segregated on the basis of their ―incompatibililty‖ in the social, cultural and political sense (Tseng and Komiya, 2011). In Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, the policies divide the foreign workers into two categories: unskilled or low-skilled workers at the lower class; the highly-skilled workers at the higher class. In addition, these three countries all create a separate legal status for lower-class foreign workers to make sure that such workers‘ visits to their country are of a temporary nature. Lower-class foreign workers‘ opportunities to become probationary immigrants are blocked by such a 13.

(21) recruitment policy (Tseng and Komiya, 2011). Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are leading countries in Asia that admit increasing numbers of economic immigrants and marriage immigrants. As a result of immigration, racial and ethnic diversity of the three countries have significantly increased, challenging each country with unprecedented phenomena. Like other countries, the three countries face the tasks of accommodating new members to society as well as helping them integrate to mainstream society. Social integration is, however, far from smooth on the ground. To some locals, newcomers — particularly the ubiquitous mainland Chinese — are commonly. 治 政 大 and unskilled workers have also and talking loudly in public. Similarly, low-skilled workers 立 seen as uncouth and prone to objectionable behaviors like littering, eating on public transit,. been singled out as targets of public backlash. With criminal activity rising, foreigners have. ‧ 國. 學. also been blamed for the deterioration of public safety. In addition, locals have been feeling. ‧. the squeeze as they face stiffer competition for job opportunities. In most cases,. sit. y. Nat. policymakers are afraid of the nativist perceptions that offering jobs to foreigners puts local. io. er. workers‘ employment opportunities at risk (Tseng and Komiya, 2011). In Wong Siu-lun‘s (2008) study, he noted that some Hong Kong studies pointed out that mainland. al. n. v i n professionals from large Chinese various challenges in their new residence. C cities h e nfaced gchi U. Even though they do not experience the same level of social and cultural discrimination like unskilled labors, their adjustment and integration into Hong Kong society have not been easy. The media further contributed to the proliferation of negative images of mainland Chinese immigrants by their reports on the crimes committed by new immigrants and by overstating the pressure they put on the welfare system. Hong Kong people. developed a strong prejudice against their ―cousins‖ over the border, and saw influx of cheaper labor as a potential threat to their high wages (Wong, 2008). Longitudinal research conducted by the Hong Kong Baptist University comparing psychological and sociocultural adjustment of foreign and mainland professionals came up with surprising 14.

(22) findings. Comparing the three-dimensional model of expatriate adjustment, i.e. (1) adjustment to work, (2) adjustment to interaction with local people, and (3) adjustment to the non-work environment, it was suggested that despite cultural proximity the mainland professionals‘ adjustment fell behind that of western expatriates (Selmer et al., 1999a and 1999b). Interestingly, with a decade passing, nowadays, the mainland professionals‘ adjustment still seems to fall behind that of western expatriates in Hong Kong, as well as those in Singapore and Taiwan. Since the late 1970s, strong movement towards ―localization‖ saw the emergence of a. 治 政 大 ―exclusion mentality‖ which new identity later became the foundation of Hong Kong‘s 立. Hong Kong identity that was negotiated in contrast to the mainland Chinese identity. This. manifested itself in the restrictive immigration system and hardened immigration policies. ‧ 國. 學. (Wong, 2008). Hong Kong immigration policies are guided by differential exclusion, i.e.. ‧. creating attractive conditions for ―quality migrants‖ from certain countries and at the same. y. Nat. time introducing restrictions on entry of others (Wong, 2008). Singapore has long been. er. io. sit. known as Hong Kong‘s key competitor in the region and has been steadily attracting investments, foreign capital and talented professionals. One of the key factors driving the. al. n. v i n economy forward is its open immigration is no denying that the open-door C h policy. There engchi U policy is a red hot political issue attracting criticism from the local community, but the reality is that it has worked to Singapore‘s advantage. It has been argued elsewhere (Sassen, 2001) that global cities attract different tiers of labor migrants, from transnational highly paid professionals to under-paid illegal to semi-illegal labor migrants, who play an important role in fueling the global economy. This two-tiered labor migration is consistent with the historical experience of Singapore and Hong Kong. The success of Singapore and Hong Kong as a knowledge-based society supported by a service economy would not have been possible without a large pool of immigrants from mainland China, professionals from all around the world and more recently imported workers from Southeast Asian countries 15.

(23) and South Asian countries (Wong, 2008). On the other hand, the immigration policies are also dominated by the consideration of national security. Since the 1980s — and accelerating with the end of the Cold War — the content of national security concerns has expanded from the traditional focus on military threats to borders and governments to include non-military sources of insecurity (Rogers & Copeland, 1993:12). Immigration can be a threat to traditional ideas of national security even if one concludes it has not yet posed such a threat to the country (Morgenthau, 1958:66). With global economic crisis, immigration policies bound to balancing openness. 治 政 security-centric. The discussion of migration all over 大 Asia encountered a setback in the 立 and control tend to shift towards the latter and become increasing selective and. aftermath of September 11. The climate has now become more hostile to migrants, stoking. ‧ 國. 學. fears of migrants as the dangerous ―others‖ (Schucher, 2008). Although Hong Kong has. ‧. always extended an open arm to overseas professionals, the restriction on highly-qualified. sit. y. Nat. mainland Chinese had always been much stricter (Chiu, 2006). Similarly, Taiwan‘s. io. er. immigration policies towards mainland Chinese people have been stricter than other foreigners. Specially, mainland spouses are constructed as a separate social and. al. n. v i n demographic category in state policies compared to other immigrants and C h and statistics, and engchi U Southeast Asian spouses (Lu, 2011). According to the ―modernization theory‖ and ―Market-Guardian theory‖, the more comprehensive development the global modernization has, the more rampant the transnational crimes will be. As the push factor in the market and in the economic development (i.e. the conditions of demand and supply in the economic market) is stronger than the pull factor in guardian (i.e. preventing the crime from happening), the transnational crimes will easily happen and grow in strength (Chen, 2012). In Taiwan, foreigners from Southeast Asian countries and mainland China are usually alleged to be involved with bogus marriage, prostitution, illegal employment, counterfeit passports and residence cards, and even to commit human trafficking crimes. Thus 16.

(24) marriage immigrants and guest workers are under stricter control and inspection from their application of entering Taiwan to their duration of residence in Taiwan. Even though they did make contributions to the positive outcomes for the economy, they are essentially biased by classism. As for the nationalism, Shih articulates that Chinese identity is not compatible with Taiwanese identity because the People‘s Republic of China (PRC) threatens national security of Taiwan (Shih, 2002, 2003, 2005). Shih‘s elaborate arguments demonstrate that Taiwanese nationalism is such an overwhelming political campaign that it not only claims ownership of multiculturalism but also makes claims of complete allegiance of immigrants. This is a striking contrast to ‗transnationalism‘, which is what. 治 政 大 of identity that straddles Bash (1994) found common in immigrants‘ lived experience 立 across their home country and adopting country (Cheng, 2008).. ‧ 國. 學. During the process of collecting related literature, the researcher finds that most studies. ‧. mainly research the immigration policies on single countries, especially on Western. sit. y. Nat. countries. In addition, most studies related to the issue on immigration policies or foreign. io. er. labor policies usually put emphasis on the study of social integration or the management/human right of blue-collar foreign workers. Few explore the development of. al. n. v i n managing foreign talents in Asian let alone make comparative C hlabor receiving countries, engchi U. study with Taiwan and other Asian countries. This study mainly adopts ―globalization theory‖, ―push and pull theory‖ and ―theory of neoclassical economics‖ to define the. phenomenon of transnational labor migration; employs the ―theory of national identity‖ and ―classim‖ to explain the reasons why the Government of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan classify foreign workforce into two categories: mainland Chinese workers and other foreign workers/blue-collar workers and white-collar workers. In addition, this study adopts ―market-guardian theory‖ to emphasize the importance of national security for the policy-making. On the other hand, in this study, the researcher puts more emphasis on the development of managing foreign talents and uses the most similar case study on Singapore, 17.

(25) Hong Kong and Taiwan, and furthermore makes the comparative method to analyze the similarities and differences among these three countries. Thus, some important characteristics of the foreign labor migration policies among Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan are found: (1) both immigration rules and policies are closely related to what is deemed to serve the national interests. (2) The current tendency is characterized by selective immigration policies and the intention to recruit labor force, especially highly qualified professionals from abroad. (3) They take an effort to attract“wanted” foreign labor, but control tightly to prevent the influxes of “unwanted”foreigners. (4) They are. 治 政 大 number of skilled workers are have come from the developed countries, but an increasing 立 the draws for migratory laborers of Southeast Asian origins. (5) Most skilled professionals. now from mainland China. (6) They face the tasks of accommodating new members to. ‧ 國. 學. society as well as helping them integrate to mainstream society, especially for those. ‧. immigrants from mainland China.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 18. i n U. v.

(26) CHAPTER TWO 2. A Case Study on Singapore 2.1 A City-State with Multi-racial Composition2 Singapore is a city-state with a land area of 710 square kilometers 3 and about a population of 5.3 million4. As of 2012, about 28 % of the total population is non-residents (immigrants who are in Singapore temporarily, such as students and certain workers), and 10 % is permanent residents (PRs). This country has long depended on immigrants to meet. 治 政 大 of in-migration, the population independence from Malaysia in 1965. Reflecting the history 立. its labor force needs and to enhance its economic development since it obtained. is multi-racial in composition, currently with 74.2% Chinese, 13.3% Malays, 9.2% Indians. ‧ 國. 學. and about 3.3% of other ethnicities. Immigrants in Singapore can mainly be divided into. ‧. three categories according to their identity:. sit. y. Nat. 1. Low-skilled workers (primarily in the construction, domestic labor, services,. io. er. manufacturing industries):. Singapore‘s unskilled/semi-skilled work permit holders are largely from developing. al. n. v i n Asian countries with lower C wages than Singapore, namely Malaysia, Southeast Asian hengchi U. countries, North Asia (mainly China) and South Asia (mainly India). While the unskilled/semi-skilled from Malaysia are allowed to work in all sectors, worker from Southeast Asian countries are generally allowed to work in construction and marine sectors and as domestic maids; workers from mainland China are not allowed to work as domestic maids. The preference is for domestic maids from ASEAN and increasingly 2. Data on the number and country sources of Singapore‘s foreign workers are not available in the public domain (considered by the government to be ―sensitive‖) and information had to be gleaned from various media sources, official speeches and parliamentary proceedings. 3 Source: http://www.contactsingapore.sg/tc/why_singapore/facts_and_figures/, accessed on 7 March 213. 4 According to the statistics from Department of Statistics of Singapore (retrieved 8 March 213, from http://www.singstat.gov.sg/stats/charts/popn-area.html), as of 2012, the total population is 5,312,400, including 1,494,200 non-residents and 3,818,200 residents (among residents, the number of citizens is 3,285,100 and the number of permanent residents is 533,100). 19.

(27) from South Asia. These workers are managed through a series of measures, including the work-permit system (including compulsory medical screening), the dependency ceiling (which regulates the proportion of foreign to local workers), and the foreign worker levy. Workers are only allowed to work for the employer and in the occupation indicated in their work permit, though a sponsored transfer of employment is permissible and subject to work pass validity. The termination of employment of a foreign worker results in the immediate termination of the work permit, in which case the immigrant must leave Singapore within seven days.. 治 政 大 Singapore‘s development, the government 立. 2. Skilled workers (generally better-educated S-pass or employment pass holders): To boost. has focused on developing. Singapore into the ―talent capital‖ of the global economy and strives for increasing. ‧ 國. 學. highly skilled workforce, including company grant schemes to ease the costs of. ‧. employing skilled foreigners, a housing scheme to aid in the short-term accommodation. sit. y. Nat. needs of skilled foreign workers. To reach this goal, Singapore has liberalized some of. io. er. its immigration policies (while tightening others related to low-skilled immigration) and made it easier for skilled migrants to gain permanent residency and citizenship. al. n. v i n since the 1980s. In the past, C most skilled professionals have come from the developed hengchi U. countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Australia, as well as Japan and South Korea. Due to policies instituted in the 1990s to recruit the highly skilled in nontraditional source countries, the majority of skilled workers (apart from Malaysians) are now from China and India. 3. Foreign students: As foreigners account for over one-third of Singapore‘s labor force, the government of Singapore has made the recruitment of foreign students a priority since 1997 to attract more foreign talents to Singapore. International students make up 18% of the total. 20.

(28) undergraduate intake in Singapore's universities for the academic year of 20115; there were over 90,0006 foreign students representing over 120 nationalities in Singapore. Furthermore, the government had chalked out an ambitious plan to attract over 150,000 international students to its universities and educational institutions by 2015. It was revealed that at least 2,000 scholarships worth S$36 million were awarded each year to overseas students. Correspondingly, foreign students receiving scholarships are required to serve a three to six year bond after graduation7.. 政 治 Residents大. Table 1: The Population of Singapore. Total Population8. 2012 2011. 立. Singapore Permanent Residents. Non-Residents. 3,818.2. 3,285.1. 533.1. 1,494.2. 5,183.7. 3,789.3. 3,257.2. 532.0. 1,394.4. ‧ 國. 5,312.4. 學. Total. Singapore Citizens. ‧. Year. Source: Yearbook of Statistics Singapore, 20129 (the unit of numbers is thousand). er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Table 2: Resident Population by Ethnic Composition. Ch. Year. Total. Chinese. 1990. 2735.9. 2127.9(77.8%). 2000. 3,273.4. 2010. 3,771.7. Malays. i n U. v. e n384.3(14.0%) gchi. Indians. Others. 194.0(7.1%). 29.6(1.1%). 2,513.8(76.8%). 455.2(13.9%). 257.9(7.9%). 46.4(1.4%). 2,794.0(74.1%). 503.9(13.4%). 348.1(9.2%). 125.8(3.3%). 5. Source: http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/1161001/1/.html, accessed on 15 March 213. 6 According to the news from Time Strait, in August 2010, the number of foreigners studying here dropped to 91,500 from 95,500 last December; in 2008, before the recession dug in, the number of foreign students was at a high of 96,900. 7 According to the Tuition Grant scheme, international students who receive the tuition grant pay fees that are about 70% higher than those paid by Singaporeans. In addition, they are required to work in Singapore for three years. Some of them are also on various scholarships, which cover their tuition fees but require them to serve a longer bond period of six years (retrieved 13 March 213, from http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/1161001/1/.html) 8 Total population comprises of Singapore residents and non-residents. Resident population comprises Singapore citizens and permanent residents. Non-resident population comprises foreigners who were working, studying or living in Singapore but not granted permanent residence, excluding tourists and short-term visitors. 9 Source: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/pubn/reference/yos12/statsT-population.pdf, accessed on 8 March 213. 21.

(29) 2011. 3789.3. 2808.3(74.1%). 506.6(13.4%). 349.0(9.2%). 125.3 (3.3%). 2012. 3,818.2. 2,832.0(74.2%). 509.5(13.3%). 351.0(9.2%). 125.7(3.3%). Source: Department of Statistics, 201210. Table 3: Maximum Employment Period of Work Permit in Singapore Classification of Foreign Workers. Maximum Employment Period in Singapore. Unskilled foreign workers from Non-Traditional Sources or People‘s Republic of China. Maximum Age Limit. 10 years Up to 60 years old subject to maximum employment period in Singapore. Higher Skilled/Skilled foreign workers from Non-Traditional Sources or People‘s Republic of China. 治 政 大 18 years 立. ‧ 國. 學. Malaysian and foreign workers from North Asian Sources. -. Up to 60 years old. ‧. Source: Ministry of Manpower, 2012. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Table 4: The Levy The Employer Should Pay for Each Foreign Worker Sector. Manufacturing. 10. 11. Dependency Ceiling11 Segmentation. Ch. Basic Tier / Tier 1: Up to 25% of the total workforce. engchi. v iLevy n rate ($) U. Worker category. Monthly. *Daily. Skilled. 230. 7.57. Unskilled. 330. 10.85. Source: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/pubn/popn/population2012b.pdf, accessed on 8 March 213. Dependency Ratio ceiling was introduced in 1987 and has been adjusted over time to meet changing economic. conditions and to regulate the employment of foreign workers. All sectors have dependency ratio ceilings except for FDWs. The purpose is to minimize the preference of employers for the lower-wage foreign workers. The dependency ratio ceiling is sector specific and firm-specific and can range from 10% to 80%. For example, in the manufacturing sector, employers can have 40% of the workforce on work permits, subject to a maximum ceiling of 65%. 22.

(30) Skilled. 330. 10.85. to 50% of the total workforce. Unskilled. 430. 14.14. 500. 16.44. Tier 3: Above 50% to 60% of the total workforce. Skilled. Basic Tier / Tier 1: Up to 15% of the total workforce. Skilled. 270. 8.88. Unskilled. 370. 12.17. Tier 2: Above 15% to 25% of the total. Skilled. 380. 12.50. Unskilled. 480. 15.79. Unskilled. workforce. Higher Skilled and on MYE. 280. 9.21. Basic Skilled and on MYE. 400. 13.16. y. 18.09. io. n. i n U. v. Basic Skilled, Experienced and exempted from MYE. 650. 21.37. Skilled and on MYE. 230. 7.57. 1 local full-time worker to 7. Unskilled and on MYE. 330. 10.85. Foreign Workers. Experienced & exempted from MYE. 500. 16.44. Skilled. 230. 7.57. Ch. Process. Marine. 550. ‧. Nat. Higher Skilled, 1 local full-time Experienced and worker to 7 foreign exempted from Workers MYE12. al. 18.09. 學. Construction. ‧ 國. 立. Skilled 治 政 大550 Unskilled. sit. Tier 3: Above 25% to 45% of the total workforce. er. Services. Tier 2: Above 25%. 1 local full-time. engchi. 12. To be exempted from MYE, the foreign worker must have at least two years of working experience in Singapore. This must be relevant to the sector they are employed under. 23.

(31) worker to 5 Foreign Workers. Unskilled. 330. 10.85. Source: Ministry of Manpower, 2012. 2.2 The Main Types of Work Passes Given the historical ties, Malaysian workers are subject to fewer restrictions than workers of other nationalities. Malaysians can find work while they are already in Singapore, and are generally treated better than other migrant workers in terms of wages, working hours and conditions. All other foreign workers have to apply for a work pass. 政 治 大 September 1998, foreigners working in Singapore were divided into 2 main categories: 立. from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) before they can work in Singapore. Before. employment pass holders (EP) who were skilled professional/managerial workers, and. ‧ 國. 學. work permit holders (WP) who were low-skilled/unskilled migrant workers. In Singapore,. ‧. the work permit process is managed by the Ministry of Manpower. There are several kinds. y. Nat. of work permit, and the type awarded generally depends on the salary range of the job.. er. io. sit. Currently there are four main types of work passes13 as follows: 1. Employment Pass (EP)14:. al. n. v i n type C of work permit meant h e n g c h i U for company. The pass is the main. owners or skilled. employees that will be working in Singapore. With effect of 1 January 2012, the applicant‘s fixed monthly salary must be more than S$3,00015 (previously S $2,800) and should be a degree holder from a reputable university. Foreign executives, professionals, manager directors as well as shareholders who want to work in Singapore can apply for. 13 Source: http://www.contactsingapore.sg/visas_and_passes/for_employment/, accessed on 2 March 2013. 14 There are three types of Employment Passes (P1, P2 and Q1). The P Pass is for foreigners seeking professional, managerial or executive and specialist jobs. 15 With effect from 1 January 2012, the salary threshold for the corresponding passes will be as follows: ˙P1 Pass: for a base salary above S$8,000 a month. ˙P2 Pass: for a base salary between S$4,500 and S$8,000 a month (previously between S$4,000 and S$8,000 a month). ˙Q1 Pass: for a base salary between S$3,000 and S$4,500 a month (previously between S$2,800 and S$4,000 a month). 24.

(32) the Employment Pass or EP. Singapore immigration permits foreign entrepreneurs to apply for employment passes or visas only after they have established their company in Singapore. This Employment Pass is provided to facilitate the stay and entry of entrepreneurs who are ready to begin new business in Singapore. The Singapore Employment Pass has a validity period of two years and can be renewable up to three years. 2. Personalised Employment Pass (PEP)16: The pass is for professionals earning an annual salary more than S$144,000 (previously. 治 政 大 The biggest benefit of having of Employment Pass that is not tied to a specific employer. 立. S $34,000) and the change in validity of PEP from 5 years to 3 years; it is a special type. a PEP work permit is that you can switch jobs without re-applying for a new. ‧ 國. 學. employment pass provided that you are not unemployed for more than six months. The. ‧. biggest downside is that you are not allowed to start your own company as a PEP holder;. sit. y. Nat. instead you must be employed by a third-party employer. PEP is targeted for highly. io. er. qualified individuals who wish to work and live in Singapore. It is not meant for business owners who wish to operate their own business in Singapore. From 1 December. al. n. v i n 2012, the qualifying criteria for been raised and some of its features have been CPEP h ehave ngchi U. refined. This ensures that the PEP remains a premium pass for top-tier foreign talents and. is in line with recent moves to raise the quality of Employment Pass holders. 3. Entrepreneur Pass (EntrePass): It is a variation of Employment Pass and is the primary type of work pass for owners of newly incorporated (or to be incorporated) Singapore companies who wish to relocate to Singapore to operate their new business. It is designed for foreign entrepreneurs who wish to start a business in Singapore and will have at least 30% of company shares.. 16. The PEP is a new scheme to encourage global talent to work in Singapore. Unlike the Employment Pass (EP), the PEP is not tied to any employer and is granted based on the applicant‘s individual merits. 25.

(33) EntrePass is not required if the person does not plan to relocate to Singapore. It‘s possible to apply for Entrepreneur Pass before incorporating the Singaporean company. Once the pass is approved, the applicants will generally be given 30 days to incorporate the proposed company and inject the necessary share capital. The Entrepreneur Pass allows foreigners to bring family (spouse and unmarried children under 21) to Singapore by applying for their dependent passes. 4. S Pass17: With effect of 1 July 2011, S Pass is for mid-skilled employees who earn a fixed monthly. 治 政 大 employer‘s quota eligibility and applicant‘s qualifications. 立. salary of at least $2,000 (previously S$1,800). Its applicants are assessed based on Instead of a degree, a. technical diploma is acceptable for this kind of work pass.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. These work passes are generally issued to high-skilled or mid-skilled foreign workers.. y. Nat. For low-skilled or unskilled foreign workers, they need to apply for ―work permit‖ (WP)18.. er. io. sit. The duration of a Work Permit is generally two years, subject to the validity of the worker‘s passport, the Banker‘s/Insurance Guarantee, and the worker‘s employment period,. al. n. v i n whichever is shorter. The worker C his only allowed toUwork for the employer and in the engchi specified occupation and is not eligible to apply for permanent residence or citizenship in Singapore.. 17. With effect from 1 September 2012, S Pass and Singapore employment pass holders earning at least S$4000 can apply for Dependant Pass. 18 A work permit is issued initially for 2 years and can normally be renewed up to 18 years; from 1 July 2012, basic skilled construction Work Permit workers would be allowed to work up to a maximum of 10 years, while higher skilled workers would be allowed to work up to 18 years (available: http://www.mom.gov.sg/foreign-manpower/passes-visas/Pages/default.aspx). 26.

(34) Table 5: Types of Singapore’s Work Permit Schemes Personalized Employment Pass (PEP). Employment Pass (EP). Entrepreneur Pass (Entre Pass). Validity. issued for 3 years and non-renewable. First time issued for up to 2 years and renewable. issued for 1 year and renewable. issued for 1-2 years and renewable. issued for 2 years and renewable. Eligibility. Well paid professionals who want to work in Singapore for an employer. Company owners and professional staff with tertiary education and relevant experience. Business owners who wish to incorporate a new company or have just incorporated a company that is less than six months old. Mid-level technical staff. Low/unskilled worker. Quota System. No. No. No. Permanent Residence Eligibility. Yes. Yes. Types. S Pass. 政 治 大. 立. Yes. Work Permit (WP). Yes. Yes. Yes. No. * Source: http://www.guidemesingapore.com/relocation/work-pass/singapore-work-permit-schemes, accessed on. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2 March 2013. n. al. P2 Employment Pass. . sit. Eligibility Criteria. Applicants must earn ≥ SGD $8,000. er. io. P1 Employment Pass. Nat. Pass Type. y. Table 6: Types of Singapore’s Work Passes. v i n C hgood degrees, professional qualifications or specialist skills-set. engchi U. . Applicants must possess acceptable qualification that includes. . Applicants must earn ≥ SGD $4,500. . Applicants must possess acceptable qualification that includes good degrees, professional qualifications or specialist skills-set.. Q1 Employment Pass. . Applicants must earn ≥ SGD $3,000. . Applicants must possess acceptable qualification that includes good degrees, professional qualifications or specialist skills-set.. 27.

(35) S Pass. . Applicants must earn ≥ SGD $2,000. . Educational qualifications o. A degree or diploma. o. Technical certifications are acceptable. i.e. Courses that train applicants to be qualified technician or specialist. These certifications should comprise of at least 1 year of full time study.. Work Permit. . Relevant number of work experience required. . An employer who wishes to employ a Malaysian who already holds a valid WP in Singapore must apply for a separate WP:. . Workers from North Asian Sources/Non-Traditional Source/People's Republic of China cannot be in Singapore when. 政 治 大. their WP applications are being submitted.. 立. . Under the Employment Act, the minimum age for an employee is set at 16 years old. For the purpose of Work Permit application,. ‧ 國. 學. Malaysians must be below 58 years old while non-Malaysians must be below 50 years old at the time of the application.. ‧. Source: http://careers.jobstreet.com.sg/job-search/singapore-employment-pass-scheme, accessed on 2 March 2013. io. sit. y. Nat. er. Table 7: The numbers of foreign workforce. a lDec 2007 Dec 2008 Dec 2009i v n Ch U 99,200 e113,400 n g c h i114,300. n Pass Type Employment Pass (EP). Dec 2010. Dec 2011. Jun 2012. 143,300. 175,400. 174,700. S Pass. 44,500. 74,300. 82,800. 98,700. 113,900. 128,100. Work Permit (Total). 757,100. 870,000. 856,300. 871,200. 908,600. 931,200. - Work Permit (Foreign Domestic. 183,200. 191,400. 196,000. 201,400. 206,300. 208,400. - Work Permit (Construction). 180,000. 229,900. 245,700. 248,100. 264,500. 277,600. Total Foreign Workforce. 900,800. 1,057,700. 1,053,500. 1,113,200. 1,197,900. 1,234,000. Total Foreign Workforce. 717,600. 866,300. 857,400. 911,800. 991,600. 1,025,600. Worker). (excluding Foreign Domestic Workers). 28.

(36) Source: Ministry of Manpower of Singapore, 201219. 2.3 An Open Policy Is Only Applied to Foreign Talents? While government takes an open policy towards ―foreign talents‖, the policy towards low-skilled foreign labor is stricter; government tries to control the dependence on these low-skilled foreign labor through the levies and quotas of work permits, dependency ceilings and qualifications criteria. In other words, Singapore‘s foreign labor policies include a mix of price (levy20) and quantity (work passes and quotas21) instruments as well as quality control (education/skills criteria). Foreign worker levies are payable on work. 政 治 大. permit holders; quotas are imposed on firms employing foreign unskilled and semi-skilled. 立. workers; skills and education requirements are imposed on professionals and skilled. ‧ 國. 學. manpower. Work permits are differentiated by skill level, sending country, permit duration, and sector of work and a variable levy is charged according to classification. Since 1968. ‧. unskilled/semi-skilled foreigners have been allowed into Singapore for employment.. y. Nat. sit. Numbers of foreign unskilled/semi-skilled workers in manufacturing, construction, and. n. al. er. io. domestic service sectors came from ―non-traditional sources‖ (that is, non-Malaysian) such 19. Ch. i n U. v. Source: http://www.mom.gov.sg/statistics-publications/others/statistics/Pages/ForeignWorkforceNumbers.aspx,, accessed on 2 March 2013.. 20. engchi. It is a pricing mechanism to regulate the number of foreign workers (including foreign domestic workers) in. Singapore which was introduced in 1980 and has been fine-tuned over time to meet changing market conditions. Initially a flat levy of S$230 was imposed on non-Malaysian workers employed in the construction sector. In 1982 the levy scheme was expanded to include all non-traditional source workers (retrieved 9 July 2013, from http://www.mom.gov.sg/foreign-manpower/foreign-worker-levies/Pages/levies-quotas-for-hiring-foreign-workers. aspx). 21. Man-Year-Entitlement has been introduced for construction workers as a work permit allocation system for. workers from non-traditional sources (such as Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Myanmar, Philippines) and China since April 1998. The number of foreign workers permitted to work in any construction project is determined by the MYE allocation formula (retrieved 3 March 2013, from http://ifaq.mom.gov.sg/CustomerPages/Themes/mom/Answers.aspx?MesId=3110446&From=Show&TOPV=YES &VMesID=663615).. 29.

(37) as India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Philippines and Thailand have grown due to the growing labor shortage and the attraction of Singapore‘s higher wages. With growing affluence and more available employment opportunities, even the lowly educated Singaporeans are increasingly loath to unskilled jobs or semi-skilled jobs. Employers are also reluctant to hire local workers for these 3D jobs as they are too fussy and turn their backs on requiring shift or weekend work. In addition, Singaporean workers have contended that the wages offered was too low and there is no minimum wage standard to assure their right and maintain their living. On the other hand, Singapore has an open door policy for foreign skilled labor22 to. 治 政 upgrade towards a knowledge-based economy. In Chia大 Siow Yue‘s (2011) study, foreign 立 labor management in Singapore can be divided into four distinct stages:. ‧ 國. 學. 1. The first period:. ‧. It was characterized by severe labor shortage and large inflows of foreign labor from. sit. y. Nat. Malaysia since the late 1970s. Work permits were introduced, accompanied by levies for. io. er. foreign workers in the construction sector, and immigration was extended to non-traditional source countries. Permits were also extended to foreign domestic workers (FDWs) to. al. n. v i n facilitate female labor force participation. for Malaysians were much less C h In general, permits engchi U. restrictive than for foreigners from other countries. 2. The second period:. It began in 1981 with a policy announcement that foreign workers were to be phased out completely by 1986 (except in construction, shipbuilding and domestic services) to stimulus businesses to restructure. However, it was difficult to wean off dependence on foreign labor. As a result, the government abandoned the ―no foreign labor‖ policy, and then took a series of measures for hiring foreign workers: ˙Under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act, employers wishing to hire foreigners 22. It is usually referred to as ―foreign talent‖ in government speeches and in the media. 30.

(38) are. required to apply for work permits, and violators are subject to fines and/or. imprisonment. Rising labor demand was met by extending permits to migrants from a wider group of Asian countries. ˙A comprehensive worker levy system was implemented in 1987 and dependency ratio ceiling were introduced (foreign workers were limited to 50% of a firm‘s total employment). Levies were viewed as a flexible pricing mechanism to equalize the costs to employers of foreign and local labor. Levies were extended to Malaysians in 1989 and the dependency ceiling was lowered to 40%. The criteria for issuing employment passes. 治 政 大 crackdown in China. Hong Kong residents in the wake of the Tiananmen Square 立. and granting permanent resident status were liberalized in 1989, especially to attract. 3. The third period:. ‧ 國. 學. It was marked by robust economic growth in the 1990s and hence the strong demand for. ‧. labor force. In response to employers‘ needs, foreign labor grew rapidly, facilitated in part. sit. y. Nat. by easing immigration restrictions. During the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, there was no. io. er. explicit mass repatriation of foreign workers. Instead, labor unions called for wage adjustments before undertaking retrenchments, with business costs reduced by eliminating. al. n. v i n the tax deduction for foreign worker Central Provident Fund (CPF). A C hcontributions to the engchi U. tight permit allocation system and stricter enforcement measures were introduced in 1998 for the construction sector, in which permit entitlements were issued to main contractors.. Moreover, additional adjustments were made to encourage higher productivity in the construction sector through increases in the monthly levy on unskilled workers (from $440 to $470), and sharp cuts in the levy on skilled workers (from $200 to $100); the widening disparity in levies between skilled and unskilled foreign workers is to encourage employers to hire more foreign skilled workers. 4. The fourth period: It heralded a more restrictive foreign labor policy since 2009 in response to the economic 31.

數據

Outline

相關文件

Retrieved March 8, 2006, from the World Wide Web site: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/publications/EducationalPracticesSeriesPdf/ prac10e.pdf Brophy,

Xianggang zaji (miscellaneous notes on Hong Kong) was written by an English and translated into Chinese by a local Chinese literati.. Doubts can therefore be cast as to whether

Promote Hong Kong economic growth 促進香港經濟增長 Earn foreign exchange to pay for imports賺取外匯支付進口貨品 Government can have more profit tax 政府利得稅收入增加

●

• The Hong Kong Institute of Building Information Modelling 香港建築信息模擬學會. • The Hong Kong Institute of

Botswana general certificate of secondary education teaching syllabus: Food and nutrition. Retrieved June 26, 2006

Korea, Ministry of Education & Human Resources Development, "Organization of the Curriculum and Time Allotment standards,". http://www.moe.go.kr/en/down/curriculum-3.pdf

Despite significant increase in the price index of air passenger transport (+16.97%), the index of Transport registered a slow down in year-on-year growth from +12.70% in July to