論世界語言中分類詞與複數的共現 - 政大學術集成

112

0

0

全文

(2) On the Co-occurrence of Numeral Classifier and Plurality Marker in Languages of the World. BY. 立. 治 政 大 Yun-Ju Chen. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 sit. y. Nat. io. er. A Thesis Submitted to the. al. n. Graduate Institute of Linguistics. C h Fulfillment ofUthen i in Partial engchi. v. Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. January 2013.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. Copyright © 2013 Yun-Ju Chen All Rights Reserved. v.

(4) Acknowledgements 誌謝 哇!論文終於完成了,有種難以言喻的感動!!感謝一路上相伴的大家!!首先最 感謝的是啟蒙這篇論文的指導老師,何萬順老師。從老師的期刊文章裡得到本篇 論文的想法,老師也每每在我遇到瓶頸時,能指引我方向,讓我的思考轉彎,尤 其是在最後的論文口試的前幾天,就在那緊張的時刻,在我煩惱著為什麼我的 powerpoint 跟 proposal 時那麼類似,心裡想說這樣講真的好嗎?就在這個時刻收 到老師的 email,提醒我必須點出重點,讓口委能看到本篇的貢獻,有了老師的 指導,讓我及時修改,順利完成口試,真的是相當的感謝老師。同時也要謝謝兩 位口試委員,張郇慧老師及謝富在老師。感謝兩位老師對論文提供的寶貴意見, 讓我能做更細部的修改、讓論文更完整,而兩位老師親切的態度,也讓我在口試 時,安心不少,謝謝你們! 接著要感謝我的兩位心靈輔導老師,昭汝跟尚儒。謝謝昭汝,總是在我壓力. 政 治 大 大到爆炸時講笑話給我聽,在我遇到困難時,給我很多實用的建議,也在我每次 立 meeting 前給我相當大的鼓勵,讓我心臟稍稍變強壯,謝謝妳,我會永遠記住妳 ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 說的“Keep your head up. You are so much better than you believe. You can do this. I promise”。謝謝尚儒以過來人的身分鼓勵我,讓我能一步一步地往前邁進,讓我 知道大家可以做到的,我也一定可以!接著是唯一跟我一起到台北打拼的靚芸, 謝謝妳陪我玩透台北,也謝謝幸好妳在台大,讓我可以順利借到許多資料,雖然 妳有時候已經不耐煩了,但是我知道妳人最好了!!. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 再來要謝謝親愛的研究所同學們!我的室友婉君,謝謝妳總是在我身陷苦海 的時候,聽我在妳背後哀嚎,雖然妳總是一派鎮定,但是幸好有妳,才讓我沒有 孤單的感覺、有發洩的管道。我最佳的玩伴,蜜珊,妳不只是我的酒肉朋友喔, 妳總會在我有急難時,義不容辭地陪著我,尤其是在提 proposal 前,在我緊張到 心臟要跳出來時,即使妳前一天熬夜到快沒力,還是陪著我、聽我演練,真是就 甘心!!謝謝亭伊、王緯、景芃、培禹,謝謝妳們不時的關心我,給我鼓勵,讓我 更有信心去完成論文。另外還要謝謝同門的師兄姐們,昆翰、宛君、婉婷、心綸, 謝謝你們讓我更了解論文該如何進行、指引我方向。 另外我也要感謝提供我語料的各位作者以及兩位母語人士,如果沒有你們的. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 幫忙,這篇論文的資料無法完整,謝謝你們不吝於提供資訊!也謝謝電腦小神童 澔宜、校稿小達人庭芬,謝謝妳們在我最後緊急修論文的時候,幫忙我許多!謝 謝陪伴我兩年的所辦助教,惠玲學姊,謝謝妳在所辦工讀時對我的照顧,謝謝妳 在我被論文壓扁的時候鼓勵我,我會想念妳的!! 真的很感謝陪我走過這段路的大家,沒有你們的鼓勵,沒有你們給我信心, 我實在是無法走到這步!雖然之後你們不一定會在我身邊,但是謝謝你們,這段 路,有你們真好!!. iv.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... v Tables & Figures ......................................................................................................vii Chinese Abstract .................................................................................................... viii English Abstract .......................................................................................................... ix CHAPTER 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Motivation and Purpose ................................................................................... 3 1.2 Organization of the Thesis ............................................................................... 7 2. Literature review...................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Classifiers and Plurals: Complementary Distribution.................................... 10 2.1.1 Greenberg (1972) ................................................................................ 10. 政 治 大 2.1.2 Sanches and Slobin (1973).................................................................. 11 立 2.1.3 Chierchia (1998) ................................................................................. 12 ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.1.4 T’sou (1976) ........................................................................................ 13 2.2 Classifiers and Plurals: The Same Category .................................................. 13 2.2.1 Borer (2005) ........................................................................................ 14 2.2.2 Her (2012a) ......................................................................................... 15 2.3 Previous Studies on Specific Languages ....................................................... 16. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 2.3.1 Chinese................................................................................................ 17 2.3.2 Japanese .............................................................................................. 19 2.4 Syntactic Analysis of Nominal Structure ....................................................... 21 2.5 Remarks ......................................................................................................... 23. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3. Defining Classifiers and Plurals ........................................................................... 25 3.1 Definition of classifiers .................................................................................. 25 3.2 Definition of Plurals ....................................................................................... 29 3.2.1 Transnumerals ..................................................................................... 31 3.2.2 Additive/ Associative Distinction ....................................................... 33 4. Analysis ................................................................................................................... 35 4.1 Data Analysis in Languages ........................................................................... 36 4.1.1 Mandarin Chinese ............................................................................... 36 4.1.2 Japanese .............................................................................................. 40 4.1.3 Obligatory classifier languages ........................................................... 43 4.1.4 Optional classifier languages .............................................................. 62 4.2 A Coordinator Representation of Language Distribution .............................. 78 4.3 Syntactic Analysis .......................................................................................... 82 v.

(6) 4.4 Possible Explanations .................................................................................... 86 5. Conclusion .............................................................................................................. 89 5.1 Summary ........................................................................................................ 89 5.2 Limitations and Suggestion............................................................................ 89 Reference .................................................................................................................... 92 Appendixes Appendix A: The Categorization of 22 Languages in WALS Online Database ........ 102 Appendix B: The Relation of Numeral Classifiers and Plural Markers .................... 103. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i Un. v.

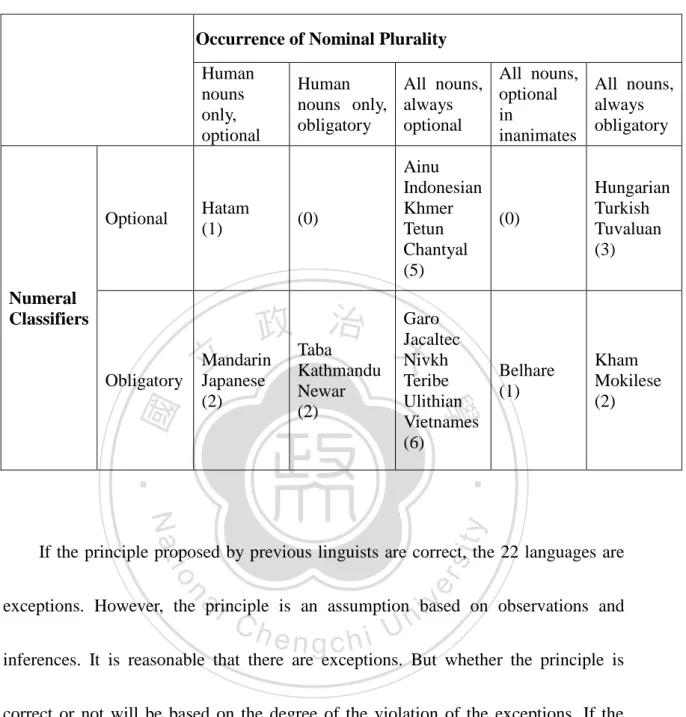

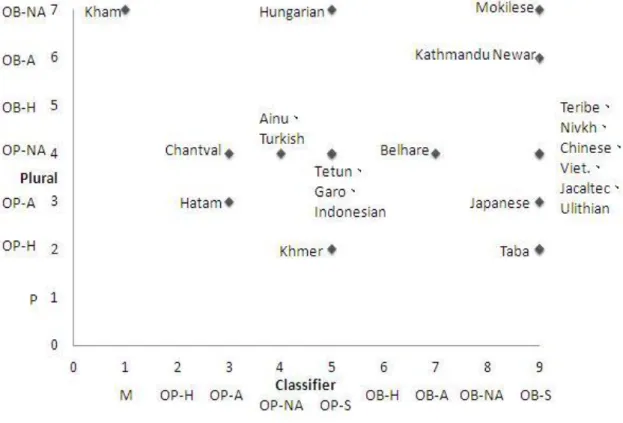

(7) TABLES Table 1. Numeral Classifiers and Nominal Plurality ..................................................... 4 Table 2. Numeral Classifiers and Nominal Plurality in 22 Languages .......................... 5 Table 3. The Categorization of Co-occurrence ............................................................ 80 Table 4. Language Categorization ............................................................................... 81 Table 5. The Phenomenon Involved in the Complementary Distribution of Classifiers and Plurals ...................................................................................................... 83 FIGURES Figure 1. The Range of Application of Classifiers and Plurals .................................. 78. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v.

(8) 國立政治大學研究所碩士論文摘要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:論世界語言中分類詞與複數的共現 指導教授:何萬順博士 研究生:陳韻如 論文提要內容:(共一冊,19,083 字,分五章). 政 治 大. 在過去的研究中,學者們指出分類詞與複數常常呈現互補分佈的關係,當其. 立. 中一個的出現為必要時,另一個通常為非必要。另外更有學者聲稱分類詞與複數. ‧ 國. 學. 在句法結構上佔據同一個句法位置,因此是同一個句法成分。然而,另也有學者. ‧. 發現兩者其實是可並存的。在 Gil (2008) 跟 Hasplemath (2008) 所共同研究到的. Nat. io. sit. y. 114 個語言中,有 22 個語言同時具有分類詞與複數。本論文的目的即在於探究. er. 這 22 個語言的分類詞與複數之間的關係,藉此去論斷兩者是否呈現互補,是否. al. n. iv n C hengchi U 為同一句法成分,而兩者之共現情形,則是相當重要的判斷依據。. 22 個語言的資料顯示出,當語言同時出現分類詞與複數時,其使用範圍大 多呈現互補分佈的關係,而分類詞與複數共現於一個名詞詞組的情形,並非少數。 由於這 22 個例外的語言並非完全違反互補分佈之宣稱,因此分類詞與複數應為 同一個句法成分,而其共現於同一名詞詞組的情形應為分岔的句法結構,此結構 可能由兩種原因所造成,一為語言接觸,一為語言變遷。所以,這 22 個原為例 外的語言,其實大多仍符合語言的普遍現象。 viii.

(9) Abstract The relationship between numeral classifiers and number plurals has been examined by several linguists (Greenberg 1972, Sanches& Slobin 1973, Chierchia 1998, and T’suo1976, Borer 2005 and Her 2012a). They found that it is a universal property that classifiers and plurals are in complementary distribution. Borer (2005) and Her (2012a) further proposed that classifiers and plurals are the same category. However,. 政 治 大. classifiers and plurals can co-occur at least in 22 languages, according to a surveye by. 立. Gil (2008) and Haspelmath (2008). The aim of this study is to find out the relationship. ‧ 國. 學. between classifiers and plurals in these 22 languages. After the analysis of data, the. ‧. results show that classifiers and plurals are in complementary distribution in their. y. Nat. er. io. sit. usage, but not in cases of co-occurrence. The possible reasons for the co-occurrence may be language contact or language change. Thus, to account for the co-occurrence. al. n. iv n C h e n ofg cclassifiers in the 22 languages, syntactic structure h i U and plurals may be co-head structure. Most languages tend to have either classifier system or plural system. because they are the same category. But the co-occurrences are also reasonable since they are co-head.. Key Words: Numeral Classifiers, Plurals, Typological Property. ix.

(10) Chapter 1. Introduction There are numerous types of classifiers and number marking in languages. Classifiers include noun classifiers, verbal classifiers, numeral classifiers, locative classifiers etc. (Aikhenvald 2000). Number marking includes nominal number (as plural, dual and trial) and verbal number etc. (Corbett 2000). The focus of this study is the relationship between numeral classifiers and plural marking in noun phrases.. 政 治 大. If a numeral can be directly adjacent to a noun in a language, it is called a. 立. non-classifier language. If there is a classifier between a numeral and a noun, it is a. ‧ 國. 學. classifier language. The main function of classifiers is classification or. ‧. individualization. Chinese is considered to be the most prototypical classifier. y. Nat. er. io. sit. language among the numerous classifier languages and it contains the largest amount of classifiers (T’sou 1976). However, the exact number of classifiers in every. n. al. classifier language is still. iv n C U h edue uncertain h i controversy n gtoc the. in the definition of. classifiers. Therefore, a definition of classifiers will also be provided in this paper. As for plural marking, some languages denote plurals in various aspects as in nouns, pronouns, verbs, demonstrative etc., but plural marking is not always obligatory. Chierchia (1998) declared that if nouns in languages are transnumerals or mass, there will be no plural marking in such languages. Although classifiers and plurals seem to be unrelated, they share the same. 1.

(11) function of indicating the presence of countable units or individualizing nouns as a unit (Doetjes 1997). In addition to such similar function, Peyraube (1998) also found that the development of classifiers might be due to the decline of the plural markers. In his study of archaic Chinese, he found that the loss of plural markers forms a foundation stone of the prosperity of count-classifiers. Several linguists studying in the area of universal grammar or linguistic typology. 政 治 大. have observed that classifiers and plurals rarely co-occur. Greenberg (1972) claimed. 立. that “Numeral classifier languages generally do not have compulsory expression of. ‧ 國. 學. nominal plurality, but at most facultative expression.” (Greenberg 1972: 17).. ‧. Sanches and Slobin (1973) found that if a language has classifiers, there is no need for. y. Nat. er. io. sit. obligatory plural markers on nouns. Chierchia (1998) suggested that the argument type of languages which contain classifiers will lack plural markers along with. al. n. iv n C U of nominal classifiers and the h e n gthat (in)definite markers. T’sou (1976) proposed c hthei use. use of plural morphemes are in complementary distribution in natural languages. In addition to the suggestion that classifiers and plurals are in complementary distribution, Borer (2005) further declared that numeral classifiers and plurals also occupy the same syntactic position, being the same category. Since the topic of the relationship between classifiers and plurals has been investigated by so many linguists, we abbreviate their contribution as the general CPCD principle which represents that. 2.

(12) classifiers and plurals are seen as being in complementary distribution, and the strict CPCD principle which represents that classifiers and plurals are seen as being of the same category and thus unable to co-occur in a noun phrase (Borer 2005). Although the CPCD principle is applicable to most languages in the world, there are exceptions. In Nootka, both classifiers and plurals are obligatory (Sanches and Slobin 1973). In Korean, classifiers and plurals can simultaneously occur in a noun. 政 治 大. phrase (Kim 2005). Therefore, Fassi Fehri (2007) suggested that classifiers and. 立. plurals are different categories. Since the roles of classifiers and plurals are still. ‧ 國. 學. controversial, this paper will try to clarify the roles based on 22 languages which. ‧. contain both classifiers and plurals from the World Atlas of Language Structure. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Online.. 1.1 Motivation and Purpose. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The results of research by numerous linguists are presented in the World Atlas of Language Structure Online, with such results being re-organized by features used in the categorization of languages. Among the features, two of them are related to our topic: numeral classifiers and the occurrence of nominal plurality. Numeral classifiers in 400 languages were examined by Gil (2008) and the occurrence of nominal plurality in 291 languages was investigated by Haspelmath (2008). One hundred and. 3.

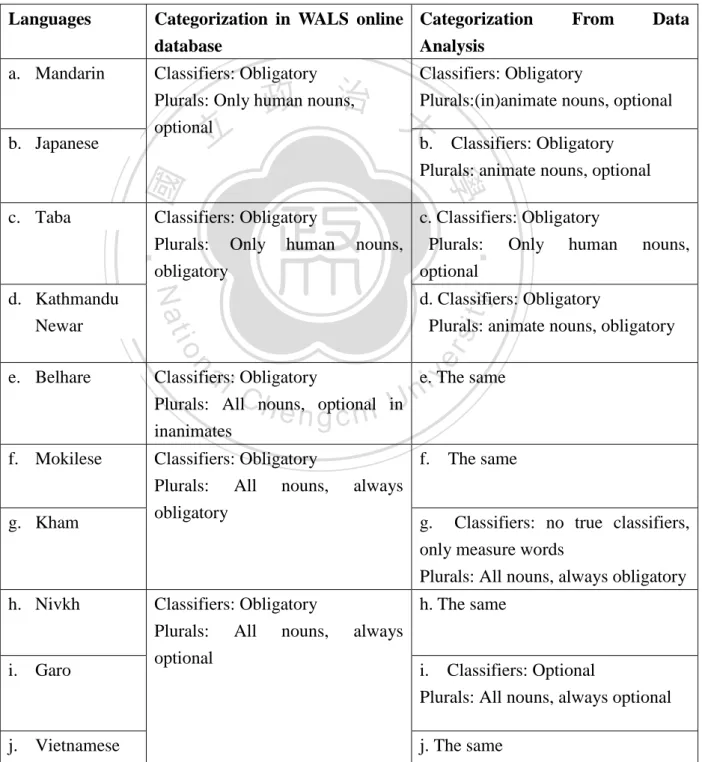

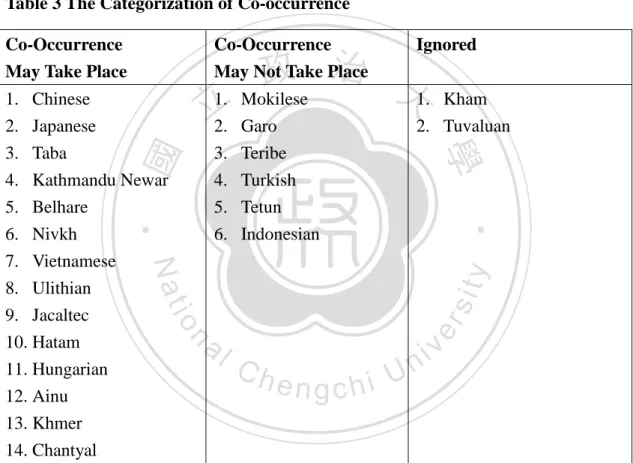

(13) fourteen languages were covered by both linguists. The clear classification of the absent/present of classifiers and plurals in 114 languages is as following.. Table 1. Numeral Classifiers and Nominal Plurality Nominal Plurality Numeral Classifiers. Absent. Present. Absent. 8. 80. Present. 4. 22. 84 languages following the CPCD principle are in complementary distribution in the. 政 治 大. existence of classifiers and plurals; 8 languages1 lack classifiers and plurals; and most. 立. ‧ 國. 學. important of all, 22 languages containing both classifiers and plurals violate the CPCD principle. When closely examining the 22 exceptions, we found that the degree. ‧ sit. y. Nat. of the violation is different.. n. al. er. io. Among the 22 languages, classifiers and plurals are obligatory in only 4. Ch. i Un. v. languages: Taba, Kathmandu Newar, Kham, and Mokilese. Furthermore, there are. engchi. only 2 languages: Kham and Mokilese, whose classifiers are obligatory and plural marking is also obligatorily applied to all nouns; that means they strongly violate the general CPCD principle. A detailed classification of the 22 languages is shown as in Table 2.. 1. 8 languages in WALS are lacking of classifiers and plurals. However, the other possibility is that the 8 languages might be containing both classifiers and plurals which are transparent. 4.

(14) Table 2. Numeral Classifiers and Nominal Plurality in 22 Languages. Occurrence of Nominal Plurality Human nouns only, optional. Hatam (1). Optional. Numeral Classifiers. Obligatory. All nouns, Human All nouns, All nouns, optional nouns only, always always in obligatory optional obligatory inanimates. (0). Ainu Indonesian Khmer (0) Tetun Chantyal (5). Garo 政 治 大 Jacaltec Taba Mandarin Nivkh 立 Kathmandu Japanese Teribe. Kham Mokilese (2). ‧. ‧ 國. Ulithian Vietnames (6). 學. Newar (2). (2). Belhare (1). Hungarian Turkish Tuvaluan (3). sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. If the principle proposed by previous linguists are correct, the 22 languages are. i Un. v. exceptions. However, the principle is an assumption based on observations and. Ch. engchi. inferences. It is reasonable that there are exceptions. But whether the principle is correct or not will be based on the degree of the violation of the exceptions. If the violation is not strong, the principle is still correct. Therefore, the aim of this study is to find out the correctness of the CPCD principle, and the nature of the exact relationship between the classifiers and plurals in the 22 languages. In the research of Gil (2008) and Haspelmath (2008), we found that they may have made their conclusions on the roles of classifiers and plurals in a 5.

(15) language based on a sentence or a chart of a book. In this paper, we will provide real sentences to support our analysis. Before our analysis in the 22 languages, we will clearly define classifiers and plurals in those languages, so as to establish that they have both classifiers and plurals. To define what classifiers are, we will adopt Greenberg (1974) and Her (2012a)’s criteria to identify true classifiers. As for true plurals, we will first distinguish additive. 政 治 大. plurals which are plural reading and associative plurals which express collective. 立. meaning, and the collective plurals will be excluded. In the process of defining. ‧ 國. 學. classifiers and plurals, we can also check the accuracy of the classification provided. ‧. by WALS online database.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Among the languages which actually contain classifiers and plurals, we will rank the complexity of the two systems in languages according to the range of application. al. n. iv n C U have Amongh the e nlanguages g c h i which. of classifiers and plurals.. true classifiers, the. classifiers will be ranked based on the criteria of Adam Conklin (1973), and true plurals will be ranked based on the criteria proposed by Corbett (2000). Different rankings of classifiers and plurals will be shown on an X axis and a Y axis, respectively. Classifiers will be scaled along an X axis; plurals will be scaled along a Y axis. And the hierarchy of the ranking will be introduced in Chapter 3. Thirdly, we move on to find whether the two elements can co-occur in a single. 6.

(16) noun phrase, since Borer (2005) stated that it is possible for classifiers and plurals to co-occur in a language but not in a noun phrase. From the findings, we will try to find the syntactic structure of the languages. And finally, we try to conclude whether classifiers and plurals in the 22 languages support the CPCD principle or whether the principle needs to be revised.. 1.2 Organization of the Thesis. 立. 政 治 大. In this paper, the different claims about the relationship of classifiers and plurals. ‧ 國. 學. will be presented in Chapter 2. Section 2.1 reviews several studies which have. ‧. observed that classifiers are in complementary distribution with plurals. In Section 2.2,. y. Nat. io. sit. Borer’s (2005) assertion that classifiers and plurals are the same category, and Her’s. er. (2012a) presentation of some evidence to support Borer’s claim are presented. In. al. n. iv n C h eclassifiers Section 2.3, the relationship between n g c h iandUplurals in languages has been. studied in depth by a number of linguists is described. Examples from Chinese are provided in Section 2.3.1 and from Japanese are in Section 2.3.2. Before examining the data in the 22 languages, the definition of classifiers and plurals will be presented in Section 3.1 and 3.2. In Chapter 4, the analysis of data will be presented in Section 4.1; a short summary for data analysis in Section 4.2; the analysis of syntax in Section 4.3; and. 7.

(17) possible explanation in Section 4.4. And the analysis of data will be divided into four parts. The two major languages, Chinese and Japanese, are analyzed in Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.1.2, respectively. In Section 4.1.3, we examine obligatory classifier languages, including Taba, Kathmandu Newar, Belhare, Mokilese, Kham, Nivkh, Garo, Vietnamese, Ulithian, Jacaltec and Teribe. In Section 4.1.4 we examine optional classifier languages, including Hatam, Tuvaluan, Hungarian, Turkish, Ainu, Khmer,. 政 治 大. Indonesian, Tetun and Chantyal. All of the examination of the classifiers and plural. 立. marking is based on the standard presented in Chapter 3.. ‧ 國. 學. Lastly, a conclusion along with some limitations of this study and suggestions for. ‧. further research will be presented in Chapter 5.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 8. i Un. v.

(18) Chapter 2. Literature review World’s languages can be divided into two groups, classifier languages and non-classifier languages, based on the appearance or non-appearance of classifiers. Among the classifier languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, etc., linguists have found that there is a typological property for classifier languages to lack obligatory plural marking. Therefore, they proposed that classifiers and plurals are in. 政 治 大. complementary distribution. Even if a language has both classifiers and plurals, there. 立. is a tendency for one of them to be obligatory and the other to be optional. Further,. ‧ 國. 學. classifiers and plurals hardly co-occur in a language. If they do, the characteristics of. ‧. the classifiers and plurals may change (Seiler 1986). To interpret the phenomenon of. y. Nat. er. al. n. (1). io. to the same category.. sit. complementary distribution, Borer (2005) suggested that classifiers and plurals belong. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. (Marie-Thérèse Vinet and Xiaoyan Liu 2008 p.361). This chapter will briefly introduce the work of certain linguists who have observed the complementary distribution phenomenon in Section 2.1. In section 2.2,. 9.

(19) the statements of Borer (2005) and Her (2012a) show that classifiers and plurals belong to the same category. In section 2.3, the work of various linguists who have constructed different points of view on the issue of classifiers and plurals in some languages is discussed. Chinese and Japanese are discussed in section 2.3.1 and 2.3.2, respectively.. 政 治 大. 2.1 Classifiers and Plurals: Complementary Distribution. 立. 2.1.1 Greenberg (1972). ‧ 國. 學. Greenberg has devoted himself to finding the universal grammar. One of his. ‧. important findings is about classifiers. He tried to find the origin of classifiers and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. reached the conclusion that classifiers are derived from measure or non-unit construction. This is based on two reasons. One is that word order and syntactic. al. n. iv n C h e nandg cclassifier markers of measure word construction h i Uconstruction are quite similar. The other is that measure word construction is prevalent almost in every language. During the research, Greenberg (1972) also made a generalization which was previously proposed by Sanches (1971). “Numeral classifier languages generally do not have compulsory expression of nominal plurality, but at most facultative expression.” This generalization is based on the observation of languages rather than a theoretical investigation. Although their generalization is similar, the assertion about. 10.

(20) the number marking is quite different. Sanches (1971) indicated that the classified noun is singular; while Greenberg (1972) regarded it as a noun lacking number marking rather than being singular. In addition, Greenberg (1972) pointed out that there are exceptions with respect to this generalization, such as Arabic dialects, Russian, and Turkic. There are both classifier system and plural system in these languages. However, Greenberg (1972) suggested that the plurals in such languages. 政 治 大. are in fact collectives which are grammatically singular but semantically plural. Thus,. 立. he claimed that if there is an exception to the generalization, the number marking is to. ‧ 國. 學. distinguish singular/collective rather than singular/plural. Therefore, the definition of. ‧. plurals in classifier languages plays a dominant role when examining the CPCD. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. principle. The different issues of plurals will be introduced in Section 3.2.. C 2.1.2 Sanches and Slobin (1973) h. engchi. i Un. v. Similar to Greenberg, Sanches and Slobin (1973) observed that plural markers are not obligatory in classifier languages. They examined 70 languages and made a table to show the relationship between numeral classifiers and plural markers as shown in Appendix B. Among the languages, certain of our target languages, Indonesia, Chinese, Garo, Jacaltec, Japanese, Khmer, Kathmandu Newar, and Vietnamese are located at. 11.

(21) Quadrant 1 [+numeral classifier, -obligatory plural marking]. In addition, there are a few exceptions which appear in Quandrant 4 [+numeral classifier, +obligatory plural marking]. Although their declaration about classifiers and plurals has exceptions, the Sanches-Greenberg-Slobin generalization forms a foundation stone on which to base an investigation of the relationship between classifiers and plurals.. 2.1.3 Chierchia (1998). 立. 政 治 大. Chierchia proposed two kind of features [arg] and [pred] to denote different. ‧ 國. 學. kinds of nouns. And based on the features, languages can be classified into three types,. ‧. [+arg, -pred] as Chinese, [+arg, +pred] as English, and [-arg, +pred] as Italian. The. y. Nat. er. io. sit. first type of languages is the major concern in this paper. Nouns in argument type [+arg, -pred] languages can be directly used as bare forms and are often regarded as. al. n. iv n C h e nmass mass nouns. In Chierchia’s statement, are regarded as plurals, so it is hi U g cnouns reasonable for mass nouns to lack plural markers. For mass nouns which are. inherently plural, classifiers serve the function of counting. Following are several properties of this type of languages as proposed by Chierchia.. (2) a. b. c. d. e.. Every noun extension is mass. There is no plural marking. A numeral can combine with a noun only through a classifier. There is no definite or indefinite article. Nouns can occur bare in argument position. 12.

(22) According to the (2c) and (2b), the languages which are so-called classifier languages will lack plural markers. Therefore, this conclusion is quite in accordance with the Sanches-Greenberg-Slobin generalization.. 2.1.4 T’sou (1976) T’sou (1976) proposed a statement that is similar to Greenberg’s generalization as following:. 立. 政 治 大 nominal classifier system. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Moreover, the study of suggests an important hypothesis that the use of nominal classifiers and use of plural morpheme are in complementary distribution in a natural language. More concretely, it suggests that either a) if a natural language has either nominal classifiers or plural morpheme, or b) if a natural language has both kinds of morphemes, their use is in complementary distribution. (T’sou 1976: 1216). y. Nat. er. io. sit. Apart from this observation, he also supported his statement with evidence from child language acquisition. There is a similar process of development when children. al. n. iv n C U h e nalong acquire classifiers and irregular plurals, verbal conjunctions. In h i irregular g c with child language acquisition, children tend to learn the same things at the same stage, so this may be a supporting evidence for Borer to claim that classifiers and plurals are the same category.. 2.2 Classifiers and Plurals: The Same Category. 13.

(23) 2.2.1Borer (2005) Borer (2005) suggested two viewpoints with regard to world languages. One is that all nouns are mass nouns, but unmarked for count or mass. The other is that both count nouns and mass nouns are grammatically constructed, rather than lexically constructed. The two statements are important for his argument that classifiers and plurals belong to the same category. In addition, languages have ways to make mass. 政 治 大. nouns become countable, and classifiers and plurals function as counting triggers in. 立. 學. ‧ 國. classifier languages and non-classifier languages, respectively. He further developed a tree structure to support his claim to their similarity.. ‧. (3) a.. b.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. (Borer 2005: 95). i Un. v. (Borer 2005: 95). Classifiers are independent morphs as head of <div> and plurals are affixes containing the <div> feature, and both of them serve as dividers, and are thus of the same category. Although he claimed that classifiers and plurals are of the same category, he 14.

(24) observed that it is possible for classifiers and plurals to co-exist in a language, but that it is impossible for them to co-occur in the same clause.. (4) a. Yergu had hovanoc uni-m Two CL umbrella have-1SG ‘I have two umbrellas’ b. Yergu hovanoc-ner unim Two umbrella-PL have-1SG ‘I have two umbrellas’. 政 治 大 Two CL umbrella-PL have-1SG 立 ‘I have two umbrellas’ (Borer 2005: 95). c.*Yergu had hovanoc-ner uni-m. ‧ 國. 學. Thus, classifiers and plurals are in complementary distribution in a noun phrase.. ‧. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.2.2 Her (2012a). i Un. v. Her (2012a) claimed that the plural –s can be seen as a generic or general. Ch. engchi. classifier. To demonstrate the similarity of –s and classifiers, Her (2012a) made a comparison among Chinese, Japanese and English as following:. (5) a. Chinese: [Num 3 [C ge b. Japanese: [Num 3 [C -tsu c. English: [Num3 [C -s. [N cup]]]=>[Num 3 [C ge [N cup]]] [N cup]]]=>[Num 3-tsu [C [N cup]]] [N cup]]]=>[Num 3 [C cup-s [N cup]]] (Her 2012a: 1682). Plural –s used to be thought as number more than one. But in fact, it functions as classifiers which represent the concept of times one, such as (6). 15.

(25) (6) a. Plural: three books [3 book*1] b. Classifier: 三. 本. 書 [3 *1 書]. san ben shu three CL book ‘three books’. (Her 2012a: 1674). Although Her (2012a) agreed with Borer’s (2005) statement that classifiers and plurals are the same category, he proposed that it is possible for classifiers and plurals to co-occur in a noun phrase.. (7) a. Chinese:三 個 學生. 立. 政 治 大 們. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. san ge xuesheng-men 3 CL student PL ‘three students’. ‘three students’. sit. (Her 2012a:1684). n. er. io. al. y. Nat. b. Japanese: san-nin-no gakusei-tati 3 CL-NO student -TATI. i Un. v. The two examples are well-formed and widely used by native speakers, but they. Ch. engchi. violate the strict CPCD principle. So, are the examples exceptions? Or, is the CPCD principle incorrect? We will take a closer look at this issue in Section 4.1.. 2.3 Previous Studies on Specific Languages In this paper, there are 22 languages which deserve a detailed examination in the relationship between their classifiers and plurals. Some of the languages have been surveyed by several linguists, but they have not reached a consensus. This section 16.

(26) presents some viewpoints on Chinese in Section 2.2.1, and on Japanese in Section 2.2.2.. 2.3.1 Chinese In Chinese, –men is considered to be either a plural marker (Li and Thompson 1981, Li 1999, Huang 2009) or a collective marker (Lu Shuxiang1947, Chao1968, Norman1988, Iljic1994, Cheng and Sybesma1999). If –men is a collective marker. 政 治 大 rather than a plural marker, Chinese is not a counter example to Borer’s generalization. 立. ‧ 國. ‧. generalization.. 學. If –men is a plural marker, it is worthy finding out the degree to which it violates the. sit. y. Nat. Li (1999) suggested that plural markers and classifiers are different heads which. n. al. er. io. project NumP and ClP, respectively. She proposed that -men and -s in English both. Ch. i Un. v. generate under Number. Unlike -s as realized in nouns, the application of -men as. engchi. realized in determiners is more limited Therefore, san ge xuesheng men ‘three students’ is ungrammatical because the classifier ge blocks the head movement of the noun (N) xuesheng to D position. (8) a. 三個學生. b. *三個學生們. san ge xuesheng 3 CL student ‘three students’. san ge xuesheng-men 3 CL student PL ‘three students’. 17.

(27) (Li 1999: 87). (Li 1999: 87). 政 治 大. Huang (2009) further supported Li’s claim by the cases of pronouns and proper. 立. ‧ 國. 三. 個. 人. 特別. io. 小強們. al. 三. n. 對. Ch. 個. y. sit. ‘I am especially nice to them three’ b. 我. 好. ta-men san ge ren tebie hao he-PL 3 CL people especially good. Nat. wo dui I to. 他們. 人. engchi U. er. 對. ‧. (9) a. 我. 學. names which are generated in D.. iv ntebie 特別. 好. wo dui XiaoQiang -men san ge ren hao I to XiaoQiang -PL 3 CL people especially good ‘I am especially nice to XiaoQiang them three persons’ (Huang and Li 2009: 313). Because -men should attach to a pronoun and a proper name, -men must be realized in the D position. From Huang and Li’s (2009) perspective, Borer’s (2005) generalization is incorrect. Classifiers and plurals are in complementary distribution because of the head movement constraint rather than being the same category. 18.

(28) Unlike Huang and Li (2009), Her (2012a) indicated that san ge xuesheng men ‘three students’ is grammatical which is supported by real data from Google search engine. Thus, Chinese violates not only the strict CPCD principle, but also the statement of Huang and Li (2009).. 2.3.2 Japanese. 政 治 大. In Japanese, there are two kinds of word order in noun phrases with classifiers as. 立. 學. ‧ 國. following:. Nat. y. ‧. (10) a. gakusei san-nin -ga kita student 3-CL -NOM came ‘Three students came.’. Ch. sit. v. (Yasuo Ishii 2000: 2). n. al. kita came. er. io. b. san-nin gakusei -ga 3-CL student -NOM ‘Three students came.’. engchi. i Un. When the noun is pluralized by -tati, gakusei-tati san-nin -ga kita ‘Three students came’ is grammatical in Japanese. Ishii (2000) suggested that classifiers and number plurals are different heads. And the plural marker -tati in Japanese is a phrasal affix attaching to NP which reveals in DP spec via feature checking. In addition, the assertion of Ishii (2000) convinced another linguist, Kurafuji, who had once thought that the co-occurrrence of classifiers and plurals is unacceptable in Japanese. Although we are not sure about the relationship between classifiers and plurals, we do 19.

(29) know that classifiers and plurals can co-occur in a noun phrase in Japanese. Downing (1996) adopted Greenberg’s concept in which the singulative/collective system often exists in classifier languages and the singular/plural system in non-classifier languages. Furthermore, Downing (1996) suggested that the singulative/collective and singular/plural systems were combined in Japanese, so that -tati can refer to either a plural meaning in common nouns or a collective meaning. 政 治 大. with proper names. However, the different word order of the nominal construction. 立. will influence the acceptability when the nouns are attached by -tati, as following.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. (11) a. Taro-tati san-nin Taro-PL 3-CL ‘Taro and his friends’. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. b. *san-nin Taro tati 3-CL Taro-PL ‘Taro and his friends’ c. gakusei-tati san-nin student-PL 3-CL ‘three students’. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. d. san-nin gakusei-tati 3-CL student-PL ‘three students’. (Downing 1996 ). Taro tati means Taro and his friends which is a collective usage. And proper names must be realized in D, so ‘san-nin Taro tati’ is ungrammatical. gakusei-tati on the other hand is a plural reading and realized in N, so both gakusei-tati san-nin and 20.

(30) san-nin gakusei-tati are acceptable. Although –tati has both plural and collective usage, Downing (1996) proposed that this kind of mixed system is in fact not a stable one. So, Japanese might become a language with either a singulative/collective system or a singular/plural system in the future.. 2.4 Syntactic Analysis of Nominal Structure. 政 治 大. The four basic elements in nominal structure are demonstrative (D), numeral. 立. (Num), adjective (Adj), and noun (N). The order of these elements varies from. ‧ 國. 學. language to language. Greenberg (1963) proposed a universal generalization called. ‧. universal 20 to include the possible order of the four elements in the languages of the. er. io. sit. y. Nat. world.. (12) Greenberg’s Universal 20 When any or all of the items (demonstrative, numeral, and descriptive adjective) precede the noun, they are always found in that order. If they follow, the order is either the same or its exact opposite. (Her 2012b: 3). n. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. However, only 14 orders from the 24 possible orders exist in the languages of the world. Cinque (2005) provided an order D> Num> A> N which can produce the 14 orders and exclude the other 10 impossible orders through two ways of movement. One is that N can move from Spec to Spec. The other is that N moves along with the category which it moves to. 21.

(31) (13) a.. b.. (Her 2012b: 14). 政 治 大. 立. (Her 2012b: 15). ‧ 國. 學. This is a perfect analysis for the order of the four elements. However, in classifier languages, the universal order becomes D> Num> C/M > A> N, and the. ‧. generalization is no longer so efficient. Among the three elements: Num, C/M, and N,. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. there are 6 possible word orders.. Ch. (14) Six Possible Word Orders of [Num, C/M, N] a. [Num C/M N] b. [N Num C/M] c. [C/M Num N] d. [N C/M Num] e. [C/M N Num] f. [Num N C/M] (Her 2012b: 2). engchi. i Un. v. According to the basic order Num> C/M >N along with the movement as in (14a) and (14b), Cinque wrongly predicted [C/M Num N], [C/M N Num], and [Num N C/M]. The analysis becomes insufficient because of the inseparability of Num and C/M. To compensate for the insufficiency of Cinque’s prediction, Her (2012b). 22.

(32) proposed that [Num C/M] should be viewed as a constituent. In previous studies, Num and C/M, being two independent elements and differing in semantic function are described as two functional heads, but they are usually viewed as a single constituent. So Her (2012b) suggested that Num and C/M generate as two heads, and C/M will move to Num and merge as a single unit. (15). 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 (Her 2012b: 24). y. Nat. er. io. sit. With this additional concept, the order of nominal structure with classifiers is perfectly predicted. And this nominal structure will be added with the number phrase. n. al. i n C U h e4.2. (NbP) to incorporate plurals in Section ngchi. v. 2.5 Remark The relationship between classifiers and plurals has been a universal property. While each statement proposed by linguists has exceptions. Greenberg (1972) and Sanches and Slobin (1973) stated that plural marking is not obligatory in classifier languages. But some languages such as Yuki, Nootka, Tlingit, Ejagham etc. have both. 23.

(33) numeral classifiers and obligatory number marking. Sanches and Slobin (1973) also found this fact as shown in Appendix B. So the Sanches-Greenberg-Slobin generalization is not without exceptions. And Borer (2005) claimed that numeral classifiers and plural marking are the same category, and can not co-occur in a noun phrase. But they do co-occur in a noun phrase as in Chinese and Japanese.. (16) a. 三個學生們 san ge xuesheng-men 3-CL student-PL ‘Three students’. 立. ( Yasuo Ishii 2000: 12). Nat. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. b. gakusei-tati san-nin student-PL 3-CL ‘Three students’. 政 治 大 (Her 2012a: 1684). er. io. sit. So it is worthwhile to take a closer look at this issue. Are classifiers and plural marking the same category? If yes, how can we explain the co-occurrence? If not,. al. n. iv n C h e n gdistribution why is the phenomenon of complementary c h i Ua universal property?. In respect to the syntactic aspect of classifiers, Her (2012b) adopted the word order typology from Cinque (2005) and provided a new analysis to account for the nominal structures with classifiers. But Her (2012b) only focused on the analysis of classifiers and measure words, and did not take plural marking into consideration. So in a study of the relationship between classifiers and plurals, it is worthwhile to reanalyze the form of the tree.. 24.

(34) Chapter 3. Defining Classifiers and Plurals 3.1 Definition of classifiers There are numerous types of classifiers such as noun classifiers, verbal classifiers, numeral classifiers, locative classifiers etc. Among all of the types of classifiers, that of numeral classifiers is the most well-known type, and linguists often shorten it as classifiers. Traditionally speaking, classifiers can be divided into two kinds: classifiers. 政 治 大. and measure words (Lyons 1977). Classifiers which is also called sortal classifiers or. 立. count-classifiers denote a classification based on the kind of entity; measure words. ‧ 國. 學. which is also called mensural classifiers, massifiers, mass-classifiers individuate from. ‧. quantity. Following are some examples of both types:. sit. y. Nat. al. n. yi ben shu one C book ‘one book’. er. 書. io. (17) Classifiers a. 一 本. b. 一. 種. Ch. engchi. 樹. yi zhong shu one C tree ‘a kind of tree’ (18) Measure words a. 一 斤 魚 yi jin yu one M fish ‘one kilogram of fish’. 25. i Un. v.

(35) b. 一. 群. 狗. yi qun gou one M dog ‘a pack of dogs’. T’sou (1976) thought that there are still some differences between (17) and (18) . So he further provided two kinds of features to divide classifiers into four types: [+exact, -entity], [+exact, +entity], [-exact, +entity], and [-exact, -entity]. And only [+exact, +entity] classifiers are regarded as true classifiers in this study.. 立. (19) a. [+exact, -entity] 一 群 狗. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. yi qun gou one M dog ‘a pack of dogs’. sit. n. al. er. io. yi ben shu one C book ‘one book’. y. Nat. b. [+exact, +entity] 一 本 書. Ch. engchi. c. [-exact, +entity] 一 斤 魚 yi one. jin M. yu fish. ‘one kilogram of fish’ d. [-exact, -entity] 一 種 樹 yi zhong shu one C tree ‘a kind of tree’. 26. i Un. v.

(36) Since classifiers and measure words occupy the same linear position and both function as unit-counters, they were once thought of as being of the same status. However, they are distinct from each other. Her (2012a) provided two ways to differentiate classifiers and measure words. One is by the semantic distinction in which classifiers indicate the essential property of nouns; while measure words indicate the accidental property in terms of quantity.. 尾. ‧ 國. 魚. dun yu M fish. y. Nat. ‘300 tons of fish’. (Her 2012a). io. n. al. sit. sanbai 300. 噸. ‧. b. 三百. 立. yu fish. 政 治 大. 學. sanbai wei 300 C ‘300 fish’. 魚. er. (20) a. 三百. i Un. v. Wei referring to tail is an essential property of a fish; while dun denoting the amount. Ch. engchi. of fish is an accidental property. So classifiers and measure words are semantically different. The other is mathematical distinction. The value of classifiers is necessarily 1; and the value of measure words is not necessarily 1.. (21) a. 四. 個. si ge Four C ‘4 persons’. 人 ren person. 27.

(37) b. 四. 打. 玫瑰. si da meigui Four M rose ‘4 dozens of roses’. (Her 2012a: 1676). The number of people in si ge ren is four; while the number of rose in si da meigui is forty-eight (4*12). So the number of classifiers is one; while the number of measure words is not necessarily equal to one. From the aboved introduction, we know that classifiers and measure words are. 政 治 大. different from each other. So it is important to find the true classifiers. And in this. 立. ‧ 國. 學. paper, only sortal classifiers with [+exact, +entity] property are true classifiers. Hale and Shresthachrya (1973) summarized five characteristics of true classifiers from. ‧. Greenberg (1972).. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. (22) a. They are overt expressions of unit counting. b. They are used with reference to structured units which are normally counted as individuals. c. They impose a semantic classification upon the head noun. d. They function as individualizers of a head which is indeterminate for number. e. They have no reality outside of the numeral expression.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In this paper, we analyze the 22 languages based on Greenberg and Her’s criteria. After defining the true classifiers, we further rank the classifiers based on the range of application to distinguish the completion of classifier system in the 22 languages. We adopt the semantic hierarchy of classifiers provided by Adam and Conklin (1973). [±human], [±animates], and [shape] are important features in the 28.

(38) hierarchy. A higher ranked one will imply the existence of a lower ranked one. So when classifiers can denote the higher ranking, we assume the system in which such type of classifier is found is more complete. Apart from the hierarchy provided by Adam and Conklin (1973), we also find that obligatoriness of classifier is also crucial. A language with obligatory classifiers implies the completion of its classifier system. Also, measure words were included at. 政 治 大. the lowest ranking, because measure words may be the origin of classifiers. A. 立. language may only contain measure words before it generates its classifier system.. ‧ 國. 學. Therefore, classifiers will be ranked as following in this paper.. ‧. y. Nat. (23) The Ranking of Classifiers in This Paper Measure words < Optional classifiers (human) < Optional classifiers (animal) <. sit. n. al. er. io. Optional classifiers (inanimate) < Optional classifiers (shape) < Obligatory classifiers (human) < Obligatory classifiers (animal) < Obligatory classifiers (inanimate) < Obligatory classifiers (shape). Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3.2 Definition of Plurals The basic distinction between numbers is singular and plural, but some languages also includes dual, trial or paucal in their number marking system. And the focus of this paper is plural. There are several ways to express plurality. For example, we may add a plural marker to nouns, use different determiners, reduplicate the nouns, etc. When applying. 29.

(39) plural marking in languages, we often find that different nouns will differ in the tendency of using plurality. For example, -men in Mandarin which is sometimes considered as a plural marker can only attach to animate nouns such as haizimen ‘children’ or xiaogoumen ‘dogs’. But as qianbimen ‘coins’or shubenmen ‘books’, these inanimate nouns followed by -men are ungrammatical. The differences in the application can be distinguished based on Animacy Hierarchy presented by Corbett (2000) as following:. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. (24) Animacy Hierarchy 1st person pronoun > 2nd person pronoun > 3rd person pronoun > kin > human > animate > inanimate. Similar to the ranking of classifiers, obligatory and optional application is also. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. included in the ranking to judge the completion of the plural system. Further, to make. i Un. v. an economical ranking, personal pronouns are shortened into one scale as plural. Ch. engchi. personal pronoun. And kin is omitted, because kin is not a distinctive feature in the analysis of the 22 languages. Therefore, the ranking of plurals in this paper is as following:. (25) The Ranking of Plurals in This Paper Plural personal pronoun< optional human plurals < optional animate plurals < optional inanimate plurals < obligatory human plurals < obligatory animate plurals < obligatory inanimate plurals. 30.

(40) Apart from the plural distinction, we should note two elements which often occur in classifier languages, transnumeral nouns and collective markers. Both of them possess the property of plurality, so it is important to exclude the two elements, and correctly identify the true plurals. The two elements will be introduced in Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2.. 3.2.1 Transnumerals. 立. 政 治 大. Some languages have a singular-plural distinction, while there is no such. ‧ 國. 學. distinction in other languages, in which the number is transparent. Linguists may call. ‧. transparent number as “ general number”, “ general”, “a common number form”,. Nat. er. io. sit. y. “unit reference”, or “transnumeral”. In such languages, the number of bare nouns can be regarded as either one or more than more.. n. al. Ch. engchi. (26) Languages with singular-plural distinction English: a dog (sg.) dogs (pl.). i Un. v. (27) Languages with transnumerals a. Mandarin: 狗 gou ‘a dog(sg.) or dogs(pl.)’ b. Bayso: lúban ‘a lion(sg.) or lions(pl.)’. (Corbett 2005: 10). Although the number of transnumerals can not be identified in bare forms, it can 31.

(41) be expressed through other denotation rather than plural markers. Following are three ways to distinguish between the singular and plural of transnumeral nouns.. (28) Numeral denotation a .一 隻 狗 yi zhi gou 1 CL dog ‘a dog’ b. 兩. 隻. 狗. liang zhi gou 2 CL dog ‘two dogs’. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. (29) Classifier and measure word denotation a. 一 隻 狗. ‧ y. sit. 狗. al. n. yi qun gou 1 M dog ‘a pack of dogs’. er. 群. io. b. 一. gou dog. Nat. yi zhi 1 CL ‘a dog’. Ch. engchi. (30) Adjective denotation a. 一 些 狗 yi. xie gou. some dog ‘some dogs’ b. 很. 多. 狗. hen duo gou many dog ‘many dogs’. 32. i Un. v.

(42) Therefore, if the nouns in the 22 languages are considered to be transnumeral, they may lack plural markers even if they are semantically plural. So plural marking tends to be optional in such languages.. 3.2.2 Additive/ Associative Distinction Additives are general plurals which represent the number of the thing is more. 政 治 大. than one, such as the plural marker –s in English. Associatives on the other hand. 立. usually refers to a person along with one or more associated members as in the case of. ‧ 國. 學. collective marker -ek in Hungarian. Hungarian is a language containing both additives. ‧. and associatives. Following are examples.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. (31) Hungarian a. János ‘John’. Ch. engchi. b. János-ok John -PL ‘Johns’ (more than one person called John). i Un. v. c. János-ék John-ASSOC.PL ‘John and associates’, ‘John and his group’. (Corbett 2005: 102). In some languages, the distinction between additive plurals and associative plurals is not clear, so it is important to correctly identify true plurals and exclude collective markers. 33.

(43) In languages with both classifiers and plural marking, Greenberg (1972) suggested that they tend to make a distinction between singulative/collective rather than singular/plurality. Seiler(1986) also proposed that plurals in languages with a mixed system are not true “plural marker”. Therefore, in the 22 languages which have a mixed system, it should be noted as to whether the plural is a real plural or not.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 34. i Un. v.

(44) Chapter 4. Analysis The focus of this paper is to analyze the 22 languages which have been examined by Gil (2008) and Haspelmath (2008). Since they carried out research on numeral classifiers and plural marking, respectively, we try to analyze the relationship between the two and reach a consensus. The WALS online database provides a more detailed categorization of the 22 languages (Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, Taba,. 政 治 大. Kathmandu Newar, Belhare, Mokilese, Kham, Nivkh, Garo, Vietnamese, Ulithian,. 立. Jacaltec, Teribe, Hatam, Tuvaluan, Hungarian, Turkish, Ainu, Khmer, Indonesian,. ‧ 國. 學. Tetun, and Chantyal) as in Appendix A. The data in each language will be analyzed in. ‧. Section 4.1. And since I am a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese and a foreign. y. Nat. er. io. sit. language learner of Japanese, Mandarin Chinese and Japanese will be closely examined in Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.1.2, respectively. And other languages will be. al. n. iv n C U h e nobligatory divided into two parts: those containing (according to Gil 2008) g c h i classifiers. in Section 4.1.3 and optional classifiers (according to Gil 2008) in Section 4.1.4. Most of the languages in Section 4.1.3 and 4.1.4 are less-studied languages. It is very likely that there are only one or two linguists who have ever examined these languages, so the data is scarce and limited. To compensate for the scarcity of data, we will adopt the categorization from WALS online database or use assumptions. All of the analysis will be based on the definition in Chapter 3. And a short summary for the data. 35.

(45) analysis will be displayed in Section 4.2. In Section 4.3, a syntactic analysis will be proposed to explain the typological property of classifiers and plurals in the majority of languages as well as some exceptions with co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals. In Section 4.4, some possible explanations for our findings are presented.. 4.1 Data Analysis in Languages In this paper, 22 languages are investigated. Mandarin Chinese and Japanese will. 政 治 大 be closely examined in Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.1.2, respectively. In section 4.1.3, 立. ‧ 國. 學. languages in which classifiers are obligatory according to Gil (2008) (Taba,. ‧. Kathmandu Newar, Belhare, Mokilese, Kham, Nivkh, Garo, Vietnamese, Ulithian,. sit. y. Nat. Jacaltec, and Teribe) will be examined. In section 4.1.4, languages in which classifiers. n. al. er. io. are optional according to Gil (2008) (Hatam, Tuvaluan, Hungarian, Turkish, Ainu,. Ch. i Un. v. Khmer, Indonesian, Tetun, and Chantyal) will be analyzed. Most of the data are. engchi. secondary sources collected from previous studies.. 4.1.1 Mandarin Chinese Chinese is considered to be a prototypical classifier language, and its classifiers are obligatory, including general classifiers, human classifiers, animal classifiers, inanimate classifiers and shape classifiers.. 36.

(46) (32) Obligatory classifiers a. 我 需要 三. 位. 學生. 來. 幫忙. wo xuyao san wei xuesheng lai bangmang I need three CL students come help ‘I need three students to help me.’ b. *我. 需要. 三. 學生. 來. 幫忙. wo xuyao san xuesheng lai bangmang I need three students come help ‘I need three students to help me.’ (33) Range of application of classifiers a. Measure word: jin 一 斤 肉. 立. ‧ 國. 學. yi jin rou one CL meat ‘one kilogram of meat’. 政 治 大. ge ren. y. Nat. yi. ‧. b. General classifier: ge 一 個 人. sit. n. al. er. io. one CL person ‘one person’. c. Human classifier: wei 三 位 老師. Ch. engchi. san wei laoshi three CL teacher ‘three teachers’ d. Animal classifier: pi 三 匹 馬 san pi ma three CL horse ‘three horses’. 37. i Un. v.

(47) e. Shape classifier: ke 一 顆 蘋果 yi ke pingguo one CL apple ‘an apple’. Since classifier system in Chinese is quite complete, it is worth examining the range of the application of the plural marker -men. Some linguists considered it as collectives (Lu Shuxiang 1947, Chao 1968, Norman 1988, Iljic 1994, Cheng and. 政 治 大. Sybesma 1999) rather than plurals (Li and Thompson 1981, Li 1999, Huang 2005,. 立. Her 2012a). In this paper, we find that -men is a plural.. ‧ 國. 學. Some linguists propose that Zhang San men ‘many Zhang San or Zhang San and. ‧. his friends’ have a plural reading with the meaning that there are many people whose. y. Nat. er. io. sit. name is Zhang San and a collective reading with the meaning of Zhang San and his friends. But Zhang San men with a collective reading is seldom used. Most native. al. n. iv n C h eusage speakers even regard the collective It is more likely that hi U n gasc ungrammatical.. Zhang San ta men will be used to obtain the collective meaning of Zhang San and his friends. In the other case, if there are a man who is tall, and three men who are short, we can not use gao ge zi men ‘tall people’ to denote the four people. But if –men is a collective, gao ge zi men should be applicable in this situation. So –men is not a collective marker.. 38.

(48) Another piece of evidence is proposed by Huang (2005). -men can be followed by a distributive marker dou ‘all’, such as, tamen dou jie hun le ‘They are all married.’ With the use of distributive marker dou, the meaning is that each of the two people is married to another people. However, if –men is a collective marker, the sentence means that the two people are married to each other. While there is no such interpretation for this sentence. Thus -men can not be a collective but a plural marker.. 政 治 大. Although –men is a plural marker, its properties as following are different from the. 立. plural marker -s in English.. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. (34) a. -men applies only on pronoun, proper name, human or animated common nouns. b. -men is not used with numerals. c. -men is not obligatory.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. In this paper, we suggest that the first and second properties should be revised.. al. n. iv n C h e can Among the younger generation, -men affixed i U not only to pronouns, proper n gbec h names, human or animated common nouns, but also to inanimate common nouns.. (35) a. 去 把. 桌子們. 擦 一 擦. qu ba zhuozimen ca yi ca go table-PL wipe ‘Wipe the tables’ b. 把 插頭們. 拔 掉. ba chatoumen ba diao plug PL pull ‘Pull out the plugs.’ 39.

(49) In addition, when -men is affixed to inanimate nouns, the usage of -men is more like a plural marker rather than a collective. On the second point, -men can co-occur with numerals along with classifiers as in (36).. (36) a. 三 個 老師們. 昨天. 去. San ge laoshimen zuotian qu. 開會 kaihui. three CL teacher PL yesterday go meeting ‘Three teachers had a meeting yesterday.’ b. 那 五 個 學生們. 立. 政 治 大 的 作業 交 了 沒?. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Na wu ge xueshengmen de zuoye jiao le mei? That five CL student PL homework hand in? ‘Did the five students hand in their homework?’. Thus, we can find that the application of -men is more prevalent than as noted in. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. previous studies.. i Un. v. We can sum up that in Chinese, classifiers are stronger than plurals in previous. Ch. engchi. studies. But we find that plurals have become stronger in recent years, with the extension of range of application to include inanimate nouns.. 4.1.2 Japanese Classifiers in Japanese are obligatory and include measure words, general classifiers, human classifiers, animate classifiers, inanimate classifiers and shape classifiers. 40.

(50) (37) Obligatory Classifier hon ni *(satu) Book two CLF ‘two books’ (Nomoto 2010: 2) (38) Range of application of classifiers a. Measure word: hako keiki hito-bako cake one CL ‘a box of cake’ b. General classifier: tsu ringo hito-tsu apple one CL ‘an apple’. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. c. Human classifier: nin sensei san nin teacher three CL ‘three teachers’. n. er. io. al. sit. y. Nat. d. Animal classifier: hiki kuma ni-hiki horse two CL ‘two horses’. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. e. Shape classifier: satsu hon ichi-satsu book one CL ‘a book’ (Dowing 1996: 55). As for number marking, nouns in Japanese are transnumerals, so number marking is not obligatory. There is more than one plural marker in Japanese, such as -tati, -ra, -domo, and -gata. -ra, -domo, and -gata are only used to denote plural pronouns, but -tati can be widely used in human and animate common nouns. 41.

(51) (39) Range of application of plurals a. Human gakusei-tati student-PL ‘the students’ b. Animate inu-tati dog-PL ‘the dogs’ c. * Inanimate kuruma-tati Car-PL. 政 治 大 立(Ishii 2000: 1). ‘the cars’. ‧ 國. 學. Some linguists have treated -tati as a plural while others have considered it as a. ‧. collective. -tati can be either a plural or a collective when attached to different kinds. y. Nat. er. io. sit. of nouns. If the noun is a common noun, -tati represents a plural. If the noun is a proper name,-tati is a collective.. n. al. (40) a. Plural: Kodomo tati child PL ‘Children’. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. b. Collective: Taro tati Taro ASSOC-PL ‘Taro and his friends’ (Ishii 2000: 2). As for the co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals, it is grammatical in Japanese as in (41). 42.

(52) (41) gakusei-tati san-nin student-PL 3-CL ‘three students’. (Ishii 2000: 12). Thus the system of Japanese is quite similar to Chinese. The classifier system is more dominant than the plural system.. 4.1.3 Obligatory classifier languages In this section, we investigate the languages whose classifiers are obligatory. 政 治 大 according to Gil (2008), including Taba, Kathmandu Newar, Belhare, Mokilese, 立. ‧ 國. 學. Kham, Nivkh, Garo, Vietnamese, Ulithian, Jacaltec and Teribe. The real classification. ‧. in such languages is not necessarily obligatory classifier languages. The role of. n. al. 4.1.3.1 Taba. y. er. io. sit. Nat. classifiers in each language will be based on collected data.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Classifiers are obligatory (without supporting examples) in Taba, and include measure words, general classifiers, human classifiers, animal classifiers, inanimate classifiers and shape classifiers.. (42) Range of application of classifiers a. Measure word: haLiter halu liter ha=lu litre CLASS=two ‘two liters’. (Bowden 2001: 253) 43.

(53) b. General classifier: pamplop pwonam amplop p=wonam envelop CLASS=six ‘six envelopes [of A4 size]’. (Bowden 2001: 243). c. Human classifier: i-1/mat-2-9/yo-10 Wang gulo iso Wang gulo i=so Child baby CLASS=one ‘one baby’ (Bowden 2001: 256) d. Animal classifier: i-1/ sis-2-9/beit-10 yan iso. 立. (Bowden 2001: 257). ‧ 國. 學. yan i=so fish CLASS=one ‘one fish’. 政 治 大. ‧. e. Shape classifier: motamplop motwonam amplop mot=wonam. y. Nat. sit. (Bowden 2001: 242). er. io. envelop CLASS=six ‘six normal sized envelopes’. al. n. iv n C U classifiers h e n g c hini which special phenomenon. In Taba, there is a. will vary with. numbers. For example, the classifier for animal has three forms, i, sis, and beit. i is used for 1; sis for 2 to 9; and beit for 10.. (43) a. yan iso yan i=so fish CLASS=one ‘one fish’. (Bowden 2001: 257). 44.

(54) b. kabin. sithol. kabin sis=tol goat CLASS=three ‘three goats’. (Bowden 2001: 257). A plural marker -si in Taba is optional as in (44b) and it only applies to human nouns.. (44) a. With a plural marker: mapinci mattol mapin=si mat=tol woman=PL CLASS=three ‘three women’. 立. 政 治 大 (Bowden 2001: 256). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. b. Without a plural marker: mapin mattol mapin mat=tol woman CLASS=three ‘three women’. er. io. sit. y. Nat. (Bowden 2001: 256). The co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals, it is grammatical in Taba as in (45).. n. al. (45) mapinci mattol mapin=si mat=tol woman=PL CLASS=three ‘three women’. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. (Bowden 2001: 256). Therefore, Taba violates the strict CPCD principle in which classifiers and plurals shouldn’t co-occur. But we can find that they are still in complementary distribution in certain degree because classifier system is stronger than plural system.. 45.

(55) 4.1.3.2 Kathmandu Newar The classifier system of Kathmandu Newar is quite similar to Taba’s. Its system is obligatory (without supporting examples) and include measure words, animate (human and animal) classifiers, inanimate classifiers and shape classifiers.. (46) Range of application of classifiers a. Measure word jākhi cha-khwalā rice one M ‘a cupful of rice’ (Weidert 1984: 208). 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. b. Human classifier:-mha macā cha-mha child one CL ’one child’ (Weidert 1984: 188). sit. al. n. (Weidert1984: 188). Ch. engchi. d. Inanimate classifier: -kha che cha-kha house one CL ‘one house’ (Weidert 1984: 189). er. io. khicā cha-mha dog one CL ‘one dog’. y. Nat. c. Animal classifier:-mha. i Un. v. e. Shape classifier: -ga ālu cha-gaa potato one CL ‘one potato’ (Weidert1984: 189). There are two ways to express plural marking in Kathmandu Newar. One is plural marker; the other is reduplication. Plural markers, -tͻ and -pῖ, obligatorily 46.

(56) applies to animate common nouns, as in (47). And the reduplication form to express plurality is as in (48).. (47) Range of application of plural marker a. Human pasa-pῖ ‘friends’ b. Animal khica-tͻ ‘dogs’. (Hargreaves 2003: 373). 立. b. khica-khaca ‘dogs’. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. (48) Reduplication a. khica2 ‘dogs’. 政 治 大. (Hargreaves2003: 378). sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. The co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals is grammatical in Kathmandu Newar, as in (49).. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. (49) chə-gu: deś-ɛ: nya-mhə pasa-pῖ: du one-CLF country-LOC five-CLF friend-PL exist.ID ‘In a certain country there were five friends.’ (Hale and Shrestha 2006: 93). Therefore, Kathmandu Newar violates the strict CPCD principle. Also, classifier system is stronger than plural system in Kathmandu Newar.. 2. The majority data are secondary sources collected from previous studies. Examples are cited based on the original forms from authors, so the spelling may differ from person to person. For example, ‘dog’ in Kathmandu Newar were spelt as khica by Hargreaves (2003); while khicā by Weidert(1984). But, they are the same word. 47.

(57) 4.1.3.3 Belhare Classifiers in Belhare are obligatory. Only two kinds of classifiers are indigenous: human classifier -pa and non-human classifier -kira. Except for -pa and -kira, other kinds of more specific classifiers are borrowed from Nepali. (Bickel 2003).. (50) Range of application of classifiers a. Human classifier: -pa sip- -pa. mai-chi. two-HUM person-nsg[ABS] ‘Two people’. 立. 治 2003: 563) 政 (Bickel 大. ‧ 國. phu. tar-he-. 學. b. Non-human classifier: -kira sik-kira phabele=ma. ‧. Two NHUM red=COLOUR. ART flower[ABS] bring-PAST[-3P]-1sgA ‘I brought two red flowers. (Bickel 2003: 562). y. Nat. er. io. sit. A plural marker -chi is optional and rarely used in inanimate common nouns. Since plural markers are optional, only few examples with plural markers were found.. al. n. iv n C h e n g cofhplurals We can only judge the range of application i U based on the description of author (Bickel 2003). Classifiers and plurals in Belhare must co-occur, as in (51). If there are no plurals as in (51b), it will be ungrammatical. (51) a. sip- -pa two-HUM ‘two people’ b. *sip- -pa. mai-chi person-nsg[ABS] (Bickel 2003: 563) mai. two- HUM person [sgABS]. (Bickel 2003: 563) 48.

(58) 4.1.3.4 Mokilese Classifiers in Mokilese are obligatory. But there are only four numeral classifiers: -w, -men, -pas, and -kij. -w is a general classifier; -men is an animate classifier; -pas is a long object classifier; -kij denotes things which have pieces or parts.. (52) Range of application of classifiers a. Measure word: -kij adroau riahkij egg two-CL ‘two pieces of eggs’. 政 治 大. (Harrison 1976: 97). 立. (Harrison 1976: 96). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. b. General classifier:-w wus riaw banana two-CL ‘two bananas’. sit (Harrison 1976: 95). n. al. d. Shape classifier:-pas amper dohpas umbrellas nine-CL ’nine umbrellas’. Ch. engchi. er. io. jeri roahmen child two-CL ’two children’. y. Nat. c. Animate classifier:-men. i Un. v. (Harrison 1976: 96). Based on Her (2012a), the number of classifier should be equal to ‘1’. However, -kij denotes the number less than one (Harrison 1976). Thus, -kij should be a measure word rather than a real classifier.. 49.

(59) (53) a. adroau riahkij egg two-M ‘two pieces of eggs’ b. adroau riaw egg two-CL ‘two eggs’. (Harrison 1976: 97). (Harrison 1976: 97). In Mokilese, personal pronoun has four ways of distinction, singular, dual, plural, remote plural. And in common nouns, determiner -pwi serves as the function of distinguishing singular and plural.. 立. 政 治 大 (Harrison 1976). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. (54) Ngoah kapang woalpwi o I see man-D there ‘I saw some men there.’. An interesting phenomenon in Mokilese is that both classifier system and plural. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. system are strong. Both system are obligatory and applying to the highest ranking.. i Un. v. Thus, Mokilese violates the general CPCD principle, and represents no. Ch. engchi. complementary distribution in its usage. Therefore, it deserves a closer look in further research. The co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals is ungrammatical in Mokilese. Doetjes (to appear) suggested that if a sentence contains a numeral which fused with a classifier, the co-occurrence of the plurality determiner -pwi will be prohibited.. 50.

(60) 4.1.3.5 Kham Based on Watter (2002), there are only measure words in Kham. Because we can’t find the true classifier from the same reference of Gil (2008) provided by WALS online database, we assume that there are no true classifiers but only measure words in Kham.. (55) a. t-kri: sya: ‘a chunk of meat’ b. to-cop mnm ‘a pinch of flour’. (Watter 2002: 54). 立. 政 治 大. (Watter 2002: 54). ‧ 國. 學. A plural marker -r can obligatorily apply to all nouns and include human,. ‧. animate, and inanimate common nouns.. n. Ch. engchi. b. Animal Ka:h-ni Dog-DL ‘(two) dogs’. (Watter 2002: 54). c. Inanimate lu:-r Stone-PL ‘(three or more) stones’ (Watter 2002: 54). 51. er. io. al. sit. y. Nat. (56) Range of application of plurals a. Human luhza Child:SG ‘a child’ (Watter 2002: 54). i Un. v.

(61) As for the co-occurrence of classifiers and plurals, there are no classifiers but measure words in Kham based on Watter (2002). So there is no need to concern the issue.. 4.1.3.6 Nivkh Classifiers are obligatory (according to WALS online database) in Nivkh, and. 政 治 大. include measure words, general classifiers, human classifiers, animal classifiers,. 立. inanimate classifiers, and shape classifiers. (Mattissen. 2003). ‧ 國. 學 ‧. (57) Range of application of classifiers a. General classifiers: ñaqr ‘1’; meqr ‘2’; ̢taqr ‘3’. n. al. Ch. sit er. io. c. Animal classifier: ñəñ ‘1’; mor ‘2’; ̢tor ‘3’. y. Nat. b. Human classifier: ñin ‘1’; men ‘2’; ̢taqr ‘3’. i Un. v. d. Inanimate classifier (for boats): ñim ‘1’; mim ‘2’; ̢tem ‘3’. engchi. e. Shape classifier (for long shape): ñex ‘1’; mex ‘2’; ̢tex ‘3’ (Mattissen p.c., Panfilov 1962: 181-183, Krejnovič 1934: 202-203). Plurals being optional in Nivkh can be denoted in two ways. One is plural marker; the other is reduplication. There are four forms of plural markers: ku, gu, γu, and xu, and they can apply to all common nouns.. 52.

數據

+2

相關文件

從思維的基本成分方面對數學思維進行分類, 有數學形象思維; 數學邏輯思維; 數學直覺 思維三大類。 在認識數學規律、 解決數學問題的過程中,

畫分語言範疇(language categories),分析學者由於對語言的研究,發現

千」的法界觀。智者大師依《法華經》十如是,《華嚴經》十法界,《智 論》三世間,立如來法身實相之境的「一念三千」。《智論》說法界有三 類世間 :

Cauchy 積分理論是複變函數論中三個主要組成部分之一, 有了 Cauchy 積分理論, 複變 函 數論才形成一門獨立的學科, 並且導出一系列在微積分中得不到的結果。 我們先從 Cauchy

請聽到鈴(鐘)聲響後再翻頁作答.. Chomsky)將人類語言分成兩種層次,一是人類普遍存在的潛 力,一是在環境中學習的語言能力。他認為幼兒有語言獲得機制( Language Acquisition Device 簡稱

For pedagogical purposes, let us start consideration from a simple one-dimensional (1D) system, where electrons are confined to a chain parallel to the x axis. As it is well known

二、 學 與教: 第二語言學習理論、學習難點及學與教策略 三、 教材:. 運用第二語言學習架構的教學單元系列

Rebecca Oxford (1990) 將語言學習策略分為兩大類:直接性 學習策略 (directed language learning strategies) 及間接性學 習策略 (in-directed