英語外語課程中,部落格融入『過程寫作』之教學: 個案研究 - 政大學術集成

151

0

0

全文

(2) The Integration of Weblogs into the Instruction of Process Writing in an EFL Classroom: A Case Study . 政 治 大 Presented to. A Master Thesis . 立. Department of English,. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 National Chengchi University. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Hui-ling Chan July, 2010.

(3) Acknowledgments Millions of thanks cannot express my gratitude for Dr. Chi-yee Lin. Without his unconditional support and enlightening guidance, this thesis couldn’t be completed. Through his patient instruction and insightful inspirations, I improved my writing skills a lot and developed the capacity for conducting a study. For me, he is not only a. 政 治 大 of life is worth modeling. My appreciation also goes to the committee 立 knowledgeable advisor but also a respectable elder whose philosophy. members, Dr. Ming-chung Yu and Dr. Chia-yi Lee, who offered. ‧ 國. 學. valuable suggestions for revising my thesis.. ‧. Besides, I would like to thank my students who volunteered to be. sit. y. Nat. the four participants in this study. Their earnest attitude toward. io. er. English learning supported me to complete my study. Hopefully they will keep their learning enthusiasm all their life.. al. n. v i n Finally, I would likeCtohgive my warmest thanks to my family. My engchi U. parents gave me their moral support and forgave me for my frequent. absence of family gatherings while my husband and my two naughty sons tolerated my impatience in the process of writing my thesis.. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgments...................................................................................................iii Table of Contents....................................................................................................iv List of Tables .......................................................................................................viii Chinese Abstract.....................................................................................................ix English Abstract.....................................................................................................xi Chapter 1.. 政 治 大 Introduction................................................................................................1 立. 1.1 Background & Motivation....................................................................1. ‧ 國. 學. 1.2 Purpose of the Study.............................................................................6. sit. y. Nat. Chapter. ‧. 1.3 Significance of the Study......................................................................6. io. er. 2. Literature Review.......................................................................................8 2.1 Process Writing...................................................................................8. al. n. v i n 2.1.1 ProcessC Writing Model............................................................8 hengchi U. 2. 2 Previous Studies on Process Writing.................................................9 2.2.1 Studies in L1 Context..............................................................9 2.2.2 Studies in L2 Context............................................................10 2.2.3 Studies in EFL Context..........................................................11 2.3 Previous Studies on Writing through Weblogs.................................12 2.3.1 Weblogs in Education............................................................12 2.3.2 Previous Studies on Writing through Blog............................13 2.4 Common Elements ..........................................................................15 2.4.1 Feedback (Peer Review and Teacher’s Feedback)…...…….15 iv.

(5) 2.4.1.1 Peer Review........................................................15 2.4.1.2 Teacher’s Feedback............................................18 2.4.1.3 Computer-mediated Peer Review (CMPR) .......19 2.4.2 Self-reflection Journal...........................................................21 2.4.3 E-portfolio.............................................................................21 2.5 Research Questions..........................................................................23 Chapter 3. Methodology............................................................................................25. 政 治 大 3.2 Instruments.......................................................................................26 立. 3.1 Participants........................................ ..............................................25. 3.2.1 Drafts on Topics 1 and 5........................................................26. ‧ 國. 學. 3.2.2 Questionnaires on Students’ Writing Attitude.......................27 3.2.3 The Class Blog......................................................................27. ‧. 3.2.4 Students’ Self-reflection Journals..........................................28. y. Nat. sit. 3.2.5 The Teacher’s Logs...............................................................29. n. al. er. io. 3.2.6 Students’ Portfolios...............................................................29. i n U. v. 3.2.7 Self-evaluation Form on Portfolio and Questionnaire on the. Ch. engchi. Writing Class............................................................................30 3.2.8 CEEC Scoring Criteria..........................................................30 3.2.9 Yagelski’s Coding Schemes for Revision Analysis…….......30 3.2.10 Johnson’s Indicators of Content and Organization………..31 3.2.11 Semi-structured Paired Interviews………………..………32 3.3 Procedures........................................................................................32 3.3.1 Writing Cycles.......................................................................33 3.3.2 Timetable of Teaching Activities and Data Collection….….36 3.4 Data Analysis....................................................................................37 v.

(6) Chapter 4. Results......................................................................................................40 4.1 Research Question One………........................................................40 4. 2. Research Question Two..................................................................51 Connie’s Case.................................................................................53 Tina’s Case.....................................................................................57 Ice’s Case.......................................................................................61 Sherry’s Case..................................................................................64. 政 治 大 4.4. Research Question Four...................................................................71 立 4.3 Research Question Three..................................................................69. 4.5 Research Question Five....................................................................74. ‧ 國. 學. 4.6 Research Question Six…...................................................................78. ‧. 4.6.1 The Comparison of Usefulness among Peer Editing Sheets,. sit. y. Nat. Checklists and Journals..................................................................78. io. er. 4.6.2 Commenting Function of the Blog........................................79 4.6.3 Attitude toward Errors...........................................................80. al. n. v i n C hof Blog-mediatedUWriting Class – Workshop 4.6.4 The Nature engchi. Format............................................................................................81 4.6.5 The Learner Types.................................................................83 4.6.6 The Writing Process..............................................................85 Chapter 5. Discussion................................................................................................87 5. 1 Summary of the Findings and Discussion.......................................87 5.1.1 Research Question One…………………………………….87 5.1.2 Research Question Two…………………………………….89 5.1.3 Research Question Three…………………………………..90 vi.

(7) 5.1.4 Research Question Four…………………………...……….91 5.1.5 Research Question Five…………………………………….92 5.1.6 Research Question Six….......................................................92 5.2 Pedagogical Implications.................................................................96 5.3 Limitations of the Study...................................................................98 5.4 Recommendations for Further Studies…………………………...100 References............................................................................................................102 Appendices...........................................................................................................116. 政 治 大 B. Questionnaire on Writing Attitude (English version) .............................119 立. A. Questionnaire on Writing Attitude...........................................................116. C. Class Blog................................................................................................121. ‧ 國. 學. D. Guideline to Self-reflection Journal........................................................122. ‧. E. Revised Guideline to Self-reflection Journal...........................................123. sit. y. Nat. F. Self-evaluation Form on Portfolio & Questionnaire on the Writing. io. er. Class.........................................................................................................125 G. A Modified CEEC Scoring Criteria (大學聯考作文評分標準) ............128. al. n. v i n C h for Revision Analysis H. Yagelski’s Coding Schemes (1995) ....................130 engchi U. I. Interview Items.........................................................................................132 J. UCI (University of California, Irvine) Correction Symbols.....................134 K. Peer Editing Sheet...................................................................................136 L. Checklist on Process Writing & Essay ……............................................138. vii.

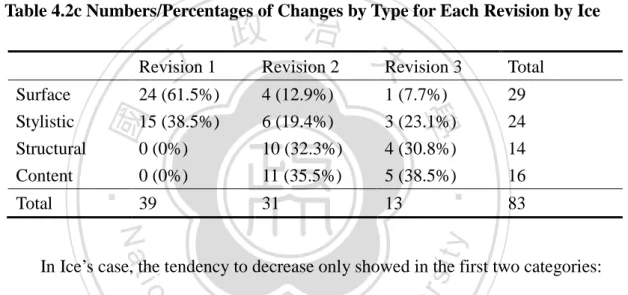

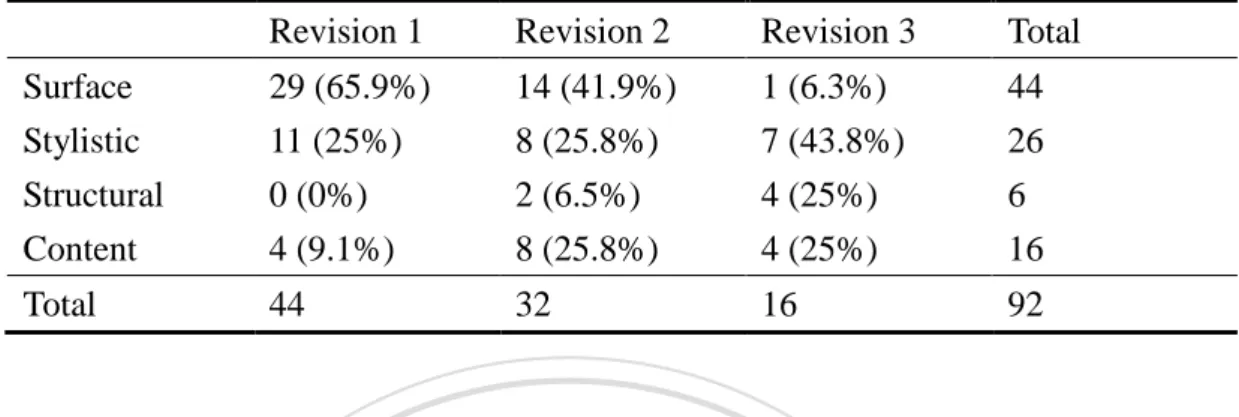

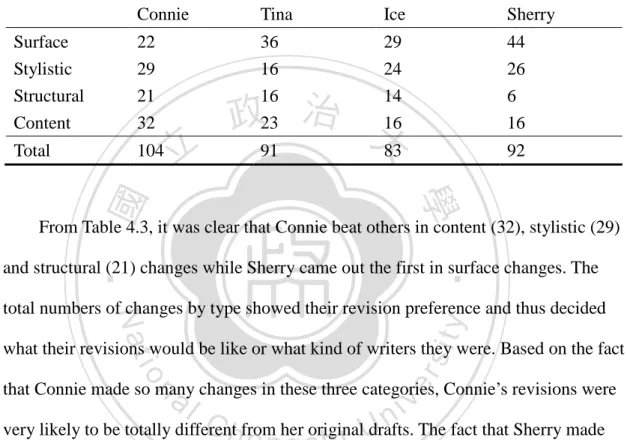

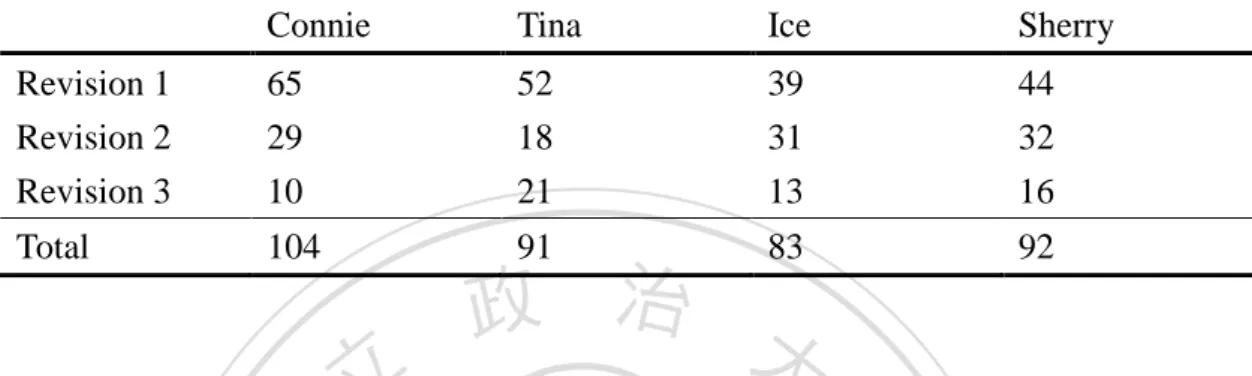

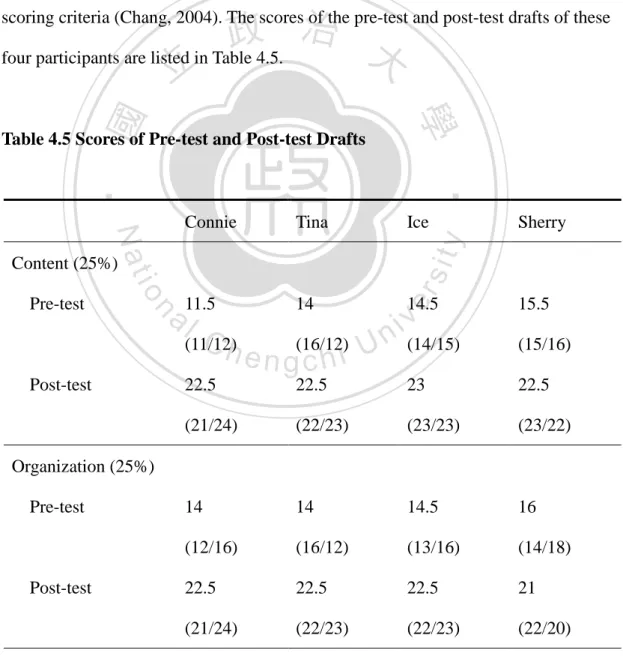

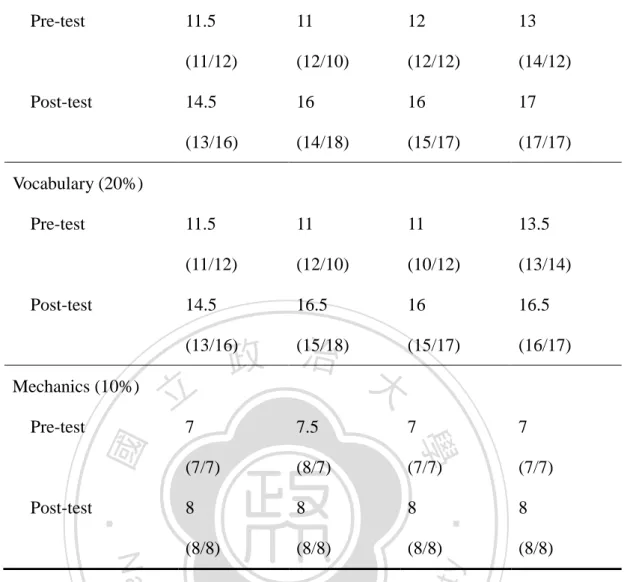

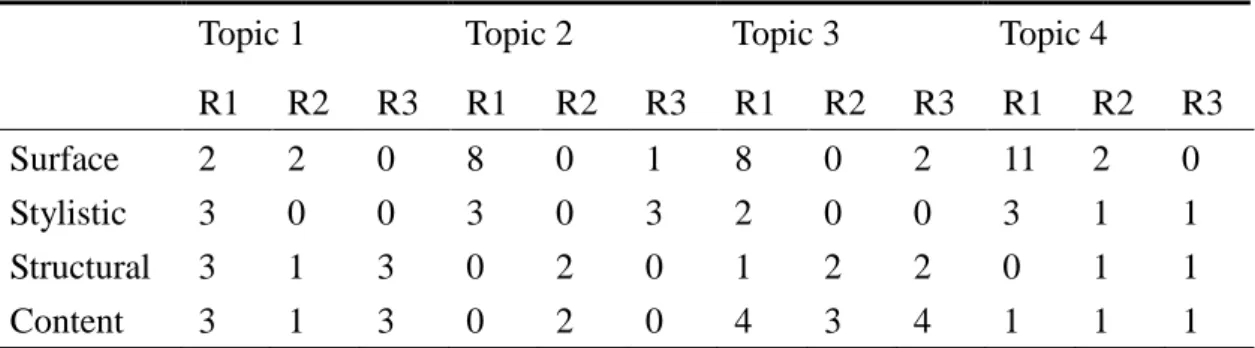

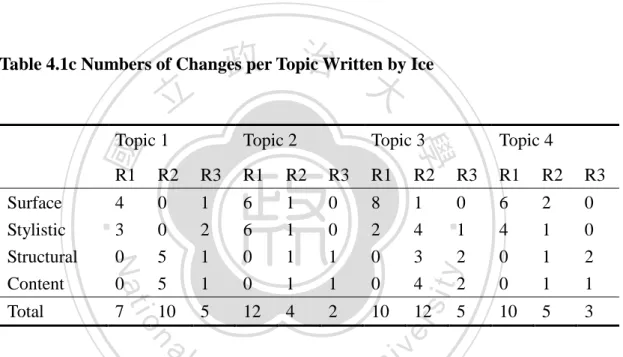

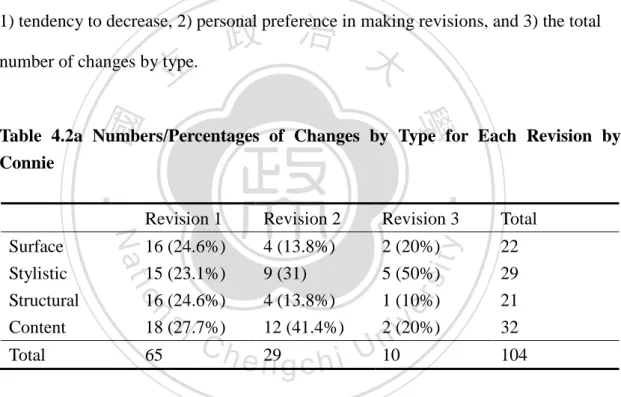

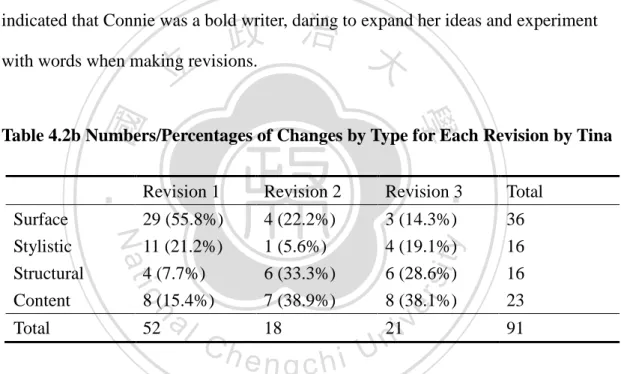

(8) List of Tables Table 4.1a Numbers of Changes per Topic Written by Connie..............................41 Table 4.1b Numbers of Changes per Topic Written by Tina..................................41 Table 4.1c Numbers of Changes per Topic Written by Ice.....................................42 Table 4.1d Numbers of Changes per Topic Written by Sherry...............................42 Table 4.2a Numbers/Percentages of Changes by Type by Connie…..……….......44 Table 4.2b Numbers/Percentages of Changes by Type by Tina.............................45. 政 治 大 Table 4.2d Numbers/Percentages of Changes by Type by Sherry..........................47 立 Table 4.2c Numbers/Percentages of Changes by Type by Ice................................46. Table 4.3 The Total Numbers of Changes by Type................................................48. ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.4 The Total Numbers of Changes per Revision……………………….....49. ‧. Table 4.5 Scores of Pre-test and Post-test Drafts...................................................51. sit. y. Nat. Table 4.6 Percentages of Progress..........................................................................52. io. er. Table 4.7 The Numbers of Words in Pre-test and Post-test Drafts........................53 Table 4.8 Results on Writing Attitude Questionnaire.............................................73. al. n. v i n Table 4.9 Score DifferencesC between Pre-test and Post-test hengchi U. Questionnaire………………………………………………………………......…74 Table 4.10 Regular Class vs. blog-mediated Process Writing Class…………......82. viii.

(9) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要 論文名稱:英語外語課程中,部落格融入『過程寫作』之教學: 個案研究 指導教授:林啟一博士 研究生:詹惠玲. 立. 論文提要內容:. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 幾十年來,過程寫作常因為『重內容輕形式』和『輕忽寫作成品』而導 致批評聲浪不斷。 近年來,部落格網誌的四大特色 — 自我表達、自我反省、. ‧. 互動和發布 — 吸引學者和語言學習者的注意。本文旨在探討部落格融入『過. sit. y. Nat. 程寫作』之教學如何影響四名台灣高三學生的寫作表現。文獻探討涵蓋過程. al. er. io. 寫作,部落格和三項共通因素 — 回饋、自我反省日誌和電子檔案評量。. v. n. 本研究的對象是研究者所教授的過程寫作班的四位高三學生。本研究的. Ch. engchi. i n U. 程序以寫作循環 (writing cycle) 為主軸。資料包括多次校訂 (multiple revisions)、兩篇草稿 (前後測)、學生寫作態度問卷、教師日誌(teacher’s log) 和訪談紀錄。首先,以 Yagelski’s coding schemes (1995) 和 Johnson’s (1994) 內 容和組織指標 (indicators of content and organization) 解讀多次校訂,以了解 學生的校訂類型 (types of changes in multiple revisions)。接著,分析前後測分 數的差距 (score differences)及文章長度 (the length of essay)、探討多次校訂與 前後測草稿的關聯性,再找出前後測草稿中的內容與組織指標,以顯示學生 在兩篇草稿的進步程度。訪談資料則用於探討部落格的功能、學生遇到的困 難和需要何種教師支援。至於學生的寫作態度,則以前後測問卷的分數差距. ix.

(10) (score difference) 為主,再以訪談紀錄作為佐證資料或疑點澄清。最後,與教 室情境有關的發現,則以教師日誌和訪談資料為主。 本研究的主要發現如下: 1. 學生有自己偏好的校訂類型 (types of changes in multiple revisions)。 2. 寫作班的四位高三學生在內容和組織方面有顯著進步。 3. 班級部落格在過程寫作的每個階段都有不同功能。 4. 多次校訂的枯燥須加以克服,以及建議實施老師與學生間的迷你會 議。. 政 治 大 教室情境所衍生的幾項發現。 立. 5. 在信心、焦慮、實用性與偏好四方面,學生寫作態度改變。 6.. 最後,本研究對過程寫作在實際教學上應用與未來研究方向提供建議。. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) ABSTRACT Over the past decades of practice in process writing, criticism over “the stress on content over form” (Badger & White, 2000) and the neglect of final writing product (Barnes, 1983) has never ceased. Considering that blog has attracted scholars and learners for its unique features — self-expression, self-reflection, interactivity, and publication, this researcher integrated blog into the instruction of process writing to investigate the writing performance of the four 12th graders.. 政 治 大 commonly found in both process writing and blog— feedback, self-reflection 立. The literature review covered studies on process writing, blog and three elements. journals and e-portfolio.. ‧ 國. 學. The participants of this study were four 12th graders of Taiwan’s high school. ‧. in a blog-mediated process writing class taught by the researcher. The procedure. sit. y. Nat. revolved around the process writing cycle, in which these four participants. io. er. repeated the recursive writing process. Data included multiple revisions, two drafts (pre-test and post-test), questionnaires on students’ writing attitude (pre-test. al. n. v i n and post-test), the teacher’s C logs and interviews. First, h e n g c h i U to obtain what types of. changes students made in multiple revisions, the 48 multiple revisions were coded by Yagelski’s coding schemes (1995) and Johnson’s indicators of content and organization (1994). Second, to investigate if the four participants made progress in content and organization, this researcher touched on four aspects of analysis: 1) the score differences between the pre-test and post-test drafts, 2) the length of essay, 3) a connection analysis between the multiple revisions and the two drafts and 4) a draft analysis using Johnson’s indicators of content and organization (1994). Third, the interview data helped to explore how the blog functioned in each step of process writing model, and to present the challenges students xi.

(12) encountered and the teacher support they needed. Fourth, to discover if these students experienced any attitude changes, she also calculated the score differences between the pre-test and post-test questionnaires in students’ writing attitude and verified the questionnaire results or clarified the unclear points with interview data. Finally, some other classroom-context-related findings were also revealed in the analysis of the teachers’ logs and the interview data. The major findings were listed as below: 1) students showed preference for making some types of changes in multiple revisions; 2) the four students in the. 政 治 大 organization; 3) the class blog functioned differently in each step of process 立. blog-mediated process writing class gained significant progress in content and. writing model; 4) the boredom of doing multiple revisions and the teacher-student. ‧ 國. 學. mini conference were the challenges encountered and the teacher support. ‧. recommended; 5) there were writing attitude changes in the four categories —. sit. y. Nat. confidence, anxiety, usefulness and preference; and 6) several findings were also. io. er. revealed in the context of classroom.. Some pedagogical implications and recommendations for future research on. n. al. i n C hat the end of the thesis. process writing were presented engchi U. xii. v.

(13) 1. CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION This chapter provides an overview of this study. It first explains how the researcher is motivated to conduct this study, describing the context of and the rationale for this study. Then the purpose of the study and its significance are stated.. 政 治 大 Of the four language skills, writing tends to receive the least amount of attention. 立. 1.1 Background & Motivation. Most instruction in English as a Second Language (ESL) focuses on developing. ‧ 國. 學. students’ skills and abilities in listening, speaking, and reading while ignoring the. ‧. development of students’ writing skills (Edelsky, 1982; Edelsky & Smith, 1989). This. sit. y. Nat. lack of attention to writing instruction has also led to a neglect of research in writing. io. er. compared to other skills (Graves, 1984). Another scholar, Harris (1985) concluded that only 2% of ESL instruction covered writing activities. Of this two percent, 72%. al. n. v i n Caspect was related to the mechanical such as syntax, punctuation, and U h e nofgwriting, i h c. spelling. Yet for L2 or EFL learners, writing is an essential skill for communicative or academic purposes. Apparently, writing has not got as equal attention as reading in Taiwan’s schools – a statement made in a study on the theses written by in-service English teachers. Analyzing 62 ETMA (Master of Arts in English Teaching) theses at National Taiwan Normal University from 2002-2006, Chuang (2007) observed that 23 theses focused on reading while only 11 on writing – an indication that reading is still the primary focus of English teaching in Taiwan. In both General Scholastic Test and Department Required Test, writing only takes up approximately one-fourth of the test.

(14) 2. while reading dominates the rest. With writing as the secondary focus in high schools, it is no wonder that more than twenty thousand students got zero on English composition in 2009, according to a report issued by the College Entrance Examination Center (CEEC) (as cited in Lee, 2009). Encouragingly, however, Chuang (2007) pointed out there has been an increasing attention to writing research ever since the writing sections (translation and composition) were required in both General Scholastic Test and Department Required Test. Mixed opinions on the draft of English composition in the College Entrance. 政 治 大 teachers (Chang, 1996), several professors (Lee, 2009; Yang, 2003) suggested that 立. Exam have long existed. Despite supportive voices from some high school English. writing should be abolished, for it only signifies an enormous gap of English teaching. ‧ 國. 學. between rural and urban areas or it displays an unfair evaluation of one-time draft. ‧. without proper consideration that “writing is a thinking process” (Zamel, 1982), where. sit. y. Nat. students need to write and revise again and again until they come up with a satisfactory. io. er. final product. Still others (Chang, 2009; Lee, 2009) even pointed out that there has long been a two-peak distribution of English composition score. Even though the English. al. n. v i n C h schools, it doesn’tUhelp students get more interested in education has started in elementary engchi English. It seems to end up that the younger students get to learn English, the earlier they quit learning English.. Although many published writing guidebooks are available on the market, they either fail to teach students how to develop writing competence through a step-by-step process writing model or ignore the necessity of developing content by connecting the real life experience to the writing. Four writing guidebooks written by local English teachers (Lee, 2003; Lin, 2009; Liu, 2005, 2009) include only students’ composition samples together with sentence pattern practices or fragments of writing strategies, to name a few, brainstorming or outlining. Even one of the best selling writing books in.

(15) 3. Taiwan, Writing from Within, written by native speakers (Gargagliano & Kelly, 2001), though discussing writing strategies systematically, pays little regard to building content by writing about the real-life experience, with which students can write more and with greater fluency and satisfaction (Perl, 1980). Another two books, Smart Writing for Senior High (Shih et al, 2004) and Classroom Composition for Senior High (Chen et al, 2007), do cover themes closely related to teenagers’ life and introduce outlining and brainstorming strategies, but fail to provide a writing process model to help students develop their writing ability step by step. This inspires the. 政 治 大 experience following a recursive process writing model. 立. present writer to design a writing course where students can write about their real life. Other than insufficient resources, the way writing is taught in Taiwan’s high. ‧ 國. 學. schools is also more product-oriented than process-oriented. Since students are only. ‧. required to write a one-time essay in the two Entrance Exams (General Scholastic. sit. y. Nat. Ability Test and Department Required Test), most of the English teachers in high. io. er. schools focus on training students how to write a one-time essay within a time limit. Seldom do they ask students to write in the process writing model: prewriting,. al. n. v i n Cpublishing drafting, revising, editing and 1986). Most teachers just give U h e n g(Applebee, i h c. students a topic to write about in a given time limit, ignoring the fact that “writing is a process through which meaning is created” (Zamel, 1982). In such a case, students care less about how to develop their writing ability through a necessary writing process than what scores they will get from this one-time essay. What’s worse, some students memorize some sample essays or follow a fixed formula to fit in the format required for the Entrance Exams. With limited teaching hours and constant focus on the final product of one-time essay, most English teachers in high schools are reluctant to implement the process writing model in writing practice. As a result, the one-time essay writing practice is popular in the English writing class of high schools.

(16) 4. in Taiwan while the process writing is never a grave concern. Stress on product over process can also be found in local theses on writing. A search in Electronic Theses and Dissertation System revealed that most writing-related theses focus on syntax, collocation analysis or error analysis while several explored the use of model essays in writing class. On the other hand, theses on process writing strategies (Chang, 2002; Huang, 2002; Huang, 2004) are comparatively few. Even in the United Kingdom and the United States, where process writing has. 政 治 大 issues regarding the practice and deficiency of process writing. Despite the fact that 立. been widely practiced over several decades, there still remained some unresolved. process writing was introduced to the L1 context for several decades, product. ‧ 國. 學. approach has still been dominant in the UK and the United States (Purves, 1992). In. ‧. the United States, Harris and Graham (1996) argued that few activities were practiced. sit. y. Nat. in the classroom to help students to develop their writing process, even though. io. er. process writing started to be implemented in America. In the UK, it was believed that the introduction of a product-focused National Literary Strategy discouraged. al. n. v i n C h of process writingU(Hilton, 2001). Meanwhile, recursive writing, a core concept engchi. opponents of the process writing often criticized it for its loose structure (Baines, Baines, Stanley & Kunkel, 1999) and failure to see product as important as the writing process (Barnes, 1983). Barnes (1983) even questioned if Zamel’s process-oriented approach would ultimately improve students’ final writing product, which is indispensable in the real life, especially for college courses. In this regard, more and more scholars (Blake, 1995; Dyson, 1992; Lensmire, 1993) called for teachers and students to connect process with product and reversed their concept that the process can be isolated from the product. Therefore, how to improve the final product in the process writing classes becomes a new trend of today’s process writing..

(17) 5. Though process writing prevails in L1 and L2 context, few studies on process writing have been conducted in an EFL classroom (Pennington & Brock, 1992; Pennington, Brock & Yue, 1996; Pennington & Cheung, 1995; Pennington & So, 1993). With limited research on process writing in EFL context and controversies over the practice and deficiency of process writing in either L1 or L2 context, the researcher feels the need for further investigation to explore a proper way to implement process writing in EFL context. Despite the practice difficulties and deficiencies of process writing, technology. 政 治 大 started to overthrow the traditional writing habits. In the United States, students are 立. may offer a satisfactory resolution. In recent years, the use of computer in writing has. reported to use word-processing tools and online resources in writing practices. ‧ 國. 學. (Applebee, 2009). The abundance of online resources provides students with. ‧. inspirations and reference to enrich the writing content while word-processing tools. sit. y. Nat. are used to improve the accuracy of final written products. It seems that the computer. io. er. may be a good facilitator for the development of content and the improvement of final products. Supposedly, in a process writing class combined with the use of computer,. al. n. v i n C h and the attention the content would be well developed to final products be equally engchi U paid.. Providing basic word-processing function and links to online resources, blog has become a new form of publication popular among teenagers and teachers (Lowe & Williams, 2004). Without a doubt, blog and process writing do have some features in common: self-expression (content), self-reflection (journal), interactivity (commenting) and publication (e-portfolio). With these four unique features, blog may be a good medium to reinforce the practice of process writing. First, the text-based and text-rich content makes blog an ideal forum where students develop their writing content through self-expression. Second, originally an online journal in a reverse.

(18) 6. chronological order, blog may also serve as a great platform for students to document their writing process online through self-reflection. Then, leaving comments on the blogs, students improve their writing through interaction with others. Finally, as a new form of publication (e-portfolio), blog may also help students develop a sense of audience in mind. To sum up, with these four features, – self-expression, self-reflection, interactivity and publication – the blog provides a great chance to improve the practice of process writing. However, few studies have been seen to practice a process writing model in a blog-mediated environment.. 政 治 大 blog-meditated process writing was therefore designed. Since most local research on 立 To explore the possible relationship between process writing and blog, a. blog-mediated writing has been conducted in college (Hsiao, 2006; Lin, 2007; Peng,. ‧ 國. 學. 2007; Wang, 2006), this present researcher feels the need to explore how the high. ‧. school students respond to the process writing class in the mediation of blog.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 1.2 Purpose of the Study. The purpose of this study aims to explore if process writing is effective in a. al. n. v i n blog-mediated writing class C for senior high schoolU h e n g c h i students. More specifically, its. purpose is to investigate the following: 1) whether process writing in a blog-mediated environment influences students’ writing performance, 2) how blog helps students in each step of process writing, 3) challenges students encountered plus with teacher support, and 4) their writing attitude.. 1.3 Significance of the Study This study will provide useful insights or implications to English learners, English writing instructors, book publishers, and interested researchers. For English learners, a new focus on meaning over form should be reminded in writing practice. For English.

(19) 7. writing instructors, it is hoped that the findings may provide another perspective and alternative to the teachers of EFL high school writing. For book publishers, they may be encouraged to publish more writing textbooks connecting the technology with process writing. For interested researchers, they may explore more potential issues on teaching EFL writing in a computer mediated communication environment.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(20) 8. CHAPTR TWO LITERATURE REVIEW This chapter mainly discusses studies on process writing and blog mediation. Studies also touch on three elements commonly found both in process writing and blog, i.e., feedback (including face-to-face peer review, teacher’s feedback and computer-mediated peer review), self-reflection journal and e-portfolio.. 2.1 Process Writing. 立. 政 治 大. When defined, process writing often refers to its counterpart “product writing.”. ‧ 國. 學. Known as a traditional paradigm and based on a behaviorist theory of learning,. ‧. product writing focuses on the completed written product and language rules. The. sit. y. Nat. writing approach didn’t switch to the writer’s cognitive process until Emig (1971). io. thinking process while writing.. al. er. used “think aloud” protocol to collect information about L1 high school students’. n. v i n C h writing emphasizes As its name suggests, process “process,” “making meaning,” engchi U. “invention” and “multiple drafts” rather than “accuracy” and “pattern” (Raimes, 1991). A typical process writing class features the common use of journal, peer. collaboration, revision and stress on content over form (Badger & White, 2000). According to Brown (2000), process writing is more writer-focused while product approach pays a great deal of attention to model composition, form and accuracy. To sum up, process writing centers on how students write and learn in the process of writing.. 2.1.1 Process Writing Model.

(21) 9. Flower and Hayes (1981) established the cognitive model of writing process, including planning, writing and reviewing. Many other researchers have addressed different stages in the process model. Applebee (1986) proposed a five-step process model: prewriting, drafting, revising, editing and publishing. A few years later, Tompkins (1994) revised it as a model with planning, drafting, revising, editing and publishing. Tribble (1996) later provides a four-stage model, including prewriting, composing/drafting, revising and editing. Although researchers provide different stages of process model, the core procedure of process writing remains the same. For. 政 治 大 “prewriting” stage while Tribble’s model skips the “publishing” stage. Among all 立 example, in Tompkin’s model, the “planning” stage is very similar to Applebee’s. these models, Flower and Hayes’ three-stage model has been recognized as the most. ‧ 國. 學. typical and widely used. However, Applebee’s five-step process model was adopted in. sit. y. Nat. step closely connected to blog format.. ‧. this study for two reasons: distinctive definition of every step and unique publishing. io. er. Harp and Brewer (1996) further described the process model as a recursive process. The “recursive” writing process means moving back and forth or non-linear.. al. n. v i n In other words, writers may C not follow the exact order h e n g c h i U of these stages. For example, they may brainstorm first before writing a draft. While revising, they may come up. with more ideas, so they may go back writing a second draft. The procedure may go on and on until the writer is satisfied with his work. To sum up, process writing is writer-centered, which is quite different from the traditional writing cycle where the teacher assigns students a topic for them to write about, and then corrects the written product with a red pen. That is to say, process writing is more learner-centered whereas product approach is more teacher-centered.. 2.2 Previous Studies on Process Writing.

(22) 10. 2.2.1 Studies in L1 Context As the popularity of process writing prevails, there has been much research spelling out its benefits on writing. In the States, Goldstein and Carr (1996) conducted a study analyzing the data drawn from the 1992 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in writing. The study reported that students become better writers if process writing is encouraged in class. Again, gathering relevant data from NAEP, Applebee (2009) made a survey on how students approached their school writing tasks after twenty years of process writing practice in high schools. Designed in. 政 治 大 writing-related activities in writing tasks, the survey obtained some interesting results. 立 multiple response questions to investigate how many students used process. According to the survey, over 60% of students reported that they almost always make. ‧ 國. 學. changes to fix (revise) mistakes, and over 30% of them write more than one draft. ‧. (multiple drafts), while only 15% of them use strategies involving interaction with. sit. y. Nat. others, like brainstorming (prewriting). And 25% ~28% of them work with others in. io. er. pairs or small groups. This indicates that process writing goes in parallel with product writing in the L1 context, with product writing overweighing process writing.. n. al. Ch. 2.2.2 Studies in L2 Context. engchi. i n U. v. With few original process writing models in second language writing, most writing models in L2 context were directly borrowed from L1 writing research (Cumming & Riazi, 2000). As one of the original models developed in L1 context, process writing was gradually adopted in second language writing. Two pioneers, Zamel (1983) and Barnett (1989), held a positive view about the effect of process writing on advanced learners in an ESL context. Cumming (1989) also came into the similar positive results in her research. Unlike Zamel’s study focusing on how advanced ESL learners developed the writing process, Raimes (1985) found that less.

(23) 11. skilled ESL writers could also be engaged in the discovery of meaning as well as advanced ESL writers. Raimes (1985) further discovered “the attention to writing process is necessary but not sufficient.” Students need to spend more time on everything. In other words, they should develop four skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing) to acquire the background knowledge they need in developing their writing ability in L2.. 2.2.3 Studies in EFL Context. 政 治 大 example two studies, conducted by Pennington (1996) and Sasaki (2000) respectively. 立 Studies on process writing in EFL context are comparatively scarce. Take for. Pennington (1996) gained mixed results in his study on 8 classes of Hong Kong’s. ‧ 國. 學. secondary school students, finding that the teacher’s and students’ attitude toward. ‧. process writing was positively correlated. That is, students’ attitudes toward the. sit. y. Nat. practice of process writing in class varied based on teachers’ behavior before and. io. er. during the instruction. On the other hand, In her study on three paired groups of Japanese EFL writers (experts vs. novices, more-skilled vs. less-skilled student writers,. al. n. v i n novices before and after six C months of instruction),USakaki (2000) disclosed the hengchi following findings:. The results revealed that a) before starting to write, the experts spent longer time planning a detailed overall organization whereas the novices spent a shorter time making a less global plan; b) once the experts had made their global plan, they did not stop and think as frequently as the novices; c) L2 proficiency appeared to explain part of the difference in strategy use between the experts and novices; and d) after 6 months of instruction, novices had begun to use some of the expert writers’ strategies. (p. 259) However, the debate between content and form has never ceased ever since process writing was adopted in EFL context. Seeing writing as “a process of.

(24) 12. discovering meaning” (Zamel, 1982), process writing has long laid stress on content over form (Badger & White, 2000). Teachers are seen as facilitators, who should give positive feedback on the content rather than offering red-pen correction to ensure the accuracy in form. In fact, the direct red-pen correction should be avoided lest too much of it obstruct the learners from generating ideas (Barnett, 1989). Learners are encouraged to develop content first, leaving the form related errors till the final writing. In a word, meaning should always be treated first before the language skills. However, EFL learners think differently. Contrary to the concept of thinking of. 政 治 大 for academic or professional success (Leki, 1990). For EFL learners, a good final 立. writing as self-expression, writing in an EFL context often indicates a pressing need. product may offer far more direct and solid benefits than the abstract writing process. ‧ 國. 學. of “discovery meaning” (Zamel, 1982), and the form deserves as equal attention as. ‧. the content. The neglect of final writing product (Barnes, 1983) and the stress on. sit. y. Nat. content over form (Badger & White, 2000) would make it impossible to satisfy EFL. io. er. learners’ needs. Therefore, how to strike a balance between content and form remains a controversial issue when it comes to the practice of process writing in an EFL. al. n. v i n C hcome up with a possible context. In this regard, we may solution by using computers. engchi U As mentioned before, the access to online resources and the word-processing tools. may help learners both in content and form, thus eventually improving the quality of final product. Based on the fact that 90% of today’s bloggers are young adults (Nussbaum, 2004), blog, with links to online resources and word-processing tools as well, seems to be an ideal choice to strike a balance between content and form. Next, a review regarding previous studies on writing through blog is introduced.. 2.3 Previous Studies on Writing through Weblogs 2.3.1 Weblogs in Education.

(25) 13. Weblogs or blogs, have been widely used ever since 1997. Now educators are drawn by the charm of blog as well. Originally as online personal journals in a reverse chronological order, blogs have a lot of benefits in developing students’ reading and writing skills. Unlike chatroom, a synchronous form of communication, blogs provide a less pressured asynchronous forum for readers and writers to interact by leaving comments and connecting to related links on the Internet, and thus help them to become regular writers and/or readers (Ducate & Lomicka, 2008). The co-authored community blogs (or class blog) may help students achieve collaborative assignments. 政 治 大 students express and reflect to the degree of deep learning (Bartlett-Bragg, 2003). 立 under the teacher’s guidance (Armstrong & Retterer, 2008). Blogs can also help. Through micropublishing, students develop a sense of ownership and authorship if. ‧ 國. 學. they know they are writing for a real audience (Godwin-Jones, 2003). From. ‧. Vygostky’s sociocultural perspective, students’ knowledge is constructed through the. sit. y. Nat. social interaction with others over time, and weblogs do offer a forum for interaction. Ferdig & Trammell (2004) also made the following statement:. io. n. al. er. The four benefits of student blogging include:1) the use of blogs helps students become subject-matter experts; 2) the use of blogs increases student interest and ownership in learning; 3) the use of blogs gives students legitimate chances to participate; and 4) the use of blogs provides opportunities for diverse perspectives, both within and outside of the classroom. (p. 16). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Oravec (2002) claimed that blogging may also enhance critical thinking, literacy, and promote the use of the Internet as a research tool. With so many researchers advocating the advantages of blogs, blog-mediated studies are now a new territory to explore.. 2.3.2 Previous Studies on Writing through Blog Many researchers are now more interested in the application of blog in language.

(26) 14. learning. Lowe and Williams (2004) pointed out three reasons: Educators are in favor of integrating blogs into language learning because they are easy to establish, they give students opportunities to write to a real audience, and they enable two-way communication between authors and readers. (p. 183) Besides, weblog is a convenient tool to facilitate writing because of its text-based context. As the Internet prevails, teachers are more willing to integrate blog into their writing practice. It is not surprising that educators are beginning to explore the possibilities of using blog in L1 or L2 writing. In studies that incorporated blog into writing in the. 政 治 大. collaboration projects, positive results were achieved (Boling, Casteck, Zawilinski, &. 立. Barton, 2008) and the students were reported to have high involvement (Witte, 2007).. ‧ 國. 學. The easy-for-use blog makes it easy for both students and teachers to publish their written works online. Writing blog, hence, can offer students an interactive way to. ‧. improve their writing skills and to encounter or develop new ideas through discussion. y. Nat. sit. with others. Studies on free written self-expression on the blog without consideration. n. al. er. io. of errors among college students in L1 context reported positive effects on writing,. i n U. v. too (Murray & Hourigan, 2008; Smith, 2008). In a word, the above studies,. Ch. engchi. incorporating blog into writing either in L1 or L2 context, proved that blog can benefit students in collaboration projects and self-expression. Although research related to blogs in the EFL writing is in the beginning stage, there are still many interesting findings. Bloch (2007) described how blogging helped Abdullah, a Somali student, to develop literacy, concluding that blogging is not only a new literacy tool but also a pathway to academic writing. In a study on an EFL class, Oladi (2005) found that students achieved more confidence by participating in a blog course, where they gained authorship throughout the course. She concluded that blogging provides a forum for students to express their voice. Two studies (Ducate &.

(27) 15. Lomicka, 2008; Ward, 2004) also reported that students, either as blog readers or blog writers, gained benefits from blogging. Lee’s (2006) case study suggested that social network and online community were very helpful for students who were learning Korean. Many other studies (Armstrong & Retterer, 2008; Horvath, 2009; Miura & Yamashita, 2007; Soares & Naval, 2008) also echoed positive results of blogging in EFL writing. Still, there is little research regarding the integration of blog into process writing in an EFL setting.. 政 治 大 In process writing, feedback (including peer review and teacher’s feedback), 立. 2.4 Common Elements in Process Writing and Blog-mediated Research. self-reflection journal and e-portfolio are three significant elements helping students. ‧ 國. 學. to develop individual writing process. With the features of interactivity (commenting). ‧. (Ducate & Lomicka, 2008) , reflection (journal) (Barlett-Bragg, 2003) and publication. sit. y. Nat. (e-portfolio) (Godwin-Jones, 2003), weblogs, though not paper-based, also possess. io. er. the above three elements in computer-mediated mode. The following review will focus on these three elements commonly found both in process writing and. n. al. blog-mediated research.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.4.1 Feedback (Peer Review and Teacher’s Feedback) The following will discuss two different kinds of feedback in process writing: peer review and teacher’s feedback. Then, computer-mediated peer review (comment on the blog) will also be discussed. 2.4.1.1 Peer Review Peer review, also referred to as peer feedback, peer response or peer editing, has long been considered one of the key features of process writing. The National Conference of Teachers of English (NCTE, 1985) sees peer review as a primary.

(28) 16. source of learning in the following statement: Students should be encouraged to comment on each other’s writing, as well as receiving frequent, prompt, individualized attention from the teacher. Reading what others have written, speaking about one’s responses to their writing and listening to the responses of others are important activity in the writing classroom. Textbooks and other instructional resources should be of secondary importance. (NCTE 2) Research concluded that active participation in peer review leads to improved writing skills (Althauser & Darnall, 2001). In the most widely accepted Hayes and Flower’s planning-writing-reviewing process writing model, peer review is frequently practiced. 政 治 大. to help the learners to improve their problems on content, organization, grammar and. 立. style (Jacob, et al, 1998; Keh, 1990).. ‧ 國. 學. Regarding how to conduct an effective peer review, scholars have varied views. It is believed that training sessions are required to help students offer specific and. ‧. meaningful feedback (Berg, 1999) and the use of worksheets or checklists in the peer. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. 2001; Roskelly, 1992).. sit. review should reinforce the efficiency of peer review (Damashek, 2003; Gleason,. i n U. v. Concerning the implementation of peer review in class, two aspects should be. Ch. engchi. taken into account: the size of the peer review group and the form of training. The size of peer review group should always be kept small: three or four people at most (Rollinson, 2005; Zhu, 2001), and the paired peer review is “preferred by most EFL students” (Min, 2005). As for the pre-training sessions, watching a video on peer review (Zhu, 2001) and offering a broad categories under which they needed to write comments (Tsui & Ng, 2001) are recommended. Considering that it’s too time-consuming to watch a video, the researcher takes the 2nd approach providing a worksheet with listed categories as a guideline to conducting a paired peer review. Arguments on the implementation of peer review have never stopped, even.

(29) 17. though there were many studies spelling out the advantages of peer review. Peer review offers students the need to write to an audience (Rolliston, 2005), encourages a two-way interaction and collaboration in a communicative process (Liu & Carless, 2006), and proves useful not only for those who receive it, but for those who provide it, as it allows students to develop the ability to judge others’ works according to the given standards and this ability will later be transferred to their own works (Nicol & MacFarlane-Dick, 2006). In a study aiming to explore the benefits of peer review, Tsui & Ng (2000) discovered that even though learners in ESL context favor the. 政 治 大 sense of audience; b) raising learners’ awareness of their own strengths and 立. teacher’s feedbacks, peer review still possesses the following benefits: a) enhancing a. weaknesses; c) encouraging collaborative learning, and d) fostering the ownership of. ‧ 國. 學. text. However, there were still several voices in objection to the practice of peer. ‧. review. For example, Hyland and Hyland (2006) suggested that foreign language. sit. y. Nat. learners generally value teacher’s feedback more. Moreover, several studies have also. io. er. shown that students are unwilling to give peer review for the following reasons: a) they perceived their ability not to be good enough to provide peer feedback; b) they. al. n. v i n see it as the teacher’s job to C provide feedback, andU h e n g c h i c) they resist having power over. their peers or their peers having power over them (Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Liu & Carless, 2006). Other than the controversies over the implementation of peer review, there still remain some problems when conducting a peer review in both L1 and L2 context. In L1 context, students tend to give “false impression of the essay’s strengths” (Ransdell, 2001) or “comments typically found in the peer reviews were generally uncritical” (Althauser & Darnall, 2001). What’s more, teachers often avoid group work, feeling guilty when they are ‘not actually teaching” (Roskelly, 1992). A survey found that many teachers considered peer review to be additional work with marginal results.

(30) 18. (Belcher, 2000). As for peer review in L2 context, Nelson & Murphy (1993) pointed out two reasons why L2 learners held a different view on peer review. First, since English isn’t their native language, L2 learners may feel doubtful about the validity of their peer’s responses. Second, many L2 learners think that the teacher, usually regarded as the only authority in the classroom, may be the only reliable source to make valid and credible comments. Another major complaint about the peer review is that students, especially untrained L2 learners, do not know how to give specific, meaningful and helpful peer responses (Ferris, 2003). One thing that deserves our. 政 治 大 because of their reluctance to criticize others (Carson & Nelson, 1994). In a nutshell, 立 mention is that peer review groups are less successful among Chinese students. arguments about the practice of peer review still remain inconclusive.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.4.1.2 Teacher’s Feedback. sit. y. Nat. Research on teacher’s feedback doesn’t lead to solid or conclusive results, either.. io. er. In a research review regarding the effectiveness of teacher feedback, Semke (1983) suggested that no matter how the teacher’s written feedback was delivered, there was. al. n. v i n C h significant improvements no evidence that it would produce in students’ writing. engchi U. However, in a study examining over 1600 comments written by teachers, Ferris (1997) concluded that “a significant proportion of the comments appeared to lead to substantive student revision….” In comparison with peer feedback, teacher feedback seems more preferable to learners. In a survey on 81 ESL university students, Zhang (1995) found that most of the respondents (94%) preferred teacher feedback over peer or self-directed feedback. In general, most research comes to the similar conclusion that learners prefer teacher feedback to peer feedback, though learners welcome peer feedback as well (Hu, 2005; Jacob et al., 1998; Tsui & Ng, 2000). In short, teacher’s feedback is more valued than peer feedback. Students’ attitudes toward peer review.

(31) 19. are varied, but they generally believe peer feedback can be useful. Concerning the teacher’s feedback, there are two kinds: direct feedback and indirect feedback (Bitchener et al., 2005). Direct feedback means the teacher identifies an error and provides the correct form, while the indirect feedback means the teacher indicates an error without providing a correction. In a Chinese EFL writing context, teachers usually try to review students’ essays word by word and correct every single problem they find. The great efforts are very time-consuming but not always valued by students. Teachers don’t need to correct every mistake; instead,. 政 治 大 Hyland (1990) suggested “minimal marking” by using correction codes; that is, the 立 they can use indirect feedback. Concerning the way to practice indirect feedback,. teacher marks errors with correction codes, which identify the type of errors. This way,. ‧ 國. 學. students are given a space for active correction instead of reading the teacher’s. ‧. correction written in red pen. Teachers may as well leave comments at the end or on. sit. y. Nat. the margin of essays; however, their criticism should be toned down and paired with. io. er. praises (Hyland & Hyland, 2001). Based on the above arguments, the present researcher chose to give indirect feedback in this study. Errors marked in correction. al. n. v i n C h on the drafts U codes and content-related comments served as cues for students’ engchi. discussion when conducting a peer review. It was expected that the combination of teacher’s feedback and the peer review would help students to solve questions through interaction and collaboration. The studies on peer review and teacher’s feedback provide us a brief summary of practice and effect of these two kinds of feedback. Studies related to another kind of feedback will be discussed as below. That is, computer-mediated peer review (CMPR), mainly referred to comments on the blog,.. 2.4.1.3 Computer-mediated Peer Review (CMPR).

(32) 20. As technology advances, the computer-mediated peer review (CMPR) has become a new mode in practice and research. Two broad options are available: one is synchronous writing, where students communicate with each other in real time via the Internet chat site, and the other asynchronous writing, where students communicate in a delayed way, such as via e-mail, BBS or blog (Hyland, et al., 20006). Three advantages were reported in CMPR (Warschauer, 1997). First, students are allowed to take a more active role when seeking feedback. Then comments are stored in the database for later printout. Most important of all, students will feel less pressure. 政 治 大 ESL learners who are reluctant to criticize others in a FFPR because of its particular 立. in a CMPR than in a face-to-face peer review (FFPR). It’s especially true of Chinese. culture where they “generally work toward maintaining group harmony and mutual. ‧ 國. 學. face-saving to maintain a state of cohesion” (Carson & Nelson, 1994).. ‧. Several studies concerning the effect of CMPR gained positive results. First, in a. sit. y. Nat. study aiming to compare the difference between CMPR group and FFPR group, the. io. er. former group was reported to produce a higher percentage of revision-related comments (Liu & Sadler, 2003). Then Catera & Emigh’s (2005) study of a blog. al. n. v i n project further revealed twoC major findings: a) theU h e n g c h i amount and quality of peer. feedback influenced students’ motivation to post comments, and b) peer feedback was equally important and motivating as tutor feedback. With so many positive results on CMPR, attention is drawn to investigate if CMPR could replace the traditional FFPR. In Ho and Savingon’s (2007) study, investigating the use preference of FFPR and CMPR, 72% of the learners indicated that they preferred the combination of these two. Li (2009) further suggested that the new emerging CMPR be used only as a supplement to reinforce the FFPR. In this regard, the present researcher decides to use the two-step procedure (FFPR CMPR) in this study, hoping that students can benefit from peer reviews in different modes while making revisions..

(33) 21. 2.4.2 Self-reflection Journal As a means to facilitate reflective practice and encourage critical thinking, journal writing has been promoted by educators in many fields (Bain et al., 1999). A journal is one type of writing assignment that requires the writer to think about something, and to record his/her thoughts about it. As Hedlund et al. (1989) put it: As a literary form, the journal falls roughly between the diary and the log: it consists of regular, though not necessarily daily, entries by which the writer focuses and reflects upon a given theme, or a series of events and experiences. (p. 108). 政 治 大 Many studies have立 reported the benefits of journal writing, such as a tool to. ‧ 國. 學. convey the importance of writing (Yinger, 1985) and a way to engage students more in learning (Connor-Greene, 2000). Offering a first-person account of language. ‧. learning or teaching experience, learning journal serves as a means to develop. sit. y. Nat. reflective practice, thus helping to build up the process of one’s own learning (Carroll,. n. al. er. io. 1994). As a reflective tool, the learning journal can promote and document the. i n U. v. personal growth, development and transformation and provide opportunities for. Ch. engchi. learners to make meaning from experiences through reflection (Diamond, 1991). Journal writing has been used extensively to enhance reflection. Several studies suggested that reflection is enhanced in the computer mediated environment because students have an easy access to journals, more time to read, re-read or compose thoughtful messages (Burge, 1993; Davie & Wells, 1991). In the present study, the self-reflection journal is considered a requisite as a means to document learners’ writing process, as a reference to make revisions and as a source of data collection.. 2.4.3 E-portfolio.

(34) 22. Portfolio has been widely used as a learning and assessment tool in Europe, the United Kingdom, and United States (Council of Europe, 2006; Hamp-Lyons & Condon, 2000; Klenowski, 2002). While producing their portfolios, learners have an opportunity to monitor their own progress and take their own responsibility for learning. By documenting growth over time through collection of their works, portfolios can help students reflect and confirm their learning efforts (O’Malley & Pierce, 1996). Hence, the core concept of portfolio lies in self-assessment guided by learners (Hirvela & Pierson, 2000). As the web and multimedia technologies advance,. 政 治 大 There are several different definitions on e-portfolios, but Barnett’s (2005) is the most 立 the focus on portfolios has been shifted from paper-based portfolio to e-portfolio.. frequently quoted.. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. E-portfolio uses electronic technologies as the container, allowing students/teacher to collect and organize portfolio artifacts in many media types (audio, video, graphics, and text) and using hypertext links to organize the material, connecting evidence to appropriate outcomes, goals or standards. (p. 5). sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. With the evolution of networks and the web, it is easier for students to create,. i n U. v. store, and publish their academic work online, namely, an e-portfolio. In the United. Ch. engchi. States, Europe and Australia, e-portfolios have started to be implemented in the classroom (Batson, 2002). Compared with the paper-based form, e-portfolio possesses more of other benefits. First, e-portfolio is easier to maintain, edit and update than its paper counterpart; students’ works can be collected, stored and managed electronically, taking very little or no physical space, and the peer and teacher feedback can be enhanced as well since the Internet is available at any time or any place (Heath, 2002). Meanwhile, the online environment helps students be more aware of their peers as the audience and thus create their community of writers (Wall & Peltier, 1996). In short,.

(35) 23. the open web space system provides a cyber space for e-portfolio storage and also serves as basis for students-centered empowerment and motivation for meaningful learning, thus promoting their autonomy (Barrett, 2004). The weblog is good for e-portfolio assessment for three reasons (Chan & Ridgway, 2006). First, weblogs document learners’ progress and blogging helps them to improve their ideas and insights through self-evaluation. Second, the use of weblog also helps the teacher make assessment because weblogs offer a clear and permanent record of students’ progress. Most importantly, living in a digital world, learners. 政 治 大. embark on personal explorations and learning adventures on the blogosphere, thus fostering their reflection.. 立. In addition to the above benefits of using weblog as e-portfolio, Chen and Bonk. ‧ 國. 學. (2008) further proposed several others. Weblog posting presents a formative. ‧. assessment through reflection and reveals students’ thinking, understanding, and. sit. y. Nat. errors in learning. These postings also help students explore a topic or idea in great. io. er. depth or even develop it into a paper or thesis. Instructors may also reflect on where they should alter their teaching approaches or revise related teaching materials. The. al. n. v i n C hthe researcher to U above-mentioned studies inspire include e-portfolio in the present engchi study for data collection and assessment.. 2.5 Research Questions Although process writing has been prevailing in L1 context for decades, arguments over the suitability of practicing process writing in an EFL context has never stopped for a mere reason: the neglect of final writing product (Barnes, 1983) and the stress on content over form (Badger & White, 2000). Aiming to strike a balance between content and form and explore possible ways to improve the final written product, the present study hopes to find if process writing can be effectively.

(36) 24. practiced in the mediation of weblog. Listed below are the research questions raised. 1. What types of changes students made in the multiple revisions in the blog-mediated process writing class and what information does the revision analysis provide? 2. To what extent does the weblog-mediated process writing class contribute to the development of students’ writing ability in content and organization? 3. How does weblog help students in each step (pre-writing, drafting, revising/editing and publishing) of process writing?. 政 治 大 blog-mediated process writing class? 立. 4. What challenges are involved and what kind of teacher support is needed in the. 5. What are students’ attitudes toward writing after taking the blog-mediated process. ‧ 國. 學. writing class?. ‧. 6. What other findings can be derived from this blog-mediated process writing class. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. in term of the context of the classroom?. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(37) 25. CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY The present study aimed to investigate how the instruction of process writing integrated with blog influenced the individual performance of these four 12th graders of high school in process writing. The research method falls into four sections, where participants, instruments, procedure and data analysis were described respectively.. 3.1 Participants. 立. 政 治 大. The participants of the present study were four12th graders of a public senior. ‧ 國. 學. high school situated in the northern part of Taiwan. This school is ranked among the. ‧. above average with the percentile rank of BCT (Basic Competence Test) score at. y. Nat. 88-90. The four participants were selected from an elective writing class taught by the. er. io. sit. researcher. This writing class was targeted at the 12th graders mainly because they were capable of expressing themselves in English with larger vocabulary and a better. al. n. v i n writing skill while preparingC for the two-paragraphUor picture-prompted writing in the hengchi entrance exam.. At the beginning of the present study, several individual inquiries were made, and then four of the students, three girls and one boy, gave their consent to be the future participants. In the blog-mediated writing class, they were informed to do their best to revise, reflect, read and comment. At the end of the study, individual portfolios were produced as a means of data collection for assessment. Two features differentiated these four participants from the other 12th graders of this high school. One feature is that these four participants came from the researcher’s regular English classes, categorized as social science classes. They were well.

(38) 26. acquainted with the teacher’s teaching style as the researcher had been their English teacher ever since they were in Grade 11. Likewise, the researcher had come to know their personality through the active interaction with them over the past year. The other one is that they had a stronger motivation to improve their writing skill, willing to get more involved in repeating more of the writing cycles in the writing class, though informed that lots of writing time and efforts were demanded in the syllabus.. 3.2 Instruments. 政 治 大 questionnaires on students’ writing attitude, 3) the class blog, 4) students’ 立. In this case study, the instruments we need include: 1) drafts on Topic 1 and 5, 2). self-reflection journals, 5) the teacher’s logs, 6) students’ portfolios, 7) self-evaluation. ‧ 國. 學. form on portfolio and questionnaire on the writing class, 8) CEEC scoring criteria. ‧. (Chang, 2004), 9) Yagelski’s coding schemes (1995), 10) Johnson’s indicators of. er. io. sit. y. Nat. content and organization (1994), and 11) semi-structured paired interviews.. 3.2.1 Drafts on Topics 1 and 5 as Pre-test and Post-test. al. n. v i n C hto be written in theUwriting class. The drafts on Topic 1 Five topics were assigned engchi. and Topic 5, serving as the pre-test and post-test respectively, were graded by two. raters, the researcher herself and another invited fellow English teacher with over 15 years of English teaching experience. The grading was to compare if there was any significant improvement on the part of students in content and organization, the two main indicative factors of process writing. Meanwhile, the drafts on Topic 2, 3 & 4 were seen as the part of practice in the training sessions of process writing. One thing deserves mentioning is the establishment of inter-rater credibility between the two raters. Before grading these drafts, the two raters scored ten writing samples to reach the consensus on the criteria of the evaluation. When disagreement happened, the two.

(39) 27. raters discussed until they reached an agreement. To measure the reliability, the scores on the ten writing samples were collected. Cronbach’s alpha reached 0.8 in the five categories of modified CEEC Scoring Criteria, indicating there was inter-rater reliability.. 3.2.2 Questionnaires on Students’ Writing Attitude (See Appendix A) At the beginning and the end of the course, the questionnaires on students’ writing attitude (Chang, 2002) were answered by students in order to investigate if participants experienced any attitude change. Collaboratively designed by Chang and. 政 治 大. Tsai (2002), the 36-item five points Likert-scale questionnaire standardizes the. 立. measurement of statements in four categories: confidence, anxiety, usefulness and. ‧ 國. 學. preference (see Appendix B, English version). To measure students’ responses more accurately, the statements of these items are randomly arranged rather than listed in. ‧. categories in case that these students answer the questions based on the perceived. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. ideas.. 3.2.3 The Class Blog (See Appendix C). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. According to Campbell (2003), three different types of blogs fit pedagogical purposes: the tutor blog, run by the class teacher; the learner blog, run by each student in the group individually; and the class blog, run by the teacher and students collaboratively. As 12th graders, these four participants did not seem to have much time managing individual learner blogs. The class blog was therefore selected to serve as the forum for them to document and publish their writing process. Established at www.blogger.com, provided by Google, the class blog, whose format and layout was managed by the teacher, offered the co-authoring function which allowed at most 100.

(40) 28. authors to post entries under their names. Two major reasons explained why the teacher favored the class blog over the learner blog. First, for the teacher and the four participants as well, it would be a hassle when clicking on to the web pages of individual learner blogs backwards and forwards. What’s more, by keeping all the entries in the class blog, it was more likely to establish a sense of learning community. Most important of all, registered under the teacher’s name, the class blog could be kept intact to function as the database of the present study.. 政 治 大 3.2.4 Students’ Self-reflection Journals 立. Self-reflection journals were chosen to replace Emig’s ‘composing aloud’. ‧ 國. 學. method (1971) for several reasons. Owing to the limited teaching hours and financial. ‧. support, it was very unlikely to practice Emig’s ‘composing aloud’ in this study. Most. sit. y. Nat. important of all, ‘composing aloud’ is also criticized as a “difficult, artificial, and at. io. er. times distracting procedure” (Voss, 1983), whereas many studies have stated the benefits of journal writing. As a means of reflection, learning journal helps to build up. al. n. v i n C h 1994) and document one’s own learning process (Carroll, the personal growth, engchi U. development and transformation (Diamond, 1991). Reflection is enhanced in the computer-mediated environment because students have an easy access to journals, with more time to read, re-read or compose thoughtful messages (Burge, 1993; Davie & Wells, 1991). In the present study, the self-reflection journal was considered a requisite as a means to document learners’ writing process, as a reference to make revision and as a source of data collection. After each peer review activity, these four participants were asked to write a self-reflection journal (see Appendix D), regarding the writing process and the suggestions from peers and the teacher. To encourage students to.

(41) 29. write more in a journal, the teacher suggested that they write their journals in paragraphs instead of Q & A form. A guideline to self-reflection journal was hence revised (See Appendix E) to contain the following information. 1) How does the brainstorming help? 2) Is there any difficulty in the writing process? 3) What’s the teacher’s feedback on the written draft? 4) Summary of the suggestions listed on the peer review sheet. 5) What do you feel about the topic?. 政 治 大 writing process in a journal can help these four participants spot their problems before 立. It is hoped that summarizing the teacher’s and peers’ feedbacks and reflecting the. making revisions. These participants were also encouraged to add in the journal. ‧ 國. 學. something related to English learning problems, personal feelings, and perception. Nat. io. er. 3.2.5 The Teacher’s Logs. sit. y. ‧. toward the teacher’s instruction.. To record how students developed the writing process, the teacher wrote logs. al. n. v i n C h observation on U after class, including the teacher’s individual participants, and engchi teacher-and-student interaction in class.. 3.2.6 Students’ Portfolios Over a period of time, in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, portfolios have long been recognized as a great tool to assess students’ performance (Council of Europe, 2006; Hamp-Lyons & Condon, 2000; Klenowski, 2002). For the teacher, portfolios can provide a panoramic view of students’ learning process. For students, it offers a good chance for them to reflect on how and what they have learned when compiling a portfolio..

數據

+7

Outline

Background & Motivation

Feedback (Peer Review and Teacher’s Feedback)…

Self-evaluation Form on Portfolio and Questionnaire on the

Writing Cycles

Research Question One

The Comparison of Usefulness among Peer Editing Sheets,

Research Question Two

Pedagogical Implications

Recommendations for Further Studies

Guideline to Self-reflection Journal

相關文件

泛指通識中 心所開之 xx 課群、語言 中心所開之 大一英文等 課程、軍訓 室之軍訓、..

泛指通識中 心所開之 xx 課群、語言 中心所開之 大一英文等 課程、軍訓 室之軍訓、..

中學中國語文科 小學中國語文科 中學英國語文科 小學英國語文科 中學數學科 小學數學科.

中國語文課程為各學習階 段提供「建議篇章」, 推薦 適合學生程度的文言經典作 品。. 教師可按學校情況,靈 活地把「建議篇章」融入課

為協助新來港非華語學生融入學校,教育局 資助啟動課程及適應課程,並為啟動課程畢

大學教育資助委員會資助大學及絕大部分專上院 校接納應用學習中文(非華語學生適用)的「達 標」

泛指通識中 心所開之 xx 課群、語言 中心所開之 大一英文等 課程、軍訓 室之軍訓、..

主頁 > 課程發展 > 學習領域 > 中國語文教育 > 中國語文教育- 教學 資源 > 中國語文(中學)-教學資源