Fitting in organizational values

The mediating role of person-organization fit

between CEO charismatic leadership and

employee outcomes

Min-Ping Huang

Yuan Ze University, Chung-Li, Taiwan, and

Bor-Shiuan Cheng and Li-Fong Chou

National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

Purpose – The current leadership literature has paid little attention to understanding the intervening mechanism by which leaders influence followers. In order to partially bridge this gap, the article aims to present a value-fit charismatic leadership theory which focusses on the key intervening mechanism – person-organization values fit.

Design/methodology/approach – The model was tested empirically on 180 participants, including 51 managers and 129 employees from 37 large-scale companies in Taiwan.

Findings – Based on the block regression analysis, the results showed that CEO charismatic leadership has both direct and indirect effects on employees’ extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO, as well as organizational commitment, which are mediated by employees’ perceived person-organization values fit. The findings also provided evidence that the relationship between charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit is significant. Furthermore, the analysis also showed the significant effects of person-organization values fit on employee outcomes.

Originality/value – The study shows how CEO charismatic leadership can, through the mediating effect of person-organization values fit, have profound influence on employee outcomes.

Keywords Chief executives, Charisma, Leadership, Organizational culture, Regression analysis, Taiwan Paper type Research paper

Introduction

In the past 20 years, a number of researchers have begun to investigate the effects of charismatic leadership. Scholars often use different terms to describe this specific type of leadership, such as “charismatic” (House, 1977), “transformational” (Burns, 1978; Bass, 1985), “visionary” (Bennis and Nanus, 1985), or “value-based” (House et al., 1998) leadership. The terms “charismatic leadership” or “charisma” is better for describing the core essence of such leadership, which means that the leader has extraordinary power to influence followers and is able to obtain a special type of leader-follower relationship (Conger and Kanungo, 1998).

Charismatic leadership presents a different paradigm from other “more traditional” leadership styles such as transactional leadership. Based on a rational leader-member exchange relationship, transactional leaders emphasize urging subordinates to accomplish the set goals by providing appropriate incentives and usually take

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7720.htm

This article is based on research conducted under the sponsorship of the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 90-2416-H-155-017)

Fitting in

organizational

values

35

International Journal of Manpower Vol. 26 No. 1, 2005 pp. 35-49

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited

0143-7720 DOI 10.1108/01437720510587262

subordinates’ needs, preferences and values as inherent. On the other hand, charismatic leaders put emphasis on changing subordinates’ needs, values, self-concepts, and goals. A number of authors have noted that charismatic leaders usually demonstrate symbolic and meaningful behavior such as proclaiming the significance of a task, advocating ideological values and providing great vision, in order to provoke affective and cognitive consequences among subordinates, such as emotional attachment to and trust in leaders, motivation arousal, and enhanced self-efficacy (Shamir et al., 1993; Conger and Kanungo, 1998; House et al., 1998).

Briefly speaking, charismatic leadership is a leading process concerning value transformation. However, past research has had very few investigations on this underlying process (Yukl, 1999; Fiol et al., 1999). Besides, there is no theoretical model clearly explaining how a charismatic leader can transform a subordinate’s values into the leader’s values, and furthermore make them the shared values of the organization. In addition, although organizational culture researchers (e.g. Schein, 1992) have suggested there is an interactive relationship between an organization’s top leaders and organizational culture, the empirical data remains scant. Moreover, past research usually put more attention on outcome variables which are leader-related (e.g. trust in leader) or task-relevant (e.g. efficacy perception), but organization-relevant variables (e.g. organizational commitment) have been neglected in charismatic leadership studies (Shamir et al., 1998). Thus, we proposed a value-fit charismatic leadership model to fill the theoretical gaps described above, and which suggested that the CEO’s charisma can enhance person-organization values fit among followers and, in turn, lead to their outcome variables. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships between CEO charismatic leadership, person-organization values fit and employee outcomes. We also examined the mediating effect of person-organization values fit on the relationships between charismatic leadership and employee outcomes.

Theoretical background and hypotheses Charismatic leadership and follower outcomes

Under the “neocharismatic leadership paradigm” (House, 1977), the concept of charismatic leaders is already different from the ordinary type of “heroic figures” or “orators”. It is now considered a special type of leadership related to specific and observable behavior, by which such leaders can successfully stimulate internal change among followers. Thus, charismatic leaders are able to have an extraordinary influence on their followers and lead their transformation.

Hundreds of empirical studies have been conducted and in general have suggested that charismatic leadership has a positive effect on subordinates and organizations. In their review papers, Lowe et al. (1996) ran meta-analysis on 39 transformation leadership studies including the dimension of charisma, and found an average correlation between charisma and subordinates’ self-rated outcomes of 0.81, and a correlation between charisma and objectively rated outcomes of 0.35. The meta-analytic review by Fuller et al. (1996) also came to a similar conclusion. Moreover, the effect size of charismatic leadership has been found to be between 0.40 and 0.80 for individual outcome variables, and between 0.35 and 0.50 for organizational outcomes (Fiol et al., 1999).

IJM

26,1

Basically, these outcome variables for studying charismatic leadership can be grouped into three categories. The first category includes variables describing the relationship between subordinates and leaders, such as identification to leaders and supervisory satisfaction. The second includes variables describing subordinates’ perception on their own tasks and roles, such as extra job involvement and intrinsic motivation. The third includes variables describing the relationship between subordinates and their groups, such as organizational commitment and identification to the unit (for detailed reviews, see Lowe et al., 1996; Fuller et al., 1996). Furthermore, the first two categories of outcome variables have been discussed extensively in past charismatic leadership studies. For example, as Conger et al. (2000) mentioned, the effects of charismatic leadership are noticed on two fronts in most current literature, i.e. leader-focused variables and follower-focused variables. Among all the leader-focused variables, satisfaction with the leader is the one cited most. By emphasizing meaningful goals, showing exemplary behavior and providing empowerment approaches, a charismatic leader can significantly enhance followers’ satisfaction with the leader. Of the follower-focused variables, extra effort to work is one of the variables often explored. By bringing up the meaning of work and linking an organization’s mission and goals with ideological values, their followers are willing to make substantial self-sacrifices and extend effort above and beyond the call of duty. Therefore, charismatic leadership can usually produce highly satisfied and motivated followers, and as Shamir et al. (1993) noticed, the effect size of such influences is consistently higher than prior field study findings concerning other leadership behavior with correlations of 0.5 or better.

In contrast, the third category of variables (effects on subordinates’ relationship with their groups) has been relatively neglected in research on charismatic leadership (Shamir et al., 1998). Although most researchers have mentioned that by emphasizing collective identity and linking ideological values to this identity, charismatic leaders can significantly increase followers’ social identification and attachment to their group (e.g. Shamir et al., 1993; Conger et al., 2000), there is relatively little empirical data. One exception is the empirical study of Shamir et al. (1998), in which they found charismatic leadership is positively associated with subordinates’ identification with a unit, and attachment to the unit. In essence, social identification, attachment to the group, or even the desire to continue membership in it, all reflect a member’s commitment toward the organization. Therefore, we suggest that organizational commitment is an appropriate construct to capture this aspect. Stemming from current theory, we propose our first hypothesis as follows:

H1. CEO Charismatic leadership will have a positive effect on the following employee outcomes: Extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO, and organizational commitment.

The influence process of charismatic leadership

Compared to findings on charismatic leadership effectiveness, what we know on the influence process and underlying mechanism is very limited. What is the process by which charismatic leadership creates its influence? For this question, Shamir (1991) reorganized and compared relevant theories, and found four alternatives which might explain how charismatic leadership happens. They are the psychoanalytic explanation,

Fitting in

organizational

values

37

the sociological-symbolic explanation, the attribution-based explanation, and the self-concept-based explanation. Each alternative implies a different influence process. The psychoanalytic explanation suggests that charismatic leaders have extraordinary personality traits, which stimulate subordinates to imagine leaders as powerful figures, and this, in turn, can result in feelings of relief from responsibility and internal conflict for subordinates, and a strong identification with leaders. (Kets de Vries, 1988). The sociological-symbolic explanation suggests that charismatic leaders can fulfill followers’ needs for symbolic order and the meaning of life (Shils, 1965). The attribution-based explanation suggests that charismatic leadership is simply an attribution phenomenon (Meindl et al., 1985), or the combined attribution of the leader’s motivation, behavior, and the situation from subordinates (Conger and Kanungo, 1987), which can help followers to clarify ambiguous situations. The self-concept-based explanation suggests that charismatic leaders can stimulate subordinates’ intrinsic motivation and enhance their self-concepts, self-esteem, and self-worth (Shamir, 1991; Shamir et al., 1993).

Among these different explanations, the psychoanalytic explanation does not pay attention to the mediating mechanism of charismatic leadership. Both the sociological-symbolic explanation and the attribution-based explanation suggest the subordinates’ attribution of leaders is the mediating mechanism of charismatic leadership. The self-concept-based explanation somehow suggests that followers’ self-concept perception is the mediating mechanism (Shamir, 1991). However, each of the explanations regarding the influence process of charismatic leadership seems to be too farfetched and ambiguous or too difficult to be tested empirically. Thus most of them remain at the stage of conceptural discussion. The only exception is the self-concept-based explanation. Based on the model of Shamir et al. (1993), the theory suggests that a charismatic leader can increase the intrinsic valence of efforts and goals by linking a follower’s self-concept to the leader, to the mission, and to the group, such that the follower’s behavior for the sake of the leader and the group becomes self-expressive. In other words, the self-concept-based theory sees charismatic leadership as a motivational process. Recent findings provide some support for this assertion. For example, some studies have found that a positive relationship exists among charismatic leadership, followers’ identification, and their willingness to contribute to group objectives (Shamir et al., 1998). Moreover, Kark et al. (2003) advanced this model to test the indirect effect of transformational leadership, mediated through follower’s personal and social identification on their dependency and empowerment.

However, despite these encouraging results, several important questions remain unclear, especially how such leaders transform followers’ personal values into collective or shared values with which each follower can identify over time. In order to answer such questions, we will see charismatic leadership as a socialization process and draw from a person-organization values fit perspective to explain the influence process of charismatic leadership.

An alternative mediating linkage between charismatic leadership and follower outcomes Person-organization values fit. “Values” are usually treated as internalized normative beliefs that represent individual’s desirable states, objects, or goals. After these beliefs are established, they are applied as normative standards to judge and to choose among

IJM

26,1

alternative modes of behavior (Schwartz, 1992). This definition highlights that values are internal to people and can be viewed as relatively enduring criteria used in generating and evaluating people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Therefore, “organizational values” can serve as general constraints on the generation of work-related goals in a specific organizational context. They are applied as normative standards and guidance for members to behave compatibly with organizational needs (O’Reilly et al., 1991).

“Person-organization values fit” is defined as the compatibility in values, or value congruence of individuals with the organizations in which they work (O’Reilly et al., 1991). Given the regulatory characteristics of values, when members share a particular set of values with their organizations, they are expected to be free from direct control, while at the same time to exhibit behavior that is compatible with group needs (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1996). In addition, from the preponderance of empirical evidence, researchers are convinced that a higher values fit between individuals and their organizations is associated with more positive subjective experience for the person and better performance for the organization (for detailed review, see Kristof, 1996). The theoretical foundations for these effects are typically ascribed to the well-documented effects of similarity-attraction and social identity processes (Byrne, 1971).

There are different approaches that organizational managers can use to improve members’ person-organization values fit, such as recruiting and socialization, and leadership is definitely one of the most important ways. Indeed, by highlighting relevant behavior to organizational values or influencing socialization processes, leaders can play a critical role in fulfilling such a function (Lord and Brown, 2001). Therefore, we will address the special role of charismatic leadership in influencing follower’s person-organization values fit.

Charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit. Previous research has tried to depict the domain of charismatic leadership behavior. However, only a few researchers have clearly defined the behavioral dimensions of charismatic leadership and developed questionnaires to measure charismatic leadership from the behavior perspective (Bass and Avolio, 1990; Conger and Kanungo, 1987; Conger and Kanungo, 1998; House et al., 1998; Shamir et al., 1998). Although there are differences in their descriptions, some dimensions are consistently considered important, such as providing an innovative vision and modeling exemplary behavior. After reconceptualizing these behavioral dimensions, we argue that charismatic leadership behavior basically can be categorized into two groups: one includes the behavior relating to subordinate shaping, the other includes the behavior relating to culture shaping.

“Subordinate shaping” means that the charismatic leader usually interacts with subordinates directly by providing support to subordinates (e.g. Shamir et al., 1998; Conger and Kanungo, 1998), building confidence to them (e.g. House et al., 1998; Conger and Kanungo, 1998), and displaying exemplary behavior (e.g. House et al., 1998; Shamir et al., 1998). By showing this type of behavior, the charismatic leader can encourage followers to identify with the leader (individual identification, Kark et al., 2003), and internalize the leader’s values (value internalization, Shamir et al., 1993). Thus, subordinates not only show great respect for and trust of the charismatic leader,

Fitting in

organizational

values

39

but also are willing to make a commitment to the leader and the task proclaimed by the leader.

On the other hand, “culture shaping” means the charismatic leader can transfer his/her ideological values to organizational members by presenting an ideological vision or values (e.g. House et al., 1998; Conger and Kanungo, 1998), and emphasizing collective identity (e.g. Shamir et al., 1998). By showing this type of behavior, the charismatic leader can help followers internalize organizational values (value internalization, Shamir et al., 1993) and identify themselves with the whole group (social identification, Kark et al., 2003). Thus, subordinates typically have more positive affect toward their own group and show a higher willingness to commit to collective benefits.

According to Schein (1992), the most important function of top leaders is to implant their own values into the organization through culture embedding mechanisms, and thus further establish a strong organizational culture. But, how is a leader able to communicate his/her major assumptions and values in a vivid and clear manner? One of the main elements is though charisma (Schein, 1992, p. 229). Other researchers also suggested that since a charismatic/transformational leader is usually expected to present group values and identity in his/her personal behavior, his/her verbal and nonverbal behavior actively fosters shared values and norms. Thus, such a leader usually contributes to create a distinctive and strong organizational culture (Bass, 1985, p. 25; Shamir et al., 1998). Therefore, we can expect charismatic CEOs to have greater power to bring their own values into organizational values than non-charismatic CEOs.

As a whole, we suggest that through subordinates-shaping behavior, the charismatic CEO can promote subordinates’ identification with the leader and influence subordinates to internalize the values proclaimed by the leader. Moreover, through culture-shaping behavior, the charismatic CEO can help organizational members to go through socialization process effectively and further to internalize organizational values. Given the special role of a charismatic CEO as a “provider” and “definer” of organizational culture, the organizational culture should be the reflection of the charismatic CEO’s personal values. Therefore, we argue that organizational employees should have higher values fit with their organizational culture under CEO charismatic leadership. Thus, we propose:

H2. CEO Charismatic leadership will have a positive effect on employees’ person-organization values fit.

Person-organization values fit and employee outcomes

As mentioned above, current theory has suggested that person-organization values fit is a key factor with great influence on employee outcomes. In the aggregate, empirical studies provide convincing evidence that person-organization values fit is an important determinant of long-term consequences for employees (e.g. work attitude, intention to quit, prosocial behavior, and work performance), organizational entry (e.g. individual job search), and socialization (see Kristof, 1996, for review). Especially, person-organization values fit has been well supported in its influences on organizational commitment (O’Reilly et al., 1991; Cheng, 1993) as well as job satisfaction (Chatman, 1991; Cheng, 1993). Some researchers have noticed that

IJM

26,1

satisfaction with the leader is an important component of overall job satisfaction (Smith et al., 1969). Furthermore, the charismatic leader is usually expected to represent the whole group. Thus, we expect that a positive relationship exists between employees’ person-organization values fit and satisfaction with the charismatic CEO. In addition, Posner (1992) found value congruence has a positive effect on motivation, so we propose employees’ person-organization values fit will positively influence their extra effort to work. We obtained the third hypothesis based on the above discussions: H3. Employees’ person-organization values fit will have a positive effect on the following employee outcomes: Extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO, and organizational commitment.

The mediating effect of person-organization values fit

Combining all of the above, we propose a charismatic leadership model based on person-organization values fit. This model shows that charismatic leadership can have a positive influence on employee outcomes mediated by employees’ person-organization values fit. By introducing the mechanism of person-organization values fit, we argue that charismatic leadership acts as a socialization process. This can partially explain why the duration and scope of a charismatic leader’s influence is usually much greater than those leaders who only address a narrower task focus and pragmatic values. Additionally, this can also explain why charismatic leaders can have positive effects not only on employees’ attitude toward the leader himself and the task, but also on their attitude toward the whole organization. According to our model, we propose:

H4. Employees’ person-organization values fit will have a mediating effect on the relationship between CEO charismatic leadership and the following employee outcomes: Extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO, and organizational commitment.

Method

Participant and data collection

Participants were from 37 large-scale companies in Taiwan’s top 500 enterprises, which are broadly selected from 12 different industries, including, automobile manufacturing, food processing, petrochemistry, electronic and computer components, real estate, investment and banking, etc. All together, 180 subjects participated in the study, consisting of 51 high-level managers (i.e. one to two managers per company) and 129 staff members (i.e. four to five employees per company). For staff participants, 69 percent were male, and the average age was 38 years old. The average tenure was eight years, and 67 percent had graduated from vocational school and above. Data were collected by administering questionnaires to participants. To minimize the risk of correlation inflation due to common source bias, we obtained the data of CEO charismatic leadership from manager participants, and assessed organizational culture values, personal values, extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO, organizational commitment, and demographic variables from staff participants.

Fitting in

organizational

values

41

Measures

Charismatic leadership. CEO charismatic leadership was rated by manager participants with the eighteen items adapted from the charisma scale of the old version of the MLQ (Bass, 1985) which is the most widely used measure of charisma (Shamir et al., 1998). The coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.97.

Person-organization values fit. The measurement of personal and organizational values was based on the organizational culture inventory (Cooke and Lafferty, 1986). Some 36 items were adopted from the OCI according to the original factor structure. Following the procedure suggested by Cooke and Rousseau (1988), the staff participants were asked to rate each item twice, first referring to agreement that “your company thinks it’s important” (i.e. organizational values) and then referring to agreement that “you think it’s important” (i.e. personal values). The coefficient alpha for the organizational values scale was 0.88, and the personal value scale was 0.87. The person-organization values fit score was calculated by averaging the absolute deviations between organizational values and personal values of each item (Edwards, 1993). Accordingly, a lower score meant a higher values fit.

Extra effort to work. Three items were taken from the extra effort scale of the original MLQ (Bass, 1985) to measure extra effort to work. Sample items were “makes me do more than I expected I could do” and “makes me feel ready to sacrifice my personal comfort for the goal of the company”. The coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.90.

Satisfaction with the CEO. Staff participants rated satisfaction with the CEO in two areas: leadership style and overall impression. This is two-item rating scale taken from Bass (1985). The coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.90.

Organizational commitment. Organizational commitment was measured with 15 items of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Porter et al., 1985) by staff participants. The coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.93.

All scales above were six-point Likert-like scales (1 ¼ strongly disagree and 6 ¼ strongly agree). We used the six-point Likert-like scale because Chinese people tend to choose the mid-point of the scale regardless of their true feelings or attitudes (Chiu and Yang, 1987). Therefore, by not including a mid-point, we hoped to prevent this response bias.

Control variables. Gender, age, education, and organizational tenure were included in the study as control variables. These variables have been found to be related to employee outcomes (Lee and Wilbur, 1985). Gender was coded as two categories (1 ¼ male and 0 ¼ female). Age, ranging from under 30 years old to over 60-years-old, was classified into five categories (1 ¼ under 30, 2 ¼ 30 to under 40, etc.). Education was assigned into five categories (1 ¼ middle school diploma or less, 2 ¼ senior high school diploma, 3 ¼ vocational school degree, 4 ¼ Bachelor’s degree, and 5 ¼ Master’s degree or above). Tenure, ranging from less than three years to more than 18 years, was coded into seven categories (1 ¼ under three years, 2 ¼ three to under six years, etc.).

Analysis

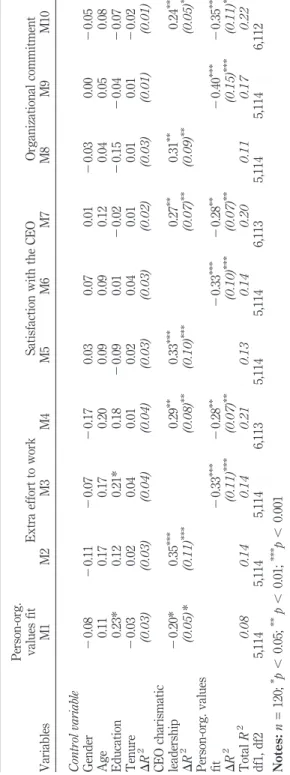

Using block regression, we examined the hypothesized relationships between CEO charismatic leadership, person-organization values fit, and employee outcomes in terms of extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO and organizational

IJM

26,1

commitment, with the employee’s demographics as control variables. There were ten regression models used in the block regression analysis for testing the hypotheses. In the first, second, fifth and eighth regression models, we entered the demographic variables and charismatic leadership to determine the effects of charismatic leadership on person-organization values fit, and three employee outcomes. In the third, sixth and ninth regression models, we entered the demographic variables and person-organization values fit to demonstrate the effect of person-organization values fit on employee outcomes. In the fourth, seventh and tenth regression models, we entered the demographic variables, charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit to determine the unique effects of charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit on employee outcomes.

Results

Table I provides the means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and zero-order correlations for all study variables. At the zero-correlation level, charismatic leadership was significantly related to all three employee outcome variables (r ¼ 0.29, p , 0.01 to r ¼ 0.34, p , 0.001) and person-organization values fit (r ¼ – 0.19, p , 0.05). Person-organization values fit had a significant negative relationship with all three employee outcomes (r ¼ – 0.29, p , 0.001 to r ¼ – 0.32, p , 0.001).

Table II shows the block regression results for CEO charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit on employee outcomes. H1 proposed that CEO charismatic leadership has a positive relationship on employee outcomes. After controlling the demographic variables, charismatic leadership still has significant unique effects on all three employee outcomes (for extra effort to work, DR2¼ 0.11, p , 0.01;b¼ 0.35, p , 0.001; for satisfaction with the CEO, DR2¼ 0.10, p , 0.001;

b¼ 0.33, p , 0.001; for organizational commitment, DR2¼ 0.09, p , 0.01;b¼ 0.31, p , 0.01). Thus, the first hypothesis was supported.

H2 proposed that CEO charismatic leadership has a direct positive relationship with person-organization values fit. After controlling the demographic variables, charismatic leadership still has a significant unique effect on person-organization values fit (DR2¼ 0.05, p , 0.05; b¼ -0.20, p , 0.05). Thus, the second hypothesis was supported.

H3 proposed that person-organization values fit has a direct negative effect on employee outcomes. After controlling the demographic variables, person-organization values fit still has significant and unique effects on all three employee outcomes (for extra effort to work, DR2¼ 0.11, p , 0.001;b¼ –0.33, p , 0.001; for satisfaction with the CEO, DR2¼ 0.10, p , 0.001;b¼ – 0.33, p , 0.001; for organizational commitment, DR2 ¼ 0.15, p , 0.001; b¼ – 0.40, p , 0.001). Thus, the third hypothesis was supported.

H4 proposed that person-organization values fit has a mediating effect on the relationship between CEO charismatic leadership and employee outcomes. Following the procedure suggested by James and Brett (1984), we tested our mediating hypothesis. Table II shows that the unique effects of charismatic leadership on employee outcomes are significant (see M2, M5 and M8), the unique effect of charismatic leadership on person-organization values fit is significant (see M1), and the unique effects of person-organization values fit on employee outcomes are also significant (see M3, M6 and M9). Putting all the variables into the block regression

Fitting in

organizational

values

43

Variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Control variables a 1.Gender 0.61 0.49 2.Age 1.81 0.79 0.31 *** 3.Education 3.64 0.87 0.31 *** -0.26 ** 4.Tenure 2.62 1.96 0.02 0.75 *** -0.43 *** 5. CEO charismatic leadership 4.72 0.74 0.24 ** 0.01 0.13 0.00 (0.97) b 6. Person-org. values fit 0.76 0.65 -0.01 -0.02 0.15 -0.07 -0.19* 7. Extra effort to work 3.95 1.02 0.04 0.11 0.06 0.10 0.34 *** -0.31 *** (0.90) 8. Satisfaction with the CEO 4.18 1.09 0.08 0.15 -0.08 0.16 0.33 *** -0.32 *** 0.66 *** (0.90) 9. Organizational commitment 3.98 0.85 -0.04 0.04 -0.14 0.08 0.29 ** -0.29 *** 0.45 *** 0.59 *** (0.86) No tes: n = 129 ; * p , 0.05; ** p , 0. 01; ** * ;p , 0.0 01; a Control v ariables w er e coded as follows: G ender :male = 1, female = 0; Age: under 30 = 1, 30 to under 40 =2 ,4 0t ou n d er 50 = 3, 50t ou n d er 60 = 4, ov er6 0 = 5; E d u ca ti on :m id d le sc h oo l or less = 1, senior h igh school = 2, v oc ationa l school = 3, B achelor = 4, Mast er or abo v e = 5; Ten u re: und er 3 = 1, 3 to u nder 6 = 2, 6 to und er 9 = 3, 9 to u nder 12 = 4, 12 to un der 15 = 5, 15 to un der 18 = 6, ov er 18 = 7; bCr on bach ’s a Table I. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of variables

IJM

26,1

44

Person-org. values fit Extra effort to work Satisfaction with the CEO Organizational commitment Variables M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 M8 M9 M10 Control variable Gender 2 0.08 2 0.11 2 0.07 2 0.17 0.03 0.07 0.01 2 0.03 0.00 2 0.05 Age 0.11 0.17 0.17 0.20 0.09 0.09 0.12 0.04 0.05 0.08 Education 0.23* 0.12 0.21* 0.18 2 0.09 0.01 2 0.02 2 0.15 2 0.04 2 0.07 Tenure 2 0.03 0.02 0.04 0.01 0.02 0.04 0.01 0.01 0.01 2 0.02 D R 2 (0.03) (0.03) (0.04) (0.04) (0.03) (0.03) (0.02) (0.03) (0.01) (0.01) CEO charismatic leadership 2 0.20* 0.35 *** 0.29 ** 0.33 *** 0.27 ** 0.31 ** 0.24 ** D R 2 (0.05) * (0.11) *** (0.08) ** (0.10) *** (0.07) ** (0.09) ** (0.05) ** Person-org. values fit 2 0.33 *** 2 0.28 ** 2 0.33 *** 2 0.28 ** 2 0.40 *** 2 0.35 *** D R 2 (0.11) *** (0.07) ** (0.10) *** (0.07) ** (0.15) *** (0.11) ** Total R 2 0.08 0.14 0.14 0.21 0.13 0.14 0.20 0.11 0.17 0.22 df1, df2 5,114 5,114 5,114 6,113 5,114 5,114 6,113 5,114 5,114 6,112 Notes: n = 120; * p , 0.05; ** p , 0.01; *** p , 0.001 Table II. The results of block regression analysis

Fitting in

organizational

values

45

model, the unique effects of charismatic leadership on employee outcomes reduce significantly (for extra effort to work, DR2reduces from 0.11 to 0.08,breduces from 0.35 to 0.29; for satisfaction with the CEO, DR2reduces from 0.10 to 0.07,breduces from 0.33 to 0.27; for organizational commitment, DR2 reduces from 0.09 to 0.05,

b reduces from 0.31 to 0.24). In addition, the unique effects of person-organization values fit are still significant (see M4, M7 and M10, where DR2from 0.07, p , 0.01 to

0.11, p , 0.001;bfrom 2 0.28, p , 0.01 to 2 0.35, p , 0.001). All together, these results reveal that the relationships between CEO charismatic leadership and all three employee outcomes are partially mediated by person-organization values fit since charismatic leadership still has significant direct effects on employee outcomes (DR2 from 0.05, p , 0.01 to 0.08, p , 0.01;bfrom 0.24, p , 0.01 to 0.29, p , 0.01). Thus, the fourth hypothesis was partially supported.

Discussion

This study proposed a value-fit model of charismatic leadership in organizations, which shows how CEO charismatic leadership can influence employee outcomes such as extra effort to work, satisfaction with the CEO and organizational commitment through person-organization values fit.

According to our results, we demonstrated that charismatic leadership has significant effects on employee outcomes. Our findings also provided evidence that the relationship between charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit is significant. Furthermore, our analysis also showed the significant effects of person-organization values fit on employee outcomes.

Previous studies have consistently shown that charismatic leadership has significant effects on follower outcomes (Fuller et al., 1996; Lowe et al., 1996). Our findings also showed the same pattern of relationship between charismatic leadership and follower outcomes. Consistent with previous research about person-organization fit (Cheng, 1993; O’Reilly et al., 1991), our results showed that person-organization values fit could predict extra effort to work, satisfaction with the leader and organizational commitment. Additionally, our findings about the positive relationship between charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit also confirm results from previous studies about the roles of top managers for shaping and creating organizational culture (Schein, 1992).

However, although it was found that the mediating effect of person-organization values fit on the relationship between CEO charismatic leadership and employee outcomes is significant, CEO charismatic leadership still has some direct effects on outcome variables. This issue needs to be further clarified or even reconsidered. First, the direct effects of charismatic leadership may imply the influence process of charismatic leadership on follower outcomes could be more complicated than we originally proposed. We suggest that the relationship between charismatic leadership and person-organization values fit may also exist with some other mediators. For example, there may be dual routes, one through organization-leader values fit, and the other through follower-leader values fit. If so, each route may have its unique effect on outcome variables (Cheng, 1993; Meglino et al., 1989).

Second, the various effects of each route may involve the issue of level of analysis. Waldman and Yammarino (1999) have indicated that the level of measures and statistical analysis must match the level of theoretical constructs. Basically, our study

IJM

26,1

considers culture-shaping behavior of CEO charismatic leadership as an organizational level fact, so such behavior should have greater effects on organization-relevant outcomes. On the other hand, subordinate-shaping behavior is considered as a dyadic or group-level phenomenon, so it should have relatively higher influence on individual-relevant or group-relevant outcomes. In short, we should further clarify the issue of level of analysis for each influence route in order to improve our model’s validity.

Third, the behavioral dimensions of charismatic leadership also need to be clarified. Although researchers have some kind of agreement on the behavior domain of charismatic leadership, the precise behavioral dimensions still remain inconsistent (Conger and Kanungo, 1998; Bass and Avolio, 1990; Shamir et al., 1998). Therefore, in order to accumulate more empirical evidence for this current model, it is necessary to redevelop an appropriate measurement for charismatic leadership behavior based on our culture-shaping and subordinate-shaping constructs.

There are limitations in our research that should be mentioned. First, this study only used extra effort at work, satisfaction with the CEO and organizational commitment as the outcome variables, which limit the possibility of comparing our results with different outcome variables. Second, since this research only collected cross-sectional data, it is not appropriate to infer strong causal effect between variables. Therefore, collecting longitudinal data for time-lag analysis may be a good approach for future research. Third, even though the hierarchical linear model (HLM) is more suitable for analyzing data from different levels, we did not use this method since we only got small samples from each company.

Although there are some limitations, our results are still reliable and can provide several important theoretical implications. First, as many researchers have indicated, investigation on the influence processes of charismatic leadership can assist the development of charismatic leadership theories (Yukl, 1999). Our study provides a model with empirical support to show that charismatic leadership can have a profound effect on employee outcomes through improving person-organization values fit. Second, this study offers a bridge to link the strategic leadership theory and organizational culture theory. Our empirical findings show that organizational culture and values fit play an important role in the leading process. Third, for the controversy concerning whether it is possible for top-level leaders to have substantial effects on the overall performance of the organization (Waldman and Yammarino, 1999), this research provides some insight about the ways in which charismatic CEOs might have substantial effects on organizational effectiveness.

References

Bass, B.M. (1985), Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, Free Press, New York, NY. Bass, B.M. and Avolio, B.J. (1990), Manual: The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire,

Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Bennis, W. and Nanus, B. (1985), Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge, Harper and Row, New York, NY.

Burns, J.M. (1978), Leadership, Harper & Row, New York, NY.

Byrne, D. (1971), The Attraction Paradigm, Academic Press, New York, NY.

Fitting in

organizational

values

47

Chatman, J. (1991), “Matching people and organization: selection and socialization in public accounting firms”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 459-84.

Cheng, B.S. (1993), “The effects of organizational value on organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance: a comparison of different weighting model and discrepancy model”, Chinese Journal of Psychology, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 43-58, (In Chinese).

Chiu, C. and Yang, C.F. (1987), “Chinese subjects’ dilemmas: humility and cognitive laziness as problems in using rating scales”, Bulletin to the Hong Kong Psychology Society, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50.

Conger, J.A. and Kanungo, R. (1987), “Toward a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 637-47. Conger, J.A. and Kanungo, R.N. (1998), Charismatic Leadership in Organizations, Sage, Newbury

Park, CA.

Conger, J.A., Kanungo, R.N. and Menon, S.T. (2000), “Charismatic leadership and follower effects”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 747-67.

Cooke, R.A. and Lafferty, J.C. (1986), Level 5: Organizational Culture Inventory – Form 3, Human Synergistics, Plymouth, MA.

Cooke, R.A. and Rousseau, D. (1988), “Behavioral norms and expectations: a quantitative approach to the assessment of organizational culture”, Group and Organization Studies, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 245-73.

Edwards, J.R. (1993), “Problems with the use of profile similarity indices in the study of congruence in organizational research”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 46 No. 3, pp. 641-65. Fiol, C.M., Harris, D. and House, R. (1999), “Charismatic leadership: strategies for effecting social

change”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 449-82.

Fuller, J.B., Patterson, C.E.P., Hester, K. and Stringer, D.Y. (1996), “A quantitative review of research on charismatic leadership”, Psychological Reports, Vol. 78 No. 1, pp. 271-87. House, R.J. (1977), “A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership”, in Hunt, K.G. and Larson, L.L.

(Eds), Leadership: The Cutting Edge, 189-207, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL.

House, R.J., Delbecq, A. and Taris, T.W. (1998), “Values-based leadership: an integrated theory and an empirical test”, Technical Report for Center for Leadership and Change Management, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

James, L.R. and Brett, J.M. (1984), “Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 69 No. 3, pp. 307-21.

Kark, R., Shamir, B. and Chen, G. (2003), “The two faces of transformational leadership: empowerment and dependency”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 1, pp. 246-55. Kets de Vries, M.F. (1988), “Origins of charisma: ties that bind the leader and the led”, in Conger, J.A. and Kanungo, R.N. (Eds), Charismatic Leadership, Jossey-Bass, San-Francisco, CA, pp. 237-52.

Kristof, A. (1996), “Person-organization fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 49 No. 2, pp. 1-49.

Lee, R. and Wilbur, E.R. (1985), “Age, education, job tenure, salary, job characteristics, and job satisfaction: a multivariate analysis”, Human Relations, Vol. 38 No. 2, pp. 781-91. Lord, R.G. and Brown, D.J. (2001), “Leadership, values and subordinate self-concepts”,

Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 1-21.

IJM

26,1

Lowe, K.B., Kroeck, K.G. and Sivasubramaniam, N. (1996), “Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic review”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 385-425.

Meglino, B.M., Ravlin, E.C. and Adkins, C.L. (1989), “A work values approach to corporate culture: a field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 74 No. 3, pp. 424-32.

Meindl, J.R., Ehrlich, S.D. and Dukerich, J.M. (1985), “The romance of leadership”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 78-102.

O’Reilly, C. and Chatman, J. (1996), “Culture as social cotnrol: corporations, cults and commitment”, in Staw, B.M. and Cummings, L.L. (Eds), Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 18, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.

O’Reilly, C.A., Chatman, J.A. and Caldwell, D. (1991), “People and organizational culture: a profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 34 No. 3, pp. 487-516.

Porter, L.W., Steers, R.M., Mowday, R.T. and Boulian, P.V. (1985), “Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 59 No. 3, pp. 603-9.

Posner, B.Z. (1992), “Person-organization values congruence: no support for individual differences as a moderating influence”, Human Relations, Vol. 45 No. 2, pp. 351-61. Schein, E.H. (1992), Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco,

CA.

Schwartz, S.H. (1992), “Universal in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries”, in Zanna, M. (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Academic Press, New York, NY, pp. 1-65.

Shamir, B. (1991), “The charismatic relationship: alternative explanations and predictions”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 81-104.

Shamir, B., House, R.J. and Arthur, M.B. (1993), “The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: a self-concept based theory”, Organization Science, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 577-94. Shamir, B., Zakay, E. and Popper, M. (1998), “Correlates of charismatic leader behavior in

military units: subordinates’ attitudes, unit characteristics, and superiors’ appraisals performance”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 387-409.

Shils, E.A. (1965), “Charisma, order and status”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 30 No. 2, pp. 199-213.

Smith, C.G., Kendall, L.M. and Hulin, C.L. (1969), The Measurement of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement, Rand McNally, Chicago, IL.

Waldman, D.A. and Yammarino, F.J. (1999), “CEO charismatic leadership: levels-of-management and levels-of-analysis effects”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 266-85. Yukl, G. (1999), “An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic

leadership theories”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 285-305.