ASSESSING THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGIOUS

PREDISPOSITIONS ON CITIZEN VALUES RELATED

TO GOVERNANCE AND DEMOCRACY: FINDINGS

FROM SURVEY RESEARCH IN THREE DISSIMILAR

ARAB SOCIETIES

by

Mark Tessler

University of Michigan

An earlier version of this paper, coauthored by Eleanor Gao, was presented at the 2005 annual meeting of the International Studies Association. These findings are also being incorporated into a more comprehensive paper that Tessler and Gao are preparing for publication.

ASSESSING THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGIOUS PREDISPOSITIONS ON CITIZEN VALUES RELATED TO GOVERNANCE AND DEMOCRACY: FINDINGS FROM

SURVEY RESEARCH IN THREE DISSIMILAR ARAB SOCIETIES

Mark Tessler University of Michigan

Studies of democracy and democratic transitions place emphasis on the attitudes, values, and behavior patterns of ordinary citizens. More specifically, this research argues that successful democratization requires the existence of a “democratic” political culture orientation among a significant proportion of a country’s population. Some analysts suggest that this is a

precondition for a democratic transition (Huntington 1993, 13). More common is the view that democratic norms and behavior need not precede, but can rather follow, an elite-led transition involving the reform of political institutions and procedures (Rose 1997, 98; Schmitter and Karl 1993, 47). Indeed, according to this argument, citizen orientations conducive to democracy may emerge in response to the experience of a democratic transition.

Debates about timing and sequence notwithstanding, there is general agreement that sustainable democracy depends not only on the commitments and actions of political elites but also on the political culture orientations of ordinary men and women. This thesis was advanced more than four decades ago by Almond and Verba in their seminal work, The Civic Culture. They observed in 1963 that “if the democratic model…is to develop in new nations, it will require more than the formal institutions of democracy – universal suffrage, the political party, the elective legislature…. A democratic form of participatory political system requires as well a political culture consistent with it… [of which] the norms and attitudes of ordinary citizens are

subtler cultural components” (1963, 3; also Almond 1980, 27). Inglehart is among the many scholars of democratization who have made the same point more recently. He wrote in 2000 that “democracy is not attained simply by making institutional changes or through elite level

maneuvering. Its survival depends also on the values and beliefs of ordinary citizens” (2000, 96) Against this background, it is important to investigate the factors that either encourage or discourage the emergence of democratic attitudes and values, and in Arab and other Muslim societies the influence of Islam is of particular interest. Although some scholars suggest that Islam is hostile to democratic values (Kedourie 1994), 5-6; Lewis 1994, 54-56; Huntington 1991, Chapter 6), empirical research at the individual level of analysis finds no evidence that religiosity and Islamic involvement diminish support for democracy (Tessler 2002; Tessler 2003; Mujani 2004). The relationship between religious orientations and a democratic political culture has not been investigated, however, and the present study seeks to fill this gap by examining the

relationship between religious orientations and democratic values among Muslims in Jordan, Palestine (West Bank and Gaza), and Algeria.

Data and Method

Data from national surveys carried out in Jordan, Palestine (West Bank and Gaza), and Algeria in 2003-2004 are used to examine the political culture orientations of ordinary citizens in these three Arab countries. Surveys were conducted in Jordan and Palestine in December 2003 and in Algeria in summer 2004. These three countries were chosen for both practical and analytical reasons. Practical reasons include the availability of local scholars and institutions with substantial experience in the conduct of rigorous survey research and, as reflected in Freedom House ratings of “Partly Free,” a political climate that permits the conduct of public

opinion research. Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria are among the relatively few Arab countries where political attitude research is possible at the present time.

Analytical considerations include system-level differences that make cross-national comparison instructive. Within the context of the Arab world, the three countries constitute something of a “most different system” research design. Although none of them resembles the small, oil-rich countries of the Arab Gulf, they are otherwise at least somewhat representative of the region’s republics, monarchies, and strong presidential systems. Any patterns observed in all three countries may thus be generalizable to other parts of the Arab world. It is also possible that patterns common to Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria will be applicable to non-democracies in other world regions, since they will have been found to obtain under widely differing conditions. Alternatively, the unique attributes and circumstances of each country will help to define in conceptual terms the locus of applicability of patterns found only in that country.

Algeria, a republic, is one of the largest states in the Arab world, has considerable wealth from oil and natural gas, and possesses a tradition of state socialism and centralized planning. For much of the time since its independence in 1962, Algeria has been governed by a cohort of military and civilian leaders, with military officers having preponderant influence. Jordan, a monarchy, tends to be socially conservative, is organized to a considerable extent along tribal lines, and is among the less populous and also the poorer countries of the Arab world. Jordanian society is also marked by an important cleavage between Jordanians of Palestinian origin and other Jordanians. Palestine, which is struggling for statehood, has a tradition of secular nationalism and strong relations with its diaspora. Until very recently, the Palestine national movement had been symbolized and led for nearly four decades by a single individual. The three political communities also differ with regard to their history of foreign relations. Algeria

has a legacy of intense French colonialism and continues to have very important ties to France; the British were the dominant imperial power prior to Jordanian independence, and Jordan is today one of the most important American allies in the Arab world; and the Palestinian political experience is shaped by its historic and continuing relationship with Zionism and Israel.

The surveys in Jordan and Palestine were funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation and the survey in Algeria was funded by the American Institute for Maghrib Studies. All are based on representative national samples. The survey in Jordan was conducted by the Center for Strategic Studies at the University of Jordan, the survey in Palestine was conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research in Ramallah, and the survey in Algeria was conducted by a team at the University of Algiers. All three surveys involved three-stage cluster sampling based on the most recent national census, 1994 in Jordan, 1997 in the West Bank and Gaza, and 1998 in Algeria. The same interview schedule was administered in Jordan and Palestine. It was used in Algeria as well, although supplemented by a number of items dealing with domestic policy issues in that country.

Political culture orientation is the dependent variable in the analysis to follow, and respondents were rated according to whether or not they possess a “democratic” political culture orientation. For purposes of the present analysis, ratings are based on items from the survey instrument that measure the following six normative and behavioral dimensions: (1) political tolerance, (2) support toward gender equality, (3) political interest, (4) political knowledge, (5) civic participation, and (6) interpersonal trust. To measure each dimension, two or more highly intercorrelated items were combined to form an additive index; the six resulting indices were then factor analyzed, which generated a two-factor solution; and finally, respondents above the midpoint on both sets of factor scores produced by this analysis have been classified as having a

democratic political culture orientation. The specific items used to measure each of the six dimensions are listed in an appendix.

The independent variables in the analysis are two different kinds of Islamic orientations. The first is the degree to which an individual seeks personal guidance and support from religion, measured by the degree to which respondents report finding comfort in religion and by the

likelihood they consult religious officials when seeking guidance in personal affairs. The second, which has not been the examined in previous political attitude research but is no less important, is liberalism-conservatism in the interpretation of religious codes. As in other instances where a body of law must be interpreted and applied to present-day and changing real-life circumstances, there is disagreement and debate among Muslims, including devout Muslims, about whether to be guided by a strict, literal, and historically dominant construction of Islamic law or by a

construction that emphasizes adaptability and looks for the underlying spirit and intent of the law. Islamic interpretation is measured by an item that reminds respondents that “Muslim scholars and jurists sometimes disagree about the proper interpretation of Islam in response to present-day issues,” and then asks them to evaluate three issues on which there is disagreement about what Islam requires and prohibits: coeducation at universities, charging interest on bank loans, and citizenship in the Muslim umma.

The same two items measuring importance of religious guidance in personal affairs and the same three items measuring liberalism-conservatism in religious interpretation, all of which are listed in the appendix, have high loadings on a single factor in the three countries for which data are available. Factor scores derived from these analyses are the measures of the two variables in the analysis to follow. The analysis also includes several other non-dependent variables. They may be considered control variables since the primary purpose of this paper is to

assess the influence of religious orientations on political culture. They may also be regarded as independent variables, since their own explanatory power may be of interest as well. One of these variables is judgment about the regime in power, measured by intercorrelated items that ask respondents to evaluate how good a job the government is doing in running the country and to indicate how much or little confidence they have in the government. Factor scores based on these items have been generated and are employed in the analysis. The other variables are sex, education, and age.

Findings

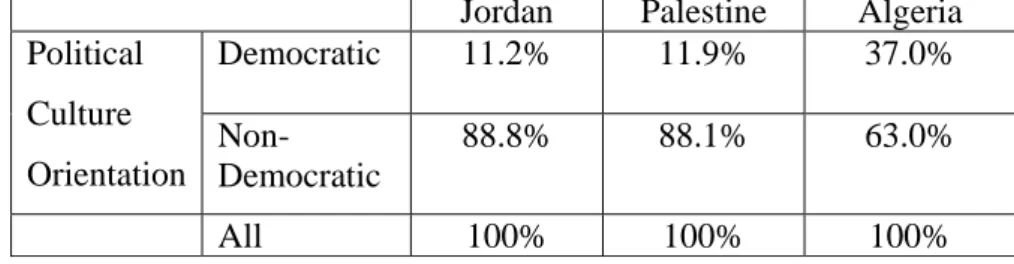

Table 1 shows the proportion of Jordanians, Palestinians, and Algerians who possess a democratic political culture orientation. The proportions are similar in the Jordanian and Palestinian cases; in both countries, only 11-12 percent of the respondents have a democratic orientation. By contrast, the Algerian case stands out from Jordan and Palestine; 37 percent have a democratic political culture orientation. Some minor question wording and coding differences were introduced by the Algerian research team on one item, but it is unlikely that this contributed more than marginally to the difference between Algeria and the other two countries.

Accordingly, it seems reasonable to conclude that some of the history and political experience that set Algeria apart from Jordan and Palestine have contributed to the greater emergence, in relative terms, of a democratic political culture. Among these aspects may be the mobilization and modernization resulting from Algeria’s extended experience with centralized planning and socialist development after independence or, closer to the present, its deeper experience with partisan diversity and competitive elections.

Table 2 presents the results of binary regression analyses for Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria in which the presence or absence of a democratic political culture orientation is the dependent variable. The primary independent variables, again, are the importance of religion in personal affairs and liberalism-conservatism in Islamic interpretation. Other variables include assessment of the governing regime, sex, age, and educational level.

(Table 2 about here)

Table 2 shows both some differences and some similarities across the three countries. In Jordan, liberalism in Islamic interpretation and higher educational level are related to the

presence of a democratic political culture orientation to a statistically significant degree, with p = .002 or less in both instances. In Palestine, liberalism in Islamic interpretation and higher educational level are again related to the dependent variable to a statistically significant degree, with p = .005 or less. In addition, lesser importance of religious guidance in personal affairs, male sex, and older age are also related to a statistically significant degree to the presence of democratic political culture orientation. The three p values are between .006 and .039. Finally, in Algeria, the independent variables in statistically significant relationships are importance of religion in personal affairs, sex, age, and educational level. Specifically, greater importance of religion in personal affairs, male sex, older age, and higher education level are all associated with the presence of a democratic political culture orientation. Probability values are .016 or lower.

It is notable that neither of the two identical variable relationships found in all three countries concerns Islam. One of these involves education. Better educated individuals are disproportionately likely to possess a democratic political culture orientation. Given the

important differences among Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria, it would appear that this relationship in not condition-specific. Rather, following the logic of a most different system research design,

is probably reasonably generalizable. The other identical finding is the absence of any a

significant relationship involving assessment of the governing regime. In no instance is either a positive or a negative evaluation of the government strongly related to the presence of a

democratic political culture orientation. This finding, for the same reason, would also appear to be somewhat generalizable, refuting the plausible hypothesis that antipathy to the government in a non-democratic political setting tends to give rise to democratic values and behavioral norms.

With respect to norms pertaining to Islam, the primary concern of the present inquiry, both of the relevant independent variables are related to democratic political culture orientation to a statistically significant degree in two of the three countries. But it is not the same two countries in each instance, and in one case the direction of the relationship differs. In Palestine, men and women for whom religious guidance is less important are disproportionately likely to possess a democratic political culture orientation, whereas in Algeria those for whom religious guidance is more important are disproportionately likely to possess this orientation. Coupled with the finding that the importance of religious guidance has no explanatory power in Jordan, this suggests that the influence of personal religious involvement is not consistent but rather highly conditional in Arab societies, and most likely in non-Arab and non-Muslim societies as well.

There is too much over-determination to do more than offer informed speculation about the some of the conditionalities associated with each observed relationship. Attributes and experiences shared by Palestine and Algeria but not Jordan are a strong tradition of secular nationalism; a political system that is republican rather than monarchical; and particularly intense involvement with a Western democracy, Israel in the Palestinian case and France for Algerians. The two countries, in contrast to Jordan, have also been marked in recent years by extensive

turmoil and violence. Some of these considerations, singly or in combination, may define the conditions under which personal religious involvement has explanatory power. Palestine and Algeria also differ from one another in important respects. Palestine is more traditional, being marked to a much greater degree by the prominence of extended notable families, by the

influence of Islamic trusts and other religious institutions, and by the importance of patron-client relationships. Algeria, by contrast, is more mobilized and proletarian as a result of its intense colonial experience and, after independence, the government’s emphasis on centralized planning and socialist development.

Taken together, these characteristics suggest several hypotheses deserving of further study: personal religious involvement is more likely to influence political culture orientation in Arab and Muslim societies with a tradition of secular nationalism and intense interaction with Western democracies; personal religious involvement discourages the emergence of a democratic political culture orientation when a society with these characteristics is more traditional; and personal religious involvement contributes to the emergence of a democratic political culture orientation when a society with these characteristics is more mobilized and developed.

Liberalism-conservatism in the interpretation and application of Islamic strictures, an important religion-related variable that has not been studied previously at the individual level of analysis, also has significant explanatory power in two of the three countries for which data are available. In Jordan and Palestine, but not in Algeria, men and women with a more liberal perspective are disproportionately likely to possess a democratic political culture orientation. Again, it is only possible to speculate about the attributes shared by the two countries but not by Algeria that might constitute conditions under which this relationship obtains. Jordanian society, like that of Palestine, is much more traditional than that of Algeria. Although by no means

absent in Algeria, religious institutions, notable families, and clan-based social structures are much less influential than in Jordan and Palestine, having declined in importance first under the French and then under the centralized planning and state socialism that followed independence. This suggest, plausibly, that differing tendencies in the interpretation and application of religious prescriptions to everyday life have a much greater impact on political norms and values in societies that are more traditional than in societies that are less traditional.

Finally, male sex and older age are associated with the presence of a democratic political culture orientation in Palestine and Algeria but not Jordan. Attributes that distinguish Palestine and Algeria from Jordan, as noted, include a tradition of secular nationalism, a republican political system, intense involvement with a Western democracy, and turmoil and violence in recent years. A tradition of secular nationalism and greater exposure to Western democracy would seem to be the most important of these characteristics so far as conditions that specify when male gender and older age are associated with a democratic political culture orientation is concerned. Another possibility, suggested by an earlier study in Algeria (Tessler, Konold and Reif 2004), is that older men constitute a political generation and that their disproportionate likelihood to possess a democratic political culture orientation reflects values shaped not only by secular nationalism and exposure to Western democracy but also by the fact that the society characterized by these attributes was relatively peaceful when they were in their late teens and early 20s. .

Conclusion

Research on democratic transitions and consolidation indicates that successful democratization requires the existence of a democratic political culture orientation among a

significant proportion of a country’s citizens. Accordingly, there have been many data-based studies of political culture in countries where a democratic transition is taking place. By contrast, there has been little empirical research on political culture in non-democracies, particularly in the Arab world. The present study contributes to filling this gap by presenting findings about the determinants of political culture orientations among ordinary citizens in Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria. It investigates in particular the degree to which, and the conditions under which, norms associated with Islam either promote or discourage the emergence of a democratic political culture orientation.

Whereas several previous investigations suggest that personal religious involvement has relatively little influence on political attitudes in Arab countries, survey data from Jordan, Palestine, and Algeria in 2003-2004 indicate that this frequently is not the case with respect to values and behavior patterns associated with a democratic political culture orientation. They suggest, rather, that more than one kind of religious orientation is relevant; that greater reliance on religion in personal affairs sometimes pushes toward, sometimes away from, and sometimes is unrelated to the possession of a democratic political culture orientation; that liberalism in the interpretation of Islamic legal codes and prescriptions, a heretofore neglected dimension of views pertaining to Islam, often pushes toward and never pushes away from a democratic political culture orientation; and that the importance of each of these dimensions in accounting for variance in political culture orientation is conditional upon country-level attributes and

experiences. Sorting out which dimensions of religion shape political culture in which ways and under which conditions, and whether the same relationships obtain when the religion is not Islam, is a promising avenue for future research.

Table 1. Proportion of Jordanian, Palestinian, and Algerian Respondents with a Democratic Political Culture Orientation

Jordan Palestine Algeria

Democratic 11.2% 11.9% 37.0% Political Culture Orientation Non-Democratic 88.8% 88.1% 63.0% All 100% 100% 100%

Table 2. Logıstic Regressıon Showing Influence on democratic political culture orientation of the importance of religion in personal affairs, conservatism-liberalism in Islamic interpretation, assessment of the governing regime, and sex, age, and educational level.

Jordan Palestine Algeria

Religion more important in personal affairs .070 .128 -.233 .095** .243 .092** Greater liberalism in Islamic

interpretation .372 .120** .275 .097** .087 .087 More negative assessment of governing

regime .159 .121 -.153 .105 -.148 .089 Female sex -.288 .267 -.568 .208** -.420 .175** Older age .010 .010 .017 .006* .152 .042***

Higher educational level .391

.099***

.546 .074***

.454 .083*** Note: Dependent Variable is coded 0=not a democratic political culture orientation, 1=a

democratic political culture orientation. Table presents logit coefficients (B) with standard errors in parentheses.

Appendix: Items Used to Measure Dependent and Independent Variables

People sometimes talk about the factors that make a person qualified for national leadership. On this card are listed six of the qualifications to which different people would give priority. Would you please say which one of these you, yourself, consider the most important? Which would be the next most important? And which would be third? Coded according to whether “Openness to Diverse Political Ideas” ranks first or second. Jordan and Palestine: Do you disagree or agree with this statement: Christian citizens of our country should have the same rights as Muslim citizens to hold any political office, including to president of the state.

Political Tolerance

Algeria: People sometimes talk about what the aims of this country should be for the next ten years. On this card are listed four of the goals to which different people would give priority. Would you please say which one of these you, yourself, consider the most important? Which is the second more important, and which is the third most important? Coded according to whether “Assuring equal rights for all citizens, regardless off religion or gender” ranks first or second.

Do you disagree or agree with this statement: “On the whole men make better political leaders than women do”?

Do you disagree or agree with this statement: “A university education is more important for a boy than a girl”?

Support for Gender Equality

Do you disagree or agree with this statement: “A woman may work outside the home if she wishes”?

How important is politics in your life? Political

Interest When you get together with your friends, would you say that you discuss political matters frequently, occasionally, or never?

Can you name the Foreign Minister? Can you name the Minister of Finance? Can you name the Speaker of Parliament? Political

Knowledge

How often do you read the newspaper?

How often do you interact with people at social, cultural, or youth groups? How often do you interact with people at your mosque or church or at religious associations?

How often do you interact with people at political groups, clubs, or discussion groups? How often do you interact with people at your professional associations?

Civic Participation

How often do you interact with people at sports or creation groups?

Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that most people cannot be trusted?

Political Trust

I will read some statements about social and political issues. Please indicate your agreement or disagreement with each. You can trust no one these days.

Do you find that you get comfort and strength from religion? Very much, Some, A little, Very little or none

Importance of religion in Personal Affairs

When you need advice about a personal problem, how often do you consult each of the following? An imam or f’kih.

Today as in the past, Muslim scholars and jurists sometimes disagree about the proper interpretation of Islam in response to present-day issues. For each of the statements listed below, please indicate whether you agree strongly, agree, disagree, or disagree strongly with the interpretation of Islam that is presented.

-- It is a violation of Islam for male and female university students to attend classes together

-- Banks in Muslim countries must be forbidden from charging even modest interest on loans because this is forbidden by Islam

Liberalism-Conservatism in Islamic Interpretation

-- Nationalism (like Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish) is incompatible with Islam because Islam requires that Muslims be united in a single political community (the ummah) rather than be citizens of different states and loyal to different governments.

People have different views about the system for governing the country. In your opinion how good a job is the government doing?

Evaluation of Governing

Regime I am going to name a number of public and civic institutions. For each one, could you tell me how much confidence you have in it: a great deal of confidence, quite a lot of confidence, a little, too little, or none at all. The Government

References

Almond, G. and Verba, S. 1963. The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five

nations. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

Almond, G. and S. Verba. 1980. The civic culture revisited. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

Huntington, S. 1993. “Democracy’s third wave.” In Larry Diamond and Marc Plattner, eds.

The Global Resurgence of Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Huntington, S. 1991. The third wave. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Inglehart, R. 2000. “Culture and democracy.” In Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel Huntington, eds. Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress. New York: Basic Books. Kedourie, E. (1994). Democracy and Arab political cultures. London: Frank Cass Publishers. Lewis, B. 1994. The Shaping of the Modern Middle East. New York: Oxford

Mujani, S. 2004. Religious Democrats: Democratic Culture and Muslim Participation in Post

Suharto Indonesia. Columbus: The Ohio State University Ph.D. Thesis.

Rose, R. 1997. “Where Are Postcommunist Countries Going?” Journal of Democracy 8 (July): 92-108.

Schmitter, P. and T. L. Karl. 1993. “What Democracy Is... and Is Not.” In Larry Diamond and Marc Plattner, eds. The Global Resurgence of Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tessler, M. “Do Islamic Orientations Influence Attitudes Toward Democracy in the Arab World: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Algeria,” International Journal of

Comparative Sociology 2 (Spring 2003): 229–49.

Tessler, M. 2002. “Islam and Democracy in the Middle East: The Impact of Religious Orientations on Attitudes Toward Democracy in Four Arab Countries.” Comparative

Politics 34 (April): 337-254.

Tessler, M., C. Konold, and M. Reif. 2004. “Political Generations in Developing Countries: Evidence and Insights from Algeria.” Public Opinion Quarterly 68 (Summer): 184-216.