事件嚴重性、來源可靠性、品牌依賴程度對消費者態度和產品評估改變的影響 - 政大學術集成

79

0

0

全文

(2) ABSTRACT. Negative events are known to drawn more attention than positive events, but how consumers’ brand attachment would interact with negative events is rarely discussed in. 政 治 大 source credibility of a negative event, and consumers’ brand attachment would affect 立. the literature. As a result, this research would like to investigate how severity level and. ‧ 國. 學. consumers’ negative brand attitude change, negative product evaluation change and perceived risk change through studying of young adults who use brand cell phone.. ‧. In this research, it is found that when a brand is attacked by a negative event,. y. Nat. sit. consumer’s brand attachment and the severity level of a negative event would both affect. n. al. er. io. consumer’s negative product evaluation and negative product evaluation changes, though. Ch. i n U. v. only brand attachment would affect consumers’ brand attitude. Furthermore, brand. engchi. attachment cannot resolve negative impacts of a negative event to the consumers; instead, the severity level and the source of a negative event would affect consumers’ negative brand attitude, negative product evaluation and perceived risk changes. Specifically, it is worth the brand managers the most attention when a negative event involves high severity level and comes from a more credible source, as this combination bring more negative changes to consumers, and the least attention when a negative event involves low severity level and comes from a less credible source, as this combination would bring least negative changes to consumers. ii.

(3) ACKNOWLEDEGMENT. 2 years of Master study in International Business in National Chengchi University fly away in a blink of eye. I was once a freshman in the campus and a newcomer to. 政 治 大 I must conclude my master study with a memorable event, there is nothing comparable to 立. Taipei; all of sudden, I was wearing my graduation gown and ready to leave the school. If. ‧ 國. 學. my master thesis research that occupied me for nearly a year.. The person who should get the most credit is for sure my thesis advisor, professor. ‧. Jyh-Shen Chiou (邱志聖). He is the one who provided me guidance and timely feedbacks. y. Nat. er. io. sit. (yes, even in the Chinese New Year) whenever I hit a wall in the middle of research. I am also thankful for valuable assistance and suggestions from senior Szu-Yu Chou (周思妤).. al. n. v i n C h from pals who spent Of course I did not forget supports e n g c h i U good time eating out, hanging around and exchanging information with me (the name list is way too long, please tag yourself).. The end of the master study is indeed not an end, but a beginning for everyone. I am grateful to whom I have met and what I have learnt. Wish everyone all the best in the future.. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Chapter. Page. I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.................................................................................................. 1. 政 治 大. 1.2 Research Questions ...................................................................................... 4. 立. 1.3 Research Process.......................................................................................... 5. ‧ 國. 學. II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS ................................................... 6. ‧. 2.1 Brand Attachment ........................................................................................ 6. y. Nat. sit. 2.2 Source Credibility ........................................................................................ 9. n. al. er. io. 2.3 Event Severity............................................................................................ 12. Ch. i n U. v. 2.4 Hypothesis Model ...................................................................................... 18. engchi. III. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................ 19 3.1 Research Design ........................................................................................ 19 3.2 Variables Manipulation and Measurement.................................................. 23 3.3 Sample Screening....................................................................................... 32. iv.

(5) Chapter. Page. IV. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ........................................................................... 33 4.1 Data Summary ........................................................................................... 33 4.2 Data Analysis and Discussion .................................................................... 38. 政 治 大. 4.3 Hypothesis Results ..................................................................................... 51. 立. ‧ 國. 學. V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................. 52 5.1 Theoretical Contribution ............................................................................ 52. ‧. 5.2 Managerial Implication .............................................................................. 53. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. 5.3 Limitation and Future Research .................................................................. 54. Ch. i n U. v. APPENDICES ......................................................................................................... 56. engchi. REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 70. v.

(6) LIST OF TABLES. Table. Page. 1 Brand choices available to the respondents ........................................................ 20. 政 治 大 3 Questions to pre-test source credibility............................................................... 25 立 2 Questionnaire items of brand attachment ............................................................ 24. ‧ 國. 學. 4 Questions to pre-test event severity .................................................................... 26 5 T-test results for manipulation pretest of source credibility and event severity ... 27. ‧. 6 T-test results for manipulation check of source credibility and event severity ..... 28. sit. y. Nat. 7 Questionnaire items of dependent variables........................................................ 30. n. al. er. io. 8 Reliability of each dependent variable ................................................................ 30. i n U. v. 9 Total number of survey responses by scenario case ............................................ 32. Ch. engchi. 10 Tests of between-Subjects effects by attitude change ....................................... 38 11 Tests of between-subjects effects by product evaluation change ....................... 39 12 Tests of between-subjects effects by perceived risk change .............................. 40 13 Average dependent variable score by level of attachment ................................. 41 14 Average dependent variable score by level of severity...................................... 44 15 Hypothesis results ............................................................................................ 51. vi.

(7) LIST OF FIGURES. Figure. Page. 1 Research process.................................................................................................. 5 2 Components of brand attachment ......................................................................... 7. 政 治 大. 3 Biased assimilation and brand attachment ............................................................ 8. 立. 4 Attitude changes by elaboration type in expert source ........................................ 11. ‧ 國. 學. 5 Fear context and events persuasiveness .............................................................. 13. ‧. 6 Hypothesis model .............................................................................................. 18 7 Survey design .................................................................................................... 21. sit. y. Nat. io. er. 8 Sample structure by gender ................................................................................ 33 9 Sample structure by age ..................................................................................... 34. al. n. v i n C h level ................................................................. 10 Sample structure by education 34 engchi U 11 Sample structure by cell phone brands ever used .............................................. 35 12 Sample structure by monthly cell phone usage frequency ................................. 35 13 Sample structure by monthly cell phone expense ............................................. 36 14 Sample structure by source of event gathering.................................................. 36 15 Estimated marginal mean of attitude by severity and source ............................. 45 16 Estimated marginal mean of evaluation by severity and source ........................ 46 17 Estimated marginal mean of severity by severity and source ............................ 47. vii.

(8) CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. 1.1. Background. 立. 政 治 大. People love good news events; unfortunately, we all hear about both good and bad. ‧ 國. 學. news events every day from all kinds of media sources. In fact, negative news events tend. ‧. to attract more attention than positive ones (Fiske, 1980), such that negative event. sit. y. Nat. impress people four times more than positive ones (Kroloff, 1988). People are more. io. al. er. impressed by negative events which provide more judgment and event value about other people or product than positive events (Herr, Kardes, & Kim, 1991; Klein, 1996;. n. v i n CFurthermore, Skowronski & Carlston, 1989). not only respond to the negative h e n g c people hi U publicity in a homogeneous manner (Marconi, 1997; Thompson, 1995), but consider negative event more diagnostic or informative than positive event (Maheswaran, 1990; Skowronski, 1987). Increasing media sources from traditional magazine to modern email enhance the transferability of tremendous amount of event we receive, but could be troublesome sometimes, especially when it is of unwelcomed negative nature. How should people decide the truthfulness of the negative events and their impacts on them, when there are.

(9) more and more news events coming from a variety of resources? It is probably not an easy task. Toffler (1970) even describes the situation of inhabitation of rational judgment to individuals resulting from a fast and irregularly changing situation as ―event overload‖. Perhaps the most well-known example in the recent years is the Toyota crisis (MacKenzie & Evans, 2010) that happened in the United States. Sudden acceleration and. 政 治 大. brake faults in Toyota’s cars caused several injuries and deaths, which jeopardized the. 立. brand’s reputation and is reflected by the declined sales. When consumers receive the. ‧ 國. 學. negative event about Toyota that has record of high car safety standards, how would their. ‧. attitude and evaluation to Toyota cars change, as high brand attached consumers or low brand attached consumers?. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Previous studies (Milberg, Park, & McCarthy, 1997; Romeo, 1991) that. v. investigated the negative brand effect in the context of negative feedback and consumers’. Ch. engchi. i n U. product evaluation suggest corporate to handle crisis accordingly (Johar, Birk, & Einwiller, 2010). However, there are rarely studies discussing the effects of consumers’ brand attachment and a negative event to consumers’ attitude and product evaluation changes. How would brand consumers, who establish relationship with the brand, called brand attachment that involves thoughts and feelings about the brand (Chaplin & John, 2005; Escalas, 2004) react to a negative event that attacks the relationship? A negative event about a brand has to be spread from a media source. When it is from a media source of high credibility, how would the presence of brand attachment 2.

(10) affect consumers’ attitude and product evaluation? What if it is from a low credible media source? Previous studies (Abdulla, Garrison, Salwen, Driscoll, & Casey, 2002; Greer, 2003) discuss the credibility of different sources and persuasion effects. Abdulla et al. (2002) studied how credibility of newspapers, television and online news on different dimensions, and Greer (2003) discuss how consumers evaluate the credibility of online. 政 治 大. news. However, there seems to be limited discussion about the relationship between. 立. source credibility and brand attachment.. ‧ 國. 學. A negative event can further be classified to high and low severity level in nature,. ‧. which triggers consumers’ fear levels. In the literature, fear has been found to be related to persuasiveness and attitude changes (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Hovland, 1953; Keller,. sit. y. Nat. io. er. 1996; Rogers, 1983). There seems to be limited discussions on how persuasiveness of a negative event be changed in the presence of consumers’ brand attachment.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In sum, since there are not many researches discussing negative brand effects from the perspective of consumer’s brand attachment and the nature of a negative event, it is important for this study to fill in the gap by connecting the theories and experimental studies to investigate how consumers’ attitude and product evaluation would be changed by their brand attachment, severity level and source credibility of a negative event.. 3.

(11) 1.2. Research Questions The investigation of the relationship between consumers’ brand attachment and a. negative event to consumers’ brand attitude and product evaluation is broke down to the following research questions: 1. How does consumers’ brand attachment affect changes in consumers’ brand attitude. 政 治 大. and product evaluation in the case of a negative event?. 立. 2. How does severity of a negative event affect changes in consumers’ brand attitude. ‧ 國. 學. and product evaluation?. 3. How does the source credibility of a negative event affect changes in consumers’. ‧. brand attitude and product evaluation?. y. Nat. sit. 4. How do the interactive effects between severity and source credibility of a negative. n. al. er. io. event affect changes in consumers’ brand attitude and product evaluation?. Ch. i n U. v. 5. How do the interactive effects between a consumer’s brand attachment and the. engchi. severity of a negative event affect changes in consumers’ brand attitude and product evaluation? 6. How do the interactive effects between a consumer’s brand attachment and the source credibility of a negative event affect changes in consumers’ brand attitude and product evaluation?. 4.

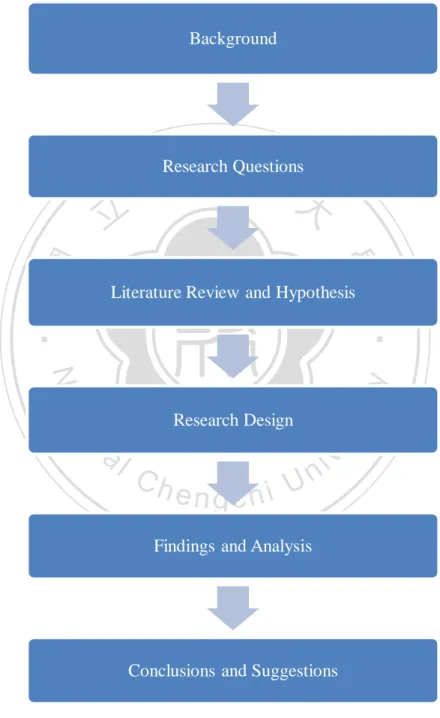

(12) 1.3 Research Process. Background. 立. Research Questions 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Literature Review and Hypothesis. ‧. n. Ch. engchi. er. io. al. sit. y. Nat. Research Design. i n U. v. Findings and Analysis. Conclusions and Suggestions. Figure 1: Research Process. Developed by this research.. 5.

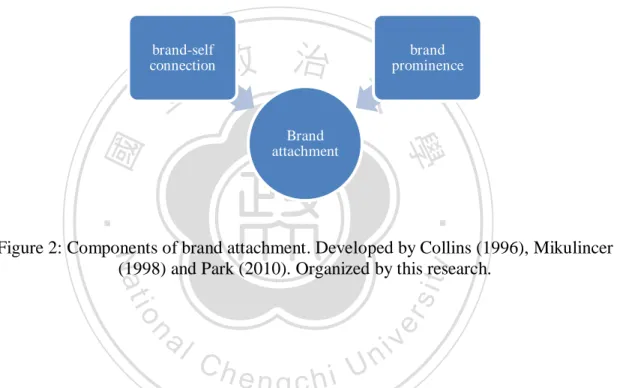

(13) CHAPTER II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS. 2.1 Brand Attachment Brand attachment is defined as cognitive and emotional connection between the. 政 治 大 connecting the brand with self involving thoughts and feelings about the brand, as well as 立 brand and self (Chaplin & John, 2005; Escalas, 2004), and is the strength of the bond. ‧ 國. 學. the brand’s relationship to the self. Brand attachment can be measured by two factors: brand-self connection and brand prominence.. ‧. Brand-self connection refers to a consumer who develops a sense of oneness with. Nat. sit. y. the brand by categorizing the brand as part of the self, establishing cognitive links, and. n. al. er. io. connecting to the brands that represent who self is or toward meaningful to them in light. i n U. v. of goals, personal concerns, or life projects (Park, MacInnis, Priester, Eisingerich, &. Ch. engchi. Lacobucci, 2010). Brand prominence refers to the notion that brand–self connections develop over time and through experience, which suggests that brand-related thoughts and feelings become part of one’s memory (Park, et al., 2010). Positive memories about the attachment object are more prominent for people who are highly attached to an attachment object than for people who show weak attachment (Collins, 1996; Mikulincer, 1998). As a result, when discussing brand attachment, it is necessary to take into the account of brand-self connection and prominence, and it is possible that consumers 6.

(14) possessing high brand-self connection but low prominence are less likely to engage in relationship-sustaining behaviors than those who possess high brand-self connection and high prominence. Thus, high attachment consumers may show more behavioral commitment in the form of brand loyalty and other behaviors in terms of high brand–self connection and high prominence (Park, et al., 2010).. brand-self connection. 立. brand 政 治 大 prominence. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Brand attachment. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Figure 2: Components of brand attachment. Developed by Collins (1996), Mikulincer (1998) and Park (2010). Organized by this research.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. High attachment individuals may demonstrate behavior of biased assimilation, which refers to tendency of viewing events similar to his/her point of view more reliable than non-similar events when asked about certain topics and pushed to express self opinion (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979), thereby proves that personal’s previous altitude is indeed an important convincing factor. Furthermore, when receiving a events that is against what an personal’s previous altitude, such point of view in the events may be threaten personal concepts to a events receiver who reacts by protection act or closed minded; in the contrary, if the point of the view in the events is similar to the personal 7.

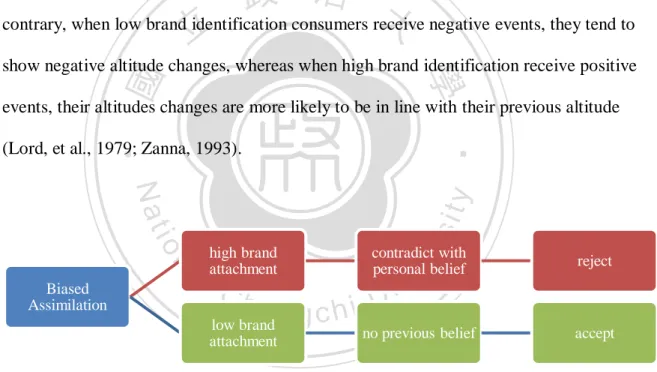

(15) previous altitude, events receiver tend to be open minded (Zanna, 1993). Thus, it is inferred that consumers who are familiar and in love with certain objects tend to pay attention to events similar to their altitude (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Extending from the high brand attachment concept, consumers tend to pay more attention to positive events related to their attached brand, which serves to strength their positive altitudes, at the same time seem to be more reliable than negative events (Feldman & Lynch, 1988), whereas negative events will less likely to affect the high. 政 治 大 contrary, when low brand identification consumers receive negative events, they tend to 立 attachment consumers (Feldman & Lynch, 1988; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). In the. ‧ 國. 學. show negative altitude changes, whereas when high brand identification receive positive events, their altitudes changes are more likely to be in line with their previous altitude. ‧. (Lord, et al., 1979; Zanna, 1993).. er. io. sit. y. Nat. n Biased Assimilation. high brand. contradict with. a l attachment personal v belief i n Ch i U e h n c g low brand. no previous belief. attachment. reject. accept. Figure 3: Biased assimilation and brand attachment. Theories developed by Park (2010), Petty (1986), and Feldman (1988), organized by this research.. 8.

(16) Theoretical Inference From the previous research, it can be inferred that consumers’ level of brand attachment will affect their altitudes when exposed to negative events about the brand. High attachment customers who share values with the brand and feel emotionally attached to it tend to deny negative events by showing less negative attitude changes, since the negative content in the events does not align with their previous belief about the brand; whereas customers who do not identify with the brand will examine negative. 政 治 大. events less carefully and tend to believe the accusation in the negative events, thus show. 立. more negative attitude changes.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Hypothesis 1: When exposed to a negative event, consumers with higher brand. sit. y. Nat. attachment will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk. io. n. al. er. changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. 2.2 Source Credibility. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. When an individual evaluates an event, source credibility is one of the factors they take into account and may influence their altitudes. Source credibility refers to a event source’s perceived ability or motivation to provide accurate and truthful event (Kelman & Hovland, 1953), and the source of a persuasive events is rated more credible by expertise (Rhine & Severance, 1970) or trustworthiness (Mills & Jellison, 1967). Source credibility is widely studied in the past by persuasion researchers, who. 9.

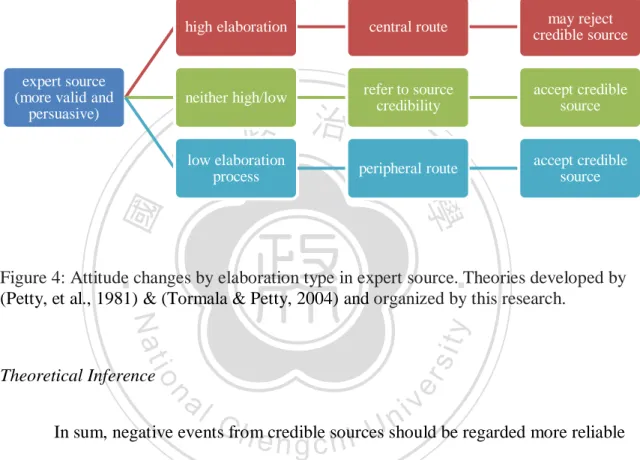

(17) find high credibility sources elicit more persuasion power and is perceived more trustworthy than low credibility sources (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Rhine, 1970), depending on situational or individual difference factors (Tormala & Petty, 2004). In general, the public is less likely to credit reputable sources with persuasive intent (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). Persuasion can be further evaluated in low and high elaboration conditions, which works differently. Under low elaboration conditions, expertise appears to invoke an ―experts are correct‖ heuristic (Petty, et al., 1981). On the other hand, under high. 政 治 大. elaboration conditions, source credibility influences persuasion by biasing individuals’. 立. nature of thoughts (Chaiken & Maheswaran, 1994), which affect the confidence. ‧ 國. 學. individuals have in their thoughts or cognitive responses (Briñol, Petty, & Tormala,. ‧. 2004), or thoughts to be evaluated as a piece of evidence relevant to the central merits of. sit. y. Nat. the issue under consideration (Kruglanski & Thompson, 1999). Only when elaboration is. io. er. not constrained to be high or low, source credibility can influence the amount of. al. processing that occurs (DeBono & Harnish, 1988; Heesacker, Petty, & Cacioppo, 1983).. n. v i n C h (high-effort scrutiny) As a result, central route processing e n g c h i U occurs when an individual is highly involved in the issue or events, whereas source credibility influences peripheral route (less effortful shortcut) when an individual is less involved (Petty, et al., 1981).. Furthermore, researchers found that people’s attitudes can actually change when they resist events from different sources (Tormala & Petty, 2004). The effects occurred when people try to resist attack events from an expert source, but not from an inexpert source (Tormala & Petty, 2004). People will become more certain of their attitudes after resisting persuasion from a high credibility source, but not after resisting persuasion from. 10.

(18) a low credibility source (Tormala & Petty, 2004). Consistent with this reasoning, events from high credibility sources have been shown to be perceived as more valid and persuasive than events from low credibility sources, even when the event in the events is objectively the same (Kaufman, Stasson, & Hart, 1999).. expert source (more valid and persuasive). high elaboration. central route. may reject credible source. neither high/low. refer to source credibility. accept credible source. 政 治 大 low elaboration peripheral route 立 process. accept credible source. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 4: Attitude changes by elaboration type in expert source. Theories developed by (Petty, et al., 1981) & (Tormala & Petty, 2004) and organized by this research.. er. io. sit. y. Nat Theoretical Inference. al. n. v i n In sum, negative eventsCfrom h ecredible h i Ushould be regarded more reliable n g c sources and more trustworthy as they represent certain level of expertise, comparing to the same content from less credible sources, with the assumption that people’s level of elaboration did not take into account. However, if the negative events try to attack what people believe, such as brand believes, even from credible sources, people will resist to be persuaded, and become more certain about their attitude, thus may show stronger resistance comparing to less credible sources.. 11.

(19) Hypothesis 2: When exposed to a negative event from a more credible source, consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 2.3 Event Severity If negative events attract more attention than positive events, then the question next is: what kind of contents would increase an event’s persuasiveness and change its. 政 治 大. recipients’ attitude? Take the ―Do not drive after drinking‖ ad as an example, deadly. 立. accident demonstration in the forms of pictures or descriptions is usually used as fear. ‧ 國. 學. appeals to persuade viewers not to drive after drinking alcohols.. ‧. In the literature, fear arousal has been found to affect persuasiveness,. sit. y. Nat. consequently attitude changes (Keller, 1996), which could be done by presenting event. io. er. about the harmful consequences of a behavior, or offering a solution comprised of. al. recommended actions that one might take to avoid the negative consequences (Hovland,. n. v i n C h acts may includeUavoiding the events, minimizing the 1953; Keller, 1996). The defensive engchi severity of the threat, selectively attending the events, discounting the threat, and denying its personal relevance(Eagly, 1993; Rogers, 1983). Furthermore, negative event may trigger individuals’ problem elaboration process, and is depended on low or high level of fear appeal and may affect individuals’ attitudinal changes (Keller, 1996). For high fear arousal, increasing the level of problem elaboration increases the extent to which the recipient will engage in defensive tendencies such as events avoidance and thus reduce events elaboration; in contrast, low fear arousal 12.

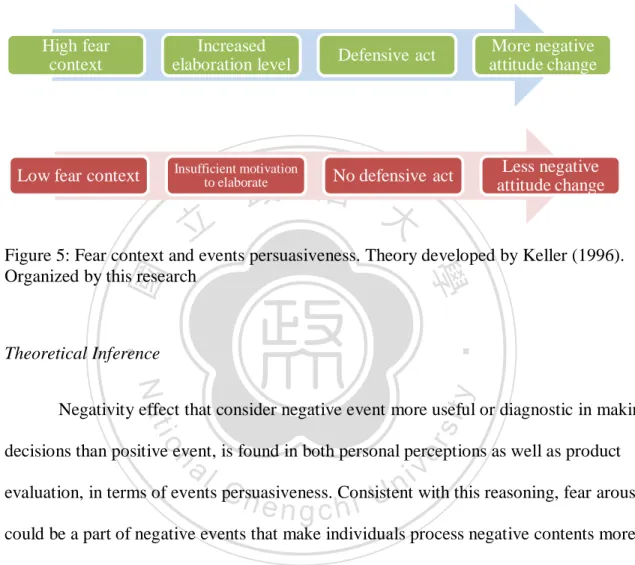

(20) interferes with persuasion because of insufficient motivation to elaborate on the events, which come to a conclusion that the level of fear arousal may be positively related to the propensity to elaborate (Keller, 1996).. High fear context. Increased elaboration level. Insufficient motivation to elaborate. Low fear context. 立. More negative attitude change. Defensive act. 政 治 大. No defensive act. Less negative attitude change. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 5: Fear context and events persuasiveness. Theory developed by Keller (1996). Organized by this research. Theoretical Inference. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Negativity effect that consider negative event more useful or diagnostic in making decisions than positive event, is found in both personal perceptions as well as product. al. n. v i n evaluation, in terms of events C persuasiveness. h e n g c hConsistent i U with this reasoning, fear arousal could be a part of negative events that make individuals process negative contents more carefully and systematically. Incorporate with fear appeal literature, it can be inferred that recipients who receive high fear appeal negative events will increase elaboration level, and take corresponding defensive act, thus demonstrate more negative attitude changes; while recipients who receive low fear context negative events tend to lack insufficient motivation to elaborate the negative content, thus will not take defensive act and show less negative attitude changes.. 13.

(21) Hypothesis 3: When exposed to a negative event with higher level of severity, consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to with lower level of severity. Theoretical Inference Although few studies has mentioned how different levels of fear appeal in. 政 治 大. negative events might interact with source credibility and affect consumers’ attitude, this. 立. study proposes that source credibility should dominate fear context regardless of the level. ‧ 國. 學. of negativity in the events by providing valuable reference to recipients of the negative events. The inference is that when consumers are threatened by negative events, they are. ‧. forced to elaborate the events carefully, the higher the severity level of the negative event,. y. Nat. io. sit. the more consumers need to elaborate. Credible source that represent expert knowledge. n. al. er. in this case will help consumers elaborating negative events. The more credible the. Ch. i n U. v. source, the more consumers will take it into account in the elaboration process. As a. engchi. result, in the high fear negative events situation, consumers will have more negative attitude changes when the events are from a credible source comparing to a less credible source. On the contrary, in the low fear negative events situation, since consumers are not motivated to elaborate, it does not matter which source the negative event is from, thus consumers will show no difference in negative attitude changes.. 14.

(22) Hypothesis 4: There are interactive effects between the level of severity and the source credibility of a negative event. 4 (a): When consumers receive a negative event with higher level of severity from a more credible source, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 4 (a): When consumers receive a negative event with lower level of severity from a more credible source, they will make no difference in negative attitude, product evaluation,. 政 治 大. and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Theoretical Inference. ‧. Brand assimilation theory suggests that high brand attached consumers tend to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. reject opinions against their believes to the brand; while low brand attached consumers will not. However, no previous literature has investigated how brand attachment interacts. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. with negative events of different fear levels and sources. This research proposes that,. engchi. when exposing to negative events, brand assimilation will work as a wall between consumers’ believes to the brand and negative events, and affect consumers’ attitude changes, such that higher brand attached consumers will show less negative attitude changes when receiving negative events. The logic is that, although negative events from a credible source provide persuasive information, in the existence of brand attachment, in order to for the high brand attached consumers to protect the relationship between self and the brand, they will tend to deny the negative content by demonstrating less negative attitude changes. Similarly, although negative events with higher severity level will 15.

(23) increase consumers’ elaboration level, in order to protect the relationship between the self and brand, high attached consumers will tend to deny the negative content by demonstrating less negative attitude changes. On the other hand, since low brand attached consumers do not have to take the risk of sacrificing the relationship with the brand, they will demonstrate more negative attitude changes if the negative events are from credible source or with higher severity level, as low brand attached consumers will be easily persuaded by expertise and. 政 治 大 will show more negative attitude changes by taking defensive acts if they receive 立. trustworthiness provided by a credible source. Similarly, low brand attached consumers. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. negative events with high severity level.. Hypothesis 5: There are interactive effects between the brand attachment level and the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. source credibility of a negative event.. al. 5 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event from a. n. v i n C h less negative attitude, more credible source, they will show e n g c h i U product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 5 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event from a more credible source, there will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 16.

(24) Hypothesis 6: There are interactive effects between the brand attachment level and the level of severity of a negative event. 6 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. 6 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived. 政 治 大. risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment.. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 17. i n U. v.

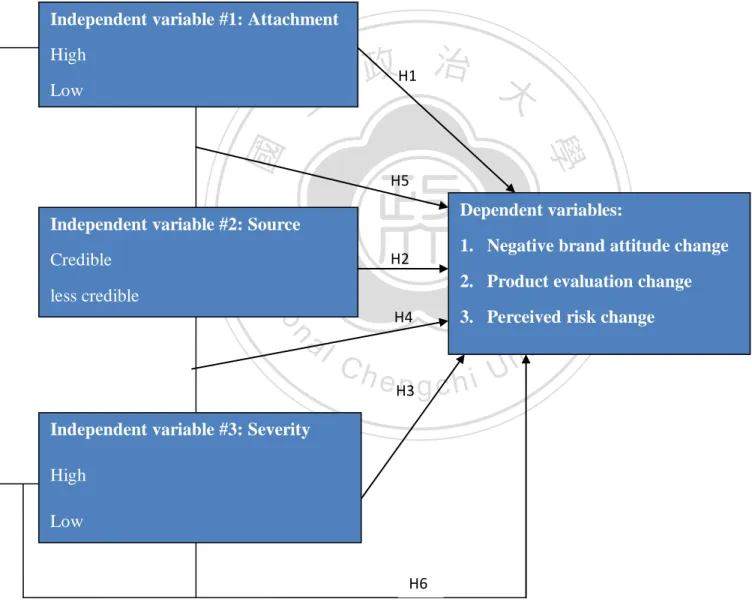

(25) 2.4 Hypothesis Model A hypothesis model is developed to include all hypotheses, so that readers could clearly observe relationship of main effect and interactive effect between indepndent variable (variables) and dependent variables.. Independent variable #1: Attachment High Low. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政H1 治 大 H5. ‧. Dependent variables:. Independent variable #2: Source. io. y. H4. 3. Perceived risk change. n. al. sit. 2. Product evaluation change. er. less credible. 1. Negative brand attitude change. H2. Nat. Credible. Ch. e H3 ngchi. i n U. Independent variable #3: Severity High Low. H6. Figure 6: Hypothesis model developed by this research. 18. v.

(26) CHAPTER III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY. 3.1 Research Design. 立. Product choice. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Since this research would like to focus on brand users to discover a potential. ‧. general rule, a product widely used rather than a single brand is required. As a result, the. Nat. sit. y. ideal product choice is the product that people use or carry with them often. The research. n. al. er. io. chooses cell phones that people carry with them as portable devices for communication and entertainment as the focal product.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Brand choices This research considers all available cell phone brands, and selected 19 brands, including best-selling brands, well-known brands, and the least known brands in the forms of both traditional feature phones and smart phones. The brand names are listed in alphabetical order in table 5.. 19.

(27) Table 1: Brand choices available to the respondents Acer. Alcatel. Apple. ASUS. BenQ. Blackberry. Docomo. GPlus. HTC. LG. Moto. Nokia. OKAWAP. Panasonic. Philip. Samsung. Sony Ericsson. Sharp. UTEC. 立. Target Respondents. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Since most of the young people are observed to carry at least one cell phone,. ‧. some even have two, and are frequent cell phone users, they are chosen as target respondents for this research. Young generation, including university students and young. y. Nat. n. er. io. al. sit. workers are the main target respondents.. Research Method. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. This research is conducted in experimental study, not only because it can reach the widest target respondents, but also because there is available survey websites that provide desired functions to fit the requirement of this research purpose. The survey was advertised on the media channels used most widely by the target audience, including BBS (electronic billboard) and Facebook (the social network), which link respondents to a preset up survey website. Pre-test has been carried out before the actual distribution of the research to ensure quality of the control variables. 20.

(28) stage 1. • Identify consumers with highest and lowest brand attachment. stage 2. • Participants read one of the four scenario cases:. stage 3. • Follow up measurements & other questions. 立. 政 治 大. Figure 7: Survey design. Developed by this research.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Stage 1: Identify consumers with high and low brand attachment. sit. y. Nat. io. er. A respondent is guided from BBS or Facebook to enter a survey website designed. al. v i n C sever events will affect research aims to understand how h e n g c h i U cell phone consumers’ brand n. particularly for this research. In the introduction page, the respondent is first told that this. attitude and purchasing intention. Then respondents will start stage 1. The respondent is randomly assigned to answer either ―what is you most attached cell phone brand‖ or ―what is your least attached cell phone‖, in which they need to self identify a cell phone brand within 19 brands. Specifically, 19 brands are shown in different random order for each participant to avoid blind selection.. 21.

(29) Stage 2: Respondents read one of the four scenario cases containing source and severity Following by self identified brand with highest or lowest attachment, respondents is randomly given one of the four scenario cases: (1) less credible source and high severity, (2) less credible source and low severity, (3) credible source and high severity, as well as (4) credible source and low severity. Credible source refers to magazine, less. 政 治 大. credible source refers to forwarded email; while high severity refers to battery explosion. 立. event, and low severity refers to slow events texting speed.. ‧ 國. 學. The brand that the respondent chooses in stage 1 is embedded in each scenario. ‧. case at stage 2. In other words, each scenario is customized to make the survey as. sit. y. Nat. realistic as possible for respondents; also, to prevent the respondent from noticing the. al. n. event.. er. io. control variables, the scenario cases are designed to incorporate with other irrelevant. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The introduction in the scenario cases first ask the respondent to pretend as someone who pay attention to 3C news and trend, and happens to walk into the bookstore to read a magazine or receive forwarded email from friends who does not have relevant IT background, then continues to read the article content. The article content of magazine source is presented in the way similar to magazine layout with journalist’s name, title, and written style. On the other hand, forwarded email is composed using the same title and same content as magazine, but in e-mail format and deliberately poorer written style.. 22.

(30) Stage 3: Follow up measurement Measurement regarding consumers’ attitude changes (attitude, evaluation and severity), brand attachment, and consumer commitment are described in the previous part of this research.. 政 治 大 independent variables check, and individual background, and are explained in the 立. Other questions include in stage 3 are article reliability of the scenario cases,. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. following parts.. sit. y. Nat. 3.2 Variables Manipulation and Measurement. n. al. er. io. This section will discuss manipulation (measurement) of independent variables —. i n U. v. brand attachment, event severity and source credibility, and measurements of dependent. Ch. engchi. variables—negative brand attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk changes.. Independent Variables Brand attachment: manipulation and measurement Brand attachment is self identified by respondents in stage 1, through randomly assigning to select one of respondents’ highest/lowest attached brand from 19 available brands, then measured with a set of questions in stage 3 adopted from the survey 23.

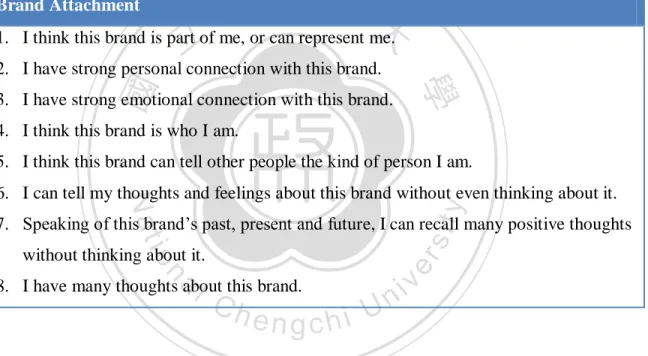

(31) developed by Park et al. (2010). Refer to table 2. Respondents are asked to rate in 5point-scale, in which the 1 represent least agree with the negative description about the brand, and 5 represent most agree with the description about the brand.. Table 2: Questionnaire items of brand attachment. Developed by Park et al. (2010) and adopted by this research. Brand Attachment 1.. 政 治 大 I think this brand is part of me, or can represent me. 立. 2. I have strong personal connection with this brand.. ‧ 國. 學. 3. I have strong emotional connection with this brand. 4. I think this brand is who I am.. ‧. 5. I think this brand can tell other people the kind of person I am.. y. Nat. 6. I can tell my thoughts and feelings about this brand without even thinking about it.. io. sit. 7. Speaking of this brand’s past, present and future, I can recall many positive thoughts. n. al. er. without thinking about it. 8. I have many thoughts about this brand.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source credibility and event severity: manipulation pretest Since source credibility and event severity will both be manipulated in scenario cases, it is important to conduct a pretest in order to make sure quality of independent variables. A group of 40 respondents are asked to rate 9 descriptions about sources credibility and 8 events with various severity levels by using 7-point Likert scale, in which 1 represents least credible/least severe, and 7 represents very credible/ very severity. The descriptions of source credibility and event severity in the pre-tests are 24.

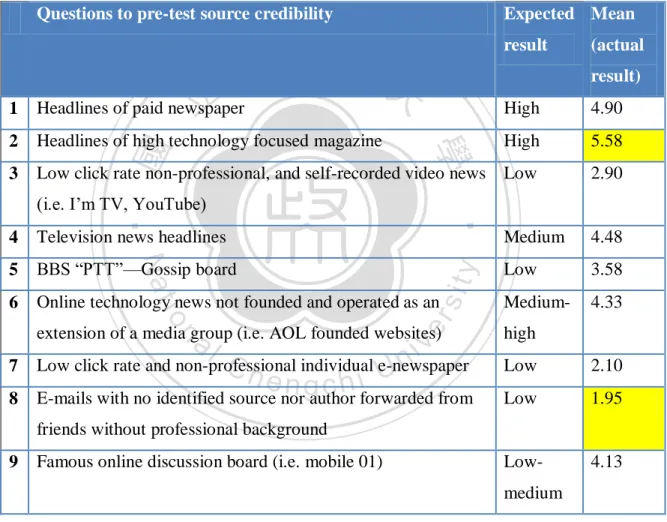

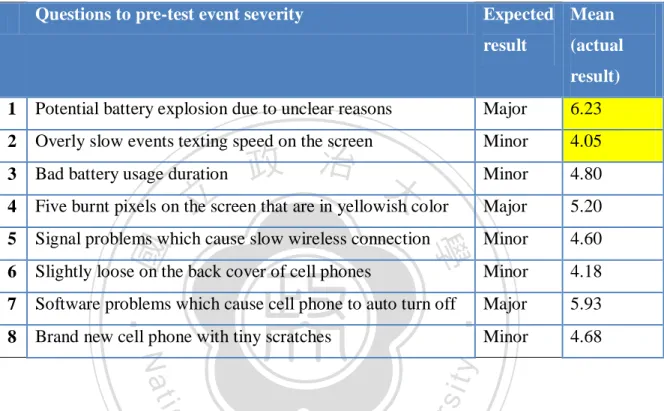

(32) developed by this research and distributed to respondents in Chinese, then translated to English as in table 3 and table 4. Table 3: Questions to pre-test source credibility. Developed by this research Questions to pre-test source credibility. 立. Expected Mean result. 政 治 大. High. 4.90. Headlines of high technology focused magazine. High. 5.58. 3. Low click rate non-professional, and self-recorded video news Low. 2.90. Television news headlines. 5. BBS ―PTT‖—Gossip board. 6. Online technology news not founded and operated as an. 4.48. Low. 3.58. Medium-. 4.33. er. io. Medium. sit. Nat. 4. ‧. (i.e. I’m TV, YouTube). y. 2. ‧ 國. Headlines of paid newspaper. result). 學. 1. al. extension of a media group (i.e. AOL founded websites). v i n C h individual e-newspaper Low click rate and non-professional engchi U n. 7 8. (actual. E-mails with no identified source nor author forwarded from. high Low. 2.10. Low. 1.95. Low-. 4.13. friends without professional background 9. Famous online discussion board (i.e. mobile 01). medium. 25.

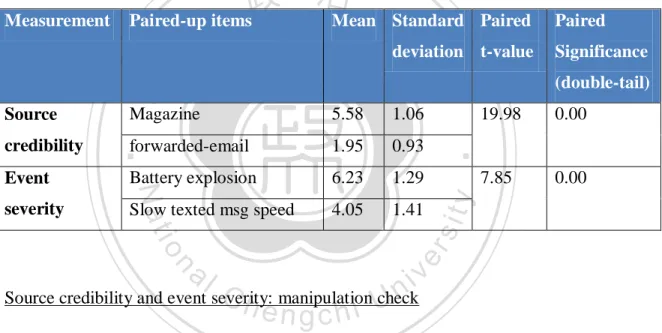

(33) Table 4: Questions to pre-test event severity. Developed by this research Questions to pre-test event severity. Expected Mean result. (actual result). 1. Potential battery explosion due to unclear reasons. Major. 6.23. 2. Overly slow events texting speed on the screen. Minor. 4.05. 3. Bad battery usage duration. Minor. 4.80. 4. Five burnt pixels on the screen that are in yellowish color. Major. 5.20. 5. Signal problems which cause slow wireless connection. Minor. 4.60. 6. Slightly loose on the back cover of cell phones. Minor. 4.18. 7. Software problems which cause cell phone to auto turn off. Major. 5.93. 8. Brand new cell phone with tiny scratches. Minor. 4.68. 學. Nat. er. io. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. After collecting the pre-test results, it is observed that in terms of source credibility,. al. n. v i n ―Headlines of high technologyC focused isUrated the most credible with a mean h e nmagazine‖ i h gc of 5.58 out of 7-point-scale, while ―E-mails with no identified source nor author. forwarded from friends without professional background‖ is rated the least credible with a mean of 1.95. In addition, in terms of event severity, ―Potential battery explosion due to unclear reasons‖ is rated the most severe with a mean of 6.23, while ―Overly slow events texting speed on the screen‖ is rated the least severe with a mean of 4.05.. 26.

(34) To make sure the results’ credibility and severity measurement are truly different, paired sample T-test has been conducted using 5% significance. It is observed that the two items in both source credibility and event severity are significantly different.. 治 政 Paired-up items Mean 大 Standard 立 deviation. Table 5: T-test results for manipulation pretest of source credibility and event severity. t-value. Significance. forwarded-email. 1.95. 0.93. Battery explosion. 6.23. 1.29. Slow texted msg speed. 4.05. 1.41. 19.98. 7.85. 0.00. 0.00. y. 1.06. io. sit. 5.58. (double-tail). er. severity. Magazine. Nat. Event. Paired. ‧. credibility. Paired. 學. Source. ‧ 國. Measurement. n. al. ni C h manipulation U Source credibility and event severity: check engchi. v. To ensure successful manipulation of source credibility and event severity, the survey respondents are asked to rate how credible the magazine and forwarded-email source are, as well as how high is the severity of potential battery explosion and events texting speed in 5-point-scale. Using 5% significance, it is observed that independent control variables are significantly different from the paired T-test blow indicated in table 6. Both results for source and event severity are pretty close to the pre-test results. Magazine is a more credible source, whereas forwarded email is a less credible source.. 27.

(35) Potential battery explosion is a high severity event, whereas slow events texting speed is a moderate severity event.. Table 6: T-test results for manipulation check of source credibility and event severity. 治 Standard 政 Mean 大 deviation. Measurement Paired-up items. 3.51. 0.81. Forwarded-email. 2.07. 0.87. Battery explosion. 4.33. 1.03. Events texting speed. 3.67. 0.94. 18.12. 10.31. 0.00. 0.00. io. sit. y. Nat. severity. Significance. ‧. Event. t-value. al. er. credibility. Magazine. 學. Source. Paired. (double-tail). ‧ 國. 立. Paired. n. Dependent Variables Measurement. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Respondents need to answer, after reading the scenario cases with their selected brands, how their attitude have changed by reading extremely negative description and give response from least agree to most agree. 1. Attitude Change Respondents are asked to read 6 negative statements relating to attitude toward the product, and rate their agreed level from 1-5, in which 1 represents least agree and 5 represents most agree. The statements are listed in table 7.. 28.

(36) 2. Product Evaluation Change Respondents are asked to read 3 negative statements relating to evaluation toward the product, and rate their agreed level from 1-5, in which 1 represents least agree and 5 represents most agree. The statements are listed in table 7. 3. Perceived Risk Change. 立. 政 治 大. Respondents are asked to read 3 negative statements relating to perceived risk. ‧ 國. 學. changes toward the product, and rate their agreed level from 1-5, in which 1 represents least agree and 5 represents most agree. The statements are listed in table 7.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 29. i n U. v.

(37) Table 7: Questionnaire items of dependent variables. Developed by this research Set. Questions. Attitude. 1. In general, I think that products of this cell phone brand have become. change. very unuseful. 2. In general, my overall perception about this cell phone brand has become very bad.. 政 治 大 This cell phone brand has become very unattractive to me. 立 This cell phone brand has become very disgusting to me.. 3. In general, I think choosing this cell phone brand is very stupid. 4.. 學. ‧ 國. 5.. 6. My feeling toward this cell phone brand has become very awful.. 2. This cell phone brand has become very disgusting to me. 3. My feeling toward this cell phone brand has become very awful.. Nat. change. ‧. evaluation. 1. This cell phone brand has become very unattractive to me.. y. Product. risk change. 2. I think using this cell phone brand has incurred very high severity.. n. al. er. sit. 1. I think it has become very dangerous to use this cell phone brand.. io. Perceived. i n U. v. 3. I have become very doubtful for trustworthiness of this cell phone brand.. Ch. engchi. Table 8: Reliability of each dependent variable Dependent variable Number of items. Cronbach α. Reliability (α>0.7). Attitude. 6. 0.959. valid. Evaluation. 3. 0.947. valid. Severity. 3. 0.922. valid. 30.

(38) Individual Background Information Background information of each respondent is asked in the final section of the survey, including gender, age, education level, cell phone usage frequency, cell phone brands ever used, expenditure on cell phone, and source of event are asked in the last part of the survey.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 3.3 Sample Screening. It is found that some respondents did not have highest/lowest brand attachment. ‧. when asked to identify a highest/lowest attached brand. Perhaps they are not as high/low. y. Nat. io. sit. attached as they think they are to the brand they choose. As a result, data screening is. n. al. er. applied to screen the unqualified responses. The criteria is that if a respondent is asked to. Ch. i n U. v. self identify a high attached brand in stage one, then he/she must have an average score. engchi. equal or great than 3 in the measurement of brand attachment in stage 3; whereas low brand attached respondents must have an average score less than 3. If respondents’ answers did not meet the qualification, their responses will be excluded from the sample. In total, 349 complete surveys have been collected, in which 189 valid sample surveys that meet the purpose of this research, which accounts for 54% of the total collected surveys.. 31.

(39) Table 9: Total number of survey responses by scenario case Scenario. high attachment. high attachment. high attachment. high attachment. Total high. case. × fw-mail. × fw-mail. × magazine. × magazine. attachment. × high severity. × moderate. × high severity. × moderate. cases. severity Total #. severity. 24. 22. 20. 34. Scenario. low attachment. low attachment. low attachment. low attachment. Total low. case. × fw-mail. × fw-mail. × magazine. attachment. × moderate. cases. ‧ 國 27. 11. severity. 學. 27. ‧. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Total #. × magazine 政 治 大 × high severity × moderate × high severity 立severity. Ch. engchi. 32. i n U. 100. v. 24. 89.

(40) CHAPTER IV. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS. 4.1 Data Summary. Sample Structure by Gender. 學. Nat. n. al. sit. 46%. er. io. 54%. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. Ch. engchi. Figure 8: Sample structure by gender. 33. i n U. v. Male Female.

(41) Sample Structure by Age. 7% 4%. < 20 20-30. 立. 政 治 大 89%. 31-40. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Figure 9: Sample structure by age. io. er. n. al. sit. y. Nat Sample Structure by Education Level. C 4% h. engchi. i n U. v. 33% < College College >=Master 63%. Figure 10: Sample structure by education level. 34.

(42) Sample Structure Number of Brands Ever Used 2%. 31%. 1-3 brands 4-6 brands 7-9 brands 67%. 政 治 大. 立. Figure 11: Sample structure by cell phone brands ever used. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. 6%. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Sample Structure by Monthly Cell phone Usage Frequency. 43%. Ch. engchi 24%. i n U. v. < 1 hour 1-3 hours. 3-5 hours 5-7 hours > 5 hours. 15% 12%. Figure 12: Sample structure by monthly cell phone usage frequency. 35.

(43) Sample Structure by Monthly Cell Phone Expense 3%. 30%. < $200 $ 201-600 $ 601-1000. 67%. 立. 政 治 大. Figure 13: Sample structure by monthly cell phone expense. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Sample Structure by Respondents’ Frequent Source of Information Gathering. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat 14%. 15%. Ch. 32%. engchi. iv The Internet n U Television. Friends and Relatives Newspaper Magazine 18% 21%. Figure 14: Sample structure by source of event gathering (More than one answer from a participant may be possible). 36.

(44) Data Description Demographic Structure From the demographic structure, it is found that almost equal percentage of female and male sample respondents answered this survey, while almost 90% of the respondents are aged 20-30, which fit the target audience in this study. Over 90% of the respondents have college or above degree. Cell phone Usage Experience. 政 治 大 From the cell phone usage experience figure, it is found that about 70% of 立. ‧ 國. 學. respondents have used 1-3 cell phone brands, while about 40% of respondents use the cell phone for over 5 hours per month, but about 70% spent only $200 per month.. ‧. Source of Event. sit. y. Nat. io. al. er. From respondents’ frequent source of event gathering the event gather source, it is. v. n. found that the most frequent source used by respondents is the internet, followed by. Ch. engchi. i n U. television, friends and relatives, newspaper, and magazine. It is not clear that why magazine as the least frequent source used is rated the most reliable source in comparison with other sources when doing pretest and posttest for this study.. 37.

(45) 4.2 Data Analysis and Discussion This part will present tables of tests of between-subjects effects by individual dependent variable, then analyze results and discuss why or why not each hypothesis is supported and not supported hypothesis along with appropriate supporting graphs of estimated marginal means. Highlighted rows in tables of tests of between-subjects effects are those with significance over 0.1 and worth to be discussed.. 政 治 大. Table 10: Tests of between-subjects effects by attitude change. Type III Sum of. 學. Mean Square. F. Sig.. Corrected Model. 90.215a. 7. 12.888. 17.346. .000. Intercept. 1469.317. 1. 1469.317. 75.456. 1. 75.456. .694. 1. .694. .733. 1. .733. 1. .041. Source. Attachment * Severity. .000. 101.554. .000. y. a l.041 Ch .989. n. Attachment * Source. io. Severity. 1977.517. sit. Attachment. ‧. df. Nat. Squares. er. Source. ‧ 國. 立. v ni. 1 .989 e n g1 c h i U2.639. Source * Severity. 2.639. Attachment * Source *. .343. 1. .343. Error. 134.485. 181. .743. Total. 1789.636. 189. Corrected Total. 224.700. 188. Severity. 38. .934. .335. .987. .322. .055. .815. 1.331. .250. 3.552. .061. .462. .497.

(46) Table 11: tests of between-subjects effects by product evaluation change. Type III Sum of Source. Squares. df. Mean Square. F. Sig.. Corrected Model. 105.248a. 7. 15.035. 17.061. .000. Intercept. 1541.549. 1. 1541.549. 1749.257. .000. Attachment. 81.019. 1. 81.019. 91.936. .000. Source. .074. 1. .074. .083. .773. Severity. 3.383. 1. 3.383. 3.839. .052. Attachment * Source. .032. 1. .032. .037. .849. Attachment * Severity. .000. 1. .000. .000. .989. Source * Severity. 5.450. 1. 5.450. 6.184. .014. 1. .025. .028. .868. 159.508. 181. .881. 1896.456. 189. 264.756. 188. 立. Attachment * Source *. .025. ‧. Corrected Total. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Total. 學. Error. ‧ 國. Severity. 政 治 大. Ch. engchi. 39. i n U. v.

(47) Table 12: Tests of between-subjects effects by perceived risk change. Type III Sum of Source. Squares. df. Mean Square. F. Sig.. 95.344a. 7. 13.621. 14.804. .000. 1496.590. 1. 1496.590. 1626.641. .000. 54.488. 1. 54.488. 59.223. .000. Source. 1.302. 1. 1.302. 1.416. .236. Severity. 15.347. 1. 15.347. 16.680. .000. Corrected Model Intercept Attachment. Attachment * Source Attachment * Severity. 立. Source * Severity. 政 治 大 .114. 1. .114. .124. .725. .745. 1. .745. .809. .370. 3.165. 1. 3.165. 3.440. .065. .003. 1. .003. .004. .952. 166.529. 181. 1887.468. 189. 261.873. 188. Attachment * Source *. Corrected Total. .920. ‧. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Total. ‧ 國. Error. 學. Severity. Ch. engchi. 40. i n U. v.

(48) Hypotheses results Hypothesis 1: Main effect of brand attachment to all dependent variables ▪. Statement: When exposed to a negative event, consumers with higher brand attachment will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. ▪. Result: supported. ▪. Discussion:. 政 治 大. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Table 13: Average dependent variable score by level of attachment. ‧. Average negative attitude change. 2.24. 3.59. Average negative product evaluation change. 2.26. Average negative perceived risk change. 2.34. n. Ch. 3.53. engchi U. sit er. io. al. Average brand attachment. y. Low attachment. Nat. High attachment. v ni. 3.69 3.59 2.07. From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that the brand attachment as an independent variable has significant effect to consumers’ attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk changes. Furthermore, in table 13, it is found that high brand attached consumers tend to show less negative changes in attitude, product evaluation and lower perceived risk comparing to low brand attached consumers.. 41.

(49) Consistent with the literature findings, that consumers tend to pay more attention to positive events related to their attached brand (Feldman & Lynch, 1988) to maintain altitude change in line with their previous perception about the brand (Lord, et al., 1979; Zanna, 1993), this research finds out that high brand attachment customers tend to show less negative attitude, product evaluation and severity changes when exposed to a negative event, comparing to low brand attached group. In other words, brand attachment has a negative relationship with customers’ overall attitude changes when consumers are exposed to negative events.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. ▪. 學. Hypothesis 2: Main effect of event source to all dependent variables Statement: When exposed to a negative event from a more credible source,. ‧. consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk. y. Nat. er. al. Result: not supported. n. ▪. io. ▪. Discussion:. sit. changes comparing to from a less credible source. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that the event source as an independent variable has no significant effect to consumers’ attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk changes. According to the literature, source credibility will affect the level of an event’s persuasiveness, such that high credibility sources elicit more persuasion than low credibility sources. As a result, magazine source considered as a credible source with. 42.

(50) experts’ knowledge by the respondents should have better persuasion power than forwarded email source as a less credible source. However, credibility did not affect consumers’ attitude after analyzing the survey data. Possible reasons might be that source credibility should be considered with consumers’ elaboration process in order to make the persuasion of the credible source take effect. Heesacker et al. (1983) and DeBono et al. (1988) indicate that, source credibility works as a reference to consumers whose elaboration is neither high nor low,. 政 治 大 perspective of source but not take into account of their elaboration levels, source is 立. or is low. Since in hypothesis 2, consumers’ responses are analyzed purely from the. ‧ 國. 學. therefore not initiated by consumers as a credible reference. As a result, one cannot tell whether the source credibility would affect consumers’ negative attitude change, negative. ‧. product evaluation and perceived risk change.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Hypothesis 3: Main effect of event severity to all dependent variables ▪. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Statement: When exposed to a negative event with higher level of severity, consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to with lower level of severity. ▪. Result: mainly supported. 43.

(51) ▪. Discussion: From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that the severity level as an independent. variable has significant effect to consumers’ product evaluation and perceived risk changes, but not attitude change. Furthermore, in table 14, it is found that consumers who are exposed to high severity negative events tend to show higher average negative product evaluation change and higher average negative perceived risk change. In the literature, fear contained in the negative event can bring up individual’s. 政 治 大. level of problem elaboration, depending on the level of fear appeal. A low-fear appeal. 立. event reduces individual’s level of problem elaboration and high-fear appeal increases. 學. ‧ 國. individual’s level of problem elaboration (Keller & Block, 1996). The findings in the research support the literature, and imply that increasing problem elaboration process. ‧. would affect consumers’ product evaluation and perceived risk, but not brand attitude.. y. Nat. io. sit. Perhaps the fear level is more related and determined by severity level, whereas brand. n. al. er. attitude is more affected by consumers’ perception about the brand and cannot by simply. Ch. shaken by a single negative event.. engchi. i n U. v. Table 14: Average dependent variable score by level of severity High severity. Low severity. Average negative attitude change. 3.07. 2.67. Average negative product evaluation change. 3.2. 2.66. Average negative perceived risk change. 3.31. 2.53. 44.

(52) Hypothesis 4: Interactive effect between event severity and event source ▪. Statement: 4 (a): When consumers receive a negative event with higher level of severity from a more credible source, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 4 (a): When consumers receive a negative event with lower level of severity from a more credible source, they will make no difference in negative attitude, product. 政 治 大. evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 立. ▪. Discussion:. ‧. ‧ 國. Result: supported. 學. ▪. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. high severity. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. low severity. less credible. more credible. Figure 15: Estimated marginal mean of attitude by severity and source 45.

(53) From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that interactive effect between event severity and event source does exist. Graphs of estimated marginal mean of each dependent variable are provided to enable more analysis. Figure 15 that provide interactive effect between event’s severity and source to attitude change show that the p-value of the two points along the vertical axis of less credible source is more than 0.25, and imply that regardless of high or low severity, consumers would behave similarly when the piece of event is from a less credible source.. 政 治 大 credible source, high severity involved event would trigger more attitude change to 立. Furthermore, figure 15 show that when respondents receive a negative event from a more. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. customers comparing to low severity event.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. high severity. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. low severity. more credible. less credible. Figure 16: Estimated marginal mean of evaluation by severity and source 46.

(54) Figure 16 that provide interactive effect between severity and source to attitude product evaluation change, show the p-value of the two points along the vertical axis of less credible source is between 0.2-0.25, and imply that regardless of high or low severity level, consumers would behave similarly when the piece of event is from a less credible source. Furthermore, figure 16 show that when respondents receive a negative event from a more credible source, high severity involved event would trigger more product evaluation change to customers comparing to a low severity event.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. high severity. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. low severity. less credible. more credible. Figure 17: Estimated marginal mean of severity by severity and source. Figure 17 provide interactive effect between severity and source to perceived risk change show the p-value of the two points along the low severity involved line on less 47.

(55) credible source and more credible source is found to be greater than 0.25, which imply that consumers behave similarly when receiving low severity involved event. Furthermore, figure 17 show that when respondents receive a high severity involved event, a more credible source would trigger more perceived risk change comparing to a less credible source. In sum, it can be inferred from figure 15, 16, and 17, when consumers receive a high severity involved negative event, they tend give more negative rating in favorability,. 政 治 大 as the source of the events moves from a less credible source to a more credible source. 立. attitude, evaluation and severity dimensions, and such negative rating becomes stronger. ‧ 國. 學. On the other hand, consumers who receive a lower severity involved events tend to demonstrate less negative favorability, attitude. Also, they tend to behave similarly. ‧. regardless of the source credibility.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Hypothesis 5: Interactive effect between brand attachment and event source ▪. Statement:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 5 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event from a more credible source, they will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 5 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event from a more credible source, there will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source. 48.

(56) ▪. Result: not supported. ▪. Discussion: From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that the brand attachment has no. interactive effect with event source to consumers’ attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk changes. As a result, hypothesis 5 is not supported. According to biased assimilation theory, brands consumers’ commitment will affect how they perceive negative event about their brands, so it is originally assumed. 政 治 大. that high committed consumers tend to reject an event that threatens one’s belief to a. 立. higher degree, whereas low committed consumers tend to accept negative events.. ‧ 國. 學. However, biased assimilation only works when singly speaking about consumers. ‧. brand attachments’ effects to consumers’ brand attitude, product evaluation and. Nat. sit. y. perceived risk changes, but not when it interacts with events source. Perhaps, consumers. al. n. versa holds true too.. er. io. did not consider attachment to the brand with the sources of negative events, and vice. Ch. engchi. 49. i n U. v.

(57) Hypothesis 6: Interactive effect between brand attachment and event severity ▪. Statement: 6 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. 6 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation,. 政 治 大. and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment.. 立. Result: not supported. ▪. Discussion:. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. ▪. From the table 10, 11 and 12, it is found that the brand attachment has no. y. Nat. er. io. perceived risk changes.. sit. interactive effect with event source to consumers’ attitude, product evaluation and. al. n. v i n C h attachment isUfound to play a role when singly Similar to hypothesis 5, brand engchi. speaking to consumers’ brand attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk changes, but not when brand attachment interacts with event source. Perhaps consumers regard brand attachment separately with negative event severity, thus brand assimilation did not seem to work as a protection wall between consumers and the negative event.. 50.

(58) 4.3 Hypothesis Result # 1. Hypothesis When exposed to a negative event, consumers with higher brand attachment will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment 2 When exposed to a negative event from a more credible source, consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 3 When exposed to a negative event with higher level of severity, consumers will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to with lower level of severity 4 4 (a): When consumers receive a negative event with higher level of severity from a more credible source, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 4 (b): When consumers receive a negative event with lower level of severity from a more credible source, they will make no difference in negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 5 5 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event from a more credible source, they will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 5 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event from a more credible source, there will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to from a less credible source 6 6 (a): When consumers with higher brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show less negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. 6 (b): When consumers with lower brand attachment receive a negative event with higher level of severity, they will show more negative attitude, product evaluation, and perceived risk changes comparing to consumers with lower brand attachment. Table 15: Hypothesis results. 立. 政 治 大. Result Support. Not support Mainly support Support. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Not support. Ch. engchi. 51. i n U. v. Not support.

(59) CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION. 5.1 Theoretical Contribution This research follows footsteps of the previous research and provides some new. 政 治 大 proves that brand attachment represents a kind of relationship established between the 立 insights. Consistent with the Lord (1979) and Zanna (1993)’s findings, this research. ‧ 國. 學. consumers and brands, will affect consumers’ brand attitude, product evaluation and perceived risk in the case of negative events.. ‧. Also, following Keller’s (1996) findings, the research finds out that a higher fear. y. Nat. io. sit. level involved negative event will increase consumers’ elaboration motivation and will. n. al. er. affect consumers’ brand attitude, whereas a lower fear level involved negative event will not make such impacts.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In addition, previous research has not put together events source with the severity level involved in a negative event, and this gap has been fulfilled by this research. This research reveals that source serves as a key reference for consumers to elaborate the negative content of a negative event. Although a more credible source is proven be perceived to be more valid and persuasive than a less credible source as described in Kaufman’s (1999) findings, this research discovers that credible source will only be referred as expert knowledge in the case of high severe negative event, but not low severe. 52.

(60) negative event. Furthermore, the interactive effect of the severity level and source credibility of a negative event will only affect consumers’ attitude to the brand and product evaluation, but not perceived risk. Perceived risk has more to do with fear levels that trigger consumers’ elaboration motivation. Lastly, previous research has not mentioned how consumers’ brand attachment will interact with negative events about brands, this research discovers that brand attachment does not interact with negative event from either the perspective of event. 政 治 大 attachment does not replace knowledge provided by events source nor the fear level 立. source or event severity, which suggests that brand assimilation resulting from brand. ‧ 國. 學. contained in a negative event. In other words, consumers tend to consider brand attachment and the negative event separately.. ‧ sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 5.2 Managerial implications. i n U. v. Since products today are made globally and sold globally, brand power is. Ch. engchi. considered important to the companies to retain loyal consumers and create more sales. At the same time, it is increasingly harder to prevent hurting negative events to the brands, especially with the convenient technology that creates or transmits negative events in timely manner. This research helps brand managers devise possible strategies in response to negative events with different severity levels and sources. When a brand is attacked by negative events, brand managers should take necessary responses based on the negative events’ severity level and transmission sources,. 53.

(61) but not to rely on customers’ brand loyalty because consumers’ brand attachment is not enough to help them deal with crisis. If negative events involve low severity and come from a less credible source, or low severity from a more credible source, brand managers can simply ignore the attack since consumers know that the accusation in the negative events is not true. If negative events involve high severity and come from a less credible source, managers should try to lower the severity level in the events, such as explaining the situation and take. 政 治 大 credible source, managers should not only explain the situation in public, but actively 立. corresponding responses. If negative events involve high severity and come from a more. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. response to the crisis to sustain consumers’ trust.. sit. y. Nat. 5.3 Limitation and Future Research. n. al. er. io. Every research has its own limitation; this study is not an exception. One of the. i n U. v. limitations is the control of brand attachment in this survey design. Since this research. Ch. engchi. adopts online surveys in order to include a huge number of cell phone brands with random assignment of brand attachment levels and scenario cases, it is hard to measure respondents’ actual brand attachment levels and to drive out unqualified responses that resulted with fewer survey responses. Future research can work on making a better control on the brand attachment measurement, by either set up interactive website or preselection process to ensure quality response in terms of brand attachment levels.. 54.

(62) Also, future research can try to provide cross-product comparison, by replicating this research using other products that may provide different functions and benefits to consumers, and see if there is any difference. In addition, since brand attachment is not so well controlled in this research, brand commitment is not used for analysis in this research. Future research that has good control on brand attachment may further analyze consumers’ brand commitment types and study consumers’ behaviors accordingly.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 55. i n U. v.

數據

+7

相關文件

MR CLEAN: A Randomized Trial of Intra-arterial Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke. • Multicenter Randomized Clinical trial of Endovascular treatment for Acute ischemic stroke in

● 使用多重準則(例如清晰度、準確度、有效性、是否及

危機事件 後果 可預測性 持續性 震撼程度 估計危機 影響程度 一對小四及小. 二的兄妹,居 於學校同邨的

評估資訊和 資訊提供者 的權威、 公 信力及可靠性 素養範疇 5:. 提取和整理 資訊以產生 新知識

浪漫色彩 兩性相處變得避忌,影響正常友誼發展

因此在表 5-4 評估次項目中,統計結果顯示政治穩定度、房產政 策、官僚政治以及景氣是接受度最高的,可以顯示政局安定以及當局

對材料採購、施工及行銷階段的成敗影響很大,亦即從進料一直到成

Thus, the purpose of this study is to determine the segments for wine consumers in Taiwan by product, brand decision, and purchasing involvement, and then determine the