行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

新興工業國家之企業創新能力重塑:技術治理與開放創新 的影響

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 99-2410-H-011-030-

執 行 期 間 : 99 年 06 月 01 日至 100 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立臺灣科技大學科技管理研究所

計 畫 主 持 人 : 郭庭魁

計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:李淩芸 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳欣渝

報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文

處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 100 年 10 月 30 日

1

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫 行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫 行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫 X 成果報告成果報告成果報告成果報告

□

□

□

□期中進度報告期中進度報告期中進度報告期中進度報告

新工業國家之企業創新能力重塑:技術治理與開放創新的影響

計畫類別:X 個別型計畫 □整合型計畫 計畫編號:NSC 99-2410-H-011-030

執行期間:99 年 06 月 01 日至 100 年 7 月 31 日 執行機構及系所:台灣科技大學科技管理研究所

計畫主持人:郭庭魁 共同主持人:無

計畫參與人員:李淩芸、蘇莞筑

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):XXXX 精簡報告 □完整報告

本計畫除繳交成果報告外,另須繳交以下出國心得報告:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告 X 出席國際學術會議心得報告

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告

處理方式:除列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢 中 華 民 國 100 年 10 月 31 日

附件一

2

行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫成果報告

新新工業國家之企業創新能力重塑:技術治理與開放創新的影響

Innovation capability Reconfiguration of firms in NIEs:

The role of technological regime and open innovation

計畫編號:NSC 99-2410-H-011-030 執行期限:99 年 6 月 1 日至 100 年 7 月 31 日 主持人:郭庭魁 台灣科技大學 科技管理研所

計畫參與人員:李淩芸、蘇莞筑

摘要

本研究計畫旨在探索在開發中國家,組織創新能 力重組的時後,技術治理以及開放創新對其的影 響及作用,研究架構採用動態能力觀點,特別著 重於組織能力重組的部分,以質化研究的方法,

蒐集在不同產業下,組織發展的經過及創新能力 重組的軌跡,並討論其在不同的技術治理下,組 織如何因應調整創新能力的組合;開放創新對於 組織創新能力的重組有顯著的影響,本研究對於 創新理論在新興工業國家中鮮少著墨之處提出新 的觀點,以實證資料提出理論及實務上的貢獻。

Abstract

This research aims to explore the role and influence of technological regimes and open innovation on firm’s innovation capability reconfiguration in developing countries. The research framework utilizes dynamic capability approach with emphasis on capability reconfiguration. The first phase is to find out the impact of technological regimes on innovation capability reconfiguration. Under different technological regimes, firms in different industries will develop their business and sustain their growth on their own rights. The second phase

will review the role and influence of open innovation practices on innovation capability reconfiguration. The findings would contribute to the development of innovation capability reconfiguration and the dynamic capability approach.

The role of technological regime and open innovation will provide a comprehensive understanding of how firms transform in response to market and technological change. The research findings will also offer new insights on innovation research in developing countries in theory and practice, and offer fresh perspectives on dynamic capability theory, particularly in capability reconfiguration. This can help further dynamic capability research in organization, innovation and strategic management field.

Importance of This Research

In the late 1990s, leading firms in the advanced developing countries of East Asia particularly Korea and Taiwan began to confront a difficult strategic dilemma. Should they attempt to compete with the leading Western firms as R&D, market or brand leaders, or should they continue with the

3

tried and tested formula of low cost competitiveness under the contract manufacturing arrangement? Most scholarly work on innovation focuses upon observations and issues in developed countries, however, studies which deal with the generation of innovation in the context of developing economies are scarce. This research is to answer the above question and make theoretical and practical contribution to innovation research in the context of developing country. Based on prior work 1 on dynamic capability approach, this research will incorporate technological regime and open innovation into the framework to explore the key issues in the industry evolution.

Background and Literature Review Innovation in NIEs

Innovation has different characteristics in newly industrialised economies (NIEs) than it has in developed economies. The unique trajectories of innovation in East Asia present a reversed pattern of product and process innovation. Previous studies provide perspectives on how NIEs can catch up technologically with developed economies, but they offer little advice about how to develop the market and sustain firms’ growth. The need to explore issues of innovation management in newly industrialised countries, such as Korea and Taiwan, is recognised by scholars such as Hobday and Kim (Hobday 1995; Kim 1997; Hobday 2005).

Innovation Capability

Innovation is the mechanism by which organisations produce new products, processes and systems required for adapting to changing markets, technologies and modes of competition (Utterback

1 Prior work refers to my PhD research, which adopts a qualitative, multiple case study approach. A conceptual framework developed from an innovation construct coupled with the dynamic capability approach, provides a lens through which to examine organisational development in a rapidly changing environment. The longitudinal study of these cases guided by the conceptual framework disaggregates innovation capability over time.

1994; Dougherty and Hardy 1996). It is a key business process for success, survival and organisational renewal (Lengnick-Hall 1992; Brown and Eisenhardt 1995). The ability to create and harness the required knowledge and capability is central to the process of innovation (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995).

Broadly speaking, the term “innovation capability”

refers to the ability of a firm to generate innovative outputs. It concerns the specific expertise and competence related to the development and introduction of new products, technologies, and processes (Hagedoorn and Duysters 2002). The concept of innovation capability has not been extensively covered in the innovation literature. It has been variously defined in the literature and as such there is an issue of inconsistent semantics in relation to it. The concept of innovative capability (Moitra 2008), innovative ability, innovative capacity (McGrath 2001), learning capacity (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Child 2003), integrative capacity (Grant 1996) and combinative capacity (Kogut and Zander 1992) all seem to relate to the same concept of innovation capability, relating it to the creation of innovation.

Essentially, innovation capability is concerned with the production of innovation (Schoonhoven, Eisenhardt et al. 1990). Innovation capability is a multidimensional concept composed of reinforcing capabilities, processes and practices within a firm (Ravichandran 2000). It is regarded as being an integration capability to mould and manage multiple capabilities, and to continuously transform knowledge and ideas into new products, processes, and systems for the benefit of the firm and its stakeholders (Kanter 1989; Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Henderson and Clark 1990; Lawson and Samson 2001).

4

Innovation capability is a special asset for a firm. It is tacit, therefore hard to modify, and correlated closely with interior experiences and experimental acquirement. The ability to rapidly introduce new products and adopt new processes has become an important facet of competition. A wide variety of assets, resources, and capabilities are required to make such innovation successful (Sen and Egelhoff 2000). Parashar and Singh (2005) propose a model identifying the component capabilities of innovation as being knowledge, attitude and creativity. They argue that organisations need to have a combination of these basic capabilities and that focusing on one or the other may cause damage to the innovation capability of the organisation rather than creating it.

Capabilities can be distinguished based upon the type of knowledge they contain (Verona 1999).

Functional capabilities allow a firm to develop its technical knowledge (Prahalad and Hamel 1990;

Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Pisano 1997).

Integrative capabilities allow firms to absorb knowledge from external sources and blend the different technical competences developed in various units within the organisation (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Henderson and Clark 1990; Kogut and Zander 1992; Grant 1996). Therefore, innovation capability is proposed to be a higher order integration capability, the ability to mould and manage multiple capabilities (Fuchs, Mifflin et al.

2000). Organisations possessing innovation capability have the ability to integrate key capabilities and resources of their firm to successfully stimulate innovation (Lawson and Samson 2001).

Resource-Based View and Dynamic Capability A dominant framework in the strategy literature addresses the question: ‘why do firms in the same industry perform differently?’ (Zott 2003) Penrose (1959) presents a resource approach arguing that

firms are administrative organisations and collections of physical, human and intangible assets.

The resource-based view (RBV)2 characterises the firm as a collection of resources and capabilities rather than a set of product-market positions (Wernerfelt 1984). The resource-based view proposes that sustained competitive advantage is derived from possessing a set of unique resources which allows firms to capture new monopoly positions in their market (Prahalad and Hamel 1990).

Applying a resource-based perspective to firms helps to identify unique and strategic capabilities, as well as illustrating how these capabilities can evolve inside the firm, their complexity, and their relationship to the firm’s competitive advantage (Coates and McDermott 2002). Firms in the same industry perform differently because firms differ in terms of the resources and capabilities they control (Penrose 1959; Wernerfelt 1984; Barney 1986; Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Peteraf 1993).

Scholars extend the resource-based view of the firm to the dynamic markets, providing an adequate explanation of how and why certain firms have competitive advantage in situations of rapid and unpredictable change (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997;

Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). For instance, Henderson and Cockburn (1994) propose that architectural competence in the pharmaceutical industry and a firm’s ability to integrate knowledge from external sources are positively associated with research productivity. Iansiti and Clark (1994) identify the integration capability in the automobile and computer industries, that a firm’s knowledge-integration capability in product development is positively correlated with its positive performance.

2 Basically, the RBV perspectives are not situated within the developing economy catch-up context, however, they do provide more textured and in-depth ways of considering capability reconfiguration.

5

Dynamic capabilities, termed and defined by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (1997), refer to the abilities to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external capabilities to sustain competitive advantage in a rapidly changing environment. Dynamic capabilities consist of specific strategic and organisational processes. These processes include product development, alliances and strategic decision making which creates value for firms within dynamic markets by manipulating resources into new value creating strategies (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). The dynamic capabilities theory emphasises that competitive advantage rests upon distinctive processes, shaped by a firm’s unique assets and the paths followed. Coordination and integration of a high level of appropriability, search and learning for new production opportunities, and the transformation of internal and external resources are key factors in determining the distinctive processes.

Dynamic Capability emphasises the key role of strategic leadership in appropriately adapting, integrating and reconfiguring organisational skills and resources to match the changing environment (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Lavie 2006; O'Reilly and Tushman 2007; Teece 2007). The original definition of dynamic capabilities refers to “a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997).

Subsequent work refines and expands the original definition, and Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) provide an example of dynamic capabilities as being processes, such as product development routines, alliance and acquisition capabilities, resource allocation routines and knowledge transfer and replication routines, and further extend the original definition to the creation of market change, as well as the response to exogenous change. Zollo and Winter (2002) provide a definition which focuses upon the dynamic capabilities which modify an organisation’s

operating routines. Information processing capabilities may enable a firm to identify the nature of the changing market environment and sense the opportunities it has for a potential continuing source of competitive advantage (Teece, Pierce et al. 2002;

Denrell, Fang et al. 2003).

The foregoing research includes a range of definitions of dynamic capabilities. Adner and Helfat (2003) use the term “dynamic managerial capabilities”

to refer to the capacity of managers to create, extend or modify the resource base of an organisation.

Rosenbloom (2000) highlights the importance of management leadership as a dynamic capability. Zott (2003) focuses on dynamic capabilities as being routine organisational processes which guide the evolution of a firm’s resources and operational routines. Galunic and Eisenhardt (2001) analyse dynamic capabilities as being how managers manipulate resources into new configurations as markets change. Collis (1994) includes strategic insights derived from managerial or entrepreneurial capabilities.

Building upon existing literature, there is a consensus definition, namely A dynamic capability is the capacity of an organisation to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007). The words in this definition have specific meanings. The “resource base” of an organisation includes tangible, intangible, and human assets, as well as capabilities which the organisation owns or controls, or their capability to comprise part of the resource base. According to this definition, capabilities are considered as being “resources”. The word “capacity” refers to the ability to perform a task in at least a minimally acceptable manner. The word

“purposefully” also has a specific meaning, indicating that , even if not fully explicit, dynamic capabilities reflect some degree of intent, even if not fully explicit. Dynamic capabilities can, therefore, be

6

distinguished from organisational routines, which consist of rote organisational activities which lack intent (Dosi, Nelson et al. 2000). Intent excludes accident or luck but incorporates emergent streams of activity (Mintzberg and Waters 1985). The word

“create” includes all forms of resource creation in an organisation, including obtaining new resources through acquisitions and alliances, as well as by means of innovation and entrepreneurial activities.

This definition of dynamic capabilities also incorporates search and selection aspects. The creation of resources through acquisitions, for instance, fundamentally involves searching for and selecting acquisition candidates. As part of resource modification, a firm may choose to destroy part of its existing resource base by selling, closing, or discarding it. Thus, dynamic capabilities also apply to exit, not only to expansion (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007).

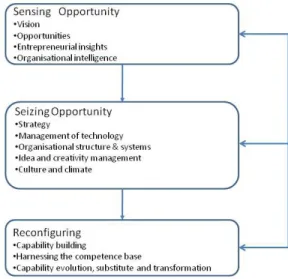

For analytical purposes, dynamic capabilities can be disaggregated into the capacity:

(1) to sense and shape opportunities and threats

(2) to seize opportunities

(3) to maintain competitiveness by enhancing, combining, protecting, and, where necessary, reconfiguring the firm’s intangible and tangible assets (Teece 2007).

Capability reconfiguration is a frequently mentioned phenomenon in dynamic capabilities studies (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000), but which requires further elaboration and elucidation (Lavie 2006). Reconfiguration involves the retention, deletion, and addition of resources and capabilities (Capron, Dussauge et al. 1998). Capability reconfiguration is a two-stage process whereby:

(1) the firm redefines its perceived value,

maximising (delivery) capability in view of the change and its implications

(2) the firm reconfigures its actual capability in order to achieve a fit with the perceived value (Lavie 2006).

Technological Regime

A technological regime can be regarded as industry-specific factors influencing technology sourcing. It can be broadly defined by the particular combination of four fundamental dimensions:

technological opportunities, appropriability of innovations, cumulativeness of technological advances, and properties of the knowledge base (Malerba and Orsenigo 1997). Nelson and Winter (1982) were probably the first to use the notion of technological regimes. A technological regime not only defines boundaries but also indicates trajectories (Dosi 1982). Three basic dimensions of technological opportunities related to technology sourcing can be identified: level, pervasiveness, and source. Higher level of technological opportunities determines greater profits from innovation.

Open Innovation

In many industries and sectors, innovation is an increasingly distributed process, involving networks of geographically dispersed players with a variety of possible and dynamic value chain configurations.

‘Open innovation’ is one term that has emerged to describe:“[..] the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation, and expand the markets for external use of innovation, respectively” (Chesbrough, Vanhaverbeke et al. 2006). With the emerging role of the ICT industry in Asia, firms begin to make use of open innovation to develop their capabilities in response to market and technological change. With open innovation, firm boundaries become permeable and allow for the matching and integration of resources between the company and external

7

collaborators. In the closed innovation model, companies innovate relying on internal resources only. In a traditional closed innovation process, all the invention, research and development is kept secure and confidential within the company until the end product is launched. With open innovation, the company can make use of external competencies and even spin out by-products of its own innovation to outside organisations. In the research of innovation capability reconfiguration, open innovation practices focused upon are those relating to intellectual property management, the development of appropriate skills, and the role of geographic location. Each of these is considered in the context of partnership with start-ups, universities and multinational corporations.

Research Framework: the integrated model

By integrating dynamic capability approach, technological regimes, and innovation capability reconfiguration, this research proposes an integrated model that would be used to explore how firms in NIEs reconfigure their innovation capability and sustain their growths. The integrated model is derived from sensing-seizing-reconfiguring framework proposed by Teece in 2007. In my prior research on innovation capability reconfiguration, an observation is made from data of three top PC companies in Taiwan. The sensing and seizing capacities are more presented in the early development of the firm and the capability is therefore accumulated and learned through the series events of sensing and seizing. The interaction between sensing and seizing generates the capability building as part of the reconfiguring mechanism.

This research would build up further understanding of innovation in NIEs on the foundation of the revised model with two more factors, technological regimes and open innovation. Open innovation is emerging as a way firms adjust their competence

base and resource portfolio in pursuing their goals.

Different industry has respective technological regimes therefore firms within each industry present different growth pattern and development. The integrated model to guide this exploratory research is presented as Figure 2.

Case study

The research analyzed the development of an own brand smart phone manufacture which began its business by OEM and transformed to an OBM successfully. The case analysis indicates that operation platform is a critical factor in developing its technological capability in smart phone industry.

The opportunities resides on the software applications and the channels it can control for sales.

Given the limited resources, the case company utilized an alliance strategy, leveraging external vendors to support its software development while internal software development capability takes time to grow. This is more important for application development as the company offers smart phone on different operation system platform. To maintain its speed for new products and new applications, vendor management and time to market are two key successful factors that centers on case company’s strategic decision.

Research Contribution

This research makes several important contributions to the literature of innovation management, particularly in developing economies. The industrial evolution toward OBM is a relatively recent phenomenon, and academic literature on the subject is in the very early stage of development. Scholars have only just begun to highlight the need for scholarly research of the phenomenon of this evolution from CM to OBM (Kim 1980; Kim and Utterback 1983; Kim 1997; Kim 1998; Kim and Mauborgne 1999; Hobday 2003; Lin 2004; Hobday

8

2005). This study will present several longitudinal studies that attempts to develop a comprehensive understanding of the innovation capability reconfiguration of firms in developing economies.

The research specifically provides perspectives of (a) how firms in developing economies evolve over time, (b) how they reconfigure their innovative capability, (c) how technological regimes influence the reconfiguration, and (d) how open innovation practices facilitate the reconfiguration. The increasing awareness of Asian firms in the global marketplace warrants a systematic understanding of their business evolution (Foster, Cheng et al. 2006;

Dedrick and Kraemer 2008; Shin, Dedrick et al.

2008). Thus, this research makes a new and important contribution by providing a descriptive and explanatory theory which illuminates how firms reconfigure their innovative capability.

Most scholarly work on innovation focuses upon observations and issues in developed economies, and studies which deal with the generation of innovation in the context of developing economies are scarce. Moreover, longitudinal studies which have investigated aspects relating to the generation of innovation in developing economies are mainly based upon Korean firms (Kim 1997; Kim 1998;

Kim and Lee 2002) and some South eastern Asian countries (Hobday 1995; Hobday 2003). The development of firms and industries in Korea and Taiwan is different, since most Taiwanese firms are small and medium sized in the beginning, whilst Korean firms are in the form of enterprise groups, also known as Chaebols. Therefore, the findings based upon data from Taiwanese firms contribute to theory by offering different perspectives of developing economies.

Dynamic capabilities have attracted a great deal of interest among management scholars. It has been

more than a decade since the most cited work (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997) on dynamic capabilities was published. However, the study of dynamic capabilities to date has raised many unanswered theoretical and empirical questions (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007). This research adopts the latest framework of dynamic capabilities to analyse organisational evolution and change over time (Teece 2007). The empirical data gathered and guided by the framework developed from dynamic capability will further the understanding of this theory and its application.

Reference (upon request)

Figure 1. Dynamic capability framework Source: Teece, 2007

Figure 2 The integrated model

國科會補助 國科會補助 國科會補助

國科會補助專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心 得報告

得報告得報告 得報告

一、參加會議經過

本次會議位在矽谷舉辦,是創新最重要的地點之一,因此聚集不 少產官學界人士,進行意見交流與探討,在會中也與日本、英國 學者進行交流及問題的探討,收穫豐碩。

計畫編 號

NSC 99-2410-H-011 -030 -

計畫名 稱

新興工業國家之企業創新能力重塑:技術治理與開放 創新的影響

出國人

員姓名 郭庭魁

服務機 構及職 稱

台灣科技大學科技管理 研究所

會議時 間

2011/06/27-30 會議地 點

Sam Jose, USA

會議名 稱

IEEE International Technology Management Conference 2011

發表論 文題目

How contract manufacturers compete with their clients:

A case study on innovation capability reconfiguration

二、與會心得

本次會議有不少實務界人事參與,因此對於研究問題的產業價值與實用性,

有多一層的關注,依循 IEEE 會議的傳統,需要在實務應用上多所著墨,而 不能單論學術貢獻。

三、建議

1. 此次會議,如由科技大學觀點,應值得鼓勵,IEEE 為美國享有盛名的專 業學術學會,從科技領域跨入管理領域,亦是科管學者可以發揮所長的領域 之一。

2.實務界的參與能讓議題討論更為具體。

四、攜回資料名稱及內容

研討會論文光碟集,所有論文皆已納入 IE 資料庫中。

六、其他

論文網址:

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=5996022978-1-61284-952-2/11/$26.00 ©2011 IEEE 522 IEEE Int'l Technology Management Conference How Contract Manufacturers Compete with their Clients:

A Case Study on Innovation Capability Reconfiguration Ting-Kuei Kuo

Graduate Institute of Technology Management, National Taiwan University of Science & Technology No. 43, Keelong Road Section 4, Taipei, Taiwan

Email: tkk@mail.ntust.edu.tw Abstract

This paper attempts to explore the primary capability configuration in business transition. The business transition from Contract Manufacturing to Own Brand Manufacturing inherently changes the importance of each source of innovation, including lead users, customers, suppliers, external scientific expertise, internal R&D, universities and competitors. Some of the innovation capabilities may no longer be available or useful while new capabilities may need to be built up to generate the right ideas and respond to market demands. How to manage the change in the reconfiguration of innovation capability appears to be vital for firms’ survival and sustainable advantage whereas the emergence of the knowledge economy, intense global competition and considerable technological advance has seen become increasingly central to competitiveness. How to manage the change appears to be vital for firms’ survival because innovation is widely acknowledged to be a major source of firm growth and key to survive its competition.

Acer was chosen for this case study due to its impact and significance in the worldwide PC industry. The data was collected through in-depth interviews and secondary data analysis. The findings show that sources of innovation change as business models evolve. To cope with the change, innovation capability needs to be substituted, transformed, or reconfigured to exploit new sources of innovation. External collaboration could facilitate the transition and shorten the product time-to-market. Internal collaboration may safeguard the innovation rate and product competitiveness.

The findings of this study suggest that firms pursuing business transition should consider a proactive focus toward future source of innovation. The insight from this paper also provides fresh perspective on the innovation paradigm in the East Asian, known as the developing economies while most the existing innovation theory and perspectives are built on the data and cases from the advanced countries. The implication related to industry as this research seeks to identify key factors in business transition and how capabilities are reconfigured. Further research is also discussed in the conclusion..

Introduction

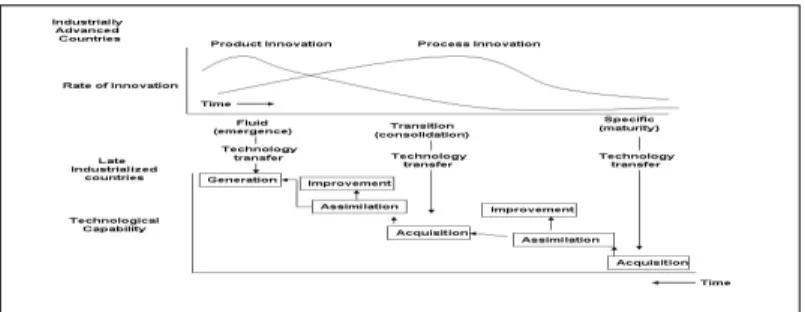

There has been an increasing amount of research on the progress and performance of firms in East and South East Asia [1-3]. The unique character of innovation trajectories in East Asia has been highlighted and compared with Utterback and Abernathy’s model of industry evolution (Utterback and Abernathy, 1975), as presented in Figure 1. The sequence of innovation events is reversed, with developing countries regressing from what Utterback and Abernathy defined as mature to the early stages of the innovation process.

Furthermore, the CM system plays an important role, aiding technology transfer and helping firms to attain economies of scale and accumulate learning from process innovation to product innovation [3]. The Taiwanese personal computer industry illustrates this growth pattern particularly clearly [4].

Figure 1. A simple life cycle model of innovation in developing countriesSource: Kim (1997, p.89)

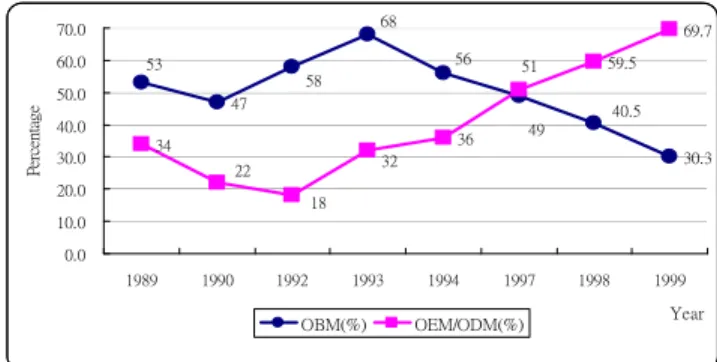

After the late 1980s, the CM business evolved into ODM as the relationship between CM firms and buyers deepened through continued cooperation. Given the depth of know-how of techniques derived from years of experience, CM firms are capable of doing minor product design and product prototype as value added services to the buyers. Under the CM/ODM arrangement, firms follow the specifications from buyers.

During the interaction, new product concepts and technologies, new to the CM firms, are transferred into CM/ODM organizations from the buyers [5]. The technology and knowledge capacity is accumulated through the input from buyers and also during the scale-up of manufacturing.

Given the technology and know-how learned, CM/ODM firms are able to follow the overall layout from buyers to develop products. In other words, CM/ODM firms started the learning by process innovation to catch up with the advanced technologies. This signified the new stage of transition: from CM to ODM. Firms could capture more value by providing minor design services to their CM buyers. CM firms extended upward in the value chain as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The transition in the Taiwanese PC industry In the mid 1990s, some firms such as Acer attempted to sell their own branded products to local and global market.

The declining margins of CM/ODM business and a lack of

scale economies were the main drivers behind the move [6].

With the development of OBM business, rivalry began to appear as the competition between own brand products and CM/ODM customers became tense. CM/ODM customers, such as IBM and HP, threatened to withdraw orders to stop the emerging competition. However, when CM/ODM buyers withdrew, they not only cancelled the orders but also cut off the sources of new products, technologies and know-how.

Firms such as Quanta and Compal, who had intended to start operating on an OBM basis, gave in to the threat from buyers and remained focused on CM/ODM business. Firms such as Acer and Asus became devoted to developing their own brands and regarded it as the route to survival and sustainable growth.

The objective of this research is to explore how Taiwanese PC firm coped with the business transition from CM to OBM.

In particular, when customers become competitors, how they manage the shift in the sources of innovation and how they reconfigure the capabilities.

Prior Literature

The literature review covers several relevant areas. Firstly, it discusses what the sources of innovation are and how they might influence a firm. Next, the innovation capability is discussed to elaborate what capabilities are required when moving toward OBM. Considering a firm as a combination of resources and capabilities, the resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities are discussed accordingly. Dynamic capabilities framework provides a starting point to analyze a firm in business transition.

Sources of innovation

Innovation is a widely acknowledged to be a major source of economic growth and competitive advantage [7, 8]. New product and process ideas originate from a variety of sources [9]. These innovation sources can be categorized as originating as a result of efforts substantially from within the firm, and those that are accessed external to the firm and transferred in to it [10]. The value of each source depends on the firm’s existing stock of knowledge and their ability to access, absorb and exploit new ideas [11, 12]. Previous research has identified several origins as the sources of innovation, including users, customers, consumers, suppliers, external scientific expertise, internal R&D, universities, and competitors [10, 13-19]. The insights from lead users are particularly emphasized as a source of novel product concepts in marketing research [20].

The transition of business from CM and to OBM inherently changes the importance of each source of innovation. Some of the sources might be no longer available or useful. New sources might need to be discovered so as to generate the right ideas in response to market demands. How to manage the change in the sources of innovation appears to be of vital importance for the firm’s survival and sustainable advantage whereas innovation has become increasingly central to competitiveness [15].

Innovation capability

Innovation is the mechanism by which organizations produce new products, processes and systems required for adapting to changing markets, technologies and modes of

competition [13, 21]. The sources of innovation are where the ideas originate from, but a firm may not be able to exploit the sources with the existing configuration of resources and capability [22]. Lawson & Samson [15] regard innovation capability as an integration capability to mould and manage multiple capabilities, and to continuously transform knowledge and ideas into new products, processes, and systems for the benefit of the firm and its stakeholders [12, 23, 24]. It is a key business process for success, survival and organisational renewal [25, 26].

Dynamic Capabilities

Recent research in the strategy field focuses on how alliances, such as acquisitions, provide a means whereby firms attempt to overcome the constraints and barriers which existing routines create [27, 28]. Capability reconfiguration is a frequently mentioned phenomenon in dynamic capabilities studies [29, 30], but which requires further elaboration and elucidation [31]. Reconfiguration involves the retention, deletion, and addition of resources and capabilities [27].

Dynamic capabilities theory emphasizes that competitive advantage rests on distinctive processes, shaped by the firm’s unique asset and paths followed. Dynamic capabilities also emphasize the importance of management capabilities and inimitable combinations of resources that cut across all functions, including R&D, product and process development, manufacturing, human resources and organizational learning [15, 32].

Due to the different innovation trajectories from those in the developed countries, existing resource-based perspectives may not be adequate for dealing with the innovation positions, paths, and processes [33]. More frequently, it makes sense to use dynamic capabilities to build new resource configurations and move into fresh competitive positions without maintaining path dependence. The path breaking change (i.e. CM to OBM transition) may occur in cases where expansion incentives and competitive pressures outweigh path dependence [29, 34].

Building upon existing literature, there is a consensus definition, namely A dynamic capability is the capacity of an organisation to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base [35]. Dynamic capabilities can, therefore, be distinguished from organisational routines, which consist of rote organisational activities which lack intent [36]. Intent excludes accident or luck but incorporates emergent streams of activity [37]. The word “create” includes all forms of resource creation in an organisation, including obtaining new resources through acquisitions and alliances, as well as by means of innovation and entrepreneurial activities.

This definition of dynamic capabilities also incorporates search and selection aspects. The creation of resources through acquisitions, for instance, fundamentally involves searching for and selecting acquisition candidates. As part of resource modification, a firm may choose to destroy part of its existing resource base by selling, closing, or discarding it. Thus, dynamic capabilities also apply to exit, not only to expansion [35].

For analytical purposes, dynamic capabilities can be disaggregated into the capacity:

(1) to sense and shape opportunities and threats (2) to seize opportunities

(3) to maintain competitiveness by enhancing, combining, protecting, and, where necessary, reconfiguring the firm’s intangible and tangible assets [38].

Conceptual Framework

Based on dynamic capability perspective, Lawson and Samson [15] propose that the capability of innovation is a higher order integration capability and powers the newstream activities. Innovative firm’s capability enables the newstream to act like a funnel, seeking, locating and developing potential innovation which can be transferred into the mainstream. It is about synthesizing newstream and mainstream for innovation.

Dynamic Innovation capability can, therefore, be defined as being the ability to continuously transform knowledge and ideas into new products, processes and systems for the benefit of the firm and its stakeholders. New ventures are characterized by such set of capabilities as to realize innovative ideas and commercialize technologies.

A dynamic capability can be seen as being a set of actions taken by senior management which permits a firm to identify opportunities and reconfigure assets to adapt [39]. When it comes to the creation and adjustment of firms’ strategies, senior executives play a particularly critical role, both in terms of what they choose to do and what they choose not to do [35]. This particularly applies to new ventures as entrepreneurs play a crucial role in the beginning. The behavior and actions of its founders and top management team lead to the development of a firm’s dynamic capabilities [40]. As Teece [38] indicates, for entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial management, it is more about sensing and seizing, working out the next big opportunity and deciding how to address it. Entrepreneurship is about sensing and understanding opportunities, getting things started, and finding new and better ways of putting things together.

Dynamic capability is not a separately identifiable construct. It is composed by reinforcing practices and processes within the firm. These processes are key mechanisms for stimulating, measuring and reinforcing innovation. Based upon a dynamic capabilities approach, Lawson and Samson [15] propose a model of seven major elements, namely vision and strategy, harnessing the competence base, organizational intelligence, creativity and idea management, organizational structure and systems, culture and climate, and the management of technology.

This research utilizes the constructs of innovation capability and the dynamic capabilities framework to examine new ventures’ development. The integrated conceptual framework is described in the following paragraph and presented in Figure 3.

Sensing opportunity refers to a firm’s cognition of opportunities. It could be that the opportunity is identified, scanned or searched by means of organizational processes or it could be the vision and insight of top management, senior executives or entrepreneurs. Therefore the concept can be observed as being by vision, opportunity, entrepreneurial insights, and organizational intelligence.

Seizing opportunity refers to how a firm addresses the opportunity sensed. Factors which influence the realization of the opportunity are included in the observation. Summarized from the previous discussion, the responding actions a firm can take include a corresponding strategy, management of technology, organizational structures and systems, ideas and creativity management, and culture and climate.

Reconfiguring refers to the capacity a firm possesses to maintain its competitive advantage. If its strategy is correct, it may need to align its resources and capabilities more tightly with the strategy or improve its efficiency. If the market or technology changes, a firm needs to reconfigure its assets and capabilities to sense and seize new opportunities. This may involve enhancing existing capabilities and spinning out, or off, a subset of capabilities.

Figure 3 Conceptual framework Research Methodology

To achieve the research goals, understanding the transition from CM to OBM and finding the major factors for innovation requires information and access to facilities that are often sensitive and confidential. The lack of existing knowledge of the subject mattered and the requirement of the degree of access necessary to obtain the data means case studies are the most appropriate method [41].

The construct validity will be built from multiple sources of evidence from literature, interviews and secondary data analysis. Data analysis on pattern-matching and explain- building will contribute to internal validity, which is also achieved through comparison with other companies in transition from CM to OBM. The research design has included replication logic in multiple case studies that makes external validity. The database of cases, the research protocol and the semi-structured questionnaire will ensure the reliability of the study.

Data Collection

Following archival data gathering from secondary sources, the majority of the data for the case studies will be gathered from field work in Taiwan. Case studies usually combine data collection methods such as archives, interviews questionnaires and observations. There will be in-depth

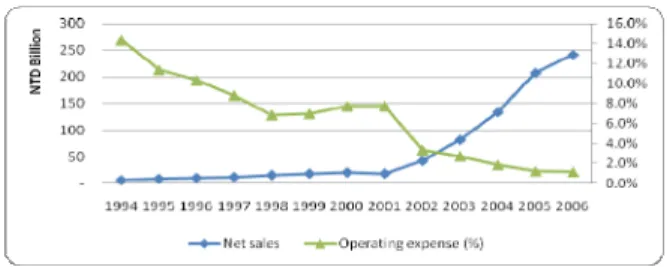

interviews with firm executives, analysts, competitors, partners and suppliers to map the whole change during the business transition. The selected case, Acer Inc, is the leading company among Taiwanese PC firms who experienced several transitions in its history. Acer is currently ranked number 3 in sales volume according to IDC report of the 4th quarter in 2007 after it acquired Gateway and Packard Bell.

Case Study

Founded in 1976 by Stan Shih, Acer was the first Taiwanese computer company to try to build its own brand name in foreign markets. It is now Taiwan’s largest brand name computer exporter and one of the top three personal computer brand names in worldwide PC markets [42].

The period 1976-1980 marks Acer’s start-up phase. The initial product lines were located in Taiwan, where cheap labour and rent were available. It moved into the Hsinchu Science Park near Taipei in 1981. The company started making clones of the IBM personal computer shortly after it was introduced in 19811. IBM-based computers, peripherals, and accessories, manufactured for other companies, became Multitech’s2 largest product lines.

The period 1981-1988 marks the firm’s transition from a domestic company to an international one. In 1983, it began manufacturing IBM compatible personal computers, primarily selling under its own brand, Multitech. In 1984, the sales reached US$51 million, representing a sevenfold increase on revenues three years earlier.. In 1986, Multitech felt ready to stake a claim in Europe, establishing a marketing office in Düsseldorf of Germany and a warehouse in Amsterdam of the Netherlands3. In 1987, the company changed its name to Acer because of infringing a U.S. company’s trademark. The growing visibility led to the issue inevitable. The name, Acer, was chosen not only because its Latin root meant sharp or clever, but because “Ace” implied first or highest value in cards. But mostly it is because it would be first in alphabetical listings.

The Dragon Dream

As the company approached its tenth anniversary, it announced a plan for the next ten years that was described as

“Dragon Dream”. With the revenues of US$150 million in 1986, the goal was to achieve sales of US$5 billion by 1996.

In several Asia countries, the company was already a major player. For example, in Singapore, it had a 25% market share by 1986. The Dragon Dream was built on the Asian base and the new offices in Europe and the United States, Stan Shih created the slogan, “The Rampaging Dragon Goes International.” To implement the plan, the need to identify potential overseas acquisitions, to set up offshore companies, and to seek foreign partners and distributors was emphasised.

The vision for the year 2000

At Acer’s 1992 international distributors meeting in Mexico, the company articulated a commitment to linking the

1 Interview with co-founder, Fred Lin, 16/4/2007

2 Acer originally was named Multitech since established.

3 Interview with Harry Liang, 20/05/2007. Harry Liang was the first CEO of European operations.

company more close with its national markets, describing the vision as Global Brand, Local Touch [43]. It envisioned Acer evolve from a Taiwanese company with offshore sales to a truly global organisation with deeply-planted local roots. To fulfil the vision for the year 2000, Stan Shih and his management team came up the strategy consisting of several elements: 1) joint ventures with partners overseas, 2) fast food style manufacturing and assembly operations, and 3) a client server organisation structure [44].

One key factor in the strategy “Global Brand, Local Touch” was to form joint ventures with partners in foreign markets where the partners take majority interests. Doing so could allow Acer expand into overseas markets without requiring too much capital up front. The financial success and risks were shared between Acer and its partners.

The Fast Food business concept

Taiwanese PC manufacturers traditionally shipped PCs by sea to their intended overseas markets. Several problems coexisted with this arrangement. It usually takes an average of four to five weeks in total to manufacture components and build PCs in Taiwan, then ship by sea to the United States, go through channels and finally reach the customer. Because of the falling prices and currency fluctuation, by the time PCs finally reach store shelves, they may be overpriced. Secondly, dealers and distributors must accurately forecast what configurations (e.g., microprocessor, amount of memory, amount of disk storage, type and number of I/O slots, etc.) customers will buy or else keep a large inventory of PCs of different configurations to satisfy demand. Thirdly, PCs have become commodities, retail channels have increasingly asked for slightly different configuration of their products which may be difficult to accomplish from several thousand miles away.

To overcome these problems, Acer began to create new initiatives. The System PC unit developed the “ChipUP”

concept. This patented technology allowed a motherboard to accept different types of CPU chips—various versions of Intel’s 386 and 486 chips—drastically reducing inventory of both chips and motherboards. Another unit, Home Office Automation, developed the “2-3-1 system” to reduce the new product introduction process to two months for development, three months for selling and one month for phase-out.

Acer is not the first to apply distributed manufacturing concept to the manufacture of PCs. Some PC manufacturers in Taiwan had already discovered that in order to compete, they had to source casings and some other components locally and assemble locally, but they did not approach this systematically. Acer, however, with its pragmatic approach, adapted the concept fit its environment and further refined it.

In order to fully implement this manufacturing strategy, Acer registered its PCs for easy modular assembly as well as configuration flexibility. As a result, Acer had four to five designs of motherboards and three chassis. By the patented technology of ChipUp, every motherboard can accommodate different Intel microprocessor and any motherboard can fit into any chassis. This flexibility also allows each assembly site to put together PCs with the exact microprocessor model, memory, hard disk storage that are appropriate for its market.