Amateur Music Clubs and State

Intervention: The Case of Nanguan

Music in Postwar Taiwan

Wang Ying-fen Associate Professor National Taiwan University Graduate Institute of Musicology

Abstract: Amateur music clubs had been an integral part of the communal life in traditional Taiwan society. They constituted the main vehicle through which traditional art forms had been transmitted from generation to genera-tion. In post-war Taiwan, however, amateur music clubs experienced serious decline. This was partly due to the Nationalist government’s cultural policy to promote Western and Chinese art forms and downgrade local Taiwanese culture, and partly due to the rapid westernization, modernization, industrial-ization, and urbanization that Taiwan society had undergone. In the 1970s, with the change of the political climate both internationally and domestical-ly, the Nationalist government began to pay attention to local culture and to implement a series of projects to promote traditional arts. Among the art forms promoted, nanguan music stood out as one of the best supported due to its high social status, neutral political position, and academic value as recognized by foreign and domestic scholars. State intervention in nanguan started in 1980 and gradually increased its intensity until it reached its peak level in the second half of the 1990s. It has brought many resources to nan-guan clubs, but it has also contributed to the deterioration of the nannan-guan community both in its musical quality and its members' integrity as amateur musicians.

Based on my personal involvement in nanguan, I aim to document in this paper the state intervention in nanguan in the past two decades and to examine its impact on nanguan. I argue that the past two decades of state intervention in nanguan has fallen short of its goal to preserve and transmit nanguan mainly because its modes of intervention did not take into consid-eration the nature of nanguan as a pastime for self-cultivation among ama-teur musicians. I will also argue that such a failure can be further traced back to the lack of understanding about local traditional culture in Taiwan society as a result of the Nationalist government’s policy to uphold Western and national art forms while downgrading local ones.

Key words: cultural policy, state intervention, postwar Taiwan, nanguan, amateur music clubs.

I. Introduction

Twenty years ago, in the summer of 1983, I went to Longshan Temple in Lukang , a historic town in Changhua County in mid-Taiwan and well known for its nanguan (literal-ly “southern pipes”) tradition. I entered the wide-open space of the quiet, empty temple ground, and soon my attention was captured by the sound of nanguan pipa (four-stringed plucked lute). I fol-lowed it to another part of the temple ground. Then I saw two very old men, sitting in chairs, with their eyes half closed. One was play-ing a nanguan pipa and the other playplay-ing an erxian , the nan-guan two-stringed fiddle. After the piece ended, the two remained silent. Soon, the pipa player started playing again, and the erxian player joined in naturally without asking which piece it was. The two continued on leisurely as if the music would never end, and life was just as simple and quiet as the music. Later I learned that the two old men were respectively in their 80s and 90s and belonged to Juying she , the nanguan music group that had been part of the temple for almost a century. This was one of my first encounters with nanguan music clubs, and the leisurely, quiet atmosphere of the whole scene made a lasting impression on me.

Two years ago, I went to the temple again. The sound of nan-guanwas still there, but, instead of the quiet music played leisurely by the two old men, this time it was a group of young students singing nanguan together and led by two nanguan teachers. The singing was a bit chaotic and out of tune, but the teachers did not stop them, and the singing continued on. Without asking, I knew that this was another nanguan training course sponsored by the state.

These two snapshots of nanguan activities in the same temple almost twenty year apart reflected more or less how nanguan in Taiwan has been transformed from a leisurely pastime of amateur music clubs to a cultural heritage promoted by the state through widespread training courses and other means of intervention. Such state intervention in nanguan started around 1980 and gradually increased in intensity until its recent peak level during the second

half of the 1990s. It has brought many resources to nanguan clubs, but it has also contributed to the deterioration of the nanguan com-munity both in terms of its musical quality and its members’ pride and identity as amateur musicians.

Based on my personal involvement in nanguan as a researcher since 1983 and in state-funded projects on nanguan since 1993,1 I aim to document in this paper the state intervention in nanguan in the past two decades and to examine its impact on nanguan. I will argue that the past two decades of state intervention in nanguan has failed to help preserve and transmit nanguan mainly because its modes of intervention did not take into consideration the nature of nanguan music as a self-cultivating pastime of amateur musicians. I will also argue that such a failure can be further traced back to the lack of understanding about local traditional culture on the part of cultural officials and scholars as a result of the Nationalist (also known as KMT) government’s policy to uphold Western and national art forms while downgrading local traditional arts.2

Even though scholars have made sporadic observations about the negative effects of state intervention on Taiwanese traditional arts,3 there has been little systematic research on the subject either 1. I was the producer of a state-commissioned nanguan recording project in 1993-94, the organizer of a nanguan conference as part of the first state-run nan-guan art festival in 1994, and have been a reviewing committee member for the National Center for Traditional Arts since since around 1998.

2. In this article, “national art forms” refer to the various genres that were brought to Taiwan by mainland Chinese after 1945 and subsequently promoted by the Nationalist government as “national culture,” while “local traditional arts” refer to the traditional art forms of the aborigines (the original inhabitants of the island) and those of the southern Fujianese and Hakka people who emigrated to Taiwan in large numbers beginning in the 17thcentury.

3. So far Qiu Kunliang is probably the only scholar that has written most fre-quently about how state intervention has damaged traditional arts since the early 1980’s. Most of these writings, however, were short essays published in newspa-pers and popular magazines and republished in his collections of essays (see Qiu 1980, 1984, 1992, 1997a, 1997b, 1999, 2003). Lü Chuikuan in his recent review of the state of traditional music in Taiwan, a government-commissioned project, pointed out the negative influence brought by state intervention in nan-guan and other traditional music (see Lü 2002:passim). Lin Gufang wrote

by researchers in cultural policy or those in traditional arts in Taiwan. Although Su Kuei-chi’s dissertation (2002) provides us with a comprehensive overview of the Nationalist government’s arts poli-cy in postwar Taiwan, it mainly focused on how the polipoli-cy influ-enced Peking Opera and gezaixi (native opera sung in Taiwanese) and does not deal with its effect on other Taiwanese operatic or musical genres. To fill this gap, I have relied on primary and secondary sources to sort out the state projects on traditional arts in general and on nanguan in particular, to examine their fund-ing and operation, and to analyze the problems incurred by these projects. The primary sources consulted include governmental publi-cations, unpublished project reports, concert programs, writings by cultural officials, interviews with cultural officials and staff members, interviews with musicians, and my own involvement and observa-tion. In addition, I have consulted previous research on state cultural policy in Taiwan (such as Hsiau 1991, 2000; Li [1988] 1992; Su 1992; Winckler 1994; Su 1998; Su 2001; Su 2002) to put state intervention in nanguan in a larger historical and political context.

In the following account, I will first give an overview of the nature of amateur music clubs and outline the history of the state cultural policy under the Nationalist government’s rule in postwar Taiwan. Then I will propose the reasons for nanguan’s favourable position in gaining state patronage. Next, I will divide the past two decades of state intervention in nanguan into four stages and dis-cuss the modes of intervention in each of them. Finally, I will

sum-about the problem of state subsidies and the role of scholars as cultural brokers (Lin [ 1991]1995). Chou Chiener discussed how cultural policy and scholarly intervention changed the identity of nanguan music in Taiwan (Chou in press). Wu Huohuang , a nanguan musician and an amateur researcher, observed how state-run nanguan activities lost the spontaneous interaction among nanguan musicians in their traditional activities (Wu 2000). Similar opinions were expressed by Fan Yangkun concerning state intervention in beiguan (literally “northern pipes”) music (Fan 2002:198). In addition, Belinda Chang analysed how cultural policy and political ideology influenced the development of gezaixi in Taiwan (Chang 1997). Nancy Guy examined how the Nationalist government upheld Peking Opera and disparaged local Taiwanese culture and arts (Guy 1999).

marize these four stages of state intervention, examine how it has affected the nanguan community, and discuss why it has fallen short of its goal.

II. Amateur Music Clubs in Taiwan

4Recent surveys on artistic resources and on amateur music clubs in various counties in Taiwan show that amateur music clubs had been widespread in villages as well as in urban communities all over the island. Such amateur music clubs, known as quguan (liter-ally “song club”) or wenguan (“civil club”), existed in almost every village inhabited by the southern Fujianese and Hakka people who emigrated from southeastern coastal China to Taiwan beginning in the 17th century. In larger urban centers with bigger populations and livelier economies, the number of amateur music clubs tended to number in the dozens. While clubs in the villages usually consist-ed of members of the same village, clubs in urban centers could consist of members of a family, a locale, or a profession. These clubs, together with the local temples and the amateur martial arts clubs known as wuguan (“martial club”), functioned as com-munity centers and formed an integral part of the life of the Han immigrants on the island.

These amateur music clubs were voluntary associations usually organized and supported by local elites and participated in by vil-lagers and urban community members to study traditional arts and culture, to relax and cultivate oneself, to build human relationships, to perform at the rites of passages of fellow club members, and to contribute to temple festivals either as performers or as supporters. In the case of the amateur martial arts clubs, they also bore the responsibility of defending their villages and communities in times of

4. The following account on amateur music clubs is based on my own research on nanguan and on amateur music clubs in Changhua County (see Wang 2000) as well as on recent studies of amateur music clubs, such as Qiu 1980:30-45 and 1992:242-62. For a comprehensive survey of amateur music clubs in Changhua County, see also Hsu 1997 and Lin 1997.

danger.

Traditionally, only men were allowed to participate in the ama-teur music clubs, while women were prohibited, since only profes-sional female entertainers would perform in public. Thus, few females of good social standing were allowed to participate in ama-teur music clubs.

An amateur music club normally consisted of three types of par-ticipants: the director, the members, and the financial supporters. The director was usually a local strongman and was in charge of the management of the club. The members included both the artists who actually practiced the arts and the helpers who contributed to the club activities through their time and labor. The financial supporters gave money to help sustain the club and its activities.

All three of the above types of participants considered club par-ticipation as an honour and as a way to contribute to communal life. Club members took pride in their amateur status, because, unlike the professional actors and actresses who had low social status, they dis-dained performing for money, and only temple gods or fellow club members could enjoy the privilege of their services. Honorarium received from such services belonged to the club, not to the individ-ual participants. Club participation was often time and money con-suming, and only people who could afford it could participate in these clubs. Consequently club membership symbolized good social standing and decent family background, not unlike the study of piano and violin in today’s Taiwan society. Furthermore, club partici-pation was regarded as a way to pay tribute to the temple gods, for temple festivals could not do without the music and operas put on by these clubs through processions or through stationary perform-ances to entertain the gods and the community. It was the duty of these clubs to perform for the festival of the temple that they were associated with (each club was traditionally associated with one par-ticular temple). As a result, social elites voluntarily put in money and effort to organize and support amateur music clubs, and parents also voluntarily sent their children to study in these clubs. Hence, tradi-tional performing arts had been transmitted from generation to gen-eration, not as conscious effort to keep cultural heritage alive, nor

with governmental support, but simply as a familiar way of life. When the clubs performed during temple festivals, it was a time for them to display their artistry as well as their manpower and material resources (such as their banners and other properties) in order to win honor for the villages/communities and the temples they represented. Hence there had been an implicit element of petition among these clubs. Sometimes clubs even held open com-petitions, known as pinguan (literally “competing clubs”) or leitai (literally “fighting platform”), to challenge one another in their artistry. Such implicit and open competitions helped improve the artistry and skill of these amateur clubs.

When the clubs wanted to improve their artistry or to learn a new kind of art form, they would invite teachers to offer a course, known as kaiguan (literally “opening a course”). A course usu-ally lasted four months but, minus holidays, the actual teaching only lasted 100 days (Lü 2002: 163).5 Teachers were treated with good salary and high respect. Except in special cases, students normally had to pay tuition. Clubs taught by the same teacher usually consid-ered one another as sibling clubs and had the obligation to help one another in times of need, such as during parades or competitions.

The musical and operatic genres practiced by these amateur music clubs can be largely divided into two systems, namely nan-guan and beiguan (literally “northern pipes”). The system of nanguan refers to the musical and operatic genres originating from the southern part of Fujian province and consists of nanguan music and its related genres, which include either the rustic derivations of

nanguan music, such as taiping ge , tianzi mensheng

, and chegu , or regional operas based on nanguan music, such as nanguan opera and gaojia opera . The sys-tem of beiguan consists of beiguan music and luantan opera

, both of which are made up of musical and operatic elements originating from north of Fujian province (for more, see Wang 2002a; for a general introduction to nanguan, see Wang 2002b).

5. Some also say that a course lasts for three months. For example, see Hong 2001:109.

III. An Overview of Cultural Policy in Postwar Taiwan

The above depiction generally reflects the situation of amateur music clubs during the period when Taiwan was under Qing dynasty rule (i.e. 1683-1895) and during the Japanese colonial period (1895-1945). After the Nationalist government took over Taiwan in 1945 after Japan lost the Pacific War in World War II, however, amateur music clubs gradually declined under the Nationalist government’s cultural policy to promote Western and national art forms and rele-gate local traditional ones.In the following section, I will briefly outline the various stages of cultural policy in Taiwan and its links with socio-political changes in Taiwan society. Since this is a vast topic, I will mainly focus on the aspects that are relevant to amateur music clubs and local tradi-tional arts.6

1. Before 1945

Recent studies show that amateur music clubs already existed in Taiwan during the early half of the 18th century (see Li 1989:29-32, Qiu 1992:271). Although we don’t know much yet about the state’s stance toward amateur music clubs in Taiwan during the Qing dynasty, writings by Chinese officials and literati of the period docu-mented an abundance of musical and operatic performance activities during temple festivals and other festive occasions.

After Taiwan became a colony of Japan in 1895, the Japanese colonial government took a tolerant attitude towards Taiwanese lan-guage, religion, and culture. Such a tolerant attitude, coupled with the stable and prosperous economy in Taiwan during this period, enabled the amateur music clubs to flourish (Qiu 1992). According to Qiu Kunliang’s estimation, there were about one thousand ama-teur music clubs throughout the island during this time, thus making the Japanese colonial period a heyday for amateur music clubs (ibid.:251).

6. For a comprehensive survey of the government cultural policy in postwar Taiwan, see Su 1998, 2001; Su 2002.

After the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1937, however, the activities of the amateur music clubs were discouraged and even prohibited, as the Japanese colonial government began to exert tight control over Taiwanese culture as part of its kôminka or Japanization movement. After the Pacific War started in 1941, the Japanization movement intensified and continued until Japan lost the war in 1945 and returned Taiwan to China, which was then ruled by the Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek .

Although the amateur music clubs were greatly affected by the harsh wartime control and conditions, they did not completely lose their life force. Some clubs practiced in secrecy, while other clubs were even invited by the Japanese government to perform for radio programs in order to appease the Taiwanese people (see Wang 2002c). In some remote rural areas, clubs were also allowed to give out-door operatic performances (Chen 1999:122). Thus, as soon as the war ended in 1945, many amateur music clubs, together with the professional operatic troupes, quickly resumed their activities and flourished again. Hence the first few years after the war were often considered as the second golden period for traditional performing arts in Taiwan.

2. 1945 to 1970

The post-colonial heyday of the amateur music clubs quickly ended, however, under the authoritarian rule and the mainland-China-oriented cultural policy of the Nationalist government. As soon as the Nationalist government began its rule on Taiwan in 1945, a series of policies were implemented to resinicize the Taiwanese and to suppress the local culture. Among the most damaging of these policies was the promotion of Mandarin as guoyu (“national language”) and the suppression of local dialects, which began in earnest in 1946, and the economization of temple festivals beginning in 1947. Both of these policies lasted for several decades and had long-lasting negative effects on amateur music clubs. The language policy alienated the youngwe generation from their mother tongue and their native culture. Consequently, many lost their motivation to participate in amateur music clubs. The “downsizing” of temple

festi-vals further deprived the amateur music clubs of one of the most important functions of their existence.

After the Nationalist government retreated from Chinese main-land to Taiwan in 1949 after being defeated by the Chinese Communist Party, the island became the military and economic base for the state’s mission to recover China. Meanwhile, it also became the “temporary” home for the two million mainlanders who followed the Nationalist government in exile. As a result, policies were imple-mented to propagate anti-Communist ideology and to enforce the identification with mainland China as the motherland for not only the mainlanders but also the Taiwanese. This was done through school education and through appropriating cultural and art forms as the state’s propaganda tools.7 The indoctrination of mainland China as the lost motherland further estranged the younger generation from the native culture of the island.

After the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in China in 1966, the Nationalist Government launched the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement in 1967 to reinforce Chinese ethics and to promote Chinese gentry culture as national culture in order to prove itself as the true guardian of Chinese culture and the legitimate ruling regime of China. The art forms promoted included guoju “national opera” (namely “Peking opera”), guoyue “national music” (westernized Chinese instrumental music), and guohua “national painting” (brush painting). These art forms received full governmental support and were widely promoted in school and society through various campaigns (see Guy 1999 and Su 2002 for details about the promotion of Peking opera). In contrast, local Taiwanese art forms were largely ignored and marginalized.

While forging “national” culture on the one hand, the quest for modernization also led the Nationalist government to promote Western classical music on the other hand through the founding of a

7. These cultural and art forms included combat literature, patriotic songs, and local operatic genres. For a discussion on literature, see Hsiau 2000. For the state use of budaixi (glove puppet theatre) as a propaganda tool by the state, see Chen Longting 1998.

state symphony orchestra (see Qiu 2002) and through implementing a music education that focused mainly on Western art music (see Chen Yuxiu 1998). As a result, “music” without any qualifier became synonymous with Western art music for most people in Taiwan (for similar situation in Japan and Korea, see Tokumaru 1980; Killick 2002:804).

In addition to Western art music, American popular culture and Western modernist avant-garde expressions also exerted great influ-ence on the cultural scene in Taiwan. Due to the Nationalist govern-ment’s reliance on America as its most important foreign ally, American popular culture was extensively imported into Taiwan and became a model for the general public to emulate. Meanwhile, intel-lectuals and artists in Taiwan were fed up with the state’s stifling ide-ological control and looked to Western modernism for both escape and inspiration. All these western art forms made the musical and operatic genres practiced by amateur music clubs look all the more outdated.

Mass media, industrialization, and urbanization brought further challenges to amateur music clubs. With mass media, people no longer spent their leisure time in amateur music clubs or participated in communal activities. Moreover, industrialization and urbanization brought many youngsters to urban centers for work or study, leaving the villages inhabited mostly by the elderly, women, and small chil-dren. Thus, amateur music clubs lacked the young men needed to continue their activities.

All the above factors contributed to the decline of the amateur music clubs during this period, many of whose activities either diminished or completely stopped.

3. Since 1970

The 1970s marked an important turning point for Taiwan. Setbacks in the Republic of China’s foreign relations in the 1970s8 8. For example, Taiwan was forced out of the United Nations in 1971. In 1972, American President Nixon visited China and the USA-Taiwan relationship deterio-rated. In the same year, Taiwan’s official diplomatic relationship with Japan was

and Chiang Kai-shek’s death in 1975 brought instability to the Nationalist government and forced it to reform itself and to take a more tolerant attitude toward the Taiwanese people and culture. Intellectuals also began to reflect on the Western modernism’s domi-nance in Taiwan and to re-examine the issue of Taiwan’s political and cultural identity. A series of movements were undertaken to advocate the “return to the native” (“huigui xiangtu” ) in various cultural domains (for an over-all examination, see Hsiau 1991:111-16; for literature, see Chang 1999:412-16; for music, see Zhang 1994).

In 1977, the Nationalist government’s new leader, Chiang Ching-kuo , the son and successor of Chiang Kai-shek, announced the policy of “cultural development” (wenhua jianshe ) as part of his “Twelve Development Projects” (Shi’er xiang jianshe

), with the specific goal to construct local cultural centers in every city and county in Taiwan. The task to implement this plan was taken up by the Ministry of Education (hereafter the MOE). Twenty-two local cultural centers were eventually construct-ed, with nineteen of them completed between 1981 and 1986 and three more in the 1990s (for details, see Lü 2002:23-25).

Chiang’s policy of cultural development also marked the begin-ning of the state intervention in traditional arts. In 1979, the Executive Yuan announced a “Plan to Reinforce Cultural and Recreational Activities” (Jiaqiang wenhua yule fang’an

), and the MOE also announced the “Plan to Promote Artistic Education” (Tuixing wenyi jiaoyu huodong fang’an

). Both plans included the goal to preserve and pro-mote traditional arts (for details, see Zhang 1995). In 1981, the above-mentioned plan announced by the Executive Yuan led to the establishment of the Council for Cultural Planning and Development (whose name in English was later changed to the Council for Cultural Affairs, hereafter CCA) in 1981. The same plan also led to the passing of the Cultural Property Law (Wenhua zichan terminated. In 1979, Taiwan’s official diplomatic relationship with USA was also ter-minated.

baocun fa ) in 1982, which became the legal basis for the ensuing state intervention in cultural property (for details of this law, see Su 2002:217-18). Modelled after the Korean and Japanese systems, the Law included the protection of both tangible and intangible cultural property, with traditional performing arts belonging to the latter category. This Law entrusted the MOE to be in charge of the protection of traditional performing arts. The Law also stipulated the protection of traditional artists and of honoring the particularly outstanding ones as National Artists (Guojia yishi

) (Chen [1981]1984:77).

To carry out its task to preserve traditional arts, the MOE first commissioned two scholars to carry out two multi-year surveys of traditional artists in Taiwan, including those genres brought from mainland China to Taiwan after 1945 and those of the local tradition-al arts (see Yin 1982:1).9 These surveys lasted from 1980 to 1990, with initial results completed in 1983 and 1984 (see Yin 1983; Lin 1984a and 1984b). Based on the results of these surveys and the rec-ommendations of the scholars, the MOE set up the Traditional Arts

Heritage Award (Minzu yishu xinchuan jiang ,

here-after Heritage Award) in 1985, which it continued to award annually until 1994.10In 1989, the first round of the selection of the Important Traditional Artists (Zhongyao minzu yishi ) was held. From 1991 to 1994, the MOE implemented the “Zhongyao minzu

yishi chuanyi jihua” (Important Traditional

Artists Transmission Projects).11

9. The two scholars commissioned are Lin Enxian , Professor of Sociology and Director of the Graduate Institute of Frontier Administration at

National Chengchi University (the Institute was changed

to the Graduate Institute of Ethnology in 1990 and was enlarged into the Department of Ethnology in 1993), and Yin Jianzhong, Professor of Anthropology at the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at National Taiwan University . For details on these two sur-veys, see He 1995:8.

10. For details of the setting up of the award and the selection process, see Zhou 1986 and Zheng 1986.

In parallel to the MOE, CCA also made efforts to promote tradi-tional arts. These efforts included sponsoring folk arts festivals and concerts, planning several folk arts recreational parks (minsu jiyi

yuan ) in different parts of Taiwan (see Su 1998:19; Zeng

1987; Zhang 1995: 82-83), and setting up a “planning team” (choubei xiaozu ) for the Center for Musical Heritage (Minzu yinyue zhongxin ) within the Council in 1990.12 Moreover, CCA also guided local cultural centers to start planning specialty museums to feature local cultural characteristics (see Su 1998:17).

Both the efforts of the MOE and CCA on traditional arts outlined above, however, could not completely shed the Nationalist ideology of taking Taiwanese culture as part of Chinese culture and of “regarding Chinese and modern refined arts as higher in level than local traditional arts” (Su 2001: 64).13

It was not until the lifting of martial law in 1987 that “Taiwanese consciousness” (Taiwan yishi ) came into a full bloom in Taiwan society. As a response, the state’s cultural policy also began to put increasing emphasis on local Taiwanese culture. In 1991, the MOE announced the policy to promote traditional arts in elementary and junior high schools and allocated special funding for schools to offer training courses on traditional arts as extra-curricular activi-ties.14 In 1994, the MOE further required junior high schools to include native culture in their curriculum design (Zhang 1999: 61).

Similarly, CCA’s cultural policy also responded to the rise of

12. The Preparatory Office of the Center for Musical Heritage was eventually founded in 1999.

13. For example, the surveys of traditional artists commissioned by the MOE put much emphasis on regional genres brought by mainlanders to Taiwan; the recipients of the Heritage Award also included a substantial number of the artists of these mainland genres. Similarly, mainland genres also occupied a considerable portion of the folk arts recreational park planned by Zeng Yongyi under the commission of CCA (see Zeng 1987). Also see Su 2001:64.

14. For details on the regulations of this policy, see “Guomin zhongxiaoxue tuizhan yishu jiaoyu shishi yaodian”

(Implementation of the Promotion of Traditional Arts Education in Elementary and Junior High School) at http://www.eje.ntnu.edu.tw/dta/onell/2001117151/3-13.htm.

Taiwanese consciousness by turning toward localization and decen-tralization. To implement this policy, CCA reformulated its annual “Culture and Arts Festival” (Wenyi ji ) into the first “Nation-wide Culture and Art Festival” (Quanguo wenyi ji ) in 1994, which entrusted each local cultural center to design its own festival featuring local cultural characteristics. It is through this festi-val that local cultural centers became mobilized to make use of the local cultural resources and to design programs relevant to the life of their local people (for details, see Su 1998).

In 1995, after the MOE completed the above-mentioned “Impor-tant Traditional Artists Transmission Project,” CCA replaced the MOE to become the state-agency in charge of the task to preserve and promote traditional arts. In the same year, CCA launched the first full-fledged “Traditional Arts Preservation Project” (Minjian yishu

baocun jihua ).15 In 1996 CCA founded the

Preparatory Office of the National Center for Traditional Arts as one of its adjunct organizations to take charge of all matters related to traditional arts.

In 2000, after Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic

Progressive Party won the presidential election and ter-minated the fifty years of the Nationalist government’s rule on Taiwan, state cultural policy officially entered a new era with an obvious focus on local Taiwanese culture.

It is with this general background in mind that I now turn to state intervention in nanguan.

IV. Nanguan’s Priviledged Position

Among the local art forms preserved and promoted by the gov-ernment since 1980, nanguan arguably stands out as one of the most supported.16 I propose that it is nanguan’s high social status, 15. This project was deemed by many as the largest in scale compared with the preceding state projects on traditional arts. See, for example, Lin 1998:208.

16. For example, according to Xue Yinshu, a veteran CCA official, any propos-als related to nanguan tend to get CCA’s funding without much difficulty (Xue 2003).

its neutral political position, and the recognition of nanguan’s histor-ical value by domestic and foreign scholars, that made it a “sacred cow” for governmental support.

1. High Social Status

Nanguan music clubs share most of the features of amateur music clubs described above. However, nanguan music clubs differ from the other amateur music clubs in the high social status it enjoyed. Such a high social status has much to do with nanguan music’s archaic features, refined artistry, elegant and introspective style, and sophisticated music theory and rules for performance, all of which require a lifetime to master. Hence nanguan musicians are often regarded as cultivated people who have enough time and money to indulge themselves in the refined arts of nanguan.

Another reason that contributed to the high social status of nan-guan was its legendary association with the imperial courts. According to a popular legend, five nanguan musicians from south-ern Fujian province were invited to perform for Kangxi Emperor

(1654-1722) on his 60th birthday, and the Emperor bestowed these nanguan musicians with the honorific title “yuqian qingke”

(literally “elegant guests before the emperor”) as well as the yellow parasol and the lantern. Although this legend cannot be veri-fied with historical evidence, it has been widely circulated among nanguan musicians up to this day and constitutes an important fac-tor for the pride of nanguan musicians (for more details on this leg-end, see Chou in press).

Interestingly, this legend was also widely known among Japanese officials during the Japanese colonial period. This made nanguan a preferred art form to present to the Japanese imperial family during their visits to Taiwan as well as to the Japanese gov-erner-generals and other officials stationed in Taiwan. The most famous incident was the visit of Shôwa Tennô (Shôwa emperor) to Taiwan in 1923 when he was still Prince Hirohito

(see below).

Beside royal patronage, nanguan’s high social status can also be evidenced by the privilege that nanguan music clubs enjoyed

during temple festivals. It has been reported that some temple gods in Tainan County allegedly appeared in the dream of the luzhu (the person in charge of the temple festival) to request the honor of the inclusion of nanguan music in the temple festival procession, and this was how several nanguan music clubs were started (You 1997).

Nanguan’s high social status is also much related to the fact that they were usually supported and participated in by gentry. Stories abound about how people of low social status, such as pro-fessional entertainers or hairdressers, were prohibited from joining nanguan music clubs, and how nanguan musicians who taught female entertainers or the professional operatic troupes were driven out of the nanguan clubs they originally belonged to.

2. Neutral Political Position

Another factor that accounts for nanguan’s favorable position in governmental funding can be attributed to its neutral position in the sense that nanguan is neither completely “Taiwanese” nor “Chinese”. Nanguan is one of the few genres that came from China and are still practiced in both regions. Moreover, nanguan’s lyrics are sung in Quanzhou dialect, which is quite different from the Taiwanese dialect and is still spoken now in the city of Quanzhou in mainland China. In addition, prior to 1949, the nanguan music circle in Taiwan had always maintained continuous contact with the nan-guanmusic circle in southern Fujian. Many nanguan music clubs in Taiwan were taught by nanguan musicians that came from Quanzhou or Amoy (known as Xiamen in China). Therefore, they inherited the repertoire and the performance style of the nan-guan music in southern Fujian. Furthermore, because of the close connection between Taipei and Amoy during the Japanese colonial period, there were even formal ties that existed between some nan-guanmusic clubs in these two cities; for example, Jixian tang and Qinghua ge of Taipei were the sibling clubs of Ji’an tang

and Jinhua ge in Amoy respectively. As mentioned before, sibling clubs had the obligation to assist one another when occasions of need arised. Thus, when Jixian tang was invited to

per-form for Shôwa Tennô in 1923, Ji’an tang sent several leading musi-cians from Amoy to Taiwan to help them out. This was a good example of the close ties among the sibling clubs between Amoy and Taipei.17

Nanguan was also one of the few musical genres that the main-landers who followed the Nationalist government to Taiwan in the 1940s could share with local Taiwanese musicians. A good example

can be found in the case of Taipei Minnan yuefu ,

which was formed mainly by Fujianese who migrated to Taiwan after 1945 but was also participated in by local Taiwanese musicians (for more, see Wang 1997; Chou in press).

Despite its close links with mainland China, however, nanguan is also typically Taiwanese because it is the oldest genre that was widely popular in Taiwan. One could even argue that nanguan in Taiwan has already developed its own unique style and tradition which distinguish it from the nanguan in mainland China. This is due in part to the fact that Taiwan has more or less kept the style transmitted to Taiwan before 1949, while the nanguan in mainland China had undergone drastic changes under the influence of the Chinese Communist Party’s proletarian policy toward the arts.18

3.Recognition by Domestic and Foreign Scholars

Among the various musical and operatic genres in Taiwan, nan-guanwas one of the first to receive the attention of foreign scholars for its historical value. As early as 1922, Tanabe Hisao , the first Japanese musicologist to do fieldwork on music in Taiwan, already proclaimed nanguan’s close resemblance to Japanese court music (Society for Research in Asiatic Music 1968: 184). Beginning in 1950s, several American and British scholars collected nanguan materials and expressed high respect for nanguan’s artistic and

his-17. For more on the links between the nanguan clubs in Taiwan and southern Fujian, see Wang 1995.

18. For more on the art policy in China, see Yang Mu’s article in this volume; for nanguan’s changes under the influence of the cultural policy in China, see Wang 1995.

torical value (see Huang 1981:130-31). For example, after listening to the recordings of nanguan music, American composer Alan Hovhaness wrote an article that extoled nanguan to be the remnant of the music of the Tang dynasty and praised its compositional tech-niques as even more modern than the 20th-century Western contem-porary music (Yu 1981:83). In 1969, American ethnomusicologist Fred Lieberman recorded nanguan music performed by Taipei Minnan yuefu and later released it as part of An Anthology of the World’s Music issued by a foreign label (Lieberman 1971). This was the first record of Taiwan’s nanguan music issued by a foreign record company.

Domestic scholars also began to patronize nanguan as early as the 1950’s. For example, nanguan musicians were invited to per-form and teach at National Taiwan Normal University

and Soochow University in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1960s and 1970s, Liang Tsai-ping , the then president of the Society for Chinese Music (Zhonghua guoyue hui ),19 organized several concert opportunities for nanguan clubs, made arrangement for Lieberman’s recording, and introduced nanguan music to several other foreign scholars (for more, see Liang 1983; Huang 1981:131; TCB 2002a:104-05). Meanwhile, several other domestic scholars wrote about the historical value of nanguan (see Schipper and Hsu 1983:51; Huang 1981:131-32).

Starting in the mid-1970s, with the rise of the “return to the native” movement among the intellectuals, scholars and social elites began to carry out activities to preserve and promote folk arts. With its unique social and political position, nanguan naturally became one of the first objects of such salvaging efforts. These efforts includ-ed fieldwork investigation on nanguan clubs, publication of indices of nanguan manuscripts, presentation of nanguan in folk arts con-certs and festivals held domestically, and presentation of nanguan in

19. Liang Tsai-ping had been the president of the society from 1954 to 1979. The society later changed its Chinese name to Zhonghua minguo guoyue xuehui (Society for Chinese Music in R.O.C.) in 1982. For more, see society’s website at http://www.scm.org.tw/htm/introduce.htm.

international conferences and concert tours held abroad. Most of the initiatives and funding of these activities came from scholars and social elites.

Particularly active was composer and ethnomusicologist Hsu Tsang-houei , who played a vital role in pioneering scholarly intervention in nanguan. From 1976 to 1982, he made a series of promotional and research activities on nanguan.20Most importantly, Hsu presented nanguan concerts by Tainan Nansheng she

in Korea and Japan, which marked nanguan’s first live perform-ance in foreign countries outside of Southeast Asia, where many nanguan groups existed. In the same year, Hsu led a research team to carry out the first in-depth documentation of the history of nan-guan clubs and musicians in Lukang. In 1981, Hsu organized the first conference on nanguan, which established nanguan’s historical value in Taiwan.

The nanguan groups patronized by Hsu and other scholars during this period included Taipei Minnan Yuefu, Tainan Nansheng She, and the two veteran nanguan groups in Lukang, namely

Lukang Yazheng zhai and Lukang Juying she

(men-tioned above).

Beside the patronage by domestic scholars, Tainan Nansheng she’s concert tour in Europe in 1982 further established nanguan’s academic value internationally. Arranged by Kristofer Schipper, a

20. Hsu presented Taipei Minnan yuefu in the Asian Composers’ League held in Taipei in 1976, invited Lukang Juying she to perform in the first Folk Artists Concert (Minjian yueren yinyue hui ) he organized in 1977, and carried out fieldwork on nanguan clubs in Lukang in 1978. After Hsu founded Chinese Folk Arts Foundation in 1979, he organized a research team to carry out a project to document the history of nanguan clubs in Lukang, investigat-ed and made sound recordings of Tainan Nansheng she, and took Tainan Nansheng she to perform in the Asian Composers’ League held in Korea, followed by a concert tour in Japan. In 1981, Hsu organized the first conference on nan-guan. In April 1982, Hsu organized a lecture-concert tour of nanguan on the island as the 21st Folk Artists Concert, in which Kimlan langjun she ( ) of the Philippines performed with nanguan groups in Hsinchu , Lukang, Tainan, Kaohsiung , and Taipei. For details, see TCB 2002a and Chinese Folk Arts Foundation 1989:46-52.

sinologist and Taoist specialist then based in France, Tainan Nansheng she toured Europe for twenty-five days, giving concerts in five countries, including an all-night concert (from 10 p.m., Oct. 22, to 6 a.m., Oct. 23) at Radio France with simultaneous broadcast all over Europe, as well as a five-hour seminar on Oct. 25. The three-week tour was so unexpectedly well-received that, according to Schipper, “nanguan conquered the hearts of the European music lovers” (Schipper and Hsu 1983:53). The impact of the 1982 tour cannot be overestimated. Its success made nanguan an overnight star on Taiwan.21 The success of the 1982 tour, coinciding with the government’s new policy to promote local culture, marked the beginning of the government’s involvement in nanguan activities for the past two decade.

V. State Intervention in Nanguan

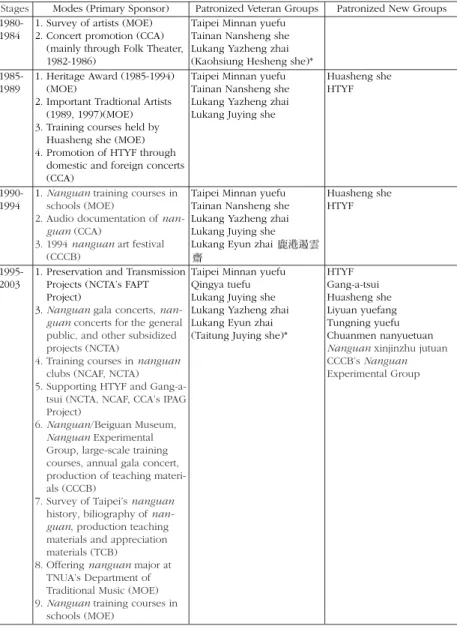

In the following section, I will examine the past two decades of state intervention within four stages: 1980-1984, 1985-1989, 1990-1994, and 1995-2003. Each stage was marked by the beginning of new modes of state intervention in nanguan and traditional arts. Some activities held within one period might have extended to the next. Hence, I make the following periodization mainly to delineate general trends of development, and it should not be taken as clear-cut demarcation.

1.1980-1984

During this first stage, although promotion of traditional arts relied mostly on the initiatives of scholars and social elites, state agencies began to take more active steps to preserve traditional arts

21. From Dec. 15 to 28, 1982, the China Broadcasting Corporation

(a governmental radio station) produced a series of programs introducing nan-guan. Meanwhile, newspapers reported the success of the tour and the significance of nanguan. On Dec. 28, Tainan Nansheng she performed as part of a public con-cert in Taipei. Thus, “from October to December, from Europe to Taiwan, nanguan enjoyed the greatest attention it has ever received” (Lü 1986:119).

through documentation and through presentation in folk arts festi-vals.

1) Surveys of Traditional Arts Commissioned by the Ministry of Education

The above-mentioned two surveys commissioned by the MOE contained some documentation about the state of nanguan music in several counties in Taiwan and the names and contact means of dozens of nanguan musicians, as well as some life histories of a few nanguan musicians.22 In 1984, Taiwan Provincial Government

also commissioned National Taiwan Academy of the Arts to conduct a survey on local traditional arts, and the result contained some short introductions to several nan-guan musicians (National Taiwan Academy of the Arts 1984:26-35). Although these surveys were superficial and contained obvious errors, they were the first island-wide surveys on nanguan and other traditional arts and provided information which would have other-wise been lost. While these surveys have mostly been neglected by scholars, they deserved much more attention.

2) Folk Theatre Festival Sponsored by the Council for Cultural Affairs

In parallel to MOE’s efforts, CCA sponsored a large-scale folk arts festival entitled “Folk Theatre” (Minjian juchang ) as part of its annual “Culture and Arts Festival” ( Wenyi ji ). This “Folk Theatre” festival took place from 1982 to 1986, and nanguan was presented every year except for 1983.23

A review of the nanguan groups presented in this festival shows that even though nanguan was featured almost every year,

22. See Yin 1982:passim; Yin 1983:29, 195-96; Lin 1984a: passim; Yin 1988:127-42; Yin 1989:633-37.

23. The nanguan clubs presented included: Minnan yuefu (Taipei), Yazheng zhai (Lukang), and Nansheng she (Tainan) in 1982; Nansheng she (Tainan) in 1984; Minnan yuefu (Taipei) in 1985; Huasheng she (Taipei) and Hele she (Kaohsiung) in 1986.

the nanguan clubs presented were limited to only five clubs, with the first few years concentrated on the nanguan clubs already pro-moted and researched by Hsu Tsang-houei in the late 1970s (see above). It was only in 1986 that two additional nanguan clubs were presented. This is not surprising since these festivals were organized by scholars closely associated with Hsu Tsang-houei and the Chinese

Folk Arts Foundation that he founded in 1979.

Hence they foreshadowed the tendency for the state resources to be concentrated on the few nanguan clubs patronized by these schol-ars.

Beside state-level agencies, city and county level governments also held similar documentation and promotional activities, although on a smaller scale.24

2.1985-1989

After 1985, documentation and promotional activities of nan-guan continued. Meanwhile, new forms of intervention which awarded both national recognition and financial gains began to emerge during this period. These included the holding of the Heritage Award, the appointment of the Important Traditional Artists, and the revitalization of old nanguan clubs, and the patronage for new nanguan groups.

1) Heritage Award

As mentioned above, the Heritage Award set up by the MOE was held from 1985 to 1994. In its first few years, the awardees only received the honor without a monetary prize; in the latter years, each awardee was given an honorarium of NT$50,000 (Li 1997:61; Yin 1991:6).25

24. For example, nanguan was presented in the music festival held in Taipei in 1980 (TCB 2002a:106). In 1984, Changhua County Government commissioned Hsu Tsang-houei to carry out a one-year survey of folk arts in the county, including its nanguan clubs (Chinese Folk Arts Foundation 1999:30-35).

25. The exchange rate between US and New Taiwan dollars from 1990 to 1994 averaged around US$1=NT$26 (see Guo 2002).

Among the 132 individuals and 42 groups who received the award, six nanguan groups and six nanguan musicians were awarded in the category of traditional music and narrative singing, and two nanguan opera performers were awarded in the category of traditional opera.26

From the nanguan groups and musicians and opera performers awarded, we can make the following observations:

i. Among the six nanguan musicians and two nanguan opera performers awarded, only three of them were born in Taiwan. This was in stark contrast to the other awardees of the other local genres, who were all born in Taiwan. This reflects the ambiguous identity of nanguan as neither completely Taiwanese nor completely mainland Chinese, as mentioned above.

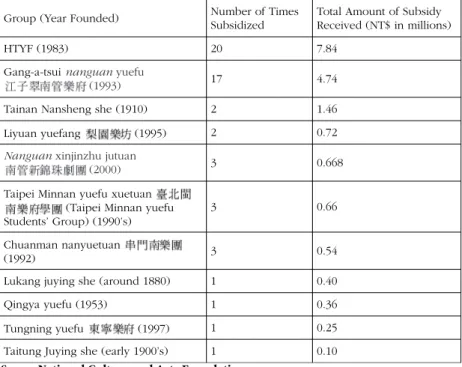

ii. All of the six nanguan musicians awarded were active in Taipei (except for Lao Hong-gio , who lived in the Philippines). Thus we see a concentration of state resources 26. The nanguan musicians and music clubs that received the Heritage Award include the following: 1985: Nansheng she (nanguan club in Tainan, founded around 1910); 1986: Yazheng zhai, Juying she (nanguan clubs in Lukang, with the former founded around mid-18th century and the latter in the late 19th century); 1987: Yu Chengyao (nanguan musician, 1898-1993, who was born in southern Fujian and moved to Taipei after 1945), Li Xiangshi (nanguan opera performer, 1911-2003, who was born in southern Fujian and had been living in the Philippines until he moved to Taiwan in the 1980s); 1988: Huasheng nanyue she (nanguan group in Taipei, founded in 1985 by Wu Kunren

), Wu Suxia (nanguan opera performer and veteran nanguan musician, born in 1940s, active in Taichung area in mid-Taiwan); 1989: Tsai Tianmu

(nanguan musician, 1913- , born in Taiwan, active in Taipei area); 1990 : Wu Kunren (nanguan musician, 1917- , born in Taiwan, founder of Huasheng Nanyue she, active in Taipei area); 1990: Cheng Shujian (nanguan musician, 1918- , born in southern Fujian and moved to Taiwan after 1945, active in Taipei area); 1991: Lao Hong-gio (nanguan musician, 1907-2000, who was born in southern Fujian and lived in the Philippines); 1992: Hantang yuefu (nan-guan group in Taipei, founded in 1983 by Chen Mei’e ); 1993: Minnan yuefu (nanguan club in Taipei, founded in 1961, mainly consisting of musicians who moved to Taiwan after 1945); 1994: You Qifen (nanguan musician, 1924-1999, born in southern Fujian and moved to Taiwan after 1945).

in the Taipei, where the state government is located.

iii. Among the six nanguan groups awarded, four of them were presented or researched by Hsu Tsang-houei in the late 1970s, as mentioned above.27 Thus we see an example of how scholarly patronage had important influence on the dis-tribution of state resources on nanguan groups.

iv. The other two groups, Huasheng she and Hantang yuefu , were all very young groups, with the former found-ed in 1986 and the latter in 1983. In addition, Huasheng she and its founder Wu Kunren were both award-ed (with the group awardaward-ed in 1988 and Wu himself in 1990). This indicates the rising status of these two new groups (see below).

Since the MOE stipulated that the candidates for the Heritage Award must be nominated by only certain qualified organizations, this award not only created a sense of competition among musicians and groups but also enhanced the reliance of musicians on scholars or other cultural bureaucrats as their mediators and patrons.28 Qiu Kunliang also observed how this award became a mere for-mality (Qiu 1997a:238-41). The Heritage Award was finally terminat-ed after 1994 and was replacterminat-ed by a similar award held by a private foundation.29

27. Again, this refers to Yazheng zhai and Juying she in Lukang, Nansheng she in Tainan, and Minnan yuefu in Taipei.

28. I myself was asked by a nanguan musician to recommend him in this award. Li Xiu’e (1997:61) also reported that it was Hsu Tsang-houei who helped Yazheng zhai get the Heritage Award, but this prompted Juying she (which has been Yazheng zhai’s rivalry) to find ways to get the award as well; in the end both groups were awarded in the same year.

29. This is the Global Chinese Culture and Arts Award

organized by the Republic of China Jaycees Club . This award was originally started in 1993 and was entitled Ten Outstanding Youth Heritage Award . In 1995, it was renamed The Third Outstanding Chinese Culture and Arts Award . In 1996, it was expanded to accept candidates from the Chinese diaspora (including main-land China) and was renamed The Fourth Global Chinese Culture and Arts Award . This award has continued up to the time of this

Even though the Heritage Award was terminated in 1995, it con-tinued to function as an important credit for its recipients to get social recognition as well as governmental patronage. Meanwhile, governmental funding on artists often used this award to determine the grading of artists in terms of their hourly payment and future prospects for gaining governmental funding.30

2) Important Traditional Artists

In 1989, the MOE held its first election of the Important Tradtional Artists. This represented the highest honor for traditional artists and included monthly salaries for the awardees as well as training projects initiated and fully funded by the Ministry. Only six artists were elected, including Li Xiangshi the veteran nan-guan opera teacher who had received the Heritage Award in 1987. No nanguan musicians were awarded, however.

From 1991 to 1994, the MOE implemented the transmission projects for these Important Tradtional Artists, but only limited results were achieved due to the difficulty in procuring serious stu-dents and to the old age of the artists (see MOE 1995 for a review of the award and the projects).

The election of Important Tradtional Artists was held again in 1997, but this time the artists only received a plaque as a token of honor. Again, no nanguan musicians were elected.

writing. 128 people had received this award up to the year 2002. Starting in 1996, this award has received funding from various organizations, including governmen-tal agencies such as MOE and CCA. For details, see http://www.abridge.com.tw/ myway/my-5g-593.htm. Two nanguan musicians have received this award, includ-ing Chen Mei’e in 1997 and Wu Suxia in 1999 (TCB 2002a:110-11). Both of them also received the Heritage Award offered by the MOE (see above).

30. It should be added that when the Taiwan Provincial Government estab-lished its Cultural Division in 1998, it also set up an award for traditional artists entitled the Folk Arts Lifetime Achievement Award . Two veteran nanguan musicians, Zhang Hongming and Zhang Zaiyin

, received this award (TCB 2002a: 110). This award, however, was quickly termi-nated due to the abolishment of the Taiwan Provincial Government in 1999.

3) Revitalizing Veteran Nanguan Clubs

In 1985, the CCA commissioned the Chinese Folk Arts Foundation to carry out the first state-funded project to help revital-ize Lukang Yazheng zhai, the oldest remaining nanguan club in Taiwan. The actual steps taken included making recordings, compil-ing the club’s manuscripts, revivcompil-ing the clubs’ regular rehearsals, and recruiting new students for the club. Despite the original long-term plan, however, this project only lasted for one year, from January to December, 1985 (for details, see Chinese Folk Arts Foundation 1989:18; 1999:44-45; Lin 1986).

4) Patronizing new groups: Hantang yuefu and Huasheng she

In contrast to this short-lived project to revitalize old nanguan clubs, two newly founded nanguan groups, namely Hantang yuefu (here after HTYF) and Huasheng she, were gaining increasing state patronage during this period. Both groups started out as one-man companies, with the former founded by a young, ambitious female musician, Chen Mei’e (1954- )31 in 1983, and the latter by an old veteran nanguan musician, Wu Kunren (1917- ),32 in 1986. Located in Taipei, both groups succeeded in building connections with scholars and governmental officials and subsequently rose to stardom in a short time. HTYF specialized in presenting nicely pack-aged nanguan concerts and in making concert tours abroad.33 31. Chen began to study nanguan at Tainan Nansheng she in the 1970s and participated in the club’s 1982 concert tour in Europe. After coming back from Europe, Chen left Tainan Nansheng she and founded her own group in Taipei at the age of 29. Chen’s action caused much controversy among nanguan practition-ers, especially since it was unprecedented for a nanguan club to be founded by a female musician.

32. Wu began to study nanguan at the age of fourteen (1931), started to teach in nanguan clubs when he was seventeen (1934), and had been performing and teaching nanguan in different parts of Taiwan until the early 1980s (Lin 2002).

33. HTYF’s first foreign concert tour took place in the United States in 1986. Under the arrangement of Wang Ch’iu-kui (a professor), the group per-formed in Chinoperl conference in Chicago and in leading universities, including Harvard University, University of Pittsburgh, University of Pennsylvia, Princeton University, Yale University, University of Washington, University of California at Los

HTYF’s funding mainly came from CCA, most likely because HTYF’s nicely packaged nanguan concerts fit well with CCA’s goal to pro-mote “high arts” (jingzhi yishu ).34Wu Kunren pioneered in getting funding from the MOE to offer nanguan training courses in various venues.35 Patronized first by Hsu Tsang-houei and later also

by Taipei Municipal Chinese Orchestra (where Wu

taught nanguan from 1988 to 1990), Wu also gained access to many other state resources.36 Wu’s privileged position in state-sponsored projects culminated in 1991 when he was recommended by Hsu Tsang-houei to take charge of organizing the nanguan performance

Angeles, and University of Hawaii (TCB 2002c: 188-89). Subsequently the group has been making annual concert tours in different parts of the world. It also per-formed frequently in Taiwan under the sponsorship of various cultural institutions. For a detailed list of their concerts held domestically and internationally from 1983 to 2000, see TCB 2002c: 188-208. For an account of the group’s intial concert tours, see Wang Ch’iu-kui’s recollection (2002). I’m grateful to Wang Ch’iu-kui for provid-ing me with this unpublished manuscript of his.

34. This is based on the observations made by Xue Yinshu, a veteran CCA offi-cial (Xue 2003).

35. Starting in 1983, Wu was invited by Hsu Tsang-houei to offer nanguan courses to graduate students at National Taiwan Normal University

(NTNU). In 1985, the MOE commissioned NTNU to offer summer courses on traditional arts for school teachers, and Wu was invited by Hsu to teach. In 1987, Wu applied for funding from the MOE to hold training courses in his group and was granted NT$1,967,000 for the first year. Although the first-year training course turned out to be a total failure, with only one student left at the end of the course, Wu managed to get continual subsidy from the state to hold training courses in his group up to this time of writing, albeit with decreasing amount of subsidy each year. Beside offering state-funded training courses in his own group, Wu also began to teach nanguan in state-run institutions, including the Social Education Center Yanping Division from 1987 to the 1990s, and the Taipei Municipal Chinese Orchestra from 1988 to 1990. For details, see Lin 2002.

36. For example, Wu’s group, Huasheng she, began to be presented in TMCO’s Taipei Traditional Arts Festival in 1988. Later TMCO fur-ther provided Wu with resources to host a Southeast Asia Nanguan Gala Concert (entitled “Nantian guanyue shengge Dongnanya nanguan huiyan”

) as part of its TTA Festival in 1990, during which four nan-guan groups from Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore were invit-ed to Taiwan to perform with Huasheng she and Lukang Yazheng zhai.

to be presented at the Second Presidential Hall Concert .

It is interesting to note that both Chen Mei’e and Wu Kunren participated in Tainan Nansheng she’s concert tour in Europe in 1982. It was after this concert tour that Chen left Tainan Nansheng she to start her own group in Taipei in order to realize her aim to revitalize nanguan and to prove the historical value of nanguan. It was also after this concert tour that Wu started his connection with Hsu Tsang-houei and the scholarly world, which eventually led to his active involvement in the cultural politics of nanguan. Thus we see the important role of Tainan Nansheng she’s concert tour in Europe in promulgating scholarly and governmental intervention in nanguan and in fostering nanguan musicians’ self-consciousness about the value of nanguan as a cultural heritage. It also shows again the important role played by scholars as mediators between musicians and the state during this period.

3.1990-1994

In the first half of 1990s, with the rise of “Taiwan conscious-ness”, state intervention in nanguan also entered a new phase. The modes of intervention during this period included state-funded train-ing courses, audio-visual documentation of nanguan, and the hold-ing of 1994 Nanguan Art Festival by Changhuaxian wenhua

zhong-xin (Changhua County Cultural Center ).

1) State-funded Nanguan Training Courses

First of all, MOE’s 1991 policy to promote traditional arts educa-tion in elementary and junior high schools resulted in a proliferaeduca-tion of nanguan training courses offered in public schools as extra-cur-ricular activities.37 Since the MOE allocated special budgets to cover the tuitions and the costs of the instruments, it became the major financial source for these training courses, and musicians usually got paid for their teaching.

37. For the policy, see above. See Chen 1994 for a list of nanguan training courses offered during this time.

Beside public schools, nanguan groups also began to follow Wu Kunren’s example to apply for state funding for offering nan-guan training courses.38 In addition, state orchestras also began to emulate the efforts of Taipei Municipal Chinese Orchestra to offer nanguan training courses to their members and to the common public.39

Although these training courses did provide nanguan with more chances of exposure on a grass-root level and even cultivated some potential nanguan performers or appreciators, they also creat-ed disputes among nanguan musicians over which group or which musicians would teach, and how much they would be paid. Furthermore, much dispute centered on the teaching method. While veteran musicians tended to follow the traditional method of oral transmission, which took a long time to master a piece, younger musicians usually had better communication with the students and also tended to use some new teaching methods, such as teaching the students how to read traditional nanguan notation, and some even resorted to the use of cipher or staff notation. Consequently younger musicians often became more popular among students than veteran musicians even if their artistry might be lower than the veteran ones, and this often created tension among younger and veteran musi-cians.

2) Audio-visual Documentation of Nanguan

During this period, state agencies began to commission the pro-duction of audio-visual documentation of nanguan for the sake of

38. For example, Taipei Minnan yuefu also applied for subsidy from the CCA to start training courses in its club in 1992.

39. For example, Kaohsiung Municipal Chinese Orchestra set up a nanguan group in 1993 and began to offer nanguan training courses not only to their members but also to the public. Meanwhile, Taiwan Provincial Symphony Orchestra initiated a “Nanguan yizhi jihua”

(Nanguan Transplantation Project)in 1992, in which musicians of Yazheng zhai were invited to offer nanguan training courses in Lugu , a place in the high mountains of mid-Taiwan where there used to be no nanguan tradition.

preservation and promotion.40 Most of these recording projects fea-tured either HTYF or Huasheng she, another evidence of the popu-larity of these two new star groups. One of the rare exceptions was the CD-book of nanguan songs which I produced under the com-mission of the CCA. This project was the first large-scale nanguan recording project commissioned by the state. In order to avoid focus-ing on the few star groups, I invited thirteen sfocus-ingers representfocus-ing nine different nanguan clubs to make recordings of their representa-tive pieces.41Due to the old age of most singers recorded, however, many of the recordings had poor vocal quality, and, in the end, only seven songs were selected by a reviewing committee,42 with only four nanguan clubs represented.43 And even the ones included in the final product already showed deterioration in their vocal quality. 40. These include the CD of nanguan wedding music performed by Wu Kunren’s group and produced by CCA in the early 1990s, the set of CD-book of nanguan songs produced by me for CCA and released in 1997, and the CD-book on the appreciation of nanguan performed by HTYF and produced by the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Headquarter in 1994. Beside these, the transplanation project sponsored by the Taiwan Provincial Symphony Orchestra also produced a set of CD and book as teaching materials, performed by HTYF and released in 1994. Huasheng she also issued a set of four CDs under the spon-sorship of Taipei Municipal Chinese Orchestra. Furthermore, Hsu Tsang-houei was commissioned by Taiwan Provincial Government to produce a videotape introduc-ing nanguan in 1994.

41. The groups that were recorded included Taipei Minnan yuefu, Huasheng she, Kinmen Wujiang nanyue she , HTYF, Lujin zhai in Taipei; Qingya yuefu and Hehe yiyuan in Taichung County; Yazheng zhai in Lukang; and Tainnan Nansheng she in Tainan. Moreover, musi-cians from Chiayi and Kaohsiung also participated. For some groups, more than one singer in each group recorded their singing in this project. Hence alto-gether thirteen singers were recorded.

42. The committee was made up of Shen Xueyong (the then director of CCA), Lü Chuikuan (the advisor for the recording project), and myself. The selection was mainly based on the vocal quality of the singers, the importance and rarity of the songs recorded, and the consideration to include both female and male singers in order to show the differences in their singing styles.

43. These are Huasheng she, HTYF, Taipei Minnan yuefu, and Tainnan Nansheng she, with Tainnan Nansheng she occupying the highest percentage (see Wang 1997).

Hence, it is no wonder that the musicians wished that the project had been undertaken ten years earlier. The project also revealed the fact that most veteran nanguan singers were getting old, and few younger singers were ready to succeed them. This in turn implies that the scholarly and governmental efforts to promote and revitalize nanguan since the 1970s had achieved limited results in preserving the performance quality of nanguan clubs either through document-ing the veteran musicians or through traindocument-ing younger ones. One also has to admit that this recording project inevitably added to the sense of competition felt among the musicians, especially regarding which singers and which groups would be chosen to be included in the final product.

3) The 1994 Nanguan Art Festival

The sense of competition among musicians was most clearly manifested during the first nanguan art festival organized in 1994 by

Changhua County Cultural Center (whose name

was later changed to Changhua County Cultural Bureau [Changhua wenhua ju ], hereafter CCCB). This festival was part of CCA’s first “Nation-wide Culture and Arts Festival”, which, as men-tioned above, was the first time when local cultural centers were asked to design their own art festival with themes that could reflect local cultural characteristics.

The planning of the CCCB’s Nanguan Art Festival was under-taken in July 1993, and involved not only the staff of CCCB, but also local cultural workers and nanguan musicians as well as scholars. The festival began in January 1994 and lasted for about three months. It consisted of a series of educational and promotional activ-ities, cultiminating in a two-day out-door gala performance by nan-guan clubs from all over Taiwan on March 26 and 27, and a nan-guanconference on March 28 and 29, which I was commissioned to organize with assistance from CCCB.

During the preparation and the actual implementation of the festival, the staff at CCCB encountered many difficulties dealing with the nanguan clubs, especially the three local ones in Lukang. Most of the difficulties lay in the issue of “which club to feature in a