服務學習對學術英文寫作籌創過程之影響

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 99-2410-H-004-202- 執 行 期 間 : 99 年 08 月 01 日至 101 年 02 月 29 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學外文中心 計 畫 主 持 人 : 劉怡君 計畫參與人員: 此計畫無其他參與人員 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 101 年 03 月 02 日

服務學習在亞洲各國逐漸受到重視,許多相關的教學法和課 程因應而生,然而大多數的服務學習研究是以英語或英語為 第二外語的語言為研究情境,在台灣目前相關的研究並不多 見。本文希望研究瞭解服務學習的教學法對台灣學生的英文 寫作所產生的影響。研究問題涵括兩個面向: 一、服務學習 對學生在寫作時的認知經驗轉移方面有何影響? 二、 服務學 習對作者的寫作身分角色的架構有何影響。共二十六位學生 參與了此量化研究,研究結果發現,服務學習對學生在寫作 上的經驗轉移影響可分為四, 對學生在作者角色架構上的影 響有兩個層次。除此之外,相關的教學提示於本文末了也略 有提出以供有興趣的老師參考。 中文關鍵詞: 第二外語寫作、第二外語認知寫作過程、學術寫作教學 英 文 摘 要 : Abstract

Various service learning (S-L) practices and programs in higher education are mushrooming in Asian

countries (Kraft, 2002). This educational shift has resulted in pressing demand for S-L studies in EFL contexts. However, most of the studies of S-L in TESOL are conducted in the contexts where English is the first or the second language. To fill the gap by exploring S-L research in EFL context and to connect S-L and L2 writing research, this study attempts to investigate the impact of S-L on Taiwanese students’ writing from the socio-cognitive and rhetorical

perspectives. Moreover, theoretical as well as teaching implications are suggested.

Twenty six students participated in this qualitative research. The teacher researcher triangulated the collected data and categorized students’ experience transfer into disconnection, connection, negotiation and invention. Besides, the impact of S-L on

students’ textual identity construction is identified as coherent and incoherent.

Incorporation of Service Learning in Academic Writing: Experience Transfer and Identity Construction

Abstract

Various service learning (S-L) practices and programs in higher education are

mushrooming in Asian countries (Kraft, 2002). This educational shift has resulted in pressing demand for S-L studies in EFL contexts. However, most of the studies of S-L in TESOL are conducted in the contexts where English is the first or the second language. To fill the gap by exploring S-L research in EFL context and to connect S-L and L2 writing research, this study attempts to investigate the impact of S-L on Taiwanese students’ writing from the socio-cognitive and rhetorical perspectives. Moreover, theoretical as well as teaching implications are suggested.

Twenty six students participated in this qualitative research. The teacher researcher

triangulated the collected data and categorized students’ experience transfer into disconnection, connection, negotiation and invention. Besides, the impact of S-L on students’ textual identity construction is identified as coherent and incoherent.

Incorporation of Service Learning in Academic Writing: Experience Transfer and Identity Construction

Introduction

Service learning (S-L), which is rooted in experiential learning, is defined by Seifer (1998) as “a structured learning experience that combines community service with explicit learning objectives, preparation and reflection” (p. 274). Research of S-L has not been embraced as one of the major strands in the field of TESOL because of its inherent research complications. It is reported that S-L research has difficulties in examining outcomes with individual’s divergent engagement, in enhancing external validity for generalizability (Furco, 1994; Howard, 2003), in eliminating asymmetrical power relations between the givers and receivers (Deans, 2000; Flower, 2002; Himley, 2004; Morton, 1995) and in constructing instruments to evaluate dynamic outcomes across disciplines and service sites (Billig, 2000; Furco, 2003; Gray, 1996). Another confounding issue of S-L research is the inconsistent findings of its outcomes. On one hand, some researchers reported that S-L helps students gain understanding of course content (Astin et al., 2000; Bringle and Hatcher, 1995; Bringle and Hatcher, 1996; Eyler and Giles, 1999; Heuser, 1999; Markus et al, 1993), enhance learning motivation (Bryant and Hunton, 2000; Eyler and Giles, 1999; Howard, 1998) and promote higher-order thinking skills

(Batchelder and Root, 1994; Deans, 2000; Eyler and Giles 1999; Hesser, 1995). On the other hand, some other researchers found little relationship of S-L with students’ course grades

(Kendrick, 1996; Gray et al. 2000; Miller, 1994), academic performance as well as professional skill development (Gray et al. 2000).

In spite of not being prevailing in TESOL, S-L in Asian countries like Mainland China, Taiwan, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Philippines, and Korea has been gaining attention. An increasing number of teachers are promoting service learning, and various S-L practices and programs in higher education are mushrooming in Asia (Kraft, 2002). This educational shift has resulted in pressing demand for S-L studies in EFL contexts. However, besides the issue of research complications, most of the studies of S-L in TESOL are conducted in the contexts where English is the first or the second language. Little research studies S-L in EFL contexts.

To fill the gap by exploring S-L research in EFL context and to connect S-L and L2 writing research, this study attempts to investigate the impact of S-L on Taiwanese students’ writing from the socio-cognitive and rhetorical perspectives. Moreover, theoretical as well as teaching implications are suggested.

2. Literature Review

Dewey and S-L researchers believe that experience becomes educative only if it has been transformed into meaningful codes and connected with the existing schemata through critical reflection (Bringle and Hatcher, 1999). However, transfer between experience and academic modules does not automatically take place as generally assumed. A number of researchers have reported that cognitive transfer is learning context specific (Belmont, 1982) and is difficult to be provoked (Carson, et al. 1990; James, 2006, 2009; Perkins & Martin, 1986; Tardy, 2006). Eisterhold (1990) also agreed with the findings of inactivity in learning transfer. She suggested that students need to learn to “restructure” the received information in order to facilitate

learning transfer (p. 97).

Salomon and Perkins (1987) proposed the theory of high/ low road transfer. Low road transfer refers to reflexive performances which can be automatically triggered due to mastery through practices and contextual similarity (p. 151). For example, one’s knowledge of driving a car can be transferred to drive a truck. In contrast, high road transfer involves deliberately cognitive abstraction from one context to another. This transfer is conscious and effortful, and it is independent from contextual similarity, for example, strategies of problem solving or decision making (p. 152).

Most of the traditional education in general encourages low road transfer through practices. In TESOL, for example, James (2009) investigated ESL students’ learning transfer in writing. He analyzed students’ text-responsible tasks and course writing tasks and assessed them with an instrument for 15 learning outcomes. James found that only a few learning outcomes

transfer from the course to the task, such as classifying (content level), using cueing statements (organization level), avoiding sentence fragments and avoiding subject plus pronoun repetition (language level). He further suggested that the transfer at the content and organizational level is more task-specific than the transfer at the language level. However, in a broader sense

according to Salomon & Perkins (1987), the transfer at the levels of content, organization or language is not the activity of higher level thinking but the activity of low road transfer. Moreover, the course writing and the task writing should be seen as similar rather than different transfer contexts of writing exercises. Therefore, James’s finding of distinctive differences in learning outcomes and little transfer generated from students’ writing tasks should suggest that students either are insensitive to the contextual similarities or they lack writing skills.

Writing connected to S-L may encourage implicit learning and high road transfer of knowledge construction. In a writing curriculum wedded with S-L, on one hand, community services offer complex stimulus for social interactions; on the other hand, writing tasks can serve as the perfect reflections that enhance cognitive exercises to “restructure” the acquired new experience for meaning making. Theorists of both experientialism and situated learning believe that hands-on experience derived from social interactions shapes knowledge and affects proxy of knowledge (Kolb and Kolb, 2005; Lave and Wenger, 1991). They also believe that learning takes place when one immerses, acquires, maintains and transfers knowledge through the process of social interaction (Contu and Willmott, 2003). The information acquired from situated learning can be more easily connected with the complex memory network to create schematic cues that facilitate information retrieval (Eyler and Giles, 1999, p. 65-66). However, little research has explored how service learning facilitates high road transfer, and how service experience can be high road transferred for knowledge construction.

Identity is an important issue in both service learning and L2 writing. Identity, according to Tajfel (1974), is defined as “an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the emotional significance attached to that membership” (p. 69). The less engaged S-L participants usually take volunteer work as joining an activity physically; their detachment may result in little identity

reconstruction but questioning why “‘we’ have to face (up to) “the stranger” in order to accomplish ‘our’ tasks” (Himley, 2004, p. 418). However, the engaged participants who both physically and emotionally embrace the cultures of the service communities may gradually foster a new identity as a member of the service community. Identifying oneself with the community and participating in community practices shape one’s views about self and the world (Wenger, 1998). Therefore, participants’ engagement in the community and perception about themselves in the community affects their construction of the “autobiographical self” as well as the “self as author” (Ivanic, 1998), which sway writers’ intertextual perspectives, textual decisions and rhetorical moves.

In order to explore S-L influence on identity development, Jones and Abes (2004)

investigated eight participants who had done their community services for 2-4 years before the research. The result shows that S-L experience enhances participants’ development of a “caring

self” and “self-authorship.” That is, engaged participants were enabled to reflect their self in relation to the others, to commit themselves to socially responsible work, and to develop their positions and values without being affected by others.

Besides the formation of a caring self and self authorship, Powdermaker (1966), from the perspective of anthropology, also indicated that on-site work encourages participants not only to be an “outsider” by researching the unfamiliar but also an to be an “insider” by participating in the unfamiliar to make it familiar. Although a number of L2 writing researchers have

discussed identity and found its influences on writing in various aspects, none of them have studied how the identities rising from S-L experience affect EFL writing.

In this present study, I attempt to explore the impact of S-L on Taiwanese students’ writing. My research questions are:

1. What is the socio-cognitive impact of S-L on experience transfer in EFL writing? 2. What does S-L rhetorically impact identity construction of EFL writing?

3. Method

3.1 Setting and Participants:

A qualitative study was conducted in a national university in Taiwan1 where 2 credit hours of community service, at least 18 working hours within one semester, are compulsory for all the undergraduate students. Participants in the present study (N=26) were students taking an English writing course incorporated with service learning. It was an elective course available to all the undergraduate students from different disciplines. Most of the participants were

sophomore and junior students from schools of Social Sciences, Education, and Humanities. Those who successfully completed the course could receive two credits for both College English and community service (18 working hours). Participants could freely choose

community volunteer services within or beyond the list of non-profit organizations provided by the school2. They could either team up with peers or work individually. Besides doing

community services after school, students learned academic English writing in the class. The curriculum was designed based on Deans’ (2000) rationale of “Writing about the Community.” Students were required to complete three writing tasks, i.e., narration, comparison/contrast, and argumentation papers, during a semester. No specific writing topics were assigned to students for the three writing tasks except that they should be composed based on writers’ service-related experience. The writing instruction mainly covered academic writing conventions and rhetorical strategies commonly used in the three writing tasks/modes, such as brainstorming, topic sentence, thesis statement, supporting points, transition, coherence, style, logic, voice,

and organization. 3.2 Research Design and Data Collection

1

It is competitive to enter a top-tier national university in Taiwan. Usually students who are accepted by such a university have medium to high English proficiency.

2

The school’s suggested non-profit organizations for students’ service learning can be found at: http://osa2.nccu.edu.tw/~activity/service-learning/certificate.html

As a teacher researcher, I tried to fairly treat the engaged and unengaged S-L participants in order to minimize inappropriate implications. I kept a teaching log to jot down my

observations about and interactions with the students to maintain my research sensitivity. A total of 15 diary entries were recorded. I consider my status as a teacher researcher appropriate because the impact of service learning is intricate and impalpable, which can be affected by self perception, the nature of community services, participants’ personalities, the quality of interaction and other complex factors; the same services may lead to different effects on individuals. Without close observation and interactions with participants in the same context, researchers can hardly capture students’ negotiations nor perform in-depth analysis.

Among students’ three writing tasks, I only collected the latter two, i.e., the

comparison/contrast and argumentation papers, because I was concerned that students might not have gained enough service experience while working on the first writing task. A survey (see Appendix 1) was conducted in the 7th week of the semester to inquire possible impact of S-L on students’ writing in general. In the survey, for the first five questions, students could choose the top four suitable answers but could only choose one answer for questions 6 to11.

Based on the student survey and my teaching logs, the types of experience transfer and identity construction were to be identified. Furthermore, I broke down these types into more specific guiding questions for interview and students’ journals, such as while composing for task 2 and 3, how topics were generated, and what imagined textual identities s were

constructed or developed (see Appendix 2). All students needed to submit two reflection journals (N= 26x2) respectively after the completion of task 2 and 3 to reflect upon their

writing process in general and respond to specific questions elicited from the survey findings in specific.

To learn more about the impact of S-L on students’ rhetorical level, I analyzed student writings by focusing on their textual identities and their written voice. At the end of the semester, a text-based as well as semi-structured interview was conducted.

3.3 Research Procedure:

Regarding research question one on the impact of S-L on EFL writers’ experience transfer, I firstly recognized students’ difficulty in cognitive transfer from students’ complaints during in-class discussions and office hours. To learn more about how students conceptualized their service experience and turned it into ideas for writing, I scrutinized my teaching log, survey results, students’ journals as well as interview results and then identified the types of

experience transfer.

Regarding research question two on how S-L mediates in EFL writers’ identity

construction, I first, based on the survey results, excluded the students perceiving themselves as not a member of the service communities (N=7) because the unengaged participants would have little identity transformation in their writing. Since voice is viewed as the projection of the writer’s textual identity constructed through social-contextual negotiations, some rhetorical strategies and discursive features are viewed as the indicators for identity analysis. For

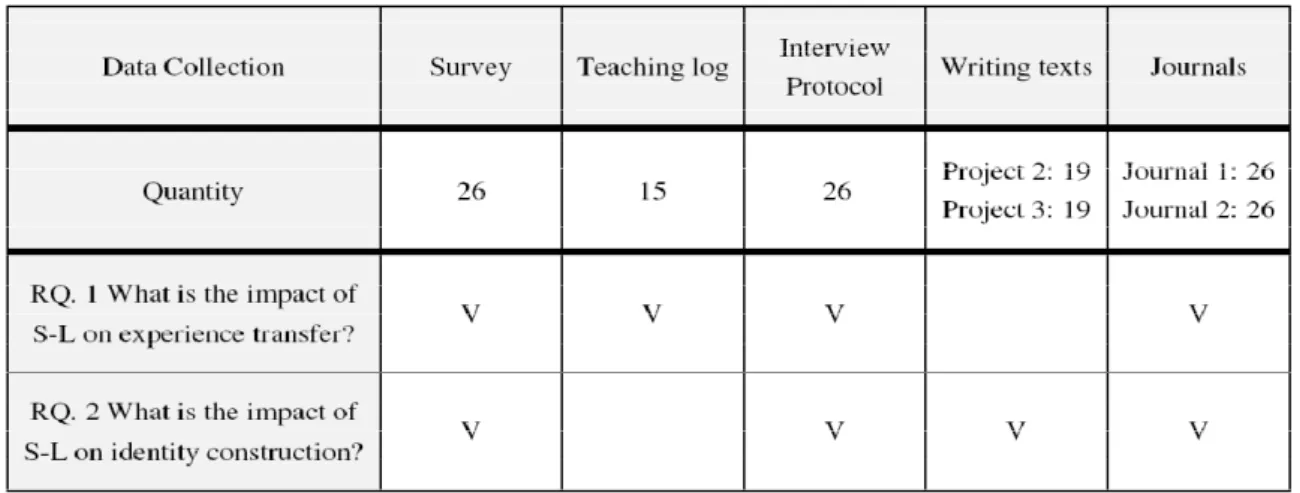

example, how did the writers manage the opponent’s point of views? How did the writers position themselves, such as using the self-referential pronouns, “we,” “I,” and “our”? Other personal pronouns, for instance, “they,” “he,” and “she” are also analyzed according to the texts and contexts. Moreover, the lexical and syntactic choices that can position the writers were also analyzed based on Ivanic and Camps’ (2001) framework of identity analysis, for example, “using generic or specific nominal reference, using personal or impersonal ways of referring to people, using nominalization for processes rather than full finite verbs, using active or passive verb forms, with or without mention of agents, placing topics in subject, object, possessive or circumstantial roles in clauses” (p. 14).Two trained reviewers, who were graduate students in TESL, read only the engaged students’ writings (N=19x2). They marked the identity cues in texts according to Ivanic and Camps’ framework and commented on those students’ identities within the texts. After comparing the reviewers’ comments, I analyzed the students’ written texts based on Ivanic and Camps’ framework again. The textual analysis of identity, then, was triangulated with students’ interview protocols and journal reflections. Research questions and data collection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Research questions and data collection

3.3 Survey results:

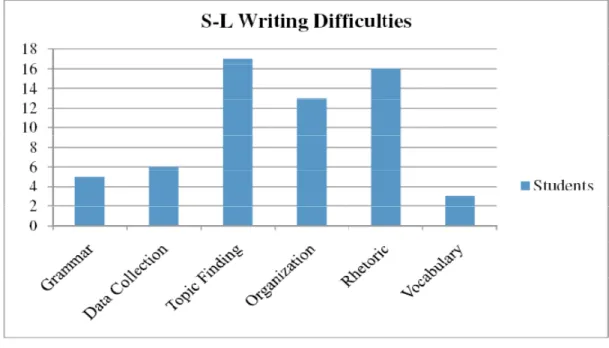

The survey shows the kinds of difficulties that student experienced in their writing and the impact of S-L in their writing process. When asked about the difficulties that they encountered in writing according to their service experience, “finding topics based on service experience” were chosen by 17 students (65%) (see Figure 1). Eighty one percent of the students (N=21) agreed that this S-L-based writing course helped them to transfer daily life experience into knowledge for writing. When asked question 4, “What is the impact of S-L on my writing?,” 77% of the students reported that they are prompted to transfer daily life experience; 73% of the students perceived themselves as a member of their service communities, and 88% of the students indicated that service experience allowed them to obtain first-hand data and hands-on experience (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 The impact of S-L on writing

4. Findings and Discussion 4.1 Learning as transfer

The majority of the students (88%) reported that obtaining first-hand data and hands-on experience is the major impact of service learning. To be more specific, this personal and social involvement allows students not only to make transfer in experience (77%) but also to foster a new identity (membership: 73%). Learning takes place in everyday practices, and knowledge is constructed through the transformation of experience (Kolb, 1984; Kolb and Kolb, 2005); however, daily life experience does not transfer to knowledge spontaneously. One of the challenges that my S-L students encountered is how to conceptualize their service

experience in ways to find topics for their writing. Although some students reported that their service experience facilitated topic finding and idea generation when the cues elicited from service experience were manifest to them, many students (65%) reported difficulties in topic findings. Writing based on service experience may either facilitate or constrain topics for

0 5 10 15 20 25

Q 4. What are The Impacts of S-L on My Writing?

writing. Types of services and chances of social interactions also affect students’ topic finding. Most of the volunteer jobs offered by the communities to my S-L students are chores for part-time and temporary, such as packing, distributing flyers, data entry, filing, or translation. The mechanical nature and no-brainer tasks make experience transfer an esoteric challenge. To help students transfer their service experience, I introduced tagmemic questions in class (Young and Becker, 1965) and adopted the strategy of guided questioning (King, 1994), which prompts students to explain, infer, justify, speculate and evaluate ideas, questions such as “What would happen if…?” or “Why is … important?” (p. 340).

The students’ experience transfer is categorized into the following four types: disconnection, connection, negotiation and invention.

4.1.1 Disconnection

(Student A: a junior student from the department of Journalism, volunteering in Taiwan Foundation of the Blind as a story reader)

Student A completed her comparison and contrast paper by contrasting animal therapy and medical therapy. However, this paper has little to do with her service experience. In an

interview, student A told me that she had very little chance to interact with the employees because what she was assigned to do was to pick storybooks and read and record the stories at home. In her journal 2, she admitted the difficulty in finding an appropriate topic for her paper, “…actually the paper was unrelated to what I did…it was hard for me to select a persuasive topic because I couldn’t find anything to compare based on what I did in the Foundation” (Journal 2, Student A). Without looking for help from the teacher, student A failed to write her paper based on her service experience.

4.1.2 Connection

(Student B: serving in an animal shelter to help take care of stray dogs and solicit them at the animal adoption fairs.)

Student B came to see me during my office hour to discuss what to write about for her argumentation paper. The following is the excerpt from my teaching log.

Student B: I have no idea what to write for my Argumentation paper. Teacher: What have you observed in the stray animal adoption fair?

Student B: Many people stopped by to take pictures with the cute puppies, but very few really adopted them.

Teacher: What do you think?

Student B: I don’t know… I think… life is unfair. Some popular breed dogs enjoy luxurious cares and attentions from their owners. But many mixed dogs with unattractive appearance are abandoned or suffering from not finding a good home.

Teacher: It’s a good point for your argumentative essay (Teaching log, Entry 14). Later, in her argumentative essay, student B successfully argued that the government should not only enforce education about animals and humanity but also control the pet market by imposing extra tax on those who purchase pets from pet shops but financially support those

who adopt animals from the shelters. Through discussion, student B connected her service experience observed from the animal adoption fair with her prior knowledge about unfair life. The experience acquired in one context (S-L) transfers to another context (writing) without too many efforts of negotiations or alterations is called connection.

4.1.3 Negotiation

(Student C: a senior student from the department of Japanese, working in National Youth Commission as a translator.)

Student C knew what he wanted to write about, but he had trouble to negotiate the information obtained from service with the writing assignment.

Student C: … While translating their website from Chinese to Japanese, I obtained a lot of governmental information about visa of working holiday in Taiwan. I wanted to contrast it with Japanese policies and promotion strategies, but it’s difficult to find documents of working holiday from Japanese government.

Teacher: Why are you interested in the topic of “working holiday?”

Student C: I love travel, and I found traveling with a travel visa makes great differences from traveling with a visa of working holiday.

Teacher: How about contrasting differences between the two travel statuses? Student C: Yes. Thank you (Teaching log, Entry 5).

In this case, student C cognitively negotiated the means to achieve his goal. He negotiated between what he wanted to write about and what he could actually write with the available resources. Thus, his transfer from the S-L context to the writing context was largely shaped and resituated in order to complete the task. With the teachers’ help, finally he succeeded in his negotiation.

4.1.4 Invention

(Student D: a junior student volunteering as an English-Chinese translator at the World Vision where families financially sponsor kids from the disadvantageous all over the world.)

In an interview, student D shared with the teacher her topic finding process when writing her argumentation paper.

Student D: After reading and translating the letters, I would like to follow up the little boy’s life in his country, Congo, and the ongoing civil war he mentioned in his letter. I tried very hard to search the internet news and the related information, but I was very disappointed. I couldn’t find anything from our media.

Teacher: So, what did you do?

Student D: I struggled so much and I was so disappointed that our media didn’t report much about the third world. So, I decided to argue whether our media and newspapers are internationalized enough. Should media report only the news which has “high stake” to our country? Should media be interests-orientated? (Interview, Student D)

The difficult inquiry process itself was recognized as something meaningful to student D after she experienced frustration in her research. Student D, through a critical invention process that went beyond what she had planned to do, successfully made the cognitive link to ground her argumentation paper on her service experience.

Student A’s failure to connect her writing to her service experience may result from her limited interactions with people in the service site and her lack of experience in recognizing meaningful representations generated from experience. However, student B, C and D could conceptualize and transfer service experience to the writing contexts with or without assistance. Writing connected with S-L made these students recognize meaningful chunks of information from daily life experience, therefore it prompts students’ high road transfer, involving implicit learning, cognitive negotiation, critical invention, and knowledge construction.

4.2 Learning as acculturation

Contu and Willmott (2003) conceived service learning as becoming members of the “community” in which individuals learn through acculturation, through engaged participation. Community services allow participants to have both cultural exposure of and social

interactions with the service communities. The interplay of the cultural and social factors facilitates the transformation of one’s values, perspectives and interpretation of the self and the world. With hands-on experience and first-hand data, hence, the engaged S-L participants usually, consciously or unconsciously, derive hybrid perspectives as insiders and outsiders of their service communities. The insider perspective stems from S-L participants’ observations and familiarity with the service communities, which allows the S-L participants to see the aspects of the communities that are not available to outsiders. Whereas, the outsider’s identity allows S-L participants to analyze the service-related issues from a more detached position.

Based on the data, S-L participant writers can be grouped into two types, those with a coherent textual identity and those with a incoherent textual identity. The followings are examples for illustration.

4.2.1 Coherent identity

(Student E: a junior student of Sociology, working as a teaching assistant at an orphanage called Bethany). In her comparison and contrast paper, student E identified the differences between kids with parents and orphans at Bethany.

... When everything comes to Bethany, they are totally different…There are about 70 children in Bethany and they need to share 9 rooms and fifteen social workers. In other words, every social worker takes care for 6 to 7 children, and every kid in Bethany shared their living space to each other with little privacy. Furthermore, kids need to leave

Bethany after they graduate from high school and start to make life by themselves. Bethany helps the children to obtain a temporary job as they are in 2nd grade of senior high school. Thus, about 70 percents of children choose to study at vocational schools instead of regular high schools and get into labor market while same-age children study in the university (Student E, Comparison/Contrast).

To make her contrast more academically appropriate, Student E adopted the third person’s perspective to examine the system of and practice in the orphanage. Her insider’s identity allows her to observe details of the orphanage, and her outsider’s identity enables her to discern the divergences between kids with and without parents. Student E described her exigency about contrasting the welfare of orphanage in her journal one, “Through the service learning, I

started to know the fact instead of just reading it from books. And I was angry about why government cannot provide more resources to help the kids. ..” Even though Student E was “angry” as an insider about deficient resources, she discussed the issue by depicting the contextual details and using numbers and present tense. She refrained from her insider’s emotion but consistently adopt the outsider’s authorial identity to reveal the inside story.

However, insider’s identity and attachment may backfire, leading to unprofessional voice or reinforce personal prejudice. Unskillful EFL writers who lack rhetorical strategies in controlling over their hybrid identities may produce choppy or inconsistent voice. 4.2.2 Incoherent identity

Volunteering in a retirement home for visiting clients and reporting their needs, Student F argued for the legalization of euthanasia. However, her hands-on experience and involvement hinders her from making a coherent voice.

…[1]Religious people think that nobody could strip off the others’ lives which are given by God. But who cares about the thoughts of the sick and their families?.... Take Mr. Yang, I served for, for example, he knew he couldn’t recover and considered himself a burden for his children. He lived so unhappy and often wished to die soon…why people couldn’t decide how long they want to live?...If God loved Mr. Yang, why it made Mr. Yang’s live so hard? If God loves those terminally ill patients, why God doesn’t make them die

peacefully? If we respect life, shouldn’t we respect the lived to make their own decision?... Nobody could strip one’s life is right. But we also have to think about the patient’s own thought. …[2] To consider the medicine resources, the terminally ill patients cost the majority of the medical resources. They are wasting the public resources in the society. The government should do our utmost to help those who can be cured but not dilapidate public medicine resources to the terminally ill patients… (Student F, Argumentation). In the first paragraph, Student F sounded like Mr. Yang’s family or friend. She avidly spoke for his rights by using a series of rhetorical questions. As an insider of the caring

community, she expressed strong emotions intuitively on this controversial issue. However in the later discussion in the second paragraph, she sounded like a detached outsider and

unconsciously used “our” to align her position to that of the government or of a third party. Unlike Student E who maintained coherent identities in response to the writing needs, Student F juggled between the identities of the “emotional self” and the “academic self” and “outsider and insider.” Her multiple perspectives from hybrid identities, unfortunately, interfered with the textual coherence and projected a subjective and unprofessional voice.

One thing is noteworthy while analyzing EFL writers’ voice/identity based on Ivanic and Camps’ (2001) identity analysis method. As an EFL writer, Student F lacks rhetorical skills to appropriate her voice. Because Chinese, her mother tongue, has no tense marker on verbs as in English, Student F made tense errors in her English writing unconsciously. In an interview, I asked her , following (Ivanic & Camp, 2001), whether she attempted to create knowledge or to voice the “truth” by deliberately using present tense and whether she rhetorically picked the evaluative words, such as “wasting” and “dilapidate” to express her position or value. Student F said she did not pay attention to tense when she was writing, and she used present tense mindlessly without the intention of voicing truth. Besides, she looked up dictionary for English words to help express her opinions, but among the suggested synonyms, she could not decide which one was more appropriate. She said, “usually I pick the one which seems right and looks difficult” (interview, Student F). In other words, Student F’s detached, cold tone in the second paragraph may result from her limited English proficiency and immature rhetorical strategies. Therefore, I would like to argue that EFL writers’ voice and discursive choices should be used with caution to infer their textual identities.

5. Conclusion:

L2 writing instruction in general emphasizes the practice of low road transfer (writing skills) but draw little attention to high road transfer. High-road transfer that affects one’s ways of seeing reasoning, organization, and interpretation encourages the development of expertise (Bransford, Brown and Cocking, 2000). Incorporation of service learning into writing

instruction offers situated learning which requires the practice of experience transfer. Thus, writing can be raised from the level of language practice to a process of knowledge making.

Service learning impacts EFL writers’ experience transfer and identity construction. Hence, writing instruction wedded with service learning encourages learning of transformation as well as acculturation. Moreover, service learning and writing are reciprocal. The service experience broadens the spectrum of topics and materials for student writers, enriches their perspectives and hybridizes their textual identities on one hand.On the other hand, writing requires writers to cognitively link service experience to their existing knowledge, which helps reformulate information and reconstruct the existing knowledge. Writing also encourages students’ ethnographic inquiry as well as community participation.

To help students with experience transfer, besides idea prompting questions, teachers can encourage students’ self reflection, group discussions, brainstorming, and reading. S-L students, while working on-site, should be observant to details and actively interact with people in the community. Teaching S-L-based writing courses, teachers may need to emphasize writing ideas of transition, coherence, voice and academic writing style in order to help L2 writers construct a coherent textual identity.

Since it takes time for one to acculturate into a different community, the positive impact of S-L on writing requires students of patience and practice. Therefore, more longitudinal

different courses to facilitate experience transfer, and how experience transfer benefits learners’ learning are the issues that need further exploration.

Notes:

1. It is competitive to enter a top-tier national university in Taiwan. Usually students who are accepted by such a university have medium to high English proficiency.

2. The school’s suggested non-profit organizations for students’ service learning can be found at:

REFERENCES

Astin, A. W., Vogelgesang, L. J., Ikeda, E. K., and Yee, J. A. (2000). How Service-Learning Affects Students. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, University of California.

Batchelder, T. H. & Root, S. (1994). Effects of an undergraduate program to integrate academic learning and service: Cognitive, prosocial cognitive, and identity outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 341-355.

Billig, S. H. (2000). Research on K-12 school-based service-learning: The evidence builds. Phi Delta Kappan, 81, 9, 658-664.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L. & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning with additional material from Donovan, M. S., Bransford, J. D. and Pellegrino, J. W. (Eds.), Committee on Learning Research and Educational Practice. National Academy Press: Washington.

Bringle, R. G. & Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 2, 112-122.

Bringle, R. G. & Hatcher, J. A. (1999). Reflection in service learning: making meaning of experience. Educational Horizons. 179-185.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. American Educator, 18, 1, 32-42.

Carson, J. E., Carrell, P. L., Silberstein, S., Kroll, B., & Kuehn, P. A. (1990). Reading-writing relationships in first and second language. TESOL Quarterly, 24, 245-266.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.) Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glasser, (pp. 453-494). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Contu, A. & Willmott, H. (2003). Re-embedding situatedness: The importance of power relations in learning theory. Organization Science, 14, 3, 283-296.

Dean, T. (2000). Writing Partnerships: Service-Learning in Composition. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Davi, A. (2006). In the service of writing and race. Journal of Basic Writing, 25, 1, 73-95. Eyler, J., Giles, D. E. & Braxton, J. (1997). The impact of service-learning on college students.

Eyler, J. & Giles, D. E. (1999). Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Eisterhold, J. C. (1990). Reading-writing connections: Toward a description for second

language learners. In Second Language Writing: research Insights for the Classroom (Ed.) Kroll, Babara. Pp. 88-101. Cambridge University Press.

Flower, L. (2002). Intercultural inquiry and the transformation of service. College English, 65, 2, 181-201.

Furco, A. (1994). A conceptual framework for the institutionalization of youth service programs in primary and secondary education. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 395-309. Furco, A. (2003). Issues of definition and program diversity in the study of service-learning. In

Studying Service-Learning: Innovations in Education Research Methodology (Eds.). pp.13-33. Shelley H. Billing & Alan S. Waterman. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah: NJ.

Gray, M. J. (1996). Reflections on evaluation of service-learning programs. NSEE Quarterly, 21, 8-9, 30-31.

Gray, M.J., Ondaatje, E. H., Fricker, Jr. R. D. and Geschwind, A. (2000). Assessing Service-learning. Change, 32, 2, 30-39.

Handley, K., Clark, T., Fincham, R. & Sturdy, A. (2007). Presarching situated learning: Participation, identity and practices in client-consultant relationships. Management Learning, 38, 2, 173-191.

Hesser, G. (1995). Faculty assessment of student learning: outcomes attributed to service-learning and evidence of changes in faculty attitudes about experiential education. Michigan Journal of Community Service-learning, 2: 33-42.

Himley, M. (2004). Facing (up to) ‘the stranger’ in community service learning. College Composition and Communication. 55, 3, 416-438.

Heuser, L. (1999). Service-learning as a pedagogy to promote the content, cross-cultural and language-learning of ESL students. TESL Canada Journal/Revue TESL Du Canada, 17, 1, 54-71.

Howard, Jeffrey, P. F. (1998). Academic Service Learning: A Counternormative Pedagogy.

New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 73 21-29.

Howard, J. (2003). learning research: Foundational issues. In Studying

Service-Learning: Innovations in Education Research Methodology (Eds.). pp.1-12. Shelley H.

Billing & Alan S. Waterman. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah: NJ. Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic

writing. Amsterdam: Benjamin.

Ivanic, R. & Camps, D. (2001). I am how I sound: Voice as self-representation in L2 writing.

Journal of Second Language Writing. 10, 3-33.

Jones, S. R., & Hill, K. (2001). Crossing high street: Understanding diversity through community service-learning. Journal of College Student Development, 42, 3, 204-216.

Jones, S. R. & Elisa, S. A. (2004). Enduring influences of service-learning on college students’ identity development. Journal of College Student Development, 45, 2, 149-167.

Kendrick, J. R., Jr. 91996). Outcomes of service-learning in an introduction to sociology course. Michigan Journal of Community Service learning, 3, 72-81.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb A. Y. & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4, 2, 193-212.

Kraft, R. J. (2002). International Service Learning. In Learning to Serve: Promoting Civil Society through Service Learning. Maureen E. Kenny, Lou Anna K. Simon, Karen Kiley-Brabeck, & Richard M. Lerner (Eds.). pp. 297-314.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning : Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Markus, G. B., Howard, J. P. F. & King. D. C. (1993). Integrating community service and classroom instruction enhances learning: Results from an experiment. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 15, 4, 410-419.

Mastrangelo, L. S. & Tischio, V. (2005). Integrating writing, academic discourses, and service learning: Project renaissance and school college literacy collaborations. Composition Studies, 33, 1, 31-53. Ministry of Education in Taiwan (2008).

http://english.moe.gov.tw/content.asp?CuItem=9407&mp=10000

Miller, J. (1994). Linking traditional and service-learning courses: Outcome evaluations utilizing two pedagogically distinct models. Michigan Journal of Community

Service-learning, 1, 1, 29-36.

Morton, K. (1995). The irony of service: Charity, project and social change in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 2, 19-32.

Perkins, D. N. & Salmon, G. (1988). Teaching for Transfer. Educational Leadership, 46, 22-32. Powermaker, H. (1966). Stranger and Friend: The Way of an Anthropologist. New York:

Norton.

Salommon, G. & Perkins, D. N. (1987). Transfer of cognitive skills from programming: When and how? Journal of Educational Computing Research, 3, 2, 149-169.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information. 13, 65-93.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

S-L Survey: Incorporating Service Learning into Academic Writing Name:______________________

*本問卷調查純為個人研究興趣所需, 學生的回答資料將僅限於學術研究所用, 所有私人 資料絕不公開, 學生的問卷答覆也不影響學期成績, 請放心誠懇作答。

*1-5 請選擇最恰當的答案並按程度排列 (Choosing the most appropriate answers only and rank the answers by degree)

1. 根據服務的經驗寫作, 我感到最困難的部分是 (When writing based on service learning, my major difficulties come from):

a. 文法 (grammar)

b. 根據服務經驗找寫作題目 (finding topics based on service experience) c. 組織 (organization)

d. 收集/查資料 (data collection/research) e. 修辭 (rhetoric)

f. 字彙 (vocabulary)

2. 在寫作方面, 我最有收穫的是 (Taking this writing course, I have benefited a lot from) a. 寫作概念 (teaching topic sentence/thesis statement)

b. 找寫作靈感 (invention-free writing) c. 組織 (organization)

d. 文法 (grammar) e. 修辭 (rhetoric) f. 邏輯 (logic)

g. 轉折連慣性 (transition & coherence) h. 閱讀資料 (reading secondary sources) i. 校稿 (peer-editing)

j. 字彙文法 (vocabulary & grammar)

k. 轉換服務經驗為寫作知識 (transferring service experience into knowledge for writing)

3. 為了寫作的需要, 我在志工服務時會如何蒐集相關資料(To complete the writing tasks, when I was volunteering, I would collect data through):

a. 上網收集資料 (research on the Internet) b. 仔細觀察周遭 (observing carefully)

c. 與服務對象或其他工作者交談 (communicating with the people there) d. 做筆記 (taking notes )

e. 寫日記 (keeping journals)

f. 與相關專業人士討論 (discussing with experts)

g. 在義工服務處收集可用的資料 (collecting data at the service site) h. 其他 (others)___________

4. 結合志工的寫作課程, 對我在寫作上的影響是: (Service learning has impacted my writing in):

a. 使我提高寫作興趣 (boosting my motivation for writing)

b. 使我更有能力將日常生活經驗轉化成有系統的知識 (making me more capable to transfer daily life experience into knowledge)

c. 使我感覺上屬於這個服務單位的一份子, 因而對議題產生更深刻的見解(increasing my sense of community membership which helps generate insights for my writing) d. 使我可以收集到一手資料, 並且可以親身觀察體驗我感興趣的寫作議題 (enabling me

to collect first-hand data and observe issues in person)

e. 使我有多元(次)文化瞭解與包容力,可以更客觀的看待問題 (enabling me to understand and tolerate multi/sub-cultures);

f. 使我有公民責任感 (enhancing my sense of citizenship) g. 使我產生寫作的靈感 (helping with invention in my writing)

h. 使我更能應用寫作技巧並提升寫作的能力( I can better apply my writing skills and improve my writing ability).

5. 我是如何找出我的CC寫作題目 (I found my topic for the CC writing ) a. 透過討論 (through discussion)

b. 透過大量閱讀 (through readings)

c. 根據服務的觀察與經驗 (based on service observation and experience) d. 根據收集的資料 (according to the collected data)

e. 根據一般普遍性的寫作題材 (according to popular topics for writing) f. 以前的個人經驗 (based on prior experience)

g. 個人興趣 (based on personal interest)

**6-11 以下為單選題 (Choosing one answer only):

6. 查到的資料若有疑問, 我會與服務單位有經驗的人士或服務對象確認資料正確性? (If I have questions about the information that I collected on the service community, I would check it with the people at my service site?) YES/ NO

7. 在服務過程中, 我對我的工作很投入, 我感覺是屬於這個服務單位的一份子?

(I am engagged in my volunteer service and feel like I am a member of the service community?) YES / NO

8. 在第二篇寫作過程中, 我感覺是用何種身份寫作 (When I was composing my second writing task, I took the stance of)?

a. 學者專家 (experts) b. 學生 (students) c. 局內人 (insider) d. 局外人(outsider) e. 其他 (Others)_______ (please identify)

9. 透過服務寫作, 我更有能力將日常生活經驗透過寫作轉化為有系統的知識

(Through service learning-based writing practice, I am more capable of transferring daily life experience into knowledge?)? YES / NO

10. 在探討寫作議題前, 你是否已有自己的預設立場 (Had you had your own position before you started exploring the issue?)? YES/ NO

11. 如果我的寫作立場被該領域的專家質疑, 我會因為質疑而改變立場嗎 (If an expert in the service community questions your writing, would you change your position?)?

1. 會改變, 終究我不是專家 (Yes, I am not an expert after all) 2. 有可能改變 (maybe) 因為不是完全確定

3. 可能不會改變 (maybe not)

4. 不會改變, 因為對自己的論述有信心 (No, because I have confidence in my opinions)

Appendix 2

Leading questions for journal reflection:

Please reflect upon the following questions in your journal:

1. How did you come up with the topics for your writing? (brainstorming strategies, personal prior-experience, research interest, service learning influence, etc...)

2. How did you collect data for your writing tasks? (personal observation, library or internet research, interaction with your subjects or people in your service site, note keeping, etc...)

3. What have you done to complete the writing tasks? (looking up dictionaries, library/internet research, reading samples, discussion, tutoring with peers/tutors/TAs, re-examining collected data with service site subjects or agents, drafting, etc...)

4. How does the service learning experience affect your first and second paper?

5. What are the difficulties that you encountered when writing the first and the second paper? (finding topic, generate ideas, searching information, expressing ideas with appropriate

vocabularies, grammar, organization, introduction, thesis statement, topic sentence, transitions, logics, etc...)

6. Which class activities facilitated your writing? (free writing, peer review, instruction of features of narration, instruction of organization, transition, introduction, rhetorical style, logics, etc.)

得報告

日期: 101 年 2 月 30 日

一、 參加會議經過

世界應用語言學大會 (Association Internationale de Linguistique Appliquee, AILA) 是一個兼重理論研究與教學應用的國際知名會議。第十六屆 世界應用語言學大會在北京外國語大學舉辦。與會者眾。會議有許多來自世界 各國的知名學者如:Barbara Seidlhofer, Malcolm Coulthard, Allan Bell, Diane Larsen-Freeman, Icy Lee, Diane Belcher, Ryuko Kubota, Tony Silva

和 Margie Berns. 本次會議主要探討語言、文化與社會在多元化下所產生的改

變或所受之影響,探討題目廣泛,探討的角度從世界英語、社會語言學、言談 分析、語言習得、電腦媒介應用到其他諸多應用語言學的相關議題等,可說是 包羅萬象,內容豐富。應邀者的主場演講題目如下:Anglophone-centric attitudes and the globalization of English, Applying linguistics in forensic contexts (ESP), Discourse analysis and the interpretive arc: A new approach to media texts, Saying what we mean: Making a case for

計畫編號 99-2410-H-004-202- 計畫名稱 服務學習對學術英文寫作籌創過程之影響 出國人員 姓名 劉怡君 服務機 構及職 稱 國立政大學 外文中心助理教授 會議時間 100 年 8 月 23 日至 100 年 8 月 28 日 會議地 點 Beijing, China 會議名稱 (中文)

(英文).16th World Congress of Applied Linguistics, Association Internationale de LingusitqueAppliquee (AILA),

發表論文 題目

(中文)

為地球村與國際化傾向勢不可擋,將促使語言、文化與社會朝更多元的方向發 展。多元化與日益普及的電腦科技溝通媒介將在語言教學與語言學習上產生極 大的影響。實踐社群 (community of practices)與情境學習 (situated learning)的概念也著重於互動與雙向互惠的架構上而不再是單向的邊緣性的 合理參與(Peripheral legitimate participation)。在寫作教學方面的相關討 論有寫作與電腦 literacy 的發展,學生寫作認知的啟發與聽說讀寫的交互影響。 除此之外,多元檢測的方法與作文批閱的回饋(error feedback)與修正(error correction) 的討論也如往年一樣熱烈。在會議結束後,主辦單位舉行了中國 傳統風格十足的晚宴。 與會學者專家齊聚一堂,在輕鬆愉快的氣氛中交流心得 感想。這次的會議參與碰到了一些舊識的學者友人,大家相見甚歡,在交流中 獲益良多。

二、 與會心得

我聽了許多有趣的口語報告,精華紀錄如下。Wudthayagorn, 和 Holiday 的 “Blog, portfolios and peer comments for learner autonomy and motivation in an Engish writing course.” 報告內容強調 Blog 對學習者在自學上可產生的效果,如: self-directed, collaborative, critically reflective 和 motivation. 兩位報告者根據 他們的研究發現,Blog 有助於學生在寫作上有多方面的進步, 如: spellings, word choices, grammar, organization, learning community practices, metacognitive skills.

Diane Potts 在 “Multimodality, semiotic register and the

recontextualization of knowledge”的報告中附議 Holiday 的看法認為知 識是公共自治體的概念。也提出知識是移動性的,語言不是一種獲取知識的 工具,而是知識既存有的型態,因此學習者必須恰當的使用 text 來傳播或創 造知識。

Kawashima, Tomoyuki 報告了他在 EFL 學生學習口語上的研究發現。在他 的實驗班級中,多元口語發音被強調為是真實世界中正常的英語使用常態現 象。將世界英語的概念融入口語教學中,可以讓學生了解真實世界中英語使 用的情況。當非母語發音的腔調被合理認同後,Kawashima 發現他的 EFL 學 生在學習的態度與動機上產生了正面反應。學生們可以正面接受自我英語使 用上的不完美,在口語表達上,學生的學習態度因此更積極也更有信心,英 語使用的焦慮感顯著降低。

Stapleton, Paul 發表了 “Writing in an electronic age: A case study of L2 composing processes and shifting cognitive resources.” Stapleton 重申寫作是一個遞歸過程,他已 Flower 和 Heyes (1981)年提出 的寫作認知模式為利基點,突破以往使用 think aloud protocol 的研究方法

發現思維產生的過程就是寫作的過程。而寫作者所使用的工具會對其思維過 程產生影響。

此外,如 Margie Berns 在 “Chinese-ness and world Englishes”報 告中探討了中式英語的現象,並且以哈金的小說寫作風格作為中式英語的存 在與廣泛被認同的觀點檢視如何界定中式英語,是否有必要界定中式或非中 式英語,界定中式英語的困難與挑戰,和世界英語對地區性英語使用上的影 響。Zhou, Yan 在 “Teacher learning in diversified classroom contexts” 報告中提出五點建議給教師培育者:learning by examples, learning

through mentoring system, self-reflection motivating 以及 supporting community.

三、 建議

看到北京努力爭取到了籌辦世界應用語言學大會的機會,並使出渾身解 數,盛大的舉辦。筆者深覺台灣的學術界因為研究壓力與籌辦大會手續過程 繁瑣、報帳困難、經費有限等不利的因素,使得這種國際型的大會很難在台 灣主辦。如果政府希望鼓勵學術風氣,帶動研究風潮,吸引外籍學者來台並 對台灣的研究環境多所了解,那麼上述的局限應該有配套的改變。並且鼓勵 國際會議在台舉辦。 此外,大陸有許多優秀學者基於台海兩岸政治對立的問題而無法來台從 事學術交流(需要有保人,且手續繁瑣),使得兩岸學術交流緩慢,政府在 學術上的開放政策為德不卒。五、攜回資料名稱及內容

帶回了會議議程與手冊。 裡面有每個場次的時間與內容簡介。同時也拿了 許多講義與作者使用的參考目錄,如: Diane Belcher, “Cultural identity and commitment to bilingual competence” 、Ryuko Kubota, “Political economy of language education in a neoliberal and globalized world: critical engagement in ideologies”、 Shi, Ling “Paraphrasing and rewriting source texts in student writing”…等等。六、其他

此次行程收穫頗多,尤其是找到自己喜歡的主題與未來可能研究的方向。 在會議中,也認識了來自各國的學者,彼此留下聯絡訊息,使我覺得研究上 多了一些資源與支援。值得一提的是碰上了一些學術界的舊識,大家在休息 時間互相交換心得與感想,彼此打氣與分享,真的覺得這趟旅行除了知識上 是個豐富的饗宴外,在情感與研究動機上也都充滿了電力,真的算是個愉快 又充實的經驗。日期:2012/02/24

國科會補助計畫

計畫名稱: 服務學習對學術英文寫作籌創過程之影響 計畫主持人: 劉怡君 計畫編號: 99-2410-H-004-202- 學門領域: 英語教學研究無研發成果推廣資料

計畫主持人:劉怡君 計畫編號:99-2410-H-004-202- 計畫名稱:服務學習對學術英文寫作籌創過程之影響 量化 成果項目 實際已達成 數(被接受 或已發表) 預期總達成 數(含實際已 達成數) 本計畫實 際貢獻百 分比 單位 備 註 ( 質 化 說 明:如 數 個 計 畫 共 同 成 果、成 果 列 為 該 期 刊 之 封 面 故 事 ... 等) 期刊論文 0 1 100% 本 研 究 計 畫 以 質 性方法執行,觀察 學 生 在 第 二 外 語 寫 作 上 的 籌 創 過 程,為了收集到深 度資料,筆者必須 與 學 生 多 次 面 談。目前該文已經 投 稿 至 Taiwan Journal of TESOL. 目 前 尚 在 審查中,希望可以 受編輯青睞。 研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 1 1 100% 篇 本 研 究 計 劃 在 國 立 臺 灣 科 技 大 學 應用外語, 2010 應 用 語 言 學 暨 語 言 教 學 國 際 研 討 會 (ALLT) 上 發 表 , 頗受好評,也在會 後 與 多 位 專 家 學 者交換心得,並獲 得肯定。 論文著作 專書 0 1 100% 預定在 2012 年底 開 手 著 手 專 書 撰 寫之計劃 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國內 參與計畫人力 (本國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次 國外 論文著作 期刊論文 0 1 100% 篇 預 定 在 暑 假 期 間 可以撰寫文稿,投

研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 4 4 100% 本計畫曾在 2012 年 CELT Conference, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong ; 2011 年 Symposium on Second Language Writing, Taipei, Taiwan; 2011 年 Association Internationale de Lingusitque Appliquee (AILA), Beijing, China; 與 2010 年 American Association for Applied Linguistics (AAAL), Atlanta, GA, USA 國際大會 發表。在會後認識 許 多 對 該 議 題 有 興 趣 的 專 家 學 者,經過交流,讓 筆 者 對 該 議 題 有 更深刻的想法,因 此 希 望 於 年 底 著 手撰書。也有出版 社與筆者接洽,希 望代理出書,這些 都 是 對 該 研 究 計 畫的正面肯定,也 是 對 筆 者 研 究 的 一大鼓勵。 專書 0 0 100% 章/本 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 參與計畫人力 (外國籍) 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 人次

其他成果

(

無法以量化表達之成 果如辦理學術活動、獲 得獎項、重要國際合 作、研究成果國際影響 力及其他協助產業技 術發展之具體效益事 項等,請以文字敘述填 列。) 該計畫陸續在國內外最重要的研討會上發表,都受到廣大的迴響與肯定。已有 國外出版社與筆者接洽,洽談出書事宜,筆者目前準備於年底開始著手撰書計 畫,透過專家學者的交流與書商洽談出書的可能性,肯定了該計畫的深度與重 要性。希望可以順利出版該專書,以在第二外語寫作教學的領域上有所參與與 貢獻。 成果項目 量化 名稱或內容性質簡述 測驗工具(含質性與量性) 0 課程/模組 0 電腦及網路系統或工具 0 教材 0 舉辦之活動/競賽 0 研討會/工作坊 0 電子報、網站 0 科 教 處 計 畫 加 填 項 目 計畫成果推廣之參與(閱聽)人數 0請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況、研究成果之學術或應用價

值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)

、是否適

合在學術期刊發表或申請專利、主要發現或其他有關價值等,作一綜合評估。

1. 請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況作一綜合評估

■達成目標

□未達成目標(請說明,以 100 字為限)

□實驗失敗

□因故實驗中斷

□其他原因

說明:

2. 研究成果在學術期刊發表或申請專利等情形:

論文:■已發表 □未發表之文稿 □撰寫中 □無

專利:□已獲得 □申請中 ■無

技轉:□已技轉 □洽談中 ■無

其他:(以 100 字為限)

本論文已經投稿 Taiwan Journal of TESOL

3. 請依學術成就、技術創新、社會影響等方面,評估研究成果之學術或應用價

值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)(以

500 字為限)

為什麼牛頓可以從日常生活中的蘋果墜落經驗發現重力? 為什麼佛蘭克林可以在自然現 象的風雨中發現電? 為什麼同樣訓練的學者, 有些可以在生活, 教學, 研究中比另一些 學者更容易找尋到有價值的研究契機? 要回答’靈感從哪來,’若從寫作領域探討該問 題,「籌創」 (invention)是重要的切入點。「籌創」簡單來說是研究寫作時所有醞釀、計 畫、構思與發現的行為 (Campbell, 1996, p.212),在第一語 (L1 writing)修辭寫作研究 中佔有重要的一席之地。 雖 L2 writing 研究逐漸有越來越多轉借第一語寫作的探討出現, 如 探 討 作 者 身 份 (identity) 、 筆 調 (voice) 、 讀 者 (audience) 或 權 力 (power) 與 文 體 (genre)等議題, 但「籌創」修辭寫作的探討在國內仍屬鳳毛麟角,對許多第二外語寫作(L2 writing)學者而言這是個陌生的名詞,因為大部分的第二外語寫作研究仍以學生語言與文 化差異或寫作教學與應用為主要研究重心。 根據筆者的觀察, 隨著台灣經濟 M 形化發展, 學生英語素質也逐漸呈 M 形分配。 許多學 生英語程度嚴重落後, 令人擔憂。 但也許有多學生在幼稚園時即接受雙語教育, 在大學 時英語能力令人驚豔。 這些學生已具備良好的文法構句基礎訓練. 在大學的進階寫作訓 練上,可以漸進式加重修辭學寫作概念。 因此, 筆者也樂觀預估第一語寫作研究將被台灣 學者更廣泛應用於第二語寫作研究中,以因應較高英語程度的學生寫作上的需求。 本文除 了突破性分析探討 EFL 學生寫作的「籌創」過程, 同時結合「服務學習」(service learning) 研究,以探索「服務學習」所提供學生真實經驗,存在的情境與社會互動會如何影響寫作「籌種微妙的經驗累積,這些思考的探索是很難透過教與學的方式而獲得的能力。 寫作可以將 生活經驗轉換為知識的概念在寫作研究中雖被寫作學者們談及與肯定 (Flower, 1994; Swinson, 1992), 但並無法被更進一步的具體證明。這方面的探討付之闕如,因為經驗轉 換、知識架構、或籌創起源可以牽涉甚廣, 從社會語言學、認知語言學甚至可以跨足到神 經語言學的領域。這塊尚未被深入觸及的研究處女地卻在寫作學習與教學上有著舉足輕重 的影響。如果寫作「籌創」--靈感與構思的能力被證明可以藉由社會互動經驗與文化的體 驗而增進, 那麼,寫作中的「籌創」過程與強調社會文化互動的教學法,如「服務學習,」 則在未來的研究與教學中應該值得高度重視。