Huang & Chen

Attitudes toward Inclusive Education: A

Comparison of General and Special Education

Teachers in Taiwan

Chiu-Hsia Huang

aand Roy K. Chen

b aDepartment of Special Education, National PingTung University, Taiwan

b

School of Rehabilitation Services and Counseling, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, USA

(Received 01 November 2016, Final revised version received 16 June 2017)

The purpose of this study was to examine the attitudes of general and special education teachers toward inclusive education of students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities. A total of 539 participants were recruited from teachers’ colleges and public schools in three prefectures of central and southern Taiwan. The Attitudes toward Students with Chronic Illnesses and Disabilities Vignettes were used to assess the participants’ levels of acceptance of eight hypothetical students with various health issues and disabilities. Descriptive and inferential statistics, including measure of central tendency, t-test, and multivariate analysis of variance, were used to interpret the data set. Results indicate that both the types of teacher education programs and the teaching experience influence the willingness of the participants to include a student with special needs in the regular classroom setting.

Keywords: Inclusive education, attitudes, Taiwan, chronic illness, disability

Introduction

According to the Ministry of Education of Taiwan (2011), in the 2010 academic year 106,702 students with disabilities and chronic illnesses enrolled at elementary and secondary schools, accounting for 2.37% of the total national student population. Intellectual disability and learning disability made up the two largest disability groups at 27% and 20%, respectively (Taiwan Ministry of Education, 2011). Taiwanese special education teachers, approximately 14,000 in numbers, face a rather high teacher-to-student ratio when delivering quality education in the public school system (Taiwan Ministry of Education, 2016). Therefore, some students with disabilities and

AJIE

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education Vol. 5, No. 1, July 2017, 23-37Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 24

chronic illnesses fall through the cracks of the complex institutional structure. High absenteeism and drop-out rates among school-age students in recent years have become a cause of concern for educators in Taiwan. Health and disability related reasons account for 23.3% and 14.9% of the reported absences in elementary- and secondary-level students, respectively (Taiwan Ministry of Education, 2011). Many of these students with medical conditions not only have physical, sensory, and cognitive disabilities but also exhibit behavioral and emotional impairments. Prior to the mid-1980s, the social climate and educational environment in Taiwan were not conducive for youths with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities to succeed academically (Chang, 2007). The lack of legal protection of educational rights, inaccessible infrastructure, unreliable public transportation system, low expectations from society and teachers’ negative attitudes preclude this population from receiving sound education like their peers without disabilities.

Modeled after the United States Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 1997, Taiwan’s legislation body passed several bills, including the Special Education Acts of 1984 and 2002 and the Provision for Special Education Acts of 1987 and 2003, to level the playing field for students with disabilities and chronic illnesses. These laws stipulate that students with health impairments and disabilities shall have equal access to and receive free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive settings (Taiwan Ministry of Education, 2011). Under these new regulations schools may not discriminate against students who have chronic illnesses and/or disabilities.

exhibited noticeably more reservations toward severe disabilities, such as emotional impairments and mental retardation. The reported order of preference was physical disabilities, learning disabilities, visual impairments, hearing impairments, behavioral difficulties, and mental retardation (Alghazo & Gaad, 2004).

The special education literature is replete with empirical evidences to support that special education teachers are more confident and prepared to integrate students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities in inclusive education settings than general education teachers. Buell and her colleagues (1999) utilized a multivariate analysis of variance technique to test for differences in responses between 202 general and 87 special education teachers on questions measuring beliefs about inclusion. Findings revealed that the former group expressed greater training needs in working with students with disabilities than did the latter group. In a recent study of 1,623 Bangladeshi pre-service teachers, Ahsan, Sharma, and Deppeler (2012) concurred with past reports of such perceived needs. They found that the type of teacher education preparation program was a strong predictor in the teaching self-efficacy when it comes to adopting inclusive education. Pre-service teachers who enrolled in the special education track were more comfortable with teaching students with disabilities than their counterparts who enrolled in the general education track. Teachers’ negative perceptions of students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities are sometimes attributable to lack of understanding of the conditions.

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 26

Interestingly, the type of chronic illness and disability also influence teachers’ beliefs on the learning potential of their students. In a survey of 168 American physical education teachers, Obrusnikova (2008) found that the participants were more positive about teaching students with learning disabilities and were less positive about teaching students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Ahsan, Sharma, and Deppeler (2012) found Bangladeshi teachers were most receptive of inclusive education for students with attention problems and least receptive of sensory impairments in which students require communication assistive technologies such as sign language interpretation and braille. Moreover, their multiple regression model also confirmed that age and prior contact with people with disabilities were strong predictors of the participants’ willingness to implement inclusive education. Furthermore, older teachers were less concerned about teaching students with special needs. Prior contact seemed a vital factor. Those who had significant interaction with people with disabilities had less concerns than those who did not have prior interaction. The impact of professional development on teachers’ attitudes is encouraging. In an experimental study conducted by Avramidis and Kalyva (2007), they randomly assigned 155 Greek general education teachers to a control group and an experimental group. The results showed that teachers who had been actively involved in learning how to teach students with disabilities held significantly more positive attitudes toward inclusive education than their counterparts without such training. Using the interview methodology, Scott, Jellison, Chappell, and Standridge (2007) examined the views of 43 music teachers on inclusive education. They concluded that positive attitudes toward students with disabilities are predicated on the teachers’ perceived professional competencies and access to support and resources.

role, at the meso level, in influencing societal expectations of interactions between people with disabilities and those without disabilities. Prior contact with people with disabilities, whether pleasant or unpleasant, could impact the willingness of those without disabilities to accept their full integration and inclusion in society (Martin et al., 2008). It should come as no surprise that some teachers might have acquired preconceived notions about students with disabilities, as they have already been exposed to disability-related issues on the aforementioned levels.

The purpose of this study was to examine the attitudes of teachers toward students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities. The specific research questions are as follows: (1) Are there differences in the acceptance of students

with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities between general and special education teachers? (2) Are there differences in the acceptance of students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities between pre-service, novice, and experienced teachers? and (3) Does prior personal contact with a disabled child before entering the teaching profession affect the level of a teacher’s acceptance of students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities?

Method Participants

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 28

69.6%) had no prior personal contact with disabled children before entering the teaching profession, while 30.4% (n = 164) of them reported previous contact before.

Instrumentation

The Attitudes toward Students with Chronic Illnesses and Disabilities Vignettes. Based on extensive literature review, the authors developed an

instrument, ASCDV, to measure the attitudes toward students with chronic illnesses and disabilities. A panel composed of five experts, including three special education professors and two pediatricians, read and provided feedback on the instrument. The ASCDV consists of a series of eight hypothetical vignettes, each depicting a fictitious student with one of the chronic illnesses and/or disabilities: asthma, mobility disability, diabetes mellitus, leukemia, epilepsy, hepatitis, sensory impairments, and HIV/AIDS. Each vignette contained scripted personal information about the fictitious student, such as name, sex, performance at school, type of chronic illness and/or disability, and grade level. All the fictitious students in the eight vignettes were referred to as having average intelligence and exhibiting behaviors appropriate for their age group.

To assess the levels of acceptance of chronic illnesses and/or disabilities, each participant was asked to choose one statement that best describes his or her willingness to include the fictitious student in the class on a 5-point Likert-type scale, 1 = I would welcome this student in my classroom, 2 = I have no major concerns having this student in my classroom, 3 = I have some minor concerns having this student in my classroom, 4 = I have serious concerns having this student in my classroom, and 5 = I would request to have this student removed from my classroom. Reversed scoring on the eight vignettes was used to compute the participant’s attitudes. The total possible scores ranged from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating more comfort with integrating students with special needs. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this study was .815.

Design

chronic pathologies described in the vignettes: asthma, mobility disability, diabetes mellitus, leukemia, epilepsy, hepatitis, sensory impairments, and HIV/AIDS. Types of teacher preparation include special education and general education. Levels of teaching experience included pre-service (students enrolled in teacher preparation programs), novice (teachers with less than five years of teaching experience), and experienced (teachers with five or more years of teaching experience).

Procedure

A pilot test was conducted on a group of 13 graduate special education students in order to fine-tune the questionnaire before the full-scale survey. After obtaining approval from the institutional review board, the research team contacted college deans and public school principals in three prefectures in central and southern Taiwan, requesting for their participation in the study. Informed consent was explained to the participants before administering the survey. Neither extra credit nor other incentives were given. The time needed to complete each questionnaire was between 10 to 15 minutes.

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive and inferential analyses were done using SPSS 20. For the present study, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was chosen over repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA). According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2012), MANOVA reduces the possibility of spurious rejection of null hypothesis (Type I error), which tends to increase if separate ANOVA tests are performed for each of the independent measures. Furthermore, Wilks’ Likelihood Ratio was reported, since MANOVA indicated significant effects on two of the independent measures (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2012; Warner, 2013). The probability level for rejection of all null hypotheses was set at .05 unless otherwise indicated.

Findings

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 30

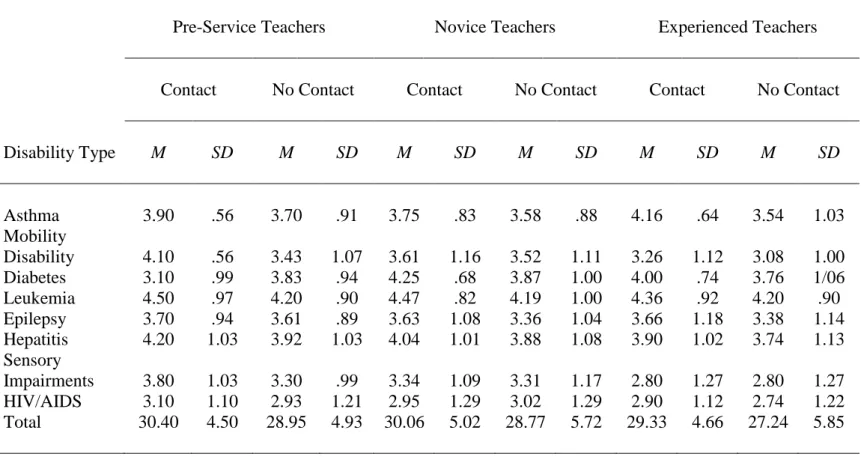

Table 1. Attitudes of General Education Teachers toward Students with Chronic Illnesses and/or Disabilities

Pre-Service Teachers Novice Teachers Experienced Teachers

Contact No Contact Contact No Contact Contact No Contact

Table 2. Attitudes of Special Education Teachers toward Students with Chronic Illnesses and/or Disabilities

Disability Type Pre-Service Teachers Novice Teachers Experienced Teachers

Contact No Contact Contact No Contact Contact No Contact

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 32

The MANOVA comparing types of teacher preparation, levels of teaching experience and prior personal contact yielded results that approached a significant interaction for type, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.973, F(8, 519) = 1.826, p = .06. The condition of least acceptance of all levels of special educators was HIV/AIDS (m = 2.92), for general educators was as well HIV/AIDS (m = 2.94). Leukemia received greatest acceptance by general educators with an average of m = 4.32, by special educators with an average of m = 4.13. Both types of educators indicated similar levels of acceptance for sensory impairments, asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, and mobility disability. Types of teacher preparation have a significant difference on the levels of teacher acceptance toward children with asthma (p < .045) and leukemia (p < .011).

The MANOVA yielded a significant effect for the independent variable of experience, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.907, F(16, 1038), p < .0001. Univariate analysis of conditions across levels of experience indicated that three of the eight conditions were found significant. The three significant conditions were leukemia (p < .005), mobility disability (p < .003), and sensory impairments (p < .0001). No main effect was found for the variable of prior personal contact, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.970, F(8, 519) = 1.50, p = .154. Furthermore, there was no interaction noted between type of teacher preparation and experience, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.954, F(16, 1038) = 1.537, p = .08; between type of teacher preparation and contact, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.986, F(8, 519) =.0951, p = .474; between level of experience and contact, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.952, F(16, 1038) = 1.631, p = .06; or among type of teacher preparation, level of experience and contact, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.977, F(16, 1038) = 0.746, p = .747. In summary, the rank order of Taiwanese teachers’ acceptance of students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities is as follows: (1) leukemia, (2) hepatitis, (3) diabetes, (4) asthma, (5) mobility disability, (6) epilepsy, (7) sensory impairments, and (8) HIV/ADIS.

Discussion

hepatitis, diabetes, epilepsy, and particularly HIV/AIDS (Heward & Orlansky, 1992: Sullivan, 1994). It appears that types of teacher preparation and levels of teaching experience had impacts on teacher attitudes toward students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities in Taiwan (Chong, Forlin, & Au, 2007). Furthermore, the findings also support the notion that there is a significant difference between a pre-service, a novice and an experienced teacher’s attitudes toward students with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities (Ahsan, Sharma, & Deppeler, 2012; Sharma, Moore, & Sonawane, 2009). Confidence in teaching efficacy takes time to develop. As young teachers are exposed to new classroom management skills and knowledge about medical aspects of disability via continuing education activities such as workshops, conferences and seminars, they become less concerned about integrating students with special needs with their nondisabled classmates.

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 34

The framework of disability is situational and researchers must understand that the public perception of an individual with a disability is influenced by four elements: (1) the environmental system, (2) the personal system, (3) mediating factors, and (4) health status and health-related behavior (Dell Orto & Power, 2007; Vash & Crewe, 2003). For example, a student with such a visible disability as Down syndrome may be seen as less capable, and may have more difficulty shielding himself or herself from judgmental scrutiny on the part of both teachers and school administrators, than a student with a learning disability that may very well not be discernible upon first impression. Teachers and rehabilitation professionals who serve on an individualized education plan team are humans, with their own emotions and personal biases; therefore, it may be not unusual for them to feel inclined to hold lower expectations of students with certain types of disabilities, based on their stereotypical views and limited previous contact (Smart, 2016). This line of thinking supports the findings of the present study, namely that there is a preferred order of disability types among teachers, regardless of their experience.

The generalizability of the findings is limited by some methodological issues. First, the unbalanced sample distribution of general education teachers was evidenced by too many novice teachers and too few experienced teachers. Second, there is always a difficulty in cross-cultural translation of the meanings of medical terminologies precisely from English to Mandarin, due to differences in the cultural interpretations and perceptions of illness and disability. Moreover, many measurement procedures may be interpreted differently based on a person’s educational background and view of world. Fourth, the prior personal contact experience variable was vaguely operationalized. It is unfeasible to gauge accurately the intensity and frequency of interacting with a person with a disability based on the dichotomous responses of yes or no.

improving the teaching efficacy through the development of teachers’ assertiveness and confidence about their skills in implementing inclusion programs, (4) emphasizing the moral responsibility of college faculty members to nurture positive attitudes toward exceptional children, and (5) recognizing cultural values, religious beliefs, and racial difference shape the attitudes among various ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

References

Ahsan, M. T., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. M. (2012). Exploring pre-service teachers’ perceived teaching-efficacy, attitudes and concerns about inclusive education in Bangladesh. International Journal of Whole

Schooling, 8(2), 1-20.

Alghazo, E. M., & Gaad, E. E. N. (2004). General education teachers in the United Arab Emirates and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 31(2), 94-99. doi: 10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x

American Lung Association (2007). Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, Research and Program Services. Trends in asthma morbidity and

mortality. Retrieved from

http://www.lungusa.org/atf/cf/%7B7A8D42C2-FCCA-4604-8ADE-7F5D5E762256%7D/ASTHMA06FINAL.PDF

Avramidis, E., & Kalyva, E. (2007). The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(4), 367-389. doi: 10.1080/08856250701649989

Buell, M. J., Hallam, R., Gamel-McCormick, M., & Scheer, S. (1999). A survey of general and special education teachers’ perceptions and inservice needs concerning inclusion. International Journal of

Disability, Development and Education, 46(2), 143-156. doi:

10.1080/103491299100597

Chang, H. H. (2007). Social change and the disability rights movement in Taiwan 1981-2002. Review of Disability Studies, 3(1&2), 3-18.

Asian Journal of Inclusive Education (AJIE) 36

Cook, B. G., Cameron, D. L., & Tankersley, M. (2007). Inclusive teachers’ attitudinal ratings of their students with disabilities. Journal of Special

Education, 40(4), 230-238. doi: 10.1177/00224669070400040401

Dell Orto, A. E., & Power, P. W. (2007). The psychological and social impact

of illness and disability (5th ed.). NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Dupoux, E., Wolman, C., & Estrada, E. (2005). Teachers’ attitudes toward integration of students with disabilities in Haiti and the United States.

International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 52(1),

43-58. doi: 10.1080/10349120500071894

Forlin, C., Loreman, T., Sharma, U., & Earle, C. (2009). Demographic differences in changing pre-service teachers’ attitudes, sentiments and concerns about inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive

Education, 13(2), 195-209. doi: 10.1080/13603110701365356

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Heward, W. L., & Orlansky, M. D. (1992). Exceptional children (4th. ed). New York: MacMillan Publishing Company.

Hsieh, L. P., & Chiou, H. M. (2001). Comparison of epilepsy and asthma perception among preschool teachers in Taiwan. Epilesia, 42(5), 647-650.

Johnstone, C. (2005). Who is disabled? Why is not? Teachers perception of disability in Lesotho. Review of Disability Studies, 1(3), 13-21.

Leary, M. R. (2012). Introduction to behavioral research methods (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn & Bacon.

Loreman, T., Forlin, C., & Sharma, U. (2007). An international comparison of pre-service teacher attitudes towards inclusive education. Disability

Studies Quarterly, 27(4). Retrieved from

http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/53

Martin, J. K., Lang, A., & Olafsdottir, S. (2008). Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A framework integrating normative influences on stigma (FINIS). Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 431-440. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.018

Obrusnikova, I. (2008). Physical educators’ beliefs about teaching children with disabilities. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106(2), 637-644. doi: 10.2466/PMS.106.2.637-644

Scott, L. P., Jellison, J. A., Chappell, E. W., & Standridge, A. A. (2007). Talking with music teachers about inclusion: Perceptions, opinions and experiences. Journal of Music Therapy, 44(1), 38-56. doi: 10.1093/jmt/44.1.38

Sharma, U., Moore, D., & Sonawane, S. (2009). Attitudes and concerns of pre-service teachers regarding inclusion of students with disabilities into regular schools in Pune, India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher

Education, 37(3), 319-331.

Shiu, S. (2001). Issues in the education of students with chronic illness.

International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 48(3),

269-281. doi: 10.1080/10349120120073412

Smart, J. (2016). Disability, society, and the individual (3rd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Sullivan, K. W. (1994). Teacher acceptance of children with chronic illness. Unpublished master thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Taiwan Ministry of Education (2011). Education in Taiwan. Retrieved from

http://ws.moe.edu.tw/001/Upload/1/relfile/7015/13932/319d25bb-31d4-4e8b-a38d-80cc45de75ec.pdf

Taiwan Ministry of Education (2016). Key education statistics. Retrieved from

http://english.moe.gov.tw/lp.asp?ctNode=11432&CtUnit=1348&BaseD

SD=16&mp=1

Vash, C. L., & Crewe, N. M. (2003). Psychology of disability (2nd ed.). NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Warner, R. M. (2013). Applied statistics: From bivariate through multivariate

techniques (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Yach, D., Kellogg, M., & Voute, J. (2005). Chronic diseases: An increasing challenge in developing countries. Transactions of the Royal Society of