教師自我效能感研究:以桃園縣本地國小英語教師為例 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Sense of Self-efficacy: A Study of Nonnative Public Primary Teachers in Taoyuan. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English, National Chengchi University. In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Hsiao-chun Huang July, 2013.

(3) Acknowledgments. First of all, I would like to thank all the elementary school teachers who took part in the survey. Without their participation, this thesis would not have been possible. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Ming-chung Yu for his inspiring guidance, support and belief in me throughout my research for this work. I also want to thank Dr. Jyh-sheng Lin and Mr. Sun-Lung Huang, for their reading of the draft and for their helpful suggestions and their statistical help in the survey data analysis stage. I am also deeply grateful to two elementary school teachers, Pei-chin Tsai and Mao-lung Huang who happens to be my brother for their insightful inputs in the instrument development stage and help in the data collection stage. Finally, words cannot express enough my thanks for my family for their help and support. Their unfailing love and help kept me up all the way through the work.. iii.

(4) Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………….iv List of Figures /Tables. ……………………………………………………………....vi Chinese Abstract…..……………………………...………..………….…...………..viii English Abstract……….…………………………………...………………..…….…ix Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………….…….…1 Background and Motivation………………………………………..…….………1 Purposes of Study…………………………………………………...…………...4 Chapter 2: Literature Review……………………………………………….................5 Conceptual Framework………………………………………..………………...5 Nature and Definition of Beliefs…………………………………………...5 Definition of Sense of Self-efficacy……………………...……...................7 Application of Sense of Self-efficacy in Education……...…........................8 Two Root Conceptual Theories of Teacher Self-efficacy………..................9 Measurement of Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy…………………………………..12 Concept of Cyclical Formation of Teacher Efficacy Beliefs.……………..12 Bandura’s Sources of Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs……………………...13 Previous Studies on Teachers’ Self-efficacy and EFL Domains…….................16 Contextual Factors and Background Variables …………..........................17 EFL Teachers’ Language Proficiency .…………………………………...20 Teachers’ Practices versus Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs…....................22 Students’ Achievements versus Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs.………...25 Phenomena of English Education in Taiwan ……………………………….....26 English Education Policy and Principles .……………………..…......…..26 iv.

(5) Channels of Recruitment of Primary EFL Teachers…….……..…...….....27 Difficulties in the Language Classroom of Primary Schools ….……….....28 A Missing Link to Teachers Self-Efficacy ……….………….….………...……29 Research Hypotheses………………………...….…………….…………...…..30 Research Questions……………………….….…………….…………...…31 Chapter 3: Methodology…………………………...….…………….…………...….33 Research Structure…………………………...….…………….…………...…..33 Participants……………………………………….…………….…………...….34 Instrument. ……………………………………...….………….…………...….35 Pilot Study ……………………………………...….……………………...…...44 Data Analysis…………………………………...….………….…………...…...45 Research Procedure……………………………...….………….…………...….46 Chapter 4: Results…………………………………...….…………….………...……49 Research Question 1…………………………...….…………….………...…….49 Research Question 2…………………………...….…………….………….…..58 Research Question 3…………………………...….…………….………...……70 Chapter 5: Discussion …………………………...….…………….…………...….…75 Levels of EFL Teachers’ Self-efficacy and Teachers’ Language Proficiency, and their Pedagogical Strategies in Taoyuan ……………..…………………….......75 Effects. of. Antecedents. on. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy. and. Pedagogical. Strategies……………………………………………..…………………………82 Relationships among EFL Teachers’ Self-Efficacy, Language Proficiency, and Pedagogical Strategies ........................................................................................92 Chapter 6: Conclusions ...............................................................................................99 Summary of Major Findings ...............................................................................99 v.

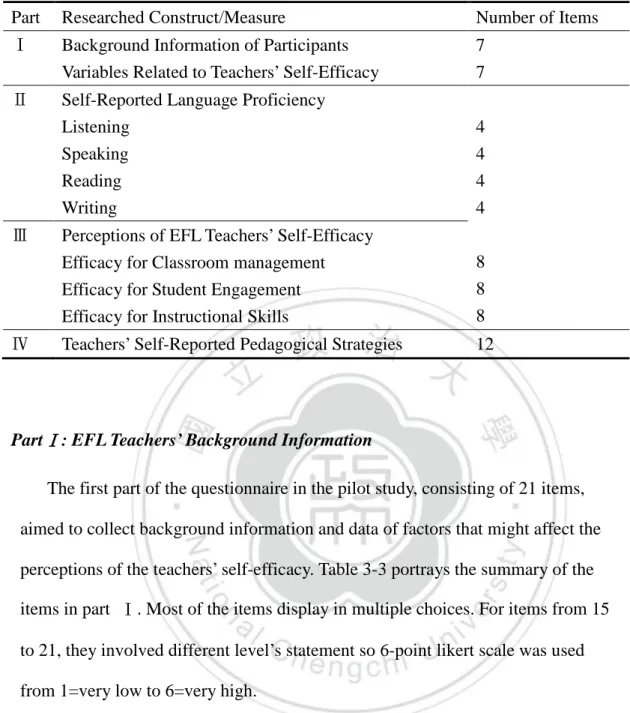

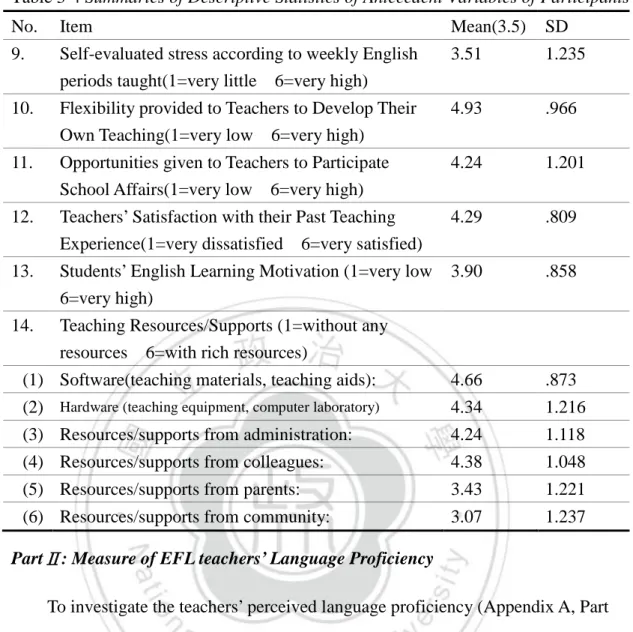

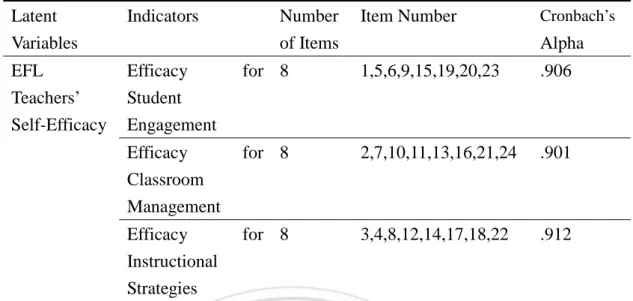

(6) Theoretical Implications ...................................................................................100 Pedagogical Implications ..................................................................................100 Limitations of the Study ....................................................................................102 Suggestions for Future Studies .........................................................................103 References .................................................................................................................104 Appendixes ...............................................................................................................115 A: Formal Questionnaire (English Version) ......................................................115 B: Pilot Questionnaire (English Version) ..........................................................120 C: Formal Questionnaire (Chinese Version) .....................................................125 D: Pilot Questionnaire (Chinese Version) .........................................................130 E: The Data of Correlation Analyses ................................................................135 List of Figures/Tables Figure 2-1 Triadic Reciprocal Causation Model ...........................................................8 Figure 2-2 The Conditional Relationships between Efficacy Beliefs and Outcome Expectancies .............................................................................................11 Figure 2-3 The Cyclical Nature of Teacher Efficacy...................................................13 Figure 2-4 Hypothesized Causal Model......................................................................30 Figure 3-1 Research Structure.....................................................................................33 Figure 3-2 A Flowchart of the Research Procedures...................................................47 Table 3-1 Summary of Descriptive Statistics of Background Information of Participated Teachers in the Formal Study...................................................35 Table 3-2 Distribution of the Items in the Questionnaire............................................38 Table 3-3 Summary of Background Information and Measure of Variables of Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in the Pilot Study...................................................39 Table 3-4 Summary of Descriptive Statistics of Antecedent Variables of Participants...................................................................................................41 Table 3-5 Summary of the EFL Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Measure..............................43 vi.

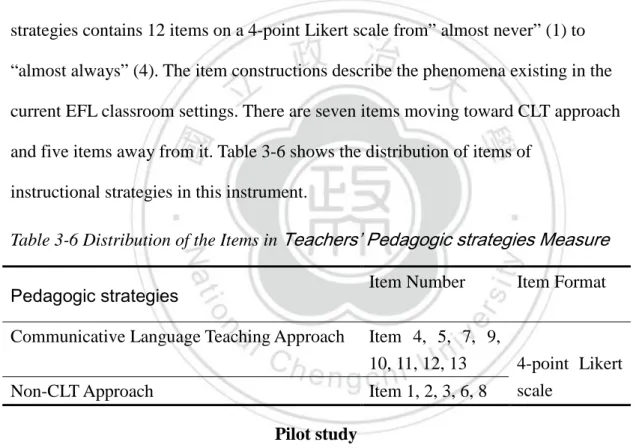

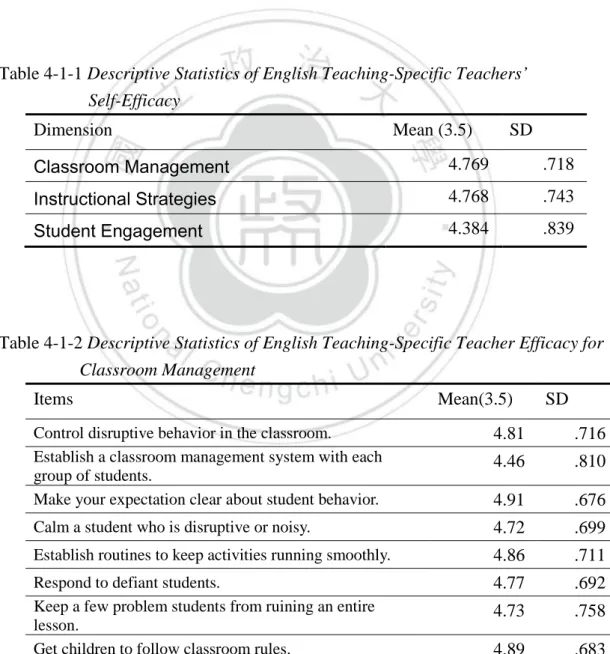

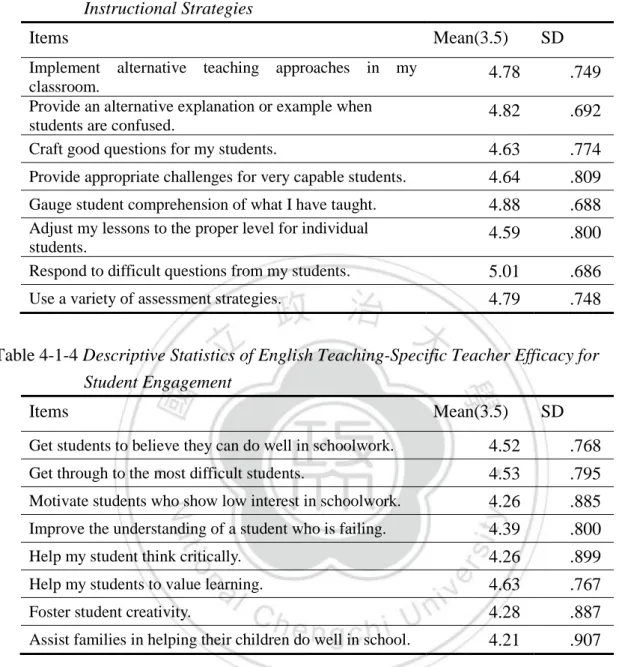

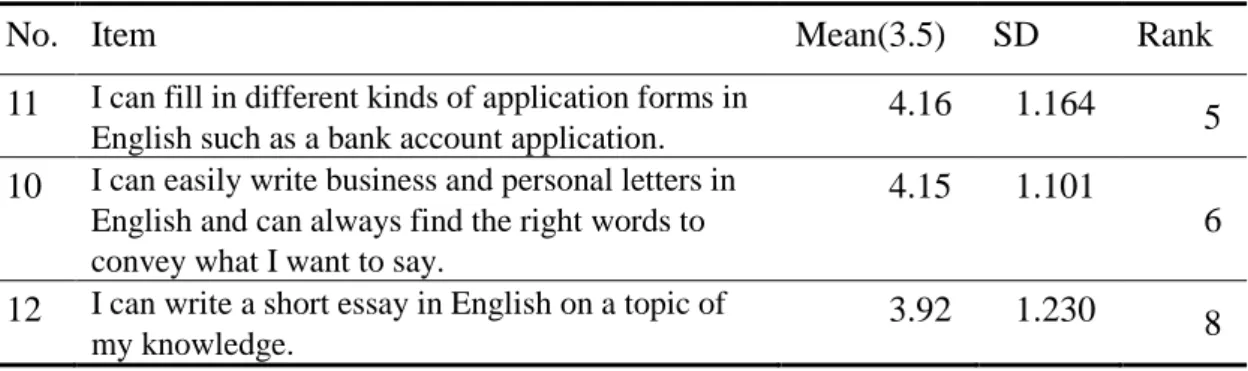

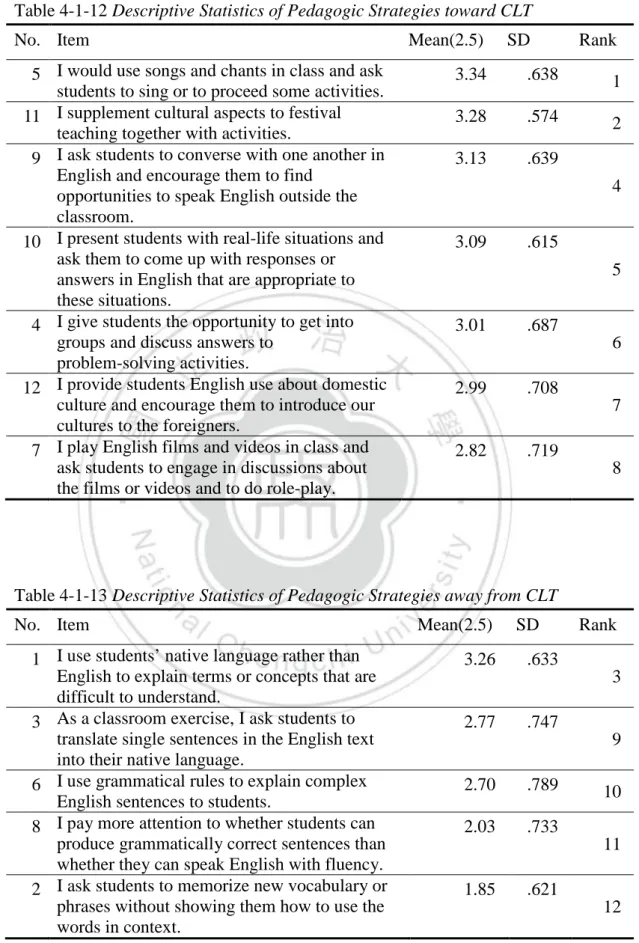

(7) Table 3-6 Distribution of the Items in Teachers’ Instructional Pedagogies Measure........................................................................................................44 Table. 4-1-1. Descriptive. Statistics. of. English. Teaching-specific. Teacher. Self-Efficacy................................................................................................51 Table 4-1-2 Descriptive Statistics of English Teaching-specific Teacher Efficacy for Classroom Management..............................................................................51 Table 4-1-3 Descriptive Statistics of English Teaching-specific Teacher Efficacy for Instructional Strategies.................................................................................52 Table 4-1-4 Descriptive Statistics of English Teaching-specific Teacher Efficacy for Student Engagement....................................................................................52 Table 4-1-5 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ Language Proficiency........................54 Table 4-1-6 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ English Reading Proficiency.............54 Table 4-1-7 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ English Listening Proficiency...........54 Table 4-1-8 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ English Speaking Proficiency...........54 Table 4-1-9 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ English Writing Proficiency..............55 Table 4-1-10 Descriptive Statistics of Teachers’ Self-reported Language Abilities....55 Table 4-1-11 Descriptive Statistics of Orientations of Pedagogic Strategy.................56 Table 4-1-12 Descriptive Statistics of Pedagogic Strategies toward CLT...................57 Table 4-1-13 Descriptive Statistics of Pedagogic Strategies away from CLT.............57 Table 4-2-1 Summary of Multiple Regression Analyses of the Effect of Antecedents on Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Pedagogic Strategies toward CLT............64 Table 4-2-2 The Independent Sample T-test Results for the Comparison between Male and Female Teachers’ Orientation toward CLT..........................................65 Table 4-2-3 The Independent Sample T-test Results for the Comparison between Voluntary and Involuntary Teachers on Research Variables......................67 Table 4-2-4 The One-way ANOVA Results for the Comparison among G1 (0~3 years’ experience), G2 (3~10 years’ experience), and G3 (above 10 years’ experience) on Research Variables............................................................69 Table 4-3-1 Summary of Pearson Correlation Analyses of Research Variables..........73 vii.

(8) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱: 教師自我效能感研究--以桃園縣本地國小英語教師為例 指導教授: 余明忠 博士 研究生: 黃曉君 論文提要內容: 本研究旨在調查桃園地區英語教師之教學效能感,且探究英語教師本身 英語能力、面對的環境、學校、學生等因素對其教學效能感和英語教學策略 的影響。 本研究以問卷調查法進行,對象為桃園縣 188 所公立小學的 542 名英語 教師為主。依層級抽樣法,正式問卷發出 460 份,收回有效問卷 384 份,收 回率達 83.5%。問卷回收後資料以統計軟體 SPSS 18.0 進行敘述性統計、多 元迴歸、皮爾生相關係數分析、獨立樣本 t 考驗、單因子變異數分析及薛費 事後法分析,獲得結果簡述如下: 1.桃園縣英語教師之教學效能感普遍呈現中上趨勢。 2.英語教師之英語能力以英語閱讀能力最好,口說與聽的能力較弱。 3.教學上,教師偏向溝通式教學法。 4.所有影響教師效能感的因素中,教師過去的成功經驗最具正面影響力。 5.負面的情緒(例如:過多的壓力、有違意願的課堂安排)有損教師效能感。 6.教師教學效能、英語教學法運用因本身英語能力的影響,呈現正向的關係。 根據問卷調查結果,本研究最後提供教學上相關建議以供參考。. viii.

(9) Abstract. This study aims to explore self-efficacy, English language proficiency, the proclivity of their pedagogical strategies and their relationships among the elementary school EFL teachers in Taoyuan.. The questionnaire survey method has been. employed, and based on stratified sampling method, there were 384 teachers involved in this research (response rate 83.5%). The results show: 1. The EFL teachers rated their self-efficacy in teaching English at a moderate level, their teachers’ self-reported language proficiency best in receptive skill—reading, proclivity of pedagogical strategy in language class toward CLT approach. 2. Among the 13 antecedents checked, Master experience was found to be the most powerful factor to influence teachers’ efficacy formation. Students’ learning motivation plays a significantly reciprocal impact on teachers’ efficacy beliefs in general, efficacy for student engagement, and teachers’ aptitude to employ CLT approach in their classroom. 3. Finally, the higher proficient the teachers rated themselves the more efficacious they felt in teaching English and in employing communicative language teaching approach. The suggestions were provided in the end of the study with an aim to help the teachers understand better about their self-efficacy beliefs and the concerned trainers design more suitable teacher training programs for the elementary EFL teachers.. ix.

(10) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Background and Motivation Elusive as the phenomenon of second language acquisition (SLA) may still be (Brown, 2007), in a second language classroom two main domains cannot do without; that is, the teacher and the leaner. The quality of education is the reflection of teachers’ qualification; lack of qualified teachers results in poor quality of education. The standard of teachers’ quality should be advanced over time so that education could also be improved accordingly. In addition, much research also found that teachers shoulder the key to the success of education reforms. In this light, it is crucial to understand teachers’ perceptions and beliefs because teachers not only are deeply involved in daily teaching and learning processes but serve as practitioners of educational principles, theories and policies (Jia, Eslami & Burlbaw, 2006). Every day teachers, based on their beliefs, make tons of decisions pertaining what is needed or what would work best for their students. Discoveries from past research and beliefs showed that these perceptions and beliefs not only impact considerably on teachers’ instructional practices and classroom behaviors but also are associated with their students’ performance (Grossman, Reynolds, Ringstaff & Sykes, 1985; Hollon, Anderson & Roth, 1991; Johnson, 1992; to name just a few). Therefore, knowing the perceptions and beliefs of teachers enables one to make predictions about teaching practices and to assess the outcomes of those practices in 1.

(11) classrooms. Derived from social learning theory (Bandura, 1997), teachers’ self-efficacy, indicating teachers’ beliefs about their own effectiveness, “holds up many important instructional decisions, including classroom management, student engagement, and instructional skills, which ultimately influence students’ learning experiences” (Soodak & Podell, 1997, p. 214) and even shape up their self-efficacy. Several studies (Chang, 2010; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998; 2001; 2007) have shown that teachers’ self-efficacy as an incentive would directly affect how much labor and time teachers are willing to put into preparation and delivery of instruction, what objectives they set, how much they are willing to adopt creative methods to help students to learn, and how persistent and resilient they are when dealing with predicaments. When a teacher has higher self-efficacy, he/she carries greater enthusiasm and commitment toward his/her job and he/she will stay longer in the field of education. However, not enough research had been done in the settings of teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). Since the advent of conceptual notion of self-efficacy from social learning theory, some research has been done to inspect teachers’ self-efficacy in other subjects and academic disciplines such as math (Chan, 2007), science (Narayan, 2010), physical education (Huang, 2008; Marcelo et al., 2010), nursery and special education (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). For the first few decades, efforts had been put to figure out the definition of self-efficacy theory and to develop the measure of self-efficacy. Then, responding to the context-bound and subject-specific feature of Bandura’s (1996) self-efficacy theory, some researchers had explored the potent antecedents and contextual factors affecting teachers’ self-efficacy, and investigated the consequences of teachers’ self-efficacy. However, few data can be 2.

(12) found on language teachers’ perceived self-efficacy, let alone the context of teaching English as a foreign language in Taiwanese primary schools where English education was just implemented not long ago. Given the powerful impact of self-efficacy on teaching practices and student learning, it is crucial to pursuit the inquiry in this line of the field. After looking further into the studies on the effect of antecedents and subsequences of teachers’ self-efficacy, the researcher found that quite a few of them centered the targets on pre-service, novice or experienced teachers in middle and vocational schools (Eslami & Fatahi, 2008; Chang, 2010). Not enough research was done on getting the picture of teachers’ perceived self-efficacy at the primary school level. Because the educational system and the requirements of teachers between primary and vocational schools are quite different, it is not appropriate to generalize the findings derived from the previous research to primary school settings. Therefore, the researcher is motivated to conduct this current study in order to discover primary EFL teachers’ perceptions toward their capability to teach EFL classes. Furthermore, due to the implementation of English education at earlier age, the number of nonnative English speaking teachers (NNESTs) has increased considerably over the last decades. Unavoidably, NNETs also become an important issue of research and pedagogical interest in applied linguistics. Consequently, their English language proficiency increasingly catches attention (Butler, 2004; Eslami-Rasekh, 2005; Nunan, 2003). Earlier research (Chang, 2010; Samimy & Brutt-Griffler, 1999) showed English language proficiency not only forms a factor of EFL teachers’ self-efficacy but is also related to teacher confidence and pedagogic choice in instructing students. Butler’s (2004) survey revealed the primary EFL teachers’ self-evaluated oral language proficiency in Korea, Taiwan and Japan was 3.

(13) not good enough to implement mandated communicative language approach. Yet, little research can be found in Taiwan concerning this issue. Although language proficiency is often listed as an area of interest in many papers (Medgyes, 1994; Reves & Medgyes, 1994; to name just a few), there are still not enough data exploring NNETs English proficiency and its relationship with their EFL pedagogical strategies in Taiwanese EFL classroom settings. Since EFL teachers’ language proficiency directly influences their teaching practices and pedagogical preference, it is worthwhile to conduct this research to supplement the research gap. Purposes of the Study In light of the abovementioned discussion and concerns, this study aims to (a) find out what the current primary EFL teachers’ perceived self-efficacy, self-reported language proficiency and their pedagogic strategies are in English as a foreign language (EFL) classes; (b) display the effect of the antecedents on teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and pedagogical choice; (c) present the relationships among the research variables, namely teachers’ self-efficacy, their language proficiency and pedagogical strategies.. 4.

(14) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Self-efficacy beliefs can be categorized under the umbrella of beliefs in general, so this chapter goes through the related literature on the following four bodies: 1) teacher beliefs and conceptual roots of self efficacy beliefs, 2) measurement of teachers’ sense of efficacy, 3) previous research related to teachers’ sense of efficacy, and 4) English education in Taiwan. In the end, the research hypotheses and questions are presented accordingly. Conceptual Framework Just as current decides boat’s direction, so human beings’ behaviors are guided by their beliefs. So, it is very important to throw light on what beliefs stand for, where self-efficacy stems from, how self-efficacy influences teachers’ practices, and how it can be put to use in education field. Nature and Definition of Beliefs Beliefs are connected to human behaviors and learning. They are one of the vital issues of all fields in education (Ajzen, 1988; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Since the development of cognitive psychology, study of beliefs has received its mass popularity in various fields as well as in education. Teachers’ beliefs are regarded as one of the essential factors to teaching effectiveness (William & Burden, 1997). Furthermore, teachers’ knowledge and beliefs provide the underlying framework or strategy which guides the teachers’ classroom action (Richards & Lockhart, 1996). Kagan (1992) concluded that beliefs may be “the clearest measure of a teacher’s 5.

(15) professional growth” and that studying them is “instrumental in determining the quality of interaction one finds among teachers in a given school” (p.85). Therefore, the agreement in general education studies is that teaching is a cognitive activity and that teachers’ beliefs strongly influence their instructional decision in the classroom (e.g., Shavelson & Stern, 1981; Tillema, 2000). Teacher beliefs are not easy to define because they are not directly observable. Based on Oxford Advanced Learner Dictionary (Wehmeier & Ashby, 2000), belief is defined as (1) a strong feeling that something is true or somebody does exist; confidence that something or somebody is good, right or wrong, (2) an idea about something that you are certain is true, especially involving religion or politics. In another word, belief means that one firmly believes in certain things or propositions and accepts them without precondition. Kagan (1992) inferred that teacher beliefs were composed of tacitly held assumptions and perceptions about teaching and learning. Hampton (1994) further pointed out that teacher beliefs are stable in general and mirror the nature of the instruction a teacher provides to students. Johnson (1994) proposed three common assumptions that educational research on teachers’ beliefs share: (1) Teachers’ beliefs affect perception and judgment. (2) Teachers’ beliefs play a part in how knowledge on teaching is turned into classroom practices. (3) In order to improve teaching behaviors and teacher education programs, it is very crucial to understand teachers’ beliefs (p. 439). Other researchers (Al-Sharafi, 1998; Puchta, 1999) who tried to pinpoint the development of beliefs indicated that beliefs were developed through the culture we lived in, through the repetitive experiences and interactions in daily life, and through the modeling of significant others as children did. Once set, beliefs became a kind of evaluation and judgment toward the outside world. 6.

(16) Definition of Sense of Self-Efficacy Sense of self-efficacy is a sub-scale of teacher beliefs and regarded as “a cognitive process in which people construct beliefs about their capacity to perform at a given level of attainment” (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998, p.203). Grounded on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), people’s judgments about their abilities to successfully perform a specific task take shape through dynamic, continuous and reciprocal interactions between personal, behavioral and environmental factors, which is depicted in Figure 2-1. These judgments highly “influence how much efforts people put forth, how long they are willing to persist in the face of obstacles, how resilient they are in coping with failures and how much stress or anxiety they experience in dealing with demanding situations” (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998, p.203). According to Bandura (1997), unless people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentives to act. Bandura stated that self-efficacy is different from other constructs such as self-concept and self-esteem. Unlike self-concept, which is regarded as “a composite view of oneself that is presumed to be formed through direct experience and evaluations adopted from significant others” (Bandura, 1997, p. 10), self-efficacy beliefs vary according to the domain of activities, the levels of difficulty, and the specific context. For example, one who has high efficacy beliefs in field sports may have low efficacy in biking, but such kind of domain specificity does not necessarily work on the global nature of self-concept. Also, self-efficacy beliefs predict “the goals people set for themselves and their performance attainments, whereas self-esteem affects neither personal goals nor performance” (p. 11). All these domain- and context- specificity features make self-efficacy different from other 7.

(17) global constructs of self-concept and self-esteem.. Application of Self-Efficacy in Education Perceived self-efficacy has significant influence on different aspects of teaching and learning process (Pajares & Urdan, 2006). Many studies have shown that sense of self-efficacy, as “a strong predictor of behaviors” (Bandura, 1997, p.2), would influence the whole educational system throughout the process of development and implementation of different policies of teaching (Goddard & Goddard, 2001; Friedman & Kass, 2002). Different definitions of teachers’ self-efficacy given by various researchers can be summarized as the combination of teacher’s perceived abilities to successfully play specific tasks of a teacher in a particular context and to effectively instill desired behaviors, skills and competencies in students (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998). In a classroom context, whatever subject it might be, no one would deny that a teacher’s goal was to have students acquire successfully desired knowledge, skills, capabilities with approved behaviors and pleasant attitudes. To reach this ideal, many factors, involving learning and teaching, had to be examined. However, this current research just focused on the teacher’s side, exploring teachers’ self-efficacy, the antecedents of teachers’ self-efficacy and EFL teachers’ subject competences, 8.

(18) namely language proficiency and EFL pedagogic strategies in this case. Before more related studies are reviewed, the very first two conceptual strands of theory and research that first constructed teachers’ self-efficacy and inspired so much entailed research should be looked into, that is, Rotter’s social learning theory and Bandura’s social cognitive theory. Two Root Conceptual Theories of Teachers’ self-efficacy RAND researchers (Armor, et al., 1976) motivated by Rotter’s (1996) article entitled “Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External Control Reinforcement” adopted its social learning theory as its theoretical foundation. By conducting a simple measurement consisting only two items, Rand researchers depicted teacher efficacy as “ the extent to which teachers believed that they could control the reinforcement of the actions whether control of reinforcement lay within them or in the environment” (Tschannen-Moran et al., 2001, p.784). In this light, teachers with a belief of external control consider that environment overpowers a teacher’s ability to affect students’ learning and performance. On the other hand, teachers with internal control have great confidence in teaching and believe their own competence can influence students’ learning and even reach to those students with learning difficulty and low motivation (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998). In another word, teachers hold the key of reinforcement of teaching efforts. The two items on the questionnaire survey sheets to be rated by participants’ level of agreement are as follows: Rand item 1. “When it comes right down to it, a teacher really can’t do much because most of a student’s motivation and performance depends on his or her home environment.” Rand item 2. “If I really try hard, I can get through to even the most difficult or 9.

(19) unmotivated students.” Bandura’s social cognitive theory, on the other hand, formed the second conceptual strand of teacher efficacy. Delineated in Bandura’s 1997 article, entitled “Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”, teacher efficacy was regarded as a type of self-efficacy. As stated in length in previous section of definition, self-efficacy beliefs claimed by Bandura (1986, 1993, and 1997) would exert influence on one’s drive, thinking patterns, and affective aspects by which people decide how much labor they would devote to the pursuit of goal, how long they would persist in face of difficulty and how much achievement they could realize. Together with efficacy expectation mentioned above, outcome expectancy is also disclosed in Bandura’s social theory. The former emphasizes individual’s belief about the level of capacity a person has when conducting and getting a specific task done at a desired level, the latter focuses on individual’s belief about “ the likely consequences of performing the task at the expected level of competence” ( Bandura, 1986, as cited in Tschannen-Moran et al., 2001, p.787). Bandura (1997) further clarified that efficacy expectation proceeds usually before outcome expectancy and impacts to form outcome expectancy in some ways. Efficacy expectation dwells on teachers’ beliefs about “whether behaviors can be performed” (Dellinger et al., 2008, p.753), whereas outcome expectation centers on beliefs in “whether certain behaviors lead to certain outcomes” (Dellinger et al., 2008, p.753). Bandura (1986) also claimed that outcome expectancy carried little predictive function of efficacy measures. Figure 2-2 depicts the relationship of these two factors. Since the purpose of the present study was to understand the relationship between Taoyuan county’s primary EFL teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and their actual teaching practices, the 10.

(20) research focus was limited to the exploration of self-efficacy beliefs rather than outcome expectancies.. PERSON. BEHAVIOR EFFICACY BELIEFS. OUTCOME. OUTCOME EXPECTANCIES. Figure2-2. The conditional relationships between efficacy beliefs and outcome expectancies (Adopted from Bandura, 1997, p.22) The two abovementioned conceptual theories of teacher efficacy are different in terms of the construct definition. According to Bandura (1997), perceived self-efficacy focuses on teachers’ beliefs in their abilities to carry out certain tasks. On the other hand, internal-external teacher efficacy basically centers on “teachers’ beliefs in their abilities to affect student performance” (Dellinger et al., 2008, p.753). That is, self-efficacy deals with the issue of teachers’ individual efficacy but teacher efficacy mainly dwells on “causal beliefs about the relationship between actions and outcomes” (Tschannen-Moran, 1998, p.211). For instance, a teacher who believes he holds the power over the outcomes of students’ performance, i.e. internally controlled, may still have little confidence in his ability to perform certain actions in a given context (Tschannen-Moran, 1998). From this light, perceived self-efficacy is claimed to have stronger predictive power of behaviors in comparison with Rotter’s teacher efficacy (Tschannen-Moran, 1998). Dellinger et al. (2008) further clarified the discrepancies between teacher efficacy and teachers’ self-efficacy by stating that teacher efficacy limits the crucial role of teachers’ beliefs to only the capability to successfully influence students’ performance, a production stemming from teaching behaviors and learners’ behaviors. Teachers’ self-efficacy is a judgment about teachers’ competence to 11.

(21) complete the various tasks required in teaching contexts. Since the notion of Bandura’s self-efficacy meets the current research focus, the efficacy construct and measurement developed in this study adopted Bandura’s conceptual theory and term about teachers’ self-efficacy. Measurement of Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy A complete measurement of teachers’ self-efficacy should include outer contextual elements, inner personal competences, and visible consequent outcomes so as to find out their causal relations and to bring out constructive suggestions. Concept of Cyclical Formation of Teacher Efficacy Beliefs Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998) made a great contribution to clear up the conceptual confusion of teacher efficacy by presenting the cyclic model (Figure 2-3) that organized the conceptual strands of theory in more systematic way. The significant value about this model is its framework for related research in teacher efficacy field. Thereupon, teachers’ self-efficacy serves as a mediator. After that, more and broader studies could be conducted, such as the relationship between antecedents of efficacy beliefs and teacher efficacy and the relationship between teacher efficacy and teacher’s their reflected teaching behaviors in classroom (Ross, 1998). The research scope even reached to the domains of mental and psychological states, such as their perseverance, emotional responses, as well as job burnout.. 12.

(22) The components displayed in this model are closely related and are intertwined. Hence, the cyclic nature of teacher efficacy is formed. The formation of teacher efficacy beliefs proposed by Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998) is mainly built upon two aspects. They are the analysis of a particular teaching task with the resources and limitations in a certain teaching context taken into account, and the teacher’s assessment of personal teaching competence. In this light, a well-constructed instrument of teacher efficacy should contain these two parts. The latest research in Tschannen-Moran et al. (2007) stated that the assessment of the teaching task requirements should include the resources available, student factors such as their perceived ability, motivation, and socioeconomic status, and contextual factors such as school leadership, administrative support, and the availability of resources. Bandura’s Four Sources of Teachers’ self-efficacy Beliefs After Bandura’s (1997) assertion that teachers’ self-efficacy is subject-specific and context-oriented, there have been plethora of research concentrating on measuring teacher efficacy in specific subjects and under different contexts related to teachers’ self-efficacy (Bayraktar, 2011; Betoret, 2009; Chong et al., 2010; Palmer, 13.

(23) 2006; Siwatu, 2011; to name but a few). Many of them based on Bandura’s (1986, 1997) claim that four sources have influence on people’s beliefs about their efficacy—enactive mastery experiences, verbal persuasion, vicarious experiences and physiological arousal. When handling information from the four sources, one first selects “the types of information he/she attends to and uses as indicators of personal efficacy” (Labone, 2004, p. 343), and second, “weight and integrate efficacy information in forming personal efficacy beliefs” (p. 343). The four sources are elaborated as follows. Mastery experiences, the extent of a teacher’s satisfaction with his or her past professional performance, have been claimed to be the strongest source of self-efficacy judgments for teachers (Bandura, 1997; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998). It is claimed that success builds a robust belief in one’s personal efficacy and that failure undermines it. Therefore, teachers who perceive their past performance a success tend to have stronger self-efficacy beliefs. On the other hand, teachers carry lower self-efficacy beliefs if they regard their past performance a fail. In Tschannen-Moran and Hoy’s (2007) study, it is found that teachers’ interpretations of their past experiences were moderately associated with teachers’ perceived self-efficacy for both novice and experienced teachers. Gorrell and Capron (1990) has shown that experiences during student teaching influence the development of teachers’ efficacy and that the student teacher’s mentor and cooperating teachers’ role in their supervision also play a significant part in the development of teachers’ efficacy. Verbal persuasion is interpreted as “verbal interactions that a teacher receives about his or her performance and prospects for success from important others in the teaching context, such as administrators, colleagues, parents and members of the 14.

(24) community at large” (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007, p.945). Whether the feedback is given formally or informally, both have been claimed to have impacts on teachers’ self-efficacy and the subsequent performance to some degree. In Tschannen-Moran and Hoy’s study (2007), they explored how various forms of verbal persuasion, such as interpersonal support from administrators, colleagues, parents and the community, influenced novice and experienced teachers’ self-efficacy. The results revealed that none of the verbal persuasion variables contributed to experienced teachers’ self-efficacy; only the support from colleagues and the community was linked to novice teachers’ self-efficacy. However, it is worth noting that the power of verbal persuasion for teachers’ judgment of their capacities may differ in some ways due to “the credibility, trustworthiness and expertise” (Bandura, 1986, as cited in Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998, p.230) the persuader reveals during the interaction. The third source is through vicarious experiences provided by social models. Vicarious experiences refer to the experience of observing other teachers modeling a target activity. Bandura (1997) stated that observing people succeed in task by sustained effort increases observers’ beliefs that they can also command the capabilities to achieve similar activities. The effect of the modeled performances on observers’ self-efficacy beliefs is determined by “the degree to which the observer identified with the model” (Bandura, 1997, as cited in Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007, p.945). In another word, the more closely identified the model is to the observer in terms of gender, training and professional experience, the stronger impact there is on teacher’s efficacy beliefs. Otherwise, there is little impact on teacher’s self-efficacy beliefs if the model should be considered relatively different from the observer in many ways. In empirical studies, modeling is detected as a powerful tool in forming pre-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy (Labone, 2003; 15.

(25) Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998). And finally, Bandura’s fourth source of teachers’ self-efficacy is physiological arousal, the self-beliefs of efficacy to reduce people’s stress reactions and to alter their negative emotional inclination and interpretations of their physical states. Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998) state, “high levels of arousal can impair functioning and interfere with making the best use of one’s skills and capabilities,” while “moderate levels of arousal can improve performance by focusing attention and energy on the task” (p. 219).That is, pleasure or depression teachers experience during their teaching is claimed to have an influence on teachers’ perception of their individual competence. The happier and more satisfied a teacher feel about his or her teaching, the more his or her positive judgment of capabilities will be boosted. In contrast, a sense of anxiety and depression will undermine teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Three of the abovementioned sources were used as the criteria of the antecedents in the research after the features of the participants in this study were taken into account. They are mastery experiences, verbal persuasion and physiological arousal. Only vicarious experiences were not included due to the rare chance of happening and the participants’ tight instruction schedule in the EFL primary settings. Previous Studies on Teachers’ Self-efficacy and EFL Domains A teacher is not an isolated organ in the society. On the contrary, teachers are living human beings who not only actively interact with the outside environments but change their behaviors and perceptions, if necessary, to respond to the contexts. Based on social cognitive theory, personal factors (including self-efficacy beliefs) and behaviors interact with the environments to influence one another through a 16.

(26) reciprocal process. Thus, it would be instructive to examine reciprocal relationships between school contexts and teachers’ self-efficacy with personal backgrounds taken into consideration. The following reviewed literature displayed how different factors increased or decreased teacher’s self-efficacy. Contextual Factors and Background Variables Some contextual factors weaken teachers’ self-efficacy. Webb and Ashton (1987) in a teacher interview found a number of factors that seemed to diminish teachers’ sense of efficacy. These included excessive role demands, poor collective morale, low status, inadequate salaries, and lack of identity recognition. Furthermore, in-field professional isolation, job uncertainty and relationship alienation also tended to weaken teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Other studies (Ross, Cousins, & Gadalla, 1996) found that teachers working with students of different ages tend to perceive varied levels of self-efficacy as well. In school settings, the leadership of the principal would also change teachers’ self-efficacy. The better a principal can inspire a common sense of purpose among teachers and keep students’ disorder to a minimum level, the higher the teachers perceive self-efficacy. In addition, principals who utilize their leadership to supply resources to teachers and help teachers with disruptive factors but allow teachers’ flexibility over classroom affairs would create such a school atmosphere that permits strong teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs to grow. Finally, teachers’ self-efficacy tends to be higher when the principal of a school can model proper behaviors and provide rewards depending on teachers’ performance (Hipp & Bredeson, 1995; Lee et al., 1991). Teachers’ self-efficacy is influenced by school atmosphere as well. The fact that whether a teacher can participate in the decision-making which concerns his/her 17.

(27) work lives or not would affect his/her sense of efficacy. The greater freedom teachers have in terms of decision-making of their own classroom, the higher their sense of efficacy grows. Teachers who judge that they have greater say in school-based decision making and who sense fewer impediments to teaching would have a stronger sense of efficacy (Moore & Esselman, 1992). In addition, teachers tend to be more satisfied when they perceive other people in their work environment as trustworthy, benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open (Forsyth et al., 2011; Hoy & Tschannen-Moran, 1999). When it comes to the relationship between years of teaching and teachers’ self-efficacy level, the research results are inconsistent. That is, teachers with varied years of teaching perceive different levels of self-efficacy under diverse schools and subject contexts. Novice teachers who received more support at the end of the first year evidenced stronger self-efficacy beliefs (Burley, Hall, Villeme, & Brockmeier, 1991; Hall, Burley, Villeme, & Brockmeir, 1992; to name but a few). However, Chester and Beaudin’s study (1996) in an urban district revealed that experienced teachers’ self-efficacy declined in the first year of teaching under that context. Another factor that caused efficacy discrepancies among novice teachers and experienced teachers is the availabilities of resources. Novice teachers placed heavier emphasis on teaching resources, while experienced teachers’ judgments of their ability to help students’ learning were not significantly related to the availability of resources in the teaching context (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007). Again, the discrepancy among the studies ascertains the importance of varied school settings. As for school location, it would be common to think that urban school settings are more challenging than suburban or rural teaching environments; subsequently, 18.

(28) teachers in urban settings would be expected to have lower self-efficacy. However, in some study (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007), the efficacy beliefs of urban teachers do not differ from those of teachers in other contexts. Teaching level (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007), which means teaching at different educational institutes, bears different weight to teachers’ self-efficacy among novice and experienced teachers as well. The experienced teachers, who perceived higher self-efficacy, are those who taught the youngest children; however, different ages’ students taught at the same school made no difference to novice teachers. In the same study, the support of parents and the community was related to career teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, but these variables did not make a significant contribution to explaining teachers’ sense of efficacy. On comparison, the support of colleagues and of the community contributed more significantly to explaining variance in novice teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs than in experienced teachers’. It seems that experienced teachers have adapted to the typical isolation of their work lives and have learned to base their efficacy judgments on other sources. In the same research (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007), demographic variables such as race and gender were not found to be systematically related to the self-efficacy beliefs of either novice or career teachers. Demographic variables have typically not been strong predictors of the efficacy beliefs of teachers. These variables were included as controls so as to rule out their suspect to influence teachers’ self-efficacy. More research into the important sources of efficacy information would be of great value as we attempt to learn how to better train and equip teachers for their complex tasks. In this light, this study focused on the EFL domain, where not enough research has been made, to explore what factors affected EFL primary 19.

(29) teachers’ self-efficacy. More important, the abovementioned literatures were mainly studies concerning native speakers’ research; the studies under the context of non-native EFL teachers like the current one were still very scarce. That was one of the incentives that propelled the researcher to do this study. EFL Teachers’ Language Proficiency Language proficiency is regarded as one nexus component of EFL teachers’ competence in teaching English. No wonder it forms a factor to teachers’ self-efficacy. Due to the context-bound and subject-specific feature of Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory, there have been increasing studies exploring the relationship between EFL teachers’ language proficiency and their perceived self-efficacy in language teaching. Some researchers have demonstrated the impact of EFL teachers’ perceived language proficiency on their profession self-esteem and confidence (Brinton, 2004; Brady & Gulikers, 2004; Kamhi-Stein & Mahboob, 2005; Lee, 2004; Pasternak & Bailey, 2004); nevertheless, there were not enough studies that explored the relationship between EFL teachers’ language proficiency and their perceived self-efficacy. Here is some related research. In Reves and Medgyes (1994) survey, 84% of the non-native English (NNE) student teachers admitted having difficulties in vocabulary and English fluency; other areas of difficulty included speaking, pronunciation, listening comprehension and writing. Likewise, Samimy and Brutt-Griffler (1999) revealed that 72% of their NNE graduate student subjects were frustrated by their insufficient language proficiency during their teaching. Chacón’s (2005) research explored the effect of teacher’s language proficiency on teachers’ perceived self-efficacy among a group of EFL middle schools teachers in Venezuela. Positive correlations were identified between EFL teachers’ self-perceived English 20.

(30) proficiency consisting of four skills and efficacy for student engagement and efficacy for instructional strategies. In Iran, Eslami & Fatahi (2008) also conducted a study among forty Iranian EFL teachers, 21 females and 19 males, with one to five years of English teaching experience at different high schools to investigate the effect of these participants’ self-reported language proficiency on their perceived self-efficacy. The results showed that teachers with higher perceived spoken proficiency withheld a sense of higher self-efficacy for classroom management. In Taiwan, Chang (2010) also conducted a research among 112 teachers teaching English in colleges or universities to explore the relationships between antecedents and teachers’ self-efficacy and between perceived teachers’ efficacy and their use of motivational strategies in language classrooms. The results showed teachers’ language proficiency in listening, speaking and writing was significantly correlated with their self-efficacy for instructional strategies in EFL classroom (Chang, 2010). Another qualitative study that Chang (2010) conducted in Yun-lin County revealed that 68% of uncertified EFL teachers were unwilling to teach English classes due to their poor English proficiency. Among all the challenges those uncertified EFL teachers faced in Yun-lin County, insufficient English oral proficiency, immature English teaching skills and lack of English pedagogical knowledge frustrated them the most. The findings about the impacts from poor oral English proficiency matched Lee’s study (2009) on Korean primary EFL teachers’ confidence in teaching English. Nunan (2003) in his investigation of the blow of English as a global language on education policies and practices in several Asian countries found that in Taiwan not only the teachers’ training programs were insufficient but in-service teachers’ English skills and pedagogical knowledge, especially concerning teaching younger 21.

(31) learners, were unable to meet the goals of English curriculum set by the Ministry of Education. The following year, Butler (2004) focused his study on EFL teachers’ language proficiency in the same region, i.e., South Korea, Taiwan and Japan. The findings pointed out that the teachers’ self-evaluated language abilities did not consist with the proficiency they regarded would empower them to have better teaching effectiveness in primary school settings. After the implementation of English education in primary school in 2001, all counties have suffered from the shortage of qualified EFL teachers. In a large scale nationwide survey led by Chang (2009) revealed that using the criteria of language proficiency and professional pedagogic knowledge to gauge public primary and junior schools’ EFL teachers, only 51.7% of them were above the certified standard. Ho and Wu (2007) revealed that almost 70% of parents in Taiwan had little confidence in public English education. From EFL teachers’ language proficiency to English education outcomes, there is a missing link here. Further inquiry into this line is required. Based on the literature reviewed above, there is an urgent need to build up the data by examining NNETs’ perceptions of their self-efficacy in terms of personal capabilities to teach English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and how their perceived English language proficiency level impacts on their EFL pedagogic strategies. Thus, this study is to explore self-efficacy beliefs among primary school EFL teachers in Taoyuan County, considering that both language proficiency and the teachers’ assessment of their capabilities form part of their efficacy beliefs (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998). Teachers’ Practices versus Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs differentiate teachers in many ways from their 22.

(32) behaviors, practices in the classroom, to their mental states. In general, efficacious teachers were more able to take on challenges, to cope effectively with stress factors, such as conflicts with colleagues and students or setbacks in teaching, and to quickly get over the sense of failures. By contrast, less efficacious teachers tended to shy away from difficulties, quickly lost their confidence in face of hindrances, and more likely became preoccupied with their own personal deficiency (Bandura, 1995; 1980). Several research has also shown the close relationship between teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and classroom management in various ways. Gibson and Dembo (1984) stated that the more efficacious teachers are, the more likely group discussion as instructional strategy is used in class instead of whole-class lecturing. In addition, efficacious teachers tended to commit to teaching more (Coladaric, 1992). Furthermore, these teachers would spend more time working with the students in difficulties and guiding them to find the correct answers instead of showing the answer directly or calling on another student. Some study (Woolfolk & Hoy, 1990) also pointed out that practicing teachers’ perception of instructional ability was correlated to how they controlled students. The more efficacious teachers are, the less custodial they were when managing students, which confirms the findings of Woolfolk and Hoy’s (1990) study that prospective teachers with higher self-efficacy tended to be more humanistic in terms of dealing with students, emphasizing on cooperation, interaction and student autonomy more. Emmer and Hickman (1991) also revealed that teachers with higher self-efficacy preferred to use positive management strategies such as reasoning with students rather than using reductive strategies like warnings. Saklofske et al.’s (1988) study indicated that student teachers with higher personal teaching efficacy (PTE) 23.

(33) reflected more positive behaviors in terms of lesson presentation, classroom management and questioning behaviors. Finally, Soodak and Podell (1993) found that teachers with higher self-efficacy on PTE would yield the idea of placing students with learning or behavioral problems in a regular classroom more than of placing them in the classroom of special education by comparison with the less efficacious teachers. Teachers’ self-efficacy has impacts on teaching quality as well. Some researchers (Adedoyin, 2010; Bayraktar, 2011; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) pointed out that teachers’ self-efficacy highly affects teachers’ motivation and preparation to teach, making teachers vary in their choice of teaching materials, degree of enthusiastic attitudes and adoption of innovative instruction. Some studies (Adedoyin, 2010; Chan, Tan & Khoo, 2007; Ho & Hau, 2004) also corroborated that self-efficacy has significant impacts on teacher’s behaviors and performances in the process of delivering instructions, such as considering students’ needs, applying various student-centered and innovative teaching methods, making more efforts to teach difficult and unmotivated students and considering students’ mistakes as a normal part of learning process. The research results also confirmed that teacher’s self-efficacy has a positive and consistent relationship with teaching behaviors and the learners’ outcomes (Tschannen-Moran,Woolfolk-Hoy, & Hoy, 1998) and it is also related to teachers’ commitment to teaching and classroom management skills (Coladarci, 1992). In addition, teachers’ self-efficacy would also influence the way how teachers interact with their students and colleagues, especially in the case of encountering conflicts (Adedoyin, 2010). Efficacious teachers employ less teacher-directed but more student-centered instruction (Ashton and Webb, 1986) and adopt a more 24.

(34) humanistic- and less dominated-orientation to teaching (Woolfolk and Hoy, 1990). Emmer and Hickman (1991) found that prospective teachers’ efficacy scores were positively correlated with their tendencies for positive management strategies. For example, they would listen more tentatively to and talk more considerately with a student. In addition, when necessary, they would revise the assignments to suit students’ level. In the same light, Gibson and Dembo’s discovery (1984) found that teachers with higher sense of efficacy were less likely to criticize the students after incorrect responses and more likely to persist with the struggling students. Before and during the process of delivering instructions, teacher’s self-efficacy would enhance teacher’s tendency and ability to assess their own instructional performance. When students failed, teacher’s self-efficacy would only strengthen their commitment to teaching profession (Coladarci, 1992). Students’ Achievements versus Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs Any influence is seldom unilateral. Teachers may hold greater power in the domain of SLA due to their knowledge and capabilities. Nevertheless, students’ attitude holds up an important factor to teachers’ self-efficacy as well. To take one step further, it has been found that teachers’ high self-efficacy would improve students’ motivation, self-efficacy, learning and achievement (Adedoyin, 2010; Chang, 2010; Hollon, Anderson & Roth, 1991; Johnson, 1992; Wilson & Wineburg, 1988; to name but a few). The rationale behind the finding is that teachers with higher self-efficacy are more likely to be successful in providing an effective learning environment and developing students’ knowledge and skills. More interestingly, this kind of impact is not one-way route. According to Bayraktar’s (2011) study, teachers’ and students’ efficacy are mutually related. The previous finding has also corroborated that teacher’s self-efficacy affects and is 25.

(35) affected by students’ efficacy (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998). That is, “ low teacher efficacy leads to low student efficacy and low academic achievement, which in turn leads to further decline in teacher efficacy” (Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy & Hoy, 1998, p. 222). Phenomena of English Education in Taiwan Incorrect policy and wrong implemented timing will cause a lot of problems. The following discussion is about some phenomena of English education in Taiwan. English Education Policy and Principles English education was first mandated into primary school curriculum in 2001 for grade 5 and 6. However, at that time some rich counties such as Taipei had outrun far earlier and begun it younger to grade 1 already. Later on, English education was extended to grade 3 officially in 2006. Taoyuan made it a step forward by designing a period every week integrating English and culture learning, called “Knowing the world” in name, into the curriculum of grade 1 and 2 in 2009, which became a mandated subject in 2011. The principles of the curriculum were set out by the Ministry of Education (MOE, 2000) as follows. The objective of the elementary/junior high school curriculum should be to instill a basic communicative ability to prepare students to take a global perspective, and to give individuals confidence in communicating in the global area. Elementary and middle schools should provide a natural and enjoyable language learning environment. (p. 2). In 2009, MOE stressed again the design of English teaching activities should follow the principles of helping students acquire basic communicative skills, learn different cultures, and develop students’ learning interest and strategies. It is not difficult to see communication, culture and interest are the key components of 26.

(36) English education. Responding to the policy, Taoyuan Government took the following movements: the resources were invested to build up bilingual environments in primary schools; three English villages (first in the country) were set up for students to immerse in pure English contexts; teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) programs were designed by universities for in-service teachers to improve their teaching efficacy; finally, teaching materials and resources were integrated online for teachers to use. Channels of Recruitment of Primary EFL Teachers To meet the demand for more EFL teachers in primary English education, MOE took the following three ways: 1. Held language proficiency tests to recruit qualified persons with at least B.A. degree. Once these persons finished teacher trainings, they were deployed to teach. 2. The local governments were authorized to recruit the in-service teachers with willingness and gave them TEFL trainings. 3. Encourage teacher training institutes to set up English related departments to train EFL primary teachers for the future in the long run. However, the reality was that not many people in the first group were able to finish the teacher training courses so as to teach English in primary schools. So, a lot of them dropped out in the middle of the programs. And, the teachers recruited in the second group were mostly those with poor language abilities. As for the third group, it took too long to meet the urgent demand and the amount is not sufficient either. It is not strange that many schools still suffer from the problems of not having enough qualified EFL teachers, especially in remote rural areas (Chang, 2009). 27.

(37) Difficulties in the Language Classroom of Primary Schools The approach of communicative language teaching (CLT) is encouraged by MOE and it is also integrated in the contents of many textbooks or teaching materials. EFL teachers were supposed to have such professional pedagogical knowledge and language abilities to carry out the practices. However, what really happened in the language classrooms of Taoyuan was not clear yet so this research aims to shed light on the area to fill up the research gap. Some of the survey results may be able to provide a picture of how the Taiwanese language classroom looked like. The first three of the most frequently mentioned predicaments (Chang et al., 2009) in primary language classroom were 1)instruction time is too short, 2)levels of students in a class are too different, and 3)teaching effectiveness is questioned. The gap of language abilities among different levels’ students is getting wider and wider due to many reasons, but it has caused classroom management problem, instructional strategy failure, and teaching resources waste. In addition, some studies (Nunan, 2003; Yang, 2012; Yu, 2008) even pointed out that due to the cultural differences, the CLT approach might not be the best or most effective way in Taiwanese language classroom. Based on the foregoing descriptions about the features of current English education phenomena, there exists quite a few controversial issues in Taiwanese EFL settings and EFL teachers encounter a lot of difficulties and come under enormous pressure. Wertheim and Leyser’s study (2002) revealed that the teachers with higher sense of PTE would more likely use a variety of instructional strategies to meet different students’ learning needs. Other research also confirmed the findings in which the higher self-efficacy a teacher perceived, the more efforts would be put into individualized instruction and in modifying teaching practices 28.

(38) (Saklofske et al, 1988; Minke et al., 1996). However, little domestic study has been done to reveal the information on the levels of Taiwanese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy with their language proficiency and EFL pedagogic strategies taken into account, let alone their relationships. A Missing Link to Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Research has long concluded that language proficiency made up the foundation of the professional confidence of non-native English teachers, which influence their self-esteem and professional status (Berry, 1990; Chang, 2010; Doff, 1987; Lee, 2009). Poor language proficiency results in low self-confidence, and such state of mind might hamper simple teaching procedure and prevent teachers from fulfilling some pedagogical requirements such as more communicative approach to teaching English. However, as stated earlier, most of the literature was done under the contexts of native speakers; few explored how language proficiency affects EFL teachers’ self-efficacy and pedagogic strategies. Clearly, there exists a missing link to the relationships among non-native EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, language proficiency and their EFL pedagogic strategies. Little literature can be found in Taiwan stating what the relationships of these three domains are in primary EFL settings. Hence, the current study is motivated to find it out. Based on the abovementioned literature review, it can be concluded that contextual and background factors, first, form the antecedents to the formation of teachers’ self-efficacy; then, subject-related competence, namely language proficiency in this study, poses strength to influence teachers’ efficacy perception levels. Different levels of teachers’ self-efficacy will have impacts on teachers’ pedagogic strategies, their adaptabilities to change and flexibilities in language 29.

(39) classroom. Therefore, the hypotheses were made and a hypothesized causal model is established in Figure 2-4.. Research Hypotheses 1. Contextual and personal factors would form the factors to the formations of self-efficacy. 2. Teachers’ self-efficacy would hold an important key to their pedagogic choice.. 30.

(40) Based on the purposes of the study and the hypotheses above, the following research questions are drawn. Research Questions: (1) What are the levels of primary EFL teachers’ perceived self-efficacy, language proficiency and their pedagogic strategies in Taoyuan County? (2) What are the effects of the antecedents on teachers’ self-efficacy and their pedagogic strategies? (3) What are the relationships among teachers’ self-efficacy, language proficiency and pedagogic strategies?. 31.

(41) 32.

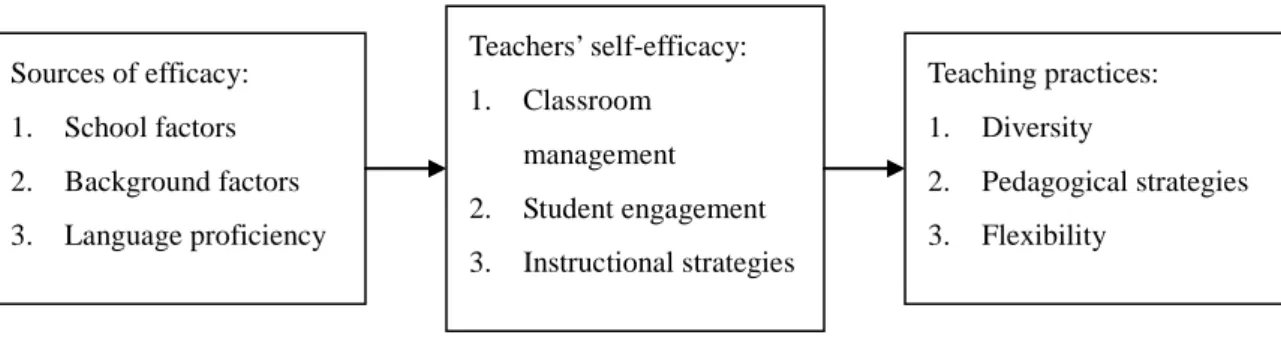

(42) CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY The current study aims to explore EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, language proficiency, pedagogic strategies and the factors that influenced their self-efficacy and pedagogical proclivity. Therefore, this chapter intended to present the rationales for the research design and procedures for data collection and subsequent statistical analyses. It was divided into the following sections: research structure, participants, instruments, data analysis, and research procedure. Research Structure Based on the notions of teachers’ self-efficacy by Bandura (1986, 1997) and the cyclical nature of teacher efficacy by Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy (2001, 2007), the current research set up the research structure as Figure 3-1. Teachers’ self-efficacy serves as a mediator whose formation factors are from contextual factors and personal background variables. Teaching practices are the results of teachers’ self-efficacy. Therefore, the components of research variables are evolved around it. Teachers’ self-efficacy: Sources of efficacy:. Teaching practices: 1.. 1.. Classroom. School factors. 1.. Diversity. 2.. Pedagogical strategies. 3.. Flexibility. management 2. 3.. Background factors Language proficiency. 2.. Student engagement. 3.. Instructional strategies. Figure 3-1 Research Structure. 33.

(43) Participants All nonnative EFL public primary school teachers in Taoyuan County were included in the research as participants. Private elementary schools were excluded because they varied in many ways from public schools, such as school settings, faculty, curriculum design, students’ backgrounds and so on. Taoyuan County was chosen due to its special features in many ways. Positioning itself as the gate of Taiwan, Taoyuan is to be transformed into Taoyuan Aerotropolis. In order to carry out the plan, tremendous funds and resources were put in to advance English education and to enrich English language environments. The local government’s policy is to make Taoyuan so internationalized as to make it the culture ambassador for Taiwan. The English education was officially extended to first grade from 2011, forerunning many other cities and counties in Taiwan. To meet the demand for more English teachers, the government not only recruited overseas volunteers and hired qualified substitute teachers but also held 20-credit TEFL training programs every summer for in-service teachers. Yet, little research was made to explore whether there would be any discrepancies between teachers’ need and the availabilities of resources, which drove the researcher to do this study focusing on this county. According to the Ministry of Education (MOE, 2012), for the academic year 2012, there were a total of 188 public primary schools with 542 English teachers in Taoyuan County. Stratified random sampling method was employed. Out of total 460 samples, 384 teachers responded. Among them, 339 teachers were female, reaching 88.3%. More than fifty percent of the participated teachers took on multiple job postings, which made the pure subject teachers less than half. All of the participants were B.A. holders or above but up to 62 percent of them did not 34.

(44) major in English. When the data was collected, there were still more than one fifth of the participated teachers attending TEFL-related trainings with less than 10 credits and 16.4 percent of participated teachers were appointed to teach English against their will. With 12 years’ official English education implemented in Taiwan, only 16.4 percent of the participated teachers had more than ten years’ EFL teaching experience. Table 3-1 displays the summary of descriptive statistics of participants’ background information of this study. Table3-1. Summary of Descriptive Statistics of Background Information of Participants in the Formal Study Indicators. Frequency. Percent. Gender. Male Female. 45 339. 11.7 88.3. Job Position. Subject teacher 189 Homeroom teacher 55 Administrative staff 140. 49.2 14.3 36.5. Highest Educational Attainment. B.A. M.A. Ph.D.. 223 160 1. 58.1 41.7 0.2. University Major. English Other than English. 148 236. 35.8 61.5. TEFL Training. Above 10 credits Below 10 credits. 300 84. 78.1 21.9. Willingness to Teach English. Volunteer Against the will. 321 63. 83.6 16.4. Year(s) of Teaching Experience. 0~3 years 3~10 years Above 10 years. 160 161 63. 41.7 41.9 16.4. Instrument To answer the research questions, the current study adapted the long version of the Ohio State teacher efficacy scale (OSTES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) that is constructed under the cyclical formation of teacher efficacy beliefs and has 35.

數據

Outline

相關文件

Compared with the class in late August, both teachers have more confidence in using English to teach the music class. Again, “music in the painting” part still caught

4.以年資辦理國民小學教師加註英語專長證書者,以本參照表為採認依據,不在本參照表之

候用校長、候用主任、教師 甄選業務、考卷業務及試 務、教師介聘、外籍英語教 師及協同教學人員招募、推

● develop teachers’ ability to identify opportunities for students to connect their learning in English lessons (e.g. reading strategies and knowledge of topics) to their experiences

• enhance teachers’ capacity to integrate language arts rich in cultural elements into the school- based English language curriculum to broaden students’ understanding of the

Looking at both sets of findings together, the research team concluded that the ENET Scheme overall has a positive impact on English language teachers’ pedagogical practices

Roles of English language (ELTs) and non- language teachers (NLTs)3. General, academic and technical

Work in a collaborative manner with subject teachers to provide learners with additional opportunities to learn and use English in the school. Enhance teachers’ own