Towards Knowledge-based Societies.

ICT for Growth and Cohesion in a Global Knowledge-based Economy:

Lessons from East Asian Growth Areas

Workpackage 4.3:

Taiwan Case Study – Growth and Change

Ting-Lin LEE

Department of Asia Pacific Industrial and Business Management, National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Xin-WU LIN

Department of Industrial Policies on Technology Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, Taiwan

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ... ... ... ... 2

1. Introduction ... ... ... ... 6

1.1 Motivation and Objectives ... ... ... 6

1.2 Methodology and analytical framework for the Taiwan study 7 2. Growth drivers since 1990 ... ... ... ... 8

2.1 Industrial structure change ... ... ... 8

2.2 Trends in productivity ... ... ... 9

2.3 Trends of Investment and FDI ... ... ... 10

3. The transformations of Taiwan’s NIS ... ... ... 12

3.1 Trends in R&D Input ... ... ... 13

3.2 Education system and human capital ... ... 15

3.3 Patents and Publications ... ... ... 16

3.4 The role of research institutes ... ... ... 18

3.5 The role of universities ... ... ... 21

3.6 Remarks ... ... ... ... 21

4. Major industrial policies and governance ... ... ... 24

4.1 Existing industrial policies ... ... ... 24

4.2 Major new policies ... ... ... ... 29

4.3 Mode of governance ... ... ... ... 42

4.4 Innovation capability ... ... ... ... 44

5. Overview of the ICT sector ... ... ... ... 49 5.1 The ICT evolution from a historical perspective ... ... 49 5.2 The dynamics of the ICT industry ... ... ... 51

5.3 Demand side of ICT ... ... ... ... 53

6. Policy implications and lessons from Taiwan ... ... 63 6.1 Review of Taiwan’s ICT: policy problems ... ... 64

6.2 Policy suggestions ... ... ... ... 65

6.3 Future problems in the socio-economic field ... ... 66 7. The offshore situation for Taiwan’s ICT/IT in Mainland China ... 69

7.1 The past, present and future of Taiwan IT manufacturers entering the

west market ... ... ... ... 69

7.2 Electronic & electrical indirect investment in Mainland China and elsewhere 76

References ... ... ... ... ... 84

Taiwan Case Study – Growth and Change

Executive Summary

1. Taiwan (Chinese Taipei), with its universal education, highly educated citizenry, high-quality workforce, and facility in cultivating technical personnel, is very well positioned for the development of knowledge-intensive high-technology industries. A key difference from other countries lies in its Taiwan’s geo-relations with Mainland China, which inseparably relates both sides in economic development, even though they have opposing stances in politics at the present time. The case study describes the development and transition of the whole knowledge-based economic society in Taiwan, based on an analysis of the structure of the National Innovation System, particularly in the context of internationalization and the abrupt emergence of Mainland China. 2. Taiwan’s economic development can be divided into three stages: the shift from agriculture to industry (1952-1980); high-tech industry germination and growth (1982-1995); and the era of the financial economy and knowledge-based economy (1996 onwards). After the financial turmoil of 1997, conventional industries felt the pressure of a decline in output and export volume, but thanks to government encouragement and favourable industrial policies, high-tech exports gradually increased and supplanted conventional exports. Because manufacturers’ R&D expenditures are still quite small relative to sales, since 1996 the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) has allowed private enterprises to apply for research project funding in an attempt to bolster their R&D capabilities. Taiwan’s overall labour productivity remains weak, because of its industrial structure and business operation mode. Growth of venture capital companies has been rapid since the early 1990s, but inward FDI has scarcely increased in amount since 1995.

3. In Taiwan’s ICT manufacturing, the supply of products exceeds its demand and prices have plunged. Taiwan’s large IC plants are deeply committed to R&D and integrated with services; the operating profit margin is also advances. In comparison, the Taiwanese IT system contract manufacturer focuses on subcontracted production where the rewards are lowest in value; the R&D intensity and investment are relatively low, and the gross profit rate and operating profit margin are relatively low as well. The scale of enterprises is small and the product homogeneity is high.

4. The MOEA transfers the results of research to the corporate sector for product development and commercialization via technical assistance, information sharing, and manpower training. To do so, the MOEA relies on its own subordinate research organizations, the research departments of state-owned enterprises, and research organizations hired on a case-by-case basis. Industrial technology development work is conducted primarily via in-house R&D and secondarily via technology acquisition. It is working to strengthen interaction between industry, government, universities, and research institutions as a way of promoting technological upgrading throughout the industrial sector. Taiwan’s industry R&D expenditure is highly concentrated in the ICT industry – up to 66.2%. In the face of the fact that the service sector and new emerging industries are the driving

force of economic growth, the government has insufficient funds to invest in R&D, which is really the immediate policy issue the government must pay attention to in the transformation of Taiwan’s industry. Like the EU, by 2010, the nationwide goal is one of Taiwan’s R&D rising to 3% of GDP; and private sector R&D increases up to 60%, including 70% from knowledge-based industries. 5. R&D expenditure as a percentage of GNP showed a gradual increase during the years from 1996 to 2004, but only slowly after 2000. The proportion of enterprise R&D funding and also performing has tended to fall, which differs from the tendency to increase in advanced countries, and Taiwan even lacks inward overseas R&D investment. Compared with other nations, Taiwan has a greater registration ratio of students in higher education, and this advanced educational achievement has been one of the primary factors in the vigorous development of the information industry. Taiwan is thus rich in human resources, with the number of researchers per head of population and labour force constantly increasing from 1996-2004. In terms of basic research, Taiwan ranked 19th in the world in citations in the SCI database in 2004, and 11th in the EI database for engineering and applied research – these rankings have been stable over the past decade. Data on domestic patenting show increases in most years from 1996, though the foreigner share of invention patents is high, suggesting a limited capability in invention with domestic manpower.

6. Since its inception in 1973, the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) has played a major role in upgrading Taiwan’s industrial technology. ITRI created Taiwan’s semiconductor industry from scratch, led the development of other high-tech industries, and helped traditional industries raise productivity. ITRI fosters young companies and new technologies until they are able to survive on their own. Equally, since 1979, the Institute for Information Industry (III) has been a key technology contributor to Taiwan’s ICT industry. Its founding and continuing mission has been to increase Taiwan’s global competitiveness through the development of its IT infrastructure and industry. In order to support leading-edge research and speed up the pace of innovative breakthroughs, Taiwan has established a series of open-type national laboratories. The Taiwanese government has always promoted cooperation between industries and universities in recent years; however several problems remain in the cooperation between industries and universities, so the interaction between industries and universities is largely confined to the supply of talent. The share of enterprise investment in higher education R&D is much behind other countries.

7. Taiwan’s existing industrial policies are directed towards the country’s structure based on SMEs, including tax credits for R&D and the Small Business Investment Research program. The Technology Development Program (TDP), first launched in 1979, has the same focus, including its responsibility for ITRI, III, etc.. Opening these programmes to the private sector since 1997 has allowed direct government support in an effort to stimulate overall industrial research. Subsequently, “TDP for Academia” was launched in 2001 to accept contract research applications from universities for developing pioneering industrial technology, in trying to overcome their weak integration and poor results. The “Innovative Service Oriented Technology Development Program” was re-launched in 2005, to promote the development of innovative service business.

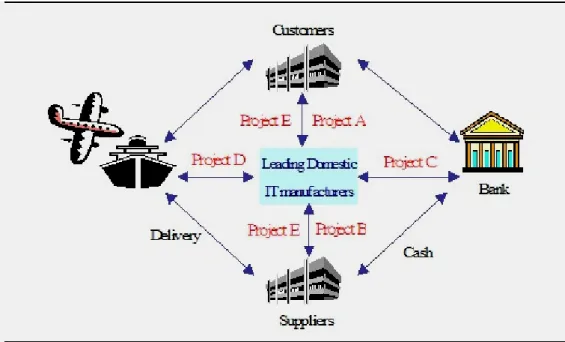

8. Major new policies for ICT have also been implemented. The ABCDE program from 1999 has been directed at a succession of aspects of e-business supply chains, including banks in Project C, delivery in Project D and collaborative design in Project E. Industrial parks have been the cornerstone of Taiwan’s industrial development since their creation in the 1970s, and the concept of industrial zones has expanded to include science parks and parks that emphasize manufacturing support for high-tech industries. Science parks of regionally clustered, around ICs in the north, nanotechnology in the centre, and optoelectronics in the south of the county. A new MOEA programme for 2002-06 was aimed at ‘Two Trillion’ industries (semiconductor and flat-panel display) that are already relatively mature, while the ‘Twin star’ industries (biotechnology and digital content) are new and full of potential.

9. These supply-side policies have been complemented by demand-side policies, including the deregulation of telecommunications and construction of telecom infrastructure. Of special importance are the programs to boost the e-society and m-society. The “e-Taiwan program”, formally approved in June 2002, was combined with other plans to constitute “Challenge 2008: the 6-Year National Development Plan”, and holds the key to its success, through embracing global e-trends. The following M-Taiwan Program is expected to build up the wireless networks, integrate mobile phone networks, set up optical-fibre backbones, etc., and to forge personal computers, the internet and mobile communications into a ‘Ubiquitous Network’.

10. Since the early days of manufacturing IT equipment in Taiwan on an OEM basis, the percentage of Taiwanese manufacturers with their own brands has increased only slightly, contrary to the notion of an evolution from OEM to OBM (own-brand manufacture). On the other hand, Taiwanese enterprises put their resources into product design and became ODMs (own-design manufacturers) and CDMs (collaborative-design manufacturers). By exporting intermediate goods, equipment, technology and management knowledge to the Asia-Pacific area, Taiwanese enterprises started to export final goods to the global market. The number of products with a global market share exceeding 50% has risen markedly since the late 1990s. The introduction and upgrading of these ICT products and technologies mainly depend on the supply from other countries, not from domestic industrialists or research institutions. Instead, domestic industrialists lean towards continuous innovation that raises values, meanwhile successively strengthening the efficiency of the production lines. For avoiding price competition, some major Taiwanese IT companies have tried to find ways to differentiate their products, with branding and product design the two major strategies. As for policies, the government first introduced a project for improving capability in industrial design in 1989. An integrated programme for improving product design capability was launched in 2002, as part of “Challenge 2008”. Some branches of ICT hardware production are growing, while others are now in decline. The export proportion of high-tech industry accounts for approximately 42-45% of all manufacturing; however, the export proportion of computer-relevant products has dropped year by year in recent times.

11. Taiwan has shown an outstanding performance in some indexes, such as Internet users, hosts, bandwidth, and Mobile Internet subscribers. After cultivating IT for so many years, Taiwan has made

great progress in informational social readiness, as shown in education, R&D quality and internet penetration rate. In 2004, Taiwan’s home PC penetration rate was 73% and internet use rate 61%, of which 78% of users adopted broadband. However, the digital divide still remained in rural areas. By 2004, the corporate internet penetration rate reached 81%, of which 96% used broadband (ADSL), with the penetration rate of Taiwan’s e-commerce transactions being 17.6%. In 2003, both online government services and government agencies’ broadband penetration rates reached 100%, and government agencies’ website penetration rate reached 85%. The World Economic Forum (WEF) ranked Taiwan 7th in its Networked Readiness Index (NRI) out of 115 economies, representing an impressive improvement over the ranking of 15th achieved in 2004.

12. Tactical thinking underlying government policy-making divides the industry into 3 groups. When facing ICT downstream assembly manufacturers that consider factors of cost and market, the government should adopt an attitude of open freedom, letting them advance in Mainland China and seizing the market there. The ICT midstream industry, which refers to key components manufacturers, depends crucially on governmental policies. Here, Taiwan’s government should strategically encourage the development of core industries that suit Taiwan with preferential policies such as encouraging and promoting R&D alliances and R&D service industries, providing high-quality information services, encouraging enterprises to develop toward R&D design, brand marketing and logistic services, etc. The third group refers to the ICT upstream industry such as materials and equipment, which are much closer to encouraging foreign manufacturers or large domestic plants to set up R&D centres; in this way strengthening high-level R&D design. Lack of administrative efficiency has become one of the obstacles adversely influencing the competitiveness of the industrial environment. The quality of life generally is still too low.

13. Taiwan’s information and electronic industries have been investing in China since 1990; the range of investment began with early production activities, marketing activities after 1995 and then the fields of R&D. Taiwan has already become the largest source of trade deficitfor Mainland China: 79.5% of the information hardware of Taiwan IT manufacturers was made in China and it accounts for more than 80% of the shipment value of Mainland China’s information hardware. The thinking behind entering Mainland China for Taiwan’s IT manufacturers changes after 2001 from “reducing production cost” to “the requirements of customers” under the pressure of the market. Taiwanese engineers travel to and from the Mainland with increasing frequency. Among the largest-scale foreign-capital enterprises for import and export in Mainland China in 2004, Taiwanese IT firms alone accounted for 28%. Investing in Mainland China initially did not crowd out the production in Taiwan, at least in the electronics and IT area, though it appeared to do so from 2001.

1. Introduction

1.1 Motivation and Objectives

As we have entered the information age and developed a digital economy, with the rapid development of satellite communications, the universal penetration of the internet, and the emergence of intelligent industries, ‘speed’ and ‘innovation’ have become the main factors spurring industrial development. Taiwan (Chinese Taipei), with its universal education, highly educated citizenry, high-quality workforce, and facility in cultivating technical personnel, is very well positioned for the development of knowledge-intensive high-technology industries. This is where Taiwan’s comparative advantage lies.

Industry output by value of the ICT hardware sector and IT software sector respectively was US$684.1 and 49.4 hundred million in 2004. The proportion of ICT expenditure to GDP was then 1.7%. And according to a survey conducted by FIND, the number of internet subscribers (internet access accounts) in Taiwan reached 9.98 million as of December 2004. In 2004, 61% of households in Taiwan were connected to the internet, and 81% of Taiwan enterprises had internet access. The bandwidth used for international internet connection in Taiwan exceeded 70 Gbps; there were over 5 million mobile internet subscribers in Taiwan; and the Taiwan government offered 847 government services online as of the end of 2004 (FIND website, 2006).

In contrast to other countries, the most special aspect of Taiwan lies in its deep historical origins and geo-relations with Mainland China, which causes both sides to have an inseparable relation in economic development, even though they have opposing stances in politics at the present stage. All these complex factors help shape the intricate appearance of the development process in the formidable Taiwan ICT industry.

Taiwan’s ICT policy developments have had fruitful outcomes. In June 2002, the Taiwan government proposed the “Two-Trillion and Twin-Star” programme to establish digital content as one of the industries with an annual production value of over NT$1 trillion. Facing the changes of the digital world, the Taiwan government has actively worked to promote digitization through a number of initiatives in recent years to improve the nation’s IT proficiency and the competitiveness of domestic IT industries. In May 2002, NICI and other government agencies worked together to launch the “e-Taiwan Program” as a part of the Challenge 2008 Program. With the need for a sound e-business framework and application standards, DOIT of MOEA commissioned ACI of III1 to undertake long-term research and promotion work with regard to the “E-Business Standard Research Plan”. Besides, in order to continually strengthen the enterprises’ digital capacities, projects A/B/C/D/E aim to create an e-business supply chain system, lay the foundations for a new business model where “orders are received in Taiwan, production can take place anywhere in the world”. In addition, the Taiwan government proposed the “M-Taiwan Program” to promote a ubiquitous network and e-services in Taiwan with a budget of NT$37 billion over five years.

1.2 Methodology and analytical framework for the Taiwan study

This case study describes the development and transition of the whole knowledge-based economic society in Taiwan, based on an analysis of the structure of the National Innovation System (NIS) from the viewpoint of coevolution, and explains the efforts Taiwanese government authorities made in the development of high-tech or sunrise industries (especially ICTs) from both the supply side and demand side of industrial policy; especially when facing the tendency toward internationalization and the abrupt emergence of Mainland China. Because Taiwan is newly industrialized, its industry depended on foreign direct investment in its early days, subcontract production modes (e.g. OEM), before establishing its own innovative competence.

Section 2: Taiwan’s economic growth overview

The first step will provide an overview of the economic growth trends of Taiwan, with the transformation of the industrial structure and its relationship with ICT research and production. Section 3: Analysis of the changes in the Taiwan NIS

The in-depth analysis of Taiwan focuses on development trends during the period 1990-2005 (approx.). Specific attention is devoted to the range of indicators, and to assessing the related actors, agencies, organizational and institutional changes, as well as the conditions for knowledge-based techno-economic growth observed in this period. In particular, the study explores the mechanisms of adjustment to global challenges.

Section 4: Major industrial policies and governance

This part of the study explores the related Taiwanese ICT programmes and other related initiatives: campaigns at the national level to increase the level of ICT usage, FDI policies, financial and non-financial incentives to attract higher participation among local and foreign companies to invest in the ICT industry. Here, we describe the supply side and demand side to explore government efforts in promoting ICT development and its governance.

Section 5: The role played by ICT

The aim of this section will be to present the major ICT characteristics, their potential for future growth in the global arena, to describe the implications of ICT trends and paths for Taiwan policy on research, education, growth and competition, and to identify the major lessons to be learnt in terms of growth conditions and trajectories, societal change, and its contribution. The section covers availability of ICTs that allow access to knowledge and communication, in particular the Internet (fixed, mobile, wireless, etc.), access to and usage of ICTs (phone lines, number of personal computers, internet users, internet hosts, etc.). It will also identify those conditions which allow the society to adapt to a changing set of opportunities, and to balance the tensions between the global and the local sphere, public policy and business strategy dimensions, and economic growth, social equity (bridging digital divides), quality of life (improving an intelligent, safe and convenient society) and individual satisfactions, turning them into leverage for growth.

Section 6: Policy Implications and lessons from Taiwan

of the tendency to internationalization and globalization and the emergence of the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China), and further to explain how the development of Taiwan’s ICT industry should be adjusted; given the political conflict between Taiwan and Mainland China: whether the two have an opportunity to create partnerships of co-opetition or maintain competitive relations of a zero-sum kind.

Special Study: The offshore development of Taiwan’s ICT/IT in Mainland China

This special study describes the general production situation whereby Taiwan IT manufacturers invest in Mainland China in recent years: It begins from the early production activity and has gradually extended to the both ends of the “smiling curve”. In other words, it refers to stretching over the front-end of R&D activity and the back-end of marketing activity. This section aims to assess how Taiwan IT manufacturers launched investment patterns, the forms of division of labour, and the arrangements of production, R&D, and marketing, from the viewpoint of evolution.

2. Growth drivers since 1990 2.1 Industrial structure change

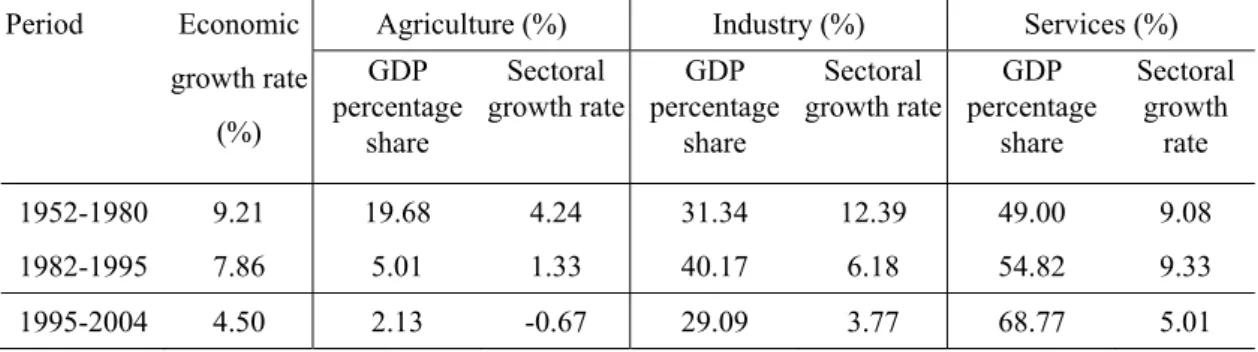

To understand the development of the national industrial system, it will be most insightful to break down Taiwan’s economic development into three stages as in Table 2.1 (Yu, 1999: 6-22).

The Shift from Agriculture to Industry (1952-1980) High-tech Industry Germination and Growth (1982-1995)

The Era of the Financial Economy & Knowledge-based Economy (1996 onwards)

Table 2.1: Economic Growth and Structural Change in Taiwan (at 1991 prices) Period Economic

growth rate (%)

Agriculture (%) Industry (%) Services (%) GDP percentage share Sectoral growth rate GDP percentage share Sectoral growth rate GDP percentage share Sectoral growth rate 1952-1980 9.21 19.68 4.24 31.34 12.39 49.00 9.08 1982-1995 7.86 5.01 1.33 40.17 6.18 54.82 9.33 1995-2004 4.50 2.13 -0.67 29.09 3.77 68.77 5.01

Source: ROC National Income (in Chinese). Taipei: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, R.O.C.

The era of the financial economy began to take shape in East Asia in the late 1990s. Noticeable signs included the gradual growth of futures trading based on foreign exchange rates, interest rates and stock prices, as the futures market emerged in the region; the replacement of cash transactions by the use of credit cards; the introduction of electronic commerce via the internet; and the rapid takeoff of the financial services sector. More importantly, increased financial liberalization and globalisation transformed the regional economy into one wherein a single incident can trigger a chain reaction.

The East Asian financial turmoil broke out in early July 1997, and immediately none of the world’s developing or newly industrialized countries in the world was able to escape at least some degree of damage from the onslaught of the financial crises. For Taiwan, the East Asian Turmoil brought some adverse effects, such as: a drop in the economic growth rate, a fall in industrial production growth, negative growth in foreign exports, depreciation of the New Taiwan Dollar, a fall in the stock exchange index, a rise in the unemployment rate, and so forth.

Due to the difficulty of obtaining affordable land and the rising cost of labour, conventional industries felt the pressure of a decline in output and export volume. Nevertheless, thanks to the government’s encouragement and favourable industrial policies, high-tech exports gradually increased and supplanted conventional exports. High-tech exports have grown to a quarter of total exports in recent years, and Taiwan has become the leading maker of several high-tech products. For many years the government has encouraged industry to engage in technology development. For instance, every year the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) provides funding to non-profit research institutions for the development and transfer to the private sector of “critical, common, and forward-looking” technologies, and allows public and private enterprises to participate in technological research projects. In addition, the MOEA has also implemented the “Statute Regarding the Promotion of Industrial Upgrading,” the “Regulations Governing New Product Development Guidance”, and the “Regulations Governing Encouragement of New Product Development by Private Enterprises”. In order to encourage and support industrial R&D, the NSC has promoted the “Research and Development of Key Parts, Components and Products Program” within the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park, and also regularly provides market information and technical assistance in order to reduce market risk and stimulate industry’s willingness to engage in R&D work. Because manufacturers’ R&D expenditures are still quite small relative to sales, since 1996 the MOEA has allowed private enterprises to apply for research project funding in an attempt to bolster their R&D capabilities (ibid., p.25). The “Technology Development Program” will be further described later.

2.2 Trends in productivity

The cause of the inferior performance of Taiwan’s labour productivity is associated with the industrial structure and business operation mode. Taiwan’s industrial structure is largely concentrated on so-called ICT domain in “high-tech industry”, although in the past due to the fast growth of the ICT industry, Taiwan’s overall economic growth was supported. However, in recent years IT hardware industry has been facing the threat of latecomer countries, a rapid decline of product prices and the constraints imposed by large international companies, thus overall ICT industrial value-added and gross profit have gradually reduced. Additionally, the low growth of service sectors and the low growth rate of labour productivity in recent years, which is even lower than the growth rate of manufacturing labour productivity (see Figure 2.1), have resulted in an insufficient growth of Taiwan’s overall labour productivity (Lin et al., 2005 ).

Figure 2.1: Average growth rate by sector in Taiwan, 1971-2004

2.3 Trends of Investment and FDI 2.3.1 Venture Capital

At the initial stages as Taiwan started to develop in the high-tech field, there was no venture capital business. Thus, the government established the Development Fund of Executive Yuan in 1973 to invest in venture capital and coordinated the Chiang Tung Bank to provide refinance for venture capital. However, the preliminarily introduced venture capital created only a few successful cases that led industrial development. The first venture capital company was established in 1984 after reinvestment by Acer. The number of venture capital companies increased slightly to the early 1990s (Wu et al., 2002), then grew to 259 in 2004. Their accumulated capital increased from NT$200 million in 1984 to NT$ 184.5 billion in 2004, growing over 922 times within two decades. As part of the effort to promote venture capital firms, Taiwan’s government offered generous tax incentive programmes, as firms were entitled to a 20% tax concession upon investment in strategic industries. To qualify as a venture capital firm and be entitled to tax benefits, a venture capital firm has to invest at least 70% of its funds in so-called high-tech companies, as defined by the government in four items of the “Regulations Governing Venture Capital Investment Enterprises”.

7.2 5.8 5.71 9.20 9.60 4.83 5.50 9.36 9.2 3.31 3.30 7.00 8.25 4.40 4.90 11.30 3.61 3.70 4.77 12.10 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 1971-1987 1988-1994 1995-1999 2000-2004 2004 real growth rate % GDP Growth Rate Service Industry Manufacturing

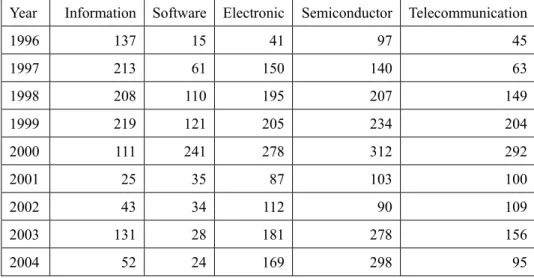

Table 2.2: Venture Capital by Industry and by Number of Companies

Year Information Software Electronic Semiconductor Telecommunication

1996 137 15 41 97 45 1997 213 61 150 140 63 1998 208 110 195 207 149 1999 219 121 205 234 204 2000 111 241 278 312 292 2001 25 35 87 103 100 2002 43 34 112 90 109 2003 131 28 181 278 156 2004 52 24 169 298 95

Unit: no. of companies

Source: Taiwan Venture Capital Association 2004 Yearbook.

Table 2.3: Venture Capital by Industry and by Value of Investments

Year Information Software Electronic Semiconductor Telecommunication

1996 26.9 2.52 7.48 24.53 7.72 1997 37.88 8.8 21.5 27.7 8.14 1998 32.66 19.55 40.47 40.31 33.34 1999 54.01 17.09 40.81 60.73 36.03 2000 20.07 26.76 35.55 63.99 58.16 2001 2.2 3.4 9.1 18.2 13.3 2002 7.2 3.1 21.3 13.9 34.8 2003 20.7 3.2 22.3 38.3 15.6 2004 7.4 1.7 19.4 33.7 9.7 Unit: 100m NT$

Source: Taiwan Venture Capital Association 2004 Yearbook.

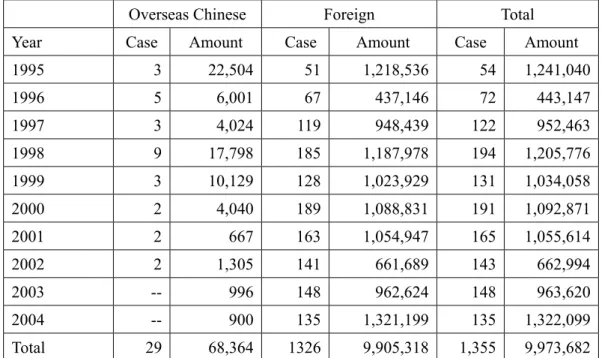

2.3.2 The status of FDI

The investment in Electronic & Electrical Appliances by overseas Chinese and foreign companies in Taiwan has had a tendency to rise gradually in recent decades. The year 2000 was a watershed, reflecting the first change of political party in Taiwan, when FDI attained high levels. However, the political and economic situation after the political change (such as political infighting among parties, the economic emergence of Mainland China and India, etc.) was not as good as anticipated; and the cases and amounts of overseas Chinese and FDI have reduced year by year after 2001. In 2004 the total of approved cases dropped to the lowest level since 2000 but increased considerably in amounts. This phenomenon was mainly because the government opened up an increasing range of sectors to foreign participation. This was particularly so in ICT, where there were changes to foreign investment regulations, particularly in foreign ownership levels in the telecommunications sector.

Table 2.4: Electronic & Electrical Appliances approved for Overseas Chinese and Foreign Investment in Taiwan, 1995-2004

Overseas Chinese Foreign Total

Year Case Amount Case Amount Case Amount

1995 3 22,504 51 1,218,536 54 1,241,040 1996 5 6,001 67 437,146 72 443,147 1997 3 4,024 119 948,439 122 952,463 1998 9 17,798 185 1,187,978 194 1,205,776 1999 3 10,129 128 1,023,929 131 1,034,058 2000 2 4,040 189 1,088,831 191 1,092,871 2001 2 667 163 1,054,947 165 1,055,614 2002 2 1,305 141 661,689 143 662,994 2003 -- 996 148 962,624 148 963,620 2004 -- 900 135 1,321,199 135 1,322,099 Total 29 68,364 1326 9,905,318 1,355 9,973,682

Source: Annual Report of Overseas Chinese & Foreign Investment, Outward Investment and Mainland Investment, Investment Commission, MOEA (2004:23, 39)

3. The transformations of Taiwan’s NIS

The Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) is chiefly responsible for industrial technology applications research, and it transfers the results of research to the corporate sector for product development and commercialization via technical assistance, information sharing, and manpower training. To accomplish these goals, the MOEA relies on its own subordinate research organizations, the research departments of state-owned enterprises, and research organizations hired on a case-by-case basis. Industrial technology development work is conducted primarily via in-house R&D and secondarily via technology acquisition. The MOEA is working to strengthen interaction between industry, government, universities, and research institutions as a means of promoting technological upgrading throughout the industrial sector, see Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Methods of promoting industrial technology upgrading

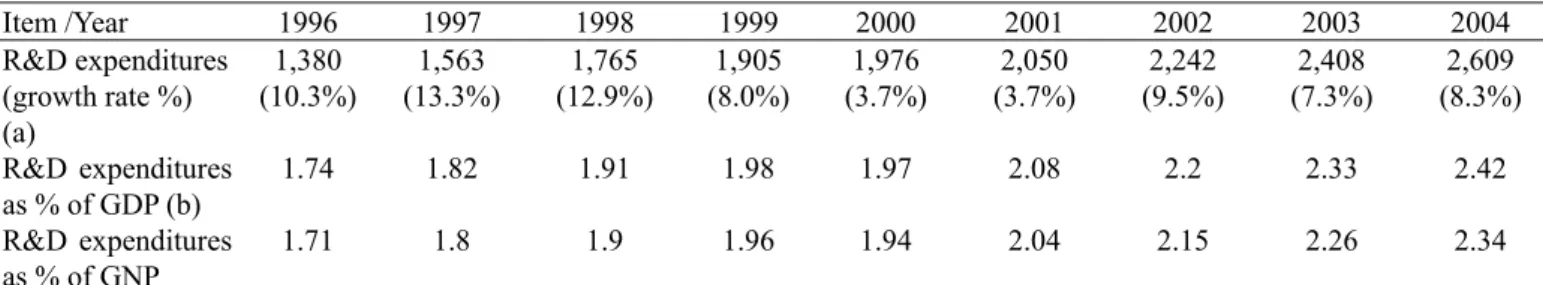

3.1 Trends in R&D Input

According to the annual Survey of National Science and Technology Activity, total public and private R&D expenditures amounted to NT$197.6 billion, or 1.94% of GNP in 2000, and NT$ 260.9 billion, or 2.34% of GNP in 2004. Furthermore, the nation’s total R&D spending as a proportion of GDP remained at an average around 2.2% during these five recent years. R&D expenditure as a percentage of GNP showed a gradual increase during the years from 1996 to 2004, although the growth rate of R&D expenditures declined sharply in 2000. However, the annual average growth rates of these expenditures are only 6.5% in the five most recent years (Table 3.1). Of overall national R&D spending of NT$260.85 billion in 2004, government agencies contributed NT$88.47 billion (33.9%), business enterprise NT$168.1 billion (64.4%), higher education NT$3.1 billion (1.2%), private non-profit organizations NT$1.1 billion (0.4%), and foreign institutions just NT$60 million (0.0%) (see Table 3.2).

As described above, 64.4% of R&D funds came from enterprise in 2004. The proportion of enterprise R&D funds has tended to fall, which differs from the increasing tendency in advanced countries, and Taiwan even lacks overseas R&D investment (certain countries get 10% from overseas R&D capital). Similarly, according to the performing of R&D, the proportion by enterprises also has a tendency to fall year by year.

Table 3.1: Taiwan’s R&D expenditures 1996-2004 Item /Year 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 R&D expenditures (growth rate %) (a) 1,380 (10.3%) 1,563 (13.3%) 1,765 (12.9%) 1,905 (8.0%) 1,976 (3.7%) 2,050 (3.7%) 2,242 (9.5%) 2,408 (7.3%) 2,609 (8.3%) R&D expenditures as % of GDP (b) 1.74 1.82 1.91 1.98 1.97 2.08 2.2 2.33 2.42 R&D expenditures as % of GNP 1.71 1.8 1.9 1.96 1.94 2.04 2.15 2.26 2.34

(a) Expenditures in NT$100 million; includes humanities and social sciences; includes government planning and supporting expenditures on R&D; excludes national defence S&T.

(b) GDP-National Income in Taiwan Area of Republic of China, Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan

Data Source: Indicators of Science and Technology, Republic of China, 2005/12

Table 3.2: R&D expenditures by source of funds 1999-2004 Business Enterprise % Government % Higher Education % Private Non-profit % Foreign % 1999 190,520 125,712 66% 61,989 32.5% 1749 0.9% 959 0.5% 110 0.1% 2000 197,631 128,386 65% 65,980 33.4% 2193 1.1% 999 0.5% 74 0.0% 2001 204,974 132,950 64.9% 68,339 33.3% 2719 1.3% 931 0.5% 35 0% 2002 224,428 141,695 63.1% 79,004 35.2% 2762 1.2% 930 0.4% 38 0% 2003 240,820 151,550 62.9% 85,850 35.5% 2777 1.2% 854 0.4% 60 0% 2004 260,851 168,079 64.4% 88,468 33.9% 3130 1.2% 1113 0.4% 60 0.0% Unit: Million NT$

Data Source: Indicators of Science and Technology, Republic of China, 2005

It is clear for the higher education sector that R&D expenditures are primarily on basic research; and business enterprise puts more R&D expenditures into experimental development (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3: R&D expenditures by type of R&D, 2004

Total Basic research Applied research Experimental development Total 260851 29631 11.4% 65449 25.1% 165771 63.6% Business Enterprise Sector 167873 1131

0.7% 29543 17.6% 137198 81.7% Government Sector 61144 12859 21.1% 22778 37.3% 25507 41.7% Higher Education Sector 30350 15394

50.7%

12051 39.7%

2905 9.6% Private Non-profit Sector 1484 246

16.6% 1077 72.6% 161 10.9% Unit: million NT$

3.2 Education system and human capital

Faced with the fierce global competition of globalization in the 21st century, Taiwan must cultivate human resources with first-rate skills in design, production, and services in order to promote the development of knowledge-intensive industries.

Taiwan had a total of 162 higher education establishments in the 2005 School Year (from 2005/8-2006/7), 89 of which were universities. The student population of higher education for the same year was 938,648 students, 449,695 of whom belonged to the science and technology field, including 2,165 doctoral students and 42,334 masters students (Ministry of Education website: www.edu.tw, 2006). Compared with other nations, Taiwan has a higher registration ratio, with education and training in accord with national competitiveness requirements (Tzeng and Lee, 2001). This advanced educational achievement has been one of the primary factors in the vigorous development of the information industry.

An overview of the Taiwan educational system reveals that, in 2004, the government allotted 39.0% of its budget to the higher education. Public education enrolment rates reached 99.2% in the 2004 School Year, an achievement that compares favourably with other nations. The incorporation of science into the compulsory curriculum and the development of students’ interest in technology also foster the rapid development of science.

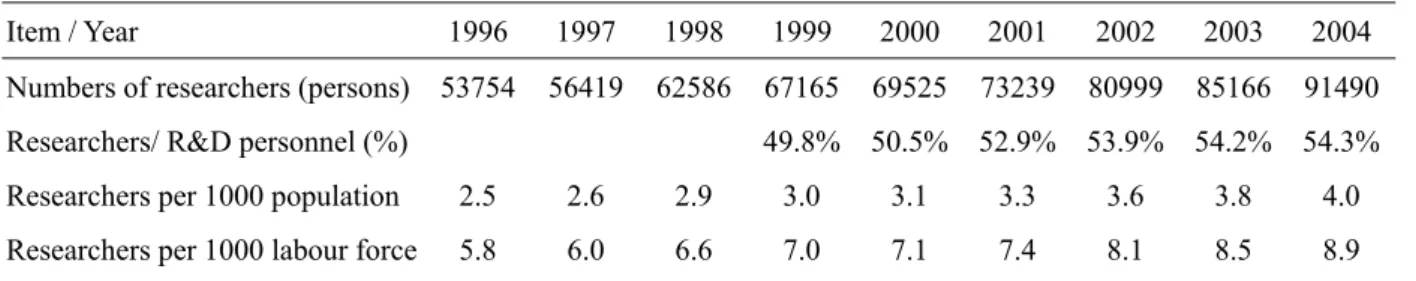

Concerning S&T indicators, Taiwan is rich in human resources. The number of researchers both per ten thousand of population and per ten thousand of the labour force has constantly increased over the preceding four years up to 2004 (Table 3.4).

Table 3.4: Numbers of Taiwanese researchers 1996-2004

Item / Year 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Numbers of researchers (persons) 53754 56419 62586 67165 69525 73239 80999 85166 91490 Researchers/ R&D personnel (%) 49.8% 50.5% 52.9% 53.9% 54.2% 54.3% Researchers per 1000 population 2.5 2.6 2.9 3.0 3.1 3.3 3.6 3.8 4.0 Researchers per 1000 labour force 5.8 6.0 6.6 7.0 7.1 7.4 8.1 8.5 8.9

Data Source: Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 1-19 & 1-22), Republic of China, 2005

R&D personnel includes researchers, technicians, and supporting personnel. A total of 168,524 people were engaged in R&D work in 2004, and maintained an increasing trend over the preceding years. The total for 2004 included 91,490 researchers (54.3%), 59,583 technicians (35.4%), and 17,451 supporting personnel (10.4%). In terms of the distribution of researchers, 50,795 (47.3%) worked in Business Enterprise, 17,020 (50.4%), in the Government sector, and 22,781 (87.7%) in Higher education. Among these researchers, 23,306 (25.47%) held PhD degrees, and 38,912 (42.53%) Masters degrees. Similarly, the percentage of researchers with Masters and PhD degrees has also increased. The proportion of researchers among all R&D manpower has hovered around 56.3% over the past 10 years (see Tables 3.5 and 3.6).

Table 3.5: R&D Personnel in Taiwan, 1994-2004 Year Type Sector of

Performance R&D Personnel Researchers % Technicians % Supporting Staff % 1994 95,088 58,156 61.2 24,067 25.3 12,865 13.5 1995 105,822 66,478 62.8 25,635 24.2 13,709 13.0 1996 116,853 71,611 61.3 28,987 24.8 16,255 13.9 1997 129,165 76,588 59.3 34,021 26.3 18,556 14.4 1998 129,305 83,209 64.4 30,535 23.6 15,561 12.0 1999 134,845 67,165 49.8 51,754 38.4 15,926 11.8 2000 137,622 69,526 50.5 51,581 37.5 16,515 12.0 2001 138409 73,239 52.9 48,886 35.3 16,283 11.8 2002 150200 80,999 53.9 51,820 34.5 17,381 11.6 2003 157225 85,166 54.2 55,001 35.0 17,058 10.8 2004 168,524 91,490 54.3 59,583 35.4 17,451 10.4 Business Enterprise 107,473 50,795 47.3 46,362 43.1 10,317 9.6 Government 33,744 17,020 50.4 11,085 32.9 5639 16.7 Higher education 25,967 22,781 87.7 1888 7.3 1298 5.0 Private Non-profit 1340 894 66.7 248 18.5 198 14.8

Source: Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 1-15), Republic of China, 2005

Table 3.6: Researchers by degree level, 1996-2004

Degree /Year 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 PhD 12,589 14,218 15,947 17063 18,069 19,200 21,004 22,022 23,306 Master 19,663 20,017 22,644 24113 25,715 28,181 32,632 35,348 38,912

Source: Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 1-19), Republic of China, 2005

3.3 Patents and Publications

In Taiwan, basic research is chiefly conducted at the Academia Sinica, the national laboratories, various research centres, and university departments and graduate schools. The chief source of funding for this research is the Science and Technology Development Fund (White Paper on Science and Technology, NSC, 1997).

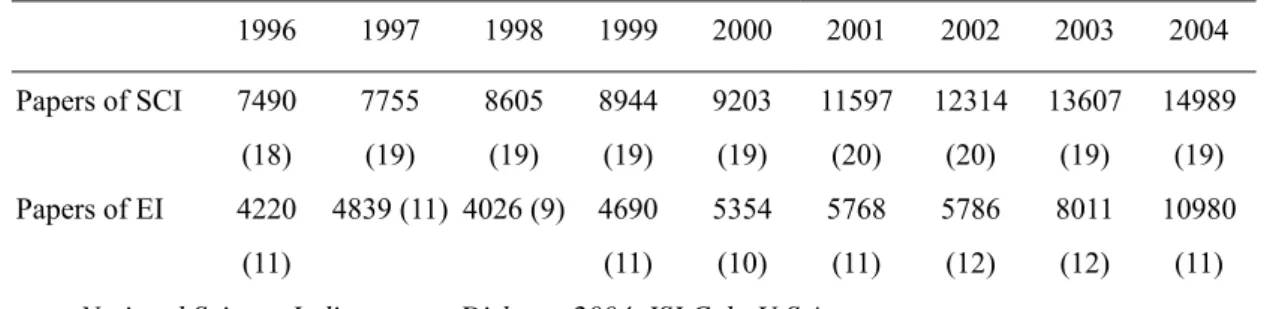

The number of academic papers published is a direct indicator of basic research. The number of Taiwan’s papers cited in the SCI database has increased every year (Table 3.7). In 2004, there were 14,989 articles cited by Taiwan’s authors in the SCI database, ranking at 19 in the world.

Outside of universities and colleges, most of Taiwan’s engineering and applied research is conducted at the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) and other public or non-profit research institutes. Over the past decade, an excellent research record has been achieved in such areas as electronics, information, communications, materials science, biology, agriculture, and food technology. There are 10,983 papers by Taiwan’s authors in the EI database in 2004, ranking 11 in

the world.

Table 3.7: Number of papers and Rank in SCI and EI, 1996-2004

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Papers of SCI 7490 (18) 7755 (19) 8605 (19) 8944 (19) 9203 (19) 11597 (20) 12314 (20) 13607 (19) 14989 (19) Papers of EI 4220 (11) 4839 (11) 4026 (9) 4690 (11) 5354 (10) 5768 (11) 5786 (12) 8011 (12) 10980 (11)

Data Source: National Science Indicators on Diskette, 2004, ISI Col., U.S.A. COMPENDEX, Oct. 2004, E.I. Inc., U.S.A.

Another tangible result of research on science and technology has been the number of patents granted. Of the patents approved in 2004, 68% were by Chinese nationals and 32% by foreign nationals. This represents a substantial increase in the number filed by Chinese Nationals (Table 3.8).

Table 3.8: Domestic patents applied for and granted, 1996-2004

Item Patents applied for Patents granted

Total Compatriot Foreigner Total Compatriot Foreigner 1996 47,055 31,185 15,870 29,469 19,410 10,059 1997 53,164 33,657 19,507 29,356 19,551 9,805 1998 54,003 34,243 19,760 25,051 16,417 8,634 1999 51,921 32,643 19,278 29,144 18,052 11,092 2000 61,231 36,369 24,862 38,665 23,737 14,928 2001 67,860 40,210 27,650 53,789 32,310 21,479 2002 61,402 35,926 25,476 45,042 24,846 20,196 2003 65,742 39,663 26,079 53,034 30,955 22,079 2004 72,082 43,020 29,062 49,610 33,517 16,093

Source: Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 7-2), Republic of China, 2005

As for innovation patents, in 2004, there were 41,919 invention patent applications, of which 20,454 were approved. It is evident that, whether looking at the invention patents applied for or approved, the number of compatriot invention patents was very significantly lower than foreign. This presents a limited capability in invention with domestic manpower.

The number of patents granted in the US to assignees in Taiwan has increased rapidly, as have patents granted in Taiwan, although a large share of the patents in Taiwan is granted to foreigners. Table 3.9 suggests that each NT$ 1 billion that the government invested in research in 2004 generated 1,210 academic papers, 27 patents, 131 technical reports, 29 technological innovations, 39 copyrights, 0.48 technology acquisitions, 23 technology transfers, and 354 instances of technical service. Table 3.10 shows indicators of research output of the period 2000-2004 (NSC, 2005:33-34).

Table 3.9: Patents 1996-2004

Item/Year 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Invention patents applied 15,959 20,046 21,978 22,161 28,451 33,392 31,616 35,823 41,919 Compatriot 2,938 3,761 5,213 5,804 6,830 9,170 9,638 13,049 16,747 Foreigner 13,021 16,285 16,765 16,357 21,621 24,222 21,978 22,774 25,172 Invention Patents granted 8,594 9,008 8,478 11,280 15,657 24,429 23,036 25,134 20,454 Compatriot 1,393 1,611 1,598 2,139 3,834 6,477 5,683 6,399 7,521 Foreigner 7,201 7,397 6,880 9,141 11,823 17,952 17,353 18,735 12,933 Patents granted in U.S.P.O. 2,419 2,057 3,100 3,693 4,667 5,371 5,431 5,298 5,938

Source: 1. Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 7-3, 12, ), Republic of China, 2005; 2. Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, TIPO website (2006)

Table 3.10: Research Outputs Indicators, 2000-2004 Year Funding (NT$m) GDP deflator Cost (NT$m)

Papers Patents Technical Reports Copyrights Technological Innovations Technology Acquisitions Technology transfers Technical services 2000 89,317 101 88,119 51,009 (579) 2,808 (32) 6,974 (79) 321 (4) 409 (5) 70 (1) 1,255 (14) 30,295 (344) 2001 58,330 100 58,330 42,587 (730) 1,327 (23) 6,974 (120) 57 (1) 271 (5) 60 (1) 1,091 (19) 32,990 (566) 2002 61,579 100 61,548 46,770 (760) 1,194 (19) 8,158 (133) 64 (1) 693 (11) 342 (6) 1,173 (19) 53,333 (867) 2003 66,738 103 65,091 46,586 (716) 1,024 (16) 9,150 (141) 3,828 (59) 474 (7) 142 (2) 1,962 (30) 61,770 (949) 2004 73,213 110 66,715 78,763 (1210) 1,774 (27) 8,740 (131) 2,632 (39) 1,958 (29) 32 (0.48) 1,534 (23) 23,615 (354)

Source: Central Government Scientific Technological R&D Performance, NSC, 2004:34

Note: Figures in brackets are results indicators expressing the relative quantity of results obtained for each NT$1 billion of input. Since there is a one-year time lag between resource input and result output for the items of “papers”, “patents”, and “technology transfers”, the results indicators for these items are consequently expressed as results (papers/items)/ cost during previous year; the remaining items are calculated on the basis of cost during the current year.

3.4 The role of research institutes

3.4.1 The Industry Technology Research Institute (ITRI)

At its establishment in 1973, ITRI was only an electronics research and development centre; however it became a ‘quasi-government corporation’ as a result of the accelerated upgrading of industrial technology and the promotion of industrial performance. Now, after 28 years, ITRI is composed of seven laboratories and nine research centres handling research in electronics, computers & telecommunications, energy & resources, mechanics, chemistry, optoelectronics, industrial safety and health, measurement standards, aviation and space, biomedical engineering, and materials science. In regard to ITRI’s budget, about a third of this comes from the private sector for contract research and various joint development projects, while two thirds come from various government sources (Mathews, 1997: 31). For years, ITRI served as a bridge between academic studies and industrial applications and provided strong backing to develop industries.

technology. ITRI created Taiwan’s semiconductor industry from scratch, led the development of its other high-tech industries, and helped traditional industries raise productivity, to catch up with advanced economies. ITRI participates in this role, fostering young companies and new technologies until they are able to survive on their own. As a whole, the crucial roles have been as follows (ITRI Annual Report, 1999):

* Accelerating industrial technology development in Taiwan to promote industrial growth and societal well-being.

* A national-level, government-sponsored organization for applied research in industrial technology. * A private, non-profit organization able to accept governmental and private-sector research

contracts.

* Undertaking the following types of research: medium and long-term applied research in development of generic, forward-looking, and advanced technologies; short-term research into improving processes and developing new products according to industrial-sector needs.

* Disseminating research results to the industrial sector in timely and appropriate fashion in accordance with the principles of justice, fairness, and openness.

* Undertaking trial mass production to ensure the feasibility of new industrial technologies, then planning for strategic withdrawals upon project completion.

* Providing industrial services to and fostering the technological development of small and medium-sized businesses.

* Cultivating human resources in industrial technology for the good of the nation.

As a summary of these missions, it can be concluded there have been two major objectives: promoting sunrise industry and speeding up current industry growth (Figure 3.2).

3.4.2 The Institute for Information Industry (III)

Since its inception in 1979, the Institute for Information Industry (III) has been a key technology contributor to Taiwan’s ICT industry, while also playing a vital role in promoting the adoption of ICT in both public and private sectors. Its founding mission, which continues today, was to increase Taiwan’s global competitiveness through the development of its information technology infrastructure and industry.

III’s current work can be summarized as aiding Taiwan in becoming a world-class ICT leader. This leadership involves not only having a vibrant ICT industry, but also ensuring that public and private institutions in Taiwan can take full advantage of the benefits of ICT, such as increasing productivity, raising efficiency, and improving quality of life.

Its main missions for ICT and contributions in the past 25 years are the following:

▪ Serve as a think tank on ICT policy and consultant to the government on fostering development of the ICT industry. Assisted the Science and Technology Advisory Group (STAG) for the development of the “e-Taiwan Plan” which constitutes an important component of “Challenge 2008”, “The Six-year National Development Plan”, and to support the e-Taiwan Program Office in planning and implementing its mission.

▪ Provide innovative R&D, software technologies and interoperability standards for Taiwan’s ICT industry. Entrusted by the government, III engaged in developing national, large-scale information systems for government automation, to lead the trend of computerization by the private sectors.

▪ Enhance the development of the ICT industry and cultivate new industries.

▪ Promote the internationalization of Taiwan’s ICT industry and international collaboration. Allied with scores of multinational corporations and global R&D institutions in technology R&D that included Sony Ericsson, TCS, QAI, Fujitsu, Sony, Microsoft, IBM, Cisco, Motorola, Sun, Nazomi, CMU, USC, MIT; and assisted some multinational corporations companies such as IBM, Sony, HP, Microsoft, Nokia, Dell, etc., to establish R&D centres in Taiwan.

▪ Proliferate ICT applications and bridge the digital divide.

▪ Foster ICT elites and human resource development. Based on the varying needs of the market, government, and individuals both in Taiwan and abroad, III has organized basic training, professional accreditation, and cross-industry courses. Providing full-scale information technology education and training, from basic training, professional certification, to most advanced multi-discipline integration, for assisting the government and industries to cultivate information technology skills. Yearly enrolment for on-job, career switching and teacher training exceeded 10,000 person-classes; whereas the accumulated enrolment has surpassed 300,000 person-classes in 2004.

3.5 The role of universities

The Taiwanese government has always promoted cooperation between industries and universities in recent years; for example, the “TDP for Academia” which the Industrial Development Bureau in MOEA brought out is a best policy action scheme. However, there are still several problems in the cooperation between industries and universities at the present stage:

• The cognitive lag is great between industries and universities.

• Channels of communication between industries and universities are lacking. • The research results are hard to commercialize.

• Professors’ studies tend to basic research, which do not fit the needs of industry, and the system of professorial promotion is inflexible.

• Incentive mechanisms are insufficient to encourage scholars in academic circles to engage in industry-university cooperation.

• No matter what the organizational scale or funds, the research in universities is insufficient. The interaction between industries and universities is largely confined to the supply of talent, the reasons being as follows:

• Taiwan has established an intact research system: The government has set up industrial science and technology research institutes such as ITRI and III to develop industrial technology, and transfers the technology to domestic proprietors, which serves as the backing for industrial R&D (especially for SMEs).

• For a long time, the major tasks government has given universities are teaching and research, not promoting the development of industries; that is to say, the incentive mechanism which the government offers leads the energy of universities to academic research, lacking contact with the foresight research required by industry. Accordingly, the industrial circles are short of inducements and opportunities to seek support from academic circles.

• Taiwanese universities and colleges have quite high proportions of high-level research manpower.

• In terms of “innovation”, the interaction between industries and universities and the degree of reciprocal support still have space to improve and be promoted.

3.6 Remarks 3.6.1 Inputs

According to an investigation of the Taiwan Institute of Economic Research (2005) on “the distributive proportion variation of various kinds of innovative funds enterprises invest / are expected to invest in Taiwan”, the main innovative direction of Taiwan enterprises lie in innovative products and manufacturing processes; however, the proportion of marketing innovation is expected to rise in the future.

Table 3.11: Investment shares of Taiwan enterprises by type of innovation, 2004-06

2004 2005 2006

Number in sample 167 177 148

Process innovations 32% 30% 29%

Product (good or service) innovations 40% 41% 41%

Organizational innovations 14% 14% 12%

Marketing innovations 14% 15% 18%

Source: TIER (2005), The investigation of enterprise R&D and innovative trend in Taiwan in 2005 3.6.2 Linkages

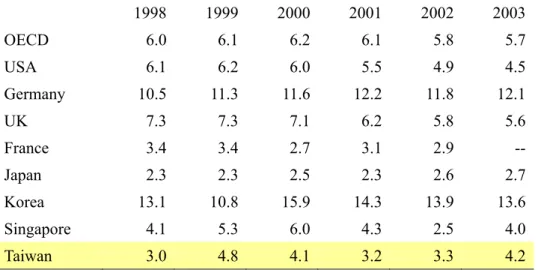

1. The proportion of enterprise investment in higher education R&D (HERD) falls greatly behind other countries, which shows that the linkage is still not enough between industry and university; this phenomenon will result in the insufficiency of innovation sources in industry, capacity is hard to promote, and the R&D results from universities are unable to be commercialized (Table 3.12).

Table 3.12: Proportion of R&D funds in Higher Education coming from Enterprises, %

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 OECD 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.1 5.8 5.7 USA 6.1 6.2 6.0 5.5 4.9 4.5 Germany 10.5 11.3 11.6 12.2 11.8 12.1 UK 7.3 7.3 7.1 6.2 5.8 5.6 France 3.4 3.4 2.7 3.1 2.9 --Japan 2.3 2.3 2.5 2.3 2.6 2.7 Korea 13.1 10.8 15.9 14.3 13.9 13.6 Singapore 4.1 5.3 6.0 4.3 2.5 4.0 Taiwan 3.0 4.8 4.1 3.2 3.3 4.2

Source: 1.OECD, Main Science and Technology Indicators, 2005

2.National Science Council, Indicators of Science and Technology R.O.C., 2004 Note: The Sector classification is in accordance with Frascati Manual, OECD

2. In Taiwan, the average citation times of scientific or technical literature in each patent (“current impact index”, CII) are lower than for other main countries, with a sustained downward tendency. 3. The proportion of foreign R&D investment in Taiwan’s market is much lower than for other main countries.

Table 3.13 : The patent strength of Invention Patents granted in the US, 2003-04

2003 2004

PN PN/MPOP CII PS PN PN/MPOP CII PS

Total 169,028 -- 1.00 169,028 164,413 -- 1.00 164,413 USA 87,901 299 1.18 103,528 84,340 287 1.18 99,393 Japan 35,517 279 0.89 31,625 35,396 278 0.90 31,855 Germany 11,444 139 0.61 6,990 10,770 131 0.59 6,405 Taiwan 5,298 234 0.88 4,676 5,938 263 0.85 5,063 Canada 3,426 109 0.92 3,151 4,428 93 0.85 3,781 Korea 3,944 83 0.79 3,108 3,373 107 0.95 3,220 UK 3,627 61 0.76 2,742 3,444 58 0.80 2,740 France 3,869 64 0.61 2,363 3,386 56 0.56 1,893 Israel 1,193 186 1.15 1,374 1,031 160 1.11 1,148 Sweden 1,521 171 0.80 1,218 1,292 145 0.79 1,020 China 297 0.23 0.70 209 403 0.31 0.76 305

Source: USPTO CD-ROM, TIER Calculated

Notes: 1. The country in residence of the first inventor determines country of patent.

2. CII (Current Impact Index) is the citation frequency ratio of a country’s patents granted in previous 5 years cited by current year patent relatives to the citation frequency ratio of all patents.

3. PS (Patent Strength) is calculated by multiplying the number of a country’s US patents by its current-impact index

Table 3.14: Patents granted in USA and mutual citations, 1996-2004

Enterprise Government R&D

Institute University Individual Assignee Total

1996 741 50 126 2 1,496 2,415 1997 846 63 173 1 1,496 2,579 1998 1,432 86 238 -- 2,020 3,776 1999 2,072 77 231 2 2,168 4,550 2000 3,179 66 231 2 2,462 5,940 2001 3,671 79 259 2 2,628 6,639 2002 3,752 53 281 5 2,770 6,861 2003 3,950 27 261 16 2,662 6,916 2004 4,845 21 241 50 2,441 7,598

Citations (excluding Citations by Foreigners)

Enterprise 19,024 30 155 4 3,090 22,303 Government 617 12 247 2 71 949 R&D Institute 76 80 12 11 13 192 University -- -- 2 4 -- 6 Individual 4,204 13 43 10 13,590 17,860 Total 23,921 135 459 31 16,764 41,310

4. The numbers of patents in universities applied for and applied by enterprises are quite low, which shows that the degree of commercialization of research results in universities is relatively low, and unable to attract the interest of industry.

In sum, Taiwan’s absolute R&D investment reached US$13.668 billion in 2003, 11th in the world; average growth rate was 8.32% from 1995 to 2003, behind only China, South Korea, Israel, Russia and Finland; R&D intensity was 2.45% (2.33% in new GDP of 93SNA) in 2003, 11th among all participating countries. These obvious data all show Taiwan’s R&D investment is not bad. Taiwan’s industry R&D expenditure is highly concentrated in the ICT industry – up to 66.2%. In the face of the fact that the service sector and new emerging industries are the driving force of economic growth, the government has insufficient funds to invest in R&D, which is really the immediate policy issue the government must pay attention to in the transformation of Taiwan’s industry. The increasing number of Taiwanese R&D personnel from 2001 to 2004 shows that the manpower demand in R&D has increased continuously. Moreover, more than 70% of researchers who have a PhD degree are located in universities; only 10-11% of researchers in industrial circles. The patent output is not bad on the whole but is mainly concentrated in industrial circles; in academic circles it is very limited and less recommended by industries, which reveals that knowledge interactions between industries and universities have a gap.

4. Major industrial policies and governance 4.1 Existing industrial policies

4.1.1 Tax credits for R&D and personnel training

The MOEA is chiefly responsible for industrial technology research and its application. Apart from the MOEA’s directly subordinate research units, the R&D department of state-owned enterprises and independent research institutes undertaking commissioned projects are also engaged in industrial R&D and technology transfer. Research institutes are employing technology acquisition, joint research, foreign direct investments and strategic alliances to interact with foreign companies, and research institutes as mechanisms to accelerate the industry’s technological development. In addition, the government relies on administrative measures like subsidies, matching grants and investment tax incentives to encourage industry to engage in R&D activities.

4.1.2 Small Business Innovation Research

In accordance with the Knowledge Economics Development Act, the Department of Industrial Technology (DoIT) of Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) launched Taiwan’s SBIR promoting program, mostly referring to the US version of the SBIR, in Nov. 1998, in order to enhance the private sector’s R&D competitiveness through promoting technological innovation and utilizing Information Technology on one side, and providing tax incentives and a subsidy of up to half of the

cost of development and matching funds to resolve market failures and uncertainties of technology development on the other side.

The types of research encouraged by this programme include: 1) Developing a brand new idea, concept or new technology; 2) Applying an existing technology to a new application; 3) Applying a new technology or business model to an existing application; 4) Improving an existing technology or product upon various aspects. By 2010, the SBIR promoting programme may assist in achieving the nationwide goal of Taiwan’s R&D rising to 3% of GDP; and private sector R&D increases up to 60%, including 70% from knowledge-based industries.

4.1.3 Technology Development Programs

The Department of Industrial Technology (DoIT) is Taiwan’s science and technology development flagship. Its primary mission is to promote industrial technology development to help create new national industries and help upgrade Taiwan’s existing industries. Therefore, in cooperation with the Executive Yuan’s promotion of the “scientific and technical development scheme”, the government began to implement “the given-case program of MOEA scientific and technological research development” in 1979 (TDP for short). The DoIT takes charge of examining and allocating the subvention funds as the main overall promotion unit of scientific and technological given cases. In the initial stage of planning, the contracted research institution (TDP-contracted Research Institutes for short) is authorized to assist in industrial innovation, introduce each perspective, critical and compatible technology, and to bring about the cooperation between manufacturing and studying in order to help industries upgrade and change their type, strengthen their innovative R&D abilities, and increase their international competitiveness. To sum up, TDP-contracted Research Institutes are to adjust domestic industries to R&D innovation and prospective technology. On the contrary, the non-profit research institutes, involving DoIT contracts with the private sector and academic organizations respectively, carry out and develop basic and pioneer technologies that are then licensed to Taiwan’s industries.

The major goals of this TDP are as follows:

1. To implement focused national research projects.

2. To direct non-profit research institutes to conduct “industry-demand” oriented research projects. 3. To develop a national science & technology innovation system.

4. To use electronic invoices (e-invoices) to integrate supply chain logistics with cash-flow system technologies.

5. To promote the development and use of innovative value-added services from patents owned by non-profit research institutes.

6. To promote the dissemination and use of imported technology, thereby supporting domestic research momentum.

7. To coordinate and fund joint research ventures between domestic and international universities. 8. To integrate university research findings with industrial development.

parks that complement local characteristics.

10. To facilitate innovative industrial technology development with resources from the TDP.

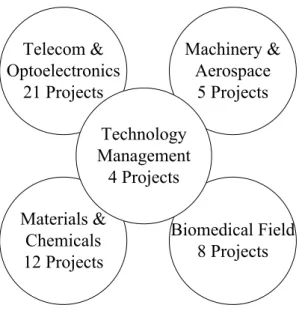

Table 4.1: TDP expenditures 2001/04

Fields of R&D 2001 2002 2003 2004

Telecom & Optoelectronics (23.63%)37.48 (25.37%) 35.73 (19.26%) 34.85 Machinery & Aerospace (19.3%)30.62 (18.54%) 26.10 (14.61%) 26.44 Materials & Chemicals (14.41%)22.86 (18.64%) 26.25 (14.84%) 26.85

Biomedical (8.89%)14.11 (12.88%) 18.14 (10.07%) 18.23

Pioneer Innovation program (20.50%)32.52 (24.56%) 34.58 (10.95%) 19.81

Others (9.42%) 17.04

TDP for Corporation (89.4%)135.64 (86.73%)137.59 (81.93%) 140.81 (79.14%) 143.22 TDP for Private Sector (10.6%)16.08 (12.32%)19.55 (15.91%) 27.35 (17.03%) 30.82

TDP for Academia (0%)0 (0.95%)1.5 3.72(2.16%) 6.94 (3.83%)

Total 151.73 158.64 171.88 180.98

Unit: NT$ million

Source: DoIT/MOEA (2005)

4.1.3.1 TDP for Research Institutes

Table 4.2: Research Institutes, TDP Performance and Benefits (2001-2004)

2001 2002 2003 2004

R.O.C Patent Granted (cases) 634 499 508 850

Overseas Patent Granted (cases) 305 344 289 363

Patent Applications (cases) 160 500 450 513

R.O.C Technical Paper (articles) 1132 1474 1701 1807

Overseas technical Paper (articles) 334 343 489 720

Technical Reports (articles) 4395 4573 4774 4791

Technology Introduction (cases) 129 54 51 73

Technology Transfer (cases) 954 1071 1061 1184

Project Subcontract (cases) 533 573 622 780

Contracts and Industrial Services (cases) 1381 1728 1595 1969

Enterprise Investments (cases) 483 542 618 630

Technical Conferences (numbers) 623 788 871 763

Source: Annual Report of Technology Development Program , MOEA, 2001-2004

Taiwan’s industry consists of mainly SMEs running on limited capital, so beginning in the 1970s, the government established a series of technology research institutions, the most important of which

is the Industrial Technology Research Institute, responsible for carrying out innovative R&D in key common industrial technologies. Furthermore, it was responsible for implementing the MOEA’s TDP in 1979. The objectives of the TDP include stimulating industrial technology development and consolidating industry competitiveness, while assisting research institutions in their roles of industrial technologies. Thus, for a long time R&D has been delegated to Industrial Technology Research Institute, Institute for Information Industry and Chung-shan Research Institute of Science and Technology, etc., and then the technological achievements transferred to the private sector.

4.1.3.2 TDP for the Private Sector

DoIT/MOEA launched a serious of technology research programmes for the private sector in 1997. The TDP was opened to state enterprises, which could also apply for contract research, so long as they were certified for qualified research management. The second wave of the TDP for Private Sector was strengthened in 1999. The TDP became available to private sector enterprises, provided that private firms supplied matching funds.

These programmes allow direct government support to be given to the private sector in an effort to stimulate overall industrial research. The goal of this programme is to use such research to help upgrade and transform Taiwanese industries. DoIT has developed a broad range of industrial R&D support programmes, allowing the private sector greater ability to select appropriate support from the government. Furthermore, the private sector can share in the intellectual property rights generated by research results. Current ongoing programmes are described below (DoIT website, 2005). For details of Industrial Research & Development Programmes (see Appendix 2).

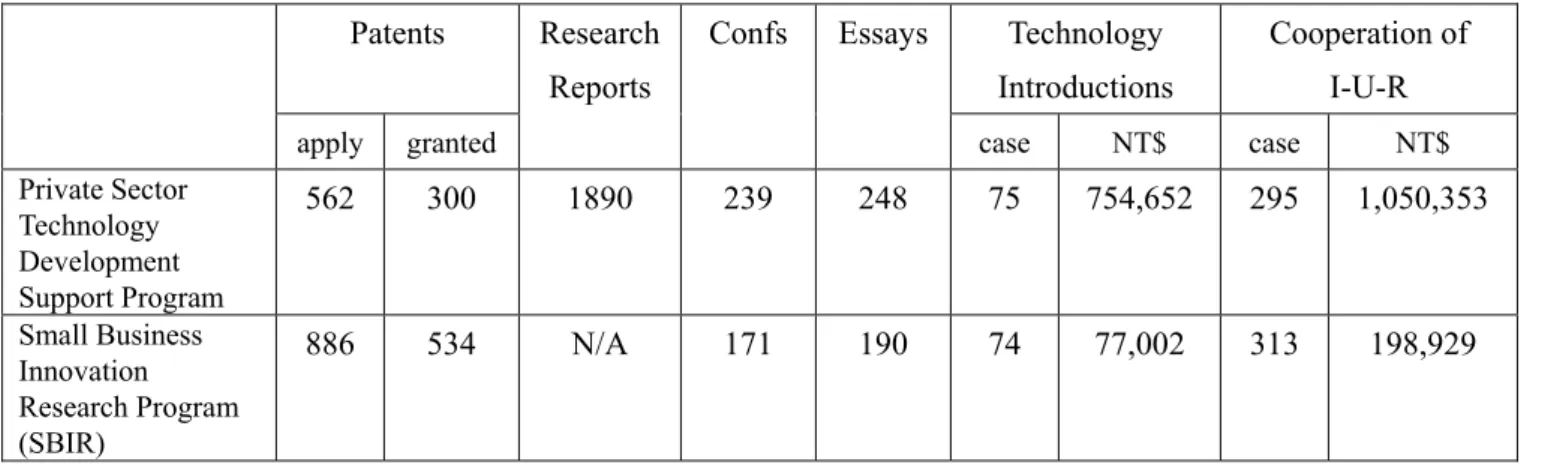

Table 4.3: TDP for the Private Sector, 1999-2004

Patents Research Reports

Confs Essays Technology

Introductions

Cooperation of I-U-R

apply granted case NT$ case NT$

Private Sector Technology Development Support Program 562 300 1890 239 248 75 754,652 295 1,050,353 Small Business Innovation Research Program (SBIR) 886 534 N/A 171 190 74 77,002 313 198,929 Source: TDP Yearbook 2004 (2005) 4.1.3.3 TDP for Academia

The “TDP for Academia” was launched in 2001 and began accepting contract research applications from universities in which basic academic research resources could be integrated to develop innovative, pioneering industrial technology. Academia has traditionally had very weak long-term integrated research projects, not to mention poor results in developing industrial technology. DoIT