行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

變遷中的台灣教育:當全球化遇到本土化

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 97-2420-H-004-026- 執 行 期 間 : 97 年 08 月 01 日至 99 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學教育學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 周祝瑛 計畫參與人員: 此計畫無其他參與人員 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 99 年 08 月 18 日

Globalization meets localization:

The Case of Taiwan Education

Chuing Prudence Chou

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER 1.

TAIWAN’S GEOGRAPHY, SOCIAL, CULTURAL, ECONOMIC,

AND POLITICAL SITUATION

CHAPTER 2.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TAIWAN’S (ROC)

EDUCATION

CHAPTER 3.

EDUCATION DURING LIBERATION/POST-COLONIAL

EDUCATION (1945-1987)

CHAPTER 4.

AGE OF EDUCATIONAL RESTRUCTURING (1987-1994)

CHAPTER 5.

EDUCATION REFORM ERA (FROM 1994 ONWARDS)

CHAPTER 6.

TAIWAN HIGHER EDUCATION AT THE CROSSROADS: ITS

IMPLICATION FOR CHINA

CHAPTER 7.

TAIWAN HIGHER EDUCATION AT THE CROSSROADS: ITS

IMPLICATION FOR CHINA

CHAPTER 8.

THE PUSH AND PULL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS IN

TAIWAN 65

CHAPTER 9.

CONTEMPORARY TRENDS IN EAST ASIAN HIGHER

EDUCATION:DISPOSITIONS OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

IN A TAIWAN UNIVERSITY 88

PREFACE

The intent of this book is to examine the processes of schooling in Taiwan amidst social, cultural, economic, and political conflict resulting from local and global dilemmas and issues. The book opens with an introductory chapter detailing the recent world-wide phenomenon in education, i.e. globalization and localization, followed by parts one through five to showcase the different perspectives of Taiwan’s education…. The book’s underlying thesis is that the mechanisms of localization and globalization both brings issues and dilemmas in Taiwan’s educational system. These phenomena also relate to the governance, financing, the provision of mass education, the issues in equity of educational opportunities, and the outcomes for differently situated social groups. They are also defined as common dilemmas endemic to school environments everywhere and represent global challenges of the twenty-first century that have in one way or another transformed the lives of almost everyone.

They are also defined as common dilemmas endemic to school environments everywhere and represent global challenges of the twenty-first century that have in one way or another transformed the lives of almost everyone.

Education system in Taiwan, similar to other education systems in East Asia, has undergone an enormous transformation over the last two decades. Education has become interconnected with trends of globalization and internationalization, development of information communications technology, and a set of political, sociological, economic, and management changes. These changes together produce multifaceted influences on education in Taiwan. In particular, the ideology of globalization and localization acts as one of the driving policy agenda in Taiwan. The notion of globalization encompasses a plethora of meanings. According to Mok and Lee (2000: 362), globalization is “the processes that are not only confined to an ever growing interconnectedness and interdependency among different countries in the economic sphere but also to tighter interactions and interconnections in social, political and cultural realms.” Governments in Taiwan have endeavored to follow the trend of globalization, especially in education.

CHAPTER 1. TAIWAN’S GEOGRAPHY, SOCIAL,

CULTURAL, ECONOMIC, AND POLITICAL SITUATION

INTRODUCTION OF TAIWAN

For centuries, Taiwan was referred to especially in the West as Formosa. At present it is officially recognized in Taiwan as the Republic of China, and in mainland China, as a renegade province of the People’s Republic of China. Despite this, it is universally renowned for its breathtaking natural scenery, and its miraculous economic development earned it the title of one of the four Asian Tigers. In the mid-16th century, when their ships passed through the Taiwan Straits, the Portuguese were amazed by the forest-cloaked island, and shouted out, “Ilha Formosa,” meaning “Beautiful Island.” This marked the first of many encounters between Taiwan and the West. According to the Chinese, Taiwan was called Yizhou or Liuqiu in ancient times, and different dynasties set up administrative bodies to exercise jurisdiction over Taiwan since the mid-12th century. The Dutch East India Company occupied Peng-Hu (an off-shore isle of Taiwan) as a trading harbor base for her East Asian business dealings in the 17th century. In 1622, a war broke out between China’s Ming Dynasty government and the Dutch troops. As a result, Taiwan was colonized by the Dutch from 1642 to 1662. After 1662, the Dutch were defeated by a former Ming government official, Zheng Chenggong, who used Taiwan as a military foundation against the Qing government. From 1662 to 1683, Taiwan was under the reign of Zheng’s family. In the Zheng family’s 23-year sovereignty, Taiwan once again underwent social reconstruction and economic development. It was known as the “Taiwanese Kingdom” or the “Kingdom of Formosa” by the English East India Company (National Institute for Compilation and Translation, 1997).

After 1683, Taiwan came under the control of the Qing Empire when Zheng was defeated by Chi-Lang, a Qing general. It was the first time that Taiwan was reclaimed officially by the Chinese government. In the mid-19th century, the European countries threatened China in the Opium War of 1840 which led to China’s loss of Hong Kong until 1997. Although the Qing government took a more positive attitude toward Taiwan’s development, Taiwan was ceded to Japan under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki after 1895, and remained under Japanese colonization for half a century.

Taiwan was returned to China after 1945 and once again after the defeat of Japan in World War II. Nevertheless, following the Chinese communist party takeover of

the Mainland in 1949, Taiwan became a shelter for Mainlanders who supported the Nationalist (Kuomingtang, aka KMT) leader Chiang Kai-Shek (Cooper, 2000). Nearly two million Chinese civilians, government officials, and military troops relocated from the mainland to Taiwan.

Over the next five decades (1949–2000), the ruling authorities gradually democratized and incorporated the local Taiwanese within the governing structure. In 2000, Taiwan underwent its first peaceful transfer of power from the Nationalists to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Throughout the period 1980–2005, the island prospered and became one of East Asia’s economic “Little Tigers.” The dominant political issues across the island remained the question of the eventual unification with mainland China, as well as domestic political and economic reform.

GEOGRAPHY, POPULATION, AND ECONOMY

Taiwan’s total land mass occupies 35,980 sq. km. The population growth rate was estimated at 0.63 percent in 2005, with a GNP of NT$463,056 (US$14,032) in 2004 (Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, ROC, 2004). According to J.F. Cooper (2000), Taiwan’s population is comprised of four cultural and ethnic groups. They are Taiwanese (Hokkien and Hakka) 84 percent, mainland Chinese 14 percent, aboriginal 2 percent. Each group has its own dialect and cultural perspectives. Taiwan used to adopt the doctrine “Three Principles of the People” invented by her founding father, Dr. Sun-Yat Sen in 1905. Since the 1990s, Taiwan has enjoyed a dynamic capitalist economy with a gradual decreasing in government control of investment and foreign trade. In keeping with this trend, some large government- owned banks and industrial firms have undergone incorporation and privatization. Generally speaking, exports have provided the primary impetus for Taiwan’s development. The trade surplus has been substantial up to 2004, and foreign reserves were among the world’s top 10 in the 1990s. Agriculture contributes less than 2 percent to the GDP nowadays, in contrast with 32 percent in 1952. Taiwan is also one of the major investors throughout Southeast Asia. In addition, Chinese mainland has already replaced the position formally held by the United States as Taiwan’s largest export market. Growing economic ties with the mainland since the1990s have led to the successful move of much of Taiwan’s assembly of parts and equipment for production of export goods to developed countries.

CHAPTER 2. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF

TAIWAN’S (ROC) EDUCATION

EDUCATION DURING CHINA TIMES (BEFORE 1626)

“Keju (Imperial Examination System) is a kind of examination system in ancient

times, through which officials were examined and selected. It was first adopted in the Sui Dynasty (581-618) and lasted through the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Intellectuals who wanted to be an official must take multi-tier examinations.

Formal imperial examinations consisted of three levels: provincial, metropolitan and final imperial examination.

The provincial examination was held triennially at the provincial city. Those admitted were called Juren (elevated men). The first place is called Jieyuan, the second, Yayuan.

The metropolitan examination was held in the following spring after the provincial examination at the Ministry of Rites in the capital. Those admitted were called Gongshi and the first place, Huiyuan.

The final imperial examination was under direct supervision of the emperor of the dynasty. Only Gongshi were qualified to take the exam. The matriculation had three levels of excellence. The first level was granted to three candidates, conferred Jinshi. The first three names set apart. The candidate ranking first was called Zhuangyuan (primus), the second, Bangyan, the third, Tanhua.

The second level was conferred the Jinshi status, the first place called Chuanlu. The third level was conferred the Jinshi status alike.”

(http://www1.chinaculture.org/library/2008-02/16/content_22184.htm)

SPANISH OCCUPATION (1626-1642)

In the early seventeenth century, Catholic Spain was in competition with Protestant Holland for trade in East Asia. With the establishment of a Dutch colony in the south of Taiwan, the Dutch effectively threatened Spanish trade in the region. As a

counter to this threat, the Spanish decided to establish their own colony in the north of the island (Wikipedia).

Other than economic reasons, Spain also wanted to influence East Asia in the religious aspect. At first, only soldiers can enter the aboriginal villages in Taiwan; it was not until the arrival of Father Jacinto Esquivel when missionaries gained the access into villages. In order to make his missionary work easier, he wrote two books on Taiwanese aboriginal languages and education, Vocabularino de la lengua de los Indios Tanchui en la Isla Hermosa and Doctrina cristiana en la lengua de los Indios Tanchui en la Isla Hermosa. He also founded a Brotherhood in Taiwan (Hermandad de la Santa Misericordia), and planned on establishing a seminary, which did not succeed (Wikipedia).

The Spanish territory and influence was limited at what are now Keelung, Danshui, and Yilan. The aboriginals mostly accepted Catholicism based on safety concerns, since Spanish soldiers are less likely to harass them if there are missionaries in the villages; the villagers may lose trust or kill missionaries if they visit an opposing village. Moreover, since Spanish missionaries believe that going to China and Japan is more important, they usually didn’t stay long in Taiwan, so the Spanish educational influence in Taiwan was not very significant (Wikipedia).

DUTCH OCCUPATION (1642-1662)

The Dutch East India Company occupied Peng-Hu (an off-shore isle of Taiwan) as a trading harbor base for her East Asian business dealings in the 17th century. In 1622, a war broke out between China’s Ming Dynasty government and the Dutch troops. As a result, Taiwan was colonized by the Dutch from 1642 to 1662.

One of the key pillars of the Dutch colonial era was conversion of the natives to Christianity. The missionaries were also responsible for setting up schools in the villages under Dutch control, teaching not only the religion of the colonists but also other skills such as reading and writing. Prior to Dutch arrival the native inhabitants did not use writing, and the missionaries created a number of romanization schemes for the various Formosan languages. (Wikipedia).

In order to make missionary work easier, the Dutch established the first school in southern Taiwan on May 26th, 1636. Other than religious contents, the curriculum includes reading and writing aboriginal languages in Latin (Zhen, 2004). The school had three categories of students: children, adult men, and women; only male students were able to receive lessons in reading and writing. Lessons were mostly carried out in aboriginal languages in order for the students to understand, but after 1648, schools started teaching Dutch, along with establishing traditional Dutch time tables and

requiring the aboriginals to have Dutch names and clothes.

The teachers include missionaries, soldiers, and aboriginals. In 1659, a seminary was established to train aboriginal teachers; there were only 30 openings and students had to pass an examination to gain entrance. The introduction of Roman letters was a significant change for Taiwanese aboriginals.

JAPANESE COLONIZATION (1895-1945)

Prior to the colonization of Japan, there were some forms of primary, secondary, and specialized schools for different purposes. Under the Japanese rule, a formal education system was established in 1919. Before then, the Japanese government issued the “Taiwanese Education Act” that divided the education system into four categories: general, vocational, specialized, and normal (teacher) education. At the general education or primary level, there were public schools, upper general schools, and girls’ high schools. All of these admitted children between the ages of 7 and 13. Students were to learn knowledge and skills for life and basic needs. However, it was only until 1943 when the six-year compulsory education was implemented. By that time, the enrollment rate for primary school level in Taiwan was 71.3 percent versus 99.6 percent for Japanese children (among the highest in Asia).

In 1922, the American “six-three-three-four” system was implemented in mainland China: six years in elementary school, three in junior high, three in senior high, and four in university.

CHAPTER 3. EDUCATION DURING

LIBERATION/POST-COLONIAL EDUCATION (1945-1987)

After World War II, when Taiwan was returned to China, an Act regarding compulsory primary education in Taiwan was issued in 1947. By 1968 compulsory education was extended to 9 years and by 1984, both the primary and secondary education enrollment rates had reached over 99 percent (Directorate- General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, ROC, 2005)

Since the 1950s, Taiwan encountered political and military uncertainty across the Straits, but between 1957 and 1980, the emphasis shifted to the planning and development of human resources in tandem with the national goal of economic development. Additional challenges to the education system came in response to the forces of economic liberalization and globalization which have transformed Taiwan since the 1980s.

Under the Japanese administration (1895–1945), the purpose of Taiwanese education was to assimilate local people into the Japanese culture. After 1949, the priority was changed to the strengthening of Chinese identity as a mean of preparation for the reassertion of sovereignty for China over Taiwan. During that period of time, indigenous Taiwanese cultures and languages were banned especially after the“228(February 28th) incident” in 1947 which involved the violent suppression of the KMT troops towards the Taiwanese people. Since the late 1980s, Taiwanese society has gone through a period of localization involving the renovation of Chinese identity with Taiwanese heritage and tradition. These trends of indigenization or the so-called localization actually stems from historical complaints against the KMT authoritarianism.

Education has been highly valued in Taiwan and a key item on the policy agenda of the ROC after the Kuomintang government's relocation from the mainland to Taiwan in 1949. The promulgation of educational legislation by the central government framed the foundation for the nation’s on-going educational development and achievement. For example, the nine-year compulsory education, which was first initiated in 1968, is a milestone in contemporary Taiwanese education history for its significant impact on the development of the nation’s human capital. All levels of education institutions have experienced dramatic growth in student and school numbers since the implementation of the Nine-year Compulsory Education program in the late 1960s. The Education Basic Law (the Law) came into force in 1999 to fully

protect people’s right to education, and entitled the Government to extend the period for compulsory education from the current nine years to twelve years. According to Yang (2001), the Law acts as the cornerstone of fundamental educational innovations in the millennium.

Since the 1980s, the economy of Taiwan has grown rapidly and the political stability in Taiwan has provided the Government with a safe ground to pursue democratization, pluralism and liberalization in every socio-cultural sphere (Yang 2001). The current education system therefore reflects the social, political, and economic status of Taiwan, moving towards a more comprehensive system in the field of education.

CHAPTER 4. AGE OF EDUCATIONAL

RESTRUCTURING (1987-1994)

During the political transition period of the 1990s, the former president Lee Teng Hui tried to incite a Taiwanese independence movement against China. Since then, education has focused extensively on local issues and Taiwanese identity such as the declaration of calls for the country to be known as Taiwan rather than the Republic of China, the shift of textbook content in elementary and secondary schools from Chinese to Taiwanese issues, and the increased proportion of “Taiwanized” national civil service examination questions. Taiwan’s educational system also entered an era of transition and reform as the nation’s industrial structure shifted from a labor-intensive to a capital and technology-intensive base, and political democratization intensified.

CHAPTER 5. EDUCATION REFORM ERA

(FROM 1994 ONWARDS)

The ‘controversial reform stage’ (1994 to date) has been characterized by numerous negative public opinions against educational reform programs. Chou (2003) and Hwang (2003) identify some of the problematic reform areas, including:

1. the presence of seven Ministers of Education between 1987 and 2003, which resulted in discontinuity and conflicts between various reform policies; 2. the lack of small-scale pilot or trial studies on reform practices;

3. lack of in-service teacher training;

4. miscommunication and misinformation among schools, parents, and the government; and

5. increasing gaps between the urban versus the rural, and the rich versus the poor have also aroused great concerns in the country.

Yang (2001, 15) also argues that some of these problems are rooted in ideological conflicts behind education reform measures, the imbalance between competition and social justice, and the tussle for power among the private sector, parents, schools and government. Other problems are connected to the lack of new norms to maintain educational excellence, the shortfall of educational budgets, the crisis of teacher professionalism, and the lack of recognition of the school as the center for change (Pan and Yu, 1999, 81-2).

In conclusion, education in Taiwan has been used as one of the most influential avenues for national building and economic development. Based on the influences of Japanese educational practices and ideals during the colonization period, Chinese culture and Confucian traditions from Mainland China, Taiwanese schools have experienced dramatic increases in enrollments. However, the pressure for credentialism and for examinations has remained constant through the 20th Century. Many educational innovations have been launched to deal with examination systems, curricular contents and instruction, and to reduce government ideological control. In doing so, teachers will have more flexibility for self-governance and autonomy to accelerate students’ creativity and thinking skills for the 21st Century. Nevertheless, the increasing discrepancies between income distribution and resources between urban and rural areas, the dilemma between the pursuit of education quality versus quantity, and the balance between localization and internationalization have created numerous challenges and foreseeable risks for the people of Taiwan.

What will happen to the next generation of Taiwan after a series of nation-wide education reforms? What are the follow-ups and outcomes? Who benefits and who suffers as a result of reform activities? These unanswered questions are not uncommon to for education systems in many countries around the world. As Taiwan actively participates in global events, how Taiwan learns from her education experiences in the reform era deserves more attention.

CHAPTER 6. TAIWAN HIGHER EDUCATION AT THE

CROSSROADS: ITS IMPLICATION FOR CHINA

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1980s, the education systems of Europe, and North and South America have faced a revolution, initiated by the adoption of neo-liberal free market economic policies and a consequent deregulation of education (Giroux, 2002; Dale, 2001). This has variously been realized through the restructuring and deregulation of public education, undertaken to increase the relative autonomy and responsibility of individual institutions, accountability and efficiency. Under these regimes institutions are expected to become more competitive, creating a competitive education market system. Under the impress of international agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) these neoliberal policies result in increasing private investment for education and supervising higher education institutions (HEIs) through the norms of more standardized and transparent accountability (Chou, 2005).

Under neo-liberal policies universities have shifted from norms of traditional state-control to those of state-supervision. Government’s role of initiating rules and regulations for HEIs now consists largely of specifying HEI funding standards. Market-oriented higher education is increasingly focused on issues of “competition” and “deregulation” including: developing performance-based funding schemes, increasing competition for faculty and student accountability, relocating social resources between HEIs, encouraging self-fundraising by universities, setting up more private institutions, and raising tuition fees. The policy sector holds that adopting market-oriented policies elevates the competitiveness of universities, induces cost-effective behaviour among HEI’s, and increases efficiency for better education quality. These actions, it is held, improve autonomy within universities, and in the long run, can increase student awareness of their rights as consumers of an educational product.

reforms since 1990s, as they have strong cultural similarities and are responding to common domestic and foreign trends in the region. Their attempts to upgrade the world-class universities in each country are also controversial, due to the perceived influence of a strong neo-liberal ideology.

HIGHER EDUCATION IN TAIWAN

After the lifting of martial law in 1987, higher education in Taiwan entered a stage of dramatic growth, part of a remarkable social and economic transformation. The number of universities and colleges expanded two- to three-fold over the past decade. Increasingly numbers of government supported students were viewed as a public sector burden. Successive governments introduced market-oriented reforms to relieve government budgetary pressures and grant the HEI’s greater autonomy. Inspired by Japanese education reforms in the 1980s, the Taiwanese government set up an Executive Yuan Educational Reform Committee (1994-96), amended The University Acts in 1994, revised them in 2005 based on deregulation, and pushed institutional administrative funds onto public universities (1996) to increase efficiency. These measures sought to introduce market dynamics into Taiwanese higher education.

HIGHER EDUCATION IN CHINA

China also underwent a dramatic change as a result of implementing a market economy and open-door policy in the early 1990s. To respond to the demands of rapid economic growth (averaging 8% GDP growth per annum over two decades) as well as international competition, Chinese higher education changes included: rapid expansion of enrolments, structural reforms, deregulation, privatization and quality improvement (Huang, 2005; Min, 2005).

Traditionally focusing on elite education, the Chinese government has shifted its attention to the improvement of education quality at the primary and secondary levels. Simultaneously massive restructuring of HEI’s took pace in an effort to increase shared responsibilities and relocate powers to the provincial and local levels. While funding from the Ministry of Education (MOE) and other central government agencies remains the main source of financing for universities and colleges, massive higher education enrolments in higher education and continued marketization have led to calls for more deregulation and social responsiveness within HEIs.

Taiwan’s institutional expansion

The revision of the University Act in 1994 transformed the traditional centralized system of bureaucratic control of the Ministry of Education into a more self-reliant and autonomous environment for HEIs. It also reduced MOE power and responsibility for university academic and administrative operations in presidential appointments, curriculum guidelines, student recruitment, staffing, and tuition policy, fulfilling the goal of academic freedom of autonomy (Tsai, 1996).

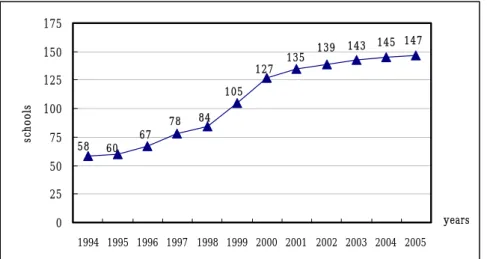

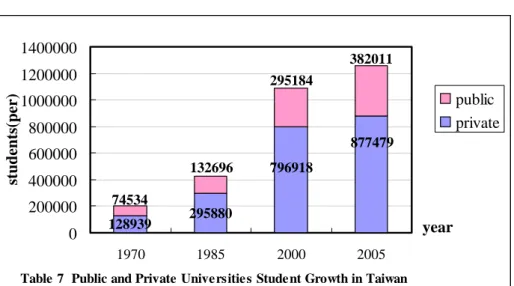

The number of Taiwanese universities and colleges HEIs has grown rapidly over the last decade from 58 in 1994 to 147 in 2005. (See Table 1)

Table 1 The Numbers of Universities in the year 1994-2005 in Taiwan Source: Bureau of Statistics, MOE (http://140.111.1.192/statistics)

58 60 67 78 84 105 127 135 139 143 145 147 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 years sc hool s

The ratio of public to private institutions at 1:1.94 (54:105) (MOE, 2006) indicates that HEI expansion is mainly due to increases in private institutions, which now accommodate more than 60% of the student population and charge twice as much for tuition than the public universities. In Taiwan, public institutions are regarded as more prestigious than their private counterparts. Most HEI expansion since the 1990’s, it has been argued, occurred largely by upgrading existing institutions (especially private, two-year and three-year vocational colleges), although other strategies, such as splitting, merging, and increasing the size of the existing institutions, also resulted in “new” institutions (Tsai and Shavit, 2003). Institutional expansion has been accompanied by dramatic growth in the net higher education enrolment rate among the 18-22 age cohorts, particularly among female students (who now constitute more than 45% of enrolees). University student enrolments have doubled since 1998 (See Table 2).

Table 2 The University Student Enrollm ent in Taiwan

Source: Bureau of Statistics M.O.E. (http://140.111.1.192/statistics/) 12595 12492 12216 11832 11078 9850 7934 5900 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 years st ude nt s( hundr ed )

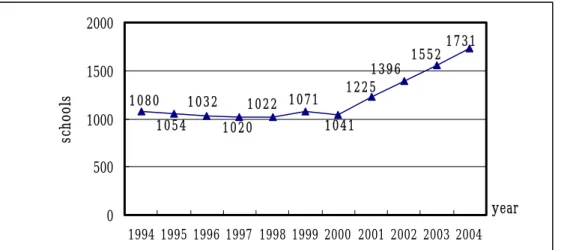

China’s institutional expansion

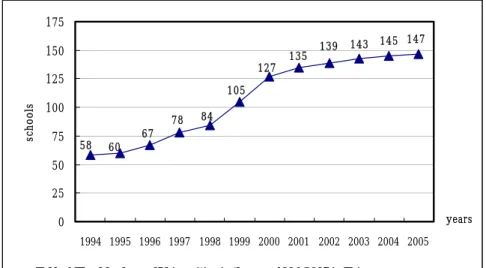

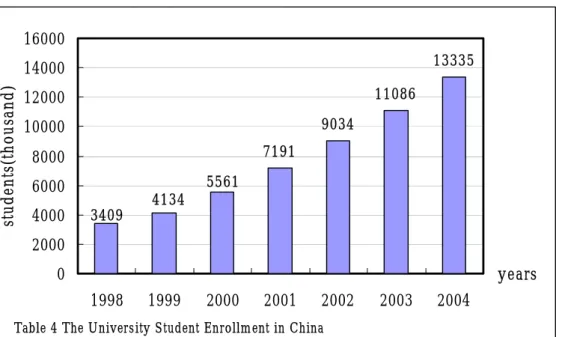

In 2004 China’s higher education system included more than 1,000 regular full-time universities and colleges, and almost the same amount of new private HEIs (See Table 3). Predominantly public HEIs receive about 12 million students and the newly established private universities enrol more than one million students (See Table 4). This paper focuses on regular full-time universities and colleges in China (Min, 2005).

Table 3 The Numbe rs of Unive rsitie s in the ye ar 1994-2004 in C hina Source : Nation Bure au of Statistics of C hina (http://www.stats.gov.cn/)

1 7 3 1 1 5 5 2 1 3 9 6 1 2 2 5 1 0 4 1 1 0 7 1 1 0 2 2 1 0 2 0 1 0 3 2 1 0 5 4 1 0 8 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 year sc ho ol s

As in Taiwan, Chinese higher education restructured and expanded during the 1990s. Before 1998, of over 1000 universities, 367 were governed by 62 ministries of the State Council. After a series of HEI mergers and, the MOE and some special government committees and departments now have authority to govern directly only

100 universities in the country; the rest have become the responsibility of local governments. Through the process of “restructuring, cooperation, and incorporation over the HEIs”, a total of 597 institutes merged into new universities. These actions represent some progress in responding to induced global de-regulation and accountability. (Fang & Fan, 2001).

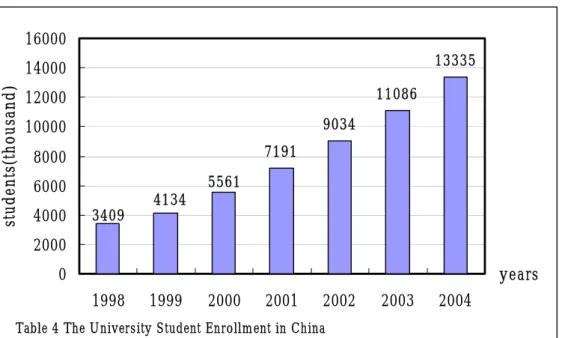

Student enrolment growth over the past decade has significantly altered the composition of Chinese higher education. The 1998 figure of eight million HE students (including full-time and part-time students) amounted to, less than 10% of the gross enrolment rate every year. After 1998 university enrolment increased up to 40% annually. By 2005, student enrolment in HEIs exceeded 23 million enrolments or 13 million full-time students, with the gross enrolment rate over 21%. This enrolment expansion resulted from actions by central government who instituted policies seeking to reduce the youth unemployment rate and encourage more educational consumption by expanding university capacity. (MOE of PRC, 2004). (See Table 4)

Table 4 The University Student Enrollm ent in China

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (http://www.stat s.gov.cn/)

7191 9034 11086 13335 3409 4134 5561 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 16000 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 years st u d en ts (t hous and)

II. Responding to Market Economies

Taiwan’s Responses

Seeking to install market mechanisms in the higher education environment, MOE and the Executive Yuan Education Reform Committee, formed in 1994, explored the employment of several market mechanisms within higher education, most urgently calling for deregulation. By granting HEIs more autonomy, the predominant government role changed from regulator to facilitator. Government no

longer intervenes with direct administration over public HEIs, instead supervising them through the University Act and other state laws. As frequently the case in the UK, Germany and Japan, government funding is no longer guaranteed and some actions toward incorporating public universities are under way. Following the Japanese Public University Incorporation Law in 2003, the Taiwanese MOE coincidently initiated a proposal to incorporate public universities. This act enabled some of the chosen and voluntary universities to transform into more independent, cost-effective and autonomous entities under the protection of law. Consequently, universities are expected to assume more financial responsibility and move toward a merit-based system in personnel decisions and calls for university accountability and efficiency are evident and stated repeatedly throughout government.

In 1999 the MOE in Taiwan initiated the “Project for Pursuing Excellence in Higher Education” in 1999, followed by the launch of a “White Paper Report on Higher Education in Taiwan” four years later. This paper sums up the latest developments of higher education in Taiwan and recommends a wide range of measures to achieve excellence in higher education, including the introduction of a university evaluation system, the establishment of a university financing committee, university merging and the increasing international exchange programs among faculty and students.

Taking university financing reform as an example, Taiwanese authorities proposed to change the ratio and method in funding, and encouraged public universities to search for alternate ways in raising revenue (Ministry of Education, 2006). Programs for continuing education, encouraging more cooperation with enterprises for sponsorships, setting up joint ventures on campus with outside business world all mushroomed within HEIs across the country (Dai, Mok, and Hsieh, 2002). The result is a very different campus culture in which faculty and administrators are driven to seek more resources with declining funding.

In addition, these government bodies sought to create greater heterogeneity among HEIs, suggesting that they should be differentiated respectively by their own characteristics, and mission. For example, faculty salary scales that might better be based on seniority are viewed as insufficient to promote the desired competition. To increase faculty competitiveness in HEIs, the committee suggested a more accountable reward system. The MOE also attempted to lessen its control over the establishment and enforcement of curriculum requirements, and has set up guidelines to allow for competing resources as well as financial subsidies based on merit and performance.

Although many critics remain sceptical of the picture that the Education Reform Committee (1994-96) and the White Paper Report portrayed (2003), most of the

policies recommended in the reports later became mandatory and were put into practice regardless of the initial resistance from HEIs. Universities and colleges now experience increasing pressure from the market and government in competing for resources, funding and student recruitment. Meritocracy, accountability and networking among faculty and staff carry more weight than before.

China’s Responses

Among all the major changes within Chinese HEIs in response to the worldwide market economies, structural reforms deserve close attention. A series of new educational policies has been launched over the years that reduce governmental involvement and increase the responsibilities to be exercised by universities in order to meet the needs of the society.

Higher education in China has historically been strongly administered by the central and provincial governments in the centrally-planned economic system prior to the 1990s. As a result, HEIs were immune to responding to any social changes or global competition and has long been criticized as “irrational, irrelevant, and segmented.” (Fang & Fan, 2001) Therefore, the structural reform and adjustment of the higher education system became one of the top priorities including a release of Higher Education Act in 1998 .This act detailed a two-level education provision system with an attempt to differentiate responsibilities between different levels of governments, and university’s responsibilities in resource generation, funding allocation, and student recruitment. (Dai, Mok, and Hsieh, 2002). Specific reform programs were implemented such as change of the government/university relationship (Huang, 2005; Min, 2005), and institutional mergers. One example being the emergence of the new Zhejiang University from five neighbourhood universities later to become one of the leading comprehensive universities in China.

Moreover, university curriculum reform has come under revision. Universities have been criticized for providing overspecialized and fragmented knowledge which prevented students from embracing well-rounded development and practical knowledge for the job market. In response to this problem, curriculum reforms that took place across Chinese universities after the late 1980s introduced interdisciplinary studies, general education, and many more market-oriented programs along with reforming teaching and learning process. Universities are also undergoing a series of re-organization among different programs, disciplines, departments, and even administrative offices.

In addition, a new University finance reform was underway. In the past, Chinese HEIs were public-funded and charged no tuition for students who later received government jobs. University faculty, as public officials, received humble salaries

based on seniority rather than performance, and HEIs could admit only a limited number of elite students through a highly competitive college entrance examination. As Chinese higher education enrolments expanded rapidly over the past decades, the publicly-funded system was forced to reconstruct due to its financial constraints (Min, 2005.11.10). A cost-sharing and cost-recovery system among central and local governments and the universities was adopted to reduce the former public funding model. Universities began to charge tuition and fees around the mid-1990s. At present, more than one-fifth of the total operational budgets of HEIs are covered by tuition and fees.

In addition, universities now can generate their own revenue by issuing patents, copyrights and contracts with industry, conducting business consultation, offering in-service training programs, and launching fund-raising activities. Leading universities like Peking and Tsinghua University also generate revenues by setting-up university-affiliated high-tech companies in China. In the year 2000, of the total expenditures of Chinese higher education, 57% came from state appropriations, 22% from tuition and fees, and the remaining 21% from revenue generated by the universities themselves (Min, 2005).

In addition, a salary-scale renovation was introduced detailing different formulas for job performance among faculty members to recognize their merit rather than seniority. Research and publication is highly encouraged, as well, and integrated into salaries at leading Chinese universities.

Another major reform in China over the last decade has been the re-establishment of private higher education (so-called minban or non-state-run higher education). In an attempt to combat the enrolment shortage of public institutions, the Chinese government implemented policies deregulating the private sectors to increase university enrolment rates from 3% to 14% of the college age cohort by 2002. Although most of the private HEIs remained as short-term and vocational-oriented programs, some of them later developed into comprehensive and competitive HEIs. Currently, there are over 1,200 private universities and, enrolling over one million students. However, only about 5 % of these institutions have been officially accredited by the government to grant university diplomas. A new law regarding the legal status and management of private education was issued and implemented for the first time in 2003, recognizing the contribution of private sectors and the return rate permitted to be granted to the investors.

Finally, a major reform needing mention is the abolishment of the governmental job assignment policy among college graduates in the mid-1990s. Like their counterparts in most countries, Chinese university graduates currently enter a competitive job market with qualifications rather than depending on governmental

arrangement. As market economies develop, a university education is expected to be more responsive and relevant to social needs and the job market. Programs and courses have been revised based mostly on practical and market values, instead of theoretical and pure-science subjects. Programs such as economics, finance, law, industrial/commercial management, foreign languages, computer and applied technology have been more popular. Consequently, students in China now pay more attention to their future job market prospects and career development than their own interests and academic potentials (Dai, Mok, and Hsieh, 2002).

III. Specific Actions toward more competitive universities

Taiwan’s initiatives

The introduction of market mechanisms into universities means the transformation of higher education from a public good to a private commodity. In its efforts to decrease government control and integrate social demands with market forces, Taiwanese higher education since the 1990s has been significantly influenced by neo-liberalism thought and policy.

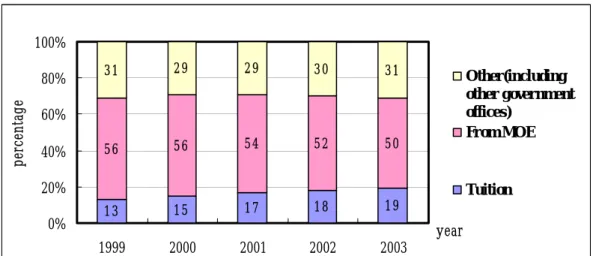

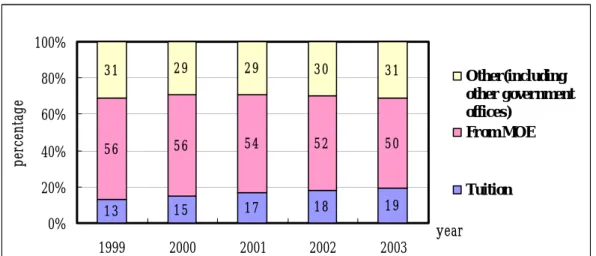

As a result of the introduction of free-market economy principles and neo-liberalism policies in 1990s, the proportion of financial support from the MOE has decreased 23% in the last decade, whereas the proportion of tuition income has increased 6% (Sun, 2006.12.12). Accordingly, an “administrative funding scheme” was introduced into public universities to improve their accountability. No longer relying on government budgets alone, public (or so-called “national”) universities are required to designate partial funds for sharing their daily administrative costs. Nevertheless, the MOE and other government budgeting offices still have the right to regulate various university practices. A trial program based on these principles within five universities was introduced by the central government in 1996. Now 55 out of 70 public universities participate in this new program, allowing more autonomy in

Table 5 Source of Administrative Fund for Public Universities in Taiwan 1 3 1 5 1 7 1 8 1 9 5 6 5 6 5 4 5 2 5 0 3 1 2 9 2 9 3 0 3 1 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 year p er cen tag e Other(including other government offices) From MOE Tuition

In order to become more financially self-sufficient, leading universities undertook an unprecedented fund-raising campaign, gathering donations from their alumni, the general public, and business. However, many institutions have been less than successful in obtaining significant support from these sources. HEIs such as new public universities lack strong networks with their newly-graduated alumni.

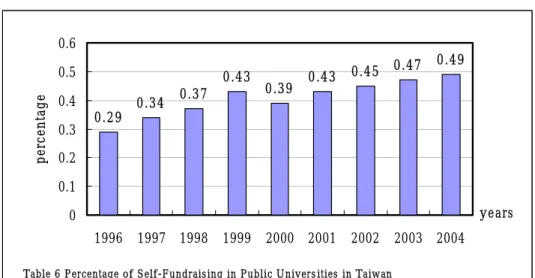

Teachers’ Colleges (now re-classified as education universities) suffered from a shortage of strong alumni donations. Above all, the Taiwanese general public is not used to donating money to universities (public institutes especially) because the latter have been regarded as a public good, funded solely by the government. Therefore, a huge discrepancy in fundraising arose between the well-established HEIs (especially those with a comprehensive and science/engineering background) and the less prestigious/small-scale universities. Higher education quality skewed drastically according to different institutes (See Table 6).

Table 6 Percentage of Self-Fundraising in Public Univers ities in Taiwan 0.29 0.34 0.37 0.43 0.39 0.43 0.45 0.47 0.49 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 years pe rc en ta ge

In another attempt to provide universities with more incentives for pursuing excellence and to offset declining quality due to rapid expansion and public budget cuts, the MOE promoted a “World Class Research University Project” in 2003. This proposal aimed to upgrade at least one of the HEIs in Taiwan to rank among the world’s top 100 universities based on international journals within the next ten years. Consequently, a “Five-year, Fifty Billion Budget” plan (est. 1.6 billion USD) was launched among several selected prestigious public and private HEIs in early 2006 to improve fundamental development, integrate human resources from different departments, disciplines and universities, and establish research centers to pioneer specialized interests. In addition, universities now are required to establish an internal and external evaluation system using various indicators such as the Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), and the Engineering Index (EI) etc., in accordance with standards that meet international recognition for awards, achievements, and contributions within their field of expertise. A non-governmental organization (NGO), The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan , was established in December, 2005 to conduct external evaluations across universities on a regular basis (Chang, 2005.12.26).

Chinese initiatives

The Chinese government has launched similar projects in an attempt to enhance international competitiveness among universities. To achieve the goal of “100 leading universities, research centers, and disciplines across China in the 21st century”, the Chinese government started its “211 Project” in 1995. The project’s main emphasis is to develop a group of HEIs that will compete to enter the ranks of the top world-class universities (MOE of PRC, 2004). The project will choose 100 universities from applications from across the country. In order to develop criteria and data to assist in selecting these 100 HEIs, the government started an evaluation process based on measurements of faculty quality and productivity, facilities, libraries, laboratories, research quality, university resources and many more criteria. Consequently, Chinese HEIs began a series of institutional mergers. After five years of this merger experience, many newly-established universities are developing the basis upon which to be highly competitive in acquiring national prestige. One example, previously mentioned, is Zhejiang University which now ranks among the top five universities as a result of a merger with local HEIs and funding by many of the aforementioned projects.

Subsequent to “Project 211”, another, labelled “Project 985”, was developed in an attempt to push Chinese higher education to a new level. The idea originated from a speech by the former General Secretary of China, Jiang Zemin who attended the

100th Anniversary of Beijing University in May 4, 1998, and proclaimed that “China must have a number of first-rate universities of international advanced level” (Hayhoe & Pan, 2005). Consequently, the MOE of China has signed agreements with nine top HEIs in China such as Peking University, Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University, hoping to upgrade Chinese universities to the standards of Harvard University, London University, Tokyo University and the like. With full financial support from the central and local governments, these nine institutions are expected to blossom over the next few years. Top funding priority was given to Peking University and Tsinghua University, ranked as 14 and 28 respectively among the world’s top leading universities according to the Times’ Higher Education Supplement (World University Rankings, 2006). It is also expected that these leading universities will be able to serve as examples to improve Chinese higher education.

In another effort to upgrade their overall quality and reputation, many Chinese universities have established exchange programs with international universities intended to broaden the horizons of faculty and students. It is also considered an “asset” to increase student enrolments in the university. Universities which go for international exchange programs are concentrated in areas like Peking, Shanghai, Tianjin, and other metropolitan and coastal cities in China that are more accessible to the outside world. It is estimated that approximately a half million students and scholars have gone to study abroad in the past 20 years, as more international academic exchange programs and joint research programs have been set up both domestically and abroad. As China continues its open-door policy, more internationally-oriented programs, such as international studies and foreign languages, have become very popular on university campuses. At the same time, more international exchanges and collaboration between Chinese students/scholars and international counterparts are taking place.

IV. Challenges and Comparisons

Taiwan’s dilemma

The road to reform in higher education in Taiwan and China as well as their related pursuit to achieve world class standards has revealed significant challenges that both countries must confront and overcome to achieve these goals. For example, the introduction of market economies in the early 1990s, followed by deregulation of government control over the new HEI establishment, has resulted in an unprecedented expansion of higher education in Taiwan. More HEIs now compete for less and less resources and public funding. Mixed results have occurred in terms of educational quality, efficiency and equity. Universities are more accessible to younger generations

than before, but the increasing tuition and declining educational quality, coupled with the drastic decline of fertility rate in Taiwan has aroused another concern about the over-supply of university graduates in the job market.

Challenges on these issues are as follows (Blumenstyk, 2001, 2002; Chou, 2005; Giroux, 2002; Slaughter, 2001):

• The new changing role of university from being highly regarded to the concept of “user pays” rules has forced many HEIs to tailor their programs and coursework according to perceived market needs. Students tend to take courses with “practical outcomes”, rather than for personal fulfilment. Teaching faculties are viewed as academic entrepreneurs, treating professional knowledge as a matter of business, rather than engaging in academic pursuit for truth and discovery. Owing to the massive expansion of HEIs and consequent shrinking public budget in the past decade, universities now need to compete for external funding opportunities from the business world. Trade-offs are the possible external corporate intervention with university operations, curriculum design, and personnel appointments. • In addition, the increase in public and private HEI tuition has become a heavy

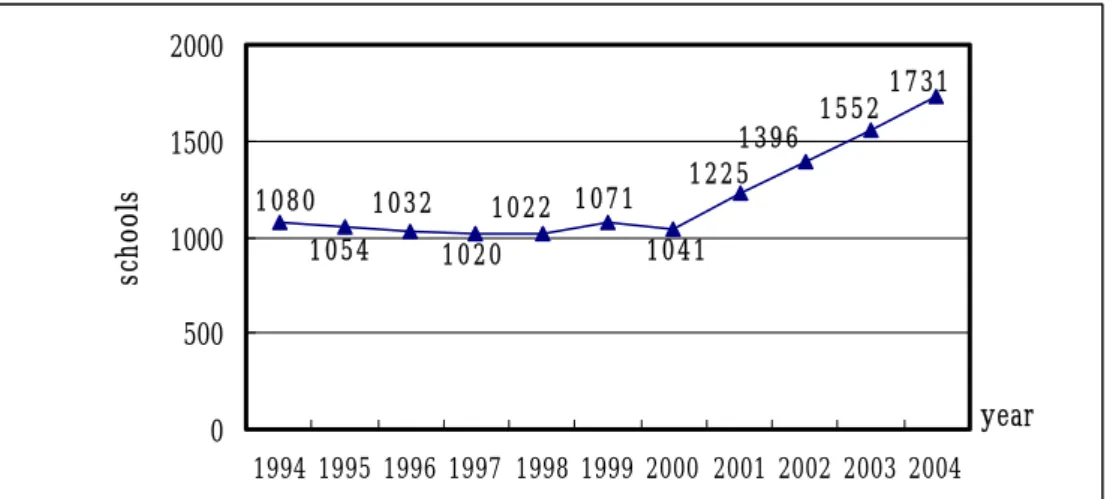

burden for many students across Taiwan. From 1997 to 2006, tuition at public universities has increased approximately 42%, while private universities have experienced a 14% increase (on an already high cost base). The average salary has increased only about 8%. Taiwanese families (GDP=13,500 USD in 2005) have to bear such high costs, especially for students who attend private institutions. The latter make up about 66% of the total universities and colleges in Taiwan (See Table 7).

Table 7 Public and Private Universities Student Growth in Taiwan Source: Bureau of Statistics, MOE (http://140.111.1.192/statistics)

128939 295880 796918 877479 382011 295184 132696 74534 0 200000 400000 600000 800000 1000000 1200000 1400000 1970 1985 2000 2005 year students(per) public private

In sum, Taiwanese higher education has undergone a drastic change with the introduction of a market economy ideology, the expansion of HEIs, and public

financial constraints since early 1990s. Taiwan’s access to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002 has created a more competitive international environment in which the educational sector is regarded as a trade service without national boundary. With limited education resources and an over-supply of college graduates with diverse qualifications, higher education institutes encounter an uphill challenge and competition within both domestic and international arenas. More university restructuring efforts will take place through institutional expansion, mergers, and evaluation, based more on market considerations than on social equity concerns.

China’s challenge

Since the mid-1980s, China, as a former socialist country, has undergone a variety of changes in the political, economic, and other social domains. In particular, the adoption of market economies along with the open door policy became the major force in Chinese higher education reform (Ngok & Kwong, 2003). For example, privatization (sometimes appearing in different forms) in China as part of the reform agenda has been encouraged with the following characteristics: private economic activities receive more support within a climate of increasing deregulation; activities and wages from the public sector have been cut substantially; and more policies aiming for export growth and industrial development have taken away from state responsibility for social welfare in public health, transport, communications and education in particular (Mok & Welch, 2003).

As a result, these economic and political changes shifted the academic climate completely. Higher education reforms since the 1990s have helped to relinquish state governance and responsibilities previously held by the central and local governments. Universities assumed more responsibility and accountability for their daily operation, while government monitored succession planning, overall structural development, and resource allocation. Mixed results of such deregulation and privatisation policies have emerged with the increase of campus autonomy and financial freedom, especially from those leading HEIs. For example, many university faculty members now have the opportunity to seek additional income from other resources to compensate their relatively low salary. A survey indicated that a common phenomenon arose after China’s economic development in the 1990s. University faculty, especially those from coastal and leading institutes, have been driven by market forces to concern themselves with activities other than teaching and research. Many professors now take part in projects or provide training services for private institutes or companies, generating more external revenues for their institutes and themselves.

Another issue deserving consideration is that as China’s economic growth continues, leading HEIs have been provided with increased funding for facilities and basic infrastructures. Because these universities have traditionally had the privilege of obtaining additional funding from governments, many of them have had enormous investments in their physical plant, bringing them to world-class level. These HEIs have benefited from the special government funding policy by over-investing in their building construction and material realms, neglecting their internal substance. This phenomenon marks the paradox of a Chinese university, rich in hardware and material range, but poor in software and academic scope, a climate that parallels the improvement of institutional autonomy and freedom. Nevertheless, the Chinese government has recognized this problem and begun to reform the university reward and funding system with salary and promotion scales, providing greater initiatives for institutional accountability and personal growth in research publication and job performance. As a result, Peking University was chosen to rank among the top 100 world-class universities in October, 2006, by the Times Higher Education Supplement from London. This recognition has rewarded Chinese endeavours in upgrading their universities over the last decade, although scrutiny remains about the validity and credibility of university rankings (Ho, 2006).

After China’ s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, an increasing demand for globalizing higher education, such as cross-cultural interactions and exchanges of students and faculty members, has resulted in an even greater pressure on the irreversible internationalizing trend in Chinese higher education (Min, 2005). In an era of rapid advancements in science and technology, Chinese universities have been called on to play a central role in knowledge-based economic development.

Comparison

Taiwan and China, though distinct in political, social and economic background, are following the global trend of reforming higher education in market-oriented directions. In comparing the distinctive features in higher education between these two societies after the 1990s, the former aims for deregulation and diversity within the system, competition to gain management efficiency, and integrating societal needs as a way of responding to the market economy. As for China, especially after 1992, the major concern has been to pursue economic efficiency and prosperity rather than ascribe to social equity norms that had once been so strongly articulated in China. The following discussion will highlight some of the comparative issues between Taiwan and China (See Figure 1 ).

Reform policy Taiwan China

Reform features

--- Reform origin

--- Policy package for Funding and promotion as reform incentive .deregulation, efficiency and diversity resource polarization between universities

and areas. Political democratization after

the lift of Martial Law in 1987

.Bottom-up movement and social pressure for change

.The Award for university teaching excellence in 2000 .World-class research

university project in 2005 (5 year, 50 billion NT Plan) .SSCI, SCI, EI Journal article

phenomenon

. efficiency and prosperity .less concerned with social equity .discrepancy between inland and

coastal areas, poor and rich

.Economic open-door policy after early 1990s

.Government top-down policy

.211 Project in 1995 .985 World-class University

Project in 1998 .SSCI, SCI, EI Journal article

phenomenon

Reform policy Taiwan China

Reform features

--- Reform origin

--- Policy package for Funding and

.deregulation, efficiency and diversity

resource polarization between universities

and areas. Political democratization after

the lift of Martial Law in 1987

.Bottom-up movement and social pressure for change

.The Award for university teaching excellence in 2000 .World-class research

university project in 2005 (5 year, 50 billion NT Plan)

. efficiency and prosperity .less concerned with social equity .discrepancy between inland and

coastal areas, poor and rich

.Economic open-door policy after early 1990s

.Government top-down policy

.211 Project in 1995 .985 World-class University

Project in 1998 .SSCI, SCI, EI Journal article

Figure 1 Comparison between Taiwan and China

1. Origin of higher education reform

Changes in Taiwanese higher education have taken place in the context of political democratization, the lift of Martial Law in 1987, and a process of economic restructuring from a labour-intensive to a science and technology industry in the early 1990s. Higher education was in demand for its capability to provide modern citizens with creativity as well as to meet the need for new manpower. On the other hand, Chinese higher education reform originated from the open-door policy and the introduction of a market economy after the early 1990s (Huang, 2005). As the Chinese economy expanded (an average annual GDP growth rate of 8% for the past two decades), the high demand for economic reforms and an open-door policy have helped the Chinese economy to become more integrated into the international economy. Consequently, Chinese higher education has been marked for major change to improve national development and manpower,.

Specifically, differences between the two nations under the market economies date from Taiwan’s lifting of political martial law in 1987, a change that created a social environment for education innovation and openness. Government as well as the general public took complementary roles in developing initiatives for higher education reform. Comparably, China started her reforms following open-market economy policies in the beginning of the early 1980s and accelerated its reform scale in the mid-1990s as the economy developed. Nevertheless, the leading authority of higher education in the aspect of policy and resource in both countries is still confined to the government, although public opinion counts more heavily in Taiwan due to political democratization since the late 1980s.

2. Reforms linked with funding and promotion scales

Unlike China’s rapid economic growth during the past two decades, Taiwan’s economic growth has remained relatively stable in the past few years. This economic reality together with the expansion of HEIs in Taiwan, has placed an enormous

promotion as reform incentive

.SSCI, SCI, EI Journal article phenomenon

financial burden on both public and private institutions, and shifted the focus and culture of the profession. For example, in order to enforce a competitive mechanism for institutional and individual funding, the government sets up evaluation criteria based on quantitative indicators and require HEIs and faculty to comply. One key element for accountability depends on the number of journal articles published in the SSCI, SCI and EI databases. This western-dominant evaluation standard has created tremendous pressure on university faculty who now seek more short-term research outcomes as a means to fulfil the criteria for public funding and the self-evaluation process. A series of standardized evaluation systems have been introduced in both nations combining funding and salary scales. The over-emphasis of publication quantity rather than quality, journal articles rather than books, and research over teaching, has driven HEIs to fall into a quasi-corporate world full of external insensitivities and competition rather than an educational entity.

In addition, the bid to raise external revenue coupled with continuing evaluation demands at personal as well as institutional levels has transformed Taiwanese HEIs into market-driven entities. The emerging trend for university faculty to act as academic entrepreneurs at the expense of their role as public intellectuals seems unstoppable. The hope that education reform will facilitate academic autonomy and serve the public seems less and less attainable in an era of academic capitalism.

3. Over-emphasis on pursuing -“World Class Universities” policies

In order to align with international competition and the revolution in information science and technology, universities today are expected to gear towards knowledge-based institutions (Castells, 1991). Taiwanese and Chinese governments have, therefore, initiated policies not only to expand higher education enrolments but also to upgrade some leading national universities to world-class status. These attempts include the ‘World Class Research University’ project in Taiwan and the ‘211 Project’ and ‘985 World-Class University Project’ in China -- have created mixed results. Because public funding has only been allocated to selected universities, the increasing disparity of educational quality has accelerated between public and private, and leading and regular HEIs. It is clear that the new higher education framework in both countries has been prioritized more on accountability and market competition in quantitative terms than on social equity and equality values. These “world-class universities policies” have been characterized as duplicating Western and American university models whose “cultural imperialism” and “cultural reproduction” will, in the long run, impair both societies’ cultural identity and heritage (Hayhoe, 1989; Ho, 2006).

V. Conclusion

As discussed above, higher education reform after the early 1990s in Taiwan and China has followed a similar transitional pattern along with the global expansion of neo-liberalism ideology. Reform policies took various forms, such as deregulation of government control, privatization of public services, introduction of accountability and competition, increasing shared governance and funding resources between the state and HEIs, and implementing more external evaluation schemes to monitor reform outcomes. As a result, college enrolments expanded, university system were restructured, curriculum and instruction were revised, and competition for resources was emphasized over collegial collaboration. In addition, as many national universities have aimed to become world-class institutions, government policy earmarks special funds to implement higher education upgrading plans. In the long run, some leading HEIs in both countries have benefited and made significant progress, especially in physical infrastructure improvement and the publication of more international journal articles. However, quality and equity issues, in-depth discussion and follow-up reflection tend to be neglected under this broad umbrella of global market ideology.

Furthermore, higher education was formerly highly centralized and administered by the government in both counties until the political open-up in Taiwan during late 1980s and the economic restructuring in China in early 1990s. University reforms in both societies generally followed government policies and directions. As the call for democracy and deregulation rose among people in many developing countries since 1980s, reforms in political powers including educational sectors began to take in place. In Taiwan, the origin of reform began with public demands for social democratization in the early 1990s. Government officials responded by launching reform policy under the recommendation of neo-liberals in government and academe. Overall, the most essential issue in higher education began with the call for decentralization and deregulation of the public institutions in the name of institutional autonomy and academic freedom protected by the constitution. Since the early 1990s, the general public has anticipated a power withdrawal from the government to allow universities to have more autonomy, efficiency and flexibility in decision-making and daily operation. As years pass, universities now enjoy more freedom than before, but are now facing immediate challenges in fund-raising and public demands for accountability.

Higher education reforms in China started as part of the governmental re-structuring process after its economic open-door policy in the early 1990s. Chinese universities have been geared more toward the managerial domain, after re-adjusting relationships between government, society and HEIs. A new shared-responsibility

policy between central and local authorities came into practice in recent years by promoting more burden-sharing and social responsiveness. Market forces have had impacts across university campuses where curriculum, instruction, research, staffing, tuition plans, and many other campus features are expected to be revised on a large scale to empower HEIs to meet market needs.

In spite of this transformation process of neo-liberal policies over the last decade, universities and colleges in both countries are still regulated by the central government in terms of law-making, policy decisions, resource allocation, and execution monitoring. Government maintains its authority in a macro-perspective, while also undergoing a large-scale national restructuring and downsizing process. As the public funding continues to withdraw in accordance with the market formula, universities in Taiwan and China have enjoyed a greater autonomy in decision-making and daily operation levels, with the expectation they become more innovative, creative, and efficient in the long run. Universities are more responsive to societal and student needs as they must meet fundraising agendas dependent on alumni and external sources to offset their public financing deficits. The structure of higher education has been undergoing a series of reforms in order that the system be more adaptive to new social and economic demands.

Overall, higher education reform under market economies has received mixed results in both countries. University education is still considered as a public good rhetorically, but in reality the increasing education costs have put the poor in a more difficult situation and more people have been forced to accept the concept of “user pays”. This is especially the case in Taiwan where universities are more socially relevant and responsive in terms of adapting their education programs and services to the public needs, or even opening up their facilities to the society on a rental-basis. However, the gap between the poor and rich, and the rural and urban areas has been accelerating, along with greater educational opportunity. Regional discrepancies as well as institutional polarization in education provision between public and private, and leading and regular HEIs have created new agendas for universities to strive for a balance between social equity and economic efficiency in Taiwan and China. The issue merits more attention after both countries joined the WTO and began interacting with more international colleagues and competitors (Chen, 2002.10.17). Thus, their university systems inevitably need to re-adjust into a more flexible form and yet maintain their own educational quality to satisfy individual needs while fulfilling their public mission. Above all, maintaining a traditional heritage and self-identity in both countries despite an overemphasis on the pursuit of a western-dominant, world-class university will be no doubt the imminent challenge of the century.

In sum, both Taiwan and China have attempted to restructure their power over HEIs, nevertheless universities still depend on public funding and, therefore, are prone to comply with public policy requirements regardless of academic autonomy and institutional freedom. Issues such as educational quality versus quality, and efficiency versus equity have been overshadowed by market economies during the last decade in both Taiwan and China.

REFERENCE

Blumenstyk, G. (2002). Chasing the Rainbow: A Venture Capitalist on the Trail of University –Based Companies. Chronicle of Higher Education, March 15, 2002. Blumenstyk, G. (2001). Knowledge Is a Form of Venture Capital for a Top Columbia

Administrator. Chronicle of Higher Education, February 8, 2001.

Chang, Jih-yu (2005.12.26) Focus news: Welcoming the new era of higher education,

accessed on January 4, 2007 from

http://epaper.edu.tw/news/941226/941226a.htm

Castells, Manuel. (1991, June 30). University system: Engine of development in the new world economy. Paper presented at the Worldwide Policy Seminar on Higher Education Development in Developing Countries, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Chen, Zhili. (2002.10. 17). Historical accomplishments in education reform and development. China Education Daily, Beijing, China.

Chou, C. P. (2005). Neoliberalism and higher education – Cases on New Zealand, Argentina, and the United States. Unpublished report.

Dai, X. X., Mok, K. H. & Xie, A. B. (2002). The Marketization of Higher Education: A Comparative Study of Taiwan, Hong Kong and China. Taipei: Higher Education Publishing.

Dale, R. (2001). Constructing a long spoon for comparative education: Charting the career of the New Zealand Model. Comparative Education, 37,4,493-501

Fang, H.J. & Fan, D. (2001) Reform and development of Higher Education. Beijing: Tsing-Hua University Publishing.

Giroux, Henry A. (2002). Neo-liberalism, Corporate Culture, and the Promise of Higher Education: The University as a Democratic Public Sphere. Harvard Educational Review, 72, 4.

Hayhoe, R. (1989). China’s universities and western university models. In P. G. Philip & V Selvaratnam (Eds.), From dependence to autonomy: The development of Asian universities. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Hayhoe, R., & Pan, J. (2005). China’s universities on the global stage: Perspectives of university leaders. Accessed on January 4, 2007 from