Chiao Da Management Review Vol. 30 No. 2, 2010 pp.25-59

供應鏈關條、利益對組織間知識分享之

影響 -SEM 交叉效度檢定

The Impacts of Supply Chain Relational Benefit on

Inter-organizational Knowledge Sharing : Cross

Validation of SEM

劉文良 1 Wen-Liang Liu

環球科技大學 行銷管理系

Department of Marketing Management, Transworld University

摘要:過去有關知識分享的研究主題,大多主要在探討企業內之知識分享 。 由於供應鏈管理思維的興起,研究主題近年來漸漸移向組織間或供應鏈閑之 知識分享。雖然已有學者注意到供應鏈組織閉關條對供應鏈組織間知識分享 有所影響,但卻很少有學者從關條利益的角度來看組織間知識分享的社會交 換行為,更缺乏對其中重要中介因素的暸解,例如,關條承諾與信賴 。 為此, 本研究從社會交換理論的觀點,以台灣製造業為研究對象,並加入信賴與承 諾二項中介影響因素,深入探討供應鏈關條利益對組織間知識分享意願與分 享行為之影響 。 實證結果發現,供應鏈組織閉關條利益中的信心利益會透過 中介變數一關條承諾與信賴,影響知識分享意願 。 而中介變數中的信賴也會 影響關條承諾 。 此外 , 本研究亦檢定跨期的交叉效度以確認本研究結果並非 來自於單期的特殊現象 。 關鍵字:關條利益;知識分享;供應鏈;社會交換理論

Abstract: The literature of knowledge sharing in the past most1y focused on the intemal organization. However, new thinking of supply chain management gradually focused on knowledge sharing within the supply chain. Although

I Corresponding author: Department ofMarketing Management, Transworld University, Yunlin

26 The lmpacls ofSupply Chain Relarional Benejìr on lnter-organizalional Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation of SEM scholars have noticed that supply chain relationships int1uence knowledge sharing of the supply chain, few scholars have examined knowledge sharing of supply chain in terms of relationship benefits and its intervening variables such as commitment and trust. Using Taiwanese manufacturing companies as the research subjects, this research examines the int1uence of relationship benefits as well as commitment and trust on supply chain knowledge sharing. This research shows that: (1) the relationship benefits of supply chain int1uence supply chain knowledge sharing, (2) commitment and trust mediate the relationship between relationship benefit and knowledge sharing. The results were cross-validated. Commitment and trust thus play key roles in companies' willingness to share knowledge with their suppliers.

Keywords: Relational Benefit, Knowledge Sharing, Supply Chain, Social Exchange Theory

1.

Introduction1.

1 Research Background and Motivation

Peter Drucker (1998), in his Managing in a Time

0/

Great Change, mentioned that“knowledge has become a key economic resource which

dominates the possibly only source of competitive advantage." It is indeed true that knowledge has become a key determinant of competitive advantage (Forayand Lundvali, 1996; Asheim and Dunford, 1997; Morgan, 1997; Crone and Roper,

2001; Warkentin et al., 2001).

Shin (2004) believed that efficient knowledge management plays a key role in a company's future success. The objective of studying and implementing knowledge management is to create efficient knowledge sharing among organization members (Davenport and Prusak, 1998; Nonaka, et al., 1998; Desouza, 2003). In studies on strategy management of inter-organizational relationships (IORs), Dyer and Singh (1998) pointed out that an organization often cooperates and interacts with external organizations to gain knowledge. This kind of knowledge sharing creates competitive advantage called “relational rents."

Chiao Da Management Reνiew 均 1. 30 No. 2, 2010 27

Mol1er and Svahn (2004) also discovered in studies on inter-organizational interaction that members in a network must develop common knowledge and vision, and that only knowledge sharing can create and sustain common knowledge and understandi月(Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Larsson et al., 1998;

Araujo, 1998).

Supply chain management (SCM) is a crucial issue for many industries. Organizations have begun to realize the importance of integrative relationships among suppliers, cIients, and other stakeholders. Hol1and (1995) suggested that knowledge sharing has become a norm among supply chain members since it enhances competitive advantage of the whole supply chain, benefiting each supply chain member through cooperation. Companies even encourage suppliers to comply with the shared process to coordinate inter-organizational activities and improve product quality. In response to Hol1and (1995), BelJ et al. (2002)

discovered in a study on the knowledge market the fol1owing three reasons for inter-organizational knowledge sharing: (1) for the supply end, to seek potential partners extemal1y through the process of knowledge sharing; (2) for the demand end, to gain the state-of-the-art technology through the process of knowledge sharing; and (3) for the demand end, to acquire know1edge on product development processes recognized by intemationa1 standards through the process ofknowledge sharing.

Due to the urgency and importance of know1edge sharing, studies on knowledge sharing mostly focus on the strategy of know1edge sharing within organizations or the individual intent or behavior of knowledge sharing in organizations (Dixon, 2000; Hendriks, 1999; Kolekofski and Heminger, 2003;

Krogh, 2002; Liebeskind, 1996; Ryu et al., 2003; Senge, 1998; Shin, 2004). As for the few studies on IORs and knowledge sharing, most view the relationship strength and factors affecting inter-organizational knowledge sharing as key factors in the same level but in different categories. Until recently, no one has separated the relationship variable from inter-organizational knowledge sharing as an intermediate dimension and analyzed the potential causal relationships therein.

Norms of inter-organizationa1 knowledge sharing create competitive advantage in organizational relationships. Both the leaming capacity of specific

28 Thelmpac的 ofSupplyChain Relational B研究fìton Inter-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation ofSEM members and the fashion of encouraging knowledge sharing affect the norms of inter-organizational knowledge sharing (Dyer and Singh, 1998). Besides creating synergies of knowledge, practice of knowledge sharing also has a negative impact on knowledge owners (Loebecke et al., 1999). In other words, in the process of knowledge sharing, if a knowledge owner expects that a recipient's certain attribute will reduce the knowledge owner's value in monopolizing knowledge and increase competitiveness, there is a paradox for inter-organizational knowledge sharing. Next, when organizations share common values and have

aligned objectives, they trust each other more and are willing to make commÎtments. This is beneficial to mutual understanding and knowledge sharing, which multiplies the benefits of inter-organizational knowledge sharing. As a result, we separate relationship commitment and trust to be independent intermediaries and study how supply chain relationship benefits affect knowledge sharing directly or through intermediaries to build a comprehensive 企'amework. 1.2 Research Purposes

The Iiterature review and framework are based on key factors in inter-organizational knowledge sharing. We use the supply chain relationship benefit as an intermediary transferring the causal relationship, in order to study factors affecting both the inter-organizational competition and knowledge sharing, and then study factors directly or indirectly worsening or multiplying the relationship of the two. In addition, we propose factors affecting only relationship benefits or knowledge sharing in the supply chain to build a comprehensive theoretical structure for the industry and to promote inter-organizational knowledge sharing. In sum, the objectives of the study include the following:

l.To test whether supply chain relationship benefits significantly affect the willingness of inter-organizational knowledge sharing

2.To test how the intermediate role of relationship commitment and trust in supply chain relationship benefits affects inter-organizational knowledge sharing

3.To study how dimensions of relationship benefits, including social benefits, confidence benefits, and special treatment benefits, affect knowledge sharing

Chiao Da Management Revi軒vVo/. 30 No. 2, 20/0 29

4.To increase the validity of the study, besides testing the reliability and validity of measurement variables, we use inter-temporal cross-validity to test if the model is consistent to gain robust results

2.

Literature Review2.1.

Supply Chain ManagementThe increasingly intense competition among businesses has drawn more attention to vertically- or horizontally-integrated supply chain management.

Supply chain management, according to Stevens (1989), inc1udes the planning,

coordination, and control of materials, parts, and end products between suppliers and c1ients. Cooper and Ellram (1993) and Weele (2002) believed that supply chain management integrates the distribution channel flow from suppliers to end customers.

Oliver (1990) defined IORs as the relatively sustainable 甘ades , flows, and links between an organization and one or more organizations. Aldrich (1979) pointed out early that organizations establish relationships with others in order to gain or exchange resources. The collective power of IORs is beyond what an individual organization can achieve.

Kumar and Dissel (1996) summarized the following five motivations for forming IORs: (1) sharing resources, (2) bearing ri仗, (3) creating comparative

advantage, (4) reducing supply chain uncertainties, and (5) increasing resource application.

Dyer and Singh (1998) applied IORs to the study of inter-organizational competitive advantage and cooperative strategies. They believed that IORs are the key resource creating competitive advantage for organizations. They called such a key resource "relational rents." There are four sources of relational rents,的

follows: (1) investrnent in relationship-specific assets, (2) the norm ofknowledge sharing, (3) complementary resources and capacities, and (4) effective management.

30 The Impacts ofSupply Chain Relational B研究所 onInter-organizational

的。"必句eSharing - Cross Validation

relationships are often interchangeable. Vokurka (1998) defined partnership as an agreement between the buyer and seller, which inc1udes information sharing across time and distance and shares risks and interests resulting 企om the relationship. Lewin (2003) defined the buyer-seller relationships to be purposeful strategic relationships among individual companies whereby parties strive for common interests with a high level of trust, commitme肘, and flexibility.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) believed that an organization has the following four types of partnerships: (1) supplier partnership, inc1uding raw material or service suppliers; (2) lateral partnerships, including competitors, non-profit organizations, and governments; (3) buyer partnershi阱, inc1uding intermediate

and end customers; and (4) internal partnerships, including internal company functions, employees, and business units. In addition, Morgan and Hunt (1994)

。bserved that trust and commitment are key intermediaries determining the success of partnership, because trust and commitment encourage organizations to cooperate with partners for maintaining investments in relationsh中, focus on current partners' potentiallong-term interests and ignore short-term benefits

,

and reduce potential high risks because partners are not opportunistic. As a result, the high degree of trust and commitment among pa此ners makes the relationship marketing successful and increases the performance, efficiency, and productivity of inter-organizational activities.Asanuma (1989) and Dyer (1996) both pointed out that the upgrade ofthe industry value chain takes place because partners are wi11ing to invest in specific relationships and combine inter-organizational resources in a unique way, which maximizes outputs of inter-organizational resources. Jap (1999) also noticed that it is worthwhile for supply chain members to be devoted to the buyer-seller partnership, because the shared efforts and investments in mutual relationship create mutual benefits and strategies, making them more profitable and realizing competitive advantage.

As a result, Weele (2002) observed that the key to successful supply chain management is to build a strategic partnership with supply chain partners. Further, Tyan and Wee (2003) suggested that the supply chain connects internal organizational units and other partners such as external suppliers

Chiao Da Management ReviewVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 31

logistics; such alliance encourages managers to cooperate with successful companies, which enhances the competitive advantage of the entire supply chain and creates long-term benefits for the partnership.

In sum, in a highly competitive environment, companies create partnerships to share information, production processes, and knowledge, which is mutually beneficial. However, the quality and maintenance of partnerships rely on mutual trust and commitment. As a result, how to use and manage relationships with other organizations to strengthen supply chain production and communication efficiency as well as maximize profits and customer satisfaction through cJose connection and cooperation among distribution members has become the biggest issue for organizations.

2.2.

Knowledge Management and Knowledge SharingSenge (1998) defined knowledge as

“

the capacity of active action."Davenport and Prusak (1998) illustrated the difference among data

,

information,

and knowledge, as follows. Data is a set of discrete and objective facts about events. For an organization, the trading record is a data. We cannot concJude the reason for cJient visit or customer satisfaction from the data. Information is similar to a message, usually presented as a document, representing visible or audible context, while knowledge combines personal experiences and values; it is the capacity to interpret information and apply information for problem solving. Organizational knowledge is created internally and also obtained from external environments (Lee, 2001).According to the perspective of resource dependence theory, IORs are an exchange between two or more organizations for obtaining key or scarce resources (Aldrich, 1979; Baranson, 1990). Limitations on resources and capacities create simultaneous competitive and cooperative relationships between organizations (Brandenburger and Nalebuff, 1996). Knowledge is the source of organizational competitive advantage. As a result, even though inter-organizational knowledge sharing among supply chain members facilitates the understanding of specific knowledge and enhances mutual benefits by achieving common goals, it also makes learners more competitive, thus creating

32 The Impacts ofSupply Chain Relational Benejìt on Inter-organizational

的。"必dgeSharing - Cross Validation of SEM

the potential crisis of imitation (Loebecke et al., 1999).

Knowledge sharing, according to Dixon (2000) in his work on knowledge-sharing organizations, refers to the exchange ofknowledge. Lee (2001) defined knowledge sharing as the knowledge transfer and dissemination by individuals, groups, or organizations. According to Krogh (2002), knowledge sharing as a key process in many knowledge management activities, inc1uding the acquisition, transfer, and creation of knowledge. Ryu et al. (2003) explained knowledge sharing as the process of interpersonal interactions in knowledge management. Boer et al. (2004) defined and argued knowledge sharing to be a basic social phenomenon.

2.3. Social Exchange Theory and Knowledge Sharing

The reason why this study is applicable to the social exchange theory is explained hereafter. Literature (LaGaipa, 1977; Nye, 1979; Emerson, 1981) indicates that typical social exchanges follow three assumptions, as follows: (1)

Social behaviors are a series of exchange. (2) Individuals 仕Y to maximize rewards and minimize costs. (3) When an individual gains rewards from a third party, he/she feels obliged to return the favor. In our study

,“

knowledge sharing" is a social exchange. When a party transfers knowledge to another pa此y, it expects to receive similar feedback. As a result, knowledge sharing is definitely a social exchange. The parties involved try to minimize costs and maximize returns, and returns are given in tangible or intangible forms. Therefore, knowledge sharing satisfies the three assumptions in the social exchange theory.Basically, the social exchange theory was deve10ped in the 1950s,

represented by the following contributions of four theorists: (1) Exchange Behaviorism by Homans (1958), (2) Exchange Outcome Matrix by Thibaut and Kelley (1959), (3) Exchange Structuralism by Blau (1964), and (4) Exchange Network by Emerson (1972).

Homans (1958) is the founder of the social exchange theory. He proposed the exchange theory on the

“

individual" leve1. Later, Blau (1964) and Emerson (1972) applied the social exchange theOIγto practice. Blau (1964) expanded the social exchange theory to the“

macro" level, emphasizing the importance orChiao Da Management Rev悶wVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 33

nonns

,

that is,

exchanges under socia1 systems and fonna1 organizations. Emerson (1972) integrated the“

individua1" and“

macro" 1eve1s, focusing on socia1 networks.Exchange behaviorism in Homans (1958) indicated that individua1s are willing to continue certain behaviors because they will gain rewards, judging from past experiences. Converse1y, if previous experience proves such behaviors to require sacrifices, then the individua1 will stop such behavior. In other words, to understand behaviors, one must first realize the individua1's payoff history. Homans (1958), in studies on socia1 behaviors, observed that interpersona1 interaction is a process of exchange, where the parties invo1ved exchange va1uab1e resources as rewards for engaging in re1evant tasks or activities. In the exchange-reward scenario, the parties continually adjust its resources in order to meet the counterpart's needs and sustain a 1asting re1ationship.

The exchange outcome matrix in Thibaut and Kelly (1959) is a conceptua1 too1 ana1yzing the parties' interactions based on the outcome matrix. The outcome matrix points out participants' behaviors and outcomes of a party's behavior accompanied by the other party's re1ative behaviors. The outcome of interactions is the rewards of the parties' behaviors excluding the costs of action.

Exchange structura1ism in B1au (1964) broadened the theory in Homans (1958) from individua1 exchanges to organizationa1 exchanges. B1au (1964) pointed out that trust and commitment are two important dimensions in the social exchange theory and be1ieved that socia1 exchanges differ 企om economlC exchanges based on rationa1 cost-benefit ana1ysis in the following aspects. (1)

Benefits 企om social exchanges are often greater than that of economic exchanges,

such as the 企iendship or support resu1ting thereof. (2) Socia1 exchanges are often spontaneous, and the parties do not need to enter fonnal agreements. (3) The resource-providing party expects to receive the same level of return. In general,

socia1 exchanges are often spontaneous or vo1untary, and feedback is not mandatory. The willingness to exchange is based on the expected social rewards,

and then the parties adjust and detennine the extent and period of resource exchange accordingly.

34 The Impacts 01 Supply Chain Relational Be,呵ìton Inter-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation 01 SEM

“

dependency,"“

power," and“

balance" in a relationship. Emerson (1972) focused on the role of power in the social exchange. He believed that parties of the exchange determine the "relative power" according to the“

relative dependency." The power comes from the control of resources needed by the other party. In a business relationship, such relative dependency affects behaviors of the“

more dependent party."Morgan and Hunt (1994) applied the social exchange theory to relationship marketing. The foundations of the social exchange theory-trust and commitment-are the key intermediaries for the success of relationship marketing. They proposed the well-known key mediating variable (KMV) model.

Bagozzi (1978) believed that the interaction of social exchange is more than economic trading decisions; results of exchange are also affected by other non-economic factors, such as trust and commitment. In sum, the social exchange theory has a tremendous impact on the key concepts in knowledge sharing, such as trust and commitment.

3.

Research Model and HypothesesBasically, knowledge sharing is also an interpersonal social exchange; the sharing creates knowledge flow. In fact, the social exchange of knowledge is similar to exchange of goods in economics, the only difference being that the return or rewards for a social exchange may not be monetary or physical. As a result, based on the social exchange theory, we introduce two intermediaries,

“

trust" and“

commitment," in order to study how supply chain relationship benefits affect inter-organizational knowledge sharing. Our model is shown in Figure 1.3.1. Relationship Benefit

In general, business clients evaluate benefits derived from the buyer-seller relationship to determine whether to build a relationship with the supplier. These benefits inc1ude the core service or relationship itself, and the 1a往前 is the concept

Chiao Da Management ReviewVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 35

Beatty et al. (1996), Gwinner et al. (1998), Zeithaml and Bitner (2000), and Hennig-Thurau et al. (2002) discovered that business clients wish to gain three types of relationship benefits from an established relationship with a supplier,

namely confidence benefits

,

social benefits,

and special treatment benefits. Confidence benefits are client-perceived trust and lower risks in the long-term relationship. Social benefits comprise the 企iendship, familiarity, or recognition between business clients and suppliers; social benefits also include the pleasant atmosphere between the parties. Such a relationship satisfies some emotional needs of business clients. Special treatment benefits refer to the convenienc巴,price discount, privileged services, or saved time that business clients gain from the supply relationship. In our study, we apply the three dimensions to studying relationship benefits.

Figure.l

Research Model and Hypotheses

--

--

---

-

---Relationship Benefit Confidence Benefits

Social Benefits

Special Treatment Benefits

---_

_

____1

3.2.

Relationship Commitment Relationship Commitment Trust Knowledge SharingMorgan and Hunt (1994) believed that the relationship benefit is a key determinant in relationship commitment. The higher the client-perceived relationship benefits, the higher the relationship commitment. Relationship benefits can include product profitability, cost saving, and product performance. As a result, parties in the client-business relationship both want to benefit from customer retentlOn.

36 The Impacts

01

Supply Chain Relational B研究fìton Inter-organizationalKnowledge Sharing - Cross Validation

01

SEM Hl: The higher the supp/y chain“

're/ationship ben昕俗'," the higher theinter-organizationa/ 句e/ationship commitmenι"

Gwinner et a/. (1998) and Zeitham1 and Bitner (2000) pointed out that

re1ationship benefits include socia1 benefits, confidence benefits, and specia1 treatment benefits. As a result, Hl is divided into three sub-hypotheses: Hla, Hlb,

andHlc.

Hla: The higher the supp/y chain “COl吧fidence ben祕丸 " the higher the inter-organizationa/

“

re/ationship commitmenL "Hlb: The higher the supp/y chain

“

socia/ ben胡島 " the higher the inter-organizationa/“

re/ationship commitmenι"Hlc: The higher the supp/y chain 句pecia/treatment ben胡島 "the higher the inter-organizationa/

“

're/ationship commitmenL"3.3.

Tr

ust

Bendapudi and Berry (1997) and Chaudhuri and Ho1brook (2001) both believed that re1ationship benefits affect trust. As a resu1t, we propose H2.

H2: The higher the supply chain

“

relationship ben昕'ts,"

the higher the inter-organizationa/ "trusL"Gwinner et a/. (1998) and Zeitham1 and Bitner (2000) noted that re1ationship benefits include socia1 benefits, confidence benefits, and specia1 treatment benefits. As a result, H2 is divided into three sub-hypotheses-H2a, H品, andH2c.

H2a: The higher the supp/y chain

“

Confidence ben胡的 " the higher the inter-organizational“

'trust. "H2b: The higher the supply chain

“

'socia/ benφIS," the higher the inter-organizationa/ “trusι"H2c: The higher the supply chain

“

'special treatment benefits, "

the higher the inter-organizational “trusι"Chiao Da Managemenl ReviewVol. 30 No. 2, 20/0 37

factor in the process of social exchange. The social exchange theory assumes that with the passage of time, both parties in the exchange process demonstrate that they trust the exchange relationship by relationship commitment. Davenport and Prusak (1998) pointed out that trust is an important factor improving the efficiency of knowledge sharing, which promotes positive knowledge transfer. As for the relationship between trust and commitment, according to the social exchange theory, the parties will have lower commitrnents in the exchange relationship if they do not trust each other, thus transforming the original long-term exchange relationship into a short-term trading relationship (McDonald,

1981). In addition, Achrol (1991) pointed out that trust is a key factor to commitment. Hrebiniak (1974) believed that trust creates a high value to cooperation, and the parties want to commit themselves to the relationship. As a result, we believe that 前ust in supply chain members affects inter-organizational relationship commitment. We propose H3 as follows:

H3: The higher the “:trust" 的 supply chain members

,

the higher theinter-organizational

“

relationship commitmenι"3.4.

Knowledge SharingNo matter what organizations build relationships for,恥的tand commitment are essential factors for creating and sustaining IORs (Mogan and Hunt, 1994; Wilson, 1995; Mentzer et al., 2000; Dyer and Chu, 2000). They affect the

wil1ingness as well as behaviors of inter-organizational knowledge sharing (Soekijad and Andriessen, 2003; Moller and Svahn, 2004).

The willingness of knowledge sharing refers to how willing supply chain members are to inform other members; it measures supply chain members' intention level ofknowledge sharing.

H4: The higher the supply chain

“

:relationship commitment,"

the higherthe

“

willingness 01 knowledge sharing. "Trust implies that the resource-owning party, even though under risky conditions, believes and expects the counterpart to do things or have intentions that are beneficial or at least not harm臼1 to it. Lewicki and Bunker (1996) found

38 The Impacts of Supply Chain Relational Bel崢ton Inter-organizational Knowledge Sharing- Cross Validation ofSEM

that as the trust grows, the parties increase the inforrnation and knowledge transfer. In other words, they are more willing to share knowledge. As a result, we proposeH5

H5: The higher the

“

trust" among supply chain members,

the higher the“

willingness ofknowledge sharing" among organizations.4. Methodology and Study Setting

4.1.

Measures ofVariables4.1.1. Relationship Benefits

Gwinner et al. (1998) suggested that relationship benefits inc1ude t趾ee dimensions, namely social benefits, confidence benefits, and special treatment benefits. The definitions and measurement of these dimensions are as follows. (1) Social benefits: These inc1ude social interactions such as the identity, familiari旬, and 企iendship between supply chain members (Gwinner et al., 1998; Patterson and Smith, 2001) to satisfy their emotional needs. (2) Confidence benefits: Supply chain members prefer social interactions to be stable, trust-worthy (Patterson and Smith, 2001), worry-free, and comfortable (Gwinner et al., 1998). (3) Special treatment benefits: These mainly refer to economic benefits such as privileged prices, faster services, and special add-on services as a result of the relationship (Gwinner et al., 1998).

There are eleven measurements in the survey; four are on confidence bene伍的, three on social benefi筒, and four on special treatment benefits. The assessment is done on a 7-point Likert scale, and respondents indicate the extent to which they agree with the statements (1 represents totally disagree, and 7 represents totally agree). The survey is designed in reference to Gwinner et al

(1998), Hennig-Thurau et al. (2002), Patterson and Smith (2001), and Sweeney and Webb (2002).

4.1.2. Relationship Commitment

According to definitions in Meyer and Allen (1997), we define commitments in IORs to be “supply chain members' commitments to the supply

Chiao Da Management ReviewVo/. 30 No. 2. 2010 39

chain." There are four measurements in the survey, including supply chain members give us appropriate feedback, broaden our knowledge, provide us with the information we need, and allow us to share company knowledge. We adopt Likert's 7-point scale; respondents indicate the extent to which they agree with the statements (1 represents totally disagree, and 7 represents totally agree). The survey is designed in reference to Meyer and Allen (1997).

4.1.3. Trust

According to Doney and Canon (1997), trust means that one party acknowledges another's goodwill. Anderson and Narus (1990) suggested 仙st to mean that one believes that the other does not do things harmful to himlher and is happy to help himlher. In the study, trust is defined as “supply chain members acknowledge the goodwill and willingness to support one another."

Measurements in the survey include happy to help other supply chain members,

treat supply chain members sincerely

,

actively assist supply chain members in solving problems,

and do not do things that are harmful to supply chain members. We adopt the 7-point Likert scale; respondents indicate the extent to which they agree with the statements (1 represents totally disagree, and 7 represents totally agree). The survey is designed in reference to Anderson and Narus (1990) and Doney and Canon (1997).4.1.4. Knowledge Sharing

Senge (1998) believed that knowledge sharing is

“

to help others develop effective capacities." As a result, we define knowledge sharing to be "the willingness of supply chain members to help others develop effective capacities." We adopt the 7-point Likert scale; respondents indicate the extent to which they agree with the statements (1 represents totally disagree, and 7 represents totally agree). The survey is designed in reference to Bock and Kim (2002).4.2.

Survey4.2.1. Pretest and Pilot Test

The survey is conducted to modify the questionnaire in order to avoid fuzzy wording or improper statements, which increases the survey's content validity (Churchill, 1979). We invited seven experts to modify the questionnaire and

40 The Impacls ofSupply Chain Relational B研究fiton Inter-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation of SEM randomly selected 30 manufacturing companies in the sample. Each company answered one test survey, and the wording was modified accordingly to reduce ambiguities.

4.2.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

This study applies the self-report table for measurement. Podsakoff and Organ (1986) observed that if the data is collected from a single survey sent to a group of subjects and contains both independent variables and dependent variables, then the problem of common method variance (CMV) may occur. To avoid this potential challenge, we exercise some precautions in reference to Podsakoff et al. (2003). Some examples of these precautions are as follows. (1) Omitting information ofthe respondent: To increase the respondent's trust and the authenticity of survey contents, respondents in the survey are anonymous; the survey is collected in sealed mails. (2) Isolated data collection: The psychological isolation method is applied. The questionnaire specifies that each question is independent, in order to avoid biased answers. (3) Reverse question design: In the "trust" dimension, the design of reverse questions is employed. (4) Wording and organization of the statement: Simple and comprehensible question items are used Challenging and complicated statements are avoided, for example, avoiding two questJons or two negatlve statements m one ltem.

4.2.3. Sample and Data Collection

The population of the study was Taiwan's 1500 largest manufacturing companies listed in the Common Wealth Magazine 2005. We randomly selected half of the population (750 companies) as our sample. The questionnaires were mailed or sent in person to company representatives (the president or CEO), who then transferred the questionnaire to the person acωally in contact with suppliers (the head of purchasing) or a senior staffer in charge of actual purchasing. They answered questions according to their experience with their key suppliers. In order to test cross-temporal validity, questionnaires were issued in two stages. Term 1 questionnaires were issued on April 15, 2006, and Term 2 questionnaires were issued on April 15, 2007. After the first dissemination and follow-ups, we received 211 valid questionnaires 企om T erm 1, and the valid response rate was 28.13%. In Term 2, we collected 215 valid questionnaires, and the valid response

Chiao Da Management ReνiewVo/. 30 No. 2, 2010 41

rate was 28.7%. The valid response rates were similar to that in Wu et al.'s (2006)

study (28.25%) published in the Journal of Information Management. Therefore,

our sample rate was reasonable and acceptable. In addition, to increase the

validity, we conducted the structural equation modeling (SEM) inter-temporal

cross-validity test.

To ensure that samples were representative, we divided the 211 samples

collected in Term 1 into two subgroups (139 samples vs. 72 samples). We

selected the respondent's title, company annual sales, and years in business, and

then applied the chi-square test. Results are shown in Table 1; there was no

significant difference in the two subgroups. As a result, we assume that the

uncollected samples did not cause a significant bias (Armstrong and Overton,

1977). Descriptive statistics of the effective samples is shown in Table 1.

4.3.

Measurement ModelThis study utilized LISREL 8.3 to test and verify how the model fit the

theoretical model. During data processing, parameters were estimated by the

built-in maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) 如nction. Given the MLE's

assumption that the data must be multivariate normal distribution, the sample size

cannot be too small and should comprise at least 100-150 samples (Ding et al.,

1995). After eliminating invalid samples, we had an effective sample size of 211

The standardized residuals of the Q-plot slope did not violate the normal

distribution assumption, which met the above criteria.

The measurement model studies the following two aspects: (1) whether the measurements in the test model accurately predict the latent variables in the entire

model, and (2) whether there are complicated measurements loaded in different

factors (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). In other words, there are two important

construct validities in the test model, namely convergence validity and

discrimination validity. For the convergence validity, different measurements for

related variables are supposed to have highly correlated results; that is, the results

should be the same if the same object is measured. For the discriminant validity,

when measuring different concepts, irrespective of whether or not the method is

42 The lmpacts ofSupp/y Chain Re/ationa/ Bel呵lton Inter-organizationa/ Know/edge Sharing - Cross Validation 01 SEM

Bagozzi and Yi (1988), we choose four typical indicators to evaluate the measurement model. Results are demonstrated below.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Chi-Square Test for The Sample

Number % Chi戶-square d.f p-value

Position

General manager/CEOlPresident

Purchasing manger/purchasing head Purchasing specialist

Annual revenue (in NT$ \00 million) 10 or below 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-100 \00 and above lndustry

Electronic machinery indus吋

Machinery and equipment Electronic components

Transport equipmentlpa口sand

components

Chemical engineering

Textile

Basic material

Printing and supports

Food

Non-metallic mineral products Others Company history 6 years or below 6-10 years 11-15 years 16-20 years 21-25 years 26-30 years 30 years or more • P-value < 0.05 “ υny 反 U -Enyny 7.58 46.92 45.50 2.537 2 487 4U 勻 ,any-A 。。 A 且可 1a 司 3 月,, 勻 ,包勻 , h ,且,且勻 , -17.06 34.12 13.74 9.95 8.53 6.64 9.95 6 975 1.212 MH 口 ωω 20.85 8.06 4.74 4.74 7.091 10 713 AUA 斗 nυAUTQO 弓 , 呵 , L 句3 呵 ,, -z-1 、 3 3.32 9.48 16.11 3.32 4.74 6.64 18.00 r o--究 d 可 M 《 d 吋白 , h 《峙 , 而 J 伽司‘ J 令‘ J 呵 , 缸吋 J u r hv 4.27 12.32 14.69 16.59 10.90 11.85 29.38 6 4.749 571

Chiao Da Management ReνiewVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 43

1.Reliability of individual items: The indicator evaluates the factor loading of a measurement on a latent variable to test the statistical significance of a variable's loading. In the analysis of factor loadings, the significance is determined by t-tests. Higher t-values suggest stronger intensity, and the result is significant if the absolute t-value exceeds 1.96. The standardized factor loadings of individual measurements are all above 0.5, and the t-values are above 1.96. As a result, the survey had a solid measurement quality and the statements had a high fitness.

2.Composite reliability (CR): A latent variable's CR is composed of the reliability of the latent variable's entire measurements, which shows the intemal consistency of indicators. Higher CR suggests higher intemal consistency. Fomell and Larcker (1981) suggested CR values to be above 0.6. According to Table 2, the CRs in different dimensions are above 0.6 (between 0.87 and 0.95), indicating a good intemal consistency.

3.Average variance extracted (AVE): AVE calculates the average power of a latent variable's measurements on the latent variable's variance. A higher A VE suggests that latent variables have higher reliability and convergence validity. Fomell and Larcker (1981) suggested AVEs to be higher than 0.5. According to Table 2, A VEs for different items are all higher than 0.5 (0.66-0.82), showing that the latent variables in this study had good reliability and convergence validity.

4.Discriminant validity: The discriminant validity measures the difference among measurements of the dimensions. According to Fomell and Larcker

(1981), the criteria for discriminant validity is that the A VE shall be larger than the squared correlation coefficients of other dimensions. The values in Table 3 satis今 the above criteria; as a result, the mode1 had good discriminant validity. Take the smallest A VE value, the special treatment benefit, for example (the A VE value is 0.66). The largest correlation coefficient of special treatment benefits and other dimensions is 0.80, and the squared value is 0.64, which is less than 0.66 and satisfies the criteria.

44 The lmpacts of Supply Chain Relational Benefit on lnter-organizational Knowledge Sharing-Cross Validation ofSEM

Table 2

ResuIts of the Measurement Model

Cons甘uct CR AVE Confidence Benefits (CB) Social Benefits (SB) Special Treatment Benefits (STB) Trust (T) Item Factor loadin皇 CB 1: supply chain partners are not Iikely to 0.79 make mistakes

CB2: supply chain partners are trustworthy 0.81 CB3: supply chain partners make me feel 0.56 secure and safe

CB4: supply chain partners provide accurate 0.75 servlces

SB 1: 1 feel affiliated in the interactions with 0.61

supply chain partners

SB2: 1 feel happy in the interactions with 0.64 supply chain partners

SB3: 1 feel important in the interactions with 0.66 supply chain partners

STB 1: supply ch剖n partners offer me better 0.56 servlces

STB2: supply chain partners offer me better 0.61 servÎces price discounts

STB3: supply chain partners offer me 0.65 time-saving services compared to others

STB4: supply chain partne自 satisfy my special 0.51 needs

T1: happy to assist supply chain members T2: treat supply chain members since閃Iy

。 67

0.73

T3: actively help supply chain members solve 0.69 problems

T4: do not do things that harm supply chain 0.62 members

Commitment CI: provide proper knowledge feedback to our 0.51

(c)

Knowledge Sharing

(KS)

company

C2: broaden our company's k.nowledge C3: provide the infonnation we need C4: allow us to share company knowledge

。 6日 0.87 0.84 Standard error 0.10 0.05 0.23 0.10 。 16 , 。 18 。 23 0.16 。 18 。 21 0.17 0.10 0.08 0.11 。 27 。 55 情 d1 凶 ,、 d AU 『 有 dAυAV 弓 , nvnuaunυ 。 14 。 29 。 32 t-value 17.28 18.69 12.74 17.02 14.11 14.24 13.54 13.40 13.84 12.99 9.59 16.33 17.31 16.32 12.72 8.62 12.61 19.85 19.04 14.18 15.83 12.94 11.94 。 95 0.82 0.87 0.68 0.88 0.66 0.93 0.77 0.90 0.69 0.89 0.67

x

2/d.f. = 1.827; AGFI = 0.80; NFI = 0.90; NNFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.95; RFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.061 KS 1: willing to share knowledge with supply 0.73chain members

KS2: it is beneficial to share knowledge with 0.76 supply chain members

KS3 it is a pleasant experience to share 0.68 knowledge with supply chain members

KS4: it is worthy to share knowledge with 0.66

Chiao Da Managemenl ReviewVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 45

Table 3

Variance Extracted and The Squared Correlation Coefficients

Construct CB SB STB T C KS

Confidence Benefits (CB) 0.82

Social Benefits (SB) 。42 0.68

Special Treatment Benefits (STB) 。 28 0.64 0.66

Trust (T) 。 21 。 15 。 10 。 77

Commitment (C) 0.29 。29 。.24 0.19 0.69

Knowledge Sharing (KS) 0.14 0.08 0.06 0.10 0.18 0.67 note: The diagonal line is the dimension's AVE value; non-diagonal items are the squared corτelation

coefficients of the dimensions

In addition, the results in the Tenn 2 measurement model were similar to the Tenn 1 model. The standardized factor loadings of individual variables were above 0.5, and all t-values were higher than 1.96. The CRs and the AVEs of the latent variables were above 0.6 and 0.5, respectively. For the discriminant validi旬, the A VE was larger than the squared correlation coefficient of other dimensions Limited by the length of the paper, results of the Tenn 2 measurement model were not presented.

4

.4

Structural Model

The structural model studies the fit and explanatory power of the entire model. In reference to Bagozzi and Yi (1988), Joreskog and Sorbom (1996), and Bentler (1990), seven indicators were selected to evaluate the fitness of the entire model, including the ratio of the chi-square value to the degree of freedom (χ2/d.f.),

吋usted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), nonned fit index (NFI), non-nonned fit index (1'心甘FI), comparative fix index (CFI), relative fix index (RFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Results are summarized in Table 4.According to Table 4, Bagozzi and Yi (1988) believed that the ratios of the chi-square value to the degree of freedom (X2/d.f.) less than 3 are preferable (Cannines and McIver, 1981; Chin and Todd, 1995; Hair et al., 2005). All the ratios ofthe chi-square value to the degree offreedom (χ2/d.f.) in this study are

46 Fit indices χ2/d.f AGFI NFI NNFI CFI RFI RMSEA

The Impacts o[Supply Chain Relational Benefit on lnler-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validalion o[ SEM

Table 4

Fit indices for Structural Models

Suggested Reference Measurement Structural

value result model

三三 3.00 8agozzi and Yi (1988); Hair el al 1.825 2.30

(2005)

全 0.80 DolI el al. (J 994); Hair el al. (2005) 0.80 0.80

這 0.90 DolI el al. (J 994); Hair el al. (2005) 0.90 。.90

這 0.90 8entler and 80nnett (J 980); 8entler 。 94 0.91

(J 990); Hair el al. (2005)

泣 。 90 8entler and 80nnett (J 980); 8entler 0.95 0.92

(J 990); Hair el al. (2005)

孟 0.90 8entler and 80nnett (J 980); 8entler 0.95 0.92

(1990); Hair el al. (2005)

三豆 0.08 Hair el al. (2005) 0.061 0.073

less than 3 (2.30). This indicates that even though the sample was small, the model was still acceptable. Our other indicators also fall into the suggested ranges, as follows: AGFI ~ 0.80 (0.80), NFI ~ 0.90 (0.90), NNFI 三 0.90 (0別), CFI 主

0.90 (0.92), RFI 三 0.90 (0.92), and RMSEA 三 0.08 (0.073). In general, the model fit the data well.

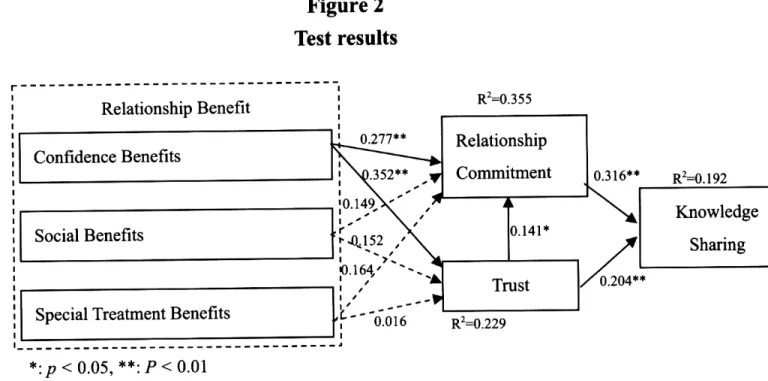

As demonstrated in Table 2 and Figure 5, based on the SEM-estimated path relationships among the dimensions with standardized coefficients (in Term 1), five out of nine hypotheses in the studies are significant atα= O.肘, and four hypotheses are significant atα= 0.01. The following structural path coefficients are slgm日cant: confidence benefits

•

relationship commitment (0.277), confidence benefits•

trust (0.352), trust•

relationship commitment (0.141), relationship commitment•

willingness to share knowledge (0.316),

and trust•

willingness to share knowledge (0.204).In addition, in the SEM structural results in Term 2, the ratio of chi-square to the degree of freedom (χ2/d.f.) is smaller than 3 (2.43). This suggests that the model was acceptable even if the sample was too small. The values of other indicators are within the acceptable range, as follows: AGFI 主 0.80 (0.80), NFI 三 0.90 (0.90),

Chiao Da Managemenl ReνiewVol. 30No. 2, 2010 47

NNFI 主 0.90 (0.91), CFI 三 0.90 (0.92), RFI 三 0.90 (0.92), and RMSEA 三 0.08

(0.079). In general, the model in Term 2 日t the data well. In Term 2, we estimate

the path among different dimensions based on SEM; the path values of standardized coefficients were used to test the nine hypotheses in the study. Five

hypotheses are significant at α= 0.05, and four are significant atα= 0.01. The

path values in Term 2 are described in Tab 5.

Figure 2 Test results r---~ ' Relationship Benefit Confidence Benefits

i

[Social Benefit 』|?令

'.Q~: 抖的, Special T…

t B e n e f i t s l h d r *: p < 0.05, **: P < 0.014.5

Cross-Validity R'9l.355 Relationship Commitment Trust R'9l.229 。 204** R'=o.192 Knowledge SharingIn addition to the measurements' basic reliability and validity, we applied

the cross-validity to increase the validity and test whether the two models had

consistent path relationship 伊 value). We sequentially conducted the Term 1 and

Term 2 SEM analyses, and then substituted the derived chi-square values and

degree of 企eedom of the two SEM models in the F-test to calculate the F-value.

The equation for the F-test is as follows:

:d

/

F=

~

生i

%2/

/

df2

48 The Impacts ofSupply Chain Relational Benefit on Jnter-organizational Knowledge Sharing-Cross Validation ofSEM

Table 5

Hypotheses testing Hypotheses

H1a H1a: The higher the “confidence benefits" in the supply chain, the higher the inter-organizational“relationship commitment."

Hlb H1b: The higher the “social benefits" in the supply chain, the higher the inter-organizational "relationship commitment."

Hlc Hlc: The higher the “special treatment benefits" in the supply

chain, the higher the inter-organizational “relationship

commitment. "

H2a H2a: The higher the “confidence benefits" in the supply chain, the higher the inter-organizational“trust. "

H2b H2b: The higher the “social benefits" in the supp1y chain, the higher the inter-organizationa1“trust."

H2c H2c: The higher the “specia1 treatment benefits" in the supp1y

chain, the higher the inter-organizationa1“trust. "

H3 H3: The higher the “trust" in supp1y chain members, the higher

the inter-organizationa1 "re1ationship commitment."

H4 H4: The higher the "re1ationship commitment" in the supply

chain members, the higher the “willingness of know1edge

sharing." Paths in Tenn 1 (n1 = 211) 。 277" (t =3.138) 。 149 (1=0.906) 。 164 (1=1.237) 。 352'* (1=3.644) 。 152 (1 = 0.986) 0.016 (/=0.105) 0.141* (1 = 2.042) 。 316** (1=4.117)

H5 H5: The higher the “trust" among supp1y chain members, the 0.204** higher the “willingness of knowledge sharing" among (1 = 2.641) orgamzahons *:p<O.05' **:P<O.OI Paths in Tenn 2 (n2 = 215) 0.289" (t = 4.098) 。 125 (t=0.879) 0.139 (t=1.184) 。 363** (t=3.876) 。 134 (1 = 0.877) 0.013 。=0.113) 。 146' (1 = 2.322) 。 331** (5.134) 0.214** (1 = 3.563)

Then, we substituted the standardized βvalue derived from SEM into the fol1owing equation for tO (Cohen and Cohen, 1983, pp.55-56), where df = nl +

Chiao Da Management ReviewVol. 30 No. 2. 2010 的, 6um ea MV atr T 佩 r

c

49 Tenn 1 's ßI (nl=

211) Confidence CommitmentSocial Benefits• Commitment 0.149

Benefits → 0.277抖

Special Treatment Benefits • 0.164 Commitment

Confidence Benefits • Trust 0.352**

Social Benefits• Trust 0.152

Special Treatment Benefits • 0.016 Trust

Trust • Commitment 0.141 *

Commitment •Kn owledge 0.316**

Sharing

Trust •Kn owledge Sharing 0.204**

χ2/d. f. of measurement model 2.30 *:p <0.05 ' **:p <O.OI Tenn 2's

m

世三旦旦 0.289** 。 125 。 139 0.363** 。 134 0.013 0.146* 0.331** 0.214** 2.47 ββZ Z(只-~)' +拉克 -1',)~v L主土三至 nl+n2-4 - z xfxz x; to= Test on ß I-ß2 No significant difference (tO = -0.79) N 0 significant difference (的=0.78) No significant difference (的= 1.77) No significant di任erence (的=-0.73) No significant difference (tO = 1.54) No significant difference (的=0.21) No significant difference (tO = -0.81) No significant di能:rence (tO = -0.83) N 0 significant difference (tO = -0.69)No significant differen心e in the whole model (F = 0.931)

Results of the F-tests are shown in Table 6. There is no significant difference in the two samples. The tO test further indicates no significant difference between the pair-wise paths 伊 l-ß2). As a result, we had a good inter-temporal cross-validity, and the resu1t was not a phenomenon of a single period.

50 The lmpacts ofSu,月IyChain Relational Benejìt on lnter-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation of SEM

5. Conclusions

With the emergence of supply chain management philosophy, companies are concerned about internal knowledge sharing as well as knowledge sharing among supply chain members. Based on the principles of the social exchange theory, we studied how supply chain relationship benefits affect inter-organizational knowledge sharing.

The SEM tests reveal that six out of ten hypotheses in this study are supported by empirical data. The empirical results include the following: (1) The higher the confidence benefits of the supply chain relationship benefits, the higher the inter-organizational relationship commitment. (2) The higher the confidence benefits of the supply chain relationship benefits, the higher the inter-organizational trust. (3) The higher trust among supply chain members, the higher the willingness to share knowledge with other organizations. (4) The higher the supply chain relationship commitment, the higher the willingness to share knowledge with other organizations. (5) The higher the trust among supply chain meinbers, the higher the willingness to share knowledge with other orgamzations.

Based on the social exchange theory, we believe that the interaction among supply chain members is also a social relationship. The inter-organizational relationship benefit is an internal variable of social exchange, and knowledge sharing is a social exchange of “knowledge." Our results help the academic in understanding what kind of relationship benefits to focus on and maintain, in order to promote the willingness and actions of knowledge sharing among supply chain members. Such a perspective has long been ignored by the academics.

It is necessary to cross-examine the model in the process of model design. The existence of a relationship between single dimensions does not imply that such a relationship also exists in the entire mode1. As a result, we need further analysis. Even though previous studies seem to have proved the pair-wise relationships, this is the first time a complete model has been studied, domestically or abroad. Therefore the examination is necessary. In addition, since the entire model was not exposed before, in order to avoid shortcomings of a

Chiao Da Managemen/ ReviewVol. 30 No. 2, 2010 51

single dimension, we conducted the inter-temporal cross-validity test to verify that the results are not a special phenomenon in a single period

Empirically, our results help companies access the dimensions of relationship benefits (confidence benefits, social benefits, and special treatment benefits) in knowledge sharing among supply chain members. As a result, supply chain members can create greater relationship comrnitments and trust to e曲ance

the willingness of knowledge sharing among supply chain members. The empirical results show that with respect to knowledge sharing among supply chain members, companies care more about the

“

confidence benefits" than the“

social benefits" and“

special treatment benefits" in the relationship benefits. This sheds light on many companies. In other words, special treatment benefits (such as price discount) do not significantly make supply chain members more willing to share knowledge. The long-term trust relationship remains the most effective means; it significantly increases the willingness to share knowledge with supply chain members.Finally, our subjects of this study were large manufacturing companies in Taiwan. The generalization with other industries or small and medium enterprises requires more future empirical studies. In addition, to increase the explanatory power of models, future researchers can introduce variables based on relevant theories (such as the trading cost theory) to improve the prediction power of inter-organizational willingness to share knowledge.

6.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Council, Taiwan, Republic of China, under the contract number NSC 98-2410-H-265-002.

7.References

Achrol, R. S. (1991),“Evolution of the Marketing Organization: New Forms for Dynamic Environments," Journal

0

/

Marketing, 55(4), 77-93.52 The lmpacts 01 Supp/y Chain Relational Benefit on lnter-organizational

Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation 01 SEM

Aldrich, H. E. (1979), Organizations and Environments, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Anderson, J. C. and Gerbir嗨, D. W. (1988) ,“S仕uctural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach," Psychological

Bulletin, 103(3),411-423.

Anderson, 1. C. and Narus, 1. A. (1990),“A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships," Journal of Marketing, 54(1),

42-58.

Araujo, L. (1998),“Knowing and Learning as Networking," Management

Learning, 29(3), 317-336.

Armstrong, J. S. and Overton, T. S. (1977),“Estimating Non-response Bias in Mail Survey," Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3),396-402.

Asanuma, B. (1989), “Manufacturer-Supplier Relationships in Japan and the Concept of Relation-Specific Ski11," Journal of the Japanese and

lnternational Economies, 3(1), 1-30.

Asheim, B. and Dunford, M. (1997),“Regional Fuωres," Regional Studi缸, 31(5),

445-456.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1978),“Marketing as Exchange," Journal of Marketi嗯, 39(4),

32-39.

Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (1988),“On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models," Journal ofthe Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.

Baranson, J. (1990),“Transnational Strategic Alliances: Why, What, Where and How," Multinational Business, 2(1), 54-61.

Bea旬, S. E., Mayer, M. L., Coleman, 1. E., Reynolds, K. E., and Lee, 1. (1996),

“

Customer-Sales Associate Retail Relationships," Journal of Retailing, 72(3),223-247.

Bell, D. 0., Giordano, R., and Putz, P. (2002),“Inter-Firm Sharing of Process

Knowledge: Exploring Knowledge Markets," Knowledge and Process

Management, 9(1), 12-22.

Bendapudi, N. and Berry, L. L. (1997η),

Relationships wi岫t仕也h Service Prov叫id由er吭s丸," Journal of Ret,ωaωail伽i的ng, 73 (Spring),

Chiao Da Management ReviewVol. 30 No. 2. 2010 53

Bentler, P. M. (仆1990),

Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238-246.

Bentler, P. M. and Bonnett, D. G. (1980),“Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures," Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606.

Blau, P. M. (1964), Exchange and Power in Social L阱, New York, NY: 10hn Wiley and Sons

Bock, Gee Woo and Kim, Young-Gul (2002),“Breaking the Myths of Rewards: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes About Knowledge Sharing," Information Resources Management Journal, 的 (2), 14-21.

Boer, N. L., van Baalen, P. 1., and Kumar, K. (ρ2004) ,

Dif缸fer昀en削lt Models of Social Relations for Understanding Knowledge

Sha訂ring," ln H. Tsoukas and N. Mylonopoulos (Eds.), Organizations as Knowledge Systems: Knowledge, Learning and Dynamic Capabilities,

130-153, NewYork, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brandenburg缸, A. M. and Nalebuff, B. 1. (1996), Co-Opetition. New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, lnc.

Carmines, E. and McIver, 1. (1981), “Analyzing Models with Unobserved Variables: Analysis of Covariance S甘uctures," Social Measurement: Current Issues, CA: Sage.

Chaudhuri, A. and Holbrook, M. B. (2001),“The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role ofBrand Loyalty,"

Journal of Marketing, 的(2), 81-93.

Chin, W. W. and Todd, P. (1995),“On the Use, Usefulness, and Ease of Use of Structural Equation Modeling in MIS Research: A Note of Caution," MIS Quarter秒, 19(2),237-246.

Churchill, G. A. (1979), “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs," Journal of Marketing Research, 16(February),

64-73.

Cohen, J and Cohen, P. (1983), Applied Multiple RegressionlCorrelation Analysis of the Behavior Science (2nd ed.), Hillsdale, New 1ersey, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

54 The lmpacts ofSupply Chain Relational B研究所 onlnter-organizational Knowledge Sharing - Cross Validation of SEM

Cooper, M. C. and Ellram, L. M. (1993),

Management and the Imp抖li此ca訓削ti昀ons for Purchasing and Lo嗯gistics S 仕伽a倒te愕gy,"

I枷胸nt,1t,惚t仿er叫na叫削,t伯叫叫“叫ati肌Oω仰仰naωαalυJou仰Irf仰rnal l?糾f刊仰LμO咖'gl伊仰1臼叫叫'st叫你tii扣的C臼's },胸枷必伽伽n呵1泊呵a嗯'gemη1訓, 4(2), 13-24.

Crone, M. and Roper, S. (2001),“Local Learning from Multinational Plants:

Knowledge Transfers in the Supply Chain," Regional Studies, 35(6),

535-548.

Davenport, T. H. and Prusak, L. (1998), Working Knowledge, Boston: Harvard

Business School Press.

Desouza, K. C. (2003),“Strategic Contributions of Game Rooms to Knowledge

Management: Some Preliminary Insights," Information & Management,

41(1), 63-74.

Ding, L., Velicer, w., and Harlow, L. (1995),“Effect of Estimation Methods, Number of Indicators per Factor and Improper Solutions on Structural

Equation Modeling Fit Indices," Structural Equation Modeli嗯, 2(2),

119-143.

Dixon, N. M. (2000), Common Knowledge: How Companies Thrive By Sharing

What They Know, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Doll, W. 1., X悶, W., and Torkzadeh, G. (1994),“A Confirmatory Factor Analysis

ofthe End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument," MIS Quarter紗, 18(4),

357-369.

Doney, P. M. and Cannon, 1. P. (1997),“An Examination of the Nature of Trust

in Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of Marketi嗯, 61(2), 35-5 1.

Drucker, P. (1998), Managing in a Time of Great Change, New York, NY:

Penguin Putnam.

Dyer, 1. H. (1996),“Specialized Supplier Networks as a Source of Competitive

Advantage: Evidence Form the Auto Indus甘y," Strategic Management

Journal, 17(4),271-292.

Dyer, 1. H. and Chu, W. (2000), “The Determinants of Trust in

Supplier-Automaker Relationships in the U.S., Japan, and Korea," Journal

Chiao Da Managemenl ReνiewVol. 30 No. 2. 2010 55

Dyer, 1. H. and Singh, H. (1998),

Sources of Int紀eror啥gam位za剖甜t“i昀ona訓I Compet昀tJ划tive Ad伽vantage," The Academy of

f

Ma切仰nagementReview, 23(4), 660-679.Emerson, R. M. (1972). Exchange Theory, Part II: Exchange Relations and Networks, pp.58-87 in Sociological Theories in Progress. Vol. 2, edited by J. Berger, M.Zelditch Jr., and B. Anderson, Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin. Emerson, R. M. (1981), Social exchange theory. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Tumer

(Eds.), Social Psychology: Sociological Perspectives (pp. 30-65). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Foray, D. and Lundvall, B. A. (1996),“The Knowledge-Base Economy: From the Economics of Knowledge to the Leaming Economy," In OECD (Eds) Employment and Growth in the Knowledge-Based Economy, OECD Paris,

11-32

Fomell, C. and Larck缸, D. F. (1981),“Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Erro丸" Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Gwinner, K. P., Gremler, D. D., and Binter, M. J. (1998),“Relationship Benefits in Services Industries: The Customer's Perspective," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 101-114.

Hair, 1. F., Black, W.仁, Babin, B. 1., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. L. (2005),

Multivariate data Analysis (6th ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hendriks, P. (1999),“Why Share Knowledge? The Influence of ICT on the Motivation for Knowledge Sharing," Knowledge and Process Management,

6(2), 91-100.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., and Gremler, D. D. (2002), “U nderstanding Relationship Marketing Outcomes," Journal of Service Research,

4(February),230-247.

Holland, C. P. (1995), “Cooperative Supply Chain Management: The Impact of Interorganizational Inforrnation Systems

,

"

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 4(2), 117-133.Homans, G. C. (1958),“Social Behavior as Exchange," The American Journal of Sociology, 的 (6), 597-606.