國

立

交

通

大

學

管理科學系碩士班

碩

士

論

文

探討品牌權益與服務失敗歸因之交互作用對於顧客

滿意度的影響

The Interactive Effects between Brand Equity and

Firm’s Controllability over a Service Failure on

Customer Satisfaction

研 究 生:施慧妤

指導教授:張家齊 博士

探討品牌權益與服務失敗歸因之交互作用對於顧客

滿意度的影響

The Interactive Effects between Brand Equity and

Firm’s Controllability over a Service Failure on

Customer Satisfaction

研 究 生: 施慧妤 Student: Hui-Yu Shih

指導教授: 張家齊 博士 Advisor: Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

國 立 交 通 大 學 管 理 科 學 系

碩 士 論 文

A Thesis

Submitted to Department of Management Science College of Management

National Chiao Tung University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master

in

Management Science

June 2008

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

探討品牌權益與服務失敗歸因之交互作用對於顧客滿意度的影響

學生: 施慧妤 指導教授: 張家齊 博士國立交通大學管理科學系碩士班

中文摘要

本篇論文主要是在研究品牌權益與服務失敗歸因之交互作用對顧客滿意度的影 響。本篇作者檢視兩種對立的假設,一個是愛是盲目的效果,另一個是由愛生恨效果。 過去文獻指出高品牌權益公司代表顧客有大量的品牌知識和許多容易取得且正面的品 牌連結,此時當消費者將服務失敗歸因為公司不可控制時,會強化消費者對高品牌權益 公司的同化謬誤,產生愛是盲目效果,為公司創造了一個避免滿意度受創的緩衝機制; 反言之,一旦消費者認知到服務失敗是公司可以高度控制時,則強化對比效果,消費者 會擴大對產品表現和預期之間的差異,由愛生恨,高品牌權益的消費者變得更不滿意。 本研究結果暗示公司除了引導顧客瞭解發生服務失敗的原因,讓顧客瞭解在某些特定情 況下,公司只有有限的失敗控制能力,展現公司有進行預防失敗的努力;另外,管理者 必須重視公司的品牌權益,則發生低度控制的失敗時,對公司產生有利的緩衝機制。 關鍵字:品牌權益、服務失敗歸因、負面情緒The Interactive Effects between Brand Equity and Firm’s Controllability over a

Service Failure on Customer Satisfaction

Student: Hui-Yu Shih Advisor: Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

Department of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

This study investigates the effects of brand equity on customer satisfaction after

service failures. We posit that the effects of brand equity are contingent upon the attributions

customers make about the firm’s controllability over a service failure. Two competing

hypotheses are examined and reconciled. The “love is blind” hypothesis posits that when low

controllability is inferred, the satisfaction reduction after a service failure (compared to

satisfaction before a service failure) will be smaller for high-equity brand than for low-equity

brand. On the other hand, the “love becomes hate” hypothesis specifies that when high

controllability is inferred, the satisfaction reduction after a service failure will be stronger for

high-equity brand than for low-equity brand. The hypotheses are tested with a scenario

methodology and this study conducted research in two service industries: hair salons and

restaurants.

Acknowledgement 這份論文可以順利完成,必須感謝很多人,首先,謝謝我的指導教授,張家齊博士, 對於論文細心、耐心的指導,老師對研究嚴謹的態度與對學術的熱忱,讓我獲益良多, 每個禮拜充滿歡笑與淚水的互動,為研究所生涯留下非常深刻的回憶。感謝我的家人, 阿嬷、爸媽、哥哥和家家,對我求學過程一路的支持和信任,給我最溫暖、最窩心的寵 愛,包容我的任性,讓我沒有後顧之憂的完成學業。 另外,感謝提供許多研究建議的學長姐們,特別要感謝佳誼學長的大力協助,在遇 到瓶頸的時候,不時提供相關文獻供我參考,給予非常多寶貴的意見;以及最特別的張 門五人小組,總是能讓我迴旋式笑開懷的瞇路柏源、培真小天才、大魔王艾芸和比我還 健忘的室友雅君,能和你們成為同門真的是很幸運的一件事,無數個挑燈夜戰的晚上, 你們的一路相隨、不離不棄、彼此打氣打鬧,因為你們,讓每個禮拜延長又加碼的六小 時Meeting 變成開心的事;因為你們的督促,才能讓我不斷向前、完成我的碩士論文。 還有,最感動的是許多管科 95 級同學們的陪伴,回想起這兩年,只要有人生日,大家 都會聚在一起唱歌玩樂喝酒,謝謝你們豐富我的研究生活,讓我在壓力下仍能非常快樂 地研究。最後,必須感謝每個曾經協助我完成碩士論文的人,陪我一路走來的最愛姊妹 們和很多很多好朋友的鼎力相助,由於大家好心地幫我填寫問卷,我才能順利完成論文。 這個彷彿過了半個世紀之久的研究所生涯,終於要劃下句點了,有很多不捨與感 謝,而這份感動將一直留在我心裡,也謝謝交大提供我一個很好的學習環境,才能成就 如今磨練後的我。 施慧妤 謹誌於 民國 97 年於新竹交大管科

Index

中文摘要...i

Abstract ...ii

Acknowledgement...iii

Table Index...vi

Figure Index ...vii

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research Background ...1

1.2 Research Motivation...2

1.3 Research Objectives ...3

1.4 Literature Structure ...4

Chapter 2 Literature Review... 5

2.1. Brand equity...5

2.2 Two rival explanations: “Love is blind” versus “Love becomes hate”...8

2.2.1 Love is blind ...8

2.2.2 Love becomes hate ...9

2.3 Firm’s controllability over failure... 11

2.4 Negative emotions...13 2.5 Satisfaction Reduction...14 2.6 Patronage Reduction ...15 2.7 Hypotheses...16 2.8 Research Framework ...19 Chapter 3 Methodology ... 21

3.1 Conceptual Research Framework...21

3.2 Experimental Design ...22 3.2.1 Experiment Procedure...22 3.2.2 Stimulus Development ...24 3.3 Measurements ...26 3.3.1 Brand Equity...26 3.3.2 Negative emotions...26 3.3.3 Satisfaction...27 3.3.4 Patronage Reduction ...27

3.3.5 Firm’s Controllability Over Failure...27

3.4 Data Collection and Analysis Methods ...28

3.5 Pretest ...28

Chapter 4 Research Analysis and Results ... 29

4.1 Background of Participants...29

4.3.1 Manipulation Check of brand equity...31

4.3.2 Manipulation Check of Controllability...32

4.4 Analysis of Results ...32

4.4.1 Service Industries ...32

4.4.2 Brand Equity with Firm’s Controllability over failure and Negative Emotions ...35

4.4.3 Brand Equity with Firm’s Controllability over failure and Satisfaction reduction ...42

4.4.4 Brand Equity with Firm’s Controllability over failure and Patronage Reduction ...49

Chapter 5 Discussion and Future Research ... 56

5.1 Discussion of Results ...56

5.1.1 The “Love is blind” effect...56

5.1.2 The “Love becomes hate” effect...56

5.2 Implications...57

5.3 Limitations ...59

5.4 Future Research...60

Reference ... 61

Appendix A Scenarios (Haircut)... 64

Appendix B Scenarios (Restaurant)... 68

Table Index

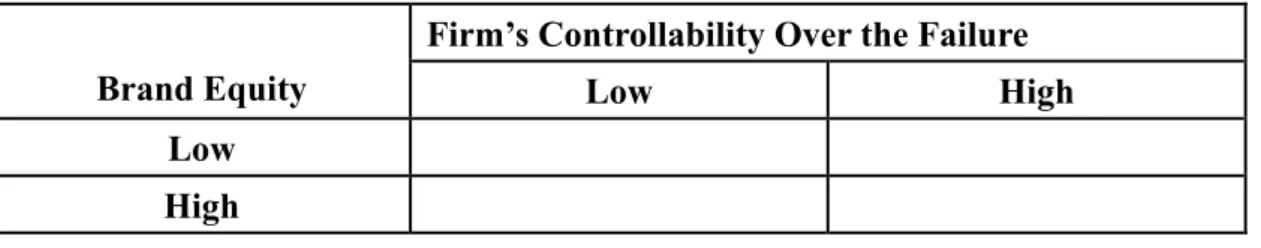

Table 1 Experimental design ...23

Table 2 Demographics of Participants...30

Table 3 Reliability Statistics ...31

Table 4 Manipulation Check of Brand Equity...32

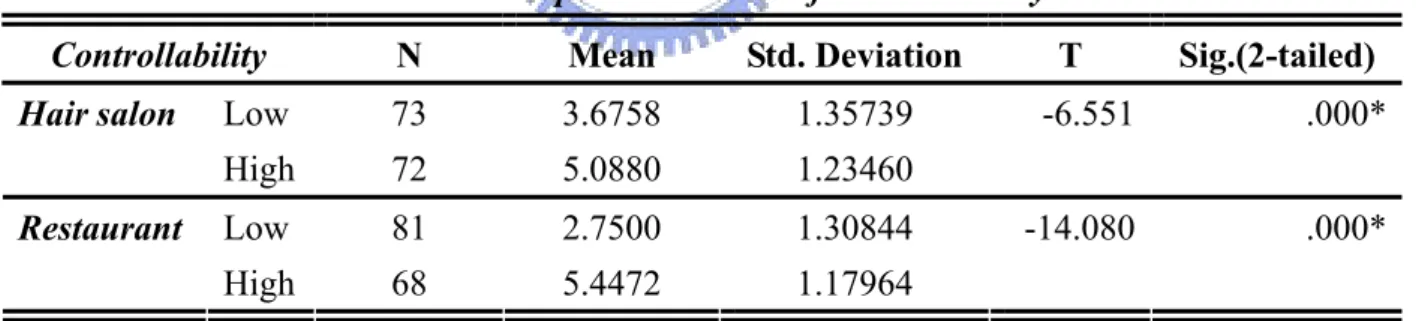

Table 5 Manipulation Check of Controllability...32

Table 6 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects...33

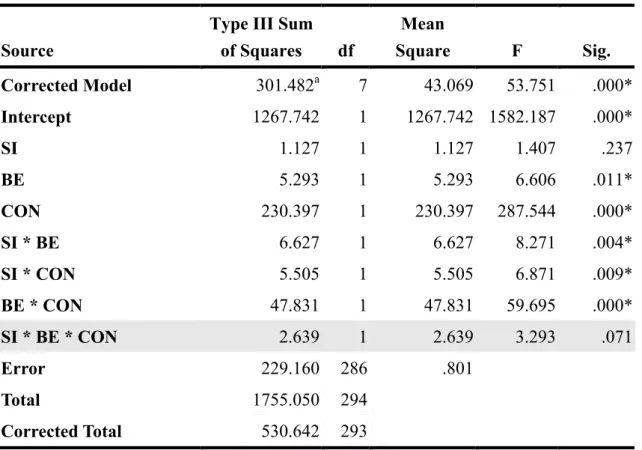

Table 7 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ...34

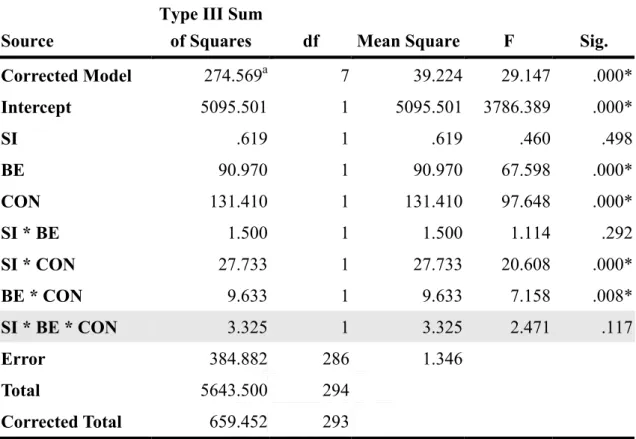

Table 8 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ...35

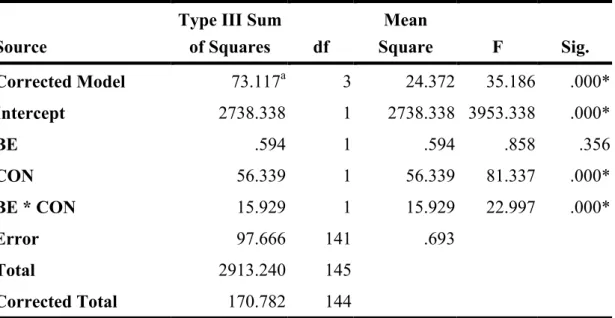

Table 9 Descriptive Statistics (Hair salon)...36

Table 10 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Hair salon)...37

Table 11 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD) ...38

Table 12 Descriptive Statistics (Restaurant) ...40

Table 13 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Restaurant) ...40

Table 14 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)...41

Table 15 Descriptive Statistics (Hair salon) ...43

Table 16 Tests of Brand Equity and Controllability (Hair salon)...44

Table 17 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)...45

Table 18 Descriptive Statistics (Restaurant) ...46

Table 19 Tests of Brand Equity and Controllability (Restaurant) ...47

Table 20 Multiple Comparisons (LSD)(Restaurant) ...48

Table 21 Descriptive Statistics (Hair salon)...50

Table 22 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Hair salon)...50

Table 23 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)...51

Table 24 Descriptive Statistics (Restaurant) ...53

Table 25 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Restaurant) ...53

Figure Index

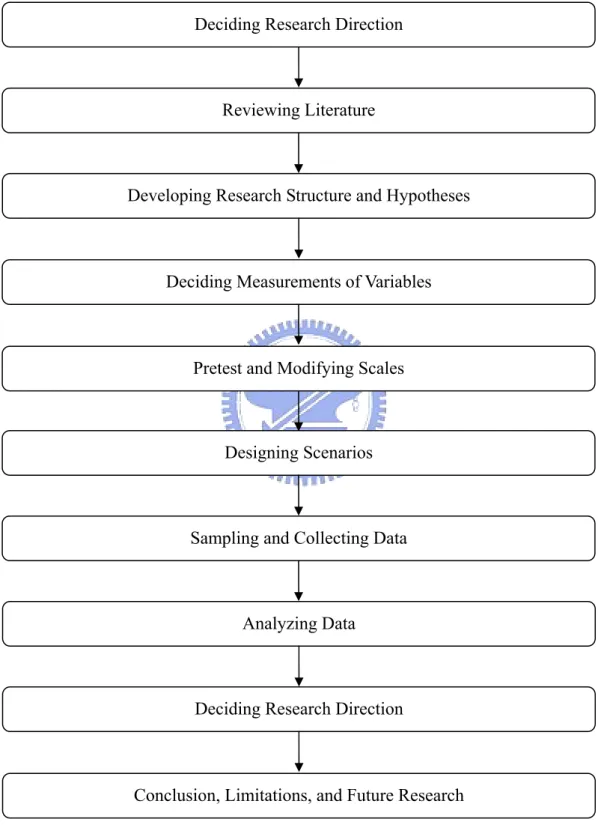

Figure 1 Research Flow...4

Figure 2 Composition of Brand Equity ...6

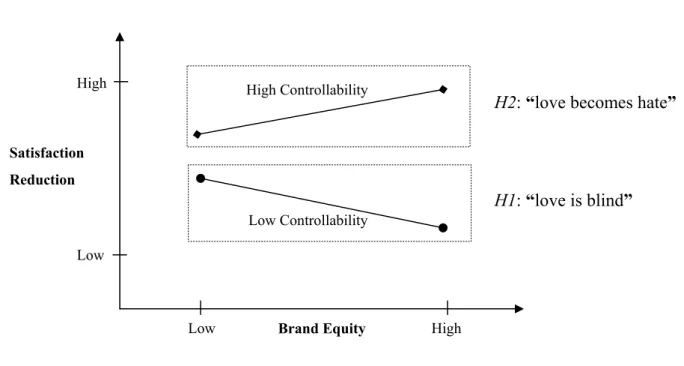

Figure 3 Research Framework (1)...20

Figure 4 Research Framework (2)...20

Figure 5 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Hair salon)...39

Figure 6 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Restaurant) ...42

Figure 7 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Haircut) ...46

Figure 8 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Restaurant) ...49

Figure 9 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Haircut) ...52

Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Research Background

No one in the service industry can entirely escape failure (Fisk, Brown, & Bitner, 1993).

Although service firms try to offer a high level of quality in their activities, they are unlikely

to be able to eliminate all service failures (Miller et al. 2000; Lewis & Spyrakopoulos, 2001).

The very personal and intangible characteristics of service delivery frequently produces

situations in which customer needs are misjudged or mishandled, resulting in customer

dissatisfaction. Even well-respected and highly esteemed brands sometimes fail their

customers. Most of us have had the experience of purchasing a venerable brand, but

eventually finding that after-sales service is quite disappointing. When a failed brand

possesses high a priori equity, how customers react is a very important issue. We need to

examine the relationship between brand equity and consumer response to service failure.

Branding theory suggests that the benefit of positive associations enjoyed by a

high-equity brands predisposes favorable responses to it (Keller, 1998). Previous research has

stressed that high-equity brands are more profitable because customers shop more regularly,

spend more per visit (Wulf, Odekerken-Schroder, & Iacobucci, 2001) and are willing to pay a

premium on the products and services they buy (Dowling & Uncles, 1997). Brand equity

represents a key asset for service firms, but it also is at risk of a failed service experience.

of a high-equity brand. First, according to the disconfirmation paradigm (Richard L. Oliver,

1981), customers’ expectations serve as a salient reference point when evaluating the current

consumption experience. Therefore, as frustration is compounded by the high expectations

attached to brands of strong stature, consumers’ adverse reactions may escalate. Second, other

researchers have found that high brand equity provides an important buffer to service firms

when service failures occur, resulting in less dissatisfaction (Goodman, Fichman, Lerch, &

Snyder, 1995; Hess Jr, Ganesan, & Klein, 2003; Kelley & Davis, 1994).

Therefore, it is imperative that managers should carefully consider what conditions

might “soften the blow”, or may mitigate customers’ negative responses toward the failure of

a high-equity brand. This issue is at the center of this research.

1.2 Research Motivation

Service failures are the leading cause of customer switching behaviors (Keaveney, 1995).

For decades researchers have studied branding theory and service failures. Understanding

how brand equity affects customer responses to service failure is important because service

failures have the potential to switch loyal customers to “enemies”. The consequences are very

serious for a firm’s reputation and long-term profitability. Therefore, we focus on the effects

of brand equity upon customers’ negative emotions and satisfaction after service failures.

In addition, integrating the contributions of brand equity and the investigation into

about the causes of service failures (causal attributions) moderate the relationship between

brand equity and satisfaction. This is an issue that has not been sufficiently studied to date.

Finally, this study offers a framework that reconciles these two competing explanations:

the “love is blind” versus the “love becomes hate” effects.

1.3 Research Objectives

In view of the above, the research aims to find:

1. The differences of customer responses to service failures by high-equity brands and

low-equity brands.

2. Whether the role of causal attributions (controllability) would moderate the effect of

1.4 Literature Structure

This research includes five chapters, and the outline of each chapter is as follows:

Figure 1 Research Flow

Deciding Research Direction

Reviewing Literature

Developing Research Structure and Hypotheses

Deciding Measurements of Variables

Sampling and Collecting Data Pretest and Modifying Scales

Designing Scenarios

Analyzing Data

Deciding Research Direction

Chapter 2 Literature Review

This research posits that the effects of brand equity on customers’ responses depend on

the attributions customers make about a firm’s control over failures.

First, we need to know that when services or products fail, people tend to engage in

causal attributions (Weiner, 2000). Typically, causal attributions can result in three types of

blame: customers think it was the service firm's fault, they don't know exactly who to blame,

or they become aware that they are partly to blame (Laufer, David, & Mayer, 2005). If the

failure is perceived to be partly attributable to the customer, or if the service firm's ability to

control the failure is ambiguous, the negative effect is lessened. Conversely, if the firm is seen

as having had control over the failure but did not prevent it, then customer reactions are

highly negative (Sunmee C & Mattila, 2006). Attributions about controllability are important

in this research because they are thought to increase the customers’ negative emotions and

dissatisfaction toward a firm after service failures (Folkes, 1988).

2.1. Brand equity

After the term “Brand Equity” appeared in the 1980s, it became more and more popular

in marketing theory and practice. Aaker (1991) noted that brand equity is a set of brand assets

and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol, which add to or subtract from the value

provided by a product or service to a firm and to that firm’s customers.

brand equity, including brand associations, brand awareness, perceived quality and loyalty

(Aaker, 1991). The concept of brand equity is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Composition of Brand Equity

Zeithaml (1988) defines perceived quality as “the consumer’s judgment about a

product’s overall excellence or superiority”. High perceived quality means that, through the

long-term experience related to a brand, consumers recognize the differentiation and

superiority of the brand. They are confident that a brand is dependable and can be relied on to

serve them well. Therefore, high perceived quality would drive a consumer to choose a

particular brand rather than other, competing brands.

Brand loyalty makes consumers purchase a brand routinely and resist switching to

another brand. Loyal consumers show more favorable responses to a brand than non-loyal or

switching consumers do. They love to maintain their relationship with a firm.

Brand awareness can provide familiarity with a brand and a signal of substantiality and Brand Equity Asset Customer Consciousness Customer Action Brand Associations Brand Awareness Perceived Quality Brand Loyalty Other Proprietary Brand Assets

promise. If customers know the brand, they usually select familiar products when making

purchase decision.

Brand associations are complicated and connected to one another, and consist of multiple

ideas, episodes, instances and facts that establish a solid ground of brand knowledge. Brand

association can assist a customer to deal with or memorize information. The information

becomes the basis of product differentiation and product extension, and which will provide a

purchasing reason for customers, and give rise to positive feeling.

According to the literature, brand equity is a multidimensional concept. The appraisal of

brand equity can be assessed from the viewpoint of the manufacturer, distributor or customer.

This study focus on a “customer-based” conceptualization of brand equity to characterize

high-equity brands as those for which consumers have substantial knowledge structures that

often include associations that are both readily accessible and positive in valence (Aaker,

1991, 1996; Keller, 1993, 1998). By these criteria, Disney would constitute an example of a

brand with strong equity for many consumers, because favorable associations may be

available in long-term memory as a result of personal experience or exposure to heavy

advertising campaigns and other communications about the very prominent Disney brand.

Branding theory suggests that a cache of positive associations enjoyed by a high-equity brand

predisposes favorable responses to it (Keller, 1998).

access relatively few positive associations, may experience comparatively little change in the

wake of a performance failure. Knowing fairly little about a brand prior to interaction with it,

may suggest little in the way of performance expectations that could be mismatched by a

failure. Disappointment may thus be comparatively minimal, and evaluations of the brand

may change only negligibly as a result of the failed engagement.

2.2 Two rival explanations: “Love is blind” versus “Love becomes hate”

When customers are confronted with service failures of high-equity brands, two rival

explanations exist for the effects of brand equity on customers’ responses: the “love is blind”

versus the “love becomes hate” effect.

2.2.1 Love is blind

The “love is blind” effect argues that customers are more reluctant to hurt a valued

service partner or to terminate a meaningful relationship with high-equity brand (Lind & Tyler,

1988). These customers are more likely to forgive a service failure of a high-equity brand.

Hence, when the failed brand is a high-equity brand, the reduction of consumer satisfaction

will be smaller compared to that for a low-equity brand. It suggests that high-equity brands

provide an important buffer to service firms when service failures occur (Goodman et al.,

1995; Hess Jr et al., 2003; Kelley & Davis, 1994). This effect finds support in the literature on

assimilation bias (Herr, Sherman, & Fazio, 1983) and interpretation bias (Ahluwalia, 2000).

performance will be minimized or assimilated by the consumer adjusting his/her perception of

the product so as to be more consistent with the expectations. In an ambiguous situation, an

assimilation bias leads customers to overlook or underweigh information that is inconsistent

with their positive priors because of their strong connection and trust with the firm.

Consequently, customers of high-equity brands are less likely to feel unhappy by a service

failure. In order to maintain consistency between their positive priors and the current

perceptions of being involved in a service failure, customers may reduce the weight and the

spillover effects of the inconvenience occurred by high-equity brand. Because of these

cognitive biases, they are more likely to forgive a service failure by a high-equity brand.

In addition, customers of high-equity brands may feel reluctant to hurt a valued exchange

partner with whom they feel connected and whom they trust. For those customers, the

connections with high-equity brands are so important that they become reluctant to hurt the

firm because, by doing so, they create negative reflection of their self-esteem and how they

define themselves (Bhattacharya, Rao, & Glynn, 1995).

2.2.2 Love becomes hate

The “love becomes hate” effect posits that a high-equity brand’s favorable associations

lead customers to expect strong utilitarian benefits (Chandon, Wansink, & Laurent, 2000). A

failure by such a brand may engender particularly keen disappointment. When this occurs, a

performance disruption. This, in turn, may tarnish the consumer’s view of the formerly

admired brand. As such, a service failure by a high-equity brand represents a sharper contrast

with the customers’ expectations, and as result customers see a service failure as an act of

betrayal and result in more negative satisfactions and emotions (Robinson, 1996).

In this study, this explanation suggests that customers experience more dissatisfaction

from high-equity brand than low-equity brand in service failure contexts. This effect finds

support in the literatures on contrast effect (Herr et al., 1983). When expectations are not

matched by actual product performance, contrast theory suggests that the surprise effect or

contrast between expectations and outcome will cause the consumer to exaggerate the

difference between the what the product delivered and what was expected from the product,

i.e., if the objective performance of the product fails to meet a customer’s expectations, the

customer will evaluate the product less favorably than if he/she had no prior expectations of it.

Contrast is thus the opposite of assimilation. Since a high-equity brand’s favorable

associations lead customers to expect strong benefits, customers have higher expectations

about high-equity brand service than they believe they deserve. Being involved in a service

failure sharply contrasts with their expectations, and may result in more negative responses

(Brockner, Tyler, & Cooper-Schneider, 1992). A similar contrast effect has been observed in

the information processing literature, when individuals face extreme examples that conflict

In addition, customers of high-equity brands are more likely to feel betrayed than

customers of low-equity brands after service failure. Because of high-equity brand, customers

have more confidence in a firm, a service failure may generate feelings of broken trust and

will therefore be viewed as an act of betrayal (Robinson, 1996). A feeling of betrayal will lead

customers to be even more dissatisfied.

2.3 Firm’s controllability over failure

When services or products fail, people tend to engage in causal attribution (Weiner,

2000). Causal attribution theory suggests that consumers make inferences about the causes of

failure in the delivery of services (Heider 1958). These inferences have three dimensions

(Weiner 1985, 1986): locus of causality, stability and control. Locus of causality refers to

whether the consumer believes the cause of the service failure is related to the firm or to the

consumer. Stability is the extent to which a cause is viewed as temporary (expected to vary

over time), or predictable and permanent (expected to persist over time). Control attribution

involves the consumers’ belief about whether the firm could prevent a failure from occurring,

or alternatively it is the situation that forces the firm to follow a certain course of action.

Heider (1958) argued that consumers often use consistency principles to form attributions. An

excellent service organization should have less tolerance for stable failures. Thus, consumers

who have experienced excellent quality past service performance are less likely to make

less likely to attribute failures to stable causes, and they can be very beneficial for a firm

(Hess et al. 2003; Bagozzi et al. 2002). In this study the focus is restricted to control

attributions because they are thought to affect customer satisfaction toward a firm after

service failures (Folkes, 1984).

Control attribution deals with the perception that the firm could have controlled the

outcome (Hui, Tse, & Zhou, 2006; Weiner, 1985, 2000). If a failure is seen to be partly

attributable to a customer, or if a service firm's controllability over the failure is ambiguous,

the negative effect is lessened. Conversely, if a firm is seen as having had control over a

failure but did not prevent it, then customer reactions tend to be highly negative (Sunmee C &

Mattila, 2006). Formally, the attributions of a firm’s controlling ability are defined as

customer assessment of the degree to which the firm had control over a service failure and can

be blamed for its occurrence (Folkes, 1984).

The greater the perception of past service quality, the more likely consumers will

attribute high levels of competence and effort to avoid service failures to the service

organization (Narayandas 1998). As Hess et al. (2003) find, when a service failure occurs in

the context of high-quality past service performance, consumers are likely to infer that the

organization is highly competent and had little control over the failure, which would

2.4 Negative emotions

The literature on consumer behavior (Folkes 1988; Oliver & DeSarbo 1988; Spreng et al.

1996; Oliver 1997) suggests that individuals’ emotional responses to a service failure are

influenced by their causal explanation for the failure and that causal attributions about the

problem imply negative affective reactions. Specifically, it is argued that consumers express

more negative emotions (e.g. anger) after a service failure when the firm has control over the

problem.

This attribution–emotion relationship is also consistent with Bagozzi et al. (1999)

contribution from Cognitive Appraisal Theory. These authors point out that “emotions arise in

response to appraisals one makes for something of relevance to one’s wellbeing” (p. 185). In other words, it is not the service failure that creates the emotions, but rather the evaluations

that individuals make about the causes of the problems in the service. Additionally, several

empirical studies from other research areas, such as customer satisfaction (Mattila & Wirtz

2000; Oliver et al. 1997) and perceived justice with service recovery (Schoefer & Ennew

2005; Chebat & Slusarczyk 2005), provide support for the argument that cognitive elements

explain individuals’ emotions.

Therefore, the sequence of events after a service failure would be as follows: first the

customer makes attributions about the control of the causes of the service failure; then, the

subsequently will have a negative effect on satisfaction. In this study, customer negative

emotions are the first dependent variable.

2.5 Satisfaction Reduction

Consumer satisfaction has been discussed for several decades since Cardozo (1965) first

brought it up, and has various definitions in the literature. From a consumer’s perspective,

satisfaction represents a pleasurable consumption experience. It can influence a consumer’s

attitude towards a product and his intention to repurchase (R. L. Oliver, 1980). From a firm’s

perspective, satisfaction considerably contributes to the increase of its profitability. Research

has supported the existence of a positive relationship between customer satisfaction and

financial performance (Anderson, Fornell, 1997).

Customer satisfaction could be characterized as an evaluative judgment, with an

evaluation being made between expectation and product or service performance, after a

purchase has been completed (R. L. Oliver, 1980). Expectancy-disconfirmation theory is one

of the most influential topics in customer satisfaction studies (Zwick, Pieters, & Baumgartner,

1995), and in which consumer satisfaction can be specified as a function of initial standard

judgment which is compared to the level of perceived performance (Westbrook & Oliver,

1991). Consumers are assumed to assess a product before actually purchasing it. If

performance exceeds expectation, a positive disconfirmation will be expected and people will

disconfirmation when performance does not meet their expectations (Zwick et al., 1995).

Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals will adopt a dissonance reduction

strategy if they experience disconfirmation consumption (Tse & Wilton, 1988). People may

distort their cognition of how the service is performed and assimilate their judgments into

their initial expectations if they don’t want to admit the difference between expected and

actual experience (Anderson, 1973). When consumers experience dissonance after

consumption, they will align their assessments with their expectations.

Maxham & Netemeyer (2002) examined overall firm satisfaction as a customer’s

cumulative satisfaction after multiple experiences, transactions and encounters with a service

organization (Maxham & Netemeyer, 2002; Smith & Bolton, 1998). Since some customers

may view a service failure as a single specific experience which may result in slight

differences in overall firm satisfaction, this study examines two kinds of satisfaction

constructs: overall satisfaction before a service failure, and satisfaction after service failure.

The difference between the satisfaction based on the past experience and the consumer

satisfaction after service failure as satisfaction reduction is used, to see the effect of a single

service failure. This is the dependent variable in this study.

2.6 Patronage Reduction

Satisfaction literature strongly supports the idea that increased satisfaction with a service

same service provider (Harris, Grewal, Mohr, & Bernhardt, 2006). After service failure,

customers dissatisfaction and negative emotions should influence customers’ intentions and

behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001), such as the intent to

repurchase from the firm.

In this section, we examine complaint behavior examined in service failure literature

(Singh, 1988). i.e. patronage reduction. Customers can remove the benefits that their future

patronage would have generated. More specifically, patronage reduction is defined as a

customer’s efforts to reduce the frequency of his or her visits, spend less per visit, and to

frequent competitors more intensively (Wulf et al., 2001). Customer could decide to avoid a

firm because he or she does not want to repeat a negative experience.

2.7 Hypotheses

In this research, it is hypothesized that the “love is blind” versus the “love becomes hate”

effects are contingent upon the attributions made by customers about a firm’s ability to

control the service failure. Controllability attributions reflect the customers' beliefs that the

service firm could have prevented the failure (Folkes, 1984; Hamilton, 1980; Hess Jr et al.,

2003; Weiner, 2000). Attributions about a firm’s controllability are defined as customers’

judgments of the degree to which the firm had control over a service failure and can be

blamed for its occurrence (Folkes, 1984).

effect explains the influence of brand equity on customer responses to service failures.

Consistent with the logic supporting this effect, customers of high-equity brands, compared to

low-equity brands, experience smaller satisfaction reductions for two reasons. First, their

perceptions of high-equity brands bias the way they assimilate and interpret information

related to the service failure. For high-equity brands, customers overlook or reduce the effect

of the inconvenience associated with an uncontrollable service failure. Second, dissatisfaction

and negative images seem contrary to maintaining a strong and positive psychological

connection, especially when the service failure is beyond the control of the firm. In this

context, customers of high-equity brands experienced smaller satisfaction reductions for a

firm they trust and with which they strongly identify. In addition, when customers believe that

the firm did not have the ability to do anything, or when external forces caused the failure

(Folkes et al., 1987), their negative emotions are less intense (Folkes, 1984). Last, patronage

reduction is defined as a customer’s efforts to reduce the frequency of his or her visits, spend

less per visit, and to frequent competitors more intensively (Wulf et al., 2001). However,

when attributions of low controllability are made, customers of high-equity brand may feel

reluctant to hurt a valued exchange partner to whom they feel connected and in whom they

trusted. Then:

Hypothesis 1a: When customers attribute a service failure to a low controllable

than toward low-equity brands (i.e., “love is blind” effect).

Hypothesis 1b: When customers attribute a service failure to a low controllable

cause, their satisfaction reductions after a service failure (compared to satisfaction before a service failure) will be smaller for high-equity brands than for low-equity brands (i.e., “love is blind” effect).

Hypothesis 1c: When customers attribute a service failure to a low controllable

cause, their patronage reductions will be significantly smaller for high-equity brands than for low-equity brands (i.e., “love is blind” effect).

On the other hand, when customers infer that a firm had control over the service failure;

the “love becomes hate” effect explains the effect of service failures by high-equity brands.

Compared to low-equity brands, customers of high-equity brands experience greater

satisfaction reduction for two reasons. First, customers of high-equity brands have higher

expectations about the service they believe they deserve, and therefore a controllable service

failure more sharply contrasts with their expectations. In addition, they are more likely to feel

betrayed by the actions of a high-equity brand than low-equity brand (Robinson, 1996). Also,

controllable service failures are likely to be viewed as grounds for anger because a deliberate

act is a more significant breach of trust for customers who have a strong belief in and

connections with the firm. When customers believe that the firm had the ability to do but

Formally:

Hypothesis 2a: When customers attribute a service failure to a high controllable

cause, their negative emotions toward high-equity brands will be significantly stronger than toward low-equity brands (i.e., “love becomes hate” effect).

Hypothesis 2b: When customers attribute a service failure to a high controllable

cause, their satisfaction reductions after a service failure (compared to satisfaction before a service failure) will be greater for high-equity brands than for low-equity brands (i.e., “love becomes hate” effect).

Hypothesis 2c: When customers attribute a service failure to a high controllable

cause, their patronage reductions will be significantly greater for high-equity brands than for low-equity brands (i.e., “love becomes hate” effect).

2.8 Research Framework

The major focuses of this study is to identify (1) the contingency effect of a firm’s

controllability and (2) the interaction between brand equity and firm’s controllability. The

Figure 3 Research Framework (1)

Depending on the attributions made about a firm’s controllability, this study posits that

customers experience a smaller or a greater reduction of satisfaction of high-equity brands

than do customers of low-equity brands. The two components of hypothesis 1 and 2 are

represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Research Framework (2)

Low Controllability High Controllability Satisfaction Reduction Low High

Low High Brand Equity

H1: “love is blind” H2: “love becomes hate”

Patronage Reduction Service

Failure Satisfaction Reduction

Negative emotions Firm’s Controllability over failure H1 H2 Brand Equity

Scenario design for service failure

Pre-test and modify Scales

Determine the sample size and analysis method

Execute the sampling process

Data collection

Design scenarios with the same service failure and different brand equity which combined with different firm’s

controllability.

Choose 10 participants for each scenario to make sure the efficiency of scenarios and scales.

Sample size would be 2 (brand equity: high and low) X 2 (firm’s controllability over failure: high and low). Participants of each cell are composed of nearly half male and half female.

Randomly assign each participant to a cell.

Collect 294 samples in two service industries.

Chapter 3 Methodology 3.1 Conceptual Research Framework

3.2 Experimental Design

This study set out to determine how the attributions customers make about a firm’s

control over failures influences the effects of brand equity on customers’ responses, when they

are confronted with service failures. To increase generalizability, this study conducted

research in two service industries: hair salons and restaurants. Hair salons and restaurants

were ideal for the study because both are commonly used by and familiar to a wide range of

consumers, which should provide a diverse group of respondents who could meaningfully

complete the survey. In addition, both service industries maintain a strong presence in

high-equity brand contexts

Testing the model in these two services therefore should have implications for existing

theories and for managers of high-equity brands.

3.2.1 Experiment Procedure

This study constructed scenarios to manipulate the brand equity and firm’s controllability

over service failure across the two service industries with a completely randomized full

factorial design. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the four cells in a 2 × 2

(firm’s controllability over the failure: low or high × brand equity: high versus low)

Table 1 Experimental design

Firm’s Controllability Over the Failure

Brand Equity Low High Low

High

Low: partial blame to other customers or who to blame is unknown;

High: the firm is perceived to have had the ability to prevent the failure but did not.

Written scenarios were used to create the four experimental conditions in the two service

industries. A scenario methodology was chosen for the study, in which subjects were asked to

imagine themselves in the scenarios presented. Scenario methodology has been used in

previous studies of customer reaction to service failure. There is strong evidence that

individuals respond to an experimental scenario in the same manner as they would respond to

a similar, actual experience (Maxham & III, 2001).

Initially, respondents learned that they would participate in one study about the service

experiences. In the scenarios, participants were asked to recall an actual hair salon (restaurant)

where they received service before. In both service industries, participants were randomly

assigned to two brand equity conditions, to complete the brand equity scales and the customer

satisfaction scales depending on the quality of past experiences.

Respondents first read a short description of a firm. In the case of the hair salons,

respondents were told to imagine that they had already made an appointment to get their hair

cut. However, when they arrived on time, the respondents find out that they have to wait for

In the restaurant scenario, respondents were asked to imagine that they had already made

an appointment for dinner. Then the respondents subsequently learn that they have to wait for

35 minutes to become seated. Next, both groups of respondents read scenarios describing one

of two controllability manipulations. Last, respondents were asked to complete the customers’

satisfaction scales again after service failure in order to examine the intensity of their negative

emotions, and the degree of satisfaction reductions was analyzed. In addition, patronage

reduction was used to exam the customers’ response after service.

3.2.2 Stimulus Development

Manipulation of brand equity

To manipulate brand equity, the study selected some pictures for different brand equities.

There were three exclusive and luxurious hair salon pictures for a high-equity brand

manipulation and three pictures of university-affiliated haircut service for a low-equity brand

(Appendix A). In addition, this study provided a description about the service and the quality

of the hair salon corresponding to the pictures in order to induce customers to recall one hair

salon that he/she has been to (Appendix A). In this study, we used perceived quality, which is

one dimension of brand equity to do the manipulation check since it is the most obvious and

external concept to evaluate brand equity. Therefore, consistent with well-established

measures of brand equity (e.g., Aaker and Keller 1990; Smith and Park 1992), we considered

quality reflects a global brand evaluation (DelVecchio, Jarvis, Klink, & Dineen, 2007). For

the purpose of a manipulation check, participants were asked to report the name of the hair

salon he chooses and to complete the brand equity scale adapted from Yoo & Donthu (2001).

Examples included, “The likely quality of this hair salon is extremely high.” and “This hair

salon’s quality appears to be reliable.” (1 = “strongly disagree,” 7 = “strongly agree”). Results

supported the high- and low-equity brands’ intuitive designations. In addition, the pictures and

description that represents high equity was rated significantly higher on the brand-equity scale

than the low-equity hair salon brand. The results of the manipulation will be reported in

Chapter 4.

Manipulation of a firm’s controllability over failure

A service failure scenario was designed to stimulate participaants into an unsatisfactory

service experience due to an unnecessarily long wait. The respondents were randomly

assigned to two scenarios about the firm’s controllability over failure.

To manipulate the controllability variable, we depicted in two scenarios. Both scenarios

were that customers had to wait 35 minutes for their hair cuts even if they had already made

an appointment three days previously (occurrence of service failure). However, in a firm’s

high controllability over failure situation, the reason for making the customers wait was that

the salon forgot to make the appointment. In a low controllability scenario, failure happened

firm’s controllability over failure depends on how the participants attribute the service failure.

This study used the scale of attributions about the firm’s controllability developed by

Maxham and Netemeyer (2002). (e.g. “The service failure was entirely the organization’s

fault.”, on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree, to 7 = strongly agree)

3.3 Measurements

3.3.1 Brand Equity

The Scale of Brand equity adapted from Yoo & Donthu (2001) was used to check the

effect of the brand equity manipulation. It measures perceived quality of high- and low-equity

hair salon brands. The 7-point Likert scale was chosen. Seven points represents “strongly

agree”, and one point represents “strongly disagree.

Scale Items:

1. The likely service quality of this hair salon is extremely high. 2. The skill of hair stylist in this hair salon is extremely high. 3. The quality of this hair salon appears to be reliable.

3.3.2 Negative emotions

Respondents assessed the degree to which they would feel anger, shock, irritation

(Richins, 1997), regret, and betrayal. This scale has a reliability alpha of 0.883.

Scale Items:

1. I would feel very angry. 2. I would feel regret. 3. I would feel betrayed. 4. I would feel shocked. 5. I would feel irritated.

3.3.3 Satisfaction

The 7-points Likert scale was chosen. Seven points represents “strongly agree”, and one

point represents “strongly disagree. Following prior research we modified the words to fit this

study, and measured customer satisfaction after the service recovery on a three-item scale

(adapted from Maxham Ⅲ & Netemeyer (2002).

Scale Items:

1. On the whole, I am/was very satisfied with my experience with this/that service. 2. In general, I am/was happy with the service experience.

3. Overall, my positive experience outweighs/outweighed my negative experience with this/that service.

3.3.4 Patronage Reduction

Patronage Reduction was measured by a four-item, seven-point scale which was

used by Wulf et al.(2001).

Scale Items:

1. I spent less money at this business. 2. I stopped doing business with this firm.

3. I reduced frequency of interaction with the firm. 4. I took a significant part of my business to a competitor.

3.3.5 Firm’s Controllability Over Failure

Attributions about the firm’s controllability were measured with a three-item scale

developed by Maxham and Netemeyer (2002). This scale was based on semantic differential

items.

Scale Items:

1. This hair salon was entirely responsible for the problem that I experienced. 2. The problem that I encountered was solely this hair salon's fault.

3.4 Data Collection and Analysis Methods

First, an Independent-Sample T Test was employed to determine if brand equity (high vs.

low) and firm’s controllability over failure have significant differences under stimulus

manipulation. Then, ANOVA was used to determine the firm’s controllability over failure on

the effect of brand equity on the decline of satisfaction, and thus understand the influence of

moderator.

3.5 Pretest

A pilot study was conducted to test the validity and reliability of the questionnaire.

Researchers use this method to discover problems or misunderstandings in the design of the

experiment and then modify it before the official study. After our questionnaires failed and

were modified four times, the fifth edition of pilot study was successful.

The pretest was made by giving forty participants the experimental questionnaires,

telling them the research purpose was concerned with consumer behavior. There were twenty

male and twenty female participants. Twenty-two of the forty participants were students. The

reliability of customer satisfaction scales was 0.891, the reliability of the negative emotions

scales was 0.968, and the reliability of the patronage reduction scales was 0.924. All

reliabilities of scales were higher than 0.7. In addition, there was significant difference

between high-equity brand and low-equity brand (p<0.00). The difference between high and

Chapter 4 Research Analysis and Results

This chapter contains the analysis and the results of this study, including the background

of respondents, manipulation checks, reliability and validity of the results. A 2 (brand equity)

× 2 (firm’s controllability over failure) between-subjects experiment was conducted. Also, this

study conducted research in two service industries (hair salon and restaurant) to determine the

generalizability of our model. The type of service didn’t affect any dependent variables as we

expected. In other words, there was no significant difference between the service types.

However, since the scenarios are different in two service industries, this study discussed the

results separately, which has been used in previous studies of customer reaction to service

failure (DeWitt & Brady, 2003; Gremler & Gwinner, 2000 ). Therefore, this study first gave

the results of haircut scenario and then the results of restaurant scenario. Data analysis

techniques such as ANOVA, multi-comparison, and Independent-Sample T Test were

employed to test the hypotheses. The study used SPSS 12.0 to analyze the data.

4.1 Background of Participants

In the haircut scenario, from the total sample of 145 participants, 55.17% were students,

53.8% were female, 40% were between 21 and 25 years old, 57.93% have college degree,

39.31% have a graduate or higher degree, 35.86% have incomes between NT10,000 to

NT30,000.

51.2% were female, 42.4% were between 21and 25 years old, 61.8% have college degree,

37.1% have a graduate or higher degree, 47.6% have income less than NT10,000. The

demographics of all respondents are listed in Table 2.

Table 2 Demographics of Participants

Demographics Category Number of Participants Percentage Hair salon Restaurant Hair salon Restaurant

Male 67 73 46.2 48.8 Female 78 76 53.8 51.2 Gender Total 145 149 100.0 100.0 16~20 7 3 4.8 2.4 21~25 58 62 40 42.4 26~30 51 41 35.1 28.2 31~35 16 11 11 7.6 36~40 7 13 4.83 8.8 41~45 4 5 2.76 2.9 46~50 5 5 2.9 2.9 Over 51 2 9 1.38 6 Age Total 145 149 100.0 100.0 Senior high 4 2 2.76 1.3 College 84 92 57.93 61.8 Graduate upward 57 55 39.31 37.1 Education Degree Total 145 149 100.0 100.0 Students 80 89 55.17 60.0 Others 65 60 44.83 40.0 Occupation Total 145 149 100.0 100.0 Less than 10,000 47 70 32.41 47.6 10,001~30,000 52 44 35.86 30.0 30,001~50,000 36 20 24.83 13.5 50,001~70,000 7 9 4.83 6.5 70,001~90,000 2 5 1.38 1.8 More than 90,001 1 1 0.69 .6 Income Total 145 149 100.0 100.0

4.2 Reliabilities

In both service industries, the reliabilities of all constructs in this research were tested

with Cronbach’s alpha. Table 3 shows that reliabilities are all above 7 across all factors,

which indicate the high internal consistency of each item of the same factor.

Table 3 Reliability Statistics

Factors Cronbach's Alpha N of Items

Hair salon Restaurant

Brand equity .937 .946 3

Controllability .938 .940 3

Satisfaction .895 .927 3

Satisfaction after failure .924 .938 3

Negative emotions .883 .936 5

Patronage Reduction .918 .952 4

4.3 Manipulation Check

4.3.1 Manipulation Check of brand equity

In the haircut scenario, there were 73 participants in the high-equity brand and 72 in the

second group, with the low-equity brand. An Independent-Sample T Test was conducted to

investigate the differences of brand equity between the two groups. It is shown that the brand

equity of low-equity brand is significant lower than high-equity brand (t-statisitcs = -8.336, p

Table 4 Manipulation Check of Brand Equity

Brand Equity N Mean Std. Deviation T Sig.(2-tailed)

Low 72 4.0926 1.03797 Hair salon High 73 5.5525 1.07039 -8.336 .000* Low 72 3.7725 .99498 Restaurant High 77 6.0863 .76316 -17.011 .000*

4.3.2 Manipulation Check of Controllability

There were 73 participants in the low controllability group, and 72 in the high

controllability group. An Independent-Sample T Test was conducted to investigate the

difference of brand equity between the two groups. It was shown that the brand equity of low

controllability is significantly lower than for high controllability (t-statisitcs = -6.551, p <

0.000). The results are showed in Table 5.

Table 5 Manipulation Check of Controllability

Controllability N Mean Std. Deviation T Sig.(2-tailed)

Low 73 3.6758 1.35739 Hair salon High 72 5.0880 1.23460 -6.551 .000* Low 81 2.7500 1.30844 Restaurant High 68 5.4472 1.17964 -14.080 .000* 4.4 Analysis of Results

After confirming all manipulation checks and the reliability of the scales, ANOVA was

applied to test the hypotheses.

4.4.1 Service Industries

was no significant difference between the service industries (p>0.05). See as Tables 6, 7 and 8.

However, since the scenarios in two service industries are different, this study discussed the

results separately, which has been used in previous studies of customer reaction to service

failure (DeWitt & Brady, 2003; Gremler & Gwinner, 2000 ).

Table 6 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

Dependent Variable: negative emotions

Source

Type III Sum

of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 258.068a 7 36.867 41.240 .000 Intercept 5472.628 1 5472.628 6121.723 .000 SI .143 1 .143 .160 .690 BE 1.376 1 1.376 1.539 .216 CON 203.763 1 203.763 227.931 .000 SI * BE .006 1 .006 .007 .935 SI * CON 13.027 1 13.027 14.572 .000 BE * CON 32.635 1 32.635 36.506 .000 SI * BE * CON .002 1 .002 .002 .965 Error 255.675 286 .894 Total 5891.480 294 Corrected Total 513.743 293 a. R Squared = .502 (Adjusted R Squared = .490)

Note: BE represents Brand Equity; CON represents Controllability; SI represents Service Industries.

Table 7 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Reduction

Source

Type III Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 301.482a 7 43.069 53.751 .000* Intercept 1267.742 1 1267.742 1582.187 .000* SI 1.127 1 1.127 1.407 .237 BE 5.293 1 5.293 6.606 .011* CON 230.397 1 230.397 287.544 .000* SI * BE 6.627 1 6.627 8.271 .004* SI * CON 5.505 1 5.505 6.871 .009* BE * CON 47.831 1 47.831 59.695 .000* SI * BE * CON 2.639 1 2.639 3.293 .071 Error 229.160 286 .801 Total 1755.050 294 Corrected Total 530.642 293 a. R Squared = .568 (Adjusted R Squared = .558)

Note: BE represents Brand Equity; CON represents Controllability; SI represents Service Industries.

Table 8 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

Dependent Variable: Patronage Reduction

Source

Type III Sum

of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 274.569a 7 39.224 29.147 .000* Intercept 5095.501 1 5095.501 3786.389 .000* SI .619 1 .619 .460 .498 BE 90.970 1 90.970 67.598 .000* CON 131.410 1 131.410 97.648 .000* SI * BE 1.500 1 1.500 1.114 .292 SI * CON 27.733 1 27.733 20.608 .000* BE * CON 9.633 1 9.633 7.158 .008* SI * BE * CON 3.325 1 3.325 2.471 .117 Error 384.882 286 1.346 Total 5643.500 294 Corrected Total 659.452 293 a. R Squared = .416 (Adjusted R Squared = .402)

Note: BE represents Brand Equity; CON represents Controllability; SI represents Service Industries.

4.4.2 Brand Equity with Firm’s Controllability over failure and Negative Emotions

Hypothesis 1a indicated that when attributions of low controllability are made, customers

will experience weaker negative emotions with high-equity brands than with low-equity

brands. Hypothesis 2a speculated that when attributions of high controllability are made,

customers will experience stronger negative emotions with high-equity brands than with

low-equity brands.

contains the results of ANOVA and shows that a firm’s controllability could significantly

affect customers’ negative emotions (p <0.01). Further, the interaction between brand equity

and a firm’s controllability over failure is given in Table 10 (also see Figure 5). When

attributions of a firm’s low controllability over failure are made, there were significant

differences between high-equity and low-equity brands (p < 0.01); the same results happened

when attributions of a firm’s high controllability are made.

Table 11 shows that after a service failure, when attributions of low firm’s controllability

are made, customers’ negative emotions are significantly weaker with high-equity brands than

with low-equity brands. Hypothesis 1a is supported (p <0.05). It also confirms that when

attributions of a firm’s high controllability are made, customers’ negative emotions are

significantly stronger with high-equity brands than with low-equity brands. Hypothesis 2a

was supported (p <0.05). Both service industries support hypothesis 1a and hypothesis 2a.

‧ Hair salon

Table 9 Descriptive Statistics (Hair salon) Controllability

Low High

Mean (Std. Deviation) N Mean (Std. Deviation) N

Low-equity brand 4.12 (.699) 37 4.70 (.871) 35

Table 10 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Hair salon)

Dependent Variable: Negative Emotions

Source

Type III Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 73.117a 3 24.372 35.186 .000* Intercept 2738.338 1 2738.338 3953.338 .000* BE .594 1 .594 .858 .356 CON 56.339 1 56.339 81.337 .000* BE * CON 15.929 1 15.929 22.997 .000* Error 97.666 141 .693 Total 2913.240 145 Corrected Total 170.782 144 a. R Squared = .428 (Adjusted R Squared = .416)

Table 11 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)

Dependent Variable: Negative Emotions

(I) Group (J) Group Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig.

2 -.5839* .19624 .003 3 .7911* .19484 .000 1 4 -1.1189* .19350 .000 1 .5839* .19624 .003 3 1.3751* .19756 .000 2 4 -.5350* .19624 .007 1 -.7911* .19484 .000 2 -1.3751* .19756 .000 3 4 -1.9101* .19484 .000 1 1.1189* .19350 .000 2 .5350* .19624 .007 4 3 1.9101* .19484 .000

Based on observed means.

The error term is Mean Square (Error) = .693. *. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level. The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

Note: 1 represents low brand equity and low controllability; 2 represents low brand equity and high controllability; 3 represents high brand equity and low controllability; and 4 represents high brand equity and high controllability.

Figure 5 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Hair salon)

5.24

4.70

4.12

‧ Restaurant

Table 12 Descriptive Statistics (Restaurant) Controllability

Low High

Mean (Std. Deviation) N Mean (Std. Deviation) N

Low-equity brand 3.67 (1.294) 39 5.08 (.995) 33

High-equity brand 2.85 (1.073) 42 5.61 (.673) 35

Table 13 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Restaurant)

Dependent Variable: Negative emotions

Source

Type III Sum

of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 183.464a 3 61.155 56.120 .000* Intercept 2734.396 1 2734.396 2509.267 .000* BE .790 1 .790 .725 .396 CON 161.450 1 161.450 148.157 .000* BE * CON 16.716 1 16.716 15.339 .000* Error 158.009 145 1.090 Total 2978.240 149 Corrected Total 341.473 148 a. R Squared = .537 (Adjusted R Squared = .528)

Table 14 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)

Dependent Variable: Negative emotions

(I) Group (J) Group Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig.

2 -1.4182* .24691 .000 3 .8190* .23214 .001 1 4 -1.9448* .24306 .000 1 1.4182* .24691 .000 3 2.2372* .24283 .000 2 4 -.5266* .25329 .039 1 -.8190* .23214 .001 2 -2.2372* .24283 .000 3 4 -2.7638* .23892 .000 1 1.9448* .24306 .000 2 .5266* .25329 .039 4 3 2.7638* .23892 .000

Based on observed means.

The error term is Mean Square (Error) = 1.090. *. The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

Note: 1 represents low brand equity and low controllability; 2 represents low brand equity and high controllability; 3 represents high brand equity and low controllability; and 4 represents high brand equity and high controllability.

Figure 6 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Restaurant) 4.4.3 Brand Equity with Firm’s Controllability over failure and Satisfaction reduction

This part of the project attempts to establish whether there is an interactive effect

between brand equity and firm’s controllability over failure on the satisfaction reduction.

Hypothesis 1b speculated that when attributions of low controllability are made,

customers will experience smaller satisfaction reductions with high-equity brands than with

low-equity brands (i.e. the “love is blind” effect). Hypothesis 2b showed that when

attributions of high controllability are made, customers will experience greater satisfaction

reductions with high-equity brands than with low-equity brands (i.e. the “love becomes hate”

effect).

Table 15 shows the descriptive statistics of brand equity and controllability. Table 16

5.08

3.67

5.61

shows the results of ANOVA and that firm’s controllability could significantly affect the

reduction of customers’ satisfaction (p <0.01). Table 16 also shows the interaction between

brand equity and firm’s controllability over failure (see Figure 7 also). When attributions of

low controllability are made, there were significant differences in the reduction of satisfaction

between high-equity and low-equity brands (p < 0.01); the same results were obtained when

attributions of high firm’s controllability over failure were made (p < 0.01).

Table 17 shows that after a service failure, when attributions of low firm’s controllability

are made, the reduction of customers’ satisfaction is significantly lower with high-equity

brands than with low-equity brands. Hypothesis 1b was supported (p <0.05). It also confirms

that when attributions of high firm’s controllability over failure are made, the reduction of

customers’ satisfaction is significantly higher with high-equity brands than with low-equity

brands. Hypothesis 2b was supported (p <0.05). Both service industries support hypothesis 1b

and hypothesis 2b.

‧ Haircut

Table 15 Descriptive Statistics (Hair salon) Controllability

Low High

Mean (Std. Deviation) N Mean (Std. Deviation) N

Low-equity brand 1.59 (.609) 37 2.48 (1.291) 35

Table 16 Tests of Brand Equity and Controllability (Hair salon)

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Reduction

Source

Type III Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 95.880a 3 31.960 39.016 .000* Intercept 591.095 1 591.095 721.584 .000* BE .036 1 .036 .044 .834 CON 81.531 1 81.531 99.530 .000* BE * CON 13.860 1 13.860 16.920 .000* Error 115.502 141 .819 Total 803.444 145 Corrected Total 211.382 144 a. R Squared = .454 (Adjusted R Squared = .442)

Table 17 Multiple Comparisons of Brand Equity and Controllability (LSD)

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Reduction

(I) Group (J) Group Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig.

2 -.8816* .21341 .000 3 .6502* .21188 .003 1 4 -1.4685* .21043 .000 1 .8816* .21341 .000 3 1.5317* .21485 .000 2 4 -.5869* .21341 .007 1 -.6502* .21188 .003 2 -1.5317* .21485 .000 3 4 -2.1186* .21188 .000 1 1.4685* .21043 .000 2 .5869* .21341 .007 4 3 2.1186* .21188 .000

Based on observed means.

The error term is Mean Square (Error) = .819. *. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Note: 1 represents low brand equity and low controllability; 2 represents low brand equity and high controllability; 3 represents high brand equity and low controllability; and 4 represents high brand equity and high controllability.

Figure 7 Interactions between Brand Equity and Controllability (Haircut)

‧ Restaurant

Table 18 Descriptive Statistics (Restaurant) Controllability

Low High

Mean (Std. Deviation) N Mean (Std. Deviation) N

Low-equity brand 1.33 (.831) 39 2.38 (1.077) 33 High-equity brand 0.90 (.542) 42 3.95 (1.061) 35 1.59 0.94 2.48 3.06

Table 19 Tests of Brand Equity and Controllability (Restaurant)

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Reduction

Source

Type III Sum

of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Corrected Model 205.445a 3 68.482 87.351 .000* Intercept 678.688 1 678.688 865.691 .000* BE 11.997 1 11.997 15.302 .000* CON 155.039 1 155.039 197.758 .000* BE * CON 36.819 1 36.819 46.964 .000* Error 113.678 145 .784 Total 951.667 149 Corrected Total 319.123 148 a. R Squared = .644 (Adjusted R Squared = .636)

Table 20 Multiple Comparisons (LSD)(Restaurant)

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction Reduction

(I) Group (J) Group Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig.

2 -1.0505* .20943 .000 3 .4286* .19690 .031 1 4 -2.6190* .20616 .000 1 1.0505* .20943 .000 3 1.4791* .20597 .000 2 4 -1.5685* .21484 .000 1 -.4286* .19690 .031 2 -1.4791* .20597 .000 3 4 -3.0476* .20265 .000 1 2.6190* .20616 .000 2 1.5685* .21484 .000 4 3 3.0476* .20265 .000

Based on observed means.

The error term is Mean Square (Error) = .784. *. The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

Note: 1 represents low brand equity and low controllability; 2 represents low brand equity and high controllability; 3 represents high brand equity and low controllability; and 4 represents high brand equity and high controllability.