兒童日常生活中數位媒體使用:以台灣學童部落格使用為例 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 論文題目. 兒童日常生活中數位媒體使用: 以台灣學童部落格使用為例 Children’s Digital Media Usage in Everyday Life: Case Study on Two Elementary School Students’ Weblog Behavior 治in Taiwan . 立. 政. 大. ‧ 國. 學. Student: Hsiao-Chen Weng (翁孝蓁). al. A Thesis. er. io. sit. y. Nat. . ‧. Advisor: Dr. Sophia Wu (吳翠珍博士). n. iv n C h e n g c Master’s Submitted to International h i U Program in International Communication Studies National Chengchi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the Degree of Master in International Communication Studies. 中華民國 99 年七月 July, 2010.

(3) Children’s Digital Media Usage in Everyday Life: Case Study on Two Elementary School Students’ Weblog Behavior in Taiwan. A Master 治 Thesis. 立. 政. 大. ‧ 國. 學. National Chengchi University. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. iv n C U h e n gofcthe In partial fulfillment h i Requirements For the Degree of Master in International Communication Studies. by Hsiao-Chen Weng. July, 2010.

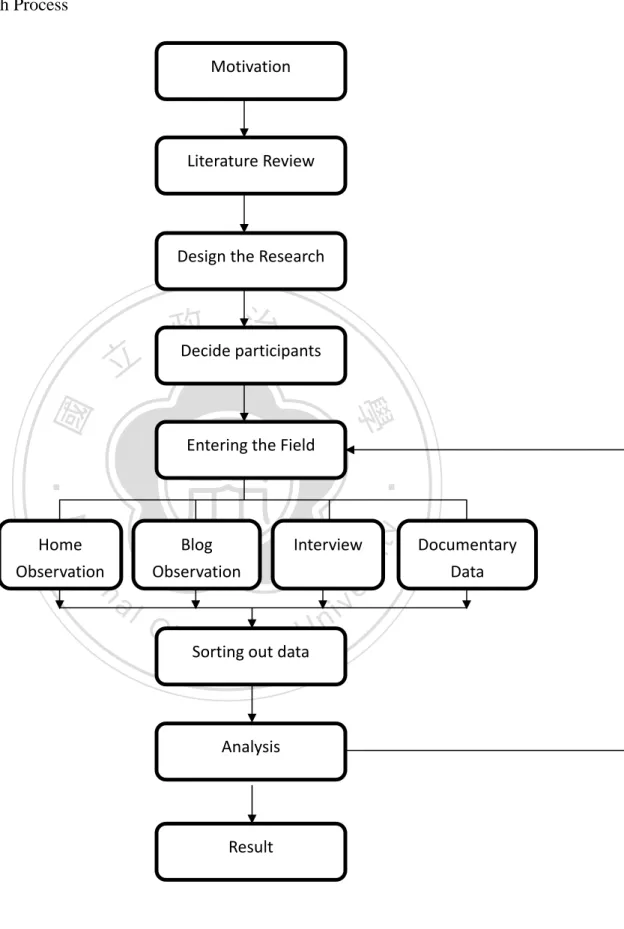

(4) CONTENTS CONTENTS.................................................................................................................. I LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................. III ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .......................................................................................... V ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. VII . 政 治 大 .......................................................................................................... 1 立. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1 . ‧ 國. ‧. . 學. 1.1 MOTIVATION 1.2 BLOGGING IN EVERYDAY LIFE .............................................................................. 3 1.3 CHILDREN BLOGGING ON INTERNET ..................................................................... 4 1.4 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ............................................................................................ 5 1.5 RESEARCH QUESTION AND STATEMENT OF PURPOSE............................................. 5. y. Nat. sit. CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 7 . n. al. er. io. 2.1 CHILDREN AND DIGITAL MEDIA ............................................................................ 8 2.2 CHILDREN AND BLOGS ........................................................................................ 10 2.3 CHILDREN AS BLOGGERS .................................................................................... 11 2.4 PERFORMANCE ON DIGITAL STAGE ...................................................................... 14 2.5 CHILDREN’S DIGITAL BEDROOM CULTURE .......................................................... 17 2.6 CHILDREN AND IDENTITY .................................................................................... 22. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY............................................................................ 28 3.1 RESEARCH METHODS .......................................................................................... 28 3.2 RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH ................................... 30 3.3 RESEARCH PROCEDURES ..................................................................................... 31 3.4 RESEARCH PROCESS ............................................................................................ 39 CHAPTER 4: ANALYSIS ......................................................................................... 40 4.1 MEDIA USAGE IN EVERYDAY LIFE ON TWO CASES ................................................ 40 I .

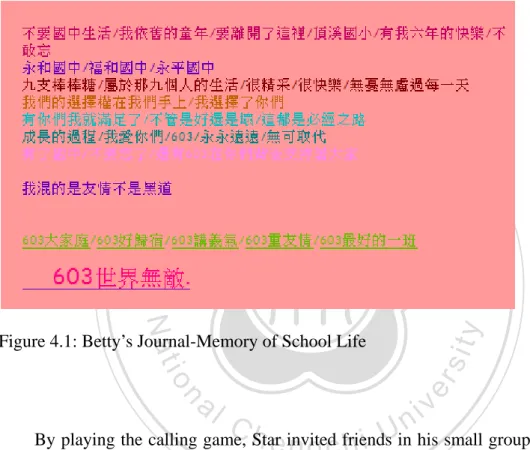

(5) 4.2 FROM THE SCHOOL TO HOME, FROM THE BEDROOM TO THE DIGITAL ROOM ....... 47 4.3 ACTIVE SPREADER FROM REVEALING TO SHARING ............................................. 57 4.4 UNITY AND EXCLUSION AMONG PEERS ............................................................... 63 4.5 FROM PEER SOCIAL NETWORK TO VERTICAL SOCIAL NETWORK ........................ 69 4.6 THE REALITY IN BLOGS ...................................................................................... 74 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION.................................................................................. 81 5.1 RESEARCH FINDINGS........................................................................................... 81 5.2 LIMITATIONS ....................................................................................................... 85 5.3 RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................... 86 5.4 CONCLUSIONS ..................................................................................................... 87 . 政 治 大. REFERENCES........................................................................................................... 89. 立. . ‧. ‧ 國. 學. APPENDICES .......................................................................................................... 100 . n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. II . i Un. v.

(6) LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1.1: WHAT DO CHILDREN THINK THE MOST IMPORTANT MEDIA IS? ........................................................................................................................................ 1 FIGURE 1.2: WHAT DO CHILDREN OFTEN DO ON INTERNET? ........................ 2 FIGURE 3.1: BETTY’S MEDIA USAGE DIARY ..................................................... 34 FIGURE 3.2: BACKGROUND OF PARTICIPANT- BETTY .................................... 37 FIGURE 3.3: BACKGROUND OF PARTICIPANT- STAR ....................................... 38 FIGURE 3.4: RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................ 39 FIGURE 4.1: BETTY’S JOURNAL-MEMORY OF SCHOOL LIFE ........................ 50. 政 治 大. FIGURE 4.2: STAR’S JOURNAL- QUESTIONNAIRE ............................................ 52. 立. FIGURE 4.3: BETTY’S ALBUM PHOTO — FORBIDDEN TOILET ..................... 52. ‧ 國. 學. FIGURE 4.4: BETTY’S ALBUM TABLE-BOARD WITH HUANG MEI-ZHEN ... 55. ‧. FIGURE 4.5: ALBUM OF STAR ATTENDING RAINIE YANG’S AUTOGRAPH SESSION ..................................................................................................................... 52 FIGURE 4.6: PICTURE OF STAR WITH RAINIE YANG’S SIGNING POSTER... 56 . y. Nat. io. sit. FIGURE 4.7: BETTY’S ALBUM- AUTODYNING FACING MIRRORS ................ 57 . n. al. er. FIGURE 4.8: AUTODYNES IN STAR’S ALBUM .................................................... 58 . i Un. v. FIGURE 4.9: AUTODYNES IN BETTY’S ALBUM ................................................. 59 . Ch. engchi. FIGURE 4.10: A PHOTO RECOMMENDED BY BETTY’S FRIEND IN BETTY’S ALBUM ....................................................................................................................... 60 FIGURE 4.11: BETTY’S REMAKING PHOTO 1 ..................................................... 61 FIGURE 4.12: BETTY’S REMAKING PHOTO 2 ..................................................... 61 FIGURE 4.13: MV MADE BY BETTY...................................................................... 62 FIGURE 4.14: BETTY’S EDITED PHOTO 1 ............................................................ 63 FIGURE 4.15: BETTY’S EDITED PHOTO ............................................................... 63 FIGURE 4.16: NINE LOLLIPOPS 1 .......................................................................... 65 FIGURE 4.17: NINE LOLLIPOPS 2 .......................................................................... 65 FIGURE 4.18: ARTICLE ON BETTY’S BLOG ........................................................ 68 III .

(7) FIGURE 4.19: STAR’S JOURNAL - DO NOT WANT TO WANDER IN THE FAIRY WORLD ....................................................................................................................... 76 FIGURE 4.20: STAR’S JOURNAL- JUST BECAUSE I AM YOUNG ..................... 77 FIGURE 4.21: STAR’S JOURNAL- PREPARATION ............................................... 77 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. IV . i Un. v.

(8) 謝辭. 謹以這本論文. 感謝我的父親翁再添先生、母親呂秀滿女士 謝謝你們包容我揮灑青春、追尋夢想,沒有你們堅強的後盾、無微的照顧、無數 次的妥協,我無法曲曲折折堅持到這裡。未來,也請多多指教。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 感謝我的姨丈許武男先生、姨媽呂秀蘭女士. ‧. 謝謝你們從我上大學一路到就讀研究所提供我舒適的住處和溫暖的關懷,這份恩 情,銘記我心,無限感激。. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. V . i Un. v.

(9) 記得小時候讀過陳之藩先生的《謝天》 ,他寫道: 「因為需要感謝的人太多了, 就感謝天罷。無論什麼事,不是需要先人的遺愛與遺產,即是需要眾人的支持與 合作,還要等候機會的到來。越是真正做過一點事,越是感覺自己的貢獻之渺小。」 完成了這本碩士論文,我的心裡浮現出上面這串文字。 感謝我的指導教授吳翠珍老師,謝謝老師在這段不算短的時間中,引領著我在媒 體素養的領域裡實踐和探索,並給予我論文上的建議和指導。祝福您健康平安, 未來我們還要並肩作戰。 感謝兩位口委陳雪雲老師和關尚仁老師,謝謝老師們在口試時鞭辟入裡的提醒, 我才能從混沌中恍然大悟。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 感謝研究室的好姊妹慧玲和圓圓以及一起經營媒概課的優質 TA 團隊,謝謝大家 在我論文醞釀期間的暖暖關懷、再加上不時的打氣和鼓勵。. ‧. 感謝北京實習時相識的好朋友林姐、雅筑、之琦、敏銣、凱西、正諭、義權、廷 飛、善賢、俐婷,謝謝你們成就了我研究生生涯中一段難忘的回憶。. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 感謝我相識十餘載的國中好友致民、郁蕙、翊均、彥超、育安、文甫、博鉅、維 綸、若文,謝謝你們在我生命中沮喪無力時帶給我的歡笑和力量。. Ch. i Un. v. 感謝 Ada 和哲伶兩位摯友,謝謝你們在我生命中的一路相挺。. engchi. 感謝世新的劉文英老師、葉蓉慧老師、胡紹嘉老師以及政大國傳的汪琪老師、朱 立老師、郭貞老師和孫式文老師,謝謝你們的教導和支持,我才有勇氣完成碩士 學位。 感謝協助我找尋研究個案的眾多親友以及所有受訪者們,特別謝謝 Star 和 Betty 兩家人,沒有你們包容我無數次的登門打擾,又放心、掏心的分享,我無法獨自 完成這本論文。 太多人要感謝,就謝天吧! 謝謝你們在我這幾年的研究所生涯中,讓我得到了比一紙碩士文憑更多的寶藏。 我人生的奇幻旅程正要展開。 孝蓁 寫於 2010 盛夏 政大 VI .

(10) Abstract . Children use Internet for many reasons, such as playing on-line games, searching for information, downloading music and videos or doing homework. However, there is one interesting tendency that Internet has changed the boundary between the sender and the receiver. Children in this Internet age, they change their roles to become content providers. While they are blogging or uploading photos, they are processing “I media”.. 政 治 大 playing games while they are in a parenting area. Today, ‘bedroom’ and ‘digital 立 In the past, children invite their friends to their bedroom. They talk the secrets or. bedroom’ can be combined. Staying at home, and not going out, but by surfing the. ‧ 國. 學. (world) of the web, both boys and girls of different ages are engaging in a kind of. ‧. domestic or bedroom culture that take place in virtual space.. Nat. sit. y. In this study, children’s personal weblog may be seen as ‘heterotopias’, Michel. n. al. er. io. Foucault (1986) proposed. This research concerned about children's use of blogs in. i Un. v. their everyday life, attempted to learn children's digital bedroom culture through the. Ch. engchi. analyses of all kinds of documents presented in children’s blogs, and to know how children gain identity through blogs.. Keywords: Weblog, Children, Heterotopias, Digital Media . VII .

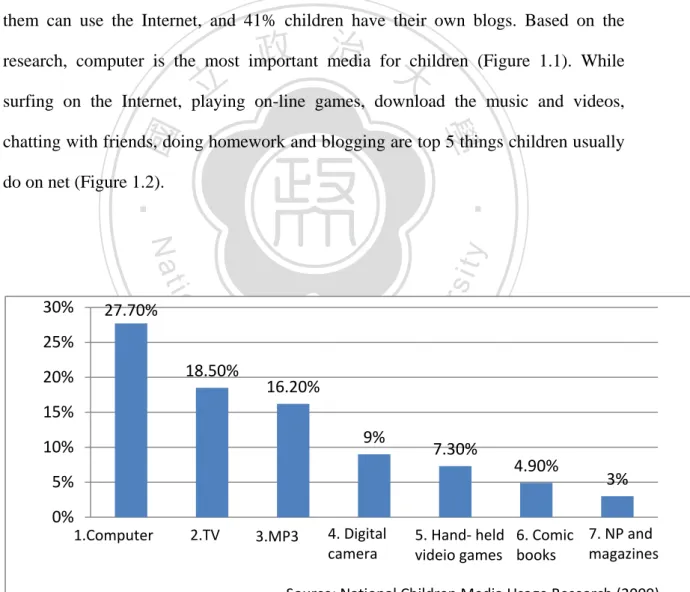

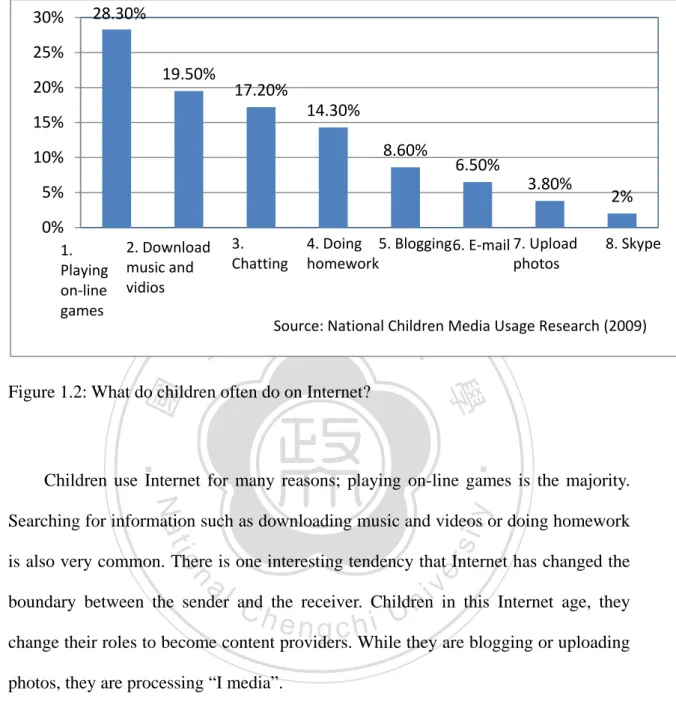

(11) Chapter 1: Introduction. 1.1 Motivation New technology makes our daily life more convenient, it also changes human’s behavior invisibly. According to National Children Media Usage Research (2009), 95.3% children in Taiwan ages 9 through 12 have computers in their family, 84.4% of them can use the Internet, and 41% children have their own blogs. Based on the. 政 治 大. research, computer is the most important media for children (Figure 1.1). While. 立. surfing on the Internet, playing on-line games, download the music and videos,. ‧ 國. 學. chatting with friends, doing homework and blogging are top 5 things children usually. ‧. do on net (Figure 1.2).. sit er. io. 27.70%. y. Nat 30%. al. 20%. 18.50%. n. 25%. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 16.20%. 15% 9%. 10%. 7.30%. 5% 0% 1.Computer. 2.TV. 4. Digital camera. 3.MP3. 4.90%. 3%. 5. Hand‐ held 6. Comic 7. NP and magazines videio games books. Source: National Children Media Usage Research (2009). Figure 1.1: What do children think the most important media is?. 1 .

(12) 30%. 28.30%. 25% 20%. 19.50%. 17.20% 14.30%. 15%. 8.60%. 10%. 6.50% 3.80%. 5% 0% 2. Download 1. Playing music and on‐line vidios games. 3. Chatting. 立. 4. Doing 5. Blogging 6. E‐mail 7. Upload homework photos. 2% 8. Skype. 治 政 Source: National Children Media Usage Research (2009) 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 1.2: What do children often do on Internet?. Children use Internet for many reasons; playing on-line games is the majority.. y. Nat. io. sit. Searching for information such as downloading music and videos or doing homework. n. al. er. is also very common. There is one interesting tendency that Internet has changed the. Ch. i Un. v. boundary between the sender and the receiver. Children in this Internet age, they. engchi. change their roles to become content providers. While they are blogging or uploading photos, they are processing “I media”. Many parents and educators worry about students wasting too much time online, chatting with friends or playing on-line games. They are looking for solutions to save these children from Net. However, these adults ignore that children today are struggling for autonomy and identity in this digital world, for communication, friendship, play, and self expression. Many children use online media to extend their friendships and interests. They use instant messenger to contact with their friends in their off-line lives. This instant 2 .

(13) messenger system provides them a private space to associate with people they already known. Some of them even use on-line community to explore their interests and find the information that school didn’t teach. These on–line groups enable children to connect to peers who share the specific interests.. 1.2 Blogging in Everyday Life. In the late 1990s, a new medium developed on the Internet, which increased the. 政 治 大 this development as a “weblog.” 立 Barger coined this phrase to refer to his web site, participatory nature of online expression even more. Blogger Jorn Barger referred to. ‧ 國. 學. which consisted of a series of links to news articles and other sites he found interesting and informative. Barger formed the term by combining the words “web. ‧. site” and “logging”—hence, the word weblog is now well known (Bausch, Haughey. io. sit. y. Nat. & Hourihan, 2002).. n. al. er. The Internet has turned more of us into creators, especially in the blogging age.. Ch. i Un. v. Anyone who can write, speak, talk in front of a video camera (or web cam), take. engchi. pictures, or create any type of multimedia content has the ability to become a blogger. It’s not necessary for a blogger to have any programming or technical knowledge using one of the established and popular blogging services. It’s not even necessary for a blogger to be an expert on or have credible knowledge about any topic. Blogging is truly a public forum that’s open to anyone and everyone, regardless of their age, sex, income, education level, sexual orientation, geographic area, or occupation. Anyone with access to a computer connected to the Internet can create a “weblog”.. 3 .

(14) 1.3 Children Blogging on Internet. Children engage in peer-based, self-directed learning online. Many of them have their own homepage or weblog on Internet; they share their videos, games and other creations with people and receive the feedback from others online. This digital world lowers the barriers to self-directed learning and empowers children to play with media. Although parents have been primarily motivated to provide Internet access for. 政 治 大. their children for educational reasons, to keep up or get ahead, children are. 立. themselves far more motivated by the entertainment and communication possibilities. ‧ 國. 學. offered by the Internet.. ‧. Among all types of weblogs, personal journals have the most user groups in. sit. y. Nat. Taiwan, most of them consisting of students. A personal journal reflects the inner. io. al. er. world of a blogger through self-disclosure, a process by which an individual shares his or her feelings, thoughts, experiences, or information with others (Derlega, Metts,. n. iv n C Petronio, & Margulis, 1993). The h growing of children e n g c h i U blog usage created numerous controversies. A 13-year-old boy1 in Essex junction, Vermont, killed himself after. repeatedly taunted and bullied online by classmates. Several classmates sent him instant messages calling him gay and mocking him. In 2003, the boy killed himself. In Taiwan, according to the report from Child Welfare League Foundations2 , 24% students have once send or post text or images intended to hurt or embarrass another person. Sometimes, students have written blogs that ridicule the 10 students they dislike the most or the 10 ugliest kids in school. In these instances, children blogging 1. Retrieved June, 25th, 2010 from: http://www.ryanpatrickhalligan.org Retrieved June, 25th, 2010 from: http://distance.shu.edu.tw/97cte_news/e-news/enews_20090302_19.html 4 . 2.

(15) turns into a dangerous weapon, harming other children and even teachers and people they don’t know.. 1.4 Previous Research. The rapid growth of blogs has been marked by increased academic interest. However, published research has focused primarily on adult users while marginalizing the activities of adolescent bloggers (Herring, Kouper, Scheidt, & Wright, 2004a).. 政 治 大. Previous research has considered the genres of weblogs (Herring, Scheidt, Bonus, &. 立. Wright, 2004b), political weblogs (Cherry, 2003), weblogs as journalism (Gallo,. ‧ 國. 學. 2004), and weblogs as community (Blanchard, 2004). Blog Research on Genre Project (Herring et al., 2004b) found diary weblogs particularly those produced by. ‧. adolescent bloggers were among the most numerous type found online.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. In Taiwan, many researchers doing blog research, most of them focus on adult. al. blogging experience. Fewer researches focus on children’s blog usage. Recently some. n. iv n C researchers concerned the blog integrated (Lin, 2009), the influence of h e n gintoc teaching hi U class blog on classroom management (Wu, 2009), and students using peer- evaluation via weblogs (Cheng, 2008).. 1.5 Research Question and Statement of Purpose. In the past, children invite their friends to their bedroom. They talk the secrets or playing games while they are in a parenting area. However, in the digital age, ‘bedroom culture’ and ‘digital bedroom’ can be combined. Staying at home, and not 5 .

(16) going out, but by surfing the (world) of the web, both boys and girls of different ages are engaging in a kind of domestic or bedroom culture that take place in virtual space. In this study, children’s personal blog may be seen as ‘heterotopias3’, Michel Foucault (1986) proposed. In the discussion I consider the following questions: Q1: How do children use blogs in their daily life? What texts do they create on blogs? Q2: How multi-media texts represent children’s digital bedroom culture? Q3: How do children construct identity through blogs?. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. . 3. There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places – places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society – which are something like counters-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality (Foucault, 1986). 6 .

(17) Chapter 2: Literature Review. The Internet is the most recent product of such developments, offering various tools to serve the diverse needs of a worldwide population. Among its various facets is the recent phenomenon of weblogs, also known as blogs- user-generated website where entries are made in journal style and displayed in reverse chronological order. As an information medium, the Internet has rapidly become central in teenager lives, and as a communication medium, it represents a significant addition to the existing. 治 政 means of communication available to them. 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. The developmental stage associated with adolescence by Erickson (1968) is identity versus identity (role) confusion. Teenagers have opportunities to explore new. ‧. roles and adult-level responsibilities and to build a sense of personal identity. In the. Nat. sit. y. process, they experience the struggle between confusion about self and a growing. n. al. er. io. sense of who they are and where they fit in the world. With its inherent anonymity, the. i Un. v. Internet provides a virtual environment in which adolescents can experiment with. Ch. engchi. different facets of identity (Calvert, 2002).. Friendships during adolescence enhance social development, contribute to feelings of self-worth, and may provide an arena in which issues of personal identity and empathy can be addressed (Youniss & Smollar, 1985). Friendships are embedded within larger social networks and peer groups, which play an important role as teenagers seek to understand themselves and others more accurately and to begin differentiating from their families (Brown, Clasen, & Eicher, 1986). Young generation access to communication with friends via interactive messaging media has become nearly ubiquitous. The result, according to several scholars, has been a blurring of 7 .

(18) traditional boundaries between a teenager’s peer/social world, school culture, and family, and a possible diminishment in parental/family influence on the developmental process (Gross, 2004; Kent & Facer, 2004). The growing research literature sets the scene for a shift from asking questions of access and diffusion to asking questions about use, especially about the depth and quality of Internet use. In this chapter, I’ll discuss seven sections to rethink children’s blog usage.. 立. 2.1 Children and Digital Media. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Uses and gratifications theory, which has traditionally been used to explain. ‧. people’s motives for using the media, has only been rarely applied to new media. sit. y. Nat. technologies, such as the Internet. Besides, the few studies that have investigated the. io. er. motives for using the Internet focused on adult users (Ferguson & Perse, 2000;. al. Papacharissi & Rubin, 2000; Perse & Dunn, 1998). These studies have yielded mixed. n. iv n C results. Ferguson and Perse (2000) that entertainment was the most salient h efound ngchi U. motive for visiting the web, followed by passing time, social information, and relaxation, respectively. Papacharissi and Rubin (2000) found that information seeking and entertainment were equally important motives for using the Internet. Convenience (e.g., it is easier to e-mail than tell people something), passing time, and interpersonal utility (e.g., to participate in discussions) were less salient reasons for going online. Finally, a study of Perse and Dunn (1998) revealed that adults’ motives for using their computer were related to their Internet access. The more people used their computer to go online, the more they used it for entertainment and to pass time.. 8 .

(19) Teenagers report using instant messaging, text messaging, and social networking websites (along with e-mail) for most of their written communication with friends and peers (Lenhart & Madden, 2007; Lenhart, Madden & Hitlin, 2005). Digital technologies, or more precisely certain uses of them, continue this process of redefinition in seemingly contradictory directions. Thus on the one hand, they seem to offer a kind of ‘adultification’, since young people can act in the digital realm with an equivalence of grown-up power. On the other hand, they seem to have continued the process of ‘juvenilization’ associated with leisure pastimes, and. 政 治 大. particular with notions of playing games. (Sefton-Green, 1998).. 立. Children growing up today with computers and the Internet may have a different. ‧ 國. 學. definition of ‘old’ and ‘new’ than adults or communication researchers.. ‧. Furthermore, a new media is often perceived as displacing other media or other. sit. y. Nat. activities, especially in the lives of children.. n. al. er. io. Initially each medium – television, video cassette recorder, computers and the. i Un. v. Internet – was merely a technological possibility for communication. Whether they. Ch. engchi. gained a place in society and in the everyday life of people (as well as the kind of place they attained) depended on individual users, on culture and on society. Thus when dealing with ‘old’ and ‘new’ media it is essential to look carefully both at whether, and in which way, a new medium becomes integrated in society and in culture, into the everyday life of people, and also at what happens with the old media – whether they disappear or change their functions. This is to be seen as a gradual process, depending on the specific social and cultural conditions.. 9 .

(20) 2.2 Children and Blogs. A blog is most easily described as a website that is updated frequently with new material posted at the top of the page (Blood, 2002a). Blog entries (‘posts’) are arranged in reverse chronological order and the most recent post appears first’ (Walker, 2005). A blog is an online-based journal with multiple entries. Originally, blogs were designed to be websites (or pages within a website) created to simulate a traditional,. 政 治 大. text-based written diary. The term “blog” is derived from two words—web and log.. 立. Blogs continue to provide a forum for creating a digital journal displayed as. ‧ 國. 學. individual entrees in reverse chronological order (based on the date each entry is created and published). The person who creates or writes the blog is referred to as a. ‧. blogger, and the process of creating and publishing a blog is known as blogging.. y. Nat. io. sit. Today’s blog take on many digital formats and styles, plus utilize one or more types of. n. al. er. digital content, including text, graphics, photographs, sounds effects, music, video,. Ch. and other multimedia content (Jason, 2009).. engchi. i Un. v. Forerunner to today’s blogs began in the early 1990s as websites listing annotated hyperlinks to other websites. When someone with a website found other sites they thought contained interesting, curious, hilarious and/or generally newsworthy content, they would create a link to that material, annotate it briefly, and publish it on their website. Readers could decide on the basis of the description whether it was a click to check the link out (Jason, 2009). In 1999, however, blog publishing tools and blog hosting services became available on a large through Pitas.com and Blogger.com. This made it relatively easy 10 .

(21) for Internet users who were unfamiliar or uncomfortable with using hypertext markup language and the principles of web design for coding and designing their own weblogs. Setting up a blog now simply involved going to a website, signing up for a blog account, following a few fairly straightforward instructions, and in less than 30 minutes one would have some ‘copy’ up on the Web that was automatically formatted and laid out to the tune of your choice by means of whichever off- the-shelf template you had chosen (Stuffer, 2002). A blog is a website that’s designed to be updated with items in a linear,. 政 治 大 meant specifically for public consumption. Often implemented using special software, 立 time-based fashion, similar to a personal journal or diary, expect that the contents are. ‧ 國. 學. weblogs contain articles or entries that are grouped primarily by the date and time they are posted (Stuffer, 2002).. ‧. A blog is a frequently modified web site that allows updating with items that are. y. Nat. io. sit. grouped primarily by the time and/ or date of posting. Entries usually appear in. n. al. er. reverse chronological order. Contents of the weblog may be available publicly or. Ch. i Un. v. through restricted access. Blogs may also utilize special software designed for this implementation.. engchi. 2.3 Children as Bloggers. Nardi, Schiano, Gumbrecht, and Swartz (2004b) interviewed 23 bloggers in the California and New York areas, and found that people blog to document their lives; to express opinions or to comment; as catharsis; to use these writing areas to express opinions or to comment; as catharsis; to use these writing areas to express ideas; or to 11 .

(22) build community forums. Nardi, Schiano and Gumbrecht (2004a) further nuanced these reasons according to “object-oriented activities” – to keep others informed about personal activities; to express opinions in order to influence; to seek feedback; to use the exercise of writing for an audience to stimulate more cognitive input; and outlet for emotional release. Blogging is also frequently characterized as socially interactive and community-like in nature. Not only do blogs link to one another, but some blogs allow readers to post comments to individual entries, giving rise to “conversational”. 政 治 大 journal-type blogs (Blood, 2002b). 立. exchanges on the blog itself. Blood claims that social interactivity is highest in. ‧ 國. 學. Children develop a sense of accomplishment and empowerment when they can create and control the objects around them (Cassell and Ryokai, 2001). Feeling of. ‧. self-efficacy, or the ability to control one’s environment, may have a direct impact on. y. Nat. io. sit. a child’s attention or motivation, and in effect control and regulate behaviors (Calvert,. n. al. er. 1999). Some scholars see digital technologies as a way to enable children to have. Ch. i Un. v. more control and navigation in their learning, mostly through direct exploration of the. engchi. world around them, ways to design and express their own idea, and ways to communicate and collaborate on a global level (Negroponte, Resnick & Cassell, 1997). Like homepages before them, blogs are prominent venues for adolescents to present themselves in textual and multimedia fashion. Weblogs give adolescents the opportunity to “exercise their voices in personal, informal ways, and indirectly promote digital fluency” (Huffaker, 2004). Authors of blogs, like authors of webpages, use the space to communicate and reach an audience (Stern, 2004).. 12 .

(23) Adolescents may be particularly drawn to diary weblogs because of their growing self-consciousness and self-awareness (Steinberg, 2002). During adolescence, individuals may have the egocentric feeling that they are always being watched by an imaginary audience (Elkind, 1967). As Steinberg (2002) said, “The imaginary audience involves having such a heightened sense of self-consciousness that the teenager imagines that his or her behavior is the focus of everyone else’s concern”. Electronic communication exhibits characteristics of both written and informal oral communication. Langellier and Peterson (2004) pointed to blogs as “sort of like”. 政 治 大 there is a continuum ranging from historically familiar forms of communication (such 立. conversation with an approximation of audience feedback. These articles suggest that. ‧ 國. 學. as memoranda or performances) to those that are characteristic of new communication media. Langellier (1998) presented five types of audience for personal narrative. ‧. performance. In this typology, the audience acts as (a) witness testifying to the. Nat. sit. y. experience; (b) a therapist unconditionally supporting emotions; (c) a cultural theorist. n. al. er. io. assessing the contestation of meanings, values, and identities in the performance; (d) a. i Un. v. narrative analyst examining genre, truth, or strategy; or (e) a critic appraising the. Ch. engchi. display of performance knowledge and skill.. A lot of young people spend time meeting their friends after school in cyberspace. Instant messaging services, blogs, chat rooms, e-mail and mobile phones provide many ways to keep in contact and share thoughts and opinions regardless of time and space. But these places sometimes were used to intimidate, offend and harass someone, and parents and educators have little or no idea of what is going on. Just like any other form of bullying, this causes suffering and sadness among the victims. Campbell (2005) research about cyber bully in Australia, found among 120 pupils, 12-13 years old, in Queensland, showed 14 percent described themselves as 13 .

(24) victims of electronic bullying and 11 percent admitted to harassing others online or by mobile phone. According to this research, the harassed teenagers feel ashamed and avoid telling their parents if they fear they would be denied use of the computer or lose their mobile phone. Li (2006) found significant gender differences in cyber bullying. In her survey of 264 Canadian high school students, she found male students more likely to be cyber bullies than female students, 22 compared to 12 percent of the students in the survey. Methods include texting derogatory messages on mobile phones, with students. 政 治 大. showing the message to other before sending it to the victim; sending threatening. 立. e-mails; and forwarding a confidential e-mail to all address book contacts, thus. ‧ 國. 學. publicly humiliating the first sender. Another way to cyber bully is to set up a derogatory web site dedicated to a targeted student and e-mail others the address,. ‧. inviting their comments. In addition, websites can be set up for others to vote on the. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. biggest geek, or sluttiest girl in the school (Snider & Borel, 2004).. Ch. 2.4 Performance on digital stage. engchi. i Un. v. Blogs seem to have developed into a “stage” for those who want to become popular, constituting a new media use context. This use implies that motivations of blog users are different from Internet users who participated in previous studies. Uses and gratifications seem not enough to account for the staging phenomenon. Some blog users turn out to be a diffused audience, the concept from the spectacle/ performance paradigm (SPP). First, users spend increasingly more time in media consumption. Second, such consumption is gradually more woven into the fabric of 14 .

(25) everyday life. Third, the societies have become more performative, through two processes that intertwine: (a) increasing spectacularization of the social world and (b) individual self-perception as narcissistic (Ambercrombie & Longhurst, 1998). As Abercrombie and Longhurst (1998) argue, audience research has not taken account of the changing nature of audience and social processes. There are three types of audience: simple, mass, and diffused, which all coexist. The simple audience involves direct communication from performers to audience. The mass audience reflects the more mediated forms of communication. The diffused audience implies. 政 治 大 increasing amounts of time in media consumption. Thus, the audience interacts with 立. that everyone becomes an audience at all times, which entails people spending. ‧ 國. 學. the form of mediascapes rather than with media messages or text per se. To examine the performance of media audiences properly, Abercrombie and. ‧. Longhurst (1998) developed the SPP. As they explained, the SPP foregrounds the. y. Nat. io. sit. notion of identity; being a member of an audience is intimately bound with the. n. al. er. construction of the person. Within the SPP, spectacle and narcissism are interwoven. Ch. i Un. v. with the notion of the “diffused audience,” which is significantly different from. engchi. “simple” or “mass audiences” –two earlier concepts of audience performance. The diffused audience exists in a media-saturated environment. Within the SPP, performance becomes so pervasive that the diffused audience takes part in the performance, blurring the boundary between audience and performer. Media become a resource that audiences can use to formulate their performances in “everyday” activities, and daily life transforms into a “constant performances” (Abercrombie & Longhurst, 1998,) in which diffused audience members perceive themselves as performers as well as audience.. 15 .

(26) According to Abercrombie and Longhurst (1998), the diffused audience is driven by the concepts of spectacle and narcissism. Spectacle is the idea that everything is a framed performance that should be gazed on, possessed, or controlled. As a performance, spectacle is an elaborate exhibition of surfaces for the audience; often there is little detail or substance involved in such exhibitions. Spectacle teaches the audience how to view the world, as well as how to perform. Everyday life becomes dominated by images—life seems to be transformed into art that can be possessed by the audience. Narcissism, the other part of the diffused audience, is the self-centered or self-oriented nature of the individual that comes from a long affiliation with. 治 政 spectacle. Narcissism is characterized by celebrity worship, 大 absence of a sense of the 立 past or the future, and preoccupation with instant gratification. Spectacle combined ‧ 國. 學. with narcissism guides diffused audiences toward ways to perform in everyday life.. ‧. The individual is self-centered and exists in a world in which everything can be. y. sit. io. n. al. er. Longhurst, 1998).. Nat. possessed, including the individual and her or his performances (Abercrombie &. i Un. v. The Internet has become an integral part of daily life in today’s sociotechnical. Ch. engchi. environment. In the view of Amichai- Hamburger and Furnham, the Internet brings numerous positive benefits to our lives, such as enhancing the quality of life and well-being of marginal groups, constituting social recognition of individuals, and improving relationships of intergroups (Amichai-Hamburger & Furnham, 2007). Self-disclosure is communicating with others using one’s own information, including personal thoughts, feelings, and experiences, for the purpose of sharing (Derlega, et al, 1993). According to Wheeless and Grotz (1976), self-disclosure consists of multiple dimensions, including (a) intention, (b) amount, (c) positive/negative matter, (d) depth, and (e) honesty and accuracy. 16 .

(27) Self-disclosure is important to social integration, which refers to the evaluation of one’s relationship quality to society and community (Keyes, 1998). Cohen (2000) has pointed out that social integration relies mainly on the diversity of relationships in which one participates. When people share their deep thoughts, such as feelings of trauma, pressure, and depression, with others belonging to the same community, they may acquire social support and improve their integration with society (Pennebaker, 1997). Niederhoffer and Pennebaker (2002) also report that self-disclosure by writing can produce the positive benefits of social integration.. 政 治 大 themselves through words, pictures or other creations? How much things do they 立. In this research, researcher takes blog as a digital stage, how do children perform. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. want to share with their friends or cyber friends, and what that means to them?. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.5 Children’s Digital bedroom culture. al. Generations of adolescents have used their bedrooms as sites of refuge and. n. iv n C spaces in which they can express and their identities. These sites of identity h eexplore ngchi U formation are filled with cultural products and pathways to the world outside the home. Children’s bedrooms are increasingly becoming media centers (Roberts, Foehr, Rideout & Brodie, 1999; Livingstone, 1999; Stanger & Gridina, 1999). The increasing diversity of media targeted specifically to adolescents allows young audiences greater specificity in choosing media that suit their moods and their passing interests, often in isolation from other family members (Arnett, 1995). The idea of being a girl’s bedroom culture was first coined by McRobbie and Garber (1991) to address the invisibility of girl’s as subjects in youth-based subculture 17 .

(28) studies. They considered girls to be “negotiating a different space” and to be “offering a different type of resistance” from the boys. Girls’ subcultures, especially those of younger girls, tended to be based inside the home and comprised activities such as reading magazines, listening to music (Firth, 1983), talking on the telephone, playing with two-way radios (Griffiths, 1995), and so on. The location of these activities was largely the result of parental control, whereby girls’ actions and activities were restricted more to the private sphere of the home, while allowed more freely to roam in the public space of the street (McRobbie, 1991; Nava, 1992).. 政 治 大 Buckingham (1998) to account for the physical location of many children’s cyber play. 立 The idea of a “digital bedroom” was coined by Julian Sefton-Green and David. ‧ 國. 學. They observed that whether it be computer game play, surfing the web, or homepage construction, this is usually done on a home computer, the site of which, as. ‧. Sefton-Green and Buckingham observe (1998) is often a computer in someone’s. io. sit. y. Nat. bedroom.. n. al. er. The graphics and image on girl’s homepages often resemble or represent the. Ch. i Un. v. kinds of material culture stored in their bedrooms. If their physical bedrooms contain. engchi. informal collections of treasured objects, their websites are often (immaterial) or virtual collections of images, representing the kinds of objects stored in their rooms, or images of wish-lists, or stylized or even idealized images of objects (Mitchell and Reid-Walsh, 2002). The spread of cell phones, and communications through the Internet, especially in the last ten years, marks a real change. These devices are not just two more items in a list of cultural products aimed at and loved by young people. They create a new map of domestic life, giving children the official right to develop social links with friends away from home and without parental regulation. Though it is too early to know what 18 .

(29) the consequences of this new phenomenon will be, but still can guess they will seriously affect the relational balance between parents, their children, and their children’s peer (Pasquier, 2008). Interactive communication through the Internet soon made anonymous contacts between people possible, and teens became very fond of such chats and, to a lesser degree, forums. This type of interaction has gone through an interesting change recently with the development of instant messaging and blogs. Those are not just two more technological modes of communication: they are based on a different. 政 治 大 Instant messaging proposes a ‘club’ formula of links. Either with people you have 立. conception of electronic interaction, both functioning as a kind of elective sociability.. ‧ 國. 學. already met or with friends and acquaintances recommended by those people. Blogs with their blog rolls giving links to other blogs and thus making it easy for bloggers to. ‧. connect with each other. For the moment, children are careful to keep parents out of. Nat. sit. y. these exchanges. Whether anonymous or with friends, parents no longer know who. n. al. er. io. their children are interacting with (Pasquier, 2008).. Ch. i Un. v. McNamee (2000) considered the space of children’s video game play in their. engchi. bedrooms as a strategy for negotiating and resisting spatial boundaries. She considers video-game play to be a kind of heterotopias. Although children are located in a real place (their bedrooms) and engaging with a real machine (the computer), the space where they experience the adventure is not there but in one of Foucault’s “other spaces”. In the discussion, I apply Foucault’s ideas to the children’s blog both as a concept and as a structural principle. Foucault’s (1968) article “Of other spaces” provides a brief historical overview of the Western sense of space, and presents some ideas that can be applied to our understanding of the web, and to the phenomenon of the blog. Foucault begins his 19 .

(30) discussion by stating how in the medieval period, space was conceived of as hierarchical set of places which were set in opposition to one another. He called this sense of space the space of “emplacement” (1986: 22). Foucault considers but does not elaborate on the space in which we live by examining sites in terms of the sets of relations that may define them. For example, he observes that there are sites of transportation (streets, trains, etc.), sites of temporary relaxation (cafes, beaches, etc.), and closed or semi-closed sites of rest (house, bedrooms). However, his main intention is to analyze sites that exist in relation to other sites, but in ways that “suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations they designate, mirror or reflect”. 治 政 (1986: 24). He distinguishes two main types: utopia and 大heterotopias. Utopias are by 立 definition sites with no place, unreal spaces that present society in its perfected form. ‧ 國. 學. This may be in a direct or inverted relation to the way society is. Heterotopias are, by. ‧. contrast, places that do exist, real places, but they are also counter-sites, a “kind of. sit. y. Nat. effectively enacted utopia.” These sites exist outside of all places, although they exist. io. n. al. er. in reality (1986: 24).. i Un. v. In his elaboration of the idea of heterotopias, Foucault enumerates five principles.. Ch. engchi. First, he considers heterotopias to be present in all cultures in all periods, although they take different forms. In early or “primitive” societies he considers there to be a type he calls “crisis heterotopias” which are “privileged or sacred or forbidden places reserved for people in crisis, such as adolescents, menstruating women, pregnant women, the elderly. He sees these as being replaced in more complex societies by “heterotopias of deviation” such as prisons, rest homes, psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes (1986: 24-5). The second principle is that a society as it changes can make an extant heterotopias function differently. The example he cites is of the cemetery which until the end of the eighteenth century was located in the center of a 20 .

(31) town, next to the church, but then, to mirror changing views of death was moved to the outskirts of town (1986: 25). The third principle Foucault considers to reside in heterotopias is how they can juxtapose in a single “real space” several sites that are themselves incompatible, such as in a cinema, which in a rectangular space has a two-dimensional screen on which three-dimensional space is projected, and a garden, the microcosm of the Earth, and its representation, the carpet (1986: 25-6). The fourth principle he lists is that heterotopias are often linked to slices of time: either indefinitely accumulating time such as in museums and libraries, or the obverse, transitory time such as fairgrounds and vacation villages. The fifth principle he. 治 政 describes about heterotopias is that they “presuppose a大 system of opening and closing 立 that both isolates them and makes them penetrable.” He states how heterotopias are ‧ 國. 學. not usually “freely accessible, like a public place” (1986: 26). He develops an analysis. ‧. of a type of bedroom on great farms in South America that provides entry to travelers. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. yet denies them access to the family. He describes these rooms in the following way:. Ch. i Un. v. The entry door did not lead into the central room where the family lived, and. engchi. every individual or traveler who came by had the right to open this door, to enter into the bedroom and to sleep there for a night. Now these bedrooms were such that the individual who went in to them never had access to the family’s quarters; the visitor was absolutely the guest in transit, was not really the invited guest. (Foucault, 1986: 26). Foucault concludes his discussion by stating that heterotopias exist in relationship to all other spaces, either as an illusionary space that reveals others to be 21 .

(32) more so, such as brothels, or to create an ideal but real space that is the opposite of life “as perfect, as well arranged as ours is messy.” He calls these spaces “compensatory” and gives as examples the Puritan colonies of North America, and the Jesuit settlements of South America. In the example Foucault provides is that of the ship, “a floating piece of space, a place without a place that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea”. (1986: 27). 2.6 Children and Identity. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. A key development task for children and youth involves relationship formation with others (Bowlby, 1969). From these social experiences, sense of self emerges and. ‧. develops over time and individual needs are fulfilled, such as companionship and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. being part of a group (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Harter, 1999).. al. One of the most important developmental challenges of adolescence, from the. n. iv n C developmental psychologists,U is identity hen gchi. perspective of most. formulation, the. cultivation of a conception of one’s values, abilities, and hopes for the future. In cultures where media are available, media can provide materials that adolescents use toward the construction of an identity (Swidler, 1986). Valentine and Holloway (2002) have investigated how children use ICT and what part it plays in the construction of their identities. Using questionnaires, diaries, focus groups, semi-structured interviews and online interviews, they show how children reconstruct and reconfigure their social relationships and identities in online spaces. Their main conclusion is that ‘their virtual activities are not in practice, 22 .

(33) disconnected from their off line identities and relationships . . . on-line and off-line identities are not oppositional or unconnected but are mutually constituted’ (Valentine and Holloway, 2002:316). They identify a number of processes through which ICT activities and the children’s everyday lives are mutually constitutive. For example, online identities are contingent upon and/ or reproduce already present class and gender inequalities. Information gleaned through online activities is incorporated into their offline ones (for instance, by feeding into their hobbies and interests. It is also clear from this work that different children use the internet in different ways:. 立. 政 治 大. For some children it emerges as a tool to develop intimate on-line friendships,. ‧ 國. 學. while for others it emerges as a tool of sociality that develops everyday off-line social networks; for some it emerges as an important tool for developing off-line. Nat. (Valentine and Holloway, 2002: 316). n. al. er. io. sit. y. ‧. hobbies, and for others as a casual tool for larking about.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In the digital world, the performance of identity is divorced from a direct interaction with these cues from the physical, and instead relies upon the texts we create in the virtual worlds we inhabit. These texts are multiple layers through which we mediate the self and include the words we speak, the graphical images we adopt as avatars to represent us, and the codes and other linguistic variations on language we use to create a full digital presence. Lemke (1998) points out the complexity of identity as it is performed and lived through texts in cyberspace, with his words:. 23 .

(34) The ultimate display medium is reality itself, what we see, hear, touch and fee; what we manipulate and control; where we feel ourselves to be present and living . . . A fast enough computer can simulate reality well enough to fool a large part of our body’s evolved links with its environment. We can create virtual realities, and we can feel as if we are living in them. We can create virtual realities, and we can feel as if we are living in them. We can create of full presence . . . We can change by acts of will . . . we can be the sorcerers of our dreams and our nightmares. . . . What is literacy when the distinction between reading and living itself is nominal? When a reality becomes our multimedia text . . .?. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. (Lemke, 1988: 298-299). sit. y. Nat. Using ideas from Agger (2004), Butler (1999), and Grosz (2004) Thomas (2007). io. er. contend that identity is always about the body, and the bodily states and desires of. al. being (the historical and natural aspects of the body), becoming (aging through the. n. iv n C temporality, more and wise h e knowledgeable ngchi U. natural forces of. as we learn and. experience the world, and growing with the playing out and accomplishment of fantasies and ideals we aspire to, belonging (our set of beliefs and ideologies, and the people and groups we align ourselves with), and behaving (entering into the discourses associated with the roles we adopt across the social spheres which we inhabit). Stemming from this, identity is characterized by aspects of self, others and community. Thomas (2007) stated that there are a number of interlinking characteristics to be considered about the performance of identity in online spaces: 24 .

(35) 1. The ways in which we perform aspects of the body: gender, age, race, ethnicity, and the ways in which we select some aspects to perform and exaggerate, while others we silence or hide. 2. The ways in which we perform, disclose and reveal emotions: happiness, sadness, insecurity, loss, grief, humour, pleasure, delight: these too are aspects of the body. 3. The ways in which we demonstrate affiliation and relationships to others, marking our desire to align, develop kinship with another, and to belong in the sense of belonging to a friendship.. 學. ‧ 國. 4.. 治 政 The ways in which we appropriate various cultures, 大symbols and texts to produce 立 an intertextual self, one which performs and creates a sense of belongingness to certain communities, ethoses, politics and groups.. ‧. 5. The ways in which we adopt certain storylines and discourses, in purely social. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. contexts, and in imaginative role-playing and online gaming.. Ch. engchi. i Un. (Thomas, 2007: 8-9). v. Lacan (1977) developed some of Freud’s notions about the relationship between the subject and signification as they pertained to children’s development of a sense of ‘self’. When children first come to the notion of ‘selfish’ and first understand themselves to be separate identities from ‘others’. Lacan claims they start to see the ‘image’ of themselves from outside of themselves, just as if they see themselves in a mirror. He calls this ‘mirror stage’, and believe, ‘… the mirror stage … manufactures for the subject, caught up in the lure of special identification, the succession of fantasies that extands from a fragmented body-image to a form of its totality’ (Lacan, 25 .

(36) 1977: 4). During the mirror stage, the child identifies with its integrated ‘whole’ mirror-image. Through the process of socialization, the child views these discursive images of ‘who’ it is, and comes to recognize itself as ‘self’ through this ‘specular image’ (Lacan, 2000). The child misconstrues itself to be that specular image which is not itself, but a reflected specular image of self, something that is ‘other’ than itself. This creates an alienated sense of ‘self’ which is based on fiction, fantasy and desire, a mis identification of self in which:. 政 治 大. This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child … would seem to. 立. exhibit in an exemplary situation … in which the I is precipitated in a primordial. ‧ 國. 學. form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of the identification with the other, and before language restore to it, in the universal, its function as subject … this. ‧. form situates the agency of the ego before its social determination, in a fictional. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. direction.. Ch. n engchi U. iv. (Lacan, 2000: 45). Bruckman (1994a, 1994b, 1997), Landow (1998), and Jakobsson (1990) argue that children are embracing cybercultures, so much so that living, composing, co-creating, coding and reading and texts of cyberspace have become a significant pastime for a new generation. Computer culture has become a more widely desired recreational activity. As video gaming comes online and invites children to play games against unknown challengers across the world, child participation in online communities is growing at an explosive rate. Cyberspace provides children a space to build up their identity or an identity that 26 .

(37) haven’t appeared in their everyday life. In this research, researcher is trying to find out how children experience this process, and how other people (friends) see this.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 27 . i Un. v.

(38) Chapter 3: Methodology. Reading youth means interpreting youth behavior, hypothesizing youth values and worldviews, and analyzing the trends and transformations of youth cultures. Reading youth writing means recognizing young people as social actors and cultural producers and as innovators of cultural change.. 政 治 大 saying, writing and producing, the mixture of so called youth voice. 立. Reading youth means taking a long and critical look at what young people are. ‧ 國. 學. In this research, to explore children’s blog usage, a qualitative study was taken from July 2009 to June 2010. Exploring everyday life of children; where they go,. ‧. what they do, how, when and why they use blogs, and the relationship between blog. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. and their privacy practices.. n. Three methods were used to gather data: participant observation, interviews and documentary data.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3.1 Research Methods. Ethnography means, literally, a picture of the ‘way of life’ of some identifiable group of people. Conceivably, those people could be any culture-bearing group in any time and place. In times past, the group was usually a small, intact, essentially self-sufficient social unit, and it was always a group notably ‘strange’ to the observer. The anthropologist’s purpose as ethnographer was to learn about, record, and 28 .

(39) ultimately portray the culture of this other group. Anthropologists always study human behavior in terms of cultural context. Particular individuals, customs, institutions, or events are of anthropological interest as they relate to generalized description of the life-way of a socially interacting group. Yet culture itself is always an abstraction, regardless of whether one is referring to culture in general or to the culture of a specific social group (Wolcott, 1988). 3.1.1 Participant Observation Participant observation can provide information important to the successful. 政 治 大. implementation of on-line research. It allows researchers to gain a better. 立. understanding of participants’ ranges of performances and the meaning those. ‧ 國. 學. performances have for them (Kendall, 1999). During research period, researchers observed these two participants’ weblog usage and also observe their weblog. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 3.1.2 Interview. ‧. interaction.. i Un. v. Interview is one of the main data collection tools in qualitative research. It is. Ch. engchi. very good way of accessing people’s perceptions, meanings, definitions of situations and constructions of reality. It is also one of the most powerful ways we have of understanding others. Semi- structured interview enable a better understanding of the weblog usage of children, as well as its meanings and variation as they appear in the culture and living environment of children. The interviews were conducted in their family house, school, fast food restaurant and cram school. 3.1.3 Documentary Data For ethnographers, documentary products provide a rich source of analytic topics, which include: how are documents written? How are they read? Who writes them? 29 .

(40) Who reads them? For what purposes? On what occasions? With what outcomes? What is recorded? What is omitted? What does the writer seem to take for granted about the reader? What do readers need to known in order to make sense of them (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1995)? In this study, participants were asked to record their daily media usage by self-report, this can help researcher to collect more information of their daily life.. 3.2 Reliability and Validity of Qualitative Research. 政 治 大 Reliability and validity 立is the center of all research projects. In qualitative. ‧ 國. 學. research, researchers adopt the principle of reliability and validity, but seldom use such terms, as they have much to do with quantitative surveys. The reliability in. ‧. qualitative research refers to trust or consistence. Researchers make use of many. Nat. sit. y. techniques, including interviews, participation, photos, documents research and so on,. n. al. er. io. in order to record their observations as usual and reach consistence. The researcher. i Un. v. acts as a tool in qualitative research, emphasizing its unique uniqueness. Therefore,. Ch. engchi. different research conclusions will be reached because of different researchers, even on the same question in the same group in the same place and at the same time (Chen, 2006).. The validity in qualitative research focuses on the social reality construction process and people’s experience and explanations in given social culture (Chen, 2006). Here, validity means truth — its core principle, also the bridge between concepts and materials. In other words, what researchers concerns much is how to describe social life truly, and such description should be in agreement with the interviewees’ experience (Neuman, 2006). Most qualitative research focuses on how to master 30 .

(41) professional opinions and offers specific explanations, showing the feelings and understanding of the interviewee on something.. The possible mistaken factors in the research process are called “threats to validity”. While in qualitative research, threats to validity cannot be recognized ahead and be excluded through some techniques (Chen, 2006). That is because the object in qualitative research is not individual objective substance separated from the subject. It cannot be recognized or confirmed just in one-way, and can only be reconstructed in the interaction with its subject. Therefore, validity can only be inspected here and now or gradually in the process.. 立. 政 治 大. There are several specific methods to inspect validity and exclude the unwanted.. ‧ 國. 學. This research adopts the triangulation. Triangulation means that the same conclusion. ‧. will be inspected on different persons in the case in different methods, background. sit. y. Nat. and time, in order to inspect the established conclusion through possible channels,. io. er. thus to seek the most validity on the conclusion (Chen, 2006). The most typical. al. n. inspecting method is the combination of interviewing and observing. The observation shows us the behavior of. iv n C interviewees U h e n gandc hthei interviews. help us to learn the. motivations of their behavior. To conduct relevant inspections, the researcher can not only inspect the observed results in the interviews, but also inspect the interviewing results in observation.. 3.3 Research Procedures 3.3.1. Participate in the Observing Process In this research, there are two parts in observation participation. One is to enter 31 .

(42) children’s home, observing children using digital media in the form of fieldwork. The other is to observe the documents children put in their blogs and the interaction they conduct in blogs with others. 3.3.1.1 Observation at Home Given that home is where children use media mostly and use computers to surf the Internet most of the time, we should enter children’s home to learn blog activities featuring children and observe the network they form in the activities. 3.3.1.2 Observation Fields. 政 治 大 fields. At present a blog can 立be divided into four main parts: personal information,. In terms of research fields, this research makes children blogs as observation. ‧ 國. 學. albums, journals and the message board. Through the observation of researcher and children’s narration when doing focus group research, this research focuses on the. ‧. albums and journals in blogs.. sit. y. Nat. 3.3.2 Interview. n. al. er. io. This research studies children’s blog experience through interviews, in order to. i Un. v. know how children create self-images and interact with others. Researcher adopts. Ch. engchi. semi-structured interviews, because this can lead to surprising answers and maintain the openness of research questions. Therefore researcher needn’t ask questions strictly according to the interview outline. Once new information appears, researcher can adjust interview outline thereafter, which is beneficial to catch the subtle differences among individual cases. It lasted around 1.5 hours for each interview. Sometimes parents would accompany their children and sometimes children themselves received the interviews. The interviewing places included cram schools, homes or fast food restaurants where children would stay. 32 .

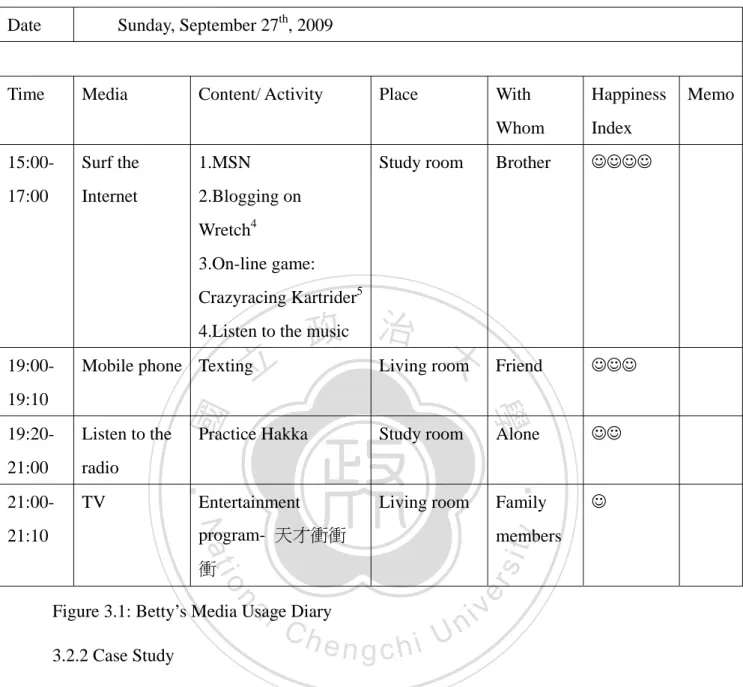

(43) In the process of the interview, the researcher plays a role of a positive listener, listening attentively to the interviewee’s blog using experience and trying to understand it. In the listening process, involvement or interruptions should be avoided as possible. According to what the interviewee was saying, the researcher should soon judge whether there is more to continue or extend and ask “What’s your opinion?” or “Can you tell me what happened?” at the right time, thus letting the interviewee offering more information. According to what the interviewee was saying in the process, the researcher should make some gestures to mean the attention and response. When the interviewee feels the attention of the researcher, there will be deeper narration on the experience.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 3.3.3 Documentary Data. In this research, researcher designed a ‘Media Usage Diary’ (Appendix 5) for. ‧. participants to record their daily media usage. In the beginning, researcher explains. y. Nat. io. sit. “media” for participants, then tell them to record each media usage every day. On the. n. al. er. ‘Media Usage Diary’ participants can indicate their happiness index while using each. Ch. i Un. v. medium. Five smiling faces (☺) represent the happiest feeling when using the medium.. engchi. ‘Media Usage Diary’ can help researcher to study how media involve in children’s everyday life.. 33 .

(44) Sunday, September 27th, 2009. Date. Time. Media. Content/ Activity. 15:00-. Surf the. 1.MSN. 17:00. Internet. 2.Blogging on. Place. Study room. With. Happiness. Whom. Index. Brother. ☺☺☺☺. Friend. ☺☺☺. Wretch4 3.On-line game: Crazyracing Kartrider5. 政 治 大 Living room. 4.Listen to the music. 立. Mobile phone Texting. Listen to the. 21:00. radio. 21:00-. TV. Practice Hakka. Study room. Entertainment. Living room. Alone. ‧. 19:20-. 學. 19:10. ‧ 國. 19:00-. Family. Nat. sit. members. n. er. io. 衝. al. Figure 3.1: Betty’s Media Usage Diary 3.2.2 Case Study. ☺. y. program- 天才衝衝. 21:10. ☺☺. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The case selection of qualitative research is based on the uniqueness of the cases. It is supposed that researchers should select cubic cases, thus to describe real multi faces of society. To select suitable cases, researchers mostly base on their experience or the understanding of theories to design the sampling (Hu Youhui, Yao Meihua, 4. Wretch (Chinese: 無名小站) is a Taiwanese community web site. In Chinese, its name means Anonymous Site or Nameless Station. It is the most well-known blog community in Taiwan with thousands of users registered. Wretch provides free album, blog, and Bulletin Board System hosting services. (Retrieved June 20th ,2010 from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wretch_website) 5 Crazyracing Kartrider (Chinese: 跑跑卡丁車) is an online multiplayer racing game that has managed to get well over 230 million users playing. (Retrieved June 20th ,2010 from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crazyracing_Kartrider) 34 . Memo.

(45) 1996). Qualitative research is often in changes, so any new information may break the temporary assumption. The sampling strategy will accordingly be adjusted with the development of research (Hu & Yao, 1996). As the method of qualitative research is applied to motive research objects, it is possible for researchers to adopt suitable sampling strategy as to reality in different research phases. To maintain the openness and compliance of research questions, flexibility and mobility of the research, this research adopts snowball sampling strategy to select the cases.. 政 治 大 uncertain parent substance (Babbie, 1998). Researchers should have a quite good 立. Snowball strategy is also named chain strategy, applied to the situation of. ‧ 國. 學. knowledge of the known blog users, and then they can find other interviewees through them (Hu & Yao, 1996).. ‧. Researcher looks for children interviewees with Internet experience among. sit. y. Nat. relatives and students researcher have taught. Cases selected through such procedure. n. al. er. io. are not so typical, but can offer very useful information. Therefore it is often adopted. i Un. v. by exploring research (Babbie, 1998). In the beginning of the research, from June to. Ch. engchi. July 2009, using the focus group method, invited 12 children in 3 groups who knew each other to have an informal discussion. Thus free group interaction atmosphere was created for children to speak frankly and share their experience. During this phase, researcher sets up the core themes according to the experience children shared on using digital media, and then sought suitable cases for further research. Researcher conducted the first face-to-face interview on 11 August 2009. Before each interview, researcher would explain the research orientation to interviewed children and their parents, and record the interviewing process with a recorder. As children are below 18 years old, researcher signed agreement with parents, promising 35 .

(46) to keep the interviewees’ identity secret. The interviews would only begin after the interviewees agreed. These two participants were sixth grade elementary school students, aged 11-12. These two participants, the girl used to be researcher’s cram school student; the boy was recommended by family friend. Both participants’ parents admitted researcher’s field study in their house and agree researcher to study participants’ blog and conduct the interviews.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 36 . i Un. v.

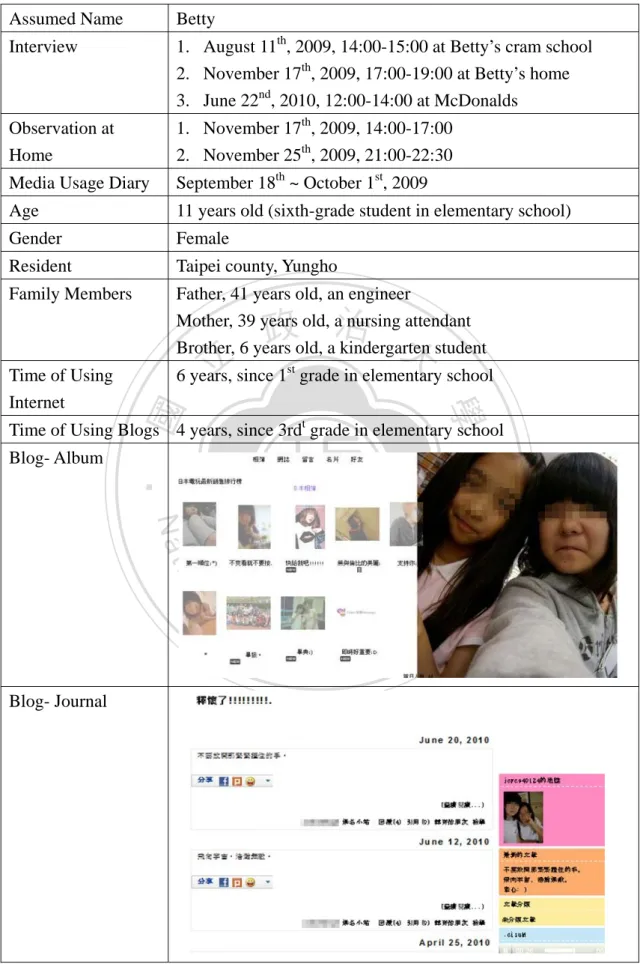

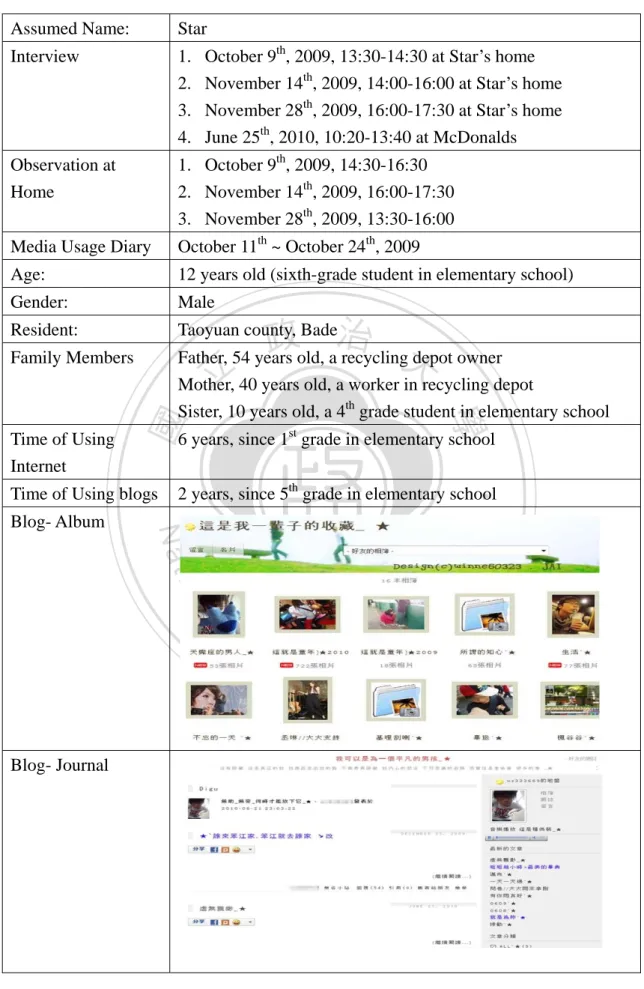

數據

Outline

相關文件

衛福部 17 日召集臨床醫學、小兒醫學以及感染科專家,審查 6 到 11 歲兒 童使用莫德納疫苗案,經整體評估有效性及安全性,並考量國內緊急公共衛生 需求後,通過莫德納疫苗的授權。 6

學習活動 討論、角色扮演、專題講座 經驗分享、 訪問 、 資料蒐集 學習材料 兒童故事、兒歌、古詩 圖書 、日常生活經驗

童工是指在工作場合下僱傭兒童,剝奪兒童的童年成 長,干預他們正常上學,在精神、身體、社交或道德 上造成威脅或損害。非洲 5-17

To enable pre-primary institutions to be more effective in enhancing school culture and support to children, actions can be taken in the following three areas: Caring and

數學桌遊用品 數學、資訊 聲音的表演藝術 英文、日文、多媒體 生活科技好好玩 物理、化學、生物、資訊 記錄片探索 英文、公民、多媒體 高分子好好玩 物理、化學、生物

Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH).

Mount Davis Service Reservoir Tentative cavern site.. Norway – Water

For example, both Illumination Cone and Quotient Image require several face images of different lighting directions in order to train their database; all of