國立臺灣大學理學院心理學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Psychology College of Science

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

華人母親之親子共讀行為與學齡前孩童之 閱讀興趣及共讀參與度

Chinese Mothers’ Joint-Reading Behaviors and Preschoolers’ Reading Interest and

Joint-Reading Engagement

吳淑娟 Shu-Chuan Wu

指導教授: 雷庚玲 博士 Advisor: Keng-Ling Lay, Ph.D.

中華民國 101 年 06 月

June, 2012

i

致 謝

四年,在人生的旅程中,是否值得書寫出一點心得,端看這期間刻畫了些甚

麼可豐富人生的痕跡。這些年來各縣市許多教育文化單位和學校絡繹不絕的舉辦

推廣親子共讀的活動,很幸運的我也參與其中。然而我這樣一個教育文化界的門

外漢,單憑著自己對閱讀的喜愛,和從孩子出生後就以書本為互動媒介所獲得的

實際經驗,以及和家長們頻繁互動的心得,總覺得國內推廣親子共讀的熱絡中,

似乎可以再加入某個元素,讓孩子們對於共讀的過程能有更美好的經驗,讓孩子

們長大仍欣喜於閱讀的樂趣。這個元素,似乎從這份論文可以看到一點端倪,也

不枉這四年的辛苦! 這四年,來往於台北與羅東,學校與醫院,挑燈讀著一篇又

一篇的論文文獻,熬夜寫著一份又一份的作業,經常連出門旅遊,背包裡一定帶

著筆電,就是想將零碎的時間拿來多讀點資料。讀著讀著,眼前經常浮現出過往

與孩子們和家長們接觸的情景,許多的理論都可以轉化為臨床上的衛教,這些就

夠豐富過往這四年的歲月!

要感謝的人太多。感謝雷老師,能有機會向您學習如何有系統的觀察親子互

動,如何將理論架構釐清,如何將思考清楚呈現,是我當初沒有料想到的收穫,

而這份收穫將讓我日後臨床上的觀察能更為犀利!希望不會再有學生讓您要陪著

熬夜改論文,感謝萬份! 感謝曹峰銘老師,四年前因您的推薦,讓我能有機會再

度踏入學術的殿堂,研讀深奧但有趣的兒童發展相關理論! 感謝呂鴻基教授的支

持,您對學術研究孜孜不倦的精神,也是激勵我再度進修的動力之一; 感謝口試

ii

委員張鑑如老師及周育如老師,因您們的指點,讓我對親子共讀有更寬廣的認

知;感謝同樣是熟女的素英,如菲和韻如,雖然知道妳們有許多可讓我功力增強

的學識經驗,可惜我總是來去匆匆,不過以後一定還有需要妳們的機會,請繼續

多幫忙! 感謝泰銓、均后,還有先前一同修課的怡欣、加恩的支持和幫忙! 還要

感謝經常鼓勵我的各方好友,以及參與研究的家長和孩子們! 同時也感謝兒科的

同仁,因為我的缺席,讓大家工作更為辛苦,感謝各位的體恤! 以上,感謝萬分!

然而,若不是有劉醫師,我的先生,的支持,我滿腦的想法將無法有機會實

現。感謝你鼓勵我進修,而且在我忙於功課,又忙於閱讀活動時,總是無怨的幫

忙帶孩子做家事,即使你的工作不是普通的忙碌,而你自己也還在進修,但因為

有你,讓我成就了不可能的事,感謝有你!

最後,我親愛的安安小朋友,即便我的工作原本就是和孩子相處,但若不是

因為你,讓我感受到當媽媽的樂趣,我也不會有這份願景,希望每個孩子都能有

機會窩在媽媽的懷裡,享受聽媽媽說故事的幸福感覺。雖然這些年來,許多原本

應該陪你的時間,都被我的工作、功課和活動占去了,還好媽咪的晚安故事仍經

常維持著,看著你聽完媽咪念故事書然後心滿意足沉睡的模樣,那就是我當媽媽

的幸福所在。 這份幸福的感覺,也希望許多親子們都能享受到!

iii

摘 要

西方研究顯示,親子共讀時的社會情緒互動與父母的共讀技巧皆可預測孩童

的閱讀動機,而閱讀動機與日後的讀寫能力及學業成就有關。華人父母原即十分

注重子女的學業成就,然親子共讀並非傳統華人家庭慣常之互動方式。本研究之

目的即在觀察華人母親在親子共讀時所顯示的社會情緒互動行為和共讀技巧,並

探討其對孩童閱讀動機的預測力。為能在臨床上給予家長適性之共讀建議,本研

究並檢驗孩童性別及母親教育程度如何調節母親共讀行為與閱讀動機之關係。本

研究並自行發展觀察登錄系統,以捕捉在重視學業之文化思維下的台灣母親的親

子共讀行為。共有 51 對母親與其 50 至 60 個月大(M = 55.22)的學齡前孩童完

成相隔一至二週的兩次 10 分鐘的共讀活動錄影,再以時間取樣法登錄母親行

為。觀察系統共分兩大向度,並將「社會情緒表達」向度再分成以孩童為中心的

行為、以父母為中心的行為兩個次向度;也將「認知與語言教導」向度再分成教

導、闡述、封閉性問題,以及開放性問題四個次向度。以母親評量的孩童日常閱

讀興趣及觀察者評量之孩童在共讀當時的參與度為結果變項之階層迴歸分析顯

示:(1)以孩童為中心的行為可正向預測孩童共讀時的參與度,但無法預測孩童

的閱讀興趣;以父母為中心的行為則可負向預測孩童的閱讀興趣和參與度。(2)

母親之封閉性問題,對孩童的閱讀興趣有負向預測力。(3)女孩比男孩有較高的

閱讀興趣,但孩童性別無法預測共讀參與度。(4)母親的教育程度可調節以父母

為中心的行為以及闡述行為對孩童共讀參與度的預測效果。(5)母親的教育程度

亦可調節以孩童為中心的行為對孩童閱讀興趣的預測力。藉由本研究所發展之父

iv

母共讀行為登錄系統,顯示華人母親的教導行為對閱讀動機沒有顯著影響,但其

在親子共讀時以自我為中心的社會情緒表達,如批評、要求速度、不回應等,在

兒童的日常閱讀興趣上扮演了負向的角色。以孩童為中心的共讀行為則對母親教

育程度較低的孩童之閱讀興趣有正向作用。

關鍵字: 親子共讀、華人親職教養、以兒童為中心的行為、以父母為中心的行為、

母親閱讀行為、閱讀動機

v

Chinese Mothers’ Joint-Reading Behaviors and

Preschoolers’ Reading Interest and Joint-Reading Engagement

Shu-Chuan Wu

Abstract

Prior research in the Western societies has revealed both the socioemotional

interaction and parental reading strategies during parent-child joint-reading sessions

significantly predicted children’s reading motivation. Children’s reading motivation,

in turn, is related to their later literacy development and school success. Although

Chinese parents are much concerned with their children’ academic achievement,

shared reading is not a common activity in traditional Chinese families. The goal of

this study is to investigate how Chinese mothers’ socioemotional behaviors and

joint-reading skills may predict preschoolers’ reading motivation. In order to give

Taiwanese parents sensible suggestion suitable for their family background about the

way to implement joint-reading activities, this study also examined the moderating

effect of child’s sex and maternal education level on the relation between maternal

behaviors and child’s reading motivation. A coding scheme was developed in this

study to capture the culture-specificity of Chinese mothers’ joint reading behaviors.

Fifty-one mothers and their 50- to 60-month-old preschoolers completed two

10-minute joint-reading sessions 7 to 14 days apart. Maternal behaviors were coded

vi

into two major behavioral aspects by time sampling method. The aspect of

Socioemotional Expression was further divided into two dimensions of

Child-Centered Behavior and Parent-Centered Behavior. The aspect of

Cognitive/Linguistic Guidance was further divided into four dimensions of Teaching,

Elaboration, Specific Question, and Open-Ended Question. Hierarchical regression

analyses on maternal rating of child’s everyday reading interest and observer’s rating

of joint-reading engagement revealed the following results. (1) Mothers’

Child-Centered Behavior positively predicted child’s reading engagement, but did not

predict child’s everyday reading interest. Parent-Centered Behavior inversely

predicted child’s reading interest as well as engagement. (2) Specific Question asked

by mothers inversely predicted child’s reading interest. (3) Girls showed more

everyday reading interest than did boys, but gender could not predict child’s

joint-reading engagement. (4) Maternal education level moderated the predictability

of Parent-Centered Behavior and Elaboration on child’s joint-reading engagement.

(5) Maternal education level also moderated the predictability of Child-Centered

Behavior on child’s reading interest. The coding scheme developed in the current

study helped revealed that Chinese mothers’ Teaching behavior per se would not

harm children’s reading motivation. It was Parent-Centered Behavior, such as

criticism, demand for reading tempo, and unresponsiveness, that played a negative

vii

role in children’s everyday reading interest. In addition, Child-Centered Behavior

played a positive role in reading interest among preschoolers of mothers in the lower

bracket of education level.

Key words: Shared Reading, Chinese Parenting, Child-Centered Behavior,

Parent-Centered Behavior, Maternal Joint-Reading Behaviors,

Reading Motivation.

viii

Contents Introduction

Preface ……….…….…..…. 1

Role of Parenting Quality in Shared Reading ……….…….…..…. 6

Shared Reading in Chinese Society ……….…... 8

Reading Motivation of Chinese Children ……….….. 13

Role of Child Gender and Mother’s education al level to Children’s Outcomes of Shared Reading ……….……….………. 14

Behavioral Coding Scheme for Shared Reading Interaction ……….…. 17

Overview of the Current Study ………... 28

Method

Participants ……….….….. 36Procedure ………....… 37

Results

Preliminary analyses ……….……….………..………... 46Central analyses ………..………..… 50

Discussion ………..……….…….. 64

References ………..……….……. 77

Appendix

Appendix 1: Introduction form for kindergarten ………..…………. 93ix

Appendix 2: Consent form for Kindergarten ……….…... 94

Appendix 3: Consent form (first time) ………..…... 95

Appendix 4: Consent form (second time) ………..…... 96

Appendix 5: Experimental introduction (the first time visit to the laboratory) 97

Appendix 6: Experimental introduction

(the second time visit to the laboratory) ……….…. 99

Appendix 7: Detailed coding definitions and examples ……… 101

Appendix 8: Coding sheet ……….… 106

Appendix 9: Examples of coding scheme during joint reading session …… 107

x

Tables and Figures

Table 1. Definition and Examples for Maternal Reading Behaviors ……… 44

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables ……….. 47

Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables for Child Gender

and Maternal Educational Level ..………... 49

Table 4-1. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Engagement

in Session A with Maternal Educational Level as Moderator ……… 52

Table 4-2. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Engagement

in Session A with Child Gender as Moderator ……… 53

Table 4-3. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Engagement

in Session B with Maternal Educational Level as Moderator ……… 55

Table 4-4. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Engagement

in Session B with Child Gender as Moderator ……… 56

Table 5-1. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Reading

Interest in Session A with Maternal Educational Level as Moderator 58

Table 5-2. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Reading

Interest in Session A with Child Gender as Moderator ……….. 59

Table 5-3. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Interest in

Session B with Maternal Educational Level as Moderator …………. 61

xi

Table 5-4. Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Predicting Child Reading

Interest in Session B with Child Gender as Moderator ………. 62

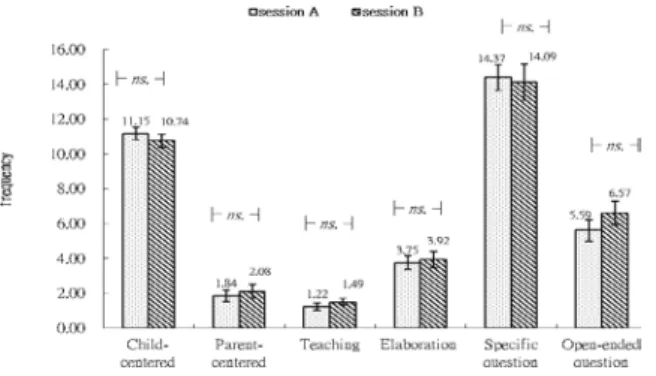

Figure 1. Frequency of the six maternal behaviors in two sessions ………. 48

Figure 2. Frequency of maternal behaviors between mothers with different

educational level in session A ………. 48

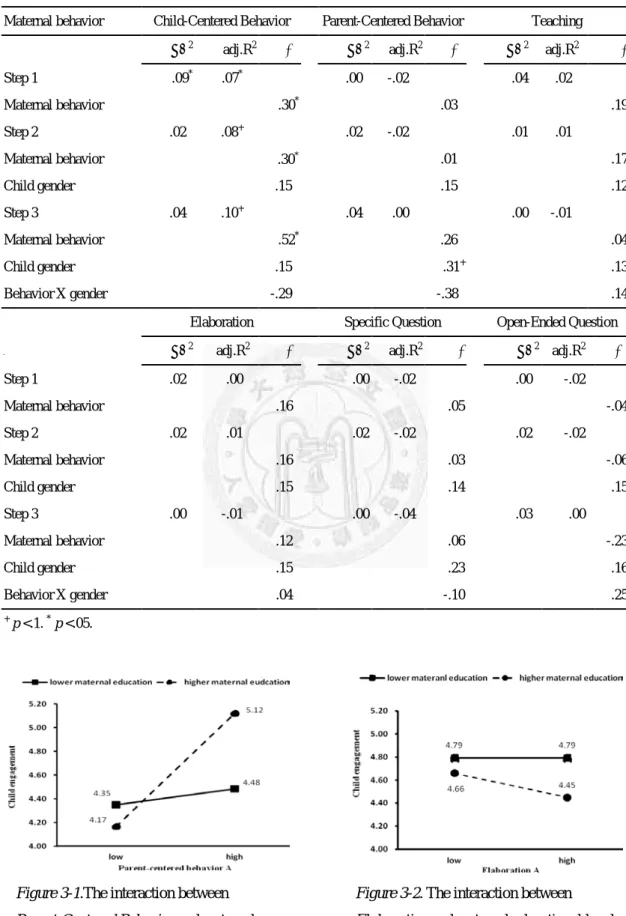

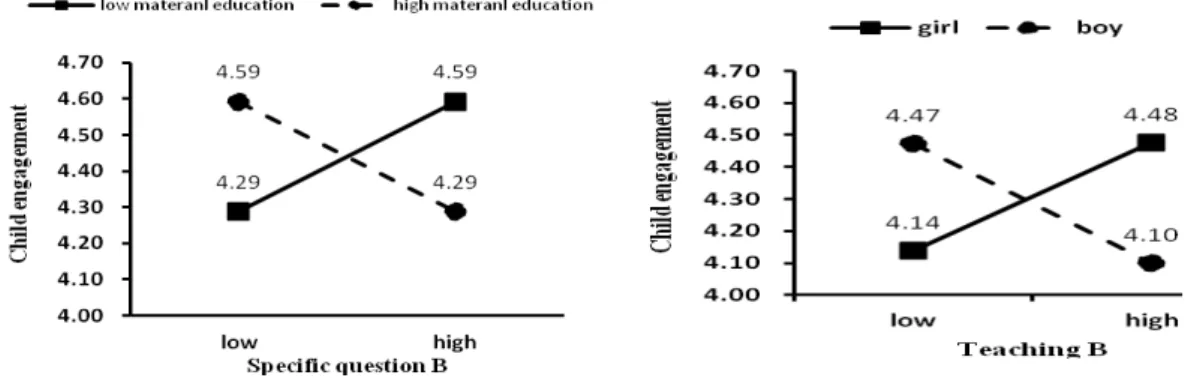

Figure 3-1. The interaction between Parent-Centered behavior and maternal

educational level on child engagement in session A ………. 53

Figure 3-2. The interaction between elaboration and maternal educational level

on child engagement in session A ……… 53

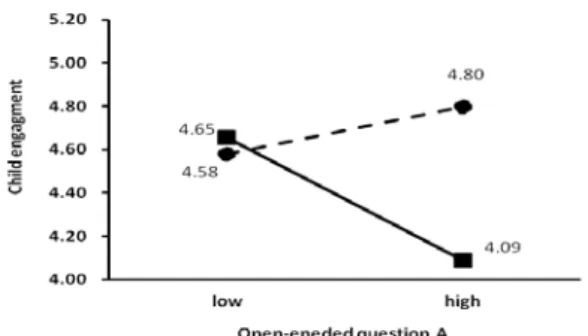

Figure 3-3. The interaction between Open-ended question and maternal

educational level on child engagement in session A ………….… 54

Figure 4-1. The interaction between Specific question and maternal educational

level on child engagement in session B ……….. 57

Figure 4-2. The interaction between teaching B and child gender on child

engagement in session B ………. 57

Figure 5. The Interaction between Child-centered behavior and maternal

educational level on child interest in session A ……….…… 60

Figure 6. The interaction between Parent-centered behavior and child gender

on child interest in session B ……….…………. 63

1

Introduction

Preface

Home literacy activities such as storybook reading are important not only for

children’s language development but also for subsequent reading ability and academic

achievement (Aram, 2008; Fletcher & Reese, 2005; Vandermaas-Peeler, Nelson,

Bumpass, & Sassine, 2009). Thus, in recent years, parent–child storybook reading

has became one important and frequently studied context for literacy development.

Through reading storybooks with parents, children are exposed to advanced language

and concepts (Bus, van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995; Torr, 2004). Parents’

interactive behaviors other than reading the text verbatim during joint book reading,

such as labeling and asking questions, were also found a useful component for

enhancing children’s language skills (Neuman & Gallaher, 1994; Whitehurst et al.,

1988). Meanwhile, discussion about books is found contributive to the development

of comprehension, phonological and graphemic skills necessary for reading (Snow &

Burns, cited in Sonnenschein & Munsterman, 2002).

Yet, shared reading may not always be beneficial to children as aforementioned.

In a meta-analysis of thirty-three empirical studies investigating the frequency of

parent-preschooler book reading, Bus et al. (1995) noted that if children were not

interested in book reading or if they found it aversive, encouraging their parents to

2

read more to them might conversely impose a negative effect on literacy development.

They suggested that forcing a child to listen to a story when he or she does not want to

may decrease the child’s interest in shared reading (Bus et al., 1995). Scarborough,

Dobrich and Hager (1991) followed a group of children from 30 months to 8 years of

age, and found children who later became poor readers entertained themselves with

books only 2 to 3 times per week, while children who became good readers typically

were engaged by reading activities daily. Since children’s reading motivation takes

an important part in their literacy development, there is a growing awareness of the

necessity to study the factors enhancing early reading motivations and the desire to

engage in literacy activities.

Sonnenschein and Munsterman (2002) observed a group of 5-year-olds reading

with their family members and found that, although reading frequency was a

significant correlate of early literacy-related skills, the affective quality of reading

interaction was the most powerful predictor of children’s motivations for reading.

Moreover, different research have suggested that exposure to printed matters before

formal learning starts may foster preschoolers’ reading interest by associating literacy

experiences with positive, enjoyable interactions (Baker, Mackler, Sonnenschein, &

Serpell, 2001; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994). In addition, Baker et al. (2001) also

found that the affective atmosphere during dyadic reading interactions between first

3

graders and their mothers was related to the frequency of reading chapter books later

in the second and third grade. Taken together, children who experience pleasant

reading interactions early on seem more motivated to read continuously and

frequently. Parents, in turn, often are responsible for cultivating such fun and

enjoyable reading experiences for young children.

Bus et al. (1995) indicated that the role of parents in shared reading activity is to

provide assistance and support that allows and encourages children to participate in

reading interaction. As researchers (Bus & van Ijzendoorn, 1997; Bus et al., 1995)

concluded, shared book reading is a social process and learning to read is associated

with the affective dimension of the mother-child relationship. Parents’ general

supportive attitude and warmth have been found to associate with children’s emerging

literacy ability (Berlin, Brooks-Gunn, Spiker, & Zaslow, 1995; Fitzgerald, Schuele, &

Roberts, 1992) and positive child behaviors such as focused attention and enthusiasm

(Frosch, Cox, & Goldman, 2001). Mother’s praise and enthusiasm have also been

indicated to encourage child’s participation during shared reading (Britto,

Brooks-Gunn, & Griffin, 2006). Those results pointed out how the socioemotional

aspect of parental interactive behaviors during shared reading may affect children’s

reading interest and engagement in reading activities, which, in turn, would bring

about the positive outcomes of literacy development.

4

Knowing that parent-child shared reading activities are strong predictors of

successful emergent readers and later reading achievement (Baker, Scher, & Mackler,

1997; Ortiz et al., 2001; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994), Taiwan’s Ministry of

Education (MoE) announced the “National Children Reading Program” in the year

2000. This program has been well accepted by Taiwanese parents because it

matches closely with the general belief of the necessity of providing children with

academic preparedness ahead of their developmental schedule. Through the

promotion of MoE, the majority of kindergartens in Taiwan has installed reading

sessions in their school programs in recent years. Preschool teachers also regularly

recommend parents to establish shared book-reading routine with their children at

home.

Nevertheless, the abovementioned benefits from parent-child shared reading are

coming from research conducted in the Western societies, where shared book reading

is a typical family custom and daily routine. On the contrary, although Chinese

parents are often highly involved in their children’s learning activities (Stevenson &

Lee, 1990), shared book reading is not an often-found everyday activity in traditional

Chinese families (Li & Rao, 2000; Wu, 2007). In addition, unlike American parents

that often view positive emotions as an important component during parent-child joint

book reading, Chinese parents were reported to endorse traditional styles of teaching

5

and emphasizing repetitive drills while helping their children to learn new materials

(Johnston & Wong, 2002). These cross-cultural differences of parental attitude and

behaviors may be originated from the idiosyncratic meaning system of learning in

Chinese societies and may alternate the positive effect of joint reading on Chinese

children that were found in the Western societies. Consequently, how Chinese

parents interact with their young children in shared reading activities and how the

shared reading experience plays a role in children’s reading motivation deserve

detailed investigation.

In the present study, a new coding scheme would be developed to capture the

behaviors of Chinese mothers during shared reading. Through this newly designed

coding system, this study attempted to document how Chinese mothers, bounded by

the cultural beliefs of the importance of academic excellence, may react to a shared

reading opportunity with their young children and how their shared reading behaviors,

both in the socioemotional and cognitive/linguistic aspects, contributed to children’s

reading motivation. Moreover, with the intention of giving practical advice to

parents of different family backgrounds, this study would also capture how

demographic factors such as child’s gender and mother’s educational level moderated

the predictive effect of maternal joint reading behaviors on preschoolers’ reading

motivation.

6

Role of Parenting Quality in Shared Reading

Western research on shared reading interaction have pointed out that children’s

reading skills and interest may be cultivated by engaging, fun, and emotionally warm

reading experiences that are often first experienced with parents (Bergin, 2001;

DeBaryshe, 1995; Sonnenschein & Munsterman, 2002). Therefore, there are

increasing interests in how the affective and socioemotional components of parental

behaviors are related with children’s shared reading experience, which may

subsequently affect children’s reading outcomes (Bergin, 2001; Frosch, Cox, &

Goldman, 2001; Landry et al., 2011; Ortiz et al., 2001). For example, Bergin (2001)

conducted an observational study to address the importance of the affective quality of

parental behaviors during shared book reading with kindergarteners and first-graders.

Affect-related behavioral and emotional dimensions such as praise, hostility, criticism,

support, positive affect, emotional spontaneity, physical proximity, and affection were

included in the coding scheme for parental behaviors. Results showed that children

were less frustrated and more engaged if their dyadic interactions with the parent

during joint reading were more affectionate.

Frosch et al. (2001) also included the affective aspects of maternal behaviors

with their 24-month-olds during shared book reading in their coding scheme.

Among the coded dimensions of degrees of sensitivity (e.g., emotional support),

7

intrusiveness (e.g., lack of recognition of the child’s effort to be independent),

detachment (e.g., emotionally uninvolved), positive (e.g., positive affect and

enjoyment) and negative regard (e.g., hostility, impatience toward the child), flatness

of affect (e.g., how animated the parent is in terms of facial and vocal expressiveness),

and stimulation of cognitive development (e.g., degree of parental supports and

encouragement), Frosch et al. found the more warm/supportive and cognitively

stimulating and the less hostile/intrusive and detached were the parents, the more

compliant, attention-focused, enthusiastic, and emotionally positive were the children

during storybook interaction.

Similar findings were also shown in an intervention program by Landry et al.

(2011), which focused not on the reading instruction per se but the parenting

strategies enacted during daily activities, including shared reading. Landry and her

colleague (2011) applied the Play and Learning Strategies (PALS) intervention to

parents with children ranging from infants to preschoolers. The overarching goals of

PALS were targeted at increasing maternal affective (e.g., praise, encouragement and

responsiveness) and cognitive–linguistic supports (e.g., scaffolding, verbal

prompting). After eleven weeks of intervention, maternal behaviors were observed

during a shared reading session. The results revealed that PALS was effective in

changing mothers’ behaviors in areas such as positive affect (e.g., praise,

8

encouragement, and responsiveness) and the effectiveness in shared reading

interaction (e.g., frequency and richness of book-related language input, usage of

verbal scaffolding strategies, open prompts, and book-related comments). Children’s

engagement and use of language in the shared reading contexts, in turn, were

enhanced. Other research also indicated that, given an affectively responsive climate

during shared reading, children were more likely to stay focused on the reading

material, cooperate with the mother’s requests, show more enthusiasm to the reading

experience and, consequently, open themselves to more opportunities to involve in

shared reading experience (Bus et al., 1997; Leseman & de Jong, 1998).

The above findings imply that children’s reading motivation may be enhanced by

the positive quality of parent-child interaction, which, in turn, would promote

children’s literacy development. After all, once children can take pleasure in book

reading, they may actively look for books and for opportunities to read alone or

jointly with their parents.

Shared Reading in Chinese Societies

The foregoing findings are mostly observed in the Western societies where

parents generally value storybook reading as a medium of family entertainment and

reading together as a special time to share and bond with their children (Leseman &

de Jong, 1998; Sonnenschein et al., 1997). Unlike American parents’ relaxed and

9

fun approach to literacy learning, Chinese parents’ approach to literacy learning is

often more serious. For example, Johnston and Wong (2002) suggested that

American parents viewed positive emotions as an important component during

parent-child joint book reading, while Chinese parents were often reported for their

emphasis on using picture books and flash cards for children to learn new words.

This cross-cultural difference may be originated from the strong emphasis of

academic achievement in Chinese societies. Since academic achievement is the

most effective measure for transferring social stratification, Chinese parents are often

highly engaged in their children’s achievement-related activities compared to their

Western counterparts (Huntsinger, Jose, Liaw, & Ching, 1997; Stevenson & Lee,

1990). Moreover, most Chinese parents believe preschool-age is the appropriate

time to start literacy teaching, and regard literacy teaching at home a necessary

preparation for elementary school (Jing, 2004; Li, & Rao, 2000). A study conducted

in Hong Kong suggested that the majority of preschools start teaching children to read

single Chinese characters as young as they are only three years old (Ho & Bryant,

1997).

Shared reading activities have been particularly introduced to Taiwan, a

culturally Chinese society, during the last decade due to its multi-dimensional benefits

in children’s literacy development documented in the literature. Taiwan’s Ministry

10

of Education formally announced the “National Children Reading Program” at the

year 2000. Since then, parents have been encouraged to apply shared reading

activity as a way to create positive learning environment at home. However, there

are still few researches on joint book reading conducted in Taiwan. From a recent

literature review by Chang and Liu (2011), three main findings from eighteen

published studies were obtained: (a) a child’s reading attitude was related to the

reading habits, educational levels, and occupations of his/her parents, (b) individual

differences in parent-child interaction patterns during joint book reading were evident

and these patterns varied across the age of the children, and (c) joint book reading

practices at home facilitated children’s language ability (p.336). Chang and Liu’s

(2011) conclusion corresponds with Hui and Salili’s (2008) study using a sample from

Beijing, China. Hui and Salili (2008) examined the relation between home literacy

and 3- to 6-year-olds preschoolers’ intrinsic motivation for reading. Among the

home literacy variables, they found parental model of reading behaviors, number of

books at home, and number of years of home teaching in Chinese characters

significantly contribute to the Chinese preschoolers’ persistence and voluntary

engagement in reading-related activities.

Nevertheless, the majority of the studies reviewed by Chang and Liu (2011) were

collected by questionnaires or semi-structural interviews. Five of the eighteen

11

studies were designed to observe parent-child interaction during joint reading.

However, the coding schemes for these studies were designed to capture the narration

of parents or children. Little is known about these parents’ affective quality,

responsiveness, or practices of cognitive guidance during joint reading.

There is one study conducted in the US but using Taiwanese sample to explore

the parental behaviors during shared reading beyond narration per se. Wu (2007)

conducted a multi-method research in the Tainan city to investigate the relation

between Taiwanese mother’s belief systems about reading, their shared reading

behaviors, and their preschoolers’ emergent literacy outcomes. Wu observed

maternal reading strategies while reading together with their 3- to 5-year-olds and

measured these preschoolers’ language ability as the outcome variable. Results

showed that the most frequently used maternal joint reading strategy was “pointing,”

followed by “asking convergent questions (e.g., yes/no questions),”

“labeling/describing,” “asking divergent questions (i.e., open-ended questions),” and

“elaboration,” The least used strategies were: “extending/correcting,” “skills

demonstration,” and “asking prosocial elements.” In addition, children’s language

outcomes were conversely predicted by maternal strategies of pointing” and

“labeling/describing.”

Unfortunately, Wu (2007) only explored maternal cognitive/linguistic guidance

12

but not maternal affective and responsive expressions during share book reading,

rendering no clue of how the affective component during shared reading in Chinese

families may influence children’s reading attitude and motivation or literacy

achievement. Wu and her colleague (2010) further assessed maternal belief of early

reading, which is likely to be a critical component for the affective expression that

mothers display while reading to their children. Taiwanese mothers’ belief about

reading aloud for preschoolers was assessed by the Chinese version of Parental

Reading Belief Inventory, PRBI (DeBaryshe & Binder, 1994), and was compared

with that of DeBaryshe and Binder (1994) using an US sample. Through the

questionnaire that mothers filled, they found 90% of the Taiwanese mothers agreed

that parents should teach children how to read before they start school and they placed

more value on the moral and practical knowledge that children would gain from

storybook reading, whereas American parents viewed positive emotions during joint

book reading as more important than other factors.

Findings from Wu (2007) and Wu and Honig (2010) are consistent with those of

many cross-cultural studies between culturally Chinese and Western societies

(Huntsinger, Jose, Liaw, & Ching, 1997; Johnston & Wong, 2002; Stevenson & Lee,

1990) indicating that education and formal learning is highly emphasized by Chinese

parents. Based on the different attitude of Chinese parents as opposed to parents in

13

the Western societies on shared reading, it is worthwhile to investigate both the

cognitive/linguistic and the socioemotional aspect of behavioral styles that the

Chinese parents may particularly demonstrate when they interact with their children

during shared reading activity and how the style would predict children’s outcomes.

Reading Motivation of Chinese Children

In 2006, a total of 4589 Taiwanese 4th-graders attended the Progress in

International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS 2006) conducted by the International

Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. The goal of this

international association is to measure trends in children's reading literacy

achievement and practices related to literacy across countries. The results (Ko, Chan,

Chang, & Yo, 2008) showed that the mean reading score from Taiwan was 535,

slightly above the international mean score, 500. However, only 24% of the

Taiwanese participants responded positively to the question ”reading for fun on

average reading every day or almost every day.” The percentage was the lowest

around the world (international mean value: 40%). Meanwhile, the report also

indicated that Taiwanese parents read less by themselves. Even though the literacy

resources in home environment that Taiwanese parents set up for their children (e.g.

children’ books) were richer than some other countries, the frequency of shared

reading activities was lower.

14

It should be noted that the international report indicated that students with the

most positive attitudes toward reading generally have the highest reading achievement.

This result corresponds with prior Western findings that children’s reading motivation

poses an important part on literacy development (Baker et al., 2001; Lonigan, 1994;

Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994; Sonnenschein, & Munsterman, 2002). Unfortunately,

the PIRLS study seems to indicate that enjoyment to read is exactly from which most

Taiwanese children lack.

Hence, the present study intended to develop a coding scheme to incorporate

both the socioemotional and the cognitive aspect of joint reading behaviors

particularly salient among Chinese parents in order to capture the factors that lead to

limited general reading interest among Taiwanese children.

The Role of Child Gender and Maternal Educational Level in Shared Reading

When examining factors related to parent-child interaction during shared reading,

child gender is often served as a controlled variable (Senechal, LeFevre, Thomas, &

Daley, 1998). However, the role of child gender played in parent-child literacy

interaction may worth investigating directly. For example, prior research have

indicated that mothers pointed out letter details more often to boys (Evans, Barraball,

& Eberle, 1998) and asked more Specific Question to girls (Meagher, Arnold,

Doctoroff, & Baker, 2008). It seems that, while reading to their children, mothers

15

display different behaviors based on their children’s gender. For example,

Tamis-LeMonda, Briggs, McClowry, and Snow (2009) examined the relation between

mother’s parenting (control and sensitivity) and their 6- to 7-year-old children’s

behaviors during cooking task and clean-up task. Boys were observed with less

responsiveness and task involvement than girls, and were rated by their mothers as

having more behavior problems as well. In the meantime, their result revealed that

mothers of boys exhibited less sensitivity and more control than mothers of girls.

After controlling for mothers' sensitivity and control, gender difference in children’s

behaviors maintained. Tamis-LeMonda et al. concluded that, at this young age,

boys' lower responsiveness and task involvement relative to girls was at least partly

mediated by mothers' increased use of control and lower sensitivity since mothers of

boys were aware of the behavioral problem that boys would exhibit. By the same

token, it is interesting to understand how maternal behaviors and child’s gender may

interact in predicting child’s reading motivation.

Maternal educational level is another variable that should be investigated

carefully when studying the relation between maternal joint reading behaviors and

child’s literacy development. For example, Bus et al. (1995) compared the

differences between middle-income and low-SES families over the frequency of

storybook reading and parent-child interaction during joint reading. They found

16

children’s literacy development was not decided by how enriched the written

materials were in the environment, but by how strong of the parental ability to involve

young children in literacy-related experiences. The extent that parents can facilitate

children’s reading involvement, in turn, may have a lot to do with their educational

level. Past research has documented that higher maternal educational level predicted

higher maternal sensitivity and higher scores from the Home Observation for

Measurement of the Environment Inventory (HOME), which has been found to

contribute to children's language and early literacy skills (Roberts, Jurgens, &

Burchinal, 2005). By the same token, low-literacy parents were reported not as

sensitive to their children as higher educated parents. They tended to control their

children intrusively (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2009). In contrast, parents of higher

literacy valued informal and playful interaction as useful medium for literacy learning

(Baker, Sonnenschein, & Gilat, 1996; Fitzgerald, Spiegel, & Cunningham, 1991;

Goldberg, MacKay-Soroka, & Rochester, 1994; Sonnenschein et al., 1997). In

addition, research using Taiwanese samples also indicated that parental educational

level is a significant correlate of children’s reading attitude (Chang & Liu, 2011).

Since parents of different educational level may perceive children’s learning in

different ways, it would be interesting to understand whether parental educational

level would moderate the relation between parental joint reading behaviors and

17

children’s reading motivations.

In sum, both child gender and maternal educational level are worth further

investigation in terms of their roles in bringing about children’s reading motivations.

Meanwhile, from the perspectives of both governmental institution and non-profit

private sectors, or even pediatricians (Wu, Lue, & Tsengn, 2012), that are interested in

promoting parent-child joint reading activities in Taiwan, to provide appropriate

guidance based on the specific characteristics of the child and the family background

may help make joint reading a prolonged and well-liked family activity. Research

on the moderating effect of maternal educational level and child gender on the relation

between maternal behaviors and child reading motivation is the first step to reach this

practical goal.

Behavioral Coding Scheme for Shared Reading Interaction

Derived from the above literature review, the present study firstly intended to

capture the affective and socioemotional components of maternal behaviors during

mother-child reading contexts and document how these dimensions of maternal

behaviors are related with children’s reading motivation, which are manifested in

children’s engagement during shared reading context as well as their everyday reading

interest. Meantime, based on prior findings of Chinese parents’ emphasis on

academic effort and cognitive performance, this study was also interested in how

18

Chinese mothers would facilitate their preschool children’s cognitive involvement in

the joint reading activity. With the above goals in mind, this study developed a

coding scheme to depict both the aspect of Socioemotional Expression and

Cognitive/Linguistic Guidance from mother in joint reading contexts.

(1) Socioemotional Expression: Children’s socioemotional development has

long been associated with parenting behaviors. One factor that relates to parenting

behaviors may be the goal that parents set in the hope to achieve while interacting

with their children, which are frequently cited as pivotal in determining parenting

practices (Coplan, Hastings, Lagace-Seguin, & Moulton, 2002; Dix as cited in

Hastings & Grusec, 1998). Three broad categories of parenting goals, namely, the

Parent-Centered, Child-Centered, and Relationship-Centered goal have been

identified by Dix (as cited in Hastings & Grusec, 1998) and Grusec and Goodnow

(1994). The Parent-Centered goal is associated with parenting behaviors aimed at

disciplining and gaining immediate compliance from the child, and establishing

parental authority. The Child-Centered goal is categorized as two goals:

socialization goal--teaching a child an important value or lesson, and empathic goal--

satisfying a child's emotional needs to promote positive feelings. The

Relationship-Centered goal is referred to the parental desire to foster close and

harmonious bonds within the family. Hastings and Grusec (1998) established the

19

link between goals and behavior and found that Parent-Centered goal was associated

with higher rates of power assertion and lower levels of responsive actions, such as

warmth and acceptance; conversely, Child-Centered goals were associated with low

power assertion and higher responsiveness (empathic goal) and pursuing the use of

reasoning (socialized goal). Relationship-Centered goal was associated with most

warm, negotiating, and cooperative parenting behaviors.

The differentiation of Parent versus Child Centered goals and behaviors also

corresponds with parenting models conceptualized by both Baumrind (1971) and

Maccoby and Martin (1983). Specifically, research based on Baumrind’s (1971)

authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive typology has found that compared to

authoritative parents, authoritarian parents were more likely to practice

Parent-Centered goals and less to Child-Centered goals in their parenting techniques

(Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002). In addition, research based

on Maccoby and Martin’s (1983) two-dimensional model of parental

warmth/responsiveness and control/demandingness has found that parental

responsiveness, in concordance with the effect found for Child-Centered practice,

significantly predicted children's academic readiness, self-regulation, and social

competencies (Burchinal & Campbell, 1997; Kelly, Morisset, Barnard, Hammond, &

Booth, 1996; Landry, Smith, Swank, Assel, & Vellet, 2001). On the other hand,

20

parental control/demandingness, in concordance with the effect found for

Parent-Centered practice, was linked to children’s negative affect, low mother–child

mutuality, and less affection toward mothers (Culp, Hubbs-Tait, & Culp, 2000; Ispa et

al., 2004).

In addition, parenting strategies often revealed in Chinese families may also be

comprehended through the Western framework of Parent-Centered versus

Child-Centered practice. For example, Chao (1994, 2001) as well as Lin and Fu

(1990) reflected that Chinese parenting practices are more restrictive, controlling, and

authoritarian than those from Western parents. If a child misbehaves or shows bad

manners, it is viewed as a reflection of poor “cha chiao,” and/or not well “guaned,”

which can be translated as “family education” and “governing/training” respectively

(Kelly & Tseng, 1992). Consequently, “governing/training” (i.e., Guan) (Chao,

1994), which are often manifested in parental demand and power-assertion, may be

regarded as Parent-Centered Behaviors.

In this study, mothers’ Socioemotional Expression was categorized into two

dimensions based on prior literatures: Child-Centered and Parent-Centered Behavior.

A. Child-Centered Behavior: Child-Centered Behavior was coded when mother

displayed sensitive parenting in response to the child’s need, showed positive affect,

or provided an enjoyable interactive environment for her child to engage in reading

21

activities. Sometimes, the mothers may verbally invite their children to join the

reading activity in a question format or they may adjust their prior unanswered

questions to match better with the child’s current state or comprehension ability.

These two types of questions, although may differ largely in terms of content, both

take the child’s interest, ability, and state into consideration and may be regarded as a

reflection of maternal sensitivity. Therefore, they were included in the coding

dimension of Child-Centered Behavior. The coding scheme of Child-Centered

Behavior consisted of six subcategories.

(a) For Fun: such as mother changing her voice to pretend to be the character(s)

in the book, making gestures related to the story content, or reading aloud with an

expressive tone.

(b) Praise: such as mother expressing a favorable justification about the child’s

behavior, either verbally or nonverbally.

(c) Responsiveness/Sensitivity: such as mother displaying contingent behaviors in

response to the child’s actions, and adjusting her own behavior according to her

child’s needs or abilities.

(d) Positive Affect: such as mother expressing warmth and emotional closeness

with her child.

(e) Q-Entertainment/Creativeness: such as mother using creative, fun, and loving

22

tones to ask child questions in order to invite the child to join in the reading activity.

(f) Q-Adjustment: such as mother readjusting their unanswered questions to

match better with the child’s current state or comprehension ability (e.g., When one

mother asked “What is this machine for?”, if her child didn’t know the answer, and

the mother adjusted her question to “When your clothes are dirty, which machine will

we put those clothes into?” then the latter question would be coded as Q-adjustment.).

Past research have pointed out that the higher level of maternal responsiveness

and sensitivity, the better in children’s social, cognitive, and language development

(Landry et al., 1997; Landry et al., 2001). Meantime, parents being warm and

supportive positively predicted children’s attentiveness and enthusiasm during story

book interaction (Frosch, Cox, & Goldman, 2001). This research thus predicted that

Child-Centered Behavior would positively predict children’s reading interest and

engagement.

B. Parent-Centered Behavior: Parent-Centered Behavior was coded when the

mother followed her own agenda, showed power assertion on her child, or aimed at

disciplining or gaining immediate compliance from her child. Specifically, the

coding scheme of Parent-Centered Behavior consisted of five subcategories.

(a) Demand on Tempo: such as mother pushing the tempo of joint reading with

no respect to the child’s reading rhythm.

23

(b) Discipline/Criticism: such as mother exerting verbal or non-verbal

intrusiveness over the child, criticizing the child, or applying disciplinary strategies

such as love withdraw toward the child.

(c) Directives: such as mother verbally ordering her child to read.

(d) Non-Responsiveness: such as mother being uninvolved, lacking recognition

of the child’s need, and ignoring the child's interests and desires

(e) Negative Affect: such as mother speaking with a negative emotional tone or

frowning disapproval at her child’s behaviors.

Past research has indicated that the frequency or level of maternal intrusiveness

was significantly and inversely correlated with 6-year-olds’ language scores and

academic competence (Olson, Bates, & Kaskie as cited in Culp, et.al. 2000). In

addition, parental directives were found to inhibit a child’s vocabulary development

(Landry et al., 1997). Therefore, this study expected that maternal’ Parent-Centered

Behavior of exerting high demand over children and intrusiveness would hamper and

thus negatively predict children’s reading interest and engagement.

(2) Cognitive/Linguistic Guidance: Chinese parents often start to cultivate their

children’s academic working habit as early as possible. As a result, even in

preschool years, parents may have already applied different ways of cognitive and

linguistic guidance to advance their children’s knowledge and improve their reasoning

24

ability. The aspect of Cognitive/Linguistic Guidance in the current coding scheme is

referred to the literacy-related strategies that parents performed in order to teach new

words, provide new information, and facilitate cognitive development via the reading

material. This aspect consists of five dimensions.

A. Teaching: Traditionally, Chinese regard learning and knowledge acquisition

being more effective through repetitive exposure and memorization. Johnston and

Wong (2002) reported that Chinese parents used picture books and flash cards to teach

their children new words and believe children learn best through formal instruction

(Johnston & Wong, 2002). On the other hand, Wu (2007) indicated that Taiwanese

mothers conceived that children would gain moral and practical knowledge from

storybook reading. Therefore, in this study, Teaching included three subcategories.

(a) Formal Learning: such as mother teaching new words, correcting the child’s

verbal mistakes of grammatical or semantic errors, testing the child’s counting or

reading ability.

(b) Moral Lesson: such as mother emphasizing the manners or morally-correct

act described in the book.

(c) Q-Moral/Conventional: referring to questions that were related with the book

and, meantime, had something to do with observing manners, moral standards, and

daily routine, such as being polite, saying “thank you,” brushing teeth after meal,

25

cleaning up, etc.

The above definitions about Teaching were designed to specifically reflect the

self-assumed role of Chinese parents in literacy activity. Teaching behaviors have

been found to promote children’s literacy ability (Evans, Shaw & Bell 2000; Senechal

& LeFevre, 2002), but how it is related to children’ reading interest and engagement

in shared reading context is yet to be explored.

B. Elaboration: Mothers might bring out statements indirectly related with the

content of the reading material, such as mentioning the past experiences of the child,

drawing inferences from the texts, or predicting the story line with new terms.

Elaboration was divided into two subcategories in the current study.

(a) Elaboration: such as mother bringing up conversation that is related to the

current reading material or the child’s previously mentioned topic, yet she has

elaborated the topic through mentioning child’s past experience or extended the topic

to provide new but related information

(b) Q-Past Experience: such as mother posing verbal questions to remind the

child some past experience that was similar with the content of the book

Prior research has pointed out that using a wider and more complex variety of

cognitive strategies, such as elaboration, was related to children’s higher scores on

tests of language skill (Roberts et al., 2005). The current study stretched the above

26

findings by expecting Elaboration may also relate positively with children’s interest

and engagement in joint reading.

C. Pointing: Pointing/labeling has been found to increase child responses and

attentiveness during storybook reading (Justice & Ezell, 2002). Therefore, Pointing

was coded whenever the mother pointed to words or pictures in the storybook.

D. Specific Question: Asking question during shared reading is one of the

strategies that mothers usually used when interacting with children. Good questions

posed at the right moment may facilitate further conversation and processing for

complex ideas, while questions posed at the wrong moment or with irrelevant content

may interrupt the ongoing thought flow and cool down the interaction. Since

questions posed by mothers during joint reading contexts may serve different

socioemotional/cognitive/linguistic functions, they were designated to different

dimensions in the current coding scheme.

Specifically, when questions were not at all related to the current context, they

were coded as part of Non-responsiveness in the Parent-Centered dimension of

Socioemotional Expression. When questions were particularly designed by the

mother to either entertain the child or make readjustment based on the child’s state or

need, they were included in the Child-Centered dimension of Socioemotional

Expression. When the content of the questions were related to the reading material

27

but seemed to connote moral/conventional teaching, they were included in the

Teaching dimension. When the content of the questions matched with the reading

material but seemed to extend to the child’s own past experience, they were included

in the Elaboration dimension. There are still other questions posed by mothers that

were related with the content of the reading materials. Some of them were

straightforward question about the content of the book with a fixed answer, while the

others were more open-ended that seemed to bid for deeper thinking or conversation.

These questions were included either in the dimension of Specific Question or

Open-Ended Question. In the dimension of Specific Question, only one subcategory

of Q-Fact was coded.

(a) Q-Fact: referring to the questions destined with specific answers most likely

findable in the text of the reading material (e.g. “what is it?”)

E. Open-Ended Question: Open-Ended Question may allow children to practice

skills of decontextualized language. Children’s experience with decontextualized

language that often requires high cognitive demand has been suggested to predict later

language ability and school success (Haden, Reese, & Fivush., 1996). In addition,

Open-ended questions that parents spontaneously offer during joint-reading may help

children gain vocabulary as well as motivate their interest in literary materials and

related activities (DeBaryshe, & Binder, 1994; Karrass, & Braungart-Rieker, 2005;

28

Ortiz et al., 2001; Sorsby, & Martlew, 1991). There were two subcategories of

Open-Ended Question in this coding scheme.

(a) Q-Open: referring to questions without fixed answers and subject to the

child’s own opinion (e.g., “How would you do if you were that boy?”)

(b) Q-Cognition: referring to questions that may potentially elicit the child to

think in depth, such as questions about the concept of length, shape, and size (e.g.,

“Which one is longer?”)

In sum, the coding scheme developed in this study incorporated both the

Socioemotional Expression and the cognitive/linguistic guidance of joint reading

behaviors as well as the behaviors that may be particularly salient in Chinese parents

due to their belief in formal instruction and the power of practicing and drilling.

Overview of the Current Study

This study intended to investigate how Taiwanese mothers’ joint reading

behaviors contribute to preschool children’s motivation that is measured by their

everyday reading interest and engagement in a joint reading context. Although

shared reading activities have been encouraged by the Taiwanese government and

educators since the past decade, it is not a traditionally common home activity for

Chinese families. Instead, Chinese parents may take literacy learning more seriously

because they conceive themselves as having the responsibility of ensuring their

29

children being educated well (Chao, 1994). Therefore, some culture-specific

maternal behaviors were incorporated in the behavioral coding scheme to better

capture the variety of Chinese mothers’ shared reading behaviors. In the present

study, we specifically targeted at 4- to 5-year-old preschoolers and their mothers

because, at this age, literacy activities are often considered by adults as particularly

crucial in facilitating children’s language skills and cognitive ability.

Since regarding jointly reading with one’s parent as fun, warm, and rewarding

may increase preschoolers reading interest, which, in turn, may inspire the child to

actively seek all sorts of literacy activities and eventually benefit the child’s language

skill in general (Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994), this study assessed children’s

everyday reading interest and engagement in joint reading contexts as the outcome

variables. Children’s reading interest was reported by mothers through

questionnaire asking the frequency that the child actively looks at books at leisure

time and asks to be read to. Children’s reading engagement was assessed through

observers’ ratings of children’s behavior and emotion during two experimental

sessions of joint reading. By acquiring the outcome measures both from mothers

and observers and by assessing children’s reading motivation both through their daily

activities and behaviors during standardized observational sessions, this study adopted

a multi-method/multi-informant approach in order to capture a thorough view of

30

children’s reading motivation.

Each dyad was invited to participate in two reading sessions. In the first

reading session, the dyad was to jointly read an unfamiliar book and in the second

session the dyad read a familiar book that they had already brought home for one

week. Researchers argued that different degrees of familiarity to the books may

elicit different types of talk, and mothers may view familiar and unfamiliar books as

fulfilling different discourse functions (Goodsitt, Raitan, & Perlmutter, 1988; Haden

et al., 1996; Torr, & Clugston, 1999). For example, Goodsitt et al. (1988) noted that

children who are repeatedly exposed to and read to with the same book are familiar

with the context of the book, and that allows them to increase their active

participation during joint reading. Under such circumstances, mothers would aid the

child less in comprehending the book but demand the child to engage more

profoundly while jointly reading a familiar book (Phillips & McNaughton, 1990). In

addition, parents are more likely to point out the relation between the text and the

child's own experiences when they jointly read a familiar book; consequently, familiar

books produce more conversational interchange between mothers and preschoolers

than do unfamiliar books (Hayden & Fagan, 1987; Goodsitt et al., 1988).

Nevertheless, the effect of different book genre on maternal behaviors or on

children’s reading motivation were not of interest in the present study. Instead, the

31

goal of the current study was to investigate how commonly implemented maternal

joint reading behaviors among Chinese mothers are related with preschoolers’ reading

motivations. Since reading books with different levels of familiarity or book genre

would be the conditions that usually occur in daily life, the current design was to

sample a large enough portion of mothers’ joint reading behaviors. Therefore, the

participating dyads were asked to read two different books with different content and

different levels of familiarity in the two sessions such that it would provide a more

complete picture of the dyadic interaction in joint reading contexts.

A coding scheme for observing maternal behaviors during shared reading was

developed including some dimensions that were documented in Western literature and

some considered common in Chinese families. Maternal behaviors in the aspect of

socioemotional expression and cognitive/linguistic guidance were both included in the

coding scheme. Behaviors in the former dimension represent the quality of

parenting practice included Child-Centered Behaviors and Parent-Centered Behaviors.

Behaviors in the latter reflect maternal strategies to guide the child through the

content and the connotation in the text.

Past research on the Western families has revealed warmth/responsiveness (i.e.,

Child-Centered Behaviors) was positively related to children’s literacy development

(Burchinal & Campbell, 1997; Kelly et al., & Booth, 1996; Landry et al., 2001), while

32

control/demandingness (i.e., Parent-Centered Behaviors) was conversely associated

with children’s literacy development (Culp et al.,2000; Ispa et al., 2004). However,

recent cross-cultural comparison of school-age children and adolescents indicated that

despite Chinese parents exerted more psychological control in children’s learning,

heightened parental involvement predicted children’s enhanced engagement

positively (Cheung & Pomerantz, 2011). Therefore, on the one hand, this study

hypothesized that if mothers demonstrated more Child-Centered Behaviors during

joint reading, their children would be observed as engaging in more in reading

activities and reported with higher reading interest. More Parent-Centered

Behaviors was expected to predict negatively to child’s reading interest and

engagement. On the other hand, this study would document whether maternal

control, drilling, and non-responsive behaviors would indeed hamper children’s

reading motivation as found in their Western counterparts or facilitate children’s

reading motivation through the relatedness established through long-term involvement

of the Chinese mothers.

Finally, given the prior results indicating that boys are more active, and less

coordinated in emotion regulation (Knight et al., 2002), it is reasonable to expect that,

to facilitate preschoolers’ reading interest and engagement, mothers may need to

adjust their joint reading strategies based on the child’s gender. Therefore, this study

33

intended to document whether child gender plays a moderating role in the assiciation

between maternal joint reading behaviors and child reading interest and engagement.

Prior resesarch has not attempted to treat child gender as a moderator in the effect of

joint reading behaviors. Consequently, this study did not pose any specific

hypothesis in this part of investigation. However, since prior research has indicated

that mothers treat boys and girls differently in their frequency of pointing out letter

details (Evans et al., 1998) and the style of asking questions (Meagher et al., 2008) in

joint reading contexts, it would worth investigating whether the maternal behaviors

that have often found to apply on children of a particular gender would truly benefit

more for children of that gender. Therefore, in reference to Evan et al. (1998), this

study asked whether specific instruction of the print in the story book (i.e., maternal

Teaching) would benefit boys’ reading interest and engagement more than that of girls;

and, in reference to Meagher et al.(2008), this study asked whether the frequency of

Specific Question asked by mothers would positively relate to girl’s reading interest

and engagement more than those to boys.

Maternal educational level (Roberts et al., 2005; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2009)

have also been found to contribute to children’s literacy development positively.

The results from a study (Wu & Honig, 2010) investigating Taiwanese mothers

revealed that more highly educated mothers had higher belief on the contribution of

34

parental involvement to child’s formal learning and gains from reading storybooks.

In the meantime, these mothers themselves read more and reported significantly more

books in the home, which may also affect children’s emergent literacy behaviors such

as emergent reading and writing. Moreover, recent studies (Chen et al., 2000; Chen

& Luster, 2002; Xu et al., 2005) indicated that mothers with higher education are

more likely to be influenced by western culture, which might lead them to prefer

authoritative parenting rather than authoritarian parenting. In sum, prior research

has already documented that mothers with different educational levels treat their

children differently for cultivating their literacy development. Nevertheless, whether

Chinese mother’s educational level would predict child’s reading motivation,

manifested in their interest and engagement, or moderate the relation between

maternal reading behaviors and child’s reading interest is yet to be explored. This

question is important because reading motivation may cultivate the individual to

become a long-term reader, which may be more critical to cognitive development than

emergent literacy ability. Moreover, it would be especially beneficial to understand

the differential effect of different components of joint reading behaviors of highly

educated and not-so-well educated mothers on children’s reading interest. A

significant moderating effect would shed light for educators and pediatricians because

it may suggest that there are different ways to encourage and train mothers to apply

35

joint reading activities with their young children to facilitate their reading motivation

that may benefit the particular child in the years to come.