語音表義教學對國中生英語字彙記憶之效益研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 英國 國立 語政 文治 學大 系學 碩 士 在 職 專 班 碩 士 論 文 ︻ 之語 效音 益表 研義 究教 學 對 國 中 生 英 語 字 彙 記 憶 ︼ 王 靜 鴻 撰. Ch. engchi. ii. i n U. v.

(3) The Effects of Sound Symbolism Instruction on Junior High School. Students’ English Vocabulary Memorization. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English,. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. National Chengchi University. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Ching-hung Wang May 21. iii.

(4) The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Ching-hung Wang defended on May 21.. Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh Professor Directing Thesis. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Dr. Chen-kuan Chen. n. al. y er. io. sit. Nat. Committee Member. Ch. engchi. i n U. Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu Committee Member. Approved:. Huei-ling Lai, Chair, Department of English. iv. v.

(5) To Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh 獻給我的恩師葉潔宇博士. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(6) Acknowledgements I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh, who carried the torch when the flame had all but burnt out and who patiently helped me complete this thesis. Without her encouragement, guidance and support, I could not make this work possible. I would like to thank the committee members, Dr. Chen-kuan Chen and Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu, for their reading of the manuscript and for helpful suggestions and other support.. 政 治 大 throughout the work including Pi-cheng Wu, An-hui Cheng, Nai-ting Chiu, Chih-chun 立. Special thanks go to many of my colleagues and friends who gave me support. Lin, Ling-yu Wang, Tung-hsien Kao, Ya-wen Chen, Po-sheng Peng, and many others. ‧ 國. 學. too numerous to mention.. ‧. Finally, and most certainly I thank my family, my mother, my sister and my. y. Nat. brother, without whom I never would have made it anywhere. I shall thank them for. n. al. er. io. you all. I love you.. sit. always being there for me. It is to them that this thesis is gratefully dedicated. Thank. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..........................................................................................vi TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................vii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................xi LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................... xiii ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................xv CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................1. 政 治 大 Background and Motivation ..................................................................................1 立. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1. Purpose of the Study ..............................................................................................2. ‧ 國. 學. Research Questions................................................................................................2. ‧. Significance of the Study .......................................................................................3. y. Nat. Definition of Terms................................................................................................3. er. io. sit. Knowing a Word ............................................................................................3 Instruction of Sound Symbolism ...................................................................4. al. n. v i n Ch CHAPTER TWO ...........................................................................................................5 engchi U LITERATURE REVIEW...............................................................................................5 Vocabulary Learning Strategies in Terms of Sounds .............................................5 Sound Symbolism ................................................................................................10 The Definition of Sound Symbolism ........................................................... 11 The Categories of Sound Symbolism ..........................................................12 Corporeal Sound Symbolism ...............................................................12 Imitative Sound Symbolism.................................................................13 Synesthetic Sound Symbolism.............................................................14 Conventional Sound Symbolism..........................................................15 Research on Sound Symbolism ...................................................................17 vii.

(8) Sound Symbolism and English Vocabulary Teaching .........................................19 Table 2.1 Related Studies on Sound Symbolism .........................................................21 CHAPTER THREE .....................................................................................................22 METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................22 Participants...........................................................................................................22 Table 3.1 Statistics of Participants’ English Proficiency Test Scores ..........................23 Table 3.2 Independent Samples t-test on Participants’ English Proficiency Test........23 Instruments...........................................................................................................23 The 2009 2nd English Test of the Basic Competence Test (EBCT) .............24. 政 治 大 A Test for Word Selection ............................................................................24 立 A Pre- and Post-test in Word Recognition in Relation to Meanings............28. ‧ 國. 學. Think-aloud Method ....................................................................................30. ‧. Interviews.....................................................................................................32. y. Nat. Vocabulary Instruction .........................................................................................32. er. io. sit. Procedure .............................................................................................................35 Pilot Study....................................................................................................36. al. n. v i n Ch Main Study...................................................................................................38 engchi U. Data Analysis .......................................................................................................38 CHAPTER FOUR........................................................................................................41 RESULTS.....................................................................................................................41 Results of the Pre-test and Post-test.....................................................................41 Results of the Think-aloud Method .....................................................................44 Results of the Interviews......................................................................................54 Ways to Memorize New Words ...................................................................55 Views on the Instruction of Sound Symbolism............................................61 Summary ..............................................................................................................73 viii.

(9) CHAPTER FIVE .........................................................................................................75 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION..........................................................................75 Answers to the Research Questions.....................................................................75 Discussion of the Comparison Between the Present Study and the Previous Studies..................................................................................................................77 Consistent Findings with the Previous Research .........................................77 Inconsistent Findings and New Findings.....................................................79 Pedagogical Implications of the Study ................................................................85. 政 治 大 Recommendations for Further Research..............................................................87 立 Limitations of the Study.......................................................................................86. Conclusion ...........................................................................................................88. ‧ 國. 學. REFERENCES ............................................................................................................90. ‧. Appendix A: The 2009 2nd EBCT................................................................................97. y. Nat. Appendix B: Word Selection Test.............................................................................. 110. er. io. sit. Appendix C: The Pre-and-Post Test........................................................................... 113 Appendix D: The Think-aloud Sheet ......................................................................... 114. al. n. v i n Ch Appendix E: Interview Questions..............................................................................116 engchi U. Appendix F: Teaching Material ................................................................................. 117 Appendix G: The Pre-and-post Test in the Pilot Study..............................................134 Appendix H: The Think-aloud Sheet in the Pilot Study ............................................135 Appendix I: Questionnaire in the Pilot Study ............................................................136 Appendix J: Teaching Material in the Pilot Study .....................................................137 Appendix K: The Results of the Questionnaire in the Pilot Study ............................139 Appendix L: A Sample of the Interview Transcription..............................................140 Appendix M: Schmitt’s Taxonomy of Vocabulary Learning Strategy.......................142 Appendix N: 1000-word List Stipulated by MOE (2003) .........................................144 ix.

(10) Appendix O: 1200-word List Stipulated by MOE (2008) .........................................148. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) LIST OF TABLES. Table 2.1 Related Studies on Sound Symbolism……………………………………..21 Table 3.1 Statistics of Participants’ English Proficiency Test Scores ..........................23 Table 3.2 Independent Samples t-test on Participants’ English Proficiency Test ......23 Table 3.3 Word Frequency from BNC of 85 Words Selected ………………………..27 Table 3.4 The 80 Target Words……………………………………………………….28 Table 3.5 The Target Words & The Test Items……………………………………….30. 政 治 大 Table 4.2 Independent Samples t-test on Participants’ Pre-Test……………………..42 立. Table 4.1 Statistics of Participants’ Pre-Test & Post-Test Scores…………………….42. Table 4.3 Independent Samples t-test on Participants’ Post-Test……………………43. ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.4 Paired Samples t-test for Progress in the Experimental Group……………43. ‧. Table 4.5 Performance of the High Group in the Post-test & Think-aloud Task…….47. y. Nat. Table 4.6 Performance of the Low Group in the Post-test & Think-aloud Task……..49. er. io. sit. Table 4.7 The Use of Sound Symbolism of the Participants with Good Performance……………………………………………………………….53. al. n. v i n C hLearning Strategies…………………………….56 Table 4.8 Interviewees’ Vocabulary engchi U Table 4.9 No. of Mentions* of the Vocabulary Learning Strategies in the. High and Low Groups: Meaningful Learning vs. Rote Learning…………59 Table 4.10 No. of Mentions* of the Vocabulary Learning Strategies in the High and Low Groups: Sound-related vs. Non-sound Related……………59 Table 4.11 Interviewees’ Reported Reasons for Vocabulary Loss……………………60 Table 4.12 Results of the yes-no questions in the interviews………………………...63 Table 4.13 Results of Q1, Q3 & Q 7 in the High and Low Groups………………….67 Table 4.14 Interviewees’ Comments on the Instruction of Sound Symbolism………68 Table 4.15 Comments on the Instruction of Sound Symbolism Made by the xi.

(12) High & Low Groups……………………………………………………..72 Table 4.16 Interviewees’ Suggestions on the Instruction of Sound Symbolism…….72. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xii. i n U. v.

(13) LIST OF FIGURES. Figure 3.1 The Procedure of Word Selection…………………………………..…….26 Figure 3.2 The Procedure of the Instruction of Sound Symbolism…………..……....34 Figure 3.3 The Whole Procedure of the Study…………………………………...…..36 Figure 4.1 Proportion of Correct Responses Based on Sound Symbolism to Total. Correct Responses in the Post-test…………………………….51. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiii. i n U. v.

(14) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:語音表義教學對國中生英語字彙記憶之效益研究. 指導教授:葉潔宇博士. 研究生:王靜鴻. 論文提要內容:. 立. 政 治 大. 語音表義教學雖已被學者提倡使用在字彙學習之領域多年,然而其在課室英. ‧ 國. 學. 語字彙教學的實際成效仍未獲證實。本研究先採用量化研究方法以探究語音表義. ‧. 教學對於國中生英語單字記憶之成效,再採用質性研究方法探討受試者對語音表. y. Nat. 義教學法之看法。. er. io. sit. 研究對象為台灣北部一所公立國中九年級兩個班的七十二位學生。此均質的 兩個班級被隨機指定為實驗組與控制組,實驗組施予語音表義教學法學習八十個. al. n. v i n 標的單字,而控制組則施予傳統翻譯式教學法學習相同的單字。接受歷時十六週 Ch engchi U 的字彙教學後,以兩組學生在認字測驗上的成績以及實驗組學生個別訪談之結果 作為資料分析來源。本研究主要發現如下:(1)接受語音表義教學的實驗組學生 在認字測驗的表現上顯著優於接受傳統翻譯法的控制組學生。(2)實驗組中,高 分群組與低分群組在接受語音表義教學後,在認字測驗的表現上皆呈現出顯著性. 進步,顯示出語音表義教學對不同程度的學生皆有成效。(3)受試者對語音表義 教學持正面態度,且認為語音表義教學特別是在認字方面有助於英語字彙之記 憶。研究最後進一步對語音表義教學在實際教學上之應用提供建議,作為教育學 者們參考。. xiv.

(15) ABSTRACT. Although the instruction of sound symbolism has been advocated for word learning for years, it is not clear whether it is empirically effective in classroom vocabulary teaching. This study first adopted a quantitative research method to investigate the effectiveness of the instruction of sound symbolism on junior high school students’ English vocabulary memorization, and then a qualitative research method to explore the participants’ perspectives on the instruction of sound. 政 治 大 Participants of the study were two classes of 72 ninth-grade students in a public 立. symbolism.. junior high school in northern Taiwan. With homogeneity in terms of English. ‧ 國. 學. language proficiency, the two classes were randomly assigned as the experimental and. ‧. control group. The former was instructed 80 target words by the instruction of sound. y. Nat. symbolism, while the latter was taught the same target words by the traditional. er. io. sit. translation-based approach. Vocabulary instruction lasted for 16 weeks, and the data analysis was based on their performances on the word recognition test and the results. al. n. v i n C hmajor findings areUas follows. (1)The participants of the individual interviews. The engchi who received the instruction of sound symbolism performed significantly better on. the word recognition test than those who were taught the traditional translation-based approach. (2) In the experimental group, both the high and low proficiency learners made significant progress, indicating the instruction of sound symbolism was effective in different proficiency groups. (3) The participants held positive attitude toward the instruction of sound symbolism and felt that the instruction was helpful for vocabulary memorization, especially on the aspect of word recognition. Some pedagogical implications and recommendations for future research were presented at the end of the thesis. xv.

(16) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background and Motivation The field of EFL teaching has undergone many fluctuations and shifts over the decades and one of the most fruitful areas is on vocabulary teaching. Since the end of the 20th century, vocabulary teaching has become more important under the influence of Communicative Language Teaching (Brown, 2001). Vocabulary instruction plays a crucial role in English learning because of its great impact on listening, speaking,. 政 治 大 learning as follows. “Without grammar very little can be conveyed; without 立. reading and writing. Wilkins (1972) summed up the importance of vocabulary. vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (p.111). It is clear that vocabulary is central to. ‧ 國. 學. language and vocabulary teaching is of critical importance to enable learners to. ‧. acquire language proficiency (Zimmerman, 1997). Lack of vocabulary knowledge. y. Nat. will result in lack of meaningful communication. In other words, without an extensive. er. io. effective communication.. sit. vocabulary, learners will not be able to utilize the grammar they have learned for. al. n. v i n Several decades of researchCon the analysis of sound, h e n g c h i U form and meaning of words. have yielded various methods for teaching vocabulary, such as Keyword Method, morphologically-based vocabulary teaching, and vocabulary teaching in context. However, the principal focus of vocabulary has been on the form and meaning of. words. Many researchers proposed that language teachers should pay more attention to the sound of words in vocabulary teaching. Huang (1999) pointed out that Chinese students often learn word-by-word English-Chinese translation through rote learning, which makes vocabulary learning difficult for them; therefore, the aspect of sound of words may be emphasized during the vocabulary instruction because English is an alphabetic system and sound plays a critical role. Huang (1999) and Mo (2005) 1.

(17) suggested that the connection between sound and meaning should be applied to EFL vocabulary teaching. Nevertheless, within the extensive literature on vocabulary learning strategies, comparatively little research has focused on the dimension of sound. Only some taxonomies of vocabulary learning strategies (Gu & Johnson,1996; Lin, 2001; Schmitt, 1997; Stoffer, 1995; Wang, 2004) included categories related to sound. Among them, none elaborated in depth. Furthermore, despite the fact that Chen (2000) and Mo (2005) advocated the instruction of sound symbolism, little empirical research has combined sound symbolism with English vocabulary teaching. As a. 政 治 大. result, there is a need for more investigation.. 立. Purpose of the Study. ‧ 國. 學. The purpose of this study was to investigate if the use of sound symbolism would. ‧. facilitate junior high school students’ English vocabulary memorization. By. y. Nat. examining the participants’ performances on the word recognition test, the researcher. er. io. sit. investigated whether the students receiving the instruction of sound symbolism outperformed those who were under traditional translation-based approach, as alleged. al. n. v i n C hwas the instructionUeffective for both high and low in previous research. If so, further, engchi proficiency learners? In addition, the researcher also intended to probe into the. participants’ perspectives on the instruction of sound symbolism and explore the pros and cons of the instruction, by which some suggestions may be made to improve the instruction of sound symbolism in the future.. Research Questions The main focus of the present study was on the investigation of the effectiveness of the instruction of sound symbolism. Consequently, this study was designed to allow the exploration of the following three research questions: 2.

(18) (1) Do students who receive the instruction of sound symbolism perform better than those who are taught the traditional translation-based approach on vocabulary memorization? (2) Is the instruction of sound symbolism effective for high and low proficiency learners respectively? (3) How do students think about the instruction of sound symbolism? How can the instruction be improved?. 政 治 大 One of the perennial difficulties EFL learners encounter is vocabulary learning. 立 Significance of the Study. Most learners consider vocabulary to be their language learning difficulty (Candlin,. ‧ 國. 學. 1988). Surprisingly, in spite of the introduction of the various vocabulary teaching. ‧. methods, vocabulary learning remains a difficult task for many students. It was. y. Nat. expected that the instruction of sound symbolism may be a useful alternative in EFL. er. io. sit. vocabulary teaching since morphology can not analyze a great amount of English vocabulary of junior high level in Taiwan. Previous reseachers believed that the. al. n. v i n instruction of sound symbolismC was effective on English h e n g c h i U vocabulary teaching and. learning, and hopefully the present study may provide evidence to their claim through an experimental research design.. Definition of Terms Knowing a Word In this study, knowing a word referred to word recognition, linking the form of a word with its meaning. According to Nation (2001), vocabulary knowledge can be categorized into receptive and productive knowledge. In terms of receptive vocabulary knowledge, knowing a word signifies the ability to recognize the word 3.

(19) with its written form and know what the word means. On the other hand, concerning productive vocabulary knowledge, knowing a word designates the ability to write it with correct spelling and use the word to express the meaning. Following Nation’s definition, the present study merely examined the dimension of receptive vocabulary knowledge because this was a preliminary study which was not designed to be so challenging for the participants.. Instruction of Sound Symbolism. 政 治 大 vocabulary teaching method which teaches students to utilize sound symbolism, i.e. 立 In the present study, the instruction of sound symbolism was defined as the. the relationship between sound and meaning of a word, to memorize English. ‧ 國. 學. vocabulary. For example, when pronouncing /a/ sound, students need to open their. ‧. mouths wide and keep their tongue in a low position. By connecting sound with. y. Nat. meaning through manner of articulation, the letter “a” connotes “largeness” and. n. al. er. io. sit. “lowness,” which can be used to help students memorize words such as vast and base.. Ch. engchi. 4. i n U. v.

(20) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW In this chapter, the literature on the instruction of sound symbolism was reviewed in three parts. The first part describes vocabulary learning strategies in relation to sounds; the second introduces sound symbolism, and the last is the application of sound symbolism to English vocabulary teaching.. Vocabulary Learning Strategies in Terms of Sounds. 政 治 大 strategies as well as a subcategory in the framework of language learning strategies. 立 Vocabulary learning strategies can be considered as a subset of learning. They are strategies which word learners employ in learning and storing new words for. ‧ 國. 學. later recall and use (Nation, 2001). Various definitions of vocabulary learning. ‧. strategies have been proposed over the course of decades of research. Hatch and. y. Nat. Brown (1995) divided vocabulary learning strategies into five essential steps in the. er. io. sit. process of learning vocabulary: (1) encountering new words, (2) creating a mental picture, either visual or auditory or both, of word form, (3) learning the words’. al. n. v i n C h between word form meaning, (4) creating a strong linkage and meaning in the engchi U. memory, and (5) using words. From this point of view, most of the vocabulary learning strategies were in association with these five steps. Based on O’ Malley and Chamot’s (1990) definition of learning strategies1, Schmitt (1997) claimed that vocabulary learning strategies might be thought of as any which affect the process by which information is obtained, stored, retrieved, and used. Cameron (2001) suggested that vocabulary learning strategies referred to actions which learners take to understand and remember words. Jiménez Catalán (2003) defined vocabulary learning. 1. O’ Malley and Chamot (1990) defined learning strategies as “the special thoughts or behaviors that individuals use to help them comprehend, learn or retain new information” (p.1). 5.

(21) strategies as knowledge about the mechanisms utilized to learn vocabulary and steps or actions taken to (1) find out the meaning of unknown words, (2) retain them in long-term memory, (3) recall them at will, and (4) use them in oral or written mode. Among the different definitions mentioned above, the basic concept of vocabulary learning strategies is about how to obtain, retain and use vocabulary. Nation (2001) believes that a great amount of vocabulary can be acquired by the use of vocabulary learning strategies and that vocabulary learning strategies prove beneficial to students of different language levels.. 政 治 大 language learning strategies and classifications which indicate that many 立. Research into vocabulary learning strategies was usually a part of general. multi-purpose strategies can be used in vocabulary learning (Takač, 2008). Most. ‧ 國. 學. studies on vocabulary learning strategies have focused on the investigation of a small. ‧. set of vocabulary learning strategies such as vocabulary strategies used in reading,. y. Nat. various methods of vocabulary presentation and their effects on retention. For. er. io. sit. instance, the most studied vocabulary learning strategies are memory strategies (Gu and Johnson, 1996). Only a few of them took a holistic view to explore vocabulary. al. n. v i n C h accounts of vocabulary learning strategies and provide elaborate learning strategies engchi U (Cheng, 2006). Although recent publication in the field of vocabulary learning. strategies reported a lack of taxonomy development (Kojic-sabo & Lightbown, 1999), related research does exist. Different classification systems of vocabulary learning strategies have been proposed by different scholars. However, as far as sound is concerned, few studies discussed vocabulary learning strategies from the aspect of sounds in depth. The taxonomies which contain sound-related strategies were briefly introduced below. Cook and Mayer (1983) categorized vocabulary learning activities into two groups: Discovery strategies and Consolidation strategies. The former included 6.

(22) Determination strategies and Social strategies. The latter comprised Social, Memory, Cognitive and Metacognitive strategies. Among the strategies classified by Cook and Mayer, some mentioned the dimension of sound: (1) Ask someone who knows the L1 translation, and pronunciation of the target word or any combination of these. ( from the Social strategies subsumed under Discovery strategies) (2) Link unrelated words together by the utilization of rhymes and images2. (from the Memory strategies subsumed under Consolidation strategies) (3) Study word’s orthographical or phonological form3. (from the Memory strategies. 政 治 大 subsumed under Consolidation strategies) 立. Next, even though Sanaoui’s classification (1995) was far from a full-blown. ‧ 國. 學. taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies, she identified two approaches to. ‧. vocabulary learning: a structured and an unstructured approach as two extremes of a. y. Nat. continuum. With regard to sounds, word learners who employed a structured approach. er. io. sit. to learn new words took initiatives in creating opportunities for learning vocabulary by listening to the radio, watching videotapes, and speaking with friends.. al. n. v i n C h learning strategies The first investigation of vocabulary as a whole was carried engchi U. out by Stoffer (1995). Her categorization, consisting of 53 Vocabulary Learning. Strategy Inventory items, was divided into nine groups, one of which was in relation to sounds, i.e. visual / auditory strategies. Gu and Johnson’s (1996) study developed a survey questionnaire to compare Chinese EFL learners’ frequency of vocabulary learning strategy use with their beliefs 2. For instance, Peg Method is that a word learner first memorizes a rhyme like “zero the hero, one is a bun, two are shoes, three standing trees, four knock on door, five bees in hive, etc” and then creates an image of the word to be remembered and the peg word. This method is good for students with stronger auditory preferences. 3 Keyword Method is an example of the use of word’s phonological form, which was investigated most extensively. It entails a word learner associating the word in L1 which sounds like the target word, and then create an image to combine the two concepts. 7.

(23) about vocabulary learning, level of development of learners’ vocabulary and learning success. The 91 strategies in the questionnaire statements proposed by Gu and Johnson could be grouped into seven major dimensions, i.e. “Metacognitive regulation,” “Guessing strategies,” “Dictionary strategies,” “Note-taking strategies,” “Rehearsal strategies,” “Encoding strategies,” and “Activation strategies” (Cheng, 2006). Among those strategies devised by Gu and Johnson (1996), three were sound-related. One was oral repetition, which was subsumed under the dimension of “Rehearsal strategies,” another was auditory encoding, which was included in the. 政 治 大 image link between an L2 word to be learned and a word in L2 that sounds similar, 立. dimension of “Encoding strategies,” and the other was establishing an acoustic and. which was under the dimension of “Activation strategies.” In addition, their research. ‧ 國. 學. finding also pointed out that Chinese learners were generally less likely to use. ‧. auditory encoding strategies than other strategies.. y. Nat. The classification proposed by Schmitt (1997) was adopted from Oxford, who. er. io. sit. grouped learning strategies but did not categorize strategies specifically for vocabulary learning. Schmitt’s (1997) taxonomy comprised 58 individual strategies,. al. n. v i n C hgroups, i.e. Discovery which were divided into two major and Consolidation engchi U. strategies, and were subdivided into five categories, i.e. Determination (DET), Social (SOC), Cognitive (COG), Memory (MEM) and Metacognitive (MET) strategies. Even though his taxonomy was one of the most comprehensive classifications of vocabulary learning strategies, the discussion regarding sounds was quite limited for only six out of the fifty-eight strategies were relevant to sounds. More specifically, the categories in his taxonomy related to sounds are “study the sound of a word,” “Say new word aloud when studying,” “Use Keyword Method,” “Verbal repetition,” “Listen to the tape of word lists,” and “Use English-language media (songs, movies, newscasts, etc.),” none of which was proposed with explication. All of the above 8.

(24) sound-related strategies belonged to Consolidation strategies in Schmitt’s taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies. Furthermore, Schmitt’s (1997) research also indicated that older people tended to make use of deeper processing strategies such as the Keyword Method, making word associations through sounds. In addition to Schmitt’s work, Lin (2001) identified 73 vocabulary learning strategies in her research on Taiwanese children’s vocabulary learning, which were categorized into three parts: Metacognitive, Cognitive, and Socio-affective, each of which had its subcategories. There were four subcategories under Metacognitive. 政 治 大 Self-management. There were ten subcategories under Cognitive category: Written 立 category: Advanced preparation, Selective attention, Monitoring, and. repetition, Verbal repetition, Segmentation, Phonics application, Association,. ‧ 國. 學. Resourcing, Predicting, Elaborating, Recalling, and Others. There were three. ‧. subcategories under Socio-affective category: Asking for help, Cooperation, and Other.. y. Nat. In Lin’s taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies, 22 out of 73 strategies were. er. io. sit. relevant to sound4. They are (1) Write down the KK phonetic symbols of English vocabulary, (2) Divide the target words into segments according to their sounds, (3). al. n. v i n C h words, (4) Pay attention Check L2 pronunciation of the target to silent letters in the engchi U. target word, (5) Listen to English textbook cassettes, (6) Use English learning media, (7) Repeat entire lexical item or difficult parts of a lexical item letter by letter, (8) Repeat entire lexical item by sounds, (9) Make it easier for letter-by-letter verbal or written repetition, (10) Memorize the target word by its sounds, (11) Apply phonics intentionally when the patterns of phonics work, (12) Apply phonics automatically, (13) Apply false phonics patterns intentionally when the patterns of phonics do not work, (14) Create a pattern of phonics when the learned phonics patterns do not work, 4. The strategy Listen to English textbook cassettes was listed under both Self-management category and Resourcing category in Lin’s taxonomy. Likewise, the strategy Sound association was listed under both Association category and Recalling category. 9.

(25) (15) Sound association, (16) Auditory recall, (17) Read English texts aloud, (18) Ask teachers, family members or classmates for L1 meaning and/ or L2 pronunciation, (19) Read aloud lessons in English textbooks with family members, and (20) Speak to family members in simple English phrases or sentences. Finally, in Wang’s (2004) review of important vocabulary learning strategies in her research on vocabulary learning strategies used by senior high school students in Taiwan, she noted that using aural imagery strategies means that learners can use similar sounds or rhymes to remember a new word in the target language. Wang (2004). 政 治 大 many word learners are not aural learners but rather visual ones or combination ones. 立 indicted that due to the culture factor or the influence of the current electronic media,. In conclusion, except for the related studies mentioned above, as far as the. ‧ 國. 學. researcher is concerned, other taxonomies of vocabulary learning strategies such as. ‧. Kudo’s (1999), Nation’s (1990; 2001), O’Malley and Chamot’s (1990), and Williams’. y. Nat. (1985) classification systems seldom included strategies relevant to sounds. To sum. er. io. sit. up, few studies on taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies dealt with sounds in depth in literature. Even if sound category was included in the classification schemes,. n. al. it was not elaborated.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Sound Symbolism In the previous section, it is noted that to date, most research on vocabulary learning strategies lays great emphasis on word meaning; little, if any, stresses the investigation of sound-related dimension. Consequently, the present research places sound symbolism in the spotlight. Generally speaking, linguistic theories presume that the link between sound and meaning is arbitrary. Saussure (1959) considered language to be system of signs in which there is an arbitrary relationship between sound and meaning, claiming that sound is not directly related to its meaning and vice versa. He 10.

(26) even claimed that sound does not have intrinsic meanings itself. This perspective of language was accepted by the later Structuralists. However, a small number of words were found as counterexamples for this viewpoint, such as onomatopoeias. Another counterexample was some of children’s earliest words, which belong to the non-arbitrary category, like moo cows. The Generative Phonologists thus held an opposite opinion to Structuralists toward this issue, contending that the link between sound and meaning is not arbitrary, and thereafter had a tremendous influence on the following research on the sound-meaning relationship.. 政 治 大 symbolism with the belief that onomatopoeias are not the only exception to Saussure’s 立 In literature, a great number of cross-linguistic data have been reported on sound. (1959) arbitrariness argument. In this section, the related studies on sound symbolism. ‧ 國. 學. were discussed from three aspects: (1) the definition of sound symbolism, (2) the. io. sit. The Definition of Sound Symbolism. er. Nat. y. ‧. categories of sound symbolism, and (3) research on sound symbolism.. Jakobson and Waugh (1987) defined sound symbolism as “an inmost, natural. al. n. v i n C h and meaning” (p.U182). Jakobson believed that similarity association between sound engchi the importance of sounds lies not only in the inter-relationships among sounds, but. also in synesthesia which sounds bring to hearers perceptually, and the existence of synesthesia is sound symbolism (Reichard, Jakobson & Werth, 1949). Fordyce(1988) called sound symbolism as phonosemantics, both of which are the specific study of the direct relationship between sound and meaning. According to Bolinger (1992), sound symbolism might be thought of as “that form of iconicity in which the nature of the sound resembles what the sound stands for” (p.28). That is, if the things sound alike, they are supposed to mean alike, and if they mean alike, they ought to sound alike. In Parault and Parkinson’s (2008) research, sound symbolism referred to “the 11.

(27) idea that there can be a relationship between a word’s sounds and its meaning and that this relationship does not have to be imitative in nature like onomatopoeias” (p.648). As a whole, the study of Hinton, Nichols and Ohala (1994) is the most significant recent effort to describe the role of sound symbolism, offering a quite broad definition: “Sound symbolism is the direct linkage between sound and meaning” (p.1). Numerous studies have offered various names for the concept; however, the definition and spirit given to sound symbolism were the same (Chen, 2000).. The Categories of Sound Symbolism. 政 治 大. Hinton et al. (1994) took a great interest in sound symbolism and divided the. 立. concept of sound symbolism into four categories: corporeal, imitative, synesthetic and. ‧ 國. 學. conventional sound symbolism. These four different types of sound symbolism are arranged below according to the degree of direct linkage between sound and meaning.. ‧ y. Nat. sit. Corporeal Sound Symbolism. n. al. er. io. Corporeal sound symbolism is “the use of certain sounds or intonation patterns to. i n U. v. express the internal state of the speaker, emotional or physical” (ibid. p2). In terms of. Ch. engchi. English writing traditions, this kind of words are typically structurally simple, non-segmentable vocalizations and they are usually presented by expressive intonation and voice quality, such as Atchoo and Ouch. Due to the fact that corporeal sound-symbolic words are directly related to the emotional or physical state of the speaker, they rarely occur as parts of complex sentences. Hinton et al. also mentioned a type of sound symbolism which is related but tangential to corporeal sound symbolism, i.e. vocative sound symbolism. Vocatives have some similarities to corporeal sound symbolism. For example, both of them result from the change of the speaker’s physical state. However, vocative sound 12.

(28) symbolism has the function of gaining the hearer’s attention, such as the crying of a child, the scream of someone in danger, or the sound made by clearing the throat. Therefore, an argument was made that corporeal sound symbolism is not properly sound symbolism because the sound in this category is “not a true symbol, but rather a sign or symptom” (ibid. p2).. Imitative Sound Symbolism Imitative sound symbolism refers to onomatopoeias, representing environmental sounds like bang, bow-wow, swish, knock and ding-dong, which represent repeated. 政 治 大. sounds or movements with reduplication. In other words, onomatopoeic words are. 立. those imitate the natural sounds of actions or objects with which they are associated.. ‧ 國. 學. This category involves a direct imitation of the rhythmic movement by the utilization of sound. Although imitatives make use of sounds outside the conventional speech. ‧. and are difficult to describe in writing, such as representations of bird or animal. y. Nat. sit. sounds, a lot of the onomatopoeic words have become conventionalized. As. n. al. er. io. Jerspersen (2007) observed, due to the fact that sound is always produced by some. i n U. v. movement, the movement itself may be presented by the word for its sound such as. Ch. engchi. bang the door. Lu (1998) pointed out that the existence of onomatopoeia is a matter of language habit. Jerspersen (2007) held a similar opinion and stated: As our speech-organs are not capable of giving a perfect imitation of all ‘unarticulated’ sounds, the choice of speech sounds is to a certain extent accidental, and different nations have chosen different combinations, more or less conventionalized, for the same sounds. (p.398) In addition, Lu (1998) contended that onomatopoeia is one of the sources of coining new words. Jerspersen (2007) provided an example to support this claim. The verb bang in the phrase bang the door came from the onomatopoeia. He also 13.

(29) proposed an explanation for this means of creating new words, that is, as sound is always made by an action, it is natural to express the action with the word for its sound.. Synesthetic Sound Symbolism Hinton et al. (1994) defined synesthetic sound symbolism as “the acoustic symbolization of non-acoustic phenomena” (p.4). According to Hinton et al. (1994), synesthetic sound symbolism is the process by which some vowels, consonants, and suprasegmentals are chosen to represent visual or tactile properties of objects like size. 政 治 大. or shape. Jespersen (1922) argued that there was a natural association between high. 立. tone and light and between low tone and darkness. The vowel /i/ had the connotation. ‧ 國. 學. of something small, slight, insignificant, or weak. The possible reason is the manner of articulation of the sound; that is, the oral cavity is relatively smaller.. ‧. Sapir (1929) conducted a series of psycholinguistic experiments and found that. y. Nat. sit. the participants tended to connect /a/ sound with the concept of largeness, while. n. al. er. io. associate /i/ sound with the concept of smallness. In addition, the participants were. i n U. v. prone to link front vowels to the smallness concept. Finally, /i/ sound carries. Ch. engchi. connotation of smallness and quickness, while /o/ sound connotes largeness and inactiveness. In response to Sapir’s experiments, Fordyce (1988) pointed out that once a sound was associated with a meaning, based on the association, the meaning of an unknown word may be predictable. In Ultan’s (1978) research, up to 90% of the words with the connotation of diminutiveness included high front vowels. In terms of suprasegmental features, the rising or falling of the intonation, the strengthening or lengthening of a sound brings synesthesia to the hearer. For example, in speaking of the sentence “It was a bi-i-ig fish!” the use of a lengthened vowel in a deep voice could make the hearer feel how large the size of the object was. The above findings 14.

(30) pertinent to sound symbolism in Sapir’s and Ultan’s experiments fell into the category of synesthetic sound symbolism. In Fordyce’s (1988) research of sound symbolism with special reference in English, synesthetic sound symbolism was called “translucent iconicity” and size-sound symbolism provided evidence for sound-meaning iconicity in language. A typical manifestation of size-sound symbolism was the representation of smallness and nearness by the high front vowel /i/. Citing Tolman’s (1877) findings on sound-metaphor, Fordyce (1988) further indicated that the front unrounded vowels. 政 治 大 gayety, triviality, rapid movement, delicacy, and physical littleness,” while the low, 立. and diphthongs of English are suggestive of “uncontrollable joy and delight, excessive. back rounded and unrounded vowels and diphthongs, on the other hand, express. ‧ 國. 學. “largeness, slowness, seriousness, and gloom.”. ‧. Overall, this category of sound symbolism is further along the continuum toward. y. Nat. the arbitrariness than the previous two categories, corporeal and imitative sound. er. io. sit. symbolism, in that exceptions to synesthetic sound symbolism, to a great extent, are prevalent (Hinton, et al., 1994).. n. al. Ch. Conventional Sound Symbolism. engchi. i n U. v. Hinton et al. (1994) also discussed conventional sound symbolism, which indicated the analogical association of certain phonemes and clusters with certain meanings. The gl- of glitter, glisten, glow and glimmer is a typical example, which suggests light in English. Conventional sound symbolism is called as “phonetic sound symbolism” in Jespersen’s (1922) and Marchand’s (1969) studies and “phonesthesia” in Fordyce’s (1988) and Lu’s (1998). Bloomfield (1933) administered an examination of this sort of sound symbols in English and proposed 17 conventional sound symbols, such as gl- and fl-. The former signifies “unmoving light” as in the words glitter, 15.

(31) glisten and glow; the latter connotes “moving light” as in the words flash, flare and flame. Related research about this category of sound symbolism abounded in literature. In terms of vowels, because the vowel is the nucleus of a syllable, it is thought of as symbolic. According to Householder (1946), among the 266 standard English monosyllables and 400 monosyllables from dialect English which were examined in his research, 75% were conventionally symbolic. Take the sound /Λ/ for example, it is suggestive of “adverse judgment, disapproval, dislike, contempt, disgust, etc.” or. 政 治 大 short and roundish” (p.83). With regard to consonants, Marchand (1969) found that /t/ 立. refers to “something cut off or broken off” or “a projection, a protuberance, often. is related to verbs of movement, denoting sound produced by a smart stroke against a. ‧ 國. 學. body. In addition, the initial /sl/ sound expresses falling or sliding movement like slide.. ‧. Another possibility is the denotation of a falling blow like slaughter or slimy, slushy. y. Nat. matter like slime. The initial /sw/ means sway or swing like sweep. Also, /skw/. er. io. sit. introduces words expressive of discordantly eruptive sound, like squeal or implying violent or distorted movement. Hinton et al. (1994) suggested that in comparison with. al. n. v i n onomatopoeias, this category ofC sound symbolism hasU h e n g c h i the greatest degree of separation between sound and meaning.. Conventional sound symbolism is greatly distinct from the other three categories in that different languages select different phonemes to represent a specific meaning. For instance, the gl- case mentioned earlier connotes “light” in English, but it may not be true in other languages. In addition, conventional sound symbolism was questioned due to the fact that there are numerous counterexamples found in English; not to mention the fact that, for example, the meanings of slam, slap and slop were given from the latter parts of the words, -am, -ap and -op, instead of the /sl/ sound. In response to this query, Samuels (1972) provided an explanation: 16.

(32) If a phoneme fits the meaning of the word in which it occurs, it reinforces the meaning, but if it does not fit the meaning, then their occurrence in that context is of the common arbitrary type, and no question of correlation arises. (p.46) As for the source of this type of sound symbolism, Bloomfield (1895) proposed a perspective that as long as a word is semantically expressive, it may establish a link between its meaning and any of its sounds, and then “send forth this sound ( or sounds) upon predatory expeditions into domains where the sound is at first a stranger and parasite” (p.409-410). Thus, the meaning of the word is arbitrarily decided by any. 政 治 大 accidentally in a language; hence it is arbitrary. After the sound is associated with a 立 sound-element contained in it. In other words, at first sound symbolism happened. specific meaning and accepted by the language users, new words are created by this. ‧ 國. 學. principle — using the same or similar sound to coin the new word to meet the need of. io. sit. Research on Sound Symbolism. er. Nat. y. ‧. that specific meaning.. Although the concept of sound symbolism is not new, research on this topic has. al. n. v i n C h symbolism in English been intermittent. Research on sound can be traced back to engchi U Sapir (1929). As mentioned earlier, he invented word pairs with C-V-C syllable. structure (e.g. mal and mil) and offered the participants arbitrarily selected meanings to match with these words. For instance, the participants were asked to identify which word they thought represented a small or large table. His findings showed that the participants felt the vowel /a/ was suggestive of greater magnitude than the vowel /i/ for the participants in his experiment more frequently matched the invented word mil to the meaning of the small table and mal to the large table. Based on a series of psycholinguistic experiments, Sapir found a strong relationship between English vowels and word meanings that vowels and their associations with magnitude 17.

(33) correspond with the natural parameters of the vocal tract during the articulation. In other words, the fact that the vowel /a/ is uttered with an open and expanded vocal cavity appears to designate greater magnitude than the vowel /i/, which is pronounced with a relatively smaller and constricted vocal tract. This classical experiment was replicated by the follow-up research (Newman, 1933; Tarte & Barrit, 1971; Ultan, 1978) and the findings conformed to Sapir’s. Ultan (1978) examined the diminutive marking in 136 languages in his research and found that smallness was signified by a high front vowel like /i/. Thus, Ultan extended Sapir’s finding from English to. 政 治 大 1994; Mok, 2001) also indicated that the phenomenon of sound symbolism is 立. numerous other languages. Other research findings (Ciccotosto, 1991; Hinton et al.,. universal.. ‧ 國. 學. Considerable amount of research (Hinton et al., 1994; Tarte & Barrit, 1971;. ‧. Ultan, 1978) has confirmed the existence of the phenomenon. In short, cross-linguistic. y. Nat. as well as language specific research on sound symbolism has presented an. er. io. sit. accumulation of evidence, indicating that sound symbolism is more than just an exception to the rule that the connection between sound and meaning is arbitrary. al. n. v i n C hno exhaustive lists U (Hinton et al., 1994.). As there are of English sound symbols so far, engchi it is hard to determine the extent to which sound symbolism will affect word learning in English. Despite this, Parault and Schwanenflugel (2006) estimated the effect of sound symbolism in English. Their findings showed that 24% of English words examined in their research were sound symbolic in nature and they concluded that sound symbolism could be an important factor in word learning. Resulting from this conclusion, Parault and Parkinson (2008) suggested that although these sound symbols will not always lead to the correct definition for an unknown word, “when faced with innumerable possible meanings for a word, a strategy that works even just 24% of the time is better than no strategy at all”(p.669). 18.

(34) Sound Symbolism and English Vocabulary Teaching In literature, related research concerning sound symbolism has been focused on two dimensions: the exploration of sound symbolism to prove the psychological reality and the search for universality of the phenomenon among the world languages. Numerous experiments (Ciccotosto, 1991; Hinton et al., 1994; Sapir, 1929; Tarte & Barrit, 1971; Ultan, 1978) were conducted and have proved that sound symbolism is a universal phenomenon. Not until recent years, was the theory of sound symbolism incorporated into. 政 治 大 sound symbolism to vocabulary learning (Berko-Gleason, 2005; Yashida, 2003), and 立 vocabulary teaching from the viewpoint of phonetics. Some research has applied. suggested that it is easier for children to learn sound-symbolic words because the. ‧ 國. 學. connection between sound and meaning is obvious, as in the example of. ‧. onomatopoeias. As a result, sound symbolism plays a role in word learning.. y. Nat. Nonetheless, within the EFL framework, the present study only focuses on literature. er. io. sit. related to English sound symbolism. Parault and Schwanenflugel’s (2006) research compared the correctness of word meanings English-speaking adults inferred from. al. n. v i n Cand obsolete English sound symbolic symbolic words. Their finding U h enon-sound i h ngc. showed that the participants were 85% better at generating correct meanings of sound symbolic versus non-sound symbolic words. Parault’s (2006) follow-up study confirmed the finding and indicated that sound symbols were useful for learning new words. In a recent study, Parault and Parkinson (2008) concluded that sound symbolism is a word property which influences the learning of unknown words. To date, however, few studies have combined sound symbolism theory with English classroom vocabulary teaching. Chen’s (2000) research discussed the relationship between sound and meaning of English words from the perspective of articulatory phonetics and acoustic phonetics. Afterwards, Mo (2005) systematically introduced 19.

(35) the relationship between English sounds and vocabulary teaching with the theory of sound symbolism. These studies are the initial step toward the combination of theory and practice. In addition to the theories of sound symbolism, several researchers further provided some useful pedagogical implications from sound symbolism in literature. Mo (2005) believes that sound symbolism and sound switching are predictable. If an English teacher understands the phenomena and the related theories, she will be able to facilitate students’ mental activities during the vocabulary instruction. Other. 政 治 大 reinforces phonics instruction; (2) sound symbolism instruction corresponds to 立. pedagogical implications were described as follows. (1) Sound symbolism instruction. cognitive learning principles; (3) sound symbolism assists the training of phonological. ‧ 國. 學. awareness; and (4) sound symbolism instruction is complementary to other. ‧. vocabulary teaching approaches (Chen, 2000). Furthermore, Parault and Parkinson. y. Nat. (2008) argued that the contribution to education sound symbolism made was to help. er. io. sit. students narrow down the possible meanings for unknown words.. Previous studies on sound symbolism showed the connection between the theory. al. n. v i n Cinstruction and the application to vocabulary Table 2.1). However, there is an U h e n g(See i h c absence of empirical research to confirm the effectiveness of incorporating sound. symbolism into English vocabulary teaching. The present study attempts to fill this gap by designing an experimental research to investigate the effect of the instruction of sound symbolism in the English teaching classroom and the target words designed in this present study included the last two categories of sound symbolism reviewed in this chapter, i.e. synesthetic and conventional sound symbolism.. 20.

(36) Table 2.1 Related Studies on Sound Symbolism. Previous studies. Language English. Sapir (1929); Tarte &. Focus. Others. Existence. . Barrit (1971). Vocabulary. Empirical. Teaching. Study. . Ultan (1978);. . Ciccotosto (1991);. . . Hinton et al. (1994) Chen (2000);. . Mo (2005); Parault &. 立. Parkinson (2008) Mok (2001). 政 治 大. . Schwanenflugel. . . io. sit. y. Nat. (2006). . n. al. er. Parault &. . ‧. ‧ 國. Yashida (2003). . 學. . . Ch. engchi. 21. i n U. v.

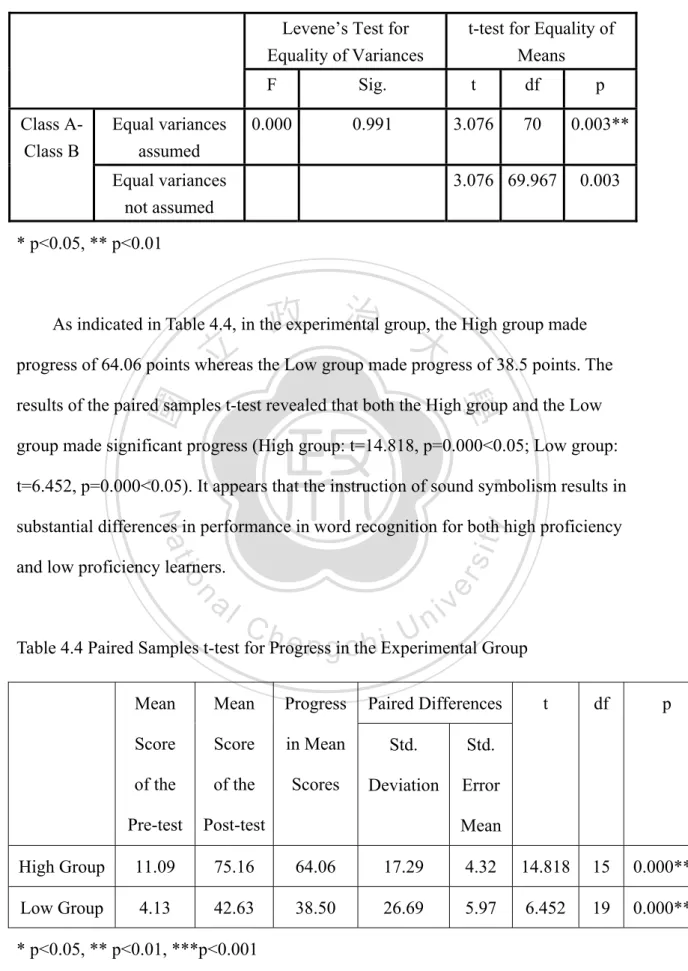

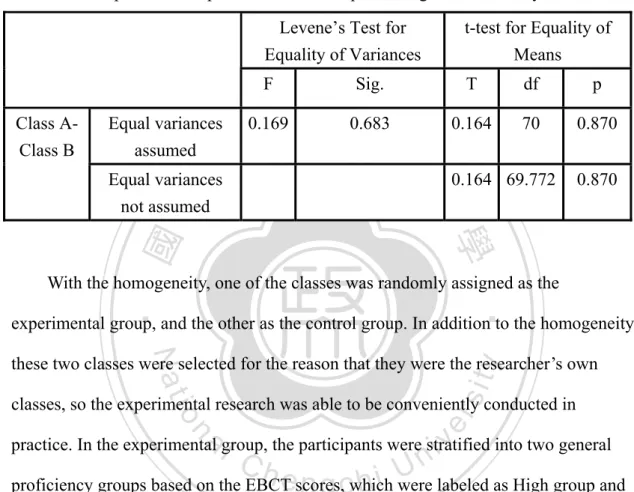

(37) CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY This empirical study aims to investigate the effectiveness of sound symbolism instruction in vocabulary teaching. This chapter describes the methodology of the research, including participants of the present research, instruments employed by the researcher/teacher5, vocabulary instruction, procedure throughout the study and data analysis of the present research.. Participants 政 治 大 The participants for the study consisted of two ninth-grade classes of 72 students 立. at a public junior high school in Hsin-chu City. They were chosen because they could. ‧ 國. 學. be considered homogeneous for two reasons. First, all ninth-graders at this school had. ‧. been placed in a normal s-type distribution on the basis of their performance in an. y. Nat. entrance IQ test. Second, all of the participants were of similar English proficiency.. er. io. sit. The participants were given the 2009 2nd English Test of the Basic Competence Test (EBCT) to ensure they were homogeneous in English proficiency. Their scores on. al. n. v i n C hthrough the independent EBCT were collected and compared samples t-test. As shown engchi U in Table 3.1, the mean score of Class A was 37.25 (N=36) with a standard deviation of 19.53, and that of Class B was 38.03 (N=36) with a standard deviation of 20.686. According to the statistics in Table 3.2, these two classes passed the Levene’s test (F=0.169, p=0.683>0.05), indicating that the two classes were homogeneous. The t-test for equality of means also showed that there was no significant difference between the two classes (t=0.164, p=0.87>0.05).. 5 6. In this study, the researcher is also the teacher of the experimental group and the control group. The total score of EBCT is 80 points. 22.

(38) Table 3.1 Statistics of Participants’ English Proficiency Test Scores Group. Number. Mean. S.D.. Class A. 36. 37.25. 19.53. Class B. 36. 38.03. 20.68. Table 3.2 Independent Samples t-test on Participants’ English Proficiency Test. Class AClass B. Equal variances assumed Equal variances not assumed. 立. Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances. t-test for Equality of Means. F. Sig.. T. df. p. 0.169. 0.683. 0.164. 70. 0.870. 政 治 大. 0.164 69.772. 0.870. ‧ 國. 學. With the homogeneity, one of the classes was randomly assigned as the. ‧. experimental group, and the other as the control group. In addition to the homogeneity,. Nat. sit. y. these two classes were selected for the reason that they were the researcher’s own. n. al. er. io. classes, so the experimental research was able to be conveniently conducted in. i n U. v. practice. In the experimental group, the participants were stratified into two general. Ch. engchi. proficiency groups based on the EBCT scores, which were labeled as High group and Low group. The cut-off point was the mean of all the participants’ EBCT scores (M=37.25). The High group included students with scores of 38 and above and the Low group with EBCT scores of 37.25 and below. The numbers of the participants in High and Low proficiency groups were 16 and 20 respectively.. Instruments The instruments designed in this study included the 2009 2nd EBCT (See Appendix A), a test for word selection (See Appendix B), a vocabulary pre- and 23.

(39) post-test (See Appendix C), the modified think-aloud protocols sheet (See Appendix D), and interviews (See Appendix E).. The 2009 2nd English Test of the Basic Competence Test (EBCT) The 2009 2nd EBCT (See Appendix A) was administered to ensure that initially the two groups had the same level of general English proficiency and to distinguish the participants with high English proficiency from those with low English proficiency. The participants’ scores were collected and compared through the. 政 治 大 the means of the two classes on EBCT. In addition, the mean of all the participants’ 立. independent samples t-test to ensure that there was no significant difference between. EBCT scores in the experimental group was the cut-off point to differentiate different. ‧ 國. 學. English proficiency levels.. ‧. The 2009 2nd EBCT was chosen for two reasons. First, it possesses good validity,. y. Nat. reliability and discrimination. Second, the 2nd EBCT had not been practiced by the. n. al. er. io. sit. participants in this study.. i n AC Test for Word Selection hengchi U. v. A test for word selection was designed to ensure that the target words of the study were unknown to all the participants. The 80 target words were decided for the following reason. Normally, the participants are taught ten new words from the textbook each week in a regular English class. The unknown words in this study are an additional load for vocabulary memorization for the participants. Therefore, only half of the number, i.e. 5, was added to the normal vocabulary instruction per week. As the instruction lasted for sixteen weeks, the number of the target words was eighty. These 80 words were chosen to meet two criteria: the unknown words both on. 24.

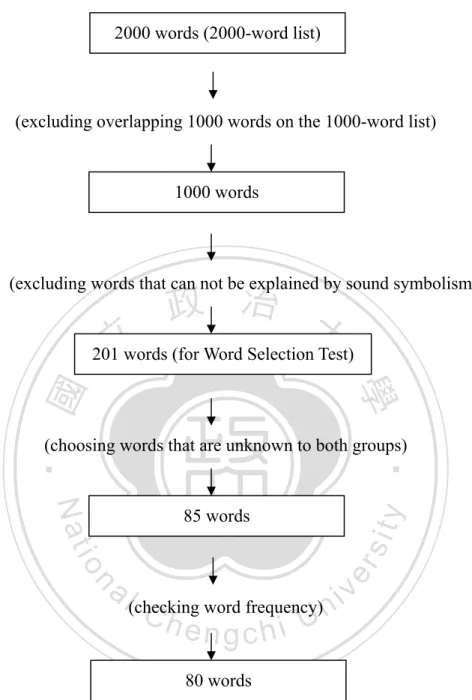

(40) the 2000-word list7 stipulated by Ministry of Education (2009) and within the scope of sound symbolism. The target words were chosen by the following steps (See Figure 3.1). First, words were selected from the frequency-based 2000-word list, excluding the overlapping words listed on the 1000-word list8. The 1000-word list was not used in that the participants might have learned most of the words on the list. Secondly, the rest 1000 words of the 2000-word list were narrowed down to 201 words according to the scope of sound symbolism; that is, the words that can not be explained by sound symbolism were excluded. The participants including both groups were asked to choose the unknown words9 from the 201 words that meet sound symbolism criteria. 政 治 大 (See Appendix B). Their responses resulted in 85 words that were unfamiliar to both 立 groups. Utilizing British National Corpus10 (BNC), the researcher determined the. ‧ 國. 學. target 80 words by frequency of the word use (See Table 3.3). Finally, the researcher,. ‧. i.e. the teacher of both groups, confirmed these 80 words (See Table 3.4) were. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. unknown to the participants in the current study.. Ch. engchi. 7. i n U. v. The list is from: http://www.edu.tw/eje/index.aspx/content.aspx?site_content_sn=4420. The list was also stipulated by Ministry of Education (2003): http://www.edu.tw/eje/index.aspx/content.aspx?site_content_sn=4420. 9 This word selection method of target vocabulary on the basis of related research (Kim, 2008; Rott, 2005; Wesche & Paribakht, 1996) was modified for use in the present study. 10 British National Corpus possesses a 100 million word collection of samples of written and spoken language from a wide range of sources. 8. 25.

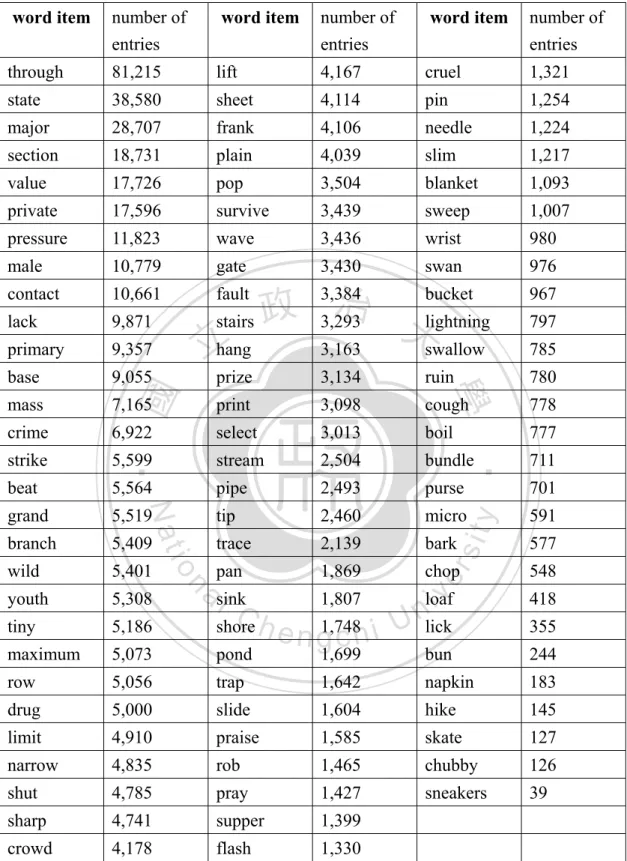

(41) Figure 3.1 The Procedure of Word Selection. 2000 words (2000-word list). (excluding overlapping 1000 words on the 1000-word list). 1000 words. (excluding words that can not be explained by sound symbolism). 立. 政 治 大. 201 words (for Word Selection Test). ‧ 國. 學 ‧. (choosing words that are unknown to both groups). Nat. n. sit er. io. al. y. 85 words. Ch. i n U. (checking word frequency). engchi 80 words. 26. v.

(42) Table 3.3 Word Frequency from BNC of 85 Words Selected word item. number of entries. word item. number of entries. word item. number of entries. through. 81,215. lift. 4,167. cruel. 1,321. state. 38,580. sheet. 4,114. pin. 1,254. major. 28,707. frank. 4,106. needle. 1,224. section. 18,731. plain. 4,039. slim. 1,217. value. 17,726. pop. 3,504. blanket. 1,093. private. 17,596. survive. 3,439. sweep. 1,007. pressure. 11,823. wave. 3,436. wrist. 980. male. 10,779. gate. 3,430. swan. 976. contact. 10,661. lack. 9,871. primary. 9,357. base. 9,055. mass. 3,384 bucket 治 政 stairs 3,293 大lightning 3,163 swallow 立hang. 967 797. ruin. 780. 7,165. print. 3,098. cough. 778. crime. 6,922. select. 3,013. boil. 777. strike. 5,599. stream. 2,504. bundle. beat. 5,564. pipe. 2,493. purse. ‧. 711 701. grand. 5,519. tip. 2,460. micro. 591. branch. 5,409. trace. 2,139. bark. 577. wild. 5,401. pan. chop. 548. youth. 5,308. tiny. 5,186. a sink l C shore h. 1,869. maximum. 5,073. pond. row. 5,056. drug. Nat. io. er. ‧ 國. 3,134. 學. prize. y. 785. sit. fault. 355. 1,699. bun. 244. trap. 1,642. napkin. 183. 5,000. slide. 1,604. hike. 145. limit. 4,910. praise. 1,585. skate. 127. narrow. 4,835. rob. 1,465. chubby. 126. shut. 4,785. pray. 1,427. sneakers. 39. sharp. 4,741. supper. 1,399. crowd. 4,178. flash. 1,330. n. loaf iv n U lick. 1,807. e n g1,748 chi. 27. 418.

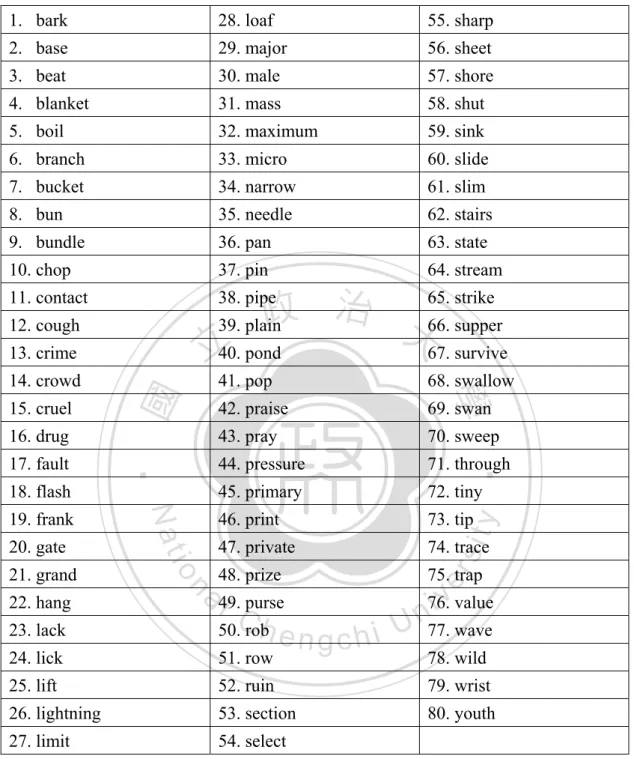

(43) Table 3.4 The 80 Target Words 1. bark. 28. loaf. 55. sharp. 2. base. 29. major. 56. sheet. 3. beat. 30. male. 57. shore. 4. blanket. 31. mass. 58. shut. 5. boil. 32. maximum. 59. sink. 6. branch. 33. micro. 60. slide. 7. bucket. 34. narrow. 61. slim. 8. bun. 35. needle. 62. stairs. 9. bundle. 36. pan. 63. state. 10. chop. 37. pin. 64. stream. 65. strike 治 政 39. plain 大66. supper 67. survive 立40. pond. 11. contact. 38. pipe. 12. cough 13. crime. 68. swallow. 42. praise. 69. swan. 43. pray. 70. sweep. 44. pressure. 71. through. 45. primary. 72. tiny. 46. print. 73. tip. 47. private. 74. trace. 48. prize. 75. trap. 51. row. 78. wild. 25. lift. 52. ruin. 79. wrist. 26. lightning. 53. section. 80. youth. 27. limit. 54. select. 18. flash. Nat. 19. frank 20. gate. io. a l49. purse v value 76. i n Ch 50. rob e n g c h i U 77. wave. n. 21. grand 22. hang 23. lack 24. lick. y. 17. fault. sit. 16. drug. er. 15. cruel. ‧. ‧ 國. 41. pop. 學. 14. crowd. A Pre- and Post-test in Word Recognition in Relation to Meanings The purpose of the pre-test was to ensure that the two groups had homogeneous performance on the target vocabulary initially and the purpose of the post-test was to investigate the effectiveness of sound symbolism instruction. According to the definition of knowing a word presented in Chapter 1, the focus of this study was on 28.

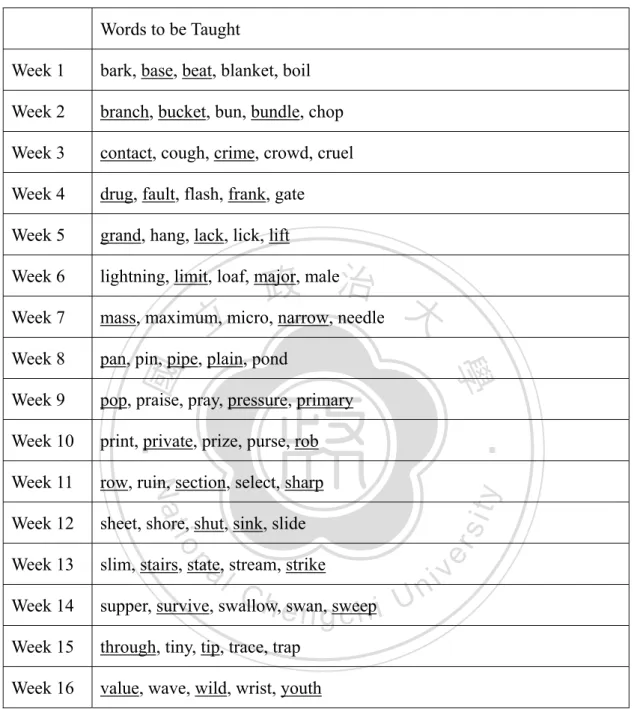

(44) receptive vocabulary knowledge; therefore, the pre- and post-test was designed for word recognition in relation to meaning in the form of a matching test. The format of a matching test was borrowed from Hsu’s (2004) research, which investigated the discrepancy in the use of the iconic-morphological approach via commonly-used roots, the non-iconic morphological approach via commonly-used roots, and the traditional definition-based teaching method in vocabulary memorization in terms of word recognition. Because of the similarity of the nature of the experiments, this study adopted the format of the pre-test in Hsu’s research, i.e. a matching test. Based on. 政 治 大 (See Appendix C). The participants were required to. Hsu’s (2004) research, a self-designed matching test for 40-word recognition was 11. used as the pre- and post-test. 立. select the Chinese translation equivalent of each English vocabulary item.. ‧ 國. 學. The 40 words in the pre- and post-test were chosen from the 80 target words in the. ‧. vocabulary instruction (See Table 3.5). These 40 words selected for the test items. y. sit. io. n. al. er. instruction.. Nat. were averagely distributed across the words taught in the 16-week vocabulary. 11. Ch. engchi. Cronbach’s Alpha value=0.968 29. i n U. v.

(45) Table 3.5 The Target Words & The Test Items. Words to be Taught Week 1. bark, base, beat, blanket, boil. Week 2. branch, bucket, bun, bundle, chop. Week 3. contact, cough, crime, crowd, cruel. Week 4. drug, fault, flash, frank, gate. Week 5. grand, hang, lack, lick, lift. Week 6. lightning, limit, loaf, major, male. Week 9. pop, praise, pray, pressure, primary. Week 10. print, private, prize, purse, rob. Week 11. row, ruin, section, select, sharp. Week 12. sheet, shore, shut, sink, slide. Week 13. slim, stairs, state, stream, strike. Week 14. supper, survive, swallow, swan, sweep. Week 15. through, tiny, tip, trace, trap. Week 16. value, wave, wild, wrist, youth. ‧. ‧ 國. pan, pin, pipe, plain, pond. 學. Week 8. sit. io. n. Ch. y. Nat. al. engchi. er. Week 7. 政 治 大 mass, maximum, micro, narrow, needle 立. i n U. v. Note: The underlined words are the test items in the pre- and post-test.. Think-aloud Method To find out whether a participant had learned the word successfully, a single matching test was not enough, since the correct response might be given by chance (Hughes, 2003). A think-aloud procedure was, therefore, added to the post-test to. 30.

(46) minimize the chance of random correct responses in the post-test. In other words, if a participant gives right answers in both parts for the same vocabulary item, the researcher will presume the student has successfully learned the word. The think-aloud procedure in the present study adapted Yang’s (2005) method, which applied a think-aloud method to English vocabulary instruction in junior high school. Yang’s (2005) research explored EFL lexical inferencing abilities and reading behaviors of junior high school students in Taiwan by the use of Thinking Aloud Problem Solving (TAPS) and instruction of Word-solving Strategies. In TAPS, the. 政 治 大 discussion. Meanwhile, a concurrent recording of their TAPS procedure was 立. participants were paired up and required to speak out their thinking process in the. conducted. This study borrowed and adapted her method to investigate the. ‧ 國. 學. participants’ invisible thinking process. In the current study the procedure was a. ‧. shorter and simplified task to meet the nature of the experiment. The participants in. y. Nat. both the experimental group and the control group were required to jot down their. er. io. sit. thinking process for each vocabulary item when they were recalling the Chinese meaning of an English equivalent (See Appendix D). For example, given the. al. n. v i n C hmight write downUthe thinking process vocabulary item “ban,” a participant engchi. 12. , such as. “feeling the obstruction to airstream in the oral cavity while pronouncing the letter b” when she is recalling the meaning of the word. By checking the thinking process, the researcher was able to know how the participant memorized an English vocabulary item. Before the think-aloud task, the researcher designed a training session to instruct the participants how to conduct the think-aloud method in this study. The training session was administered in two steps: (1) the researcher’s modeling of the writing of. 12. In this procedure, participants were allowed to write down their thinking process in their native language; that is, Chinese in this study. 31.

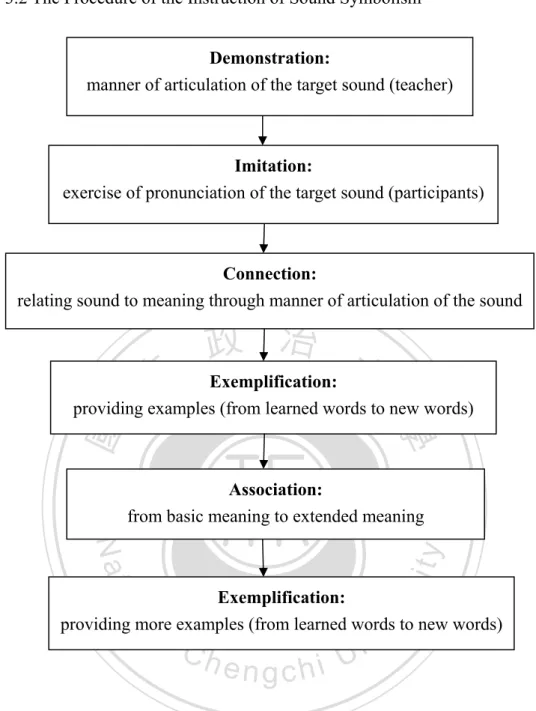

(47) thinking process with elaboration and explanation, and (2) the participants’ practices of the writing of thinking process with a model sheet (Yang, 2005). In the researcher’s modeling process, the participants were instructed how to write down their thinking process of vocabulary memorization by using sound symbolism13. In the participants’ practicing process, the model sheet finished in the pilot study was demonstrated to help them get the gist of the method. The training session lasted for one period. Then the post-test and think-aloud task followed.. Interviews 政 治 大 Following the post-test and the think-aloud task, oral interviews were conducted 立. in the experimental group to find out (1) what the participants’ views on the. ‧ 國. 學. instruction of sound symbolism were, (2) what effect the instruction of sound. ‧. symbolism had on the participants, and (3) how to improve the instruction of sound. y. Nat. symbolism. This study used semi-structured interviews. Specific questions determined. er. io. sit. beforehand were provided (See Appendix E) but elaboration in the questions and answers was allowed. Ten volunteer participants, composed of equal number of high. n. al. 14. and low proficiency students. v i n C from the experimentalU h e n g c h i group were interviewed. The. interview questions were designed on the basis of Chen’s (2000) research, consisting two parts: ways to memorize new words and views on the instruction of sound symbolism.. Vocabulary Instruction Two different kinds of vocabulary instruction were employed for 16 weeks. The experimental group received sound symbolism instruction, while the control group 13. To avoid the guidance effect, the words which would not be used as the test items were provided as the examples in the researcher’s modeling process. 14 Five high proficiency students and five low proficiency students were included. 32.

數據

Outline

相關文件

Centre for Learning Sciences and Technologies (CLST) The Chinese University of Hong Kong..

Microphone and 600 ohm line conduits shall be mechanically and electrically connected to receptacle boxes and electrically grounded to the audio system ground point.. Lines in

Therefore, this study is focusing on designing the bicycle traffic safety Lesson Plan to enhance the bicycle riding safety of students.. Through the pre-teaching test and the

This study intends to bridge this gap by developing models that can demonstrate and describe the mechanism of knowledge creation activities from the perspective of

The purpose of this research is to explore the important and satisfaction analysis of experiential marketing in traditional bakery industry by using Importance-Performance and

This study aimed to explore the effectiveness of the classroom management of the homeroom teacher by analyzing the process of the formation of the classroom management and

Investigating the effect of learning method and motivation on learning performance in a business simulation system context: An experimental study. Four steps to

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intentions based on theory of planned behavior and also determine the moderating