On: 24 April 2014, At: 18:27 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Total Quality Management & Business

Excellence

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctqm20

Applying the Kano model and QFD to

explore customers' brand contacts in

the hotel business: A study of a hot

spring hotel

Kuo-Chien Chang a & Mu-Chen Chen b a

Department of Sports, Health and Leisure , Chihlee Institute of Technology , Banciao City, Taipei County 220, Taiwan (ROC) b

Institute of Traffic and Transportation , National Chiao Tung University , Taipei 100, Taiwan (ROC)

Published online: 19 Feb 2011.

To cite this article: Kuo-Chien Chang & Mu-Chen Chen (2011) Applying the Kano model and QFD to explore customers' brand contacts in the hotel business: A study of a hot spring hotel, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 22:1, 1-27, DOI: 10.1080/14783363.2010.529358

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2010.529358

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

and-conditions

Applying the Kano model and QFD to explore customers’ brand

contacts in the hotel business: A study of a hot spring hotel

Kuo-Chien Changa∗ and Mu-Chen Chenb

a

Department of Sports, Health and Leisure, Chihlee Institute of Technology, Banciao City, Taipei County 220, Taiwan (ROC);bInstitute of Traffic and Transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taipei 100, Taiwan (ROC)

Brand contacts are a variety of elements about how customers come into contact with a brand and how they communicate their values about it to other potential customers. For the sake of cost and efficiency, brand contacts can be investigated not only from a customer perspective but also from that of the service provider. This paper thus attempts to integrate the Kano model and quality function deployment (QFD) to explore brand contact elements. The results gained from an empirical study of a hot spring hotel indicate that customers’ perceptions about contact elements are mostly classified into one-dimensional and must-be attributes by the Kano model. The proposed approach contributes to the creation of attractive contact elements that have an enormous potential to further increase customer satisfaction and differentiate competitors. Moreover, along with the 10 technical characteristics obtained by the integrated approach, the customers’ contact experiences are displayed through the brand contact priority grid, both of which provide references for future hotel business development. Lastly, atmosphere-oriented brand contacts dominate customers’ brand perceptions more than others, in that they lessen customers’ sense of risk and uncertainty toward product/service offerings. A discussion of the findings including managerial implications is also presented in this paper.

Keywords:brand contact; Kano model; quality function deployment (QFD); customer experience; sense of risk and uncertainty; hot spring hotel

If we can take into account the way a customer experiences and judges the brand, we have the information we need to design and implement a compelling brand experience. (Fortini – Campbell, 2003, p. 54)

Introduction

A brand is a value indicator of a firm’s products and services. It is not just a name, nor is it simply a logo or symbol (Keegan, 2002). Brands can be seen as an asset of a company along with products, channels, delivery, image, customers, visual identification and sales (Schultz, 2000). That is, the brand represents consistent values. It creates eternal value for customers, while at the same time producing financial value for management and stakeholders (Schultz & Schultz, 2000). Hence, the brand should be a leading measure for an organisation, both internally and externally.

ISSN 1478-3363 print/ISSN 1478-3371 online # 2011 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/14783363.2010.529358 http://www.informaworld.com

∗Corresponding author. Email: kcchang@mail.chihlee.edu.tw

Although the focus on brand related issues has predominantly stressed brand power (such as brand equity and brand loyalty) and how it benefits a firm (e.g. Kataman & Arasli, 2007; Kim & Kim, 2004), an increasing number of studies have started to explore the question, ‘where do great brands come from?’ in terms of the nature of a brand (e.g. Chattopadhyay & Laborie, 2005; Fortini-Campbell, 2003; Schultz, 1998). This argument refers to how customers make their assessment after encountering a brand. In other words, a brand is formed by all the experiences of the customers with the firm’s core and peripheral offerings. The areas in which various forms of brand infor-mation are evaluated and interpreted by customers are called either brand contact points, touch points or moments of truth (Fortini-Campbell, 2003). As suggested by Schultz (1998), brand contacts are not merely based on advertising, sales promotions or direct mar-keting, but involve all the ways a customer comes in contact with a firm. Thus, main brand contacts are the key to making a good impression. Every product and service is both a channel and a brand contact, and so business operators should make use of product and service offerings to deliver a consistent message and to establish an accurate image for customers. To be clear, a brand is designed and built layer by layer over time, whereas a brand contact could be any element of the customer’s experience that the customer will attribute to the brand (Fortini-Campbell, 2003).

The developing trend in the service sector is exactly in accordance with the notion of the progression of economic value proposed by Pine and Gilmore (1998, 2004), and is proceeding toward the stage of the experience economy. Since experiences are as economically different from services as services are from goods (Williams, 2006), a service firm must orchestrate memorable events for its customers. The more that needed and relevant events are experienced by customers, the stronger the competitive advantage of the firm. This advantage is, in turn, beneficial for improving the firm’s pricing programmes. For example, one emerging experience industry, the hot spring industry, instead of merely selling the related commoditities of hot spring resources, has been making efforts to construct various bathing spaces and facilities, magnificent environ-ments and customised services in order to create multiple pleasant experiences for their clients while they enjoy their stay. Consequently, as customers’ purchasing behaviour tends to support certain ‘name brand’ products, service firms such as hot spring hoteliers also expect to shape their own ‘brand’ concept in the customers’ mind by way of providing a well-established hot spring experience (Hou, 2005). In other words, the better the experience of the customers, the better the message of the brand delivered to their mind (Daun & Klinger, 2006).

In light of the aforementioned discussion, in order to achieve branding success that creates a competitive advantage for a firm, listening closely to customers’ considerations is recommended. Consequently, although there is no shortage of studies on the issue of brand contact elements from the viewpoints of the customer, little concern has been paid to the question of collectively reconciling all the different versions of desirable contact elements in terms of the customer and the firm. For example, although previous scholars (e.g. Chattopadhyay & Laborie, 2005; Fortini-Campbell, 2003) have presented outstanding methods to illustrate how to acquire the key contact elements from a customer perspective, they have not clearly articulated how customer-oriented contact elements would be prioritised by the firm for the sake of efficiency (Shen, Tan, & Xie, 2000), i.e. at a minimum cost, but with maximal positive impact. This argument refers to an approach that pays attention to the points that, from the perspectives of the customer and the firm, identify the most effective set of contact elements in which to invest, thereby satisfying the customer.

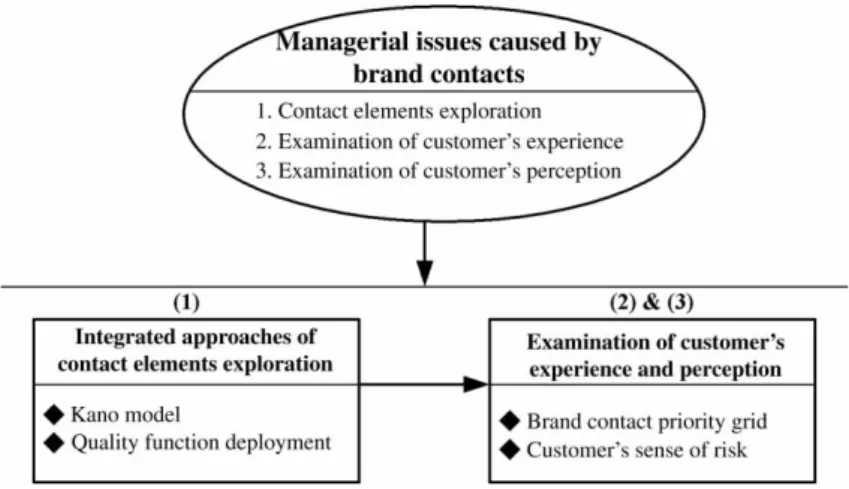

Since the late 1990s, an integrated approach that combines the Kano model with QFD (e.g. Matzler & Hinterhuber, 1998; Tontini, 2007) can be applied to solve the challenge of contact element exploration. This approach has been used for the following reasons. First, as stated by Sireli, Kauffmann, and Ozan (2007, p. 380), the ‘Kano model uniquely identifies customer requirements (CRs) in detail by assigning different categories to different requirements, and can provide a more accurate voice of the customer (VOC) as an input to QFD analysis’. Second, as one of the most powerful TQM tools (Raharjo, Xie, Goh, & Brombacher, 2007), in the QFD model, the sub-matrix of hows functioning as the design requirement of the firm can be used to determine demand from the VOC (i.e. the sub-matrix of whats). This means that the correlation between the hows and the whats shows the extent to which each design requirement of the firm affects each customer need (Shen et al., 2000; Tan & Pawitra, 2001). Third, this integrated approach has been extended beyond its initial concept and has been used in service fields and utilised for service excellence development (Tan & Pawitra, 2001). In summary, the Kano model is used to acquire the desired contact elements from customers while QFD is employed to take the identified elements into design with the compromise of the provider’s capability and profitability. Thus, this integrated approach is suitable for brand contact exploration in the hotel business based on the perspectives of customers and service providers. Accordingly, this study aims to achieve the following research objectives: to empirically explore the contact elements of a brand by incorporating an integrated approach using the Kano model and the QFD technique, and to clarify how contact elements deliver brand messages to customers for their judgments which in turn shape the brand of the firm.

Literature review

For constructing the research framework and conducting the research, this section reviews the related literature consisting of brand contacts and managerial issues, brand contact realms, the Kano model and QFD, and an examination of brand contact experiences and perceptions.

Brand contacts and managerial issues

As mentioned above, brand contact dominates the brand management literature, and contact elements are a major criterion for the assessment of a brand. Several articles focused on contact elements as the indicators of building a firm’s brand, while other articles, in addition to the discussion of contact elements exploration, took an interest in understanding the effects of contact elements on customers’ perceptions toward a firm’s service and product offerings.

Along with a review of the literature (see Carlzon, 1987; Chattopadhyay & Laborie, 2005; Clark, 1993; Devlin & Dong, 1994; Flipo, 1988; Fortini-Campbell, 2003; Hartline & Jones, 1996; Logman, 2004; McDougall & Snetsinger, 1990; Schultz, 1998; Wakefield & Blodgett, 1999; Schultz & Schultz, 2000), this study describes three managerial issues resulting from brand contact. First, brand contacts are a variety of elements by which customers and potential customers meet the brand. Second, the more the product/ service offerings meet the customers’ requirements, even going beyond their expectations, the greater the customers’ experiences with the brand. Third, among the various contact elements, the more that desired contact elements are perceived by customers, the lower the customers’ feelings of risk and uncertainty with respect to the brand.

Brand contact realms: model construction and practice

Brand contacts are taken as the basis of a business operation because any product and service element of a business that the customer regards is one of those brand contact points. These contacts influence a customer’s future consuming intention and support and, in turn, establish their loyalty toward the firm. Specifically speaking, brand contacts are influential in retaining the target customers of a firm (Schultz, 1998). Thus, ‘emphasising necessary brand contacts’ is very important when trying to efficiently make target customers notice and accept product and service characteristics and to further catch their attention. Main brand contact realms are the key to forming a good impression. Business operators should take this into consideration in order to deliver a consistent message that customers will incorporate into their experiences.

Regarding the issue of customers’ brand encounters, Chattopadhyay and Laborie (2005) have proposed that customers’ brand contact experiences, based on the specific benefits of the brand, should be conveyed via certain kinds of contacts, i.e. the comprehen-sion or specific meaning of the offerings, as perceived by the customer, is influenced by the contact. Since the customer benefit concept will bundle functional, effectual, and psycho-logical features (Bateson, 1979), the benefits that are related to brands can be divided into two types, performance benefits and emotion benefits. Extending from the idea of Miller and Foust (2003), performance benefits can be defined as ‘an intrinsic effect of the service offerings’ while emotion benefits can be defined as ‘the processes and positive con-sequences of service consumption’. Besides, contacts that connect with brands in terms of the nature of service actions can be divided into two forms, tangible actions and intangible actions described as following (Lovelock, 1994, p. 13 – 14): ‘Tangible actions are those in which customers must physically become involved in the service system because they are an integral part of the process. They cannot obtain the benefits they desire by dealing at arm’s length with providers. Instead, they must be prepared to spend time interacting and actively cooperating with service providers. Besides, services interact with the mindset of the customers through intangible actions. Anything that affects a person’s mind has the power to shape attitudes and influence behaviour. They have to be mentally in communication with the benefits being presented’. Consequently, the brand contact model consisting of the two bi-polar constructs (i.e. tangible and intangible actions along with performance and emotion benefits) experienced by customers is outlined.

Moreover, in terms of the concept of the progression of economic value proposed by Pine and Gilmore (1998), there are four levels of offerings (i.e. from goods, services, experiences and transformations) in which the different stages create a different experience for the customers and where the offerings in each stage have their specific competitive position in a market. Similarly, the contacts in the brand contact model can be sorted according to their stage into four contact realms based on the two bi-polar constructs. The four kinds of content realms within the brand contact model for grouping key contact elements are shown in Figure 1, and are namely Facility-Oriented Contact, Atmosphere-Oriented Contact, Service-Oriented Contact, and Image-Oriented Contact. For example, in the hot spring hotel business the product of hot spring space belongs to the subject of goods and is a type of Facility-Oriented Contact. The management waiting at the front entrance of the hot spring pool belong to the subject of service by being a type of Service-Oriented Contact. A feeling of satisfaction is felt by the natural scenery surrounding the hot spring hotel, thereby creating a type of Atmosphere-Oriented Contact, and the event’s association with health benefits belongs to the subject of trans-formation, and is an Image-Oriented Contact. The four contact realms are discussed in the following paragraphs in which each classification indicates its unique contact subjects.

A Facility-Oriented Contact concerns ‘tangibles that are directly or peripherally parts of a service’ (Berry & Clark, 1986, p. 54). This concept suggests that tangible facilities that are directly or peripherally part of a service can be brought into focus through physical contact. Mittal and Baker (2002) proposed that physical representation shows the physical components of services, and suggested that it would benefit service providers to identify some physical entities that would most effectively represent the desired value to customers, and to use those entities to give substance and meaning to their customers. The authors believed that a service provider must deliver services to their customers by means of presenting the substance of their service (e.g. the luxurious bed). Besides, some examples in Levitt’s (1981) study explained the notion of physical representation, such as hotels wrapping their drinking glasses in fresh bags or film, putting a sanitised paper band on the toilet seat, and neatly shaping the end piece of the toilet tissue into a fresh-looking arrowhead. Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985, 1988) have also indi-cated that employees who have neat appearances will be visually appealing at an excellent company. All these actions are better than words at conveying the idea of service tangibi-lisation to customers. Besides, as well as Nguyen and Leblanc’s (2002) argument, the functional component is related to tangible characteristics, which can be easily measured by customers. Therefore, the facility-oriented contact presents service in a tangible way by focusing on the physical aspects of a service from which the customers will receive per-formance benefits. Consequently, this study infers that facility-oriented contact creates an identity for customers and it can serve as a contact realm to establish a brand of a service. An Atmosphere-Oriented Contact is when the ‘physical environment creates an emotional response, which in turn elicits approach or avoidance behaviour in regards to the physical environment’ (Countryman & Jang, 2006, p. 535). In their article, the authors found that three atmospheric elements, colour, lighting, and style, were signifi-cantly related to the overall impression of a hotel lobby. This observation indicates that the surroundings of the specific environment helps customers form their attitude and behaviour (Bitner, 1992; Shostack, 1977). When customers try to evaluate a service prior to using or purchasing it, they will ‘understand’ the service via peripheral clues/ evidence derived from the tangible objects (Shostack, 1977). Thus, Berry (1980) suggests that marketers require a connection to intangible service components and tangible symbols in order to convey proper meaning to customers. The above discussions

Figure 1. The four realms of brand contact.

suggest that service providers effectively utilise the servicescape to strengthen the uniqueness of a service, as this will allow customers to more clearly recognise the service as valuable. All these endeavours are supposed to create an emotional experience for customers. To some extent, atmospheric cues or clues are more important in the purchasing decision of services than for physical goods (Brady & Bourdeau, 2005). In general, consumption within a physical environment is not of an object but an idea, it is a type of behaviour possessing of social meaning (Hou, 2005). Therefore, an atmosphere-oriented contact presents service in a tangible way by focusing on the atmospheric aspects of a service from which the customers will receive emotion benefits.

Consequently, this study infers that atmosphere-oriented contacts engender a feeling for customers, and they can serve as a contact realm in establishing the brand of a service. A Service-Oriented Contact refers to a ‘service encounter that serves as a sign of quality and value to customers’ (Hartline & Jones, 1996, p. 207). Taking hotels as an example, the findings indicate that the performance of front desk, housekeeping, and parking personnel significantly affect perceived quality, whereas the performance of front desk and room service personnel significantly affect perceived value. Hence, encoun-ter performance can be seen as ‘the job of managers and support staff to support and help front-line staff in their mission to please the end user, the customer’ (Frost & Kumar, 2000, p. 359). It means that customer/employee interaction is very critical to the success of the service experience (Devlin & Dong, 1994; Fortini-Campbell, 2003). As proposed by Clark, Rajaratnam, and Smith (1996), some services (e.g. consultancy) create comparative strength by means of the on-the-spot interaction, i.e. service encounters increase the cus-tomers’ sense of service (Bitner, Booms, & Tetreaukt, 1990). A good example would be ‘a hotel that could claim a factual procedure, such as how its check-in procedure entails no check-in lines, as the bell captain already has your room key ready as soon as you arrive’ (Mittal & Baker, 2002, p. 61). Therefore, the service-oriented contact presents service in an intangible way by focusing on the interactive aspects of a service in which the customers will receive the performance benefits. Consequently, this study infers that the service-oriented contact makes customers see through and understand the service process, and it can serve as a contact realm to establish a brand of a service.

An Image-Oriented Contact refers to the images, including cognitive and affective images, that are the sum of the benefits, ideas, and impressions that people have of a store, place or destination. According to Russell and Snodgrass (1987, p. 246), they concern ‘a customer’s behaviour that may be influenced by the (estimated, perceived, or remembered) affective quality of an environment rather by its objective properties directly’ (Baloglu & Brinberg, 1997). That is, since a customer’s image is derived from the brand associations/elements held in their memory that form the basis of a brand image/identity (Keller, 1993), the brand associations/elements toward affective objects play an important role in how a brand image is conceptualised, such as heritage and history of a city (Hankinson, 2005). For example, in the field of leisure tourism marketing, studies focus on discussing the destination image of tourists proposed that, to some extent, some specific factors such as the residents and culture of a destination in terms of affective image are important factors in motivating tourists to visit (Baloglu & Brinberg, 1997; Echtner & Ritchie, 1993; Hankinson, 2005). Therefore, image-oriented contacts present a service in an intangible way by focusing on the transformational aspects of a service from which the customers will receive emotion benefits. Consequently, this study infers that the image-oriented contact makes customers create an affective image associated with the service offerings which would guide their purchasing decision and serve as a contact realm to establish the brand of a service.

Proposed integrated approach in exploring brand contact elements

In response to the first managerial issue, Kano, Seraku, Takahashi, and Tsuji (1984) have developed a two dimensional model of quality to categorise the attributes of a product or service based on how well they are able to satisfy customer needs in terms of a customer’s perception and experience (Kuo, 2004; Tan & Pawitra, 2001). Subsequent scholars have applied the model to various fields such as product development projects (Matzler & Hinterhuber, 1998), Web-community service quality (Kuo, 2004), and supply chain per-formance (Zokaei & Hines, 2007). Yang (2005, p. 1128 – 1129) has summarised the five categories of the Kano model as follows: (1) Attractive quality attribute: an attribute that gives satisfaction if present, but no dissatisfaction if absent; (2) One-dimensional quality attribute: an attribute that is positively and linearly related to customer satisfaction, that is, the greater the degree of fulfillment of the attribute, the greater the degree of cus-tomer satisfaction; (3) Must-be quality attribute: an attribute whose absence will result in customer dissatisfaction, but whose presence does not significantly contribute to customer satisfaction; (4) Indifferent quality attribute: an attribute whose presence or absence does not cause any satisfaction or dissatisfaction to customers; and (5) Reverse quality attribute: an attribute whose presence causes customer dissatisfaction, and whose absence results in customer satisfaction.

Based on publications of the Kano model, Tan and Pawitra (2001) pointed out that although several significant benefits are recognised, such as those attributes that have the greatest influence on customer satisfaction (Matzler & Hinterhuber, 1998), several limitations exist in the model, such as the classification of the attributes not being quanti-fied or numerated (Bharadwaj & Menon, 1997), which means the priority assigned to cus-tomer needs cannot actually be considered. Marketers should find the most important parts in order to improve in terms of resource allocation (Shen et al., 2000). The QFD analysis, first introduced by Akao in 1966, provides a means of translating customer requirements into appropriate technical requirements. In order to quickly raise customer satisfaction, the most important requirements would be prioritised for improvement and then later the less important requirements would be improved, in turn, for the sake of effectively using resources, i.e. achieving more with less. QFD is a customer-oriented product development technique that links customer expectations to the technical characteristics of the product, in order to ensure market success once the product is released (Sireli et al., 2007). It also could be used with contact elements in order to understand them in terms of customers and firms. Therefore, to achieve this study’s purpose of acquiring brand contact elements, a consideration of the benefits of the Kano model and its integration into QFD can help a firm to prioritise which contact elements of a brand on which it should focus its efforts. Any element is part of the contact points that affect customers’ experience with products and services. Although customers decide what makes up the brand, marketers can save costs and time on elements of secondary importance to customers and instead spend resources on crucial brand contacts. This is how the integration approach applied in this study can be useful.

Examination of brand contact experiences

As for the second managerial issue, this study aims to understand customers’ experiences toward the brand contacts of a firm. Thus, based on the obtained contact elements, the brand contact priority grid provided by Fortini-Campbell (2003) is used to analyse what the marketer should do to bring the real brand into conformity with the aspirational brand. Although the contact elements are classified (including must-be, one-dimensional,

and attractive contact elements) and ranked based on an integrated approach, to determine which contact elements make up customer’s requirements even beyond expectation is necessary, i.e. the more the proper contact elements experienced by customers, the greater the customers’ perception of the brand. In this grid, based on the bi-polar assess-ments of importance and satisfaction, brand contact eleassess-ments obtained from the inte-gration approach are displayed into what customers see as Delighters, Disgusters, Annoyances, and Frills. The four types of brand contacts are those that marketers analyse to discover what to improve the most in order to meet the customer’s require-ments. Marketers should pay particular attention to ‘Delighters’ and ‘Disgusters’ because they are the brand contacts that do the most to shape the brand in the customer’s mind. Furthermore, marketers who want to help their brand the most should first fix the ‘Disgusters’, because those are the important things that customers think are in need of change. However, most marketers might spend too many resources on ‘Frills’, which customers notice and like, but which are not important to them at present. Thus, if the ‘Disgusters’ and ‘Annoyances’ are removed, the marketer should make sure the ‘Delighters’ are increased. It follows that the results of the brand contact priority grid could be used as a reference for service providers, in order to simultaneously consider the importance and suitability of establishing a brand in an effective way.

Examination of brand contact perceptions

Since brand attitude is a customer’s overall evaluation of a brand (Keller, 1993), customers will form a different perception based on the performance of the elements they encounter (Shen et al., 2000). Thus, the third managerial issue in this study focuses on understanding the relationship between the different types of contact elements (facility, atmosphere, service, or image) and customers’ perceptions toward the hot spring hotel, i.e. the custo-mers’ senses of risk and uncertainty (Tarn, 2005) are examined. Consequently, this study proposes to clarify the aforementioned assumption in the final stage of the brand contact examination, and to accordingly list the research framework as Figure 2.

Research methodology

The research process described in the following includes the acquisition of contact elements, Kano model analysis, QFD analysis, brand contact priority grid analysis and the examination of the customer’s perception toward the brand contact.

Acquisition of contact elements of a hot spring hotel – the first managerial issue Taiwan possesses rich and various hot spring resources because of its specific geographic environment. The use of hot springs has changed tremendously, from their initial function as simple bath therapy to their current multiple functions such as recreation, tourism, medical treatment, and newly developed beauty spas. These offerings have made the hot spring potentially the most representative recreation and tourism resource in Taiwan. In addition to domestic tourism, hot springs also attract a number of international tourists.

Based on the previous efforts, it must be noted that this study still has two deficiencies to be solved. First, the arguments about the contact practices of hot spring hotels in the literature are divergent and overlap in content and terminology. Thus, this study needs more integration, to converge toward a categorisation scheme that would be useful in understanding the nature of contact practices, in order to work towards further academic

and practical efforts. Second, most findings, if not all, in the literature do not examine brand contact in an integrated approach in terms of the customers and the firms. This study aims to solve these two shortcomings. Thus, after summarising the related studies, this paper categorises related contact elements into specific contact classifications within the four realms of brand contact as shown in Figure 3 and as explained in the following paragraphs.

A Facility-Oriented Contact concerns the hard issues regarding a hot spring hotel that are encountered by customers. The overall contact areas generally include three parts: (1) hot spring bathing, i.e. the customers’ contacts toward the quality of hot spring water and the use of various hot spring pools which mostly are deemed as the soul of a hot spring hotel. It includes the spa, Jacuzzi and swimming pool; (2) lodging and dining, i.e. the customers’ contacts toward the use of comfortable hotel rooms for accom-modation or relaxation and toward the offer of local agricultural meals for dining; and (3) transportation, i.e. the customers’ contacts toward the convenience of a mass transit system or the presence of sufficient parking spaces. Thus, the facility-oriented contact is a tangible action in which customers receive performance benefits from the encounter.

Figure 3. Brand contact elements of hot spring hotel. Figure 2. Research framework.

An Atmosphere-Oriented Contact addresses the environment created by the hot spring hotel and how it is perceived by customers. Basically, in terms of geography, hot spring hotels are mostly located in the districts possessing hot spring resources such as those in close proximity to a mountainous area or the sea. Thus, due to its unique location, the overall planning of the surroundings of a hot spring hotel is important for customers to assess and influences their motivation to visit. Tourists who visit a hot spring hotel also like to sightsee. There are three kinds of atmospheric fields synthesised from the pre-vious studies. They are: (1) external landscape, i.e. the customers’ contact toward the external related environment, such as the natural scenery around the hot spring hotel, nearby environment planning and safety; (2) internal design, i.e. the customers’ contact toward the interior decoration or design, such as the overall style of the hot spring hotel; and (3) pricing, which means customers have different expectations toward the service quality of a firm based on different pricing schemes (Knuston, Stevens, Patton, & Thompson, 1992). Particularly pricing for customers is usually related to how they perceive the service offering of a business and its value (Klaus & Bernd, 2002) which means pricing is a kind of contact point when customers visit the hot spring hotel. Thus, pricing could be used as an atmospheric perception of how the customers perceive the hot spring hotel as reliable or to identify the employees’ work performance in terms of monetary concern. Therefore, an atmosphere-oriented contact is a tangible action in which customers receive emotional benefits from the encounter.

A Service-Oriented Contact refers to a service that is ‘an act offered by one party to another. Although the process may be tied to a physical product, the performance is transitory, often intangible in nature, and does not normally result in ownership of any of the factors of production’ (Lovelock & Wirtz, 2004, p. 9). The services involved in an encounter between the firm and the customers wherein the services and manage-ment activities are provided to customers by the hot spring hotel. Three service fields have been synthesised from previous studies: (1) managerial effect, i.e. hot spring hotels conduct good management rules in order to offer good services to customers, such as service process management and customer relationship management; (2) staff work, i.e. employees provide good service to customers, such as service attitude and efficiency; and (3) website function, as suggested due to the growing era of digitisation (Ekeledo & Sivakumar, 2004), i.e. whether the information provided by the website, such as location and weather, is clear and easy to navigate. The website functions by transmitting intangible information to customers while the performance benefits are perceived via data processing (Shapiro & Varian, 1999). Thus, the service-oriented contact is an intangible action while customers receive performance benefits from the encounter.

An Image-Oriented Contact refers to the customer’s image association of a firm and how it affects their decision to visit a hot spring hotel. It is the sum of the benefits, ideas, and impressions that customers have of a destination (Gartner, 1986). There are three image associated fields synthesised from the previous studies: (1) health association, i.e. customers who visit the hot spring hotel are influenced by the association of a healthy image, such as enjoying a hot spring bath to improve physical and mental health; (2) travel association, i.e. customers who join the hot spring activities are influenced by the association of a travel image, such as travelling to the hot spring destination for a unique experience; and (3) culture association, i.e. customers who visit the hot spring hotel are influenced by the association of cultural images, such as experiencing the distinct hot spring culture. Thus, image-oriented contact is an intangible action that allows custo-mers to receive emotional benefits from the encounter.

The Kano model analysis for the first managerial issue

At this stage each identified contact element concerning customer requirements will be analysed on the basis of the Kano model. The Kano questionnaire, consisting of pairs of one positive and one negative question, provides a systematic way of grouping customer requirements into different Kano categories. A pair of questions is: ‘how would you feel if the hot spring hotel has the element?’ and ‘how would you feel if the hot spring hotel does not have the element?’ For both questions, customers choose from one of the following responses: ‘delighted’, ‘expect and like it’, ‘no feeling’, ‘live with it’, or ‘do not like it’. Thus, the questionnaire design is based on the previous studies in regards to the four contact fields in terms used in Kano’s two dimensional quality model, as listed in Table 1. In an attempt to confirm the appropriateness of the questionnaire content, before the questionnaire was sent, a pilot test was given to 20 hot spring hotel customers who were familiar with hot spring activities over a long period of time. After that, the questionnaire was modified and finalised for the formal investigation. Based on the procedures provided by Shen et al. (2000), customer contact elements can be categorised as ‘must-be’, ‘one-dimensional’, or ‘attractive’; however, at times, customers may not be able to express their opinion whether a particular contact element feature of a hot spring hotel fulfils their needs. In this case, it may be classified as ‘indifferent’ rather than one of the three main categories. All the outcomes of Kano’s analysis (e.g. respondent rate, reliability and validity analysis) are shown and discussed in the results section.

Use of quality function deployment (QFD) analysis for the first managerial issue Classifying contact elements into their appropriate Kano categories and sub-categories helps us to understand the customer requirements of contact elements. The general

Table 1. Hot spring hotel contact fields and their elements.

Contact realm Contact classification Contact element

Facility-oriented contact Hot spring bathing † various hot spring pools † certified hot spring water Lodging & dining † comfortable hotel room

† local cuisine

Transportation † convenient mass transit system † sufficient parking space Atmosphere-oriented contact External landscape † surrounding natural scenery

† local environment planning Internal design † overall safety

† unique style Pricing † reasonable pricing

† extra charge noticed in advance Service-oriented contact Managerial effect † wait-in-line management

† customer reaction channel Staff work † employee service attitude

† employee service efficiency Website function † clear information on the website

† an easily navigable website

Image-oriented contact Health association † physical and mental health association † emotion exchange association Travel association † amusement association

† recreation and tourism association Culture association † local customs association

† history and culture association

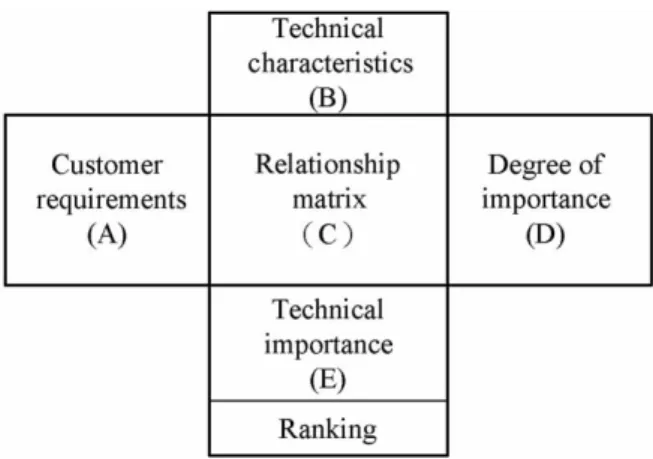

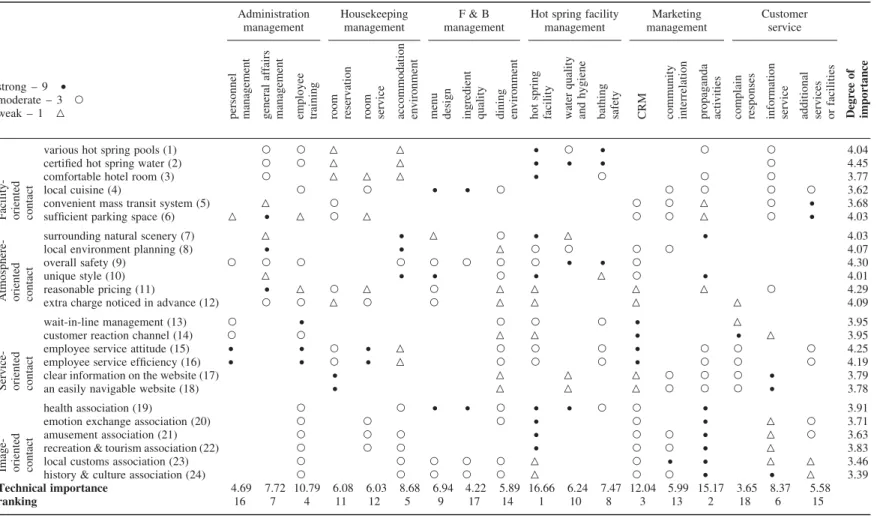

guideline is to seek to ‘fulfil all must-be requirements, be competitive with market leaders in regards to the one-dimensional attributes and to include some differentiating attractive elements’ (CQM, 1993; Shen et al., 2000, p. 95). The QFD analysis is performed based on the thoroughly collected and deeply analysed customer requirements from the previous stage. Specifically, the contact elements analysed using the Kano model are used as input to the QFD analysis. Among the various stages of QFD, the house of quality (HOQ) is the most commonly used stage and its aim is to reflect customer desires and tastes (Raharjo et al., 2007). The HOQ construction begins with the left room, i.e. the col-lection of customer needs and their priorities. It consists of several sub-matrices joined together in various ways, and each contains information related to the others (see Figure 4). Section A of Figure 4 contains a list of customer wants and needs, also called the voice of the customer or ‘whats’. The customer requirements for the contact elements are obtained from the previous stage of the Kano model. Section B covers the technical characteristics of a hot spring hotel, also called the ‘hows’, synthesised from related studies, including administration management (personnel management, general affairs management, and employee training), housekeeping management (room reservation, room service, and accommodation environment), food and beverage management (menu design, ingredient quality, and dining environment), hot spring facility manage-ment (hot spring facility with landscape planning, water quality and hygiene, and bathing safety management), marketing management (customer relationship management, community interrelation, and propaganda activities), and customer service (customer com-plaint responses, information service, and requests for additional services/facilities). Section C is the part of the relationship matrix which indicates how much each ‘how’ affects each ‘what’. The relationship is defined as strong (9 points), moderate (3 points), and weak (1 point). Section D is the degree of importance to which each subject is asked to rate the importance (1 to 5 scale) in a Kano questionnaire. Section E addresses the technical importance which is achieved to multiply each contact element’s relationship key by the degree of importance. The final score is the ranking of each contact element for customer requirements. In conclusion, the ranking of contact elements provides hot spring hoteliers a guide for making trade-offs in resource allocation. In other words, according to the QFD, a hot spring hotel could first make efforts to improve top-ranking technical characteristics in accordance with customer needs and then to improve the secondary items.

Figure 4. A house of quality.

The brand contact priority grid analysis – the second managerial issue

Although the ranking from QFD reveals that the top-ranked technical characteristics related to some specific contact elements should be considered, it is necessary to under-stand the extent of customer experience with the current contact elements. This is to find the important things that customers think are broken and should be fixed first. Thus, subsequent to the QFD analysis, based on the bi-polar evaluations of importance and satisfaction, the Brand Contact Priority Grid is used to answer two questions which are how important and how good is each current contact element to a hot spring hotel customer. Therefore, along with the degree of importance to which each subject is asked to rate the importance (1 to 5 scale), satisfaction (1 to 5 scale) is also asked in a Kano questionnaire. The results could provide information on how to prioritise the elements within quadrants (i.e. Delighters, Disgusters, Annoyances, and Frills), and, for example, on how to fix the worst disgusters before the lesser issues.

The examination of customer’s perception – the third managerial issue

Finally, another managerial issue to consider is to understand the relationship between the customer’s experience and attitude toward the hot spring hotel. Thus, subjects are asked to respond to another four questions in a Kano questionnaire designed to confirm that a customer is satisfied with the important contact elements and if they will demonstrate their positive attitude toward the hot spring hotel. The customer’s perception toward a service draws on past research (i.e. Tarn, 2005) on the dimension of ‘sense of service risk and uncertainty’. The scale includes four items which are established with operatio-nalisation assessed on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ¼ strongly disagree to 5 ¼ strongly agree. The four items are ‘This hot spring hotel makes me feel very trust-worthy’, ‘I believe this hot spring hotel is a great hotel’, ‘If I need to recommend a hot spring hotel to others, I will consider this hot spring hotel as a possible destination’, and ‘After visiting this hot spring hotel, I would consider visiting here again’.

Research samples and data collection

This study explores the contact elements of a hot spring hotel and also tries to understand the customer’s experience with a hot spring hotel’s brand contacts. Therefore, in this study, a hot spring hotel located in Wu-Lai hot spring district (one of the most famous hot spring districts in Taipei area) was selected. This hot spring hotel is a typical hot spring hotel with 80 employees and has operated for over 30 years. It features public and private hot spring pools, rooms for accommodation, and dining areas. Respondents are tourists who have visited the selected hot spring hotel and were asked to participate in the study before they left for home. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed to the subjects for a convenient sampling that lasted for one week (Monday through to Sunday, 10 am to 6 pm).

Results

Over a period of one week, data obtained from 33 respondents was discarded because of incomplete or inappropriate responses to various questionnaire items. Statistical analyses of the collected questionnaires were computed based on the 267 effective responses regarding the hot spring hotel. The statistical software of SPSS 10.0 was used to conduct the following examinations as described below.

Demographic profile

Of these 267 questionnaires, 44% of the responses were by male respondents, while 56% were by females. Regarding the age distribution of the respondents, those between 35 and 49 accounted for 74%, while those over the age of 65 accounted for 22%. These data indi-cate that the elderly should not be ignored in the market of hot spring related activities. Regarding the occupational distribution of the respondents, the majority (48%) were public servants, teachers and service workers. Regarding the geographical distribution of the respondents, those from the north of Taiwan accounted for 79%, followed by the middle areas. Relatively fewer respondents live in the southern and eastern areas, indicat-ing that hot sprindicat-ing destinations usually attract tourists from the nearby areas, an obser-vation consistent with the findings of other studies. Finally, the majority (58%) had at least a university degree (bachelor or equivalent) with an income under $1500 per month. Furthermore, with respect to the travelling features of customers, hot spring bathing (90%) was the most popular, followed by the accommodation (26%), and dining (20%), indicating that the hot spring resource functioned as the main entertainment activity of hot spring hotel, much unlike standard hotels. Additionally, respondents acquired infor-mation about this hot spring hotel mostly from their relatives and friends (60%), followed by the internet, newspaper, and magazines (32%), indicating that word-of-mouth might be one of the important marketing channels for hot spring hoteliers. Finally, people who join hot spring activities are not alone (93%), indicating that hot spring activities are suitable for families or friends to engage in together.

Reliability analysis

The empirical evidence from the internal consistency analysis has shown that Cronbach’s alpha values of the four parts in the questionnaire (Kano’s functional form of the question, Kano’s dysfunctional form of the question, overall importance of the question, and overall satisfaction of the question) range from 0.72 to 0.92, and are therefore not lower than 0.60 (Nunnally, 1978). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha value of the overall questionnaire is 0.92, which matches the basic requirement for internal consistency (Wortzel, 1979).

Validity analysis

This study used Kano model to measure the contact elements of a hot spring hotel and the designed questionnaire included 24 items. The completeness of the measurement was ensured by beginning with the statistically significant results of the Bartlett test. General-ised Least Square was conducted in order to force each construct being extracted to have the number of factors set to one. In addition, Direct Oblimin Rotation was used to obtain the bearing value for the ease of explanation (Reise, Waller, & Comrey, 2000). Finally, the factor loadings of functional form of the question range from 0.41 to 0.56; the factor load-ings of dysfunctional form of the question range from 0.64 to 0.88; the importance of the question ranges from 0.38 to 0.68; and the satisfaction question ranges from 0.39 to 0.73. In summary, the factor loadings of each construct are over 0.3, which performing accep-table validity of the returned data (Nunnally, 1978).

The results of the Kano model analysis for the first managerial issue

The classification of contact elements utilised the method of the Kano evaluation table, proposed by Matzler and Hinterhuber (1998). In this method the contact elements, in terms of Kano’s two dimensional model, can be categorised into five quality attributes

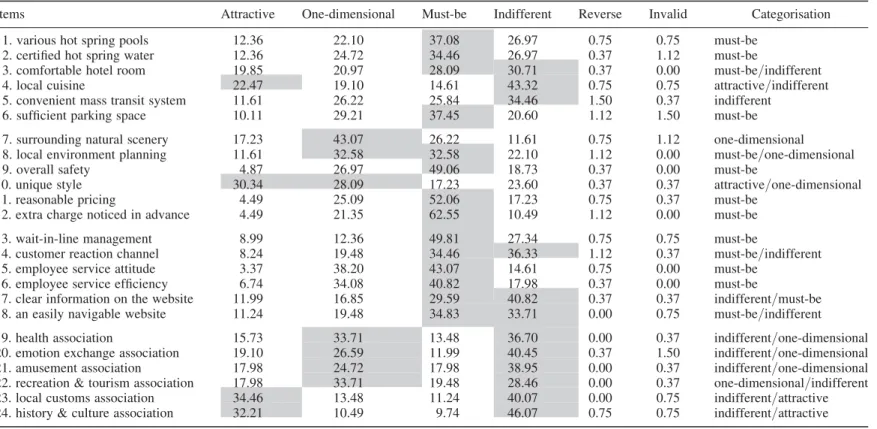

which are: attractive quality, one-dimensional quality, must-be quality, indifferent quality, and reserve quality. Finally, the contact elements were classified as based on the contrib-uted percentage of the quality attributes (as shown in Table 2) and described as following. Attractive quality. In this category, the presence of a service element results in customer satisfaction. The deficiency however does not result in dissatisfaction because the custo-mer usually does not have any experience of the service element. The elements falling in this category correspond with the motivator factors proposed in the theory of Herzberg, Mausner and Snyderman (1959). Finally, local cuisine (22.47%), unique style (30.34%), and the associations with local customs (34.46%), and history and culture (32.32%) are included.

One-dimensional quality. Customers are satisfied if the element is affordable. Further-more, the higher the quality level, the higher the degree of satisfaction and vice versa. The service element is positively and linearly correlated to customer satisfaction. Finally, the surrounding natural scenery (43.07%), local environment planning (32.58%), unique style (28.09%) and the associations with physical and mental health (33.71%), emotion exchange (26.59%), amusement (24.72%), and recreation and tourism (33.71%) are included.

Must-be quality. The element in this category has to be provided to customers, and its presence does not have a significantly positive impact on customer satisfaction. However, its absence causes customer dissatisfaction. Various hot spring pools (37.08%), certified hot spring water (34.46%), comfortable hotel room (28.09%), sufficient parking space (37.45%), local environment planning (32.58%), overall safety (49.06%), reasonable pricing (52.06%), extra charge noticed in advance (62.55%), wait-in-line management (49.81%), customer reaction channels (34.46%), employee service attitude (43.07%), employee service efficiency (40.82%), clear information on the website (29.59%), and an easily navigable website (34.83%) are included.

Indifferent quality. This element does not result in satisfaction or dissatisfaction and reflects no bearing about affordability. A comfortable hotel room (30.71%), local cuisine (43.32%), a convenient mass transit system (34.46%), customer reaction channels (36.33%), clear information on the website (40.82%), an easily navigable website (33.71%), and associations with physical and mental health (36.70%), emotion exchange (40.45%), amusement (38.95%), recreation and tourism (28.46%), local customs (40.07%), and history and culture (46.07%) are included.

Reserve quality. Unlike a one-dimension element, the absence of this element brings about customer satisfaction, and its presence does not. As well as the invalid categoris-ation, no element was categorised as having this quality.

In summary, this study adopts the two dimensional categorisation provided by Matzler and Hinterhuber (1998) in which the contact elements with the highest percentages are categorised into a certain category. According to the Chi-square test, the difference between each group is significant, meaning that the respondent’s opinions toward the contact elements can be distinguished based on the results of the percentage allocation. However, since customers might have different opinions about each contact element, the problem of ‘discrepancy’ regarding the elements’ classification usually occurs among customers. To solve the discrepancy issue, the method used to categorise the elements can be based on ‘a significant number of respondents’, which is the principle to determine the element belonging to certain quality attribute in terms of the opinions

Table 2. The percentage and categorisation of contact elements by the Kano model.

Items Attractive One-dimensional Must-be Indifferent Reverse Invalid Categorisation

1. various hot spring pools 12.36 22.10 37.08 26.97 0.75 0.75 must-be

2. certified hot spring water 12.36 24.72 34.46 26.97 0.37 1.12 must-be

3. comfortable hotel room 19.85 20.97 28.09 30.71 0.37 0.00 must-be/indifferent

4. local cuisine 22.47 19.10 14.61 43.32 0.75 0.75 attractive/indifferent

5. convenient mass transit system 11.61 26.22 25.84 34.46 1.50 0.37 indifferent

6. sufficient parking space 10.11 29.21 37.45 20.60 1.12 1.50 must-be

7. surrounding natural scenery 17.23 43.07 26.22 11.61 0.75 1.12 one-dimensional

8. local environment planning 11.61 32.58 32.58 22.10 1.12 0.00 must-be/one-dimensional

9. overall safety 4.87 26.97 49.06 18.73 0.37 0.00 must-be

10. unique style 30.34 28.09 17.23 23.60 0.37 0.37 attractive/one-dimensional

11. reasonable pricing 4.49 25.09 52.06 17.23 0.75 0.37 must-be

12. extra charge noticed in advance 4.49 21.35 62.55 10.49 1.12 0.00 must-be

13. wait-in-line management 8.99 12.36 49.81 27.34 0.75 0.75 must-be

14. customer reaction channel 8.24 19.48 34.46 36.33 1.12 0.37 must-be/indifferent

15. employee service attitude 3.37 38.20 43.07 14.61 0.75 0.00 must-be

16. employee service efficiency 6.74 34.08 40.82 17.98 0.37 0.00 must-be

17. clear information on the website 11.99 16.85 29.59 40.82 0.37 0.37 indifferent/must-be

18. an easily navigable website 11.24 19.48 34.83 33.71 0.00 0.75 must-be/indifferent

19. health association 15.73 33.71 13.48 36.70 0.00 0.37 indifferent/one-dimensional

20. emotion exchange association 19.10 26.59 11.99 40.45 0.37 1.50 indifferent/one-dimensional

21. amusement association 17.98 24.72 17.98 38.95 0.00 0.37 indifferent/one-dimensional

22. recreation & tourism association 17.98 33.71 19.48 28.46 0.00 0.37 one-dimensional/indifferent

23. local customs association 34.46 13.48 11.24 40.07 0.00 0.75 indifferent/attractive

24. history & culture association 32.21 10.49 9.74 46.07 0.75 0.75 indifferent/attractive

K.-C. Chang and M .-C. Chen

of relative plurality. According to the results, although some contact elements are diver-gent among customers, the classifications with a slight difference related to the percentage should be a concern to service providers in terms of making a managerial decision (Yang, 2005). These contact elements of this challenging type include a comfortable hotel room, local cuisine, local environment planning, unique style, customer reaction channels, clear information on the website, an easily navigable website, and associations with physical and mental health, emotional exchange, amusement, recreation and tourism, local customs, and history and culture. Therefore, these contact elements are simultaneously classified into two categories based on their first priority, and the second ranking is considered if they perform slight difference on percentage, but present bigger differences than the other categories. The rational is that although the top one contact element occupies the highest percentage among the quality attributes, the second contact element cannot be ignored if it presents managerial consideration. For example, a comfor-table hotel room should be categorised as an indifferent quality (30.71%), while the must-be quality is quantified as 28.09%. The ‘indifferent’ and ‘must-must-be’ percentages are not very different but the ‘must-be’ percentage is much higher than the others, e.g. attractive (19.85%), one-dimensional (20.97%), reserve (0.37%), and invalid (0%). Thus, for hot spring hoteliers, comfortable hotel rooms are recognised as indifferent since most custo-mers merely come to take hot spring bathing activities without accommodation; however, the voice of the tourists who come to stay at the hot spring hotel should also be considered. This example demonstrates why double checking the second quality attribute might deliver some important managerial messages, as shown in Table 2.

The results of QFD analysis for the first managerial issue

Following the classification of customer requirements into their appropriate Kano cat-egories, QFD is utilised through the voice of customers to drive the serial activities of a firm, in order to aggressively pursue customers’ delight instead of dealing with the custo-mer complaints (Akao, 1990). Thus, the function of QFD is to break all of the custocusto-mers’ expectations into more concrete and specific needs wherein the customers’ needs must actually and exactly be transferred as the firm’s required information. In order to employ the QFD technique, the correlated analysis between Technical Characteristics and Customer Requirements lists the Relationship Matrix, in which the correlation between the design requirement (i.e. hows) and the voice of customers (i.e. wants) were observed. Consequently, through the interviews with experts (three hot spring hoteliers), the cor-relation between the ‘hows’ (listed in rows) and ‘wants’ (listed in columns) were explored to determine which merited the strongest relationship (given 9 points and marked as †), the second strongest relationship (given 3 points and marked as W), and the least strong relationship (given 1 point and marked as△). Finally, through the process of cross analy-sis of the two axes, the Relationship Matrix was obtained as shown in Table 3.

Along with the process of calculating the correlation matrix, the degree of importance of each contact element, as derived from the respondents, is also considered. In other words, the final ranked score of each contact element is achieved by multiplying each contact element by the degree of importance and then divided by the total number of elements. The ranking of contact elements would finally provide hot spring hoteliers with a guide for making trade-offs in resource allocation (Shen et al., 2000). For example, as for the relationship between ingredient quality and local cuisine, the total score is calculated as (9× 3.62 + 3 × 4.30 + 9 × 3.91 + 3 × 3.46 + 3 × 3.39)/24 ¼ 4.22. Other elements are also calculated by following this method. Consequently, in order to understand which

Table 3. A house of quality for a hot spring hotel. strong – 9 † moderate – 3 W weak – 1 △ Administration management Housekeeping management F & B management

Hot spring facility management Marketing management Customer service Degree o f importan ce

personnel management general

affairs

management employee training room reservation room service accommodation environment menu design ingredient quality dining environment hot

spring

facility water

quality

and

hygiene

bathing safety CRM community interrelation propaganda activities complain responses information service additional services or

facilities

Facility- oriented contact

various hot spring pools (1) W W △ △ † W † W W 4.04

certified hot spring water (2) W W △ △ † † † W 4.45

comfortable hotel room (3) W △ △ △ † W W W 3.77

local cuisine (4) W W † † W W W W W 3.62

convenient mass transit system (5) △ W W W △ W † 3.68

sufficient parking space (6) △ † △ W △ W W △ W † 4.03

Atm

osphere-oriented co

ntact

surrounding natural scenery (7) △ † △ W † △ † 4.03

local environment planning (8) † † △ W W W W 4.07

overall safety (9) W W W W W W W W † † W 4.30

unique style (10) △ † † W † △ W † 4.01

reasonable pricing (11) † △ W △ W △ △ △ △ W 4.29

extra charge noticed in advance (12) W W △ W W △ △ △ △ 4.09

Service- oriented contact

wait-in-line management (13) W † W W W † △ 3.95

customer reaction channel (14) W W △ △ † † △ 3.95

employee service attitude (15) † † W † △ W W W † W W W 4.25

employee service efficiency (16) † † W † △ W W W † W W W 4.19

clear information on the website (17) † △ △ △ W W W † 3.79

an easily navigable website (18) † △ △ △ W W W † 3.78

Image- oriented contact

health association (19) W W † † W † † W W † 3.91

emotion exchange association (20) W W W † W † △ W 3.71

amusement association (21) W W W † W W † △ W 3.63

recreation & tourism association (22) W W W † W W † △ 3.83

local customs association (23) W W W W W △ W † † △ △ 3.46

history & culture association (24) W W W W W △ W W † † △ 3.39

Technical importance 4.69 7.72 10.79 6.08 6.03 8.68 6.94 4.22 5.89 16.66 6.24 7.47 12.04 5.99 15.17 3.65 8.37 5.58 ranking 16 7 4 11 12 5 9 17 14 1 10 8 3 13 2 18 6 15 K.-C. Chang and M .-C. Chen

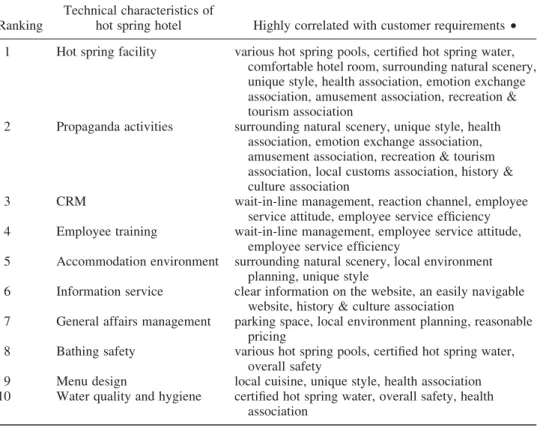

contact elements needed to be improved first, two prerequisites are defined in this study: (1) the top ten services that need urgent improvement by service providers; and (2) those of these service offerings that are highly correlated to the contact elements (i.e. the cell marked as highly correlated †). The consideration is that once the top ten service offerings are taken into account, the major contact elements are improved as well. According to Table 3, the items in accordance with the assumed prerequisites were obtained as listed in Table 4. This table shows that QFD can effectively understand the relationship between customers and service providers. Combining the results both from operators and customers’ perception toward the hot spring hotel, this study provides references for hoteliers to make future improvements, and are expected to help publicise hot spring activities.

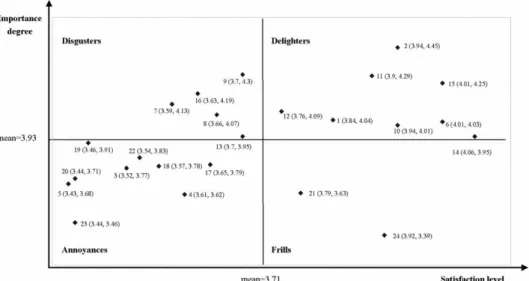

The results of brand contact priority grid analysis for the second managerial issue This study aims to understand customer brand contact experiences and customers’ percep-tions of the hot spring hotel. According to Fortini-Campbell (2003), based on the evalu-ation of the degree of importance (Y-axis) and the evaluevalu-ation of the level of satisfaction (X-axis), the brand contact priority grid (Figure 5) clearly reveals what customers need, with an emphasis on the contact elements as described below.

Delighters. In this category, the elements are those that customers consider to be impor-tant, and for which the performance is satisfactory. The hot spring hotelier has to maintain the same services to keep the customers’ satisfaction for the elements located in this area. Various hot spring pools (must-be), certified hot spring water (must-be), sufficient parking

Table 4. The correlation between technical characteristics and customer requirements.

Ranking

Technical characteristics of

hot spring hotel Highly correlated with customer requirements †

1 Hot spring facility various hot spring pools, certified hot spring water, comfortable hotel room, surrounding natural scenery, unique style, health association, emotion exchange association, amusement association, recreation & tourism association

2 Propaganda activities surrounding natural scenery, unique style, health association, emotion exchange association, amusement association, recreation & tourism association, local customs association, history & culture association

3 CRM wait-in-line management, reaction channel, employee service attitude, employee service efficiency 4 Employee training wait-in-line management, employee service attitude,

employee service efficiency

5 Accommodation environment surrounding natural scenery, local environment planning, unique style

6 Information service clear information on the website, an easily navigable website, history & culture association

7 General affairs management parking space, local environment planning, reasonable pricing

8 Bathing safety various hot spring pools, certified hot spring water, overall safety

9 Menu design local cuisine, unique style, health association 10 Water quality and hygiene certified hot spring water, overall safety, health

association

spaces (must-be), unique style (attractive/one-dimensional), reasonable pricing (must-be), extra charge noticed in advance (must-be), customer reaction channels (must-be/indiffer-ent), and employee service attitude (must-be) are included.

Frills. The elements listed in this area are not very important to customers, but the per-ceptions of the customers are quite satisfactory. The hot spring hotelier has to be reduced when company resources are limited for the elements located in this area. Associations with amusement (indifferent/one-dimensional) and history and culture (indifferent/attrac-tive) are included herein.

Disgusters. The elements listed here are those considered important to customers but for which the performance has not met with expectations. The elements located in this area are seriously considered and improved upon when the hot spring hotelier attempts to satisfy their customers. The surrounding natural scenery (one-dimensional), local environment planning (must-be/one-dimensional), overall safety (must-be), wait-in-line management (must-be), and employee service efficiency (must-be) are included.

Annoyances. In this category, the listed elements are those about which customers have a lower satisfaction level, but which they also rank as being less important. Thus, a comfor-table hotel room (must-be/indifferent), local cuisine (attractive/indifferent), a convenient mass transit system (indifferent), clear information on the website (indifferent/must-be), an easily navigable website (must-be /indifferent), and associations with physical and mental health (indifferent/one-dimensional), emotion exchange (indifferent/one-dimensional), recreation and tourism (one-dimensional/indifferent), and local customs (indifferent/ attractive) are included.

The results of customer’s perception analysis for the third managerial issue

Finally, as mentioned earlier, this study infers that a customer’s contact toward the facility, atmosphere, service, and image-oriented elements will be significant negatively related to their sense of risk and uncertainty of the service offerings, i.e. the higher the customer’s

Figure 5. The display of brand contact priority grid.

perception toward the contact elements is, the lower the risk and uncertainty sensed by customers. Therefore, multiple regressions were conducted to examine the research question. The analysis of variance is significant, indicating that the predicted variables affect the dependent variables at the 1% significance level (F ¼ 23.97). As for the issue of colinearity, all of the values of CI are under 30, indicating that there is no significant colinearity problem (Belsley, Kuh, & Welsch, 1980). The results suggest that four independent variables explain about 30.2% of the variance of the dependent variable. Furthermore, the b values of the four independent variables are 0.68 (p . 0.10) for the facility-oriented elements, 0.28 (p , 0.01) for the atmosphere-oriented elements, 0.002 (p . 0.10) for the service-oriented elements, and 0.87 (p . 0.10) for the image-oriented elements. Thus, only the atmosphere-oriented contact elements support the assumed relationship in this study.

Summary Discussion

The present study used the Kano model to analyse the desired contact elements from customers, and QFD was employed to take the identified elements into design with the compromise of a service provider’s technical considerations. Accordingly, this study also reports the development of a measurement scale for hot spring hotels based on the four contact realms (i.e. facility, atmosphere, service, and image oriented contacts), synthesised from related literature reviews. The results could also be useful to other hospitality businesses for strategic or tactical purposes.

With regard to the categorisation by Kano’s two dimensional model, the results found that four elements were classified as an attractive quality, seven elements were classified as a one-dimensional quality, 14 elements were classified as a must-be quality, and 12 elements were classified as an indifference quality. Obviously, contact elements were classified as both one-dimensional and must-be qualities, which mostly has been provided in the existing hot spring hotel. Additionally, these elements are viewed as ‘basis features’; that is, when they are absent they will cause customer dissatisfaction (Kano et al., 1984). Furthermore, it should be noted that some of the contact elements belong to a certain category while also demonstrating an importance in another category as the second position, causing the following considerations. First, since customers have different reasons for patronising a hot spring hotel, the hotelier should take care of most of customers’ needs, as necessary. For instance, compared with people who stay at the hotel, customers who engage in one-day hot spring bathing related activities would not pay as much attention to accommodation related issues, such as comfortable hotel rooms, a quality in the facility-oriented contact realm. Second, in addition to the facility-oriented contact, the service-oriented contact reflects a similar phenomena. For example, although customer reaction channels, clear information on the website, and an easily navigable website have been classified as indifferent quality attributes, customers who use the Internet to find information should not be ignored, especially in this cyber-space era (Choi, Stahl, & Whinston, 1997; Peppard & Rylander, 2005). Third, as for the atmosphere-oriented contact realm, none of elements belong to the indifferent categorisation which means that customers have gotten accustomed to viewing this kind of contact as an important consideration in making their consumption decisions (Heide, Lardal, & Grønhaug, 2007). Fourth, the most interesting issue is that, except for the associations with recreation and tourism which are classified as one-dimensional qualities, most of the image-oriented contact elements are categorised as indifferent qualities by