Ethical and Effective?

Yi-Hui Huang

ABSTRACT. The purpose of this paper is to explore two questions: (1) Is symmetrical communication in public relations practice inherently ethical? (2) Does symmetrical communication contribute to public rela-tions effectiveness and organizational effectiveness? Three surveys are undertaken to test seven research hypotheses for the purpose of cross-validating research findings. The results suggest that symmetrical communication is inher-ently ethical. Moreover, symmetrical communication indeed contributes to several performance measures, which include positive market performance, overall organizational effectiveness, conflict resolution, crisis management, favorable organizational reputation, and positive media exposure, with the last two measures only partially supported.

KEY WORDS: symmetrical communication, public relations, ethical communication, public relations effec-tiveness, organizational effectiveness

Purpose

Public relations professionals, in their roles as orga-nizational boundary spanners and communication

managers (Grunig and Hunt, 1984; Grunig et al., 1992), often help organizations manage their re-sponses when communicating with their constitu-encies in order to cope with rapid changes in the environment (White and Dozier, 1992). In such roles, however, public relations has sometimes been branded an unethical practice on two accounts. First, research has revealed a ‘‘personal influence’’ pattern in public relations practice in an international setting (Grunig et al., 1995) which has been perceived as being asymmetrical and unethical (Grunig and Gru-nig, 1996). Second, it has been asserted that public relations are a way in which people attempt to exert control over their symbolic environment. Miller (1989), for example, argues that persuasion and public relations are ‘‘Two ‘Ps’ in a Pod’’ – that communi-cation and persuasion are associated inextricably.

Several scholars, adopting a rhetorical perspective, have argued against the idea that persuasion might be inherently unethical (Heath, 1992a). For example, Nelson (1994) raised the question: When is persua-sion unethical? Bivins (1987) distinguished between the ethics of counselors as symmetrical practitioners and advocates as asymmetrical practitioners. He suggested that advocacy leads public relations prac-titioners to act only in the client organization’s self-interest, but that an ethical standard can be met if a public relations practitioner reveals the motives (reasons) that underlie his or her asymmetrical publicity. Likewise, Heath (1992b, pp. 46–57) wrote that persuasion could be ethical if it meets three rhetorical principles: standards of truth and knowl-edge, good reasons, and perspectivist criticism. The debate on ‘‘when is persuasion unethical’’ holds open the possibility of the coexistence of persuasion and ethical communication.

In response to the claim of unethical implications, the literature of public relations suggests the need for two-way symmetrical communication between Yi-Hui Huang is a professor at the Department of Advertising of

the National Chenchi University in Taiwan. She holds a Ph.D. of mass communication from the University of Maryland, USA. Dr. Huang’s research interests include communication management, public relations research, conflict management and cross-cultural communications. She won the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program Award for 2003–2004 and joined the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School as a visiting scholar. Her research has been awarded internationally and domestically, which included the PRIDE Awards in 2001 (the Best Article Award in Public Relations Scholarship, awarded by the National Communication As-sociation, USA), five Top Paper Awards in various inter-national conferences, and the Distinguished Research Award given by the National Science Council in Taiwan in 2002.

Journal of Business Ethics 53: 333–352, 2004.

organizations and their constituencies (Anderson, 1992; Grunig, 1992b; Grunig and Grunig, 1992; Huang, 1994; Pavlik, 1989). Grunig and Hunt (1984) defined communication as symmetrical when the public has some effect on it; that is, when the com-municator is willing to initiate changes from his or her side. Grunig (1989) and Grunig and Grunig (1992) assert that the two-way symmetrical communication model provides the normative ideal and will result in effective public relations for most situations.

Symmetrical communication arouses more fer-vent debate than most other concepts in the generic theory of public relations. This debate has two facets: (1) The nature of symmetrical communication. Is symmetrical communication inherently ethical? Several scholars contend that the personal-influence model can be practiced ethically or unethically; what makes the difference is the practitioner’s ‘‘world-view’’ (Grunig, 2001, p. 26). The extent to which ‘‘symmetry’’ is employed determines whether the practice of public relations is ethical or unethical; extensive use of symmetrical communication is considered ethical (see Grunig, 1992a). If this posi-tion is accepted, then the next logical and important question would be: Is symmetrical communication actually inherently ethical?

(2) The effect of symmetrical communication. Here there are three main problems:

(a) Effectiveness with activists. Although the litera-ture appears to support the use of symmetrical communication between organizations and activists (Anderson, 1992; Grunig, 1992b; Huang, 1994; Pavlik, 1989), this support comes primarily from negative evidence showing that the three most commonly used models of public relations – press agentry, public information, and two-way asym-metrical – appear to be ineffective in dealing with activism (Huang, 2001a). Little evidence has dem-onstrated the direct, positive effects of symmetrical communications.

(b) The ‘‘one-best style’’. Leichty and Springston (1993) questioned the effectiveness of an organiza-tion consistently using the same public relaorganiza-tions model across stakeholders over time. They con-tended that public relations models should be mea-sured at ‘‘the relational level’’ rather than being aggregated ‘‘across publics and relational stages and globally characterized as an organization’s overall public relations practice’’ (p. 334).

(c) Is symmetrical communication normative or both normative and descriptive? Sun (1994) and Van der Meiden (1993) argued that the two-way symmetrical model only prescribes what an organization should do, without actually representing the reality. Like-wise, Sun (1994) pointed out the slim possibilities for an organization to actually practice a symmetrical model. Murphy (1991), equating the two-way sym-metrical communication model to a pure cooperation model in game theory, held that symmetrical com-munication is difficult to find in the real world. Along the same lines, Van der Meiden (1993) criticized a symmetrical worldview as unrealistic, inasmuch as it disconnects an organization’s ‘‘communicative activ-ities from its immediate or removed interests’’ (quoted in Grunig and Grunig, 1996, p. 15).

Reflecting the twofold discussion above, the purpose of this paper is twofold: (1) to explore the nature of symmetrical communication – whether or not symmetrical communication is inherently ethi-cal, and (2) to investigate the effects of symmetrical communication in terms of public relations effec-tiveness and organizational effeceffec-tiveness.

Conceptualization

This section will first conceptualize the notions of symmetrical communication and ethical communi-cation. The relationship of these two concepts will then be explored, followed by an investigation of the effects of symmetrical communication. The research proposition and research hypotheses are developed in the course of the conceptualization.

Symmetrical communication

Grunig and Hunt (1984) defined public relations as ‘‘the management of communication between an organization and its publics’’ (p. 6). Two approaches can be taken. Organizations with a symmetrical worldview see communication as interactive behavior in which two or more systems construct cognitions and attitudes together so that they behave in ways that are either ‘‘synergistic or symbiotic’’ (Grunig, 1989, p. 13). The following concepts underlie the symmetrical worldview: holism, inter-dependence, an open system, a moving equilibrium, equality, autonomy, innovation, responsibility,

conflict resolution, and communication as a path to understanding (Grunig and White, 1992). On the other hand, organizations with asymmetrical worldviews see communication as a tool with which to change the cognitions, attitudes, or behaviors of another person, organization, or system. Concepts germane to the asymmetrical worldview include internal orientation, closed system, and efficiency (Grunig and White, 1992).

Thus, an organization’s intent to initiate internal change is the key to symmetrical communication. If an organization is willing to make changes from its side, or actually has done so already, then the the-oretical presuppositions underlying the symmetrical worldview have been achieved.

Ethical communication

Ethical communication is defined as involving the following three concepts: teleology, disclosure, and social responsibility.

Teleology

Debate on ethical theories falls into two camps: utilitarianism or teleology on the one hand and Kant’s categorical imperative or deontology on the other. Grcic (1989) explained the differences be-tween teleology and deontology:

Teleological theories hold that the ultimate criterion of moral goodness is either the sum total of good over evil consequences that the action brings about or whether it promotes individual functioning and development. A teleologist holds that an action is moral if it is a means to the appropriate moral good. A deontological approach, however, holds that the morality of an action is not primarily determined by its consequences but by certain intrinsic features of the intention or mental aspect of the contemplated action. A deontologist emphasizes doing one’s duty and the nature of our motives and intentions, not the conse-quences that may result from our actions. (p. 4) In a similar manner, Grunig and Grunig (1996) equated teleological theories as consequentialist theories and deontological theories as non-conse-quentialist theories. In other words, public relations practitioners should consider the impact of their communication behaviors on their colleagues, cli-ents, organizations, and the larger society, but should

also follow deontological rules to be honest, truthful, and sincere when communicating (also see Reinsch, 1990).

Disclosure

According to Bok (1989), having secrets and having access to information gives one more power. Dis-closure, on the other hand, facilitates power sym-metry. As indicated above, Bivins (1987) pointed out that advocacy has been the public relations practitioner’s primary job. Advocacy, by driving public relations practitioners to act purely in the client organization’s interest, encourages an imbal-ance of power between the organization and the public, with the consequent opportunities for unethical activity. Bivins (1987) suggested that revealing the motives (reasons) of asymmetrical communication can secure ethical standards. In essence, the concept of disclosure is related to the basic right that Sullivan advocates human beings should have: possessing information and participat-ing in decision-makparticipat-ing (quoted in Grunig and Grunig, 1996, p. 22).

The obligation to preserve secrets is repeatedly set forth, often with a ‘‘ritualistic’’ tone, in professional codes of ethics (Bok, 1989). Bok offers an explana-tion for professional secrecy, stating that the premises are not usually separated and evaluated in the con-text of individual cases or practice. Adopting a dif-ferent perspective, Jaksa and Pritchard (1994) caution against ‘‘blind acceptance’’ of professional codes and legal determinations, arguing that they should give way to moral considerations (p. 203). Social responsibility

Scholars maintain that public relations practitioners should perform their social roles and functions in a socially responsible manner (Grunig and Grunig, 1992). In this sense, public relations professionals, spanning the boundaries between organizations and the outside world, would be the right actors to take into account the impact (or consequences) of all public relations activities on their publics and to discharge corporate social responsibility for an organization.

Applying Donaldson’s concepts of ‘‘minimal duty’’ and ‘‘maximal duty’’ (1989) to the field of public relations, public relations professionals should meet the bottom-line standards of ‘‘minimal duty’’ for organizational stakeholders such as the commu-nity, employees, and consumers, and then further

endeavor to fulfill the ‘‘maximal duty’’ as an act of good corporate citizenship. He specified the ‘‘min-imal duty’’ for multinational corporate social responsibility as ‘‘enhancing the welfare of con-sumers and employees, respecting the rights and justice of the people in the society, and minimizing harm or other negative effects such as misuses of power or depletion of natural resources’’ (quoted in Amba-Rao, 1993, p. 5). The ‘‘maximal duty,’’ on the other hand, would be an act of good corporate citizenship, such as supporting Third World devel-opment programs or economic aid.

In a similar vein, Naor (1982) suggested that social responsibility satisfies social needs and promotes public welfare. Sethi (1975) also maintained that, in the highest phase of responsibility – social respon-siveness – a corporation takes anticipatory actions with a commitment towards social goals (Sethi, 1975, cited in Amba-Rao, 1993). In Carrol’s (1991) pyra-mid of corporate social responsibility, the highest level is ‘‘philanthropic responsibilities,’’ which sug-gests being a good corporate citizen, making con-tributions to the community, and improving its people’s quality of life. Donaldson’s (1989) notions of ‘‘minimal duty’’ and ‘‘maximal duty’’ correspond to the idea of ‘‘teleology’’ as suggested in Grunig and Grunig (1996), which emphasized that an organiza-tion should consider the impact of its communicaorganiza-tion behaviors on its constituencies and the larger society. On the other hand, the idea of ‘‘public interests’’ seems to be a focal concept in Naor’s (1982), Sethi’s (1975) and Carrol’s (1991) conceptualizations of so-cial responsibility. Moreover, ‘‘disclosure’’ is another aspect of communication ethics (Bok, 1989). I adopt these focal concepts in order to develop the measures of ethical communication used in this study.

The relationship between symmetrical communication and ethical communication

The public relations literature offers two opposing positions on the relationship between symmetrical communication and ethical communication. The first view postulates that ethical communication and symmetrical communication often coexist. For example, Grunig and his colleagues contended that the two-way symmetrical model reformulates public relations as a more ethical practice. Specifically, Grunig and Grunig (1996) held that ‘‘public relations

will be inherently ethical if it follows the principles of the two-way symmetrical model’’ (p. 40). They further wrote that it is possible to practice public relations both asymmetrically and ethically, but this combination is very difficult. Grunig and Grunig (1992) even contended that the two-way symmet-rical model avoids the dilemma of ethical relativism inasmuch as it specifies ethics as a process of public relations rather than as an outcome. Likewise, Pear-son (1989) noted, ‘‘it is a moral imperative to im-prove the quality of these communication relationships, that is, to make them increasingly dia-logical [symmetrical]’’ (quoted in Grunig and Gru-nig, 1996, p. 40). The empirical research actually demonstrates that the symmetrical presuppositions of an organization can contribute to achieving several ethical characteristics of public relations, such as the concerns of ethics and social responsibility, and the empowerment of public relations in the dominant coalition (Karlberg, 1996; Lauzen and Dozier, 1994). Likewise, Culbertson (1995) suggested that three principles stand out to help define and explain truly effective public relations around the world: two-way symmetrical practice, well-trained and educated practitioners, and the empowerment of public rela-tions in the dominant coalition.

The opposing view, however, considers symmet-rical communication and ethical communication as two different conceptual dimensions (Grunig, 2001). Different from his previous argument, Grunig (2001) maintained that, although a symmetrical model should be inherently ethical, other models could be ethical, too, depending on the rules used to ensure ethical practice. He thus separated ethical commu-nication and symmetrical commucommu-nication as two different dimensions. Grunig’s (2001) later argument is the basis for this paper’s first Research Hypothesis. Research Hypothesis 1. Ethical communication and symmetrical communication are fundamentally dis-tinguishable, but inter-correlated, factors represent-ing public relations practice.

Public relations effectiveness

The literature suggests that measuring public rela-tions performance is complex, due to its multidi-mensional nature (see Hon, 1997; Huang, 2002). In order to provide a comprehensively analytical

framework of public relations performance, this paper first consults Huang’s (2002) three direct-level measures of public relations effectiveness and then Heath’s (2001) two paradigms of public relations values representing organizational effectiveness.

Huang (2002) used the following three measures to represent direct-level public relations effective-ness: organizational reputation (Grunig, 1993; Kim, 2001), communication effects (Bissland, 1990; Lin-denmann, 1988, 1993, 1995), and organization– public relationships (Grunig and Huang, 2000; Huang, 2001b). Given the extensive and fruitful re-search that has already been conducted over the last two decades on the organization–public relationship, this paper will focus on exploring the other two performance measures of public relations effective-ness: organizational reputation and media exposure. Organizational reputation

To date, public relations effectiveness has been investigated from the perspective of reputation management. Some published works have revealed that the ultimate aim of public relations is to com-municate the reputation of the organization (e.g., Hon, 1997; Kim, 2001). Grunig (1993) considered reputation as representing the behavioral relation-ships of an organization with its publics. This paper adopts Grunig’s (1993) and Huang’s (2002) con-ceptualization and defines corporate reputation as the aggregate perception of an organization (Mar-ken, 1990), which leads to Research Hypothesis 2. Research Hypothesis 2. Symmetrical communication contributes to favorable organizational reputation. Media exposure

Researchers have long investigated the communi-cation effects of public relations with respect to (1) measures of communication output or media exposure, e.g., quantity of output, number of media contacts, and quality and quantity of media place-ments (see Bissland, 1990; Dozier and Ehling, 1992; Lindenmann, 1988; 1993; 1995), and (2) measures of communication effects, generally assumed to be awareness, interest, cognition, attitudes, or behavior (see Grunig, 1993; Hon, 1997). The basic assump-tion of examining the effect of public relaassump-tions from the perspective of communication effects is that communicated messages should cause changes in

knowledge, attitudes, and behavior among the tar-geted publics. In academia, measures of communi-cation effect are more commonly used, whereas in the field of practical public relations, the most fre-quently used evaluation measures are communica-tion outputs and media exposure (Bissland, 1990). In this study, the latter measure is investigated and this focus leads to Research Hypothesis 3.

Research Hypothesis 3. Symmetrical communica-tion contributes to positive media exposure.

Revenue-generation effects of public relations value Heath (2001) investigated the value of public relations from the perspective of organizational effectiveness, using two paradigms to define the value of public relations to organizations: revenue generation and cost reduction. He emphasized that public relations prac-titioners are interested in a revenue-generating para-digm, while scholars are interested in a cost-reducing paradigm so that the values that are often invisible would be accounted for. In this study, the measures of market input and overall organizational effectiveness are used to represent the revenue-generating paradigm, while conflict resolution and crisis management are adopted as measures for the cost-reducing paradigm. Market input

With respect to the revenue-generating paradigm, the area encompassing marketing effects has been especially emphasized. Kim (2001) made it evident that public relations exert influence on organizations by increasing financial performance and company revenue. Kim (1997) also provided empirical evi-dence of the positive relations between a company’s public relations and organizational returns across different industries and companies. Based upon the above discussion, Research Hypothesis 4 is posited. Research Hypothesis 4. Symmetrical communica-tion contributes to positive market performance. Overall organizational effectiveness

Several published works have demonstrated that public relations positively influence organizational effectiveness in various ways (Huang, 2001a, b; Kim, 2001). Huang (2002) concluded that the wide

variety of measures of overall organizational effec-tiveness can be divided into those pertaining to long-term performance and short-long-term performance. In this research, the measure of overall organizational effectiveness, regardless of any specific aspect, is investigated. The basic assumption is that, as long as goals of the organization are achieved, whether long-term or short-term goals, then the overall organizational effectiveness of the activity being measured is demonstrated. Since most organizations consider the bottom line as an indication of the attainment of their corporate goals, achieving overall organizational effectiveness is categorized as a vari-able in the assessment of the revenue-generation affects of public relations value. The above discus-sion leads to Research Hypothesis 5.

Research Hypothesis 5. Symmetrical communica-tion contributes to positive overall organizacommunica-tional effectiveness

Cost-reduction effects of public relations value Conflict resolution

Grunig et al. (1997) maintained that excellent public relations contribute to organizational effectiveness by managing conflict and by reducing the costs of conflict that result from regulation, pressure, and litigation. Moreover, the literature seems to suggest the need for two-way symmetrical communication between organizations and activists (Anderson, 1992; Grunig, 1992b; Huang, 1994, 1997, 2001a; Pavlik, 1989). For example, Huang (1997) demonstrated that symmetrical communication could lead to coopera-tion from the organizacoopera-tion’s constituency in a con-flict situation. Huang (2001a) further demonstrated that public relations could indeed reduce the conflicts between an organization and its stakeholders through favorable organization–public relationships that result from symmetrical communication. The above dis-cussion leads to Research Hypothesis 6.

Research Hypothesis 6. Symmetrical communica-tion contributes to conflict resolucommunica-tion.

Crisis management

Research has revealed that public relations contrib-ute to organizational effectiveness via crisis man-agement and crisis communications (Marra, 1998).

Appropriate response strategies help organizations pass through the challenges of media pressure and public criticism during crisis situations (Benoit and Brinson, 1999; Hearit, 1996). After the sudden death of Princess Diana, there was a popular perception that the British Royal Family did not fully share in the public’s evident grief. The enormous public relations problem which resulted provoked the Queen of England to give an unprecedented speech. Benoit and Brinson (1999) investigated this highly public illustration of royal public relations and found the Queen’s efforts to have been generally well conceived and effective in terms of crisis manage-ment. Therefore, Research Hypothesis 7 is posited. Research Hypothesis 7. Symmetrical communica-tion contributes to crisis management.

Method Samples

Three surveys were undertaken to test the seven re-search hypotheses. The surveys, conducted on three independent samples, were designed to cross-validate the research findings. Information was collected from working public relations practitioners and their constituencies, not from student samples. The three survey data sets include (1) 301 questionnaires an-swered by legislators and their assistants in the Second Plenary Session of the Third Legislative Yuan in Taiwan from April to June in 1997,1 (2) an island-wide survey of 1087 Taiwan residents on the issue of the construction of the fourth nuclear power plant, and (3) a survey of 326 public relations practitioners, from Taiwan’s Top 500 companies and from PR agencies, concerning public relations practice.

To enhance the generalizability of the research findings, the three studies cover a variety of issues reflecting public relations practice, i.e., an executive – legislative relationship important to government public relations, a nuclear issue important to a public utility company’s public relations practice, and gen-eric aspects of public relations – such as organizational reputation, media exposure, and market input – important for corporate public relations practice. It should be noted that the above-mentioned research design ensures that the perspectives of goal attainment

(Mark et al., 1997) and strategic constituencies (Grunig, 1992a; Stone and Cutcher-Gershenfeld, 2002) are both included in this paper. The first and second data sets, which will be discussed later, were conducted in order to represent the perspective of strategic constituency, while the third data set is re-lated to the organization’s goal attainment.

Study 1

Legislators and their assistants in the Second Plenary Session of the Third Legislative Yuan in 1997 in Taiwan were surveyed, from the perspective of stra-tegic constituency, in order to test the role of sym-metrical communication in executive-legislative relations. All 758 legislative members and their assistants were contacted, of whom 301 returned valid questionnaires. The survey yielded a 0.45 response rate for all respondents and a 0.54 rate for legislative assistants. Forty-nine percent of the respondents were male, 51% were female. The educational level ranged from some high school to a doctoral degree. Political parties were represented in this sample in close pro-portion to their representation in the Second Plenary Session of the Legislative Yuan.

Study 2

An island-wide telephone survey addressed the con-troversy over the planned construction of Tai-wan’s fourth nuclear power plant and the proposed Taiwan Power Company (TPC). A random sample of Taiwan residents, aged 20 and above, was selected from a computer-generated randomized list, using the method of stratification according to cities, townships, and villages. 1495 residents were contacted by telephone in June of 1999, using the computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) design. Four hundred and eight turned down the interview, yielding an effective sample of 1087 respondents. The response rate was 72.7%, with a sampling deviation of ±3.0% at a confidence level of 95%. Forty-eight percent were male, and the educational levels ranged from high school to a master’s degree. This sample appears to have been representative of the island’s population in terms of gender, age, and residential area, and to have captured the full range of TPC’s constituencies’ opinions, so as to represent the per-spective of strategic constituency. Therefore, an investigation into TPC’s activities in the area of public relations can provide valuable insight into the public relations effectiveness of symmetrical communication.

Study 3

In contrast to the previous two studies, Study 3 represents the organizational perspective. Three hundred and twenty six public relations practitio-ners, drawn from Taiwan’s Top 500 companies and from public relations agencies, were surveyed. Sixty-six percent held bachelor’s degrees and another 25% had achieved a graduate degree. The average age of the respondents was 36.61 years (SD¼ 10.28); 61% were female. Seventy percent served as in-house public relations representatives, while 30% were in public relations agencies. The average tenure of respondents in the Top 500 companies fell in the 0– 6 years range (68.8%) and in the 0–4 years range (73.2%) for those in PR agencies.

Survey instrumentation

In Study 1, legislative members and their assis-tants were instructed to think about public rela-tions activities conducted by the public relarela-tions practitioners in the governmental department which they contact most frequently. The respondents were then asked to indicate the statement that best de-scribed their perception of the public relations practice of that department. Similarly, the respon-dents in Study 2 were asked to assess the public relations practices employed by the TPC, particu-larly those connected with the nuclear issue. Thus, for the first and second studies, the survey instru-ments primarily evaluate an organization’s perspec-tive of public relations practice. In Study 3, public relations practitioners from agencies and Top 500 companies were asked to assess their own public relations practice and their contribution to the organization.

The judgmental measure – asking informants for their assessments of public relations practice – was used. It is worth noting that judgmental mea-sures have been widely viewed as valid in many fields (Deshpande et al., 1993; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993) because significant evidence exists to indicate a close association between objective and perceptual measures of business performance (e.g., Dess and Robinson, 1984; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Pearce et al., 1987; Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1987).

Symmetrical communication and ethical communication A Likert-type scale – (1) never, (2) seldom, (3) some-times, and (4) often – is used in the symmetrical and ethical communication measures. Measurement items are adopted from previously published, estab-lished scales (Dozier et al., 1995; Grunig, 1984; Huang, 1999). In Study 1, the items related to symmetrical communication are: (1) They not only tried to change our attitude and behavior, but also tried to change the attitude and behavior of the management at said department; (2) They tried to change their department’s behaviors and policies after considering our opinions; (3) They consulted those influenced by their policies during decision making; and (4) Their main goal was to get us to do what they want. The questions related to ethical communication are: (1) They considered how their public relations influenced us; (2) They provided us with accurate information; (3) They considered the public interest more than their own individual interests; (4) They considered the public’s interests more than their own department’s interests; (5) They engaged in open lobbying; (6) They engaged in private lobbying; and (7) They told us their motives and reasons for their actions.2

Performance variables

As previously mentioned, this paper tries to provide a comprehensive picture, reflecting as many aspects of public relations performance as possible. Six performance variables are investigated. Due to time and space limits on the three surveys, one item in-stead of a multi-item scale is used for measuring each outcome construct. Given that deficiency, the sim-ilar format of question wording for all performance measures is adopted so that a comparison across measures can be made.

The question for measuring organizational reputa-tion in Study 2 is ‘‘Please rate the overall corporate image of the TPC on a 0–100 scale.’’ In Study 3, the question is ‘‘Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the reputation of your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale?’’3

The questions for measuring media exposure are ‘‘Please rate the TPC’s overall communication

per-formance involving the nuclear issue in the mass media on a 0–100 scale’’ in Study 2, and ‘‘Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to media coverage and exposure for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale?’’ in Study 3.

To measure market input, the question asked in Study 2 is ‘‘Given a chance, would you change to a different utility company?’’ It should be noted that, since the item is negatively worded, the corre-sponding responses are reversed for statistical calcu-lation. The discussion of results later in this paper will be based on reversed scores. The question posed in Study 3 to the public relations practitioners is ‘‘Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the market sales for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.’’

With the regard to overall organizational effectiveness, respondents in Study 2 were asked, ‘‘How accept-able do you find the continued construction of Taiwan’s fourth nuclear power plant?’’ The major reason for asking this question is that the controversy over the proposed fourth nuclear power plant has gone on for over 30 years, and continuing with the construction of that plant is TPC’s organizational mission. In Study 3, the question for measuring overall organizational effectiveness is ‘‘Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the achievement of goals for your organization (or cli-ents) on a 0–100 scale.’’

Conflict resolution and crisis management are difficult to measure from the constituencies’ perspective as designed in Study 2. Thus, questions are posed specifically involving the nuclear issue. The item for measuring conflict resolution is ‘‘Generally speaking, I am satisfied with TPC’s problem definition and decision making on the nuclear issue,’’ based upon the assumption that, given such a satisfaction, the possibility of protest would be reduced. On the grounds that trust is the essential component in crisis communication involving a nuclear issue (Fitchen, et al., 1987; Krimsky and Plough, 1988; National Research Council, 1989), the question posed is ‘‘Generally, how much do you trust TPC’s ability to operate a nuclear power plant’’? In Study 3, the questions posed for the measure of conflict resolu-tion and crisis management are ‘‘Please rate the ex-tent to which public relations contribute to conflict resolution for your organization (or clients) on a 0– 100 scale’’ and ‘‘Please rate the extent to which

public relations contribute to crisis management for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.’’

In order to enhance face validity, a group of expert judges, including nine TPC public relations practi-tioners and 22 corporate public relations practitio-ners, were interviewed, before the three formal surveys were conducted, to explore the pertinence and accuracy of the initial pool of items intended to measure ethical communication and symmetrical communication.

Results and discussion

The first research hypothesis posits that ethical communication and symmetrical communication are fundamentally distinguishable, but inter-corre-lated, factors representing public relations practice.

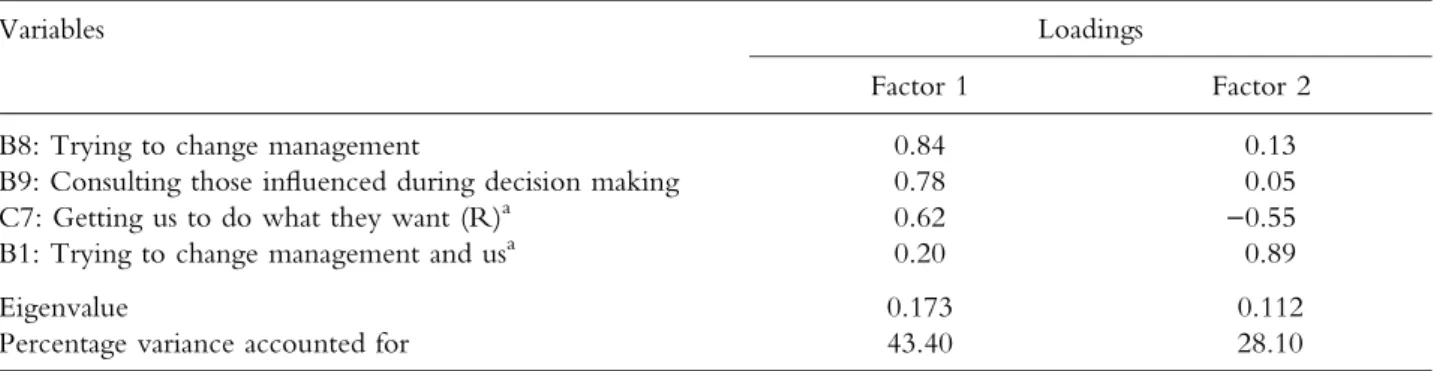

Appendix 1 contains all measure scales testing per-formance measures in the studies 2 and 3. Table I provides an overview of construct means, standard deviations, and correlations. The items concerning symmetrical communication and ethical communi-cation used for testing hypothesis 1 are first tested in Study 1 and then cross-validated in Studies 2 and 3. Factor analyses are adopted for testing this hypoth-esis, revealing that the four items measuring sym-metrical communication are separated into two groups with B8, B9, and C7 grouped together, while Bl has singled itself out. Item C7 is then re-moved from the factor due to its low factor loading (Table II). Moreover, item B1 is also discarded, because it seems to belong to a different factor from the other items.

With regard to ethical communication, statistical results also reveal that two factors are extracted from TABLE I

Mean and standard deviations of the items of symmetrical/ethical communication in the three data sets

Data set Items Mean Standard deviation

Data set 1 B7: Considering the impact on us 2.75 0.81

B8: Trying to change management 2.34 0.80

B9: Consulting those influenced during decision making

2.38 0.86

B10: Considering public interest 2.62 0.90

Data set 2 T9: For decisions about the interests of the

public, TPC and the public have equal influence during communications.

2.72 0.91

T21: When communicating about nuclear power, TPC took into account the public’s opinions.

2.42 0.91

T22: During the decision-making process, TPC consulted the public’s opinions.

1.95 0.86

T23: The public has enough channels to express opinions about the impact of nuclear power on them.

1.94 0.96

Data set 3 A13: We consulted those influenced by

our policies and opinions during decision making.

3.36 0.77

A14: During communication, we took into account the possible negative impact on the public.

3.69 0.57

A15: We considered both their and our opinions and positions during communication.

3.81 0.44

A16: We considered how our public relations influenced them.

the seven items. Items A14 and A15 are fused to-gether as one factor, and the other five are grouped as another. Items A14 and A15, which address lob-bying, are removed first, inasmuch as they might be considered by the respondents to reflect the beha-viors of lobbying itself, rather than the moral aspect of public relations that I am interested in investi-gating. Items Cl and C8 are also discarded, because of their low factor loadings, which leaves items B6, B7, and BIO in the factor (Table III).

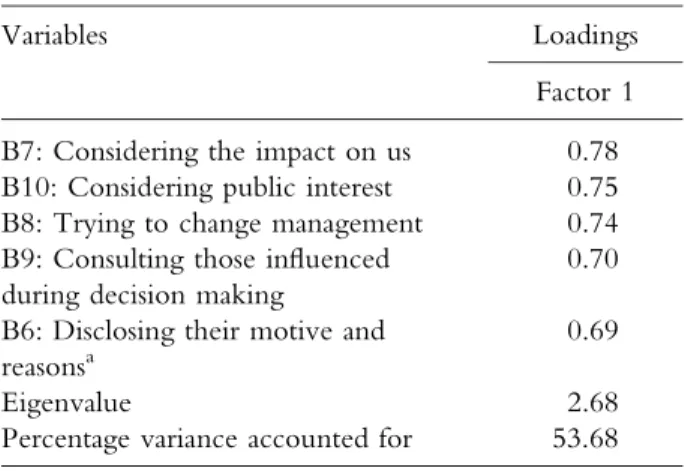

As suggested in the Conceptualization section above, ethical communication and symmetrical communication often coexist. Therefore, in order to test the relationship between these two dimensions, a factor analysis is conducted to combine the remaining two items on symmetrical communication (B8 and

B9) and the three items on ethical communication (B6, B7, B10) (see Table IV). The results show that, indeed, only one factor is extracted. After taking the theoretical propositions into account, these stated items are included in one factor and renamed as ‘‘symmetrical/ethical communication.’’ This new factor is further tested for its reliability and validity across Study 2 and Study 3. The following criteria are tested: uni-dimensionality, internal consistency of items, and construct reliability.

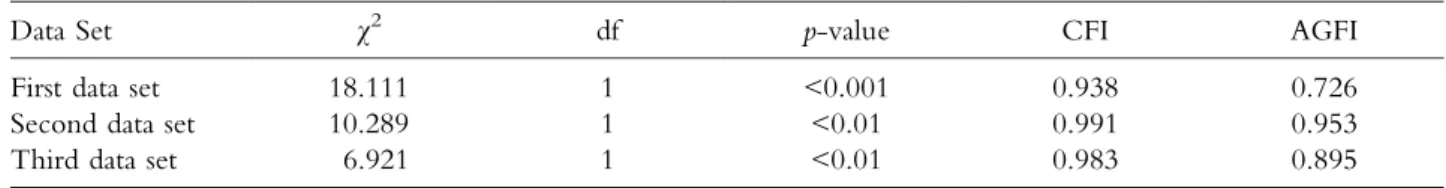

Uni-dimensionality

For the purpose of testing the uni-dimensionality of symmetrical/ethical communication, further factor TABLE II

Factor loadings for symmetrical communication from data set 1

Variables Loadings

Factor 1 Factor 2

B8: Trying to change management 0.84 0.13

B9: Consulting those influenced during decision making 0.78 0.05

C7: Getting us to do what they want (R)a 0.62 )0.55

B1: Trying to change management and usa 0.20 0.89

Eigenvalue 0.173 0.112

Percentage variance accounted for 43.40 28.10

R – indicates the item was reverse-scored.

a

The item eventually was removed from the factor.

TABLE III

Factor loadings for ethical communication from data set 1

Variables Loadings

Factor 1 Factor 2

B7: Considering the impact on us 0.78 0.04

B10: Considering public interest more than individual interest 0.76 )0.11

B6: Disclosing their motives and reasons 0.75 )0.02

Cl: Providing accurate informationa 0.60 )0.38

C8: Considering public interest more than department interesta 0.55 )0.18

A15: Private lobbyinga 0.23 0.86

A14: Open lobbyinga 0.24 0.84

Eigenvalue 2.53 1.63

Percentage variance accounted for 36.20 23.30

a

analyses are conducted in Studies 2 and 3. These analyses indicate that this new dimension remains as one factor (Table V) across two independent samples. Moreover, the exploratory factor analyses demon-strate that the overall goodness of fit (Table VI) sup-ports uni-dimensionality (Steenkamp and van Trijp, 1991). The CFIs of this factor across the three con-secutive studies are 0.87, 0.99, and 0.98, respectively. Internal scale consistency and construct reliability

The internal consistency of the items in the factor is measured by Cronbach’s alpha and construct reli-ability. The Cronbach’s alpha values in the first, second, and third studies are 0.75, 0.72, and 0.71. The construct reliabilities that result from dividing the amount of total standardized variance/covari-ances explained by a factor by the total amount of standardized variance/covariances, are 0.75, 0.74, and 0.76, respectively. A generally accepted bench-mark for adequate internal consistency reliability is 0.80 (Nunally, 1978). On the other hand, having a construct reliability over 0.70 is generally considered to indicate ‘‘good’’ reliability (Miller, 1995). Of these two reliability tests, construct validity was relied upon more, because the statistical assumption underlining Cronbach’s alpha is less applicable in this study. In summary, except for a comparatively low Cronbach’s alpha in the second sample, which is of a nationwide, cross-sectional nature, the scale measure of symmet-rical/ethical communication has acceptable and

sat-isfactory uni-dimensionality, internal consistency of items, and construct reliability across three studies. Validity

As previously stated, a group of expert judges, including nine TPC public relations practitioners and 22 corporate public relations practitioners, were interviewed to test the pool of items used to assure face validity. These interviews ensure that the measurement is comprehensible and each question can elicit a valid response. Moreover, convergent validity is supported by the fact that all factor load-ings are significant (p < 0.01) and nearly all R2 ex-ceed 0.50 (Hildebrandt, 1987) (Table V).

Discussion

The empirical data across three studies suggest that two concepts, teleology and symmetrical worldview, play essential roles in the factor of symmetrical/ethical communication. In Study 1, the notion of an organization’s willingness to make changes (sym-metrical worldview) underlies items B8 and B9. Items B7 and B10 reflect the Ideological (or con-sequentialist) theory that suggests an organization should consider the impact of communication behavior on its constituencies and on the larger society (Grunig and Grunig, 1996). The notion of symmetrical/ethical communication is replicated in Studies 2 and 3. In summary, the attempt to differ-entiate symmetrical communication from ethical communication has been proven to be in vain. The empirical data show that the two factors, although hypothesized to be separate, end up grouped as one. The fusion of these two factors supports Grunig and Grunig’s (1996) argument that ‘‘public relations will be inherently ethical if it follows the principles of the two-way symmetrical model’’ (p. 40). It is worth noting that the notion of disclosure (Bok, 1989), which is measured by the item ‘‘We explained our motives and reasons for our actions to them,’’ is fi-nally excluded in the measurement, due to its instability, demonstrated by the fact that its factor loading is borderline in Study 1, and by the fact that it is grouped in a different factor with the others items in Study 3.

TABLE IV

Factor loadings for symmetric/ethical communication from data set 1

Variables Loadings

Factor 1

B7: Considering the impact on us 0.78

B10: Considering public interest 0.75

B8: Trying to change management 0.74

B9: Consulting those influenced during decision making

0.70 B6: Disclosing their motive and

reasonsa

0.69

Eigenvalue 2.68

Percentage variance accounted for 53.68

a

TABLE V Factor loadings and reliability test in the first, second and third data sets Dimension Items Factor loadings First data set Second data set Third data set First data set Second data set Third data set Symmetrical /ethical communicatio n B9: Consulting those influenced during decision making T22: During the decision-makin g process, TPC consulted the public’s opinions. A13: We consulted those influenced by our policies and opinions during decision making. 0.75 0.83 0.55 B10: Considering public interest T9: For the decisions about the interests of the public, TPC and the public have equal influence during communicatio ns. A14: During communicatio n, we took into account the possible negative impact on the public. 0.77 0.53 0.76 B8: Trying to change management T21: When communicating about nuclear power, TPC took into account the public’s opinions. A15: We considered both their and our opinions and positions during communication. 0.79 0.82 0.84 B7: Considering the impact on us T23: The public has enough channels to express opinions about the impact of nuclear power on them. A16: We considered how our public relations influenced 0.71 0.77 0.88 Construct reliability 0.75 0.74 0.76 Alpha 0.75 0.72 0.71 Eigenvalue 2.30 2.23 2.36 Percentage variance accounted for 57.50 55.81 58.90

Having taken into account the appropriate properties of reliability and validity of symmetrical/ ethical communication, the new dimension is used for hypothesis tests. Research Hypotheses 2 and 3 measure the public relations effectiveness of sym-metrical communication involving favorable orga-nizational reputation (H2) and positive media exposure (H3). These two hypotheses are partially supported. As shown in Table VII, the data indicate divergent results across two studies. In Study 3, symmetrical/ethical communication is an influential predictor of favorable organizational reputation and positive media exposure (b¼ 0.181, p ¼ 0.002, and b¼ 0.201, p ¼ 0.001, respectively). However, such significant relationships do not appear in Study 2.

Research Hypotheses 4 and 5 measure the reve-nue-generating effects of public relations value; that is, whether symmetrical communication contributes to market input (H4) and overall organizational effectiveness (H5). These two hypotheses are fully supported. The results indicate that symmetrical/ ethical communication effectively predicts market input and overall organizational effectiveness across two independent samples. In Study 2, the results

reveal that symmetrical/ethical communication is a predictor of market input (b¼ 0.363, p < 0.001) and favorable agreement on the construction of the fourth nuclear power plant (b¼ 0.365, p < 0.001). The results of Study 3 are used to cross-validate the findings from Study 2. The results demonstrate that the respondents’ self-assessed symmetrical/ethical communication have substantial power in predicting market sales (b¼ 0.120, p ¼ 0.042) and overall organizational effectiveness (b¼ 0.120, p ¼ 0.040). Research Hypotheses 6 and 7 explore the cost-reducing effects of public relations value; that is, whether symmetrical communication contributes to conflict resolution (H6) and crisis management (H7). These two hypotheses are also fully supported across two samples. In Study 2, symmetrical/ethical com-munication effectively predicts the capacity for conflict resolution, which is demonstrated by the fact that the public is satisfied with TPC’s problem definition and decision making on the nuclear issue (b¼ 0.479, p < 0.001). Symmetrical/ethical com-munication also has predictive power for crisis management, because the public trusts TPC’s ability to operate a nuclear power plant (b¼ 0.481, TABLE VI

Summary of model-fit statistics for symmetrical/ethical communication

Data Set v2 df p-value CFI AGFI

First data set 18.111 1 <0.001 0.938 0.726

Second data set 10.289 1 <0.01 0.991 0.953

Third data set 6.921 1 <0.01 0.983 0.895

CFI = comparative fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness-of-fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

TABLE VII

Regression analyses of symmetrical/ethical communication on performance measures in data sets 2 and 3

Performance measures Second data set Third data set

R R2 b t sig R R2 b t sig Organization reputation 0.068 0.005 0.068 1.302 0.194 0.181 0.033 0.181 3.133 0.002 Media exposure 0.066 0.004 0.066 1.276 0.203 0.201 0.040 0.201 3.488 0.001 Market performance 0.363a 0.132 0.363a 7.090 0.000 0.120 0.015 0.120 2.041 0.042 Overall effectiveness 0.365 0.134 0.365 7.392 0.000 0.120 0.014 0.120 2.059 0.040 Conflict resolution 0.479 0.229 0.479 9.299 0.000 0.131 0.017 0.131 2.023 0.044 Crisis communication 0.481 0.231 0.481 10.218 0.000 0.136 0.018 0.136 2.097 0.037 a

p < 0.001). In Study 3, symmetrical/ethical com-munication can effectively predict the respondents’ self-assessment that the conflicts between organiza-tions and their stakeholders can be resolved (b¼ 0.131, p < 0.05) and that crises can be man-aged (b¼ 0.136, p < 0.05). The causal paths from symmetrical/ethical communication to conflict res-olution and crisis management are both statistically significant at the 0.05 level. In summary, the results indicate that symmetrical/ethical communication has a mild to moderate influence, across two studies, on these two cost-reduction measures which are theoretically important for the effectiveness of public relations (Heath, 2000).

Discussion for Research Hypotheses 2–7

The effects of symmetrical/ethical communication on performance measures can be discussed from two standpoints. First, there are convergent and diver-gent findings in the two studies. The converdiver-gent results are that the respondents perceive an organi-zation’s use of symmetrical communication as inherently ethical, and that it positively affects their assessment of market intentions or market sales, the overall organizational performance, and the organi-zation’s capacity for conflict resolution and crisis management. On the other hand, the divergent re-sults reveal that symmetrical/ethical communication was a predictor of positive organizational reputation and media coverage in Study 3, but not in Study 2, which suggests that such hypothesized relationships should be considered suggestive rather than con-clusive. The factor contributing to the insignificant associations in Study 2 may be due to the specific context. The construction plan for the fourth nu-clear power plant has been postponed for more than 30 years; so many years of heated controversy and public antagonism may have resulted in the public’s negative stereotype and the media’s negatively in-clined coverage of the proposed entity, the TPC.

Second, comparing the path strengths in two studies, most of the paths in Study 2 are of moderate size, while those in Study 3 are mild. Specifically, in Study 2, the paths ranged between 0.3 and 0.4, i.e., conflict resolution (b¼ 0.479, p < 0.001) and crisis management (b¼ 0.481, p < 0.001), followed by two revenue-generating measures, i.e., overall

organizational effectiveness (b¼ 0.365, p < 0.000) and market input (b¼ 0.363, p < 0.000). In Study 3, however, except for media exposure, for which the path is over 0.2, and organizational reputation, for which the path reaches 0.2, all the other paths remain under 0.15. The divergent results of path strengths between the studies might result from two factors. The first factor is the nature of the questions posed. The questions in Study 2 are directed to a specific issue, the nuclear power issue, while those in Study 3 are general and non-focused. Public rela-tions practices exert more evident effects on specific, focused issues than on general ones. The second factor also is concerned with the nature of mea-surement. Study 2 is investigated from the perspec-tive of constituencies while Study 3 is investigated from the perspective of organizations. The differ-ence between these two approaches deserves more future research.

Conclusion

Summary of the findings

The relationship between symmetrical communication and ethical communication

In this study, factor analyses are conducted in re-sponse to the question: Is symmetrical communica-tion inherently ethical? Symmetrical communicacommunica-tion is conceptualized by focusing on the organiza-tion’s intent to initiate changes, in contrast to merely trying to change the cognitions, attitudes, or behaviors of the publics. The conceptualization of ethical communication includes three focal con-cepts: teleology, disclosure, and social responsibility. The attempt to differentiate symmetrical commu-nication from ethical commucommu-nication, however, proves to be in vain. Although hypothesized to be separate, the empirical data show that the two fac-tors eventually are grouped as one. The fusion of these two factors supports Grunig and Gru-nig’s (1996) argument that ‘‘public relations will be inherently ethical if it follows the principles of the two-way symmetrical model’’ (p. 40). The focal notions underlying the items in the resul-tant factor ‘‘symmetrical/ethical communica-tion’’ include symmetrical worldview and teleology.

The effects of symmetrical/ethical communication on performance measures

The second purpose of this paper is to explore the effects of symmetrical communication, which are tested in Study 2 and Study 3. Table VII indicates that across two independent samples, the significant relationships between symmetrical/ethical commu-nication and all performance variables are in the hypothesized, positive direction, except media exposure (H2) and organizational reputation (H3), which are only partially supported. These results provide strong empirical evidence for the cross-validation of the hypotheses posited in the Conceptualization section, which is especially noteworthy given that the samples examined differ considerably in their demographic, economic, and issue dimensions, and in their goal-attainment and strategic-constituency perspectives. After examining H4 to H7, which explicate the associations between symmetrical communication and two revenue-gen-eration-related variables as well as two cost-reducing measures, consistent patterns of effects exist across two independent samples, i.e., symmetrical com-munication has more predictive power with respect to conflict resolution and crisis management, i.e., two cost reducing measures than market input and overall organizational effectiveness, i.e., two reven-ue-generation-related variables.

Implications for theory

Five theoretical implications of these results stand out.

First, the results replicate the findings of Grunig and White (1992) and Grunig et al. (1997) in that symmetrical/ethical communication, a critical component of excellent public relations, indeed contributes to several performance measures. Spe-cifically, from the perspectives of both organizations and their constituencies, an organization’s use of symmetrical/ethical communication can predict most of the positive performance outcomes pro-posed in this study.

Second, the empirical evidence of this study challenges the criticism that the symmetrical worldview is unrealistic (Van der Meiden, 1993), by revealing that symmetrical communication actually serves organizations’ interests.

Third, this study also shows that the relationship between the generic principle of public relations, i.e., symmetrical communication, and its effect is indeed universal and generic to different cultures, replicat-ing the findreplicat-ings of the Excellence Study (Grunig et al., 1997). In Taiwan, as in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, symmetrical communication appears to contribute to various as-pects of public relations effectiveness and organiza-tional effectiveness. These findings support Culbertson’s (1995) assertion that a symmetrical practice helps define and explain truly effective public relations.

Fourth, following the suggestion of Grunig and Grunig (1996), this study moves beyond the four static public relations models and uses a continuous dimension – symmetrical communication – to represent public relations strategies. A series of factor analyses and reliability tests further demon-strate the viability of using symmetrical communi-cation to describe an organization’s public relations practice.

Fifth, the empirical result involving H6 helps to demonstrate the relationship between symmetrical communication and conflict resolution, contradicting previous work (Grunig, 1992b; Huang, 1994, 2001a) by demonstrating that symmetrical/ethical commu-nication can directly lead to conflict resolution.

Implications for future studies

This study has sought a systematic understanding through the inclusion of several performance mea-sures and has tested their relationships with sym-metrical/ethical communication. This attempt is guided by a theoretical framework and compre-hensive conceptualization, and has been tested on three independent samples. I believe it can serve as an adequate starting point for further research to investigate the variables involved and the relation-ships considered. The following future research directions are suggested.

First, the critical next step should be qualitative research to explore in-depth contextual information as the basis for further data interpretation (Marshall and Rossman, 1995; McCracken, 1988). As sug-gested in Sypher (1990), qualitative research can ‘‘bring to life the nuances of work life and talk’’

(pp. 3–4). The findings should generate insight by exploring questions drawn from this study: What is the role of cultural factors on symmetrical commu-nication and ethical commucommu-nication? Does they play any role in the fusion of these two factors?

Second, replication procedures are critical in or-der to further cross-validate the results obtained in this study. Concepts and relationships could be tes-ted on different samples and cultures.

Third, the findings concerning the effects of symmetrical/ethical communication on media cov-erage and organizational reputation should be viewed as being suggestive rather than conclusive, because only one study confirms the hypothesized relation-ships. A replication of other studies could help to ensure the generalizability of the findings.

Fourth, as stated before, the concept of disclosure is not included in the measure, because of its unstable factor properties. Future research could explicate this notion conceptually and operationally. Moreover, the cultural implications of the notion of disclosure are also worth additional exploration, because of the discrepancy between the Oriental and Western views of the fundamental purpose and nature of communication. Chinese communication style tends to be high-context, in contrast to the Western low-context style (Gao and Ting-Toomey, 1998; Gudykunst et al., 1996). On the other hand, Scollon and Scollon (1994) suggest that, in Western cultures, the purpose of communication is infor-mation exchange. By contrast, people in Asian

cul-tures communicate for the purpose of relationship building and maintenance; they emphasize rela-tionships over communication. It is therefore logical to question whether cultural difference is the factor that results in the exclusion of disclosure from symmetrical/ethical communication in this paper. The role of culture on the relationship between disclosure and symmetrical/ethical communication is worth further exploration.

Lastly, it is worth noting that comparisons among the path strengths of regression tests reveal, surpris-ingly, that the effect sizes from constituencies’ per-spective (Study 2) are higher than those from organizations’ perspective (Study 3). Does this mean that symmetrical/ethical communication is more valued by the constituencies than by the organiza-tions themselves? Or is symmetrical/ethical com-munication undervalued from a goal-attainment perspective? Such questions may also deserve special attention in future research.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was developed with grants from the Ministry of Education, Republic of China [89-H-FA01-2-4-2(91-2-5)] and the National Science Council [NSC89-TPC-7-004-003]. The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable input from two anonymous reviewers and Professors James Grunig and Larissa Grunig.

Appendix 1

Items testing performance measures in Study 2 and Study 3 Study 2

Organizational reputation

Please rate the overall corporate image of TPC on a 0–100 scale. Media exposure

Please rate TPC’s overall communication performance involving the nuclear issue in the mass media on a 0–100 scale.

Market inputa

Given a chance, would you change to a different utility company? Overall organizational effectiveness

How acceptable do you find the continued construction of Taiwan’s fourth nuclear power plant? Conflict resolution

Notes

1

The data was collected for and reported in Huang’s (1997) unpublished dissertation. Partial statistical results of the PRSA scale, such as reliability efficiencies and the model CFI were presented at the 1998 AEJMC confer-ence (Huang, 1998).

2

The respondents in the pre-tests maintained that the concept of moral responsibility was ambiguous. Thus, I use ‘‘engaging in public lobbying’’ and ‘‘engaging in private lobbying’’ to clarify the concept. Likewise, pre-test respondents indicated that they did not understand the notion of social responsibility. After having it tested in three pre-tests, I eliminated the item involving social responsibility and instead use two items involving public interest to measure this similar notion.

3

The questions addressing the clients are specifically directed to those respondents working in public relations agencies.

References

Amba-Rao, S. C.: 1993, ‘Multinational Corporate Social Responsibility, Ethics, Interactions and Third World

Governments: An Agenda for the 1990s’, Journal of Business Ethics 12, 553–572.

Anderson, D. S.: 1992, ‘Identifying and Responding to Activist Publics: A Case Study’, Journal of Public Relations Research 4, 151–165.

Benoit, W. L. and S. L. Brinson: 1999, ‘Queen Eliza-beth’s Image Repair Discourse: Insensitive Royal or Compassionate Queen?’, Public Relations Review 25(2), 29–41.

Bissland, J. H.: 1990, ‘Accountability Gap: Evaluation Practices Show Improvement’, Public Relations Review 10, 3–12.

Bivins, T. H.: 1987, ‘Applying Ethical Theory to Public

Relations’, Journal of Business Ethics 6, 195–

200.

Bok, S.: 1989, Secrets on the Ethics of Concealment and Revelation (Vintage Books, New York).

Carrol, A. B.: 1991, ‘The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders’, Business Horizons 34, 39–48.

Culbertson, H.: 1995, ‘Introduction’, in H. Culbertson and N. Chen (eds.), International Public Relations: A Comparative Analysis (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ), pp. 1–16.

Appendix 1. (Continued) Crisis management

Generally, how much do you trust TPC’s ability to operate a nuclear power plant? Study 3

Organizational reputation

Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the reputation of your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

Media exposure

Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the media coverage and exposure for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

Market input

Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the market sales for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

Overall organizational effectiveness

Please rate the extent to which public relations contributes to the achievement of goals for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

Conflict resolution

Please rate the extent to which public relations contribute to conflict resolution for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

Crisis management

Please rate the extent to which public relations contribute to crisis management for your organization (or clients) on a 0–100 scale.

a Since the item is negatively worded, the corresponding responses are reversed for statistical

Deshpande, R., J. U. Farley and F. E. Webster Jr.: 1993, ‘Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness’, Journal of Marketing 57(1), 23–27. Dess, G. G. and R. B. Robinson: 1984, ‘Measuring

Organizational Performance in the Absence of Objective Measures: The Case of the Privately Held Firm and Conglomerate Business Unit’, Strategic Management Journal 5, 265–273.

Donaldson, T.: 1989, The Ethics of International Business (Oxford University Press, New York).

Dozier, D. M. and W. P. Ehling: 1992, ‘Evaluation of Public Relations Programs: What the Literature Tells Us About Their Effects’, in J. E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communications Management (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 159–185.

Dozier, D. M., L. A. Grunig and J. E. Grunig: 1995, Manager’s Guide to Excellence in Public Relations and

Communication Management (Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Hillsdale, NJ).

Fitchen, J. M., J. S. Hearth and J. Ressenden-Raden: 1987, ‘Risk Perception in Community Context: A Case Study’, in B. B. Johnson and V. T. Covello (eds.), The Social and Cultural Construction of Risk: Essays on Risk Selection and Perception (D. Reidel Association, Dordrecht, Holland), pp. 31–50. Gao, G. and S. Ting-Toomey: 1998, Communicating

Effectively with the Chinese (Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA). Grcic, J.: 1989, Moral Choices: Ethical Theories and Problems

(West Publishing, St. Paul, MN).

Grunig, J. E.: 1984, ‘Organizations, Environments, and Models of Public Relations’, Public Relations Research & Education 1, 6–29.

Grunig, J. E.: 1989, ‘A Situational Theory of

Environmental Issues, Publics, and Activists’, in L. A. Grunig (ed.), Environmental Activism Revisited: The Changing Nature of Communication Through Organiza-tional Public Relations, Special Interest Groups and the Mass Media (The North American Association for Environmental Education, Troy, OH), pp. 50–82. Grunig, J. E. (ed.): 1992a, ‘Communication, Public

Relations, and Effective Organizations: An Overview of the Book’, In Excellence in Public Relations and

Communication Management (Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 1–30.

Grunig, L. A.: 1992b, ‘Toward the Philosophy of Public Relations’, in E. L. Toth and R. L. Heath (eds.), Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 65–91.

Grunig, J. E.: 1993, ‘Image and Substance: From Sym-bolic to Behavioral Relationships’, Public Relations Review 19(2), 121–139.

Grunig, J. E.: 2001, ‘Two-way Symmetrical Public Relations: Past, Present, and Future’, in R. L. Heath (ed.), Handbook of Public Relations (Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA), pp. 11–30.

Grunig, J. E. and L. A. Grunig: 1992, ‘Models of Public Relations and Communicatio’, in J. E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Man-agement (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 285–325.

Grunig, J. E. and L. A. Grunig: 1996, ‘Implications of Symmetry for a Theory of Ethics and Social Responsibility in Public Relations’, in Public Rela-tions Interest Group (International Communication Association, Chicago, IL).

Grunig, J. E. and Y. H. Huang: 2000, ‘From Orga-nizational Effectiveness to Relationship Indicators: Antecedents of Relationships, Public Relations

Strategies, and Relationship Outcomes’, in J.

Ledingham and S. D. Bruning (eds.), Public Rela-tions as RelaRela-tionship Management: A Relational Ap-proach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ), pp. 23–53.

Grunig, J. E. and T. Hunt: 1984, Managing Public Relations (Holt, Rinehart, Winston, New York).

Grunig, J. E. and J. White: 1992, ‘The Effect of Worldviews on Public Relations Theory and Prac-tice’, in J. E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 31–64.

Grunig, L. A., J. E. Grunig and W. P. Ehling: 1992, ‘What is an Effective Organization?’, in J. E. Grunig (ed.) Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management: Contributions to Effective Organizations (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 65–89.

Grunig, J. E., L. A. Grunig, K. Sriramesh, Y. H. Huang and A. Lyra: 1995, ‘Models of Public Relations in an International Setting’, Journal of Public Relations Re-search 7(3), 163–187.

Grunig, L. A., J. E. Grunig and D. Vercic: 1997, ‘Are the IABC’s Excellence Principles Generic? Comparing Slovenia and the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada’, Journal of Communication Management 2, 335–356.

Gudykunst, W. B., Y. Matsumoto, S. Ting-Toomey, T.,

Nishida, K. S. Kim and S. Heyman: 1996, ‘The

Influence of Cultural Individualism–Collectivism, Self Construals, and Individual Values on Commu-nication Styles Across Cultures’, Human Communica-tion Research 22, 510–543.

Hearit, K. M.: 1996, ‘The Use of Counter-Attack in Apologetic Public Relations Crises: The Case of

General Motors vs. Dateline NEC’, Public Relations Review 22(3), 233–248.

Heath, R. L.: 1992a, ‘The Wrangle in the Marketplace: A Rhetorical Perspective of Public Relations’, in E. L. Toth and R. L. Heath (eds.), Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 17–36.

Heath, R. L.: 1992b, ‘Critical Perspectives on Public Relations’, in E. L. Toth and R. L. Heath (eds.), Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ), pp. 37–64.

Heath, R. L.: 2000, ‘A Rhetorical Perspective on the Values of Public Relations: Crossroads and Pathways Toward Concurrence’, Journal of Public Relations Re-search 12(1), 49–68.

Heath, R. L. (ed.): 2001, ‘Shifting Foundations: Public Relations as Relationship Building’, in Handbook of Public Relations (Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA), pp. 1– 10.

Hildebrandt, L.: 1987, ‘Consumer Retail Satisfaction in Rural Areas: A Reanalysis of Survey Data’, Journal of Economic Psychology 8, 19–42.

Hon, L. C.: 1997, ‘What Have You Done for Me Lately? Exploring Effectiveness in Public Relations’, Journal of Public Relations Research 9(1), 1–30.

Huang, Y. H.: 1994, Ke chi feng hsien yu huan pao kang cheng: Tai-wan min chung feng hsien jen chih ke an yen chiu [Technological Risk and Environmental Activism: Case Studies of Public Risk Perception in Taiwan] (Wunan, Taipei) (in Chinese).

Huang, Y. H.: 1997, ‘Public Relations, Organization– Public Relationships, and Conflict Management’, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, (University of Maryland, College Park, MD).

Huang, Y. H.: 1998, ‘Public Relations Strategies and

Organization–Public Relationships’, in

Associa-tion for EducaAssocia-tion in Journalism and Mass Com-munication, Baltimore, MD, USA, August 5–8, 1998.

Huang, Y. H.: 1999, ‘The Effects of Public Rela-tions Strategies on Conflict Management’, in 49th Annual Conference of the International Communi-cation Association, San Francisco, CA, May 27–31, 1999.

Huang, Y. H.: 2001a, ‘Values of Public Relations: Effects on Organization–Public Relationships Mediating Conflict Resolution’, Journal of Public Relations Re-search 13(4), 265–301.

Huang, Y. H.: 2001b, ‘OPRA: A Cross-Cultural, Mul-tiple-Item Scale for Measuring Organization–Public Relationships’, Journal of Public Relations Research 13(1), 61–91.

Huang, Y. H.: 2002, ‘The Impact of Public Relations Effectiveness on Organizational Effectiveness: A Case Study in Taiwan’, in Chinese Communication Division, the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. Baltimore, Miami Beach, FL, August 7–10.

Jaksa, A. A. and M. S. Pritchard: 1994, Communication Ethics: Methods of Analysis (Wadsworth, Belmont, CA).

Jaworski, B. J. and A. K. Kohli: 1993, ‘Market Orienta-tion: Antecedents and Consequences’, Journal of Marketing 57(3), 53–70.

Karlberg, M.: 1996, ‘Remembering the Public in Public Relations Research: From Theoretical to Opera-tional Symmetry’, Journal of Public Relations Research 8(4), 263–278.

Kim, Y.: 2001, ‘Measuring the Economic Value of Public Relations’, Journal of Public Relations Research 13(1), 3– 26.

Krimsky, S. and A. Plough: 1988, Environmental Hazards: Communicating Risks as a Social Process (Auburn House, Massachusetts).

Lauzen, M. L. and D. M. Dozier: 1994, ‘Issues Man-agement Mediation of Linkages Between Environ-mental Complexity and Management of the Public Relations Function’, Journal of Public Relations Re-search 6(3), 163–184.

Leichty, G. and J. Springston: 1993, ‘Reconsidering Public Relations Models’, Public Relations Review 19(4), 327–339.

Lindenmann, W. K.: 1988, ‘Beyond the Clipbook’, Public Relations Journal 44(12), 22–26.

Lindenmann, W. K.: 1993, ‘An Effectiveness Yardstick to Measure Public Relations Success’, Public Relations Quarterly 38(1), 7–9.

Lindenmann, W. K.: 1995, ‘Measurement: It’s the Hot-test Thing These Days in PR’, speech given to the PRSA Counselors Academy, Key West, FL. (Avail-able from Ketchum Public Relations, 220 East 42nd Street, New York, NY 10017).

Mark, B. A., J. Salyer and N. Geddes: 1997, ‘Outcomes

Research-Clues to Quality and Organizational

Effectiveness?’, Nursing Clinics of North America 32(3), 589–601.

Marken, G A.: 1990, ‘Corporate Image: We All Have One, But Few Work to Protect and Project It’, Public Relations Quarterly 35(1), 21–23.

Marra, F. J.: 1998, ‘Crisis Communication Plans: Poor Predictors of Excellent Crisis Public Relations’, Public Relations Review 24(4), 461–474.

Marshall, C. and G. B. Rossman: 1995, Designing Quali-tative Research, 2nd edition (Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA).