國中學生接受聽力策略訓練後聽力策略發展之研究 - 政大學術集成

118

0

0

全文

(2) An Investigation of Junior High School Students’ Listening Strategies Development after Explicit Listening Instruction. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English,. n. al. y. er. io. sit. Nat. National Chengchi University. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Yu-Hsin Feng June, 2014.

(3) To Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh 獻給恩師葉潔宇教授. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i Un. v.

(4) Acknowledgements First of all, I want to show my deepest thanks to my advisor, Dr. Chieh-Yue Yeh. Without her warm encouragement and brilliant comments, I could not complete this thesis. Also, I would like to express my gratitude to the committee members, Dr. Dex Chen-Kuan Chen and Dr. Chin-chi Chao for their cherish advice and careful reading of the manuscript. Moreover, I would like to thank my dearest husband, my mom, and my two lovely. 政 治 大. children. Were it not for your support, I could not complete my study. I love you all.. 立. Last but not least, thank those who have helped me during the journey of thesis writing.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i Un. v.

(5) Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………. v Chinese Abstract………………………………………………………………….. I English Abstract……………………………………………………………………III Chapter One: Introduction………………………………………………………1 Background and Motivation…………………….. ……………………………..1 Purpose of the Study……....................................................................................3 Research Questions..............................................................................................3. 政 治 大 Listening Process……………….........................................................................5 立. Chapter Two: Literature Review……………………….....................................5. Top-down Processing..........................................................................................5. ‧ 國. 學. Bottom-up Processing.........................................................................................6. ‧. Interactive Processing.........................................................................................7. sit. y. Nat. Language Learning Strategies and Listening Strategies.....................................8. io. er. Strategy-based Instruction .................................................................................10. al. iv n C The Effectiveness of Explicit h Strategy e n gInstruction..............................................14 chi U n. The Model of Explicit Strategy Instruction…………………………………….10. Chapter Three: Methodology…………………………………………………..17 Participants ........................................................................................................17 The Listening Section of GEPT Elementary Level ............................................17 Teaching Materials…………………………………………………………….18 Reflective Journal...............................................................................................19 Strategy Classification Scheme..........................................................................20 Treatment...........................................................................................................20 Listening Strategies List.....................................................................................20 v.

(6) Procedure...........................................................................................................23 Pilot Study..........................................................................................................24 Main Study.........................................................................................................24 Data Analysis.....................................................................................................25 Chapter Four: Results…………………………………………………………...27 Students’ Strategy Use......................................................................................27 Metcognitive Strategies Use in Listening..........................................................31 Metcognitive Strategies Use in Listening—Quantitative Analysis………........31 Sub-strategies of Planning...........................................................................34. 治 政 Sub-strategies of Monitoring………...........................................................35 大 立 Sub-strategies of Evaluation………............................................................37 ‧ 國. 學. Metcognitive Strategies Use in Listening—Qualitative Analysis………..........40. ‧. Cognitive Strategies Use in Listening...............................................................42. sit. y. Nat. Cognitive Strategies Use in Listening—Quantitative Analysis………………..42. io. er. Sub-strategies of Top-down Strategies........................................................46. al. Sub-strategies of Bottom-up Strategies………...........................................49. n. iv n C Sub-strategies of Cognitive Other h eStrategies……………………………..52 ngchi U. Cognitive Strategies Use in Listening –Qualitative Analysis…………………56 Social and Affective Strategies Use in Listening………………………….....59 Social and Affective Strategies Use in Listening—Quantitative Analysis……59 Chapter Five: Discussion…………………………………………………….....65 Chapter Six : Conclusion…………………………………………… …………75 Summary of the Major Findings……………………………………………75 Quantitative Findings……………………………………………………….75 Qualitative Findings………………………………………………………...77 Pedagogical Implications…………………………………………………...77 vi.

(7) Limitations of the Present Study and Suggestions for Future Research…78 Reference……………………………………………………………….79 Appendix A…………………………………………………………......87 Reflective Journal………………………………………………………..87 Appendix B …………………………………………………………….90 Listening Strategies Classification Scheme……………………………..90 Appendix C…………………………………………………………….100 Listening Strategy List………………………………………………….100. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v.

(8) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i Un. v.

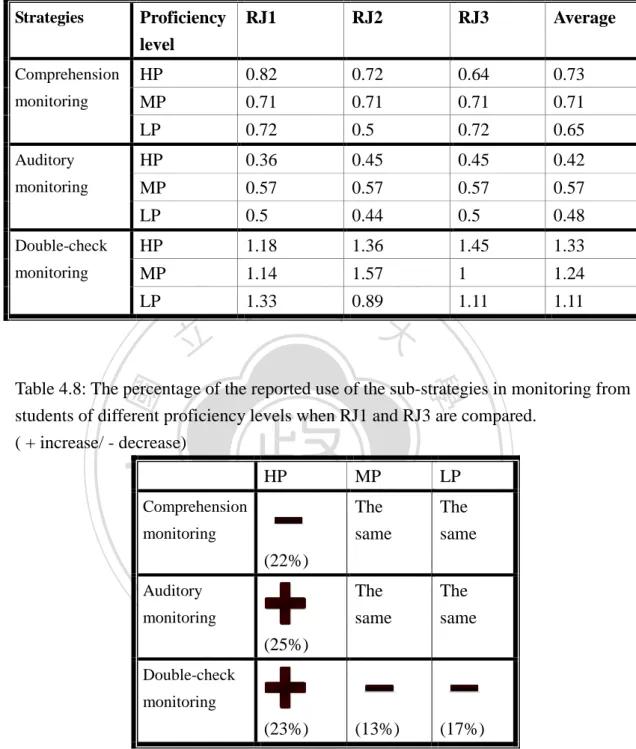

(9) List of Tables Table 2.1 Models for Language Learning Strategy Instruction…………………12 Table 4.1 The frequency and mean of metacognitive strategies, cognitive strategies and social and affective strategies use reported from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………………………30 Table 4.2 Metacognitive strategy reported use from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………………………………………….32 Table 4.3 The mean of the reported use of the sub-strategies in planning reported by students from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………………33. 治 政 大in planning reported by Table 4.4 The mean of the use of the sub-strategies 立 students of different proficiency levels from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……..34 ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.5 The percentage of the reported use of the sub-strategies in planning. ‧. from students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are. sit. y. Nat. compared…………………………………………………………………35. io. er. Table 4.6 The mean of the reported use of the sub-strategies in monitoring. al. reported by students of the three groups from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…..36. n. iv n C Table 4.7 The mean of the reported of the sub-strategies in monitoring h e nuse gchi U. reported by students of different proficiency levels from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………………………………………………………………..37 Table 4.8 The percentage of the reported use of the sub-strategies in monitoring from students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are compared…………………………………………………………………37 Table 4.9 The mean of the reported use of the sub-strategies in evaluation reported by students from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………………38. ix.

(10) Table 4.10 The mean of the reported use of the sub-strategies in evaluation reported by students of different proficiency levels from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……………………………………………………………….39 Table 4.11 The percentage of the reported use of the sub-strategies in evaluation from students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are compared………………………………………………………………39 Table 4.12 The mean of the cognitive sub-strategies use reported from students of the three proficiency levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………..42 Table 4.13 Cognitive strategies use reported from students of the three. 治 政 大 proficiency levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……………………………..43 立 Table 4.14 The percentage of the reported use of cognitive sub-strategies from ‧ 國. 學. students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are. ‧. compared………………………………………………………………45. sit. y. Nat. Table 4.15 The mean of cognitive top-down strategies use reported from students. io. er. of different proficiency levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………..46. al. Table 4.16 The mean of the use of cognitive top-down strategies reported by. n. iv n C students of different proficiency in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……..47 h e nlevels gchi U. Table 4.17 The percentage of the use of the sub-strategies in top-down strategies from students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are compared………………………………………………………………48 Table 4.18 The mean of the cognitive bottom-up strategies use reported from students of different proficiency levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……..50 Table 4.19 The mean of the use of cognitive bottom-up strategies reported by students of different levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………..51. x.

(11) Table 4.20 The percentage of the reported use of the sub-strategies in bottom-up strategies from students of the three groups when RJ1 and RJ3 are compared…………………………………………………………………52 Table 4.21 The mean of the cognitive other strategies use reported from students of different proficiency levels in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………53 Table 4.22 The mean of the use of cognitive other strategies reported by students of different proficiency levels from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………55 Table 4.23 The percentage of the use of cognitive other strategies from students of different proficiency levels when comparing RJ1 and RJ3……….55. 治 政 大 from students of the three Table 4.24 The mean of social strategies use reported 立 groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3…………………………………………..60 ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.25 The mean of affective strategies use reported from students of the. ‧. three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……………………………………60. sit. y. Nat. Table 4.26 The mean of social sub-strategies use reported from students of the. io. er. three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3……………………………………61. al. Table 4.27 The mean of affective sub-strategies use reported from students of the. n. iv n C three groups in RJ1,hRJ2 and RJ3……………………………………61 engchi U. Table 4.28 The percentage of the use of social and affective strategies from students of different proficiency levels when comparing RJ1 and RJ3 …………………………………………………………………………..62. xi.

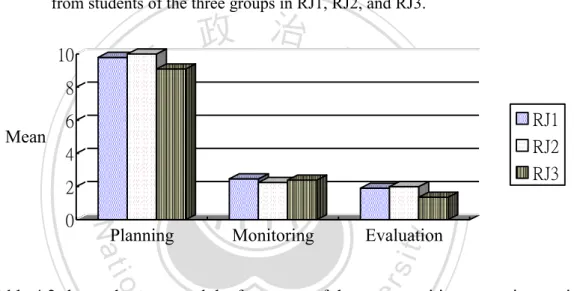

(12) List of Figures Figure 3.1 Procedure of the study………………………………………………….23 Figure 4.1 The mean of metacognitive sub-strategies use reported from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3………………………………31 Figure 4.2 The mean of the reported use of social and affective strategies in the three stages of LSI………………………………………………………..59. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xii. i Un. v.

(13) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱: 國中學生接受聽力策略訓練後聽力策略發展之研究 指導教授: 葉潔宇教授. 立. 研究生: 馮羽欣. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 論文提要內容:. ‧. 本研究旨在探討國中學生在接受為期十二周的聽力策略訓練(LSI)之後,其後. sit. y. Nat. 設認知、認知、社會情感策略的使用和發展以及了解國中學生聽力策略學習的過. io. er. 程。研究對象為36名北部國中七年級學生。其中,後設認知策略和認知策略將在 課堂上明確的(explicitly)教導;而社會情感策略則是暗示的(implicitly)教導。從. al. n. iv n C 反思日記中所收集的資料以質化和量化的方式分析。量化資料以SPSS 11.5 hengchi U. 來做. 描述統計分析;而質化資料則以逐字稿打出並由研究者和另一名英文老師來做分 析與歸類的工作。 研究結果顯示後設認知策略和社會情感策略的使用減少,而認知策略的使用增 加。此外能力高低與策略使用的次數並沒有絕對的對應。另外,學生可以在策略 訓練的過程中發展出自己的策略。最後,策略的使用十分的個人化與複雜。根據 研究發現,本研究提出三點對於國中英文聽力教學上的建議。第一,聽力策略訓 練可以與國中英文課程做結合。第二,教導學生聽力策略的同時,應要求學生寫 反思日記。最後,不應強迫學生在聽力策略上的使用方式,因為聽力策略的使用 個別性很高。 XIII.

(14) 關鍵字:聽力策略學習過程、聽力策略訓練、聽力策略、國中生. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. XIV. i Un. v.

(15) Abstract This study aimed to investigate students’ listening strategy learning process and their metacognitive, cognitive, and social/affective strategies utilization as well as development after listening strategy instruction(LSI). The subjects were 36 seventh graders in junior high school in northern Taiwan. These students were taught listening strategies for twelve weeks. Metacognitive strategies and cognitive strategies were. 治 政 taught explicitly while social/affective strategies were 大taught implicitly. The data from 立 reflective journals were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. The ‧ 國. 學. quantitative data were analyzed by the SPSS version 11.5 for the descriptive statistics,. ‧. while the qualitative data from reflective journals were transcribed verbatim and. sit. y. Nat. categorized into the themes by the researcher and another English teacher.. io. er. The result showed the reported use of metacognitive strategies and social/affective. al. strategies reduced with time, whereas the reported use of cognitive strategies. n. iv n C increased. Meanwhile, the students’ levels did not correspond to the h e proficiency ngchi U frequency of strategies use. Besides, students developed strategies that had not been emphasized in LSI. Moreover, students changed their roles from passive learning to active thinking and became better able to apply a wide range of strategies after LSI. Last, it was found that strategy use is highly individualized and complex. Based on these findings, some pedagogical implications were suggested. First, LSI can be integrated in EFL classroom in junior high school. Next, it is important to teach students listening strategies as well as ask them to write reflection journal at the same time. Last, it is better not to force students to use some specific strategies at specific time because strategy use is highly individualized. XV.

(16) Key words: listening strategy learning process, listening strategy instruction (LSI), listening strategies, junior high school student. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. XVI. i Un. v.

(17) Chapter 1 Introduction Background and Motivation With the globalization of society, English is used as a lingua franca in the world, and we have more and more chances to access rich variety of aural and visual English texts through world-wide communication systems like Facebook, Youtube, Twitter,. 政 治 大. and others. Thus, English listening comprehension has been more and more important. 立. for ESL/EFL learners because being unable to comprehend spoken English may cause. ‧ 國. 學. communication breakdown or non-understanding. Besides, English listening test will be included in Taiwan Certificate of Education Examination (國中會考) in 2014.. ‧. Therefore, it is imperative for teachers to put more time and effort in listening. y. Nat. io. sit. instruction to enhance students’ listening ability.. n. al. er. Over the decades, the foci of listening teaching have changed from perception and. Ch. i Un. v. decoding of sounds to the use of listening strategy for enhancing comprehension and. engchi. dealing with problems (Goh, 2008). Listening strategy instruction (LSI) which includes cognitive strategies, metacognitive strategies, and social and affective strategies have been proved to be beneficial for listening comprehension especially for weaker listeners (Chamot, 2004; Goh & Taib, 2006; Huang, 2008; Hung, 2010; Li, 2009; You, 2007). Cognitive strategies include bottom-up strategies such as listening for key words and listening for details and top-down strategies such as inference and elaboration. Research has shown that an integrative model of top-down and bottom up strategies facilitate listening comprehension the most (Nunan, 2003; Vandergrift, 2004). 1.

(18) Though cognitive strategies help learners increase listening comprehension, the process of strategy use and the way learners can use the strategies by themselves were scarcely discussed; as a consequence, learners do not develop the competence to use strategies by themselves without teachers’ guidance. In other words, they cannot become independent learners. Scholars like Vandergrift, Chamot, and Goh advocated metacognitive strategies involving thinking about and directing the listening process. Through metacognitive strategies comprising planning, monitoring, and evaluation, learners can be helped to know when and how to use strategies that best work for them; thus, learners turn to be active and gain more autonomy in learning. While. 治 政 metacognitive strategies may direct listening activity, their大 directive power cannot 立 realized without the application of appropriate cognitive strategies (Vandergrift, ‧ 國. 學. 2008).. ‧. Social and affective strategies are the least frequently used by students (Wharton,. sit. y. Nat. 2000), and those who need them the most are least likely to use them because of not. io. er. viewing social relationship as part of the L2 learning process and for the lack of. al. awareness of their own feelings (Oxford, 1993). However, Dornyei (2005) suggested. n. iv n C that sharing with peers the strategies use the most inspiring part of strategy h iseoften ngchi U instruction because students can gain insights from their peers by listening to the experience of each other.. Though many studies have suggested the benefit of LSI, their research method lies in the quantitative analysis of the grades between pre-test and post-test (Huang, 2008; Hung, 2010; Li, 2009; You, 2007). Therefore the result of the study cannot show how learners arrived at comprehension. Besides, learners also suffer from a high level of anxiety under the emphasis of the product—the right answer and the grades (Vandergrift, 2008). Therefore, the attention of the study should be directed to the process of listening strategy learning. After all, not until learners become aware of 2.

(19) their listening strategies development will they know how to orchestrate their strategies and control comprehension processes on their own (Vandergrift, 2008). Therefore, a closer investigation of how students learn and adjust their listening strategies under the strategy instruction is worthy of attention. Purpose of the Study What is of particular interest to this study is that little research has been conducted to see the development of students’ listening strategies after LSI. Besides, the focus of much research lies in the quantity of strategies teaching rather than the quality of how students learn the strategies under strategy instruction. Goh (2002) indicated what. 治 政 differentiates high proficiency learners and low proficiency 大 learners is not the number 立 of strategies they use but how they orchestrate their strategies. Therefore, the ‧ 國. 學. researcher intends to offer a picture of students’ strategy learning process and their. sit. y. Nat. Research Questions. ‧. strategies utilization and development after LSI.. io. er. To present the process of students’ strategy learning under LSI, two research. al. questions are addressed as follows.. n. iv n C How do students adjust their strategies after listening strategy h elistening ngchi U. 1.. instruction (LSI)? 2. What’s the development of students’ metacognitive, cognitive, and social and affective strategies in listening after students received listening strategy instruction (LSI)?. 3.

(20) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 4. i Un. v.

(21) Chapter Two Literature Review Three major sections are presented to review literature on students’ listening strategies development after listening strategy instruction (LSI). The first section is about listening process including top-down processing, bottom-up processing, and interactive processing. The second part involves the introduction of learning and listening strategies. Finally, the models of the strategy instruction and the. 治 政 effectiveness of the instruction are discussed. 大 立 Listening Process ‧ 國. 學. To understand how people comprehend what they hear, it is important to think. ‧. about how people process the sound. Three dimensions are often mentioned to explain. the other is interactive processing.. io. al. Top-down Processing. er. sit. y. Nat. listening process; one is top-down processing; another is bottom-up processing, and. n. iv n C Learners comprehending what hear in top-down processing start with their h ethey ngchi U background knowledge or schemata to get a general view of the listening passage and then infer to come up with a plausible explanation (Nunan, 2003). However, the effectiveness of top-down processing in benefit of listening comprehension is controversial. Some studies suggested that top-down processing fosters listening comprehension (Ellermeyer, 1993; Kelly, 1991; Meyer & Rice, 1983). Kelly (1991) found that skilled listeners applied top-down processing more whereas less- skilled listener attend mostly to local details as in the bottom-up processing. Nevertheless, some studies indicated that schemata in top-down processing may hinder listening comprehension (Long, 1989; Tsui & Fullilove, 1998). Long (1989) 5.

(22) found that linguistic knowledge plays a critical role in comprehension when appropriate schema are not activated to listeners , which leads listeners to draw on the wrong schema. Implications of top-down process in English teaching are more concerned with the activation of schema (Brown, 2007). Techniques include ways to activate schema prior to a listening activity, to listen to identify a topic or find main idea and supporting details. Techniques before the listening activity involve providing questions to discuss the topic and offering pictures or keywords about the text (Brown, 2007).. 治 政 Bottom-up Processing 大 立 Learners comprehending what they heard in bottom-down processing start with ‧ 國. 學. analyzing the various morphosyntactic elements of linguistic input from sounds to. ‧. lexical meaning, and to find final accurate message (Brown, 2007). When listeners. sit. y. Nat. have no background knowledge about the discourse, they rely much on bottom-up. io. er. processing (Wilson, 2003). According to Kelly (1991), in the early stage of foreign. al. language learning, learners tend to use bottom-up processing. As their proficiency. n. iv n C increased, they count more on semantichand other knowledge e n g c h i U belonging to top-down processing. The effectiveness of bottom-up processing is also controversial. Some studies indicated that top-down processing facilitate listening comprehension more (Kelly, 1991; Vandergrift, 1997; Weissenrieder, 1987) whereas other studies suggested successful listening comprehension rely more on bottom-up processing because schema may cause dysfunctional effects on listening comprehension (Long, 1989; Tsui & Fullilove, 1998). Tsui and Fullilove (1998) suggested that if listeners are not able to revise their initial activated schema which contradicts the following text, they cannot comprehend successfully. Therefore, the study proposed that less-skilled 6.

(23) listeners need to master rapid and accurate decoding of he linguistic inputs and count less on guessing from background knowledge to avoid the misleading of the wrong background knowledge. Implications of bottom-up processing in English teaching focus on sounds, words, intonations, grammatical structures, and other components of spoken language. Techniques in bottom-up processing involve listening for key words, listening for details and dictation exercises—that is, learners write exactly what they hear (Brown, 2007). Interactive Processing. information and their prior knowledge (Nunan, 2003).. 學. ‧ 國. 治 政 The use of the combination of top-down and bottom-up 大 data is called interactive 立 processing with which learners modify their interpretation according to both incoming ‧. Some studies indicated that effective listening comprehension occurs when the. sit. y. Nat. listeners can orchestrate the incoming linguistic information and their pre-existing. io. er. knowledge to constantly modify their hypothesis (Kelly, 1991; Buck, 1991). Hildyard. al. and Olson (1982) indicated that efficient learners utilize both top-down and. n. iv n C bottom-up processing to interpret low-level learners pay more attention h etextnwhereas gchi U to local details. In the classroom, pre-listening activities can help learners to use the interactive mode to process the discourse (Nunan, 2003). For example, before listening, teachers can ask learners to brainstorm vocabulary about the following topic or create a short dialogue related to functions in the following discourse, which facilitate students to activate schema (top-down processing). During the listening, they base their information generated from pre-listening activities to comprehend vocabulary and sentences in the discourse (bottom-up data).. 7.

(24) Language Learning Strategies and Listening Strategies Language learning strategies can be defined as actions, thoughts, or processes which are consciously selected by learners to assist them in learning and using language or to complete a language task (Cohen,2011; White, 2008). From the mid1970s, influenced by interactionist and sociolinguistic, the language teaching emphasis moved from a product-oriented to a process-oriented. In other words, the teaching concern shifted from methods and products of language teaching to a focus on how language learners process, store, retrieve and use target language material (White, 2008). One dimension of this research included attempts to find out how. 治 政 language learners learn effectively and improve their language 大 competence through 立 the orchestration of various learning strategies. ‧ 國. 學. Such learning strategies have been classified in different ways. In Cohen’s study. ‧. (2011), three dimensions of learning strategies are mentioned, strategies for learning. sit. y. Nat. and use, strategies according to skill area, and strategies according to function. What. io. er. is of particular interest to this study is the application of listening strategies consisting. al. metacognitive, cognitive, and socio-affective strategies in unidirectional tasks.. n. iv n C Therefore, the second and third dimensions more related to this study and will be h e are ngchi U further elaborated. The second dimension involves strategies according to skill area. In this approach, strategies are classified in related to their roles in four skills—listening, reading, speaking, and writing. The present study focuses on listening; some strategies like vocabulary, grammar, and translation strategies can also be applied to the listening skill. The third way to classify strategies is to concern strategy functions, namely metacognitive, cognitive, and socio-affective (Chamot, 1987; Oxford, 1990). Metacognitive strategies in listening include pre-listening planning, while-listening 8.

(25) monitoring, and post-listening evaluation and problem-solving, which facilitate learners to think about and direct the listening process. Metacognitive strategies are considered valuable in which they allow learners to reflect on the process of listening by planning, monitoring, and evaluating on a given task; thus, learners’ awareness and strategic knowledge can also be encouraged (Vandergrift, 2008). Studies of the differences between more-skilled and less-skilled listeners highlight the importance of metacognitive strategies to L2 listening success (Goh, 2000; Goh, 2002b; Vandergrift, 1998; Vandergrift, 2003). Goh (2002b) indicated that skilled L2 listening involves a skillful orchestration of selected metacognitive and cognitive. 治 政 strategies to monitor listening process and comprehend 大 the input. Vandergrift (2003) 立 also found skilled listeners used about twice as many metacongnitive strategies as ‧ 國. 學. their less-skilled counterparts and used an effective combination of metacognitive and. ‧. cognitive strategies.. sit. y. Nat. Though metacognitive strategies are important in terms of facilitating listening. io. er. comprehension, their power cannot be exerted without the application of appropriate. al. cognitive strategies. Therefore, learners should learn to couple both metacongnitive. n. iv n C and cognitive strategies well to h achieve successfulU e n g c h i comprehension (Vandergrift, 2008).. Cognitive strategies deal with strategies with which learners use during the process of language learning and language using to help them comprehend. These strategies involve solving learning problems by considering how to store and retrieve information. Besides, they are more limited to specific learning tasks and involve more direct manipulation of the learning material itself (Brown, 2007). Many studies indicated that more proficient listeners put greater emphasis on elaboration and inference than less proficient learners. Besides, more proficient listeners use strategies more flexibly whereas the less proficient listener depends more 9.

(26) on the text and a consistent use of paraphrase (Murphy, 1985; O’Malley et al.,1989; Vandergrift, 1998). Social and affective strategies encompass social strategies and affective strategies. Social strategies consist of the ways applied by learners to interact with other learners and affective strategies are used to reduce learners’ anxiety and provide self-encouragement. Besides, they can also help regulate learners’ emotions, motivation, and attitudes (White, 2008). Social and affective strategies are the least frequently used by students (Wharton, 2000); however, DÖ rnyei (2005) suggested that sharing with peers strategies use is. 治 政 often the most inspiring part of strategy instruction because 大students can gain insights 立 from their peers by listening to the experience of each other. ‧ 國. 學. The role of affection in listening is seen as multidimensional overlapped and related. ‧. with cognition (Arnold, 1999). For example, strong motivation tends to help students. sit. y. Nat. pursue better skills whereas low motivation or intense anxiety hinder their ability to. io. er. use their skills and abilities. The integral relationship between cognition and affection. al. offers a sound basis for arguing that affective strategies are as strongly implicated in. n. iv n C successful language learning as cognitive strategies (Hurd, 2008). h eandnmetacognitive gchi U Strategy-based Instruction The Model of Explicit Strategy Instruction A number of models for teaching learning strategies in both first and second language contexts have been developed (Cohen, 1998; Graham & Harris, 2003; Grenfell & Harris, 1999; O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Oxford, 1990). These instructions share many features (Chamot, 2005). First, they all agree that students’ metacognitive understanding of the values of learning strategies is important. Next, they all suggest that teachers should demonstrate and model the strategies to 10.

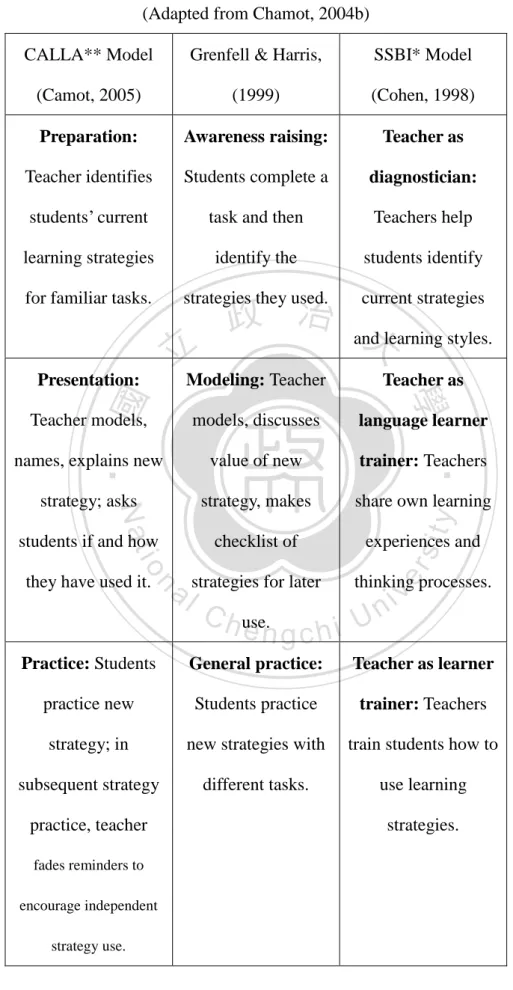

(27) give students concrete ideas of strategy using. Third, they all emphasize the multiple practice opportunities with the strategies are needed so that students can use them flexibly. Moreover, they all suggest that students should evaluate what strategy will best work for them to a task and actively transfer strategies to new tasks. Table 2-1 compares three current models for language learning strategy instruction: the first one is the CALLA model; the second one is the Grenfell and Harris (1999) model, and the last one is The SSBI model. All three models begin by raising students’ strategic awareness by activities such as completing questionnaires, engaging in discussions about familiar tasks, and. 治 政 reflecting on strategies used immediately after performing 大 a task or by teachers’ 立 demonstration with a task and the think-aloud procedures. The steps in these models ‧ 國. 學. may be recursive or linear. The CALLA model is recursive rather than liner so that. ‧. teachers and students always have the option of revisiting prior instructional phrases. sit. y. Nat. as needed (Chamot, 2005) whereas the Grenfell and Harris (1999) model has students. io. er. work through a cycle of six steps, and then begin a new cycle. The SSBI model. al. (Cohen, 1998) involves teachers’ role during the strategy instruction rather than a. n. iv n C series of steps. It suggested thathteachers should take e n g c h i U on a variety of roles to help. students to choose appropriate strategies best working for them. In assessment stage, the Brenfell and Harris model provides students with an opportunity to verify their initial action plan; the CALLA model, on the other hand, has teachers to assess students’ use of strategies and has students to reflect on their strategy utilization before going on a new task. In summary, current models of language learning strategy instruction focus on developing students’ awareness of their strategy utilization, facilitating learners to monitor their own thinking during the process, and encouraging learners to adopt appropriate strategies 11.

(28) Table 2.1 Models for Language Learning Strategy Instruction (Adapted from Chamot, 2004b) CALLA** Model. Grenfell & Harris,. SSBI* Model. (Camot, 2005). (1999). (Cohen, 1998). Preparation:. Awareness raising:. Teacher as. Teacher identifies. Students complete a. diagnostician:. students’ current. task and then. Teachers help. learning strategies. identify the. students identify. for familiar tasks.. strategies they used.. 立. current strategies 治 政 大learning styles. and Teacher as. Teacher models,. models, discusses. language learner. names, explains new. value of new. trainer: Teachers. strategy; asks. strategy, makes. share own learning. students if and how. checklist of. experiences and. ‧ 國. er. io. sit. y. ‧. Nat. a l strategies for later thinking v processes. i n C h use. engchi U. n. they have used it.. 學. Modeling: Teacher. Presentation:. Practice: Students. General practice:. Teacher as learner. practice new. Students practice. trainer: Teachers. strategy; in. new strategies with. train students how to. subsequent strategy. different tasks.. use learning. practice, teacher. strategies.. fades reminders to encourage independent strategy use.. 12.

(29) Self-evaluation:. Action planning:. Teacher as. Students evaluate. Students set goals. coordinator:. their own strategy. and choose. Supervise students’. use immediately. strategies to attain. study plans and. after practice.. those goals.. monitors difficulties. Expansion:. Focused practice:. Teacher as coach:. Students transfer. Students carry out. Provides ongoing. strategies into. action plan using. guidance on. students’ progress. 治 政 大 teacher fades. clusters, develop repertoire of. 立. selected strategies;. prompts so that. 學. ‧ 國. preferred strategies.. students use. ‧. strategies. Evaluation:. io. al. n. Teacher assesses students’ use of. Teacher and students. er. Assessment:. sit. y. Nat. automatically.. ni C hevaluate success U of engchi. strategies and. action plan; set new. impact on. goals; cycle begins. performance.. again.. *Styles and Strategies- Based Instruction ** Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach 13. v.

(30) The Effectiveness of Explicit Strategy Instruction The effectiveness of explicit strategy instruction (ESI) is controversial. Some studies indicate the benefit of ESI (McDonough, 1999; Oxford & Cohen, 1992; You, 2007); some are skeptical of the effectiveness (Gillette, 1994; Schrafnagl & Fage, 1998; Rees-Miller, 1993); still others support the effectiveness of ESI with the combination of awareness of self- regulation ( Goh, 2008; Goh & Taib, 2006; Vandergrift, 2003, 2008). The focus of ESI has been shifted to learners' reflection on their strategy use recently. McDonough (1999) indicated that studies of successful learners should not. 治 政 advocate that less-skilled students should be taught to use 大 skilled-students’ strategies 立 rather being encouraged to look more closely at their own ones. More recently, many ‧ 國. 學. language teaching researchers support McDonough’s view by advocating the. ‧. encouragement of reflection and strategic metacognitive awareness-raising within the. sit. y. Nat. subject context (Benson, 2001; Gog, 2008; Goh & Taib, 2006; Macaro, 2001;. io. er. Vandergrift, 2003, 2004 ). Reflection on the process of listening can raise awareness. al. and help L2 learners develop strategic knowledge for successful L2 learning. n. iv n C (Vandergrift, 2008). Vandergrift (2002)hinvestigated the effect e n g c h i U of ESI on the. development of metacognitive knowledge about listening. While students completed listening tasks, they actively engaged in the major processes underlying listening: prediction, monitoring, problem-solving and evaluation. Students in Vandergrift's study found it motivating to learn to understand rapid, authentic texts, and responded overwhelmingly in favor of this approach to L2 listening. Similar finding is seen in Goh and Taib (2006). This study not only indicated the benefit of the combination of metacognitive but also suggested that weaker listeners appeared to benefit more from this listening instruction. Macaro (2001) indicated that through self-regulation, learners are able to consciously choose appropriate strategies to comprehend a 14.

(31) specific task. Though many studies have suggested the benefit of listening strategies instruction, their research method are mostly related to teaching one or more strategies to students and then using pre-test and pos-test to claim the causal effect between strategies teaching and students' listening improvement. (Huang, 2008; Hung, 2010; Li, 2009; You, 2007). Therefore, the result of the study cannot show students' strategies utilization and their strategies development after strategies teaching. Besides, little research studies students’ reflection on how to learn and what difficulties they may encounter during the process of the instruction, which can. 治 政 provide the researcher an insight into students’ learning 大 process. Therefore, a closer 立 investigation of students' strategies use and how students learn and adjust their ‧ 國. 學. listening strategies under the strategy instruction is worthy of attention. In other words,. ‧. the present study is both quantitative and qualitative in nature.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 15. i Un. v.

(32) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 16. i Un. v.

(33) Chapter Three Methodology The purpose of the study is to offer a picture of students’ listening strategy learning process and their listening strategies utilization and development after listening strategy instruction (LSI). In this chapter, participants, instrument, and the treatment are introduced. Besides, the procedure of how to implement the instruction is illustrated. Finally, how the data was analyzed is presented in the last section.. 立. 治 政Participants 大. One seventh-grade class consisting of 36 EFL students from a public junior high. ‧ 國. 學. school in northern Taipei participated in this study. These students had learned. ‧. English in regular education for six years. They were chosen because of the. sit. y. Nat. practicality and the result of the pre-test. Besides, according to the pre-test, this class. io. al. n. this class was chosen to participate in this study.. Ch. er. had the most low proficiency students, up to 50%, among the five classes. Therefore,. i InstrumentsU n engchi. v. Four instruments were used for different purposes in the experiment including the listening section of GEPT elementary level, teaching materials, one reflective journal, and one strategy classification scheme. The following introduces these four instruments. The Listening Section of GEPT Elementary Level GEPT stands for the General English Proficiency Test. This is a standardized test developed and administered by the Language Training & Testing Center (LTTC) commissioned by the Minister of Education of R.O.C. This test covers the four language skills of listening, reading, writing, and speaking and consists of five levels, 17.

(34) Elementary, Intermediate, High- Intermediate, Advanced, and Superior. In this study, the listening section of the GEPT elementary level was used to rank the students’ ability into three levels, high, middle, and low. Teaching Materials The materials used for teaching and reviewing the strategies come from one commercial book, Tactics for Listening (2nd edition) Book 1 by Richards (2003), and two free websites, Randall’s ESL Cyber Listening Lab http://esl-lab.com/ , ELLO http://www.elllo.org/english/home.htm. The past listening sectional exams in participants’ school are also included.. 治 政 Tactics for Listening contains three levels ,and Book1, the大 first level, was used 立 because it is for elementary proficiency level English learners, and the participants in ‧ 國. 學. this study belong to elementary level. It featured both top-down and bottom-up. ‧. processing exercises involving the practice of listening for main idea, selective. sit. y. Nat. attention, listening for details, and several inference-related skills such as listening for. io. al. er. attitude, listening for opinions and so on. Besides, it provides simple conversational. n. language and a verity of themes which match well to the themes in the participants’ English text book.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Randall’s ESL Cyber Listening Lab helps English learners to practice listening skill by providing self-grading quizzes and study materials which are divided into three levels from easy to difficult. Besides, topics in this website are various and authentic and scripts are also provided. Learners can choose their favorite topic according to their language proficiency and check their listening comprehension by themselves. ELLO is a website for English learners to enhance their English four skills. Its materials are sorted by 7 levels including beginner 1-3, intermediate 4-6, and advanced 7, and topics there are of varieties. Several quizzes about vocabulary, reading comprehension, listening comprehension, and speaking are also provided. 18.

(35) Besides, materials there are provided by English users from different countries; therefore, various English accents can be contacted. Past listening sectional exams in the participants’ school includes three parts. The first part usually requires students to choose the correct picture according to what they heard; the second part usually contains a short conversation and a question related to the conversation. The last part usually requires students to choose the right answer after they listened to a short passage. The three parts of the past listening sectional exams were used according to the researcher’s teaching purpose.. 立. 治 政 大 Reflective Journal. The reflective journal (see appendix A) includes two parts: one consists of a. ‧ 國. 學. performance check list and the other consists of two open-ended questions. This. ‧. reflective journal aims to know students’ strategy utilization and is used to analyze. sit. y. Nat. students’ utilization.. io. er. The first part of the reflective journal is based on Chen (2009) and it is a check list.. al. In this part, 30 questions are included and each question is corresponding to different. n. iv n C listening strategies which students use while they were listening. The questions h emight ngchi U are arranged according to listening process and are concrete sentences starting with ―I‖ so that students can understand the questions more and check their utilization of the strategies naturally. In order to collect more data of students’ listening strategies use, two open-ended questions were added. One involved students’ evaluation of their strategy use and the other involved students’ self-evaluation of their listening improvement.. 19.

(36) Strategy Classification Scheme The strategy classification scheme is adapted from Vandergrift (1997) and Chen (2009). This scheme (see Appendix B) includes three domains of listening strategies—cognitive strategies, metacognitive strategies, and social and affective strategies. Each domain contains different strategies and descriptions of the strategies. In the description of inference in Chen (2009), two definitions are deleted in strategy classification scheme used in this study. They are ―Draw on knowledge of the world and ―Apply knowledge about the target language.‖ The reasons for deleting the two definitions are as follows. For one thing, the two definitions are overlapped with the. 治 政 definitions in elaboration. For another, according to Vandergrift 大 (1997), inference 立 means using the knowledge within the text while elaboration means using prior ‧ 國. 學. knowledge from outside the text; therefore, the two definitions do not belong. ‧. inference according to Vandergrift.. sit. y. Nat. Treatment. io. er. Thirteen listening strategies (see Appendix C) were taught to see how junior high. al. n. school students adjust their listening strategies after the strategy instruction.. C h Strategies List U n i Listening engchi. v. The thirteen listening strategies belong to three domains including metacognitive strategies, cognitive strategies, and social and affective strategies. The following are the introduction of the strategies used in this study. Metacognitive strategies include planning and evaluation. The purpose of planning is to prepare oneself before a listening task either mentally or physically. The sub-strategies of planning include using an advance organizer, directed attention, and selected attention. In advance organizer, the researcher taught the students to read over what they had to do and try to think of questions the researcher is going to ask. In directing attention, the researcher taught students to concentrate themselves as 20.

(37) much as possible and to maintain attention even when they had trouble understanding some parts of the listening task. In selective attention, the researcher taught students to pay attention to specific aspects of language input that helped them understand the task before listening. In evaluation, the students were asked to write one reflective journal every two weeks. Monitoring as a metacognitive strategy was not explicitly taught in LSI because it was too difficult to teach monitoring due to the ephemeral nature of listening. However, the researcher encouraged students to always check their understanding while they were listening. The cognitive strategies taught in this study involve listening for the gist, listening. 治 政 for details with note-taking, prediction, imagery, inference, 大 and read the script after 立 listening. According to Nunan (2003) and Vandergrift ( 2004), successful listening ‧ 國. 學. happens when students are taught both bottom-up and top-down listening strategies.. ‧. Therefore, both bottom-up and top-down strategies were included in this study.. sit. y. Nat. In listening for the gist, the researcher taught students to listen for the main idea and. io. er. then the details. As for listening for details with note-taking, the researcher taught. al. students to pay attention to 6W (who, what, when, where, why, how), and discourse. n. iv n C markers such as ―however‖, ―but.‖ to help learners remember the details, h eInnorder gchi U. simple ways of note-taking was taught at the same time. In prediction, students were taught to predict the content they were going to listen according to some clues on the paper. In imagery, students were taught to mentally image what they heard especially in asking for the direction or prepositions of places. In inference, students were taught to make a guess according to the clues within the context while they were listening. Finally, students were asked to read the script of the listening message and check the unknown vocabulary after each class. The reason for choosing such skills as listening for gist, listening for details with note-taking, prediction, inference, and imagery to teach the students was according to 21.

(38) previous studies (Chan, 2009; Huang, 2008; You, 2007). In these studies, these five cognitive strategies were chosen to teach the students although the names of these strategies in the previous studies may be different from what the researcher used in this study. In other words, these five strategies are more often used in the LSI. With regard to the last strategy—read the script and check the vocabulary, though it seldom appears in LSI, according to Vandergrift (2008), offering students scripts after listening helps them developing auditory discrimination skills and more refined word recognition skills. Therefore, this strategy was included in this study. Social and affective strategies consist of cooperation, questioning for. 治 政 clarification, and confidence building. The three strategies大 were taught implicitly: that 立 is, the researcher had students work in groups and encouraged them to discuss ‧ 國. 學. problems with classmates during the instruction.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 22. i Un. v.

(39) Procedure The project includes a pilot study and a main study. Figure 3.4-1 shows the procedure of this study. Figure 3.1 Pilot Study. Pre-test. Listening Strategy Instruction. Week 8. Review. Week 9. Prediction. ‧. Week 3. Listening for the gist. Review. 學. Week 2. ‧ 國. Week 1. 治 政 Week 大 7 Metacognitive Strategies 立. y. n. C Review h. sit. io. al. note-taking. Week 5. Week10. Listening for details with. Listening for Inference. er. Week 4. Review Imagery. Nat. Listening for the gist. Imagery. i n U i e n g c hWeek11. Listening for details with. v. Review Listening for inference. note-taking Week 6. Prediction. Week 12. Review for the whole strategies. Analyze Reflective Journals in week 3, 7, 12. 23.

(40) Pilot Study Prior to the main study, a pilot study was conducted to ensure that teaching materials, the teaching plan, and the reflective journal were appropriate and feasible. The pilot study was conducted for two weeks and the participants of the pilot study were the other 7th grade students that the researcher taught. We found that the description of the two open questions were too vague for the students to understand. Therefore, the description of the two open questions was revised. Besides, students had problem in understanding some statements in the check list; therefore, a explanation in advance was needed.. 立. 治 政 大 Main Study. Before the study, the participants took listening section of the General English. ‧ 國. 學. Proficiency Test Elementary Level. Those whose scores were over 80 were grouped. ‧. into the high proficiency group (HP); those whose scores were between 60-79 were. io. er. below were in the low proficiency group (LP).. sit. y. Nat. considered as middle proficiency group (MP), and those who scored under 59 or. al. Metacognitive strategies can be applied in every listening task; therefore, it was. n. iv n C embedded in every session. That is, students trained to familiarize with h e nwere gchi U. pre-listening planning and post-listening evaluation once they were taught the metacognitive strategies from the first teaching session. Different cognitive strategies were the main teaching objectives in each strategy teaching session. Social and affective strategies were taught implicitly in each session. The researcher encouraged students to ask classmates or had students work in pairs to discuss their listening difficulties. Students were also welcomed to ask the researcher questions during the class. Furthermore, each strategy-teaching session was followed by a strategy-review session in order to help students review and deepen the strategies they learned. 24.

(41) Besides, reflective journals were given in every strategy-review session to help students reflect on what they had learned. The strategy instruction procedure was adapted from Chamot (2005) and Chen (2009) , and it was summarized as follows. First, the strategic-awareness raising phase: the teacher identified students’ present listening strategies through activities. Second, the demonstration phase: the teacher modeled the new strategy and made the instruction explicit. Third, practice phase: the students practiced the new strategies with similar task and worked as teams to discuss strategy use and listening difficulties. Fourth, evaluation phase: students self-evaluated the effectiveness of the focused strategies.. 立. 政 治 大. Last, expansion phase: students transferred strategies to new task, combined strategies. ‧ 國. 學. into clusters, and developed repertoire of preferred strategies.. ‧. The first to the third phase were included in every teaching session but the last. sit. y. Nat. two phases only happened in the review session and the last session. For one thing,. io. er. students did not have enough time to practice a new repertoire of task and make. al. reflection in every strategy teaching session. For another, in the review session and. n. iv n C the last session, the researcher provided listening task for students in h e n ga cmix-typed hi U. order to understand whether or not students could use the strategies flexibly in a new task. Data Analysis To answer the research questions, reflective journals in week 3, 7,12 –RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3—were analyzed. There were two ways of analysis in this study. One was quantitative analysis and the other was qualitative analysis. For the quantitative analysis, the reflective journals were coded by the researcher and the other English teacher. The coding scheme is adapted from Vandergrift (1997) and Chen (2009) and was shown in Appendix C. Before the coding, the researcher and the other English 25.

(42) teacher coded several copies and had discussion over the different coding first. After an agreement was reached, coding of all the reflective journals was conducted. The quantitative data were analyzed by SPSS version 11.5 for the descriptive statistics, and the inter-rater reliability was 1. Besides, to get a picture of students’ reported strategy utilization and development, not only the most and the least reported use of strategies were counted but also the comparison between RJ1 and RJ3 was counted. For qualitative analysis, the entries in the journals were all transcribed verbatim and categorized into several themes in order to find the development of students’ reported strategy use under the instruction.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 26. i Un. v.

(43) Chapter Four Results In this chapter, the results of the study are presented, and the answers to the research questions are addressed. Development in strategy use reported in the reflection journals in week3 (RJ1), week7 (RJ2), and week12 (RJ3) are examined quantitatively as a whole to answer the study’s research question one, namely, how students adjust their listening strategies after listening strategy instruction (LSI)? Next,. 治 政 metacognitive, cognitive, and social and affective strategies 大 are further discussed 立 respectively both quantitatively and qualitatively to answer the research question two, ‧ 國. 學. that is, what is the development of students’ metacognitive, cognitive, and social and. sit. y. Nat. Students' Strategy Use. ‧. affective strategies in listening after students received LSI?. io. er. Table 4.1 shows the frequency and mean in metacognitive, cognitive, and social. al. and affective strategy use reported from the students of the three proficiency groups in. n. iv n C RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3. We found that proficiency group used strategies the least h ethenlow gchi U. metacognitive, cognitive, and social cognitive strategies except for the metacognitive strategies in RJ3 in which HP group used the metacognitive strategies the least among the three groups. Besides, comparing the means of the three strategies, we also found that metacognitve strategies were the most used strategies in which the average mean is up to 13.89 while social and affective strategies were the least one in which the average mean is 2.11, only one sixth of the use of metacognitive strategies. With respect to the development of the use of the three strategies, Table 4.1 presents that the mean of the reported use of metacognitve strategies dropped by 8% 27.

(44) from 14.25 to 13.08 in the final stage of LSI; the reported use of cognitive strategies increased by 5% from 8.47 to 8.91 as the LSI proceeded while the reported use of social and affective strategies went down by 9% from 2.33 to 2.11. Regarding the development of the use of the strategies by the three groups, the result can be indicated as follows: In HP group, students decreased their reported use obviously in metacognitive strategies by 18% from 14.54 to 12.18 and in social and affective strategies by 11% from 2.45 to 2.18 whereas there is no obvious change in the reported use of cognitive strategies, from 8.81 to 8.72, only by 1%. In MP group, the reported use of. 治 政 metacognitive strategies decreased by 5% from 14.57 to 13.86, 大 and cognitive 立 strategies increased obviously by 30% from 8.43 to 11 whereas the reported use of ‧ 國. 學. social and affective strategies went down by 17% from 2.57 to 2.14 respectively. In. ‧. LP group, comparing with HP and MP groups, the reported use of the three strategies. sit. y. Nat. stabilized in the three journals. The difference of the mean of the three strategies in. io. 5%.. er. RJ1 and RJ3 were all less than 1 and the changes of the percentage were all less than. al. n. iv n C To sum up, to answer the research question result can be concluded as h e n1,gthe chi U. follows: first, when comparing the mean of the reported use of the three strategies, we found that metacognitve strategies were the most used strategies while social and affective strategies were the least one, and reports in the use of the three strategies by LP group were the least except for the metacognitive strategies in RJ3 in which HP group used the metacognitive strategies the least among the three groups. Next, when comparing RJ1 and RJ3 in the three strategies, we found that students’ reports in metacognitive strategies use declined; in cognitive strategies increased, and in social and affective strategies declined as LSI proceeded. Moreover, when analyzing the difference in the reported use of the strategies by 28.

(45) different proficiency levels, students in HP group decreased their reported use obviously in metacognitive strategies and social and affective strategies whereas the reported use of cognitive strategies stabilized. In MP group, compared to HP group, the reported use of metacognitive strategies also declined but the decreased is minor whereas their reported use in cognitive strategies increased obviously, and the reported use in social and affective strategies also decreased obviously. In LP group, the change of the reported use of the three strategies is small; in other words, students in LP group stabilized their utilization of the three strategies.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 29. i Un. v.

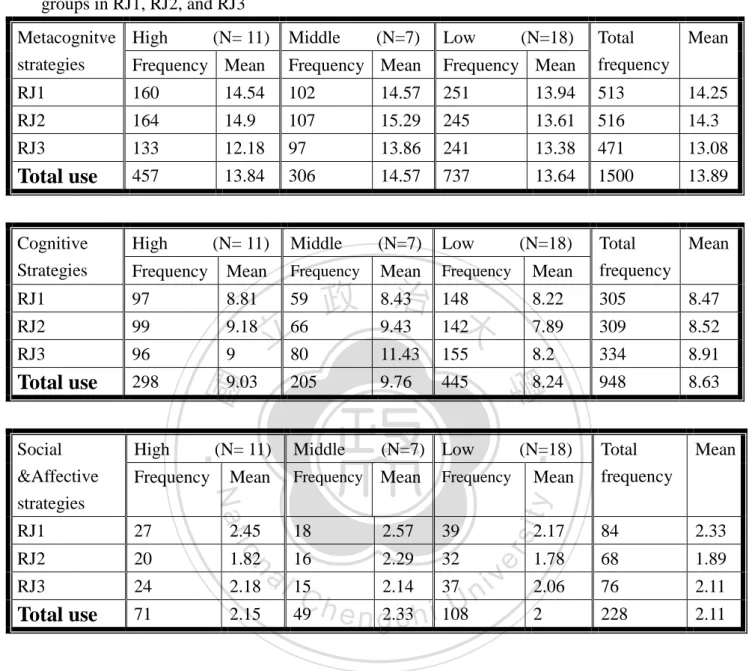

(46) Table 4.1: The frequency and mean of metacognitive strategies, cognitive strategies and social and affective strategies use reported from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3 Middle. Mean. Frequency Mean. Total frequency. Frequency Mean. RJ1. 160. 14.54. 102. 14.57. 251. 13.94. 513. 14.25. RJ2. 164. 14.9. 107. 15.29. 245. 13.61. 516. 14.3. RJ3. 133. 12.18. 97. 13.86. 241. 13.38. 471. 13.08. Total use. 457. 13.84. 306. 14.57. 737. 13.64. 1500. 13.89. Cognitive Strategies. High. (N= 11). Middle. (N=7). Low. (N=18). Frequency. Mean. Frequency. Mean. Frequency. RJ1. 97. 8.81. 59. RJ2. 99. 9.18. RJ3. 96. 9. 立6680. Total use. 298. 9.03. Social &Affective strategies. High. RJ1. 27. RJ2. 20. RJ3. 24. Total use. 71. 305. 8.47. 7.89. 309. 8.52. io. 11.43. 155. 8.2. 334. 8.91. 205. 9.76. 445. 8.24. 948. 8.63. Middle. (N=7) Low. Frequency. Mean. Frequency. 18. 2.57. 39. 2.29. 32. 2.14. 37. 16 a 2.18 l 15 Ch. n. 1.82 2.15. 8.22. (N=18). Total frequency. Mean. 2.17. 84. 2.33. 1.78. 68. 1.89. 2.06. 76. 2.11. 2. 228. 2.11. Mean. y. Nat. 2.45. 治 148 政 8.43 大 9.43 142. Mean. Total Mean frequency. 49. i Un. e n g2.33 c h i 108. 30. sit. Mean. (N=18). er. Frequency. Low. ‧. (N= 11). (N=7). 學. ‧ 國. Metacognitve High (N= 11) strategies Frequency Mean. v.

(47) Metacognitive Strategies Use in Listening Metacognitive Strategies Use in Listening--Quantitative Analysis When the mean of the three metacognitive sub-strategies, planning, monitoring, and evaluation, were further examined, some variations in students’ reported use of the sub-strategies were demonstrated, see Figure 4.1. Planning was the most frequently reported used among the three sub-strategies while evaluation was the least frequently reported used during LSI. Figure 4.1: The mean of metacognitive sub-strategies use reported from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3.. 10. 立. 8. ‧ 國. 學. 6 4. ‧. 2. Nat. Monitoring. Evaluation. io. sit. Planning. RJ3. er. 0. RJ1 RJ2. y. Mean. 政 治 大. al. Table 4.2 shows the mean and the frequency of the metacognitive strategies use in. n. iv n C the three stages of LSI. We found groups which used planning, monitoring, or h ethatnthe gchi U evaluation the most frequently or the least frequently in every stage are diverse. In other words, there is no obvious consistency between proficiency levels and the reported use of metacognitive strategies. Besides, we also found that the reported use of all the metacognitive strategies all declined with the mean dropped by 7% from 9.8 to 9.11 in planning, by 3% from 2.47 to 2.39 in monitoring, and by 30% from 1.94 to 1.36 in evaluation when we compared RJ1 and RJ3.. 31.

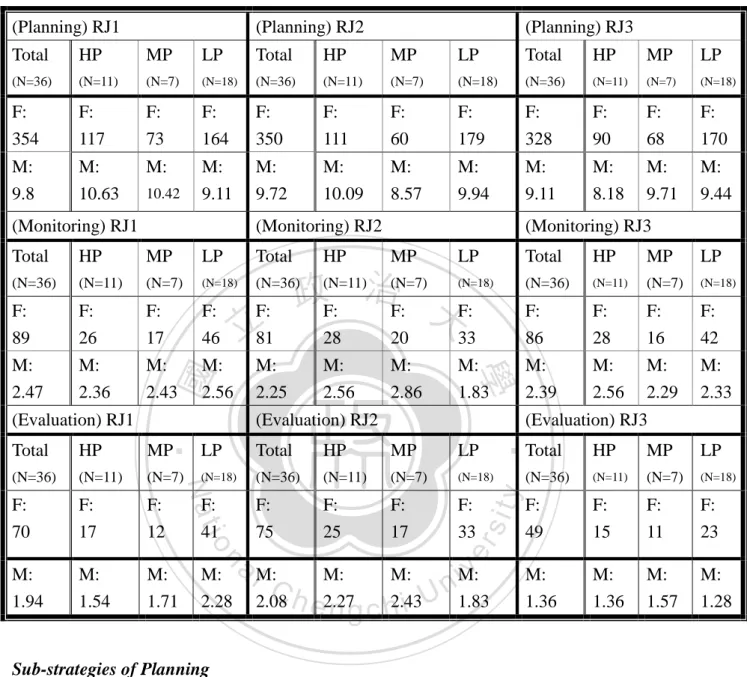

(48) Table 4.2: Metacognitive strategy reported use from students of the three groups in RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3. (F=Frequency; M=Mean) (Planning) RJ1. (Planning) RJ2. (Planning) RJ3. Total. HP. MP. LP. Total. HP. MP. LP. Total. HP. MP. LP. (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). F: 354. F: 117. F: 73. F: 164. F: 350. F: 111. F: 60. F: 179. F: 328. F: 90. F: 68. F: 170. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. M:. 9.8. 10.63. 10.42. 9.11. 9.72. 10.09. 8.57. 9.94. 9.11. 8.18. 9.71. 9.44. (Monitoring) RJ1. (Monitoring) RJ2. Total. HP. MP. LP. Total. (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). (N=36). F: 89. F: 26. F: 17. F: 46. F: 81. M: 2.47. M: 2.36. M: 2.43. M: 2.56. LP. Total. HP. MP. LP. (N=18). (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). F: 28. F: 16. F: 42. M: 2.56. M: 2.29. M: 2.33. 治(N=7) 政(N=11) F: F: 大F:. M: 2.25. ‧ 國. MP. 28. 20. 33. F: 86. M: 2.56. M: 2.86. M: 1.83. M: 2.39. 學. (Evaluation) RJ1. 立. HP. (Monitoring) RJ3. (Evaluation) RJ2. (Evaluation) RJ3. ‧. MP. LP. Total. HP. MP. LP. (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). F: 70. F: 17. F: 12. F: 41. F: 75. F: 25. F: 17. F: 33. M: 1.94. M: 1.54. M: 1.71. M: 2.27. M: 2.43. n. a lM: C 2.08 h. engchi. sit. er. io M: 2.28. y. HP. Nat. Total. M: iv n U 1.83. Total. HP. MP. LP. (N=36). (N=11). (N=7). (N=18). F: 49. F: 15. F: 11. F: 23. M: 1.36. M: 1.36. M: 1.57. M: 1.28. Sub-strategies of Planning Table 4.3 shows the mean of the sub-strategies of planning—advance organization, directed attention, selective attention, self-management— and presents that directive attention was the most frequently reported used with the average mean to 3.34 whereas self-management was the least frequently reported used with the average mean to 0.89 during LSI.. 32.

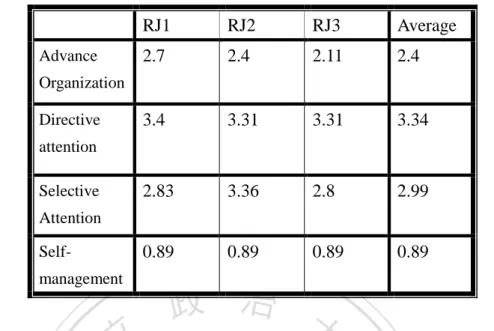

(49) Table 4.3: The mean of the reported use of the sub-strategies in planning reported by students from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3.. Advance. RJ1. RJ2. RJ3. Average. 2.7. 2.4. 2.11. 2.4. 3.4. 3.31. 3.31. 3.34. 2.83. 3.36. 2.8. 2.99. 0.89. 0.89. 0.89. 0.89. Organization Directive attention Selective Attention Selfmanagement. 政 治 大 When comparing RJ1 and RJ3 reported from the three groups in the reported use of 立. ‧ 國. 學. the sub-strategies in planning as shown in Table 4.4 and Table 4.5, we found changes in the reported use of sub-strategies in planning by the three groups. Regarding the. ‧. reported use of advance organization, students of the three groups all decreased the. Nat. sit. y. reported use of this strategy, and it was decreased 48% by HP group with the mean. n. al. er. io. from 3.09 to 2.09, 18% by MP group with the mean from 2.28 to 1.86, and 12% by LP. i Un. v. group with the mean from 2.56 to 2.22. Besides, advance organization was the only. Ch. engchi. sub-strategy in planning which was decreased by all the three groups. In terms of directive attention, the mean of the reported use went down in HP group and MP group but went up in LP group. The mean in HP group decreased by 13% with the mean from 3.36 to 2.91, and the mean decreased by 22% in MP group with the mean from 3.85 to 3 whereas the mean increased by 10% in LP group with the mean from 3.33 t0 3.72. As for selective attention, the mean of the use in HP group dropped by 32% from 3.45 to 2.36 but increased in MP group and LP group. The mean in MP group went up by 25% with the mean from 2.85 to 3.57 and the mean in LP group also went up by 33.

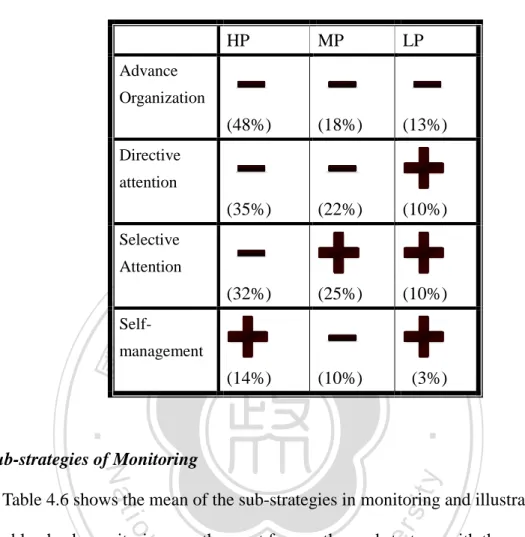

(50) 10% with the mean from 2.44 to 2.72. In the reported use of self-management, HP group and LP group both increased their reported use but MP group decreased it. The mean of the use in HP group went up by 14% with the mean from 0.72 to 0.82 and in MP group, the mean decreased by 10% from 1.43 to 1.28, and in LP group, the mean increased by 3% with the mean from 0.77 to 0.79. To sum up, as Table 4.5 indicated, HP group obviously decreased their reported use of the sub-strategies in planning except for self-management which was increased 14% instead. MP group also decreased their reported use in sub-strategies in planning. changes in LP group were the least among the three groups.. 學. ‧ 國. 治 政 except for selective attention which was increased 25% instead. 大 LP group increased 立 all the sub-strategies in planning except for advance organization. However, the ‧. Advance. HP (N=11). Organization. MP (N=7). n. LP (N=18). al. RJ1. RJ2. 3.09. 2.55. 2.28 C h. 2.71. hi U 2.56 e n g c 2.27. RJ3. er. Proficiency level. io. Strategies. sit. y. Nat. Table 4.4: The mean of the use of the sub-strategies in planning reported by students of different proficiency levels from RJ1, RJ2, and RJ3. Average. v n i 1.86. 2.58. 2.22. 2.35. 2.09. 2.28. Directive. HP (N=11). 3.36. 2.81. 2.91. 3.03. attention. MP (N=7). 3.85. 3.42. 3. 3.42. LP (N=18). 3.33. 3.56. 3.72. 3.54. Selective. HP (N=11). 3.45. 3.72. 2.36. 3.18. Attention. MP (N=7). 2.85. 3.14. 3.57. 3.19. LP (N=18). 2.44. 3.22. 2.72. 2.79. Self-. HP (N=11). 0.72. 1. 0.82. 0.85. management. MP (N=7). 1.43. 0.71. 1.28. 1.14. LP (N=18). 0.77. 0.89. 0.79. 0.82. 34.

(51) Table 4.5: The percentage of the reported use of the sub-strategies in planning from students of different proficiency levels when RJ1 and RJ3 are compared. ( + increase/ - decrease) HP. MP. LP. (48%). (18%). (13%). (35%). (22%). (10%). Advance Organization. Directive attention. Selective Attention. Self-. 立. 治 政 (32%) (25%) 大. ‧ 國. (14%). (10%). 學. management. (10%). (3%). ‧ sit. y. Nat. Sub-strategies of Monitoring. io. er. Table 4.6 shows the mean of the sub-strategies in monitoring and illustrates that. al. double-check monitoring was the most frequently used strategy with the average. n. iv n C mean to 1.2 whereas auditory monitoring least frequently used strategy with h e n g cwashthe i U the average mean to 0.48, only about one third of double-check monitoring. When comparing RJ1 and RJ3 reported from the three groups in the use of the sub-strategies in monitoring as shown in Table 4.7 and Table 4.8, we found changes in the reported use of sub- strategies in monitoring strategies by the three groups. 35.

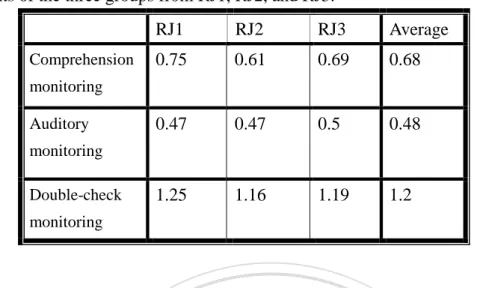

數據

+7

相關文件

Once students are supported to grasp this concept, they become more willing to use English for self-expression and that in turn, is the finest form of empowerment!... What makes

6. To complete the ‘What’s Not’ column, students need to think about what used to be considered a fashionable thing to do, see, listen to, talk about and is no longer

配合小學數學科課程的推行,與參與的學校 協作研究及發展 推動 STEM

初中聆聽範 疇的學與教 策略-

Rebecca Oxford (1990) 將語言學習策略分為兩大類:直接性 學習策略 (directed language learning strategies) 及間接性學 習策略 (in-directed

電子學習 教學 教學 教學 教學 聲情教學 聲情教學 聲情教學 聲情教學.. 策略 策略

The remaining positions contain //the rest of the original array elements //the rest of the original array elements.

配合小學數學科課程的推行,與參與的學校 協作研究及發展 推動 STEM