Keeping the high-tech region open and dynamic: the organizational networks of

Taiwan’s integrated circuit industry

Sue-Ching Jou

1,∗and Dung-Sheng Chen

21Department of Geography, 2Department of Sociology, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Section 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, Taiwan 106, Republic of China; ∗Author for correspondence (Fax: 886-2-2362-2911; E-mail: jouchen@ccms.ntu.edu.tw)

Received 28 March 2001; accepted 10 December 2001

Key words: high-tech regions, industrial districts, Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park, industrial networks, organizational

networks, Taiwan’s integrated circuit industry

Abstract

This paper aims to bridge the literatures of industrial districts and organizational networks by studying the development of organizational relationships in Taiwan’s integrated circuit (IC) industry. Firms of the IC industry in Taiwan are highly concentrated in the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park (HSIP). They not only have contributed the most to the combined sales for the HSIP compared to other industries for half a decade, but also have made Taiwan the country with the fourth-largest IC industry in the world today. Along with the creation and maintenance of global competitiveness in this industry, the means of developing organizational relationships and geographical linkages are examined in this paper. The empirical findings are based on analysis of data regarding the organizational connections for Taiwan’s IC industry during 1976 to 1996, collected at the individual firm level. It is found that a concurrent process of intensifying the internal as well as external linkages has occurred in the HSIP, a young high-tech region. It indicates that not only is the “regional advantage” sufficiently sustained, but also the global industrial networks are continuously expanded to maintain the openness and dynamics of the region.

Introduction

Taiwan’s high-tech firms have been experiencing quite rapid growth since the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park (HSIP) was established to promote high-tech industries in 1980. In less than two decades, Taiwan has achieved rank-ing as the possessor of the world’s third-largest information industry (after the United States and Japan) and the world’s fourth-largest integrated circuit industry (after the United States, Japan, and Korea). Technology-intensive industries accounted for 37.5% of the nation’s total manufacturing out-put in 1995, up from 24% in 1986, approximately the time at which high-tech accomplishment began to flourish in Taiwan (National Science Council, ROC, 1997).

With this high-profile advancement in high-tech indus-tries, the pivotal role that the HSIP has played for the past two decades in accomplishing the high-tech miracle in Taiwan is well recognized (Pasek, 1997). The HSIP and its surrounding area has become a well-known addition to the world’s high-tech territories, even being admired as the “Eastern Silicon Valley” (Mathews, 1997).

Studies on the developmental experiences of California’s Silicon Valley and other high-tech districts in the world have made the thesis of new industrial space (NIS) quite volatile in academia for the past decade (Scott, 1988; Henry, 1992; Sternberg, 1996; Storper, 1997; Braczyk et al., 1998).

Under this research stream, the experience of the HSIP is ap-proached as a model of a late-industrial district (Hsu, 1997; Mathews, 1997). Research interest is centered mainly on ex-ploring how the innovative milieu and high-tech capability of the HSIP has been incubated (Hsu, 1997; Mathews, 1997; Saxenian, 1998; Saxenian and Hsu, 1999). Some may argue that it has been achieved as ‘a deliberate matter of public policy to create a unique industrial eco-system’, rather than being just a spontaneous development (Meaney, 1994; Math-ews, 1995, 1997; Hsu, 1997). Some thoroughly document the contribution of the high-tech returnee in the processes of technology learning and transfer, from either the perspective of returnee entrepreneurism or that of the ethnic ties between Silicon Valley and Hsinchu (Hsu, 1997; Saxenian, 1998; Saxenian and Hsu, 1999).

Those literatures do make efforts to echo some argu-ments and theoretical concerns proposed by the thesis of NIS. They mainly focus on exploring the characteristics and formation of a late-coming learning region in a highly competitive global market (Hsu, 1997; Saxenian, 1998; Sax-enian and Hsu, 1999). However, some other perspectives, especially those related to industrial networks (Cooke and Morgan, 1993; Grabher, 1993; Belussi, 1996), have not yet been systematically examined for the Hsinchu region. Be-sides, it is necessary to provide accurate empirical evidence showing the exact nature of the globalization process that

occurred within and across the Hsinchu high-tech region to avoid the accusation of a lack of solid empirical evidence that plagues most studies on the New Industrial Spaces (Udo, 1997). Consequently, this paper attempts to bridge the lit-eratures of industrial districts and organizational networks by studying the development of organizational relationships in Taiwan’s integrated circuit industry. Recent literatures of the above regards propose an ‘institutional turn’ toward the study of new industrial districts and the local economic de-velopment. Along this line of research, local institutional capabilities or institutional thickness are considered as the key factors to facilitate a knowledge-based economy in a form of highly networked learning region where global com-petitiveness has been achieved (Cooke and Morgan, 1993; Amin and Thrift, 1995; Raco, 1999). However, using the ‘new institutionalism’ approach to study the new indus-trial districts emphasizes too much on endogenous factors, such as local/regional networks and institutional bases. It neglects effects or/and imperative of concurrently existed ex-ternal/global networks for a successfully established learn-ing region. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to indicate the significance of this phenomenon.

The main research task of this paper is to show that vari-ous types of organizational relationships and spatial linkages have been developed in a high-tech region, the HSIP. The empirical findings are based on analysis of data regarding the organizational connections for Taiwan’s IC industry during 1976 to 1996, collected at the individual firm level by the authors. Its purpose is, on the one hand, to explain how Tai-wan’s IC industry has created and maintained its global com-petitiveness from the perspective of organizational networks. On the other hand, it shows how a young high-tech region sustains its “regional advantages” by increasing the intensity of internal linkages and by extending its diversified external linkages through corporate organizational strategies.

Why the integrated circuit industry?

Both the computer industry and integrated circuit industry developed Taiwan into relatively successful players in the global market. There are two main reasons for us to choose the integrated circuit industry rather than the computer in-dustry as the sample inin-dustry in this study. The first is a practical consideration. Relatively speaking, the IC industry is more concentrated in the Hsichu region than the computer industry. Its technological level is higher than that of the computer industry in general. Specifically, development of the IC industry has outstripped that of the computer industry in the HSIP since the beginning of the 1990s, in terms of both combined sales and invested capital.

The second reason is in keeping with methodological considerations. There is a relatively shorter industrial his-tory and smaller number of companies in the IC industry, which makes the collection of longitudinal data much eas-ier than for the computer industry. In 1996, the year we conducted our research, there were only 112 IC firms in Taiwan. Around two thirds of these 112 firms were only small-scale companies. These companies were not included

in our database because there are difficulties in tracing their organizational relationships either through secondary data sources or by interview. However, the overall values of their products account for only 5% of the total combined sales of the IC industry for the whole nation.

Why Taiwan’s IC industry is so successful and “efficient” in the global market has begun drawing academic interest recently (Henderson, 1991; Chang et al., 1993; Liu, 1993; Mathews, 1995, 1997; Chen and Sewell, 1996; Hsu, 1997). One answer to the above question is that the industry has successfully developed a vertically disintegrated agglomera-tion system in the Hsinchu region for the past two decades. In other words, the local industrial networks of Taiwan’s IC industry are important constituents of the Hsinchu high-tech region. Therefore, it is worthwhile to keep enriching empir-ical studies to show how the industrial district and high-tech industry reinforce mutual development. But, if we confine our arguments just to endogenous factors, we will miss the whole picture of how a high-tech region and an industry maintain their global competitiveness. Therefore, this paper will approach the industrial district studies particularly from the perspective of organizational networks and show how the organizational relationships built by Taiwan’s IC firms have contributed to the development of the IC industry in Taiwan. General characteristics of the IC industrial networks, based on the longitudinal data of organizational relationships from 1976 to 1996, will be analyzed in the following section.

Our data were collected by exhausting all the secondary data sources in Taiwan (newspapers, magazines, companies’ annual reports, yearbooks of the semiconductor industry, related technical reports, and so forth) and tracing down each organizational event to be recorded for each individual firm. Organizational events were defined in our study as the actions taken by high-tech organizations in a broad sense, which had some influences on organizational development. There were 1,319 organizational events in total occurred dur-ing 1976 to 1996 for thirty-two large-sized IC companies in Taiwan (including all of the IC manufacturing companies, all of the IC mask companies, eight largest IC design compa-nies and eight largest IC packaging and testing compacompa-nies). These organizational events included activities related to three different levels, which were intra-organizational, inter-organizational and extra-inter-organizational activities. We also tried to verify those organizational events during depth in-terviews to each of those thirty-two companies, though some interviewees could not provide direct verification. In this paper, only the inter-organizational events will be used as data to analyze the organizational connections for Taiwan’s IC industry.

We will begin by describing the general trend of all organizational linkages that have ever been built by ma-jor Taiwanese IC companies. Second, we will try to ex-amine the geographical linkages that those organizational relationships have already extended. Finally, types of or-ganizational relationships and the degree of oror-ganizational interactions will be investigated to reveal the characteristics of the spatial-industrial networks of Taiwan’s IC industry.

General characteristics of organizational networks for Taiwan’s IC industry

Increasing intensity of organizational relationships with the maturation of industry

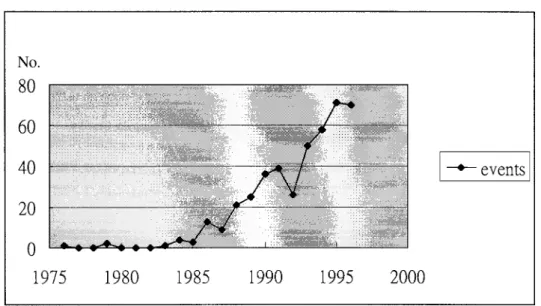

Based on previous studies, we can generally divide the de-velopment of Taiwan’s IC industry into three stages (Hong, 1992; Liu, 1993; Mathews, 1995; Hsu, 1997). The seed stage can be dated back to the period from 1964 to 1979, the start-up stage from 1980 to 1989, and the expansion stage from 1990 to the present. The development of organizational relationships for Taiwan’s IC firms can be examined with reference to its stages of industrial development. Figure 1 summarizes the annual organizational events for Taiwan’s IC firms for the years 1975 to 1996. From Figure 1, we can find that the frequency of organizational relationships increases from the early stage to the latter stage.

During the seed stage, only one to two organizational events occurred every year, and they were usually initiated by the public sector, i.e., by the ITRI (Industrial Tech-nology Research Institute), which was seeking to transfer technology from abroad or to transfer its technology to a domestic company. The trend then underwent a dramatic change during the start-up stage, during the decade of the 1980s. Relatively limited organizational events occurred during the first half of the 1980s. Organizational events in-creased rapidly after 1985. That is because more than 70% of the IC companies were established after 1987. It was at that time that the private sector began taking the lead in creating opportunities for organizational cooperation. The trend con-tinues into the third stage, the expansion stage. The growth rate of organizational relationships keeps increasing steadily during the third stage, though the number of companies does not increase at the same rate. In other words, the organiza-tional relationships increase rapidly as the industry becomes mature.

Those familiar with Taiwan’s IC industry can also find that the scale of Taiwan’s major IC companies kept in-creasing during the 1990s. However, the industrial system developed more toward a vertical disintegration system, rather than a vertical integration system. This implies that the creation of organizational links is quite an important organizational strategy for the development of Taiwan’s IC firms and the whole industry. Nevertheless, the kinds of spatial relationships that exist for the above organizational trend is our next concern. Is Taiwan’s IC industry prone to a local-network type? Or is it paralleled with intensive global-connected networks? This question, which we address in the following section, is of paramount concern in most literature of industrial districts.

The local and international linkages of organizational networks

The frequency distribution of organizational relationships that can be traced is presented in Table 1 by five-year period and by country to show the temporal transition of spatial linkages. In Table 1, we can find that organizational

relation-Table 1. Organizational connections by country and by year.

Year Taiwan U.S.A. Japan Europe Others Total

1976–80 1 2 3 1981–85 4 4 6 8 1986–90 55 32 10 4 3 104 1991–95 128 72 27 7 10 244 1996 36 24 3 2 5 70 Total 224 134 40 13 18 429 (percent) (52.2%) (31.2%) (9.3%) (3.1%) (4.2%) (100%)

ships occur largely among Taiwan’s IC companies or organi-zations. They account for more than half of the total events (52.3%). The number does show that local organizational relationships are more likely to be made than global ones, but the industrial networks for Taiwan’s IC industry are not locked into the local/domestic connections. For an industry in which market competition and technological information exchange are highly globalized, it is very important to have outside organizational relationships. Organizational coop-eration can create various channels for companies to gain market information, customers, technology, and capital.

The percentage of the organizational connections be-tween American firms and Taiwanese firms is 31.2%, mak-ing this category the second largest of all types of spatial relationships. This shows that the linkages between the firms in these two countries are quite strong in terms of number of organizational relationships. The percentage of Taiwanese firms and Japanese firms ranks third, with 9.3%. The rela-tionships between Taiwanese firms and European firms are relatively weak compared to their links with other techno-logically advanced countries. The number of events is only 13 and the percentage is only 3.1%. However, this does not necessarily mean that European companies have con-tributed less significantly to the development of Taiwan’s IC industry than those from America or from Japan. The Dutch company Philips is the very first company to form a joint-venture agreement with Taiwan’s government. With Philips’s capital investment, technology transfer, and patent protection umbrella, the ERSO/ITRI (Electronics Research & Services Organization, Industrial Technology Research Institute) spin-off, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufactur-ing Company, was then able to be established and to develop rapidly.

In the temporal dimension, we can find that the number of organizational connections among Taiwan’s companies increases significantly from 1986 to 1996. On the one hand, this occurred with the increase in international linkages. The number of organizational connections between Taiwanese companies and American companies also increased during the same period. The same phenomenon occurred between Taiwan’s companies and Japan’s companies as well, particu-larly after 1991. When Taiwan’s companies become large in scale and in capital, they have much greater resources with which to initiate organizational connections than be-fore. In addition, their technological excellence, especially

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of organizational relations for Taiwan’s IC industry.

in manufacturing abilities, attracts foreign companies to look for alliance opportunities with them. These are two major reasons to explain why the number of organizational links increased largely after 1990.

On the other hand, local organizational relationships do not decrease as global connections increase. This means that internal connections remain very intense within Taiwan’s vertically disintegrated industrial system. That is because a large number of local organizational ties are crucial to maintain its efficiency and flexibility. Owing that the study samples, those three-two large-sized IC companies, are mostly located in the HSIP and surrounding industrial parks except three IC design companies located in Taipei area, local/internal linkages should be greatly benefited by the clustering effects of Taiwan’s IC industry.

The above analysis is based on the number of organi-zational relationships created for Taiwan’s IC firms. It still lacks the solid evidence needed for us to differentiate the strength and types of organizational linkages among the lo-cal and international relationships. That is the main task of the following section. It is quite necessary to address this issue, because previous studies on industrial districts, especially the late-coming learning regions, have some im-plications. First, internal networks emphasize too much the flexibility of local production networks. Second, outside connections give significant attention to only one type of organizational relationship, that of technological source and transfer.

Diversification of the industrial networks

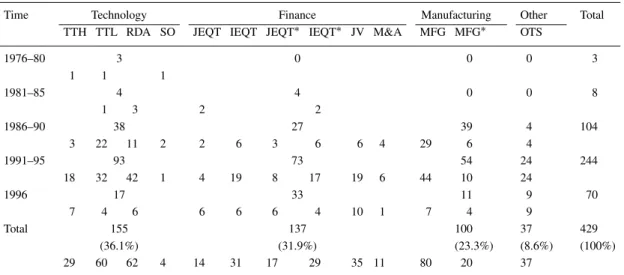

In our analysis, organizational relationships are divided into four general categories: technology, finance, manufactur-ing, and others. Technological relationships are defined as technology transfer, research and development agreement, and spin-off. Financial collaboration includes minority eq-uity investment, majority eqeq-uity investment, merge and acquisition, and joint venture. Manufacturing relationships encompass outsourcing production. Other types of

relation-ships include marketing agreement, human resource training agreement, and property right agreement. The results are summarized in Table 2. We can read from Table 2 that the to-tal number of technology connections, financial connections, manufacturing connections, and others are 155 (36.1%), 137 (31.9%), 100 (23.3%), and 37 (8.6%), respectively. In short, there are three major organizational types of indus-trial networks. It is not just a specific indusindus-trial network, but rather a diversified-network model. The result of this analysis obviously demonstrates the diversity of Taiwan’s IC industrial system and indicates that Taiwan’s IC compa-nies have been aggressively establishing organizational links with other companies by technology transfer or cooperation; by equity investment, joint venture, and acquisition; or by collaborative production. Through these different channels, these companies maintain as well as expand the scope of the industrial networks.

When the industry becomes mature, inter-firm connec-tions are more diversified than before. The IC companies have interacted in all the four general types of organizational cooperation. Especially after 1987, when the industry moved into the local initiative stage, there were many more pri-vate companies that were eager to make organizational links simultaneously with local and global companies.

In order to understand the quality of inter-firm links, we have to investigate the degree of organizational interdepen-dence among different types of inter-firm connections. This paper follows Hagedoorn’s framework (1990) to classify the degree of organizational interdependence into different types of inter-firm relationships. According to his work, joint venture possesses the highest degree of organizational in-terdependence, followed in descending order by research and development agreement, direct investment, customer-supplier manufacturing relations, and mutual technology exchange agreements. One-directional technology flow is the lowest. However, this framework is neither sufficient nor adequately clear to include all the types of connections in our research. Not all equity investment relationships have high-intensity interaction among partners, and some might invest

Table 2. The evolution of types of organizational connections over twenty years.

Time Technology Finance Manufacturing Other Total

TTH TTL RDA SO JEQT IEQT JEQT∗ IEQT∗ JV M&A MFG MFG∗ OTS

1976–80 3 0 0 0 3 1 1 1 1981–85 4 4 0 0 8 1 3 2 2 1986–90 38 27 39 4 104 3 22 11 2 2 6 3 6 6 4 29 6 4 1991–95 93 73 54 24 244 18 32 42 1 4 19 8 17 19 6 44 10 24 1996 17 33 11 9 70 7 4 6 6 6 6 4 10 1 7 4 9 Total 155 137 100 37 429 (36.1%) (31.9%) (23.3%) (8.6%) (100%) 29 60 62 4 14 31 17 29 35 11 80 20 37

TTH: strong-interaction technology transfer; TTL: weak-interaction technology transfer; RDA: research and development agree-ment; SO: spin-off; JEQT: weak-interaction majority equity investagree-ment; IEQT: weak-interaction minority equity investagree-ment; JEQT∗: strong-interaction majority equity investment; IEQT∗: strong-interaction minority equity investment; JV: joint venture; M&A: merge and acquisition; MFG: weak-interaction outsourcing production agreement; MFG∗: strong-interaction outsourcing production agreement; OTS: Others (including marketing agreement, property right agreement, multi-purpose consortium, human resource training agreement, production capacity share agreement, etc.).

money only into targeted companies. On the other hand, some manufacturing relationships and technology transfer relationships might involve intensively cooperative interac-tion. Therefore, some equity investment, technology trans-fer, and manufacturing relationships are classified into either the strong interaction type or low interaction type based on information provided in organizational events’ descriptions. Strong interaction relationships are those having high inter-action intensity in terms of both time and frequency, while low interaction relationships are the opposite. Spin-off and merge are the same as joint venture in terms of the degree of organizational interdependence because they have simi-larly strong relationships among partners. All other types of connections are treated as low-interaction relationships.

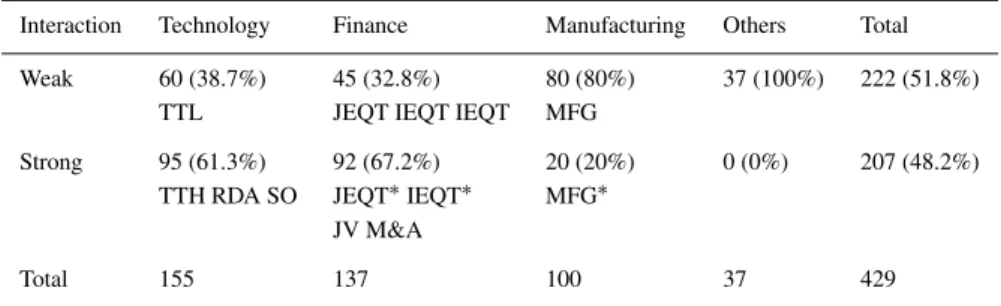

Table 3 summarizes the frequency of low and high inter-action for different types of organizational connections. The chi-square value for Table 3 is 96.61, which is statistically significant at the degree of freedom 3. If we adjust the degree of freedom and the sample size, the Cramer’s V for Table 3 will be 0.475. This statistical test indicates that there are sig-nificant variations in intensity (or strength) of organization interaction for different types of organization connections. That is, there are strong associations between the intensity of organizational relationships and the type of organiza-tional relationships. In short, there were higher proportions of strong ties in technological relationships and financial collaborations than that of manufacturing relationships.

In addition, the percentage of strong interaction is 48% while the percentage of weak interaction is 52%. The in-dustrial networks are based on both strong interaction and weak interaction. Through strong ties, the industrial network can create sufficient trust, personal communication, and ex-change of ideas among firms to facilitate their cooperation while over-dependence on the ties will lead to the problem of over-embeddedness (Uzzi, 1997). Strong interaction can

also contribute to the incubation of sustainable technolog-ical capabilities in industrial late-comers such as Taiwan because strong interaction does not just transfer technol-ogy; it also teaches receivers about know-how, work attitude, management and coordination among different departments, and independent research development abilities (Hsu, 1997). With weak ties, the network can extend the scope of its re-source flow and can reach out to some potential partners. Weak ties can prevent the exclusion and closure of a network based solely on strong ties. The combination of strong and weak interaction has its advantages.

Numbers of different types of organizational connections in five countries are reported in Table 4. Among Taiwan’s companies, links occur most frequently in financial interac-tion (38.8%), then in manufacturing relainterac-tionships (31.7%), then in technological exchange (23.2%); they occur least frequently in other interactions. The highest percentage of connections between American and Taiwanese companies is in technological exchange. That number is more than half of the total (50.7%). The reason is very clear. The United States has the most advanced IC technology; therefore, her companies surely become major sources of technological exchange. The percentage for Taiwan-Japan connections is also highest in technological exchange, but it should be no-ticed that technology transfer from Taiwan to Japan in 1986, 1991, and 1993 accounts for six events in weak interaction technological transfer.

The other numbers also support this argument. Of 156 technological cooperation events, 44% occur between American and Taiwanese companies, while only 17% hap-pen in Taiwan-Japan and Taiwan-Europe companies. Tech-nological cooperation among Taiwan’s companies is the sec-ond most important source for technological development. This indicates that Taiwan’s companies have incubated their own research and development capabilities. They are not

Table 3. Types of organizational connections by the intensity of interaction in relationships.

Interaction Technology Finance Manufacturing Others Total

Weak 60 (38.7%) 45 (32.8%) 80 (80%) 37 (100%) 222 (51.8%)

TTL JEQT IEQT IEQT MFG

Strong 95 (61.3%) 92 (67.2%) 20 (20%) 0 (0%) 207 (48.2%)

TTH RDA SO JEQT∗IEQT∗ MFG∗ JV M&A

Total 155 137 100 37 429

χ2= 96.61, P < 0.01. TTH: strong-interaction technology transfer; TTL: weak-interaction technology

transfer; RDA: research and development agreement; SO: spin-off; JEQT: weak-interaction major-ity equmajor-ity investment; IEQT: weak-interaction minormajor-ity equmajor-ity investment; JEQT∗: strong-interaction majority equity investment; IEQT∗: strong-interaction minority equity investment; JV: joint venture; M&A: merge and acquisition; MFG: weak-interaction outsourcing production agreement; MFG∗: strong-interaction outsourcing production agreement; OTS: Others (including marketing agreement, property right agreement, multi-purpose consortium, human resource training agreement, production capacity share agreement, etc.).

Table 4. Type of organizational connections by country.

Types Taiwan USA Japan Europe Others Total

TTH 4 16 8 1 0 29 RDA 29 24 4 1 4 62 SO 4 0 0 0 0 4 TTL 15 27 11 2 5 60 JEQT 12 2 0 0 0 14 IEQT 26 4 0 0 1 31 JEQT∗ 13 4 0 0 0 17 IEQT∗ 20 9 0 0 0 29 JV 12 12 5 4 2 35 M&A 4 5 0 0 2 11 MFG 64 7 6 2 1 80 MFG∗ 7 9 4 0 0 20 OTHERS 14 15 2 3 3 37 Total 224 134 40 13 18 429

TTH: strong-interaction technology transfer; TTL: weak-interaction technology transfer; RDA: research and development agreement; SO: spin-off; JEQT: weak-interaction majority equity investment; IEQT: weak-interaction minority equity investment; JEQT∗: strong-interaction majority equity investment; IEQT∗: strong-interaction minority equity investment; JV: joint venture; M&A: merge and acquisition; MFG: weak-interaction outsourcing production agreement; MFG∗: strong-interaction outsourcing production agreement; OTS: Others (including marketing agreement, property right agreement, multi-purpose consortium, human resource training agreement, production capacity share agreement, etc.).

just passive technology receivers; they have shifted their roles to that of innovators as well. Particularly, ERSO is playing a major role in this regard. Investment interaction occurs largely in local companies (64.0%), then in Taiwan-American companies (25.7%), and very seldom in the other three countries. This is because there are a lot of fabless de-sign houses in both Taiwan and the United States that are major targets of investment. It is also because dense and strong personal networks in these two areas facilitate mutual investment links. However, our analysis finds that compa-nies from Japan, Europe, and other areas practice almost only joint venture agreements in their capital investment. This type of investment has the highest degree of organiza-tional interdependence, requiring very strong commitment

from collaborative partners and sharing of risks as well as profits. Why do they adopt this mode of organizational al-liance? One of the possible reasons is that companies from these countries lack ethnic or personal connections to func-tion as a supplementary mechanism to coordinate inter-firm interaction. All of the joint venture agreements between companies from these three areas and Taiwan’s companies happened only after 1990, except for the joint venture agree-ment between Philips and Taiwan’s governagree-ment. Therefore, we will argue that for relatively unfamiliar and late-coming partners, joint venture agreement is probably a good strat-egy to connect into Taiwan’s IC industrial network quickly and successfully. Joint venture agreement binds both part-ners tightly, which can curtail mistrust as well as strengthen commitment between unfamiliar collaborators.

The percentage of strong interaction connections is high-est between Taiwanese and American companies (63.4%), while it is lowest among Taiwan’s companies (42.0%). The percentages of Taiwan-Japan (52.5%) and Taiwan-Europe (46.2%) companies compose the middle ground.

Conclusion

The above analysis delineates the four major findings of our studies. First, the industrial system for Taiwan’s integrated circuit industry is basically a network organization, and it is not a vertical-integration system. Taiwanese IC compa-nies keep extending their inter-firm links with both local and global companies as the industry moves from its beginning stage to maturity. Apparently, networks are an important and dominant structure of governance among Taiwan’s IC companies.

Second, Taiwan’s industrial network is more than a re-gional network. That is far more than an industrial-district model can explain, because the organizational relationships of these networks are not limited to local connections. Tai-wan’s network includes a very balanced combination of local and global links that prevents the lock-in problems occurring in some other industrial districts. The local networks are

able to change flexibly because global links create a lot of alternative channels for marketing information, technology exchange and collaboration, customer-supplier production relationships, and investment opportunities.

Third, Taiwan’s IC industrial networks are based not only on strong ties but also on weak ties. This avoids the shortcomings of strong ties pointed out by social network literatures (Graher, 1993; Uzzi, 1997). In a very closed network, members tend to interact with each other rather than outsiders, and the network becomes a closed system that lacks external exchanges of resources, information, and partnerships. Moreover, its members tend to highly internal-ize the values and norms of the group, a process that is very likely to result in group thinking. A mixed mode of strong ties and weak ties keeps the openness and dynamic of the network.

Finally, the continuous expansion of industrial networks reflects the management strategies adopted by Taiwan’s IC companies. These companies vigorously seek opportuni-ties to establish inter-firm links because cooperation will increase the probability of the companies’ survival and suc-cess. In a very short product life cycle and fluctuating market, strategies of organizational connections help these companies to decrease risk and to gain necessary resources. Industrial latecomers such as Taiwan’s IC companies, es-pecially, need these different organizational connections to get technology, information, customers, capital, and human resources.

References

Amin A. and Thrift N., 1995: Globalization, institutional thickness and the local economy. In: Healey P., Cameron S. and Davoudi S. (eds),

Managing Cities: The New Urban Context. John Wiley and Sons,

Chichester.

Belussi F., 1996: Local systems, industrial districts and institutional net-works: Towards a new evolutionary paradigm of industrial economics?

Europ. Planning Studies 4(1): 5–26.

Braczky H.-J., Cooke P. and Heidenreich M. (eds), 1998: Regional

Innovation System. University College Press, London.

Chang P.L., Shih C.T. and Hsu C.W., 1993: Taiwan’s approach to techno-logical change: the case of integrated circuit design. Technol. Analysis

Strategic Manag. 5(2): 173–177.

Chen C.F. and Sewell G., 1996: Strategies for technological development in South Korea and Taiwan: the case of semiconductors. Res. Policy 25: 759–783.

Cooke P. and Morgan K., 1993: The network paradigm: new departures in corporate and regional development. Environ. Planning D, Society and

Space 11: 543–564.

Grabher G., 1993: The weakness of strong ties: the lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In: Gernot G. (ed.), The Embedded Firm:

The Social-Economics of Industrial Network. pp. 255–277, Routledge,

London.

Hagedoorn J., 1990: Organizational modes of inter-firm cooperation and technology transfer. Technovation 10: 17–30.

Henderson J., 1991: The Globalization of High Technology Production. Routledge, London.

Henry N., 1992: The new industrial spaces: locational logic of a new production era. Internal. J. Urban Regio. Res. 16: 375–396.

Hong S.G., 1992: The Politics of Industrial Leapfrogging: The

Semiconduc-tor Industry in Taiwan and South Korea. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

Northwestern University.

Hsu J.Y. 1997: A Late-Industrial District? Learning Network in the Hsinchu

Science-based Industrial Park, Taiwan. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

Department of Geography, University of California at Berkeley. Liu C.Y., 1993: Government’s role in developing high-technology industry:

the case of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. Technovation 13(5): 299– 309.

Mathews J.A., 1995: High-Technology Industrialization in East Asia: The

Case of Semiconductor Industry in Taiwan and Korea. Contemporary

Economic Issues Series, No. 4, Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, Taipei.

Mathews J., 1997: A Silicon Valley of the East: creating Taiwan’s semicon-ductor industry. California Manag. Rev. 39(4): 26–54.

Meaney C., 1994: State policy and development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. In: Aberbach J.D., Dollar D. and Sokoloff K.L. (eds), The Role

of the State in Taiwan’s Development. M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

National Science Council, Republic of China, 1997: White Paper on

Science and Technology. National Science Council, ROC, Taipei.

Pasek A., 1997: Binding Taiwan with science: the pivotal role of science-based industrial parks in Taiwan’s high-tech development. Topics Octo-ber: 54–57.

Rzco M., 1999: Competition, collaboration and the new industrial dis-tricts: examining the institutional turn in economic development. Urban

Studies 36 (5-6): 951–968.

Saxenian A., 1998: Hsinchu–Silicon Valley connection: ethnic ties in re-gional cooperation. paper presented at Tonghei University, Taichung, May.

Saxenian A. and Hsu J.Y., 1999: The Silicon Valley–Hsinchu connection: technical communities and industrial upgrading. Paper for International Symposium on East Asian Economy and Japanese Industry at a Turning

Point, sponsored by the Research Institute of International Trade and

Industry, Tokyo, Japan, 16–17 June.

Scott A., 1988: New Industrial Spaces: Flexible Production Organization

and Regional Development in North America and Western Europe. Pion,

London.

Sternberg R., 1996: Regional growth theories and high-tech regions. Intern.

J. Urban Regio. Res. 20(3): 518–538.

Storper M., 1997: Regional World. Guilford, New York.

Udo S., 1997: Specialization in a declining industrial district. Growth and

Change 28(4): 475–495.

Uzzi B., 1997: Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: the paradox of embeddedness. Administr. Sci. Quart. 42: 35–67.