New Millennium

Hong Kong Banking Sector

Consultancy Study – Detailed Recommendations

December 1998

Contents

Preface 2

1 Banking regulatory review and recommendations 4

1.1 Introduction 4

1.2 The three-tier system 6

1.3 The one-building condition 15

1.4 Market entry criteria 19

1.5 Financial disclosure 33

1.6 Depositor protection 36

1.7 Lender of last resort 44

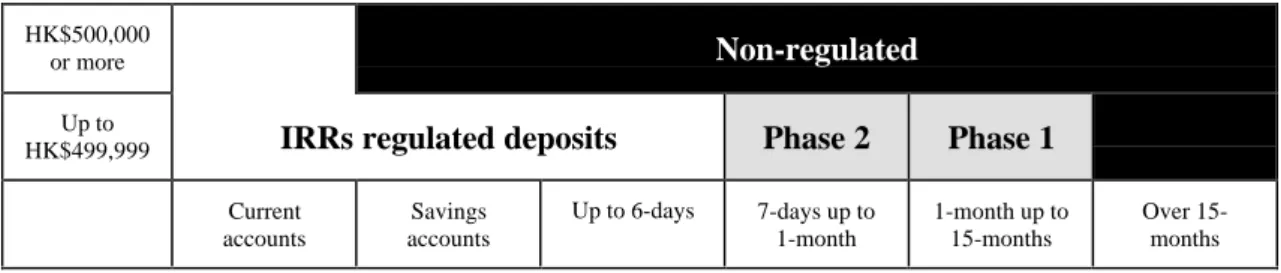

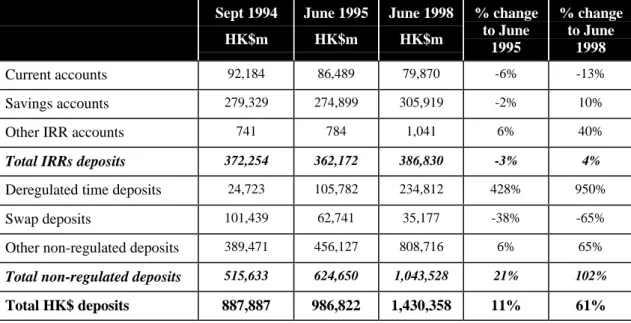

1.8 Interest Rate Rules 48

1.9 Conclusions 72

2 Supervisory review and recommendations 75

2.1 Introduction 75

2.2 The HKMA’s transition to risk-based supervision 77

2.3 Framework for assessment 79

2.4 Assessment methodology 84

2.5 Current profile of the HKMA 85

2.6 Comparison with benchmark countries 100

2.7 Supervisory implications of global banking trends 109

2.8 Conclusions and recommendations 118

2.9 Summary of assessment and recommendations 137

3 Roadmap for regulatory and supervisory change 141

3.1 Introduction 141

3.2 Change management issues 143

3.3 Implementation approach 144

Appendix 1 - Assumptions and results of scenarios in the financial sensitivity model

Preface

This document has been compiled from a report produced by KPMG and Barents Group LLC (the “Consultants”) entitled “Hong Kong Banking into the New Millennium – Hong Kong Banking Sector Consultancy Study” (“Consultancy Report”).

This document contains details of the recommendations on the HKMA’s regulatory and supervisory framework made by the Consultants based on a strategic review of the Hong Kong banking sector conducted during 1998. This review included an assessment of banks in Hong Kong and the banking sector as a whole in light of the forces and trends occurring in global financial markets. An outline of the review and the assessment was included in the Executive Summary to the Consultancy Report which was published on 18 December 1998. Readers should refer to the Executive Summary for a description of the general background against which the recommendations have been made.

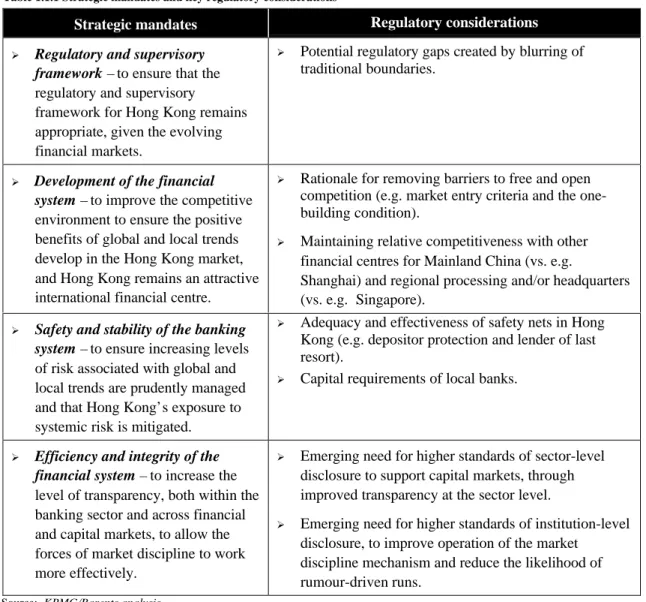

Overall, the Consultants found that the strategic assessment of the banking sector and the changing financial landscape suggest four mandates that need to be considered in improving the HKMA’s regulatory and supervisory framework:

Strategic mandates to improve the HKMA’s regulatory and supervisory framework

Strategic mandates Regulatory and supervisory considerations

Ø Regulatory and supervisory framework – to ensure that the regulatory and supervisory framework for Hong Kong remains appropriate, given the evolving financial markets.

Ø Potential regulatory and supervisory gaps created by blurring of traditional boundaries.

Ø Need for increased supervisory co-operation and harmonisation across functional areas.

Ø Reaction to the introduction of a broad array of new products and delivery channels.

Ø Increasing linkage between Hong Kong and other Asian banking, financial and capital markets.

Ø Development of the financial system – to improve the competitive environment to ensure the positive benefits of global and local trends develop in the Hong Kong market, and Hong Kong remains an attractive international financial centre.

Ø Rationale for removing barriers to free and open competition (e.g. market entry criteria and the one- building condition).

Ø Potential implications of more open competition on smaller local market participants (e.g. removal of the remaining IRRs).

Ø Need to address/react to merger activity.

Ø Increasing economic integration with Mainland China.

Ø Ability of local banks to access Mainland China.

Ø Maintaining relative competitiveness with other financial centres for Mainland China (vs. e.g.

Shanghai) and regional processing and/or headquarters (vs. e.g. Singapore).

Ø Safety and stability of the banking system – to ensure increasing levels of risk associated with global and local trends are prudently managed and that Hong Kong’s exposure to systemic risk is mitigated.

Ø Adequacy and effectiveness of the HKMA’s risk- based approach to supervision.

Ø Adequacy and effectiveness of safety nets in Hong Kong (e.g. depositor protection and lender of last resort).

Ø Adequacy of risk management capabilities of local banks.

Ø Response to likely increase in remote processing and outsourcing arrangements.

Ø Capital requirements of local banks.

Ø Potential increased exposure to property market.

Ø Efficiency and integrity of the financial system – to increase the level of transparency, both within the banking sector and across financial and capital markets, to allow the forces of market discipline to work more effectively.

Ø Emerging need for higher standards of sector-level disclosure to support capital markets, through improved transparency at the sector level.

Ø Emerging need for higher standards of institution- level disclosure, to improve operation of the market discipline mechanism and reduce the likelihood of rumour-driven runs.

Source: KPMG/Barents analysis

The following two sections provide specific recommendations for evolving the HKMA’s regulatory (Section 1) and supervisory (Section 2) frameworks, while Section 3 provides a road map or approach for change.

1.1 Introduction

The banking environment is dynamic in nature and changes will always be occurring as developments affecting market conditions take place. Consequently, banking regulations and structures also need to adapt to market conditions to ensure that policy objectives are appropriate and consistent with the developing market. The pace of change in the global banking sector, and in Hong Kong, is very rapid and this pace of development appears likely to continue in the near future. As an international financial centre, these developments particularly affect Hong Kong because of the sophisticated transactions being engaged in by banks (to varying degrees) operating locally. Hong Kong faces the dual challenge of determining what policies are most appropriate in the short, medium and long-term, and how its policies can ultimately preserve and enhance its position as a recognised international financial centre.

The impact of the Asian crisis is not only being seen in Hong Kong through a rise in non-performing loans, but also in the number of overseas banks wishing to undertake business here. A number of foreign banks are withdrawing their operations and there are fewer seeking to establish operations in Hong Kong through licence applications. In addition, competition from other financial centres in the region is increasing, either as a result of financial sector deregulation or government incentives to attract business. It is therefore important that existing banking regulations be viewed from the perspective of increasing the attractiveness of Hong Kong as an international financial centre, as well as improving any weaknesses in the market.

Through the strategic review and the assessment of the Hong Kong banking sector, we identified certain specific issues, which needed more in-depth study and analysis.

These issues all relate to areas where we consider that the sector as a whole (not individual banks) is affected and where we suggest the HKMA has a mandate to improve overall banking sector regulation. Regulatory issues and the underlying mandates to which they are linked are set out below (see Table 1.1.1):

1 Banking regulatory review and recommendations

Table 1.1.1 Strategic mandates and key regulatory considerations

Strategic mandates Regulatory considerations

Ø Regulatory and supervisory framework – to ensure that the regulatory and supervisory

framework for Hong Kong remains appropriate, given the evolving financial markets.

Ø Potential regulatory gaps created by blurring of traditional boundaries.

Ø Development of the financial system – to improve the competitive environment to ensure the positive benefits of global and local trends develop in the Hong Kong market, and Hong Kong remains an attractive international financial centre.

Ø Rationale for removing barriers to free and open competition (e.g. market entry criteria and the one- building condition).

Ø Maintaining relative competitiveness with other financial centres for Mainland China (vs. e.g.

Shanghai) and regional processing and/or headquarters (vs. e.g. Singapore).

Ø Safety and stability of the banking system – to ensure increasing levels of risk associated with global and local trends are prudently managed and that Hong Kong’s exposure to systemic risk is mitigated.

Ø Adequacy and effectiveness of safety nets in Hong Kong (e.g. depositor protection and lender of last resort).

Ø Capital requirements of local banks.

Ø Efficiency and integrity of the financial system – to increase the level of transparency, both within the banking sector and across financial and capital markets, to allow the forces of market discipline to work more effectively.

Ø Emerging need for higher standards of sector-level disclosure to support capital markets, through improved transparency at the sector level.

Ø Emerging need for higher standards of institution-level disclosure, to improve operation of the market

discipline mechanism and reduce the likelihood of rumour-driven runs.

Source: KPMG/Barents analysis

In reviewing the regulation of the sector as a whole it is necessary to consider:

Ø whether all the elements of the current regulatory regime are still appropriate to this developing market and will, in their present form, continue to fulfil policy requirements; and

Ø whether the bank regulations and supervisory processes in Hong Kong are consistent with those in other global financial centres.

In performing this study, we were requested to review four specific policies1 and the regulations implementing them. Other regulatory issues that emerged during the course of our work were also considered. The views of market participants, on each of the four policies that were reviewed, have been incorporated, including the implications of change that were discussed in interviews. In addition, research was conducted on each policy area and related issues and international comparisons made.

1 The four policies required to be reviewed were the three-tier system, market entry criteria, the one-building condition and the remaining interest rate rules of the HKAB.

1.2 The three-tier system 1.2.1 Background

The original three-tier system (banks, licensed deposit takers and registered deposit takers) came into being in 1981 with the enactment of the Deposit Taking Companies (Amendment) Ordinance (updated in 1990). This ordinance was introduced in response to market conditions and, in particular, the activities of deposit-taking companies (“DTCs”) which, at that time, were not bound by the agreed interest rates set by banks.

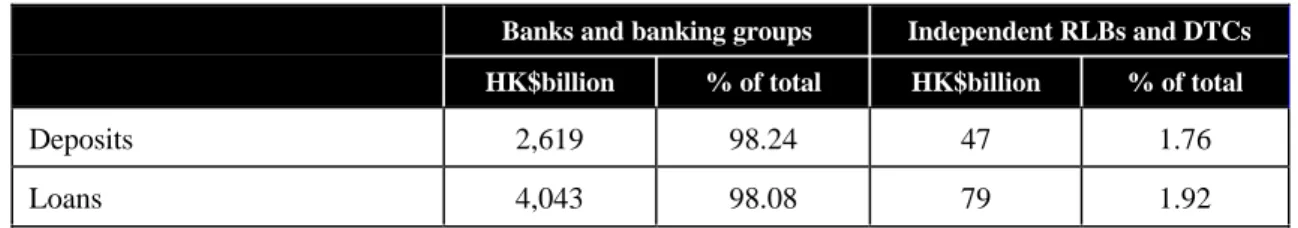

At that time, independent RLBs and DTCs took a significant proportion of deposits (approximately 30%).

Since then, the contributions to the banking system from independent RLBs and DTCs have reduced significantly. They now account for less than 2% of the market in terms of both loans and deposits (see Table 1.2.1). This reduced importance to the sector needs to be taken into account in considering the structure of the market.

Table 1.2.1 Deposits and loans – banks and banking groups vs. independent RLBs and DTCs

Banks and banking groups Independent RLBs and DTCs HK$billion % of total HK$billion % of total

Deposits 2,619 98.24 47 1.76

Loans 4,043 98.08 79 1.92

Note : Banking groups include banks and their subsidiary RLBs and DTCs.

Source : HKMA as at December 1997

The policy objectives of the three-tier system are as follows:2

“(a) maximising the banking system’s contribution to Hong Kong’s prosperity by providing a framework within which banks and DTCs can operate profitably, generate employment and channel savings into the productive economy

(b) enhancing the government’s ability to effect its monetary policy (c) providing protection for depositors.”

The second policy objective appears to have been overtaken by market developments and monetary reforms introduced since the mid-1980s3. The partial deregulation of the interest rate rules has reduced the ability of the government to ensure the effectiveness of the interest rate rules of the HKAB as an instrument of macro economic policy4 (see Section 1.8).

2 Paper by the Office of the Commissioner of Banking entitled The Three-Tier System – Proposals for change to the structure, May 1988.

3 Examples of reforms include new accounting arrangements, issuance of Exchange Fund papers, establishment of the LAF (now discount window) and the RTGS.

4 DTCs were allowed to compete freely for deposits 3-months or more for amounts of HK$100,000 or more, while banks could not. This has changed following partial deregulation and banks may now compete freely for deposits from seven days.

1.2.2 Assessment of the three-tier system Strengths

The three-tier system provides a measure of protection to depositors by directing small deposits to banks (i.e. those less than HK$100,000) and, as a consequence, 98% of all deposits in Hong Kong are placed with banks or banking groups (i.e. banks and their subsidiary RLBs and DTCs). Although all authorized institutions are subject to a uniform prudential framework under the Banking Ordinance, those institutions deemed by the HKMA to be unqualified to participate fully in the retail deposit market are appropriately restricted by limiting their market access. Banks, which are required to meet more stringent standards (e.g. minimum capital), are in practice subject to more focused supervisory attention and are the only institutions allowed to undertake banking business.

Despite the limitations on RLBs and DTCs in terms of deposit taking, the three-tier system does allow specialist consumer finance companies and hire purchase/leasing financiers to offer services targeted at specific groups of customers, whose needs might not have been necessarily met by the banks.

The three-tier system also provides a flexible means of entry to the Hong Kong banking market in that overseas banks, which do not meet the entry criteria for fully licensed banks, have the option of entering as DTCs or RLBs. This provides a means for the HKMA to permit new participants, who may not fully meet the criteria to enter as a bank because they do not meet minimum assets size criterion of US$16billion, to enter the market, albeit at a restricted level (see Section 1.4).

By licensing these institutions as RLBs or DTCs, the HKMA is able to assess management of these institutions over a period of time before issuance of more permissive licences. More importantly, some of these institutions may be encouraged to enter as a locally incorporated RLB or DTC to enable the HKMA to exercise more direct prudential control through capital adequacy requirements and large exposure limits.

In addition, the policy of allowing only banks to take deposits of less than HK$100,000 matches the current depositor protection scheme, whereby small depositors (less than HK$100,000) become preferred creditors in the event of the liquidation of a bank.

Weaknesses

In Hong Kong, there is a considerable number of RLBs and DTCs (91) that are owned by either local banks (23) or foreign banks (68) that also have a full banking licence (see Table 1.2.2):

Table 1.2.2 Ownership of RLBs and DTCs in Hong Kong

Owned by a local bank

Owned by a foreign bank in

Hong Kong

Owned by a foreign bank not

in Hong Kong

Independent Total

RLBs 3 22 32 8 65

DTCs 20 46 35 11 112

Total 23 68 67 19 179

Source: HKMA as at June 1998

Due to the fact that there are no restrictions on banks for conducting banking business and taking deposits, there would appear to be little value for banks to maintain separate subsidiary RLBs or DTCs, especially with the deregulation of the interest rate rules down to and including seven-day deposits. However, the reasons given by banks for keeping these additional regulated entities include:

Ø the original purpose for establishing these institutions was to compete against DTCs for deposits which were previously not covered by the IRRs5 and they saw no need to revoke these licences;

Ø these subsidiaries are used for specialised financial services, such as private banking, finance leasing and hire purchase;

Ø some of these institutions have been acquired and the licences maintained;

Ø some of these institutions are joint ventures with other parties; and

Ø they are concerned that if they surrender the licence they will not be able to obtain another one easily in the future.

However, the fact that there are 91 subsidiary RLBs and DTCs, that are authorized to take deposits, requires at least a minimum amount of supervisory resources to be devoted to such entities. This represents a duplication of effort on the part of both the HKMA (to supervise compliance) and the sector (in terms of efforts expended to meet prudential requirements). As an example, the 91 institutions submit some 1,200 statistical returns to the HKMA every year, although the cost of this additional supervision is recovered to an extent through the licence fees.

The three-tier system was created in reaction to market conditions in the early 1980s.

This has resulted in a licensing structure that is, to a certain extent, not fully in line with the policy of protecting depositors. Under the current licensing structure, DTCs have

5 The IRRs now only cover 27% of Hong Kong dollar deposits and 14% of total deposits.

greater access to small deposits than RLBs, even though they are not required to hold as much paid-up capital. DTCs are, however, are required to meet the same capital adequacy ratio requirements as RLBs. This is at odds with the normal expectation that access to smaller deposits would increase in line with the grade of licence and entry requirements (i.e. minimum capital requirements) (see Table 1.2.3 below):

Table 1.2.3 Minimum capital requirements and access to deposits

Minimum capital requirements

Access to deposits as currently exists in Hong

Kong

Access to deposits if it was in line with minimum capital

requirements

Banks HK$150million No restrictions No restrictions

RLBs HK$100million HK$500,000 and above HK$100,000 and above

DTCs HK$25million HK$100,000 and above

with maturity of 3-months or more

HK$500,000 and above

Source: HKMA

A further point to note is that although RLBs and DTCs provide competition to banks for the provision of financial products and services, this competition (and consequently their market share) is restricted. In particular, the fact that DTCs cannot offer deposits with less than three months maturity is a key limitation when viewed in the context that, in Hong Kong, the maturity structure of the retail deposit base is predominantly less than three months.

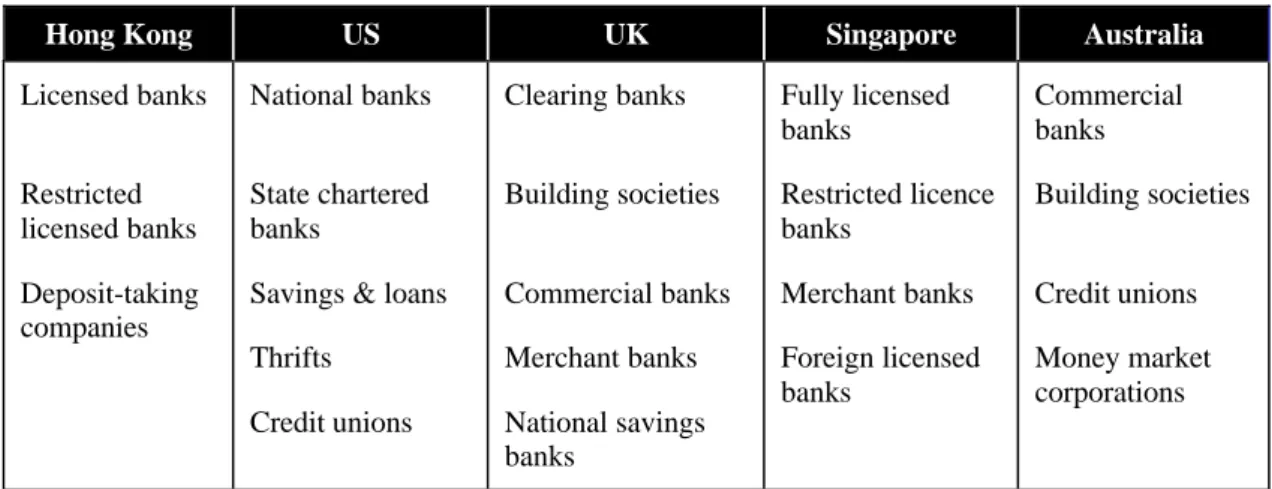

1.2.3 Comparison with other international financial centres

Hong Kong, as with other international financial centres, has a tiered licensing system for its deposit-taking institutions (see Table 1.2.4):

Table 1.2.4 Comparison to other international factor centres

Hong Kong US UK Singapore Australia

Licensed banks

Restricted licensed banks Deposit-taking companies

National banks

State chartered banks

Savings & loans Thrifts

Credit unions

Clearing banks

Building societies

Commercial banks Merchant banks National savings banks

Fully licensed banks

Restricted licence banks

Merchant banks Foreign licensed banks

Commercial banks

Building societies

Credit unions Money market corporations

Source: KPMG/Barents analysis

In each of these countries, the business activities of different institutions vary and reflect the development of their respective financial markets. However, there is increasingly a trend towards unitary licensing systems which reflects the blurring of

financial markets globally. For example, in the US, there are several classes of depository institutions but there is little to distinguish between them and there are initiatives towards a unitary system.

1.2.4 Views of market participants

There do not appear to be strong views among respondents on whether the structure of the three-tier system should be changed. A significant number of institutions (45%) had no opinion on this with the others being evenly divided over this issue. The view on whether to change to a two tier system (in which DTCs and RLBs are merged into a single type of authorized institution) was also inconclusive, with 50% of institutions having no opinion.

On the other hand, a majority (61%) of respondents considered that the three-tier system promotes stability in the banking sector, with the figure being higher for locally incorporated licensed banks (75%) and multi-branch foreign banks (74%). Furthermore, 64% of institutions agreed that the three-tier system provides a flexible means for new entrants to enter the banking sector and this opinion was consistent across all types of institutions.

The three-tier system is generally thought to provide protection to small depositors with 51% of institutions having this view. This figure was higher for locally incorporated banks (64%) and multi-branch foreign banks (74%). A majority of locally incorporated banks (75%) and multi-branch foreign banks (61%) are firmly against lifting or relaxing the present prohibitions on DTCs and RLBs to take short-term and smaller deposits. In contrast 60% of RLBs and DTCs are in favour of this.

Overall, 76% of respondents believed that their current class of licence was adequate for their business plans for the next five years. The only class of respondents who did not believe that their licences were adequate were foreign RLBs, where a significant number (41%) did not believe so.

Views expressed in the interviews were generally more in favour of change. A number of institutions commented that the system was complex and confusing (to institutions, their customers and to overseas interests) and was the result of a convoluted history of banking development in Hong Kong. In general, banks are supportive of a review of the system but consider that, if there were to be any developments to the three-tier system, it should be a comprehensive exercise rather than a small incremental change.

1.2.5 Future considerations

The three-tier system may appear outdated as the world moves increasingly towards unitary licensing policies. However, a tiered approach in Hong Kong is necessary because all banks are allowed full access to the retail market. A tiered system can distinguish banks qualified (i.e. those that meet existing authorization criteria) to accept small deposits from institutions that should be restricted to other types of deposits for prudential reasons. An appropriate set of policy objectives to address this need would be to provide:

Ø a framework which allows a broad range of domestic and international institutions to participate in the Hong Kong banking sector; and

Ø protection for small depositors.

Such a licensing system (combined with market entry criteria) puts the onus on foreign banks to be of sufficient size to demonstrate expertise, competence and experience in international affairs under market conditions in order to qualify as fully licensed banks in Hong Kong. In the wake of banking sector problems elsewhere in the region, including in advanced economies such as in Japan, a tiered licensing system providing limited access for certain foreign institutions would appear prudent for the time being.

Despite this, there are problems associated with the current three-tier approach:

Ø First, the system is complex and there is a significant duplication of licences (i.e.

banks have 91 separately regulated subsidiaries), which is not in itself efficient for the sector.

Ø Second, the structure of access to smaller deposits is not in line with the minimum capital requirements, although this is to an extent mitigated by the deposit maturity limitations on DTCs (i.e. deposits must be for 3-months or more).

Ø Third, while the HKMA needs to monitor exposure and linkages in portfolios that could pose greater risk than is evident from just market share, there does not appear to be a strong need to maintain a separate third tier for institutions holding such a small market share (i.e. less than 2% in total).

In the past, the three-tier system has provided the HKMA with a means of segmenting the market and providing licensing discretion in support of safe and stable banking.

However, going forward, the need to distinguish RLBs from DTCs no longer appears necessary in view of market developments, the forces affecting the banking sector and the resultant trends (i.e. the blurring of financial markets and consolidation).

Recommendations

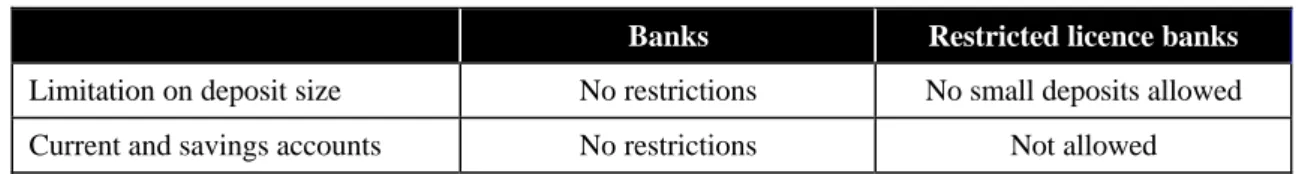

Simplifying the three-tier system to address these issues appears to be a logical way forward for Hong Kong as an international financial centre. We also consider that the policy objective of protecting depositors and therefore the general stability of the sector can be achieved more efficiently through a simplified structure. Accordingly, we recommend that the HKMA consider converting the licensing system to a two-tier system, an example of which is outlined below (see Table 1.2.5):

Table 1.2.5 Recommended two-tier system

Banks Restricted licence banks Limitation on deposit size No restrictions No small deposits allowed

Current and savings accounts No restrictions Not allowed

Source: KPMG/Barents analysis

Although there is an international trend towards unitary bank licensing systems, the diversity of foreign banks in Hong Kong and the consequent need to distinguish between these is best achieved with a tiered system. In the proposed two-tier system, the licensed bank and restricted licence bank categories are maintained as authorized institutions and the DTC category would be eliminated (i.e. DTCs would be precluded from taking deposits). The essential distinctions between the two tiers are:

Ø the ability to conduct banking business (i.e. offer current and savings accounts); and

Ø access to small deposits.

This tiered system would provide a framework which allows both a flexible means of entry to the banking market to attract new overseas participants and, at the same time, provide a measure of protection to small depositors.

The key issue with this two-tier approach is the definition of small deposits, as this affects the depositor protection aspects of the system. There are essentially two main option which can be considered in defining small deposits:

Ø Option 1 - an amount based on a study of the current deposit market (i.e. the distribution of account balances) which could be adjusted for inflation on a periodic basis; or

Ø Option 2 - a fixed amount of HK$500,000 (i.e. the current distinction between the deposits that banks and RLBs can accept).

Implications of change

For Option 1, the distribution of accounts should be collected from the 40 main deposit- taking banks and an assessment made to determine an appropriate definition for small deposits. Given the passage of time, it is unlikely that the 1980 amount of HK$100,000 would be an appropriate distinction between banks and RLBs under the proposed two- tier structure6. Performing this review and setting the definition for small deposits would take account of inflation since the original introduction of the three-tier system and the current behavioural patterns of consumers’ savings.

Although this amount should be periodically reviewed and adjusted to reflect inflation and changes in consumer behaviour, there is a practical issue in that deposits held by RLBs below the revised minimum would need to be run-off. Therefore, to minimise

6 For example, inflation for the period from 1980 to 1997 was approximately 460% compounded.

practical complexities relating to the run-off of deposits, it would be appropriate to only change this definition when there has been a significant change in value.

The limit in Option 2 of HK$500,000 was originally set in 1980, when the three-tier system was introduced. The main advantages in using this limit are that it is already well known to the market and would maintain the current level of access by RLBs to retail deposits. Therefore, there is unlikely to be a significant impact on the overall level of competition and the stability in the market.

Another aspect to consider in deciding between these options is that access to the small deposit market (i.e. less than HK$100,000) currently matches the depositor protection scheme under the Companies Ordinance. This clearly distinguishes between deposits taken by banks and those taken by other authorized institutions (i.e. RLBs and DTCs are excluded). The policy objective of protecting small depositors under the three-tier system is thus consistent with that for depositor protection under the priority claims scheme. However, if small deposits are defined to be a higher amount, then a portion of these small deposits would not be covered by the priority payment scheme, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the licensing system to protect small depositors. In considering any change, the HKMA would therefore need to review whether these two should be kept in line to maintain consistency.

In deciding whether to change the existing three-tier system, the HKMA also needs to consider the following issues:

Ø The degree to which a two-tiered system could add to systemic risk in the marketplace. DTCs not wishing to upgrade would become unregulated finance companies (i.e. moneylenders) and their existing licences would need to be revoked.

Ø Currently, RLBs and DTCs face different restrictions on the use of the word bank in their names and the description under which they do business7. Therefore the HKMA will need to review this restriction in relation to the new second tier institutions, in particular those DTCs that upgrade.

Access to the RTGS system

A related issue, raised by a number of institutions and the Deposit-taking Companies Association in the course of our work, is the means used to determine access to the RTGS system. At present, all fully licensed banks are required to participate in the RTGS system and RLBs and DTCs are not permitted access. This limitation on access matches the distinction between fully licensed banks and other authorized institutions’

ability to perform banking business (i.e. only banks can operate current accounts), a de facto requirement of which is access to clearing and payment systems. A number of RLBs have noted that this places them at a competitive disadvantage in that they have to pay transaction processing fees to clearing banks for their settlement functions.

7 For example, DTCs may not use the word bank in their name. The picture for RLBs is more complex, refer Section 97 of the Banking Ordinance.

The principal reason for introducing RTGS systems world-wide8 was to help eliminate interbank settlement risk. In other countries, participation in these schemes is generally restricted to banks, deposit-taking institutions or other specified institutions (generally government agencies such as central banks). However, membership of such schemes is generally open to all such institutions (i.e. to all deposit-taking institutions or banks) rather than to only a subset. For example, in the US, the system is open to all depository institutions, federal government agencies and certain other institutions. In a few countries, however, access is restricted.

Given the emerging nature of financial markets, where authorized institutions are increasingly involved in securities transactions, restricting RLBs’ access may place them at a competitive disadvantage, given the significant amount of interbank transactions they may conduct as part of this business. In fact, it is apparent that certain RLBs’ business requirements can exceed those of some smaller banks in this regard.

There is no apparent reason in terms of systems capacity to restrict RLBs from having access to RTGS. In addition, the collateralised nature of the system effectively mitigates counterparty risk.

We have found no other reasons (theoretical or otherwise) that require access to RTGS to be set based solely on an institution’s licensing status. It may therefore be appropriate that this issue be reviewed in conjunction with a change towards a two-tier structure and a more appropriate means of defining access criteria should be considered.

For example, access could be based on objective criteria based on an institution’s business needs rather than licensing status.

8 For example, RTGS systems have now been implemented in Belgium, France, Japan, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the US and the UK.

1.3 The one-building condition 1.3.1 Background

The one-building condition limits foreign branch banks and foreign branch RLBs to carrying on their business from one building only (this effectively limits them to a single branch operation). Foreign branch banks subject to this condition may also maintain one back office and one regional office in separate buildings.

Consistent with the original policy objectives of the three-tier system, the one-building condition was devised to address the perceived dichotomy between competition and banking stability. At that time, there had been concerns that the proliferation of branches, and consequently increased competition, would introduce unwanted instability to the banking sector. Furthermore, foreign banks already accounted for a significant share of the retail market and their presence was likely to increase as more foreign banks applied for authorization. Therefore, a restriction on their branching capabilities and their access to the retail market was considered appropriate on grounds of stability.

Despite this restriction on new entrants, the one-building condition has had little impact on the number of foreign banks wishing to enter the Hong Kong market. For example, since 1978, the number of foreign banks has increased from 67 to 151. This is in part due to the opening up of the Mainland China market and also the fact that Hong Kong is an important centre for financing in the Asian region. The financing of trade-related business, capital raising activities, corporate and syndicated lending and offshore business do not require branch networks to the same degree as retail banking. As a result, the one-building condition has detracted little from the attractiveness of Hong Kong as a banking market to banks wishing to engage in wholesale (as opposed to retail) banking activities.

1.3.2 Assessment of the one-building condition

Foreign branch banks subject to the one-building condition are effectively limited from full participation in the retail market since they cannot develop branch networks.

However, despite this restriction, a number of these one-branch foreign banks have endeavoured to compete in certain areas of the retail market such as retail mortgages and credit cards. Nevertheless, the policy does limit the ability of new market entrants to set up and compete against the existing players. Therefore, in practice, the policy acts as a direct limitation to an open retail market and protects current participants from competition. This may act as a disincentive to consolidation.

In view of the effective block on foreign banks setting up locally incorporated banks, the only means for new market entrants to gain full access to the retail market is to acquire an existing player in the market. This situation in turn means that there is a perceived premium to be paid for a multi-branch banking licence, of which there are only a limited number available.

The one-building condition also places restrictions on banks’ abilities to effectively carry on their business in other areas. For example, certain banks may wish to locate different parts of their front office activities (e.g. treasury) in different buildings for a variety of reasons (e.g. during the transitional phase of relocating to new premises or to reduce costs).

The one-building condition effectively represents a restriction on delivery channels and can be circumvented with development of newer and more advanced delivery channels.

Although the policy takes into account ATMs, it does not restrict business conducted through new delivery channels such as the internet and phone banking. Hong Kong’s telecommunications infrastructure allows banks to provide electronic services to clients without the cost of a branch network. Continuing development of newer channels, especially internet and remote banking, is likely to make the one-building condition less of a barrier to retail banks without branch networks.

1.3.3 Views of market participants

A majority of respondents (63%) agreed that the one-building condition gives an advantage to those banks possessing a branching option and very few respondents (6%) actually disagreed with this. A majority (66%) of locally incorporated licensed banks and multi-branch foreign banks agreed that they had an advantage in this regard.

However, there was no clear response on whether the policy was a deterrent to market entry, where 36% thought that it was and 23% thought that it was not. Foreign branch RLBs were the only group of entities that had a majority opinion (53%) that the policy was a deterrent to market entry.

Although there was no clear opinion on whether the policy increased the stability of the banking sector, only 9% of respondents thought that the policy was detrimental to bank safety and soundness.

Even though the majority of respondents did not think that the one-building condition deterred entry to the market, over 62% stated that removing the policy would promote competition and only 3% disagreed with this. Additionally, 16 single-branch foreign banks (30%) considered that the policy had hurt their ability to compete, while 20 banks (37%) thought that it had limited the range of their products and services. These sentiments were confirmed in the interview process and there was general agreement that the policy was no longer relevant and that it should be removed to level the playing field.

Interestingly, although those institutions subject to the policy were vocal in their view that removing the one-building condition would promote competition (73%), only 12 institutions (20%) indicated that they would expand their branch network if the policy was eliminated. Virtually all of those who would expand their branch networks were single-branch foreign banks (11 institutions), the other institution being a foreign branch RLB. Of the 11 foreign banks seeking to expand branch networks, a noticeable trend was that four were Mainland China banks.

1.3.4 Future considerations

The one-building condition perpetuates an uneven playing field for banks in Hong Kong.

The concept of restricting foreign banks to a fixed number of buildings is inconsistent with a desire for open markets, especially when some foreign banks (16) are able to have branch networks and others are not.

The role of branches in a bank’s business is going through a period of rapid change, as new technology and product delivery channels develop and take over the some of the activities that were previously undertaken in branches. This is not to say that branches will become obsolete in the future but rather that their relevance to certain types of transactions may decrease significantly, whereas their significance in other activities may increase. For example, telephone banking and ATM networks have already significantly reduced cash based transactions, while investment advisory services are on the increase in branches.

All banks will therefore need to reassess the use for their branch networks and the cost effectiveness of maintaining them. In terms of market entry, the development of new delivery channels is likely to lower the barrier to entry that established branch networks represent.

Recommendations

The one-building condition no longer appears to be appropriate to Hong Kong and acts as a barrier to competition. At the same time, there is a risk that its removal could result in an increased level of competition that could be detrimental to banking stability.

Ultimately, we recommend that it should be removed completely to allow a level playing field for all participants and to allow banks to determine their level of investment in a branch network versus other delivery channels.

In order to minimise the risk of systemic instability, the HKMA could consider phasing in the relaxation of this policy. For example, foreign branch banks and foreign branch RLBs might be allowed to operate no more than three branches9 for a set period, with further relaxation of the policy subject to a review at that time.

Additionally, it is important that the HKMA maintains the requirement that the opening of new branches be subject to its approval so that a level of control can still be maintained.

9 If all foreign branch banks and RLBs subject to the existing one-building condition were to open two new branches, this would increase the number of branches in Hong Kong by approximately 13%.

Implications of change

Permitting increased access to the retail market by single-branch foreign banks will increase competition, as those new competitors seek to expand their market share.

However, the overall impact on the number of branches does not appear to be significant, particularly in view of the limited number of institutions that have stated a desire to expand. Despite this, certain issues should be considered by the HKMA prior to release of the policy. These include:

Ø The costs and benefits of more competition in the retail market and the resulting impact on local banks.

Ø The role of branch networks going forward, particularly in the light of recent innovations in consumer banking such as internet banking, through which business can be conducted without the need for physical branches.

Ø The interest among Mainland Chinese banks in expanding branch networks in Hong Kong.

Ø A number of institutions subject to the one-building condition maintain a separate back-office and/or regional office. Including these offices in the revised branch restrictions (i.e. three branches) would not be appropriate as these offices need to be located in cost-effective sites, which may not be suitable for a front-office location.

The continuing need for restrictions on back and regional offices, following relaxation of the one-building condition, should be reassessed.

1.4 Market entry criteria 1.4.1 Background

Market entry criteria are required to set minimum qualification requirements for access to the banking sector. These qualifications need to reflect the level of access to the market granted to an institution under the licensing structure (i.e. at present, the three- tier system).

The HKMA may only grant an institution authorization if all of the market entry criteria, set out in the Seventh Schedule of the Banking Ordinance, are met.

Some authorization criteria are entry criteria and some are of a continuing nature. The focus of this study, in reviewing the authorization criteria, has been to assess whether the ease and form of market entry for potential market participants is appropriate.

Therefore, we have not reviewed the continuing criteria, as these are in practice intended to be consistent with the Basle Committees’ Minimum Standards for supervision of international banks and the Core Principle for Effective Banking Supervision.

In this context, five types of market entry criteria for authorized institutions have been considered:

Ø minimum size;

Ø minimum capital requirements;

Ø association with Hong Kong;

Ø time period; and

Ø ownership.

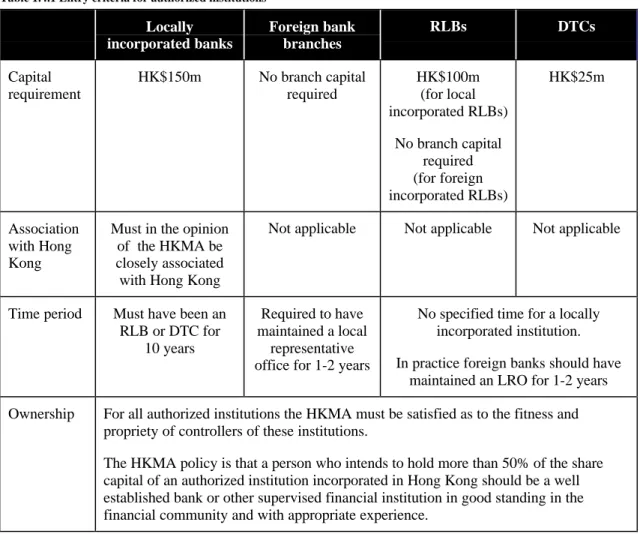

Each of these criteria, as they apply to the different types of authorized institutions, are summarised below (see Table 1.4.1):

Table 1.4.1 Entry criteria for authorized institutions

Locally incorporated banks

Foreign bank branches

RLBs DTCs

Capital requirement

HK$150m No branch capital required

HK$100m (for local incorporated RLBs)

No branch capital required (for foreign incorporated RLBs)

HK$25m

Association with Hong Kong

Must in the opinion of the HKMA be closely associated with Hong Kong

Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable

Time period Must have been an RLB or DTC for

10 years

Required to have maintained a local

representative office for 1-2 years

No specified time for a locally incorporated institution.

In practice foreign banks should have maintained an LRO for 1-2 years Ownership For all authorized institutions the HKMA must be satisfied as to the fitness and

propriety of controllers of these institutions.

The HKMA policy is that a person who intends to hold more than 50% of the share capital of an authorized institution incorporated in Hong Kong should be a well established bank or other supervised financial institution in good standing in the financial community and with appropriate experience.

Source: HKMA

1.4.2 Original policy objectives

The criteria form an important part of the structure of the banking system and are intended to encourage the continued development of Hong Kong as a sound financial centre. The various criteria were introduced from the 1970s onwards and have also been changed periodically, resulting in their current form in 1995 with the introduction of the Seventh Schedule to the Banking Ordinance.

Size criteria

The asset size criterion for foreign banks applying for entry was originally introduced in 1978 and set at total assets of US$3billion. This was increased in stages, the latest being to US$16billion. The minimum asset size criterion was intended to ensure that only substantial and reputable international banks would be admitted as fully licensed banks.

A principal reason behind this was the fact that obtaining a bank licence would allow them access to the small deposit market.

However, in a review of the three-tier system in 1987, it was already recognised that such a policy was inflexible. Accordingly, the HKMA was given the power to override this size criterion if it considers that, in doing so, it would help promote the interest of Hong Kong as an international financial centre. This size criterion has been overridden only twice10 since then.

The asset size (and deposit criteria) for locally incorporated banks were originally introduced in 1981. Minimum total assets were set at HK$2billion for similar reasons to those noted above for foreign banks. These criteria are subject to annual review and have been increased over the years, with the most recent being in 1992, when minimum total assets was increased to HK$4billion and minimum total deposits to HK$3billion.

Minimum capital requirement

Minimum capital requirements have existed since the 1964 Banking Ordinance, but have been changed periodically to their current levels (see Table 1.4.2). These amounts have been changed over time to reflect the change in value of money and also to reflect the changing status of each tier of institution.

Table 1.4.2 Minimum capital requirement for each type of authorized institution

Date Banks RLBs DTCs

1964 $5million - -

1967 $10million - -

1976 $10million - $2.5million

1981 $100million $75million $10million (raised in stages)

1989 $150million $100million $25million

Source: HKMA

The purpose of the above minimum capital amounts is to ensure that an institution has adequate financial resources to support its business at the initial investment stage, when it may be in a loss-making position. A minimum amount of paid-up capital also demonstrates commitment from shareholders due to its permanent nature. In conjunction with the Basle CAR, minimum capital requirements also demonstrate the adequacy of financial resources for the nature and scale of an institution’s business.

Minimum capital applies equally to all institutions, whereas minimum CAR requirements, which are a function of the size and nature of the institutions activities, may be varied at the discretion of the HKMA.

There are no capital requirements for foreign branches (in any tier) operating in Hong Kong because, as branch banks, they are supported by the capital of the whole bank.

Therefore, from a supervisory perspective, the HKMA has limited control over foreign banks’ capital adequacy compliance, although all foreign incorporated authorized institutions are required to meet a minimum ratio of 8% in their country of

10 Bank of New Zealand in 1987 and Bank of Ireland in 1988, although both have now revoked their licences.

incorporation. If their CAR fell below 8%, the HKMA would have the power to revoke their authorization in Hong Kong.

Minimum time period and association with Hong Kong criteria

These criteria originated in 1981 after the moratorium on banking licences was lifted.

The principal objective was to ensure that:

“locally incorporated applicants should reflect predominantly Hong Kong interests and to prevent any foreign bank which could not obtain a licence for a branch because it did not satisfy the criteria from obtaining a licence through a subsidiary”.

This objective was originally set out in the form of requirements that:

Ø a local bank must be predominately beneficially owned by Hong Kong interests (the Hong Kong ownership criterion);

Ø the applicant must have been in the business of taking deposits from and granting credit to the public in Hong Kong for at least ten years; and

Ø registered under the Deposit-taking Companies Ordinance.

The beneficial ownership criterion was expanded in 1992 to include institutions that are also, in the opinion of the Governor in Council, otherwise closely associated and identified with Hong Kong. In the Commissioner of Banking’s Annual Report for 1992, it was stated that:

“In assessing whether an institution meets this criterion, the Governor in Council will take into account such factors as the institution’s history, whether it has a separate identity whose mind and management is based in Hong Kong, the location of the institution’s business and the proportion of the institution’s shareholders which are based in Hong Kong.”

This change reflected the increasing difficulty of interpreting what constitutes “Hong Kong ownership”.

It follows from the criteria that, in practice, a foreign bank cannot set up a new subsidiary with a full bank licence in Hong Kong11. This is because a locally incorporated bank must have been a DTC or RLB for not less than ten continuous years before it is eligible to apply for a full banking licence. This is evidenced by the fact that, in the period since 1981, only three new locally incorporated banking licences have been granted12 and all applicants had a long period of association (well in excess of ten years) with Hong Kong.

11 See HKMA Guide to Applicants for authorization under the Banking Ordinance.

12 Wardley Limited 1993 (renamed HSBC Investment Bank Asia Limited), Jardine Fleming Bank 1993 and Sun Hung Kai Bank 1982 (renamed International Bank of Asia).

It should be also noted that foreign banks (or other regulated financial institutions) are able to apply for RLB or DTC status if they do not meet the entry criteria for a foreign bank branch. Entry as a RLB is not as restricted (e.g. no minimum asset requirement) and foreign institutions have the choice of either local incorporation or branch status.

On the other hand, all DTCs (with the exception of two Japanese DTCs) are locally incorporated and, in practice, only locally incorporated companies are granted DTC licences.

Ownership

It is generally the HKMA’s policy that a person who intends to hold more than 50% of the share capital of an authorized institution incorporated in Hong Kong should be a well established bank or other supervised financial institution. This criterion was implemented in 1981, following a rapid increase in the number of DTCs (40 new DTCs in the first quarter of 1981) and was intended to ensure that only a fit and proper person may own an institution that takes deposits from the public.

The policy helped ensure that majority ownership of authorized institutions will be confined to financial institutions which are subject to consolidated supervision and which have a lender of last resort behind them. In practice, the policy has been strictly enforced only in the case of RLBs and DTCs and there are a number of cases where existing licensed banks in Hong Kong have been acquired by non-banks.

1.4.3 Assessment of the market entry criteria Size criteria

Foreign bank branches

The minimum asset size criterion is important because it acts as a proxy for the quality of the entrant. A bank of this size should, in practice, have the management and systems to be able to control overseas operations. It should be noted that the assets size of US$16billion allows access by the world’s 333 largest banks13, of which 105 are represented in Hong Kong. However, asset size is not always a good indicator of asset quality and prudence of bank management, which ultimately affects the banks’ safety and soundness.

The asset size criteria also restrict certain niche market banks, with assets of below the US$16billion minimum, from obtaining a full bank licence. However, the HKMA has the power to relax this requirement if it considers it appropriate to do so to promote the interests of Hong Kong as an international financial centre. These banks can also enter the Hong Kong market in the form of an RLB, for which authorization is not subject to the size criteria.

13 Source: Bankers, July 1997

Locally incorporated banks

The difference between the minimum asset size criteria for local banks (HK$4billion) and foreign banks (US$16billion) is significant. However, in general, domestic banks are smaller than international banks and are under the direct home supervision of the HKMA. Therefore, it would not be appropriate to set the same assets size criterion for both foreign and local institutions. It should also be noted that there is a minimum deposit criterion of HK$3billion for local banks.

The size criteria for locally incorporated banks provide transparent targets for RLBs and DTCs to meet in order to upgrade to a full bank licence. Similar to the size criterion for foreign banks, the size of a deposit base and assets demonstrate a reasonable degree of management experience and systems in place to compete in the domestic market.

Minimum capital requirements

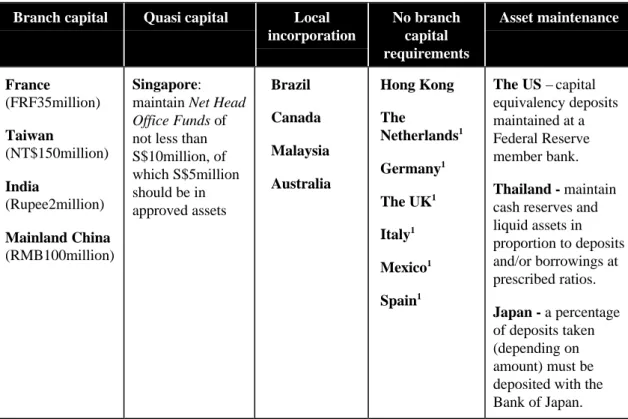

Foreign branches

The fact that foreign branch banks have so much access to the local banking market has raised some concerns in that they do not presently need to keep any minimum capital in Hong Kong. Local banks, in particular, see this as being an unfair competitive advantage and consider that foreign banks should have the same capital requirements as local banks. One specific view expressed by bankers in this respect was that the specific CAR requirement set by the HKMA, which is in excess of the Basle 8%

minimum, is higher than the requirement on foreign banks set by their home supervisor.

When a form of branch capital is required, this can, broadly speaking, be divided into the following two main types:

Ø Branch capital – a set minimum capital requirement for a foreign branch bank, which may (or may not) be similar to the minimum capital requirements for a locally incorporated bank.

Ø Quasi branch capital – maintaining a set minimum amount of head office funds (e.g. long-term loans from the parent bank), which is in effect capital, although it may not be represented in the balance sheet as such (e.g. represented as long-term intra-group borrowings).

The principal reasons for branch capital or quasi capital requirements include:

Ø It demonstrates commitment by the parent bank – similar to minimum capital requirements for locally incorporated institutions, a certain level of capital investment from the parent bank represents a level of commitment to the local banking sector.

Ø Capital investment – certain countries seeking long-term foreign capital investments use this as a means of achieving economic objectives (e.g. maintenance of a capital account surplus).

Ø Depositor protection – requiring a capital cushion or certain holding of assets is a method of ensuring that in the event of liquidation, sufficient funds would be available to effect repayment to depositors.

The level playing field issue is also quoted as a reason to require branch capital.

However, this is more appropriately viewed in the context of capital adequacy regimes, rather than a minimum capital requirement. All authorized institutions operating in Hong Kong are subject to a similar capital adequacy regime. For example, locally incorporated institutions have set minimum ratios, while foreign banks applying for entry must, in general, meet (on a continuing basis) a minimum capital adequacy ratio of 8% (calculated in a way which is consistent with the Basle Capital Accord) at the parent bank level. However, foreign branch banks have more flexibility in that they can leverage off their parent bank’s capital, which is likely to be larger than most local banks, and therefore can aggressively expand (or contract) their balance sheets in Hong Kong. The imposition of branch capital does not resolve this issue, as foreign branch banks would also need to be subject to minimum capital and local capital adequacy ratios. Imposing such a requirement is likely to detract from Hong Kong’s position as an international financial centre.

In view of the fact that the investment cost of opening a branch in Hong Kong already represents a strong degree of commitment from the parent bank, there is no apparent need to require branch capital to further demonstrate this commitment. In fact, requiring capital may work against the objectives of attracting a broad range of foreign participants to Hong Kong, especially in the light of the current economic circumstances surrounding a number of Asian countries which have reduced the attractiveness of the region as a whole.

Hong Kong permits a free flow of capital and, therefore, imposing a branch capital requirement could be seen to be some form of capital control. This was a point that was commented upon by several foreign banks.

One of the more important issues in Hong Kong is the case for improved depositor protection in case a bank fails. Requiring some form of branch capital may appear as one way of dealing with this issue in relation to a foreign branch bank. However, this needs to be viewed in terms of the liquidation process applicable in Hong Kong (for details see Section 1.6).

Under the liquidation framework in Hong Kong, requiring some form of branch capital would be less effective at improving depositor protection than, for example, an asset maintenance requirement14. In a liquidation, the surplus assets of the branch (i.e. after deducting priority claims) would be applied equally for the benefit of all creditors world-wide. Therefore, increasing the potential amount of surplus assets, by imposing a branch capital requirement, may benefit priority claims depositors but not others. In addition, the liquidator would only have jurisdiction over Hong Kong-based assets of the branch. However, the potential increase in surplus assets that branch capital may

14 Asset maintenance – a requirement to maintain a certain amount of specified assets (usually in Government bonds or other liquid assets) either deposited at the central bank or in a commercial bank. The amount of assets required to be maintained is generally set in relation to the deposit taking activity of the branch (e.g. 5% of total third party liabilities).

provide is affected by the amount of assets in Hong Kong. An asset maintenance requirement would be a more direct way of dealing with this issue (i.e. to try to ensure that there are sufficient surplus assets in Hong Kong to pay-off priority claims depositors in a liquidation of a branch bank).

Based on the above, there is no strong case for requiring foreign branches to maintain capital in Hong Kong. However, the issue of asset maintenance would warrant further consideration from the point of view of depositor protection (see Section 1.6).

Locally incorporated institutions

The minimum capital requirements for local banks were last increased in 198915, partly to take account of the change in the value of money since 1981 and, for RLBs, to reflect the additional status and privileges granted to them when they replaced the then second tier of licensed DTCs. The effective inflation since 1989 has been 95%. The effectiveness of the level of minimum capital in ensuring that new entrants have sufficient financial backing has therefore been substantially diminished.

At present, the average ratio of shareholders’ funds to assets, for locally incorporated banks, is around 8.71%16. For a newly incorporated bank meeting the minimum capital (HK$150million) and minimum assets (HK$4billion) requirements, this ratio would be 3.75%. In practice, the minimum capital requirement therefore appears low in comparison to the minimum assets criteria.

Associated with Hong Kong and time period criteria

In granting an authorization for a locally incorporated bank, the HKMA will take into account factors such as the historical association of the institution with Hong Kong. A foreign bank entering Hong Kong would not, in practice, be able to set up a local bank subsidiary immediately as they need to have operated as an RLB or DTC for at least ten years. However, a foreign bank may either wholly acquire or partially invest in an existing locally incorporated bank, with the approval of the HKMA. In fact, this has occurred a number of times since 197817.

Since the association with Hong Kong and time period criteria were introduced, a significant number of foreign banks have entered the market and there is little evidence that restricting them to branch status only has deterred new market entrants. A principal reason for this is that foreign branch banks do not have to hold any capital in Hong Kong, which provides them with greater flexibility. This is evidenced by the fact that there are certain foreign branch banks (with multi-branch licences) which, due to their long involvement with Hong Kong may meet the criteria for local incorporation but have not approached the HKMA to do so18. For example, Standard Chartered Bank has been present in Hong Kong well in excess of ten years and remains a foreign branch

15 Source: Annual Report 1989 – Commissioner of Banking

16 Source: KPMG Banking Survey Report 1997-98

17 For example, Wells Fargo invested in Shanghai Commercial Bank, Abbey National and Hambros invested in D.A.H. Private Bank, Guoco Group purchased Dao Heng Bank and Overseas Trust Bank and Arab Banking Corporation purchased International Bank of Asia.

18 There is currently no provision in the Ordinance to allow a foreign branch bank to convert to a locally incorporated bank and this would need to be addressed if there was pressure from foreign banks that would otherwise qualify.