The dynamic competition, strategic enforcement through IPR

management: A case of bike component industry

Ching-Sung Wu1 Professor

Department of International Business National Taiwan University

Peter J. Sher2 Dean and Professor

Department of International Business Studies National Chi-Nan University

Joseph Y. Lu3 PhD student

Department of International Business National Taiwan University

Abstract

In the post-industrialized era, physical goods and assets play minor roles in firm’s growth and long-term profit step by step. Whether from academic or firms’ operation, intangible assets, tacit knowledge receive considerable focus. In the last decades, “intellectual property management” becomes the influential issue for firms’ innovation and sustained growth.

Intellectual property management is a topic of increasing interest to firms that derive their profits from innovations and knowledge-intensive assets. No matter what kind of sectors firms locate, they are faced fierce, rapid competition not from physical-based asset but from intangible-based assets. In other words, changing environment needs more and more innovations and firms have to be careful about providing superior goods and services to survive, however, these innovations are rapidly outperformed by competitors, how do firms cope with these dynamics? It is “intellectual property management”- their knowledge, experience, expertise, and associated soft assets, rather than their hard physical and financial capital- that increasingly determines their competitive positions.

This paper describes how a bike component firm (ranked the second position in world’s market share) competes against the dominant player through intellectual property management. Fierce competition makes two firms interact with each other’s strategies dynamically; it also illustrates the discriminating ways, these two players have been viewing their intellectual property management and some strategies they’ve utilized to get long-term growth with this new kind of perspective into business

1 Wu, Ching-Sung , E-mail: cswu@mba.ntu.edu.tw 2 Peter J. Sher, E-mail: sher@ncnu.edu.tw 3 Joseph Y. Lu, E-mail: d91724010@ntu.edu.tw

operation.

We investigate this research by integrating interview, patent analysis via USPTO, litigation judgment, and firm’s strategic actions, which can help us understand more about the application of IP in firm’s operation, competition.

Key words: patent infringement, patent citation analysis, M&A, Bike component

industry, intellectual property management, and strategy.

Introduction

What does intellectual property mean to firms? Either a document represents the firm’s image which is so-called “knowledge company” or a powerful, distinguished strategic tool that firms can really utilize in their strategic actions? If it is a newly strategic asset for firms, how does it transform from intangible into realistic ones? In the post-industrialized era, physical goods and assets play minor roles in firm’s growth and long-term profit step by step. Whether from academic or firms’ operation, intangible assets, tacit knowledge receive considerable focus. In the last decades, “intellectual property management” becomes the influential issue for firms’ innovation and sustained growth. As Teece (1998) notes, information age or so-called new economy changes the rule of conventional wisdom of “decreasing return in physical goods”, the return of utilizing knowledge assets could be expanded in three ways: (1) the rule of increasing returns, (2) integration with information technology, and (3) new angle to intellectual property rights. These three components build up solid bedrock for firms’ growth and innovation; intellectual property rights can’t help firms totally successful alone without bringing other two factors into consideration.

Intellectual property management is a topic of increasing interest to firms that derive their profits from innovations and knowledge-intensive assets. No matter what kind of sectors firms locate, they are faced fierce, rapid competition not from physical-based asset but from intangible-based assets. In other words, changing environment needs more and more innovations and firms have to be careful about providing superior goods and services to survive, however, these innovations are rapidly outperformed by competitors, how do firms cope with these dynamics? It is “intellectual property management”- their knowledge, experience, expertise, and associated soft assets, rather than their hard physical and financial capital- that increasingly determines their competitive positions.

Among all kinds of intellectual properties (including patent, trademark, copyright, and trade secret), filing patents becomes more and more animated, how are patents’ value? From the bottom line, owning patents can protect firms from litigation when firms engage in innovation and manufacturing, competitors can use various tactics interrupting rival firms’ operation, on the other hand, firms can profit from licensing, selling, or bartering their ideas. Therefore, managing patents (intellectual property) is no more a legal department’s business, it transfers from legal documents to strategic assets.

Taking intellectual property management into strategic mindset necessitates a fundamental shift in thinking about the dissemination of the firms’ intellectual properties. In particular, firms are accustomed to delineating such assets in the context of rigid legal definitions of intellectual property, which focus on restricting the use, sale, and transfer of intellectual capital in forms such as patents and copyrights. In contrast, leveraging intellectual capital requires that managers cautiously promote rather than restrict its use, reflecting an expansionist approach rather than a reductionist one that includes deliberating seeking out opportunities (Klein, 1998). In other words, development and exploitation intellectual property assets should focus on value extraction and maximization, rather than legal documents or cost minimization.

Those mentioned above show that “intellectual assets” have emerged as the prominent determinants of unique competitive advantage of firms. This is an implicit recognition of growing importance being placed on intangible assets (e.g. patents, trademark, trade-secret, reputation, brand, and loyalty…) on firms’ development. Not only does executing intellectual property management seem valuable and profitable for firms to seek, but also how to integrate physical assets with intangible assets into firms’ technological development, new product development, and market analysis is an emerging challenge for firms. It shows that “intellectual asset commercialization” doesn’t come from licensing, payoff through litigation only, but comes from properly combining business strategy, physical assets, and intellectual assets to get profit and growth. Knowledge-intensive companies are not selling knowledge alone; they make profits by putting business operation, product, and intellectual assets together. Even though firms who concentrate on designing, manufacturing, and selling tangible products, taking intellectual property management away from legal departments to top management decision making process will help firms understand the trends where firms operate, prevent from competitors’ disturbances.

This paper describes how a bike component firm (ranked the second position in world’s market share) competes against the dominant player through intellectual property strategies. Fierce competition makes two firms interact with each other’s strategies dynamically; it also illustrates the discriminating ways, these two players have been viewing their intellectual property management and some strategies they’ve utilized to get long-term growth with this new kind of perspective into business operation.

Intellectual property as an explicit strategic resource

With recognition of intellectual property rights, academic fields and business understand IPRs more and more, they felt it as a valuable asset, therefore, they devote huge resources to build an integrated unit to deal with IPR-related issues. From then on, patents or other forms of intellectual property rights become flourished; IPRs really represent an inseparable part of firms’ valuable assets. Although we found it important for firms to compete in next generation, firms systematically structure an integrated intellectual property platform to benefit firms’ growth in the future, through this mechanism, firms could understand how many “undervalued assets” they have. Although the challenges that firms face in assembling rights to outside

technologies have received little attention to date in management studies of innovation, technology transfer and merger and acquisition (M&A), they are the subject of considerable debate within the economics, legal, and public communities. In addition to strengthening intellectual property rights on firms’ core technologies to be free from disturbances of other competitors, IP related actions, in the past, are regarded as expensive and time-consuming, for instance, lively theoretical debate has emerged over whether strengthening patent rights promotes or hinders the innovation process. On one hand, the optimal patent design literature in economics emphasizes the importance of allocating strong patent rights to the first inventor in the cumulative chain to induce sufficient levels of R&D investments (Scotchmer, 1991). In contrast, other economists and legal scholars (Merges and Nelson, 1990) challenge these prescriptions and highlight the difficulties inherent in IP-related transactions: patents are inherently difficult to value, their boundaries are blurry and difficult to demarcate, and parties in the “cumulative chain of innovation” are often unknown in advance, which further restricts the range of application of their patented technologies. Patent legal system is a complicated mechanism which is hard to measure it in a precise quantitative method, because each country has somehow different examination process and treaties, firms can’t access all over the world through a granted patent in a specific country, they have to file their technologies in countries they want to sell, manufacture, license, etc. On the other hand, patent law is designed to promote and diffuse technologies useful to the publics quickly and reduce repeated R&D expense and times, different inventors may have similar ideas about the same technologies (e.g. in this paper, bike component: grip shifter is our focus), based on inherent technologies, inventors can modify the structure and patent it. Therefore, several debates and argument arise from how to efficiently patent technologies which are separated from different patent owners (patent assignees) or held by several owners. The public-goods nature of intellectual property and the uncertainty and costs associated with demarcating property boundaries add an important twist to this traditional hold-up problem. A patent, if valid, grants a patentee the right to exclude others from use of the patented invention for a limited period; it does not grant the patent owner the right to use the patented invention if such use infringes on the rights of others. That is, it is an exclusionary right, not an affirmative right. If a firm independently makes an invention and uses it to improve the quality of its products or production methods, the firm does not necessarily own the rights to “practice” or use its invention if doing so infringes on the patent rights of others. Depending on the extent to which simultaneous use and duplicative inventions are likely to occur, a firm may therefore face a make-or-buy decision in these markets for technology. Attention then shifts to the price a firm expects to pay in the event it needs to purchase legal rights to use technologies patented by others, and ways to improve its ex post bargaining position. In theory, a firm could simply invent around technologies owned by others and alleviate potential hold-up. Here, assumptions about the timing of investments and the feasibility and costs of ex ante contracting are critical. Consider, for example, the problem from the view of an innovative manufacturer. Suppose the firm could easily invent around an existing patent during the initial stages of designing new products. In this case, the royalties the patentee

could obtain from the firm would necessarily be limited, ex ante, by the manufacturer’s ability to invent around the invention (Levin et al. 1987, Teece 1986).

The manufacturer would be in a far weaker negotiating position, however, if it learns about the patent after embedding the technology in designs or processes that are costly or difficult to redeploy. At this point, the invention represents a highly specific asset (in the classic transactions cost sense) even though the identity of the asset holder was unknown prior to the investment decision.

In conclusion, inventors or assignees who own patents may not guarantee that firms could dominate the products or markets comfortably, because of profit-oriented, firms in the same industry would seek to survive and make profits aggressively and they would develop similar technologies and patent those, due to similarity, there are legal issues arising from infringement of patented technologies. However, in the surface, infringement seems to be lawful issues, which isn’t our interest here, what we want to know more is about how to transfer lawful issues into company’s future strategic actions far from the original intent that firms just stop competitor entering into markets not only by litigating on important technologies ex ante, but also strengthening technological leading by merging other key players in industry ex post. Through patent data consideration, we could understand firms that not only constraint competitors by litigation and get ransom, but also they want to build a complete structure and fence competitors in a competitive disadvantage condition.

Description of methodology, patent database, and limitations

Our primary data source is the USPTO (United Stated Patent and Trademark Office) database collected by Taiwan patent search company “Learningtech Company”, that contains utility patents granted from 1975 to the end of 2004 and citations from patent granted in 1975-2004. We use the address of the first inventor to identify the location of the invention and the name of his organizational affiliation (“assignee name”) to relate each patent to the corporation that owns it. We use this structure to construct patent data for these two companies (Shimano v.s. SRAM) during the period 1975-2004. A major drawback of this procedure is that it does not take into consideration changes in corporate structure due to mergers and acquisitions or important strategic changes that have occurred. However, analyzing these data helps us understand more why the one company could use its inherent technology to expand the business boundary out of simply shifting system, the other company may have to spend more getting rid of the disturbance from the incumbent firm.

Patent citations have the same disadvantages that patents have as an indicator of technological activity. The pros and cons of using US patents as an indicator of technological activity are well covered in the literature (i.e. Griliches, 1992, and Basberg, 1987), but two are particularly important for this study.

First, not all inventions are patented: firms can follow other means for appropriating the innovation benefits. But we contend that they are appropriate in exploring the innovation activity in the bike component sectors. Patents are more widely used than the alternative methods to protect the returns of R&D investments.

un-codified knowledge and therefore patent citations might not capture the transfer and development of tacit knowledge. One may assume, however, that codified knowledge flows of patent citations go hand-in-hand with more tacit aspects of knowledge flows through for example face to face contacts and scientists rotation(Almedia and Kogut, 1999 ; Verspagen and Schoenmakers, 2000).

Patents are only one form of intellectual property protection. Not all firms access technology via the process of invention and not all firms need to patent in order to appropriate the results of invention. Nevertheless, patents are useful as an indicator of innovation since many firms, and particularly those in high technology sectors, do rely on them to make their business decisions.

Patents provide a record of technology development across a broad spectrum of technology areas. Given the importance of the U.S. in the global marketplace, the U.S. patents system offers us the opportunity to compare our performance with that of other nations.

Patents have long been recognized as an important source of scientific and technical information. Some of their uses are: to evaluate a specific technology; identify alternate technology and its sources; refine an existing product or process; develop new products or process; solve a specific technical problem; assess a particular technical approach; and comprehend the state of the art and monitor development in a specific technology.

Citation searching provides for additional retrieval based on citation links rather than subject or indexing terms and may be used to

1. Enhance a prior art or patentability search - e.g., assist in retrieving the "unique" document supporting a validity search.

2. Analyze major competitors.

3. Monitor a patent portfolio for possible infringement.

4. Identify especially important intellectual property based on number of citations. 5. Assist in legal challenges.

Study background and results

We try to discuss the strategic interaction in bicycle shifting system competition between two major shifting system players in the world, it is imperative to include some information on the bike industry itself. The two market segments (bike components and bike manufacturing markets) have not always developed at the same pace, but each has had an effect on the development of the other. For this reason, this paper includes information about bicycles as well as bicycle shifting systems, in order to create a context to understand the “whole picture” better.

Bicycles have been around for a long time; some believe as early as the 15th century. But it was not until the 19th century that a vehicle resembling the bicycle we know today came into being. Since then, there have been many improvements, all affecting different aspects of the bike. These innovations have allowed the bicycle industry to prosper into a multi-million dollar market. In this market, there are thousands of independent dealers, hundreds of bicycle manufacturers, and several bicycle component manufacturers. All of these players are doing their best to provide

cyclists with equipment to meet their needs and riding habits. Within the component manufacturers, there is a giant named Shimano. Shimano has dominated the bicycle parts industry since the mid-1980’s. Yet, there are those who were and are undaunted by Shimano’s power in the marketplace. Companies like Campagnolo, SRAM, Sachs, and others, have survived or come into being in the same era that saw Shimano climb to the top of their industry. Others, like Suntour, have since disappeared, over-powered by Shimano’s ability to meet customers’ needs. What did companies like Campagnolo, Shimano, and SRAM do to stay in business and prosper? They innovated, they defined and met customer needs, they saw opportunities and exploited them, and they improved and simplified the bicycle shifting system in the process.

Although there are more than a few companies that make components for bicycles, only a handful can claim a significant share of the market. The three companies dealt with in this section are Campagnolo, SRAM and Shimano. Campagnolo has positioned itself in the high-end road bike component area. SRAM has taken a strong hold in the mountain bike component market. Shimano is positioned well in both the road and the mountain bike market.

Although Shimano is the most dominant players in bike shifting system, SRAM is positioned well in mountain bike shifting system segment, both of their shifting system have specific advantages over each other (Shimano’s famous product: trigger; and SRAM’s product is called grip shifter), SRAM has captured more than 50% of the mountain bike component market. Many of the following patents describe, in detail, the innovations in mountain bike shifting system that helped SRAM become so successful. Shimano saw the market potential in mountain bike component market and has devoted a lot of resources to develop similar type and function shifting system for mountain bike and got several patents in United States.

There is a notice of litigation (Shimano Inc., a foreign corporation, et al v. SRAM Corporation, Filed April 25, 1996, D.C. C.D. California, Doc. No. SACV 96-395) on U.S. Patent No. 4,900,291(assignee-at-issue SRAM). In this patent, Sam Patterson (patent inventor) discloses a bicycle gear shifting method and apparatus in this patent. The invention is a bicycle derailleur gear shifting system having a rotatable handgrip actuator cam (separate actuator cams are associated with the front and rear derailleurs) which is coupled with the derailleur shifting mechanism through a control cable system so as to control the derailleur mechanism. For the downshifting direction, the rear derailleur cam is configured to substantially compensate for the increasing force of the derailleur return spring to compensate for cumulative lost motions in the derailleur shifting mechanism and cable system, and for chain gap variations. This allows for over-shift of the chain sufficient to move beyond the destination sprocket, so that the chain will approach the destination sprocket in the same direction at it would in the up-shift direction, but not sufficient to cause a double shift, or derailing from the first sprocket. A front derailleur cam is configured to provide fine-tuning for “cross-over” riding.

This inventor in SRAM: Sam Patterson discloses a similar bicycle gear method and apparatus in U.S. Patent No.4,938,733 (assignee-at-issue SRAM), which is continuation-in-part of U.S. Patent No. 4,900,291. Although the basics are the same in

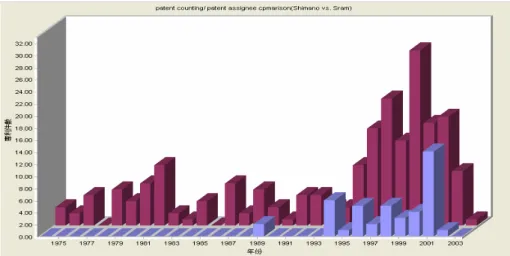

this patent, in one form of the invention, a secondary over-shift boost cam is added axially in tandem with the primary cam and is adaptable to both the front and rear derailleur shift actuators. U.S. Patent No. 5,102,372 (assignee-at-issue SRAM) also has a notice of litigation (SRAM Corporation v. Sunrace Roots Enterprise Co. et al, Filed August 30, 1996, D.C. N.D. Illinois, Doc. No. 96C5499). In the patent, Sam Patterson, John Cheever, and Jeffrey Shupe disclose a bicycle derailleur cable actuating system having a rotatable handgrip actuator cam which is coupled with the derailleur shifting mechanism through a control cable system to control the derailleur mechanism. We can find easily that Shimano has less advantageous than SRAM in mountain bike shifting system, though Shimano is stronger than SRAM all in all (see fig.1; Purple chart represents Shimano’s total patent, blue chart represents SRAM’s total patents).

Figure 1 comparisons patents granted by Shimano and SRAM (1975-2004)

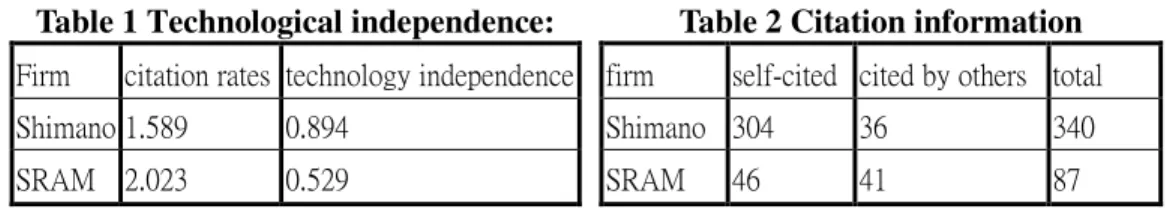

However, when we turn to patent qualitative analysis, we could find interesting that SRAM have better patent quality than Shimano in grip shifting system (table1 and 2).

Table 1 show that technological independence which means the extent that firms can develop their own technologies without considering other competitors’ technologies. The higher to 1, the more independent (see technology independence column), we could see that Shimano is more independent than SRAM in grip shifter, however, combined with other citation data, we found that SRAM’s citation rate is higher than Shimano (2.023 v.s. 1.589), from table 2, we could see that Shimano’s citations is more on self-citation, SRAM patents’ citation are cited by others. Therefore, if we analyze patent citation data from only one dimension, it will result in misleading analysis. Shimano has filed their technologies since 1974, and SRAM has started their business from 1984, on the other hand, technology independence is calculated by three parts (patent granted numbers, self-citation rates, cited by others rates), hence, patent granted numbers will be an important reference in technology independence calculation. SRAM has much less patents than Shimano in grip shifter system (Shimano has filed a lot of grip shifter from 1996, SRAM got first grip shifter

patent in 1990), SRAM has better quality than Shimano, so SRAM could claim Shimano infringe on SRAM’s technologies. From citation rate data (table 1 and table 2), we could find that over 50% citations in SRAM patents is cited by others (in this paper, there are two major players in grip shifting system, Shimano and SRAM), but Shimano patents focus more on self-citation.

Table 1 Technological independence: Firm citation rates technology independence

Shimano 1.589 0.894

SRAM 2.023 0.529

Table 2 Citation information firm self-cited cited by others total

Shimano 304 36 340

SRAM 46 41 87

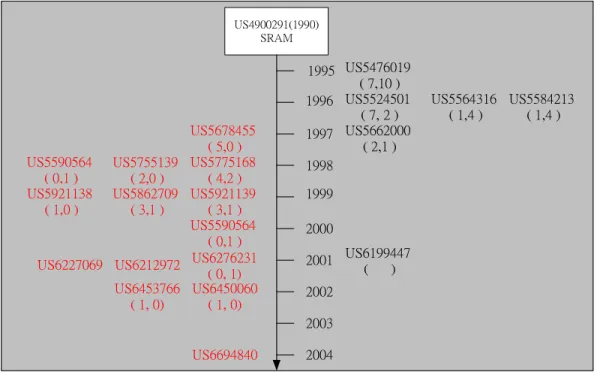

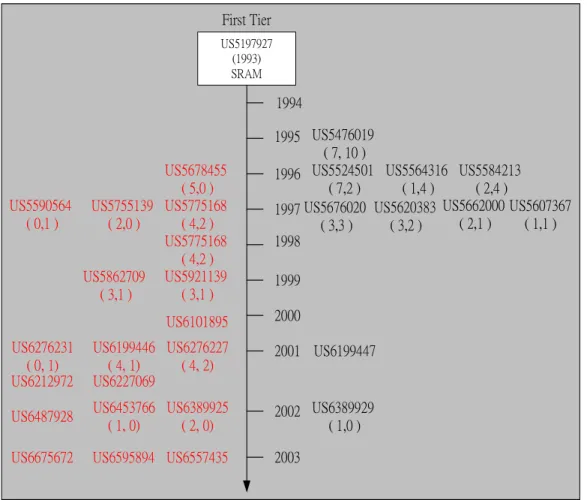

Based on citation analysis, we have interest on whether SRAM’s grip shifting technology has more advantage than Shimano’s, theoretically, one may think that the more patents, the better, in this case, we found it isn’t necessarily the truth, compared with these two bike shifting manufacturing companies, SRAM has 55 grip-shifting technology patents, and Shimano has 202 patents in grip-shifting technology. From technological innovation perspective, SRAM seems has first mover advantage on grip shifting technology. SRAM has not only started to develop grip shifting technology early, but also dominated such kind of shifting technology (see table 3), the first two patents (US4900291 and US5476019 granted to SRAM) is the most important grip shifting technology. They are cited most by Shimano to develop Shimano owned grip shifting technology. On the other hand, Shimano developed their grip shifting technology from 1996, they got several patents in next few years to design around SRAM’s patents.

SRAM used their superior technology in grip shifting technologies to lock Shimano in the middle and stop Shimano from entering into other component parts (such as suspension, brake and so on). During 1997-2000 periods, SRAM successfully utilize their patents to stop bike giant’s pace by litigation, and on the other hand, SRAM began to merge several important bike component firms all over the world to prevent from Shimano’s attack. In this period, SRAM merged an important component firm (Rock Shox: suspension manufacturing firms), however, owing to litigation, Shimano has focused more on designing around SRAM’s grip shifting technology.

Table 3 top 10 citation data (rank from high to low)

Patent number total citation Assignee Self-citation cited by others

US4900291 21 SRAM 7 14 US5476019 18 SRAM 2 16 US5012692 15 Shimano 0 15 US4325267 15 Shimano 5 10 US5203213 13 Shimano 12 13 US5676022 11 Shimano 9 11 US4470823 11 Shimano 10 11 US5458018 11 Shimano 11 11 US4343201 11 Shimano 11 11 US4938733 11 SRAM 11 11

Figure 2 first tier citation family (US 4900291); (left side: Shimano; right side: SRAM); this research

US4900291(1990) SRAM 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 US5476019 ( 7,10 ) US5524501 ( 7, 2 ) US5662000 ( 2,1 ) US5564316 ( 1,4 ) US5584213 ( 1,4 ) US5678455 ( 5,0 ) US5590564 ( 0,1 ) US5755139 ( 2,0 ) US5775168 ( 4,2 ) US5921139 ( 3,1 ) US5862709 ( 3,1 ) US5921138 ( 1,0 ) US5590564 ( 0,1 ) 2001 2000 US6199447 ( ) US6276231 ( 0, 1) US6212972 US6227069 2002 2003 2004 US6450060 ( 1, 0) US6453766 ( 1, 0) US6694840

Figure 3 citation family (US5197927) (left side: Shimano; right side: SRAM); this research

Summary

In conclusion, technology development needs more effort on understanding the context, competitors, and technologies, which helps firms free from other competitors’ disturbance and reduces the risks on R&D. Without figuring it out, firms will suffer a lot of resources. Therefore, intellectual property is not only a lawful tool, but also a useful strategic tool to investigate competitors’ actions and reactions. We think patent analysis may not restrict in patent data analysis only and patent analysis can expand to quantitative and text-reading process. This method could help firms know more about contents in patent data. Adding time frame in citation analysis could strengthen reliability of patent analysis data.

US5197927 (1993) SRAM 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 US5476019 ( 7, 10 ) US5524501 ( 7,2 ) US5678455 ( 5,0 ) US5590564 ( 0,1 ) US5755139 ( 2,0 ) US5775168 ( 4,2 ) US5775168 ( 4,2 ) US5921139 ( 3,1 ) 2000 1999 US6101895 2001 2002 2003 US6276227 ( 4, 2) US6199446 ( 4, 1) US6487928 First Tier US5564316 ( 1,4 ) US5584213 ( 2,4 ) US5676020 ( 3,3 ) US5620383 ( 3,2 ) US5662000 ( 2,1 ) US5607367 ( 1,1 ) US5862709 ( 3,1 ) US6276231 ( 0, 1) US6212972 US6227069 US6389925 ( 2, 0) US6453766 ( 1, 0) US6199447 US6389929 ( 1,0 )

Appendix ( full citation family): 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 1. 1. 1. 1. US5590564 1997 US5768945 1998 US5678455 1997 US6564671 2003 US6564671 2002 2. 2. 2. 2. US5775168 1998 3. 3. 3. 3. US6698307 2004 US6263754 2001 US6223621 1998 US6647823 2003 4. 4. 4. 4. US6484603 2002 US6263754 2001 US6453764 2002 US5862709 1999 US6513405 2003 US6564671 2003 US6553861 2003 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 US6553861 2003 US58350761 1998 US6694840 2004 US6332373 2001 US6453766 2002 US6431020 20002 US6557435 2003 US6487928 2002 US6675672 2004 US6389925 2002 US5941125 1999 US6450060 2002 US6691591 2004 US6694840 2004 US6681652 2004 US6453766 2002 US6331089 2001 US5921139 1999 US6584872 2003 US6595894 2003 US6675672 2004 US6694840 2004 US6675672 2004 5. 5.5. 5. US6487928 2002 US6557435 2003 US6389925 2002 US6276227 2001 US6675672 2004 US6675672 2004 US6557435 2003 6. 6.6. 6.

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 7. 7.7. 7. US6431021 2002 US6276231 2001 US6389925 2002 US6588296 2003 US661994466 2001 8. 8.8. 8. US5678455 1999 US5676020 1997 US6216553 2001 US6305237 2001 US6227068 2001 US6216553 2001 11. 11. 11. 11. US5988008 1999 US62282976 2001 US6510757 2003 US6332373 2001 US6604440 2003 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 US6370981 2002 US6332373 2001 US6647824 2003 US6394021 2002 US6675672 2004 US6557435 2003 9. 9. 9. 9. US6453766 2002 US6675672 2004 10. 10. 10. 10. 1995 1995 US5476019 1995 US5894759 1999 US5988008 1999 US6145407 2000 US6431020 2002 US6487928 2002 US6276227 2002 US6450060 2002 US6370981 2002 US6389925 2002 US6484603 2002 US6352486 2002 US6367347 2002 US6484603 2002 US6647824 2003 US6595894 2003 US6595894 2003 US6557435 2003 US6557435 2003 US6553860 2003 US6604440 2003 US6604440 2003 US6588296 2003 US6698307 2004 US6675672 2004 US6675672 2004 Same as NO.6 Same as NO.6 Same as NO.2

12. 12.12. 12. US6324938 2001 US6277044 2001 US6443027 2002 US5946978 1999 US6612950 2003 US6626060 2003 US6510760 2003 13. 13.13. 13. US5855529 1999 US6030307 2000 US5857932 1999 14. 14. 14. 14. US5607367 1997 US5674142 1997 US6443027 2002 US5620383 1997 US6282976 2001 US6315688 2001 US6352486 2002 US6588296 2003 US5564316 1996 US6389929 2002 US6615688 2003 US6101895 US6276231 2001 US6212972 US5524501 1996 15. 15. 15. 15. US66044402003 US5988008 1999 US6145407 2000 US6367347 2002 US5620383 1997 US5676020 1997 US6595894 2003 US5622083 1997 US6588296 2003 US6626060 2003 US6510760 2003 US5946978 1999 US5607367 1997 US6324938 2001 US6277044 2001 US6443027 2002 US6612950 2003 US5674142 1997 US5855529 1999 US6030307 2000 US5857932 1999 US6282976 2001 US6315688 2001 US6352486 2002 US6588296 2003 US6626060 2003 US6510760 2003

Reference:

Allansdottir, A., A. Bonaccorsi, A. Gambardella, M. Mariani, L. Orsenigo, F. Pammolli & M. Riccaboni (2002), “Innovation and competitiveness in European

biotechnology”, Enterprise papers,N. 7, Enterprise Directorate-General, European Commission.

Almeida, P. (1996), “Knowledge sourcing by foreign multinationals: patent citation

analysis in the U.S. semiconductor industry”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, Winter Special Issue, pp. 155-65.

Audretsch, D. & Feldman, M. (1996), “R&D Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation and Production,” American Economic Review, 86(4), pp. 253-273. Barney, J.B. (1986), “Strategic factor markets: expectations, luck, and business

strategy”, Management Science, 32 (10), pp. 1231-41.

Blair, M. Margaret. & Kochan, A. Thomas, (2001), “The new relationship: Human

capital in the American Corporations.” Brookings, Washington, D.C.

Davis, L., Julie, & Harrison, S., Suzanne, (2001), “Edison in the Boardroom: How

leading companies realize value from their intellectual assets.” John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Gassmann, O., & Zedtwitz, V. M., (1999), “New concept and trends in international

R&D organizations.” Research Policy, 28, 231-250.

Granstrand, O., (1999), “Internationalization of corporate R&D: a study of Japanese and Swedish corporations.’ Research Policy, 28, 275-302.

Kogut, B. & U. Zander (1993), “Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of

the multinational corporation”, Journal of International Business Studies, Fourth Quarter, pp.625-645.

Kortum, S., & Lerner, J., (1999), “What is behind the recent surge in patenting?” Research Policy, 28, 1-22.

Patel, P. & M. Vega (1999), “Patterns of internationalization of corporate technology: location vs. home country advantages”, Research Policy, 28, pp.145-55.

Patel, P. & Pavitt, K. (1999), "Global Corporations & National Systems Of Innovation: Who Dominates Whom?" in D. Archibugi, J. Howells and J. Michie (eds) Innovation Policy in a Global Economy, Cambridge University Press.

Rivette, K.G., & Kline, D., (2000) “Rembrandts in the Attic: Unlocking the Hidden

Value of Patents” Havard Business School Press.

Warshofsky, F., (1994), “The Patent Wars: The Battle to Own the World’s Technology” John Wiley and Sons, Inc.