中國水資源決策過程中科學所扮演的角色: 以湄公河上游水利資源發展為例 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Abstract Yunnan, China is home to the headwaters of the Mekong (Lancang) River, which flows through five countries. China has completed five large dams in a cascade, and is preparing two more. Decision-makers have framed the downstream environmental effects of this cascade based on specific side of the scientific debate surrounding the cascade’s impacts, using one set of scientific research over another. Using Mertha’s additions to the “fragmented authoritarianism” framework for political context, this research uses Kingdon’s policy stream and Haas’s epistemic communities framework to contextualize science in China’s hydropower development. Thoroughly considering the scientific literature, this study finds that decision-makers have not considered the full scope of research, and concludes that primary decision-makers (hydropower companies and government actors) characterized the effects of the cascade as limited and possible to mitigate by excluding actors who emphasized evidence of negative downstream effects from the process. Though these hydropower projects were “recalibrated” to have fewer environmental effects in the early 2000s, and though stakeholders acknowledged negative ecological effects and purported to mitigate and minimize these effects in hydropower development when such development again became a priority for China in this decade, this study finds that decision-makers’ understanding of effects as possible to mitigate is based on scientific research that emphasizes the limits to negative effects, rather than the predicted consequences a number of other studies have found. This has led to the marginalization of negative downstream impact science among decision-makers. Keywords: Upper Mekong, dam cascade, Lancang, Upper Mekong, Kingdon, Haas, policy streams, downstream impacts, science, hydropower, development, Hydrolancang, epistemic communities, multiple streams, decision-making, China, Yunnan. . .

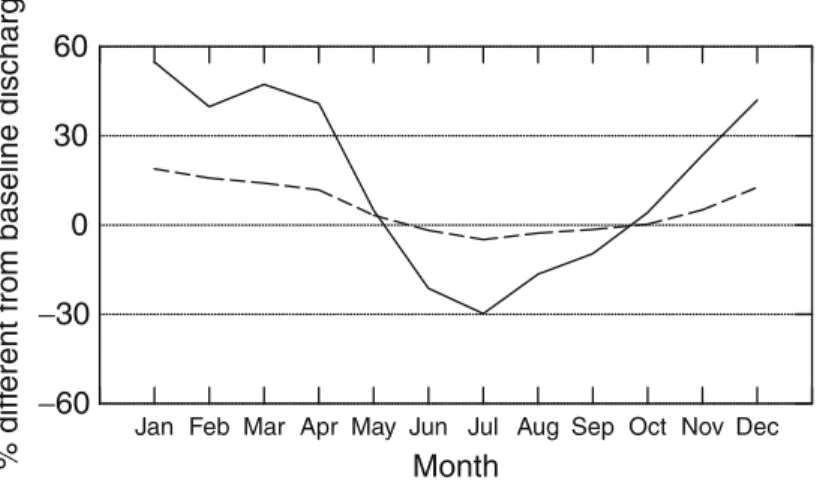

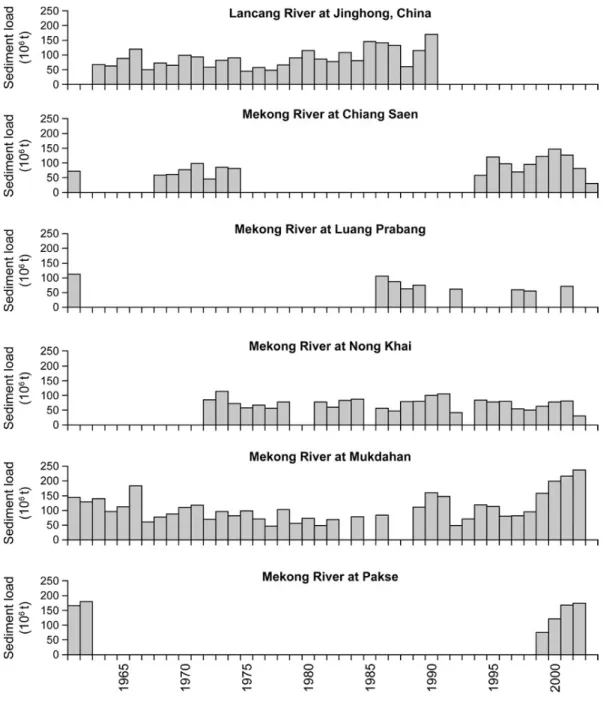

(3) Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables, and Maps .....................................................................................................i Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 2. Research Questions and Hypotheses........................................................................................3 3. Analytical Framework and Literature Review .........................................................................4 3.1 Analytical Framework .......................................................................................................5 3.2 Literature Review.............................................................................................................22 4. Research Methodology ................................................................................................................................30 5. Structure............................................................................................................................................................34 Chapter 2: Accounting for the Difference ..................................................................................36 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................36 2. River Basics – Facts with Relative Consensus.......................................................................38 2.1 General River Basin Information.....................................................................................38 2.1.1 The Mekong Flood Pulse ..........................................................................................38 2.1.2 Primary Drivers of Flow Volume (besides dams) ....................................................40 2.2 Current State of Damming in the Upper Mekong ............................................................42 3. Sources of Dispute: Differing Claims and Findings ..............................................................44 3.1 The Pros and Cons of Development.................................................................................45 3.2 Potential Explanations for Differing Claims ...................................................................48 4. The Hydrology of the Mekong River .....................................................................................49 4.1 Data and Method Differences and Problems...................................................................49 4.2 The Dam Cascade’s Impact on Hydrology ......................................................................50 4.2.1 Findings on the Manwan and Dachaoshan ..............................................................50 4.2.2 Predicted Impacts of the Xiaowan, Nuozhadu, and Full Cascade ..........................52 4.3 Frameworks .....................................................................................................................54 4.3.1 Existing Hydrological Impacts .................................................................................54 4.3.2 Wet to Dry Seasonal Flow Shift ...............................................................................50 5. The Sediment Load of the Mekong River ..............................................................................56 5.1 Data and Methods Differences and Problems .................................................................56 5.1.1 Available Datasets ....................................................................................................56 5.1.2 Uncertainty ...............................................................................................................59 5.1.3 Measuring Frequency, Timescales, and Methodology .............................................61 5.2 Impact Frameworks .........................................................................................................63 5.2.1 Full Cascade Scenarios ............................................................................................66 5.3 Frameworks .....................................................................................................................68 5.3.1 Existing Impacts on Sediment Flow..........................................................................68 5.3.2 Future Impacts on Sediment Flow............................................................................68 6. Ecological Impacts .................................................................................................................69 6.1 Data and Methods Differences and Problems .................................................................69 6.2 Primary Ecological Impacts ............................................................................................70 6.3 Frameworks .....................................................................................................................73 7. Social Impacts ........................................................................................................................74 7.1 Dam Specific Impacts ......................................................................................................75 7.1.1 Manwan & Dachaoshan ...........................................................................................76 7.1.2 Xiaowan & Nuozhadu...............................................................................................77 7.2 Frameworks .....................................................................................................................78 8. Conclusion..............................................................................................................................79. .

(4) Chapter 3: Parallel Policy Streams and Actors’ Use of Science...............................................84 1. Contextualizing Hydropower Development...........................................................................84 1.1 Domestic Energy Needs and the “Send Electricity East” Campaign..............................85 1.2 Regional Disparities and Poverty Alleviation .................................................................89 1.3 Integration with the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) .................................................92 1.4 Climate Change, Scientific Development, and Low-Carbon Development .....................87 2. Contextualizing Hydropower Development...........................................................................96 2.1 Electric Power Industry – Huaneng and Hydrolancang .................................................96 2.1.1 Industry Reforms and the Relationship with the Government ..................................96 2.1.2 Huaneng and Hydrolancang’s Impact Science Stance...........................................100 2.2 The Ministry of Water Resources (MWR) ......................................................................104 2.2.1 MWR’s Role in the Decision-Making Process .......................................................104 2.2.2 The MWR’s Stance on Impact Science ...................................................................108 2.3 The National and Yunnan Development and Reform Commission................................110 2.3.1 The NDRC and YDRC’s Role in the Decision-Making Process.............................110 2.3.2 The NDRC & YDRC’s Stance on Impact Science ..................................................111 2.4 The Yunnan Provincial Government..............................................................................112 2.4.1 Local Government Incentives for Hydropower ......................................................112 2.4.2 Yunnan Provincial Government Stance on Impact Science ...................................112 2.5 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs .....................................................................................113 2.6 The Ministry of Environmental Protection ....................................................................115 2.6.1 The MEP’s Role in the Decision-Making Process .................................................115 2.6.2 The MEP’s Stance on Impact Science ....................................................................116 2.7 Non-Governmental Organizations and Epistemic Communities ...................................116 2.7.1 Asian International Rivers Center ..........................................................................116 2.7.2 Green Watershed ....................................................................................................118 2.7.3 International Rivers Network .................................................................................119 3. Conclusion............................................................................................................................119 3.1 What counts as water science and who decides what water science is? ...................120 3.2 Who decides how much water science counts in decision-making?..........................125 Chapter 4: The Impact-Science Policy Stream ........................................................................127 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................127 2. The Problem and Politics Stream .........................................................................................127 2.1 The Road to Corporatization – 1985 to 2002 ................................................................128 2.2 The “Recalibration” Period – The Early- to Late-2000s ..............................................130 2.3 The Timing of the Upper Mekong Cascade ...................................................................138 2.4 The Re-prioritization of Hydropower – 2008 to present ...............................................141 3. The Policy Stream ................................................................................................................143 4. The Problem of Perspective .................................................................................................145 5. The Marginalization of the Negative Impact Science Policy Stream ..................................151 5.1 Negative Impact Science versus Mitigated Impacts.......................................................151 5.2 Wider Domestic Context and Focusing Events..............................................................153 6. Conclusion............................................................................................................................158 Chapter 5: Conclusion................................................................................................................159 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................159 2. The Cascade’s Impacts Going into the Future .....................................................................159 3. Summary of Findings ...........................................................................................................162 4. Implications and Scholarly Contributions............................................................................168 5. Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Further Research..........................................172. .

(5) Works cited.......................................................................................................................... 175-193. .

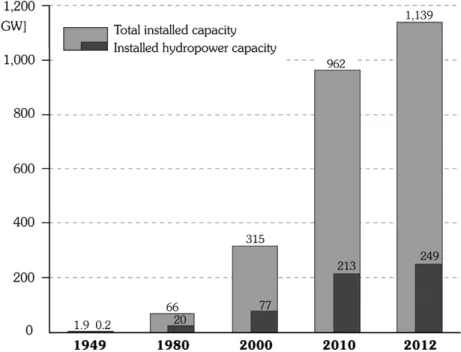

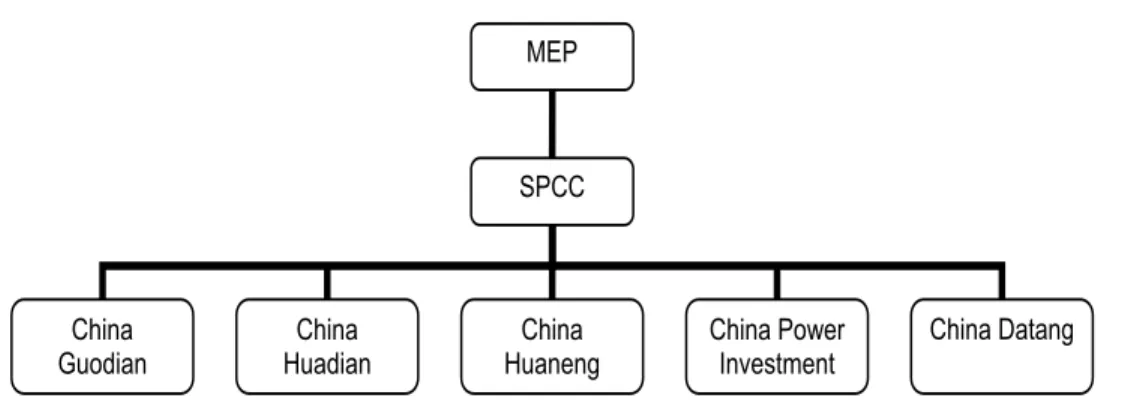

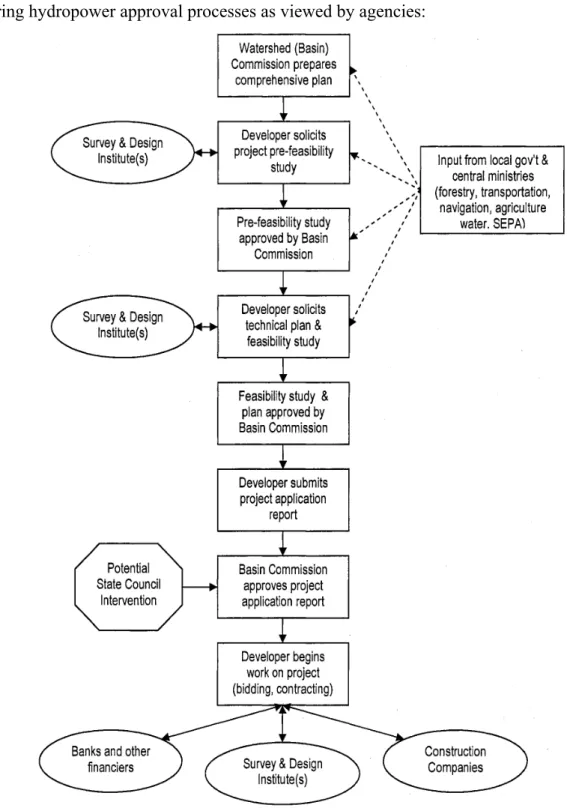

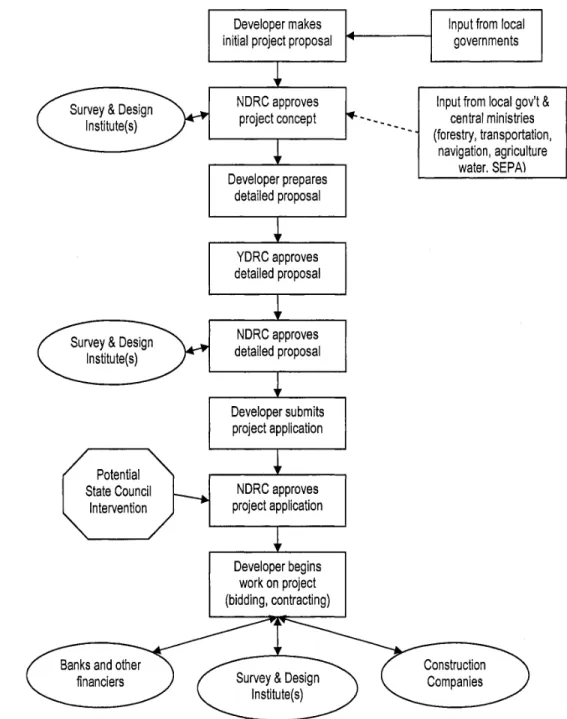

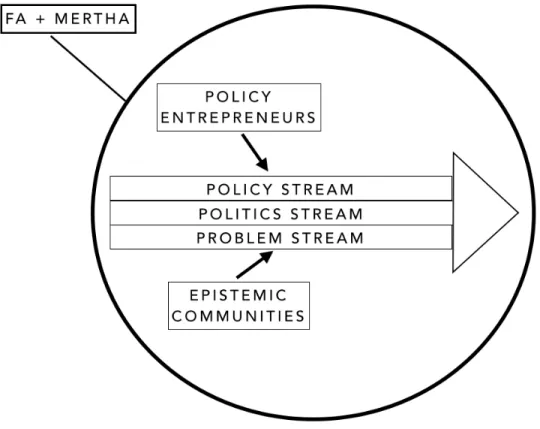

(6) List of Figures FIGURE 1: ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................................21 FIGURE 2: BASELINE DISCHARGE AT CHIANG SAEN WITH XIAOWAN AND NUOZHADU ...........54 FIGURE 3: THE AVAILABILITY OF ANNUAL SEDIMENT LOAD ESTIMATES ..................................61 FIGURE 4: A COMPARISION OF TSS VS. SSC DATA AT CHIANG SAEN, THAILAND ...................63 FIGURE 5: AQUATIC BIODIVERSITY AND NATURAL FLOW REGIMES .........................................70 FIGURE 6: GROWTH OF CHINA’S INSTRALLED HYDROPOWER CAPACITY ..................................85 FIGURE 7: ELECTRIC POWER RESTRUCTURING (1998-2002).....................................................97 FIGURE 8: THE CWRC’S PERSPECTIVE ON THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS..........................106 FIGURE 9: HYDROPOWER COMPANIES’ PERSPECTIVE ON THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS ...107 FIGURE 10: SHIFT IN POLICY STREAM FRAMEWORKS ..............................................................121 FIGURE 11: TIMELINE OF MAJOR EVENTS & TIME PERIODS ON UPPER MEKONG ............ 144-145 FIGURE 12: NET MAGNITUDE AND SALIENCE OF DAM IMPACTS ..............................................148 FIGURE 13: MULTIPLE STREAMS FRAMEWORK WITH OPPORTUNITY WINDOWS ......................157 FIGURE 14: CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE LITERATURE ...................................................................171. List of Charts CHART 1: AVAILABLE DATASETS ON MEKONG’S SEDIMENT LOAD .................................... 56-57 CHART 2: SUMMARY OF SCIENTIFIC CONSENSUSES ............................................................. 80-81 CHART 3: TIMELINE OF THE DOWNSTREAM IMPACT SCIENCE STREAM ........................... 139-140. List of Maps MAP 1: MAP OF THE UPPER MEKONG DAM DASCADE ..............................................................44 MAP 2: UPPER AND LOWER MEKONG MEASURING STATIONS ..................................................58 MAP 3: NATIONWIDE WEST TO EAST ELECTRICITY TRANSFER ................................................88. .

(7) Chapter 1: Introduction 1. Introduction The past three decades in China has seen unprecedented development, bringing with it major advances in the average welfare of a vast number of Chinese citizens. Development priorities have been primarily directed at poverty alleviation, as seen with a number of policy campaigns. These advancements have brought with them vast increases in energy demand, as well as environmental degradation so severe that some highranking government officials have warned that the situation has reached critical proportions and threatens the future economic performance of China (Whittington, 2004). Decision-makers have long viewed hydropower as a key solution to both the continued benefits from development and as a means to decrease environmental impacts. In the past five to ten years the Chinese government has passed aggressive laws and regulations catalyzing massive investments into clean energy technologies with ambitious renewable energy targets. These green energy goals lessen pollution (depending on the method) and decrease pressures on national water needs. Despite an acknowledgement of its severe environmental impacts and energy intensity, China’s government has committed to double the size of the economy again within 10 years, and urbanize 350 million people over the next twenty (Schneider et al., 2011). In more recent years, low-carbon development has come to the forefront of development discourse. While considered key to a number of development projects, hydropower has arisen as one of the primary drivers of continued, and clean, development for China. Inevitably these and past development goals along with a desire and need for domestic energy production has led to the exploitation of the abundant water resources of western and southern China. Rising domestic demand has led to the commitment to develop western China – Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Qinghai and Gansu; the autonomous regions of Tibet, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi and Xinjiang; the municipality of Chongqing – under the “Develop the West” policy (西部大開發) (Dore 2004). Forming a component of the 10th Five Year Plan, the Western Development Strategy 2000-2020 aims to make the. . 1 .

(8) western region into a significant energy supplier. With approximately 24% of China’s medium to large hydropower potential (Dore 2004), and its relatively large economic gap between itself and more wealthy eastern provinces, Yunnan offers a unique insight into the development and implications of China’s domestic hydropower development. Additionally, Yunnan, and nearby Tibet, are the home to the headwaters of many important transnational river basins in the region. Specifically, the Lancang/Mekong river flows for 800km in Tibet before entering Yunnan where it flows for another 1,247km. Downstream the Lancang/Mekong (called the Lancang river in China, and the Mekong river in southeast Asia) river flows through the other riparian states of Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, thus making any upstream development of the river an interest to the entire multi-national river basin. Currently China has built five major dams on the river (Manwan, Dachaoshan, Xiaowan, Jinghong, and Nuozhadu), with more planned. China views the development of its portions of the Lancang/Mekong river as a domestic affair, and as such began construction of the dams unilaterally and without notification of its downstream neighbors in 1989. Despite increased communication, assurances, information exchange, and so on, the situation remains largely the same. Multiple perspectives and knowledge sets surrounding the costs and benefits of the development of the Lancang/Mekong river exist throughout the region. The Chinese government frames the dams as a means develop Yunnan, increase clean electrical output, increase navigability of the rivers, to control flooding during the wet season, and to provide more water during the dry. While the proponents of the dams in the Chinese government seem relatively certain of the benefits of the project outweighing the negatives, there remain a large number of groups both within and outside of China – downstream governments, some domestic government agencies, NGOs, scientists, and communities – that remain dubious of benefits of development. These groups cite scientific findings showing potential severe impacts to ecosystems and economies heavily reliant on the health of the river. The use of downstream impact science by decision-makers is pivotal to their understanding of hydropower development. China’s central government has fully endorsed hydropower as the centerpiece of continued development. While acknowledging some potential negative impacts, decision-makers surrounding. . 2 .

(9) hydropower development have come to the conclusion that the cascade will not only have limited impacts, but also that the advantages simply far outweigh the disadvantages. As such, an investigation into what science says about downstream impacts compared to what science is used to frame downstream impacts may offer an important insight into the perspectives of decision-makers on hydropower in China. This study takes up the case of the Upper Mekong river dam cascade (referred to as the Lancang river in China) to do just that. 2. Research questions and hypotheses The objective of this research is to determine what downstream impact science is factored into the framework surrounding hydropower development on the Upper Mekong by Chinese decision-makers, and to how much it plays a role in both development decisions and understanding of large-scale dam impacts. My hope is that by examining the constellation of actors around hydropower development of the Upper Mekong in China – government agencies, hydropower companies, NGOs, communities, and individuals – as well as the scientific evidence jaon downstream impacts they use (or don’t use), and relevant policy changes, the research may shed some light on the role of science in China’s domestic hydropower development. This may also bring about an understanding of variations in perceptions of the cascade’s consequences, and their sources. As such, this research intends to address the following questions: what scientific conclusions have been made regarding the downstream impacts of the Upper Mekong dam cascade? Are there any divergent conclusions? To what degree is science counted in development, management, and policy decisions? What science do decision-makers use (or don’t use)? Who decides how much it counts in the decision-making process? And finally, what are the potential consequences of various interpretations of the scientific evidence. I hypothesize that over time, a number of policy streams and consequent opportunity windows within the Chinese political system have arisen to address the related or parallel issues of development, energy demand, and climate change, which have in turn at different times both intentionally and inadvertently marginalized the negative impact. . 3 .

(10) science of the Upper Mekong (Lancang) cascade and their related epistemic communities and policy entrepreneurs. This marginalization of the costs of the Lancang cascade likely reduced the ability of actors to contribute to the problem stream, which in turn will shift the time at when these issues are dealt with into the coming decade. Should the research find evidence for the above mentioned hypothesis, it would seem likely that either a rise in the prominence of related epistemic communities and/or their findings or discourse within government framings of the cascade OR a series of focusing events, will likely be indicators of a shift towards the de-marginalization of negative impacts science of the Upper Mekong cascade. 3. Analytical framework and literature review 3.1 Analytical framework Throughout the reviewed literature, it seems that relatively little of it attempts to assess the role of impact science in relation to the decision-making surrounding the Lancang cascade development. As described by Magee (2005), the “existence of scientific research does not ensure that the results will have any bearing on hydropower development, planning, or implementation…”. That said, however, the increasing number of third-party groups (e.g. academic institutions and social organizations) and government watchdogs (e.g. the Ministry of Environmental Protection) attempting to influence hydropower decision making in China (see Magee 2005, 2006, 2011; Mertha 2008) suggests that the role of science is, at the very least, to legitimize, delegitimize, critique, support, or contextualize development. Darrin Magee (2005, 2006a, 2006b, 2011) has touched upon the role of science in hydropower development in China, primarily through an examination of the hydropower development on the Nu and Upper Mekong (Lancang) rivers in Yunnan and the lens of development priorities within China. In Magee (2005), he contends that in debates over development of major rivers, typically socioeconomic and political concerns often weigh more heavily than that of the traditional “hard” water sciences of hydrology, morphology, aquatic biology, and so on. Magee goes on to argue that both the “hard” sciences. . 4 .

(11) mentioned above as well as social science should both be examined together in comprehensive, interdisciplinary, cooperative studies. Magee (2006a, b), examined the role of energy companies in hydropower project implementation and motivation. While expounding on the complexity of the decision-making apparatus, Magee found that the energy needs of southeast Asia and China (e.g. Guangzhou) coupled with the competition between the Huaneng and Huadian power companies to get approval for mega-projects in an atmosphere of state and quasi-state actors, creates a general push for hydropower development. In addition, Magee (2006a,b) uses geographical scale as analytical device, exploring the notion of the politics of scale justifying Yunnan’s part of the “the west” in China used to justify both regional integration and justifying government policies and needs. “Just as studying erosion in the Mekong delta requires attention to hydrologic and socioeconomic processes throughout the entire Lancang-Mekong watershed, so does understanding economic development in Guangdong necessitate consideration of one of the primary driving forces behind that development, namely electric provision” (Magee 2006b, 41). Magee (2011) also examines the role of other motivating forces behind dam development – domestic energy needs, regional integration, poverty alleviation, low-carbon development, etc. – and China’s interaction with the region. However, it only briefly touches upon the use of science within hydropower development. All of Magee’s abovementioned studies offer significant insight into the frameworks surrounding hydropower development in the Upper Mekong, and are essential to understanding the context within which downstream impact science exists. This will be explored more indepth in chapter 3. Brown et al (2009), Tullos 2009, and Tullos et al (2010) all examine perception of impacts from large-scale dam construction among stakeholders. Brown et al (2009) and Tullos et al (2010) found that among government and hydropower industry representatives (specifically in Yunnan in Tullos et al’s study), large-scale dam benefits were seen to outweigh the impacts of downstream impacts while also perceiving impacts. . 5 .

(12) as of lesser magnitude. This is opposed to academics and NGO representatives who decidedly viewed large-scale impacts as negative, with the negatives outweighing the positives, and viewing impacts as having greater influence than others. Tullos (2009) examined the use of environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and its success (or lackthereof) of mitigating negative impacts of large projects like the Three Gorges dam. The uncertainty of impacts in scientific assessments can greatly impact mititgation measures and the extent to which the EIA is included in the development and management process. Generally uncertainty is riven by different time and spatial scales, a failure to consider interdisciplinary links (Brown et al 2009), and the cumulative impacts of dams, espcially if they’re in a cascade (Tullos 2009). Of the literature reviewed, I found very little English-language research, outside the abovementioned work, touching upon the use and role of science in the development of the Upper Mekong. More specifically, while the perception of impacts through an examination of scientifically backed downstream impacts was examined in Brown et al (2009) and Tullos et al (2010), I did not find any literature examining the specific scientific evidence that government and hydropower representatives were using when describing downstream impacts, nor the potential reasons for its use. This research seeks to contribute to the limited English-language literature on the role of science in decisionmaking on China’s development of the Upper Mekong, and bridge the perceived gap between the literature addressing downstream dam impacts (typically scientific papers), the use of science in decision-making, and potentially competing scientific frameworks that are available to decision-makers in China. To address this, Kingdon’s “multiple streams” (MS) framework will provide an overarching analytical framework for the information gathered in this research, with important contributions to the framework from the concepts of Haas’ “epistemic communities” and Mertha’s contribution to the wellknown “fragmented authoritarianism” framework. Kingdon’s MS model seeks to explain why certain policies are ultimately adopted or fail. The framework identifies two sets of factors – participants and processes – that impact agenda setting and alternative specifications to a given issue under governmental consideration. Participant factors consider actors inside or outside the government, their level of visibility, and their influence. Influence of participants is dependent upon. . 6 .

(13) whether they’re “visible”, i.e. those who receive a lot of press and public attention, which tend to have more control on setting the agenda and less control over alternatives. “Hidden” participants (e.g. interest groups, researchers, civil servants, epistemic communities, etc.), on the other hand, are more effective in specifying alternatives. Kingdon also raised the concept of “policy entrepreneurs”, also used under Mertha’s model (discussed below). Policy entrepreneurs are advocates for policy proposals or the prominence of an idea. John Kingdon describes them as follows: "These entrepreneurs …could be in and out of government, in elected or appointed positions, in interest groups or research organizations. But their defying characteristic…is their willingness to invest their resources - time, energy, reputation, and sometimes money - in the hope of a future return…[including] in the form of policies of which they approve." (Kingdon 2002, 122) These policy entrepreneurs often bide their time until chance opportunities arise, indicating they may not simply be providing a solution in response to an issue but rather have already formulated a solution and have been waiting for a particularly salient issue to arise (Kingdon 2002; Mertha 2008). This framework was originally conceived to address the United State’s federal system, and the two most important actors affecting agenda setting were also the most visible: the administration and Congress. This raises the concern of adapting an analytical framework from its original democratic context to the authoritarian regime in China. Kingdon’s multiple streams framework originally sought to understand the changes in policies in the US congress from the efforts of policy entrepreneurs. In a democratic context, these actors are decidedly derived heavily from both governmental and non-governmental actors, with non-governmental forces having much more say in the policy process than in an authoritarian regime. In China, however, civil society and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) work more in a supplementary role, than a typically adversarial role in western nations. The key adaptation to the multiple streams framework for authoritarian regimes, as this research intends to show, is to better understand those entities with which decision-makers in China consult with. Therefore, while in recent. . 7 .

(14) times civil society has become much more ingrained in the policy process in China, in an authoritarian regime their role remains relative to the support of bureaucratic bodies within China’s government, and increasingly public opinion (if only to a certain extent). As such, within an authoritarian regime the use and understanding of science seems more dependent on those bodies with which the government consults, in this research described as epistemic communities. Kingdon’s framework differs in the context in China with the use of focusing events. Hydropower has been an accepted, dominant framework within China as a means of continued developed. As such, many of the driving policy streams behind hydropower development on the Upper Mekong have not faced many opportunity windows that changed the course of viewing hydropower as a key development tool. Rather, it seems that many of the events have not shifted the course of streams pushing for hydropower development, but have only further solidified hydropower’s position in the government’s framework surrounding continued development. This will be discussed more in-depth in chapters three and four. In addition, in Kingdon’s MS model, policy entrepreneurs typically follow two basic principles when proposing a new policy idea. Their ideas are selected only when they are “technically feasible” and “value acceptable” (Zhu 2008). “Technically feasible” means that actors supporting a proposal must delve into details and technicalities, and gradually eliminate inconsistencies and specify mechanisms (Kingdon 1995; Zhu 2008). “Value acceptable” means that the proposal is both acceptable to the policy entrepreneur themselves, and the intended target (Zhu 2008). These two concepts, however, are admittedly ambiguous and difficult to determine. “Technical feasibility” is “a multidimensional notion consisting of legal, administrative, financial and technological feasibilities, among others” (Zhu 2008, 317), which remains difficult to prove by the sheer number of factors needing to be tested. “Value acceptability” could consist of political views, ideology, political or national culture, and so on, the characteristics of which are not elaborated upon in Kingdon’s work. In the context of an authoritarian Chinese government, policy entrepreneurs must function very differently to their Western counterparts. First, the doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the most important and dominant element in China’s political system. Singular party rule equates to no technical distribution of power among the highest state agencies as there would be. . 8 .

(15) in say the United States. Rather, leaders from the government, legislative, and other consultative agencies discuss and decided upon courses of action for various future policy endeavors, while also sometimes making direct policies to guide governmental affairs. As such, the decisions of the CCP affect the entire bureaucracy and the decision-making systems within it. This singular party means that regular periodical transfer of political power does not occur as in would in Western politics. Rather, change over occurs in shifts in senior leadership positions like in the State Council, thus making the “politics stream” (discussed below) relatively stable (Zhu 2008). Second, under the cadre personnel system, government representatives, both in the party and government, are selected and appointed by their supervisors and predecessors (Lieberthal 1995; Zhu 2008). Therefore, government officials are often relatively insulated from policy actors outside the government; they typically not held accountable to social policy actors or the public, but rather their superiors within the government (Zhu 2008). As this research will show, the trusted actors within the government and the trusted groups with which the government consults with under situations of uncertainty are vital to their understanding of given policy decisions. In addition, it is not necessarily problematic if officials fail to initiate policy changes and analysis when ordinary problems occur, even if these situations open a “policy window” (Zhu 2008). However, officials are more likely to pay attention in to problems or change their perspective if in a given case they must deal with powerful or persuasive external forces powerful enough to call into question officials’ positions (i.e. higher level officials or bodies in the government hierarchy, an increasingly commercialized media, etc.) (Zhu 2008). This is an important factor, as policy entrepreneurs and officials are notably averse to taking any amount of risk lest they bring about reprisal from higher officials. As such, actors and bureaucracies rarely take on the role of a “policy entrepreneur” as Kingdon defines it in China. Rather, these groups arise either in times of certainty of legal backing and institutional mandates, like with SEPA in mid-2000s (discussed in chapter three and four), or in NGOs and other actors outside the government itself. Zhu (2008) argues that for policy entrepreneurs outside the government employ a “technical infeasibility model” which contends that “third sector” policy entrepreneurs promote change by making politically acceptable, but technically infeasible policy proposals for change. By doing. . 9 .

(16) this, these actors may shift the conversation and spur a change from decision-makers that can be done given what is technically feasible. In Kingdon’s MS model, technical feasibility is a requirement for the success of a given policy entrepreneur’s efforts. In China, technical feasibility is no necessarily required. “…in China today the policy entrepreneurs’ “technically infeasible strategy” serves to maximize the likelihood that the policy proposal will gain leadership attention, through the attention of media and public – where a “technically feasible strategy” may leave the entrepreneurs’ proposal lost in the lacunae of bureaucracy” (Zhu 2008, 331). As touched upon above, participants in the MS framework interact under the context of the three process factors, consisting of the streams themselves: the problem stream, policy stream, and politics stream. The problem stream examines how and why certain problems gain attention from the government. Actors compete to define problems within this stream according to their goals, values, and information (Stone 2002; Turin 2012). Systemic indicators such as “focusing events” (e.g. disasters or crises) and feedback contribute to shaping how problems are framed and brought to the attention of the government (Kingdon 2002). The policies stream, consists of various alternative policy solutions, proposals, strategies, and initiatives to a given problem, which must meet a “criteria for survival” within the “primeval soup” of policy discourse (Kingdon 2002; Zhu 2008). These criteria – technical feasibility, value acceptability, applicability to a prominent political campaigns, and anticipation of future constraints, among others – determine its likelihood for diffusing among decision makers. The result is what Kingdon describes as a “short list” of ideas upon which general consensus is founded (Turin 2012). The politics stream consists of macro-political conditions, elements that create an environment either conducive or hostile to certain types of ideas: a change over in the State Council, a prominent new political campaign, interest group pressure, energy demand, local resistance, and so on. It is within this steam that visible actors (e.g. the central and provincial government, the NDRC, etc.) may have strong impacts over policy agendas, while “organized forces” (e.g. interest groups, hydropower companies, etc.) maintain important influences over the alternatives considered.. . 10 .

(17) Kingdon theorized that major changes in policy are possible after a convergence of all three streams to create a “policy window” or “window of opportunity”. Policy windows “exist when some consensus has been reached that government should address a certain problem, a suitable alternative is available and matched with the problem, and the political climate is conducive to change” (Turin 2012). Meaning that policy entrepreneurs and related actors then have the opportunity to get a solution, pet policy, or get attention for an issue into the mainstream decision-making network. According to Kingdon, typically these policy entrepreneurs facilitate large policy changes by taking advantage of policy windows. Policy entrepreneurs prioritize the solution or issue based on its likelihood to gain traction (Kingdon 2002). Typically these openings occur during a change in the political stream (e.g. a change over in the State Council, a prominent new political campaign, etc.) or a new problem captures the attention of government officials. These opportunities “close” when the problems are deemed “solved”, acted upon, or a new issue arises (Kingdon 2002). While both “problem” and “policy” streams often already exist on the governmental agenda, a convergence all three streams offers a better guarantee of a given issue to exist within the “decision agenda” of a government (Kingdon 2002). This, in turn, allows for and creates policy changes on a given issue or existing policy. Under Kingdon’s framework, these streams typically exist separately from one another, needing to come together under certain situations to create a “policy window”. Within the context of China, however, a number of scholars have found that they are, in fact, very much intertwined (Bi 2007; Zhu 2008). As is also found in this research, Bi (2007) and Zhu (2008) found that the problem stream and politics streams build off one another as the factors conducive to or hostile to new ideas are directly involved with the its relation to the CCP, the stability of the government, and prominent initiatives within the government. Therefore, the problem stream – how and why problems are deemed relevant – is tied directly to the politics stream, as they exist in reference to decisionmakers positions. The policy stream then follows from what is both feasible and acceptable among decision-makers and officials generally unwilling to engage in risky policy changes. As mentioned above, due to the structure of the government, decisionmakers are also generally isolated from differing policy streams because of their. . 11 .

(18) answering to superiors within the government rather than outside actors (Bi 2007; Zhu 2008). As such, as this research will argue, those trusted groups with which they consult with on policy streams with certain levels of uncertainty (i.e. downstream impact science) could potentially have major impacts on how the policy stream changes. To summarize, I believe the Kingdon MS framework can effectively be adapted to the authoritarian China context through an understanding that the three streams are very much intertwined. In addition, given the bureaucratic structure of China’s government restricting the courses of actions of policy entrepreneurs both within and outside the government, their relationships with policy change dynamics are significantly different than their Western counterparts, as described above. However, given these modifications, the MS framework seems to offer good insight into both policy change and their related actors within China. The next step is to establish the broader political system within which these policy streams exist. To do this, this study uses Lieberthal and Oskenberg’s fragmented authoritarianism (FA) framework with Mertha’s (2008) additions as a basic construct of understanding of China’s governmental system. Briefly, the FA framework describes Chinese politics as a system in which the policies made at the center become increasingly malleable to the parochial organizational and political goals of various agencies and regions charged with enforcing the policy. Therefore the policy outcomes of a given policy are the result of the incorporation of the interests of the implementation agencies into the policy itself. The model originally illustrated the segmentation of authority among the functions of administrative organs in order to explain economic policy change, exploring the fundamental change to China’s bureaucracy brought from economic decentralization. As such, the negotiations among bureaucratic organs factored significantly in policy-making. Lieberthal and Oksenberg’s FA model asserts that authorities are divided into a number of “clusters” based on policy interests and bureaucratic mandates. Therefore, the achievement and/or retention of their policy interests through consensus seeking becomes the core rationale in decision-making in China (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988). The governmental organs are organized by “vertical” lines (條, tiao) and “horizontal” lines (塊, kuai) of hierarchy. Vertical lines gather bureaucratic organs along. . 12 .

(19) with similar functions and jobs; horizontal lines refer to bureaus at the same hierarchical level, but with different functions in a sort of non-binding professional relationship (Lieberthal 1995). Economic reform and decentralization stressed the “kuai” hierarchy, thus making decisions be achieved through “an enormous amount of discussion and bargaining among officials to bring the right people on board” (Lieberthal 1995, 173). As such, FA would provide opportunities for actors to halt or delay important policies from adoption to enforcement. This is an important dynamic in the early- to mid-2000s during which a “recalibration” of development policies occurred in part because of the competition among one bureaucratic “tiao”, the National Reform and Development Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Water Resources (MWR), and hydropower companies and another tiao, the then State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), along with a shift in the tone of development framing under the then Wen Jiabao-lead State Council (discussed in chapter three and four). While in the FA model bureaucratic unit and localities are important actors through a process requiring consensus among clusters of ministries, the central government remains a critical actor (Lieberthal 1995). Their role, as Lieberthal (1995) put it, is to resolve disagreements within lengthy negotiations and discussions. In addition: “Policy is the aggregate response of leaders or factions of problems they perceive and this response reflect the relative power of the participants, their strategies for advancing their beliefs and political interests, and their differentiated understanding of the problem at hand” (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988, 15). The central leadership is also capable of framing normative principles of policies, with which ideologies and slogans are used to facilitate the transfer of policy visions to the lower level and enhance their coordination ability (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988, 171172) (e.g. scientific development). Economic reforms, however, resulted in the declining utilization of ideologies and the center’s providing normative motivations. This leaves much to lower level government bodies, and in this research, much to the discretion of the NDRC, Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), and the hydropower companies themselves (after 2002 reforms, discussed in chapter 3). Its role, rather, falls to directing. . 13 .

(20) the general blueprint and dimensions of development, and as will be discussed in chapter 3 and 4. As such, the FA framework itself offers a good understanding of the influence of the role of the central government in a reforming China, and the lower level bureaucratic competition for dominant frameworks, especially after laws and bureaucratic mandates began to shift after the Water Law of 2002, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Law of 2003, and the corporatization of the electricity companies in 2002. What is needed next is a more complete picture of the interaction between the abovementioned actors within the government itself, and those they interact with outside the government. Mertha (2008) expands on the FA framework to modernize the theory originally crafted to describe China of 1988, by portraying a triangular relationship between central leadership, provincial bureaucratic units, and civil society. China’s government monopoly on information has since relaxed since the ongoing reforms of the economic system starting with Deng Xiaoping, allowing for the competing frameworks and interests in relation to a policy to move beyond the sole purview of government agencies to other non-state entities. Mertha expands FA by taking the strands of policy entrepreneurs, issue framing, and coalitions of broad based support from American public policy literature in order to reexamine the FA framework in modern China. Mertha concept of policy entrepreneurs derives in part from Kingdon’s framework, as described above. The key is for these actors to engage the political process from spaces from which they may articulate and amplify issues rather than existing outside of it. In Mertha’s analysis, three types of policy entrepreneurs figure prominently. The first are officials within Chinese government agencies opposed to a given policy, often because of their official mandates. For example, the NDRC and MEP (formally State Environmental Protection Agency, SEPA) have historically butted heads when development projects conflict with environmental protection. The second, the media, has grown in an increasingly liberal media environment. Encouraged in part by Chinese media progressively more required to generate its own budgetary revenue, tabloid journalism has been on the rise, leading journalists to cover government injustice, civil protest, and other sensational issues. Finally, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have expanded in number and power in China, depending on the situation and political affiliation (Mertha 2008; Fewsmith 2008). Indeed, what the original FA framework was. . 14 .

(21) missing in the modern context was the inclusion of individual activists, intellectuals, and NGOs so as to adapt to the rapid changes in the political and social environment in China, especially in relation to hydropower. Mertha argues that the weaknesses of bureaucratic units in response to rapid social changes, especially in an environment in which interest groups and citizens more actively fight for their interests. NGOs themselves, unlike their western counterparts, largely work as a supplementary (as opposed to hostile) to government authorities to address these shortcomings. Policy entrepreneurs use issue framing to shape the contours of political discourse around a given topic in order to mobilize allies toward the goals of policy change. This would be observed within the both the problem and policy stream, as these policy entrepreneurs compete in both via issue framing. Their success in China has been in part because of the rise of alternative media frames while the potency of “state framing” has declined. The success of these frames depends on the actor’s ability to strategically employ elements of an issue that will resonant with the most number of potential recruits to the cause. Frames have to appear natural, logical, and recognizable (Mertha 2008). They must be “culturally compatible”, internally consistent with the movement’s beliefs and goals, and relevant to the intended target (Mertha 2008). Within Kingdon’s framework, this “culturally compatible” idea falls within the “politics stream”, as windows only occur under the right conditions, including the political culture of the time. In authoritarian China, these factors must also coincide with an understanding that policy change is not a sharp deviation from the status quo. Rather incremental policy change is the key to framing success within China (Mertha 2008). Finally, policy entrepreneurs are extremely dependent on either their connections or ability to build coalitions and broad-based support. Within the Chinese context “coalitions”, politically speaking, are a highly charged term within China. But these interest groups are most certainly coalitions in that they “share a set of normative and causal beliefs” and “engage in a nontrivial degree of coordinated activity over time” (Mertha 2008). Any issue picked up on a national level or beyond raises the potential for large portions of the population, while not actively engaged in the policy making process, to demonstrate their views through forms of expression ranging from discontent online to protests (Economist 2005). Another important aspect of coalitions within China revolves. . 15 .

(22) around the role of political cover. Government officials hide behind the functional responsibilities of their office; others have political connections that insulate them against political sanctions. For example, SEPA’s Pan Yue is the son-in-law of Liu Huaqing, former head of the Chinese navy, Politburo Standing Committee member, and member of the Central Military Commission. Founder of the NGO Green Earth Volunteers, and activist Liang Congjie is the grandson of late Qing dynasty reformer and intellectual Liang Sicheng (Mertha 2008). These, among other factors, contribute to their relative protection. The fragmented political system of China provides policy entrepreneurs and coalitions of participants with the spaces they need in order to exist without being pushed out by the state. Chinese hydropower politics offers a rare glimpse into the pluralization of Chinese politics, as very real and substantive participation by actors hitherto forbidden to enter the policymaking process are increasingly able to do so. This is because they do not threaten, or are not perceived to threaten the legitimacy of the CCP. This research will attempt to identify the actors surrounding the Lancang dam cascade, and their frameworks. Indeed, it offers a good explanatory framework for both the actors involved and the state of the policy streams over time, as the increased room for actors outside the government to have a voice in the decision making (or at least alternative specifications) derives from the on-going process of “cracks” in authority and discourse continue their process of opening. The most significant of these “cracks” being the energy sector reforms that eventually lead to the five main energy companies in China today, discussed more in chapter 3. An important missing piece to the puzzle of hydropower development – one seemingly lacking as an analytical tool within the literature – is the examination of what Haas’ describes as “epistemic communities” (ECs). ECs are: “…a network of professional with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area” (Haas 1992, 3). What distinguishes ECs from policy entrepreneurs is a common set of beliefs based upon causal knowledge applied to policy enterprises subject to their normative objectives. These objectives derive from a set of beliefs that they share about a given subject based on the scientific method and/or practiced expertise. First, they hold a set of. . 16 .

(23) normative and principled beliefs (value-based rationale for social action). Second, they hold common causal beliefs derived from analysis of practices or contribution to a central problem, elucidating multiple linkages between possible policy actions and outcomes. Third, ECs hold common notions of validity, with inter-subjective and internally defined criteria for weighing and validating knowledge within a domain of expertise. This typically derives from the fourth commonality, a common policy enterprise via the common practices associated with which their professional competence is directed, “presumably out of the conviction that human welfare will be enhance as a consequence (Haas 1992). These commonalities as a community set them apart from policy entrepreneurs as they do not necessarily actively seek a winning framework within policy circles, but rather offer a steady framework on a given topic based on thorough practice and internal devices that check and refine knowledge. In addition, unlike policy entrepreneurs, ECs do not typically lobby for their interests, although they may advocate certain policy positions given pressing issues (e.g. climate change). Rather, ECs influence preferences and outcomes through three causal dynamics: uncertainty, interpretation, and institutionalization. Decision-makers facing uncertainty with an unfamiliar topic will likely turn to ECs. They do so under the following circumstances: first, after shocks or crises, as they elucidate cause-and-effect relationships; second, when they are needed to shed light on complex inter-linkages between issues that may arise from action or lack of action; third, they define what is considered within the self-interest of the state or factions within the state, or redefine preconceived interests; finally, they formulate policies to given issues within their speciality (Haas 1992). The influence of the ECs ability to formulate policies depends on why their expertise is sought. For example, a decision-maker could just as easily seek their expertise because of uncertainty as they could to justify the means and ends of a pet policy. What sets ECs apart, however, is their relative resilience against pressures to change their results and conclusions made within their system. The combination of shared causal beliefs (i.e. scientific evidence) and shared principled beliefs offsets outside pressures to change tested and verified information. The relative solidarity of ECs derives from shared interests, cosmopolitan beliefs of promoting collective betterment, and. . 17 .

(24) shared aversions to policies outside their common policy enterprise or invoke policies based on unacceptable explanations (Haas 1992). Ultimately their greatest strength lies with their potential ability to create or change the prevailing ideas with which policy choices are made and with which policies persist. “How states identify their interests and recognize the latitude of actions deemed appropriate in specific issue-areas of policymaking are functions of the manner in which the problems are represented by those whom they turn for advice under conditions of uncertainty” (Haas 1992, 2). The role of science, and the sources consulted, thus becomes a potentially large factor in the decision-making process. “In modern societies, science is near to being the source of cognitive authority: anyone who would be widely believed and trusted as an interpreter of nature needs a license from the scientific community” (Haas 1992). This demand for information creates networks and communities of specialists capable of producing and providing information to emerge and proliferate within the larger society (Adler and Haas 1992). The prevailing community then becomes relatively strong actors on the national and transnational level, as decision makers solicit information and delegate responsibility to them. In turn, certain ECs may make their viewpoint become more influential through occupying niches in advisory and regulatory bodies. Within the Chinese system itself, this takes the form of research bodies (e.g. Asian International Rivers Center, AIRC), technical groups (Chinese Academy of Engineering), and the technical backgrounds of many of the higher-ups within the government itself. These ECs are channels through which new ideas circulate from societies to the government (or vice versa) and from country to country. ECs cannot be reduced to the ideas they embody or purvey, as these ideas and concepts come in tandem with a set of causal and principled beliefs, and therefore reflect a particular political vision. As a number of scholars have argued the increasing dominance of scientific discourse among policy-makers view it as a triumph of instrumental reason over fundamental interests within the government. Other authors view the increasing influence. . 18 .

(25) of specialized groups, such as ECs, as having serious negative implications for participation in the decision-making process, as decision-making is transferred to elite specialists, further limiting public-participation (Adler and Haas 1992). “Others have warned that privileging the advice of specialists in a particular domain such as engineering, may result in the generation of “bad” decisions, either because it leads to neglect of potentially valuable interdisciplinary insights or ignores the social ends to which decisions regarding the specific issues are directed” (Haas 1992, 22. Emphasis by the author) Indeed, it is this very privileging of advice from certain EC groups, and policy entrepreneurs, that may have contributed greatly to the policy frameworks surrounding the Lancang cascade. Specialized networks of ECs among and around policy-makers in China may be critical to the government’s, or rather those within the government making development decisions, understanding of the Lancang cascade itself. The concept of small networks of policy specialists and decision-makers within governments getting together to discuss and draft policy responses or alternatives to specific issues both in and outside official bureaucratic channels is nothing new, especially within the literature on China. These small networks work as brokers for admitting new ideas into decision-making circles of government officials. These networks have several terms describing them – such as coalitions (Mertha 2008) or bargaining knots (Wong 2010) – but describe roughly the same concepts of the small networks seen above. Gerke et al (2012) described physical “knowledge clusters” within the Mekong Delta, in relation to the knowledge networks that crop up within certain areas of Vietnam to address and research development impacts on the Mekong. These clusters tend to favor – as well as foster debate over – specific ideas, which then rise in prominence. These ideas are transferred to decision-makers through “tacit knowledge transfer”, the direct face-to-face (or via telephone after an initial meeting) communication of information to decision-makers by researchers within relatively close proximity. This may hold specific applications to the Lancang cascade development itself, and will be elaborated upon within the research. Consultation with ECs does not remove the politicization of scientific information, because, as many would argue, the ECs themselves each have a particular political vision with regards to the information with which they have specialty. In. . 19 .

(26) addition, the interpretation of the information and advice given by ECs is subject to the decision-makers understanding of behavior shaped by their own beliefs, motives, and intentions, thus shaping their responses and barriers to information considered valuable. Indeed, while experts may make decisions more rationally, policy choices remain highly political in decisions of allocative consequence. Ambiguous evidence, experts split into contending factions (or simple disagreements over evidence) lends itself to issues being resolved less on technical issues, but on political. The scientific method does not guarantee solidarity among the scientific community nor does it make it immune to outside pressures, although arguably resistant. “Power still matters. Epistemic communities are consequential only when their proposals are consistent with systemic and domestic political constraints or when it can persuade decisionmakers to support a specific policy. When there is disagreement within the community, political criteria, rather than technical ones, will be used to make a final decision. The ‘success’ of ideas is dependent on power, as a policy option is more likely to be adopted when a powerful state has committed itself to that option” (Haas 1992). The concept of ECs offers a unique analytical tool for hydropower development within China because it allows for an understanding of the available science to decision-makers via an understanding of what sets of scientific data are presented to them by various groups. This, in turn, allows for an understanding that should there be differing scientific conclusions on a given topic – in this case the biophysical, socioeconomic, and geopolitical impacts of the Lancang cascade on the Mekong region – researchers may be able to understand who determines what science is considered the best understanding of the cascade among key decision-makers, and why it is considered so. I believe that ECs are an explanatory tool yet to be fully utilized within the literature, but which may offer significant insights into understanding the role of science with hydropower development in China.. . 20 .

(27) Figure 1: The analytical framework of this study, featuring Lieberthal’s fragmented authoritarianism with Mertha’s additions as the primary understanding of China’s domestic political system, Kingdon’s multiple streams (MS) framework as a means of understanding the use of science in decision-making over time, and Haas’s epistemic communities framework to analyze the influence of research bodies in the decision-making process.. In sum, the analytical framework for this research is as follows: Kingdon’s “policy streams” framework will be used to not only understand the role of science examining the impacts of the Lancang dam cascade, but will also used to factor in parallel policy streams – development, energy demand, and climate change – that, in all likelihood, impacted the amount of influence dam impact science had within domestic politics and in decision-makers understanding of the cascades impact. When possible, the FA framework, with Mertha’s additions, will be used to understand the context within which these streams function, and as a means of understanding the actors and their actions taken in relation to their respective policy streams.. . 21 .

(28) 3.2 Literature review The follow consists of a literature review examining various perspectives on governance within China that may have some bearing on hydropower development decisions, as well as different research angles on the development of the Upper Mekong and its downstream impacts. Xie & van de Heijden have a slightly different take on the pluralization of China’s politics, the political opportunity structure (POS). POS is defined by how China’s government’s closed formal institutional structure, gradual decentralization from central to provincial governments, informal elite strategies, and power configurations are creating openings for environmentalists. Thus, they were able to analyze how different POS’s, at different points in time, led to completely different movement dynamics. They examined the anti-Three Gorges dam campaign (January 1989-April 1992) and the antiNu River campaign (August 2003-July 2004) and why the former was repressed and the latter had relative success. China’s POS in the early-1990s was dominated by elite power politics of Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping unfriendly to dissent, and strong advocates for the construction of the dams. As Heggleund (2004) describes, the political elites held very repressive attitudes towards social movements after the events of 1989. However, by 2003 under Jiang Zemin’s governance (1993-2003), the party had opened up greatly to more interest and willingness to involve environmental NGOs into environmental governance (Xie 2010, p 62). Movements in that time period allowed for politically connected activists like Ms. Wang, the leader of Green Environmental Volunteers in Yunnan. Ms. Wang had close connections with Mr. Mu, the previous vice chancellor of the supervision department of the MEP. Mr. Mu held a positive attitude towards environmental NGOs, with approval from higher ups in the MEP, gave Ms. Wang up to date information regarding the Nu river, and so was able to make a better campaign. Xie & van de Heijden’s work emphasizes the importance of personal networks, especially between state elites and non-state actors as crucial in organizing environmental campaigns and obtaining different resources (Xie, 2009; Xie & van der Heijden 2010). Another common construct of Chinese politics within the literature is that of factions within the CCP itself. Eluded to earlier in Xie & van der Heijden’s work,. . 22 .

(29) personal relationships within the CCP, and indeed Chinese society, have a strong history in the Chinese politics literature (Lieberthal 1995; Shi 1997; Shih 2004, Shih et. Al 2010). Victor Shih is one such author offering empirical evidence for the existence of personal relationships and their relation to factional politics within China. While commonly aimed specific at elite power politics and the likelihood and longevity of a given faction within the CCP (Shih et. al 2010), factional politics offers an insight into the potential decision making process behind the development of the Lancang/Mekong river. Factions have the potential for being an important causal factor in the funding of dams within Yunnan. As Shih found, there is empirical evidence indicating that: “…factional ties have an effect on the distribution of bank loans in reform era China. Moreover, statistical evidence shows that the intensity of factional ties has an independent effect on the allotment of banking resources to the provinces.” (Shih 2004) An investigation in the strength and possible impact of elite factional relationships on the specific development of the Lancang/Mekong river is beyond the scope of this study. However, the presence of factional politics and the possible redistribution of resources as a result may help to illuminate some of the development paths within Yunnan. Within China and Southeast Asia, there is a growing division of between proponents of dam construction (both inside and outside of China), and those opposed to it. According to Ken Conca (2006, 2008), authority under river systems becomes problematic when the separation of waterways into “international” or “domestic” (as China has done in its claims to development) conflicts with regional ecosystems and hydrological cycles. The presumption of state authority within this given territory comes into conflict as well as questions of culture, power, legitimacy and identity quickly become central to the dispute because material conflicts between upstream and downstream interests create disagreements about what the river means, which of its potential uses are legitimate, and who have the authority to shape its flow. Most importantly, the “knowledge stabilization” of river development becomes troublesome between pro-dam and anti-dam forces. Efforts to establish the boundaries of the impacts of river development has consistently been thwarted by new discoveries into the toll on. . 23 .

(30) freshwater biodiversity, ecological effects far downstream, dam-induced seismicity (Naik 2009), impacts on floodplain ecosystems, and greenhouse gas emissions from dam reservoirs. A study done by World Bank ecologist Robert Goodland (1997), found seventeen points of knowledge based disputes between pro-dam and anti-dam actors, including the nature and distribution of costs and benefits, the feasibility and desirability of alternatives, the capacity of governments to regulate effectively, and the essence of development. The proponents of hydropower development make several specific claims about the impacts of dams along the Mekong and the Lancang/Mekong river itself. While these claims are examined in-depth in chapter 2, it is worthwhile briefly examining them now to contextualize other approaches researchers have taken. Defending large-scale damming projects in Yunnan begun in the 1980s, China stated that only 16-20% of water that flows in the Mekong comes from China. This measurement, however, only represents a percentage of the total volume. By the time the river flows from it source to the Laotian capital of Vientiane, the quantity of water derived from China reaches 60% (Stoett 2005). In gross terms, the Upper Mekong contributes between 13.5-20% of the Mekong’s total discharge (depending on the source used), but in real terms, it contributes 100% of the flow at the Laos border and 60% as far downstream as Vientiane, 20% at Pakse in southern Laos, 15-20% in Vietnam, 16% at Phnom Penh (Stoett 2005). The Lancang/Mekong dam cascade offers a huge opportunity in energy production, especially on an 800 meter drop over the course of a 750 kilometer stretch of the middle and lower sections of Yunnan’s portion (Plinston & He 2000). For dam builders, this section offers what is described as a “rich, rare hydropower mine for its prominent natural advantages in abundant, well-distributed runoff, large drops, and less flooding losses of the reservoirs” (Dore 2004). More generally, proponents of Lancang/Mekong hydropower argue that the dams have the potential for flood control, the ability to provide more water in the dry season while retaining water during the wet season, increased navigation options, reduced saline intrusion, and create more irrigation opportunities for downstream nations like Thailand. Most importantly the cascade has massive potential for electricity production with an estimated 15,550 MW of installed capacity once the cascade is complete (Goh, 2004). This is part of China’s west-to-east energy transfer plan (西電東. . 24 .

數據

Outline

相關文件

Given its increasing importance in the governmental decision-making, this paper is first to explore several critical issues concerning the utilization of CBA in the public

The first row shows the eyespot with white inner ring, black middle ring, and yellow outer ring in Bicyclus anynana.. The second row provides the eyespot with black inner ring

In the process of visual arts appreciation, criticism and making, students explore the aesthetic qualities of visual arts works, pursue various aesthetic theories, as

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

In implementing the key tasks, schools should build on past experiences and strengthen the development of the key tasks in line with the stage of the curriculum reform, through

主頁 > 課程發展 > 學習領域 > 中國語文教育 > 中國語文教育- 教學 資源 > 中國語文(中學)-教學資源

using & integrating a small range of reading strategies as appropriate in a range of texts with some degree of complexity,. Understanding, inferring and

FOUR authentic cases on ethical decision making in business are adopted in the case studies available on the website of the Hong Kong Ethics Development Centre