A variety-increasing view of the development of the

semiconductor industry in Taiwan

Jian Hung Chen*, Tain Sue Jan

Department of Management Science, National Chiao-Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, 30050, Hsinchu, Taiwan Received 14 July 2003; received in revised form 4 June 2004; accepted 14 June 2004

Abstract

The development of the semiconductor industry depends on its interactions with the environment. Developing countries face more constraints and the environmental interactions seem more complicated. The development process of the semiconductor industry could be better understood with regard to the interactions and social changes. This study proposes a variety-increasing viewpoint based on the concepts of variety increasing and internal learning to analyze the developmental experience of the semiconductor industry in Taiwan. The result shows that the development of Taiwanese semiconductor industry is a continuous variety-increasing process, which is achieved by searching and establishing successful associations in an increasingly wider and complex environment. Implications on the ongoing development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry and the development experiences of other East Asian countries are discussed.

D 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Semiconductor Industry; Development; Variety increasing; Learning process

1. Introduction

The development of the semiconductor industry is a dynamic and complex process, which depends on the accumulation of technology, capital, and human resource in the industry. Latecomers from

0040-1625/$ - see front matterD 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2004.06.002

* Corresponding author.

developing countries where these resources are less available have more disadvantages[1]. The catch-up strategies of the latecomers depend on their country-specific circumstances and many environ-mental factors, like government policies, foreign technology sources, and other related industries

[2,3]. Different countries have different environmental situations, and each establishes different strategies to develop the semiconductor industry. Take the small tigers in East Asia for example. Large Korean corporations were capable to initiate the semiconductor industry by themselves; therefore, the Korean government supported the development by helping large corporations to obtain more financial support from government-controlled banks. Contrastingly, the industry firms in Singapore and Taiwan were less capable to initiate the development that both governments took initiatives to develop the semiconductor industry. The Singaporean government targeted on attracting direct investments from multinational companies, while the Taiwanese government focused on incubating and upgrading local firms. Different strategies of these countries have also led to different development results.

The development of the semiconductor industry in East Asia has been widely discussed in the literature. Some studies regarded the leading multinational companies as the driving force of the industrial development in East Asia, as described in the bflying-geeseQ theory [4,5]. The latecomers gained their positions by exploiting transient advantages, like lower costs, government policies, and heavy investments [6,7]. However, these approaches are not sufficient to explain the different performances of other developing countries and are unable to capture the complexity of the regionalization of industrial production [8]. On the other hand, Mathews and Cho [9] proposed a four-phase model to describe the development process of the semiconductor industry in East Asia, and illustrated the technology-leveraging and learning process through their expanding corn of capability enhancement.

Kim[10] proposed a three-stage technology learning process composed by the acquire–assimilate– improve loop and identified five important environment factors for the industry development. Koh[11]

investigated the learning processes of East Asian firms through Marquardt’s organizational learning model. Various other studies have also pointed out what and how the important roles like the government and public research and development (R&D) institutes assisted the industry development in these countries [12–15]. Although these studies provided many insights to the industrial development and technological learning process, there still lacks a proper conceptual framework to provide holistic and comprehensive understanding about the dynamic interactions between the industry and its environment throughout the development stages.

According to the experience of the semiconductor industry development in Taiwan, the industry emerged from the government initiatives and subsequently established connections to the domestic social–economic environment and then the international environment. It seems as if the industry continuously redefined its environment boundary according to the development progress. Furthermore, firms in the industry established different strategies to survive in different periods. These strategies were mutually dependant and related to the context of the environment [16]. It is argued that the industry development and technology learning process should be understood with regard to both the internal and external interactions of the industry system. This study proposed a conceptual framework based on the concepts of variety increasing to improve the understanding about the interactions, and introduced the concept of associator and memory in the living systems theory to identify the internal learning process of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry.

2. The proposed framework of industry development

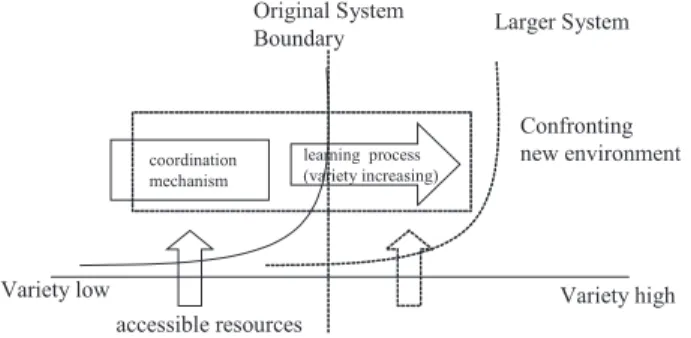

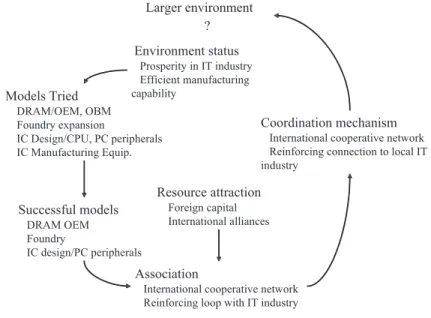

The development of the semiconductor industry depends on its interactions with the environment. This study proposed a framework shown inFig. 1based on variety and internal learning to understand the dynamic interactions of the industry development. The framework demonstrates that an industry system can exist with corresponding variety to the environment, while the variety can be increased through some learning processes for the association of system components and accessible environment factors. After the learning process, the industry system establishes a structure with higher variety, and thus becomes capable to extend its boundary and survive in a larger complex environment.

2.1. Variety and variety increasing

Variety is an essential concept in cybernetics. Ashby [17] developed the law of requisite variety, which asserts that a system must possess variety equal to or greater than that of its environment. For the industry system, Miles et al.[18]defined the industry variety as the strategic diversity among industry firms, and evaluated the variety in terms of key competitive factors, like production, marketing, and R&D characteristics. An industry with a wider spectrum of technologies, products, and market channels has the potential to generate a larger set of strategies to improve its competences and thus survives in a competitive environment. For the semiconductor industry, process technology, manufacturing efficiency, production capacity, and the control of industry standards are the key competitive factors, which can be characterized by intensity of circuit, die yield, number of wafer plants, and number of patents. Due to the rapid-changing nature of this industry, as described by Moore’s law[19], the ability to acquire necessary resources and maintain vast investments on R&D and manufacturing capacity is also essential.

For systems, displaying greater variety than any of its elements is called variety increasing [20]. A system can increase its variety either by including new components or by acquiring synergies emerged from proper interactions among system components [21]. In the industry system, examples of the synergies that emerged from interfirm interactions are common. For instance, firms may benefit from bborrowed experienceQ of other industry firms[22], and establish various alliances helping to overcome technological, financial, and market barriers [23]. Knowledge and information could diffuse through various industry consortia or strategic alliances, and thus allow firms with complementary skills to

capitalize on innovations[24]. In developing countries, the industry system may also incorporate some environmental factors, like government policies or leading multinationals, during the development process. Consequently, an industry with such self-organizing networks[25]coordinated as a whole could demonstrate a higher degree of variety than the firms can do alone. Such formal or informal interconnections of firms and other factors can be regarded as an internal coordination mechanism of an industry system through which the variety increasing is achieved.

The environment of a system lies outside the system’s control but determines in part how the system performs[26]. However, a system with increased variety may be able to influence some environmental factors, and thus extends its interactions to some previously inaccessible environment. For the semiconductor industry in late-coming countries, the environment of the industry may consist of government policies, public research institutes, leading multinational companies, and domestic or overseas market, capital, and human resources. Major environmental factors influencing the industry development could be different in different periods. Take Taiwan for example, Taiwan lacked development resources in the early stage that the industry relied on foreign investors and government initiatives to develop. The strategies available to the early semiconductor companies were limited within some back-end, labor-intensive manufacturing processes. The private sector was incapable to attract domestic resources at this moment, and relied on public research institutes to upgrade the technology. However, as the industry accumulated manufacturing capabilities and technologies in latter stages, the private sector was able to influence domestic capital and human resources flowing into the semiconductor industry, and engaged in numerous collaborative activities with leading international semiconductor companies.

2.2. Internal learning process

The learning process of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry for variety increasing is a coevolution of the association on internal coordination mechanism and the appreciation on the larger environment. The learning process could be elucidated by Miller’s two-stage learning concept.Fig. 2illustrated the learning process of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry.

Miller [27] proposed a two-stage learning process constituted by the associator and memory in his living systems theory. The associator carries out the first stage of learning process, forming enduring

associations among items in the system. The memory carries out the second stage of learning process, storing various sorts of information in the system for different periods. The learning process begins with a positive loop from which the system increases the variety of ways its inner items are associated, followed by a negative loop that converges various combinations to one that best fits the environment. After forming an enduring association, the system stores various information of the system by the memory, and reinforces the built-in mechanism for variety increasing.

In an industry system, industry firms would generate a variety of individual or collective strategies to survive. Improper models vanish, while successful models persist and attract other companies to imitate or enter related business. Business model and operating style of successful firms become the target of imitation, and consequently diffuse to other parts of the industry. The mainstream of the industry development thus emerges from the trial-and-error process taken by the industry firms, and subsequently establishes the industry networks and resource attraction mechanism. After the first stage of learning process, the industry establishes proper connections, what we call the coordination mechanism among industry firms and some environmental resources to survive in the current environment. Knowledge and experience gained from the exploration process would eventually embed in the market structures and industry practices. New entrants of the industry firms rapidly improve their competences by following the best practices and by taking advantage from existing industry networks. Finally, the industry system with the associated internal coordination mechanism continues to improve its efficiency and competence, which subsequently contribute to the potential of the industry firms to generate a larger set of strategies to explore in an expanded environment.

3. The Taiwan experience

Based on the proposed framework, this study analyzed the development experience of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry[28–30]. The development process revealed that the industry system competed for different environment resources in different periods to survive. Taiwan’s semiconductor industry relied on government support to initiate at first, and subsequently began to attract capital and human resources from domestic social–economic environment. Finally, the industry extended its interactions to the international environment to leverage international resources. According to the changes in the industry variety and environment interactions, this study identified three development stages, as illustrated inTable 1. The learning process in each stage is described as follows.

Table 1

Development stages of Taiwanese semiconductor industry Industry status Major factors for

variety increase

New status Larger environment factors

Stage 1 None Government policies Initial firms Domestic resources

Stage 2 Few small firms Domestic resources Vertical disintegrated industry system

International resources Stage 3 Well-established

manufacturing system

International resources International integrated industry network

Globalization of the private sector

3.1. Development Stage 1 (1960s–1970s)

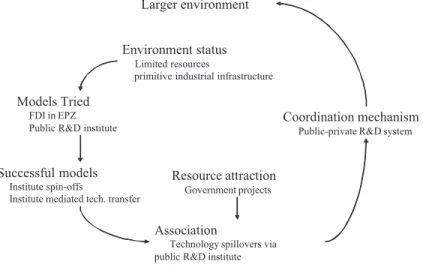

In the first stage, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry was initiated and nurtured by the government policies. After the learning process as illustrated inFig. 3, initial semiconductor manufacturing capacities were successfully established.

3.1.1. Environment status

Taiwan started its industrialization in the 1960s, and the economical and technological status of the private sector was insufficient to support the development of the semiconductor industry. On the other hand, the electronic industry in the United States was about to move its low-level manufacturing to other countries with lower costs, which provided opportunities for Taiwan to speed up the industrialization process by leveraging foreign investments.

3.1.2. Tries and selection

Due to the scarcity of development resources, Taiwanese government implemented the Export Processing Zones (EPZ) policy to attract foreign direct investments (FDI) from multinational corporations, and established public R&D institutes to assist the private sector to upgrade technology levels.

The EPZ policy successfully attracted some multinationals moving their labor-intensive manufactur-ing process to Taiwan, but the investments in semiconductor industry concentrated on low-end processes of Integrated Circuits (IC) packaging and testing. To introduce front-end IC fabrication technology to Taiwan, the government implemented a series of Electronics Industry Development Projects (EIDP) carried by a public R&D institute, the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI).

The EIDP Phase I wound up and span off into some earliest Taiwanese semiconductor companies, including the United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC) and several IC design companies. Because most local entrepreneurs of traditional industries lacked interests to invest, the government also helped the spin-off companies in raising initial capital from public funds and some private firms. These companies

soon began to make profits by producing control chips for electronic products, like telephone and watch.

3.1.3. Associating the coordination mechanism

The public–private R&D mechanism constituted by the ITRI and the industry firms was the major force to upgrade technologies in this stage. Because the industry firms did not have enough resources to develop new technology, the ITRI played the intermediate role to acquire technology either from foreign transfers or from government projects, and then transfer to the private sector. Moreover, ITRI established no barriers to employee resignation, which enhanced the technology diffusion through flows of personnel. The public–private R&D mechanism constantly assisted the private sector to improve its technology and skills.

3.1.4. Expansion of environment interaction

The dominating interactions in this stage came from the government and the industry firms. The public– private R&D system provided a technology-leveraging mechanism to the industry and thus successfully established the foundation of the semiconductor industry in Taiwan. Moreover, the initial success of the spin-off companies demonstrated the potential of further development in the industry, which subsequently attracted more domestic investors and entrepreneurs to start up new companies in the semiconductor industry. The development thus entered the second stage where the private sector began to grow.

3.2. Development Stage 2 (1980s)

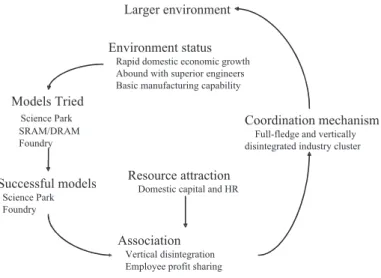

During the second stage, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry extended its interactions from the government and research institutes to the domestic social and economic environments. The industry explored various development strategies and established an effective resource attraction mechanism for domestic resources. After the learning process shown inFig. 4, the industry established a complete and vertically disintegrated industry cluster.

3.2.1. Environment status

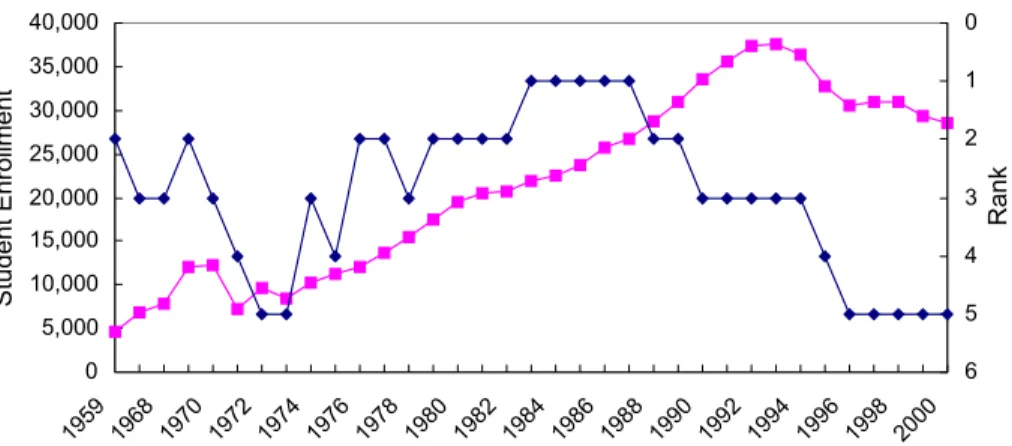

During the industrialization process, Taiwan accumulated a large amount of capital from long-lasting international trade surplus. Additionally, due to the preference of the Taiwanese society on science and engineering disciplines and the prevalence of going abroad to pursue advanced educations, there were many human resources of engineering accumulating domestically and overseas[31].Fig. 5demonstrated the enrollment of Taiwanese students in the United States from 1959 to 2000[32]. Notably, the number of Taiwanese students ranked higher than any other country from 1983 to 1987.

3.2.2. Tries and selection

3.2.2.1. The private sector. The initial success of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry attracted more companies entering the industry. Initially, the industry firms attempted to develop advanced products, such as UMC, Mosel in Static Random Access Memory (SRAM), Quasel, Vitelic in Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM), Advanced Device Tech. (ADT) in power transistors, and Advanced Semiconductor Engineering (ASE) in IC packaging and testing. However, the attempts in DRAM failed due to insufficient production capacity and financial support; the attempts in SRAM failed because the production technology was immature; and there was no significant growth in analog devices. The failure of DRAM stimulated the idea to establish shareable manufacturing facilities in Taiwan, and induced subsequent development toward niche products. For instance, Macronix chose specialized flash and Read Only Memory (ROM) as target, Silicon Integrated Systems (SIS) dedicated in designing Mask ROM, and Ali designed chips for domestic personal computer manufacturers.

3.2.2.2. The government. In this stage, Taiwan’s government assisted the development in two ways: the science park policy and the public research institute. The government implemented the science park policy and established the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park (HSIP) in 1980 to reinforce the emergence of industry cluster. Firms in the science park could receive tax discounts and improved infrastructure support. Notably, the government demanded that only locally owned companies could enter the science park. Although harmful to attract foreign investments, this restriction enforced Taiwan’s high-technology industries to develop autonomic competences.

On the other hand, the success of the public–private R&D model in the previous stage inspired the government to implement subsequent phases of EIDP to upgrade semiconductor technology. At the time the EIDP Phase III ended, the failure of the DRAM business in Taiwan triggered the demand for shareable fabrication facilities. Because independent upstream IC design companies and downstream IC packaging/testing companies already existed in the private sector, this project span off into the first foundry company, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC) and the first dedicated mask company, Taiwan Mask Corp. (TMC).

3.2.3. Associating the coordination mechanism

In this stage, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry successfully associated domestic development resources and established a vertically disintegrated industry structure. The emergence of a dedicated foundry company enabled the segmentation of the manufacturing process such that different companies handled different segments, like IC design, mask making, wafer fabrication, and IC packaging. Because Taiwan’s companies were generally too small to become integrated device manufacturers (IDM), they concentrated on partial segments and collaborated with each other to finish the complete IC fabrication process. Furthermore, the science park policy facilitated the formation of industry clusters, and the restriction that science park firms must be locally owned enforced industry firms to establish interconnections with other local firms.

After the initial public offering of UMC in Taiwan Stock Exchange in 1985, more and more high-tech companies went public and started to raise funds from the capital market. The resource attraction mechanism for the Taiwanese semiconductor industry on domestic capital and human resources thus became active. On the capital part, Taiwan’s investors look high to industries with high growth potentials, and prefer stock dividends than cash dividends. Consequently, high-tech companies with good prospect can easily raise funds from capital market and reserve their revenue for reinvestment instead of distributing to shareholders. On the human resources part, Taiwan’s high-tech industry established a unique employee profit-sharing system. Stockholders allow the company to allocate certain proportions of dividends to be distributed to employees in the form of stock. The market value of employee-shared stock may exceed US$60,000 per employee annually for a company with a high stock price. The huge compensation from the profit-sharing system attracted enormous local and even overseas human resources entering the industry to develop their careers.

3.2.4. Expansion of environment interaction

Supported by the effective resources attraction mechanism, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry established a complete, efficient, and vertically disintegrated manufacturing structure. Individual firms focused on specific segments of the manufacturing process, and altogether associated as an industry system with a vigorous manufacturing strength. The rising strength enabled the industry to establish reciprocal connections with Taiwan’s IT industry and leading multinational semiconductor companies. The development thus entered the third stage where the international interactions began to emerge.

3.3. Development Stage 3 (1990s)

Based on the established manufacturing strength and associated domestic resources, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry was able to interact with the international environment. After the learning

process shown in Fig. 6, the industry system rapidly expanded and upgraded, and embedded into international industry networks.

3.3.1. Environment status

In the 1990s, the rising threats of Korean DRAM industry pushed many DRAM manufacturers in Japan, Europe, and the United States to seek possible alliances. Moreover, the prosperity of Taiwan’s IT industry and the support of the foundry service provided development opportunities to the IC design industry.

3.3.2. Tries and selection

3.3.2.1. The foundry industry. The emergence of the foundry industry realized the concept of virtual-fab, which turned out to be flexible and efficient in Taiwan. Taiwan’s foundry companies actively tried to upgrade their technology in the 1990s. TSMC acquired the latest process technology by providing foundry services to leading multinationals, like Philips, NEC, AMD, and Fujitsu, in exchange for their technology transfer or license. UMC tried entering the CPU market, and released an 80486 compatible CPU in 1994, but finally failed due to patent problems. Inspired by the rising demand for the foundry service, UMC split its IC design businesses into individual design houses, and itself transformed into a pure-play foundry company by establishing joint ventures (JVs) with foreign fabless design companies in 1995. The fierce competition between TSMC and UMC forced the two companies to invest restlessly and thus became the top two foundry companies in the world.

3.3.2.2. The DRAM industry. The manufacturing strength and ample supply of capital in Taiwan attracted many foreign DRAM companies to cooperate in the 1990s. Taiwanese DRAM companies explored several strategies to establish their technology capacity. For instance, Mosel merged Vitelic to

start the DRAM R&D in 1991, but latterly changed the self-development strategy and established a JV with Siemens on 64M DRAM in 1996. Contrastingly, Vanguard, a spin-off from ITRI in 1994, relied on self-developed technology. Powerchip and Winbond adopted the DRAM OEM strategy and depended on their partners to upgrade their technology. NanYa Tech. licensed its initial 16M and 64M DRAM from Japanese firm OKI, while latterly switched to IBM for 64M to 256M DRAM licenses. The JV and OEM model were quite successful in this period, both the scale and technology of Taiwanese DRAM companies expanded tremendously. The technology-leveraging strategy was reciprocal to both sides that Taiwanese firms acquired the most advanced technology while the multinationals acquired production capacity. Notably, the failure of Vanguard on pure self-development model evinced the importance of technology support from industry leaders. After the increase on scale and technology, Taiwan’s DRAM companies also actively engaged in various joint-development activities for future technology.

3.3.2.3. The IC design industry. The demand from IT industry and the supply of efficient foundry service in Taiwan supported the development of Taiwan’s IC design industry. Taiwan’s IT manufacturing industry prospered and became worldly significant in the 1990s. The increasing demand for low-cost semiconductor products induced the proliferation of domestic IC design companies. These companies pursued quick-following strategies and established competences on lower cost and faster time to market. Many design companies were successful in producing chips for PC peripherals, such as Via, Sis, and Ali on PC chipsets, Mediatek on CD-ROM/DVD control IC, Realtek on network interface controllers, and Sunplus on control IC for digital camera and some electronic devices.

3.3.2.4. The government. Because the development of the private sector already exceeded the progress of government research projects, the government stopped to support research projects for process technology and turned to encourage the development of semiconductor manufacturing equipments. Some local companies tried to develop downstream manufacturing equipments, but such attempts failed to gain confidence of local buyers. The IC manufacturing equipment industry in Taiwan remained in downstream IC packaging and testing, and stayed in small scale.

3.3.3. Associating the coordination mechanism

In the 1990s, Taiwanese semiconductor industry rapidly upgraded its technology by establishing collaborative networks with leading multinationals, and the IC design industry successfully established reinforcing connections to Taiwan’s IT industry. Due to the increased variety in the private sector, Taiwan’s semiconductor companies were able to participate in international industry associations and embedded itself into the industry network. For instance, TSMC joined the International 300mm Initiative as a member of SEMATECH in 1996, and thus participated in the formulation and development of next-generation technologies. Moreover, Taiwan’s chipset manufacturers cooperated with second-liner CPU manufacturer AMD and Cyrix to extend the life cycle of the Socket-7 standard, and subsequently assisted on pushing the PC-133 SDRAM architecture into the mainstream over Intel’s Rambus architecture.

On the resource attraction part, Taiwanese semiconductor companies began to raise funds from overseas capital market. The scale of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry expanded tremendously in this stage. There were 27 new wafer plants established in Taiwan in the 1990s, including eighteen 8-in. plants; after 1995, the domestic resource supply became insufficient to support the expansion. The

increased international connections and the wide-spreading prominence of Taiwanese semiconductor industry enabled the industry firms to access overseas resources for expansion. For instance, the success of TSMC to issue and list its American Deposit Receipt (ADR) in the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) encouraged other Taiwanese semiconductor companies, like UMC, Macronix, and ASE, testing to raise funds and list their deposit receipt in global capital market, like NYSE or NASDAQ.

3.4. The continuous variety increasing process of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry

The development of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry is a continuous variety-increasing process as summarized in Fig. 7. The industry system increased its variety by continuously associating the industry firms and important environmental factors throughout the three development stages. After the learning processes, Taiwan successfully became the fourth largest semiconductor manufacturing country with the foundry industry ranked top, IC design ranked second, and DRAM ranked fourth in the world.

4. Ongoing development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry

As Taiwan is getting more important in the international semiconductor industry, the industry firms face more pressures to internationalize further. The ongoing development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry seems more complicated and is discussed in the following section.

4.1. New coming challenges

Taiwan’s semiconductor industry encountered a more complex environment for ongoing develop-ment. On one hand, following the variety-increasing processes, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry has subsequently changed its role from a follower, a partner, to a potential rival to the leading multinationals. Taiwan’s semiconductor companies have encountered more head-to-head competitions from both leaders and other latecomers. For example, the success of the foundry industry in Taiwan attracted many competitors from Korea, Singapore, Israel, and even leading multinationals, like IBM, entering the foundry market. Furthermore, some American companies accused Taiwanese memory manufacturers of SRAM dumping in 1997 and DRAM dumping in 1998. More and more lawsuits occurred between Taiwan’s semiconductor companies and foreign industry players. On the other hand, the industry ecology in Taiwan is under a transition. The IT manufacturing and downstream IC packaging and testing industries are moving to other low-cost countries, and the fast-growing TFT-LCD industry brought by the notebook PC industry in Taiwan aggravated the depletion of domestic capital and human resources.

4.2. The need for a new coordination mechanism

Taiwanese semiconductor companies have been more aggressive to overcome the difficulties and strive for further growth. Many companies attempted to acquire the latest technology and enter high-value products through mergers or establish overseas JVs. However, as the industry internationalizes to a deeper extent, the larger environment may have impacts on its original coordination mechanisms. For example, many foreign investors argued that the prevailing employee profit-sharing system in Taiwan is harmful to the shareholders’ benefits. Therefore, Taiwan’s semiconductor companies have to reconsider their compensation policies to balance from their domestic and overseas resource attraction strategies. Additionally, many Taiwanese companies began to establish overseas subsidiaries. The management also has to consider the cross-cultural or cross-national discrepancies among different areas. The deepening internationalization and the migration of the IT manufacturing industry may indicate that the regional interactions of Taiwan’s high-technology industries would probably transit from early Silicon Valley– Taiwan patterns to the triangles of Silicon Valley–Taiwan–China or the Silicon Valley–Taiwan– Southeast Asia interactions. As Taiwan’s semiconductor industry is striving for the fourth variety-increasing stage, a more globalized worldview and a new cross-border coordination mechanism would be important to handle the complex situations in the even more dynamic and internationalized environment.

5. Discussions on other Asian countries

The learning process of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry is a continuous trial-and-error exploration and appreciation toward larger environments. However, different countries have different environments, such that their development strategies also vary from each other. Among the late-coming countries, Korea and Singapore are also quite successful in the development the semiconductor industry. The learning process in Taiwan was more like a noxiant-avoiding approach[16], while the processes in Korea and Singapore were more like a goal-seeking approach. This study discussed their different development processes and finally discussed the potential development in China.

5.1. The Korean development process

The environment of South Korea in the early stage of semiconductor industry development also lacked proper technology and human resources. However, large Korean corporations were more capable to develop the industry by themselves. Unlike Taiwan’s trial-and-error learning, the Koreans decided to focus on DRAM manufacturing at beginning. The private sector acquired initial technology by licensing from companies in the Silicon Valley and recruited overseas engineers to establish the R&D foundation. The Korean government assisted the industry firms to get huge low-interest loans from banks that enabled the private sector to maintain its restless investment at market downturns. The Semiconductor Trade Agreement signed by Japan and the United States in 1986 restrained Japanese DRAM exports and gave Korea a great chance to siege the market and finally become the largest DRAM manufacturing country.

5.2. The Singaporean development process

Singapore is a city-state with a tiny area and a small population which limited its alternatives on industry development. Consequently, resource attraction is an important focus of its development policy. Singapore decided to develop its high-technology industry by leveraging foreign resources. The ability to attract FDI was critical to the leveraging strategy. The Singaporean government established industrial parks and well-appointed infrastructures to attract investments from multinational companies. Furthermore, the government not only encouraged multinationals to transfer technology or establish local supporting industry networks by tax incentives but also modified its immigration regulations to facilitate the inflow of technological human resources.

The Singaporean strategy successfully attracted foreign investments in downstream IC packaging and testing industry at first, and subsequently extended to some upstream DRAM and IC fabrication process when the industry status was improved. Moreover, the Singaporean government itself actively participated in establishing JVs with foreign companies to set up a local semiconductor company. For instance, Chartered was founded by the JV with National Semiconductor and Sierra, and SSMC was established by the JV with Philips and TSMC.

5.3. Possible development in China

The semiconductor industries in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore pursued different paths in their development process through different environmental interactions. However, China seems to have the potential to combine the different development models. First, China has a similar culture to Taiwan, and possesses a large amount of overseas students. Furthermore, Taiwan’s IT industry was migrating manufacturing process to less expensive areas, and China gradually became the major candidate for the transition. Taiwan’s IT companies are duplicating another Taiwan experience in China, where the industry cluster is emerging. Second, the economy growth of China began to boost after the bopen doorQ policy; the potential domestic market and cheap labor became important factors on investment decisions for multinationals. In fact, the strong magnetism effect of China already threatened many Asian countries, including Singapore, in attracting foreign investments. Finally, the government of China actively implemented policies, like the Special Economy Zones in the coastal areas and taxation discounts, to facilitate the industry development. Under the formal or informal support from the

government and domestic market, like the success of Legend and Haier in personal computer or consumer electronics market, China has the potential to develop large semiconductor companies. Combining the manufacturing abilities from Taiwan and the capital or technological investments from multinationals, the semiconductor industry in China is likely to achieve a high degree of variety so as to be competitive in the worldwide environment.

6. Conclusion

This study proposed a development framework for Taiwan’s semiconductor industry based on concepts of variety increasing and internal learning. According to the framework, the development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry is a continuous variety-increasing process achieved by searching and establishing successful associations among industry firms and important resources in an increasingly wider and complex environment. Three stages were identified from the development of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry according to the changes in industry variety and environment interactions. In the first stage, the industry successfully interacted with the government and established the initial semiconductor capacity in the private sector. In the second stage, the industry system further interacted with domestic social and economic environments, and gradually established a vertically disintegrated industry cluster. In the third stage, the industry system extended the interactions to the international environment, and established complex cooperative networks with leading multinationals. This study also discussed some considerations about the ongoing development of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry and the development process of semiconductor industries in South Korea, Singapore, and China.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

[1] M. Hobday, Innovation in East Asia: The challenge to Japan, Edward Elgar, Vermont, 1995, p. 33.

[2] C.J. Dahkman, B. Ross-Larson, L.E. Westphal, Managing technological development: Lessons from the newly industrializing countries, World Dev. 15 (6) (1987) 759 – 775.

[3] J.H. Chen, T.S. Jan, A system dynamics model of the semiconductor industry development in Taiwan, working paper, 2004.

[4] D.W. Edgington, R. Hayter, Foreign direct investment and the flying geese model: Japanese electronics firms in Asia-Pacific, Environ. Plann. A 32 (2) (2000) 281 – 304.

[5] P.J. Lloyd, The role of foreign investment in the success of Asian industrialization, J. Asian Econ. 7 (3) (1996) 407 – 433. [6] P. Krugman, The myth of Asia’s miracle, Foreign Aff. 73 (6) (1994) 62 – 78.

[7] G.R. Mitchel, Global technology policies for economic growth, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 60 (3) (1999) 205 – 214. [8] M. Bernard, J. Ravenhill, Beyond product cycles and flying geese: Regionalization, hierarchy, and the industrialization of

East Asia, World Polit. 47 (2) (1995) 171 – 209.

[9] J.A. Mathews, D.S. Cho, Tiger Technology: The Creation of Semiconductor Industry in East Asia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1999.

[10] L. Kim, From Imitation to Innovation: The Dynamics of Korea’s Technological Learning, Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA, 1997.

[11] A.T. Koh, Organization learning in successful East Asian firms: Principles, practices, and prospects, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 58 (1998) 285 – 295.

[12] R. Wade, Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1990.

[13] Y.H. Chu, The East Asian NICs: A state-led path to the developed world, in: B. Stallings (Ed.), Global Change, Regional Response: The New International Context of Development, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, pp. 199–237. [14] P.L. Chang, C.W. Hsu, The development strategies for Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 45 (4)

(1998) 349 – 356.

[15] M. Hobday, A. Cawson, S.R. Kim, Governance of technology in the electronics industry of East and South-East Asia, Technovation 21 (2000) 209 – 226.

[16] G. Morgan, Rethinking corporate strategy: A cybernetic perspective, Hum. Relat. 36 (4) (1983) 345 – 360. [17] W.R., Ashby, An Introduction to Cybernetics, Chapman and Hall and University Paperbacks, London (1964). [18] G. Miles, C.C. Snow, M.P. Sharfman, Industry variety and performance, Strateg. Manage. J. 14 (1993) 163 – 177. [19] B. Jovanovic, P.L. Rousseau, Moore’s law and learning by doing, Rev. Econ. Dyn. 5 (2) (2002) 346 – 375. [20] R.L. Ackoff, Towards a system of systems concepts, Manage. Sci. 17 (11) (1971) 661 – 671.

[21] R.L. Ackoff, Systems thinking and thinking systems, Syst. Dyn. Rev. 10 (2–3) (1994) 175 – 188. [22] A.S. Huff, Industry influences on strategy reformulation, Strateg. Manage. J. 3 (1982) 119 – 131.

[23] E. Esposito, Strategic alliances and internationalisation in the aircraft manufacturing industry, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 71 (2004) 443 – 468.

[24] F. Olleros, R.J. Macdonald, Strategic alliances: Managing complementarity to capitalize on emerging technologies, Technovation 7 (1988) 155 – 176.

[25] D.E. Kash, R. Rycroft, Emerging patterns of complex technological innovation, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 69 (2002) 581 – 606.

[26] C.W. Churchman, The Systems Approach, Dell Publishing, NY, 1981. [27] J.G. Miller, Living Systems, McGraw Hill, New York, 1978.

[28] ITRI. Yearbooks of semiconductor industry. Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taiwan, R.O.C., (Various years 1991–2003) (In Chinese).

[29] L.Y. Su, There were both stormy and sunny days—The 20 years path of ERSO, ERSO, Taiwan, R.O.C., 1994. (In Chinese).

[30] SIPA, 20th anniversary of HsinChu Science-Based Industry Park, SIPA, Taiwan, R.O.C, 2001. Also available at:http:// www.sipa.gov.tw/1/20th/index.html(In Chinese).

[31] P.L. Yu, C.Y. Chiang Lin, Five life experiences that shape Taiwan’s character, in: C.Y. Chang, P.L. Yu (Eds.), Made By Taiwan, World Scientific, Singapore, 2001, pp. 347 – 377.

[32] Bureau of International Culture and Education, Statistics of Taiwan overseas students, Ministry of Education, Taiwan, R.O.C. (In Chinese).

Jian Hung Chen is a researcher of the Industrial Economics and Knowledge Center of the Industrial Technology Research Institute in Taiwan. He is also a PhD Candidate of management science at National Chiao Tung University (NCTU). He has an MBA in information management.

Tain Sue Jan is an associate professor of the Department of Management Science at NCTU in Taiwan. He has a PhD in Management Science. His research interests include system dynamics, systems approach, and nonprofit organizations.