Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents in U.S.A.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap

Attitudinal Differences Between High SchooI Students

and Their Parents in

U.

S. A.: A Case Study of Generation GapFrank Ping-yu Yen

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ...109 Themas and Issues in Generationa1

Stidues . . . .109 The C1assica1 Perspective ...109 Studies of the Y outh Movement . . . .111 Deve10pment and Refinement

of Generationa1 Theory ... .112 Generationa1 Gaps and

Y outh Adjustments .... - . . . .114 Eva1uation of Reported Rese

ar.

chStrategies ... .-. . . . .

., . .

.116 Behavior Rationa1e of the SemanticDifferentia1 Technique . . . .117

Dichotomies of Semantic Meanings ... .119 Sca1es and Semantic Components . . . .120 Semantic Differentia1 Technique

and Its Measurement Rationa1e ... .121

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28 Methodology for Separating Affect

and Denotation ... 126

Design of the Study ... 127

Rationa1e and Purposes

...,...

127Method and Strategies ... 129

Rationa1e for Statistica1 Techniques . . . .. 130

II. ISSUES OF OPINION DIFFERENCES BETWERN STUDENTS AND THEIR PARENTS . . . ., 137

Spbjects ... . . . .. 137

procedures . . . .. 137

Results . . . .. 138

Discussion ... 146

III. OPINION DIFFERENCES BETWEEN STUDENTS AND THEIR P ARENTS . . . " 151 Selection of Areas of Conf1ictua1 Opinions and Semantie Differentia1 Sca1es . . . ~ . . . .. 151

Subjects. . . .. 155

Procedures ... . . . .. 155

Subject Demographic Information . . . .. 155

Indigenous Group Factor Ana1yses of Concepts and Sca1es . . . .. . . 160

Ma1e students . . . 159

Fema1e Students . . . .‘. . . .171

Parents of Ma1e Students ... '. . . . 172

Parents of Fema1e Students ... 175

Cross-Group and Cross-Generationa1 Fåctor Comparisons . . . 178

Sca1e F actor Simi1arities . . . .. . . .. . . 1 79 ConceptF actor Simi1arities ...;... 180

Dìscussion ... 180

IV. DYNAMICS OF GENERATIONAL GAPS ... 187

Method. . . 187

Subjects ~ . . '. . . . 187

Procedures . .'. . .. . . . 187

At吋t衍it叫udi.切n切叫al D歧〈叮汀伊er,陀en肘ce,臼sBetween High S卸CJ加t的θ01Students and

η1眩ei什r Pav,均P管切'ent衍s i的n U..丘A.:A Case Stz似JdyofGenera 白tion Gap

Results and Discussion . . . .. 187

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS .. . . ., 197

On Theorizing of Generation Gaps . . . .. 197

On the Metho吐 ofData Ana1ysis ... 198

On Solutions and Implications of the Present Research ... 200

REFERENCES . . . .. 202

APPENDIX A Open-endeιquestionnaire ...'.... 206

APPENDIX B Questionnaire With Standard Semantic Differentia1 Ratings ... 208

APPENDIX C 1. Ma1e-students' Factor Loadings of Sca1es . . . .. 214

2. Two Dimensiona1 Plots of F actor Loadings ... 215

LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. Examples of Pan-Cu1tura1 E-P-A . . . .. 125

2. Summary of Elicited Attitudina1 Differences Between Generations . . . '. . . . 139-144 3. Summary of Proportiona1 Differences in Opinion Responses . . . • 147個 148 4. Eighteen Concepts of Opinion Discrepancies ... . . . 152

5. Twenty Nine Semantic Differentia1 Sca1es

,... . . . • . . .

1546. Marita1 Status of Parents ...的 7 7. Acge of Students ... . . . 158

8. Who Has Influenced Students' Opinion Most . . . ; . . . . .158

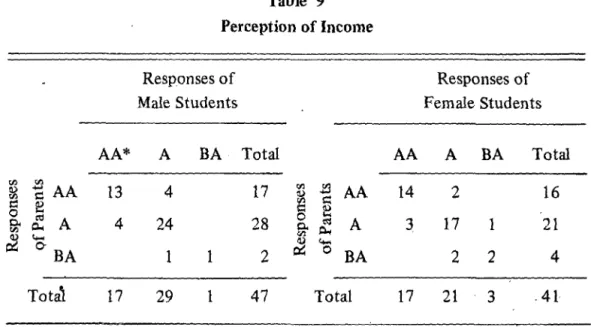

9. Perception of Income . . .

, . . .

.160 10. First Fifteen Latent Roots of Cross-ProductMatrices ... . . . ; . . . " 161-164 日. Sa1ient Variables and Loadings for

Ma1e Students . . . .. 166-167 12. Sa1ient Variables and Loadings for

Fema1e Studertts . . . .、...

...

.168個 170 13. s.a1ient Variables and Loadings forParents of Ma1e Students. . . 173-174

Bulletin 01 National Taiwdn Normal University No. 28 14. Salient Variables and Loadipgs for

Parents of Female Students ... 176-177 15. Cross-Generationa1 scale Factors ... .179 16. Cross-Generationa1 Concept Factors . . . .. . . .181 17. Sa1ient Subject Factor Coefficients ... .182 18. Rotated Core Matrix for Ma1e Students . . . 183-184 19. Unidimensiona1 Variables . . . ." . . . .. 189 20. Summary Statistics of 16 Unidimensiona1

Variables ... 190 21. Prediction of Perceived Generation Gaps

Within the Fami1y . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . 192 22. Prediction of Perceived Generational

Figure

Distances on Opinions ... 194

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Schematic Representation of the Development of Conceptions

2. The Three-mode Cube of Semantic Differentia1 Data

Attitudinal Digkrmces BEtween HIgh School Studenfs and Their Parents

iñ

U.S.A.:A Case Study ofGeneration GapCHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

The question of generation discrepancies is a socia1 issue as old as mankind's earliest writings and as contemporary as current jouma1 artic1es. In the literature there are a large number of studies on the phenomenon of societa1 changes and their influences on youth attitudes, adjustments and behavioral pattems. Various theories and recommendations have been provided to account for the so-ca11ed generation gap problem. However the difficu1ties of inter-generationa1 com-munications and adjustments are still persistent in the contemporary society. Despite the fact that other areas of teac趾ng and educationa1 faci1ities and program have effectively achieved to a very successfu1 level during the past decade

,

adjustment problems among youth continue to be one of the major and institutiona1 tasks. Therefore,

in order to develop a more constructive and effective prog;ram,

re-eva1uation of the whole issue seems necessary. The present research is thus an intensive case study of generation gaps within a relatively homogeneous subject population. While Osgood's representationa1 theory of human Ieaming and cognition will be used 倒 the basic theoretica1 framework,

Tzeng'sl research strategies wi11 be used as the major measurement guide.In this chapter, the 1iterature on the contemporary issues of so-called genera-. tion gaps between school students. and their parents will first be reviewed with the focuses of three broad areas: (i) historica1 prospective of the issue of gene ra:-tion gaps, (且) areas of diffic叫ties and adjustment problems reported. in this changing society, and (iii) sources and dynamics of generation gaps. After eva1 ua-tion of genera1 theories and methods used in most studies of generation gaps, Osgood's2 representation mediation theory and his semantic differentia1 measur e-ment technique will then be summarized for the develope-ment of the present research designs and methods.

Themes and Issues in Generational Studies

The history of generationa1 studies can be traced through three progressive stages as follows (Bengtson et a1,3):

(1) The Classica1 Perspective

This is the initia1 development of competing formulations focusing on the

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

impact of youth groups on social structure by social historians and modem sociologists. Social theorists such as August Comte4 and John Stuart Mi11s have utilized the concept of

“

generation" in their efforts to explain historical changes and the rise of particular political movements. More recently, several developments on generations have been made:(A) Historical consciousness of age-groups. Mannheim6 developed the notion of historica1 consciousness and social organization as manifest in emerging genera-tions. For him the concept of generations represented a unique type of social location - one aspect of differentiation in a society 一 based on the dynamic interplay of demographic facts which inevitably create an age cohort, and social meaning (the conscìousness of that cohort's peculiar location in history, arising from decisive political or social events). The concept of generation thus serves as the crucial 1ink between time and social structure and is important in under-standing the progress of historical èvents and the course of social cham1;e.

(B) Structural-functional explanations of youth culture. Parsons7 and

Eisenstadt8 attempted to assess.more precisely how generations operate as

dimen-sions of social structure, that is, how age groups reflect strain and imbalance în the social Or~r and, by implication, how differentiations within age groups occur. According to Eisensta缸, the dynamics of generational phenomena can be traced to the interplay between technological development and the division of labor in complex societies. From the functionalist perspective, some degree of generational conflict inevitably 缸ises from differences in stages of personality development between age groups and from cöntrasts in social positions between younger and older members of society. Such differences are not necessarily reflective of permanent value differences or discontinuity between generations, nor are they symptomatic of social disorganization. Rather, generational contrasts reflect the attempt of youth to adapt and to prepare for their entrance into adult roles as they ~ucceed the parent generation (Parsons & Platt9

).

(c) Assessments of generational conflict and transmission. While the historical-consciousness and structura1-functional pèrspectives on the problem of generations are primarily macrosocietal conceptualization, the third perspective is m

Attitudinal Di方卸的lcesBetween High School Students and Their Parents in U.SA.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap 11 Coleman 12 and Cain 13 have emphasized social and psycho10gical research upon youth and inter-age contrasts as important dimensions of social organiza-tion. In varying ways, each attempted to use theore1ical foundations to explain the unique situation, role, and character of age groups in the post-Wor1d W缸 II era.

In summary, the c1assical period of generationa1 ana1ysis in modern socia1 science was marked by the deve10pment of competing formu1ations regarding the impact of youth groups on socia1 structures and changes.

(2) Studies of the Youth Movement

This stage refers 10 the period after the sudden appe訂ance of student movements in the 1960s. Among students of socia1 issues

,

socia1 movements,

and socia1 change the protest movement caused a reviva1 of interest in the con-cept of generations. Many socia1 scientists carried out research in an attempt to identify the sources of student activism (Flacks,的 Altbach and Laufer,15 Lipset and Ladd 16). About the same 1ime, many socio1ogists (such as Roszak,17 Simmons ar:d Winograd,18 Suchman 19) had focused on the development of the countercu1ture with its exotic innovations and life-styles in order to chart the course of socia1 change as the many elemen1s of the counterculture. From this wave of generationa1 research, three stereotypic perspectives were. readi1y dis-cemable (Bengtson20). The first focused on generationa1 discontinuity which

has been ca11ed a great gap orienta1ion. During the 1960s, traditiona1 socia1ization processes had become dysfuncti.ona1 in an age of rapid socia1 change, often exacerbated by the apparent hypocrisy of the parenta1 generation. The result was discontinuities in basic core value between youth and 'their elders {Frieden-berg,21,22 Mead,23 Laufer and Light24). This Qrientation suggests basic, and in some sense, irreconci1able differences between age groups in American society, culminating in rapid cuítura1 transformation. Slater25 suggested we had a1ready become a nation of two cultures defined main1y by age distinctions.

The second group of researchers

,

inc1uding such scientists as Douvan and Adelson,26 C訂npbell,的 Walsh,28 Y ankelovich, 29 indicated that the reported generationa1 differences were rea11y an illusion; that the socia1 events of the 1960s were not based in va1ue discontinuties between the generations,

but rather represented socia1 change precipitated by other conditions. As youth matures into adulthood,

one may anticipate a reaffmnation of the basic continuity that exists between the generations in the structure of socia1 institutions.Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal Unive1'ffty No. 28

The third thesis elucidated that the nature 01" the student activism of the 1960s may be tenned selective continuity (Benedict,30 H凹 3 1. 32 Thomas33). That. 函, despite the apparent discontinuity between protesting youth and their parents, there was a great dea1 of familiar simi1arity in va1ues and opinions between generations. Therefore, the youth-based socia1 movement of the 1960s was not so much a function of generationa1 discontinuity

,

as a reflection of the developmenta1 concerns of youth,

bur rather accepting many of the orientations of their parents in response to new events,

they modify others andabandon a few. The three positions just reviewed 一 great gap, nothing rea1ly new, and selective continliity - reflect a debate that continues to characterize ana1yses concerning innovations of the unprecedented youth movement. Even though the reviva1 of interest in generationa1 ana1ysis in the 1960s produced numerolis studies, and a great dea1 of public awareness, no c1ear answer to socia1-psychological questions regarding the causes and our understanding of genera-tiona1 dynamics has been provided.

(3) Development and Refinement of Generational Theory

The third stage of generationa1 ana1ysis is currently being consolidated in sociology and psychology. A growing body of empirica1 data has been obtained on a variety of specific behaviora1 issues (re1igious behavior, drugs, educationa1 and occupationa1 aspirations, emergent cultura1 themes, the

“

freak" life style, political behavior and ideology) and a true life-span perspective that considers the generationa1 imp1ications of severa1 age groups.There are five major themes that characterize the current concerns of generationa1 analysis:

(A) Definition of generational units. The centra1 issues are concerned with conceptua1 relationship among time, aging and social changes. Attempts have been made to provide a socia1-psychologica1 viewpoint on the issues and variables involved in the identification of generationa1 differences. In genera1, the empirica1 research has focused on the examination of generationa1 phenomenon with respect to a macro (age-cohorO level or a micro (family lineage) level (Connell,34

Bengtson and Black,35 J ennings36 ). Many of the apparent disagreements that have characterized generationa1 ana1ysis in the p品t decade can be traced to such questions 部: Is it a

“

cohort gap" or a“

lineage gap"? and What are the relative importance of cohort and lineage simi1arities and differences in accounting for broader patterns of societal change?Atti﹒的 dinalDifferences Between High School Students and Their Parents 的 U. S.A .:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap (B) Continuity and discontinuity between age groups. The central component of generational ana1ysis is the extent of similarity and conflict between age groups in behaviors and standards of behaviors.τne issue involves analysis of socia1ization or transmission from elders to youth, as well as the degree of feedback as youth socialize their elders. (Aldous and Hi11,37 Keniston, 38 Riley et al. 39) Many studies on simi1arities and 吐ifferencesbetween generations

at either the cohort or lineage level are analyzed in tcrms of drug use

,

religious beliefs and behaviors,

political orientation,

and attitudes toward nuc1ear wars. (C) Duration of generational units. This is concerned with the question whether contrasts between generations evident in a particular year or decade oor關揖 changes that wil1 characterize a longer period of cultura1 history,

or whether 位le differences are merely reflective of the socia1 and psychologica1 immaturity of youth. The centra1 issue in the study of generations is therefore the .relative role played by generationa1 units (or group consciousness) and maturation in the dynamics of generationa1 differences.(D) ~nerationa1 solidarity. 'TI1Ís issue involves the degree of interpenetration and commonality among generationa1 units. In part this reflects the degree of distinctiveness of the emergent cohort, and in part it reflects the homogeneity of experiences and outlook within the cohort. The impact of ybuth cohort solidarity on society

,

the nature of the socia1 cltange it effects,

alîd the growth of its impact by dissemination to other segments of society are topics which wil1 receive consi臼rableattention in coming years.(E) Generations and other dimensÎons of social structure. This involves the functiona1 relationships between generational dynamics and the issue of socia1 organization: the interaction of age or age-consciousness with other dimen-sions of social differentiation. Severa1 issues frequently stand out in the literature

,

inc1uding the effect of rate of socia1 change on generationa1 development, technologica1 innovations and the relations between generations, mass media influences on generationa1 dynamics (Hayakawa40), the age structure of society as manifest in demographic characteristics, roles, and socia1 c1ass.

Due to the complexity of factors relevant to any characterization of socia1 changes or stabi1ity

,

the preceding review suggests thaBulletin o[ National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

in the next section of this chapter an effort will be made to review the reported problems of youth adjustmetlts and their sources. In order to assess the genera1 research findings, the theory and method in the reported studies of generation gaps will a1so be eva1uated. An a1temative research rationa1e and methodology -the semantic differentia1 - will fina11y be presented.

Generationa1 Gaps and Y outh Adjustments

In the 1iterature

,

many empirica1 studies have been reported on the chara c-teristics of youth in relation to socia1 changes and institutions. The so-ca11ed generationa1 gap has been regarded as existing between today's older and younger people with respect to students' mora1s, attitudes, ethics, va1ues and other con-temporary socia1 issues (Buys,42 Lemer et al. 43.44). These discrepancies havebeen regarded as associated with such behaviors as drug abuse and socia1 rebel1ion by the young (B1um,45 Goode,46 and Ramsey47). However, in most of the

reported studies, the domain and relevancy of the issues such as war, sexua1ity, racism

,

were usua11y defined subjectively by the researchers. Issues on which significant differences may exist 、 between the two generations may not readily be inferred as the rea1 gaps that contribute to the behaviora1 dynamics of the present younger generation (Tzeng and D卸lit48). This imp1ies that on1y the conf1icting issues with highest psychologica1 significance to the young will have greater influence, or more correlates, in determining their behaviora1 pattems and intentions.

In order t<) assess empirica11y for a group of college students the actua1 issue domain of generationa1 disagreements, Tzeng and Dimit49 used a natura1 e1icitation procedure to obtain a 1ist of items (areas) from college students of both sexes to represent .what they considered the most significant differences of opinion they had with their p訂ents. A total of 89 items were e1icited and grouped into 11 categories according to their relative frequencies as follows: 1. Dating (with dominant items premarita1 sexua1 relationship and

selec-tion of dates)

2. Chemica1 substances and related behaviors (us扭g drugs, drinking and smoking both cigarette and marijuana)

3. MQney related issues (materia1ism and cars)

4. Individua1 appe缸ance(main1y hair length

,

dress and facia1 h泊。 5. Genera11ife pattems (re1igion, mora1s, 1ife styles and g.oa1s)6. Socia1 values and po1itica1 issues (po1itica1 issues, racia1 and religious

Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents in U.S.A.!A Case Study ofGeneration Gap prejudice, women's rights, changes in society, personal roles in social institutions)

7. Pastime activities (music, entertainment, late hours and travel)

8. Interpersonal relationship (friends of the same sex, friends of a ζifferent race

,

religion,

nationality and sexua1 beliefs)9. Education‘ and career planning (perception of a good job, significance of education, grades and choice of own career)

10. Marriage and fami1y (child-rearing, birth control and abortion, marriage, teen-age pregnancies)

11. Housing (coed housing, unmarried couples 1iving together, value of fraternity and sorority, university living and living away from home rJter school)

These reported discrepancies between college students and their parents are genera11y concerned with self (ego orientation), to others (inter-personal relationships)

,

and to society (socia1-economica1 aspects). Sex differences on some areas were a1so evident: for the ma1es, the differences were mainly concerned with students as individua1s; for the fema1es, the issues involved the current progress of women's equal participation in socia1 and politica1 functions. According to Tzeng and Dim泣, since these data are perceived areas of generatiori gaps as only reported by students, cross-validation from the parents should be made in order to establish common ground responses. As reviewed earlier, many observations on potential sources, behavioral dynamics, and correlates of the growth of generation gaps have been reported in the literature. The most important one seems to be rapid social transformation and depersona1ization, as the result of great achievements in technology and science.50 However, verylittle empirical research has been reported about the development of a theoretical framework or psychological explanation of the so-ca11ed generation gap. Tzeng and Dimit,51 however, attempt to investigate 位ÙS problem area by comparing

the respor.:se characteristics of 20 self-related variables between thirty college female students and their parents. The results indicated that there were some large generationa1 discrepancies in the implicit va1ue systems and psychologica1 connotations of social an丘 environmenta1 institutions, inc1uding such items 臼

persona1 politica1 persuations, rock music, personal attitude toward socia1 politica1 system in this country and the belief as to whose opinions (between paren

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

college female students

,

Tzeng and Dimit obtained factorial structures of the same 20 measurement variables for the two generations. The characteristics and hierarchical order of the first three factors for the p訂ents group is: (1) complete ego-centra1ization of happy life, (2) association with peers and immediate living environment, and (3) materia1istic (money) and emotiona1 (children's conformity) security. The remaining factors. are more remote from the necess缸y persona1 surviva1 and identify; and are in order: (4) attitude toward socia1/political institutions,

(5) persona1 pastime activities,

and (6) entertainmerit. These kinds of psychologica1 structures (factors) seems to reflect the adults' individua1ity with respect to the persona1 standing 扭 the near living environment. But for fema1e students,

the factor structures were reported to reflect a group-oriented pattern of personal standing among the peers. Their self-perceptions,

entertain:-ment,

relationships with c10se opposite-sex friends,

attitude toward money,

and general emotional stabi1ity are c10sely related with socia1 institutions and peers. However,

the conformity to p缸ents was a1so reported as playing art important role in chi1dren's level of ego satisfaction. The potentia1 adjustment difficulty for the youth will definitely arise when the peer pressures and the desire of parental conformity are not congruent. No empirica1 studies have been reported in the literature as to whether these findings would suggest the cohort solidarity among high school students and college fema1es, however.Evaluation of Reported Research Strategies

In the literature

,

numerous artic1es have been published which dea1t with the problems of the so-called generational gaps. However, no unive_rsally agree-able conc1usions have been reached for identification of the precise 訂e品 anddegrees of generationa1 gaps which have significant determining effects on culture changes. This is probably due to the fact that many reported findings were based on 扭ferences from possibly biased subjective observations and/or empirica1 research. As Tzeng and DimitS2 pointed out, subjective selection of research issues or domains such as politics

,

va1ues,

sex,

drugs,

future career planning,

could not gaurantee the relevancy of issues in attributing to the behaviora1 dynamics of the present younger generation. Methodolo斟cally, most reported studies used on1y simple statistical comparisons (i.e~, differences in percentages or in group means) on responses of various predefined questions. Therefore, functiona1 relationships among variables were frequently integrated by subjective inferences or simple correlation ana1ysis (or its equiva1ent f<?n吼叫.ch as pathAttitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents in U.S.A.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap analysis). All this implies that if one wants to conduct a sophisticated empirical research in this area, the following considerations should be made: (1) Areas of generationa1 discrepancies should be directly obtained from the subject popula-tion (both youth and parents). This will insure the content validity of the research variable 吐omain and thus maximize the construct va1idity of later reseaτch solutions. Tzeng and Dimit'sS3 naturalistic procedure of e1iciting conflictua1 issues directly from subject population wi1l thus be used as the mode1 for the present research. (2) Measurement to01s used in the research shou1d be ab1e to reflect boíh the areas and degree of generationa1 differences. The within-and between-generationa1 sirni1arities and differences in un丘erlying psychologica1 frameworks for perceiving the conflicting issues should a1so be maxima11y accounted for. This suggests that in an idea1 research situation one shóu1d apply a research methodology that cou1d investigate the human cognitive structures and their influences in human perceptions an吐 judgements. In this respect

,

the semantic differentia1 technique and its rationa1e,

as reviewed in the next section,

will be used as the main measurement instrument in this research.

Behavioral Rationale of the Semantic Differential Technique

According to TzengS4 the process of human perceiving and judging involves three major variables: unique characteristics of the individuals making the judg-ments, characteristicsof the objects (things or persons) being judged, and the criteria (or meaning systems) peop1e use. Meanings of objects a1ways represent different experiences of the individua1 organism in interaction with the environ閏 ment (inc1uding other humans). The meanings of the same objects for different individua1s wi11 vary to the extent that their experiences and behaviors toward the objects have varied. This imp1ies that meanings of objects will reflect the 甜iosyncrasies 01 individual leaming experiences. Since one or the most irnportant factors in socia1 activity is meaning and change in meaning - whether it is tenned “opinion",“va1ue",“attitude", or something else, measurement of meaning has therefore bofh practica1 and theoretica1 significance in the socia1 sciences.

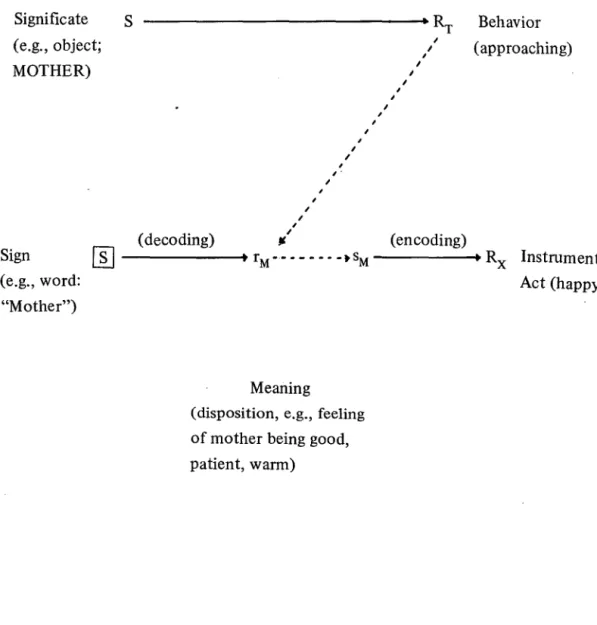

As to the question of what kind of meaning is being referred to, is it measur-able? According to OsgoodS5 it is the.semantic meaning which is defined as the ur:.derlying psychological relation between signs (e.g門 the word

“

móther") and 也eir significates (the object MOTHERS). Osgood developed a representationa1 mediation theory in his book, Method and Theory in Experimental PsychologyBulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28 Significate (e.g., object; MOTHER) Sign

囝

(e.g., word:“

Mother") S'

, (decoding) ,區'

',

',

''

,

',

trM---tSM Meaning(disposition, e.g., feeling of mother being good, patient, warm)

'

,,

'

,

' , .. RT Behavior'

,

'

( approaching) (encoding) • RX Instrumenta1 Act (happy)Figure 1: Schematic representation of the development of conceptions (this figure is from Tzeng56).

Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents in U.正A.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap as a behavioral model in general and theory of meaning in particular

,

within the stimulus-response, association paradigm, as shown in Figure 1.In this model, the signs and significates are related via the theoretical con-structs called

“

representational mediator" (rm

一- sM) which are derived from the behavior (RT) e1icited by significates. For example, a chi1d tends to approachhis mother, who has been very good, warm, and patient to him, whenever he sees her. After the chi1d has learned the word

“

mother",

he 社eve10pspsychological dispositions toward conceiving MOTHER as being very good, warm and patient trom these experiences with his own mother. These dispositions are identified as“

meanings" of the concept“

mother". They are representational because they represent part of the extemal experience (RT) produced by the significate itself (MOTHER). They are also mediational because the meanings are usually associated with a vadety of instmmental acts(RX, for example,

feeling of happiness when the chi1d sees his MOTHER). In this variation from usual S-R paradigms, Osgood has divided the process of the stimulus戶response into two stages. The first stage, called“

decoding", is the association of signs with mediator components (rM) or features (the semantic "co.de 刊), and therefore this stage is the“

understanding" of objects or significates. The secon吐 stage, called“

encoding", is the association of the same mediation processes, now as internal st加u1i (sM) or“

intentions", with overt instrumental or linguistic behavior, thus the“

expression" of ideas.Dichotomies of Semantic Meanings

Due to different processes in formulating psychological dispositions, meanings of objects have further been dichotomized into two aspects - affective and non-affective.57 The reason is that it is crucial for the human animal,品 well as other higher organisms, to make different emotional (autonomic) reactions to distinguish among the signs of things as being good or bad (Evaluation.) strong or weak (Potency) an已 active or passive (Activity) with respect to himself when confronting any behavioral decision (or judgment) situation. These distinguishing processes reflect a person's attitude or feelings about an object. They are pri-marily emotional in nature, and thus the meaning of this type is affective. 58

When meanings of signs are established to characterize objects or events referentially, they reflect a person's implicit judgments or descriptive criteria about the object. The criteria include various conceptual categories, such 品

grouping, contrast, simi1ari旬, and classification. In description of persons, for

Bulletin 01 National Taiwan Normdl University No. 28

example

,

such terms as sophisticated-naive,

predictable-unpredictable may be used. The meaning from this abstract structure of signs can be defined as non-affective (or denotative) meaning.59Typical1y these two meaning systems - affective and non-affective - are simultaneously involved in human perceptua1 and judgmenta1 situations. Affective meaning systems play a dominant role. Measurement of these two aspectsof me扭曲g 扭 relation to individua1 and object variables are basic to the socia1 behaviora1 sciences.

Scales and Semantic Components

The meaning of a sign (i.e., a concept) can be characterized by qua1ifiers or adjectives. These qua1ifiers (they wil1 be referred to 倡“sca1es") 缸e “different" 加 reference to different psychologica1 criteria (or areas). This is because the meanings of an object are componential in nature - consisting of a number of different (both affective and non-affective) semantic features' of psychologica1 criteria. Therefore

,

üsgood60 defined meanings 品 a simultaneous bundle o[ distinctive semantic [eatures or components.Each feature or component can be represented by a number of simi1ar scales which connote the same meanings in a particular context and for a p缸a

ticular group of persons. For example, in judgment of persona1ities, we may use such sca1es 品 good (bad), nice (awful), warm (cold), and honest (dishonest) to mean one 訂'ea (component) of character

,

and use strong (weak),

powerful (powerless) and dominant (submissive) to mean another 缸ea.üsgood61 states that semantic components have three basic characteristics:

(1) Bi-polar organization: meanings of an object are differentiated ìn terms of polar oppositions of components

,

and each component is defined by a number of pairs of bi-polar adjectives. (2) A ttribution o[ positiveness to one o[ the poles o[ each semantic component: the positive" poles such 品 strong and active are somehow psychologica11y þositive, 1ike good, as compared with their opposites, weak and passive. (3) A tendency toward parallel polarity among scales: bi-polar sca1es representing diverse semantic components tend to be related in p缸allel, positive with positives and negatives with negativ~s, rather than 扭 contrary directions,

thus good AND strong,

but good BUT weak.Under the above circumstances a group of perceived objects or verba1 signs can be measured by a group of bipolar adjective sca1es from which we can identify (1) the semantic components (or dimensions) which are relevant foÌ' the entire

-Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents

tiz

U.SA.:A Case Study of Generation Gap set of objects, and (2) the degree to which each object or sign is re1ated to each semantic component.The Semantic Differential Technique and Its Measurement Rationale

In order to measure the meanings of objects and linguistic signs (concepts), Osgood et al.62 has developed a quantitative methodology, called the Semantic Differential (hereafter abreviated SD) technique. He called it

“

semantic" because it is supposed to measure aspects of meaning, and“

differentia1" because the technique provides differential results in terms of dimensions of meaning. The basic measurement assumption of the SD is that the objects or concepts under study can be represented geometrically by points in a multidimensional meaning space which can be accounted for by a given number of significant semantic features.Based on the properties of the vector space in a right-angle coordinate system, the semantic differentia1 technique makes the following analogies:

(1) There is a scale vector space, called the,senamtic space in human

cogni-tions, which consists of a number of meaning dimensions.

(2) The axes are considered to be independent semantic components which are the criteria used in human judgment.

(3) The origin of the vector space is defined as complete

“

menainglessness" 。rirrelevance (neutrality) of all components to objects under study.(4) The meaning of any object (or concept) is considered as a point in this N-dimensional semantic space and can be represented by a vector from the origin to that point.

(5) The length of the vector is an index of the

“

degree of meaningfulness" of this object.(6) Different projections of each object onto various dimensions represent different degrees of intensity - positive

,

neutral or negative - of the object in association with different semantic components.In short

,

the purpose of the SD is to identify the relationshlp between objects (or concept) and their semantic components in a multidimensional meaning space. Given the information on two objects (or concepts),

sjmi1arities and differences of their meanmgs can therefore be differentlated by means of their relative relationships with mea:ning components i11 the space.Following the above theore1:ica1 development, the SD model covers two

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

steps 凶 measurement: (1) 的 identify psychological semantic dimensions as axes 的 the semantic space, and (2) to meωure the meanings of objects with respect to these semantic components. While the first step is the procedure of developing the SD rating sca1es, the second step is the application of the SD in various context areas.

Since semantic components are not directly observable, they must be “dis戶 covered" from eva1uation of inter-relationships among sca1e vectors in the semantic space. This discovery procedure inc1udes the following three steps:

(1) To obtain a representative sample of bi-polar sca1es Wihich are actua11y

used in judgments of a given object domain; (2) to construct inter-sc~e correla-tions in a semantic space based on their characterizacorrela-tions of usage for the objects being judged

,

and (3) to identify (discover) different natura1 c1usterings of these vector sca1es to represent various hypothetica1 constructs (or components) of human conceptions. This procedure has been used by Osgood and his associates 詛 cross-cultura1research and can described as follows:From a representative sample of 100 diverse concepts (inc1uding abstract tenns, such as SUCCESS, POWER, and HOPE, as well as concrete tenns, such 品 BIRD

,

DOCTOR and HOUSE) which have no translation difficu1ty in various communities, a large sample of verba1 qua1ifiers (adjectives, such as good, hard, long, tender, sharp, etc.) were elicited from high school ma1e students in some 25 language/culture communities around the wor1d. This is ca11ed the natura1istic elicitations procedure. Each subject was asked to give an adjective as his response in describing each of the 100 nouns.A tota1 of 50 qua1ifiers and their opposites were selected, based on their high productivity (high association with the 100 tenns across a11 subjects 一位ley

are produced from a large number of tenns by a large number of subjects) and independence (1ow interrelationship among adjectives with respect to both the 100 tenns and a11 subjects). These qua1ifiers and their opposites were used to construct the SD bi-polar sca1es for ratings of the same 100 tenns by new samples of the same high school ma1e student popu1ation in a11 language/cu1ture com-munities involved. These sca1es presumably represent the entire common cri-teria (i此, meaning vectors in the semantic space ) used 扭 thejudgments of the

100 representative concept

Attitudinal Di.佇'erencesBetween High School Students and Their Parents 的 U.SA.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap at the origÏn of the semantic space, representing neutra1ity of the qua1ity. The position 1 or -1 is designated as

“

slightly", the position 2 or -2“

quite" and position 3 or -3“

very". These particular quantifiers have been shown to yield approximately equa1 degrees of intensity of meaning. 1n a typica1 SD task, the concept (object) is rated against a set of bi-polar sca1es as follows:MOTHER

good bad

+3 +2 +1

。

-2 一3One of the spaces is checked to indicate a respondent's judgment on the continuum. For example, when most people rate MOTHER +3, they are creating a little sentence which says Mothers are very good. A11 of the

“

sentences" on the SD form have this same structure - substantive (be) quαntifier qualifier - but the substantives (concepts),

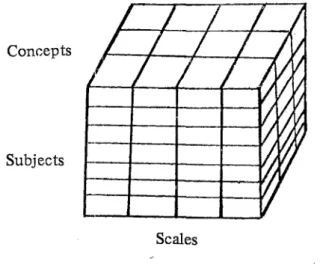

qua1ifiers (adjective pairs) and poles of the adjective (1eft-right ordering of pairs) are randomly ordered in the booklet.Within each cu1ture, a sample of people rated a set of concepts against the 50 selected sca1es. A cube of data was generat~d , as displayed schematica11y 旭 Figure 2. The rows of the cube represent the subjects doing the ratings, the columns represent the sca1es, and the slices, front to back, represent the sub-stantive concepts being judged. Each cel1 contains a single va1ue from +3 through

o

to -3, to represent how a particular subject rated a particular concept against a given sca1e.Concepts

Subjects

Sca1es

Figure 2: The three-mode cube of semantic differentia1 data.

Bulletin 01 National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

Given such three-mode data for each culture

,

the degree of semantic similarity among descriptive scales can be indexed by their degree of similarity in usage across al1 subjects and concepts. Conceptual1y, this is to obttain inter-correlations among the 50 scales, computed across the other two data mοdes(subjects and concepts)

,

in a semantic space with each sca1e as a vector. These inter-sca1e correlations were then used as input to solve for natura1 clusters ofal1 scale vectors. Statistica1ly, this is to identify

“

discover" various independentc1usters of vectors as different axes (ca1led factors) which are orthogona1 to each other and can account for the entire semantic scale vector space. The dimension-ality of the semantic space is therefore the number of independent vector c1usters 扭 thespace.

To implement the above pu中ose, a statistica1 method known as

“

pan-Iculturalfactorization弋 (for

details see Osgood,

et àl. 63) was applied to thecrosscu1tura1 intersca1e correlations (each culture's 50 sca1es were correlated with reach other cultures' sca1es across indigerious group mean ratings of the 100 t要rms)

among some 25 cultures. Conceptua1ly factor ana1ysis starts from input of inter-correlations (or their equiva1ent forms) among variables, and solves for (1) factors of the semantic space and (2) projections of al1 vectors (variables) on the resu1tant dimensions in a final factor loading matrix. Psychologica1 characteristics of each dimension (each column of the factor loading matrix) can be determined and labelled by common properties of defining vectors (variables as rows of the factor loading matrix) which have uniquely high projections on the dimension, but very low on al1 other dimensions. Three cross-culturally common and independent (orthogona1) factors were obtained from the pan-cultura1 factor analysis and identified as Evaluation

,

Potency and Activity. For each cu1ture,

four indegenous sca1es which have .the highest and purest (uniquely high) projections on each of these three semantic components were selected as shown in Table 1. Since the three under1ying dimensions appeared to be on the way humans attribute more primitive emotiona1 fee1ings (rather than sensory discrimination) towards persons and 甘ùngs 扭 their environments,

they constitute an affective (or connotative) meaning system.A11 sca1es in Table 1 were defined as “markers" for their respective d卸len sions

,

and 也ey are fuTable 1

Examples of Pan-Cultural E-P-A Markers*

Semantic Feature aLM TA U -MY

U-u

cn

',',門 u mv 前 泊 m mE-o mE T-心 Activity AE (American/Eng1ish) -mNH| quick/slow active/passive impetuous/q叫et strong/weak big/smal1 deep/shallow good/bad magnificent/horrible beautiful/ugly BF (Belgium/Flemish) fickle/serious soft/hard s曲n/thick wet/dry strong/weak big/smal1 heavy/1ight strong/Lrnperfect glad, happy / angrygood/bad nectar-like/poisonous useful/h剖mful DH (De1hi/Hindi) 、§包 含 d U 泣 ,有::1 c) :::!"-l:::

‘_

N ~;::: ‘一 U c5 s;::26

函、言, :真令 泛泛 泛~ 也包 屯J ;:;‘ 主 G Q有可有 跡。. 忠、電 S::~ ~::i F乏足 L 、忌。 "可 H 芯 S s::長 噎 t己 已.些2 "-l::: <ù 司自 fast/slow a1ive/dead young/old noisy / quiet Potency big/little powerful/powerless strong/weak deep/shal1ow Eva1uation nice/awful good/bad sweet/sour helpful/unhelpful* All sca1e markers from non-English cuItures in this table are here translated into Eng1i品, but they were actua11y in their respective native languages in al1 procedures of data collection at"l丘 ana1yses. This table is from Osgood, May, & Miron, Cross cultural universality of affective meaning systems.

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

measuring the affective meanings of the same .concepts across different language/ culture cQmmunities.

The SD technique has also been app1ied by Osgood and his associates (for details see Osgood, Suci and Tannenbaum,64 and Snyder ánd Osgood6 5) to

various types of subjects (of different ages

,

education,

IQ levels,

political affi1i a-tions, and even normals vs. schizophrenics) with different samplings of scales and of concepts, and even different methods of factoring, these three dominant and independent factors have kept reappearing. The universality of affective meaning - E, P, and A - is generally regarded as psychological reality by SD practitioners around the wor1d.Methodology for Separating Affect and Denotation

Tzeng66 and Tzeng and May67 have 缸伊ed that

,

in the judgment of a set ofmore homogeneous concepts(e.g.

,

al1 relating to persona1ities 品 drugs) on S D-type scales, the "affective meaning space can be seþarated from the remaining f actor structure by, using 也e “m訂kers" of the Osgood pan-cu1tural E, P, and Adimensions as control traits." The structure of the denotative meaning system can then be analyzed independent1y. The simu1taneous influences of affective and denotative meaning components on each scale can also be differentiated. As Osgood的 pointed out a decade ago, development of a rigorous method for such a simultaneous and differential identification is one of the most important pro-blems for contemporary psychosemantics.

Tzeng69 has developed a quantitative method for s伸arating the semantic

space. In essence

,

the method can be summarized as follows: Partition the ini1tial scale factor matrix of the persona1ity ratings into two subdomain matrices - the marker domain (the E-P-A marker scales on factors) and the non-marker domain (other scales on factors). After a sequence of ttansformations, the resultant factor matrix is divided 詛to four quadrants: Qll, the pancu1tural marker-scale loadings in the affective space (from which the purity of these markers when functioning in the homogenous persona1ity domain can be determined); Q21 , the non-marker-scale loadings in" the Affective space; Q 口, the loadings of E-P-A marker scales ∞ factors in the Denotative space (which should be near zero), andQ妞, the loadings of non-marker sca1es in the Denotative space (from which thè semantic“

character" of the non-affective factors can be determined). After completion of the affect/denotation separation in the scale factor matrix, a further application of Tucker's 70 three-mode factor analytic model is made toAttitudinal Differences Between High School Students and

T1但ir Parents 的 U.SA.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap compute the concept and subject factor structures and factorial relationships among subjects, concepts and meaning components in the core matrix.

Tzeng 71 has app1ied the above method to data of cross戶cultural personality research frcm Britain English

,

Finland Finnish,

Belgium Flemish,

and J apan Japanese with the following observations:(1) the separation of affect and denotation is not only theoretically possible but is also operationally successful by the method employed.

(2) Affective dimensions proved to be common to all cultures

,

confirming the hypothesis that pan-cu1tural markers also function as affective markers for indigenous persona1ity ratings.(3) The existence of denotative dimensions represented c1ear references for affect-free

“

description" of persona1ities.(4) Both cross-闢cul扯tura祉1 sca1e and concept factors inc1ude three ‘“‘'types訢" C叮roωss-“-cωu叫1泣1t叫ur叫a剖11勾ycornmon, culture specific, and sex/cu1tura1 specific.

(5) The

“

cross-cu1tura1" inner core matrix provides evidence for both intra-and inter-cultura1 differences.(6) Four kinds of reliability indices indicate high stability of the SD ratings. (7) The methodology deve10pe且 in the present study, a10ng with the SD technique can be applied to all kinds of sUbjects a:nd/or concept domains. By testing different age groups, unique patterns of cultura1 change in different concept domains can be obtained. Cross-cultural compa:rlsons on such patterns

co叫dbe of considerable importance for intemationa1 understanding.

Design of the Study

Rationale and Purposes

According to Tzeng 72 the process of human perceiving and judging involve

three m吋or variables: (1) the individua1s making judgmer此, (2) objects or issues being judged, an址 (3) the underlying psychologica1 frames of reference which subjects have developed. Individua1 differences in perceptions or attitudes are mainly due to their previous learning experiences or interactions with the environment. ln the present research of generations, it seems quite reasonable to apply Tzeng's theoretica1 framework of human perception for empirical va1idation of the so-called generation gaps. This implies 也atfor a subject popula-tion (e.g., high school students and their parents), while the issues or concepts of generational discrepancies can be defined as the object domain and the youth

Bulletin of National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

and their parents can be defined as the subject mode, the extent of generational discrepancies on issues can be measured by underlying psychological criteria.

Under 世lÎs theoretical formulation

,

areas of opinion differences should therefore be obtained through a naturalistic elicitation procedure as recom-mended by Tzeng 73 from both generations. Resultant items wi1l define theentire domain of generational discrepancies. Each item wi1l further reflect one öf the following three characteristics: (1) generational common variable - an

訂閱 of discrepancies perceived by both generations as significantly different, (2) parental unique variable - an area only perceived by parents as significantly different from their chi1dren

,

and (3) children unique variable - an area uniquely perceived by the youth (of either or both sexes). While the generationa1 common varia1;>les may be regarded as mutual perceived generation gaps, the parenta1 and children unique variables may be regarded as partial perceived generational gaps.It should be noted that since all elicited items are not automatically mutual independent, it is therefore necessary to reduce the entire item pool into an organized categorical set. Areas of generationa1 discrepancies will therefore become obvious in relations to human societal functions. However, these areas will only represent the qualitative gaps. The severity of these gaps (i.e., the quantitative properties of generationa1 gaps) should be measured independently. The semantic differentia1 technique which can accourit for the three variables in human perceptions is used for measurements of quantitative pro-perties of generationa1 gaps. In the process of selecting semantic differentia1 bi-polar sca1es for ratings of all important issues by both generations, Osgood's affective (eva1uation, potency and activity) markers wi11 be used and other concept domain relevant traits will a1so be constructed through a natura1istic elictation procedure.74 Given the present design of research, characteristics of

three sources involved in generational gaps - issues by psychologica1 framework by two subject generations - will become identifiable.

In order to investigate the fundamenta1 nature (direct as well as indirect ∞utses) of generationa1 gaps, a11 important potential sources and psychological correlates of generation g

Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and 7heir Parents 的 U.S.A.:A Case Study ofGeneration Gap confirmatory check of other reported fmdings.

Method and Strategies

The degree of interstratum similarity or cohesiveness in generation studies has received considerable attention in the past research. This is a1so the major focus of the present research as indicated above. Furthermore

,

due to the possible heterogeniety properties within the youth - a“

homogeneous" younger genera“ tion composing of heterogeneous components,

such as sex,

educationa1 leve1s,

and socia1 economic backgrounds,

the traditiona1 boundaries of age differentiations should not be the only independent variable to investigate the generations. Therefore in order to maximize the subject hOIJ.ì.ogeneity within generations,

the present study will focus on a high school student popu1ation in the Midwest with upper-middle socia1 economic background. Their parents will a1so be sampled. The issue of cohort solidarity can thus be examined.1o a fu11 extent. Comparisons of parenta1 perceptions on issues with their children's perceptions can further be made to provide more precise information on the dynamics of generationa1 gaps.In summary, the entire research procedure can be divided into three phases: (1) Elictation of significant opinions (issues) from both generations. This is to identify (categorize) the significant qua1itative domain of contemporary generation gaps. Within (sex) and between generation difference will be examined. (2) Construction of the opinion differential for rating of a11 selected semantic differentia1 sca1es. This is to obtain the three-mode data of subjects by concepts by sca1es for identification of psychologica1 structures of concept and semantic factors across different groups.

(3) Construction of various unidimensiona1 measurements for eva1u缸ion of the potentia1 sources and dynamics of generation gaps. This is to provide a foundation for integration of solutions from phases 1 and 2 and subsequently for a possible theorization of generation gaps.

It is c1ear that a11 these three phases are interrelated and equa11y important as f訂 as the investigation of the phenomena and dynamics of true generationa1 gaps is concerned. The detailed description of the method, procedures and resu1ts of these three phases will be presented separately in the following three chapters. Their relationships will be examined and integrated in Chapter V. Comparison between solutions from high school students in the present study and those from college

Bulletin o[ National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

the cohort so1idarity and dynamics of youth cu1ture changes withil1 the American indigenous culture.

Rationale,for Statistical Techniques

In order to provide objective accounts for the phenomena of the so-cal1ed generation gaps

,

various statistica1 techniques are employed in this study under considerations of measurement theories and practice. In Phase 1, the naturalistic approach used for e1iciting discrepant opinions is to gaurantee the relevancy and representativeness .of issues from the subject population. Based on proportiona1 distributions of response items, a fina1 setofrepresentative items can be obtained to maximize the re1iabi1ity and construct va1idity of solutions in Phase 11. Its solutions are therefore fundamenta1 for genera1ization of s01ution of the entire research.In Phase 11, as presented in Chapter 111, four major procedures are emp10yed: (1) the natura1istic e1icitation approach (to obtain a11 concept (i.e., issue) domain re1evant traits actual1y' used by individua1s), (2) content ana1ysis of elicited traits (to reduce a11 e1icited qua1ifiers to a representative 'set of sca1es with high frequency

,

productivity,

and diversity in usage across al1 subjects and concepts),

(3) three-mode factor ana1ysis (to identify) simultaneously factors of a11 three mode variab1es - issues,

SD sca1es,

and individua1s - and their interactions),

and (4) coefficients of congruence (to measure the simi1arities and differences 扭 factor structures of sca1es as well as concepts across a11 four generation/sex groups). All these techniques are under the considerations of (1) the content va1idity and representativeness of issues and of semantic criteria, (2) construct va1idity of measurement resu1ts, and (3) a11 possib1e information on intra- and inter-generationa1 comparisons of factor structures.In Phase 111, where ANOVA is used to identify 加tra- and inter-group differences wi th respect to a11 16 unidimensiona1 variab1es, m u1 tip1e regression ana1ysis' is used to predict the reported degrees (or behaviora1 aspects) of genera-tion gaps within each generagenera-tion/sex group. Therefore, since Phase II is concentrated on the measurements of behaviora1 dispositions (or conceptions) of generation gaps, and Phase 111 is on the measurements of socia1 and psychologica1 correlates

,

the integration of solutions from both phases wi11 further help our understanding of the dynamic relationships between individua1 dispositions and their socia1 behaviors and adjustments.Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents 的 U.S.A.怔 CaseStudy ofGeneration Gap

Notes

1. Tze時, O. C. S. Application of Semnatic Differential Technique in Social Behavioral Science Research. The Consortium of the Internationa1 Studies Program, 1976a .(in press).

2. .Osgood, C. E. Method and Theory in Experimental Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1953.

3. Bengíson, V. L., Furlong, M. J., & Laufer, R.S.

“

Time, Aging, and the Continuity of Socia1 Structure: Themes and Issues in Generationa1 Ana1ysis,"

The Joumal

0/

Social Issues, 1974, 30, 1-30.4. Comte, A. The Positive Philosophy

0/

August Comte. (Trans. by Martineau) London: Bell; 1896.5. M血, J. S. A System

0/

Logic, Ratio Inactive and Inductive. London: Longman's,

1961. (Orig. pub1ished 1843).6. Mannheim, K.

“

The problem of generations." In Essays on the Socio-logy0/

Knowledge. London: Routledge and Kegan Pau1,

1952. (Orig. pub1ished1923.)

7. Parsons, T.

“

Youth in the Context of Arnerican Society." In E. H. Erickson (Eι) , Youth: Change and Challenge. New York: Basic Books, 1963.8. Eisenstadt, S. N. From Generation to Generation. Glencoe: The Free Press, 1965.

9. Parsons, S. T., & P1att, A. M.

“

Higher educations and Changing Socia1 i-zation." In M. W. Ri1ey (Ed.), Aging and Society: A Sociology0/

Age Strati/ica“ tion. Vol. 3. New York: Russell Sage Foundation,

1972.10. Davis, K.“The Sociology of Parent-Y outh Conflict." American Socio-logical Review, 1940, 5, 523-534.

11. Berger1 B.

“

How Long Is a Generation?" British Journal of Sociology,1960, 2, 10-23. 12. Co1emar吭1,J.

American Journηwl of SO CÌ<的'01,扣'ogy, 1960,65,337-347.

13. Cain, L. 泣, Jr. “Life Course and Socia1 Structure." In E. Faris (Ed.), HandbookofModern Sociology. Chicago: Rand McNa11y, 1964.

14. Flacks, R. Youth and Socia! Change. Chicago: Markham, 1971.

15. Altbach, P. G., & Laufer, R. S. (Eds.), The New Pilgrims: Youth Protest in Transition. New York: David McKay, 1972.

16. Lipset,鼠, & Ladd, E. The politica1 future of activist generations. In

Bulletin o[ National Taiwan Normal University No. 28

P. Altbach & R. Laufer (Eds.)

,

The New Pilgrims: Youth Protest in Transition.New York: David McKay

,

1972.17. Roszak, T. The Making 01 a Counter Culture. Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday

,

1969.18. S卸lmons, J. 1., & Winograd, B. It's Happening: A Portrait 01 the Youth Scene Today. Santa Barbara: Marc-Laird, 1967.

19. Suchm妞, E. A.“The Hang-loose Ethic and the Spirit of Drug Use," Joumal 01 Health and、 SocialBehavior, 1968, 9, 140-155.

20. Bengtson

,

V. L . “The Generation Gap: A Review and Typology of Socia1-psychologica1 Perspectives," Youth and Society, 1970, 2, 7-32.2剖1. Friendenber喀3莒~, E.

01 Social Issues, 1969,25(2),21-38. (a)

22. Friedenberg, E. “The Generation Gap," Annals 01 the American Academy 01 Political and Social Science, 1969,382,33-42. (b)

23. Mead

,

M. Cu/ture and Commitment: A Study 01 the Generation Gap. New York: Basic Books, 19了O.24. Lautì缸, R., & Light, D.

“

The Origins and Future of University Protest." In D. Light (Ed.),

The Dynq.mics 01 University Protest. Chicago: Nelson Ha11,

1974.25.SSlater

,

P.The Pursuit ofLoneliness-Boston:Beacon Press,

1970. 26. Adelson, J.“

What Generation Gap?" New York Times Magazine,1970

,

Jan. 18 (Section 6),

10-45.27. Campbell, E. Q.

“

Adolescent Socia1ization." In D. A. Goslìn (Ed.), Handbook 01 Socialization Theory and Research. Chicago: Rand McNa11y, 1969.28. Wa1sh

,

R . “Intergenerationa1 Transmission of Sexua1 Standards." Paper presented at the meeting of the American Sociologica1 Association, Washington, D.C., September 1970.29. Yankelovich, D. The Changing Values on Campus. NewYork: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

30. Benedict, R.

“

Continuities and Discontinuities 姐 Cu1tura1 Condition-扭g." Psychiatηι1938, 32, 244-256.31. H剖, R. FamilyDevelopment in Three Generations. Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman

,

1970. (a)32. H剖, R.

“

The Three-generation Research Design: Method for Studying Farni1y and Socia1 Change." In R. H血 S. R. Kon站 (Eds.), Families in East and West: Sociolization Process and Kinship Ties. Paris: Moulton,

1970. (b)-Attitudinal Differences Between High School Students and Their Parents 的 U.SA.:ACase Study ofGeneration Gap 33. Thomas, L. E.

“

Political Attitude Congruence Between Politically Active Parents and College回age Chi1dren." Journal of Marriage and The Family,1971,33,375-386.

34. Connell, R. W.

“

Political Socia1ization in the American Fami1y: The Evidence Re-examined." Public Opinion Quarterly,

1972.36,

321-333.35. Bengtson, V. L., & B1ack, K. D.

“

Intergenerational Relations and Continuities in Socialization." In P. Baltes & W. Schaie (Eds.),

Life-span Develop-mental Psychology: Personality and Socialization. New York: Academic Press,1973.

36. Jennin蟬, M. K.

Paper Presented at the International Political Science Association Congress

,

Montreal, August 1973.37. A1dous, J., & Hi11, R . “Social Cohesion, Lineage Type, and Inter-generational Transmission." Social Forces, 1965,43 ,421-432.

38. Keniston, K. Young Radicals. New York: Harcourt‘ Brace & World, 1968.

39. Riley, M. W., Johnson, M., & Foner, A. Aging and Society: A Socio-logy of Age Stratification. Vo1. 3. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1972.

40. Hayakawa

,

S. 1 . “Mass Media and Fami1y Communications." Paper Presented at the Meeting of the American Psychologica1 Association, San Fran-cisco, August 1968.41. Bengtson, Furlong, and Laufer, Time, Aging and the Continuity,

pp. 1-30.

42. Buys

,

C. J.“

Student-Father Attitudes Toward Contemporary .Social Issues." Psychological Reports, 1972, 31, 699-706.43. Lerner, R. M., Pendo呵, J. and Emery, A. '‘Attitudes of Adolescents and Adu1ts Toward Contemporary Issues." Psychological Reports, 1971, 28,

139-145.

44. Lerner, R. M., Schroeder,仁, Rewitzer, M., and Weinstock, A.

“

Attitudes of High School 'Students and Their Parents Toward Contemporary Issues." Psychological Reports, 1972, 31, 255-258.45. Blum, R. H. and Associates. Students and Drugs. San Francisco: Joss呵呵 Bass Inc.

,

1969.46. Goode, E. The Drug Phenomenon: Social Aspects of Drug Taking. New York: The Bobbs-Merri11 Cornp. Inc., 1973.

47. Rams呵, C. E. Problems of Youth: A Social Problems Perspective.