R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

The evolution of Taiwan

’s National Health

Insurance drug reimbursement scheme

Jason C Hsu

1*and Christine Y Lu

2Abstract

Background: The rapid growth of health care expenditures, especially pharmaceutical spending, is a challenge for many countries. To control increasing pharmaceutical expenditures and to enhance rational use of drugs, Taiwan’s National Health Insurance drug reimbursement system has evolved over time since its introduction in 1995. This study reviewed Taiwan’s drug reimbursement scheme: its development and evolution in the last two decades, and implications and impacts of recent policies for drug pricing. We also provide recommendations for possible improvement.

Methods: We conducted a review of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance drug reimbursement scheme. We focused

on three major components of the scheme: (i) the scope of drug coverage; (ii) pricing system for pharmaceuticals under the scheme; and (iii) adjustment of drug reimbursement prices. We reviewed the literature and public policy documents.

Results: The National Health Insurance delisted 176 and another 240 behind-the-counter products (e.g., antacids, vitamins) between 2005 and 2006 to reduce pharmaceutical expenditures. For the pricing of pharmaceuticals, policy evolution can be divided into four phases since 1995; the present system emphasizes stakeholder engagement, health technology assessment, domestic R&D, and improving quality of products. To close the gap between drug reimbursement prices and procurement prices, eight rounds of drug price surveys and adjustments have been implemented since 2000.

Conclusions: Taiwan’s National Health Insurance drug reimbursement scheme has evolved substantially over time to provide more equitable and affordable access to prescription medicines. However, more work is still needed as irrational difference in reimbursement and procurement prices persists and the total expenditure of the drug reimbursement scheme continues to increase at unsustainable rates.

Keywords: Universal health coverage, Drug policy, Reimbursement, Medicines coverage, National Health Insurance, Taiwan

Introduction

Access to health care, including ‘essential’ medicines, is regarded as a human right by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [1]. The vast majority of people and governments around the world generally support the implementation of national health insurance. Many economically developed countries have implemented national health insurance that aims to pro-vide its members with satisfactory care services to achieve

“health for all” [2]. However, many healthcare systems have sometimes achieved poor performance given the re-sources spent and/or are still undergoing reform.

In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance (NHI) is a compulsory social insurance system in which the coverage rate of its 23 million residents is as high as 99% currently. Since the introduction in August 1995, the National Health Insurance has gained public recognition as Taiwan becomes comparable with neighboring countries (like Japan, South Korea and Singapore) in terms of quality of care, healthcare cost control, drug spending growth, and public satisfaction [3]. However, concerns have been raised about its financial sustainability.

* Correspondence:jasonhsuharvard@gmail.com

1School of Pharmacy and Institute of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical

Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, No.1, Daxue Rd., East Dist., Tainan City 70101, Taiwan R.O.C

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Hsu and Lu; licensee BioMed Central. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Around the world, countries generally adopt a pluralistic system of healthcare coverage that maximizes consumer choice (e.g., USA) or a predominantly single, universal scheme for healthcare coverage that maximizes equity and the prospects for cost control. Taiwan adopts the single sys-tem model. The National Health Insurance is contracted with public, private, and corporate healthcare institutions, which provide a range of covered healthcare services, in-cluding prescription drugs. The National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA; formerly known as the Bureau of NHI, the name was changed in 2013), set up by the govern-ment, reimburses the contracted institutions for the ser-vices provided.

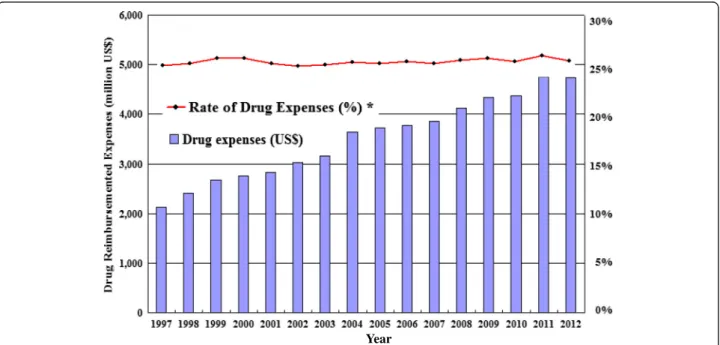

The rapid growth of healthcare costs is a challenge faced by all countries, especially the growth of pharma-ceutical costs, which is even more evident [4,5]. The total drug expenditure of Taiwan’s National Health In-surance was about US$2,133 million in 1997, and it in-creased by around US$173 million each year. In 2012, pharmaceutical expenditures reached US$4,733 million, which accounted for 25.1% of the total healthcare expend-iture (Figure 1) [3]. The main causes of rising healthcare costs and pharmaceutical expenditures include the aging population, the increasing number of patients with chronic diseases, increasing drug prices, larger drug usages, and the availability of new, more expensive drugs [6-8].

To control growing pharmaceutical expenditures, the NHIA implemented multiple policies for prescription drug reimbursement. The purpose of this study was to re-view and summarize the evolution of Taiwan’s drug reim-bursement scheme over the last two decades, including its

development and major changes for drug pricing, and im-plications and impacts of its recent policies. We also highlighted possible policy-induced problems that need to be addressed. Finally, we provide some recommendations for how Taiwan’s drug reimbursement scheme can con-tinue to evolve to ensure the goals of financial sustainabil-ity and rational use of medicines [9].

Method

We conducted a review of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance drug reimbursement scheme. We focused on policies implemented by the NHIA over the last two decades. We reviewed policies that targeted differ-ent issues: (1) the scope of drug coverage, (2) the pri-cing system for pharmaceuticals under the scheme, and (3) adjustments of drug reimbursement prices. Similar to many countries, medicines are classified into three categories in Taiwan: (a) prescription drugs, (b) drugs designated by physicians or pharmacists, which can be purchased at pharmacies without prescriptions (e.g., antihistamines, antitussive agents)– generally known as behind-the-counter or pharmacist only drugs, and (c) over-the-counter (OTC) medications.

We collected and reviewed historical archives including official documents, books, published articles, research pro-jects, conference records, websites, newspapers, speeches etc. After reviewing abovementioned materials relating to the drug reimbursement scheme, we also examined policy implementation and policy changes, summarized the known impacts of the policies, and highlighted possible policy-induced problems that need to be addressed for system improvement.

Year

Results

NHIA policies over the last two decades largely targeted prescription drugs and behind-the-counter drugs. Policies governing the scope of drug coverage

According to Article 51 in the National Health Insurance Act (amended in 2011) [10], the NHIA does not reim-burse the following: (1) medicines that are approved by the Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (Taiwan FDA) but are not used for disease treatment, such as contracep-tive, hair tonic, dark spots detergent, smoking cessation patches; (2) some vaccines (e.g., quadrivalent Human pap-illomavirus types vaccine); (3) over-the-counter drugs and non-prescription drugs which should be used under the guidance of a physician or pharmacist (also called the behind-the-counter drugs); (4) drugs for human-subject clinical trials; (5) drugs which are deemed by the National Health Insurance as not essential for medical treatment (e.g. dentures, artificial eyes, spectacles, hearing aids, wheelchairs, canes, and other treatment equipment) or not cost-effective; (6) drugs which do not conform to the indication that stipulated in the approved indication for licensing and/or the “Reimbursement Restriction” enacted by the National Health Insurance. However, in special cases, an application for prior authorization can be made to the National Health Insurance, and the drug will be reimbursed if authorization is given; and (7) any other drug which the NHIA publicly announces that it will not be reimbursed [11].

Behind-the-counter drugs were covered by the former Civil Servant Insurance and Labor Insurance and in the early years of the National Health Insurance. The NHIA reviewed and reduced the scope of coverage of counter drugs over time [11]. Some behind-the-counter drugs were delisted to meet the priorities of the National Health Insurance, in accordance with Article

51 of the National Health Insurance Act, and more gen-erally, to establish patient expectations and the culture of rational use of medicines and basic self-healthcare. This change also intended to reduce costs of the National Health Insurance as well as making better use of its resources for treatment of major diseases.

This delisting of behind-the-counter drugs also bene-fited consumers who needed such products for treat-ment of minor illnesses (e.g., headache, cold). They can save time and related expenses when they choose to pur-chase medicines at pharmacies instead of visiting physi-cians at primary care clinics or hospitals. For example, a patient’s out-of-pocket costs are less if s/he chooses to purchase medicines for headache from pharmacies (only US$3) compared with visiting a physician which requires physician visit copays (US$5).

In total, the National Health Insurance delisted 176 (e.g., some antacids) and 240 (e.g., some vitamins, electrolytes) behind-the-counter products in 2005 and 2006 respect-ively. However, there was considerable resistance from both physicians and patients; thus, no further behind-the-counter drugs were delisted. Currently, there are still around 1400 behind-the-counter products reim-bursed by NHIA (e.g., gastrointestinal drugs, antihista-mines, antitussive agents) [3]. However, delisting in the future is likely under the pressure to contain costs. The pricing system for pharmaceuticals under the drug reimbursement scheme

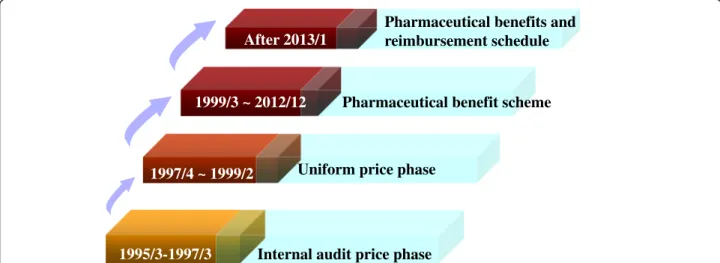

The pricing system under the drug reimbursement scheme of the National Health Insurance can be divided into four phases over time: (1) internal audit price (1995/3-1997/3); (2) uniform pricing (1997/4-1999/2); (3) Pharmaceutical benefit scheme (1999/3-2012/12); and (4) Pharmaceutical benefits and reimbursement schedule (after 2013/1), which are described as below and summarized in Figure 2.

1995/3-1997/3 1997/4 ~ 1999/2

1999/3 ~ 2012/12 After 2013/1

Internal audit price phase Uniform price phase

Pharmaceutical benefit scheme

Pharmaceutical benefits and reimbursement schedule

Prior to the implementation of the National Health Insurance in 1995 in Taiwan, about 50% of the popula-tion was insured under the Civil Servant Insurance, Labor Insurance, and Farmer’s Health Insurance. At the time, pharmaceutical companies were allowed free pri-cing, and they were subject to hospitals’ pharmaceutical tender and negotiation to determine the price of drugs in hospitals. Hospitals would bill the insurers. The in-surers would then reimburse individual hospitals by an approach known as “transaction cost-plus”. For drug reimbursements, the joint bid price would be paid to public hospitals while to this price plus 10-20% would be paid to private hospitals. Profits were usually used to pay for drug warehouse management, dispensing and other expenses. High-level hospitals tended to use more expensive, brand-name drugs or imported drugs be-cause of profits from pharmaceutical sales. At the time of public bidding in public hospitals, manufacturers were reluctant to cut prices, resulting in high tender prices. Prescription drugs were paid out-of-pocket in primary care settings because most patients were not insured under the Government Employee’s Insurance, Laborer Insurance, or Farmer’s Health Insurance. As a result, patients were sensitive to drug prices; many would choose domestic, generic drugs over the more expensive, brand-name drugs or imported drugs.

At the early stage of the National Health Insurance (1995–1997), the NHIA released the “National Health Insurance Drug Items Table” that listed products being covered, and drugs were reimbursed through the “in-ternal audit pricing” approach. However, the in“in-ternal audit pricing system was unclear, and the price of imported generic drugs was relatively high due to a lack of international drug price comparison. These led to substantial variations in drug prices between domestic drugs and drugs by international manufacturers [12]. Hospitals generally adopted the “fee for service” ap-proach for drug reimbursements while primary care clinics adopted the “fixed fees by days of supply” ap-proach (e.g., one-day supply of any medications received a reimbursement of NT$35, regardless therapeutic indi-cation and actual procurement price; two-day supply was NT$70; and three-day supply was NT$100). The following ‘consequences’ were observed: (1) primary care clinics tended to reduce drug costs and were reluc-tant to release prescriptions to patients so patients had to obtain drugs at the clinics (resulting in the phenomenon of “next-door pharmacy”, which had negative impacts on the separation of drug prescribing and dispensing); (2) some patients were transferred to higher level hospitals in order to obtain drugs of higher prices and/ or for longer supplies; and (3) use of drugs of higher prices in primary care clinics was subsequently reduced [13,14].

During 1997–1999, the NHIA invited the pharmaceut-ical industry to engage in the development of pricing guidance for drugs covered under the NHI (“National Health Insurance drug pricing principles”). The goals were to lower drug prices, control the growth of drug prices, reduce the prices of brand-name drugs and gen-eric drugs, encourage the use of gengen-eric drugs, and pro-tect the domestic generic drug market. The pricing guidance governed drug pricing by a drug classification system: (1) new drugs: the NHIA invited the medical and pharmaceutical experts to engage in the review and approval process; (2) the compound and special specifi-cation drugs: paid the same minimum price as other drugs of the same composition; (3) brand-name drugs: brand-name drugs were subdivided into two categories: ones that have no bioavailability/bioequivalence (BA/BE) generic drugs as alternatives in the market, and others that have BA/BE generic drugs as alternatives. Drugs of the former category were priced according to the inter-national drugs with average market prices; while the price of the latter category must not exceed 85% of the average market price of international drugs; (4) the price of BA/BE generic drugs must not exceed the price of brand-name drugs; and (5) the price of non-BA/BE generic drugs must not exceed 80% of the price of brand-name drugs. From then on, drugs covered by the National Health Insurance were uniformly priced.

During 1999–2012, the NHIA attempted to address the problem of differences between drug procurement and reimbursement prices. To determine the market drug price difference, the NHIA required hospitals and manufacturers to provide the actual transaction prices and trading volumes. However, many hospitals and man-ufacturers resisted such investigation or supplied false declarations about prices, and the drug price gap remained a serious problem. The NHIA therefore announced the “Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme” in March 1999 to gov-ern the listing of drugs, the pricing of pharmaceuticals, and the adjustment of drug reimbursement prices. It also set the target to reduce the gap in drug prices to less than 15% within five years. Moreover, NHIA announced in April 1999 that drug price surveys for NHI reimbursed drugs were to be conducted every 1–2 years. Since then, the NHIA has implemented eight drug price surveys; new drug reimbursement prices were announced and imple-mented respectively on April 1st, 2000, April 1st, 2001, March 1st, 2003, September 1st, 2005, November 1st, 2006, October 1st, 2009, November 1st, 2011 and May 1st, 2014 (Table 1) [15]. Adjustments of drug prices are discussed in detail in the next section.

The“Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme” was replaced by “Pharmaceutical benefits and reimbursement schedule” on January 1st, 2013. Compared with “Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme”, the present new scheme emphasizes

stakeholder engagement (including the insurer and the relevant authorities, experts and scholars, the insured, employers, health care service providers, etc.) to discuss and design the listing of drugs and reimbursement prices for specific products. Further, health technology assess-ment (considering human health, medical ethics, cost-effectiveness of products, and financial sustainability of the NHI) was required for new drugs prior to listing in the National Health Insurance under this new phase. In 2007, the Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE) was created to conduct health technology assessment (HTA), that is, assessment of comparative efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and budget impact of new drugs. The CDE only provides HTA reports to the NHIA, it is not involved in pricing. The NHIA considers HTA evidence as part of the information used for listing and reimbursement decisions [16].

The adjustment of drug reimbursement prices

To ensure reasonable drug prices and close the gap be-tween procurement and insurer reimbursement prices for prescription drugs, Taiwan made multiple efforts. Be-cause institutions procure large quantities of medicines, procurement prices are typically lower than the amount reimbursed by the NHIA and the differences constitutes a profit for hospitals [17]. To assess procurement prices, the NHIA conducted surveys to obtain drug wholesale prices from pharmaceutical companies and procurement prices from hospitals since 1999 [18]. Reimbursements were adjusted if there was a difference of 30% or more between the average procurement price and the NHI re-imbursed price. Prices were subsequently monitored and adjusted every two years for patented products, for prod-ucts whose patent right has expired for more than five years, and for products that have no patent right. These drugs are further divided into the following two categories: (1) drugs from original R&D pharmaceutical companies, drugs of which the process of pharmaceutical form com-plies with “The Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme -Good manufacturing practice (PIC/S GMP)” require-ments, BA/BE generic drugs, drugs approved to by the US

FDA and/or The European Medicines Agency for market-ing, controlled items of BE generic drugs; (2) common generic drugs which do not fall into the first category [11]. Studies have been conducted to examine effects of drug reimbursement price reductions in Taiwan. Lee et al. [19] assessed the effects of six drug price policies and found that they reduced pharmaceutical expendi-tures, especially for outpatient medications and for hospi-tals (compared with clinics) [19]. Chen et al. [17] showed that reimbursement price reductions for targeted cardio-vascular medications reduced the daily medical use and expenditures, but did not affect non-targeted products [17]. Chu et al. [20] studied price reductions for anti-hypertensive drugs. They suggested that reimbursement price adjustments may have created an incentive for phy-sicians to prescribe drugs with higher profit margins, and to increase prescription duration or the number of drug items per prescription [20]. Hsiao et al. [21] did not find strong associations between reimbursement price adjust-ments and drug utilization and expenditures during 2001–2004. Chu et al. [22] studied effects of reimburse-ment price adjustreimburse-ments on outpatient hypertension treat-ments among the elderly. They found that the average cost per prescription increased slightly, and that physi-cians tended to prescribe drugs whose prices were not re-duced instead of those subject to price reductions. Findings by Hsu et al. [18] indicated that prescribing shifted from targeted to non-targeted products [18]. Over-all, these studies suggest shifts in use from targeted to non-targeted products to maintain profits from drug price gaps but whether they reduced pharmaceutical expendi-tures is unclear.

Discussion

The study provides a review of the development and evolu-tion of Taiwan’s universal drug reimbursement scheme under its National Health Insurance. We highlighted major policy changes for drug pricing over the last two decades and their known impacts and implications. It is important to note that many policy changes (e.g., delisting of behind-the-counter products, introduction of HTA) remain to be evaluated for their impacts on medication use, drug prices, quality of care, and pharmaceutical expenditures.

With the goal to reduce pharmaceutical expenditures to the government, about 400 behind-the-counter prod-ucts were delisted from Taiwan’s national Drug Reim-bursement Scheme. This coverage change also aimed to establish patient expectations and the culture of rational use of medicines and basic self-healthcare for minor ill-nesses such as headache or cold. This is not surprising; many national drug coverage schemes do not reimburse or reimburse only selected few behind-the-counter products, e.g., Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Misuse, under-use or over-use of behind-the-counter drugs are Table 1 List of drug price surveys and adjustments

Order Date Estimated cost-savings (million US$) 1st April 1st, 2000 16.67 2nd April 1st, 2001 153.33 3rd March 1st, 2003 190.00 4th September 1st, 2005 81.00 5th November 1st, 2006 500.00 6th October 1st, 2009 195.67 7th November 1st, 2011 – 8th May 1st, 2014 – Resource: Huang [15].

possible unintended consequences. Inappropriate consumer self-medication may lead to subsequent medication-related adverse health outcomes (e.g., medication error or poison-ing), or negative health outcomes if appropriate treatment was delayed or not used, which may lead to subsequent in-crease in healthcare costs. It is important that delisting of behind-the-counter medications is accompanied by appro-priate educational programs directed to consumers and pharmacists to ensure rational use of medicines. Taiwan may learn from Australia, which has worldly recognized multifa-ceted programs to improve rational use of medicines [23].

To ensure reasonable drug prices and close the gap between procurement and insurer reimbursement prices for prescription drugs, Taiwan and other countries (e.g., China) [24] have made multiple efforts. We highlighted how the pricing system under Taiwan’s Drug Reimburse-ment Scheme has evolved over time. While the gap be-tween drug procurement and reimbursement prices has narrowed, price difference persists. For instance, there are substantial price difference between drug reimburse-ments and claims made by primary care clinics for pre-scription drugs that use the “fixed fees by days of supply” approach mentioned above.

Whether drug price adjustments achieved the intended cost-savings is unclear. Despite several waves of drug price adjustments to close the gap between procurement and reimbursement prices, the total pharmaceutical ex-penditures is still on the rise (average yearly growth rate for pharmaceutical expenditures from 1997 to 2012 is 8.13%). Reasons for such growth include: (1) adjust-ments of drug reimbursement prices only reduce the prices of targeted products, not the volume of use; (2) off-label use: it has not been estimated how much expendi-tures are attributed to use of prescription medications out-side approved indications under the Drug Reimbursement Scheme; reimbursed indications are largely based on clinical treatment guidelines, Taiwan FDA approved in-dications and specification made by NHIA or medical associations; (3) drug waste (unnecessary use and stock-piling of medications): this issue is particularly common for behind-the-counter drugs (e.g., antacid agents and vitamins), which led to delisting of some products by the NHI; however, delisting was opposed by many phy-sicians and patients; and (4) the availability of innova-tive, expensive drugs such as cancer targeted therapies: the NHI created the HTA body to assess the cost-effectiveness of new drugs to inform decisions about reimbursement.

We recommend that capitation/case payment models [25], diagnosis related groups (DRGs) [26-28] and pay for performance [29,30] are some possible alternative ap-proaches, that have been used by other countries and show promise in controlling total pharmaceutical expenditures without substantially reducing the quality of health care.

Health Technology Assessment is increasingly adopted for making drug reimbursement decisions throughout the Asia-Pacific markets. Apart from Taiwan, countries in this region with established HTA system include Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Thailand [31,32]. Economic evaluation should not only inform the decision of reimbursement but also used to negotiate prices with manufacturers. In addition, many countries (including countries in Asia-Pacific markets such as Australia, South Korea) are adopting risk-sharing agree-ments for funding high-cost innovative drugs such as adalimumab and imatinib. Risk-sharing agreements are typically between a payer and a pharmaceutical company in which the partners negotiate the price of a product and/or the overall spending depending on volumes sold, clinical outcomes achieved or patient populations who receive the drug [33-35]. The intent is that companies share the financial risk of payers to reimburse the drug, and pay for the drug when an agreed volume or budget is exceeded, or intended clinical outcomes are not achieved. Taiwan could learn lessons from neighboring countries adopting HTA and risk-sharing agreements to address the challenge of high-cost medicines.

Conclusion

Taiwan’s Drug Reimbursement Scheme under its univer-sal National Health Insurance has come a long way over the last two decades. It is highly regarded particularly on the basis of comprehensive drug coverage, minimal pa-tient cost burden, and timely access to new medicines. The NHI implemented multiple policy changes to en-hance rational use of drugs and to contain increasing pharmaceutical expenditures. However, while the data are limited, there were opposition from consumers and physicians for some of the changes. Many policy changes remain to be evaluated for their impacts on medication use, quality of care, and pharmaceutical expenditures. Further policy changes may be needed and these should be developed in light of lessons learned by other coun-tries that are also facing similar challenges. Stakeholders (i.e., patients, clinicians, government, industry) need to work closely together to continue to improve rational use of drugs, the quality of healthcare, and the financial sustainability of the National Health Insurance. Evidence-informed policy changes with appropriate stakeholder en-gagement will be important for optimal patient outcomes.

Abbreviations

R&D:Research and development; NHI: National Health Insurance; NHIA: The National Health Insurance Administration; OTC: Over-the-counter; Taiwan FDA: Taiwan Food and Drug Administration; BA/BE: Bioavailability/bioequivalence; CDE: Center for Drug Evaluation; PIC/S GMP: The Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme - Good manufacturing practice; DRGs: Diagnosis related groups; HTA: Health technology assessment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JCH designed the study, collected data, performed analysis, and drafted the manuscript. CYL reviewed all data and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. Both authors approved the final version for submission.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Hsu conducted part of this work as a research fellow in the Harvard Medical School Fellowship in Pharmaceutical Policy Research.

Author details

1

School of Pharmacy and Institute of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, No.1, Daxue Rd., East Dist., Tainan City 70101, Taiwan R.O.C.2Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Received: 3 September 2014 Accepted: 27 November 2014

References

1. Hogerzeil H: Access to essential medicines as a human right. World Health Organisation: Essential Drugs Monitor 2003, (33):25–26. http://apps.who.int/ medicinedocs/en/d/Js4941e/5.html.

2. Gil-Gonzalez D, Carrasco-Portino M, Vives-Cases C, Agudelo-Suarez AA, Castejon Bolea R, Ronda-Perez E: Is health a right for all? An umbrella review of the barriers to health care access faced by migrants. Ethn Health 2014, 13:1–19.

3. National Health Insurance Administration. Website. http://www.nhi.gov.tw/ english/index.aspx.

4. Mullins CD, Wang J, Palumbo FB, Stuart B: The impact of pipeline drugs on drug spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001, 20(5):210–215. 5. Berndt ER: Pharmaceuticals in U.S. health care: determinants of quantity

and price. J Econ Perspect 2002, 16(4):45–66.

6. Levit K, Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A: Health spending rebound continues in 2002. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004, 23(1):147–159.

7. Hsieh CR, Sloan FA: Adoption of pharmaceutical innovation and the growth of drug expenditure in Taiwan: is it cost effective? Value Health 2008, 11(2):334–344.

8. Yang CL, Chao HL, Huang WY, Lin WD, Huang KH, Lai MS: National Health Insurance. Taiwan: Wagner Co Ltd; 2012.

9. Huang SK, Tsai SL, Hsu MT: Ensuring the sustainability of the Taiwan National Health Insurance. J Formos Med Assoc 2014, 113(1):1–2. 10. National Health Insurance Act. Website http://mohwlaw.mohw.gov.tw/Chi/

EngContent.asp?msgid=279&KeyWord=%A5%FE%A5%C1%B0%B7%B1d%ABO% C0I%AAk.

11. National Health Insurance Administration: The National Health Insurance Pharmaceutical Benefits and Reimbursement Schedule. Taiwan: National Health Insurance Administration; 2014. http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/ LawContent.aspx?PCODE=L0060035.

12. Huang CM: The Reform Strategy of NHI drug Expenditure Rationalization. Taiwan: The Bureau of National Health Insurance; 1998.

13. Cheng C, Hsieh CR: Economic analysis of NHI pharmaceutical policies and drug expenditures. Socioecon Law Inst Rev 2005, 35:1–42.

14. Cheng C: An Analysisi of NHI Drug Policies and Pharmaceutical Expenditures. Taiwan: Chang Gung University; 2003.

15. Huang HH, Shen MC, Liu HS: National Health Insurance. Taiwan: Wu-nan Book Inc; 2012.

16. Yang BM: The future of health technology assessment in healthcare decision making in Asia. Pharmacoeconomics 2009, 27(11):891–901. 17. Chen CL, Chen L, Yang WC: The influences of Taiwan's generic grouping

price policy on drug prices and expenditures: evidence from analysing the consumption of the three most-used classes of cardiovascular drugs. BMC Public Health 2008, 8:118.

18. Hsu JC, Lu CY, Wagner AK, Chan KA, Lai MS, Ross-Degnan D: Impacts of drug reimbursement reductions on utilization and expenditures of oral antidiabetic medications in Taiwan: an interrupted time series study. Health Policy 2014, 116(2–3):196–205.

19. Lee YC, Yang MC, Huang YT, Liu CH, Chen SB: Impacts of cost containment strategies on pharmaceutical expenditures of the National Health Insurance in Taiwan, 1996–2003. Pharmacoeconomics 2006, 24(9):891–902. 20. Chu HL, Liu SZ, Romeis JC: Changes in prescribing behaviors after

implementing drug reimbursement rate reduction policy in Taiwan: implications for the medicare system. J Health Care Finance 2008, 34(3):45–54.

21. Hsiao FY, Tsai YW, Huang WF: Price regulation, new entry, and information shock on pharmaceutical market in Taiwan: a nationwide data-based study from 2001 to 2004. BMC Health Serv Res 2010, 10:218. 22. Chu HL, Liu SZ, Romeis JC: Assessing the effects of drug price reduction

policies on older people in Taiwan. Health Serv Manage Res 2011, 24(1):1–7.

23. Weekes LM, Mackson JM, Fitzgerald M, Phillips SR: National Prescribing Service: creating an implementation arm for national medicines policy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005, 59(1):112–116.

24. Lu CY, Ross-Degnan D, Stephens P, Liu BAW: Changes in use of antidiabetic medications following price regulations in China. J Pharm Health Serv Res 2013, 4:3–11.

25. Jirawattanapisal T, Kingkaew P, Lee TJ, Yang MC: Evidence-based decision-making in Asia-Pacific with rapidly changing health-care systems: Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan. Value Health 2009, 12(Suppl 3):S4–S11. 26. Yan YH, Chen Y, Kung CM, Peng LJ: Continuous quality improvement of

nursing care: case study of a clinical pathway revision for cardiac catheterization. J Nurs Res 2011, 19(3):181–189.

27. Schmid A, Cacace M, Gotze R, Rothgang H: Explaining health care system change: problem pressure and the emergence of "hybrid" health care systems. J Health Polit Policy Law 2010, 35(4):455–486.

28. Busato A, von Below G: The implementation of DRG-based hospital reimbursement in Switzerland: A population-based perspective. Health Res Policy Syst 2010, 8:31.

29. Chen PC, Lee YC, Kuo RN: Differences in patient reports on the quality of care in a diabetes pay-for-performance program between 1 year enrolled and newly enrolled patients. Int J Qual Health Care 2012, 24(2):189–196.

30. Cheng SH, Lee TT, Chen CC: A longitudinal examination of a pay-for-performance program for diabetes care: evidence from a natural experiment. Med Care 2012, 50(2):109–116.

31. Sivalal S: Health technology assessment in the Asia Pacific region. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009, 25(Suppl 1):196–201.

32. Kamae I: Value-based approaches to healthcare systems and pharmacoeconomics requirements in Asia: South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Japan. Pharmacoeconomics 2010, 28(10):831–838. 33. Lu C, Lupton C, Rakowsky S, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner A: Patient access

schemes in asia-pacific markets: current experience and future potential. J Pharm Policy Pract 2014. in press.

34. Lu CY, Williams K, Day R, March L, Sansom L, Bertouch J: Access to high cost drugs in Australia. BMJ 2004, 329(7463):415–416.

35. Hall WD, Ward R, Liauw WS, Lu CY, Brien JA: Tailoring access to high cost, genetically targeted drugs. Med J Aust 2005, 182(12):607–608.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges

• Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

• Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit