社群網絡與線上社會運動之初探研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Action Online – A Preliminary Study on Social Media Activism on Facebook 社群網絡與線上社會運動之初探研究. A Master Thesis. 治 政 大 National Chengchi University 立 ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. n. a l In Partial Fulfillment i v n Ch Of the Requirements e n g cfor h itheUDegree Master of Art. By Chien, Mingtso. Date: 2010/6. ii.

(3) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. Completing this project has been a journey of self-reflection and discovery. On the way, there were moments of frustration and constant setbacks, but there were also moments of enlightenment and constant warm support from friends and family. This journey has taught me the value and spirit of conducting a research, and it has allowed me to learn more about myself. Many people have been extremely supportive and helpful along the way, and I owe them many thanks.. 治 政 My deepest gratitude goes to my advisor, Dr. 大 Wu, Hsiaomei, who has been 立 extremely supportive and patient, especially when the process was slow, and the ‧ 國. 學. completion seemed so out-of-reach. Dr. Wu, I thank you for having meticulously. sit. y. Nat. appreciated.. ‧. assisted me in the process of writing this thesis. Your kindness is genuinely. io. er. I would also like to thank Dr. Chuang and Dr. Shih. Thank you for taking the time to answer my questions and for your invaluable comments and suggestions.. al. n. iv n C This painstaking process of completing thesis would not have been possible h e n gthe chi U. without continuous support from my family, especially my mother and sister. I thank them for believing in me and encouraging me to stay on track. Finally, I want to thank several friends who have been there for me when I was in doubt of myself and found it hard to proceed. Josh, you have been an amazing friend. Thank you for always believing in me. Lara, Tina, Yiyee, and Inkle, thank you all for helping me to stay focused along the way. I also remember those who have given me a hand with my research. Thank you all. iii.

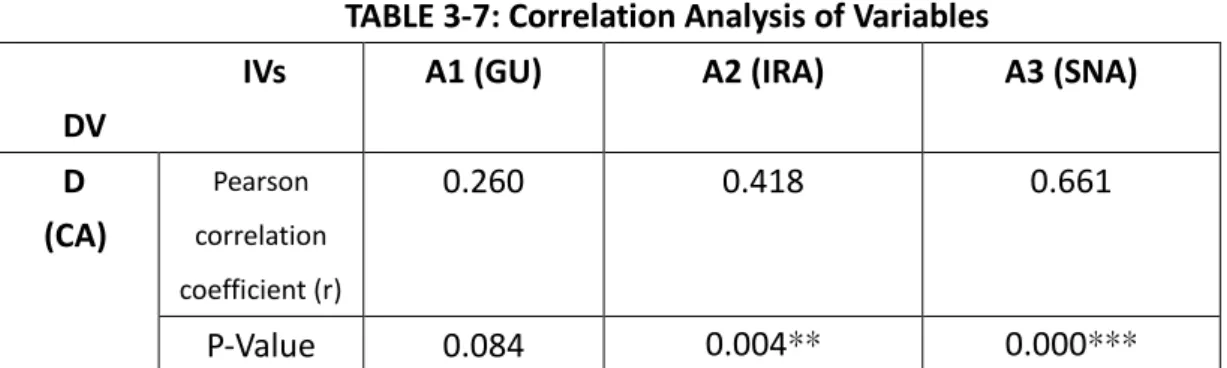

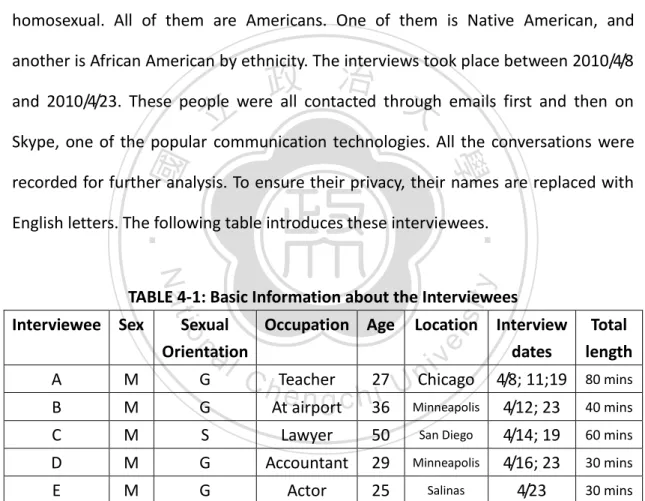

(4) ABSTRACT. This study posits that there is a connection between political action online and activism in the real life. In addition, social ties and networks as well as political knowledge and efficacy play an important role in this connection. Causes, an application on Facebook, was selected for analyzed. A mixed method study was conducted, consisting of two stages. In the first stage (quantitative), a survey was utilized to investigate the correlation between activities on Causes and conventional. 治 政 political engagement. A total of 45 responses were 大gathered using convenience 立 sampling. It was found that there is a strong correlation between action on Causes ‧ 國. 學. and conventional political engagement. For example, information retrieval activities. ‧. are correlated with conventional activism (r=.418, p<.05), and social networking. sit. y. Nat. activities are also correlated with conventional activism (r=.661, p<.05). In addition to. io. er. the survey, intensive interviews (N = 5) were conducted in the second stage (qualitative) to elaborate and clarify the results from the survey as well as to explore. al. n. iv n C new grounds on the significance of networks. Some themes have emerged hties e nand gchi U. from the interviews, including motivations for the use of Causes, Causes as an information channel, potential and problems of Causes, online versus offline activism, affiliation and involvement, political knowledge and efficacy as well as ties and networks. Interview findings concluded that the high correlation between online and offline activism is further specified by the interviewees to be an extension of each form of activism, meaning they are complementary rather than identical.. Key words: social media, political activism, political knowledge, political efficacy, social ties, social networks iv.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements. ii. Abstract. iii. Table of Contents. iv. List of Tables and Figures. vii. CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION. 1. 1.1 An overview 1.2 What motivates this study?. 立. 3 4. 學. ‧ 國. 1.2.1 Positive opinions. 1. 政 治 大. 1.2.2 Negative opinions. ‧. 1.3 Conceptual organization. 1.5.1 Social networking sites. n. al. 1.5.2 Causes and Facebook. CHAPTER 2. 5 7. y. sit. io. er. 1.5 Background. Nat. 1.4 Problem statement. 4. Ch. n engchi U. LITERATURE REVIEW. iv. 8 8 10. 14. 2.1 Social networking sites. 14. 2.2 Social network analysis. 16. 2.2.1 Significance of network analysis. 17. 2.2.2 Networks & ties. 18. 2.2.3 Strength of ties and mobilization. 20. 2.3 Issue information and political knowledge. 21. 2.4 Issue related political efficacy. 23 v.

(6) 2.5 Networking, knowledge, efficacy and participation. 23. 2.6 Theoretical structure. 25. 2.7 Research questions. 26. CHAPTER 3. 27. METHODOLOGY & RESULTS (SURVEY). 3.1 Research subjects. 27. 3.1.1 Proposition 8, its proponents and opponents. 27. 3.1.2 Selection of subjects. 28. 3.2 Sampling and questionnaire design. 30. 3.3 Variables. 31. 政 治 大. 立. 3.3.1 Independent variables. 31. ‧ 國. 學. 3.3.2 Dependent variables. sit. io. 3.5.2 Independent variables vs. dependent variables. n. al. Ch. er. 3.5.1 Demographic data. CHAPTER 4. 37 37. y. Nat. 3.5 Survey results. ‧. 3.4 Data analysis. 36. n engchi U. METHODOLOGY & RESULTS (INTERVIEW). iv. 37 40. 48. 4.1 Background information and new research questions. 48. 4.2 Results. 49. 4.2.1 The interviewees. 49. 4.2.2 Activism on Causes. 49. 4.2.3 Online vs. offline activism. 56. 4.2.4 Political knowledge. 59. 4.2.5 Political efficacy. 60. 4.2.6 Ties and networks. 61 vi.

(7) CHAPTER 5. DISCUSSION. 67. 5.1 Action online and activism in the real life, any differences?. 67. 5.2 Social media activism, any good?. 70. 5.3 Knowledge and efficacy. 71. 5.4 What really influences the level of activism?. 74. 5.4.1 Personal identity. 74. 5.4.2 Personal ties, organizational affiliations and political participation. 76. 5.5 Connection between the quantitative and qualitative results. 立. CONCLUSION. 學. 6.1 Summary of the study. ‧. 6.2 Limitations of the current study. 79 81 83. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 6.3 Research potentials. REFERENCES. 77. 79. ‧ 國. CHAPTER 6. 政 治 大. APPENDIX A: Questionnaire. Ch. n engchi U. iv. 85 90. APPENDIX B: Operationalization of independent variables. 96. APPENDIX C: Interview questions. 98. vii.

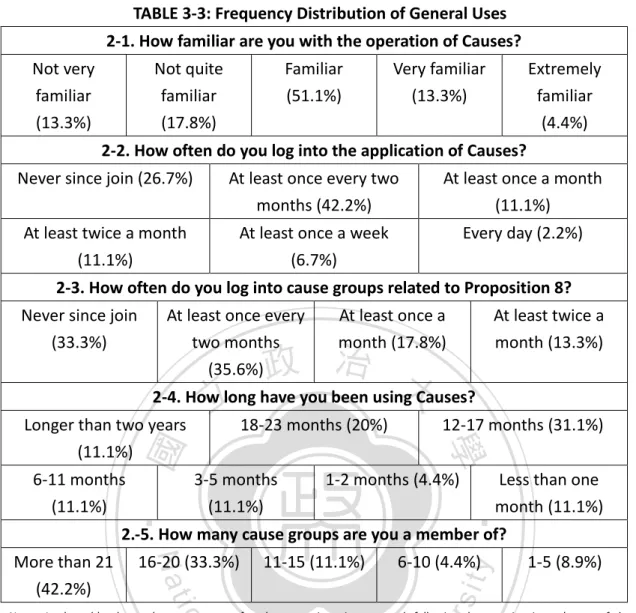

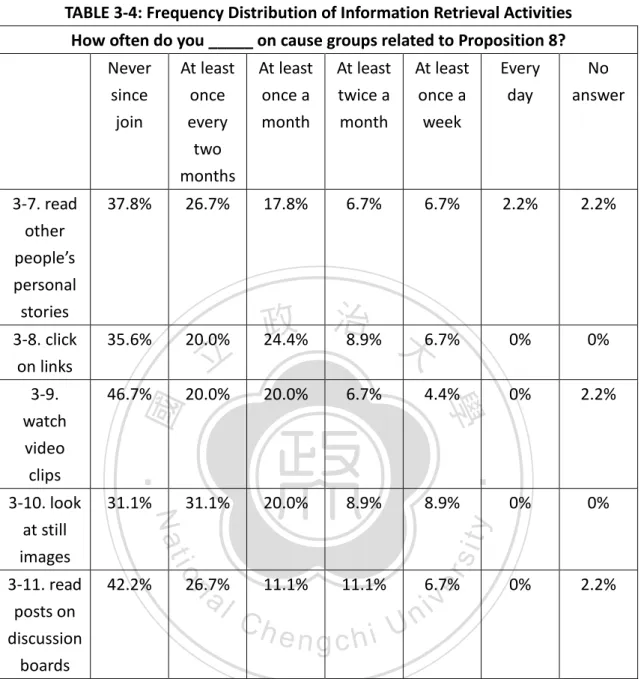

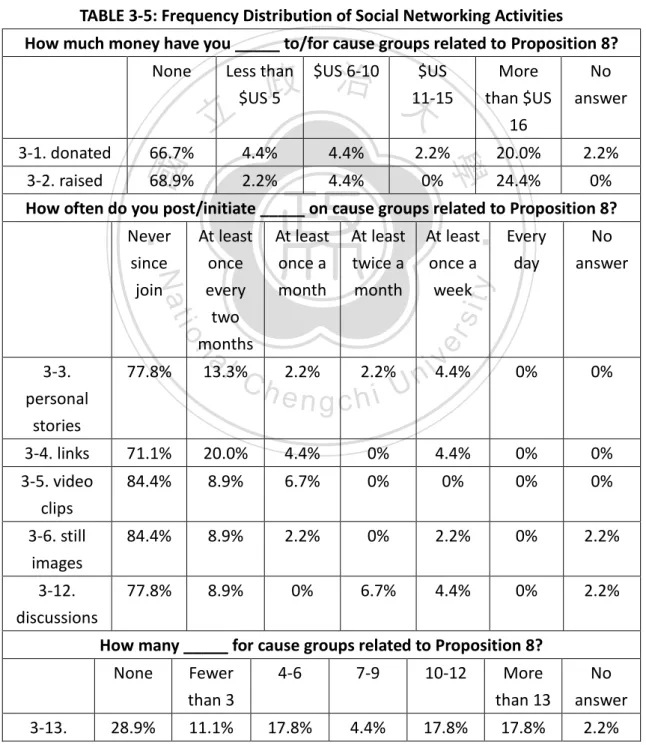

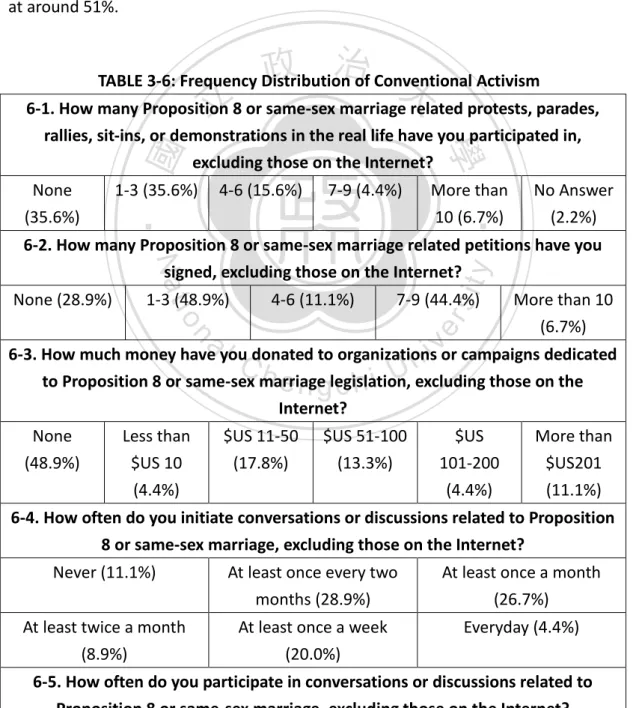

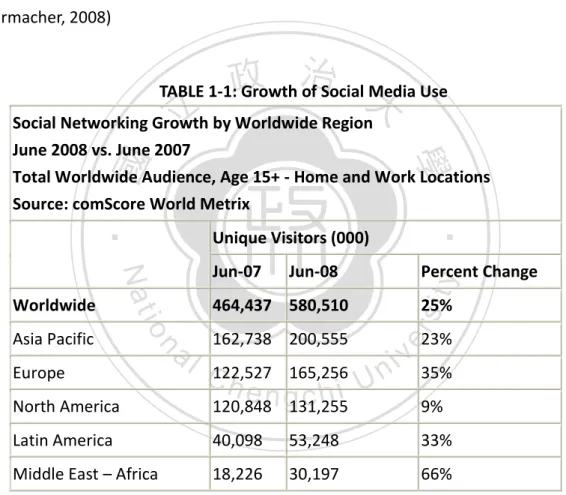

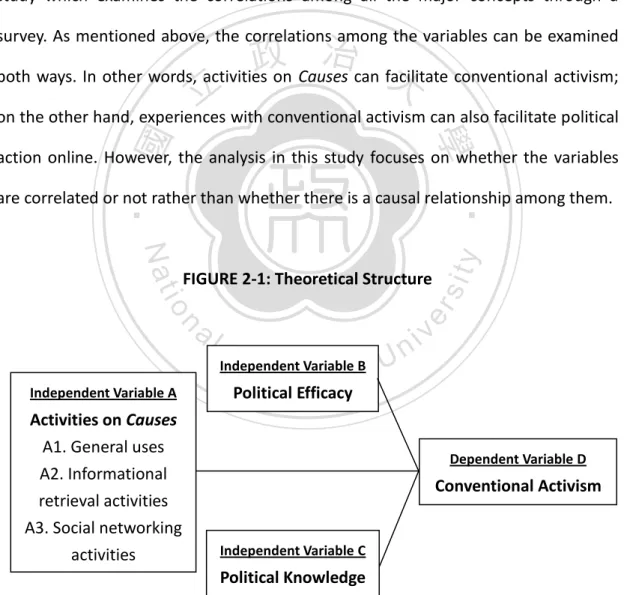

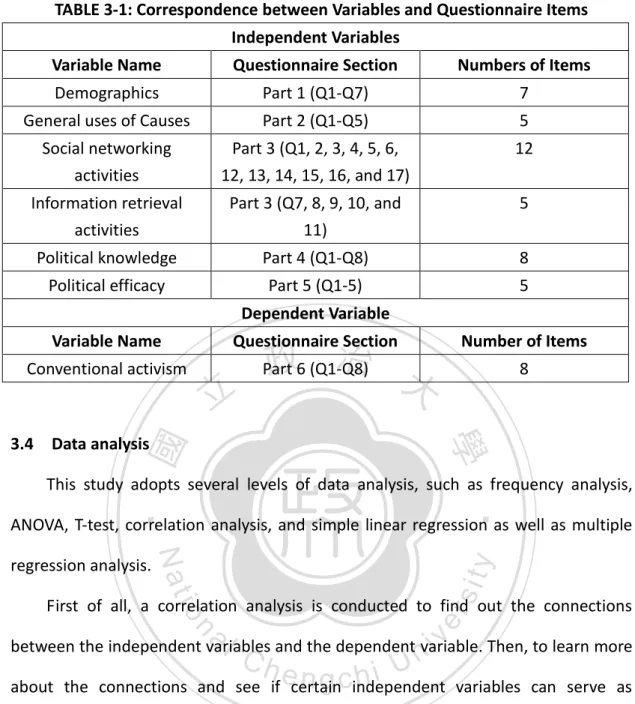

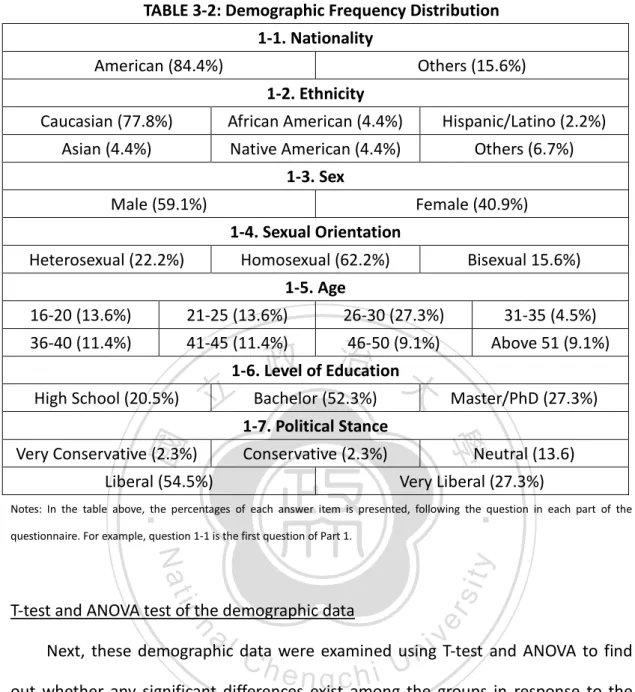

(8) LIST OF TABLES. TABLE 1-1 Growth of Social Media. 9. TABLE 3-1 Correspondence between Variables and Questionnaire Items. 37. TABLE 3-2 Demographic Frequency Distribution. 39. TABLE 3-3 Frequency Distribution of General Uses. 41. TABLE 3-4 Frequency Distribution of Information Retrieval Activities. 43. TABLE 3-5 Frequency Distribution of Social Networking Activities. 42. TABLE 3-6 Frequency Distribution of Conventional Activism. 45. 治 政 TABLE 3-7 Correlation Analysis of Variables 大 立 TABLE 4-1 Basic Information about the Interviewees. 47 49. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. FIGURE 2-1 Theoretical Structure. n. al. Ch. er. io. sit. y. Nat. LIST OF FIGURES. n engchi U. iv. 25. viii.

(9) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. “The proliferation of social-networking sites like Facebook has spawned a new and particularly superficial form of activism. It asks nothing more from participants than a few mouse clicks and makes everyone feel good. But these empty campaigns may not accomplish much, if anything, in the way of social change, and could even distract people from supporting legitimate causes.” By Evgeny Morozov of Newsweek. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 1.1. 政 From治 the magazine 大issue dated June 29, 2009. An overview. ‧. There are various views regarding whether activism online has a value as well as. sit. y. Nat. how it affects conventional activism. Some people (Morozov, 2009; Ma, 2009) think. io. er. such form of activism is meaningless and may even subtract engagement in political activities in the real life. Others are convinced that, due to the characteristics of the. al. n. iv n C Internet, activism online is effective awareness among users and in turn h einnraising gchi U. stimulating their efficacy (Ma, 2009). This eventually initiates participation in conventional activism. The direction of this correlation can be the other way around, too. In other words, participation in conventional activism may in turn lead to a greater likelihood of action online. It is the purpose of this study to find out more about these correlations. To do that, this research returns to the fundamentals. The author believes there is more than a simple correlation between activism online and conventional activism. It is not merely a yes or no, i.e. enhance or subtract, question. It is believed that there must be some intervening factors that will provide some insights. Therefore, a 1.

(10) political platform in a social networking framework, namely the application of Causes on Facebook, is chosen for analysis. It is believed that the probability of political action either in the real life or online rises with one’s level political efficacy and political knowledge. In other words, the more confident a person feels about his own political action, the more likely he or she will be engaged in political action. Likewise, the more knowledge a person has about a specific issue, the more likely he or she will be engaged in political action targeted at the issue. Now the question comes to what in the political network of Causes promotes the users’ political efficacy and level of political knowledge and in turn increases their probability of political action in the real life.. 立. 政 治 大. The social networking feature of Causes is believed to be the essential factor.. ‧ 國. 學. When using Causes, users have a chance to be linked to other users, some of whom. ‧. may be relatively more active and more knowledgeable in the issue. The social. sit. y. Nat. networking feature of Causes makes connections among users possible. Because of. io. er. Causes, it is a lot easier for people with the same political interests to come together and form associations that will eventually promote political efficacy. Users may. al. n. iv n C connect through their use of the discussion On the other hand, there is also a h e n gboard. chi U. large amount of information such as news posts and video clips on the topics related to the issue. Through these pieces of information, users have a chance to grow in political knowledge regarding the issue, and this will also lead to a higher level of political efficacy. The first objective of this study is to find out whether activities on Causes are correlated with activities in conventional activism. Secondly, it will find out whether reinforced political efficacy and improved political knowledge play an important role in the aforementioned connection. It should be noted here though that this direction from action online to political efficacy and knowledge to conventional activism can 2.

(11) go the other way around as well. However, this study is mainly interested in the direction from action online to conventional activism.. 1.2. What motivates this study? Diani (2000) pointed out that computer mediated communication (CMC) has. been frequently believed to dramatically affect a whole range of fundamental human activities, from work organization (e.g. through telecommuting) to democratic procedures (as reflected in the advent of ‘electronic democracy’) to the multiplication of personal identities and the self. One of the most recent forms of. 治 政 CMC occurs in the space of social media or social-networking 大 websites, and in recent 立 years, they have been under constant discussion especially in terms of how they ‧ 國. 學. contribute to the functioning of society as well as the formation of a whole new. ‧. culture in the cyberspace. Among all the controversies, how social media contributes. sit. y. Nat. to the concept and action of social, civil, political activism has been of particular. io. er. interest to the academics and the activists alike. However, with a more comprehensive overview, it is not difficult to identify a wide range of opinions. al. n. iv n C regarding the role social media plays Such discrepancy in the public h e nin gactivism. chi U opinion regarding social media activism is the basis of motivation for conducting this research, which aims to find out whether social media can effectively network users, whether it provides information that, and whether it can eventually initiate participation in conventional activism. Through answering these questions, this study hopes to solve the fundamental question as regards the true extent to which social media are able to contribute to the social, civil and political activism. To illustrate the aforementioned discrepancy, this chapter begins with a brief overview of some opinions in response to the effectiveness and the effects of social media on conventional activism. 3.

(12) 1.2.1. Positive opinions regarding social media activism. Some express optimism as to the almighty power social media is able to inject into the work of activists’. A social media strategist named Jye Smith from Switched On Media 1 expressed such optimism. According to Smith (Ma, 2009), online campaigning is increasingly useful in raising awareness of issues and influencing change. In addition, he also believes that social media presents a new set of opportunities because now it only takes a click of a button to activate the action of the majority. Awareness is extremely important in this case, as people will not care. 治 政 unless they know. This is why some people believe that 大 social media is essential in 立 successful activism because it is effective in drawing people’s attention to a certain ‧ 國. 學. issue. Ma (2009) gave another example where social media such as Facebook and. ‧. Twitter had been successfully applied in raising the awareness of a cause dedicated. sit. y. Nat. to helping child soldiers in northern Uganda. The example illustrates an effective. io. er. utilization of social media to provide a channel for thousands of people who care to make a difference and to tap into the organization in charge of the issue or cause.. n. al. 1.2.2. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Negative opinions regarding social media activism. On the other hand, people like Morozov, the writer of the passage quoted in the beginning of this chapter, seem skeptical about the true extent to which social media can bring about social change. Morozov apparently is not alone in holding and conveying such thoughts. Marc Lynch is a political scientist at George Washington University. He believes that being part of a Facebook group is perhaps a political activity that doesn’t cost much in terms of various efforts (Morozov, 2009). It doesn’t 1. Switched On Media is a digital marketing agency which focuses on search engine optimization and social media. 4.

(13) involve any commitment and dedication such as protesting and other real political work necessary to conventional activism. Holding similar views are also Nathan Bush, a social media expert at DP Dialogue2, and Omar Samad, a social media marketer. According to Bush, digital activism falls short in changing bigger issues such as political situations, especially in countries such as China or North Korea (Ma, 2009). He added that people consider it trendy to be seen as a good person among their network of friends online, and that’s what matters. Samad shares the same view. He doesn’t consider social media to be an ideal tool for causing social change, and even though it is a good medium for generating awareness and organizing people, it does. 治 政 not cause people in power to take notice. 大 立 People who are skeptical about the effectiveness of social media activism refer ‧ 國. 學. to it as “slacktivism”3, a term coined for people who join a cause group on Facebook. ‧. just to gain social currency. Evgeny Morozov (2009) provided a definition of. sit. y. Nat. slacktivism: “slacktivism is an apt term to describe feel-good online activism that has. io. er. zero political or social impact. It gives those who participate in ‘slacktivist’ campaigns an illusion of having a meaningful impact on the world without demanding anything. n. al. ni Ch more than joining a Facebook group.” U engchi 1. 3. v. Conceptual organization As illustrated in the previous section, the disparity in people’s attitudes towards. social media activism intrigues the author of this study and provides the motivation to ask several questions regarding what exactly determines the effectiveness of social media activism in enhancing conventional activism. Morozov (2009) expressed his concern about the influence of social media activism on conventional forms of 2. DP Dialogue is an Australian social media marketing company. Slacktivism (sometimes slactivism) is a portmanteau word formed with the combination of slacker and activism. 3. 5.

(14) activism. He proposed an intriguing question: “Is it possible that now with availability of slacktivist forms of activism, people will gradually turn away from conventional forms of activism such as demonstrations, sit-ins, confrontation with the police, strategic litigation, etc?” This is worrying, according to him, because conventional forms of activism have been proven to be effective, while the effectiveness of social media activism is still unclear. Diani (2000) proposed a similar question: "Should we expect the emergence of new types of ‘virtual’ social movements, disconnected from a specific location in space and without reference to any specific ‘real’ community?” Both of them seem to express a concern for the disconnection between activism. of activism and social movements.. 學. ‧ 國. 治 政 online and activism in real life. As a result, it is the purpose 大 of this study to find out 立 whether the answer to these questions can provide an insight to the understanding ‧. The analysis of this study starts with the concept of networking. Several. sit. y. Nat. concepts in the network theory will first be reviewed and then applied to see how. io. er. they contribute to the linkage between social media activism and conventional activism. Specifically, several networking activities on Causes will be examined to. al. n. iv n C learn about the role they play in the Networking is the dominant feature of h elinkage. ngchi U. social media. Diani (2006) pointed out that social networks influence participation in collective action. Networking may increase individual chances to become involved and strengthen activists’ attempts to further the appeal of their causes. This statement illustrates the fact that the networking feature that comes with social media may occupy an extremely important position in the discussion of activism. This study presupposes that while taking part in social media activism, i.e. taking part in specific Facebook cause groups, an individual, through several networking activities, establishes new connections and reinforces existed connections, which in turn may enhance their political efficacy and facilitate the development of new forms of 6.

(15) collective action at later stages (Diani, 2006). As a result, a question regarding the networking feature of activism is asked: Does being linked to people who already participate may enhance individuals’ political efficacy and facilitate their decisions to devote time and energy to conventional collective action? In other words, when individuals use Facebook’s application of Causes and through it meet people who are involved in conventional activism, these individuals will feel politically more efficacious and have a better chance to joining real-life activism events. Then, the study moves on to discuss how the various types of information on Causes, such as news posts, links to relevant materials online, video clips and so on,. 治 政 can help users develop their political knowledge. 大 An increased level of political 立 knowledge will also allow the users to feel politically more efficacious and boost the ‧ 國. 學. possibility for them to participate in conventional political actions.. ‧. So what role does political efficacy play in this discussion? Hollander (1997), in. sit. y. Nat. one of his articles, discussed the implication of Gamson Hypothesis on social activism.. io. er. According to him, Gamson proposed that “a combination of high political efficacy and low political trust is the optimum combination for mobilization” (quoted from. al. n. iv n C Hollander, 1997). In the same article, also discussed Bandura’s theory of h eHollander ngchi U. efficacy. According to Bandura’s theory of human coping behavior, “when self-efficacy feelings are high but response outcome expectations are low, the result is social activism, protest, and milieu change.” The two theories proposed above demonstrate the significance of political efficacy in bringing about social change. As a result, this study will try to find out whether and how the networking feature of Facebook’s Causes as well as the political knowledge of issue information will increase users’ political efficacy, and in turn causes activism in real life.. 7.

(16) 1.4. Problem statement As proposed above, several questions need to be answered in order to address. the problem in question: “What determines the effectiveness of social media activism in initiating conventional activism?” Based on those questions, the problem statement is proposed as follows:. Causes, an application on Facebook, seeks to achieve equal opportunity activism by providing a platform for not only political elites and established organizations but also individuals who wish to make their voice heard. Despite such grand objective,. 治 政 there is currently an ongoing debate about the effectiveness 大 of such form of activism 立 that takes place on social media. A problem lies in the fact that there has been no ‧ 國. 學. systematic analysis regarding the effectiveness of social media activism.. ‧. sit. y. Nat. The overall objective of this study is to learn more about the uses of Causes and. io. n. al. er. to find out about users’ attitudes towards the effectiveness of social media activism.. 1.5. Background. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. This section first provides a simple introduction about the growing concern over social networking sites both in the daily life and in the academia before introducing Facebook and Causes.. 1.5.1 Social networking sites It is not difficult to see the value of studying social media activism when a growing trend of social media usage is being witnessed. Aaron Uhrmacher is a social. 8.

(17) media consultant. In a blog entry he wrote for Mashable.com4, he cited some research results from a report published by The Society for New Communications Research titled, “New Media, New Influencers & Implications for Public Relations”. One of the findings from the report is “Social media is rapidly becoming a core channel for disseminating information. 57% of this group of early social adopters reported that social media tools are becoming more valuable to their activities, while 27% reported that social media is a core element of their communications strategy.” (Uhrmacher, 2008). 政 治 大. TABLE 1-1: Growth of Social Media Use. 立. Unique Visitors (000). North America. y. 464,437 580,510. al. n. Europe. Percent Change. 162,738 200,555. 25%. er. io. Asia Pacific. Jun-08. sit. Jun-07. Nat. Worldwide. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Social Networking Growth by Worldwide Region June 2008 vs. June 2007 Total Worldwide Audience, Age 15+ - Home and Work Locations Source: comScore World Metrix. n C122,527 U h e n g165,256 i h c 120,848 131,255. iv. 23% 35% 9%. Latin America. 40,098. 53,248. 33%. Middle East – Africa. 18,226. 30,197. 66%. Source: comScore. Also found in the same blog entry is some statistics about social media usage released by comScore 5 in 2008. As can be seen from the table taken from Comscore.com, the worldwide usage of social networking websites grew by 25% 4. Mashable is a blog focused exclusively on Web 2.0 and social media news. comScore is a marketing research company that provides marketing data and services to many Internet businesses. 5. 9.

(18) within a year. The growth was especially notable in Europe at 35% and the Middle East at 66%. In another blog entry on Mediapost.com6, the growing use of Facebook, where the subject of this current study is located, further illustrates the point. According to the entry written by Mark Walsh who cited the statistics inside Facebook, Facebook had reached 200 million active users only seven months after the social network reached 100 million users and 90 days after reaching 150 million. On average, Facebook has 500,000 new members added every day since late August 2008. Mark Walsh also quoted Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook co-founder and CEO, who wrote:. 治 政 “Both U.S. President Barack Obama and French President 大 Nicholas Sarkozy have used 立 Facebook as a way to organize their supporters. From the protests against Colombian ‧ 國. 學. FARC7, a 40-year-old terrorist organization, to fighting oppressive, fringe groups in. ‧. India, people use Facebook as a platform to build connections and organize action.”. sit. y. Nat. From the aforementioned figures and statements, it is not difficult to see the. io. er. growing significance of social media not only in connecting people but, more importantly, in delivering information and helping organizing social, civil and political. n. al. action.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 1.5.2 An introduction of Causes and Facebook This study looks into the use of the Causes application on Facebook, a tool for social media activism. Before moving forward, it is appropriate to have an idea about some key terms. In addition, this study has selected causes of various scopes for analysis. These causes will also be introduced in this section.. 6 7. MediaPost is an online resource for all advertising media professions. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia 10.

(19) Facebook Facebook Press Room provides a straightforward yet detailed introduction of the company as well as the popular online social networking website it created. This section, however, due to its scope and emphasis, will only focus on certain aspects of the site which are relevant to this study. According to the introduction, Facebook is a social utility website established in February 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg along with some other co-founders. This was when Mark Zuckerberg was attending Harvard University as a Computer Science major. This social networking utility was developed with the aim of helping people. 治 政 communicate more efficiently with their friends, family 大and coworkers. To reach that 立 aim, several technologies have been renovated to facilitate the sharing of ‧ 國. 學. information of the social graph, the digital mapping of people’s real-world social. ‧. connections. Membership to this website was originally restricted to students of. sit. y. Nat. Harvard University but then was expanded to students of other Ivy League Schools. io. er. and then eventually to anyone aged 13 or over. Now the site has more than 250 million active users. The site is also growing internationally. For instance, more than. al. n. iv n C 50 translations are available, with h more than 40 in development. In addition, about engchi U 70% of Facebook users are outside the United States. These international characteristics make Facebook an interesting research subject. Facebook has a Platform feature, which allows companies and engineers to integrate with the Facebook website and gain access to millions of users through the networking function. In other words, developers can create so-call applications using this Platform feature. According to the statistics published on the site, currently there are more than 350,000 active applications on Facebook Platform, and more than 200 of them have more than one million monthly active users. In addition, more than 70% of Facebook users engage with these applications every month. This present 11.

(20) study is concerned with one of these applications called Causes.. Causes The organization Causes was co-founded by Sean Parker and Joe Green and was launched on May 25, 2007. In this section, the introduction of this organization and the Facebook application it designs is adapted from the organization’s website at www.causes.com First of all, about the founders, Parker comes from a background of consumer internet products such as Napster, Plaxo, and Facebook, while Green has a background in grassroots organizing and has worked in political campaigns on. 治 政 different levels, including the city, the state and the大 presidential. The organization, 立 Causes, therefore, is a result of the combination of their knowledge in offline ‧ 國. 學. organization and online social networking. Aside from these two founders, a group of. ‧. devoted engineers, graphic designers, administrators, and managers also contribute. sit. y. Nat. to the success of Causes. Currently based in downtown Berkeley, California, Causes. io. er. operates on a fundamental principal, and that is equal opportunity activism. As stated in the website, ‘Causes was founded on the belief that in a healthy. al. n. iv n C society, anyone can participate inhchange by informing e n g c h i U and inspiring others.’ It is based on this belief that Causes was created to provide people with tools to mobilize their friends for collective action. When set in the social networking context of Facebook, the potential of Causes to extend impacts is fully maximized. With this application on Facebook, everyone can create an advocacy group. This group is referred to a cause group. What sets Causes on Facebook different from other models of activism is that on Causes, individuals and organizations share the same level-playing field, whereas other models of activism usually favor organizations with large budgets. The success of a cause vitally depends on how well the leader or the creator organizes and keeps their community engaged and mobilized. 12.

(21) A few routine functions in a cause include administrators posting announcements and communicating with members either through email or Facebook; members discussing the issues, sharing their experiences, posting media and singing petitions. A cause group can also choose whether to do fundraising by selecting an organization to benefit from the donations. According to some statistics on the website, since the day of its launch, over 50 million people have joined the different causes; over $8 million has been donated through the application; over 240,000 causes have been created by users on various topics.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 13.

(22) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. As carefully introduced in the previous chapter, the purpose of this study is to learn more about the relationship between social media activism and conventional activism through examining various concepts such as network theory, political knowledge of issue information and political efficacy. Before reviewing past studies and theorization of the concepts in this study, the author first provides a general overview of previous studies on the subject of social. 治 政 networking sites (SNSs) by referring to a meta-analysis 大by boyd and Ellison (2008). 立 Following that, the author continues to review literature regarding the ‧ 國. 學. aforementioned fundamental concepts before moving on to discussing their role in. ‧. how social media activism influences conventional activism. In addition, this section. sit. y. Nat. also sees the proposal of several research questions which serves as the basis for the. io. n. al. er. investigation in the later stage.. 2.1. Social networking sites. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. This current study is significant for the very limited amount of research being devoted to the study of social media activism, especially when the discussion is focused on the relationship between social media activism and conventional activism. The majority of the research in the area of social networking sites (SNSs) or computer mediated communication (CMC) has mainly dealt with subjects other than activism online. boyd and Ellison (2008) presented a comprehensive overview of previous scholarship regarding SNSs. They categorized the research into five separate themes, including impression management and friendship performance, networks and network structure, bridging online and offline social networks, privacy, and other 14.

(23) research (boyd & Ellison, 2008). In the category of impression management and friendship performance, researchers have looked into the construction of users’ online representation of self, and SNSs also provide scholars with a context where impression management as well as friendship performance can be investigated. In the category of networks and network structure, scholars have examined profiles and linkage data to study the action of friending. Some of them have also studied the role users play in the growth of SNSs by classifying users into passive members, inviters, and linkers. In addition, there has also been research done about the motivations for people to join a particular network. In terms of bridging online and offline social. 治 政 networks, the investigation has been mainly focused大 on the relationships between 立 these two types of networks. Most SNSs have been proved to primarily support ‧ 國. 學. pre-existing social relations. Also studied is the concept of privacy. Researchers have. ‧. investigated the potential threats to privacy associated with the use of SNSs. Finally,. sit. y. Nat. other research has also been done in the areas of race and ethnicity, religion, gender,. io. er. sexuality as well as how a variety of identities are shaped within the domain of SNSs. Besides the aforementioned research areas, the application of CMC in political. al. n. iv n C movements has extremely important h ealson gbeen chi U. activism or social. and is worth. further in-depth scholarship. This scholarship should deal with not only the application of CMC in activism but also the fundamental question of the influence on activism through/on CMC on conventional activism, which is the purpose of this current study. Various scholars (Castells 1996; Wellman et al. 1996; Cerulo 1997) believe that the rapidly growing role of ‘computer mediated communication’ (CMC) has attracted considerable attention from social scientists and generated extensive discussions of its possible impact on social organization (Diani, 2000). This is especially true when the discussion further extends into activism. Diani expressed his thoughts on the merits of CMC on activism. CMC may be expected to influence how 15.

(24) collective action evolves by improving the effectiveness of communication and facilitating collective identity and solidarity (Diani, 2000). Many believe that the reason why the Internet or CMC plays such an important role in the work of activists is because it connects all sorts of communities that are either geographically dispersed (Rheingold, 1993; Pini, Brown, and Previte, 2004) or forced to operate underground by the very nature of their activities. All these opinions reveal the significance of CMC or SNSs in the discussion of activism and social movements. However, at this time when the discussion mainly focuses on the application, it is even more critical to return to the basis and to study the fundamental relationships. 治 政 between social media activism and conventional activism, 大 which is the significance of 立 this research. Social network analysis. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2. sit. y. Nat. A search on Wikipedia 8 provides a simple yet comprehensive introduction. io. er. about social network analysis. First of all, a social network is a structure composed of individuals or organizations. These components of a social network are referred to as. al. n. iv n C nodes in the network theory. These are then connected by various types of h enodes ngchi U. interdependency, such as friendship, kinship, sexual relationship, relationships of belief, knowledge, prestige, etc. These different forms of relationship are referred to as ties in the network theory. Social network analysis has been applied in several social scientific fields and has become a popular topic of speculation and study. This study will further the research agenda by extending the scope to cover online activism. When studying a social network, it is essential to consider the concepts of 8. Wikipedia is a free, open content online encyclopedia created through the effort of a community of users. 16.

(25) bridging and bonding proposed by Putnam (2000). These two terms were coined on the basis of two other concepts, namely the weak ties and the strong lies, which had been developed by Mark Granovetter (1973) when he was studying people looking for employment. Putnam (2000) used the concepts of bridging and bonding to investigate social capital. According to him, bridging social capital is inclusive and mainly takes place when individuals from various backgrounds establish connections between social networks (Williams, 2006). By contrast, bonding can be exclusive. Bonding happens when close friends or family members provide one another with strong emotional or substantive support (Williams, 2006). A further point noted by. 治 政 Williams (2006) in his study is that despite the fact that 大the aforementioned concepts 立 of bridging and bonding play an important role in understanding communities, they ‧ 國. 學. have rarely been applied to successfully study either online or offline communities. In. ‧. other words, these measures need to be further conceptualized and validated.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.2.1 Significance of network analysis. Do networks always matter? This is an important question raised by Diani (2006).. al. n. iv n C Similar to previous research, this study to find out the effects networks have on h e aims ngchi U. mobilization or participation. The author of this study assumes that the network effects derived from being involved in the cause groups on Facebook can either enhance or subtract users’ participation in conventional activism. In other words, the author assumes that there is a correlation between the two forms of activism. This is further illustrated by Diani (2006) in his review where he has identified several studies, in which the results of network effects are mixed. One example is Oliver’s study (1984), which found that people acquainted with their neighbors were more likely to be involved in neighborhood associations, but network effects were mixed in her study. Another example is Nepstad and Smith’s study (1999). They found that ties 17.

(26) to people directly involved were the most powerful predictor of participation, but ties to other organizations didn’t seem to be as important. However, this relationship became reversed for those people who joined an organization after it has existed for at least 3 years. Since the results of network studies varied under different circumstances, perhaps, it is important for the analysts to qualify their points. Diani (2006) has urged scholars to ask these two crucial questions: “What networks actually explain what?” and “Under what conditions do specific networks become relevant?” In addition, the context or local condition is also very important. In areas where. 治 政 countercultural milieus are strong, and the overall attitudes 大 toward collective action 立 is generally more favorable, there is less need to be linked to members of specific ‧ 國. 學. political organizations to encourage adhesion. From the discussion above, it is not. Networks & ties. io. er. sit. y. Nat. 2.2.2. ‧. difficult to see the importance of incorporating network analysis in the current study.. In the previous chapter, an introduction of the Facebook application of Causes. n. al. was provided. This section. iv n C of literature then turns to h e n greview chi U. examine how the. network theory can be applied in the study of Causes. The concepts of bridging and bonding are helpful in understanding the nature as well as the functions of the Causes application on Facebook. Therefore, in this section, the author first presents some arguments from the existed literature and then discusses the application of these arguments on the study of Causes.. Weak ties of bridging networks and informational input Williams (2006) pointed out that bridging has the potential of broadening social horizons or world views and thus opening up opportunities for information or new 18.

(27) resources. This kind of networks involves participants from different backgrounds. These participants usually share tentative relationships that lack depth (Williams, 2006). In addition, the same article on social networks from Wikipedia states that “more open networks, with many weak ties and social connections, are more likely to introduce new ideas and opportunities to their members than closed networks with many redundant ties.” According to Putnam (2000, p.22), networks with bridging or weak ties are “better for linkage to external assets and for information diffusion”. External assets and information diffusion are the staple concepts. Based on these two concepts, Putnam implied some criteria that are good starting points for. 治 政 theorizing about bridging networks (Williams, 2006).大 These criteria are: 1) outward 立 looking, 2) contact with a broader range of people, 3) a view of oneself as part of a ‧ 國. 學. broader group, and 4) diffuse reciprocity with a broader community. Williams (2006). ‧. then went on to use these criteria to develop questions for research.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Strong ties of bonding networks and emotional support. Bonding networks, on the other hand, provides stronger emotional support,. al. n. iv n C which leads to mobilization of people in various events and activities. h etonparticipate gchi U The participants in these networks with strong ties tend to lack diversity in their backgrounds despite the tighter relationships among them. Oftentimes, the enhanced in-group emotional support may help develop antagonism against the out-group world. As illustrated in Sherif’s study (1988), the formation of a group can lead to feelings of mistrust and dislike for those outside of the group. This is why Putnam (2000) conceptualized bonding networks to be exclusive. Similarly, some criteria are proposed to theorize bonding networks (Williams, 2006). These include: 1) emotional support, 2) access to scarce or limited resources, 3) ability to mobilize solidarity, and 4) out-group antagonism. Based on these criteria, Williams (2006) also 19.

(28) developed some research questions. In the case of Causes, participants in a cause group are recruited through different relationships, usually by friends or family. Facebook is an online platform where people have to be added to a user’s friendlist through his or her own decision. As a result, these people added to the friendlist are usually close friends, family or at least acquaintances. However, once these users have joined a cause group, the ties they establish are usually bridging weak ties.. 2.2.3. Strength of ties and mobilization. 治 政 The previous sections introduce the concepts of大 strong ties and weak ties. But 立 how is the strength of a tie measured? Haythornthwaite (2002) mentioned that it is ‧ 國. 學. by taking into account several factors, such as frequency of contact, duration of the. ‧. association, intimacy of the tie, provision of reciprocal services, and kinship. Previous. sit. y. Nat. studies have concluded that more strongly tied individuals share a higher level of. io. er. intimacy, more self-disclosure, emotional as well as instrumental exchanges, reciprocity in exchanges, and more frequent interactions (Haythornthwaite, 2002).. al. n. iv n C Different levels of strength of h ties may bring about e n g c h i U different mobilization effects.. Therefore, in order to understand whether activism on Causes can be transformed to conventional activism, it is essential to first understand what kind of ties are maintained on Causes. According to Haythornthwaite (2002), “earlier theories and approaches to computer-mediated communication (CMC) have been tacitly concerned with the types of social network relations communicators can maintain via CMC.” It is argued that because of a lack of social presence, online communication exchanges seem to be characterized as instrumental rather than emotional, simple rather than complex, and nonverbal rather than verbal (Haythornthwaite, 2002). Because of these characteristics, online networks seem to be able to maintain weak 20.

(29) ties more efficiently. CMC has been accredited for its ability to provide users with an access to those who are weakly tied, to extend communication potential to overcome temporal and spatial barriers, to inform local and remote operations simultaneously, to draw in more peripheral participants, and to give users an access to a wider set of contacts (Haythornthwaite, 2002). Even though Causes is placed within the framework of Facebook, a social networking website and is thus considered a form of CMC, it would be reckless to assume that ties maintained on Causes are exactly the same as those on other CMC contexts. Next, it is imperative to learn more about the connection between the strength. 治 政 of a tie and the mobilization of collective action. Some 大 scholars such as McAdam 立 (1986) believe that “it is the broad support, emotional aid, and companionship of ‧ 國. 學. strong ties that provides the encouragement and solidarity necessary for collective. ‧. action” (cited from Hampton, 2003). However, scholars such as Granovetter (1973). sit. y. Nat. disagree. He argued that weak ties provide the connectivity indispensable for. io. er. collective action. This viewpoint is thoroughly illustrated in his pioneering work “The Strength of Weak Ties”, in which he argued that although weak ties represent social. al. n. iv n C relations of less intimacy, they are able to bridge U clusters of stronger ties and to he ngchi provide access to a wider range of information and resources (Granovetter, 1973).. 2.3. Issue information and political knowledge According to delli Carpini and Keeter (1996), political knowledge is defined as. “the range of factual information about politics that is stored in long-term memory” (p.10). Political knowledge can be obtained from several sources, such as formal education, interpersonal discussion about politics, and traditional news media consumption, such as newspaper reading (Kenski and Stroud, 2006). In addition, according to delli Carpini and Keeter (1993), a common conclusion in an increasing 21.

(30) number of studies is that political factual knowledge works well in predicting political sophistication and some related concepts, such as expertise, awareness, political engagement, and even media exposure. The significance of political factual knowledge is also illustrated in McAllister’s (2001) study about civic education and political knowledge in Australia. McAllister (2001) pointed out that one of the most important requirements for the functioning of representative democracy is the existence of knowledgeable citizens. Political knowledge may affect citizen’s political sophistication as well as political competence. This is one of the assumptions of the current study. Information regarding an issue on Causes can help promote users’. 治 政 factual knowledge about the issue and in turn increase 大their efficacy and chance of 立 participation. In other words, political knowledge makes users more politically ‧ 國. 學. competent. Political competence refers to the extent to which a citizen can make use. ‧. of abstract political concepts to interpret the political world, to evaluate arguments. sit. y. Nat. and debates, and to make informed political decisions (McAllister, 2001). Although in. io. er. McAllister’s study, political knowledge belongs to the area of electoral politics, the same concept can be applied in this study as well which focuses on civil politics.. al. n. iv n C What is even more relevant to is the fact that political participation h ethisnstudy gchi U. also increases with political knowledge. According to McAllister (2001), political participation involves a wide range of activities, starting from activities such as discussing politics with others, which requires little skill or initiate, to more demanding activities, such as joining a political party. This study assumes that with the information users obtain from Causes, be it factual information from news posts or imagery information from video clips, users’ knowledge about the issue can be enhanced. And this enhanced knowledge will lead to a higher level of efficacy and a higher chance of political action in the real life activism. 22.

(31) 2.4. Issue related political efficacy Based on Abramson and Aldrich’s definition, political efficacy determines the. enactment of political behavior, which means that without feelings of competence and beliefs that one’s actions are consequential, one has little incentive to act politically (Kenski & Stroud, 2006). Campbell, Gurin, and Miller (1954), in The Voter Decides, defined the concept of political efficacy as “the feeling that political and social change is possible, and that the individual citizen can play a part in bringing about this change” (p.187). In the later stage of theoretical development, efficacy was further developed and identified to be made of two different constructs, namely. 治 政 a personal sense of efficacy, commonly known as 大 internal efficacy, and a more 立 system-oriented sense of efficacy, known as external efficacy (Kenski & Stroud, 2006). ‧ 國. 學. A more detailed description of these two constructs can be found in Hollander’s. ‧. study. Self-efficacy (or internal efficacy) has to do with perceptions of one’s ability to. sit. y. Nat. deal with and influence public affairs, and the system (or external efficacy) concept. io. n. al. 2.5. er. has to do with perceptions of the system’s responsiveness to citizen needs.. ni C h and participation Networking, knowledge, efficacy U engchi. v. This section moves on to investigate the connections among all the aforementioned essential factors contributing to political participation within conventional activism. The level of knowledge and efficacy regarding an issue within civil-political activism depends largely on the amount of information retrieved from as well as the frequency of communication or discussion initiated and encountered in a political social network. In the case of this current study, this social network of political communication and exchanges is any cause group. In order to find out whether social networking in a cause group will lead to increased information input and enhanced political efficacy, it is critical to first find out what goes on in a cause 23.

(32) group in terms of information retrieval and political communication and discussion. Discussion of social networks is often closely associated with that of social capital, which is often defined as trust in social relations. In a study about social capital, social networks, and political participation, La Due Lake and Huckfeldt (1998), argued that politically relevant social capital is realized through networks of political communication and thus enhances the likelihood that individuals will become politically engaged. But how is this correlation established? La Due Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) believed it is through obtaining relevant political information. Political activity cannot be meaningful unless it is informed, and the cost of. 治 政 information is a primary cost of political participation 大 (Fiorina, 1990). However, 立 sometimes, the costs of information may discourage expectation of any significant ‧ 國. 學. benefit arising from participation (La Due Lake & Huckfeldt, 1998). In this case,. ‧. economizing this information retrieval process may be the most efficient though a. sit. y. Nat. social network. On the basis of this argument, this study argues that Causes provides. io. al. iv n C Lake and (1998), social h eHuckfeldt ngchi U. n. economical manner.. According to La Due. er. its users a social network, in which they are able to acquire information in an. capital is produced. through networks of relationships, which means that politically relevant social capital is created as the result of political interaction within these networks. Furthermore, some specific dimensions proposed by them can be helpful in understanding politically relevant social capital. These dimensions include the number of individuals in one’s network, the level of political knowledge and expertise among the people in an individual’s network, the frequency of political interaction with others in the network (La Due Lake & Huckfeldt, 1998). These dimensions are believed, in this study, to stimulate users’ political knowledge and efficacy, which, in turn, enable the users to become more fully engaged in a wider range of political activities, namely 24.

(33) those in the area of conventional activism. In other words, Causes on Facebook, with its networking characteristics, empowers its users to participate in civil politics. This is attested in a study by Zhang and Chia (2006). Their survey showed that social connectedness enhances both civic and political participation.. 2.6. Theoretical structure The following theoretical structure provides an overview of the first part of this. study which examines the correlations among all the major concepts through a survey. As mentioned above, the correlations among the variables can be examined. 治 政 both ways. In other words, activities on Causes can facilitate 大 conventional activism; 立 on the other hand, experiences with conventional activism can also facilitate political ‧ 國. 學. action online. However, the analysis in this study focuses on whether the variables. ‧. are correlated or not rather than whether there is a causal relationship among them.. n Independent Variable A. er. io. al. sit. y. Nat. FIGURE 2-1: Theoretical Structure. i n C U h e n Variable Independent g c hBi. v. Political Efficacy. Activities on Causes A1. General uses A2. Informational retrieval activities A3. Social networking activities. Dependent Variable D. Conventional Activism. Independent Variable C. Political Knowledge. 25.

(34) 2. 7. Research questions Based on the structure proposed above, the author raises the following research. questions.. RQ1: What is the connection between the activities on Causes and participation in conventional activism?. RQ2: What is the connection between political efficacy and participation in conventional activism?. 立. 政 治 大. RQ3: What is the connection between political knowledge and participation in. ‧ 國. 學. conventional activism?. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 26.

(35) CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY & RESULTS (SURVEY). This study begins with a survey in order to investigate some overriding correlations among the concepts. In addition, as explained later in this chapter, to complement the responses to the survey, this survey is treated as a pre-test, whose results will be used for the author to continue to carry out interviews with some of the survey respondents in order to uncover some truths and findings that add weight to the significance of the results gathered through the survey. As a result, this. 治 政 chapter will focus on the survey as a pre-test and will大 discuss some simple findings. 立 In the next chapter, the questions to the intensive interviews will be partly based on ‧ 國. 學. the results of the pre-test.. ‧. Research subjects. sit. y. Nat. 3.1. io. er. The aim of this study is to find out whether users of Causes will continue to participate in real life political activism concerning Proposition 8 and same-sex. al. n. iv n C marriage legislation after being involved cause groups and carrying out the h e ningspecific chi U. actions mentioned above which are defined as the uses of Causes. This section will briefly outline some fundamental concepts related to Proposition 8 and then discuss the process of selecting subjects to take part in the survey and the interview.. 3.1.1 Proposition 8, its proponents and opponents Wikipedia.com provides a detailed account of the California Proposition 8. According to the article on Wikipedia.com, Proposition 8, also known as the California Marriage Protection Act, was a ballot proposition and constitutional amendment passed in the November 2008 state elections. The measure added a new 27.

(36) provision, Section 7.5 of the Declaration of Rights, to the California Constitution. The new section reads: “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” By restricting the definition of marriage to opposite-sex couples, the proposition overturned the California Supreme Court’s ruling of In re Marriage Cases that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry. The campaigns for Proposition 8 were led by the ProtectMarriage.com organization and raised $39.9 million. Some of the ideologies on which their claims were based were that heterosexual marriage was an essential institution of society, that if the constitution was not changed, children would be led on to believe gay. 治 政 marriage was okay, and finally that gays did not have大 the right to redefine marriage 立 for everyone else. ‧ 國. 學. On the other hand, the campaigns against Proposition 8 were led by Equality for. ‧. All, a renowned gay activist group. They raised $43.3 million. The basis of their. sit. y. Nat. argument is that the freedom to marry is essential to the society, that the California. io. er. Constitution should guarantee the same rights and freedom to everyone and that having different sets of rules because of differences in sexual orientation is unfair.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3.1.2 Selection of subjects Even though there are two camps of political campaigns which are dedicated either for or against Proposition 8, this current study will only focus on one of them, namely those against Proposition 8 and for same-sex marriage. There are several reasons for this choice. First of all, the objective of this study is to find out the relationship between online activism and conventional activism. Therefore, even though incorporating the ideologies of marriage from both camps will be valuable, for a study on this scale, such incorporation might complicate the matter to the extent behind the comprehension of this study. The ideologies, however, can be a 28.

(37) valuable variable to take into account for future studies. Secondly, the Internet is especially valuable for those who are socially marginalized to reach their political aims. As a result of that, it is reasonable to select the Cause groups which are dedicated to overturn Proposition 8. The application of Causes on Facebook has a function which allows users to search for cause groups of a subject matter. By typing in some key words of the subject, a list of cause groups related to the subject will appear on the screen. First, the key words, ‘Proposition 8’ were used to do the search. A list of 35 cause groups (as of 2010/3/10) dedicated to Proposition 8, both for and against, appeared on the. 治 政 screen. The author then chose the three cause groups 大on the list with the largest 立 numbers of members. They are respectively DEFEAT Proposition 8 (109,617 members ‧ 國. 學. as of 2010/3/10), REPEAL Prop 8 (43,315 members as of 2010/3/10) and Don’t. ‧. eliminate same-sex marriage in California (3,874 members as of 2010/3/10). The. sit. y. Nat. reason these three groups were selected is because they have the largest numbers of. io. er. members and thus can maximize the number of respondents to the survey. However, due to the lack of survey respondents, the author then chose and input the key. n. al. words, ‘same-sex marriage’. iv n C to do A list of 94 h ethensearch. gchi U. cause groups (as of. 2010/4/10) appeared on the screen. Some of the groups are also on the previous list. Excluding these overlapping groups, another four groups were chosen because of their size. These groups are namely One Million for Same-sex Marriage (444,583 members as of 2010/4/10), Marriage = Person + Person (11,373 members as of 2010/4/10), Legalize Same-sex Marriage (2,108 members as of 2010/4/10), and Support Same Sex Marriage both Gay and Lesbian (2,600 members as of 2010/4/10). Respondents are recruited through a few channels. First, the author sent out emails to the administrators of the groups and asked them to forward the link to an online survey to the users of the groups. The users were invited to fill out the 29.

(38) questionnaire online. In the second stage, due to a lack of response, the author then went on to each group and sent individual emails to some users and asked them to forward the link as well. At the same time, the author also asked some friends who are also members of these groups to fill out the online questionnaire and to forward to their friends the link to the questionnaire.. 3.2. Sampling and questionnaire design The survey of this study, which aims to find out the correlations among variables. such as the uses of Causes, political efficacy, political knowledge and conventional. 治 政 activism, adopts the method of convenience sampling. 大 Based on a search on 立 Wikipedia, convenience sampling is also known as accidental sampling. This type of ‧ 國. 學. sampling usually involves taking a sample from a section of population that is readily. ‧. accessible.. sit. y. Nat. The main reason for such a choice is the difficulty to reach the users of these. io. er. groups and to recruit them to participate in the survey. This observation stems from the fact that while attempting to conduct a pre-test of the questionnaire, the number. al. n. iv n C of responses was very low. Despite it was still decided that the result of the h ethis, ngchi U. survey with a low response number can be useful as a reference for the intensive interviews. In other words, the results of the survey and those of the interviews will work complimentarily to answer the research questions. It should be noted that in spite of the large numbers of members in the selected groups, the number of ‘active’ users is actually considerably smaller in each group. For example, according to the statistics on the Causes page, as of 2010/4/10, DEFEAT Proposition 8 has only 72 active users. REPEAL Prop 8 has only 34 active users. Don’t eliminate same-sex marriage in California has only 20 active users. One Million for Same-sex Marriage has 2,346 active users. Marriage = Person + Person has 44 active 30.

(39) users. Legalize Same-sex Marriage has 16 active users. And Support Same Sex Marriage both Gay and Lesbian has only 8 active users. Even though these numbers fluctuate over time, they remain relatively small compared to the total numbers of registered members. This may justify the fact that survey respondents were difficult to find. More discussion regarding a lack of active users will be found in a later chapter. The questionnaire contains seven parts. The first part asks about demographic information. The second asks about the general uses of Causes. The third asks about the uses of cause groups related to Proposition 8, focusing especially on two types of. 治 政 activities, namely the information retrieval activities 大and the social networking 立 activities. The fourth asks about political knowledge. The fifth asks about political ‧ 國. 學. efficacy. The sixth asks about participation in conventional activism. Finally, the. sit. al. er. Variables. io. iv n C This section introduces the variables in the theoretical structure. At h e n gpresented chi U n. 3.3. y. Nat. questionnaire, please refer to Appendix A.. ‧. questionnaire ends with an invitation to the intensive interview. To see the. the same time, a reliability test among all the items in each part of the questionnaire is also conducted to see if they can be combined to establish indexes for later analysis.. 3.3.1 Independent variables Demographic variables The first set of independent variables in this study are about the demographic information of the users. The study asks about nationality, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, age, level of education, and political stance. 31.

(40) General uses of Causes Another set of independent variables are about the activities performed or enacted on cause groups. However, to begin with, the study asks several questions regarding the general uses of Causes, questions such as how familiar users are with Causes, how often they use Causes, and how often they use the cause groups on Proposition 8. In addition to those, it also asks how long a user has used Causes and how many cause groups he is a member of. There are, in total, five questions. However, a reliability analysis found that when deleting question 4, the reliability. 治 政 rises from Cronbach’s alpha = .515 to Cronbach’s alpha= 大 .888. Therefore, question 4 立 of this part is deleted. The other four questions are together treated as the “general. sit. y. Nat. Uses of Proposition 8 cause groups. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. uses of Causes index”.. io. er. Then, moving on to the uses of cause groups dedicated to Proposition 8, the study asks questions about the activities, such as fundraising, recruiting, awareness,. al. n. iv n C advocacy, and karma, which are available all cause groups. First of all, certain but h e n on gchi U. not all cause groups are geared toward not only awareness but also donation. For these groups, the function of fundraising allows the users to either donate money or raise funds. The unit of donation and fundraising is US dollars. These two sub concepts are operationalized to be the amount of money donated or raised by a user. On the users’ main cause page, they not only can see a record of donation made by themselves, but they also know how much their friends have donated, which is known as fundraising. Next, recruiting is an activity on Causes where users can invite their friends to be part of a cause group. Once a person joins a cause group, either through invitation 32.

(41) or self-discovery, they will have a choice to post this information on the main personal Facebook page. It is through this information on their personal page that their friends can be exposed to the same cause group. This is a special function on Facebook called News Feed9, where friends of a user are kept updated with the activities a user is involved in. Also, after a person joins a group, he will be given an option to send invitation to his friends on Facebook to join in this group. Through either way, if any of his friends joins the group, he is said to be a recruiter. The unit of recruiting is the number of members. The third activity available on Causes has to do with awareness. On a cause. 治 政 group page, users may often post links to articles, 大 video clips of relevant subject 立 matters or simply their own stories or experiences. If a user clicks on one of these ‧ 國. 學. links and read or watch the material, he is said to perform this action of awareness.. ‧. Causes keeps a record of the number of links viewed by a user as well as the number. sit. y. Nat. of links viewed by his friends. The unit of awareness in this study is the frequency of. io. er. links viewed and posted. Besides viewing, this study will also look at the number links posted by a user as their effort to raise awareness. Therefore, this concept is divided. n. al. C h receiving. U n i into awareness giving and awareness engchi. v. The next activity on Causes is advocacy. It’s an activity through which a user can sign a petition and help gather signatures for the petition in order to appeal to a certain target audience. The units of advocacy are the number of petitions signed by a user and the number of signatures gathered by a user. For the purpose of this study, a new concept is named signature gathering. The last function of Causes is karma. On Causes, a user can send thanks to another user for joining the group or for recruiting someone to be part of the group 9. A News Feed is a list of updates on a user’s own Facebook home page, which will show updates about those people who are on his or her friend’s list, as well as odd advertisements. 33.

(42) through the use of karma. The unit of karma is the number of thanks sent and received. As a result, the concept is divided into karma thanks sent and karma thanks received. Besides these functions and activities listed on Causes’ main page, there is also a discussion board in every cause group, where users can initiate a discussion and/or join in the discussion by posting their views on the issue. For the analysis in this study, the unit of discussion board use is the number of postings as well as the frequency viewing on the discussion board. Therefore, the concept is divided into discussion positing and discussion viewing.. 治 政 For the purpose of this study, the activities大 above are divided into two 立 categories, namely the social networking activities and information retrieval activities. ‧ 國. 學. Activities belonging to the first group have a proactive nature, meaning a user has to. ‧. produce or initiate an action. Examples include fundraising, donation, recruiting,. sit. y. Nat. posting links, clips or stories, signing petitions, gathering signatures, sending thanks. io. er. other users. These are questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17 in Part 3 of the questionnaire. This category has a high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha= .892) and is. n. al. i n Cindex”. treated as the “social networking U hengchi. v. Activities belonging to the second group have a reactive nature, meaning a user has to respond to information on Causes. Examples include reading or watching information in the links, clips, or personal stories as well as viewing the discussion. These are questions 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. This category also has a high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha= .916) and is referred to as the “information retrieval index”.. Political efficacy and political knowledge As shown in the theoretical structure presented in Chapter 2, there are two other independent variables in this study. They are respectively political efficacy and 34.

(43) political knowledge. First of all, issue specific political knowledge is defined as the level of knowledge a user has about the issue and relevant topics. In the case of this current study, the issue is Proposition 8 regarding same-sex marriage in the USA. This study will ask a series of 8 questions regarding Proposition 8 and relevant issue topics to assess the users’ level of knowledge on this issue. The questions, as presented in the fourth part of the questionnaire, are mostly about details regarding dates, people, and statistics about Proposition 8. These questions are devised by the author with the reference to relevant documents and information on the Internet. For every question answered. 治 政 right, one point will be given, so the scores vary from 0大 to 8. The final score represent 立 the subject’s level of political knowledge regarding Proposition 8 and same-sex ‧ 國. 學. marriage legislation. The reliability among all the items in this group is very low. ‧. (Cronbach’s alpha= .144).. sit. y. Nat. Next, political efficacy regarding Proposition 8 and relevant issue topics is. io. er. defined as the level of confidence in one’s effort in making a difference. This study will ask the users to assess their own level of confidence in their ability to change the. al. n. iv n C status quo of Proposition 8 and relevant This study uses a list of statements h e n issues. gchi U. adapted from their original from Campbell et al. (1954). Please see the questionnaire in Appendix A for the statements. These statements are adapted from Campbell et al. (1954). The subjects will be asked to answer either agree or disagree for each of the above statements. If they answer agree to statements 1, 3, 4, and 5 and disagree to statement 2, then they are considered to be politically efficacious. For statements 1, 3, 4 and 5, for each statement agreed, one point will be given, and for each statement disagreed, 0 point will be given. On the other hand, one point will be given if statement 2 is disagreed, and 0 point will be given if it is agreed. In the end, the final score represents the subject’s level of political efficacy. The reliability among the 35.

(44) items in this group is also quite low (Cronbach’s alpha= .375).. 3.3.2 Dependent variable The dependent variable in this study is about the participation in conventional activism related to Proposition 8. This study asks the users about their experiences in which they have involved themselves in the following Proposition 8 or same-sex marriage related activities: protests, parades, rallies, sit-ins, demonstrations, petitions, or discussions. It also asks them about affiliation with organizations, volunteer work, and recruitment. For the first two questions, the answers range from. 治 政 ‘none’ to ‘more than 10’, with ‘none’ scoring 0 and大 ‘more than 10’ scoring 4. For 立 question 3, the answers range from ‘none’ to ‘more than $US 201’, with ‘none’ ‧ 國. 學. scoring 0 and ‘more than $US 201’ scoring 5. For questions 4, 5, and 7, the answers. ‧. range from ‘never’ to ‘everyday’, with ‘never’ scoring 0 and ‘everyday’ scoring 5. For. sit. y. Nat. question 6, the answers range from ‘none’ to ‘more than 4’, with ‘none’ scoring 0 and. io. er. ‘more than 4’ scoring 4. For question 8, the answers range from ‘none’ to ‘more than 16’, with ‘none’ scoring 0 and ‘more than 16 scoring 4’. Please see the questionnaire. al. n. iv n C reliability hof the items in U e n g c h i this group. for the questions. The. is high (Cronbach’s. alpha= .884).. 36.

(45) TABLE 3-1: Correspondence between Variables and Questionnaire Items Independent Variables Variable Name. Questionnaire Section. Numbers of Items. Demographics. Part 1 (Q1-Q7). 7. General uses of Causes. Part 2 (Q1-Q5). 5. Social networking activities. Part 3 (Q1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17). 12. Information retrieval activities. Part 3 (Q7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). 5. Political knowledge. Part 4 (Q1-Q8). 8. Political efficacy. Part 5 (Q1-5). 5. Dependent Variable Variable Name. Questionnaire Section. Conventional activism. 立. Number of Items. 大. 8. 學. Data analysis. ‧ 國. 3.4. 治 政6 (Q1-Q8) Part. This study adopts several levels of data analysis, such as frequency analysis,. ‧. ANOVA, T-test, correlation analysis, and simple linear regression as well as multiple. sit. y. Nat. regression analysis.. n. al. er. io. First of all, a correlation analysis is conducted to find out the connections. i Un. v. between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Then, to learn more. Ch. engchi. about the connections and see if certain independent variables can serve as predictors of the dependent variable, several regression analyses are conducted. Finally, to explore the role demographic variables play in this study, ANOVA and T-test are conducted to see if there are significant differences among the users with different backgrounds.. 3.5. Survey results. 3.5.1. Demographic data. At the end of the survey, 51 responses were collected, but 6 of them were 37.

數據

相關文件

The purpose of this study is to analyze the status of the emerging fraudulent crime and to conduct a survey research through empirical questionnaires, based on

In order to serve the fore-mentioned purpose, this research is based on a related questionnaire that extracts 525 high school students as the object for the study, and carries out

The purpose of this study is to investigate the researcher’s 19 years learning process and understanding of martial arts as a form of Serious Leisure and then to

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of learning organization culture on teachers’ study and teaching potency in Public Elementary Schools.. The research tool of

The purpose of this research is to study the cross-strait visitor’s tourist experience.With the research background and motives stated as above, the objectives of this research

The main purpose of this study is to explore the status quo of the food quality and service quality for the quantity foodservice of the high-tech industry in Taiwan;

The purpose of the study is to explore the relationship among variables of hypermarkets consumers’ flow experience and the trust, the external variables, and the internal variables

The main purpose of this study is to explore the work enthusiasm of the Primary School Teachers, the attitude of the enthusiasm and the effect of the enthusiasm.. In this