WHY MANAGERS FAIL TO DO THE RIGHT THING: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF UNETHICAL & ILLEGAL CONDUCT

N. Craig Smith London Business School

Regent’s Park London NW1 4SA United Kingdom Tel: 020-7706-6718 Fax: 020-7724-1145 e-mail:ncsmith@london.edu Sally S. Simpson

Dept. of Criminology and Criminal Justice University of Maryland—College Park

2220 LeFrak Hall College Park, MD 20742-8235 United States Tel: 301-405-4726 e-mail: ssimpson@crim.umd.edu Chun-Yao Huang

Department of Business Administration National Taiwan University No.1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei

Taiwan 106 Tel: 886-2-33661066

Email: cyhuang@management.ntu.edu.tw

March 2007

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Bruce Hardie, Jill G. Klein, William F. Laufer, Ray Paternoster, and John Roberts for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

WHY MANAGERS FAIL TO DO THE RIGHT THING: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF UNETHICAL & ILLEGAL CONDUCT

Abstract

We combine prior research on ethical decision-making in organizations with a rational choice theory of corporate crime from criminology to develop a model of corporate offending that is tested with a sample of U.S. managers. Despite demands for increased sanctioning of corporate offenders, we find that the threat of legal action does not directly affect the likelihood of misconduct. Managers’ evaluations of the ethics of the act, measured using a

multidimensional ethics scale, have a significant effect, as do outcome expectancies that result from being associated with the misconduct but not facing formal sanctions. The threat of formal sanctions appears to operate indirectly, influencing ethical evaluations and outcome

expectancies. Obedience to authority also affects illegal intentions, with managers reporting higher prospective offending when they are ordered to engage in misconduct by a supervisor.

Why do managers engage in unethical and illegal behavior? What are likely to be

effective remedies to this misconduct? One response to the recent wave of corporate scandals has been substantial custodial sentences for executives from firms such as Enron, WorldCom,

ImClone, Adelphia, and Tyco (Sorkin and Bayot, 2005). Some have questioned whether sentences as long as 25 years might be disproportionate to the crime (Economist 2004a). However, even with highly punitive sentencing of corporate offenders, there may be justifiable skepticism of its effectiveness in deterring future corporate misconduct. Despite frequent

demands for stronger regulations and increased sentencing, the study reported here suggests that the threat of formal sanctions may be ineffective, at least in isolation. Further, there might also be a role for ethics, though policymakers give this potentially important factor far less attention and researchers have only rarely considered the two in combination. In contrast, this article examines the role of both legal and moral constraints on corporate crime.

We view the misconduct evident in recent business scandals as a failure of moral and legal prohibitions. We draw on criminology as well as the management literature to develop and test a model of corporate offending, identifying how moral evaluations of the act, formal

sanctions and other possible outcomes (notably informal sanctions, such as the loss of respect of family and friends) serve to inhibit a manager from engaging in illegal and unethical conduct.

In the next section, we turn to criminology, where research on crime by firms and their managers has largely gone unnoticed within management research, including a rational choice theory of corporate crime that builds on a deterrence framework. We relate this to empirical research and conceptual models of (un)ethical decision making in organizations and build on the two literatures to propose our model and formulate hypotheses that are tested with a sample of managers. We conclude with a discussion of our findings, including their implications for managers and public policy.

CORPORATE CRIME DETERRENCE

In his seminal work, Sutherland defined white-collar crime as “crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation” (1983, p. 7; see also Sutherland, 1940). Sixty years on, his description resonates powerfully as we learn that the fraud in recent business scandals “involved knowing cooperation among numerous employees who were upstanding community members” (Anand, Ashforth and Joshi, 2004, p. 39).

Sutherland’s definition includes acts that solely benefit the perpetrator (e.g., embezzlement). Our interest, however, is in acts that are intended to benefit the organization (such as price-fixing or accounting fraud), though they might also, if only indirectly, benefit the individual perpetrating the acts.i This approach is consistent with Braithwaite’s (1984, p. 6) definition of corporate

crime as the “conduct of a corporation, or of employees acting on behalf of a corporation, which

is proscribed and punishable by law.” Our study focuses on acts of corporate crime that are unethical, at least according to Jones (1991, p. 367) definition: “an unethical decision is either illegal or morally unacceptable to the larger community.” As Jones acknowledges, there are limitations to the definition and there are also subtleties to the relationship between the law and ethics. For our purposes, it is sufficient to observe that illegal and unethical behaviors often share common characteristics and lend themselves to empirical inquiry in combination.

Deterrence Research

Criminologists have long considered the relationship between the threat of formal legal sanctions and crime. Although scholars have employed both objective and perceptual models of deterrent processes (Paternoster, 1987), perceptual models dominate. Perceptual deterrence assumes that the true impact of criminal sanctions on offending depends on an individual’s assessment of his/her own risks of getting caught and punished. The main components of deterrence include celerity (how swiftly sanctions are imposed), certainty (how likely sanctions

are to occur), and severity (the degree of consequence associated with the sanction). Each of these components is hypothesized to negatively affect crime, i.e., when sanctions are swiftly imposed, highly likely, and consequential (punitive), criminal behavior will abate. Additionally, deterrence is theorized to work at two levels. Specific deterrence occurs when an offender does not re-offend (or lowers his/her offending level in the future) as a consequence of punishment. General deterrence occurs when punishment levied against individual offenders lowers the offending risk in the general population.

Deterrence theory assumes that human behavior is reasoned and governed by free will and that persons will choose to be lawful if the pain associated with offending is greater than the pleasure it may bring (Beccaria, 1963). Research on the effects of rewards and sanctions on ethical decision-making in organizations reflects similar assumptions (e.g., Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Trevino and Youngblood, 1990). For deterrence scholars, the pain associated with

offending has mainly been conceptualized in legal terms (i.e., the threat and costs associated with criminal prosecution) and, until recently, there was little emphasis placed on the benefits of crime as part of the rational calculus. However, with greater theoretical integration in

criminology (post-1980), deterrence theory began to incorporate ideas from social control (e.g., the extra-legal costs associated with offending, normative beliefs), social learning (moral habituation), and rational choice (e.g., the benefits of crime/noncrime) perspectives.

While our interest is in corporate crime, tests of deterrence theory have overwhelmingly concentrated on traditional street crime populations. Early objective studies—in which deterrent effects generally were found for certainty but not severity (given measurement difficulties, celerity is rarely tested in deterrence research)—were unsophisticated methodologically (Nagin, 1978). Perceptual deterrence studies, which controlled for more variables and could establish proper temporal ordering, were less supportive of the deterrence doctrine—especially once

informal sanctions like stigmatic, commitment, and attachment costs were considered (Paternoster, 1987). However, there was some evidence that formal sanctions worked in conjunction with the perceived threat of social disapproval and moral commitment to inhibit illegal behavior (Grasmick & Green, 1980; see also Bachman, Paternoster, & Ward, 1992; Grasmick & Bursik, 1990).

Other criminologists, like Williams and Hawkins (1986), speculated that formal and informal sanctions did not operate independently of one another (Andenaes, 1974). Rather, the threat of legal sanctions (like arrest and prosecution) should trigger informal controls over behavior (shame and embarrassment). For example, in a study of wife assault, Williams and Hawkins (1989, p. 175) found that arrest was meaningful to men primarily through “the indirect costs that it poses for them in their social environments.” Even though respondents did not feel, on average, that going to jail for battering was likely (36%) or that they were apt to lose their jobs as a consequence of arrest (27%), the prospect of being fired, loss of self-respect, and social disapproval from significant others generated a sense of fear about arrest. For the most part, however, the interaction between formal and informal sanction threats has not been replicated when other types of illegal behaviors are examined (Bachman et al., 1992; Grasmick & Green, 1980; Klepper and Nagin, 1989; Nagin & Paternoster, 1991, see Burkett and Ward, 1993 for an exception).

The deterrent effect of informal sanctions may be contingent on an individual’s personal capital levels. Nagin and Paternoster (1994), for instance, found that sanctions deter best under conditions of high personal capital investment. Thus, the relationship between formal and informal sanctions may be particularly relevant for white-collar offenders—a set of offenders whose arrest probabilities are presumed rare, but who are also believed to have high indirect costs associated with arrest (Klepper & Nagin, 1989).

Unfortunately, in the white-collar and corporate crime area, empirical studies are rare. Most concentrate on white-collar offenders outside of the corporate setting (e.g., income tax cheating) instead of within it (e.g., accounting irregularities). When corporate deterrence is investigated, the individual or the organization may be the unit of analysis, with research results that are inconsistent and inconclusive (Simpson, 2002). For example, in their study of price-fixing in the white bread industry, Block, Nold, and Sidak (1981) compared firm and market price data before and after civil and criminal sanctions had been levied. They discovered specific and general deterrent effects for stepped up enforcement practices and more severe punishments. Simpson and Koper (1992), on the other hand, found little evidence of specific deterrence among a previously sanctioned group of anti-competitive firms in basic manufacturing industries. Company-level recidivism was generally unaffected by prior sanctions. Another study found the rate of home repair fraud in Seattle to decline after the number of convictions and severity of punishment against fraudsters increased—punishments that were publicly communicated via press releases (Stotland, Brintnall, L’Heureux, and Ashmore, 1980). Yet Jesilow, Geis, and O’Brien (1986: 222), using experimental data, offered evidence to suggest “that media attention and other interventions have no effect … on auto repair fraud.”

With the exception of the Jesilow et al. study, the above corporate crime research relies on “objective” measures of deterrence, tracking firm (or market) outcomes instead of measuring individual-level perceptions and actions. More recently, criminologists have drawn increasingly from a rational choice model to predict corporate misconduct (Braithwaite & Makkai, 1991). A rational choice (or subjective utility) model theorizes that the crime choice will be affected by individual perceptions of risk, effort, and reward (Becker, 1968). However, due to severe limitations in the strict economic model as it was applied to crime (see, e.g., Clarke and Felson, 1993, p. 5), criminologists have modified the perspective to give weight to concepts from

disciplines other than economics—especially the role of non-instrumental motives for crime and inhibitions against it. Paternoster and Simpson (1993), for instance, predict that a manger’s offending decision will be affected by: (1) the perceived benefits of legal noncompliance for oneself and the company, (2) the perceived formal and informal sanctions directed against

oneself and the company, (3) moral inhibitions against the act, (4) the organizational context, and (5) firm characteristics. Here it is assumed that self-interest is modified by ethics and that

behavior (e.g., the pursuit of self-interest) is guided by norms, custom, and procedures of organizations (Koford and Miller, 1991). As Vaughan (1998, p. 33) highlights, “decision-making… cannot be disentangled from social context, which shapes preferences and thus what an individual perceives as rational.”

The rational choice model presumes that the conditions that give rise to offending may be unique across offense types (Cornish & Clarke, 1986). Thus, crime specific models are

necessary—at least initially, to explore conditions that give rise to offending outcomes.

Likewise, researchers on ethical decision-making have argued for issue specificity, particularly if their studies rely upon Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior and Jones’ moral intensity construct (e.g., Flannery & May, 2000). Nonetheless, as later discussed, we believe there is scope for generalization, at least with relatively clear-cut issues of illegal and unethical conduct. Empirically, the rational choice model of corporate offending has produced mixed deterrence results. Braithwaite and Makkai (1991, p. 29) discovered only one formal sanction measure had the expected deterrent effect on regulatory compliance—leading the authors to declare the

deterrence model “a stark failure”. A later panel study also found a lone deterrent effect, but even this outcome was not uniform across executives. Deterrence was observed only for managers who scored low on emotionality (Makkai & Braithwaite, 1994). Paternoster and Simpson (1996) found stronger perceptual deterrent effects in their test of rational choice theory. However,

sanction threats (both formal and informal) were salient primarily among respondents with low moral restraint (using a unidimensional single indicator of how “morally wrong” respondents judged the act). Thus the illegal behavior may be judged so immoral by respondents as to be outside the realm of contemplation for persons with strong moral beliefs and sanctions are irrelevant (see also Burkett and Ward, 1993). Paternoster and Simpson also found that perceived personal and corporate benefits of offending were significantly associated with offending

propensity. Klepper and Nagin’s (1989, p. 237) study of tax compliance indicates that null results for deterrence measures may be caused by a “threshold” effect. “[A] simple test of the deterrent effect of criminal prosecution suggests that fear of criminal prosecution is irrelevant, whereas a threshold formulation of the deterrent effect of criminal prosecution suggests it is a very powerful deterrent.”

Overall, the small number of corporate deterrence studies coupled with contradictory findings leaves little room from which to draw firm conclusions. Results from these studies and other deterrence research highlight the need to measure deterrence as a perceptual process; to disentangle formal from informal sanction threats; and to include measures that capture the benefits of crime along with its cost. The limited evidence from the corporate crime literature indicates that formal legal sanctions may deter offending, but not for everyone. Deterrence may work best for persons who are not morally habituated (Paternoster & Simpson, 1996), who rank low on emotionality (Makkai & Braithwaite, 1994), or who have substantial investments in personal capital (Nagin and Paternoster, 1994).

Integrating Deterrence Theory with Research on Ethical Decision Making in Organizations

It is clear that the processes through which sanctions affect decision-making are not well understood, as yet. This study aims to improve understanding of corporate offending by drawing

on the ethical decision making literature as well as criminology. Perhaps surprisingly, the two literatures have coexisted up to this point with few attempts made to combine their insights.

Rational choice theories of deterrence in criminology are utility-based, with the decision to commit a crime hypothesized to be a function of its perceived costs and benefits. In applying this approach to corporate crime, Paternoster and Simpson (1993) have taken a broad view of costs and benefits that in many respects is consistent with research on ethical decision-making in organizations (e.g., organizational context, including perceived costs and benefits that extend to the organization as well as the individual). Further, they make provision for moral beliefs as a non-instrumental inhibitor of corporate crime. However, as Simpson and Piquero (2002) suggest, there is scope to substantially strengthen deterrence theory using behavioral theories from

management. For example, the rational choice model gives little attention to the role of

significant others, one of the more compelling findings of the ethical decision making literature. Research on ethical decision-making in organizations has relied extensively on the work of Rest and colleagues (Rest 1979; Rest, Narvaez, Bebeau and Thoma, 1999) on the psychology of morality (see, for example, Jones 1991, Trevino 1986), which in turn is based on Kohlberg’s (1969) theory of cognitive moral development and later (“neo-Kohlbergian”) refinements. Accordingly, Trevino and Weaver (2003), in reviewing this research, discuss a model of ethical decision-making in organizations comprising moral recognition, moral judgment and moral action. Few studies have given explicit attention to the legality of the decision, let alone the insights from criminology (Morris, Rehbein, Hosseini & Armacost, 1995 is one exception). However, issue intensity (Jones, 1991) is believed to contribute to moral issue recognition and it seems reasonable to assume that illegality would increase issue intensity and that there should be less ambiguity about the ethical nature of illegal conduct (and thus, again, increased moral recognition). Further, rewards and punishments have been shown to be an important contextual

factor influencing moral action (e.g., Tenbrunsel, 1998; Trevino and Youngblood 1990), though there has been little attention to the potential punishment from legal sanctions.

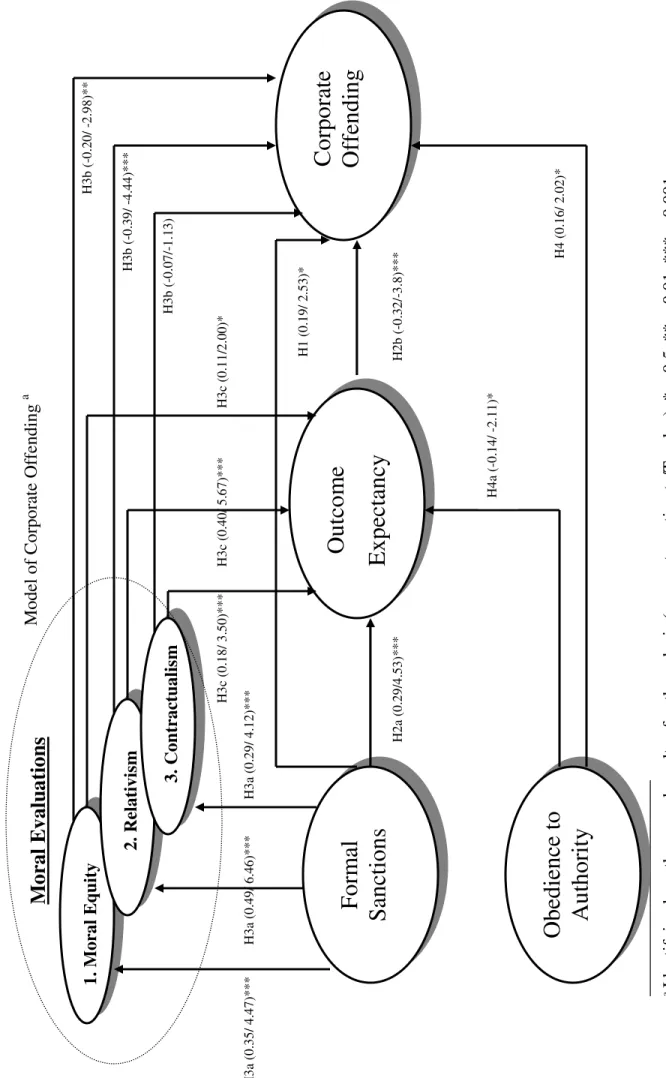

Our model incorporates key constructs predicted to influence corporate offending, focusing on the interplay of ethical judgment and the threat of formal sanctions and various “outcome expectancies” (see Figure 1). There is a well-established literature in criminology documenting the link between individual and firm interests (Clinard, 1983; Braithwaite, 1984; Reed and Yeager, 1996; Simpson and Piquero, 2002). Braithwaite’s definition of corporate crime, noted above, recognizes both individual and organizational levels of analysis and is compatible with our assertion that the decision to break the law, while ultimately made by an individual, is influenced by the organizational context (Paternoster and Simpson, 1993, 1996). It is also consistent with rational choice assumptions that choices are affected by an individual’s situational and contextual environment (Cornish and Clarke, 1986), as well as the person-situation interactionist model of Trevino (1986). Thus, in formulating our model of corporate offending, we include a role for a wide range of possible expectations as to the outcome of corporate crime. Trevino and Youngblood (1990) use the term outcome expectancies to describe organizational rewards and punishments for ethical or unethical behaviour. It is used more broadly here to include rewards and punishments that might extend beyond the organizational context.

____________________________ Insert Figure 1 about here ____________________________

The opinion of significant others (e.g., family, friends, peers) is included within outcome expectancies. The role of organizational peers in the rationalization and socialization processes at the heart of corruption is highlighted in a recent review by Anand et al. (2004). More broadly,

fulfilling the expectations of significant others is central to ethical decision making for

individuals at the conventional level in Kohlberg’s cognitive moral development framework and most adults are believed to be at this level (Trevino and Weaver 2003). A supervisor as a

significant other who might order an illegal and unethical act is incorporated separately in our model within the construct of obedience to authority. We treat this as a distinct latent construct because of its presumed antecedent role relative to outcome expectancies.

In our study, the constructs of formal sanctions, moral evaluations, outcome

expectancies, and obedience to authority are treated as latent variables that are not observed but relate to multiple observed variables (or indicators). Further, these constructs are hypothesized as causally related to each other and to the dependent variable of corporate offending. A more detailed exposition of the model follows in our formal statement of hypotheses and their supporting rationale.

HYPOTHESES

Formal sanctions. Formal legal sanctions are clearly intended to deter offending, but

rational choice models in criminology suggest that, as in other areas of human behavior, the deterrent effect of possible punishment might be weighed against potential gains, for the firm and the individual. Similarly, theoretical accounts of ethical decision-making in organizations suggest that the decision to engage in an unethical act will reflect an assessment of the perceived rewards and punishments for the action (e.g., Ferrell, Gresham & Fraedrich, 1989; Hunt & Vitell, 1986; Jones, 1991; Trevino, 1986). Empirical research provides some confirmation of the role of rewards and sanctions (Hegarty & Sims, 1978; Hunt & Vasquez-Parraga, 1993; Tenbrunsel 1998; Trevino & Youngblood, 1990). In the case of behavior that is both illegal and unethical, legal sanctions are a possible consequence and thus a potential barrier to engaging in the act.ii This is made explicit within rational choice theories of corporate crime (Paternoster & Simpson,

1993), with the prospective offender’s assessment of benefits and costs incorporating assessments of the perceived threat of formal sanctions.

Nonetheless, the threat of formal sanctions lies in their perceived certainty as well as severity. Research by Williams and Hawkins (1989) and Grasmick and his co-authors (Grasmick and Green, 1980; Grasmick and Bursik, 1990) found that formal sanctions for many offenses were not perceived to be highly likely. Indeed, general population estimates of sanction certainty varied considerably by offense type and over time (for instance, arrests for drunk driving and battery were perceived to be more probable than those for illegal gambling and petty theft; the perceived threat of arrest for tax evasion increased between 1980 and 1990). Overall, however, it is clear that despite frequent demands for stronger regulations or increased sentencing, formal sanctions may not be seen as certain (i.e., definitely would result in arrest) and thus may not directly inhibit corporate crime. Accordingly, many conventional crime studies challenge the predicted inverse relationship between sanction certainty/severity and offending (Piliavin, et al. 1986; Grasmick and Bursik, 1990; for a summary of other studies, see Paternoster, 1987).

However, Nagin and Paternoster (1994) suggest that formal sanctions may be more

salient for individuals high in personal capital; i.e., persons with substantial investments in

conventional commitments and attachments. Corporate managers are likely to rank high in personal capital compared with other potential offenders and are therefore more likely to be deterred by the perceived threat of formal sanctions. This lends weight to the basic argument about punishment as a potential deterrent to illegal conduct (of all kinds). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1. The perceived threat of formal civil, regulatory or criminal sanctions directly inhibits prospective corporate offending such that the greater the perceived threat of formal sanctions, the less the likelihood of corporate offending.

Formal sanctions and outcome expectancies. Traditional deterrence theorists directly link

and punished deters one from illegal activity. However, formal sanctions can also influence unethical and illegal behavior indirectly by setting expectations as to related negative or positive outcomes, such as losing the respect of family and friends or career advancement. Formal sanctions signal whether certain behaviors are acceptable to the broader society and thus denote social disapproval even if one is not “officially caught”. The reaction of significant others to misconduct offers a potentially powerful set of “informal” psychological and social sanctions (guilt, embarrassment, rejection) that are also likely to inhibit illegal behavior. Andenaes (1966) refers to this relationship between formal and informal sanctions as “the general preventative effects of punishment” and, as Tittle (1980:10) points out, informal sanctions may be a more salient and direct influence on behavior than formal sanctions. “[T]he rationale here is that negative reactions from significant others have greater relevance for one’s self-esteem, total life circumstances, and interaction patterns, and that greater surveillance and probability of being discovered are involved in informal activity.”

Thus, we suggest that even though offenders might not get caught by formal legal authorities, it is highly likely (given the interdependent nature of corporate offending) that significant others either know or will learn about the act.iii We believe that people rely on the anticipated opinions of referent groups when deciding how to behave (Jones and Ryan, 1997). To the extent that such knowledge will carry with it negative evaluations by others (reinforced by the educative effect of formal law) or, conversely, positive assessments by others who may hold negative views of the law (it is intrusive, unfair, or irrelevant to business), the existence of formal sanctions (and the anticipated reaction of others to the law) guides his or her sense of likely social disapproval or opprobrium. As Gibbs (1975:80) suggests, one possible consequence of formal law and punishment is normative valuation--“legal punishment may give rise to or at

least reinforce social condemnations of the act.” Thus, formal sanctions may affect behavioral intentions indirectly, mediated through other variables. Hence:

Hypothesis 2a. The perceived threat of formal sanctions on prospective offending will be mediated through expectancies as to the outcome of the act.

Outcome expectancies and misconduct. Outcome expectancies also are expected to act

directly on likelihood of engaging in the act (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Trevino & Youngblood 1990). Consistent with Paternoster and Simpson’s integrated rational choice perspective, when managers think that the firm or themselves will benefit in some way from corporate illegality (anticipate positive outcomes), the offending likelihood should increase. On the other hand, because managers also seek social approval from significant others, offending should be deterred if they feel those relationships would be damaged as a consequence of act discovery (again, informally rather than formally). More specifically, Jones and Ryan (1998: 433) have referred to “moral approbation” as the desire of moral agents to be seen as moral by themselves or others. Offending likelihood should also decrease if managers anticipate that the reputation of the firm would be tarnished. Thus:

Hypothesis 2b. The more negative are perceived outcome expectancies from engaging in the act, the less the likelihood of engaging in the act.

Formal sanctions and moral evaluations. The law is founded on societal norms regarding

right (ethical or moral) conduct. In theory, formal sanctions impart more than mere punishment for illegal behavior. Legal systems also educate societal members with behavioral and moral imperatives. As such, the law embodies and conveys social mores (Andenaes, 1974; Hawkins, 1969), which are believed to be key considerations for the majority of adults who are at a conventional level (Kohlberg’s stages three and four) of moral reasoning, with stage four specifically referring to a moral obligation to obey the law (Rest 1979, p. 29; but note the limitations of the stage model found in the neo-Kohlbergian model of Rest et al. 1999). Formal

sanctions are an important indicator of the morality of certain conduct and thus will influence the individual’s evaluations of the ethics of the act as well as his or her perceptions of the judgments of others. Persons who believe that certain behaviors are morally wrong but who contemplate violating the law might be especially deterred because the possibility of sanctions “would dramatize the inconsistency of the contemplated deviance with the moral commitments” (Tittle, 1980:18). Moreover, breaking the law is in itself generally considered unethical.iv Hence:

Hypothesis 3a. The perceived threat of formal sanctions on prospective offending will be mediated through moral evaluations of the act.

Moral evaluations and misconduct. In addition to the constraints of the law, managers are

also likely to base their decisions regarding corporate offending on their moral evaluation of the act. We know that moral reasoning is significantly associated with ethical and unethical conduct in the workplace (see review in Trevino and Weaver 2003). Theoretical models of ethical

decision making include moral philosophy or cognitions of right and wrong (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Hunt and Vitell, 1986; Trevino, 1986) and personal moral obligation has been empirically investigated in an organizational ethical decision making context (Flannery & May, 2000). Thus, formal sanctions may operate through an individual’s perceptions of “right” and “wrong”, but moral evaluations are likely to be formed independently as well as influenced by a threat of formal sanctions.

This view of moral reasoning has been challenged by social psychological accounts of moral disengagement. As Bandura et al. (2001) make clear, moral conduct is not simply the outcome of moral reasoning, but the result of self-regulatory processes subject to social

influences. Moral self-sanction can be selectively disengaged from unethical conduct through a variety of psychosocial mechanisms, many of which can be found in an organizational ethical decision making context (Anand et al. 2004; Bandura 2002). As Ashforth and Anand (2003)

observe, systems and individuals are mutually reinforcing. Further, an individual difference variable of moral identity—the individual’s moral self-conception—has also been proposed as a social-psychological motivator of moral conduct (Aquino and Reed 2002). Nonetheless, a role for moral evaluation remains, even if it is far from sufficient as an explanation for moral conduct (and, of course, our model to some extent incorporates social influences in outcome expectancies and obedience to authority). Hence:

Hypothesis 3b. Moral evaluations of the act directly inhibit prospective corporate offending. The less ethical the moral evaluation of the act, the less likely is misconduct.

Moral evaluations and outcome expectancies. We hypothesize that moral evaluations

also inform outcome expectancies. Individuals might reasonably anticipate being “punished” through informal sanctions for engaging in acts considered unethical. This is consistent with the moral approbation model of Jones and Ryan (1997, 1998). They hypothesize that the agent’s attributed level of moral responsibility in relation to the anticipated behavior will affect anticipated moral approbation. There is greater moral responsibility on the agent in situations involving unambiguously wrong behavior. Hence, we also predict that:

Hypothesis 3c. The less ethical the moral evaluation of the prospective act, the more negative are perceived outcome expectancies.

Obedience to authority and misconduct. Finally, as noted, we expect a role for significant

others in the workplace including, specifically, that some individuals would obey orders from a superior even when the acts involved are unethical. While there are many situational influences that affect ethical decision-making, obedience to authority is surely one of the most critical factors in an organizational context (and not least when examined in combination with the other key variables in our model). Decades of research have followed Milgram’s (1963) controversial but seminal studies of obedience, motivated by Nazi atrocities of the Second World War, extending to more recent research specific to the business organization context, in both

management (e.g., Brief, Dietz, Cohen, & Vaslow, 2000) and sociology/criminology (Kelman and Hamilton, 1989, pp. 45-46; Reed and Yeager, 1996).

Kohlberg’s first stage of moral development is where “being moral is being obedient” and obedience brings freedom from punishment (Rest, 1979, p. 24). Obedience can also bring freedom from moral reflection and a sense of individual responsibility. Although postulated as an early childhood stage, it is arguably reflected in the words of Nazi administrator, Adolf

Eichmann, who famously justified his role in the Final Solution by asserting that he was following orders and commented, “Today, 15 years after 8 May 1945, I know… that a life of obedience, led by orders, instructions, decrees and directives, is a very comfortable one in which one’s creative thinking is diminished.” Obedience, for good or bad, isn’t just for children.

Bandura’s social cognitive theory of the moral self posits that moral reasoning is linked to moral action through affective self-regulatory mechanisms, but highlights that people do not operate as autonomous moral agents and are subject to the social realities in which they are embedded (see Bandura 2002). These social realities result in mechanisms of moral

disengagement by which self-sanctions, that would otherwise prevent conduct in violation of a person’s moral standards, are not invoked. Moral disengagement can occur through the

displacement or diffusion of responsibility. A person’s moral agency can be obscured by the perception that their actions are the dictates of legitimate authorities (simply following orders) or a group responsibility, rather than something for which they are personally accountable.

Moral disengagement has been used in management to explain corruption in

organizations (see Ashforth and Anand 2003; Anand et al. 2004) and obedience to authority more generally has long been incorporated in models of ethical decision-making (e.g., Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Jones, 1991). In criminology, Clinard’s (1983) interviews with retired middle managers found that many felt unduly pressured by top management and supervisors to meet

performance targets by “whatever means necessary.” Similarly, studies by Kram, Yeager and Reed (1989) and Jackall (1988) highlight the routine ethical dilemmas confronting managers in organizations that devalue and de-legitimate personal ethics in workplace decisions. Quoting a former vice-president of a large firm, Jackall (1988, p. 6) reports, “What is right in the

corporation is not what is right in a man’s home or in his church. What is right in the corporation is what the guy above you wants from you.” Kelman and Hamilton (1989: 209) suggest that subordinates experience a tension between role responsibility and causal responsibility when they are confronted with illegitimate orders from superiors. In their research, actors confronting potential “crimes of obedience,” tended to invoke a “role-based motives” model in which

subordinates claim a duty to obey (often supported by the authorities’ power to impose sanctions when orders are not obeyed). When lower-level managers are ordered to violate the law under these kinds of conditions, they can claim a lack of responsibility as “subordinates” —effectively splitting the object self from an acting self—to use Coleman’s terms (1990). Hence:

Hypothesis 4. Obedience to authority influences the likelihood of prospective corporate offending. Individuals are more likely to engage in the (unethical and illegal) act when ordered by a supervisor than when making the decision him/herself.

Obedience to authority and outcome expectancies. We anticipate that obedience to

authority brings a diminished sense of personal responsibility and thus affects outcome expectancies, as indicated (e.g., obedience brings freedom from punishment), as well as

behavioral intentions (Bandura 2002; Kelman and Hamilton 1989). Authority structures within the corporate hierarchy allow those who take orders to distance themselves from behavioral responsibility and the consequences of the act. Separating the object self from the acting self (Coleman, 1990) should serve to diminish the perceived consequences of ordered actions, whether they be positive or negative.

Hypothesis 4a. Individuals will perceive the outcome of an (unethical and illegal) act to be less negative when ordered by a supervisor than when making the decision to engage in the act him/herself.

METHODS

Respondents and Procedure

We tested our model and hypotheses with 233 observations from 78 managers using a survey instrument that comprised three scenarios, each followed by 32 questions that related to the situation described in the scenario, and concluded with 14 questions about the respondent and his or her organization. This instrument was designed as part of a larger project that examined individual and organizational factors associated with managers’ decisions to engage in corporate crime. It is a modified version of an earlier instrument that was then pretested (with graduate students), revised, and administered to first year MBA students and a small group of executive education managers. Modifications were made based on (1) recommendations from focus group participants (made up from respondents in the first study); (2) scenario elements deemed

“unrealistic” by respondents, and (3) the removal of redundant or theoretically irrelevant items.v Each scenario described a hypothetical situation where a manager decides whether to engage in an unethical and illegal act: price-fixing, bribery, or violation of emission standards. While the act required was identically described (e.g., “meet with competitors to discuss product pricing for the next year”), its context differed, with specific features of each scenario randomly assigned (e.g., a firm would be described as diversified or not; benefits accruing to the firm from engaging in the act included saving the firm a large or a small amount of money).vi A sample of three vignettes (for each offense type) is reported in Appendix A.

In every hypothetical case the manager decides to engage in the illegal act (though respondents are not told it is such) and the first question asked of respondents is their likelihood of acting as the manager did under the circumstances. Respondents are then asked how realistic

they found the scenario, how much their career might be advanced by doing as the manager did in the scenario and how thrilling this would be, and their ethical evaluations of the act. The next set of questions asks about the likelihood of formal sanctions (criminal, civil and regulatory). These questions are followed by questions asking about the likelihood of various other possible outcomes (e.g., dismissal) under the assumption that formal sanctions did not result (i.e., if they were not “officially caught”). The final set of questions for each scenario asks about

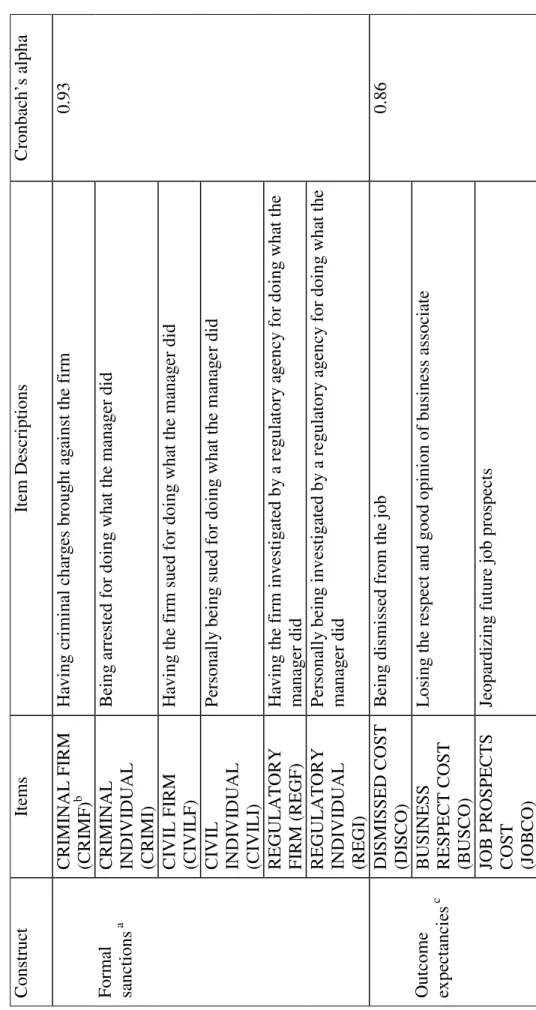

respondents’ sense of how severe (how much of a problem) formal sanctions and other possible outcomes would be for themselves and the depicted firm. Questions about the respondent and his or her organization come after the final questions for the third scenario (see Table 1).

____________________________ Insert Table 1 about here ____________________________

Our preference for a sample comprising practicing managers of various ranks together with the length of the survey instrument necessitated drawing respondents from three sources. The first source was a group of managers from a subsidiary of a Fortune 500 U.S. consumer goods company. The second group of managers was attending an executive MBA program at a mid-Atlantic university. The final group of respondents was drawn from a group of MBA students at the same university. For the measurement items (discussed below), the average ICC(1) (intraclass correlation coefficient) for pooling the three groups of respondents is 0.027. As ICC typically ranges from 0 to 1 and ICC=0 indicates that there is no effect of grouping factor (Cohen, Cohen, West & Aiken, 2003: 537-538), an average ICC(1) of 0.027 implies that across the measurement items the grouping factor is negligible and thus confirms the

The first group of respondents was recruited through a senior vice president who

distributed the questionnaire to approximately 100 managers primarily located within the finance and finance-related areas (e.g., audit) of the subsidiary. Our cover letter stressed the anonymity of the survey and provided an envelope so that the completed questionnaire could be returned directly to us. We received 31 completed questionnaires, for a response rate of 31%. The research instrument also was administered to the groups of executive MBA and full-time MBA students in a classroom setting. Those interested in participating were asked to complete the questionnaire outside of class and return it at the next class meeting or to a sealed box in a central location. We received 47 completed questionnaires from the 128 potential participants, for a response rate of 37%. Thus our overall response rate is 34%. (This is a conservative estimate. While we provided the SVP with 100 surveys, as few as 50 may have actually reached potential respondents.)

The unit of analysis in this research is the specific offending judgment tied to each scenario. The assumption is that each scenario presents the respondent with a set of conditions that will affect his or her choice (in this case, to offend). Hence, with 78 usable questionnaires, each with three judgment scenarios, a total of 234 possible observations were produced (see Rossi and Nock, 1982). Of the 234 observations, one was eliminated because of missing data. The final number of observations was therefore 233.vii

Our respondents were mostly in their mid-thirties, white, and of U.S. nationality. Two-thirds were male, over half were married and they were well educated, with over two-Two-thirds attending or having completed a graduate degree program. Most were experienced managers, with an average of just over 12 years’ business experience. Many had indirect experience of issues similar to those described in the scenarios.

This study examines the interaction of ethics and the law with respect to a decision to engage in illegal and unethical conduct. Our focus was on four sets of independent variables: formal sanctions, moral evaluations, outcome expectancies, and obedience to authority.

Measures

Dependent variable. The dependent variable is the respondent’s estimate of his or her

likelihood of doing as the hypothetical manager did in the scenario (coded as “COMMIT” in the tables). The measure comprised an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (“no chance at all”) to a mid-point of 5 (“50% chance”) and an end-mid-point of 10 (“100% chance”). The illegal and unethical nature of the act and the likelihood of social desirability bias notwithstanding, the mean for COMMIT was 1.57 (s.d. = 2.18). Across scenarios, more than 42% of respondents indicated that there was at least a 10% chance that they would do what the manager did (60% of respondents for the price fixing scenario, 47% for illegal emissions, 42% for illicit cash payment).

Formal sanctions. The construct of formal sanctions comprised measures of the

perceived chance and severity of criminal charges or civil actions against the individual or the firm, or of the individual or the firm being investigated by a regulatory agency as a result of the action described in the scenario. Questions about the likelihood of formal sanctions come shortly after the scenario (e.g., what is the chance you would be arrested for a criminal offence if you did what the manager did under these circumstances? This was coded as “CRIMINAL CHANCE”). Responses were on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (“no chance at all”) to a mid-point of 5 (“50% chance”) and an end-point of 10 (“100% chance”). Because corporate crime is more likely to be discovered and processed by regulatory agencies or through civil means, we include these sources of formal sanction threat along with those associated with criminal justice system processing.

After questions about the likelihood of other possible outcomes, respondents were asked to estimate how much of a problem various circumstances would create in their lives, including criminal charges, civil actions and regulatory investigation as a result of the manager’s action (e.g., being arrested for doing what the manager did, coded as “CRIMINAL SEVERITY”). Responses were on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (“no problem at all”) to 3 (“small

problem”), to 7 (“big problem”), to 10 (“a very big problem”). In the rational choice literature in criminology, it is presumed that certainty and severity will equally affect the decision making of a would-be offender who is an expected utility maximizer (Nagin, 1998: 21).viii Thus, we

multiplied the estimated certainty of each sanction by its corresponding severity estimate to provide our perceived threat of formal sanctions variables (“CRIMINAL INDIVIDUAL, CRIMINAL FIRM, CIVIL INDIVIDUAL, CIVIL FIRM, REGULATORY FIRM,

REGULATORY INDIVIDUAL.” For example, CRIMINAL INDIVIDUAL, the threat of formal sanctions against the individual, comprised CRIMINAL CHANCE x CRIMINAL SEVERITY.). See Table 2 for a list and description of construct items.

____________________________ Insert Table 2 about here ____________________________

Moral evaluations. The use by managers of normative ethics concepts from moral

philosophy (whether knowingly or more intuitively) has been widely theorized (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Hunt and Vitell 1993; Jones 1991). Respondents’ moral evaluations of the manager’s action described in the scenario were measured using Reidenbach & Robin’s (1990) widely adopted Multidimensional Ethics Scale (MES). This scale was originally developed from items reflecting major theories of ethics, including justice, utilitarianism, and deontology. Our use of a multidimensional measure contrasts with the more typical use of univariate measures of

moral evaluation in criminology (e.g., Paternoster and Simpson, 1996). Reidenbach and Robin (1990, p. 648) found that “the multidimensional measures explained a substantially greater amount of variance in the intention scores” than a univariate measure of ethics. Further, ethical judgment is a complex construct; as Reidenbach and Robin (1990, p. 639) observe: “individuals use more than one rationale in making ethical judgments.”

The three dimensions of the MES are “moral equity” (i.e., just/unjust, fair/unfair, morally right/not morally right, acceptable/not acceptable to my family), “relativistic” (i.e., culturally acceptable/unacceptable, traditionally acceptable/unacceptable), and “contractualism” (i.e., violates/does not violate an unspoken promise and violates/does not violate an unwritten contract). Respondents were asked to give their beliefs as an individual about the manager’s action, with each of the eight items measured on a 7-point scale (see Table 2 for items).

Outcome Expectancies. The construct of outcome expectancies measures respondent

perceptions of positive or negative outcomes for the individual and his/her firm if the illegal act were discovered informally. Five were measures of the perceived chance and severity of

dismissal from the company, jeopardizing future job prospects, and loss of respect and good opinion of business associates, of good friends and of family, as a result of the action described in the scenario. Two further variables were measures of whether the respondent would feel a sense of guilt and shame if others knew of the action and if the action tarnished the reputation of the firm, together with the severity of these possible outcomes. It will be recalled that these measures are under the assumption of not being legally discovered. Specifically, respondents were given the following instruction: “For the next set of questions, assume that you did what the manager did under these exact circumstances. Assume also that although you or the company were not arrested, investigated, or sued, it did somehow become known that you had done this. Under these assumptions…” Responses to the five perceived chance questions were on an

11-point scale, ranging from 0 (“no chance at all”) to 10 (“100% chance”). Responses to the two sense of guilt or shame questions were yes/no. ix

Responses to the severity questions followed the instruction: “We would now like you to estimate how much of a problem the following circumstances would create in your life.” They were also on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (“no problem at all”) to 10 (“a very big

problem”). Multiplying the estimated certainty of each outcome by its corresponding severity estimate provided our measures for the preceding outcome expectancy variables. Finally, we measured positive outcomes by asking whether respondents thought the action would enhance their career prospects (also on an 11-point scale, from “not at all” to “a great deal”). (See Table 2 for a description of construct items.)

Obedience to Authority. Obedience to authority was treated as a simple dichotomous

variable within the scenario. Respondents were told either that the manager decides to engage in the act or that the manager is ordered to do so by a supervisor.

RESULTS

Our hypotheses look at how interrelated constructs influence a manager’s likelihood of engaging in illegal and unethical conduct. To test our model based on this set of hypotheses and to investigate the direct and indirect effects of constructs of concern simultaneously, we use a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach in our empirical analysis. The hypothesized model was estimated with LISREL8 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993), with the covariance matrix as input. To run the hypothesised structural equation model, we allowed certain within-construct items to be correlated in the measurement model.

As the MES captures three different dimensions of ethical decision-making, our analysis treated these dimensions separately. Figure 1 presents the empirical model thus specified, with model estimates and t-values (Cronbach’s alphas for constructs are reported in Table 2 and a

correlation matrix for the main constructs is reported in Table 3, with a full correlation matrix provided in Appendix B).x To check model validity, we found that each item has a statistically significant (p<0.01) loading on its posited underlying construct factor. Following Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and Bagozzi and Phillips (1982), we calculated confidence intervals of the interfactor correlations (phi) and found all of them to be significantly less than 1.0. The estimated chi-square statistic for the SEM model is 530.50 (p <0.01, with 205 degrees of freedom), RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.87, NNFI = 0.89, IFI = 0.92, and GFI = 0.84. These fit indices show a reasonable fit.

____________________________ Insert Table 3 about here ____________________________

Figure 1 shows that hypotheses H2a, H2b, H3a, H3b (on moral equity and relativism), H3c, H4 and H4a are all supported by this empirical model (t values greater than 1.96). The hypothesized direct and inhibitory effect of formal sanctions on corporate offending likelihood (H1) is not supported (the path is significant but the coefficient is positive rather than negative). H3b hypothesized the effect moral evaluations have on corporate offending likelihood. Among the three dimensions of MES, moral equity and relativism are found to exhibit the expected effect relative to the “commit” decision, but the influence of contractualism is not statistically significant.xi We attribute this finding to the emphasis in the contractualism dimension on unspoken promises and unwritten contracts which we might expect to be less salient relative to codified illegal conduct (the decision is about illegal as well as unethical conduct and thus “written” if not also “spoken”).

The result on H1 indicates that when we control for indirect effects through perceived consequences and moral evaluations , formal sanctions fail to directly inhibit reported offending

likelihood and actually increase the probability of prospective corporate offending. xii This result is notwithstanding relatively high perceptions of sanction certainty (mean perceived score on an 11-point scale for certainty of individual criminal sanctions = 3.88, civil sanctions = 3.56, and regulatory sanctions = 4.58; for certainty of firm sanctions it was 4.65, 5.05 and 5.59,

respectively) and severity (mean perceived score for severity of individual criminal sanctions = 9.48, civil sanctions = 9.35, and regulatory sanctions = N/A; for severity of firm sanctions it was 8.42, 8.26 and 7.85, respectively).

Overall, however, the total effects of formal sanctions (including indirect effects) do show inhibitory influences. Parameters from our path analysis show that the total (standardised) effects that formal sanctions have on offending likelihood is -0.27 (see Hayduk, 1987).xiii This finding suggests that formal sanction threats do not operate alone but are mediated through other variables; formal sanction threats operate indirectly, with perceived consequences and moral evaluations playing important roles.

More specifically, we find that the positive impact of formal sanctions on outcome expectancies and moral evaluations are both significant; supporting hypotheses H2a and H3a (see Figure 1 for standardized path estimates and significance levels). Further, in H2b we predict a negative association between perceived outcome expectancies and the likelihood of illegal conduct. This hypothesis is supported and support was also found for the hypothesis that that the moral evaluations of the act directly (H3b) and indirectly, through outcome expectancies (H3c), inhibit offending propensity. Finally, the hypothesis that an agent is more likely to engage in prospective corporate offending if s/he is ordered to do so by a supervisor (H4) is supported. Being told by supervisor to violate the law is also significantly associated with outcome expectancies (H4a).

Our results demonstrate that both moral evaluations and outcome expectancy play important mediation roles for formal sanctions to inhibit potential corporate offending. An

alternative model run without these two constructs (i.e., a nested model with only the paths of H1 and H4 in Figure 1) shows that formal sanctions inhibit corporate offending inclinations

(coefficient for the path from formal sanctions to corporate offending = -0.25, t-value = -2.16). However, a chi-square test between the full and the nested model (change in chi-square=213.77, d.f.=12, p<0.01) shows that the former has a significantly better fit. It is clear that the full model which takes into account the mediation effects of moral evaluations and outcome expectancy is a better fit to the data.

In addition to the pooled analyses discussed above, we also ran a series of scenario-specific empirical structural equation models to see whether the results reported above are violated in specific scenarios (price fixing, bribery, and EPA emissions violation). We find that all paths have the same coefficient signs as in the pooled-data model, with the exception that obedience to authority is positively but insignificantly related to outcome expectancies (p> 0.1) in the price-fixing scenarios.

DISCUSSION

Our study explores why managers fail to “do the right thing” and, instead, report a propensity to engage in unethical and illegal conduct. It provides support for a model of decision making on misconduct in business that treats the decision as influenced by the interaction and direct effects of moral evaluations of the act, outcome expectancies and obedience to authority, with formal sanctions operating indirectly. Our research supports and goes beyond the extant criminology and management literatures in a number of respects, not least in combining the two.

From a criminological perspective, our study augments the limited number of perceptual studies of a rational choice perspective on corporate crime and addresses some of their

inconsistencies. Our results are consistent with and build upon the integrated rational choice perspective developed and tested by Paternoster and Simpson (1993, 1996). The findings suggest that criminal decision-making within the firm is both utilitarian and deontological (Reidenbach & Robin, 1990). To the extent that managers employ a subjective utility model, corporate offending decisions appear to be more directly affected by controls (evident in our outcome expectancies variable) found in social networks (within and outside of the workplace) and less by legal ones. However, as Williams and Hawkins (1989) found in their study of wife assault, legal threats can trigger social controls that, in turn, inhibit offending intentions. Some studies have failed to replicate this interaction (see, e.g., Nagin & Paternoster, 1991), but it is possible that we find this effect because the triggering mechanism rests with the social embeddedness of our sample. In other words, only those who perceive high social costs associated with offending will be susceptible to the formal sanction trigger. Because our respondents have attained high levels of social capital (education, work, respect of family), such an interaction is more likely than in studies with other samples (Nagin and Paternoster, 1994; see also, Klepper & Nagin, 1989).

Similarly, we find that formal sanction threats affect offending decisions through moral evaluations of the act, consistent with claims about the moral and educative effects rendered by criminal law (Andenaes, 1974; Beccaria, 1963; Hawkins, 1969). However, few studies have examined empirically potential interactions between formal sanction threats, moral evaluations, and criminal behavior. In addition to considering these relationships, this study broadens the potential basis of moral socialization to include civil and administrative law. Work by

Paternoster and Simpson (1996), using a similar sample of respondents, found that the offending proclivities of persons high on moral commitment were unaffected by criminal, civil, or

regulatory sanction threats (certainty and severity). However, the threat of formal sanctions lowered reported intentions for persons who ranked below the median on moral commitment.

Our results are in line with those of the earlier study, but we believe this research is a stronger test of these relationships. In the Paternoster and Simpson study, moral commitment was measured using a single item indicator (i.e., persons were asked to rank four corporate criminal behaviors on an 11 item scale according to perceived immorality of the act). Moral evaluations are measured in this study using a multiple indicators from the MES scale and we are thus better able to capture a fuller range of ethical evaluations.

Finally, the rational choice model builds on the idea that criminal choices are affected by context “…not only because different crimes may serve different purposes, but also because the situational context of decision-making and the information being handled will very greatly among offenses” (Clarke & Felson, 1993: 6). The vignette structure of this study allowed us to explore whether the results from the full (pooled) model varied by crime type. Generally, the three types of corporate offending examined (EPA emissions violation, price-fixing, and bribery) showed similar effects and, when effects did vary, the differences were related to magnitude and not direction.xiv More studies are needed, but these results (imply that decisions to engage in corporate offending (and clear-cut unethical conduct) may stem from similar etiological processes and crime (or issue) specific models may be unnecessary.

Support for our model is consistent with theoretical and empirical accounts of ethical decision making in the management literature and goes beyond them by focusing on illegal and unethical conduct. It reflects a conceptual consistency with a model of ethical decision-making in organizations broadly comprising moral recognition, moral judgment and moral action (Trevino and Weaver 2003). However, by looking at the likelihood of both illegal and unethical conduct (as recommended by Flannery and May 2000), we increased the possibility of moral recognition (through heightened issue intensity), affected moral judgment (through the moral obligation to obey the law, found at the conventional stages of Kohlberg’s model), and influenced moral

action (by broadening the scope of potential punishment), with results consistent with the theorized roles of these variables in ethical decision making (see review in Trevino and Weaver 2003).

We confirmed the influence on ethical decision making of a broadened conception of outcome expectancies (Trevino and Youngblood 1990), with rewards and punishments that extended beyond the organization. Obedience to authority remained a critical variable notwithstanding the illegality of the conduct in question. Further, support for the model is consistent with anticipated interactions amongst these variables and we found both direct and indirect effects (e.g., for moral evaluations through outcome expectancies).

Implications for Policymakers and Managers

As well as our aim of better understanding why managers engage in misconduct, we also wished to consider possible remedies. The degree of current societal concern about unethical and illegal conduct by business certainly matches, if not exceeds that of previous periods, such as the Wall Street abuses of the mid-Eighties (Stewart, 1991). Its adverse consequences are manifest in multiple ways, ranging from surveys reporting diminished trust in business to associated declines in equity markets. Responses include efforts by individual firms to step up compliance programs and improve corporate governance, and regulatory interventions. However, empirical support for specific types of interventions is limited.

Policymaking. The findings from this study suggest that regulatory interventions in the

form of increased formal sanctions may not be sufficient, at least in isolation; for example, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, acting consistent with the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation of 2002, issued guidelines to federal judges doubling the recommended sentence from five to ten years for certain corporate crime offences (Johnson, 2003). This is not to imply that this and other

sanctions can reduce the likelihood of misconduct indirectly, by acting on outcome expectancies and moral evaluations. Formal sanctions are more likely to be effective if associated with the prospect of loss of respect of business associates, friends and family. Further, formal sanctions are indicative of society’s views of the morality of certain conduct, influencing the individual’s moral evaluations of the act. The public reporting of a doubling of sentences in the guidelines— and in subsequent court cases—seems likely to support an increase in the perception of these crimes as morally wrong and thus strengthen social controls. Similarly, jail sentences for public figures such as Martha Stewart have an educative effect (though they might also reduce efforts for more fundamental reforms; see Economist, 2004b). Hence, communication of regulatory changes is key, including attention to how moral opprobrium is conveyed. This is one important way by which it is useful for policymaking to speak to both ethical and legal constraints.

Our respondents rated formal sanction severity higher than certainty (for both the firm and the individual) and severity as higher for the individual than the firm and high in absolute terms (mean of 9.4 for the individual on our 11-point scale and 8.2 for the firm; p <0.001). This might suggest that our respondents, at least, have come close to a ceiling and increased severity of formal sanctions might not have as much effect on curbing misconduct as increased attention to the perceived certainty of sanctions (the methodological assumption of equally proportionate contributions of certainty and severity notwithstanding). To the extent that this is applicable to corporate crime in general, government attention to (and communication of) the enforcement of existing law might be more effective than making laws more punitive (e.g., doubling of jail terms). It is interesting to note that our respondents also perceived a higher certainty for firm sanctions than for sanctions against themselves, contrary to practice (Laufer 1999) and this perhaps reflects ignorance or wishful thinking.

Managerial Implications. Measures at the industry and firm level might increase the effect of formal sanctions on outcome expectancies and moral evaluations. Managers are often ignorant of the law (Petty, 2000). Consistent with deterrence theory and the findings of this study, there appears to be a case for interventions that better familiarize managers with the law

and convey the moral opprobrium attached to illegal conduct (signaling societal expectations). In such a way, both moral evaluations and outcome expectancies may be influenced by greater awareness of formal sanctions. Note that our model and findings suggest that this is important in the absence of managers believing they or the firm will “get caught”. Further, our finding of obedience to authority for illegal conduct highlights the importance of measures that encourage managers to question illegal orders (e.g., through anonymous hotlines).

More fundamentally, our study speaks to the importance of legitimating the use of ethics in business discourse and decision making. Where managers are ignorant of the law or where the law does not proscribe unethical conduct (Stone, 1975), encouraging recognition of the ethical dimensions of a business situation increases the possibility of constraints on unethical conduct. That said, ethical evaluations are not the root problem in many instances of business misconduct because of psychological processes such as moral disengagement (discussed further below) or, more simply, a lack of moral courage (Kidder 2005).

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

There are some major limitations of our study. First, our sample is small and restricted— drawn from a mix of working mangers and students with prior business experience. Moreover, the fact that respondents were a convenience sample and the relatively low survey response rate affects the generalizability of our results. The use of student samples for research purposes is especially problematic when the behavior of interest is rare in the sample population (e.g., violent offending). However, our respondents either currently work or, as MBA students, have

significant prior work experience. A substantial proportion of them report personal knowledge of the offending situations described in the scenarios. Therefore, the restricted sample is less

problematic here than in other kinds of studies.

Additionally, critics often challenge the hypothetical scenario technique as contrived. The instrument does not actually measure offending behavior, but instead captures offending

intentions. On the other hand, there is a sizeable body of research that explores the relationship between offending intentions and behavior. Many studies find a high correlation between offending intentions and actual behaviors (see Simpson, Paternoster, & Piquero, 1998 for a review). Pogarsky (2004), for instance, recently compared hypothetical offending intentions with observed heterotypic behavior (cheating) using an experimental design. He found a high degree of correspondence between the two measures of anti-social (and unethical) behavior.

Thus, while these methodological concerns are not without merit, the nature of our task— at least at this point—is exploratory. Because our results are consistent with theoretical

expectations and results from other studies, we are confident that the processes we have observed are meaningful and worthy of further study.

A different set of concerns revolves around the validity of our findings relative to practice—what actually enables misconduct to happen within organizations. As earlier noted, rationalization tactics may preclude evaluations of misconduct as unethical. If the theorizing of Anand et al. (2004; also see Ashforth and Anand 2003) is correct, then our claims regarding a greater reliance on ethics (or the law) may have more limited application. Further, our focus on illegal and unethical conduct excludes many troubling behaviors that are, nonetheless, legal. However, it has the merit of addressing issues of great current societal concern. Our findings might be less relevant to more ethically ambiguous conduct. In practice, however, this also

speaks to the value of managers knowing more about theories of ethics so they can make better ethical judgments in the absence of guidance from the law.

Further Research. There has been surprisingly little research on interventions to reduce

the likelihood of unethical and illegal conduct in organizations. Our study questions whether internal compliance systems can be adequate guarantors of ethical behavior (also see Weaver and Trevino 1999) and whether legal sanctions alone are likely to deter managers from offending. Ayres and Braithwaite (1992) have argued that corporate crime prevention should draw from a pyramid of enforcement—what they call the “benign big gun strategy.” The model assumes that most managers willingly comply with the law and that an internal compliance system that reinforces ethical conduct will succeed most of the time. However, this model (built around persuasion and cooperation) will only be effective when more punitive responses also are available (the “big gun” in a hierarchy of increasingly punitive measures). While our results provide some support for this model, more research is needed to learn about the conditions under which offenses are likely to occur (i.e., organizational “hot spots”), when punitive sanctions are apt to backfire perhaps leading to defiance (Sherman, 1993), whether there is a “tipping point” for sanction effects (Klepper and Nagin, 1989), and the inter-relationships among individual traits, situational characteristics, and offending propensities (Makkai & Braithwaite, 1994). Moreover, our study and research on ethical decision making more generally, suggest that more attention needs to be given to the interaction of values and compliance in ethics programs and to the psychological processes associated with rationalization tactics. Finally, our study suggests that the MES dimensions might be domain specific, with contractualism seemingly less salient in the context of illegal conduct. This warrants further exploration.