Abstract

This project was expected to contribute to the construction of a more complete L2 motivation theory by a quasi-experiment testing whether learners’ L2 proficiency matters in forming dynamic state motivation (Tremblay et al., 1995) and whether it should be considered as an important component in an L2 motivation theory.

In her doctoral dissertation investigating the effects of attention-oriented pre-reading materials on situational EAP reading motivation, the researcher discovered that existing L2 motivation theories failed to explain the results obtained. A speculation for possible explanations is that a mismatch between learners’ given L2 proficiency and the language difficulty of the task may be accountable for the absence of expected effect from motivational strategies. However, a close review of L2 motivation literature and related motivation theories made one believe that learners’ relative L2 proficiency against the language proficiency required by the task is not an issue in examining state motivation. This research was thus designed toward testing the necessity of including an L2 element in a situation-specific L2 motivation theory.

Based on the above-mentioned objective, this study recruited about 360 college students to complete a quasi-experiment. Each participant performed three assigned reading tasks with the same format and similar content except that the L2 difficulty was set at three different levels. Immediately after the task is completed, students’ situational, or state, motivation were measured by using Keller’s IMMS (Instructional Materials Motivation Survey, 1987). Two pieces of data were collected in the pretest stage – participants’ original proficiency level and their more stable trait motivation in EFL learning. The resulted IMMS scores were compared among three types of reading tasks and the two pretest scores were used as covariates in an ANCOVA analysis. Furthermore, participants’ original motivation level was compared against their state motivation levels under three types of tasks by using regression analysis.

Initial results support the original hypothesis.

Introduction

L2 motivation research has shifted from the macro perspective (e.g. Gardner’s socio-cultural tradition, 1985) towards more situation-specific and process-oriented approaches (Kormos and Dornyei, 2004). In an attempt to propose a framework that can accommodate such a dynamic perception of task motivation (i.e., state motivation realized in carrying out learning tasks), Dornyei (2003) proposed a ‘task processing system’ to describe how task motivation is negotiated and finalized in the learner. The three mechanisms making up Dornyei’s task-processing system include task execution, appraisal, and action control. While the three mechanisms account for learners’ decision-making behavior, Huang (2004), from the results of a quasi-experimental study testing effects of motivational strategies on situational EAP reading motivation, speculates that, underlying the three mechanisms, one important element has been missing, that is, the relative language difficulty of the task in comparison with the learners’ L2 proficiency level.

Review of Literature

Motivation in L2 learning, since the 1994 Modern Language Journal debate (Dornyei, 1994; Gardner and Tremblay, 1994a; Gardner and Tremblay, 1994b; Oxford, 1994; and Oxford and Shearin, 1994), has broadened its scope to include various perspectives borrowed from psychology and other related areas of applied science (e.g. Dornyei, 2001; Oxford, 1999) so that different levels of motivation are dealt with and more informed pedagogical implications become possible. Dornyei and Otto’s most recent Process Model of L2 Motivation (Dornyei and Otto, 1994 and Dornyei, 2001) is an attempt to synthesize a number of lines of different research in a unified

framework for constructing a non-reductionist, comprehensive model. One of the features that distinguishes their model from previous ones is that their model inclusively describes motivational influences and action sequence at preactional, actional, and postactional phases. As Dornyei (2001) argues, traditional L2 motivation studies have targeted ‘the more general and stable aspects of motivation’ such as attitudes, beliefs and values. They are primarily associated with the preactional stage in Dornyei and Otto’s model. Studies at preactional stage, however,

are less adequate for predicting actual L2 learning behaviors demonstrated in the classroom because learner behaviors during the actional stage tend to be energized by a second set of motivational influences: executive motives. These are largely rooted in the situation-specific characteristics of the learning context and…I believe that they show few overlaps with motives fuelling the preactional stage. (Dornyei, 2001; p. 187)

Crookes and Schmidt (1991), as early as a decade before Dornyei and Otto’s model, reopened L2 motivation research agenda from the then predominant socio-educational approach and proposed to view L2 motivation from different levels to better connect L2 motivation research with L2 learning. The four levels were the micro level, the classroom level, the syllabus level, and considerations relevant to informal, out-of-class, and long-term factors. Crookes and Schmidt (1991) argued that conceptually much work on L2 motivation had not dealt directly with motivation at all. They adopted Keller’s (1983) education-oriented theory of motivation and defined motivation in terms of choice, engagement, and persistence, as determined by interest, relevance, expectancy, and outcomes. Dornyei (1994) classifies motivational components by similar level categories. His three levels are language level, learner level, and learning situation level. Under the learning situation level,

three motivations were specified, including course-specific, teacher-specific, and group-specific ones. He contends that for course-specific motivational components, Crookes and Schmidt’s (1991) four-dimension framework, which was in turn based on Keller’s motivational system, appears to be particularly useful in describing course-specific motives. Motivation, as conceptualized in these models, is eventually shifted from the static description of learner characteristics and is now closely related to the day-to-day teaching and learning.

Purposes of the Study

The present study is most concerned with Dornyei’s (2001) actional stage where executive motivational influences, in addition to longer-term influences brought from the preactional phase, affect learners’ appraisal on whether and how they carry out learning actions. For the actional phase, Dornyei (2001) stated “Probably the most important influence on ongoing learning is the perceived quality of the learning

experience” (p. 97). Learners’ stimulus appraisal as listed in Dornyei and Otto’s

model (borrowed from Schumann’s theory) – on novelty, pleasantness, goal/need significance, coping potential, and self and social image – influences their action and action intensity. Among these areas of appraisal, “coping potential”, in a foreign language setting, is closely related to the learner’s L2 proficiency versus the L2 difficulty of the learning task. The researcher hypothesized that, for an L2 motivation theory to be specific to the foreign language setting, it is necessary to isolate the L2 element as an individual component in the theory. The two research questions are as follows.

1. Did learners’ state motivation levels differ when the learning task was different in language difficulty?

proficiency compatible with the L2 difficulty of the task?

Research Method

In this study, each participant was given three reading tasks with different language difficulty levels – a beginner version, an intermediate version, and an advanced version. It was hypothesized that, when other conditions remain constant, participants’ situational motivation level would be higher when the reading task is compatible with their own L2 proficiency level. When the task is comparatively too difficult or too simple, i.e., incompatible with learners’ given L2 proficiency level, their original trait motivation level would be diminished and the result becomes a lower situational motivation. It is hoped that the results would demonstrate that learners’ relative L2 proficiency against the task is an important element in determining state L2 motivation and should be included in a comprehensive L2 learning motivation theory to account for the situational characteristics of L2 motivation.

Participants:

About 160 students were recruited from a northern Taiwan university. They were college juniors and seniors majoring in different disciplines with about 8 to 12 years of prior experience in learning EFL.

Data Collection Procedure:

All participants went through the following procedures.

1. Pretests: Participants completed a pretest on EFL proficiency and another on EFL motivation. The EFL proficiency indicator was represented by a mock TOEIC test and the trait motivation indicator will be represented by two selected parts of Attitude/ Motivation Test Battery (Gardner, Tremblay, & Masgoret, 1997).

These two pieces of information were used as covariates in the ANCOVA analysis.

2. The experiment: Participants were given three identical reading tasks. In the task, they read independently four short passages describing four different points of attraction in a U.S. city. After they finished the reading, there were four short-answer questions for them to decide which place in the city is best for doing a certain activity. Immediately after they completed the reading task, a posttest, i.e., Keller’s (1987) IMMS (Instructional Materials Motivation Survey), were administered to collect information on participants’ state motivation level. The same procedures were repeated three times so that each participant will experience all of the three versions, the beginner, the intermediate, and the advanced one. To avoid the problems of reading the same content with different difficulty level, three versions of the task describing three different cities were designed.

The Reading Task:

The task was designed based on a reading exercise from New Interchange Intro –

English for International Communication (Richards, 2000; p. 85). Students read

four 40-word short passages describing four places in downtown New York City – Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, New York Public Library, and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Students were asked to answer these questions after they completed the readings:

Where can you…?

1. have a view of the city _____________________ 2. go ice-skating in the winter _____________________ 3. listen to music outdoors _____________________ 4. sit quietly indoors _____________________

materials proposed by Keller, the original photos were kept, a guiding question to build personal relevance (e.g. If you have a chance to visit New York City…) were embedded.

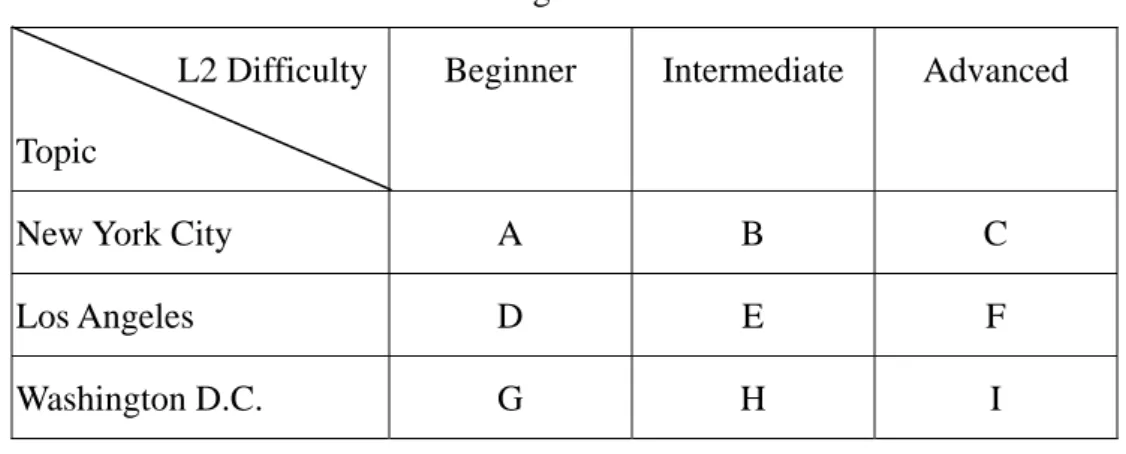

The articles from the above-mentioned textbook (Version A in Table 1) were used as the beginner version. Two more versions, the intermediate and the advanced (Versions B and C in Table 1), were also developed so that three tasks are identical with the only exception of language difficulty.

Based on the same format, two more similar sets of reading tasks were designed by the researcher for the purpose of this study – one describing points of attraction in Los Angeles and another in Washington D.C. For each of the two cities, three versions – beginner, intermediate, and advanced – were written. Details are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: All Nine Versions of Reading Tasks L2 Difficulty

Topic

Beginner Intermediate Advanced

New York City A B C

Los Angeles D E F

Washington D.C. G H I

Counterbalancing:

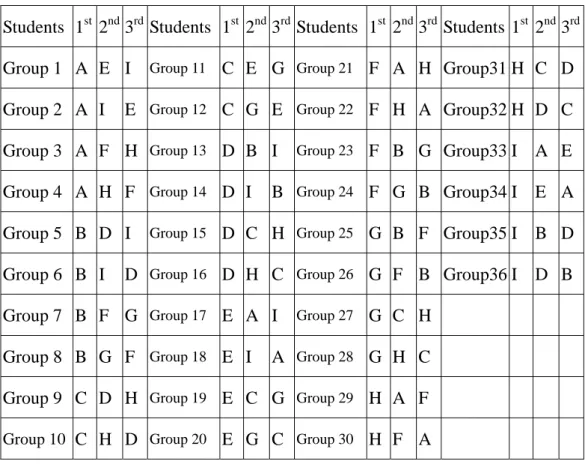

In order to have participants read with three different difficulty levels, three versions were designed under the same topic. In order not to have students read the same content under different difficulty level, three different topics were created. So one student read the beginner version of NYC, the intermediate version of L.A., and the advanced version of D.C. To counterbalance the articles and to eliminate the possible sequence effect, all twenty-eight possible combinations were included in

grouping participants. The 36 possibilities of combination are shown in Table 2. All 360 participants were randomly assigned into one of the 36 groups and there were 10 students in each group.

Table 2: Counterbalancing Plan for the Nine Versions of Task

Students 1st 2nd 3rd Students 1st 2nd3rd Students 1st 2nd3rd Students 1st 2nd 3rd Group 1 A E I Group 11 C E G Group 21 F A H Group31 H C D Group 2 A I E Group 12 C G E Group 22 F H A Group32 H D C Group 3 A F H Group 13 D B I Group 23 F B G Group33 I A E Group 4 A H F Group 14 D I B Group 24 F G B Group34 I E A Group 5 B D I Group 15 D C H Group 25 G B F Group35 I B D Group 6 B I D Group 16 D H C Group 26 G F B Group36 I D B

Group 7 B F G Group 17 E A I Group 27 G C H

Group 8 B G F Group 18 E I A Group 28 G H C

Group 9 C D H Group 19 E C G Group 29 H A F

Group 10 C H D Group 20 E G C Group 30 H F A

Results and Discussion

Initial statistical results seemed to support the first research hypothesis; however, for the second research question, the results did not suggest a clear pattern. From our preliminary analysis, the difficulty level of the target language influenced students’ state motivation with a curvilinear model, i.e. when the difficulty level was low or high on the two extremes, learner motivations tended to be lower; and when the difficulty level matched their proficiency level, state motivation was highest. The inconclusive result for the second research question seemed to have to do with the homogeneity and small sample size of participants. The researcher is still

trying to further work on the data and look for possible explanations by reviewing literature from areas outside of L2 motivation.

Reference:

Chang, M.M. and Lehman, J.D. 2002. Learning foreign language through an interactive multimedia program: an experimental study on the effects of the relevance component of the ARCS model, CALICO Journal, 20, 1, 81-98. Crookes, G. and Schmidt, R.W. 1991. Motivation: Reopening the research agenda.

Language Learning, 41: 469-512.

Dornyei, Z. 1994. Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom.

Modern Language Journal, 78: 273-84.

Dornyei, Z. 2001. Teaching and Researching Motivation. Pearson Education Limited. Edinburgh, England.

Dornyei, Z. 2003. Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: advances in theory, research, and applications. In Zoltan Dornyei (Ed.), Attitudes,

orientations, and motivations in language learning (pp. 3-32). Oxford:

Blackwell.

Dornyei, Z. and Kormos, J. 2000. The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance. Language Teaching Research, 4: 3, 275-300.

Dornyei, Z. and Otto, I. 1998. Motivation in action: A process model of L2

motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics (Thames Valley University,

London) 4: 43-69.

Gardner, R. C. 1985. Social psychology and second language learning : the role of

attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C. and Tremblay, P. F. 1994a. On motivation, research agendas and theoretical frameworks. Modern Language Journal, 78: 359-68.

Gardner, R. C. and Tremblay, P.F. 1994b. On motivation: measurement and conceptual considerations. Modern Language Journal, 78: 524-7.

Gardner, R.C., Tremblay, P.F., and Masgoret, A.M. 1997. Towards a full model of second language learning: an empirical investigation. Modern Language Journal,

81: 344-62.

Huang, Shu-chen. 2004. Effects of Attention-oriented Pre-reading Materials on Situational EAP Reading Motivation and the Analysis of Learner Preference, unpublished doctoral dissertation, National Taiwan Normal University. Keller, John M. 1999. Using the ARCS motivational process in computer-based

78, 39-47.

Keller, John M. 1987. Development and use of the ARCS model of motivational design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10: 3, 2-10.

Keller, John M. 1983. Motivational design of instruction. In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.)

Instructional Design Theories and Models: an Overview of their Current Status.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 384-434.

Kormos, J. & Dornyei, Z. 2004. The interaction of linguistic and motivational variables in second language task performance. Zeitschrift fur Interkulturellen

Fremdsprachenunterricht [Online], 9(2), 19 pp. Erhaltlich unter http://www.ualberta.ca/~german/ejournal/kormos2.htm

Oxford, R. L. 1994. Where are we with language learning motivation? Modern

Language Journal, 78: 512-14.

Oxford, R. L. 1999 (Ed.). Language Learning Motivation: Pathways to the New Century. University of Hawaii Press.

Oxford, R. L. and Shearin, J. 1994. Language learning motivation: expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78: 12-28.

Richards, J. C. 2000. New Interchange – Intro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tremblay, P.F., Goldberg, M.P., and Gardner, R.C. 1995. Trait and state motivation and the acquisition of Hebrew vocabulary. Canadian Journal of Behavioural

Science, 27, 2.

Warden, C.A. & Lin, H.J. 2000. Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting. Foreign Language Annals, 33, 5, 535,547.