國立交通大學

英語教學所碩士論文

A Master Thesis Presented to Institute of TESOL, National Chiao Tung University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts

以語料庫為依據之期刊論文的研究結果撰寫之研究

A Corpus-based Study on Reporting Results in Research Articles

研究生: 馬紹芸

Graduate: Shao-Yun Ma

指導教授: 郭志華 教授

Advisor: Prof. Chih-Hua Kuo

中華民國 99 年 1 月

January, 2010

i 論文名稱:以語料庫為依據之期刊論文的研究結果撰寫之研究 校所組別:國立交通大學英語教學研究所 畢業時間:98 學年度第一學期 指導教授:郭志華教授 研究生:馬紹芸 中文摘要 有鑒於英文在學術界的優勢地位以及學術英文(EAP)致力於發展更適合高等 教育的教材和課程設計,學術英文近年來備受重視。自 Swales 在 1981 年發表以 文類分析(genre analysis)方法探討學術文章之序論(Introduction)以來,此方法被廣 泛應用分析各種不同學術寫作文類。期刊論文不但在學術上有重要的地位,同時 也發展成一種複雜的文體而廣為研究。研究指出期刊論文各章節各自擁有結構和 詞彙使用的特色。過去的研究除了探討期刊論文中的章節架構之外,電腦語料庫 的使用讓學者得以藉由分析真實語料了解期刊論文中的細部語言使用特色以便 提供適合的課程設計。 報告學術研究的結果是期刊論文最重要的目的。期刊論文的作者會在三個主 要部份:摘要、研究結果、討論等三個部份中報告研究的結果。本研究藉由建構 出自於資訊工程和應用語言學兩個領域之期刊論文之語料庫,結合語料庫與文類 分析之方法研究兩種學術領域的期刊論文,並說明三個章節及兩個領域在報告研 究結果上之差異。各獨立章節分別建構為子語料庫(subcorpus)並利用自然語言分 析工具之協助以探討研究結果在期刊論文三個章節中言步(moves)結構與語言修 辭之差異。 首先我們進行了期刊論文中的言步分析,發現 AS (結果之摘要)在全部文章 中皆存在,表示這是在摘要中必使用的言步。之後可能由是 AI (結果之解釋), 或者 AA (結果之應用)伴隨並顯示一定之言步組合模式(move patterns)。在研究結 果部分的主要言步為 RR (結果之報告),RI (結果之解釋),RL (圖表位置之指示),

ii 以及 RS (結果之摘要)。另外,這個章節中言步組合的分析顯示出言步不僅可以 不同的順序呈現,同時也存在循環模式(cycles)。討論部分中常見的言步包含了 DS (結果之摘要), DI (結果之解釋),以及 DC (與文獻之比較)。言步組合的分 析顯示 DS 通常置於 DI 或 DC 前並呈現循環。此外,討論部份還包含了高頻率 的 DA (結果之應用)以及 DF (未來研究之建議)兩個言步。 這份研究的第二階段為內容分析(content analysis),結果顯示摘要(Abstract) 中研究結果的表達方式最為簡潔,詳細數據的描述,在報告的結果(Results)中呈 現,而討論(Discussion)的詳細程度(level of generality)則介於摘要和結果之間。 語言使用的分析結果包括高頻率動詞,助動詞,字詞組成(lexical bundles)和 語態。高頻率的動詞顯示 use、show、和 find 三個動詞在期刊論文這三個章節都 很常使用。其他高頻率動詞與結果之摘要相關,如 present;資料指稱的 see;和 加以解釋用的 suggest。在討論部份,助動詞的使用較其他兩部分為頻繁,表示 作者於討論研究結果時,使用助動詞以表示可能性的語氣,顯示作者對結果的謙

虛客氣。表達研究結果的常用字詞組成如 in this paper,results show that,this study

found,the results of this study。此外,當作者指稱圖表數據,會使用 shown in +

名詞或 of the table。語態的分析顯示出當報告結果時,主動句的使用遠超過被動 句。同時我們也探討了期刊論文在應用語言學與資訊工程兩種領域之間是否有相 似或不同的呈現方式。雖然這兩個學科領域在各言步使用頻率上表現出相似性, 在言步組合上則略有不同。 有研究指出高等教育學生經常遇到的問題是研究報告的撰寫。本研究致力於 讓學生了解如何撰寫各章節中的研究結果,同時教學上可提供課程和教材設計。 例如,教師應說明各章節常用的言步和言步組合模式,以在不同章節中適當地呈 現出研究結果。

iii

ABSTRACT

English for Academic Purposes (EAP) has attracted increasing attention among

scholars, instructors, and learners around the globe since EAP pedagogy proposes

learning materials and curriculum design to suit the needs of learners of higher

education. The genre-based approach, ever since Swales’ canonical study of the

Introduction section of research articles (RAs) in 1981, has been widely applied to the

analysis of various genres by EAP researchers. Studies investigating macro-level

features of various sections in RAs, the most extensively investigated EAP genre,

have pointed out that each section possesses a set of specific communicative purposes;

in addition, corpus-based analyses of micro-level features in RA sections provide

pedagogical implications for actual use.

Reporting research findings is the most crucial communicative purpose of an RA.

In its three major sections—Abstract, Results, and Discussion, RA writers have to

report the findings of their study. The present study, therefore, aims at exploring how

reporting research findings is realized in these sections in two disciplines by

integrating genre analysis with corpus-based text analysis. To achieve this goal, a

corpus of 48 RAs in the fields of applied linguistics (AL) and computer science (CS)

was constructed. Genre analysis was conducted using a scheme of move codes based

on previous studies, and NLP tools were used to analyze partially the macro- and

micro-level features in reporting research findings.

Move analysis revealed that in Abstract, the move AS (summarizing results)

occurs in all 48 RAs, indicating this is an obligatory move in Abstract. The move AS

may be followed by either AI (interpreting results and findings) or AA (indicating

implications/applications). Common moves in Results are RR (reporting findings), RI

iv

all of which are related to reporting overall or specific results. In addition, analysis of

move patterns in this section showed that moves occur not only in a variety of

sequences but also in cyclic patterns. Common rhetorical moves in Discussion include

DS (summarizing results), DI (interpreting results and findings), and DC (comparing

results to literature), and it was found that DS may be presented in cyclic patterns of

DS→DI or DS→DC. Except for the three moves, Discussion section also contains a relatively high frequency of DA (indicating implications/applications) and DF

(need/suggestions for future studies).

The second stage of this study was content analysis, which revealed that in terms

of generality and language use, research results are reported in the most concise and

general manner in Abstract. On the other hand, detailed description of data and

reference to factual evidence, such as visual data or interview excerpts, are included

in Results. Finally, the level of generality of the Discussion section lies between

Abstract and Results, focusing on interpretation, implications of results, and

comparison with other studies.

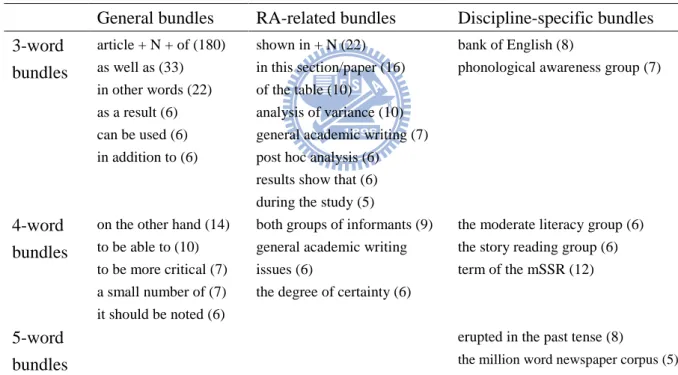

Analysis of micro-level features in reporting results includes high-frequency

verbs, modal verbs, lexical bundles, and voice. Examination of high-frequency verbs

showed that use, show, and find are commonly used in all three sections. Other

high-frequency verbs are related to summarizing results (present), locating data (see),

and interpreting data (suggest). With respect to modal verbs, they are used more

frequently in Discussion than the other two sections, indicating that writers often

qualify statements when discussing findings and making claims by using modal verbs

to show tentativeness. Investigation of lexical bundles showed that to report findings,

bundles like in this paper, results show that, and this study found are frequently used.

In addition, when writers try to make reference to factual data, bundles like shown in

v

voice revealed that when reporting results, active sentences greatly outweigh passive

sentences. Disciplinary variations were also explored to learn whether RAs in applied

linguistics and computer science report results in a similar or different manner. While

RAs of both disciplines show similar patterns in frequency rankings of moves, move

patterns in the two disciplines show slight variations.

Studies have pointed out that graduate students often encounter problems when

writing about research findings in the various sections of their RAs. It is essential that

we offer students information about how the different sections report research results

differently. This thesis study provides not only valuable pedagogical implications for

EAP practitioners but empirical data showing specific moves, move patterns, and

linguistic expressions frequently used in reporting research results in the various

sections as well. For example, instructors should indicate the common or obligatory

vi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The process of constructing and finishing a master’s thesis has never been easy, and I am very lucky and grateful to have received a lot of supports throughout the process. Therefore, I’d like to express my utmost appreciation to those who have showcased generous and patient assistance along the way.

First and foremost, I want to show my most sincere gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Professor Chih-Hua Kuo, for all her support and guidance throughout the past few years as a graduate student at the Institute of TESOL at National Chiao Tung University. By being her research assistant from the first year at graduate school, she has guided me to explore my interest in academic studies and helped me expand my scope of conducting academic studies as well as disciplines involved in the field of applied linguistics. What Professor Kuo did was not only related to academic domains and classroom studies, but also closely related to affairs outside school so I could overcome various obstacles during the process. Without her and her help, improvement or even this thesis would have never been possible to be finished.

For those who assisted me in collecting and analyzing data, their contributions also need to be accredited. For Louis and Zh-Hao, my classmate and friend, thank you both so much for working on my data to provide interrater reliability and guidance to comprehend text of a various discipline I have never been exposed to before. In addition, I’d also like to thank Nancy, my classmate and close friend, thank you for all the help and encouragements for the requirements of graduation. And finally, many thanks to my classmates and friends at the institute of TESOL, Hannah, Louie, and Mavis, thank you so much for providing assistance and care.

Next, I’d like to show my appreciation to my parents, who have supported and encouraged me all the time, especially during the times when I confronted despair and depression. Whenever I had to focus on my studies, you always tolerated me being absent from home so that I could concentrate on my work, and when I came home, you always opened your hearts so that I could share my joy and worry. The thanks also goes to my grandmother and uncles in Germany, who have lots of faith in me.

Last but not the least, there are two other important persons whose dedication cannot be ignored. For Professor Hsien-Chin Liou and Professor Ching-Fen Chang, how fortunate I am to have both of you as my committing members. Taking your courses during the graduate program provided me with useful insights to view academic studies and language teaching in various perspectives. And I’d also like to show appreciation for the efforts you’ve done to this thesis. Finally, I’d like to thank Professor Kuo again. Thank you so much for all the efforts and time you’ve spent so I could finish this thesis.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

中文摘要... i

ABSTRACT ... iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

LIST OF TABLES ... ix

LIST OF FIGURES ... x

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION ... 1

Background... 1

Rationale of the Study ... 5

Purpose of the Study ... 6

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW ... 7

English for Academic Purposes ... 8

Genre Analysis... 12

Research Articles ... 16

Abstract ... 17

Results ... 25

Discussion ... 32

CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY ... 40

Data Collection ... 40

Data Analysis: Move Analysis... 42

Data Analysis: Content Analysis ... 45

Data Analysis: Linguistic Realizations of Reporting Results ... 46

CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS ... 50

Move Analysis ... 51

Content Analysis ... 58

Levels of Generality ... 58

Language Use in Reporting Results ... 61

Linguistic Realizations of Reporting Research Findings ... 67

High-Frequency Verbs in Reporting Results ... 68

Use of Modal Verbs in Abstract, Results, and Discussion ... 75

Lexical Bundles in Reporting Research Findings ... 82

viii

Disciplinary Variations in Reporting Research Findings ... 100

CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS ... 109

Discussions and Summary of the Study ... 109

Implications and/or Applications of the Study ... 113

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 115

APPENDIX ... 116

Appendix Sources of Text ... 116

ix

List of Tables

Table 2.1 A list of rhetorical moves in RA Abstract ... 18

Table 2.2 A list of rhetorical moves in RA Results ... 27

Table 2.3 Rhetorical moves in Discussion, Conclusion, and Pedagogic Implications ... 37

Table 2.4 A list of rhetorical moves in RA Discussion ... 38

Table 3.1 The coding scheme applied for the analysis of RAs. ... 43

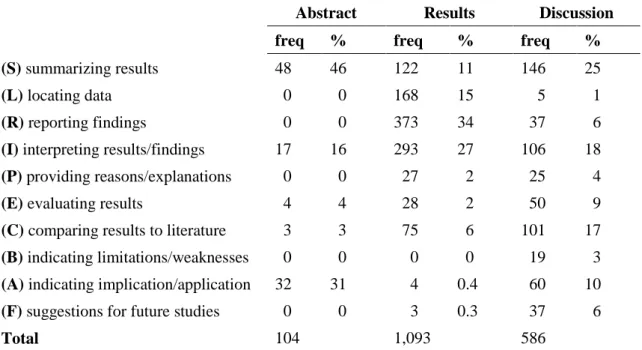

Table 4.1 Frequency of moves in the 48 RAs in the present study ... 51

Table 4.2 The top 10 high-frequency verbs ... 68

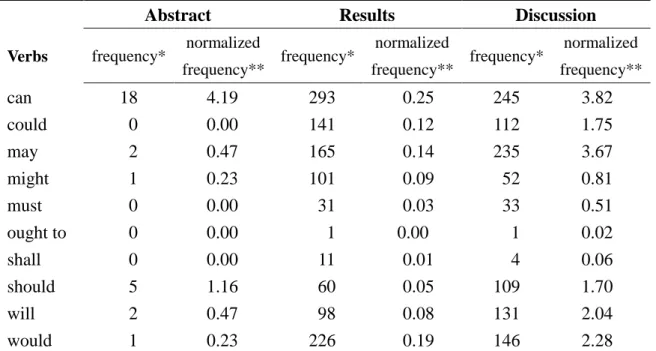

Table 4.3 Frequency of Modal Verbs in Each Section ... 76

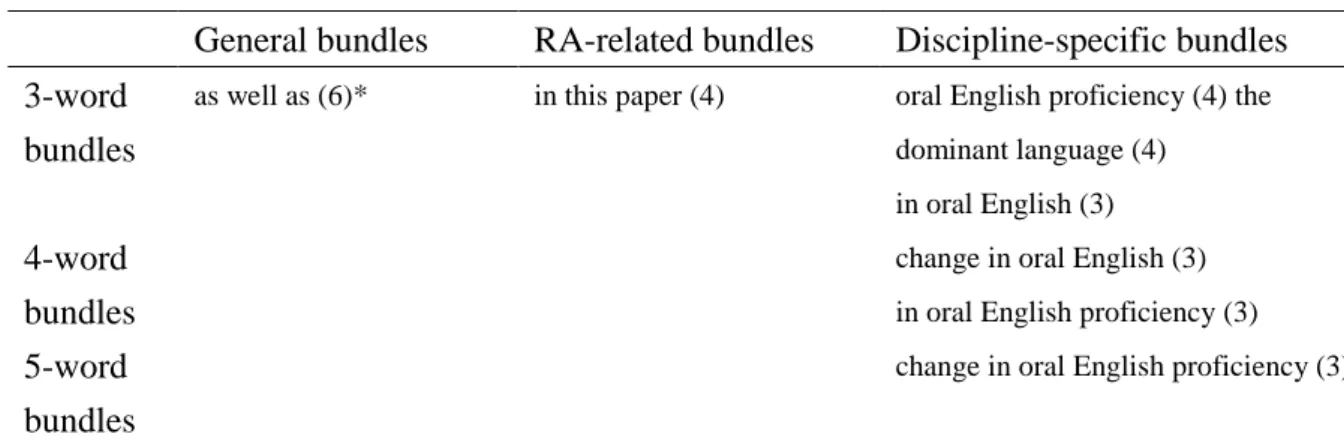

Table 4.4 Lexical Bundles in Abstract ... 83

Table 4.5 Lexical Bundles in Results ... 85

Table 4.6 Lexical Bundles in Discussion ... 92

Table 4.7 Percentages of active and passive sentences ... 95

Table 4.8 Frequency of moves across sections in two disciplines ... 101

Table 4.9 Move patterns in RA Abstracts ... 102

Table 4.10 Move patterns in RA Results ... 103

Table 4.11 Move patterns in RA Discussions ... 105

Table 4.12 Top 10 high-frequency verbs in the three RA sections across disciplines ... 107

x

List of Figures

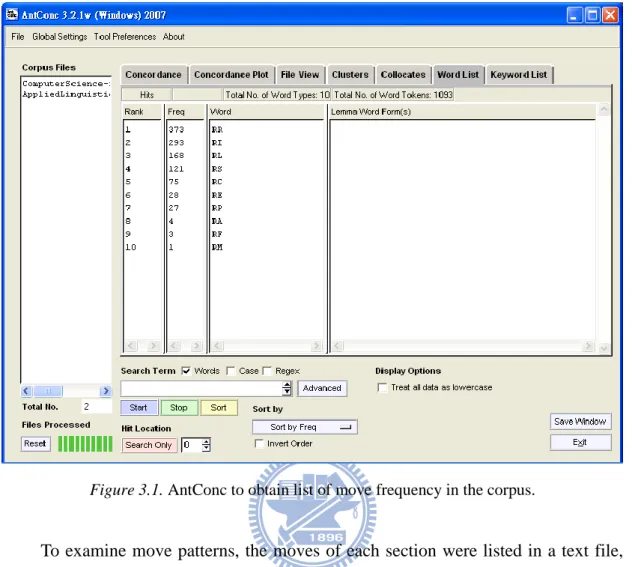

Figure 3.1 AntConc to obtain list of move frequency in the corpus. ... 45

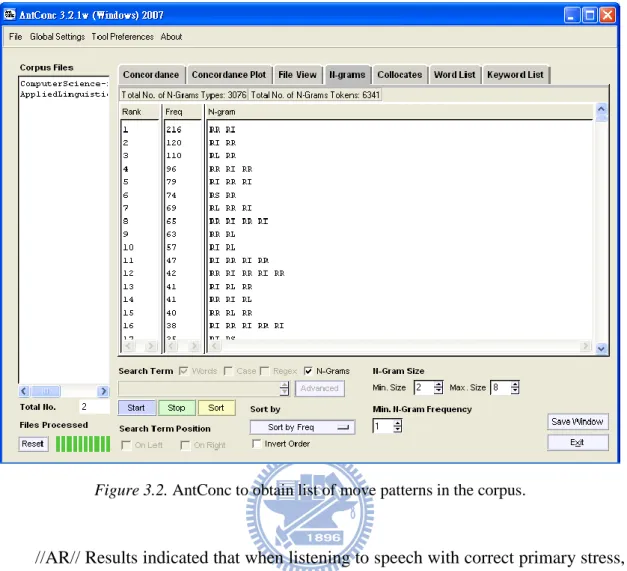

Figure 3.2 AntConc to obtain list of move patterns in the corpus. ... 46

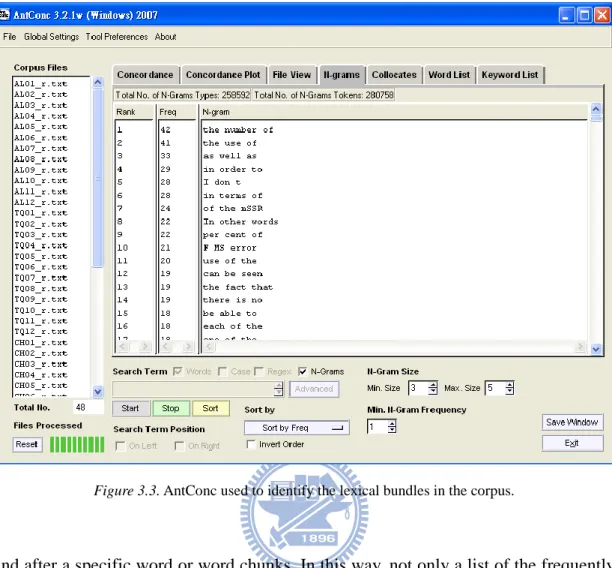

Figure 3.3 AntConc used to identify the lexical bundles in the corpus. ... 48

1

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Background

With the development of English as the lingua franca in the academic world,

writing scholarly English for publication has become a survival skill for both native

and non-native researchers. Non-native speakers (NNS), compared to native speakers

(NS), encounter even greater challenge in special language use in their disciplines as

they lack an extensive training of language use conventions in academic discourse

communities. Therefore, English for Academic Purposes (EAP), the teaching of

English with the aims of helping learners of higher education to study, do, and write

research in various academic disciplines, has received much attention among

researchers and instructors in the past three decades (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001;

Hamp-Lyons, 2001; Hyland, 2003; 2006; Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002). EAP

research and pedagogy put emphasis on the development of communicative skills that

learners need in order to be able to actively participate in the academic discourse

community.

Of various approaches to EAP, the genre-based approach has been widely

recognized as an effective method to analyze academic discourse for research and

pedagogical purposes. Genre, according to Swales (1990), is a class of communicative

events that share some sets of communicative purposes. After Swales (1981) proposed

genre analysis for examining the generic structure of Introduction in research articles,

researchers in this field have investigated various academic genres, exploring their

distinctive organizational as well as linguistic features. Common written academic

genres include research articles, textbooks, term papers, laboratory reports, and the

2

conferencing, and others. Genre analysis explores not only the rhetorical functions

and linguistic features of text but also its socio-cultural context, distinguishing itself

from traditional text analysis, which only takes the written product into consideration.

Developing learners‘ understanding toward academic genres means not only to

enrich their understanding of the social practices of their specific disciplines, but also

to enable them to become aware of the functions of texts and how these functions are

accomplished. The academic genre that has received the widest attention was the

research article (RA), regarded as a key genre that develops its distinctive generic

features characterizing the communicative purposes of the academics. Studies on RAs

have mostly focused on two aspects of this genre: rhetorical structures (Brett, 1994;

Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988; Hyland, 2000; Lorés, 2004; Samraj, 2002; Swales,

1990; Williams, 1999; Yang & Allison, 2003; 2004), identified in terms of moves, in

Swales‘ terms, and lexico-grammatical features (Bhatia, 2002) in the various sections of RAs. A move, or a rhetorical move, refers to a semantic unit in a specific genre that

the author uses for a certain communicative purpose or for the performance of a

rhetorical function. In Swales‘ (1981) well-known analysis of the Introduction section of RAs, the CARS (Creating a Research Space) model represents a robust model that

captures the functions and purposes of text by categorizing the text into moves and

steps. Move analysis, therefore, has become one of the major approaches to

examining genres, and of course, to the analysis of research articles to identify the

necessary information units that need to be included in this key academic genre.

Most RAs follow the framework of Abstract, Introduction, Method, Results,

Discussion/Conclusion, namely the IMRD structure (Bruce, 1983). Over the past

three decades, following Swales‘ canonical study (1981) on the Introduction section of RAs, researchers in this field have investigated each of these major sections (Brett,

3

Swales, 1990; Williams, 1999). These studies analyze the schematic structure of a

section in terms of moves and steps, and how each move/step is realized linguistically.

The move structures are closely associated with the communicative purposes or

rhetorical functions of the section in concern. For instance, Abstract provides a

concise summary of the study; Introduction focuses on background information,

literature review, and purposes as well as rationale of the study, possibly followed by

specific research questions; Method describes the way the study is carried out, tools

being used, criteria of selecting subjects or texts, and research procedure ; the Results

section aims at presenting and interpreting the major findings by giving descriptions

of both verbal and non-verbal data; and finally, the Discussion/Conclusion section

and/or other sections that end an RA entail a detailed discussion of the implications of

results, comparison of the data they obtained with other studies, limitations as well as

contributions of the study, and possibly suggestions for the future.

However, as revealed from a couple of studies which have explored more than

one section of RAs (Posteguillo, 1998; Yang & Allison, 2003), some sections in RAs

share similar rhetorical purposes with different emphases. For example, Posteguillo‘s study (1998) on the schematic organization of computer science RAs identified the

move ―statement of data/results‖ existing in both the Results and Conclusions sections. In addition, Yang and Allison‘s analysis (2003) of Results, Discussions, and Conclusions of applied linguistics RAs showed that the move of ―reporting results‖ occurs across the three sections with different emphases. In fact, genre analysis of

Abstract (Bhatia, 1993; Lorés, 2004; Samraj, 2005) also shows that the move of

―reporting/summarizing results‖ is an obligatory move in this part of RAs. In some specific disciplines such as computer science, reporting results may even occur in the

Introduction section (Posteguillo, 1998; Samraj, 2005). As many RA sections all

4

rhetorical functions in different sections and how this move is linguistically realized

across these sections.

In their popular textbook of academic writing, Academic Writing for Graduate

Students, Swales and Feak (2004) mentioned the differences among sections of

Abstract, Results, and Discussion in terms of levels of generalization. They claimed

that statements of results are presented in specific and closely tied to the data in the

Results section, restricted to a high level of generality in Abstract, and something

between these two levels in the Discussion section. However, they provided neither

empirical data nor linguistic realizations for such cross-sectional variations of a single

move. Pedagogically, one of the major problems of RA learners is to differentiate how

the move of reporting results should be presented in these sections. Specifically, they

do not know how the same move is realized differently in correspondence with the

communicative purposes or rhetorical functions of each section.

To explore these variations, it is essential for us to firstly identify the

communicative purposes of these RA sections. Abstract, according to Samraj (2001),

is a part that entails the major information, especially the findings, of a study and

provides an advance indicator of the content of the study so that the RA reader is able

to determine whether he or she needs to read the whole RA. The Results section not

only highlights but also interprets and comments on the new findings by focusing on

detailed and specific results, usually involving informative data presentation (Brett,

1994; Posteguillo, 1999; Weissberg & Buker, 1990; Williams, 1999; Yang & Allison,

2003). Discussion and Conclusion, being positioned after the Results section and

being the last part of an RA, are aimed rhetorically to examine the results in a larger

research context. Thus, the writers must make implications and generalizations of

research results and indicate the significance and contribution of these results to their

5

Feak, 2004; Yang & Allison, 2003). From the communicative purposes of these

sections, we may observe that these sections are all related to reporting research

findings; nevertheless, each emphasizes specific aspects of the findings and elaborates

these aspects in order to accomplish their respective communicative purposes in the

RA. From a genre perspective, as indicated in Swales‘ definition of genre (1990), the communicative purposes of a genre ―constitute the rationale for the genre‖, which in turn ―shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constrains choice of content and style.‖ (p.58) It would be beneficial to analyze these sections and investigate the possible differences or similarities in both the schematic structure

and the choice of content and style which are used to realize the communicative

purpose of ―reporting research findings‖ across the sections.

Rationale of the Study

Although prior genres studies investigating the macrostructure of RAs have

provided valuable insights into the rhetorical structures of individual RA sections,

most of them are still limited in a number of aspects. For instance, as mentioned

earlier, most of them focus on investigating only one section of RAs (Brett, 1994;

Holmes, 1997; Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988; Lorés, 2004; Williams, 1999). Some

studies, though analyzing the schematic structure of the whole RA (Posteguillo, 1999;

Yang & Allison, 2003, 2004), did not delve into a specific move that occurs across

different RA sections. Though Swales and Feak (2004) mentioned that these three

sections differ in levels of generality, their claim, as mentioned earlier, lacked the

support of empirical data and thus shows the need to explore the variations of this

move in these sections.

In addition, as Hyland (2000) pointed out, disciplinary variations are often obscured by the practicalities of EAP, which has tended ―to emphasize genre rather

6

than discipline, and similarity rather than difference‖ (p.4). As a matter of fact, different disciplines, especially disciplines in hard and soft sciences, can show

different rhetorical conventions to a certain degree as a result of the nature of their

research and their disciplinary culture.

Considering the importance of the communicative purpose of ―reporting research results‖ and the possible disciplinary variations in realizing the purpose, it is critical to examine how it is presented in moves and realized linguistically in the three RA

sections of Abstract, Results, and Discussions/Conclusions based on a reasonable size

of corpus of RAs in different disciplines.

Purpose of the Study

Taking a genre-based and corpus-informed approach, the present study intends to

explore how results or findings of a study, the most crucial element in an RA, are

presented across RA sections, including Abstract, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion,

in two disciplines that are different in nature. A corpus of research articles from the

fields of applied linguistics (AL) and computer science (CS) is compiled and analyzed

with a genre analysis of the moves related to reporting results and a text analysis of

the linguistic realizations of these moves.

The specific research questions are posited as follows:

1. How is reporting results presented in moves across the sections of Abstract,

Results, and Discussion?

2. How are the rhetorical moves of reporting results realized linguistically in these

sections?

3. To what degree is reporting results presented and realized differently in hard

7

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

As EAP pedagogy started to propose learning materials and curriculum

development to high education learners around the globe, it became necessary for

EAP researchers to investigate the organizational and linguistic features of academic

discourse to enable learners in different social settings to acquire appropriate

knowledge and skills for both study and research purposes. Genre-based analysis of

research articles, the central genre in the academic community of knowledge

production, has attracted a lot of interest of scholars in this field. Much research has

been conducted in the past three decades, exploring the generic patterns and language

use (Brett, 1994; Nwogu, 1997; Posteguillo, 1999; Swales, 1981; Yang & Allison,

2004). On the other hand, with the development of computer technology,

corpus-based research centered on linguistic investigations using research-oriented

specific corpora (Flowerdew, 2001). This approach to RA as a genre, by examining a

large amount of authentic data and using natural language processing (NLP) tools, can

not only reveal recurrent features of the genre for linguistic descriptions, but also

retrieve examples of specific language use in their discourse contexts, providing

materials, and pedagogical implications for EAP curriculum.

As indicated in the previous chapter, the present study intends to investigate the

linguistic realizations of reporting research findings across different sections of

research articles taking both a genre-based and corpus-based approach. Therefore, in

this chapter, an extensive review of important studies in related areas is given. First,

background information of EAP is presented. The development as well as the state of

art of EAP is explicated. The second part of review focuses on genre analysis,

8

proposed by important researchers. The last and most detailed part of this chapter

deals with studies investigating research articles, especially those on the information

structures and linguistic features of Abstract, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion

sections.

English for Academic Purposes

English for Academic Purposes (EAP), the teaching of English with the aim of

facilitating learners at higher education, usually pre-tertiary, undergraduate, or

postgraduate levels to study or do research in various academic disciplines, has gained

great attention among researchers and instructors in recent years as English has

become the lingua franca in the academic discourse community (Flowerdew &

Peacock, 2001; Hyland, 2006; Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002). The term EAP did not

appear until the 1970s as a branch of English for Specific Purposes (ESP), which is a

larger field that deals with research and teaching for specific purposes such as

business English, technical English, and use of English in other areas.

While early research of EAP only dealt with participants and situations observed

in inner circle countries where English is used as a first and official language, it is

now increasingly being offered to both native and non-native teachers and students in

the global academic community so that they could be equipped with the conventions

of language use shared within the academic discourse community. As Hyland (2006)

indicated in the introduction of his recent book English for Academic Purposes: An

advanced resource book (2006), EAP ―is today a major force in English language

teaching and research around the world.‖ (p.1) Student populations are more complicated and diverse than before with the growth of technology and globalization

of academic community, foreign students who differ from native speakers of English

9

have to adapt themselves to the challenges to successfully survive, graduate, and then

incorporate the communication skills in the workplace. Later in the book, Hyland

pointed out that nowadays EAP has become a ―specialized English-language teaching grounded in the social, cognitive and linguistic demands of academic target situations,

providing focused instruction informed by an understanding of texts and the

constraints of academic contexts.‖ (p.2) In addition, he noted that the learning needs of these learners focus on acquiring the communicative competencies to develop

disciplinary communication skills, such as delivering and comprehending lectures in

English, participating in meetings and conferences, carrying out administrative work,

and most important of all, conducting and publishing research using English.

Elsewhere, Hyland and Hamp-Lyons (2002) addressed the state of art of EAP,

commenting that while EAP started as a practical affair, current EAP ―draws on a range of interdisciplinary influences for its research methods, theories, and practices.‖

(p.3) In other words, EAP nowadays is no longer just a branch of ESP that deals with

research and teaching perspectives in academic settings of ESL countries but has

incorporated theoretical insights and research findings from other disciplines to

establish its own theories and research methods. As EAP rapidly expanded to play the

role of disseminating academic knowledge, several journals, such as Journal of

English for Academic Purposes and English for Specific Purposes were published to

record and develop theories and pedagogic uses in this field.

Around the world, as English has become the most dominant language in the

academic community, more and more non-native speakers in higher educational

programs, regardless in ESL or EFL settings, perceive the need to receive training in

academic English in order to be capable of writing postgraduate theses or dissertations

and publishing in international professional journals or their degrees or academic

10

structures and linguistic realizations of various academic genres (Hyland, 2006).

Investigation into different aspects of academic text has been carried out in the

past three decades (Flowedew & Peacock, 2001; Swales, 1990, 2001; Hamp-Lyons,

2001; Hyland, 2006; Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002). Early EAP studies in the 60s

mostly focused on linguistic and textual features that are descriptive in nature; in

addition, the studies did not account for the social contexts in which various types of

texts were developed or produced. Hyland (2001) further noted that early EAP

research was ―textual, with no contamination or complication asking authors why they wrote as they did.‖ (p.44) They relied on analytic grammar to investigate ―restricted languages and special registers.‖ Register analysis has been criticized a lot for being incapable of providing explanatory and sufficient descriptions of functions of text.

Later on, in the early 70s, researchers offered more sophisticated categorization of

register varieties and linguistic analyses for the syntactic structures of academic texts.

Throughout these two decades, researchers proposed different types of text analysis in

the hope of providing a more explanatory description of academic texts. After Swales

proposed his work on genres in 1981 and 1990, ―a focus on genre redrew the map of academic discourse by replacing rhetorical modes such as exposition or registral

labels as scientific language with text types‖ (Hyland, 2001, p.47) such as college textbooks, conference papers and abstracts, notes of academic lectures, term papers,

and journal articles. The genre-based approach to academic texts was concerned more

with the macrostructure, communicative purposes, and rhetorical functions of a

specific genre.

Another line of EAP research is concerned with the specialized content of text.

Strevens (1988) pointed out the need to relate content and themes of learning

materials to particular disciplines, occupations, and activities. As EAP learners usually

11

content to ensure better relevance and immediate success. In addition, Strevens also

emphasized the importance of centering on appropriate language conventions in terms

of syntax, lexis, discourse, semantics, and analysis of discourse. Studies in the past

have examined these features in different EAP materials, such as EAP textbooks

(Hyland, 2003), theses and dissertations (Swales, 1990; Kwan, 2006), and journal

articles (Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988; Brett, 1994; Lorés, 2004; Yang & Allison,

2003, 2004). Therefore, EAP teachers should make use of these resources and teach

learners the required macro and micro structures in text. Strevens‘ (1988) also indicated the difference of EAP courses from General English courses- in terms of

authenticity and language conventions, immediacy of effects, and specific needs of

the target learners.

In addition to Strevens‘ insightful overview of EAP-related pedagogy, Flowerdew and Peacock (2001) added some more factors that should be taken into

consideration when designing EAP courses. They pointed out that it is necessary to

include ―authentic texts, communicative task-based approach, custom-made materials, adult learners, and purposeful courses.‖ (p.13) Therefore, it can be observed that EAP

instruction should not only focus on raising learners‘ awareness of the conventions of academic genres that are crucial in EAP settings by using authentic materials and

task-based approach but also adopt discipline-specific materials for learners of

different academic fields. As a result, EAP researchers made use of authentic

academic genres to explore the features useful for academic learners and EAP courses

to equip learners with useful knowledge toward the academic genres. One of the most

widely-used text analysis would be genre analysis, which is discussed and reviewed in

12

Genre Analysis

Since the 1980s, researchers and language teachers, especially those concerned

about EAP, have shown an increasing interest in investigating academic text with a

genre-based approach. The emergence and development of this approach is much of a

result from Swales‘ canonical study of the Introduction section of research articles in 1981 and later, the well-accepted book on genre analysis in 1990.

Genre refers to a type of discourse occurring in a particular setting, which has

both distinctive and recognizable patterns and norms of organization and structure. In

other words, it refers to a group of texts that share similar features so that both writers

and readers are aware of what to expect when writing or reading such a text (Hyland,

2006; Richards & Schmidt, 2003; Swales, 1990; Tarone et al., 1981). Different

scholars have various definitions of the term genre; for example, typification of

rhetorical action, as shown in Miller (1984) and Berkenkotter & Huckin (1995);

regularities of staged, goal oriented social processesin Martin, Christie, and Rothery

(1987) and Martin (1993); Most of the genre studies, such as Samraj (2002), Bhatia

(1993), Kwan (2001), Yang & Allison (2003, 2004), however, follow the definition

proposed by Swales (1990), in which genre refers to

a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse community, and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This rationale shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constraints choice of content and style. Communicative purpose is both a privileged criterion and one that operates to keep the scope of a genre as here conceived narrowly focused on comparable rhetorical action. In addition to purpose, exemplars of a genre exhibit various patterns of similarity in terms of structure, style, content and intended audience. If all high probability expectations are realized, the exemplar will be viewed as prototypical by the parent discourse community (Swales, p.58).

13

Such a definition of genre emphasizes ―shared set of communicative purposes,‖

―examplars of genres varying in their prototypicality,‖ and ―discourse community‘s nomenclature and rationale of a genre.‖ (pp. 45-58) From the definition, genre analysis not only accounts for the linguistic aspects of academic texts, but also

emphasizes the communicative purposes that constitute the rationale, which in turn

shapes the schematic structure of the genre. In addition, as the conventions of a genre

are largely exemplified in the generic texts by expert members of the discourse

community, it is essential for researchers to examine these examplars of genres in

order to reveal various patterns of similarity, which can be viewed as prototypical of

the genre (Swales, 1990: 58).

The need for an effective research method for analyzing academic text was also

indicated in the study by Hopkins and Dudley-Evans (1988) who examined the

Discussion section of research articles. They pointed out that while early ESP research

dealt with practical issues for classroom needs, there is ―an increasing awareness …

that much more research needs to be done … to prepare students for the tasks they need to carry out in English. [Thus] ESP work needs a system of analysis that is able

to … differentiate between different types of text [and] provide useful information about the nature of different types of texts that is of pedagogic value.‖ (p.113) In other words, they perceived the need to describe organizations of different types of texts so

that both teachers and learners develop an understanding of different text types,

namely genres.

According to Bhatia (2001), genre analysis refers to the study of ―situated linguistic behavior in institutionalized academic or professional settings.‖ (p.22) To investigate the features of distinctive genres, it is necessary to study how writers

conventionally sequence and organize their texts to achieve particular communicative purposes. Bhatia further concluded that genre analysis is ―narrow in focus and broad

14

in vision (p.24)‖ as it takes both language use and specific realization of language into consideration. Therefore, it may be concluded that genre analysis provides a rather

objective viewpoint while taking not only the text, but also the discourse community

into consideration. As Swales (1990) noted that every discourse community has its

unique convention of language use; it is thus necessary to pay special attention to the

conventions of academic genres and investigate the similarities and/or differences of

these genres across disciplines.

Genre analysis has developed in a number of different directions in the past

two decades. Some researchers have examined spoken genres, such as seminars or

academic lectures (Dudley-Evans, 1994; Weissberg, 1993); more studies have aimed

at exploring detailed analyses of written genres, such as research articles, theses,

dissertations, and others. Most of the studies have focused on the rhetorical structure

of a genre in concern. For instance, genre studies on research articles have explored

the schematic structure of this genre in a particular discipline or one of its major

sections, such as Introduction (Swales, 1981, 1990; Samraj, 2005), Method (Kwan,

2001), Results (Brett, 1994; Williams, 1999), Discussion (Holmes, 1997; Hopkins &

Dudley-Evans, 1988;), and Abstracts (Lóres, 2004; Martín, 2003; Samraj, 2002, 2005).

In investigating the macrostructure of a genre, researchers usually take a corpus-based

empirical approach so that a larger amount of authentic text can be actually examined

in one single study. Moves (small discourse units that represent a rhetorical function)

and steps (smaller segments that serve more specific functions and subcategories of

moves) are used by researchers to indicate the information units of text. They also

reflect the communicative purposes of a section or a genre. An early move analysis

model was a 4-move model, the so-called CARS model proposed by Swales (1981) to

describe research article Introduction. Later studies that took a genre-based approach

15

of different academic genres. As a result, genre analysis has had significant impacts

on later EAP studies. In addition, genre analysis enables researchers to provide not

only the information structure but also lexico-grammatical usages of academic genres,

especially research articles (Brett, 1994; Holmes, 1997; Hopkins & Dudley-Evans,

1988; Kwan, 2001; Lóres, 2004; Martín, 2003; Nwogu, 1997; Posteguillo, 1999;

Samraj, 2002, 2005; Swales, 1981, 1990, 2004; Swales & Feak, 2004; Williams, 1999;

Yang & Allison, 2003, 2004).

Recently, the research focus of research articles has shifted to variations within

a particular genre, such as abstracts of research articles in different disciplines

(Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988; Hyland, 2000) or research articles from different

journals in a single discipline (Brett, 1994; Lorés, 2004; Posteguillo, 1999; Samraj,

2001; Yang & Allison, 2003, 2004). Studies of research articles from different

disciplines showed disciplinary variations. Although it has been considered that

research articles from similar disciplines should be presented in similar layout and

fashion, some studies found that this is not necessarily the case as journal articles

from the same discipline could also show different uses in terms of moves or lexical

variations (Samraj, 2001; Yang & Allison, 2003, 2004).

As many studies have focused on examining the generic features of research

articles, it has become one of the academic genres that have received the most

attention among researchers. In the following section, the importance of research

articles and studies on this genre are discussed and reviewed to provide various views

of the researchers and information about what has already been investigated and

16

Research Articles

EAP researchers have tried to examine the features of various academic genres,

particularly research articles (RAs), the genre that has received the most attention. A

line of studies on RAs investigated the macrostructures of the major sections of RAs

of different fields, such as applied linguistics, business, sociology, or computer

science. These studies analyzed the information structure of one major section (Bhatia,

1993; Brett, 1994; Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988; Samraj, 2005; Swales, 1981),

several sections of RAs (Yang & Allison, 2003, 2004), or the rhetorical organization

of the whole RA (ElMalik & Nesi, 2008; Kanoksilapatham, 2005; Nwogu, 1997;

Posteguillo, 1999). A second line of research examined the micro-level features of

RAs, namely the lexico-grammatical linguistic features, such as verb tenses, uses of

voice, modals, and so on, which characterize special language use in either the whole

RA or in a specific section. Still a third line of research tried to link the macro- and

micro-features of the academic genre; in other words, specific lexico-grammatical

uses closely related to the macrostructures or discourse-level features of RAs, such as

metadiscourse, hedges, or reporting verbs. As RAs are a highly conventionalized

genre, the results of existing research have already revealed much about the rhetorical

moves and linguistic features of the genre.

Studies analyzing the macrostructures of RAs have revealed that information

patterns or moves can occur across sections; for example, the CARS model proposed

by Swales (1981) for the Introduction section was found to be adaptable to the

Abstract of certain RAs (Bhatia, 1993; Lorés, 2004; Swales & Feak, 2004). In

addition, the move of ―summarizing/reporting major findings‖ is also a move that usually occurs across several sections, namely Abstract, Results, Discussion and

Conclusion. What‘s more, it is observed that the Discussion and the Conclusion sections have many moves in common (Yang & Allison, 2003). Since each section of

17

an RA performs a number of rhetorical functions, for example, Abstract plays the role

of providing a concise overview of the whole RA, it is of interest for us to know

whether the same move occurring across several sections performs the same or

different rhetorical functions and whether there are different linguistic realizations of

the same move in different RA sections.

As the purpose of the present study is to investigate the move of ―reporting research findings‖ across sections in RAs, it is essential that studies on the various sections, namely Abstract, Results, Discussion and/or Conclusion sections, where this

move often occurs are reviewed so that the role this move plays in the sections in

concern can be identified. In this section, a detailed review of the studies on these

sections is thus given, focusing on the move structure of each section, particularly the

rhetorical functions or linguistic realizations of ―reporting research findings‖ that have been found.

Abstract

Abstract is an advance indicator of RAs. It provides the readers with a brief

preview or summary of the study (Bhatia, 1993; Hyland, 2000; Martín, 2003; Lorés,

2003; Samraj, 2002; Swales, 1990; Swales & Feak, 2004; Van Bonn & Swales, 2007;

Weissberg & Buker, 1990). In other words, this very beginning part of an RA must

appeal to readers, showing that it is worth for them to continue reading the complete

RA (Hyland, 2000; Weissberg & Buker, 1990). Abstract, therefore, is promotional in

nature. As Hyland (2000) argues, Abstract ―selectively sets out the stall, highlighting

important information and framing the article that it precedes, but it does so in such a

way as to encourage further examination and draws the reader into the more detailed

exposition. (p.63-64) Hyland‘s remarks pinpoint the importance of Abstract in influencing readers‘ decision about reading or not reading the complete RA. To

18

accomplish this communicative purpose, it is essential for a writer to demonstrate the

significance of the findings of his/her study in Abstract. However, with the limitation

of space, Abstract writing must be very concise.

As Abstract is concise in nature and considered as a miniature of the whole study,

it has been found that it often consists of four basic information units corresponding to

the four major sections of RAs, namely Introduction, Method, Results, and

Conclusion (Bhatia, 1993; Martín, 2003; Samraj, 2002; Swales & Feak, 2004;

Weissberg & Buker, 1990). However, there were also studies that separated the

Introduction move into move of Introduction and move of Purpose (Hyland, 2000) or

used other names for the moves. The studies investigating the macrostructure of

Abstract have identified the moves as presented and summarized in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. A list of rhetorical moves in RA Abstract (summarized from studies reviewed)

Move Function

Introduction/Background Provides background information of the current academic society and establishes context of the paper.

Purpose Indicates the purpose, hypothesis, and features of the study.

Method/Procedure Provides information of the research method and procedure of the study. Product/Results States main findings, results, or what has been accomplished.

Conclusion Summarizes the results obtained, draws inferences, or points out significance.

As seen from Table 2.1, some researchers might have used the move

―Background‖ (Weissberg & Buker, 1990) as a variation for ―Introduction‖ (Hyland, 2000; Martín, 2003), ―Procedure‖ (Weissberg & Buker, 1990) for ―Method‖ (Hyland, 2000), or ―Products‖ (Hyland, 2000) for ―Results‖ (Martín 2003; Samraj, 2002). Although different scholars might use different terminologies, they all agree that

19

Bhatia (1993) investigated the macrostructure of RA abstracts and pointed out

that an abstract is itself ―a description of factual summary of the much longer report … [providing] the reader an exact and concise knowledge of the full article‖ (p.78) and includes descriptions of what the author did, how the author accomplished

it, what the author found, and how the author made conclusions from the obtained

findings. To examine how information of these aspects is summarized in a concise

manner, Bhatia presented four moves to answer the four questions: introducing

purpose, describing methodology, summarizing results, and presenting conclusions.

This study provided useful insights of the macrostructure of RAs, showing that

Abstract is just like a miniature of the whole RA that entails the information units of

IMRC.

After Bhatia‘s study on the overall organization of RA abstracts, Samraj (2002) compiled a small text corpus of 20 RA abstracts from two disciplines, conservation

biology and wildlife behavior, to examine not only the macrostructure but also the

linguistic features of this section. For text analysis, she assigned each sentence into a

move, and sentences that included two moves with a main sentence and a subordinate

clause were coded for both moves, namely a combination of two moves. The

macrostructure identified includes: situating the research, purpose, methods, results,

and conclusion. However, she further noted that even though the same moves were

found in most abstracts, there were subtle variations, such as the frequency and the

space these moves occupy in an Abstract. This minor difference, according to Samraj,

could be related to the different disciplines the articles were selected from; in other

words, there may be disciplinary variations. As a whole, it can be observed that the

move of ―Results‖ seems obligatory across disciplines serving the function of highlighting research findings for the purpose of attracting readers‘ attention.

20

Although there seems to be a general agreement about the macrostructure of RA

Abstract from the studies reviewed above, the study by Lóres (2003) showed a

slightly different result. She agreed that while most RA Abstracts tend to follow the

sequence of IMRC in macrostructure, she pointed out that there could be even more

variations in the macrostructure while she examined 36 abstracts from four journals in

the field of applied linguistics and found that almost a third of the samples in her

study (30.5%) did not follow the rhetorical structure of IMRC; instead, they followed

the structure described by Swales‘s (1990) CARS (Creating a Research Space) model.

The CARS model specifies three moves/steps for the Introduction section of RAs,

namely establishing a territory, establishing a niche, and occupying the niche. This

type of abstract, according to Lorés, mirrors the structure found in the Introduction

section (Swales, 1990) instead of the IMRC.

Moreover, Lóres found that besides the conventional IMRC structure and the

CARS model, a few abstracts (three out of the 36 abstracts in the corpus) did not

match either of the two structures but showed a combination of both types, starting

with a CARS structure in which an IMRC structure is embedded. ―The final section [of the abstract] usually announces the principal findings or the way in which the

research is going to fill the gap found or questions raised; [in other words, it] indicates

the scope of the paper and outlines some general findings.‖ (p.284)

Swales & Feak (1994; 2004) also mentioned two different types of abstracts,

indicative and informative abstracts. The CARS model-type abstracts, according to

Lóres, match indicative abstracts as indicative abstracts only point out what type of

research was carried out and provide general findings; on the other hand, informative

abstracts, also known as results-driven abstracts, focus on the findings, particularly

supported by informative data (Lóres, 2003; Swales & Feak, 2004; Weissberg & Buker, 1990). The combinatory type of abstracts found in Lóres‘ study does not match

21

either the indicative or the informative abstracts, but corresponds to, according to

Lóres, the mixed type of indicative-informative abstracts. To sum up, though these

studies indicated that the functions, linguistic realizations, and rhetorical structures

might influence the organization and type of abstracts, they did not mention if any

disciplines prefer to use one type of abstract or another. Therefore, more

representative data of these three types of abstracts and disciplinary preference should

be investigated.

Another line of researchers used these findings as a basis and examined the move

sequences/structures in this section (Hyland, 2000; Samraj, 2002; Martín, 2003). Most

studies agreed that the move ―Product/Results‖ can be regarded as an obligatory move in abstracts as this move occurs in a high frequency in their studies (Hyland, 2000;

Samraj, 2002). In addition, studies that investigated the move sequences/structures

of RA abstracts found that regardless of indicative or informative abstracts, most of

them tend to follow the sequence of stating the author‘s introduction, followed by a

brief description of the methodology being used, and then the presentation of research

findings (Hyland, 2000; Lóres, 2003; Samraj, 2002).

Samraj‘s study (2001) on the macrostructure of RA abstracts from two sub-disciplines in biology found that the move of ―Results‖ occurs consistently in

abstracts of RAs from both disciplines as this part demonstrates the most crucial

contribution of the studies to the disciplines. This result shows that it is necessary to

include the element of reporting research findings in RA abstracts. Similarly, Hyland‘s study (2000) of a corpus of 800 abstracts from eight disciplines tried to identify the

common communicative purposes. In his study, he made a similar claim to the studies

by Samraj (2002), stating that a very high percentage of papers (94%) in his corpus

included the move of ―Product,‖ a move presenting the findings or what the study has accomplished.

22

However, Martín (2003) found that the move of ―Product/Results‖ was not

obligatory in his corpus of Spanish abstracts. He assembled 160 RA abstracts written

in both English and Spanish in the area of experimental social sciences and found that

the structural unit that occurred the least frequently was the Results element, with an

occurrence rate of 86.25% in English abstracts and 41.25% in Spanish abstracts,

respectively. Though he did not specifically provide an explanation of the finding, it

could be inferred that this phenomenon was probably related to the English RAs that

Spanish writers read; in other words, as Spanish writers read English abstracts, they

memorized and eventually used the language conventions observed during reading,

which thus affected their writing when they constructed abstracts in English. Though

we may not have a clear understanding of the convention of Spanish Abstracts, it may

be concluded that while Spanish researchers wrote their RAs in English, they tended

to follow the conventions they obtained and observed while reading RAs in English. It

is still not known if the move of ―Results/Product‖ is obligatory or not, or whether the occurrence of this move might be influenced by different disciplines or even various

languages. In the present study, the occurrence of this move and its linguistic

realizations will be investigated to get a more insightful view of these features when

reporting researching findings.

Studies on the common move sequence/structure have tried to examine what

combinations of moves are prevalent in this section. Hyland‘s (2000) five-move framework (I-P-M-Pr-C), including Introduction, Purpose, Method, Product, and

Conclusion, was used to identify the common move sequences of abstracts in his

study. He concluded that among the different move sequences identified, two-move

structures, P-M-Pr and I-P-Pr, were common, both including the move of presenting

the results. Similarly, Samraj‘s (2002) study on abstracts from biology followed a similar move sequence, stating that though the author might start with either a move

23

of situating the research or of connecting to a problematic real world, it was

eventually followed by what has been found and what conclusions may be drawn

from the findings. Moreover, Samraj noted in her study that the method element,

which only occurred in a frequency of 50%, was often omitted and followed by

statement or information related to results and conclusion. Therefore, common move

sequences in Samraj‘s study can be represented as P-Pr-C or I-Pr-C.

The informative-indicative abstract in Lóres‘ (2003) study usually followed the

sequence of the CARS model with an IMRC structure embedded. An excerpt of

abstract in her study consists of three sections: the first section corresponds to

―establishing a territory‖ of CARS and includes ―the general purpose‖ of IMRC; the second section corresponds to ―establishing a niche‖ of CARS and incorporates ―the methodology‖ of IMRC; the final section is found to correspond to ―occupying a niche‖ with the findings summarized and presented. Since only three abstracts in her study belong to this type of abstracts, it is hard to make generalizable conclusions.

Although the excerpt in Lóres‘ study seems more indicative than informative, more data are needed to draw a reliable conclusion of the move sequence of

informative-indicative abstracts. To sum up, the linear sequences of IMR or IRC from

IMRC structure seem to be more popular regardless of indicative or informative

abstracts.

In addition to the macrostructure of RA abstracts, a variety of linguistic features

have also been explored, such as verb tenses, hedges, metadiscourse, voice, and uses

of parts of speech (Martín, 2003; Samraj, 2002; Van Bonn & Swales, 2007).

In Samraj‘s study (2002) on abstracts of two journals of biology, he found that ―usually the purpose, methods, and results moves are in the past tense while the background and conclusion moves are in the present tense [with] the transition from the results to the conclusion move clearly revealed by the tense switch‖ (p.49-50).

24

Samraj (2002) found that modal verbs, such as suggest, ―constitute about half the

hedging devices employed … and most of [them] are found in the conclusions move‖ (p.51-52). As for hedges occurring in the results move, Samraj pointed out that this

occurs when authors make interpretations of numerical figures. Therefore, it may be

concluded that modal verbs are usually used either to qualify the interpretations of

numerical data or the conclusions/implications of results. The final aspect investigated

in her study was the use of pronoun. The use of first-person pronouns in Samraj‘s

study revealed variation between the two journals; abstracts of one journal showed a

frequency of 21% in the use of first-person pronouns as the subject of a sentence,

abstracts from the other journal eschewed the use of pronouns. Therefore, it might be

concluded that this variation is related to the nature of the two journals.

Another study investigating linguistic features of abstracts is conducted by

Martín (2003). He examined the linguistic features of the results unit. The ―Results‖

move, in which authors make new knowledge claims, aims to report the main results

obtained or observed in the study. According to Martín, results ―are stated most frequently … by means of a sentence initiated with an inanimate noun (e.g. the

findings, the analyses, the results, etc.) in subject position and followed by … verbs

such as show, reveal,[and] indicate. (p.36; Italics in original)‖ (p.37). Results elements

in English abstracts in Martín‘s study were found to use verbs in the past/passive voice (showed/was found, was observed) frequently. Thus it can be concluded that the

Results element would be stated in a more concise way using passive voice due to the

terse nature of RA abstracts. In addition, another study by Van Bonn & Swales (2007)

that tried to compare bilingual abstract pairs of English and French found that the

reporting verbs in French were more assertive than those used in English, indicating

that hedges is more frequently used when writers try to draw conclusions from the

25

In the studies reviewed, there are variations in RA abstracts in terms of

macrostructure and linguistic features in different or similar disciplines (Lóres, 2003;

Martín, 2003; Samraj, 2002; Van Bonn & Swales, 2007). Among the disciplinary

variations of linguistic features, Hyland (2000) specifically pointed out that the move

of ―Product‖ is stated differently in soft science and hard science. The statement in the former focuses on discussions or arguments of a topic, while in the latter puts

emphasis on reporting research findings. This observation is worth further exploration

when RA Abstracts from disciplines of both hard and soft sciences are examined.

To sum up, studies investigating the macrostructures and linguistic features of

abstracts have revealed the macrostructure of this shortest part of an RA. Although

they showed disciplinary variations and possible differences between different types

of abstracts, reporting results seems a near-obligatory move in an abstract no matter

which discipline it belongs to. However, a few questions need further exploration; for

example, as different researchers found that there are three types of abstracts, namely

informative, indicative, and informative-indicative abstracts, is there a tendency that

some certain studies with similar methodologies or within similar disciplines prefer to

adopt one type of abstract to another? In addition, as this section acts as an indicator

of the whole RA, how do researchers report their findings linguistically different?

These are all aspects that are worth to be considered when examining RA Abstracts

from either similar or different disciplines.

Results

The Results section of RAs is a part in which researchers report, interpret, and

comment on what they have found or observed from the study they conducted.

Studies related to this section investigated only this section (Brett, 1994; Williams,