行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

從組織結構、組織文化及組織創新之動態觀點探討「併購

消化不良」之紓解—以台灣資訊電子產業為例(第 2 年)

研究成果報告(完整版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 96-2416-H-151-006-SS2 執 行 期 間 : 97 年 08 月 01 日至 98 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立高雄應用科技大學國際企業系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 林亮宏 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 98 年 10 月 05 日

行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 研究成果報告

從組織結構、組織文化及組織創新之動態觀點探討「併購

消化不良」之紓解—以台灣資訊電子產業為例(第 2 年)

研究成果報告(完整版)

計畫類別: 個別型 計畫編號: NSC 96-2416-H-151-006-SS2 執行期間: 97 年08 月01 日至98 年07 月31 日 執行單位: 國立高雄應用科技大學國際企業系 計畫主持人: 林亮宏 計畫參與人員: 專任助理人員:鄧雅丰 兼任助理人員:許明珠 兼任助理人員:江彥慶 兼任助理人員:陳菁月 公開資訊: 研究成果報告不提供公開查詢中 華 民 國 98 年 06 月30 日

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫 █成果報告

□

期中進度報告

從組織結構、組織文化及組織創新之動態觀點探討「併購消化不

良」之紓解—以台灣資訊電子產業為例

計畫類別:█ 個別型計畫□ 整合型計畫 計畫編號:NSC96-2416-H-151-006-SS2 執行期間:2007 年 8 月1 日至2009 年 7 月31 日 計畫主持人:林亮宏國立高雄應用科技大學國際企業系 計畫參與人員:專任助理人員:鄧雅丰 兼任助理人員:許明珠 兼任助理人員:江彥慶 兼任助理人員:陳菁月 成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):□精簡報告■完整報告 本成果報告包括以下應繳交之附件: □赴國外出差或研習心得報告一份 □赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告一份 □出席國際學術會議心得報告及發表之論文各一份 □國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告書一份 處理方式:除產學合作研究計畫、提升產業技術及人才培育研究計畫、 列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢 □涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢 執行單位:國立高雄應用科技大學國際企業系 中 華 民 國 98 年 06 月 30 日行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫研究成果報告

Relaxing mergers and acquisitions indigestion for the Taiwanese

information and electronics firms: The dynamics of organizational

structure, culture, and innovation

計畫編號:

NSC96-2416-H-151-006-SS2

執行期限:96/08/01 ~ 98/07/31

主持人:林亮宏 國立高雄應用科技大學國際企業系

計畫參與人員:專任助理人員:鄧雅丰 兼任助理人員:許明珠 兼任助理人員:江彥慶 兼任助理人員:陳菁月Abstract

Corporate-level strategy involves searches for new domains in which to exploit and defend organizational ability to create value from the use of its core competences. Mergers and acquisitions (M&As), which consists of vertical expansion, horizontal expansion, and unrelated diversification, seems to be a useful corporate-level strategy in the recent decades. Firms implement M&As usually owing to the reported benefits of reducing costs, adding product value, avoiding price wars, increasing bargaining power, and enhance organizational innovativeness. As to the M&A –performance relationship, there exists different result in the real-world practice. And in the academic researches, while some studies suggested that M&As lead to outstanding financial and technological performance, others suggested the opposite. There are several possible reasons for pessimistic M&A performance. First, acquisitions usually entail high transaction costs that result in acquirers not realizing profits from acquisitions. Another negative effect is that the acquisition processes usually absorb much managerial time and energy. In the past M&A cases, “M&A indigestion”often occurs when increasingly keen competition pushes firms to expand at ever faster rates. Having engaged in a mass of M&A activities, firms must find solutions of the problems if they want to effectively undertake more M&As.

Theories of organizational and strategic management suggest two perspectives to solve the difficulty of M&A performance: the “speed trap” debate and the “congruence model of organizational design”. The former reveals that although fast decision making initially helped organizations achieve their desired growth, they often trigger large financial outlays. The resulting speed-up exhaustion of firm

resources in turn accelerates managerial decision making process. Such actions move in cycles, and induce a “speed trap”when managers felt increasingly pressure for actions. This theory implies that organizations may have an “optimal pace”of change, restructuring, and M&As. On the other hand, “congruence”refers to “the degree to which the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and structures of one component are consistent with those of the others”. An extensive body of research suggests that “an organization’s ability to achieve its goal is a function of the congruence between various components”. Thus, extending the study period of time, and integrating strategic, organizational, and environmental perspectives in M&A studies are necessary.

For verifying the inconsistent M&A strategy–performance relationship, this study argues that different M&A strategies are related to different economic benefits. Achieving these different benefits, distinctly different acculturative mode and organizational structure are required in the strategic implementation. Superior post-acquisition performance is not the consequence of M&A strategy per se, but of the appropriate acculturative and structural fits. An empirical investigation of 114 large electronic and information firms reveals that firms pursuing related M&As can realize benefits from economics of scope, and these benefits can be achieved from the cooperation between divisions. A centralized multidivisional structure and the assimilation mode of acculturation are required in related M&As. Conversely, firms pursuing unrelated M&As can realize benefits from efficient internal governance mechanisms, and these benefits can be achieved from the competition between divisions. A decentralized multidivisional structure and the separation mode of acculturation are required in unrelated M&As.

1. Introduction

Corporate-level strategy involves searches for new domains in which to exploit and defend organizational ability to create value from the use of its core competences (Porter, 1987; Jones, 2004). Mergers and acquisitions (M&As), which consists of vertical expansion, horizontal expansion, and unrelated diversification, seems to be a useful corporate-level strategy in the recent decades (Kirchmaier, 2003; Hill, Jones, & Gavin, 2004; Dorf & Byers, 2005). In most industries, such as automotive, pharmaceutical, and computer industries, numerous M&As have increased the degree of industrial consolidation. International firms implement M&As usually owing to the reported benefits of reducing costs, adding product value, avoiding price wars, increasing bargaining power, and enhance organizational innovativeness (Burgelman, Christensen, & Wheelright, 2004; Schilling, 2005; Prajogo & Sohal, 2006). Firms make M&As also because those acquired firms have uncommon strategic assets, such

as customer and supplier relationships, distribution systems, and technological know-how. The acquirers believe they can increase the efficiency and reduce the production cost of the target firms by transfer technology and management skills. Over the last decade, we have discerned unprecedented growth in global M&A transactions. The total value of M&As increased from $ 1 trillion in 1995 to over $ 5 trillion in the year 2000 (de Man & Duysters, 2005). UN estimates also reported that 40 to 80 percent of worldwide foreign direct investment (FDI) was in the form of M&As between 1998 and 2003. In Taiwan, firms are in the middle of a merger wave. Before 2003, only less than annual 100 M&A cases in open market and OTC were reported by Department of Economic, however, in 2004 and 2005 the reported M&As have increased to over 200 cases per year (open market and OTC). To deserve to be mentioned, over 25% of these Taiwanese M&As were undertaken in the information related industries. The major objectives for M&As in the information and electronic industry include reducing cost, entering new markets, and the acquisition of new technologies (Chen & Chen, 2003; de Man & Duysters, 2005).

Concurrent with heavy M&A activities, firms’technological development and organizational innovation has become increasingly important as a way to generate new ideas in organizations. The technological changes and keen global competition have increased the importance of organizational innovation because it can help firms to achieve and maintain competitive advantages. Moreover, organizational innovation has become crucial for value creation in many sectors (Hitt, Keats, Harback, & Nixon, 1994). Unfortunately, M&A strategies often have different influences on firms’ innovative capabilities in real world practices (de Man & Duysters, 2005). While some studies suggested that M&As lead to outstanding organizational innovativeness (Larsson, Bengtsson, Henriksson, & Sparks, 1998; Bresman, Birkinshaw, & Nobel, 1999), others suggested the opposite (Morgan, 2001; Jones, 2005). Besides innovation performance, however, even a curious glance at the literature pertaining to firms in different countries and industries, in which analysts reveal the negative financial performance implications of M&A growth –a phenomenon often referred to as “M&A indigestion”that occurs when increasingly keen competition pushes firms to expand at ever faster rates (Bowman & Singh, 1993; Barkema, Baum, & Mannix, 2002).

2. Theoretical Background

M&A indigestion refers to the organizational difficulties occurred when attempting to integrate many mergers and acquisitions in a short period of time (Schijven, 2005). Extending the study period of time is important in M&A studies, moreover, to integrate strategic, organizational, and environmental perspectives is also necessary.

As to the inconsistency on the M&A-performance relationship, one important point is that any single acquisition for large firms is merely a small part of a longitudinal sequence of acquisitions. Thus, integration mechanism must play a crucial role in the M&A process. However, at least in the short term, the integration of M&As are unavoidable imperfect, as a result, M&A performance often tend to be worse than expected for at least some time (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Schijven, 2005). First of all, acquisitions usually entail high transaction costs (e.g., negotiating cost, bidding cost, and monitoring cost) that result in acquirers not realizing profits from acquisitions (Hitt et al., 1996). One of the important transaction difficulties is “bounded rationality”(Jones, 2004) that explains the high complexity and uncertainty within acquisition negotiations. Acquirers may not easily predict potential gains between the acquiring and acquired firms’assets. This uncertainty may lead to problems in integration processes and harm innovation efforts because economic of scale is often lower than predicted. Another negative effect is that the acquisition processes usually absorb much managerial time and energy. M&As require extensive preparation, negotiations, analyses, and evaluations. During this process, the attention of top managers may be diverted from internal activities such as developing new products and innovative technologies (Hitt, Hoskisson, & Ireland, 1990), at least in the short turn. Having engaged in a mass of M&A activities, firms have to find solutions of the integration problems if they want to effectively undertake other M&As in the future.

In an accelerating competitive environment, pursuing strategic advantages seem to require expanding, learning, and innovating at a faster speed. But how “speed” influences organizational performance is remain unclear (Barkema et al., 2002). Addressing the “Speed Trap”debate, Perlow, Okhuysen, and Repenning (2002) revealed that although fast decision making initially helped organizations achieve their desired growth, they often trigger large financial outlays. The resulting speed-up exhaustion of firm resources in turn accelerates managerial decision making process. Such actions move in cycles, and induce a “speed trap”when managers felt increasingly pressure for actions. It is popular belief that organizations in a competing environment need to change ever faster. Mergers and acquisitions thus function as a mechanism to change and restructure in which firms acquire new capabilities, competences, and even markets. But, intensive acquisitions also cause short term friction, tension, and indigestion in post-acquisitions period. An organization changes too slowly stay behind as competitors move ahead. However, the speed of M&As will be too high as organizational members reach their cognitive limits and even diminish their returns (Dierickx & Cool, 1989). Barkema, Baum, and Mannix thus suggest that organizations have an “optimal pace”of change, restructuring, and M&As. “Such an optimal pace may in turn cause the emergence of rhythms, or pulsating change,

whereby discrete meso-level changes are initialed at regular time intervals that leave organization members sufficient tome to absorb the changes before the next changes are initialed”(Barkema et al., 2002: 924). Indeed, M&A research suggested that optimal path and rhythm exist for implementing M&As or foreign Greenfield operations (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Thus from theories of M&A indigestion and the speed trap, this study argues that firm’s M&A - performance relationship will be negative in the short term, however, this relationship will turn to be positive if M&A pace and rhythm is adequate. Moreover, the successful M&A pace and positive M&A –performance is related to the degree of organizational congruence between environment, strategy, culture, and structure.

Congruence refers to “the degree to which the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and structures of one component are consistent with those of the others”(Nadler & Tushman, 1997: 34). An extensive body of research suggests that “an organization’s ability to achieve its goal is a function of the congruence between various components”(Fry & Smith, 1987: 117). Most interest of the literature can be followed by the emergence of the perspective of open system describes that the structure depends on environment and strategy. And when the environment changes, organizational design is the result of a process of strategic choice (Randolph & Dess, 1984). If the components fit well as the environment changes, then the organization functions effective, and leads to high organizational performance. Any theory building is an attempt to model some aspect of the real world. To do this, Dubin (1978) and Fry and Smith (1987) distinguish four central components of congruence theory. The first component is the units of a theory whose relationships are of interest to the research. Second, laws of relationship among units are lawful statements that specify how they are linked, connected, or associated. Third, boundaries of a theory examine the defining value of the units comprising the model. And finally, a system state is a condition that all units represent characteristic values that are deterministic and stable through time.

Besides expanding the time period to investigate M&A –performance relationship, a congruence model of organizational design also suggests another solution to relax M&A indigestion. Enriching a simple dyadic fit, such as a fit between corporate strategy and organizational structure (Chandler, 1962), the congruence theory advances a broader framework based on four dimensions of an organization: individual, formal organization, informal organization, and the work (Nadler & Tushman, 1992, 1997; Russo & Harrison, 2005). A more precise definition by Mealiea and Lee (1979) indicates two major types of organizational congruence: macrocongruence and microcongruence. The former concerns the formation of the relationship between the environment and the organizational structure, and the latter

describes the relationship between organizational structure and individual behavior. The higher degree of congruence, the higher is the organizational performance. This study uses congruence model (macrocongruence) to investigate whether or not fits between M&As (strategy) and critical organizational dimensions (structure) enhance one form of organizational performance (innovativeness). Besides the over-estimated assets of the acquired firms and the over-expected synergies by integrating many entities, many M&As fail because there is a cultural crash between the associated firms. Thus, four units including environment, structure, strategy, and culture will be discussed in this study. Here, this study explores answers to two questions proposed by Nadler and Tushman (1997: 35) and Russo and Harrison (2005: 583). First, Are organizational architecture sufficient to meet the demand of the environment? In this context, this study considers how the process of mergers and acquisitions could be improved by the adoption of proper structure and culture in the post-acquisition period. Second, Do organizational architecture moderates the relationship between work and performance? Here, this study considers how the M&A – performance relationship could be bettered managed by the adequate strategy –structure and strategy –culture fits.

3. The Acculturative Fit in M&As

Organizational culture refers to a shared view of reality, collective beliefs, value system, and the social and cognitive environments reflected in consistent patterns of behaviors of organizational members (Detert & Schroeder, 2000, O’Reillyet al., 1991, Schein, 1985). Studies investigating organizational culture had focused on values as the major component in functioning organization (Enz, 1988). A value system defines norms, symbols, and cultural activities within an organization. Culture has pronounced effects on successful acquisitions because the acculturation process within both acquirer and the acquired firms affects post-acquisition performance. Cultural compatibility of the M&A partners is crucial to the success of corporate combination (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993). Acculturation is referred to as changes induced in (two cultural) systems as a result of the diffusion of cultural elements in both directions (Berry, 1980). The acculturation process occurs at both individual and group levels in the stages: contact, conflict and adaptation. Although this process is a balanced two-way flow, members in one culture usually try to dominate members in the other culture (Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988). Based on the cross-cultural studies of the acculturation process and modes (e.g., Berry, 1983, 1984; Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1986, 1988, 1993), four modes were defined by the degree to which the acquired firm’s members want to preserve their culture and the extent to which they are attracted to the acquirer’s culture.

Integration occurs when the acquired firm’s members want to preserve their culture, identity, autonomy, and independence. Berry (1983) suggested that integration involves interaction and adaptation between two cultures and requires mutual contributions by both firms to evolve a new culture which represents the best of each culture. Thus, the acquired firm’s members desire to maintain many of their own assumptions, beliefs, systems, and organizational practice; simultaneously, they also wish to be integrated into the acquirer’s culture. Integration is the most likely mode of acculturation the acquirer uses when an acquired firm attempts to maintain some of its culture, and is simultaneously integrated into acquirer’s culture (Katz & Kahn, 1978). As a result, integration leads to some degree of change in both sides that represents substantial potentials for cultural collisions and fragmentation (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993).

Assimilation is a unilateral process for the acquired employees to abandon their

own culture, and adopts the culture of the other. This may occur if the acquired firm is unsuccessful and the acquirer is successful (Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988). Employees and managers of the acquired firm perceive that their own culture is dysfunctional and impeding organizational performance. Thus, both cultural and structural assimilation may occur in this situation. However, separation still may occur if some members of the acquired firm are unwilling to relinquish their culture and system. For acquirers seek to adopt assimilation acculturation, they avoid this problem by displacing resistors.

Separation involves acquired firm’s attempts to preserve their own culture and practice and refuse to become assimilated with the acquirer, (Berry, 1983). If allowed by the acquirer to do so, the acquired firm will function as a separated division under the financial control of the parent company. Therefore, there will be minimal culture exchange between the two entities if separation mode of acculturation takes place in M&As. This may occur if the acquired firm is successful and the acquirer does not come from the same industry (Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988). Other than in open marriage that the acquirer is tolerant of multi-culturation, the separation mode is likely to result in cultural collision (Cartwright & Cooper, 1994).

Deculturation involves losing cultural contact with both sides existing culture. It

may occur if the members of the acquired firm are dissatisfied with their own culture and practice, but disagreed with the attractiveness of the culture of the acquirer. As a result, employees and managers experience confusion and alienation.

Based on Berry’s studies, Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1986, 1988) proposed the preferred mode of acculturation concerning the acquirer’s M&A diversification strategy and multiculturalism. Multiculturalism refers to “the degree to which an organization values cultural diversity and is willing to tolerate and encourage it”

(Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988, p. 83). If the firm is unicultural, it should emphasize the uniqueness of employee values, norms, beliefs and rewards system, and pursue the consistency of corporate goals, strategies, and practices. Conversely, the multicultural firm is more likely to allow the acquired firm to retain its existing culture and structure.

Based on the acquired firm’s perspective, Berry’s (1983) scheme for the acculturative mode was composed by two dimensions: the degree to which the acquired firm’s members want to preserve their culture and the extent to which they are attracted to the acquirer’s culture. From the acquirer’s viewpoint, scheme of Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988) was composed by two dimensions: the acquirer’s multiculturalism and the type of M&A. In fact, both partners are crucial in the acculturation process (Larsson & Lubatkin, 2001). For example, Elsass and Veiga (1994) suggested that the process of acculturation was a dynamic tension between the forces of cultural differentiation (the acquired firm’s side) and the force of organizational integration (the acquirer’s side). Following viewpoints of Berry (1983) and Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988), the acculturation process is the dynamic of the acquirer’s attractiveness to the members of the acquired firm (the acquired firm’s side), and the acquirer’s degree of uniculturalism (the acquirer’s side).

The M&A diversification strategies regard the type of M&A. Acquirers adopt M&As to realize synergistic economics in related diversifications or financial economics in unrelated diversifications (Hill & Hoskisson 1987). Synergistic economics in related M&As enhance performance from shared value and utilized jointly inputs or activities. Synergy usually comes from tangible interrelationships such as corporate policies for jointly purchasing input, joint development of exploratory and exploitive technologies and joint distribution systems or intangible interrelationships such as know-how and knowledge transfer between divisions (Hill et al., 1992, Hoskisson et al., 1993). To realize synergistic economics, both acquiring and acquired units should first establish effective links and similar culture. Second, information flow must be efficiently transferred between divisions and the head office. Thus, an acquirer typically imposes its own culture on that of acquired firms in related acquisitions (Chatterjee, 1986). The reason for this imposition is likely that the acquirer often has knowledge-based and technological advantages, and pressures the acquired firm to adopt its organizational culture and management systems. However, in unrelated acquisitions—since knowledge and technology of the acquirer may be elementary—acquirers are unwilling to intervene in the daily activities of the acquired firm. Thus, the likelihood of the acquirer to impose its own culture on the acquired unit is low. A somewhat different perspective concluded that high performance for related M&As over a prolonged period requires a strong and adaptive uniculture.

Generally, The acquirer’s managers in related M&As see their roles as being radical re-designers for the acquired firms and introduce wild scale change. Thus, the acquired firms are expected to totally adopt and assimilate into the culture and practice of the dominant acquirers (Cartwright&Cooper, 1994). When a firm pursues a related M&A strategy, assimilation will be the preferred mode of acculturation. Thus, this study proposes that the fit of related M&A strategy–assimilation mode of acculturation will be positively related to firm post-acquisition performance.

Hypothesis 1. The interaction between related M&A and the acquirer’s uniculturalism will be positively related to post-acquisition performance.

Hypothesis 2. The interaction between related M&A and the acquirer’s attractiveness to the members of the acquired firm will be positively related to post-acquisition performance.

Financial economics arise from portfolio management based on the assumption that unrelated diversification M&As enable acquirers to reallocate cash flow. The acquirer can use monitoring systems, hire police and provide incentives to encourage efficiency. Firms pursuing this strategy thus optimize allocation of capital and resources and enhance exploration of new products in new markets or industries (Jones & Hill, 1988). This strategy frees top mangers of the acquirer from involvement in daily activities of the target firms. After restructuring, the acquiring managers monitor the performance of each acquired firm and intervene only when necessary because these unrelated divisions only have the lowest need for coordination (Hitt et al., 1990, Hitt et al., 1996). When an acquired firm wants to preserve its culture, it attempts to resist the culture of the acquirer and retain a separate or independent culture. This resistance generally happens during unrelated acquisitions (Chatterjee, 1986). Organizations should create a suitable culture that strengthens their strategies and structure. Generally, firms pursuing related acquisition strategies may need to emphasize integration, coordination, and cooperation between headquarters and divisions. Thus, assimilation mode of acculturation can reduce the costs associated with exchange knowledge and technology, and likely shapes a common language and increases communication effectiveness. Conversely, the organizational culture in firms pursuing unrelated acquisition strategies should emphasize the values of autonomy and dependency as divisions have weak connections. That is, managers in the acquiring firm care and value customers and employees of the acquired firm. Generally, managers in unrelated M&A acquiring firms see their roles as being supportive and further facilitating the development and growth of the acquired firms. Less interference and more tolerance of multiculturation

are necessary herein. Thus, the acquired firms are permitted to maintain autonomous operations and cultural separation (Cartwright&Cooper, 1994). When a firm pursues an unrelated M&A strategy, separation will be the preferred mode of acculturation. Thus, this study proposes that the fit of unrelated M&A strategy–separation mode of acculturation will be positively related to firm post-acquisition performance.

Hypothesis 3. The interaction between unrelated M&A and the acquirer’s multiculturalism will be positively related to post-acquisition performance.

Hypothesis 4. The interaction between unrelated M&A and the acquirer’s unattractiveness to the members of the acquired firm will be positively related to post-acquisition performance.

4. The Structural Fit in M&As

The M-form and CM-form were suggested as classic forms for achieving related and unrelated diversification strategies (Williamson, 1985). Based on studies of Williamson, M-form is multidivisional with decentralized operational control, centralized strategic control, and centralized financial control that put corporate center emphasis on profit criteria and resources allocation between divisions (Hill, 1988). The M-form centers must design appropriate incentive and control systems to supervise divisional performance, and reallocate organizational resources to the most promising and expanding divisions. Conversely, the CM-form centers are highly involved in the operational activities of divisions. Therefore divisional autonomy is constrained by business-level strategies and operational decisions determined in the headquarters. For implementing synergy, elegant integration mechanisms are necessary for coordination among divisions. Williamson (1975) considered that the CM-form firms stand for a corrupted multidivisional with a multidivisional structure inferior to that of an M-form. Hill and colleagues (Hill 1988, Hill et al. 1992, Hoskisson et al. 1993) argued that corporate centers should lead divisions to realize synergistic economics. Renaming a corrupted multidivisional as a centralized multidivisional, CM-form is thus characterized by corporate center involvement in divisional operation. Conversely, a decentralized multidivisional (M-form) is characterized by corporate center that does not involve in divisional operation. To distinguish M-form from CM-form, there are two structural criteria: centralization in headquarters and integration between divisions.

Firms pursuing related diversification strategy can realize benefits from economics of scope, and these benefits can be achieved from the cooperation between divisions. Because a related M&A firm tries to increase value by sharing resources, skill, knowledge, and technology between divisions, cooperation among corporate

center and divisions is necessary to achieve economic synergy and facilitate investment in specialized assets. Child (1984) argued that centralization in the corporate office and interdependencies between divisions in related diversified firms encourage corporate managers to preserve control over the divisional operation and ensure sufficient coordination. Hoskisson and colleagues (1993) also noted that the interdivisional sharing of resources and technologies was achieved through centralization activities. Thus, some degree of centralized control over operational and strategic decision in related M&As is necessary. Centralized multidivisional (CM-form) is proposed as a cooperative organization (Hill et al., 1992) because the interdependent divisions must be tightly coupled in related diversified firms (Hill & Hoskisson, 1987). Generally, a related M&A firm adopting a CM-form structure can increase centralization strategic control (Hitt et al. 1996). When a firm pursues a related M&A strategy, centralization will be the preferred characteristic of organizational structure.

In addition to centralization, a high degree of inter-divisonal integration and coordination are necessary to realize synergistic economies. Linkages must be made in divisions in related M&As because key decisions are not made in divisional level (Hill & Hoskisson, 1987) of vertically or horizontally integrated firms. Firms with highly related divisions usually cause a crucial problem that coordination may create performance ambiguities (Hoskisson et al. 1991). Poor divisional performance might be due to poor marketing decisions in corporate center or poor quality and productivity in individual division. Thus headquarters should assess coordinating divisions as an entity in addition to individual operating performance. Further, related M&As require integration mechanisms and functional experts to enhance both horizontal and vertical communication between divisions and headquarters. For example, technological innovations in one division might affect operations of highly related divisions. The integration mechanism may vary from simple liaison role to complex permanent team, depending on the extent of centralization and interdependence. This study highlights importance of integration between divisions and centralization in headquarters. Thus:

Hypothesis 5. The interaction between related M&A and centralization will be

positively related to post-acquisition performance.

Hypothesis 6. The interaction between related M&A and integration will be

positively related to post-acquisition performance.

Firms pursuing unrelated diversification strategy can realize benefits from efficient internal governance mechanisms, and these benefits can be achieved from

the competitions between divisions. A firm implementing this strategy is willing to enter new domains in the future. In an unrelated M&A strategy, value is created by exploiting the ability of top managers to administrate unfamiliar firms better than the existing top managers of the acquired firm (Porter, 1987). This strategy frees top mangers of the acquirer from involvement in daily activities of the acquired firms. For achieving governance economics, a decentralized multidivisional (M-form) structure is required in unrelated M&As (Chandler, 1998, Hill, 1988, Hill et al., 1992, Williamson, 1975). In these unrelated M&A firms, operating and business-level decisions are left to the divisional managers. And for the corporate center, decentralization allows for high autonomy and accountability for divisions because divisional performance is evaluated by objective financial criteria. After restructuring, corporate managers monitor the performance of each acquired firm and intervene only when necessary because these unrelated divisions only have the lowest need for coordination. Therefore, the decentralized multidivisional structure in unrelated M&As will be associated with the lowest bureaucratic costs because this strategy-structure fit is based upon poor interdependence which each divisions is a self-contained unit (Jones & Hill, 1988). This fit also has the lowest need for coordination between divisions because the post-acquisition structure is simple and information processing needs are low (Thomson 1967). Within these unrelated divisions, “standardization and formalization are the characteristic forms of control” (Jones and Hill, 1988, p. 164) because “incentive system for divisional managers should be linked to divisional returns”(Hoskisson et al. 1993, p. 283). These decentralized multidivisional managers are responsible for all relevant operation decisions and performance under their control. So, they have a strong incentive to seek for the efficiency of divisional operations (Hill et al. 1992). When a firm pursues an unrelated M&A strategy, decentralized multidivisional will be the preferred organizational structure.

In addition to decentralization, a low degree of inter-divisonal integration and coordination are necessary to realize governance economics because the adoption of least cost behavior and the capital flow to high yield uses are encouraged. Excessive linkage is unnecessary because functional autonomy of divisions is the major concern. Integration between divisions in unrelated M&As only increase performance ambiguities and bureaucratic costs without enhancing high performance. This study highlights importance of autonomy in divisions and decentralization in headquarters. Thus:

Hypothesis 7. The interaction between unrelated M&A and decentralization will

Hypothesis 8. The interaction between unrelated M&A and integration will be

negatively related to post-acquisition performance.

5. Methods

Data Collection

For testing hypotheses, this study obtained structural, cultural, and strategic data through a survey in 2008, and collected performance data (ROA) from databases. Organizational level data was drawn from the top 1000 Taiwanese electronic and computer firms reported by China Credit Information Service (CCIS), an authorized credit-rating company in Taiwan. The companies are classified into four industries: computer manufacturing; integrated circuits; opto-electronics and telecommunication. About 300 in top 1000 firms had undertaken M&As in the past five year. Questionnaires were sent to general managers of these 300 merged firms and 114 were returned. Corporate ROA data were collected from the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) and the Securities and Futures Commission databases, Ministry of Finance, ROC, Taiwan.

M&A Strategy

Related and unrelated diversification are classified by the difference of SIC codes between the acquirer and the acquired firms.

Organizational Structure

This study adopts centralization dimension developed by Ghoshal & Nohria (1989, p. 336). It is measured by estimates of divisional managers on the degree of head-office influence on divisional (i) introduction of new products, (ii) changes in product design, (iii) changes in manufacturing processes, and (iv) career development plans for senior managers (five-point scale, alpha = 0.85). In integration dimension, Burgelman and Doz (2001) argued that value creation in related diversification relies on cross-divisional integration which contains operational integration and strategic integration. Operational integration involves routinely independent activities between divisions; and strategic integration involves nonroutine activities. Containing both operational and strategic integration, integration dimension is measured by estimates of divisional managers on the degree of interdivisional activities on (i) joint procurement, (ii) sharing a sales force, (iii) sharing production information, (iv) sharing best practices in various administrative processes, and (v) involving the combination of resources from different divisions to create new business (five-point scale, alpha = 0.87).

Elsass and Veiga (1994) suggested that the process of acculturation is a dynamic tension between the forces of cultural differentiation (the acquired firm’s side) and the force of organizational integration (the acquirer’s side). Following Berry (1983) and Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988), this study views the acculturation process as the dynamic of the acquirer’s attractiveness to the members of the acquired firm (the acquired firm’s side), and the acquirer’s degree of uniculturalism (the acquirer’s side).

Organizational Performance

The above hypotheses wish to test effects of achieving strategy-structure and strategy-culture fits in M&As. The appropriate measure for post-acquisition performance is the economic benefit by the efficiency use of resources within the merged entity. Three possible candidates are return on assets (ROA), return on investment (ROI) and return on equity (ROE). This study adopted ROA because it demonstrates greater year on year stability (Hill et al. 1992). This study used average ROA for the next three year after M&As because the average smooth out annual waves in the financial data. For instance, a firm’s average ROA in 2005, 2006, and 2007 was adopted if the firm undertook an M&A in 2004. Corporate ROA data were collected from the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) and the Securities and Futures Commission databases, Ministry of Finance, ROC, Taiwan. This study also used firm’s advertising and R&D expenditures as controls because they are expected to have significantly positive effects on profitability.

6. Results

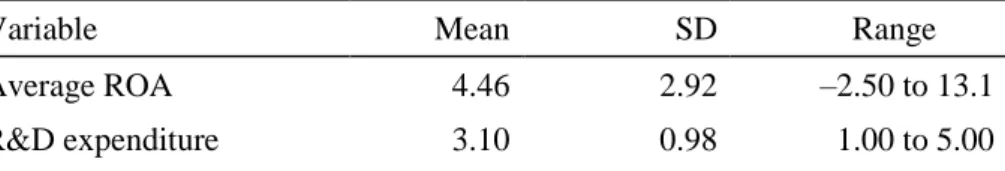

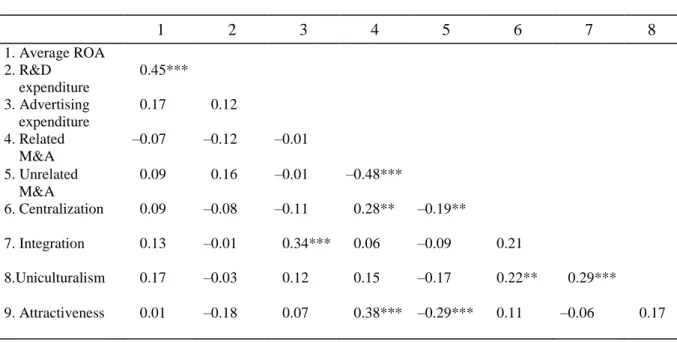

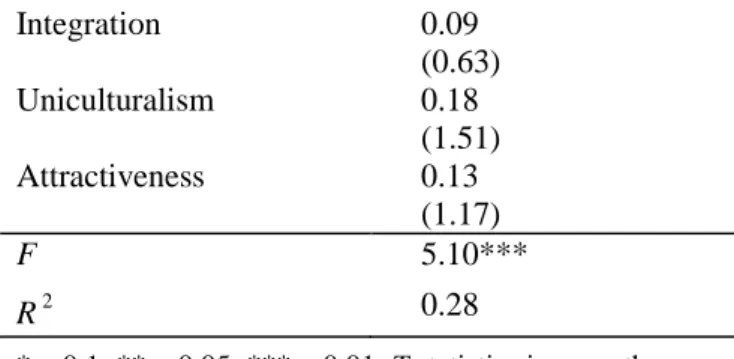

Before regression analyses, descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the sample are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The base regression (regression without concerning interaction term; Y = a + b1X + b2U + b3V + b4W + e) is reported in Table 3. This

model (p < 0.01; R2= 0.28) is significant only on R&D expenditure, not on advertising expenditure. The reason might be the sample characteristics. Most Taiwanese electronic companies earn profits from R&D activities, not from marketing activities. It is also noticeable that M&A strategy, post-acquisition organizational structure, and acculturative mode are not significant in this model. The finding is consistent with the argument that post-acquisition performance is not the result of M&A strategy alone.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Variable Mean SD Range

Average ROA 4.46 2.92 –2.50 to 13.1

Advertising expenditure 3.70 0.91 1.00 to 5.00 Related M&A 0.73 0.45 0.00 to 1.48 Unrelated M&A 0.80 0.58 0.00 to 2.02 Centralization 0.09 1.18 –2.65 to 2.64 Integration –0.08 0.98 –3.08 to 2.15 Uniculturalism –0.05 1.13 –2.38 to 2.33 Attractiveness 0.00 1.11 –2.87 to 2.87 n=114

Table 2 Correlation Matrix

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01; Number in each cell given in parentheses. Two tailed tested. n=114.

Table 3 Base Regression Result

Independent

variables Average ROA

R&D expenditure 0.80*** (5.34) Advertising expenditure 0.16 (0.95) Related M&A –0.34 (–0.77) Unrelated M&A 0.13 (0.39) Centralization 0.16 (1.34) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Average ROA 2. R&D expenditure 0.45*** 3. Advertising expenditure 0.17 0.12 4. Related M&A –0.07 –0.12 –0.01 5. Unrelated M&A 0.09 0.16 –0.01 –0.48*** 6. Centralization 0.09 –0.08 –0.11 0.28** –0.19** 7. Integration 0.13 –0.01 0.34*** 0.06 –0.09 0.21 8.Uniculturalism 0.17 –0.03 0.12 0.15 –0.17 0.22** 0.29*** 9. Attractiveness 0.01 –0.18 0.07 0.38*** –0.29*** 0.11 –0.06 0.17

Integration 0.09 (0.63) Uniculturalism 0.18 (1.51) Attractiveness 0.13 (1.17) F 5.10*** R2 0.28 *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01; T statistics in parentheses; Unstandardized regression coefficients were used.

For testing hypotheses, Table 4 reports unstandardized coefficients for various interaction terms, along with change in R2(△R2) following adding each interaction term into the base regression model, and the partial F test for the significance of △

R2. The significant effects that the interactions of related M&A × uniculturalism (p < 0.05) and related M&A × attractiveness (p < 0.05) had on average ROA provides support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. It reveals that the appropriate fit of related M&A–assimilative acculturation will be beneficial for better post-acquisition performance. The significant effects that the interactions of unrelated M&A × uniculturalism (p < 0.01) and unrelated M&A × attractiveness (p < 0.05) had on average ROA provides support for Hypotheses 3 and 4. The negative sign suggests that the interaction of greater unrelated M&A and less emphasis on uniculturation was positively related to ROA; and also that the interaction of greater unrelated M&A and less emphasis on attractiveness was positively related to ROA. These also reveal that the appropriate unrelated M&A–separation mode of acculturation will be beneficial for better post-acquisition performance. The significant effects that the interactions of related M&A × centralization (p < 0.05) and related M&A × integration (p < 0.01) had on average ROA provides support for Hypotheses 5 and 6. It reveals that the appropriate related M&A–CM-form will be beneficial for better post-acquisition performance. The significant effects that the interactions of unrelated M&A × integration had on average ROA (p < 0.05) provides support for Hypothesis 8. The negative sign suggests that the interaction of greater unrelated M&A and less emphasis on integration was positively related to ROA. However, the interaction of unrelated M&A and less emphasis on centralization was not statistically significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 is not supported.

Table 4 Conventional Moderated Regression Analysis on Average ROA

Interaction Term Coefficient Change R2 Partial F test

Related M&A × Attractiveness 0.48 0.034 5.14** Unrelated M&A × Uniculturalism –0.47 0.049 7.62*** Unrelated M&A × Attractiveness –0.36 0.030 4.55** Related M&A × Centralization 0.47 0.032 4.96** Related M&A × Integration 0.86 0.062 9.36*** Unrelated M&A × Centralization –0.33 0.023 2.45 Unrelated M&A × Integration –0.73 0.074 11.00*** *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Unstandardized regression coefficients were used.

References

Barkema, H. G., Baum, J. A. C., & Mannix, E. A. 2002. Management challenges in a new time. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5): 916 –930.

Berry, J. W. 1980. Social and culture change. In H. C. Triandis, R. W. Brishn (Eds).

Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology 5 211-279. Allyn & Bacon, Boston.

Berry, J. W. 1983. Acculturation: A comparative analysis of alternative forms. In R. J. Samuda, S. L. Woods (Eds). Perspective in Immigrant and Minority Education. 65-78. University Press of America. Lanham, MD.

Berry, J. W. 1984. Cultural relations in plural societies. Alternatives to segregation and their sociopsychological implications. In N. Miller, M. B. Brewer (Eds). Groups in Contact. 11-27. Academic Press. Orlando, FL.

Bowman, E. H., & Singh, H. 1993. Corporate restructuring the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 14: 5-14.

Bresman, H., Birkinshaw, J., & Nobel, R. 1999. Knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 30: 439–462.

Burgelman, R. A., Christensen, C. M., & Wheelright, S. C. 2004 Strategic Management of Technology and Innovation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Burgelman, R., Y. Doz. 2001. The power of strategic integration. MIT Sloan

organizational marriage. Acad. Management Exe. 7(2) 57–70.

Cartwright, S, C. L. Cooper. 1994. The human effects of mergers and acquisitions. J.

Organ. Behav. 1 47–61.

Chandler, A. D. 1962. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the

Industrial Enterprise. MIT Press. Cambridge, MA.

Chandler, A. D. 1998. Corporate strategy and structure: Some current considerations.

Society January/February 347–350.

Chatterjee, S. 1986. Types of synergy and economic value: The impact of acquisitions on merging and rival firms. Strategic Management J. 7 119–140.

Chen, H., & Chen, T. J. 2003. Governance structure in strategic alliances: Transaction cost versus resource-based perspective. Journal of World Business, 38: 1-14. Child, J. 1984. Organization. A Guide to Problems and Practice, Harper & Row,

London, U.K.

de Man, A., & Duysters, G. 2005. Collaboration and innovation: A review of the effects of mergers, acquisitions and alliances on innovation. Technovation, 25: 1377–1384.

Detert, J. R., & Schroeder, R. G. 2000. A framework for linking culture and improvement initiatives in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 25(4): 850- 863.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. 1989. Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competing advantage, Management Science, 35: 1504- 1514.

Dorf, R. C., & Byers, T. H. 2005. Technology Ventures: From Idea to Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dubin, R. 1978. Theory Building. New York: Free Press.

Elsass, P. M., J. F. Veiga. 1994. Acculturation in acquired organizations: A force-field perspective. Human Relations 47(4) 431-454.

Enz, C. 1988. The role of value congruity in intraorganizational power. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33: 284- 304.

Fry, L. W., & Smith, D. A. 1987. Congruence, contingency, and theory building. Academy of Management Journal, 12(1): 117- 132.

Ghoshal, S., N. Nohria. 1989. International differentiation with multinational corporations. Strategic Management J. 10 323-337.

Gulati, R., & Singh, H. 1998. The architecture of cooperation: Managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43: 781- 814.

Hill, C. W. L. 1988. Internal capital market controls and financial performance in multidivisional. J. Industrial Econom. 37(1) 67–83.

approach. Australia: John Wiley & Sons.

Hill, C. W. L., M. A. Hitt, R. E. Hoskisson. 1992. Cooperative versus competitive structures in related and unrelated diversified firms. Organ. Sci. 3 501–521. Hill, C. W. L., R. E. Hoskisson. 1987. Strategy and structure in the multiproduct firm.

Acad. Management Rev. 12 331–341.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Ireland, R. D. 1990. Mergers and acquisitions and managerial commitment to innovation in M-form firms. Strategic Management Journal, 11: 29–47.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., Johnson, R. A., & Moesel, D.D. 1996. The market for corporate control and firm innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5): 1084–1119.

Hitt, M. A., Keats, B. W., Harback, H. F., & Nixon, R. D. 1994. Rightsizing: Building and maintaining strategic leadership and long-term competitiveness. Organizational Dynamics, 23(2): 18–32.

Hitt, M. A., R. E. Hoskisson, R. A. Johnson, D.D. Moesel. 1996. The market for corporate control and firm innovation. Acad. Management J. 39 1084–1119. Hitt, M. A., R. E. Hoskisson, R. D. Ireland. 1990. Mergers and acquisitions and

managerial commitment to innovation in M-form firms. Strategic Management

J. 11 29–47.

Hoskisson, R. E., C. W. L. Hill, H. Kim. 1993. The multidivisional structure: Organizational fossil or source of value? J. Management 19 269–298.

Hoskisson, R. E., M. A. Hitt, C. W. L. Hill. 1991. Managerial risk taking in diversified firms: An evolutionary perspective. Organ. Sci. 3 296–314.

Jones, G. R. 2004. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change. New Jersey: Pearson. Jones, G. R., C. W. L. Hill. 1988 Transaction cost analysis of strategy-structure choice.

Strategic Management J. 9 159–172.

Katz, D., R. Kahn. 1978. The Social Psychology of Organizations. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Kirchmaier, T. 2003. Corporate restructuring of British and German non-financial firms in the late 1990s. European Management Journal 21(4): 409-420.

Larsson, R., Bengtsson, L., Henriksson, K., & Sparks, J. 1998. The interorganizational learning dilemma: Collective knowledge development in strategic alliances. Organizational Science, 9: 285–305.

Larsson, R., M. Lubatkin. 2001. Achieving acculturation in mergers and acquisitions: An international case survey. Human Relations. 54(12) 1573-1607.

Mealiea, L., & Lee, D. 1979. An alternative to macro-micro contingency theories: An integrative model. Academy of Management Review, 4: 333- 346.

Review of Industrial Organization, 19: 181–197.

Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. 1992. Designing organizations that have good fit: A framework for understanding new architectures. In D. A. Nadler, M. Gerstein, & R. B. Shaw (Eds.), Organizational architecture: 39-56. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. 1997. Competing by design: The power of organizational architecture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nahavandi, A., A. R. Malekzadeh. 1986. The role of acculturation in the implementation of mergers. J. A. Pearce, R. B. Robinson, eds. Academy of

Management, Best Papers Proceedings, 140-144.

Nahavandi, A., A. R. Malekzadeh. 1988. Acculturation in mergers and acquisitions.

Acad. Management Rev. 13(1) 79-90.

Nahavandi, A., A. R. Malekzadeh. 1993. Organizational Culture in the Management

of Mergers. Westport, CA: Quorum Books.

O’Reilly,C. J., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. 1991. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34: 487- 516.

Perlow, L. A., Okhuysen, G. A., & Repenning, N. P. 2002. The speed trap: Exploring the relationship between decision making and temporal context. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5): 931- 955.

Porter, M. E. 1987. From competitive advantage to competitive strategy. Hardard Bus.

Rev. May-June 43–59.

Prajogo, D. I., & Sohal, A. S. 2006. The integration of TQM and technology/R&D management in determining quality and innovation performance. Omega, 34(3): 296–306.

Randolph, W. A., & Dess, G. G. 1984. The congruence perspective of organization design: A conceptual model and multivariate research approach. Academy of Management Journal, 9: 114- 127.

Russo, M. V., & Harrison, N. S. 2005. Organizational design and environmental performance: Clues from the electronics industry. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4): 582- 593.

Schein, E. 1985. Organizational Culture and Leadership, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Publishers.

Schijven,M.2005.Curing thefirm’sindigestion:Organizationalrestructuring and the dynamics of acquisition performance. Academy of Management Best Conference Paper: M1-M6.

Schilling, M.A. 2005. Strategic Management of Technological Innovation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Thompson, J. 1967. Organizations in action. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Vermeulen, F., & Barkema, H. G. 2002. Pace, rhythm, and scope: Process dependence in building a profitable multinational corporation. Strategic Management Journal, 23: 637- 653.

Williamson, O. E. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implication. Free Press, New York.

Williamson, O. E. 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. Free Press, New York.