Work-Related Psychosocial Hazards and Arteriosclerosis A Cross-Sectional Study Among Medical Employees in a Regional Hospital in Taiwan

Li-Ping Chou,1,2 MD, Chung-Yi Li,2,3 PhD, and Susan C. Hu,2 PhD

From the 1 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Sin-Lau Hospital, 2

Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, and 3 Department of Public Health, College of Public Health, China Medical

University, Taichung, Taiwan.

Running Title: psychosocial hazards and arteriosclerosis

Address for correspondence:

Susan C. Hu, PhD. Associate Professor

Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University. No. 1, University Road, Tainan 70101, Taiwan.

Tel: +886-6-2384886 Fax: +886-6-2359033

Abstract

Objective: The association of psychosocial stress with cardiovascular

disease (CVD) is still inconclusive. This study aims to examine the relationships between arteriosclerosis with various work-related

conditions among medical employees with various job titles. Methods: A total of 576 medical employees in a regional hospital in Taiwan were enrolled with a mean age of 43 years and female gender dominance (86%). Arteriosclerosis was evaluated by brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV). Work-related conditions included job demands, job control, social support, shift work, work hours, sleep duration and mental health. The crude relationship betweeneach of the selected covariates and baPWV was indicated by Spearman correlation coefficients. Multiple linear regression model was further employed to estimate the adjusted associations of selected covariates witharteriosclerosis . Results: The mean baPWV of participants was 11.4 ± 2.2 m/s, with the male gender significantly higher than the female gender. The baPWV was associated with gender, age, medical profession, work hours, work type, depression, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fasting glucose and cholesterol. After being fully adjusted by these factors, only sleep duration of less than 6 hours and weekly work hours longer than 60 hours were significantly associated with increased risk of arteriosclerosis. The conditions of job demands, job control, job support, shift work, and depression showed no significant association with baPWV. Conclusion: Longer work hours and shorter sleep durations were associated with an increased risk of arteriosclerosis. These findings facilitate employers’ stipulation of rational work hours to avoid their employees’ development of CVD. Further longitudinal study is needed to confirm the causal

this study.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in most industrialized nations. Multiple risk factors predispose people to the progression of CVD. By controlling these risk factors, the incidence and mortality rate of CVD has been reduced in several developed countries in recent decades1-3.

Among these risk factors, psychosocial stress is noted as a wide-spreading phenomenon and plague in modern society. One large scale and world-wide case control study revealed psychosocial stress was attributed to 2.67 times risk of acute myocardial infarction which is more severe hazard than that of hypertension and diabetes4. Many work-related

psychosocial stressors are associated with CVD. Karosak et al.

commenced a pioneer work and developed the dominant demand-control model (DCM) approximately three decades ago to study work-related stress5. Work characteristics of low decision latitude and high work load

will result in high job strain. Job strain will increase by 23% the risk of incident coronary heart disease compared to no job strain in large pooled data6. Recently, long work hours7-10, shift work11, short sleep hours12 13,

and depression14 were also considered to be emerging work-related

hazards leading to CVD.

Despite the enormous number of papers that have explored the association between job stress and CVD over these three decades, the results are heterogeneous6 15. Most of these studies come from

observational data and nearly half of the results are negative or even in inverse relation between job stress and CVD. There are several inherently

methodological limitations in these studies. One of the most important reasons is the causality between the exposure of stress and the outcome of CVD is a long process and difficult to confirm because atherosclerosis is a pivotal pathological mechanism of CVD and it always progresses very slowly16. So, recently there has been growing research efforts focused on

the subclinical change of CVD including carotid intima-media thickness17 18, coronary calcium score19, and arterial stiffness20 21 as the study

surrogate endpoint.

Arteriosclerosis reflects the fibrotic change and poor compliance of arterial vessels, which represents vascular damage and becomes an

independent risk factor of CVD22. There are several methods to measure

arterial stiffness; among those, pulse wave velocity (PWV) is a simple and noninvasive measurement which has become a popular screening method in recent years23. A newly developed method of PWV with less

time consuming and less skill-dependant technique is brachial-ankle PWV (baPWV)24. baPWV is associated with age, gender, risk factors of

CVD, and Framingham risk score, and has been shown to an good independent predictor of coronary artery disease25-29. One recent

meta-analysis, which collected 18 prospective cohort studies with a total of 8,169 participants and a mean follow-up of 3.6 years, revealed baPWV can predict total cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. The pooled relative risks were 2.95 (95% CI, 1.63-5.33), 5.36 (95% CI, 2.17-13.27), and 2.45 (95% CI, 1.56-3.86) separately30.

The value of baPWV indicates the severity of arteriosclerosis, which is considered to be an early marker of atherosclerosis and is related to later

cardiovascular disease. It is anticipated that measuring baPWV and adjusting the potential risk factors of CVD may enable us to clarify the mechanism of occupational hazards and CVD.

Only two studies have explored the association between psychosocial stress and arteriosclerosis evaluated by baPWV. Both of these studies came from Japanese subjects20 21. In addition, these papers only used

Karasek’s demand control model and/or Siegrist’s effort reward imbalance model as their independent factors. However, many other work-related hazards including long work hours, shift work, short sleep duration and psychological problems may also relate to CVD, but have never been studied. To our knowledge, there was no such report on Taiwan’s employees, especially those who worked in hospitals. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between multiple work-related hazards and arteriosclerosis among medical employees in Taiwan.

Methods

Participants and study design

This is a cross-sectional study design. The volunteer participants were

recruited from a regional hospital in Tainan, Taiwan. The hospital had 1,490 hospital employees including 150 physicians, 600 nurses and 740 other medical employees. In May 2013, the hospital administrators conducted a social epidemiologic survey to explore the job-related stressors and health conditions among the employees before the

implementation of health-promotion programs. There were 1,329 medical employees who completed the electronic questionnaire (response rate of 89%). Among them, 676 volunteers were measured for arteriosclerosis. We then defined the valid blood sampling period for glucose and

cholesterol should be within 6 months. Finally, 576 professionals were selected as subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Sin Lau Hospital (SLH-919-104-01).

Measurement of arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis was measured by non-invasive methods with an

automatic waveform analyzer (VaSera VS-1000, Fukuda Denshi, Japan). The measurement of arterial stiffness was performed between 12:00 and 14:00 p.m. by experienced technicians. The participants laid on beds for at least 5 minutes, and then the cuffs were wrapped on both sides of their brachia and ankles together. To obtain baPWV, pulse volume wave forms of the brachial and tibia arteries were recorded simultaneously. Path

lengths from the heart to the ankle and from the heart to the brachium were marked as La and Lb. La-Lb represents the distance between brachium to ankle and is calculated as the following formula: La-Lb = 0.59 x body height (cm) + 14.4 (modified from Kitahara et al) 31. The

time interval between brachium and ankle is expressed as △Tab. The baPWV was then calculated as follows: baPWV = (La-Lb)/△Tab. The higher the value of baPWV means the more the severity of the

arteriosclerosis. In this study, we selected the higher of the right- or left-sided baPWV for our analyses.

Socio-demographics, work characteristics

The self-administered questionnaire used in this study included

socio-demographic information and work characteristics. Socio-socio-demographic information consisted of gender, age, educational level, marital status and medical profession. Work characteristics included work hours, work type, and sleep hours. Work hours were calculated as average work hours per week in the previous month, and were classified as ≦40 h, 41-49 h, 50-59 h, and ≧ 60 h. Work type included fixed day work, fixed night work, and shift work. Sleep hours were categorized as <6 h, 6-8 h, and >8 h in everyday sleep.

Measurement of job stress

A Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (C-JCQ) was chosen to measure job strain.C-JCQ is derived from the Karasek’s Demand-Control-Support model and has been validated and used well

with Taiwanese subjects32 33.Job demands, mean work load and job

control represent decision latitude. As in Karasek’s model, works possess the characteristics of high job demand and low job control resulted in high job strain, which, in turn, creates the highest risk of CVD. Social support was an effect modifier and was later added in the domain of the demands control model. Therefore, C-JCQ consisted of 3 subscales: 9 questions on job demands, 8 questions on job control and 8 questions on social support. Each question was measured on a four-point scale. The scores of job demands and control were calculated separately and divided into tertiles to indicate high, medium and low in this study. The scores of social support were expressed as high (score ≧ 24) and low (score < 24). Detailed descriptions of the C-JCQ can be seen in a previously published paper34.

Measurement of mental health

Because the way of emotional expressions varies with culture, we used the “Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire” (TDQ) to screen the

prevalence of depression in our study participants. The 18-item TDQ was with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.89 and 0.92, respectively at the cutoff score of 19. It was superior to the Beck Depression Inventory in detecting depressive patients in Taiwan35 36. So, for this study we selected

a cut-off point score of ≧ 19 to indicate the presence of depression.

Cardiovascular risk factors survey:

fasting glucose, total cholesterol and hypertension, all of which were obtained from employees’ health profiles. Smoking status was classified as “current/or ex-smoking” or “never.” The BMI was measured as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of body height in meters (kg/m2). Measurements of fasting glucose and total cholesterol use

standard laboratory techniques. Three well-trained technicians were assigned to measure blood pressure using the AHA guideline37 with a

noninvasive electronic device, the Omron HEM-7230. Coffee, tea and tobacco were forbidden to be used for 30 minutes before the

measurement. Each patient was seated with his or her back supported and hands put on a desk with support. The cuff bladder was fastened on the upper arm at the level of the heart and both feet were lying flat on the floor for at least 5 minutes in a quiet room. At least two measurements of blood pressure were taken each time, separated by at least 1 minute. The average of the two measurements was used as the study variable.

Statistical analysis

All the variables were recorded as mean + standard deviations or percentages. χ2 and one-wave ANOVA were used to test the difference in

characteristics between male and female participants. The c Spearman correlation coefficients were used to explore the associations between selected covariates and baPWV. A multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify the job-related factors significantly associated with arteriosclerosis. Model 1 included only job-related factors in the model.. Model 2 further included age, gender, education and medical profession

in the model. Model 3 further adjusted smoking, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting sugar, as well as total cholesterol in addition to those variables adjusted in Model 2. All statistical analyseswere performed using a software SPSS version 17, with the level of significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

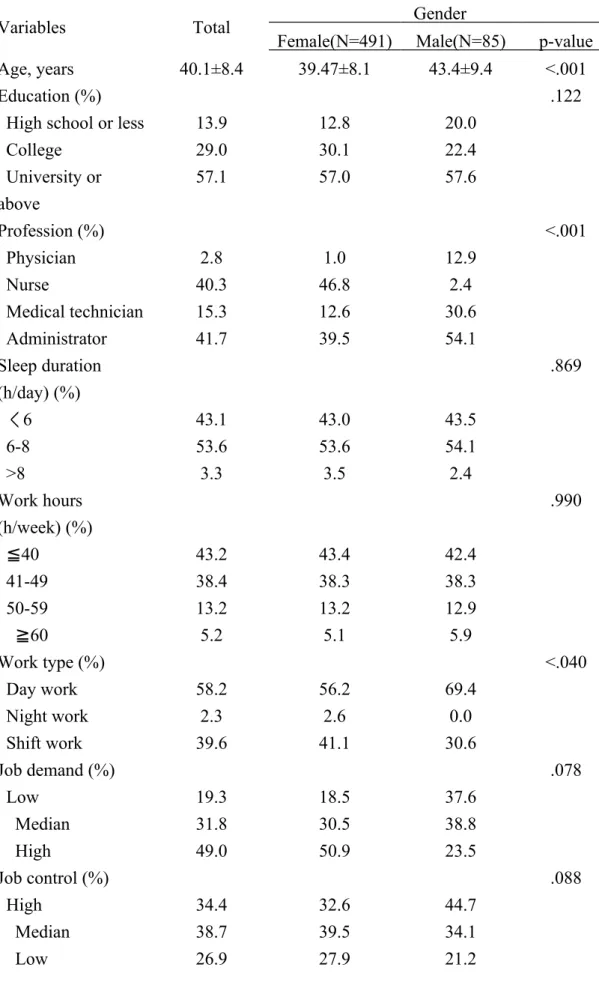

The socio-demographic factors, job- related psychosocial factors, cardiovascular risk factors, mental health and pulse wave velocity of participants by total and gender are summarized in Table 1. The participants were female dominant (86.6%). The mean age across

subjects was 40.5 years and males were 4 years older than females. Most nurse professionals were female and physicians were male. There were no significant gender differences with respect to education, sleep

duration per day, proportion of extra work hours and shift work, severity of mental health, and values of fasting glucose and cholesterol. Females had significantly lower social support (45.8% versus 25.9%, p < 0.001). At the same time, females had a significantly lower frequency of current smoking, lower body mass index, and systolic and diastolic blood

pressure than males. Moreover, the value of baPWV was lower in females (p < 0.001).

Factors associated with arteriosclerosis (baPWV)

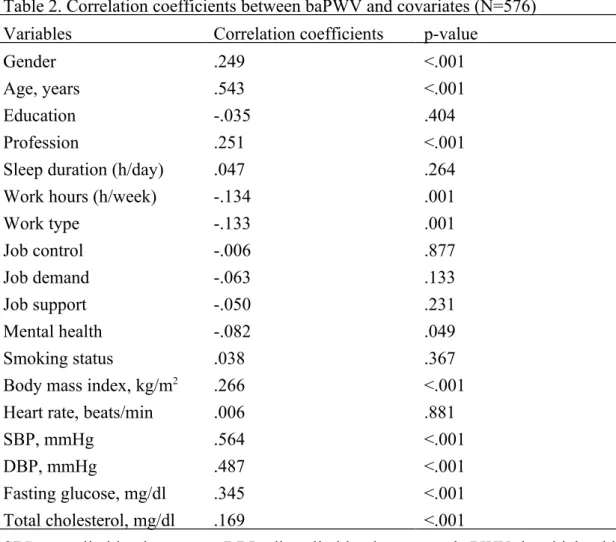

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between study factors and

baPWV. The results demonstrate that baPWV was strongly associated with gender, age, profession, work hours, work type, and all the

traditional cardiovascular risk factors except smoking. There was a weak association between baPWV and mental health. Unexpectedly, we noted that baPWV was not significantly with job demand, job control, social

support and heart rate.

Work- related hazards and arteriosclerosis (baPWV)

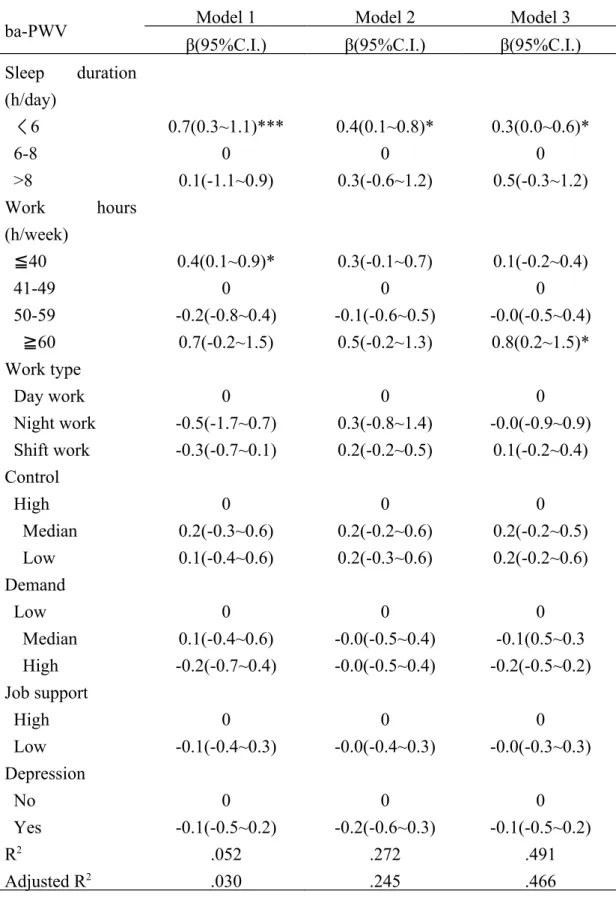

The associations between work-related factors and arteriosclerosis are

shown in Table 3. When all the work-related hazards were examined simultaneously, the results showed that the study participants whose daily sleep is less than 6 hours had a significantly higher baPWV, as compared to those who had a sleeping time of 6-8 hours. Furthermore, those with work hours less than 40 hours per week, as compared to work of 41-49 hours weekly, were also significantly associated with a higher baPWV. There was a U-shaped relationships ofbaPWV with both sleep duration and work hours per week ( Model 1). In Model 2, after being adjusted by age, gender, education and profession, only those who had a sleep duration of less than 6 hours every day showed a significantly higher baPWV.. In the full model (Model 3) that was further adjusted by cardiovascular risk factors, the results revealed that participants who had a sleep duration of less than 6 hours per day experienced only a

marginal, but significantly, effect as compared to those who sleep 6-8 hours ( β = 0.3, 95% CI 0.0~0.6, p = 0.025). Those with a weekly work time of more than 60 hours were also at an increased risk of

arteriosclerosis as compared with those with work hours between 41-49 hours (β = 0.8, 95% CI 0.2~1.5, p = 0.012). Surprisingly, shift work, job control, job demands, social support and depression all showed no

significant association with baPWV in the regression models. The full model can explain about half of the variance of baPWV (R2= 0.491;

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the relationship between work-related

conditions and arteriosclerosis in Taiwanese medical employees. The main findings showed that after adjusting all co-variables, only short sleep duration (< 6 h/day) and long work hours (> 60 h/week) are associated with a higher risk of arteriosclerosis evaluated by baPWV. These associations have showed non-linear (U-shaped) relationships and with only marginal effect. As to other work-related hazards including high job demand, low job control, low social support, doing shift work or night work and depression all demonstrated no correlation to

arteriosclerosis.

Only two papers from Japanese subjects have addressed the same relationship between work-related hazards and arteriosclerosis as this study. The first one is a cross-sectional study conducted on 396 young Japanese male workers. After full adjustment of cardiovascular risk factors and control of psychological responses, job strain demonstrated a negative association to baPWV, which is inconsistent with the previous results20. Another study is a large-scale screening conducted on 4,266

subjects (80% male) who worked in local government. The results show that high job strain is only associated with high baPWV in women, and high job demand is not related to either genders21. The same results are

also seen in CARDIA study19 in Americans, which indicated low job

control, high job demands and job strain were not associated with

study to examine the relationship between occupational hazards and acute coronary heart disease in male Taiwanese showed that longer work hours (> 60 h/w) and shorter sleep duration (< 6 h/d), but not job demands, job control, and shift work, have a significant increase in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (odd ratio 2.7 and 3.3, separately)38.

These findings were compatible with our study’s results. The above evidences raise the suspicion that work time and sleep duration may be more suitable occupational variables, especially for Asian and modern societies, than traditional stress models of work load and decisional latitude to evaluate the early vascular damage of atherosclerosis.

However, this inference and its possible biological mechanism need more research for clarification.

Long work hours are associated with stress, dissatisfactions, unhealthy lifestyle, and adverse health outcomes such as hypertension, sleep disorders, musculoskeletal problems, psychological problems and unhealthy lifestyles8 39 40. Moreover, overtime work increases the risk of

cardiovascular disease. Vertinan M has conducted a meta-analysis that included 12 trials with a total of 22,518 participants. It concluded that the relative risk of coronary heart disease for long work hours is between 1.80 and 1.59 (minimally to maximally adjusted analysis). Furthermore, results from the longitudinal follow-up studies show employees with long work hours possess about a 40% risk of coronary heart disease41.

This study showed overtime work is associated with a higher risk of arteriosclerosis. Indeed, overtime work is very common in East Asian countries, including Taiwan. The term of “Karoshi,” which means death

from overwork, was first reported in Japan in 196942. Over the subsequent

decades, the Japanese government has taken the initiative to bring down the number of work hours to improve the health of employees and their quality of life. Japanese worked an average of 1,745.2 hours a year in 2012. At the same time, the annual working time of Taiwan’s employees was 2,140.8 hours, which is much longer than those in Western countries such as the United States, Canada, England and Germany, whose

employees worked between 1396.6 and 1789.9 hours43 44. So, in Taiwan

and other East Asian countries such as Singapore and Hong Kong, the issue of work overtime being a threat to the workers’ health can never be overemphasized and is not yet resolved.

Sleep duration is another risk for CVD. Previous studies elucidate that both short and long sleep durations are associated with the incidence of and mortality from cardiovascular disease12 13. From the data of a large

Japanese prospective cohort study12, a total of 98,634 participants with

mean follow-up of 14.3 years, demonstrated that, as compared with sleep of 7 hours, sleep durations of 4 hours or less are associated with increased mortality from coronary artery disease, as well as all causes of mortality in both genders. The hazard ratios were 2.32 (95% CI, 1.19-4.50) for coronary artery disease in women; they were 1.29 (1.02-1.64) and 1.28 (1.03-1.60) for all causes of mortality in men and women, respectively. On the other hand, sleep durations of 10 hours or longer were associated with 1.5- to 2-fold increases in mortality from total and ischemic stroke, total cardiovascular disease and all causes for women and men, compared with 7 hours of sleep. Previous research from the Whitehall II cohort

study and Japanese cohort studies all yielded a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality from cardiovascular disease, with the lowest one at 7 hours of sleep12 45 46. Our study’s findings also showed

the trend of sleep times of less than 6 hours or longer than 8 hours increased the risk of arteriosclerosis when compared with sleep of 6-8 hours, although there was no statistical significance on sleep time more than 8 hours.

Using baPWV to assess arteriosclerosis by autonomic machine is considered a simple and reliable method. Yamashima has reported that baPWV was not only correlated well to the invasive method of aortic PWV (r = 0.87), but also has high reproducibility with Pearson’s

correlation coefficient of inter-observer (r =0.97) and intra-observer (r= 0.87)24. In our study, the value of baPWV had strong association with

age, gender, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fasting glucose and cholesterol. These results were consistent with the previous reports25-28 and support the evidence that baPWV is a reliable

predictor of arteriosclerosis, even for Taiwanese.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report to explore the relationship of work-related psychosocial hazards and arteriosclerosis evaluated by baPWV in Taiwan. Furthermore, this may be the first report on the linkage of job stress and pre-clinical

cardiovascular disease in medical employees in the world. We have comprehensively adjusted all the traditional cardiovascular risk factors and mental health to avoid possible confounders. This adjustment can improve the validity of the results. In addition, we also examined most of

the work-related hazards including job demands, job control, social support, shift work, mental health, sleep duration and work hours at the same time in our analysis.

Several limitations should be addressed in this research. First, although the measurement of baPWV is a simple technique with good reliability and reproducibility, its calculation of path length comes from a height-based formula rather than actually measuring the distance from brachial to ankle. Also, this formula is derived from the anthropometric data of the Japanese population. So, systemic errors due to the baPWV tool may be produced. However, the body height of Taiwanese is similar to that of Japanese. This characteristic can mitigate the level of error found when Western countries use baPWV. Second, the subjects of this study are sampled from medical employees; the results should not be inferred to other occupational workers. Third, although the sample size is modest and female gender is dominant (80%), we only show the results that amalgamate both genders. However, our final results (Table 3) have adjusted the gender factor to decrease this effect. Finally, the inherent shortcoming of a cross-sectional survey may weaken the causal

relationship between work-related hazards and arteriosclerosis. Therefore, further longitudinal study is needed to confirm these relationships.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that only short sleep duration and long work hours increase the risk of arteriosclerosis measured by baPWV. Other occupational hazards including high work load, low job control, low job

support, doing shift work, and depression were not correlated to early atherosclerosis. These findings facilitate the employer or government to stipulate rational work hours for avoiding their employees’ development of cardiovascular disease. Further longitudinal study is warranted to elucidate the relationship between work-related hazards and

Reference

1 Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction the American Heart Association’s Strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond.

Circulation 2010;121:586-613.

2 Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;127:e6-e245.

3 Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. New England Journal of Medicine

2007;356:2388-2398.

4 Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the

INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet 2004;364:937-952. 5 Karasek Jr RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain:

Implications for job redesign. Administrative science quarterly 1979:285-308. 6 Kivimäki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD et al. Job strain as a risk factor for

coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. The Lancet 2012;380:1491-1497.

7 Kang MY, Park H, Seo JC et al. Long working hours and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. J Occup Environ Med 2012;54:532-7.

8 Kang MY, Cho SH, Yoo MS, Kim T, Hong YC. Long working hours may increase risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Ind Med 2014;57:1227-34. 9 Jeong I, Rhie J, Kim I et al. Working hours and cardiovascular disease in

Korean workers: a case-control study. J Occup Health 2014;55:385-91.

10 Knutsson A, Hallquist J, Reuterwall C, Theorell T, Akerstedt T. Shiftwork and myocardial infarction: a case-control study. Occupational and environmental

medicine 1999;56:46-50.

11 Charles LE, Fekedulegn D, Burchfiel CM et al. Associations of work hours with carotid intima-media thickness and ankle-brachial index: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Occup Environ Med 2012;69:713-20.

12 Ikehara S, Iso H, Date C et al. Association of sleep duration with mortality from cardiovascular disease and other causes for Japanese men and women:

13 Sabanayagam C, Shankar A. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep 2010;33:1037-1042.

14 Dietz LJ, Matthews KA. Depressive symptoms and subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 2011;48:579-584.

15 Backé E-M, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K, Schumann B. The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. International archives of occupational and environmental

health 2012;85:67-79.

16 Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE et al. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on

Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 1995;92:1355-1374.

17 Fujishiro K, Diez Roux AV, Landsbergis P et al. Associations of occupation, job control and job demands with intima-media thickness: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Occup Environ Med 2011;68:319-26. 18 Rosvall M, Östergren P-O, Hedblad B, Isacsson S-O, Janzon L, Berglund G.

Work-related psychosocial factors and carotid atherosclerosis. International

journal of epidemiology 2002;31:1169-1178.

19 Greenlund KJ, Kiefe CI, Giles WH, Liu K. Associations of job strain and occupation with subclinical atherosclerosis: The CARDIA Study. Annals of

epidemiology 2010;20:323-331.

20 Nomura K, Nakao M, Karita K, Nishikitani M, Yano E. Association between work-related psychological stress and arterial stiffness measured by brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity in young Japanese males from an information service company. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005;31:352-9.

21 Utsugi M, Saijo Y, Yoshioka E et al. Relationship between two alternative occupational stress models and arterial stiffness: a cross-sectional study among Japanese workers. International archives of occupational and

environmental health 2009;82:175-183.

22 Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation

1999;99:2434-2439.

23 Mitchell GF, Hwang S-J, Vasan RS et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2010;121:505-511.

measurement. Hypertension Research 2002;25:359-364.

25 Tomiyama H, Yamashina A, Arai T et al. Influences of age and gender on results of noninvasive brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity measurement—a survey of 12 517 subjects. Atherosclerosis 2003;166:303-309.

26 Fujiwara Y, Chaves P, Takahashi R et al. Relationships between brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and conventional atherosclerotic risk factors in community-dwelling people. Prev Med 2004;39:1135-42.

27 Hung CS, Lin JW, Hsu CN et al. Using brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity to associate arterial stiffness with cardiovascular risks. Nutrition, Metabolism

and Cardiovascular Diseases 2009;19:241-246.

28 Choi K, Lee K, Seo J et al. Relationship between brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and cardiovascular risk factors of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes

research and clinical practice 2004;66:57-61.

29 Imanishi R, Seto S, Toda G et al. High brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the presence of coronary artery disease in men.

Hypertens Res 2004;27:71-8.

30 Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, Ioakeimidis N,

Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hypertension 2012;60:556-62.

31 Kitahara T, Ono K, Tsuchida A et al. Impact of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and ankle-brachial blood pressure index on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:688-96.

32 Yeh WY, Cheng Y, Chen CJ, Hu PY, Kristensen TS. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Copenhagen burnout inventory among employees in two companies in Taiwan. Int J Behav Med 2007;14:126-33.

33 Yeh W-Y, Cheng Y-W, Chen M-J, Chiu AW-H. Development and Validation of an Occupational Burnout Inventory. Taiwan public health association 2008;27:349-364.

34 Chou L-P, Li C-Y, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan.

BMJ open 2014;4:e004185.

35 Lee Y, Yang M, Lai T, Chiu N, Chau T. Development of the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire. Chang Gung medical journal 2000;23:688-694. 36 Lee Y, Lin PY, Hsu ST, Cing-Chi Y, Yang LC, Wen JK. Comparing the use

of the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory for screening depression in patients with chronic pain. Chang Gung Med J

37 Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education

Subcommittee. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2005;7:102-109.

38 Cheng Y, Du C-L, Hwang J-J, Chen I-S, Chen M-F, Su T-C. Working hours, sleep duration and the risk of acute coronary heart disease: a case–control study of middle-aged men in Taiwan. International journal of cardiology 2014;171:419-422.

39 Sparks K, Cooper C, Fried Y, Shirom A. The effects of hours of work on health: a meta‐analytic review. Journal of occupational and organizational

psychology 1997;70:391-408.

40 (NIOSH) TNIfOSaH. Overtime and Extended Work Shifts: Recent Findings on Illnesses, Injuries and Health Behaviors 2004.

41 Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M et al. Long working hours and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:586-96.

42 Nishiyama K, Johnson JV. Karoshi—death from overwork: occupational health consequences of Japanese production management. International

Journal of Health Services 1997;27:625-641.

43 Ministry of labor, Republic of China (R.O.C). Average Annual Hours Actually Worked Per Person in Employment. http://statdb.mol.gov.tw/html/ nat/Table %206-1.pdf 2013.

44 OECD. Average annual hours actually worked per worker, http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx? DataSetCode=ANHRS 2012.

45 Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP et al. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep 2007;30:1659-66.

46 Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep 2004;27:51-4.

Table 1 Characteristic of study participants (N= 576)

Variables Total Gender

Female(N=491) Male(N=85) p-value

Age, years 40.1±8.4 39.47±8.1 43.4±9.4 <.001

Education (%) .122

High school or less 13.9 12.8 20.0

College 29.0 30.1 22.4 University or above 57.1 57.0 57.6 Profession (%) <.001 Physician 2.8 1.0 12.9 Nurse 40.3 46.8 2.4 Medical technician 15.3 12.6 30.6 Administrator 41.7 39.5 54.1 Sleep duration (h/day) (%) .869 <6 43.1 43.0 43.5 6-8 53.6 53.6 54.1 >8 3.3 3.5 2.4 Work hours (h/week) (%) .990 ≦40 43.2 43.4 42.4 41-49 38.4 38.3 38.3 50-59 13.2 13.2 12.9 ≧60 5.2 5.1 5.9 Work type (%) <.040 Day work 58.2 56.2 69.4 Night work 2.3 2.6 0.0 Shift work 39.6 41.1 30.6 Job demand (%) .078 Low 19.3 18.5 37.6 Median 31.8 30.5 38.8 High 49.0 50.9 23.5 Job control (%) .088 High 34.4 32.6 44.7 Median 38.7 39.5 34.1 Low 26.9 27.9 21.2

Job support (%) .001 Low 42.9 45.8 25.9 High 57.1 54.2 74.1 Current/or ex- smoking (%) <.001 No 94.1 98.2 70.6 Yes 5.9 1.8 29.4

Body mass index, kg/m2 22.7±3.6 22.4±3.5 24.8±3.5 <.001 Heart rate, beats/min 82.4±14.1 82.6±13.4 81.0±18.1 .331 SBP, mmHg 125.9±16.7 124.2±16.3 135.5±16.1 <.001 DBP, mmHg 79.4±11.3 78.7±11.3 83.6±10.2 <.001 Fasting glucose, mg/dl 72.2±46.1 71.6±46.0 76.0±46.4 .409 Total cholesterol, mg/dl 149.9±88.2 148.5±87.2 158.4±93.9 .337 Mental Health 12.5±8.7 12.7±8.9 11.1±7.7 .111 baPWV, m/s 11.4±2.2 11.2±2.0 12.7±2.9 <.001

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; baPWV: brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

Table 2. Correlation coefficients between baPWV and covariates (N=576) Variables Correlation coefficients p-value

Gender .249 <.001

Age, years .543 <.001

Education -.035 .404

Profession .251 <.001

Sleep duration (h/day) .047 .264

Work hours (h/week) -.134 .001

Work type -.133 .001 Job control -.006 .877 Job demand -.063 .133 Job support -.050 .231 Mental health -.082 .049 Smoking status .038 .367

Body mass index, kg/m2 .266 <.001

Heart rate, beats/min .006 .881

SBP, mmHg .564 <.001

DBP, mmHg .487 <.001

Fasting glucose, mg/dl .345 <.001

Total cholesterol, mg/dl .169 <.001

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; baPWV: brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

Table 3. Multiple linear regression analysis of job related factors in association with baPWV (N=576)

ba-PWV Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

β(95%C.I.) β(95%C.I.) β(95%C.I.)

Sleep duration (h/day) <6 0.7(0.3~1.1)*** 0.4(0.1~0.8)* 0.3(0.0~0.6)* 6-8 0 0 0 >8 0.1(-1.1~0.9) 0.3(-0.6~1.2) 0.5(-0.3~1.2) Work hours (h/week) ≦40 0.4(0.1~0.9)* 0.3(-0.1~0.7) 0.1(-0.2~0.4) 41-49 0 0 0 50-59 -0.2(-0.8~0.4) -0.1(-0.6~0.5) -0.0(-0.5~0.4) ≧60 0.7(-0.2~1.5) 0.5(-0.2~1.3) 0.8(0.2~1.5)* Work type Day work 0 0 0 Night work -0.5(-1.7~0.7) 0.3(-0.8~1.4) -0.0(-0.9~0.9) Shift work -0.3(-0.7~0.1) 0.2(-0.2~0.5) 0.1(-0.2~0.4) Control High 0 0 0 Median 0.2(-0.3~0.6) 0.2(-0.2~0.6) 0.2(-0.2~0.5) Low 0.1(-0.4~0.6) 0.2(-0.3~0.6) 0.2(-0.2~0.6) Demand Low 0 0 0 Median 0.1(-0.4~0.6) -0.0(-0.5~0.4) -0.1(0.5~0.3 High -0.2(-0.7~0.4) -0.0(-0.5~0.4) -0.2(-0.5~0.2) Job support High 0 0 0 Low -0.1(-0.4~0.3) -0.0(-0.4~0.3) -0.0(-0.3~0.3) Depression No 0 0 0 Yes -0.1(-0.5~0.2) -0.2(-0.6~0.3) -0.1(-0.5~0.2) R2 .052 .272 .491 Adjusted R2 .030 .245 .466 *p< 0.05, ***p<0.001

adjustment for other variables

Model 2: further adjusted by age, gender, education, profession

Model 3: adjusted by variables in model 2 as well as smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose and total cholesterol