期末報告

消費者如何從品牌識別標誌設計中知覺公司的品牌延伸能力

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型計畫 計 畫 編 號 : MOST 104-2410-H-004-128-執 行 期 間 : 104年08月01日至105年10月31日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 別蓮蒂 計畫參與人員: 博士後研究:陳玉珊中 華 民 國 106 年 01 月 26 日

現,當品牌標誌無外框時,消費者能夠聯想到比較多的產品,而且 所聯想產品品項可跨越較多的類別,出現較多高層次的品類概念 ;主要原因是源於消費者在無框情況下,可連結到比較多的高層次 產品屬性,因而可以適用於更多的產品類別。研究三則直接探討當 移除品牌標誌的外框後,消費者是否對品牌延伸的接受度就比較高 ,另外納入消費者的調節焦點做為調節變數,發現移除外框對以加 品牌延伸接受度的效果,對促進焦點的消費者特別有效,對預防焦 點的消費者則無明顯作用。研究結果可提供品牌標誌設計者和品牌 經理參考。 中 文 關 鍵 詞 : 品牌標誌外框,品牌延伸,產品聯想,調節焦點理論

英 文 摘 要 : Three studies show that a logo frame impacts consumers’ product associations as well as their perceived fit for brand extensions. In Study 1 and 2, participants

associated more products with a brand when the logo frame was removed. Participants also associated more diverse products at an abstract product level when the brand had an unframed logo rather than a framed one. Because a brand linked with diverse products under a broad category can carry more attributes shared by the original and extended product, such perceptions of resemblance should be able to enhance the perceived fit of the new extension. Study 3 supported the proposition that freeing the logo from a frame increases its perceived fit with new extensions. In addition, consumer’s regulatory focus moderated the above relationships. The impact of a logo frame on product associations and perceived fit of new extensions was salient among promotion-focused consumers but was limited to prevention-focused people. The results can contribute to logo design and brand management.

英 文 關 鍵 詞 : logo frame, brand extension, product associations, regulatory focus

科技部補助專題研究計畫成果報告

(期末報告)

(計畫名稱)

計畫類別:個別型計畫

計畫編號:MOST 104-2410-H-004-128

執行期間: 104 年 8 月 1 日至 105 年 10 月 31 日

執行機構及系所:國立政治大學企業管理學系

計畫主持人:別蓮蒂

計畫參與人員:陳玉珊博士後研究員

中 華 民 國 105 年 12 月 31 日

Free the Brand: How a Logo Frame Influences the Potentiality of Brand Extensions

Yu-Shan Athena Chen1 and Lien-Ti Bei2

1

Department of Industrial Design in Eindhoven University of Technology

2

Department of Business Administration in National Chengchi University

Author Note

Yu-Shan Athena Chen is an assistant professor at the Department of Industrial Design,

Eindhoven University of Technology (Y.S.Chen@tue.nl), Laplace building, LG 1.46, De Zaale, Eindhoven, Netherlands. Lien-Ti Bei (lienti@nccu.edu.tw) is a distinguished professor at the Department of Business Administration, National Chengchi University, No. 64, Sec. 2, Zhinan Rd., Taipei City 11605, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Abstract

Three studies show that a logo frame impacts consumers’ product associations as well as their perceived fit for brand extensions. In Study 1 and 2, participants associated more products with a brand when the logo frame was removed. Participants also associated more diverse products at an abstract product level when the brand had an unframed logo rather than a framed one. Because a brand linked with diverse products under a broad category can carry more attributes shared by the original and extended product, such perceptions of resemblance should be able to enhance the perceived fit of the new extension. Study 3 supported the proposition that freeing the logo from a frame increases its perceived fit with new extensions. In addition, consumer’s regulatory focus moderated the above relationships. The impact of a logo frame on product associations and perceived fit of new extensions was salient among promotion-focused consumers but was limited to prevention-focused people. The results can contribute to logo design and brand management.

Free the Brand: How a Logo Frame Influences the Potentiality of Brand Extensions

Brand extensions are the cornerstone for firm growth (Loken & John, 1993; Zhang & Sood, 2002). Associating a new product with a parent brand could enhance consumers’ preference for the extension by leveraging positive associations and trust through the parent brand (Erdem, 1998). Consumers’ fit perceptions regarding an original and extended product are the key to a successful determination of a brand extension (Arslan & Altuna, 2012; Dwivedi, Merrilees, & Sweeney, 2010; Nijssen & Agustin, 2005). To break the stereotypical associations of a brand’s image with its current product categories, marketers may modify the original brand identity to demonstrate a new quality, thereby increasing the perceived fit with the coming extensions. Starbucks’ logo redesign is a case in point. In May 2010, Starbucks declared its new logo by erasing its brand category and the frame to create a “liberated” image in the hopes of opening the door for non-coffee products

(Starbucks, 2010). Removing the “coffee” from the logo literally released Starbucks from the specific product category. However, this study intended to explore Starbucks’

proposition that freeing the logo from the visual boundary, i.e., the frame, would encourage consumers to perceive the brand with a wider product scope and thereby enhance the acceptance of the brand’s extension.

Previous studies have suggested that logo features impact consumers’ attitudes toward a brand and its products (Doyle & Bottomley, 2006; Hagtvedt, 2011; Hem & Iversen, 2004; Jiang, Gorn, Galli, & Chattopadhyay, 2015; Rompay, Hekkert, Saakes, & Russo, 2005). These studies demonstrated that the visual features of a logo are perceived not only with regards to the aesthetic properties but also with regards to symbols or connotations. By adopting a cognitive linguistic lens, which addresses figurative associations and the role of

image schemas (Johnson, 2008; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999), this study suggests that the logo frame implies the boundary of a brand.

The perception of a boundary also might be related to individual tendencies. For example, prevention-focused people tend to avoid risks and are less likely to accept new products; they tend to adhere to the implied limitation and act properly within a given boundary (Henderson, Gollwitzer, & Oettingen, 2007; Higgins, 2008; Vaughn, Baumann, & Klemann, 2008). Reciprocally, promotion-focused people are more likely to be adventurous and go beyond a given boundary. Therefore, consumers’ regulatory focus, which is one kind of personality type, was studied for the way in which these types interact with a logo frame and its possible brand extensions.

These propositions were first explored in a qualitative study which illustrated consumers’ product associations with a framed and unframed logo. Based on cognitive linguistics

research, the logo frame should narrow product associations because the visual boundary implied a limit and transmitted a concept of confinement. The regulatory focus was

manipulated by a temporal activation to explore its moderating role in the relationship of the logo frame and consumers’ product associations (Study 1). Study 2 further controlled two critical design features, i.e., shapes and colors, and used a chronic regulatory focus as the predictor to reexamine the impact of the logo frame and regulatory focus on perceived brand scopes. With these two studies, we could initially know how a logo frame influences consumers’ perception and response to a parent brand. Study 3 presented brand extension scenarios to reveal how promotion and prevention-focused people evaluate and accept the brand extension of a framed versus unframed logo. Together, these studies demonstrated how a frame could affect consumers’ reactions to the brand and its product categories. Hopefully, these studies provide a rationale for why removing the frame could support a new extension.

Relationship between the Logo Frame and the Brand Extension

Long-standing findings in design and psychology suggested that visual and verbal brand features such as name, typeface, shape, and color are perceived not only regarding the actual appearance of these design features but also regarding their figurative associations

(Chattopadhyay, Gorn, & Darke, 2010; Cian, Krishna, & Elder, 2014; Gorn, Jiang, & Johar, 2008; Jiang, et al., 2015; Klink, 2003; Patrick & Hagtvedt, 2011). The figurative

associations have been found to influence both specific brand perceptions and product evaluations (Hagtvedt, 2011; Janiszewski, 2001). Hagtvedt (2011) indicated that an incomplete typeface logo had an unfavorable influence on perceived firm trustworthiness. In Jiang et al. (2015), circular versus angular-logo shapes were found to activate softness and hardness associations related to the products, respectively. Klink (2003) further

demonstrated that consumers had a better attitude toward and understanding of a brand when the connotations related to the logo’s features were consistent (e.g., a prestige brand with a gold logo) rather than those that were inconsistent (e.g., a prestige brand with a

black-and-white logo) with the brand. These studies supported the idea that a logo’s features carried with them a particular concept and meaning for the brand and influenced consumers’ perception and attitude of the brand and its products. In the following section, the possible associations activated by a framed logo and its impact on perception was reviewed.

Figurative Associations Activated by Logo Frame

The logo frame is a tangible boundary; and, the scope of product categories under a brand can be considered as an intangible boundary. Both tangible and intangible boundary dictate where items belong and which parts are contained. In this study, we proposed that

the tangible boundary, logo frame, could activate an intangible boundary of a brand as to which product lines belong to it.

Existing research disclosed that various boundaries could imply a psychological restraint and limit people’s behavior. The boundary allows people to focus better on the important elements inside it and provide mental starting and stopping points that ease their ability to process the elements in a given scope (Burris & Branscombe, 2005). For example, Myrseth and Fishbach (2009) demonstrated that the grid on a calendar induces the concept of a narrow frame and directs peoples’ focus to similarities across alternatives; whereas, a calendar with no grid activates the concept of a wide frame and directs people to seek multiple consumption opportunities. For example, people who are weight watching and use a calendar with a grid restrict themselves to choosing particular kinds of healthy foods, while those who use a calendar without a grid generally eat lots of foods, including indulging in chocolates or potato chips. Similarly, Fishbach and Zhang (2008) presented healthy (e.g., carrots) and unhealthy (e.g., chocolates) foods to health-conscious participants. The foods either were presented together as a unified choice without visual separation or apart from each other as two separate choices (i.e., in two bowls). The findings demonstrated that participants’ food choices were constricted to healthy ones when the options were presented apart, whereas participants accepted both healthy and unhealthy foods when the foods were presented together.

Furthermore, Meyers-Levy and Zhu (2007) found that a high or low ceiling height activated concepts of freedom or confinement, respectively. The sense of freedom induced by an open space encouraged consumers to seek variety, whereas the sense of confinement activated by a closed space led consumers to select specific items. Levav and Zhu (2009) also suggested that confinement within narrow aisles narrowed consumers’ consumption choices. Drawing from this research, the visual frame seems to establish a mental boundary that might influence receivers’ behavior. We propose that a framed logo directs consumers

to consider a brand only within a narrow scope of product categories. Furthermore, the scope of product categories is revealed in both quantity and variety.

H1: The number of products associated with a framed logo is less than those associated with an unframed logo.

H2: The variation of product categories associated with a framed logo is less than those associated with an unframed logo.

H1: The number of products associated with a framed logo is less than those associated with an unframed logo.

H2: The variation of product categories associated with a framed logo is less than those associated with an unframed logo.

A boundary, then, is correlated to people’s use of abstract or concrete ideation. For example, Myrseth and Fishbach (2009) demonstrated that the grid on a calendar induces the concept of a narrow frame and directs people’s focus to the acts in isolation; whereas, a calendar with no grid activates the concept of a wide frame and directs people to pursuit the high-level goals. Meyers-Levy and Zhu (2007) further demonstrated that a ceiling height activated the abstract relational or concrete item-specific processing. People in a high (vs. low) ceiling room identified more shared dimensions (vs. specific items) in a categorization task. A high ceiling encouraged people to compare and evaluate the products by function similarities at a high level rather than feature differences at a low level. Building on this, freeing the logo from the frame is expected to enhance people’s use of abstract ideation at a high construal level in which people tended to identify shared dimensions and the abstract relationship among items; whereas, the logo frame would prompt the uses of concrete ideation at a low construal level. Thus, people are expected to associate products with the

unframed or framed logo at high-level product categories such as cosmetics or at low-level of product categories such as body lotion, respectively. It follows the hypothesis.

H3: Consumers’ associations of high-level product categories with an unframed logo are more than with a framed logo.

Regulatory Focus Theory

Consumers’ perceptions of what belongs in a given category depend on their goals. For example, Barsalou (1982) demonstrated that when people have a specific goal such as purchasing gifts, very different items, such as an album and a necklace, might be viewed as similar. Ratneshwar, Barsalou, Pechmann, and Moore (2001), for instance, demonstrated that when people had a salient health goal, people considered a granola bar closer in similarity to fruit yogurt than to something bearing a visual resemblance, such as a candy bar. The goal of product category was a top-down perspective and could work in concert with the high construal level; whereas the visual resemblance was at a surface-level and similar to the low construal level. The goal-dependent categorization implies the inference that consumers’ regulatory focus may act as a moderator to the logo framing effect on brand categories. This is not only because people with a particular regulatory focus have a distinct goal orientation but because they process information at different levels of construal.

Regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997) points to two coexisting self-regulatory systems motivating people’s decision: promotion and prevention systems. The promotion system regulates nurturance needs and is concerned with growth, advancement, and

accomplishment. People with a strong promotion focus strive toward ideals, desires, and aspirations. In contrast, the prevention system regulates security needs. Individuals with a strong prevention focus care about safety and responsibility. The promotion- and

promotion or prevention focus prefer using an eager approach or vigilant avoidance strategies, respectively (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Ledgerwood & Trope, 2011). The more zealous strategies preferred by promotion-focused people reflect their pursuit of ideals and desire; whereas, the vigilant strategies preferred by prevention-focused people reflect their concerns with safety and responsibility (Scholer & Higgins, 2011). In addition, because

promotion-focused people strive for goal attainment, they have been shown to include as many options as possible in order to achieve their goals. However, because

prevention-focused people concentrate on avoiding mismatches to their goals, they tend to select options only after prudent consideration of details (Scholer & Higgins, 2011). Different focuses on possibilities and details make promotion-focused people more likely to process information at a high construal level which entails identifying shared features and abstract relationship among items, but make prevention-focused people more likely to process information at a low construal level which involves differentiating items from each other (Lee, Keller, & Sternthal, 2010; Zhu & Meyers‐Levy, 2007).

When promotion-focused people process information at a high construal level, the boundary is dissipated, and the associated product categories are therefore broadened. On the contrary, prevention-focused people regulate their thoughts at the low construal level and follow their tendency of vigilant avoidance. So they limit their free associations of brand categories, resulting in a narrower scope. Furthermore, because the logo’s frame implies a brand boundary, when people are self-constrained within a limited scope, as

prevention-focused people are, such an implication would be redundant. In other words, the impact of a logo’s frame on the perceived brand scope would be limited to

prevention-focused people; whereas, the impact would be salient among promotion-focused people. Consequently, one would expect an interaction of the logo’s frame with the regulatory focus on a perceived brand’s scope.

H4: Promotion-focused consumers associate more products with a brand with an unframed logo than a framed logo; however, such an effect is limited among prevention-focused people.

H5: Promotion-focused consumers associate more variations of product categories with the brand that has an unframed logo than a framed logo; however, such an effect is limited among prevention-focused people.

H6: Promotion-focused consumers associate more abstract product categories with a brand having an unframed logo than a framed logo; whereas, such an effect is limited among prevention-focused people.

Study 1. Logo Frame Effect on Brand Association with Activated Regulatory Focus

Study 1 was an exploration of whether the logo’s frame narrowed the perceived brand scope and whether participants’ regulatory focus moderated the effect. Respondents’ free association of brand categories was collected for two aims. The one was, of course, to examine the research hypotheses. The qualitative data could also be used to understand the effect of the logo frame on a perceived brand scope at the beginning of this study.

Furthermore, according to the research literature, the visual boundary may express the confinement and then impact on consumer’s perceptions. The current study would initially explore whether a logo’s frame transmits such concepts of constraint.

Method

Participants and procedure. This study employed a 2 (logo: framed vs. unframed) ×

2 (regulatory focus: promotion vs. prevention) between-subject design with six repeat measurements. One hundred and six undergraduate students (86 females and 20 males), with an average age of 20.42 (SD = 1.22), participated in the experiment in exchange for a

small incentive, US$2. They were randomly assigned into four experimental conditions. Six sets of framed and unframed logos were designed as the stimuli. The only difference in each pair of stimuli was whether the logo was with or without a frame.

The standard procedure of the Self-Guide Priming (Freitas & Higgins, 2002) was followed to activate each participant’s promotion or prevention focus. Then, participants reviewed each logo at their own pace and listed all the products to which the brand could possibly be linked. Their thoughts were counted and coded to indicate the scope of brand categories for further analysis. Participants also rated the feelings of confinement as a result of the logos. The preference of a logo was measured and used as the confounding check. The demographic background was collected at the end.

Prescreening the data. Participants generated a total number of 1,676 products for the

test logos, with an average of 2.64 items per respondent for each logo. To filter the frame effect of the number of products associated with the parent brand, the listed items associated with the logo pattern were excluded from further analysis. This step is to prevent any association induced merely by the shape or pattern of the framed or unframed logos. For example, in a pair of framed and unframed logos, if only the unframed logo was linked to a flower shop but the unframed one was not, the flower shop category was excluded from further analysis because it might come from the shape or pattern of the unframed logo but not the unframed effect, and vice versa. Furthermore, the associated products were

systematically coded by a product categorization list of Global Trade Item Number (GTIN), which is a global and multi-sector standard for the classification of products; the items which were not covered by the GTIN list were excluded. In the end, then, a total number of 1,302 valid responses, with an average of 2.05 items for each logo, were included for further analysis. The number of items excluded from framed and unframed logos did not

significantly differ (according to a GLM with six repeated measurements: F (1, 104) = 2.13,

ns.).

Participants liked the unframed and framed logos equally (M unframed logo= 3.29 vs. M framed

logo= 3.19, F (1, 103) = 1.11, ns.). The potential confounding effect of a logo’s preference

could be eliminated from further analyses. To explore whether the logo’s frame acted as a visual boundary that transmitted a feeling of constraint to consumers, we first analyzed the participants’ perceptions of constraint as a result of the logo. The results of the GLM with six repeated measurements supported the predictions. Participants truly felt more confined by the framed logos than the unframed logos (M = 3.21 vs. 2.85, F (1, 103) = 19.70, p < .001).

Indexing the variance of associated products. To illustrate the hypothesis that

people would associate more diverse products with an unframed logo than with a framed logo, an index was created by the GTIN. Encompassing the hierarchical classification codes (e.g., the highest level: daily commodities; the secondary level: cosmetics; the third level: makeup; the lowest level: lipstick), the GTIN enabled the identification of a product’s diversity under the umbrella of a brand. Because a high product level could cover more product diversity than a low product level could do, the index was developed to represent the level concept: 1,000 × amount of the highest level + 100 × amount of the secondary level + 10 × amount of the third level + amount of the lowest level in this hierarchical schema. The final range of this diversity index was 1 to 2100. The greater number of this index represented the degree to which the respondent associated more diverse products with the brand.

Indexing the abstract level. Respondents were expected to associate products with

the unframed and framed logo at a high- and low-level of product category, respectively. The number of associated products at the highest and secondary levels was divided by the total number of associated products to index a participant’s use of a high-level product

category associated with a particular frame. The final range of this abstract level index was 0 to 1. The greater number represented that the respondent processed the brand extension at a high construal level and provided more abstract product categories.

Results

Generally, participants made more associations to products with an unframed logo (M = 2.31) than a framed one (M = 1.83). The repeat-measured GLM was conducted to examine the logo’s frame effect on the number of products associated with the parent brand. The findings indicated that the logo’s frame constricted the products that a brand could provide (F (1, 102) = 12.25, p < .001). H1 regarding the main effect of the logo’s frame on the number of associated products was supported. In addition, the result indicated that

promotion-focused participants associated more products with the logos than

prevention-focused participants had (M = 2.33 vs. 1.81, F (1, 102) = 14.18, p < .001). The logo’s frame also narrowed the variance of associated products (M unframed logo= 183.44 vs. M

framed logo= 86.05 of the variance index, F (1, 102) = 15.88, p < .001) as expected in H2.

Participants generated more associations with abstract product categories with an unframed logo than a framed logo (M unframed logo= 0.32 vs. M framed logo= 0.24 of the abstract index, F (1,

102) = 4.98, p < .05). Therefore, H3 was supported too.

With regard to H4, the interaction effect of the logo’s frame and the participant’s regulatory focus was significant for the number of associated products (F (1, 102) = 6.73, p < .05). The planned constructs demonstrated that the logo’s frame induced a salient impact on promotion-focused participant’s product association (M unframed logo = 2.76 vs. M framed logo =

1.91; t (49) = 4.31, p < .001), whereas the logo frame did not reveal an impact on the

associations of prevention-focused participants (M unframed logo = 1.87 vs. M framed logo = 1.74; t

(1, 53) = 0.64, ns.). However, such interaction was not found among product diversity (F (1, 102) = 0.01, ns.) and product category level (F (1, 102) = 0.03, ns.). Both promotion and

prevention-focused participants associated more diverse products with an unframed logo than a framed one (promotion focus: M unframed logo = 206.01 vs. M framed logo = 108.96, t (49) = 2.89,

p < .01; prevention focus: M unframed logo = 160.87 vs. M framed logo = 63.14, t (53) = 2.77, p

< .01). The hypothesis regarding the moderating effect of a regulatory focus on the relationship of a logo’s frame and the construal level of the product category was also not supported (promotion focus: M unframed logo = 0.33 vs. M framed logo = 0.26, t (49) = 2.81, ns.;

prevention focus: M unframed logo = 0.30 vs. 0.22, t (53) = 2.39, ns.). The findings supported

that freeing the logo from the frame could encourage promotion-focused participants to draw associations with more products. However, a greater diversity of associated products with the unframed logos than framed ones was found for both promotion and prevention-focused participants. Also, both promotion and prevention-focused participants associated products at more abstract levels while facing unframed logos versus framed ones. No difference was found between two types of regulatory focuses regarding the construal level of the product category.

Discussion

The findings revealed that freeing the logo from the frame could encourage participants to associate with the greater amount and more diverse products at more abstract product categories with the brand (H1, H2, and H3). Regarding the moderating effects of regulatory focus, significant interactions of the logo’s frame and the regulatory focus were found for the number of associated products (H4) but not for the diversity of the product and the product category level (H5 and H6).

The feeling of confinement resulting from framed logos provided an explanation for the findings of the limited number of product associations. The results correspond with the cognitive linguistics research, which indicated that embodied metaphors related to visual features (Johnson, 2008; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999) and therefore influenced human

perception and attitudes. This study primarily suggested that the frame on the logo acted as a metaphor for confinement. Because of this feeling of confinement, the logo’s frame narrowed the number of products associated with the brand.

Priming people’s ideals and oughts induced a promotion and a prevention focus,

respectively (e.g., Freitas & Higgins, 2002; Liberman, Idson, Camacho, & Higgins, 1999). However, Freitas and Higgins (2002) noted the effect of manipulating a promotion and prevention focus on performance (e.g., completing anagrams) was moderated by a participant’s chronic regulatory orientation. Specifically, the effect of a manipulated regulatory focus would be more significant when the manipulated regulatory focus was congruent (as opposed to incongruent) with a participant’s chronic orientation. Keller and Bless (2006) also found such congruence enhanced participants’ cognitive performances. This may be a reason why the regulatory focus exerted a modest influence on the product association task in the current study. Consequently, the regulatory focus was measured as a chronic orientation to investigate its effects on product association in the coming Study 2.

Study 2. Logo’s Frame Effect on Brand Association with Chronic Regulatory Focus

Study 2 had two objectives. The first was to replicate the findings of the first study with different logo stimuli whose colors (i.e., chroma and brightness) and shape (i.e., circular or angular) were further controlled. The second was to examine the moderating effect of an individual’s chronic regulatory focus orientation. A 2 (logo: framed vs. unframed) × 2 (regulatory focus: promotion vs. prevention) between-subject design with six repeat measurements was employed for these objectives.

Method

Participants and procedure. One hundred and eight undergraduate students (89

experiment in exchange for a US$3 reward. They were randomly assigned into two logo frame conditions. Six new sets of framed and unframed logos were designed as the stimuli.

Participants reviewed each logo and listed all the products that the brand could possibly provide at their own pace. Then, participants provided their logo preference, perceived scope, and perceived innovativeness of the brand on 5-point scales. Following the logo evaluation, participants’ regulatory focus was measured by the 10-item scale developed by Haws, Dholakia, and Bearden (2010). The demographic backgrounds were then collected.

Prescreening the data. All participants generated 1,911 responses for the six logos,

with an average of 2.95 items for each logo. As in Study 1, the items were screened and filtered to ensure results came solely from the frames. The products were systematically coded by the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN) list and the items which were not covered by the GTIN list were excluded. Finally, a total number of 1,502 responses, with an average of 2.32 items for each logo, were gathered for further analysis. The number of excluded results of the framed and unframed logos did not significantly differ (t (106) = 0.17, ns.).

Furthermore, respondents liked framed and unframed logos equally (M unframed logo = 3.35 vs.

M framed logo = 3.33; F (1, 110) = 0.04, ns.).

Coding the variance and abstract level of associated products. Following the same

procedures, the indexes for product diversity and product category level were calculated and applied to the tests of H2, H3, H5, and H6.

Dividing participants into promotion- and prevention-focused group. The

participants’ regulatory focus was identified by using the median split in the difference between the promotion and prevention subscale scores (Avnet & Higgins, 2006; Louro, Pieters, & Zeelenberg, 2005). Finally, 51 promotion-focused and 57 prevention-focused people were identified. The promotion-focused participants had higher promotion scores than prevention scores (M = 3.33 vs. 3.05, paired t (50)= 3.67, p < .001); whereas, the

prevention-focused participants had higher prevention scores than promotion scores (M = 3.66 vs. 3.23, paired t (56)= 6.13, p < .001).

Results

As with Study 1, participants associated more products provided by the unframed logos (M = 2.67) than the framed ones (M = 2.01). The repeat-measured GLM was conducted to examine the logo’s frame effect on the number of products associated with the parent brand. The findings indicated that the logo’s frame constricted the number of associated products that a brand could provide (F (1, 104) = 42.80, p < .001). H1 was supported. Furthermore, greater product diversity (M = 183.21 vs. M = 88.88, F (1, 104) = 23.07, p < .001) and more abstract product categories were associated with the unframed logos than the framed ones (M = 0.34 vs. M = 0.26, F (1, 104) = 5.71, p < .05). When people considered the brand at a more abstract level, they had a wider product scope. The main effect of the logo’s frame on the diversity and the abstract level, H2 and H3 were supported.

The significant interaction of the logo’s frame and the participant’s regulatory focus was found in the number of associated products (F (1, 104) = 15.73, p < .001) and product

diversity (F (1, 104) = 6.99, p < .01) but not on the product category level (F (1, 104) = 2.22,

ns.). The planned contrasts were performed to test H4 to H6. The results demonstrated

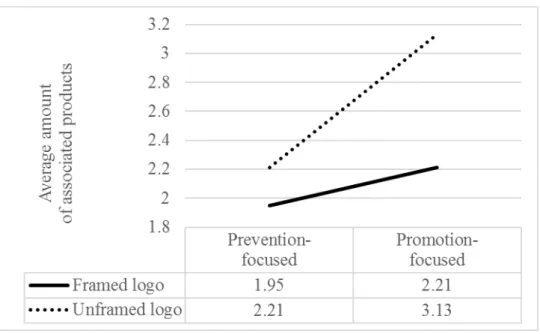

that promotion-focused participants generated associations with more products provided by the brand with an unframed than the one with a framed logo (M = 3.13 vs. 2.21, F (1, 49) = 8.37, p < .001). However, such differences were not found among prevention-focused participants (M = 2.21 vs. 1.95, F (1, 55) = 1.69), as expected in H4. The findings were shown in Figure 1.

Promotion-focused people associated more diverse products with the unframed logos than the framed logos (M unframed logo = 252.91 vs. M framed logo =100.03, F (1, 49) = 18.79, p

106.38 vs. M framed logo = 66.88, F (1, 55) = 4.45, p < .05). The interesting but slightly

unexpected result showed that freeing the logo from the frame could enhance both promotion and prevention-focused participants to consider more diverse products. The results were demonstrated in Figure 2.

Furthermore, although the interaction effect on the construal level of product categories was not significant, a direct test of the planned contrast was still performed on the abstract level index for H6. The results showed that promotion-focused people associated items for the unframed logos at a more abstract level than those for the framed logos (M = 0.39 vs. 0.26,

F (1, 49) = 6.27, p < .05). But, such differences were not found for prevention-focused

participants (M = 0.26 vs. 0.29, F (1, 55) = 0.49, ns.). The planned contrast results supported H6.

Fig. 1. The average amount of products associated with the framed and unframed logos by promotion- and prevention-focused participants

Fig. 2. The product diversity index with the framed and unframed logos by promotion- and prevention-focused participants

Fig. 3. The abstract level index with the framed and unframed logos by promotion- and prevention-focused participants

The ratings on the perceived brand scope and brand innovation provided additional support for the argument that freeing the logo from its frame could lead consumers to perceive that the brand has a broad scope and is innovative; consequently, such a perception suggests a benefit to the new extension. As expected, participants rated the brand with an unframed logo as having a wider product scope and as being more innovative than the one with a framed logo (perceived brand scope: M = 3.12 vs. 2.87, F (1, 104) = 5.92, p < .05; perceived innovativeness: M = 3.40 vs. 3.06, F (1, 104) = 15.24, p < .001). The results also revealed a moderating effect through people’s regulatory focus. The planned contrasts demonstrated that promotion-focused respondents perceived the brand with an unframed logo as possessing a broader product scope and as being more innovative than the brand with a framed logo (perceived brand scope: M = 3.17 vs. 2.81, F (1, 49) = 5.46, p < .05; perceived innovativeness: M = 3.43 vs. 2.96, F (1, 49) = 11.51, p < .01). However, the

prevention-focused participants evaluated the brands with unframed and framed logos as having an equal scope (F (1, 55) = 1.03, ns.) and level of innovation (F (1, 55) = 3.91, ns.).

Discussion

The results of Study 2, similar to Study 1, supported the view that freeing the logo from its frame encourages participants to associate more products with the parent brand. The findings likewise demonstrated that participants associated more diverse products at an abstract product level with the brand having an unframed than a framed logo. Such impacts were more significant for promotion than prevention-focused people; the interaction effects were more salient in Study 2 with regard to chronic tendencies than Study 1 with the manipulation of regulatory focus.

The findings of Study 1 and 2 implies that freeing the logo from the frame may benefit the fit perception of upcoming new extensions because an unframed logo encourages consumers to include more products under the parent brand and push the brand image to a

more abstract level than a framed logo. Consumers who process the brand at an abstract level may also be more accepting of new products. Based on these supports, Study 3 was designed to directly examine the impact of the logo’s frame and the moderating effects of regulatory focus on the perceived fit of brand extensions.

Study 3. Logo Frame Effect on Perceived Fit of Brand Extension

The perceived fit of the brand extension stems from the concept of family resemblance. Family resemblance refers to the degree to which a category member has attributes in

common with other category members (Rosch & Mervis, 1975). Because a brand linked with diverse products can carry more attributes shared by original and extended products, the perception of such resemblances should be able to enhance the perceived fit of the new extension. Klink and Smith (2001) and Oakley, Duhachek, Balachander, and Sriram (2008) showed that multiple product exposures increased the perceived fit of the coming new

extension.

It is logical to assume that when a consumer processes a brand extension at a high construal level, the perceived common attributes between the extension and the brand should increase. Park, Milberg, and Lawson (1991), for example, found that a low perceived fit of extension occurred when consumers’ categorization processes were based on similarities in a product’s features, whereas a high perceived fit took place when people process the extension based on concept consistency. More directly, Volckner and Sattler (2006) found that

linking an extension to the abstract brand’s image could overcome the initial perception of a low category fit.

As found in Study 1 & 2, a high or low level of product categories are associated with a brand with an unframed or framed logo, respectively. A new extension is expected to fit more with a brand at a high product category than at a low product category. Therefore,

consumers are expected to perceive a new extension under a parent brand with an unframed logo better than the one with a framed logo because an unframed logo can carry more

products, imply a greater diversity of products and contain higher levels of product categories than a framed logo.

H7: Consumers perceive the new extension as having a greater fit with the parent brand with an unframed logo than with a framed logo.

Because promotion-focused people are expected to associate more products and higher product categories with the brand having an unframed than a framed logo, they accordingly perceived a new extension as having a greater fit when the brand logo is unframed than the when it is framed. Following the same logic, because prevention-focused people are

self-constrained by their chronic orientation, freeing the logo frame may exert a limited effect on their fit perception of the new extension.

H8: Promotion-focused consumers perceive the extension as having a greater fit with the brand with an unframed logo than the one with a framed logo; however, such an effect is limited among prevention-focused consumers.

Method

Study 3 employed a 2 (logo: framed vs. unframed) (shown in Appendix A) × 2 (regulatory focus: promotion vs. prevention) between-subject design with three repeat measurements to test the above hypotheses.

Materials. Three sets of logos employed in Study 2 were selected as the stimuli in the

current study. The product most associated with each chosen logo was selected to be the original product category of the parent brand. As a result, the three logos represented sanitary pads, cookies, and shampoos under three fictitious names. Far extensions of these original products were chosen to avoid a ceiling effect. Drawing the insight from the calculation of ontological distance noted in Markman and Gentner (1993), the far extension was defined as the product with the seventh ontological distance to the parent brand. The ontological distance of a pair was represented as the number of nodes in the ontology tree that had to be traversed to get from one to the other. Consequently, pajamas, energy drinks, and hair dryers were chosen to be the new extension for the brands of sanitary pads, cookies, and shampoos, respectively.

Participants and procedure. One hundred and seventeen undergraduate students (71

females and 46 males), with an average age of 20.60 (SD = 2.30), participated in the

experiment in exchange for a US$2 reward. They were randomly assigned into two framed logo conditions.

Participants reviewed each parent brand and its extension and then rated the perceived fit of the extension on eight 7-point items. The items were (1) it is a good idea for the brand to launch this new extension, (2) launching this new extension is a proper move for this brand, (3) the new extension will be popular in the market, (4) I like the new extension, (5) the new product looks good quality, (6) I trust the brand, (7) I am willing to recommend this new extension to my friends who need it, and (8) I will purchase this new extension if I need one.

Then, participants rated the manufacturing difficulty of the extended products. Finally, participants filled the Haws, Dholakia, and Bearden (2010) regulatory focus scales. The demographic background was then collected.

Dividing participants into promotion and prevention-focused group. The

participants’ regulatory focus was identified by using the median split in the difference between scores for the promotion and prevention subscales. Thirteen participant’s scores were equal to the median, so these participants were excluded from the further analysis. Consequently, 51 promotion-focused and 57 prevention-focused people were identified. The promotion-focused participants had higher promotion scores than prevention scores (M = 3.33 vs. 3.05, paired t (50) = 3.67, p < .001); whereas, the prevention-focused participants had

higher prevention scores than promotion scores (M = 3.66 vs. 3.23, paired t (56) = 6.13, p

< .001).

Results

A principle component analysis was initially conducted on the eight items regarding the perceived fit of the new extension. One component was extracted for each brand extension condition (eigenvalues: 5.50, 5.10, and 5.86). The Cronbach’s alpha for these eight items were .94. Thus, the eight items were averaged to represent the overall perceived fit of the new extension.

Participants had an equal preference for the three sets of unframed and framed logos (t (55) = 0.90, 0.61, 0.27, and 0.58; ns.). The perceived similarities of the original product category and its extension had no difference between the unframed and framed logos (t (55) = 0.21, 1.33, and 0.84; ns.). No confounding effect from the preference of the logo design or the product’s similarities was found. However, the manufacturing difficulties of the extensions for the framed and unframed logo groups were different (pajama: t (55) = 2.08, p < .05; energy drink: t (55) = 1.58, ns.; hair dryer: t (55) = 1.73; ns.). It seems that a framed

logo might prompt a view that making the product would be difficult. Although only the pajamas reached significant differences in manufacturing difficulty under framed versus unframed logos, the manufacturing difficulty of the extensions was included in the tested hypothesis as a covariate to eliminate the unnecessary confounding effect.

The 2 × 2 ANCOVA was conducted to examine the effects of the logo’s frame and participant’s regulatory focus on the perceived fit, with the manufacturing difficulty as a covariate. The covariate, i.e., manufacturing difficulty, did not significantly influence the perceived fit of the new extension (pajama: F (1, 99) = 0.69, ns.; energy drink: F (1, 99) = 0.06, ns.; hair dryer: F (1, 99) = 1.28, ns.).

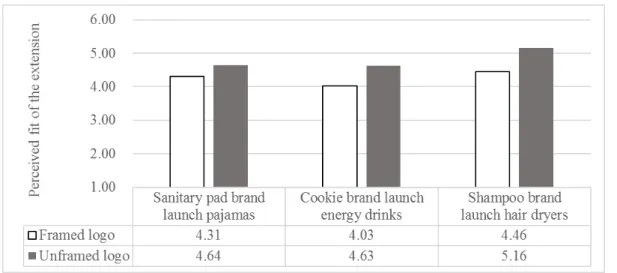

Consistent results were found in the three brand extension conditions. As expected, the logo’s frame disadvantaged the perceived fit of an extension (pajama: F (1, 99) = 2.91, p = .09; energy drink: F (1, 99) = 9.76, p < .01; hair dryer: F (1, 99) = 12.57, p < .001). H7 was supported. The main effects of the regulatory focus were found only when participants evaluated the pajamas launched by the sanitary pad brand (pajama: F (1, 99) = 5.67, p < .05; energy drink: F (1, 99) = 1.77, ns.; hair dryer: F (1, 99) = 1.81, ns.).

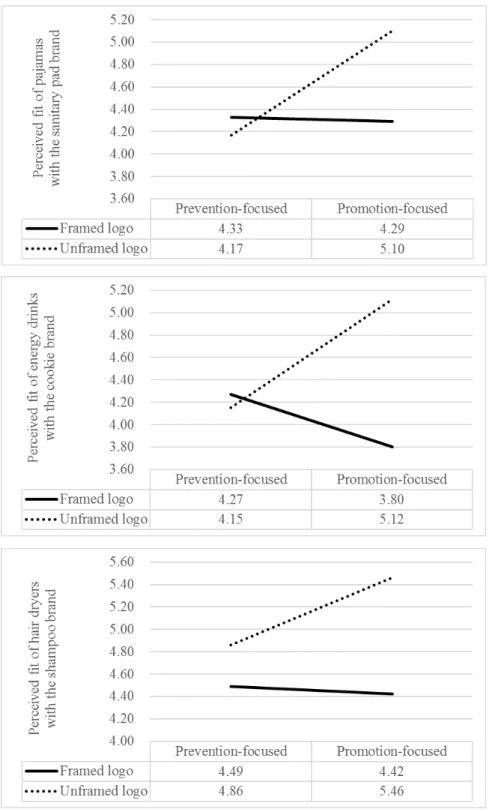

The interaction of the logo’s frame and the regulatory focus on the perceived fit were significant or close to significant (pajama: F (1, 99) = 2.91, p = .09; energy drink: F (1, 99) = 9.76, p < .01, and hair dryer: F (1, 99) = 12.57, p < .001). The planned contrasts

demonstrated that freeing the logo from the frame could encourage promotion-focused participants to perceive the extension as having a greater fit with its parent brand (pajama: F (1, 50) = 8.39, p < .01; energy drink: F (1, 50) = 25.99, p < .001; hair dryer: F (1, 50) = 11.03,

p < .01). However, such benefits were not found for prevention-focused participants

(pajama: F (1, 48) = 0.40, ns.; energy drink: F (1, 48) = 0.14, ns.; hair dryer: F (1, 48) = 2.29,

ns.). The findings supported H8 that breaking the visual boundary of the logo could

encourage promotion-focused consumers to have a high perceived fit for the new extensions, whereas such benefits were limited among those with a prevention focus.

Fig. 5. The perceived fit of the extension with the framed and unframed logos by promotion- and prevention-focused participants

Following the findings of Study 1 and 2, that unframed logos could encourage more product associations, Study 3 directly applied this proposition to the scenario of brand extensions. The results of Study 3 supported the view that freeing the logo from its frame evoked a perceived fit for the new extensions. However, such benefits were found for promotion but not prevention-focused consumers.

General Discussions

This research focused on a specific design feature, the logo’s frame, in order to investigate its effects on product associations and further on a perceived fit with brand extensions. The logo’s frame indicated a visual boundary which implicitly limited the consumer’s capacity for free association and his or her acceptance of new things.

In Study 1 and 2, participants could associate more products with the parent brand when the logo frame was removed. Participants also associated more diverse products at an abstract product level when the brand had an unframed rather than a framed logo. The more multiple and diverse products the parent brand has, the more attributes a new extension shares with the brand members. Such perceptions of resemblance enhance the perceived fit of the new extension. Furthermore, the high or low level of product categories was

associated with the brand having an unframed or framed logo, respectively. This result corresponded to Park, et al. (1991) and Volckner and Sattler (2006): consumers perceived a new extension as having a greater fit at a higher rather than a lower construal level (e.g., brand image vs. product features). With Study 3, the propositions regarding the perceived fit of a brand extension were supported.

Consumers’ regulatory focus acted as a moderator in the above relationships. The impact of a logo’s frame on the brand perception and perceived fit of a new extension was more salient for promotion than prevention-focused participants. It seems that the

self-limitation of prevent-focused consumers dominates their reactions, no matter if the logo was with or without a frame. Generally speaking, removing the logo’s frame can benefit brand extension from increasing the acceptance of promotion-focused consumers. However, an unframed logo cannot benefit such extensions when consumers maintain a prevention focus.

Although marketers may have difficulty in identifying the regulatory focus of the customers, this interaction result may be applied to hope-related products, for example, cosmetics, healthy food, and baby products, because customers tend to focus more on growth, advancement, and accomplishment while considering these types of products. If this

derivation is true, hope-related products ought to employ an unframed logo. Brand managers should take this insight into consideration. Further research on this issue is expected.

At first glance, it seems that unframed logos are better than the framed ones due to the extension potential. However, it has to be remembered that the preferences of framed and unframed logos were found to be similar in these studies. Indeed, another interesting finding was that consumers perceived products with framed logos as being slightly more difficult to make than products with unframed logos. It is possible that framed logos send out the message of being firmly principled, disciplined, and precise, which accounts for the feeling of production difficulty. If a brand can handle this difficulty well, the image of trustworthy and expertise may be created under a framed logo. This additional finding suggests that more research into the image associations of framed versus unframed logos deserves to be conducted.

Reference

Arslan, F. M., & Altuna, O. K. (2012). Which category to extend to product or service?

Journal of Brand Management, 19, 359-376.

Avnet, T., & Higgins, E. T. (2006). How regulatory fit affects value in consumer choices and opinions. Journal of Marketing Research, 43, 1-10.

Barsalou, L. (1982). Context-independent and context-dependent information in concepts.

Memory & Cognition, 10, 82-93.

Burris, C. T., & Branscombe, N. R. (2005). Distorted distance estimation induced by a self-relevant national boundary. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 305-312.

Chattopadhyay, A., Gorn, G. J., & Darke, P. (2010). Differences and similarities in hue preferences between Chinese and Caucasians. Sensory Marketing: Research on the

sensuality of products, 219-239.

Cian, L., Krishna, A., & Elder, R. S. (2014). This logo moves me: Dynamic imagery from static images. Journal of Marketing Research, 51, 184-197.

Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 69, 117-132.

Cutright, K. M. (2012). The beauty of boundaries: When and why we seek structure in consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 38, 775-790.

Doyle, J. R., & Bottomley, P. A. (2006). Dressed for the occasion: Font-product congruity in the perception of logotype. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16, 112-123.

Dwivedi, A., Merrilees, B., & Sweeney, A. (2010). Brand extension feedback effects: A holistic framework. Journal of Brand Management, 17, 328-342.

Fishbach, A., & Zhang, Y. (2008). Together or apart: When goals and temptations complement versus compete. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 547-559.

Freitas, A. L., & Higgins, E. T. (2002). Enjoying goal-directed action: The role of regulatory fit. Psychological Science (Wiley-Blackwell), 13, 1-6.

Gorn, G. J., Jiang, Y., & Johar, G. V. (2008). Babyfaces, trait inferences, and company evaluations in a public relations crisis. Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 36-49. Hagtvedt, H. (2011). Applying art theory to logo design: The impact of incomplete typeface

logos on perceptions of the firm. Advances in Consumer Research, Asia-Pacific

Conference Proceedings, 9, 28-29.

Hem, L. E., & Iversen, N. M. (2004). How to develop a destination brand logo: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 4, 83-106. Henderson, M. D., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Oettingen, G. (2007). Implementation intentions and disengagement from a failing course of action. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making,

20, 81-102.

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280-1300. Higgins, E. T. (2008). Culture and personality: variability across universal motives as the

missing link. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 608-634.

Janiszewski, C. (2001). Effects of brand logo complexity, repetition, and spacing on processing fluency and judgment. Journal of Consumer Research, 28, 18-32.

Jiang, Y., Gorn, G. J., Galli, M., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2015). Does your company have the right logo? How and why circular- and angular-logo shapes influence brand attribute judgments. Journal of Consumer Research. In press.

Johnson, M. (2008). The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding: University of Chicago Press.

Keller, J., & Bless, H. (2006). Regulatory fit and cognitive performance: the interactive effect of chronic and situationally induced self-regulatory mechanisms on test performance.

European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 393-405.

Klink, R. R. (2003). Creating meaningful brands: The relationship between brand name and brand mark. Marketing Letters, 14, 143-157.

Klink, R. R., & Smith, D. C. (2001). Threats to the external validity of brand extension research. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 38, 326-335.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its

challenge to western thought: Basic books.

Ledgerwood, A., & Trope, Y. (2011). Local and global evaluations: Attitudes as

self-regulatory guides for near and distant responding. Handbook of self-regulation:

Research, theory, and applications, 226-243.

Lee, A. Y., Keller, P. A., & Sternthal, B. (2010). Value from regulatory construal fit: The persuasive impact of fit between consumer goals and message concreteness. Journal of

Consumer Research, 36, 735-747.

Levav, J., & Zhu, R. (2009). Seeking freedom through variety. Journal of Consumer

Research, 36, 600-610.

Liberman, N., Idson, L. C., Camacho, C. J., & Higgins, E. T. (1999). Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 77, 1135-1145.

Loken, B., & John, D. R. (1993). Diluting brand beliefs: When do brand extensions have a negative impact? Journal of Marketing, 57, 71-84.

Louro, M. J., Pieters, R., & Zeelenberg, M. (2005). Negative returns on positive emotions: The influence of pride and self-regulatory goals on repurchase decisions. Journal of

Markman, A. B., & Gentner, D. (1993). Splitting the differences: A structural alignment view of similarity. Journal of Memory and Language, 32, 517-535.

Meyers-Levy, J., & Zhu, R. (2007). The influence of ceiling height: The effect of priming on the type of processing that people use. Journal of Consumer Research, 34, 174-186. Myrseth, K. O. R., & Fishbach, A. (2009). Self-control: A function of knowing when and

how to exercise restraint. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 247-252. Nijssen, E. J., & Agustin, C. (2005). Brand extensions: A manager's perspective. Journal of

Brand Management, 13, 33-49.

Oakley, J. L., Duhachek, A., Balachander, S., & Sriram, S. (2008). Order of entry and the moderating role of comparison brands in brand extension evaluation. Journal of

Consumer Research, 34, 706-712.

Park, C. W., Milberg, S., & Lawson, R. (1991). Evaluation of brand extensions: The role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency. Journal of Consumer

Research, 18, 185-193.

Patrick, V. M., & Hagtvedt, H. (2011). Aesthetic incongruity resolution. Journal of

Marketing Research, 48, 393-402.

Ratneshwar, S., Barsalou, L. W., Pechmann, C., & Moore, M. (2001). Goal-derived categories: The role of personal and situational goals in category representations.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 10, 147-157.

Rompay, T. V., Hekkert, P., Saakes, D., & Russo, B. (2005). Grounding abstract object characteristics in embodied interactions. Acta Psychologica, 119, 315-351.

Rosch, E., & Mervis, C. B. (1975). Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573-605.

Scholer, A. A., & Higgins, E. T. (2011). Promotion and prevention systems: Regulatory focus dynamics within self-regulatory hierarchies. Handbook of self-regulation: Research,

theory, and applications, 143-161.

Starbucks (2010). Starbucks’ famous Siren gets coffee break, while Seattle’s best coffee takes over. In Starbuck.com.

Starbucks (2015). Ten facts about Starbucks evenings stores. In Starbucks.com.

Vaughn, L. A., Baumann, J., & Klemann, C. (2008). Openness to experience and regulatory focus: Evidence of motivation from fit. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 886-894. Volckner, F., & Sattler, H. (2006). Drivers of brand extension success. Journal of Marketing,

70, 18-34.

Zhang, S., & Sood, S. (2002). "Deep" and "surface" cues: brand extension evaluations by children and adults. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 129-141.

Zhu, R., & Meyers‐Levy, J. (2007). Exploring the cognitive mechanism that underlies regulatory focus effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 34, 89-96.

日期:2017/01/26

科技部補助計畫

計畫名稱: 消費者如何從品牌識別標誌設計中知覺公司的品牌延伸能力 計畫主持人: 別蓮蒂 計畫編號: 104-2410-H-004-128- 學門領域: 行銷無研發成果推廣資料

計畫主持人:別蓮蒂 計畫編號: 104-2410-H-004-128-計畫名稱:消費者如何從品牌識別標誌設計中知覺公司的品牌延伸能力 成果項目 量化 單位 質化 (說明:各成果項目請附佐證資料或細 項說明,如期刊名稱、年份、卷期、起 訖頁數、證號...等) 國 內 學術性論文 期刊論文 0 篇 研討會論文 1

Chen, Yu-Shan Athena and Lien-Ti Bei (2016). “Structured Abstract: How the Logo Frame Impacts on Brand Extension,” in Academy of

Marketing Science Annual

Conference, May 18-20, Orlando, Florida, USA. 專書 0 本 專書論文 0 章 技術報告 0 篇 其他 0 篇 智慧財產權 及成果 專利權 發明專利 申請中 0 件 已獲得 0 新型/設計專利 0 商標權 0 營業秘密 0 積體電路電路布局權 0 著作權 0 品種權 0 其他 0 技術移轉 件數 0 件 收入 0 千元 國 外 學術性論文 期刊論文 0 篇 研討會論文 0 專書 0 本 專書論文 0 章 技術報告 0 篇 其他 0 篇 智慧財產權 及成果 專利權 發明專利 申請中 0 件 已獲得 0 新型/設計專利 0 商標權 0

著作權 0 品種權 0 其他 0 技術移轉 件數 0 件 收入 0 千元 參 與 計 畫 人 力 本國籍 大專生 0 人次 碩士生 0 博士生 0 博士後研究員 1 陳玉珊 專任助理 0 非本國籍 大專生 0 碩士生 0 博士生 0 博士後研究員 0 專任助理 0 其他成果 (無法以量化表達之成果如辦理學術活動 、獲得獎項、重要國際合作、研究成果國 際影響力及其他協助產業技術發展之具體 效益事項等,請以文字敘述填列。)