English Mixing in Cosmetics Ads in

Taiwanese Magazines: Beauty in the Hands

of Copywriters

*Jia-Ling Hsu National Taiwan University

Abstract

This study explores from a sociolinguistic perspective how Taiwanese copywriters respond to the growing impact of globalization on Taiwanese market, via an investigation of the diachronic change from 1999 to 2009 in the use of English mixing in Taiwanese magazine cosmetics ads. Two sets of data are used for quantitative and qualitative analyses: 53 ads are collected from a 1999 English-mixing magazine ads corpus, and 229 ads from a 2009 corpus. This study finds that concerning mixing English in copy design in cosmetics ads, in 1999, local copywriters basically draw or borrow linguistic features from ads of international brands; local bilingual creativity is rather limited. By contrast, in 2009, copywriters not only increase English mixing by recruiting more English nouns, noun phrases, product names, and personal names used for product endorsements and testimonials, but also demonstrate growing bilingual ingenuity by exploiting the device of changing parts of speech and by coining English phrases and sentences, which in turn leads to the arising of nativized English. Additionally, in spite of the variation shown in the occurrences of linguistic categories per ad in ten years, copywriters have shown their consistency regarding the order of preferences for the use of these categories in a decade. That is, nouns and noun phrases are their most preferred

* This paper as part of two research projects was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology (NSC100-2014-H-002-158 and 103-2410-H-002-069). The author is grateful to the two reviewers for their valuable comments which helped improve the manuscript greatly.

choices; conjunctions, prepositions, and adjective phrases are their least preferred choices. Such ordering suggests that linguistic constraints that exist in Chinese are at work against borrowing those least preferred categories. Diachronic investigations are rare in the field of English mixing in advertising. This study showcases how Taiwanese copywriters use English mixing like an art, as a mood enhancer in building up product image and a fantasy world for consumers. It also sheds light on how they adapt their linguistic strategies to targeting Taiwanese consumers while coping with the increasing impact of globalization.

Keywords: English mixing, Taiwanese magazines, cosmetics ads, globalization, diachronic change

1. Introduction

English as “the single most important language of globalization” is the choice of global advertisers and marketers (Bhatia 2006:603). Its influence has dominated advertising discourse in many areas such as cosmetics. It even infiltrates into perfume and cosmetics ads in France, of which the products are deemed as superior by French speakers (Martin 2002a:382). While “magazine... advertisers adopt a ‘technology of enchantment’” as a way to control their readers... and advertising language is infused with “magical power” (Moeran 2010:492), how do advertisers in Taiwan, a non-Anglophone country, use English to create this process of enchantment in cosmetics ads in an era of globalization? As globalization deepens, how do Taiwanese advertisers change their linguistic strategies of using English in cosmetics ads over a decade to respond to its impact? In other words, this research attempts to examine from a sociolinguistic perspective the diachronic change from 1999 to 2009 in the use

of English mixing in Taiwanese magazine cosmetics ads, by analyzing the linguistic features of the English-mixing occurrences, quantitatively and qualitatively.

With regard to studies pertinent to the issues probed in this research, namely, the influence of globalization on English mixing in advertising, the use of English language in cosmetics ads, and the diachronic change in English mixing in advertising, six works are reviewed. On the impact of globalization on English mixing in advertising, two comprehensive studies have been conducted (Martin 2006, Bhatia and Ritchie 2013). Bhatia and Ritchie (2013) provides a wide-ranging overview concerning the influence of globalization on bilingualism in global advertising. He explores the issues of globalization and international advertising, typology of the global spread of English and language mixing, socio-psychological features of English-mixing, structural domains accessible to English mixing, globalization and marketization of English, linguistic creativity and language change, and linguistic accommodation and advertisers’ perception. He concludes that multiple mixing of languages and scripts features global advertising. While English is homogenizing the global advertising discourse, it is also being transformed into diversified varieties, whose role can be best characterized as “glocal” (Bhatia and Ritchie 2013:543). The glocalization of English has prompted mixing of English with other languages in advertising worldwide, and has changed and will continue to change the quantitative and qualitative patterns of English usage in global advertising.

Martin (2006) investigates qualitatively how globalization and the spread of English have affected French advertisers’ strategies of employing textual and visual components in ads while targeting French consumers. Her corpus of data includes 2930 TV commercials, 3695 magazine ads, and 20 hours of taped interviews with advertisers. She analyzes advertising practices, social trends, America imagery, and both the advertising industry’s and the government’s

reactions to the spread of English. The results indicate that English and global imagery play accessible roles for global campaigns to tap into French market. While English serves as a global language in international campaigns, it also serves as “a locally brewed variety” in French market, where English has been transformed by the general public and copywriters, who exploit code-mixing in slogans, puns, and other linguistic devices to achieve various special effects (Martin 2006:243). Despite the stipulation of Toubon Law, which promotes French-only language use in ads, the use of English mixing in French advertising is not restrained.

The above two studies are of huge scope, exploring the influence of globalization on a wide range of issues in global advertising and French advertising respectively on a grand scale. Though they do not focus on cosmetics ads, some of their observations tie in with the generalizations obtained in the present study, thus validating the results of this research.

English language use in cosmetics ads are studied by Czerpa (2005), Sun (2011), and Bulawka (2006). Czerpa (2005) devotes part of her thesis to comparing qualitatively the metaphors in cosmetics ads in the English and the Swedish editions of Elle. The research findings indicate that the English edition of Elle highlights the metaphors of pleasure while the Swedish edition focuses on the effectiveness of advertised products. Sun (2011) probes how print advertising vs. online shopping media influences the presentation of visual components such as photographic product portrayal and verbal information cue types in cosmetics ads. Her data are drawn from 180 cosmetics ads in four English female fashion magazines and 156 ads from English Yahoo! Online

Shopping Mall. It is found that print cosmetics ads are more visual-oriented,

focusing on endorsements for brand products via a high presence of photographic people portrayal, whereas online ads are more commercial-oriented, emphasizing utilitarian information such as products’ retail price.

mixing in Polish advertising, by analyzing 235 ads collected from 13 magazines. The results show that cosmetics, clothes, and mobile phones are the most common product domains where English mixing occurs. In cosmetics ads, English mixing is used in product naming and also occurs in technical terms to conjure up connotations of professionalism.

A review of the above three theses indicates that though all these works draw data from cosmetics ads, their focuses are different from that of the present research. While Czerpa (2005) concentrates on the comparison of metaphors appearing in ads collected from a magazine in bilingual editions, English and Swedish, Sun (2011) compares presentations of visual components in ads collected from monolingual English media. Neither of these studies tackles the use of English mixing as a linguistic strategy in cosmetics ads. Although English mixing in cosmetics ads is addressed by Bulawka (2006), it is slightly touched on, including a two-page discussion with only a few examples listed, not substantiated by any in-depth analysis.

As regards diachronic research on English mixing in advertising, Ruellot (2011) conducts a diachronic and quantitative analysis of the use of English terms in French print advertising from 1999 to 2007, with data drawn from 594 ads from 40 magazines. The results assert that in spite of France's language laws intended for restricting the use of English in French advertising, the positive associations with English symbolizing technological advance, reliability, business efficiency, and sophistication have increased over a period of eight years. The recruitment of English, standing no longer primarily for Anglophone cultures, suggests that English used in French print advertising has become a lingua franca, which allows French advertisers to conduct cultural and business exchanges with the world.

The above literature review indicates that among all the works reviewed, Ruellot (2011) shares a research goal similar to that of this research, i.e., to investigate the quantitative diachronic change of English mixing in magazine

advertising. However, compared with the present study, her research is different in focus and smaller in scope. That is, her study centers on the cultural and business associations of English by examining only English-mixing terms in ads of general products. The review shows that so far no quantitative and qualitative studies have been administered in terms of the diachronic impact of globalization on copywriters’ linguistic strategies of English mixing in cosmetics ads in a non-Anglophone country. This area of research can shed light on how change of language use in advertising discourse is manifested as a response to the growing trend of globalization.

In sum, via examining quantitatively and qualitatively the diachronic change from 1999 to 2009 regarding the employment of English mixing in Taiwanese magazine cosmetics ads, this research intends to address the following two issues. Firstly, what are the English-mixing strategies exploited by Taiwanese advertisers in creating enchantment technology in cosmetics ads? Secondly, how do Taiwanese advertisers adapt their English-mixing strategies in the copy design of cosmetics ads over a decade to cope with the increasing impact of globalization?

2. Methodology

2.1 Data collection

First of all, working definitions of cosmetics and English mixing are given as follows. Cosmetics are defined in this study as “substances or products used to enhance the appearance or fragrance of the body” (Wikipedia, Cosmetics, 2017-2-10).1 English mixing, following Kachru (1990), is broadly defined as

1 As opposed to personal hygienic items such as shampoo and bath gel, “which are necessities, cosmetics, which are luxury goods, are solely used for beautification” (Wikipedia, Personal Care, 2017-2-10). Cosmetics items in this study include lipstick, mascara, eye shadow, foundation, skin lotions, perfume, cologne, and hairstyling products (gel, mousse, and hair spray), etc. However, when shampoo or facial cleansing products contain beautifying cosmetic components, they are categorized as cosmetics items.

the transfer of English words, phrases, and sentences into Chinese at intersentential and intrasentential levels.

For data analysis, two sets of ads are used, drawn from two corpuses respectively. Table 1 indicates that for the 1999 dataset, 53 ads were drawn from 10 magazines out of a 1999 English-mixing magazine ads corpus consisting of 632 ads collected from 25 magazines, covering a variety of genres such as women, men, travel, and health. For the 2009 dataset, 229 ads were recruited from 27 magazines out of a 2009 English-mixing corpus consisting of 1477 ads collected from 57 magazines, covering ten genres such as men, women, sports, home, and news.2 This corpus was built by following the

sampling criteria and procedures of “The Corpus of Asian Magazine Advertising” proposed by Moody. For methodological details, refer to Moody and Hashim (2009).

Table 1. Sources of ads

1999 corpus (25 magazines, 632 ads) 2009 corpus (57 magazines, 1477ads)

10 magazines 27 magazines

53 ads 229 ads

In terms of the coding scheme, all the Chinese-English-mixed units in ads are entered into the computer.3 Depending on its function in the mixed context,

each English token is assigned a linguistic category, such as lexical, phrasal, or sentential.4

2 Due to the limit of space, the 10 magazines collected from the 1999 corpus such as 俏 麗 情 報 Orient

Beauty No. 13 and 家 庭 月 刊 Families No. 278 as well as the 27 magazines collected from the 2009

corpus such as 薇薇 VIVI No.303 and 壹周刊 Next Magazine No.432 are not listed in this paper. 3 English usage appearing on product labels or involved with brand copyrights, website information,

venues of events, and product distributors is not included in the corpus because these types of information are not concerned with Taiwanese copywriters’ linguistic creativity.

4 Due to the limit of space, examples of each category are not presented in the section of Methodology. They appear as data in the section of Results of Qualitative analysis.

Lexically, proper words and common words are discerned. Proper words include brand (company) names, certification bodies and systems such as FDA, product names, personal names, place names such as Paris, and terms (register used in various product types) including components contained in advertised products such as pitera. Common words cover English letters, nouns (including abbreviations and acronyms), verbs, adjectives, prepositions, adverbs, and conjunctions.5 For phrasal categories, refer to Table 7. Furthermore, additional

information is entered such as whether English tokens contain the device of changing parts of speech.

2.2 Data analysis

The two sets of data are compared and analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. For quantitative analysis, frequency counts, percentage, frequency of linguistic features per ad, and ratios are used.6 Qualitatively, linguistic

categories that show prominent diachronic differences, i.e., more than 15% increase or decrease in their frequency per ad over a decade, are analyzed and compared to highlight the significant change in ten years.

3. Results

3.1 Quantitative analysis

Before I discuss the quantitative differences between the two datasets, the

5 English letters are employed by Taiwanese copywriters as a creative device, serving as terms as in 維他 命 A (Vitamin A), abbreviated nouns as appearing in 3D (dimension), or adjectives such as Q 肌 膚 (resilient skin). In this study, English letters are defined as terms, abbreviated-nouns, and non-adjectives.

6 Because of the different sample size of the 2 datasets, using frequency per ad equalizes the differences in sample size. In addition, ratios of the two datasets are employed, referring to the frequency of linguistic categories per ad in the 1999 dataset divided by the frequency of linguistic categories per ad in the 2009 dataset, to show the diachronic increase or decrease in frequency of linguistic categories per ad.

differentiation in the layout design is to be addressed first, which contributes to the quantitative differences in the distribution of linguistic features over a decade.

3.1.1 Layout Design

As illustrated in Figure 1, the layout of 1999 ads is neat, clean, and typical, generally containing a product name, a product label, and easy-to-identify body copy (descriptive texts), regardless of the country origin of the brand. Additionally, language use is minimal.

Figure 1. Copy design of a Japanese brand in 1999

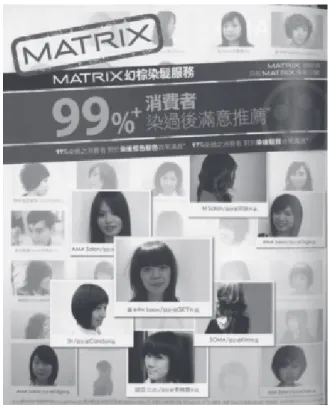

By contrast, in the 2009 corpus, ads are designed like news reports. Copywriters put in several product names, product labels, lengthy product descriptions and product usage instructions, along with celebrities’ endorsements in one copy. Generally speaking, as shown in Figure 2, the copy

design becomes so graphically and linguistically elaborate and sophisticated that body copy becomes massive and is filled with abundant English-mixing information. It is observed that the copy design differences in the two datasets result in the diachronic quantitative differences in the distribution of English-mixing features.

Figure 2. Copy design of a French brand in 2009

3.1.2 Linguistic Categories

3.1.2.1 General categories

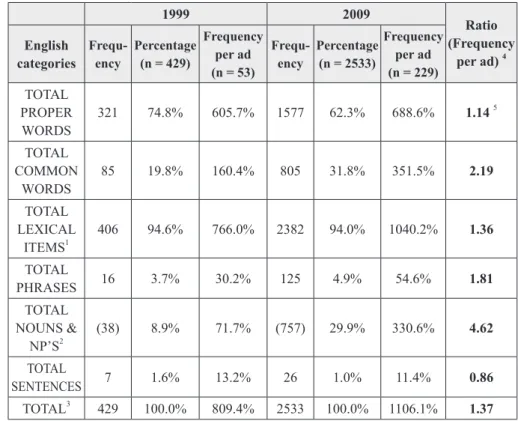

Ratios in boldface in Table 2 show that English mixing increases on lexical and phrasal levels over a decade. The use of common words and phrases doubles, and that of nouns and noun phrases increases 4.6 times. By contrast, English mixing decreases on sentential level to a relatively smaller extent, about

Table 2. Frequency of total linguistic categories 1999 2009 Ratio (Frequency per ad) 4 English

categories Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 429)

Frequency per ad (n = 53) Frequ-ency Percentage (n = 2533) Frequency per ad (n = 229) TOTAL PROPER WORDS 321 74.8% 605.7% 1577 62.3% 688.6% 1.14 5 TOTAL COMMON WORDS 85 19.8% 160.4% 805 31.8% 351.5% 2.19 TOTAL LEXICAL ITEMS1 406 94.6% 766.0% 2382 94.0% 1040.2% 1.36 TOTAL PHRASES 16 3.7% 30.2% 125 4.9% 54.6% 1.81 TOTAL NOUNS & NP’S2 (38) 8.9% 71.7% (757) 29.9% 330.6% 4.62 TOTAL SENTENCES 7 1.6% 13.2% 26 1.0% 11.4% 0.86 TOTAL3 429 100.0% 809.4% 2533 100.0% 1106.1% 1.37 Note:

1 TOTAL LEXICAL ITEMS = TOTAL PROPER WORDS + TOTAL COMMON WORDS 2 TOTAL NOUNS & NOUN PHRASES = TOTAL NOUNS + TOTAL NOUN PHRASES 3 TOTAL = TOTAL LEXICAL ITEMS + TOTAL PHRASES + TOTAL SENTENCES 4 Ratio= the frequency of linguistic features per ad in the 1999 dataset divided by the

frequency of linguistic features per ad in the 2009 dataset

5 When ratios are greater than one, it means that the linguistic categories show an increase per ad in ten years. When ratios are less than one, it means that the linguistic categories show a decrease per ad in ten years.

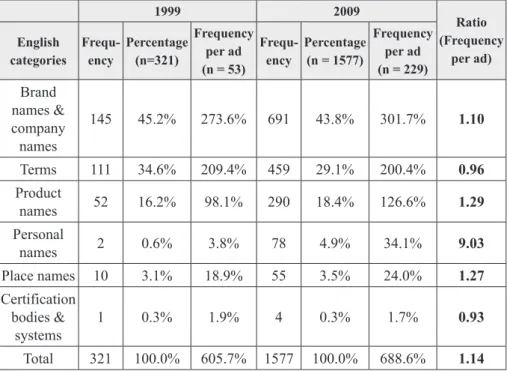

3.1.2.2 Proper words

Table 3 indicates that over a decade, except terms and certification bodies and systems, all the subcategories of proper words show an increase. Particularly, personal names increase nine times over the period.

Table 3. Frequency of English proper words

1999 2009

Ratio (Frequency

per ad) English

categories Frequ-ency Percentage(n=321)

Frequency per ad (n = 53) Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 1577) Frequency per ad (n = 229) Brand names & company names 145 45.2% 273.6% 691 43.8% 301.7% 1.10 Terms 111 34.6% 209.4% 459 29.1% 200.4% 0.96 Product names 52 16.2% 98.1% 290 18.4% 126.6% 1.29 Personal names 2 0.6% 3.8% 78 4.9% 34.1% 9.03 Place names 10 3.1% 18.9% 55 3.5% 24.0% 1.27 Certification bodies & systems 1 0.3% 1.9% 4 0.3% 1.7% 0.93 Total 321 100.0% 605.7% 1577 100.0% 688.6% 1.14

Percentage-wise, subcategories of proper words are ordered in a similar fashion in a decade (Table 4). Such ordering suggests that copywriters’ priorities or preferences for using these subcategories are made in a like manner in ten years.

Table 4. Ranking of English proper words

Rank 1999 2009

1 Brand names & company names Brand names & company names

2 Terms Terms

3 Product names Product names

4 Place names Personal names

5 Personal names Place names

6 Certification bodies and systems Certification bodies and systems

3.1.2.3 Common words

The ratios in Table 5 indicate that among common words, nouns increase almost six times, which is the only subcategory that shows an increase. Percentage-wise, nouns expand from 30% to 80% in the category of common words. On the other hand, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions occur less than five times consistently in the two datasets, suggesting language constraints that do not allow these English categories to be easily assimilated into Chinese.

Table 5. Frequency of English common words

1999 2009

Ratio (Frequency

per ad) English

categories Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 85)

Frequency per ad (n = 53) Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 805) Frequency per ad (n = 229) Nouns 26 30.6% 49.1% 650 80.7% 283.8% 5.79 Adjectives 26 30.6% 49.1% 71 8.8% 31.0% 0.63 Letters 22 25.9% 41.5% 48 6.0% 21.0% 0.51 Verbs 10 11.8% 18.9% 26 3.2% 11.4% 0.60 Adverbs 0 0.0% 0.0% 5 0.6% 2.2% -Prepositions 1 1.2% 1.9% 4 0.5% 1.7% 0.93 Conjunctions 0 0.0% 0.0% 1 0.1% 0.4% -Total 85 100.0% 160.4% 805 100.0% 351.5% 2.19

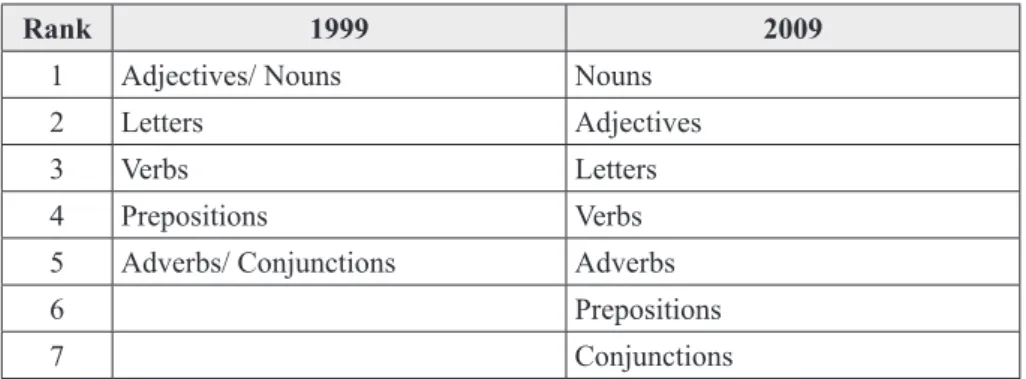

Table 6 shows that percentage-wise, subcategories of common words in these two datasets are ordered similarly to a large extent. Namely, nouns, adjectives, verbs, and letters appear in the top four positions whereas adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions remain in the bottom three positions. Such ranking once again indicates copywriters’ consistent order of preferences for the employment of these subcategories.

Table 6. Ranking of English common words

Rank 1999 2009

1 Adjectives/ Nouns Nouns

2 Letters Adjectives

3 Verbs Letters

4 Prepositions Verbs

5 Adverbs/ Conjunctions Adverbs

6 Prepositions

7 Conjunctions

3.1.2.4 Phrases

Table 7 indicates that noun phrases double over a decade. On the contrary, prepositional phrases, adjective phrases, and verb phrases occur less than 8 times consistently in the two datasets. In particular, there is no occurrences of adverbial phrases and infinitive phrases, suggesting another piece of evidence of language constraints that inhibit the mixing of these English components into Chinese structure.

Table 7. Frequency of English phrases 1999 2009 Ratio (Frequency per ad) English

categories Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 16)

Frequency per ad (n = 53) Frequ-ency Percentage(n = 125) Frequency per ad (n = 229) Noun phrases 12 75.0% 22.6% 107 85.6% 46.7% 2.06 Preposition phrases 3 18.8% 5.7% 8 6.4% 3.5% 0.62 Adjective phrases 1 6.3% 1.9% 5 4.0% 2.2% 1.16 Verb phrases 0 0.0% 0.0% 3 2.4% 1.3% - Present participial phrases 0 0.0% 0.0% 2 1.6% 0.9% -Adverbial phrases 0 0.0% 0.0% 0 0.0% 0.0% -Infinitive phrases 0 0.0% 0.0% 0 0.0% 0.0% -Total 16 100.0% 30.2% 125 100.0% 54.6% 1.81

Percentage-wise, once again, these phrases are ordered in a like manner in a decade, where the top three subcategories are exactly the same and the bottom four are ranked similarly as shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Ranking of English phrases in ads

Rank 1999 2009

1 Noun phrases Noun phrases

2 Preposition phrases Preposition phrases

3 Adjective phrases Adjective phrases

4 Verb phrases/ Present participial phrases/ Adverbial phrases/ Infinitive phrases Verb phrases

5 Present participial phrases

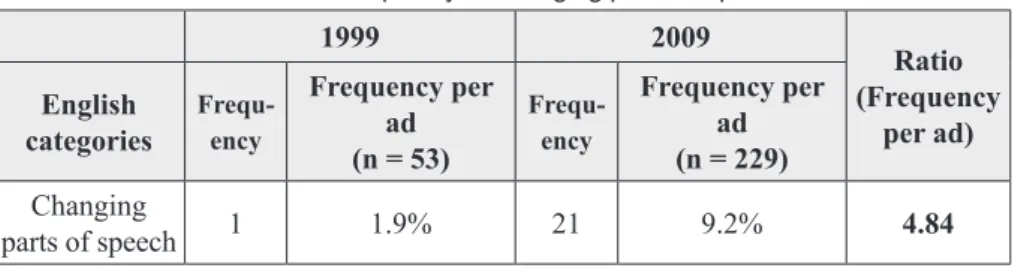

3.1.2.5 Changing parts of speech

Other than the above linguistic categories, copywriters also exploit a tactic of changing parts of speech, which increases almost five times in a decade (Table 9).

Table 9. Frequency of changing parts of speech

1999 2009

Ratio (Frequency

per ad) English

categories Frequ-ency

Frequency per ad (n = 53) Frequ-ency Frequency per ad (n = 229) Changing parts of speech 1 1.9% 21 9.2% 4.84

To conclude, the above analysis indicates that to respond to the growing impact of globalization on Taiwanese market, Taiwanese copywriters increase the mixing of English in Chinese-based advertising copy by recruiting more English proper words such as personal names, product names, and place names, as well as nouns and noun phrases after a decade. Another linguistic device that rises over a decade is that of changing parts of speech. Furthermore, the analysis shows that although the occurrences of linguistic categories per ad may vary in a decade, the order of preferences in which copywriters use linguistic categories in copy design is much alike in these ten years. That is, brand names, product names, terms, nouns, and noun phrases are their most favorable choices, whereas adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, verb phrases, and adjective phrases, their least favorable. Such preferences confirm Bhatia’s observation that “in the non-English-speaking world, product naming and company naming is the domain for which English is the most favored language” (Bhaita 2006: 606). On the other hand, the low frequency of prepositions and conjunctions and the absence of adverbial phrases and infinitive phrases suggest that language constraints consistently work against the assimilation of these linguistic categories into Chinese structure.

3.2 Qualitative analysis

Based on the ratios provided in Tables 3, 5, 7 and 9, the linguistic categories that show more than 15% increase or decrease in ten years are analyzed qualitatively in the following sections.

3.2.1. Increasing Categories

The following categories will be discussed based on the descending order of ratios shown in the tables mentioned above.

3.2.1.1 Personal names

In the 1999 dataset, only two names are referred to: Christy, a Maybelline model, and Rausch, the founder of a Switzerland-based shampoo brand, as appearing in “百餘年後:RAUSCH 家族依然堅持以草本哲學經科學實證的 方 式, 發 現 大 自 然 中 珍 貴 草 本 植 物” (After a hundred years, the Rausch family still insist on searching for precious herbs as components of their shampoos).7

By contrast, in 2009, personal names become proliferated, showing a nine-time increase. References made include not only founders, presidents, chief-executive-officers, funders, public relations managers, and cosmetics formulas patent holders of international brands, but also local hairdressers, makeup artists, and many brand ambassadors such as international and local models, Hollywood and Hong Kong movie stars, as well as local TV program hostesses. For example, in “Sisley 全球總裁 Philippe d'Ormano 為 Sisley 品牌 精 神 作 下 最 佳 註 解,” the president of Sisley is referred to for endorsing the

7 The font of English usage presented in all the examples listed in this study is an authentic representation of the font appearing in ads in the datasets. Additionally, in presenting data in this paper, quotation marks are used to mark Chinese-English-mixed texts, Chinese words and phrases, and long English phrases and sentences. Italics marks English vocabulary items and short phrases.

international brand spirit of Sisley. On the other hand, local hairdressers’ names that appear in large quantity as in “畢卡 PH Salon 設計師 SKY 作品” are used to endorse professional quality of service offered by these local dressers (Figure 3). It is observed that when references of names are made, foreigners’ names appear in English only while local celebrities’ names appear in both Chinese and English.

Figure 3. Local hairdressers’ bilingual names appearing in copy design The diachronic analysis indicates that celebrity branding via the employment of English personal names has become a prolific device over a decade, used by local copywriters to promote brand ambassadors’ authority and endorse product quality. Such phenomenon is also observed by Sun (2011) that “testimonials and endorsements” information occurs very often in cosmetics

magazine ads. Such linguistic strategies of using endorsements and testimonials characterize “puffery or evaluative advertising,” which “makes subjective claims that can neither be empirically proved nor disproved” (Bhatia 2006: 611). Throughout this study, it is suggested that copywriters’ making use of English mixing in cosmetics advertising discourse features the strategy of puffery advertising. In sum, personal names used for testimonials and endorsements grow not only in quantity but also in variety over a decade.

3.2.1.2 Nouns

Based on the ratios shown in Table 5, nouns increase almost six times in ten years. In 1999, among the 26 nouns distributed in 8 ads, 77% of them pertain to abbreviations of units of measurement and price, such as g (gram, unit of weight), ml (milligrams), and NT (New Taiwan Dollars, the currency of Taiwan), utilized to deliver information concerning product volume and price, as in “麗白角質亮膚液 160 ml NT 1400.” Other nouns include t-shirt as in “兩 人定作 t-shirt” (two tailored-made t-shirts) as prizes in a prize-drawing contest, and five nouns such as fantasy, siren, brat, delight, and prankster occurring in a Maybelline lipstick ad. In this ad (Figure 4), a total of 30 English lexical items, 5 nouns, 6 verbs, and 19 adjectives, appearing in very fine print, on labels of 30 piled-up lipsticks, are used to show how Maybelline lipsticks of different colors can create various effects. This device is copied from the original Maybelline ad, which shows no local linguistic creativity.

Figure 4. Common nouns such as fantasy appearing in a Maybelline lipsticks ad In 2009, nouns increase in number and in diversity due to three characteristics of copy design. Firstly, as in 1999, copywriters fill the copy with abundant information regarding product volume and price. Therefore, abbreviated nouns such as ml, g, and NT abound, constituting 70.5% of the total nouns, with NT and ml making up 31% of the total usage respectively.

Secondly, copywriters offer elaborate information or instructions concerning how to use advertised skincare or cosmetics products properly. As shown in Figure 5, while descriptions and explanations are given in Chinese, English nouns such as steps, parts, lessons, points, Q’s (an abbreviation for question), and A’s (an abbreviation for answer) flourish as attention-getters. This device occurs 50 times, composing 7.7% of the total noun usage.

Figure 5. Nouns such as steps and Q’s abounding in ads

Thirdly, copywriters mix a variety of nouns for various purposes. Abbreviated nouns such as No. 1 and 3D (dimension) are most popular. 3D takes place 9 times, as in “3D 定位提升輪廓,”to advertise a facial mask which makes women’s facial contour prominent. No.1 occurs 7 times to create the image that advertised products either are of the best quality or have the best sales, as appearing in “日 本&台 灣 狂 銷 No.1” (the best sales in Japan and Taiwan) and ”抗氧化效果 No.1” (the best anti-oxidant effect). Baby is another popular noun occurring 7 times. In the instance of ”一起床臉蛋就白嫩得宛如 新 生 兒 baby 肌,” baby is used to highlight the special effect of skincare products in enabling women to have as fair and soft facial skin as that of a newborn baby. Spa occurs 5 times, as in “全球 SPA 最愛法國雍卡化粧品” (the most favorite spa products of global consumers, YONKA). Look occurs twice, as appearing in “Sexy 女孩的個性 Look” ( having the look of a sexy girl) and “輕鬆打造隋棠的上質美人 LOOK” (One can easily copy the look of

隋棠, a famous Taiwanese model).

Nouns pertaining to product colors and components are also employed by copywriters to show magical product effects: eye shadow colors such as violet, browning hair colors such as cappuccino, and minerals contained in skincare products such as magnesium. One instance shows that if consumers use brown hair coloring products, they can enjoy “Sweetness 甜 美... Sexiness 性 感... Freshness 清 新.” Other nouns mixed in various texts include top, promotion,

day, night, style, scents, party, VIP, test, tips, mask, wax, to name just a few, to

feature guaranteed product quality or product functionality in transforming women’s styles of looks at different hours of a day for various occasions.

To sum up, while mixing English nouns in advertising copy, as shown in both datasets, Taiwanese copywriters primarily exploit the linguistic strategy of “factual advertising... referring to factual claims in a real-world situation, like pricing, packing, and product attributes” (Bhatia 2006:611). Consequently, abbreviated nouns concerning product volume and price flourish in both datasets, accounting for more than 70% of the total noun usage. However, this strategy of mixing provides easy access to proliferation of English mixing since copywriters can effortlessly replicate such device.

As regards the remaining 30% of nouns in the datasets, unlike the limited devices observed in 1999, linguistic strategies witnessed in 2009 are expanded in diversity. A variety of nouns are exploited mainly for two purposes: to create an ambiance of user-friendliness and to contribute to building up product quality and image as an effort to convince consumers that their outlooks can be transformed with the help of advertised products.

3.2.1.3 Changing parts of speech

In 1999, only one instance of changing parts of speech of English words is noted: “即使過了 N 個生日,妳還是有辦法讓自己成為看不出年齡的女 人.” In this example, the English letter N, a noun, serving as an adjective,

meaning “no matter how many,” is used to promote an anti-wrinkle lotion. The whole sentence reads: “Regardless of the number of birthdays you have celebrated, as long as you use this advertised lotion, no trace of aging is to be left on your face.”

In 2009, this device shows a five-time increase, consisting of four types of usage. First, adverbs such as up, down, and out function as verbs: up means to increase; out means to go away or to be removed; down means to decrease. For example, in an ad promoting facial whitening lotion, such an expression as “暗 沉肌 Out!...保濕度激增! UP” suggests that women’s dark skin will be removed and the skin-moisturizing effect will be enhanced. In another ad promoting Mod’s hair styling mousse, the line “mod's hair Down 無燥感” can be literally translated as “using the styling mousse helps to decrease dryness of hair.” Of the three adverbs functioning as verbs in the ads, down is used once, out twice, and up six times, rendering up the most popular device.

Secondly, homophones are used as shown in the eyeshadow ad “魔法玻瑰 耀眼 FUN 電.”In this example, the adjective fun serves as a near homophone of “放” (fang), a verb in Chinese; “放 電”means to captivate. This expression is translated as “via the use of advertised eyeshadow, one’s eyes become captivating.”

Thirdly, product names are employed for wordplay. In the instance of “Pretty 綻放花漾香水……恣意綻放你的 Pretty,” the first pretty is the product name of the advertised perfume while the second one, seemingly an adjective, functions as a noun, meaning prettiness. The whole expression reads: “With the perfume of Pretty, women’s prettiness radiates.” In another instance of “OUTDOOR 外出 Bee 備草本防護系列 and Bee 暑酷涼, ” Bee is part of a skin ointments brand name, Burt’s Bees. Bee serves as homophones of two Chinese verbs, “必” (must) and “避” (avoid). “Bee 備” is an equivalent of ”必 備” (must have), and “Bee 暑,” an equivalent of “避 暑” (to avoid summer heat). The advertising line reads: “Burt’s Bees’ ointments are must-haves for

outdoor events and for avoiding summer heat.” Bilingual wordplay such as puns is also observed in Italian advertising, where English and Italian are employed creatively for attention-getting and for fun (Vettorel 2013:270).

Fourthly, the English letter Q is borrowed to represent the pronunciation of a word copied from Southern Min Dialect, a local dialect. This word, meaning chewiness of food, serves as an adjective to refer to resilience of skin, as in “Q 彈潤澤肌” (Women’s skin can be resilient, smooth, moist, and lustrous). This letter is even replicated as QQ as in ”輕鬆創造彈力 QQ 肌” to accentuate an extra degree of skin resilience (Figure 6). Five occurrences of Q and two occurrences of QQ are found in this category of device.

Figure 6. The replicated use of Q as an adjective

The instances provided in this part of analysis demonstrate Taiwanese copywriters’ bilingual creativity in using English by changing its parts of speech. This strategy is employed to boost the magical effects of skincare and cosmetics products that “UP” (upgrade) consumers’ appearance.

3.2.1.4 Noun phrases

Among the 12 noun phrases found in the 1999 dataset, 10 of them do not display local creativity, including signature lines of international brands, phrases copied from original international ads, and local shop names of an international brand.8

Only two phrases show local ingenuity. Happy birthday is used in “Happy birthdays……年齡對妳而言只是一個參考數據……生日快樂!即使過了 N

個生日,妳還是有辦法讓自己成為看不出年齡的女人!” (Happy birthdays,

no matter how many birthdays you have celebrated, your age cannot be told) to highlight the special product effects in maintaining women’s forever-young appearance. Another usage is new open, to refer to the new opening of a department store outlet. Though grammatically mistaken, this expression is very popular in Taiwan.

In 2009, noun phrases double in number. They are used in two ways. First, 34% of noun phrases pertain to signatures lines of international brands and phrases copied from imported ads.

The remaining two thirds of the noun phrases demonstrate local ingenuity: expressions referring to product items such as Item Used, KEY ITEM, and Hair

Care ITEMS; hair and powder coloring terms such as Nude Ivory; and hairdo

styles such as military curl and knight wave (Figure 7). In addition, expressions related to solutions to skincare problems are popular; Q&A, easy steps, night

care check, daytime care check, lip problem, and lip solution are some

examples. Noun phrases placed at the top of layout or descriptive texts are made use of to call for readers’ attention to product descriptions or brand ambassadors’ testimonials, for example, Women's Beauty Talk, Beauty & Skin

8 A signature line is defined as a single phrase appearing in relatively small print immediately following the company name and logo (Martin 1998:237).

(talk), BEAUTY PROMOTION, Beauty News, and marie claire PROMOTIAON

(sic).

Figure 7. Noun phrases such as military curl and knight wave appearing in an ad

marketing hair styling products

Other phrases such as Nobel Prizes, the Honor of Awards, Special Offer, and Best Sell (sic) warrant supreme quality or the most favorable price of advertised products. On the other hand, modern chic, spot light, party queen, and the wonderful life contribute to the ambiance of building up a fantasy world via the use of advertised products. Among these phrases, all-in-one is most prolific, occurring five times, used to emphasize the special effect that one product can yield the combined effects of several products, which helps to save money and time for consumers.

What’s noteworthy is that in mixing English in Chinese-based copy, possessive cases are rarely used. However, in the 2009 dataset, one occurrence

of this usage is observed, as in “A-mei’s secret” (the secret of A-mei, a famous singer in Taiwan), indicating that copywriters follow English grammatical rules in creating this phrase, an unusual phenomenon in contrast with the many locally produced expressions teeming with grammatical errors.

In short, in ten years, the usage of noun phrases flourishes, demonstrating the bilingual creativity of local copywriters and the trend of fashion.

3.2.1.5 Product names

Product naming is “the most favorite and most easily accessible domains to English,” other than company naming (Bhatia and Ritchie 2013:579). Generally speaking, in exploiting English in naming cosmetics products, Taiwanese copywriters recruit the following strategies in both datasets. Firstly, they copy monolingual English product names. Secondly, they use bilingual versions of product names, placed side by side in body copy, such as “SOFINA WHITENING CLEAR EX 蘇 菲 娜 美 白 菁 華 霜.” Thirdly, they use English mixing in naming products. Several subtypes emerge.

In some cases, they copy English brand names, which appear in the beginning of the original English product names, then add Chinese descriptions of cosmetic effects of products, and lastly mix Chinese translations of product types, which are the remaining parts of the original names. Examples are listed in Table 10, which show that ”緊容小臉” (skin-tightening and face-thinning) and “放電誘唇” (captivating and seducing lips) are the descriptions of cosmetic effects added by copywriters.

Table 10. English-mixing product names beginning with English brand names

contained in original English product names

English-mixing product names Original English product names ORIKS V-LINE 緊容小臉 BB 霜 ORIKS V-LINE B.B. Cream

In other cases, copywriters copy some key words from original product names. Some examples are listed in Table 11. These instances indicate that besides copying some key words from the English product names, such as UV (ultraviolet), BB (blemish balm), and simply SPF20 PA+++ (Sun Protection Factor and Protection Grade of UVA rays), copywriters also add their own descriptions of magical product effects, for instance, “無瑕淨化” (spotless and purifying). Sometimes, they copy just one English word from the original names, as shown by the fourth example, where up as in Wave-Up is copied.

Table 11. English-mixing product names copying key words from

original English product names

English-mixing product names Original English product names 新一代礦物 UV 隔離露

SPF40 PA+++ UV Plus Day Screen High Protection SPF 40 PA+++ 無瑕淨化防曬 BB 霜 SPF 28 PA++ Genius Blemish Balm cream SPF 28 PA++

極透瞬白防護日霜 SPF20 PA+++ Bi-White Reveal DUAL-ACTIVE EXPRESS WHITENING CREAM SPF 20 PA+++

莉婕 捲度 UP 慕絲 Liese Wave-Up Foam

Additionally, copywriters sometimes mix English wording not even present in original English product names. An instance is listed in Table 12. This example shows that the Chinese product name ends with terms such as

SPF 12 PA++ not appearing in the original product name, in order to warrant

product quality.

Table 12. English-mixing product names containing no information of

original English product names

English-Mixing product names Original English product names 雅漾溫和輕透粉底液 SPF12 PA++ Avene Skincare liquid foundation

A comparison of the two datasets shows that in 1999, in the copy design, usually one product name is advertised per ad. Bilingual version of product names (58.1%) is the most common type, followed by English-mixing product

names (25.8%) and monolingual English product names (16.1%). Furthermore, product names ending with English sun-protection terms such as SPF15 are few in the data, with only two occurrences (6.5%).

On the contrary, in 2009, copywriters favor mixing English in naming products and put in several product names alongside product labels in one single copy. In consequence, the types of English-mixing names as shown in Tables 10 to 12 proliferate, constituting 63.2% of total advertised product names, followed by bilingual version of product names (22.6%) and monolingual English product names (14.2%). Chinese product names ending with sunscreen terms such as UV, SPF, and PA+++ become very popular, making up 17.4% of product names, suggesting a new trend of naming practice. In sum, product naming with English mixing becomes very productive after a decade.

3.2.1.6 Place names

In 1999, only three place names are referred to in the data, Paris (six times), New York (three times), and Tokyo (once).They all pertain to signature lines of international brands, showing country origins of products.Since all these references of place names come with logos of international brands, no creative use of place names by local copywriters is witnessed in the 1999 dataset.

In contrast, in the 2009 dataset, although the majority of place names occur in signatures lines of international brands, local copywriters’ creative use of place names is observed in descriptive texts. In terms of signature lines of international brands, Paris is still the most prominent city referred to for 31 times, accounting for 50 percent of the place references. Italy comes second (five times); New York occurs three times; Switzerland and Tokyo occur twice respectively; California, once.

Table 13. The first example shows that references of Swiss place names are made to create an atmosphere that the cosmetics brand Helenere, of which the headquarters is located in Switzerland, is prestigious. In the second example,

Hunza, a mountainous valley in the Gilgit–Baltistan region of Pakistan, is

mentioned to show that the advertised product contains a mystic skin moisturizing component drawn from the glaciers in this area, of which the glacier water contributes to local residents’ longevity. The third example makes reference to Mazama, Washington, to highlight the enchanting skincare effects of the advertised product, which contains a magical ingredient drawn from this area.

Table 13. Advertising texts containing English place names

MONTREUX 蒙特勒,座落於 ALPS 阿爾卑斯山山腳,面向湖水澄清的 LAKE LEMEN 瑞士蕾夢湖,這地區就是舉世聞名的 SWISS RIVIERA 瑞士里維拉

區,瑞士賀蘭妮化妝品總部即設於此.

LANEÍGE 蘭芝冰河能量水系列富含喜馬拉雅「冰河水精萃專利配方」…這不

僅是喜馬拉雅上山罕薩 (Hunza)居民平均年齡高達 120-140 歲的長壽奧秘,也

是 LANEÍGE 蘭芝打造自然健康美肌的養生秘密

來自於馬茲曼(Mazama)的珍稀冰山翠湖 Lana blue,生長在 1300 公尺純淨無

污染的海拔環境,含有特殊礦物質和營養成分,富含天然肌膚促生因,可以 平滑,緊膚,小臉。

As illustrated above, compared with the increase shown in personal names in 2009, a full demonstration of local copywriters’ ingenuity, this part of analysis indicates that the increase of place names is mainly attributable to the growing references of place names appearing in signature lines, coming with logos of international brands. Such references, signaling origins of products, such as Paris and New York, function to accentuate the prestige and authenticity of products made in these global fashion capitals. On the other hand, local copywriters make references to not-so-well-known place names in body copy to endorse the authenticity of product ingredient sources, such as Hunza, where the glacier water is said to generate a mystic power in moisturizing women’s

skin. Both devices are utilized to convince audience that advertised products guarantee not only authenticity and quality but also magical formulas that can revive their skin and rejuvenate their outlooks.

In sum, the expansion of place names suggests that product endorsements via the use of place names, collaborative efforts made by both international and local copywriters, become more diversified after a decade.

3.2.2. Decreasing Categories

The following sessions address the categories of which the frequency per ad has diminished over a decade.

3.2.2.1 Letters

In 1999, 22 instances of using English letters occur in only three ads. In the first instance of “uno 潔淨面膜-T 字部位適用”(Uno cleansing masks are designed for the T-area), T stands for the shape of the facial area from forehead to mouth. The second example W serves as a background visual for an international brand name WHITIA. As for the other 20 letters, i.e., 91% of the letters in the dataset, are concentrated in one ad marketing hair styling products, of which the descriptive text is listed as follows: “「髮線」創造「髮型」 I C S W 你找到了自己的髮線嗎?……直線到底的 I 線條……LAVENUS I 直 爽髮霧……運用「I 髮線」……造型你的直順 I 髮線……層次分明的 C 線 條……LAVENUS C 層次髮雕……運用「C 髮線」創造層次……抓出你的 層次 C 髮線……自然輕柔的 S 線條……LAVENUS S 柔度慕絲……運用 「S 髮線」創造輕柔……吹整你的輕柔 S 髮線……波浪明顯的 W 線…… LAVENUS 保濕乳液……運用「W 髮線」創造波浪..保濕你的 W 極捲髮 線,性感又俏皮,讓女人的壞,更壞” as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. English letters ICSW refering to waves of women’s hairdos

In this ad, copywriters mix four English letters ICSW not only in product names such as “LAVENUS I 直 爽 髮,” in background visuals, but also in descriptive texts, where these four letters are repeatedly used to stand for the shapes of four types of hairlines and hairdos, namely, I for straight, C for curly,

S for soft, and W for wavelike. This ad convinces women that by capitalizing on

four different hairstyling products, women can create 4 types of hairdos depending on what type of hairlines they possess. Though this ad displays copywriters’ bilingual creativity in using English letters, it also shows that English letters in the 1999 dataset are mainly confined to one ad.

On the contrary, in 2009, the usage of English letters is scattered in various ads for a variety of functions. Other than serving as pure letters such as ABCD as sets of options for multiple-choice questions in a survey type of ad, English letters are exploited to stand for various shapes. For example, V refers to the V-shaped face in ”李 倩 蓉 的 V 型 小 臉 蛋” (Ms. Li, Qian-Rong’s V-shaped face) and a type of wearing make-up as in “V 型 上 妝 手 法” (do a V-shaped make-up). Z stands for the shape of the comb teeth of a mascara as in ”防汗 Z

字震動睫毛膏……Z 字震動刷頭.” As in 1999, T describes the shape of the facial area from forehead to mouth as appearing in ”針對 T 字出油” (a facial cleanser that deals with men’s oily facial area from forehead to nose). C and W describe the wave of women’s hairdos, namely, C and W wave of curly hair, as appearing in “髮尾自然鬆散開來的 W 型立體捲髮……自然蓬鬆的 C 型捲 髮 絕 對 是 今 年 流 行 的 潮 髮 趨 勢” (W-wave and C-wave of curly hair are definitely the new black this year) as advertised by a hair salon. X is used as a graphic representation of the meaning of times as in “5X 極致濃蜜”(a mascara that can make women’s eyelashes 5 times lusher).

Additionally, English letters serve as homophones of Chinese words. For example, in the advertising line of a skincare product, “e 網打盡肌膚男題…… 肌膚問題 e 次搞定,” e is a homophone of “一” (yi), number one in Chinese. Via the use of the English letter e as an attention-getter, both phrases, “e 網打 盡”and “e 次搞定,” convey the advertising message that to cure men’s difficult skin problems, the advertised product can offer the ultimate solutions once and for all.

Lastly, English letters function as abbreviations of English words such as 3

R in “3R 保濕新概念”(the new 3R concept for moisturizing women’s skin),

where 3 R stands for“RECHARGE 升級鎖水 RETIGHI 緊實毛孔 REFRESH 淨化清潔” as appearing in the descriptive text.

In sum, although English letters show higher frequency per ad in the 1999 dataset, letters in this dataset are mainly limited to one ad. By contrast, more innovating and varied usage of English letters scattered in various ads appears in 2009, used to highlight beautification effects on consumers in ads of skincare, facial care, and hairdos products.

3.2.2.2 Adjectives

Like English letters, though adjectives show more occurrences per ad in the 1999 dataset, the adjectives observed in 1999 are primarily concentrated in

one ad. Namely, 19 out of 26 adjectives, i.e., 73% of the total adjectives, occur in one ad. These 19 adjectives such as witty, feisty, adoring, girlie, forbidden,

dreamy, delicious, saucy, devoted, fearless, frolic, and delicate all appear on the

labels of Maybelline lipsticks as previously shown in Figure 4. They are used to describe the various effects created by different lipstick colors.

Local devices include the employment of the word new, which occurs four times, placed on top of product names or product labels, serving as an attention-getting device for newly marketed products. In other words, the use of new serves not only as a graphic design for attention-getting but also as a device for highlighting the novelty of advertised products.

In 2009, new becomes proliferated. That is, among the 71 adjectives found in the data, new occurs 44 times, constituting 62% of the total usage of adjectives (Figure 9). They are placed close to product labels or product names. The next popular device involves five occurrences of Q and two occurrences of

QQ, to refer to skin resilience, as discussed in section 3.2.1.3. Free appears

three times in ads offering free gifts. Other adjectives such as juicy, beautiful, and sexy appear in ”肌 膚 自 然 水 嫩 又 juicy…… 美 人 當 然 Q sexy” (When women’s skin is juicy and resilient, women naturally become sexy). In this instance, juicy is used non-natively, which can only refer to non-animate objects and not to humans. Moreover, best and easy are employed in the offering of skincare solutions, as in ”找出 BEST 美白對策” (to find the best treatments for skin whitening) and “保 養 可 以 很 easy” (Skin care can be very easy). One interesting usage worth noting is the possessive case of men as in “Men's 運動 防曬乳液” (men’s sport sunscreen lotion), a rare usage employed by Taiwanese copywriters, where English grammatical rules are observed.

Figure 9. New abounding in cosmetics ads

In sum, a comparison of the two datasets shows that copywriters come up with more local innovations in 2009, and the most dominating device is the widespread use of new, composing three fifths of the total usage of adjectives in the 2009 dataset. This adjective serves as an iconic graphic symbol to constantly remind consumers that “new is always the new black”—a canon in marketing cosmetics.

3.2.2.3 Verbs

In 1999, among the 10 verbs observed in the data, 6 of them (crush,

seduce, tempt, desire, wink, and delight) appear on the Maybelline lipsticks

labels as previously shown in Figure 4. The other 4 verbs involve the local use of one word, open, as appearing in “10 月 上 旬 OPEN” (opened in the first decade of October), serving to provide information concerning the opening dates of product sales outlets.

By contrast, among the 26 verbs found in 2009, only 6 of them are not concerned with local innovations, including the 3R verbs discussed in 3.2.2.1 and the three verbs in “1PRIME 2COVER 3FINISH,” referring to the three steps for using advertised makeup products.

Local copywriters’ bilingual creativity falls into two subtypes of usage. One type involves the device of changing parts of speech, including the use of adverbs up, out, and down, and the use of an adjective, fun, all functioning as verbs. This part of information is provided in section 3.2.1.3.

The other subtype involves mixing of verbs to deliver advertising messages as listed in “上質光感肌 SHOW 出耀眼自信” (One’s beautiful skin shows his/ her self-confidence), “update 美 麗 新 訊 息” (an update on the latest beauty news), “search 生化保養” (search for the bio skin care), “錢韋杉 Say” (Miss Qian, Wei-Shan says), and “超 凡 卸 妝 新 體 驗 GET” (get new extraordinary experiences of removing makeup). Unlike other examples listed above, where English verbs mixed with Chinese texts follow the word order of both Chinese and English, get in the last example is placed after the noun phrase it specifies, perhaps merely for attention-getting.

In conclusion, though the frequency of verbs per ad decreases over a decade, more creative and diversified use of verbs has been developed.

3.2.2.4 Sentences

English ads, including one slogan of Cerruti Image, two signature lines of Maybelline, and three sentences copied from an original Shiseido ad. The only sentence created locally is a proverb as appearing in “儘管西洋俗諺云: Beauty is but skin deep (美麗只是像皮膚一般膚淺),卻有不少女性為了這層薄薄 的肌膚大費周章” (Although beauty is but skin deep, many women would go through all the trouble to search for the best skincare treatments), serving as a statement in contrast to women’s aspiration for beautifying themselves.

In 2009, among the 26 sentences observed in the data, half of them come from original ads of international brands: seven signature lines, three slogans, and three sentences copied from original texts. The other half are mainly created by local copywriters. However, most of them contain grammatical and collocational errors. Examples are listed as follows. The first instance appears in “miss SHARK 找到了突破性的美白策略……我是小白鯊,I am miss SHARK,white not? miss SHARK 年度代言人國際名模 AKEMI 香月明美 衷心推薦” (The brand miss Shark has come up with a breakthrough solution to skin whitening; I am miss SHARK, white not? AKEMI, the brand ambassador, recommends this brand). In the above text, the meaning of the grammatically incorrect phrase white not is not clear. The usage of white in white not may serve as an equivalent meaning of the Chinese word “白” (white) in “小白鯊” (a small white shark), the Chinese brand name of miss SHARK, or “ 白” in the phrase”美 白 策 略” (a solution to skin whitening), to emphasize the skin-whitening effects of products.

The second example “go go go!”, which functions as a morale booster for audience attending a body styling campaign, also contains grammatical errors. As for “You care, I care,” the signature line of a Taiwanese brand of skincare products, a punctuation misusage occurs. Concerning the two collocationally incorrect sentences, “Water Your Skin” and “Revive Your Skin Power,” unlike plants, skin cannot be watered, whereas the phrase of skin power is a nativized coinage, of which the correct version should be Revive Your Skin. The most

evident manifestation of deviation or nativized creativity is the instance of “Skin Power Up” (Figure 10). This device combines the phrase skin power with an adverb up, which functions as a verb and means to increase or boost, as appearing in “美 肌 保 水 機 能 UP” (increase beautification and skin-moisturizing effects). This sentence reads: “Women’s skin can be boosted.”

Figure 10. A nativized English device: Skin Power Up

In short, in contrast to the limited creativity of copywriters who primarily draw sentences from original English ads in 1999, ten years later, local copywriters create their own English sentences, along with drawing signatures lines, slogans, and texts from original ads of international brands. However,

these sentences are teeming with grammatical deviations, which manifest the local creativity in coining nativized English.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study show that in 1999, Taiwanese copywriters mainly draw English features from ads of international brands in their copy design. However, after a decade, as a response to the increasing influence of globalization on Taiwanese market, Taiwanese copywriters adapt their linguistic strategies in two ways. On the one hand, they increase the mixing of English in the categories of personal names, product names, nouns, and noun phrases, as well as in the use of changing parts of speech, by utilizing some easy devices of proliferation of English mixing, such as reduplicating product volume and price to deliver product information, employing abundant personal names for product endorsements and testimonials, and making use of the adjective new repeatedly to imply ‘being trendy.” On the other hand, they demonstrate more bilingual creativity in innovating English usage in all the linguistic categories, including coining English phrases and sentences, which in turn leads to deviation in or nativization of English usage. On such nativized innovations, one copywriter remarks, “since English mixing primarily serves as graphic design for getting attention and creating a desired atmosphere,” full English accuracy is not a concern in her copy design (Hsu 2012:223).

A parallel advertising development is witnessed in France. Ruellot observes that via the study of English-mixing terms in French advertising from 1999 to 2007, the marketing power of English has strengthened and has resulted in “greater bilingual creativity” (2011:5).

Martin asserts that “a more ‘Frenchified’ version of English” is created “to target French consumers as advertising campaigns are adapted or ‘localized’ for the French market” (2008:73). For instance, French advertisers would sometimes hire a musician to write “nonsensical” English-sounding lyrics in

commercial jingles for French advertising campaigns, motivated by the fact that “French audience believe that they are listening to English” (Martin 2002b:13). In other words, the lyrics resembling English in French commercial jingles typically function as “a mood enhancer” and their intelligibility to any audience “does not seem to be an important factor” (Martin 2006:33).

This study suggests that along the same lines of development, Taiwanese advertisers have created a “Taiwanized” version of English to target Taiwanese consumers while coping with the impact of globalization on Taiwanese market.

Additionally, the findings of this diachronic study provide a piece of evidence in support of Bhatia and Ritchie’s observation (2013:567):

... advertising actually promotes bilingualism based in English... By doing so, they (international advertisers) solve the paradox of ‘globalization’ and ‘localization’ in an optimal fashion by following an innovative approach grounded in pluralism.

Lastly, cosmetics advertising features puffery advertising, which “invites the magazine readers to participate in a dream world of fantasy and belief” created by cosmetics and skincare companies (Moeran 2010:501). The growing quantity and variety of English-mixing devices witnessed in 2009 all contribute to the building up of professional, authoritative, persuasive, and convincing product image, quality, functionality, and utility, rendering a sense of physical charm and trendiness to its audience. As commented by Martin (2006:243), via the use of English, a product may be linked to “the glamour of Hollywood or the art of ‘chic’ in the fashion industry.” Consequently, this study validates Bhatia’s observation of the growing leading role of English “in the race of global deception... an increasingly pervasive phenomenon” (2006:611).

References

Bhatia, Tej K. 2006. World Englishes in global advertising. Handbook of World

Englishes, eds by Braj B. Kachru, Yamuna Kachru, and Cecil L. Nelson, 601-619.

Oxford: UK. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.

Bhatia, T. & W. C. Ritchie. 2013. Bilingualism and multilingualism in the global media.

Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism, 2nd Ed, eds. by Bhatia, T. and W.

C. Ritchie, 565-597. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bulawka, Hanna Maria. 2006. English in Polish Advertising. Birmingham: University of Birmingham MA thesis.

Czerpa, Dorota. 2005. Language and Image: A Comparative Study of Advertisements in

English and Swedish Magazines for Adult Women and Teenage Girls. Lulea: Lulea

University of Technology Master thesis.

Hsu, Jia-Ling. 2012. English mixing in residential real estate advertising in Taiwan:

socio-psychological effects and consumers’ attitudes. English in Asian Popular

Culture, eds. by Jamie Shinhee Lee and Andrew Moody, 199-229. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Kachru, B. B. 1990. The Alchemy of English: The Spread, Function, and Models of

Non-native Englishes. Urbana: University of Illinois.

Martin, Elizabeth. 2008. Language-mixing in French print advertising. Journal of

Creative Communications 3.1:49-76.

Martin, Elizabeth. 2006. Marketing Identities through Language: English and Global

Imagery in French Advertising. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Martin, Elizabeth. 2002a. Mixing English in French advertising. World Englishes 21.3: 375-402.

Martin, Elizabeth. 2002b. Cultural images and different varieties of English in French television commercials. English Today 18.4:8-20.

Martin, Elizabeth. 1998. Code-Mixing and Imaging of America in France: The Genre of

Advertising. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

dissertation.

Moeran, Brian. 2010. The portrayal of beauty in women's fashion magazines. Fashion

Theory 14.4:491-510.

Moody, Andrew & Azirah Hashim. 2009. Lexical innovations in the multimodal Corpus of Asian Magazine Advertising. Perspectives in Lexicography: Asia and beyond, eds. by Vincent B.Y. Ooi, Anne Pakir, Ismail S. Talib, and Peter K.W. Tan, 69-86.

Tel Aviv: K Dictionaries LTD.

Sun, Li-Ting (孫立庭). 2011. A Comparative Study of Cosmetic Ads in English Female

Magazine and English Online Shopping Mall. Tao-Yuan: Yuan-Ze University

Master thesis.

Ruellot, Viviane. 2011. English in French print advertising from 1999 to 2007. World

Englishes 30.1:5–20.

Vettorel, Paola. 2013. English in Italian advertising. World Englishes 32.2:261–278. 通訊作者

Jia-Ling Hsu 胥嘉陵

Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University

1 Roosevelt Road, Section 4, Taipei 10617, Taiwan 國立臺灣大學外國語文學系

106 臺北市羅斯福路 4 段 1 號 jlhsu@ntu.edu.tw