行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

語言社會化:漢語親子對話中的情意表達

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC94-2411-H-004-036- 執行期間: 94 年 08 月 01 日至 95 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立政治大學語言學研究所 計畫主持人: 黃瓊之 報告類型: 精簡報告 報告附件: 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢Language Socialization of Affect in Mandarin Parent-child Conversation

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate language socialization of affect in Mandarin parent-child interaction. Natural conversations between Mandarin-speaking two-year-olds and their parents were analyzed, focusing on the lexicon of affect words and the conversational structures in which these words were used. The results showed that the children tended to use affect words to encode specific affective states, and the primary experiencers of these affective states were the children. The parents tended to use affect words to negotiate with the children the appropriate affective responses to a variety of stimuli, or the parents may use affect words to socialize the children’s behaviors into culturally approved patterns. In addition, it was found that the structure of conversational sequences served as a discourse-level resource for affect socialization. The data were further examined in relation to Clancy’s (1999) model of language socialization of affect, and showed that the children experienced the socializing potential of language in three ways: (1) through modeling, (2) through direct instruction, and (3) through negotiation.

1. Introduction

Research on human emotions has received much attention in the disciplines of psychology, anthropology and linguistics. In the area of child language acquisition, the development of ‘emotion talk’ also deserves attention. In order to become communicatively competent, it is important for language-learning children to learn how to express and talk about feelings in appropriate ways, and to recognize others’ moods and emotions (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986).

Previous studies have raised the controversial question of the role of nature vs. nurture in the development of human emotions. Hochschild (1979) contrasts two models of emotional development: the biological model and the socialization model. In the first model, emotion is related to biologically given instincts or impulses. In this view, emotions are regarded as organismic functions and are fixed or universal phenomena. In the second model, emotions are viewed as subject to socialization influence. As suggested by Hochschild (1979), ‘we do feel, we try to feel, and we want to try to feel (p.563).’

Previous studies of emotions, however, have focused mostly on the measurement and development of emotional behavior, such as infants’ facial expressions and the relationship of emotional expressions to particular situations (e.g., Izard, 1977; Malatesta & Haviland, 1982; Ortony et al., 1988; Scherer, 1982). The perspectives these studies adopted were derived mainly from the biological model. The ways in which emotions are socialized, however, have been less researched. In other words, we have little knowledge about how socialization shapes children’s emotion experience and emotion expression.

Thus the purpose of study was to investigate the socialization of affect in Mandarin parent-child interaction. Following Ochs & Schieffelin (1989) and Clancy

in the socialization process.

2. Methods

The participants of this study were two Mandarin-speaking two-year-olds and their parents. The children were visited in their homes. Natural parent-child conversations were audio- and video- taped. The data analyzed in this study included four hours of recording from each parent-child dyad.

Following Clancy (1999), affect words in the speech of the parents and the children were classified into the following five types:

1. Predicates that encode a specific affective state and can take an experiencer as subject (e.g., gaoxing ‘be glad’ ).

2. Predicates that describe a referent in terms of the affect it evokes (e.g.,

youqu ‘interesting).

3. Words having clear positive/negative valence (e.g., hao ‘good), including evaluative characterizations of people and their actions (e.g., yonggan ‘brave’) and descriptions of physical properties or sensory perceptions with affective connotations (e.g., haochi ‘delicious’).

4. Predicates referring to actions with affective motivations (e.g., ku ‘cry’) and physical events or states with predictable positive or negative affective consequences (e.g., shoushang ‘get hurt’).

5. Formulaic expressions of gratitude, apology, and regret (e.g., xiexie ‘thank you’).

3. Results

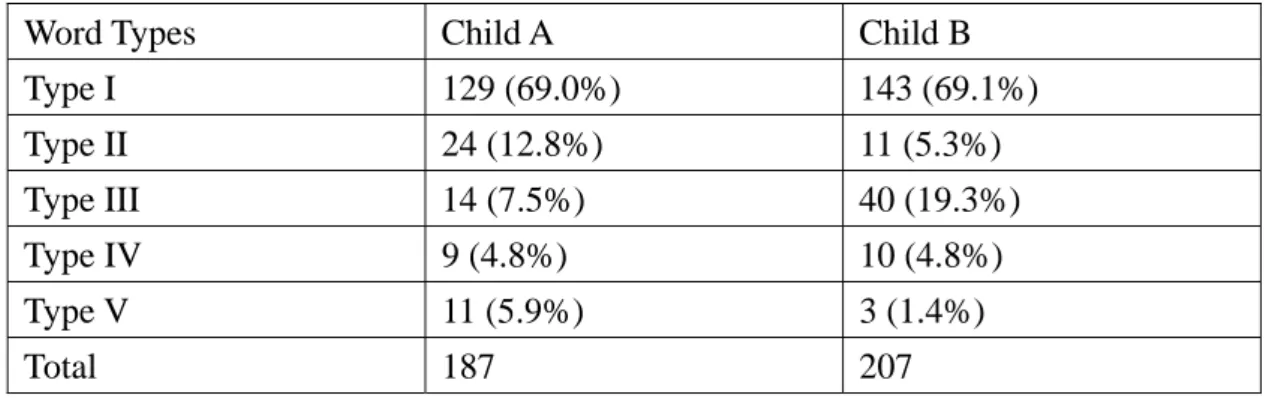

Table 1: The types of affect words in the children’s speech

Word Types Child A Child B

Type I 129 (69.0%) 143 (69.1%) Type II 24 (12.8%) 11 (5.3%) Type III 14 (7.5%) 40 (19.3%) Type IV 9 (4.8%) 10 (4.8%) Type V 11 (5.9%) 3 (1.4%) Total 187 207

As seen in Table 1, most of the children’s affect words belonged to Type I. In other words, the children tended to use affect words to encode specific affective states, which was consistent with previous studies of Japanese-speaking children (Clancy, 1999) and English-speaking children (Brown & Dunn, 1991; Wellman et al., 1995). In addition, in these cases the primary experiencers of the affective states were the children themselves.

Example 1 shows how the child used a positive affect word ‘xihuan’ (‘like’) to encode his own affective state.

Example 1 (P: Parent; C: Child)

P: lai # Ron.

‘Come here, Ron.’

P: zhe shi nide [= handing Ron a doll]. ‘This is yours.’

P: zhe shi Daniel [%English], dui budui? ‘This is Daniel, right?’

C: xihuan ni [=holding the doll]. Å ‘(I) like you.’

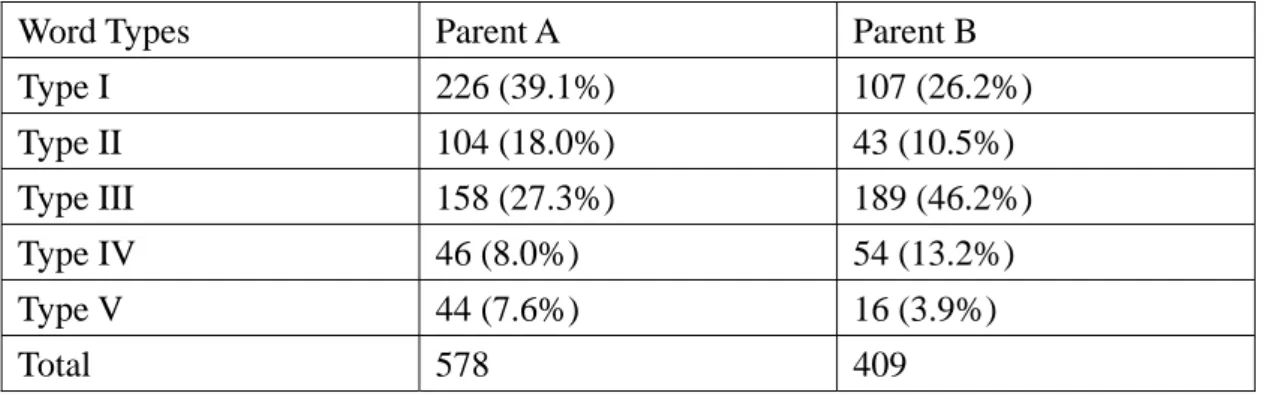

As for the parents’ affect words, Table 2 shows the types of affect words used in the parents’ speech. As seen in the table, the distributions of the parents’ affect words displayed different patterns from the distributions of the children’s. While both children tended to use Type I affect words, the parents’ affect words belonged mostly to Type I and Type III.

affect to the children, or to confirm, accept or reject the children’s states of affect. These affect words were thus used by the parents to negotiate with the children the appropriate affective responses to a variety of stimuli. Example 2 shows how the parent rejected the child’s state of affect.

Example 2 P: eryu. ‘Alligator’ C: hao kepa o. ‘(It’s) scary.’ P: hao kepa. ‘(It’s) scary.’ P: weisheme? ‘Why?’ P: bu pa [/] bu pa [/] bu pa. Å

‘Don’t be afraid. Don’t be afraid. Don’t be afraid.’ C: mama zai zheli.

‘Mommy is here.’ P: dui.

‘Yes.’

The parents also frequently resorted to Type III words. These affect words were mainly evaluative expressions which characterized the children or their actions, as shown in Example 3 and Example 4.

Example 3

(The child was arranging some magnets on a board)

P: o -: fangde dui ya.

‘Oh, you arrange them in a right way.’ P: hen bang a. Å

‘(You’re) excellent.‘

Example 4

P: zheyang weixian. Å ‘This is dangerous.’

P: ni hui diedao. ‘You will fall down.’

The parents’ Type III words also occurred in book-reading or pretend play contexts, in which the parents expressed affect through evaluating the characters or their actions in the storybooks or pretend plays, as seen in Example 5.

Example 5

P: tamen yao gai fangzi o. ‘They want to build a house.’ P: keshi you shei a?

‘But who is there?’ C: huai yelang. ‘Bad wolf’

P: huai yelang lai le o. Å ‘The bad wolf has come.’

Thus it appeared that the parents used these Type III evaluative expressions to directly or indirectly socialize the children’s behaviors into culturally approved patterns.

In addition to the affect lexicon, it was found that the structure of conversational sequences served as a discourse-level resource for affect socialization. Some common conversational sequences observed in the data included question—answer—acknowledgement, query—confirmation, assertion—agreement

Affect talk is a crucial vehicle for the socialization of affect. The expression of affect is culture- and language- specific. As a result, acquisition of an affect lexicon is itself a socialization process to culture-specific ways of organizing emotional experience.

References

Brown, J. R. & Dunn, J. (1991). ‘You can cry, mum’: The social and developmental implications of talk about internal states. British Journal of Developmental

Psychology, 9, 237-256.

Clancy, P. M. (1999). The socialization of affect in Japanese mother-child conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 31, 1397-1421.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American

Journal of Sociology, 85, 551-575.

Irvin, J. T. (1982). Language and affect: Some cross-cultural issues. In Burns, H. (ed.),

Contemporary perceptions of language: Inter-disciplinary dimensions.

Georgetown round table on language and linguistics, 31-47. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Izard, C. E., (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum.

Lewis, M. & Michalson, L. (1982). The socialization of emotion. In Field, T. & Fogel, A. (eds.), Emotion and early interaction, 189-212. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Malatesta, C. & Haviland, J. M. (1982). Learning display rules: The socialization of

emotion expression in infancy. Child Development, 53, 991-1003. Ochs, E. & Schieffelin, B. B. (1989). Language has a heart. Text, 9, 7-25.

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L. & Collins, A. (1988). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schieffelin, B. B. & Ochs, E. (1986). Language socialization. Annual Review of

Anthropology, 15, 163-191.

Scherer, K. R. (1982). The assessment of vocal expression in infants and children. In Izard, C. E. (ed.), Measuring emotions in infants and children. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wellman, H. M., Harris, P. L., Banerjee, M. & Sinclair, A. (1995). Early understanding of emotion: Evidence from natural language. Cognitoin, 9, 117-149.