Asian Journal of Social Psychology (2005) 8: 5–17

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKAJSPAsian Journal of Social Psychology1367-22232005 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association April 200581517Original articlePhilosophical reflection on IPKwang-Kuo Hwang

Correspondence: Kwang-Kuo Hwang, Room 215, South building, Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, No.1, Section 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan. Email: kkhwang@ntu.edu.tw

A philosophical reflection on the

epistemology and methodology of

indigenous psychologies

Kwang-Kuo Hwang

Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taiwan

In order to answer the three crucial questions (why, what and how) about the development of indigenous psychology, three levels of breakthrough need to be made, namely, philosophical reflection, theoretical construction and empirical research. The controversial issues that have occurred in the earlier development of indigenous psychology are analyzed in terms of the switch in Western philosophy of science from positivism to post-positivism. Based on this analysis, it is argued that indigenous psychologists should construct formal theories illustrating the functioning of the human mind that may be applicable to various cultures, and then use these theories to study the particular mentalities of people in a given culture with the scientific methods of empirical research.

Key words: formal theories, indigenous psychology, philosophy of science, positivism, post-positivism.

Introduction

At the end of the 1970s, a number of psychologists began to advocate an indigenous approach to psychology in non-Western countries such as Mexico (Diaz-Guerrero, 1975), Korea (Kwon, 1979), Japan (Azuma, 1984), the Philippines (Enriquez, 1977; Legmay, 1984), India (Sinha, 1986) and Taiwan (Yang, 1997). Since 1990, this trend has become increasingly popular and attracted progressively more attention from mainstream psychologists (Shiraev & Levy, 2001), who have also criticized claims of indigenization. A careful examination of the debates between these two camps reveals that three crucial questions should be answered in order to settle the most controversial issues.

1 Why did the indigenization movements of psychology emerge in non-Western countries? 2 What are the epistemological goals of indigenous psychology?

3 How may these goals be achieved?

These three questions are all related to the knowledge that indigenous psychologists are attempting to construct. In order to ensure indigenous psychology is compatible with mainstream scientific psychology, these three questions should be answered from the perspective of the Western philosophy of science, because knowledge of scientific psychology is a product of Western civilization.

6 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

The first section of the present paper answers the first question with an analysis of the social psychological background incubating the indigenization movement as well as the controversial issues caused by its emergence. Then, the debates between indigenous and mainstream psychologists are explained in terms of the switch of philosophical assumptions underlying the three types of approaches to cultural psychology. In section III, I answer the second question with a discussion of the essential nature of the epistemological goal of indigenous psychology and, then in section IV, the dramatic changes in both the epistemology and methodology of scientific research when mainstream philosophy of science moved from positivism to post-positivism are examined to illustrate the material discussed in section III. Finally, the methodologies for constructing a universal psychology as suggested by several indigenous psychologists are critically reviewed in section V of this article to answer question three. A brief example of how the goals of indigenous psychology may be achieved is provided in the concluding remarks.

I. The emergence of indigenous psychology and related debates The emergence of an indigenization movement in non-Western countries has been inspired by a spirit of nationalism and anticolonialism. Psychologists of non-Western countries mostly follow Western theories and adopt research methods developed by Western psychologists when conducting research in their native societies. The problem of implantation is most serious in social psychology. Most knowledge in this field has been developed by American psychologists who usually take issues of their home society as research topics, develop instruments of measurement by using materials that are meaningful in their own cultural context, and construct theoretical frameworks for the sake of solving their own problems (Moscovici, 1972; Berry et al., 1992).

The imposition of a Western research paradigm on non-Western countries can be viewed as a kind of cultural imperialism or colonialism (Ho, 1998). Findings derived from such an approach are mostly irrelevant to or inadequate for understanding the mentality of people in non-Western countries (Enriquez, 1981; Mehryar, 1984; Sinha, 1986). Hence, most Western theories of social psychology are culturally bound. Replication of the Western paradigm in non-Western countries may cause neglect of important cultural factors that have profound influence on the development and manifestation of human behavior in that particular culture. Therefore, many indigenous psychologists advocate the scientific study of human behavior and mental process within a culturally meaningful context (Adair et al., 1993; Kim & Berry, 1993; Ho, 1998; Kim et al., 2000) using a bottom-up model-building paradigm (Kim, 2000) in order to develop a culturally appropriate psychology (Azuma, 1984), a psychology based on indigenous realities (Enriquez, 1993), or a psychology that relies on native values, concepts, belief systems, problem methods and other resources (Adair et al., 1993; Ho, 1998). The epistemological goals as well as the methodological approach of indigenous psychology have been criticized by mainstream psychologists. For example, Triandis (2000) pointed out that a similar approach has been used by anthropologists for years, and that accumulating idiosyncratic data with an anthropological approach may not provide much contribution to the development of scientific psychology.

Poortinga (1999) indicated that the usage of plural indigenous psychologies implies a restriction for development of indigenous psychology. The development of multiple psychologies not only contradicts the scientific requirement of parsimony, but also makes the demarcation of cultural populations a pending problem. If every culture has to develop its

Philosophical reflection on IP 7

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology own psychology, how many psychologies would have to be developed? What is the meaning of an indigenous psychology to people in other cultures?

Ho (1988) supported indigenous psychology. He advocated the development of an Asian psychology and warned that blindly transporting paradigms of Western psychology into non-Western countries might cause researchers to fall into the trap of non-Western ethnocentrism. However, he also warned that another kind of ethnocentrism in reverse would arise if every culture develops its own psychology. Over-emphasis on the nature and extent of differences in psychological functioning between people of different cultures may make indigenous psychology a kind of ‘scientific ethnocentrism in a new guise’ (Poortinga, 1996, p. 59).

Hermans and Kempen (1998) proposed the concept of ‘moving culture’ and discussed the perilous problems of cultural dichotomy in a globalizing society. When intercultural communications become so frequent that the whole world is becoming a global village, it is very hard to regard culture as something internally homogeneous and externally distinctive. If individuals are able to choose and decide their own behavior, psychological traits and mechanisms would be incidental, culture may have no necessary influence on the individual, and the notion of regarding culture as a psychological system becomes less feasible.

In response to these challenges, many indigenous psychologists have argued that the final goal of indigenous psychology is to develop an Asian psychology (Ho, 1998), a global psychology (Enriquez, 1993; Yang, 1993; 2000), a human psychology (Yang, 1993) or a universal psychology (Berry & Kim, 1993). In order to achieve this goal, they have proposed several research methods or approaches, including the derived etic approach (Berry, 1989; Berry & Kim, 1993), the metatheory method (Ho, 1998), the cross-indigenous method (Enriquez, 1977; 1993), as well as cross-cultural indigenous psychology (Yang, 1997; 1999). II. Philosophical switch for the development of

indigenous psychology

A careful examination into the controversial issues between indigenous psychologists and mainstream psychologists reveals that their debates are concentrated not only on the epistemological goals for the development of indigenous psychology, but also on the methodology to achieve these goals. In other words, a plausible solution to resolving debates on this issue should take into consideration both epistemological and methodological controversies at the same time.

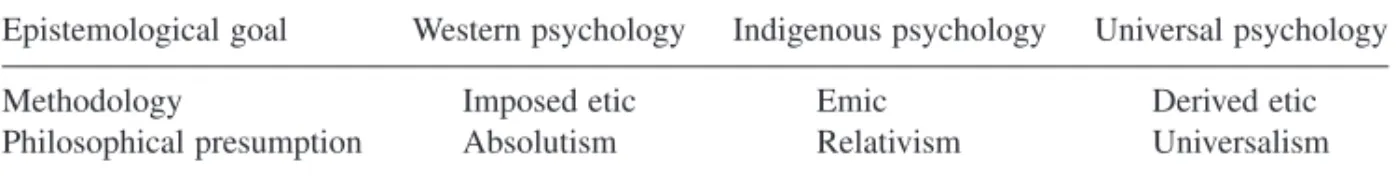

The transition from indigenous psychologies to an Asian psychology, global psychology, universal psychology or a human psychology implies a significant shift in philosophical presumptions, which can be illustrated by an important argument proposed by Berry et al.

(1992). They pointed out that there are three philosophical presumptions in cross-cultural psychology, namely, absolutism, universalism and relativism, which correspond to three research orientations: imposed etic, derived etic, and emic (Table 1). Western (American) psychology researchers ignore cultural differences and insist on the imposed etic approach

Table 1 Epistemology, methodology and philosophical presumption of three approaches in cultural psychology

Epistemological goal Western psychology Indigenous psychology Universal psychology

Methodology Imposed etic Emic Derived etic

8 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

as well as its philosophical presumption of absolutism by imposing Western theories and research instruments on people of non-Western societies. In contrast, indigenous psychology researchers follow the strategy of the emic approach, with its philosophical presumption of relativism, using indigenous instruments and methods of research with the expectation of developing substantial theories or models that are culturally specific to local people. However, the goal underpinning the search for a global psychology, universal psychology or human psychology can only be obtained by changing the philosophical presumption from relativism to universalism. If indigenous psychologists maintain the philosophical presumption of relativism, and insist on a bottom-up approach for constructing substantial theories through the inductive methods of positivism, it will be very difficult for them to achieve the goal of developing a global psychology.

III. The epistemological goal of universal psychology

This argument can be illustrated by first analyzing the epistemological goal of indigenous psychology, namely, the goal of developing a global psychology, universal psychology or human psychology. In his critique on the epistemological goal of indigenous psychologies, Poortinga (1999, p. 419) strongly suggested that ‘differences in behavioral repertoires across cultural populations should be understood against the background of a broader frame of commonness’. He argued that over-emphasis on cross-cultural differences in behaviors and negation of important invariance in psychological functioning across different cultures is not only ‘factually incorrect’, but also ‘theoretically misleading’ (Poortinga, 1999, p. 425).

His viewpoint is very similar to that of cultural psychologists who proposed a distinction to explain their fundamental view of human nature: one mind, many mentalities (Shweder, 1996; 2000; Shweder et al., 1998). It indicates that the psychological functionings or mechanisms of the human mind are the same all over the world, but that people may evolve various mentalities in different social and cultural environments. For the sake of developing a universal or global psychology, indigenous psychologists should incorporate both cultural variation and cross-cultural invariance into their research schemes. This goal cannot be achieved by the inductive approach as suggested by those indigenous psychologists who insist on the philosophy of positivism. The reason is revealed by a closer examination of the meaning of the terms ‘mind’ and ‘mentality’.

According to Shweder’s definition, ‘mind’ means ‘the totality of actual and potential conceptual contents of human cognitive process’ and ‘mentality’ denotes ‘the cognized and activated subset of mind’ (Shweder, 2000, p. 210). A mentality is owned or exercised by some group of particular individuals, so it can be a subject for research in cultural psychology. In contrast, mind refers to all the conceptual content that any human being might ever cognize and activate. This universal mind cannot become the subject of research in cultural psychology. If indigenous psychologists want to achieve the goal of universalization with the inductive approach, they would have to carry out a very large-scale research program by traveling around the globe to investigate all indigenous psychologies. Moreover, they would also have to take into account what has been manifested in the past history and even the future of each culture (Wallner & Jandl, 2001).

Obviously this is an impossible mission. So, how can indigenous psychologists achieve the goal of a global psychology? From the perspective of philosophy of science, they should abandon the inductive approach advocated by positivists, adopt the philosophical assumptions of post-positivism, construct formal theories about the psychological functionings of the

Philosophical reflection on IP 9

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology human mind on the basis of previous findings using critical rationality (Popper, 1963) or creative imagination (Hempel, 1966), and then use these theories to analyze the particular mentality of a people in an indigenous culture. In other words, they should assume that the functionings of the human mind are invariant across different cultural populations, but that the contents and manifestations of these functionings may vary to a great extent in responding to the diversity of the cultural context (Berry et al., 1992; Poortinga, 1997). In order to achieve the goal of a universal psychology, indigenous researchers should construct formal theories illustrating the functionings of the human mind that are applicable to various cultures and use them to study the particular mentalities of the people in a given culture by examining their psychology and behaviors in daily life.

I have discussed my answer to the second question concerning the epistemological goal of indigenous psychology. The remaining sections of this article review the dramatic change in epistemology and methodology that have occurred in the philosophy of science with the switch from positivism to post-positivism. Based on the philosophy of post-positivism, I discuss my answer to the third question by providing a critical review of the various methodologies as suggested by indigenous psychologists for achieving the goal of universal psychology. In the conclusion section of this article, I use my analysis of Confucian cultural tradition as a brief example to illustrate how indigenous psychologists can construct a series of theoretical models both to explain the psychological mechanisms of the universal human mind, and to interpret the particular mentality of Confucian culture.

IV. The dramatic change in the philosophy of science

When the mainstream philosophy of science moved from positivism to post-positivism, dramatic changes had occurred in both the epistemology and methodology of scientific research. Epistemologically, it has become clear that scientific theory is not inducted from the accumulation of empirical facts, but constructed through the critical thinking of scientists. Methodologically, it has been noted that verification of scientific propositions as suggested by positivists is impractical, while the idea of falsification as proposed by Karl Popper is also difficult. If the indigenous approach is defined as a branch of science, indigenous researchers must recognize the implications of this philosophical switch in drawing up a scheme for the future development of indigenous psychology. In order to illustrate my arguments, in this section I review the dramatic changes in epistemology and methodology that occurred with the shift in the philosophy of science from positivism to post-positivism with a brief presentation of Popper’s evolutionary epistemology and Hempel’s logical empiricalism.

IV. 1. Positivism

The method of induction had been regarded as the main approach for acquiring knowledge through positivism. For instance, Wittgenstein (1889–1951), whose earlier works had profound influence on the Vienna Circle in the 1920s, maintained in his famous writing

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that the main goal of scientific activity is to use language to describe the world. Atomic facts should be described with elementary propositions that can be verified with empirical methods. Through the logical deduction of truth functions, elementary propositions can be combined into a scientific proposition. A proposition is a picture of reality, and the totality of true propositions reflects the nature science as a whole (Wittgenstein, 1922).

10 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

Wittgenstein’s earlier philosophy takes the position of copy theory or photo theory, insisting that a scientific proposition has to copy or to record atomic facts and their structure clearly and correctly. The logical form of an elementary proposition has to correspond with the logical structure of the atomic facts. The knowledge thus obtained is an objective representation of the external world in the mind or brain. According to this viewpoint, elementary propositions describe atomic facts repeatedly experienced by human beings, and scientific rules are established on the basis of these repeated empirical facts. Elementary propositions, which are the fundamental components of a scientific proposition, are induced from past experience.

Schlick (1882–1936), the organizer of the Vienna Circle, contributed much to promote the ideas of logical positivism. He argued that when a person elaborates the meaning of a sentence, that person is trying to explain the conditions for the sentence to be a true proposition, which is the way to verify the sentence. As Schlick observed, the meaning of a proposition is the way to verify it (Schlick, 1936).

IV. 2. Popper’s evolutionary epistemology

With active promotion by the Vienna Circle, logical positivism had an extraordinary influence on the thought of the scientific community from 1930 to 1950. When it reached the peak of academic prestige, it began receiving criticism from its academic opponents. The first challenge came from Karl Popper’s (1902–1994) evolutionary epistemology. Popper (1963) argued that scientific theories are not induced from empirical facts, but deduced by scientists with critical rationality. The procedure of scientific research should begin with a problem. When a scientist finds new empirical facts that cannot be explained, or inconsistencies in pre-existing theories, a tentative solution or theory may be proposed to solve the problem. Potential errors are eliminated by examining the theory against empirical facts in the world. The deductive method Popper advocated is not the traditional deduction grounded in axiomatic premises. Popper argued that the premises of deduction for a tentative theory of scientific conjecture should be repeatedly subjected to empirical examination. This method is called deduction with examination. Popper suggested, ‘Our intellect does not draw its laws from nature, but tries - with varying degrees of success - to impose upon nature laws which it freely invents’ (Popper, 1963, p. 191). He was strongly opposed to the idea that scientific theory can be achieved by an accumulation of true propositions for describing empirical facts. According to one of Popper’s analogies, the water bucket of scientific theory will not be spontaneously full so long as scientists work hard to fill it with accumulated empirical facts. Instead, theory is like a searchlight. Scientists must continuously bring up problems and make conjectures, so as to cast the light of theory on the future (Popper, 1972, pp. 431–457). If a theory records only previous findings, and nothing can be deducted from it except pre-existing facts, what is the use of the theory?

Popper also opposed the principle of verification as advocated by positivists. According to Popper, a theoretical proposition cannot be verified, it can only be falsified by empirical facts contradictory to the theory. Scientific theory is stated with general predications. However, empirical facts are individually experienced. No matter how many times a particular experience is repeated, it cannot verify a proposition of general prediction. For instance, no matter how many white swans have been observed, the proposition of general predication ‘swans are white’ still cannot be verified, because our observations cannot include all swans. Therefore, scientists cannot verify theoretical propositions, only falsify them, or reserve them temporarily before they are falsified.

Philosophical reflection on IP 11

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

IV. 3. Hempel’s logical empiricalism

When logical positivism was criticized, Hempel, who had participated in the academic discussions of the Vienna Circle in earlier years, tried to modify its shortcomings and proposed the new idea of logical empiricalism. In his Aspects of Scientific Explanation

(Hempel, 1965), he proposed a deductive model or model of covering law, which stated that scientific explanation usually contains two kinds of statements, namely, general laws and antecedent conditions. Using these two kinds of explanans as the premise, a scientist can deduct a description of a phenomenon, which is called the explanandum.

This deductive model also highlights the difficulty of verifying a proposition. In the deductive model, the general laws for scientific explanation are stated in the form of general predications. Because nobody can make unlimited observations, all propositions of general predication will eventually become meaningless.

Hempel also pointed out the difficulty of falsifying a hypothetical proposition. When scientists test a hypothesis, they must propose several auxiliary hypotheses that prescribe the antecedent conditions for its occurrence. Some of these auxiliary hypotheses are related to the scientific theory itself, and some to experimental design, instrumental equipment, or research procedures. A combination of all these conditions may lead to the occurrence of the phenomenon observed.

Obtaining a negative result from research rarely encourages a scientist to give up general laws. Instead, a researcher will usually examine the research instruments, reconsider the experimental design, or even repeat the experiment. These steps imply only consideration of whether there is anything wrong with the auxiliary hypotheses, indicating that it is not easy to falsify a hypothesis.

For this reason, Hempel (1965) argued that the target to be examined in scientific research is not a sole hypothesis, but the whole system of theory. Moreover, as a logical empiricalist, Hempel (1966) also believed that it is impossible for a scientist to induce theory from empirical facts. For example, Newton’s law of gravity and Einstein’s theory of relativity were created through imagination to explain what was observed, not inducted from a collection of observed phenomena.

The transition from data to theory requires creative imagination. Scientific hypothesis and theories are not derived from observed facts, but invented in order to account for them. They constitute guesses at the connections that might obtain the phenomena under study, at uniformities and patterns that might underlie the occurrence. (Hempel, 1966, p. 15)

V. A critical review of methodologies for constructing a universal psychology

The brief review above highlights the dramatic changes in epistemology and methodology with the switch from positivism to post-positivism in mainstream philosophy of science. This change has a significant implication for dealing with the challenges encountered by indigenous psychologists in developing a global psychology. Strictly speaking, indigenous psychologists cannot attain the goal of building theoretical models for a global psychology through an inductive approach. What they can do is use their creative imagination or critical rationality to construct a formal theory on the psychological functioning of the universal mind that applies to various cultures, and then use it as a framework for analyzing the specific mentalities of a given culture. If indigenous psychologists insist on the inductive approach

12 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

of positivism, which emphasizes construction of a substantial theory that can first be applied to a particular culture, and then integration of these psychologies to attain the goal of a global psychology, they will encounter several epistemological or methodological difficulties. In this section, I review and discuss the feasibility of methods for constructing a global psychology proposed by several major indigenous psychologists, including the derived etic approach, the cross-indigenous method, the metatheory approach and cross-cultural indigenous psychology.

V.1. The derived etic approach

Berry (1969; 1989) classified the research approaches of cross-cultural psychology into three categories, namely, imposed etic, emic and derived etic. The imposed etic approach assumes that the theories used by a researcher can be applied to all cultures. However, if they are originated from outside the culture in which they are applied, they are very likely to be insufficient. Most indigenous psychologists therefore advocate the emic approach, which emphasizes use of concepts and terms from the local cultural system to understand the meanings of local phenomena. The derived etic approach attempts to integrate the knowledge obtained by the imposed etic and emic approaches through a process of comparison. Berry and Kim (1993) regarded the derived etic approach as a necessary step in constructing a more universal psychology.

A crucial question to ask at this point concerns the nature of the imposed theory to be used by indigenous psychologists in a derived etic approach. If it is a formal theory for interpreting psychological functioning of the human mind that is applicable to various cultures (though assumptions might be falsified by empirical facts), the derived etic approach proposed by Berry (1969; 1989) is acceptable. On the other hand, if it is a substantial theory referring to an acculturation strategy of integration ‘where psychology draws upon the ideas, theories, methods, and findings of both [cultures], [and] eventually all societies yield to the generalized universal psychology’ (Berry, 1993, p. 272), such an advocacy implies repeated use of inductive method, and its feasibility is dubious. Following this approach, no matter how many cultures are studied, the studies contribute only ‘one small step toward a universal psychology’ (Berry, 1993, p. 260). The final goal of attaining a global psychology would always be far away.

V.2. The cross-indigenous method

Enriquez (1977; 1993) separated indigenous research strategy into indigenization from within and indigenization from without. The approach of indigenization from without is very similar to the imposed etic approach. It advocates importing (Western) knowledge of psychology from dominant source cultures to interpret data obtained from the target culture in the third world. Enriquez strongly opposed this approach. Instead, he advocated the approach of indigenization from within by using ‘the local languages and cultures as sources for theory, method, and praxis’ (Enriquez, 1993, p. 163). In order to increase the generalizability of research findings in indigenous psychology, he proposed a cross-indigenous method that entailed using various cultures as the source for cross-indigenous psychology, expecting to broaden the database for building a global psychology.

The focus of Enriquez’s (1993; 1977) discourse is language and culture. His cross-indigenization method is subject to the difficulty of the inductive approach. Although it is expected that ‘with the cross-indigenous approach, not only can universal regularities be discovered, but also the total range of a phenomenon investigated is increased’ (Kim & Berry,

Philosophical reflection on IP 13

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology 1993, p. 11), there are still some doubts about ‘how such an integration of knowledge derived in different cultural systems [can] actually be realized’ (Poortinga, 1997, p. 361). Even Enriquez (1993) himself admitted ‘cross-cultural psychology will remain a promise so long as indigenous psychologies remain untapped because of language and cultural barriers’ (p. 154).

V. 3. Metatheory approach

Indigenous psychologists argue that blindly adopting imported foreign theories may result in the pitfall of ethnocentrism, because they contain many concepts that are strange to the target culture. But, Ho (1988; 1998) argued that relying on indigenous concepts alone might also lead to similar difficulty, and would not eliminate the fundamental predicament of culturocentrism. Ho distinguished theories along an indigenous-exotic dimension (Ho, 1998). Indigenous theories are constructed on the basis of values and concepts of the target culture; they represent the viewpoint of insiders. In contrast, exotic theories are produced with values and concepts alien to the target culture and represent the viewpoint of outsiders. In order to eliminate the potential incongruence of various theories, Ho proposed the development of a metatheory by comparing indigenous and exotic theories in terms of contents, theorists and cultures.

His approach also implies the potential difficulty of using an inductive approach. Ho’s metatheory thus constructed is just a mini-metatheory. ‘It may be expanded for multicultural and even holocultural studies in which the target universe includes all known cultures in the whole world’ (Ho, 1998, p. 93). Ho’s proposal raises the question: To what extent should the target universe of such a mini-metatheory be expanded to include all known cultures in the whole world?

V. 4. Cross-cultural indigenous psychology

K.S. Yang (1993) supported the distinction between exogenous indigenization and endogenous indigenization, or indigenization from without and indigenization from within made by Enriquez (1989). He argued that the psychology established by the exogenous indigenization approach adopts culture and history from other societies (usually Western countries), but not their own as the origin of thinking. It is roughly a kind of ‘deformed Western psychology’, and fails to represent validly the characteristics and genuine phenomena of local society, culture and history. What he means by indigenous psychology is restricted to ‘endogenous indigenous psychology’ (Yang, 1993, p. 44).

Yang further divided indigenous psychology into monocultural indigenous psychology and cross-cultural indigenous psychology, and argued that Westernized or Americanized psychology is also a kind of monocultural indigenous psychology. The construction of regional psychological theories cannot merely rely on monocultural indigenous studies, but must integrate related knowledge from several indigenous psychologies through cross-cultural indigenous studies (Yang, 1997; 2000).

At first glance, Yang’s arguments are very similar to Enriquez’s. But, Yang went on to discuss the integration procedure from the perspectives of content and approach. So far as content is concerned, he proposed two types of integration, namely, empirical and theoretical. Empirical integration ‘rests mainly on the common characteristics (components, processes, constructs, structures or patterns) and functions shared by all the compared indigenous psychologies’ (Yang, 2000, p. 258).

14 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology With respect to theoretical integration, Yang said,

If a psychological theory is able to adequately understand, explain and predict psychological and behavioral phenomena in a certain domain across two or more cultures, it may be said that the theory integrates the phenomena in that domain for those cultures. (Yang, 2000, p. 258)

His proposal is very similar to the derived etic approach advocated by Barry. But the question remains, with insistence on the cross-cultural indigenous psychology approach, who would be able to construct a theory to integrate the common characters and functions shared by all the compared indigenous psychologies?

VI. Conclusion

With consideration of the dramatic changes in philosophy of science in the shift from positivism to post-positivism, the present paper has critically reviewed the controversial issues of epistemology and methodology for indigenous psychology that have occurred in its history of progress. It has also proposed an epistemological strategy for its future development from the perspective of post-positivism, advocating the deductive approach of constructing formal theories to describe the psychological functioning of the universal human mind with critical rationality (Popper, 1963) or creative imagination (Hempel, 1966), and then using these theories to explain the mentality of people in a given cultural tradition. Theoretical models thus obtained can be used as conceptual frameworks for conducting empirical research in that culture.

A feasible way to carry out such a research program is to take a major non-Western cultural group, for instance, Confucian, Muslim or Buddhist groups, as the target for analysis, because these groups are highly distinctive and are composed of a relatively large percentage of the population of the world. The theoretical models thus constructed would represent ideal types of psychology and behavior in that particular cultural tradition. The models might be different from behaviors of people as manifested in their daily lives. Nevertheless, a researcher may use them as conceptual frameworks, taking into consideration the antecedent conditions of the particular society, and deriving some hypothesis of the psychology and behaviors in a specific domain using the deductive method (Hempel, 1965) and conducting empirical research in that society. This approach advocates a systems view of culture, and it asks the researcher to develop culturally dependent models that illustrate functional relations among variables in different domains (Kitayama, 2002), or to adopt a contextually grounded view for studying cultural impact on psychological functioning (Miller, 2002).

Indigenous psychologists who adopt this approach should not ignore the impact of modernization in their theoretical construction, deductive reasoning or research design. On this point, I highly agree with Yang’s perspective: ‘modernization is a worldwide societal phenomenon that has gradually made people in non-Western societies acquire an increasing number of psychological and behavioral characteristics typical of people in industrialized societies’ (Yang, 2000, p. 260). When indigenous psychologists construct a knowledge system, they must accommodate the psychological knowledge of Western industrialized societies to interpret the newly acquired psychological characteristics.

Based on such a belief, I constructed a theoretical model of Face and Favor on the philosophical basis of scientific realism (Hwang, 1987). This formal model is supposed to be applicable to various cultures. Using the model as a framework, I analyzed the deep structure

Philosophical reflection on IP 15

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology of Confucianism by the method of structuralism (Hwang, 1988), which enables understanding of the Confucian cultural heritage from the perspective of social psychology. After that, I analyzed the Chinese cultural traditions of Daoism, Legalism and the Martial school, and published these analyses along with my previous works in a book entitled Knowledge and Action (Hwang, 1995).

Based on the philosophy of constructive realism, I integrated my previous works and proposed a series of theoretical models on Confucian relationalism (Hwang, 2000; 2001), and used them as frameworks to conduct empirical research on moral thoughts (Hwang, 1998; 1999), favor request (Han et al., in press), the concept of face (Hwang, in press) and conflict resolution in Chinese societies (Hwang, 1997–8). It is expected that this approach might provide a new paradigm for the development of indigenous psychologies in various areas of the world.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written while the author was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Republic of China 89-H-FA01-2-4-2 and 93-2752-H-002-001-PAE.

References

Adair, J. G., Puhan, B. N. & Vohra, N. (1993). Indigenous of psychology: Empirical assessment of progress in Indian research. International Journal of Psychology, 28, 149–169.

Azuma, H. (1984). Psychology in a non-Western culture: The Philippines. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 272–292.

Berry, J. W. (1969). On cross-cultural comparability. International Journal of Psychology, 4, 119–128. Berry, J. W. (1989). Imposed etics-emics-dervied etics: The operationalization of a compelling idea.

International Journal of Psychology, 24, 721–735.

Berry, J. W. (1993). Psychology in and of Canada: One small step toward a universal psychology. In: U. Kim & J. W. Berry, eds. Indigenous Psychologies: Research and Experience in Cultural Context, pp. 260–275. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Berry, J. W. & Kim, U. (1993). The way ahead: From indigenous psychologies to a universal psychology. In: U. Kim & J. W. Berry, eds. Indigenous Psychologies: Research and Experience in Cultural Context, pp. 277–280. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H. & Dasen, P. R. (1992). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diaz-Guerrero, R. (1975). Psychology of the Mexican: Culture and Personality. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Enriquez, V. (1977). Filipino psychology in the third world. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 10, 3–18. Enriquez, V. (1981). Decolonizing the Filipino Psyche. Quezon City: Psychology Research and Training

House.

Enriquez, V. (1989). Indigenous Psychology and National Consciousness. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

Enriquez, V. (1993). Developing a Filipino psychology. In: U. Kim & J. Berry, eds. Indigenous Psychologies: Research and Experience in Cultural Context, pp. 152–169. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Han, K. H., Li, M. C., & Hwang, K. K. (in press). Cognitive responses to favour request from social targets of different relationships in a Confucian society. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships.

16 Kwang-Kuo Hwang

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

Hempel, C. G. (1966). Philosophy of Natural Science. Englewood Cliff, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Hermans, J. M. & Kempen, J. G. (1998). Moving cultures: The perilous problem of cultural dichotomy

in a globalized society. American Psychologiset, 53, 1111–1120.

Ho, D. Y. F. (1988). Asian psychology: A dialogue on indigenization and beyond. In: A. C. Paranjpe, D. Y. F. Ho & R. W. Rieber, eds. Asian Contributions to Psychology, pp. 53–77. New York: Praeger. Ho, D. Y. F. (1998). Indigenous psychologies: Asian perspectives. Journal of Cross-Cultural

Psychology, 29, 88–103.

Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 944–974.

Hwang, K. K. (1988). Confucianism and East Asian Modernization. Chu-Lin Book Co. (in Chinese). Hwang, K. K. (1995). Knowledge and Action: A Social-Psychological Interpretation of Chinese Cultural

Tradition. Taipei: Sin-Li (in Chinese).

Hwang, K. K. (1997–8). Guanxi and mientze: Conflict resolution in Chinese society. Intercultural Communication Studies, 3, 17–37.

Hwang, K. K. (1998). Two moralities - Reinterpreting the finding of empirical research on moral reasoning in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 211–238.

Hwang, K. K. (1999). Filial piety and loyalty: The types of social identification in Confucianism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 129–149.

Hwang, K. K. (2000). On Chinese relationalism: Theoretical construction and methodological considerations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 30, 155–178.

Hwang, K. K. (2001). The deep structure of confucianism: A social psychological approach. Asian Philosophy, 11, 179–204.

Hwang, K. K. (in press). Moral face and social face: Contingent self-esteem in Confucian society. International Journal of Psychology.

Kim, U. (2000). Indigenous, cultural, and cross-cultural psychology: A theoretical, conceptual, and epistemological analysis. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 265–287.

Kim, U. & Berry, J. (1993). Introduction. In: U. Kim & J. Berry, eds. Indigenous Cultural Psychologies: Research and Experience in Cultural Context, pp. 1–29. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kim, U., Park, Y. S. & Park, D. (2000). The challenger of cross-cultural psychology: The role of the indigenous psychologies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 63–75.

Kitayama, S. (2002). Culture and basic psychological processes-toward a system view of culture. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 89–96.

Kwon, T. H. (1979). Seminar on Koreanizing Western approaches to social sciences. Korea Journal, 19, 20–25.

Legmay, A. V. (1984). Western psychology in the Philippines: Impact and response. International Journal of Psychology, 19, 31–44.

Mehryar, A. (1984). The role of psychology in national development: Wishful thinking and reality. International Journal of Psychology, 19, 159–167.

Miller, J. G. (2002). Bringing culture to basic psychological theory-beyond individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 97–109.

Moscovici, S. (1972). Society and theory in social psychology. In: J. Israel & H. Tajfel, eds. The Context of Social Psychology. London: Academic.

Poortinga, Y. H. (1996). Indigenous psychology: Scientific ethnocentrism in a new guise? In: J. Pandey, D. Sinha & D. P. S. Bhawuk, eds. Asian Contributions to Cross-Cultural Psychology, pp. 59–71. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Poortinga, Y. H. (1997). Towards convergence. In: J. W. Berry, Y. H. Poortinga, J. Pandey et al., eds. Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology, 2nd edn, Vol. 1, pp. 347–387. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Poortinga, Y. H. (1999). Do differences in behavior imply a need for different psychologies? Applied

Psychology: An International Review, 48, 419–432.

Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Philosophical reflection on IP 17

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology

Schlick, M. (1936). Meaning and verification. Philosophical Review, 45, 339–369.

Shiraev, E. & Levy, D. (2001). Introduction to Cross-Cultural Psychology. London: Allyn and Bacon. Shweder, R. A. (1996). The ‘mind’ of cultural psychology. In: P. Baltes & U. Staudinger, eds. Interactive Minds: Life-Span Perspectives on the Social Foundations of Cognition, pp. 430–436. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shweder, R. A. (2000). The psychology of practice and the practice of the three psychologies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 207–222.

Shweder, R. A., Goodnow, J., Hatano, G., LeVine, R., Markus, H., & Miller, P. (1998). The cultural psychology of development: One mind, many mentalities. In: W. Damon, ed. Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1, pp. 865–937. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sinha, D. (1986). Psychology in a Third World Country: The Indian Experience. New Delhi: Sage. Triandis, H. C. (2000). Dialectics between cultural and cross-cultural psychology. Asian Journal of

Social Psychology, 3, 185–195.

Wallner, F. G. & Jandl, M. J. (2001). The Importance of Constructive Realism for the Indigenous Psychologies Approach. Paper Presented at Scientific Advances in Indigenous Psychologies: Philosophical, Cultural, and Empirical Contributions; 29 October-1 November 2001. Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica.

Wittgenstein, L. (1922/1961). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (D. F. Pears & B.F. McGuinnies, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Yang, K. S. (1993). Why do we need to develop an indigenous Chinese psychology? Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 1, 6–88 (in Chinese).

Yang, K. S. (1997). Indigenous compatibility in psychological research and its related problems. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 8, 75–120 (in Chinese.).

Yang, K. S. (1999). Towards an indigenous Chinese psychology: a selective review of methodological, theoretical, and empirical accomplishments. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 41, 181–211. Yang, K. S. (2000). Monocultural and cross-cultural indigenous approaches: The royal road to the