台灣高中英文教科書中語言行為教學之研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) EFL Speech Act Teaching: Analysis of Senior High School English Textbooks in Taiwan. 立. A Master 治Thesis 政 Presented to 大 Department of English,. ‧ 國. 學. National Chengchi University. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. i n U. Ch. v. hi In e Partial n g cFulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by S-hua Chen July, 2010.

(3) Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Ming-chung Yu, for his enthusiastic guidance to my study of speech act teaching. The way how speech act is implemented in daily life and the cultural differences it carries add to the research interests and merits. It was Dr. Yu’s continuous advices and supports that made this thesis possible. Sincere appreciation also goes to Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh and Dr. Tai-hsiung Yang, members of my oral defense committee, for giving invaluable comments and suggestions to refine my thesis.. 立. 政 治 大. Moreover, I would like to show my deepest thanks to my dear parents, my. ‧ 國. 學. beloved husband, and my cute 8-year-old daughter, Jennie. Without them, I would not have had sufficient time and strong determination to finish this study. I especially. ‧. want to thank Jennie for continuously writing considerate letters to encourage me to. y. Nat. io. sit. finish my thesis. She is such an angel to me.. n. al. er. Special thanks also need to go to all the staffs of my department. As a director. i n U. v. of the department of Academic Affairs at Lin-kou Senior High School, without their. Ch. engchi. full-hearted and unselfish assistances, there is no sufficient time for me to focus on my thesis.. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... iii 碩士論文提要............................................................................................................ viii Abstract .......................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 Motivation and Goal................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of the Study .................................................................................................. 3. 政 治 大 Organization of the Chapters...................................................................................... 4 立 Significance of the Study ........................................................................................... 4. ‧ 國. 學. CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................ 7 Communicative Competence ..................................................................................... 7. ‧. Sociolinguistic Competence ....................................................................................... 8. sit. y. Nat. Speech Act Theory ..................................................................................................... 9. io. er. Universality Versus Cultural-Specificity of Speech Acts...................................... 10 Context .................................................................................................................. 11. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. Cultural Differences Between American and Chinese Speech Acts ........................ 13. engchi. Compliment........................................................................................................... 13 Request.................................................................................................................. 17 Apology ................................................................................................................. 20 Complaint ............................................................................................................. 25 Refusal .................................................................................................................. 29 Supportive Moves and Small Talk ........................................................................ 32 Studies of Speech Acts in ELT Materials ................................................................ 35 Research Questions .................................................................................................. 36 Hypotheses ............................................................................................................... 37 iv.

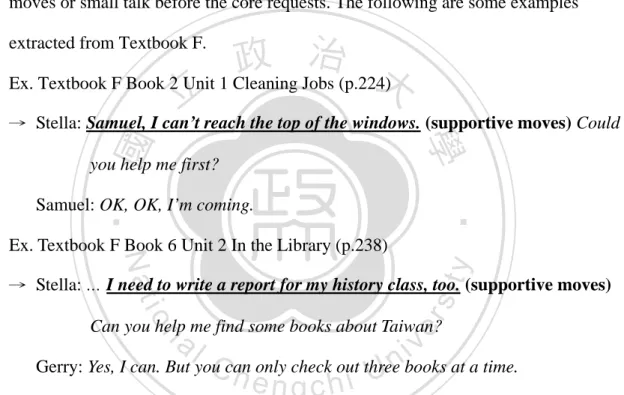

(5) CHAPTER 3 METHOD .............................................................................................. 39 Materials ................................................................................................................... 39 Procedure.................................................................................................................. 40 Data Analysis ........................................................................................................... 41 Frequency of Compliment, Request, Apology, Complaint, and Refusal............... 41 Cross-Cultural Differences in Speech Acts .......................................................... 41 Supportive Moves and Small Talk ........................................................................ 48 CHAPTER 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ............................................................ 49 Frequencies of the Five Much Used Speech Acts .................................................... 49. 政 治 大. Preference: American or Chinese ............................................................................. 51. 立. Compliment........................................................................................................... 51. ‧ 國. 學. Request.................................................................................................................. 61 Apology ................................................................................................................. 67. ‧. Complaint ............................................................................................................. 74. sit. y. Nat. Refusal .................................................................................................................. 80. io. er. Cross-cultural Comparisons and Contrasts in Textbooks or Teachers’ Manuals .... 94. al. Textbooks .............................................................................................................. 94. n. v i n Ch Teachers’ Manuals ............................................................................................... 96 engchi U. The Occurrence of Supportive Moves or Small Talk ............................................ 100 Explanations of Cultural Differences in Textbooks or Teachers’ Manuals ........... 102 Textbooks ............................................................................................................ 102 Teachers’ Manuals ............................................................................................. 109 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION.................................................................................... 110 Summary of the Major Findings ............................................................................ 110 Pedagogical Implications ....................................................................................... 115 Limitations of the Study ......................................................................................... 117 Suggestions for Future Research ............................................................................ 118 v.

(6) REFERENCES .......................................................................................................... 119 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................ 126 APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................ 157. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(7) LIST OF TABLES. Table 1.1 Frequencies of the five much used speech acts in two sets of textbooks….49 Table 1.2 Distribution of compliment strategies in two sets of textbooks…………...52 Table 1.3 Distribution of compliment topics in two sets of textbooks……………….54 Table 1.4 Distribution of compliment responses in two sets of textbooks…………...58 Table 1.5 Distribution of request strategies in two sets of textbooks………………...61 Table 1.6 Distribution of request responses in two sets of textbooks………………..65. 政 治 大. Table 1.7 Distribution of apology strategies in two sets of textbooks……………….68. 立. Table 1.8 Distribution of function of excuse me in two sets of textbooks…………...71. ‧ 國. 學. Table 1.9 Distribution of function of I’m sorry in two sets of textbooks…………….72 Table 1.10 Frequencies and percentage of complaints with or without modification..74. ‧. Table 1.11 Distribution of complaint strategies of head act in two sets of textbooks..76. y. Nat. io. sit. Table 1.12 Distribution of complaint strategies of solution in two sets of textbooks..79. n. al. er. Table 1.13 Distribution of refusal strategies in two sets of textbooks……………….80. i n U. v. Table 1.14 Distribution of substrategies of indirect refusals in two sets of textbooks.83. Ch. engchi. Table 1.15 Distribution of concreteness of explanations in two sets of textbooks…..88 Table 1.16 Distribution of refusal subjects in two sets of textbooks…………………90 Table 1.17 Frequencies and percentage of refusals with or without positive opinions first………………………………………………………………………...92 Table 1.18 Frequencies and percentage of speech acts with or without supportive moves or small talk………………………………………………………100 Table 1.19 Distribution of preference (American or Chinese) in two sets of textbooks…………………………………………………………………111. vii.

(8) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:台灣高中英文教科書中語言行為教學之研究 指導教授:余明忠 博士 研究生:陳司樺. 立. 論文提要內容:. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 溝通式語言教學(CLT)的原則和特色自從 1995 年就被帶進台灣高中英文教. ‧. 科書的編纂。在溝通能力的四個構成要素之中,社會語言能力是成功溝通的關鍵. sit. y. Nat. 而且能夠經由語言行為的使用被展現出來。因此,本研究旨在探測語言行為教學. n. al. er. io. 在台灣英文教科書中是如何被呈現的。首先,五個最常被使用及研究的語言行為. Ch. i n U. v. ─恭維、請求、道歉、抱怨以及拒絕─在台灣最受歡迎的兩套高中英文教科書─. engchi. 遠東和三民─之對話中出現的次數被統計。然後,對話中主要運用到的觀點,美 國的或中國的,以及教科書和教師手冊中的跨文化對照跟比較被檢視。最後,以 跨文化的角度分析常和語言行為一起出現的支持性話語以及閒聊,同時,教科書 和教師手冊是否有相關的解釋也被探索。 研究結果顯示,五種語言行為當中的大多數在兩套教科書中並沒有被平均地 分佈,而以該五種語言行為的呈現手法來看,遠東版教科書在比例上運用較多的. viii.

(9) 中國式觀點,然而三民版教科書在比例上則運用較多的美國式觀點。但是,無論 兩套教科書較偏向哪一種觀點,在教科書以及其對應的教師手冊中幾乎沒有跨文 化的對照和比較。至於支持性話語和閒聊的呈現方式,研究結果顯示遠東版教科 書在恭維、請求和抱怨這三種語言行為的支持性話語和閒聊的呈現並不多,而三 民版教科書在請求和抱怨這兩種語言行為的支持性話語和閒聊的呈現也不多,無 法提供學生充足的練習機會,同時,就算有支持性話語和閒聊出現在語言行為. 政 治 大. 中,在教科書跟其對應的教師手冊中仍然沒有進一步的解釋以指出美國人跟中國. 立. 人在使用上的文化差異。基於本研究的研究結果,獲得之教學啟示如後。首先,. ‧ 國. 學. 雖然台灣的高中英文教科書,至少遠東版跟三民版,還沒如此地嚴肅看待語言行. ‧. 為教學,但對於老師來說,向學生介紹語言行為的知識卻是相當重要的,因為如. Nat. io. sit. y. 此一來,方能使他們學習如何更有效地與人溝通。再者,身為一位台灣的英文老. er. 師,既然語言行為以及伴隨的支持性話語和閒聊在教科書或教師手冊當中,幾乎. al. n. v i n Ch 沒有或很少有跨文化差異性的解釋存在,增加我們語言行為教學的知識就變成了 engchi U 一項不可或缺的事。此外,台灣教科書的出版者應該反省教科書中對話部份的適 當呈現方式,使老師能經由語言行為教學的實施改善同學的社會語言能力。最 後,本研究當中被用來分析語言行為呈現所運用的主要的觀點(美國的或中國的) 之分類系統,不僅對於未來針對台灣其它版本教科書做類似研究的研究者有幫 助,也提供第一線教師評判教科書中對話結構呈現適當與否之標準,同時也將語 言行為教學的背景知識灌輸給第一線教師。 ix.

(10) Abstract The principles and characteristics of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) have been brought into senior high school English textbooks editing in Taiwan since 1995. Among the four components of communicative competence, sociolinguistic competence is the key to successful communication and can be shown through the use of speech acts. This study, therefore, intended to probe into how speech act teaching. 政 治 大. is carried out in senior high school English textbooks in Taiwan. Firstly, the. 立. frequency of the five much used and explored speech acts—compliment, request,. ‧ 國. 學. apology, complaint, and refusal—in the conversation part of two sets of the most popular senior high school English textbooks in Taiwan—Textbook F and Textbook. ‧. S—was counted. Then, the preference, American or Chinese, as well as cross-cultural. y. Nat. io. sit. comparisons and contrasts in both the textbooks and teachers’ manuals, were. n. al. er. examined. Lastly, the common co-occurring phenomenon of supportive moves and. i n U. v. small talk in speech acts was analyzed cross-culturally and related explanations in. Ch. engchi. both the textbooks and teachers’ manuals were investigated as well. The results showed that most of the five speech acts were not appropriately distributed in both sets of the textbooks, and that Textbook F offered much more Chinese preference than American one, while Textbook S provided proportionately more American preference than Chinese one, in presenting the five speech acts. However, no matter which preference both sets of textbooks favored, there were almost no cross-cultural comparisons and contrasts made in the textbooks or their corresponding teachers’ manuals. As to the presentation of supportive moves and small talk, the findings showed that Textbook F did not present enough supportive x.

(11) moves and small talk in the speech acts of compliment, request, and complaint, and that Textbook S did not display enough supportive moves and small talk in the speech acts of request and complaint for students to learn from, and if supportive moves or small talk were presented, there were still no further explanations in the textbooks or their corresponding teachers’ manuals to point out cultural differences between American and Chinese usage. With regard to the findings in this study, some pedagogical implications are provided. Firstly, although the senior high school English textbooks in Taiwan, at least Textbook F and Textbook S, have not taken. 政 治 大 knowledge of speech acts to make students learn how to communicate more 立. speech act teaching so seriously, it is quite important for teachers to introduce the. effectively. Secondly, as an English teacher in Taiwan, increasing our knowledge of. ‧ 國. 學. speech act teaching becomes a ‘must’ since there are no or few explanations of. ‧. cross-cultural differences of speech acts and their supportive moves or small talk in. sit. y. Nat. the textbooks or teachers’ manuals. Thirdly, textbook publishers in Taiwan should. io. er. reflect upon the appropriate way to present the conversation part in textbooks to improve students’ sociolinguistic competence through speech act teaching. Last but. al. n. v i n not least, the coding schemeC used for analyzing theUpreference, American or Chinese hengchi. one, in this research, can not only be helpful to future researchers conducting similar studies on other sets of textbooks in Taiwan, but also offer teachers criteria to make judgments on the organization of the conversation part in textbooks and provide them the background knowledge of speech act teaching at the same time.. xi.

(12) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Motivation and Goal Communicative language teaching (CLT) has become a well-recognized approach in second language (L2) teaching substituting for the outdated Grammar Translation Method and/or Audiolingual Method. The principles and characteristics of. 政 治 大 English textbooks in Taiwan since 1995. According to the Senior High School English 立 Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) have been brought into senior high school. Curriculum Standards announced by the Ministry of Education in 1995, English. ‧ 國. 學. textbooks should be edited based on the Communicative Approach/Communicative. ‧. Language Teaching (CLT), in which communicative competence is emphasized as the. sit. y. Nat. goal of language learning.. io. er. In 2005, the Ministry of Education revised the previous Curriculum Standards and issued the Senior High School Required Subject English Curriculum Provisional. al. n. v i n Ch Outline. Although the term Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) was not engchi U directly stated in it, communicative competence was still the main focus. The. principles and characteristics of CLT are still required in editing Senior High School English textbooks, and many publishers claimed that they compiled their textbooks on the basis of Communicative Approach. According to Canale and Swain’s (1980) and Canale’s (1983) classic definition later, communicative competence consists of four components: grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence, and strategic competence. Among the four components, sociolinguistic competence deals with rules of speaking that depend on pragmatic and sociocultural elements. Cross-cultural 1.

(13) 2. studies (e.g., Blum-Kulka, House, and Kasper, 1989; Kasper and Dahl, 1991) have clearly shown that the lack of sociolinguistic competence for nonnative speakers might lead to misunderstandings or miscommunication (as cited in Yu, 2008). Empirical studies on speech acts play a vital role by serving as a means to define to what sociolinguistic competence actually refers. Second language learners need to be familiar with the social norms and values of the target language, which are realized in the use of speech acts, to achieve smooth communication with native speakers, instead of expressing themselves in an improper way. Therefore, it is. 政 治 大. important to carry out speech act teaching to enhance students’ sociolinguistic competence.. 立. Although there have been lots of studies conducted on speech acts, few of them. ‧ 國. 學. investigated the teaching of speech acts in textbooks, especially the textbooks used in. ‧. Taiwan. Among a handful of research, Lin (2004) analyzed the presentation of four. sit. y. Nat. speech acts in three sets of Senior High School English textbooks in Taiwan. However,. io. er. she did not point out clearly the cross-cultural differences between Americans and Chinese in the implementation of speech acts (Bergman and Kasper, 1993; Borkin. al. n. v i n and Reinhart, 1978; Chang, C 2003; Chen, H. J., 1996; h e n g c h i U Chen, R., 1993; Chen, S. C.,. 2007; Chen, Y. S., 2007; Fan, 2008; Hong, 2008; Hsu, 1953; Hu, 2004; King, 1993; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lee-Wong, 1994; Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, 1989; Liao and Bresnahan, 1994; Liao and Bresnahan, 1996; Mir, 1992; Oliver, 1971; Olshtain and Cohen, 1983; Pan, 2005; Shih, H. Y., 2006; Shu, 2004; Tanck, 2002; Te, 1995; Tsai, 2002; Wei, 2006; Wierzbicka, 1991; Wolfson, 1989; Yang, 1987; Ye, 1995; Yu, 1999; Yu, 2004; Yu, 2005; Zhang, 1995), and quickly came to a conclusion that American speakers’ preference was presented in those textbooks. Besides, whether cross-cultural comparisons and contrasts were made in textbooks were not analyzed. In addition, the supplementary information in teachers’ manuals was not.

(14) 3. included as a part of the investigation. The former three points constitute the missing information waiting to be further investigated. To probe deeper into the analysis of speech act presentation in English textbooks in Taiwan, there is a need for further research. Purpose of the Study Students’ sociolinguistic competence can be raised through speech act teaching. In speech act teaching, the much used and explored speech acts in our daily life should be presented in textbooks to enable students to perform them appropriately. 政 治 大 performance may vary cross-culturally, it is also important to inform EFL students of 立 when encountering them in real-life situations. Due to the reason that speech act. the cross-cultural differences between Americans and Chinese in English learning to. ‧ 國. 學. achieve smooth communication with native speakers. Furthermore, the teaching of. ‧. speech acts should be based on authentic and spontaneous speech in order to capture. sit. y. Nat. the underlying social strategies of each speech act behavior. Among authentic and. io. er. spontaneous speech act behaviors, supportive moves and small talk are often seen (Bergman and Kasper, 1993; Chang, 2003; Chen, S. C., 2007; Chen, Y. S., 2007;. al. n. v i n C1993; Hong, 2008; Hu, 2004; King, 1997; Liao and Bresnahan, 1996; Mir, 1992; U h e nLiao, i h gc Olshtain and Cohen, 1983; Pan, 2005; Shih, H. C., 2006; Shih, H. Y., 2006; Tanck, 2002; Trosborg, 1995; Wei, 2006; Yu, 1999; Yu, 2005; Zhang, 1995), and the realization of them differs cross-culturally as well. Therefore, investigating the phenomenon of supportive moves and small talk in textbooks becomes crucial to see whether they are really presented, and if so, whether they correspond to the usage of real-life situations. According to the above-mentioned rationale, the purpose of this thesis is threefold. First, this study aimed to point out the frequency of the much used and explored speech acts of compliment, request, apology, complaint, and refusal in two.

(15) 4. sets of the most popular senior high school English textbooks (The two textbooks were made anonymous by Textbook F and Textbook S respectively) in Taiwan. The second purpose of this study was to investigate the preference (American or Chinese) the two sets of textbooks showed in presenting speech acts and to determine whether cross-cultural comparisons and contrasts were made in the textbooks or their corresponding teachers’ manuals. The third purpose of this study was to survey whether supportive moves or small talk were presented in context, and if so, further explanations of their cultural differences between Americans and Chinese in the. 政 治 大 Significance of the Study. textbooks or their corresponding teachers’ manuals would be investigated.. 立. The investigator’s analysis on speech act instruction in the most popular two. ‧ 國. 學. sets of senior high school English textbooks in Taiwan (Textbook F and Textbook S). ‧. may in some way reflect the way speech act teaching is presented in Taiwan’s high. sit. y. Nat. school. The results of this study may help the Ministry of Education and high school. io. er. English teachers to reflect upon their teaching of sociolinguistic competence in Taiwan. Besides, suggestions may be offered to textbook publishers, enabling them to. al. n. v i n compile books with the goalC of improving sociolinguistic h e n g c h i U competence through speech act teaching. What’s more, the coding scheme used for analyzing the preference. (American or Chinese) Taiwan’s textbooks show in presenting speech acts can be helpful to future researchers conducting similar studies on other sets of textbooks in Taiwan. Organization of the Chapters The subsequent chapters are organized as follows. Chapter Two reviews communicative competence, sociolinguistic competence, speech act theory, cultural differences between American and Chinese speech acts, and studies of speech acts in ELT materials. Chapter Three describes the materials, procedure, and data analysis.

(16) 5. applied in this study. Chapter Four presents the results of the investigation, including the frequency tables. Also, in the same chapter, the discussion of the study is demonstrated under the tables, including the preference (American or Chinese) implemented, the occurrence of supportive moves and small talk, and the presentation of cross-cultural comparisons and contrasts. Lastly, Chapter Five lays out the conclusions containing summary, pedagogical implications, limitations and suggestions for future research.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(17) 7. CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW The following is the literature review in five main fields, including communicative competence, sociolinguistic competence, speech act theory, cultural differences between American and Chinese speech acts, and studies of speech acts in ELT materials. Based on the literature reviewed, the research questions and. 政 治 大 Communicative Competence. hypotheses of this study are presented at the end of this section.. 立. Communicative language Teaching (CLT) focuses on the widely discussed. ‧ 國. 學. notion of communicative competence. The scope of CLT has expanded since the. ‧. mid-1970s:. sit. y. Nat. Both American and British proponents have seen CLT as an approach (and not. io. er. a method) that aims to (a) make communicative competence the goal of language teaching and (b) develop procedures for the teaching of the four language skills that. al. n. v i n C h of language andUcommunication (Richards, J. and acknowledge the interdependence engchi Rodgers, T., 2001, p. 155).. Before the notion of CLT had expanded, grammatical competence and sociolinguistic competence were often viewed as two irrelevant competences; for example, Chomsky (1965) had advocated that competence was limited to the knowledge of grammar rules, while performance stood for the psychological factors that were involved in the perception and production of speech. In reaction to Chomsky’s dichotomy of competence and performance, Hymes (1972) as well as Campbell and Wales (1970) proposed the notion of communicative competence. They claimed that communicative competence included not only grammatical competence.

(18) 8. but contextual or sociolinguistic competence as well (as cited in Canale and Swain, 1980). With the idea of communicative competence receiving much attention, practical models of it came into existence later. The first practical model was offered by Canale and Swain in 1980, and was further revised by Canale in1983. In Canale’s (1983) model, communicative competence was made up of four components, and they were, grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence, and strategic competence. The mastery of the language code constituted grammatical. 政 治 大 different sociolinguistic contexts made up sociolinguistic competence. As to discourse 立 competence, while the appropriate performance and understanding of utterances in. competence, it was related to the ability to create unified spoken or written texts by. ‧ 國. 學. combining sentences. Lastly, strategic competence was the ability to employ. ‧. communication strategies to avoid communication breakdowns and therefore. Sociolinguistic Competence. er. io. sit. y. Nat. contributed to effective communication.. In Canale’s (1983) model of communicative competence, sociolinguistic. al. n. v i n C h elements. Sociolinguistic competence was one of the important competence deals engchi U with the appropriateness issue, that is, whether we can produce or understand. utterances appropriately in different sociolinguistic contexts. And sociolinguistic contexts are formed by different contextual factors, such as status of participants, purpose of interaction and so on (Canale, 1983). In other words, different contextual factors create different sociolinguistic contexts, and one who can communicate well with others no matter which sociolinguistic contexts he/she is in can be viewed as the person with a strong sociolinguistic competence. According to Canale (1983), “Appropriateness of utterances refers to both appropriateness of meaning and appropriateness of form” (p. 7). The difference between meaning and form is that.

(19) 9. meaning indicates the function of communication or one’s attitude and idea during the communication, and form is concerned with whether the utterance is in a verbal or non-verbal form (Canale, 1983). To suit specific sociolinguistic contexts, proper meaning and form of utterances should be carried out to promote successful communication. This, again, accounts for the appropriate issue of sociolinguistic competence. In short, the sociolinguistic competence in Canale’s (1983) model refers to the rules of speaking that depend on social, pragmatic, and cultural elements. And one. 政 治 大 acts, because speech acts are also affected by social, pragmatic, and cultural elements. 立 way to exhibit sociolinguistic competence is through the implementation of speech. That is to say, the realization of speech acts can show one’s sociolinguistic. ‧ 國. 學. competence, because it plays an important role in effective communication. ‧. (Baleghizadeh, 2007). The literature of speech acts is going to be reviewed in the. io. er. Speech Act Theory. sit. y. Nat. following section.. When it comes to speech acts, the classification and categorization of them. al. n. v i n C h“How to do thingsUwith words”, a famous book were the center of focus at first. engchi. written by J.L. Austin in 1962, was the book in which the term of speech act first appeared. Austin considered that in an utterance, there were three types of acts, and. they were: 1) locutionary act; 2) illocutionary act; 3) perlocutionary act. The literal meaning of an utterance formed a locutionary act, while the underlying meaning of the locutionary act composed an illocutionary act. As to a perlocutionary act, it was the effect brought about by the illocutionary act on the hearer. A few years later in 1969, a philosopher named Searle refined Austin’s (1962) concept and published a book called “Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language”. Speech acts were classified into five categories by Searle later in 1979,.

(20) 10. and they were: 1) commissive acts: utterances that commit oneself to doing something in the future, for example, promises or threats; 2) declarative acts: declarative utterances that change the state of affairs in the world, for instance, the phrase I now pronounce you man and wife during a wedding ceremony; 3) directive acts: utterances that carry the function of directing someone to do something, such as requests or commands; 4) expressive acts: the expressions of one’s feelings and attitudes toward someone or something, such as apologies or thanks; 5) representative acts: utterances representing one’s opinions toward states or events in life, for example, assertions or. 政 治 大 After Austin (1962) and Searle’s (1969) pioneering work, the study of speech 立. claims.. acts has turned from merely making classifications of them into investigating their. ‧ 國. 學. presentation sequences and their following responses. Speaking of sequences and. ‧. responses of speech acts, the issue of universality versus culture-specificity has. sit. y. Nat. continuously been of great concern. The results of these empirical studies have been. io. er. successfully applied in language teaching, causing material designers and language instructors to benefit a lot at the same time (Nunan, 1999).. al. n. v i n Universality C Versus Cultural-Specificity h e n g c h i U of Speech Acts. Just as what has been mentioned before, the issue of universality versus culture-specificity of speech acts has been of great interest in speech act study in recent decades. For example, in order to find out whether universal traits existed in speech act realization or not, Blum-Kulka, House, and Kasper (1989) conducted an ambitious study— the Cross Cultural Speech Act Realization Project— on three dialects of English and five other languages. In this study, they found some universal as well as cultural-specific points across speech act usage. Nevertheless, all the languages being investigated in this research were either Western or strongly affected by the Western cultures; therefore, generalizations of the results from this study.

(21) 11. cannot be made. Until now, the concept of universality or cultural-specificity of speech acts is still debated intensely (Yu, 2005). As to the studying of American and Chinese speech acts (Bergman and Kasper, 1993; Borkin and Reinhart, 1978; Chang, 2003; Chen, H. J., 1996; Chen, R., 1993; Chen, S. C., 2007; Chen, Y. S., 2007; Fan, 2008; Hong, 2008; Hsu, 1953; Hu, 2004; King, 1993; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lee-Wong, 1994; Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, 1989; Liao and Bresnahan, 1994; Liao and Bresnahan, 1996; Mir, 1992; Oliver, 1971; Olshtain and Cohen, 1983; Pan, 2005; Shih, H. Y., 2006; Shu, 2004; Tanck, 2002; Te, 1995; Tsai, 2002; Wei, 2006;. 政 治 大 2005; Zhang, 1995), however, there was already a lot of evidence showing that 立. Wierzbicka, 1991; Wolfson, 1989; Yang, 1987; Ye, 1995; Yu, 1999; Yu, 2004; Yu,. cultural differences did exist. Those differences will be reviewed later in this chapter,. ‧ 國. 學. while now, another important factor that is usually drawn out for discussion when. ‧. studying speech acts is going to be explored in the following first, and that important. io. er. Context. sit. y. Nat. factor is called— context.. In speech act teaching, context factor influences the presentation of speech acts. al. n. v i n C hlead to different displays because different contexts may of speech acts. Literal engchi U. meanings of conversations cannot be completely interpreted without the providing of context factors. The definition of context was revealed in Hymes’ (1979) research, in which he maintained eight elements of context information, and they were, settings, participants, ends, act sequence, key, instrumentalities, norms of interaction and interpretation, and genre. Holmes (2001), in contrast, proposed a simpler preference on context by including just social factors and social dimensions in it. The social factors in Holmes’ proposal were made up of participants, setting, and topic of a conversation, whereas social dimensions consisted of the four scales of distance, status, formality, and.

(22) 12. function. To speak more specifically, context was composed of the participants involved in the talk, the topic of the conversation, and the setting of the interaction, and the four scales of social dimensions affected the choice of certain utterances of speech acts (Holmes, 2001). The lack of context information could cause problems to language learners. For instance, Kramsch (1993) pointed out that the specific meaning of a sentence relied on the contextual condition in which the sentence occurred, and confusions for language learners would appear if they did not take contextual factors into consideration in the. 政 治 大 forms were selected to fit certain particular contexts, if language learners did not pay 立 first place. For another instance, Kramsch (1993) indicated that different linguistic. attention to context information, they might employ improper language forms and. ‧ 國. 學. therefore be unable to communicate with others effectively.. ‧. The building of context information in conversations can be realized through. sit. y. Nat. the supply of supportive moves and small talk. In authentic and spontaneous speech,. io. er. utterances are often accompanied with supportive moves and small talk (Bergman and Kasper, 1993; Chang, 2003; Chen, S. C., 2007; Chen, Y. S., 2007; Hong, 2008; Hu,. al. n. v i n C hLiao and Bresnahan,U1996; Mir, 1992; Olshtain and 2004; King, 1993; Liao, 1997; engchi. Cohen, 1983; Pan, 2005; Shih, H. C., 2006; Shih, H. Y., 2006; Tanck, 2002; Trosborg, 1995; Wei, 2006; Yu, 1999; Yu, 2005; Zhang, 1995), and they add to the hearer the understanding of contexts. Therefore, if conversations are presented by merely one turn with no supportive moves or small talk, misunderstandings might arise for lack of sufficient context information. Having the same phenomenon as speech acts, there are cross-cultural differences in the presentation of supportive moves and small talk (Bergman and Kasper, 1993; Chen, S. C.,2007; Chen, Y. S., 2007; Chang, 2003; Fan, 2007; Hong, 2008; Hu, 2004; King, 1993; Liao, 1997; Liao and Bresnahen, 1996; Mir, 1992; Olshtain and Cohen, 1983; Pan, 2005; Shih, H. C., 2006; Shih, H. Y., 2006;.

(23) 13. Tanck, 2002; Trosborg, 1995; Wei, 2006; Yu, 1999; Yu, 2005; Zhang, 1995), and those differences will be stated later in this chapter as well. Cultural Differences Between American and Chinese Speech Acts That cultural differences between American and Chinese speech acts do exist has been stated earlier in this chapter. At present, we are going to probe into these differences through literature review. The following are some of the cultural differences being found in speech acts when reviewing the literature. Compliment. 政 治 大 the speaker and hearer (Holmes, 1988). Compliment is a speech act which directly or 立 Speaking of compliments, it serves the function of creating solidarity between. indirectly credits the addressee for some good traits, possessions, skills and so on. ‧ 國. 學. (Holmes, 1986). For Chinese speakers, the variations of the use of compliment act. ‧. from the English speakers do exist, and are clarified as follows.. sit. y. Nat. Compliment Strategies. io. er. As for compliment strategies, they are often classified in terms of the directness level by researchers (e.g., Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984;. al. n. v i n Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk,C 1989; Ye, 1995; Yu, U h e n g c h i 1999; Yu, 2005). Thus, strategies. for paying compliments applied in this study were based on the directness level. There were two distinguishing strategies for paying compliments employed in this study, and they were listed as follows: 1. Direct Compliments: referring to compliments with direct linguistic forms, for instance: (1) ‘Cool! That’s a nice photo of you.’ (2) ‘Michael, you’re good at this.’ (3) ‘That’s a very creative idea!’ 2.. Indirect Compliments: referring to compliments with unobvious or ambiguous.

(24) 14. linguistic forms, for example: (1) ‘Wow! That dress certainly did the trick.’ (2) ‘I’m sure you can get into any university you choose.’ (3) ‘I must admit they made the right choice in choosing Sharon.’ Previous research (Herbert, 1989; Oliver, 1971; Wolfson, 1989; Yu, 2005) has shown that complimenting frequency would be much lower for Chinese speakers than for English speakers. However, for both speaker groups, direct complimenting was still the most often adopted strategy in the compliment act (Yu, 2005).. 政 治 大 Studies have shown that most of the compliments fall into two main categories 立. Compliment Topics. of topic: 1) appearance and/or possessions; 2) ability and/or performance (Knapp,. ‧ 國. 學. Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lin, 2008; Manes, 1983; Wolfson, 1989; Yu, 2005). These. ‧. two main categories of compliment topic are illustrated as follows.. sit. y. Nat. 1. Appearance and/or Possessions: for instance,. io. 2. Ability and/or Performance: for instance,. n. al. er. ‘You have such a beautiful smile.’. C ath making a speech.’U n i ‘Susan, you’re really good engchi. v. According to previous studies, Chinese speakers tended to compliment proportionately more on ability and/or performance than English speakers (Lin, 2008; Yang, 1987; Yu, 2005), whereas English speakers proportionately more on appearance and/or possessions than Chinese speakers (Holmes, 1986, 1988; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lin, 2008; Wolfson, 1989; Yu, 2005). Some causes could be found in the literature to account for the Chinese speakers’ inclination to compliment on ability and/or performance. According to Yang (1987), virtues and abilities of people were highly valued in the Chinese society; comparatively, good looks and possessions of individuals were not as important. This.

(25) 15. was one of the reasons why the Chinese preferred compliment topics of ability and/or performance to appearance and/or possessions. Besides, Ye (1995) argued that implicitness was one traditional trait of the Chinese people; as a result, explicitly complimenting on others’ appearance and/or possessions would be thought of as uncultivated; moreover, directly admiring a person’s appearance and/or possessions might also have a sexual implication in the Chinese culture, and therefore was mostly avoided in society (Hsu, 1953, as cited in Yu, 2005). These reasons again explain why the Chinese have a preference for complimenting on ability and/or performance to. 政 治 大 On the other hand, the reasons why English speakers have an inclination to 立. appearance and/or possessions.. compliment on appearance and/or possessions could also be proved from literature.. ‧ 國. 學. Based on Wolfson’s (1989) research, in the American society, it was common to pay. ‧. compliments to others with something new, since newness is valued highly there. In. sit. y. Nat. addition, as aforementioned, the main function of compliments for the English. io. er. speakers is to create solidarity between the speaker and addressee (Holmes, 1988); consequently, complimenting on others’ appearance and/or possessions would be a. n. al. way to achieve the purpose. Compliment Responses. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. For compliment response behavior, studies have also revealed that there are cultural differences between native Chinese and English speakers. Combining these studies, there is an overall tendency showing that the Americans are inclined to accept the compliments while the Chinese are inclined to reject them (Chen, 1993; Herbert, 1989; Holmes, 1988; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lin, 2008; Ye, 1995; Yu, 2004). In 1993, Chen reported that the American English speakers' response strategies were mostly influenced by Leech's Agreement Maxim, whereas the Chinese speakers' strategies by Leech’s Modesty Maxim, that is to say, the Chinese are of the opinion.

(26) 16. that being humble is the best reaction to a compliment. Although the Americans have the tendency to accept and the Chinese to reject the compliments, what compliment response strategies the two speaker groups prefer is still indefinite due to the diverse research results which have been shown until now (e.g., Chen, 1993; Herbert, 1989; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lin, 2008; Ye, 1995; Yu, 2004). Some studies revealed that the Chinese preferred non-acceptance strategies (e.g., Chen, 1993; Lin, 2008; Yu, 2004), while others reported that they preferred amendment strategies (e.g., Ye, 1995). As to investigations concerning. 政 治 大 Americans preferred acceptance strategies (e.g., Chen, 1993; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 立 Americans’ compliment response strategies, some research results showed that the. strategies (e.g., Herbert, 1989).. 學. ‧ 國. 1984; Lin, 2008; Yu, 2004), whereas others argued that they preferred amendment. ‧. In 2004, Yu figured out six mutually exclusive strategies of compliment. sit. y. Nat. response based on previous literature (Herbert, 1989; Pomerantz, 1978; Wolfson,. io. er. 1989), and they were: 1) acceptance strategies, 2) amendment strategies, 3) non-acceptance strategies, 4) face relationship related response strategies, 5). al. n. v i n combination strategies, and C 6) no acknowledgement, h e n g c h i U among which acceptance. strategies, amendment strategies and non-acceptance strategies were especially drawn out for analysis in this study, because of their differing cross-cultural preferences among American and Chinese people in previous literature (e.g., Chen, 1993; Herbert, 1989; Holmes, 1988; Knapp, Hopper, and Bell, 1984; Lin, 2008; Ye, 1995; Yu, 2004). What needs to be mentioned here is that in this study, amendment strategies were categorized under the Chinese preference in line with Ye’s (1995) study, for the researcher believes that the characteristics of humbleness and modesty in Chinese people (Chen, 1993) may lead to this kind of result. The following are the three strategies picked out for analysis in this research..

(27) 17. 1. Acceptance strategies: Utterances that take the preceding remark as a compliment, such as ‘Thank you!’, or ‘Yeah, I think the report was well-done, too’. 2. Amendment strategies: Utterances that try to lighten the complimentary force by including amending statements, such as ‘Your dress is also very beautiful’, or ‘I worked pretty hard last night’. 3. Non-acceptance strategies: Utterances that deny or joke about the compliment, such as ‘No’, ‘Well, actually I think it sort of out of date’, or ‘Stop embarrassing me’. Request 政 治 大 According to previous research (Canale, 1983; Canale and Swain, 1980), 立. speech acts could be majorly classified into two categories: direct speech acts and. ‧ 國. 學. indirect speech acts, and the request acts are no exception. Speaking of requests, the. ‧. direct ones are explicit and easy to understand; however, the most frequently-used. sit. y. Nat. requests in native American English are indirect ones (Lycan, 1984; Wierzbicka, 1991;. io. er. Yu, 1999). Indirect requests are sometimes implicit and hard to understand for native speakers, not to mention non-native speakers of English. Consequently, interpreting a. al. n. v i n C h to it appropriatelyUbecomes an essential part in speaker’s request and responding engchi. second language learning and teaching. Some cultural differences between Americans and Chinese in the implementation of request strategies and request responses are shown in the following. Request Strategies According to previous literature (Canale, 1983; Canale & Swain, 1980), two broad, mutually exclusive strategies for offering requests were applied in this study: 1. Direct requests: Linguistic forms for direct requests such as I request you…or I want you…, and linguistic forms for indirect request such as Will you… and Can you… were proposed by Gordon and Lakoff (1980). However, their theories were.

(28) 18. too broad and vague, and were further revised by Lycan (1984). 2. Indirect requests: Later in 1984, Lycan brought up the concept of conventional/idiomatic and non-conventional uses of indirect request acts. Conventional/idiomatic indirect requests were expressions such as Can you… Could you… and Would you…, whereas non-conventional indirect requests included sentence patterns like Do you… or I wonder… Conventional/idiomatic indirect requests were often heard in daily life, and thus served as a buffer in communication due to its polite property; by contrast, non-conventional indirect. 政 治 大 the vagueness of language use. In this situation, the underlying meanings of 立. requests were far from convention and full of variety in form, and therefore added. non-conventional indirect requests can only be figured out through the context or. ‧ 國. 學. the speaker’s idiosyncrasy, which makes it difficult for hearers to handle the. sit. y. Nat. than conventional/idiomatic indirect requests.. ‧. discourse. As a result, non-conventional indirect requests are deemed less polite. io. er. According to previous research (Lee-Wong, 1994; Oliver, 1971; Yu, 1999; Zhang, 1995), the Chinese tend to employ direct language forms in their request acts.. al. n. v i n Cforms However, the direct language in Chinese requests express politeness rather than U hen i h gc rudeness. This notion could be illustrated in Zhang’s (1995) study, showing that. requestive verbs such as ken-qing (懇請) and qing-qui (請求) were often used to show humbleness, and assertive verb like yao-qiu (要求) were often applied in the hope of making the hearer to comply in Chinese requests. The reason for showing humbleness and subordination to others in the request acts of Chinese people was clarified in previous investigations (Lee-Wong, 1994; Oliver, 1971), showing that respect and subordination to authorities were highly emphasized in the Chinese culture due to feudal hierarchy resulting from Confucian philosophy. Besides the matter of respect, subordination, and communal needs, Lee-Wong (1994) also.

(29) 19. claimed that the inclination of applying direct request strategies of the Chinese people might be caused by the tradition of sincerity and clarity in speech. As to native English speakers, they are liable to use CID (Conventional Indirect) and NCID (Non-conventional Indirect) to decrease the threat or force of requests. This kind of speech act performance mostly relates to their stress on individualism, which places emphasis on the rights and privacy of each individual, and abhors interfering in other people’s business (Wierzbicka, 1991). From the above, we can see that native Chinese speakers’ request behavior and. 政 治 大 as well as the concept toward politeness play a crucial role at this point. 立. its underlying belief is very different from that of native English speakers, and culture. Request Responses. ‧ 國. 學. From previous literature (Chang, 2003; Lee-Wong, 1994; Oliver, 1971; Yu,. ‧. 1999; Zhang, 1995), Chinese speakers preferred direct requests to indirect ones.. sit. y. Nat. Direct requests in Chinese discourse pattern seem like orders given to the addressee. io. er. (Gordon & Lakoff , 1980; Lee-Wong, 1994; Oliver, 1971; Yu, 1999; Zhang, 1995), and therefore, Chinese people tend to only respond with the required action or needed. al. n. v i n C hor no, because the U information without saying yes request itself is not in an engchi. interrogative but an imperative form. On the contrary, Americans view direct requests less polite than indirect ones, so they are prone to use indirect requests (Wierzbicka, 1991), which are usually presented in an interrogative form (Lycan, 1984), and responded with yes or no plus the required information or action. From the above, we can see that responses to requests also present significant cultural differences among Chinese speakers and English speakers. Combining the literature reviewed (Chang, 2003; Clark, 1979; Fan, 2008), there were four main mutually exclusive strategies for request responses, and they were: 1) Yes/No Alone, 2) Yes/No + Information/Action, 3) Information/Action Alone, and 4) Others. The result.

(30) 20. of Fan’s (2008) study showed that both EFL and native Chinese participants’ strategies presented an Information/Action Alone>Yes/No + Information/Action> Others>Yes/No Alone pattern, while native Americans showed a Yes/No + Information/Action>Information/Action Alone>Yes/No Alone>Others pattern. This result echoed Chang’s (2003) findings, which suggested that English native speakers preferred Yes/No + Information/Action in both CID and NCID while EFL participants tended to employ Information/Action Alone the most. What is worth mentioning is that when encountering NCID, EFL participants. 政 治 大 NCID requests are not like CID ones, which are introduced continuously in the EFL 立 could only try to decode the literal meaning from the sentences to give responses.. learners’ textbooks; as a result, students might use Others as their responses to NCID. ‧ 國. 學. requests due to their unfamiliarity and deficiency of NCID requests. This could. io. er. Apology. sit. y. Nat. participants’ strategies in Fan’s (2008) study.. ‧. account for the third place Others ranked in both EFL and native Chinese. The broad definition of an apology can be summarized as a speech act whose. al. n. v i n C hfrom the apologizer function is to remedy an offense and meet the hearer’s face-needs, engchi U restoring equilibrium between the apologizer and the person being offended (Holmes, 1989). Apology can be viewed as a face-threatening speech act, and Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1984) explained the reason as follows. By apologizing, the speaker recognizes the fact that a violation of a social norm has been committed and admits to the fact that s/he is at least partially involved in its cause. Hence, by their very nature, apologies involve loss of face for the speaker and support for the hearer … (p.206) As to the strategies of apology, the similarities and differences between non-native speakers (L2 learners) and native speakers of English are presented in the following..

(31) 21. Apology Strategies Three main categories of apology strategies were proposed by Olshtain and Cohen (1983), and later applied by Shih, H. Y. (2006) as the coding scheme of her study. These three strategies were: 1) strategy of opting out, 2) strategies of apologies, and 3) strategies of offering remedial support. Among the three categories, strategy of opting out meant that the speaker deny the need for an apology, while strategies of apologies were composed of evasive strategy, acknowledging responsibility, providing explanation or account, and direct expression of apology. As for strategies. 政 治 大 offering promise of forbearance, and offering repair or compensation. Shih, H. Y. 立 of offering remedial support, they comprised expressing concern for the hearer,. found out that the frequency and number of apology strategies used by native. ‧ 國. 學. speakers of English (Americans) were higher than those by native speakers of Chinese,. sit. y. Nat. native speakers of Chinese did.. ‧. which implied that native speakers of English (Americans) apologized more than. io. er. Based on the three main categories of apology strategies noted above, several researchers (Bergman & Kasper, 1993; Hu, 2004; Mir, 1992; Shih, H. Y., 2006) have. al. n. v i n C hboth native speakers claimed that when apologizing, of English (Americans) and engchi U. native speakers of Chinese preferred giving the following four strategies more often than other strategies: 1. Direct expression of apology (Direct apology): Taking the form of an expression of regret, an offer of apology, a request for forgiveness, or a repetition of direct expression of apology itself. (1) Request for forgiveness: native speakers of English (Americans) tended to express it in an imperative form, while native speakers of Chinese tended to express it in an interrogative form (Shih, H. Y., 2006). (2) Repetition of direct expression of apology: This form was mostly found in.

(32) 22. native speakers of Chinese responses (Shih, H. Y., 2006). 2. Acknowledging responsibility (Indirect apology): Including the subcategories of implicit acknowledgement, explicit acknowledgement, expression of lack of intent, expression of self-deficiency, expression of embarrassment, and explicit acceptance of the blame. 3. Offering repair or compensation (Indirect apology): Consisting of implicit and explicit repair or compensation. EFL learners might apply the strategy of offering repair or compensation less than native speakers of English (Americans) due to. 政 治 大 might employ the evasive strategy of paying compliment and the remedial 立. language proficiency problems or sociopragmatic reasons. At times, EFL learners. strategy of offering promise of forbearance instead of the remedial strategy of. ‧ 國. 學. offering repair or compensation because of those problems or reasons (Shih, H. Y.,. ‧. 2006).. io. er. implicit explanation and explicit explanation.. sit. y. Nat. 4. Providing explanation or account (Indirect apology): Including subcategories of. One interesting phenomenon revealed by previous literature about the. al. n. v i n C hwas that familiarity above-mentioned four strategies between interlocutors played an engchi U important role in the implementation of some strategies (Bergman & Kasper, 1993; Hu, 2004; Mir, 1992). For example, the tendency of applying the strategy of explanation toward an unfamiliar interlocutor could be found both in American and Chinese apology (Hu, 2004; Mir, 1992). For the native speakers of American English, the closer the relationship between interlocutors, the more likely the apologizer would express responsibility; conversely, the farther the relationship between interlocutors, the less likely the apologizer would admit responsibility (Bergman & Kasper, 1993; Mir, 1992). In addition to the issue of familiarity, other noticeable findings about apology.

(33) 23. act were also discovered. In 2002, Tsai demonstrated that in Chinese apology, the greater the ranking of imposition or the more the power that the hearer had, the more formal and elaborate combinations of Chinese apology strategies would be made use of. It was also indicated that single apologetic formula tended to be utilized toward strangers, informal apology strategies adopted toward intimates, and formal as well as elaborate combinations of apology strategies used toward friends in Chinese apology. Later in 2006, Shih, H. C. found out that native English speakers were inclined to adopt the explanation or account strategy more frequently in the situations with. 政 治 大 instead of just saying sorry or making apologies to express how awful or 立. greater ranking imposition where they,. horrible they felt and how regretful they were, would like the offended person. ‧ 國. 學. to realize that the real cause to the results (broken digital camera) and then. ‧. followed by offering some repair to compensate for the offense. (p. 162). sit. y. Nat. She concluded that native English speakers adopted more combinations of different. io. Excuse Me and I’m Sorry. al. er. apology strategies in each situation than EFL junior high school students did.. n. v i n C h mentioned above, Besides the apology strategies the differences in formulas of engchi U. direct apology between both English and Chinese need paying attention to as well. The result of Shih, H. Y.’s (2006) study showed that the two formulas of direct. apology expressions most frequently used in English were I’m sorry and excuse me, which corresponds with the result of Borkin and Reinhart’s (1978) study. On the other hand, three kinds of direct apology expressions most frequently applied in Chinese were duibuqi 對不起, baoqian 抱歉, and buhaoyisi 不好意思. In English, excuse me is limited to be used as a remedy while I’m sorry can be used as both a remedy and an expression of showing regret (Borkin & Reinhart, 1978). Comparatively, in Chinese, ‘severity of offense’ influences the choice of apology.

(34) 24. expressions duibuqi 對不起, baoqian 抱歉, or buhaoyisi 不好意思. To speak more specifically, duibuqi 對不起 and baoqian 抱歉 were used more frequently in higher offense severity situations, while buhaoyisi 不好意思 in lower offense severity situations. Owing to the above differences between English and Chinese formulas of direct apology, we can see that there is no equivalent translation from Chinese into English, which makes it harder for EFL learners to carry out the correct form of direct apologies in English in different situations. The following study conducted by Borkin and Reinhart (1978) on excuse me and I’m sorry might help. 政 治 大 At the English Language Institute of the University of Michigan, Borkin and 立. non-native speakers of English to grasp the idea of those two formulas.. Reinhart (1978) have observed inappropriate uses of the two formulae, excuse me and. ‧ 國. 學. I’m sorry, among non-native speakers of English. Two of the examples which Borkin. ‧. and Reinhart provided in their study are as follows:. sit. y. Nat. 1. Excuse me. I’d like to go but I don’t have time─elicited from a non-native. io. er. speaker as a refusal to an invitation to the movies, which might actually give offense unless excuse me were replaced by I’m sorry.. al. n. v i n I’m sorry, but it is time to Cfinish.─used U reminder to a teacher that h e n g cashai student’s. 2.. class time is up, which the use of I’m sorry rather than excuse me would be somewhat overbearing.. According to Borkin and Reinhart’s (1978) generalization, the differences in the appropriate conditions for the two formulae— excuse me and I’m sorry— were as follows. First, excuse me often occurred before or after an infraction, whereas I’m sorry often appeared after an infraction. Secondly, excuse me was limited to be used as a remedy, implying that a social rule had been broken or was about to be broken, whereas I’m sorry was basically an expression of regret about an unfortunate affair that had already happened. Thirdly, excuse me was utilized to show that the speaker’s.

(35) 25. main concern was about a rule violation on his or her part, whereas I’m sorry was used when the speaker’s main concern was about a violation of another person’s rights or damage to another person’s feelings, reflecting the speaker’s relation to another person. Although non-native speakers may understand that excuse me is appropriate when a minor social rule has been broken or is about to be broken, they may not know what constitutes a social violation in the American society. This potential difficulty of using excuse me properly is culturally-related (Borkin & Reinhart, 1978). At this time,. 政 治 大 Complaint. giving students related cultural information would be suitable in an EFL classroom.. 立. Complaints are a type of speech act that expresses the speaker’s disappointment. ‧ 國. 學. or grievance. Edmondson-House (1981) pointed out that in making a complaint, “a. ‧. speaker potentially disputes, challenges, or bluntly denies the social competence of. sit. y. Nat. the complainee” (p. 145). Complaints are not easy to handle, even for native speakers. io. er. because of their potentially face-threatening nature. According to Hong (2008), complaints were usually accompanied by explicit or implicit directives to require the. al. n. v i n complainee to do somethingC to compensate for theU h e n g c h i complained behavior. “The. directive act may appear in the form of a request, an order, or a threat. It offers the complainee an opportunity to repair the damage s/he has caused and attempts to prevent a repetition of the deplorable act” (p.3). There are two distinct lines of research on the act of complaining. The first line of research investigates the complaint to an interlocutor who is not present, whereas the second line investigates the complaint to the hearer on the scene. The present study focused on the second line, that is, the complaint to the hearer who is present. After reviewing the literature, several cultural differences between American and Chinese usage of the complaint act were discovered and presented as follows..

(36) 26. Complaint Strategies Wei (2006) categorized the complaint act into three main parts according to previous literature (Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, 1984; Trosborg, 1995; Murphy & Neu, 1996), and they were, modification, head act, and solution. Later in 2008, Hong proposed six strategies of complaints with the directness level increasing from the first to the last, and they were, opting out, hint, disapproval, request, explicit complaint, and accusation, among which opting out, hint, disapproval, and explicit complaint could be viewed as the head act of complaint, and request as well as. 政 治 大 (2008) studies were combined to form the categorization of complaint act in this 立. accusation could be regarded as the solution of complaint. Wei’s (2006) and Hong’s. research due to their strong literature background based on previous investigations.. ‧ 國. 學. Cultural differences between American and Chinese usage can be found in the. ‧. realization of the three main complaint strategies applied in this study and are. sit. y. Nat. explained in the following.. io. er. 1. Modification: Modification often appears in the form of an opening or an explanation of purpose, having the function of strengthening or weakening the. al. n. v i n C hpresented that native language force. Shu (2004) English speakers usually used engchi U. openings such as ‘I’ve a dumb question…’, ‘Excuse me’, ‘Sorry to bother you…’ to start a complaint, followed by some requests for repair toward the complained situation (as cited in Wei, 2006). 2. Head act: As for the head act, it is the core act of complaint, which shows the annoyance or negative feelings of the complainer. According to Hong (2008), among the six strategies of complaints, opting out, hint, disapproval, and explicit complaint could be viewed as the head act of complaint. They are further illustrated as follows. (1) Opting out: The subjects do not want to complain..

(37) 27. (2) Hint: The complained behavior (CB) is not mentioned in the utterance. For example, ‘My notebook was clean the last time I read it’ (Trosborg, 1995). (3) Expression of annoyance or disapproval: In this category, the complainer (C1) expresses her/his thoughts concerning the responsibility of the complainee (C2) but avoids mentioning it directly. Although neither the complained behavior (CB) nor C2 is straightforwardly mentioned, the complainer has declared clearly that a violation has occurred. This category includes two sub-strategies: expression of annoyance and expression of ill consequences. For instance, the. 政 治 大 the sentence ‘There is a dirty mark on my notebook’ is an expression of ill 立. sentence ‘I hate to be disturbed in class’ is an expression of annoyance, while. consequences (Trosborg, 1995).. ‧ 國. 學. (4) Explicit complaint: C1 explicitly expresses her/his complaint by referring to. ‧. either CB or C2, or both. However, no punishments or sanctions are included.. io. er. 1987, as cited in Olshtain & Weinbach, 1993).. sit. y. Nat. For example, ‘You can’t make so much noise at night’ (Olshtain & Weinbach,. 3. Solution: Speaking of solution, it usually appears in the form of directive acts and. al. n. v i n serves as the supportive C move to the complaint.UIts aim is to improve the offensive hengchi. situation or prevent the offense from happening again. Generally speaking,. directive acts such as request for repair or forbearance as well as accusation and threat can be regarded as solutions in the complaint act (Hong, 2008). (1) Request for repair or forbearance: The request for repair means the offense is reversible; for instance, ‘Could you please return my book as soon as possible?’ The request for forbearance is made in the hope that the offensive behavior will never happen again; for example, ‘Can you please never take my things without asking again’ (Chen, Y. S., 2007; Hong, 2008; Trosborg, 1995). The strategy of request includes two sub-strategies: indirect request and direct.

(38) 28. request, which were mentioned earlier in the literature review of the request act in the present study. (2) Accusation and threat: The strategy of accusation comprises two sub-strategies: indirect accusation and direct accusation. If C1 employs indirect accusation, s/he says something to connect C2 and CB; for example, ‘You borrowed my notebook last night, didn’t you?’ However, if C1 chooses direct accusation, s/he explicitly accuses C2 of having made the offense; for instance, ‘Did you stain my notebook’ (Trosborg, 1995). On the other hand, a threat is. 政 治 大 notebook, I will tell the teacher’ (Trosborg, 1995). 立. an open attack on the complainee; for instance, ‘If you don’t give me my. There are some cultural differences among American and Chinese application. ‧ 國. 學. of complaint strategies. First of all, among the strategies mentioned above, both native. ‧. Chinese groups and native English groups employed requests, especially the indirect. sit. y. Nat. ones, more often than any other strategies (Chen, Y. S., 2007; Hong, 2008). Secondly,. io. er. native Chinese speakers used high directness level of explicit complaints and accusations with high frequency (Hong, 2008). The native Chinese speakers’ severity. al. n. v i n in performing the complaintC act could be explainedUby the factor of changing society, hengchi caused by Western individualism (Hong, 2008). On the other hand, the native. American speakers were more inclined to employ lower severity level of complaints such as hints and opting out, and most of the Americans tended to combine two strategies to respond to a complaint situation (Hong, 2008). Thirdly, for both native Chinese and Americans, the farther the social distance between interlocutors, the less direct the complaint strategy would be employed, and vice versa (Hong, 2008; Wei, 2006). For instance, both native Chinese and Americans used disapproval and opting out more often toward superiors, whereas utilized explicit complaints or accusations more frequently toward status equals. For another instance, both native Chinese and.

(39) 29. Americans tended to use hints and opting out toward strangers, while apply other severer complaint strategies toward siblings or neighbors (Hong, 2008; Wei, 2006). Complaint Responses One characteristic of a complaint is that it has no typical corresponding responses because it may be followed by any complaint response strategies. The type of response strategy selected to be employed in a complaint act depends upon the degree of responsibility the complainee takes (Chen, Y. S., 2007). Refusal. 政 治 大 a request, invitation, or suggestion. Refusal is a face-threatening act to the person who 立 The speech act of refusal occurs when a speaker directly or indirectly says no to. is refused because it contradicts his or her expectations, and is often realized through. ‧ 國. 學. indirect strategies, such as providing reasons or excuses (Chen, H. J., 1996). There are. Refusal Strategies. io. er. sit. y. Nat. usage and are illustrated as follows.. ‧. some cultural differences for refusal strategies among American and Chinese people. When it comes to refusal strategies, direct refusal (i.e., ‘No’) was not a common. al. n. v i n strategy for either AmericanC or Chinese subjects regardless of their language hengchi U. background (Chen, H. J., 1996; Chen, S. C., 2007; Pan, 2005). Indirect refusals were the most frequently used main strategy type in both native speakers of American English and native Chinese speakers. Nevertheless, the American group preferred more direct refusal strategies than the EFL and Chinese groups (Chen, S. C., 2007; Pan, 2005). Referring to the coding scheme applied in Chen’s (2007) and Pan’s (2005) study, the categorization of direct and indirect refusal strategies applied in this study is shown in the following. 1. Direct refusals: Responses that deny the requester directly. It may be a performative (e.g. ‘I refuse’), or a nonperformative (e.g. a direct ‘No’, a sentence.

(40) 30. showing negative willingness/ability such as ‘I can’t’, or an expression showing insistence, for example, ‘I still don’t want to make a change’). 2. Indirect refusals: Responses that decline the requester indirectly. There are four main substrategies of indirect refusals, which are, 1) Regret (e.g. ‘I am sorry. I cannot go.’), 2) Excuse, reason, and explanation (e.g. ‘I already have an appointment with my friends.’), 3) Alternative (e.g. ‘Can we go there some other day?’), and 4) Combination (e.g. Regret + Excuse, reason, and explanation, such as ‘Sorry. I don’t have enough money to lend you.’). 治 政 大 the substrategies─ regret, According to King (1993) and Pan (2005), among 立. Combination: Native-like Refusal. explanation, alternative, combination, and others─ of indirect refusal, the Chinese. ‧ 國. 學. EFL group evidently offered much more verbose or unnecessary expressions of regret. ‧. such as I am sorry than the native American group. The above phenomenon might be. sit. y. Nat. caused by a lack of sufficient pragmatic knowledge of the EFL group.. io. er. As to the explanation substrategy, there were three characteristics of it among both EFL and NC groups, and they were: 1) Mentioning a third party as the reason for. al. n. v i n C h 1996; Pan, 2005),U2) Employing a fictitious reason the rejection (Liao & Bresnahan, engchi for the rejection (Pan, 2005), and 3) Applying the principle of modesty or. self-denigration for the rejection (Pan, 2005). The first characteristic showed that Chinese refused not by self-expressive explanatory utterances, but by sticking to one extrinsic reason. As to the third characteristic, in fact, modesty and self-denigration in Chinese culture are not symbols of weakness, instead, they are “not only face-balancing strategies that attempt to add positive feelings in the recipient by means of abasing oneself to elevate the other, but also interactional skills that aim at softening the tone and weakening the effect of rejections” (Pan, 2005, p. 67). By contrast, the explanation substrategy in the native American group was found to be.

數據

相關文件

Consistent with the negative price of systematic volatility risk found by the option pricing studies, we see lower average raw returns, CAPM alphas, and FF-3 alphas with higher

In the fourth quarter of 2003, 4 709 acts of deed were notarized on sales and purchases of real estate and mortgage credits, representing a variation of +19.6% in comparison with

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

experiences in choral speaking, and to see a short segment of their performance at the School Speech Day... Drama Festival and In-school Drama Shows HPCCSS has a tradition

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive

The CME drastically changes the time evolution of the chiral fluid in a B-field. - Chiral fluid is not stable against a small perturbation on v