文化如何影響環保行為?檢視26國人民的環保行為 - 政大學術集成

71

0

0

全文

(2) 論文題目 A Cross-Cultural Analysis: Predicting People’s Environmental Behaviors in 26 Countries. Student: Jenny, Yu-chien Chang Advisor: Tsung-jen Shih. 國立政治大學. 政 治 大 碩士論文. 國際傳播英語碩士學位學程. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. A Thesis Submitted to International Master’s Program in International Communication Studies National Chengchi University. n. a lfulfillment of the Requirement In partial iv n C For the degree h e of Master i Uof Arts ngch. 中華民國 101 年 07 月 July 2012. II.

(3) Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….………………………...….3 Literature Review …………………………………………………………………………...………………………...…7 Defining environmentally responsible behaviors…………………………………………………………………….......8 Sociodemographic factors and environmentally responsible behaviors………………………………………………….8 TPB: Predicting environmentally responsible behavioral intentions at individual level…………………………..……..10 Cultural orientations and environmentally responsible behavioral intentions…………………………………………..14 Cultural orientations models…………………………………………………………………………………………..... 16 Hofstede’s five cultural orientations: Predicting environmentally responsible behavioral intentions at cultural level...17. Method ………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………...24 Data……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……..24 First Level Measures……………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 25 Second Level Measures………………………………………………………………………………………..........….. 27 Analysis…………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………2 9. 政 治 大. Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…32. 立. Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...40. ‧ 國. 學. Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..48. ‧. References …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..51 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………64. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. Index scores for countries and regions from Hofstede’s (1980) ‘Culture's Consequences’……………………………...64 Summary of the model specified (in equation format)…………………………………………………………………...65. Ch. engchi. III. i Un. v.

(4) List of Tables. Table 1. Descriptive statistics of all variables……………………………………………………….…29 Table 2. Model 1: Predicting environmental behaviors at the individual level………………..……….33 Table 3. Variance components of the multilevel models predicting environmental behaviors……….. 34 Table 4. Model 2: Predicting environmental behaviors at the individual level (with random intercept)……………………………………………………………………… 35 Table 5. Model 3: Predicting environmental behaviors at the cultural level…………………………...36 Table 6. Model 4: Predicting cultural values’ moderating effects on individual’s environmental behaviors……………………..……………………………………………………………….38. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. IV. i Un. v.

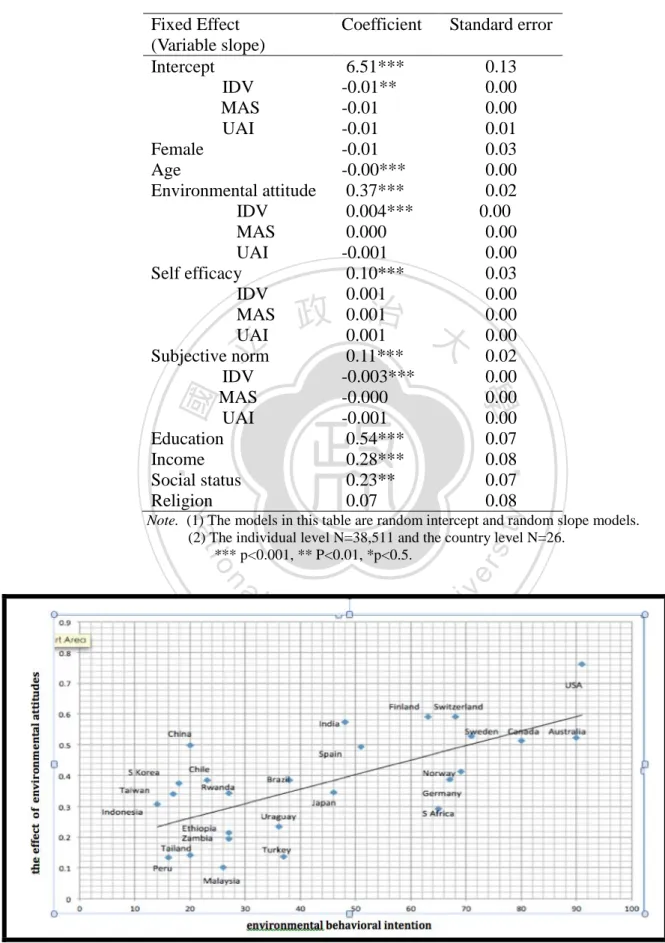

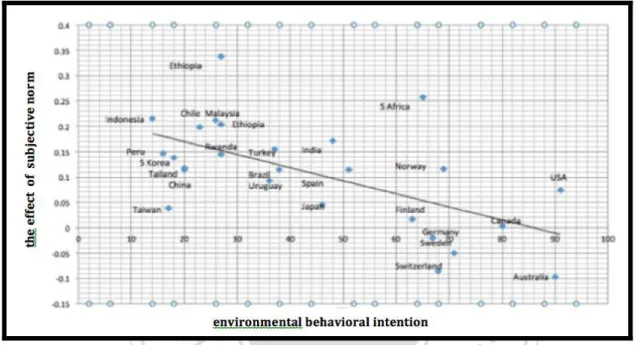

(5) List of Figures Figure 1. Theoretical framework: A multilevel model predicting behavioral intentions 23 Figure 2. A bivariate relationship of the effect of people’s environmental attitude and environmental behavioral intention 38 Figure 3. A bivariate relationship of people’s subjective norms and environmental behavioral intention 39 Figure 4. A bivariate relationship of individualism and people’s environmental behavioral intention 44. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. V. i Un. v.

(6) 1. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. A Cross-Cultural Analysis: Predicting People’s Environmental Behaviors in 26 Countries. Abstract. Environmental protection has become a global issue and attracted the attention of both the general public and governments around the world. Understanding people’s environmental attitude and their behavioral intention, measured as their willingness to pay cost for the environment, is therefore imperative. Research in this field is abundant, but it suffers from at least two limitations. First, previous literature focused mainly on predictors of human behaviors at the individual level and seldom examined the effect of cultural values. In addition, few studies have expanded their research scope beyond Western countries. This study addresses these gaps by investigating the factors, both at the national and individual level, shaping people’s intention to take actions in 26 countries. Employing Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory of planned behavior, the analysis at the individual level examines the impact of environmental attitude, self-efficacy, and subjective norms. At the same time, this study also looks into the effect of three cultural orientations developed by Hofstede, including Individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. The data used in this study were Hofstede’s cultural indices and World Value Survey (WVS) with a total number of 38,511 participants in 26 countries. Hierarchical linear modeling is applied. The result showed that Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory of planned behavior fit well in the study. Three behavioral determinants (attitude, subjective norm, self efficacy) in the theory were positively related to environmental behavioral intentions. Aggregate cultural orientations also accounted for part of variations in relation to environmental behavioral intentions. In more individualistic countries, people were less likely to perform financial sacrifice behaviors for the environment than those in the less individualistic countries. Finally, this study suggested cultural orientations served as moderating variables on people’s environmental attitudes and subjective norms. Environmental attitudes exerted greater impacts on behavioral intentions in more individualistic countries, where the effects of subjective norms were weaker.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Keywords: theory of planned behavior, cultural orientations, environmental behavior.

(7) 2. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(8) 3. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Introduction. Environmental issues have been generating much public and media attention, compelling governments and international companies to establish policies to protect the environment. Policies designed to solve environmental problems must have broad public support to succeed, as a result, understanding public’s environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors plays a critical role in the making of future environmental policy.. 政 治 大. A dominant number of previous studies have put their focus on what people. 立. think about environmental problems and their correlation with pro-environmental. ‧ 國. 學. behaviors without probing into reasons or level of commitment. Additionally, many question asked are rather general instead of focusing on more specific questions, such. ‧. as paying cost for the environment. Dunlap and Scarce (1999) found, a majority of. y. Nat. io. sit. people claimed they support government action to protect environment, yet when it. n. al. er. comes to personal willingness to pay taxes for the environment, the number drops to. Ch. i Un. v. half. Given the widespread distribution of generalized environmental concern, I. engchi. believe it will be worthwhile to focus attention on specific environmental policies. In an attempt to examine the antecedents of the specific pro-environmental behavior and the processes and factors that shape public’s attitudes and actions towards paying cost or taxes for the environment, Fishbein and Ajzen’s the theory of planned behavior (TPB) is used as a major research framework in this thesis. This theory assumes that behavioral intention is the primary antecedent of behavior. Behavioral intention indicates how hard people are willing to perform the behavior. According to the TPB, three factors (attitudes, subjective norms, and self efficacy) determine behavioral intention. The relative importance of these determinants seems.

(9) 4. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. to differ for different target behaviors, as well as different target groups, implying that no general conclusion have yet been drawn on the most significant predictors of environmentally beneficial behaviors (De Groot & Steg, 2007). Moreover, studies based on the TPB scarcely examined values. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) proposed that general determinants such as cultural values can have an important indirect effect on behavior via their effect on the perception and evaluation of situation-specific behaviors, and consequently, on attitudes, subjective norms, and self efficacy. Bowker and Cordell (2004) also proposed that different populations with specific social practices and cultural traits are likely to hold different attitudes toward nature or the environment. Since people are cultivated within a. 政 治 大. societal context, their environmental attitudes are likely to be influenced by the. 立. underlying culture of their society. Therefore, a more complete model of pro-. ‧ 國. 學. environmental behavior should be conceptualized at a higher level such as on the cultural context within which the social-psychological processes occur.. ‧. Furthermore, environmental problems are global in scope, and yet most of the. y. Nat. io. sit. relevant public opinion research done so far has been carried out in advanced,. n. al. er. industrial, societies, usually Western democracies. Researchers in other countries. Ch. i Un. v. have been progressively applying U.S-based research to new cultures. However, there. engchi. has been little comparative study of the different perspectives that are used to examine pro-environmental behavior (Stern, 2000). As the scope of environmental problems expands to include transnational issues such as climate change, researchers around the world will need to be able to examine antecedents of pro-environmental behavior across national boundaries (Cordano, 2010). In studying culture and its impact on the process of shaping pro-environmental attitude and behavior, it is necessary to compare nations. According to Johnson, Bowker, and Cordell (2004), different populations with specific social practices and cultural traits are likely to hold different values on and attitudes toward nature or the.

(10) 5. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. environment. Therefore, cross-cultural comparison of environmental attitudes is of particular importance (Leung & Rice, 2002; Schultz & Zelezny, 1998). Culture is a collective programming of the mind, which distinguishes one group or category of people from another (Hofstede, 1993), and the category of people here refers to nations. In Hofstede’s belief, cultures are not king-sized individuals; instead, they are wholes, and their internal logic cannot be understood in the terms used for the individuals. Though national boundaries do not necessarily correspond to the boundaries of homogeneous societies with a shared culture, there are strong forces towards integration that can produce substantial sharing of culture in nations (Hofstede, 1990). This study, therefore, uses nations as the unit of analysis at the. 政 治 大. aggregate level. In this thesis, I will use Hofstede’s ratings (power distance,. 立. uncertainty avoidance, individualism, and masculinity) to compare the effect of. ‧ 國. 學. different “national norms” on the processes of pro-environmental action. The significant implications of this thesis will be it is one of the few studies. ‧. examines environmentally beneficial behaviors with cost, and a focus on. y. Nat. io. sit. environmentally responsible behaviors in a large cultural context. In addition, the. n. al. er. findings will provide governments around the world with a better understanding. i Un. v. toward people’s environmental sensitivities in different cultures. Furthermore,. Ch. engchi. understanding of a relationship among socio-demographic characters, attitudes, crosscultural values, and behaviors will also help elected officials to make wise public policy decisions. Using the World Value Survey 2005 fourth wave data, I will use hierarchical linear modeling to examine the predictors of pro-environmental behavioral intentions. The first (individual) level draws on Fishbein and Ajez’s theory of planned behavior model and its links between belief, attitude, and pro-environmental behavioral intentions. The second (national) level, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions will be added in the model to examine the relations between cultural orientations and people’s.

(11) 6. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. environmental attitudes, beliefs and behaviors, both on their direct impacts and moderating effects in a large cross-national sample, expanding research scope beyond the context of Western countries.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(12) 7. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Literature Review. The literature on pro-environmental behavior consists of three major streams; one focuses on socio-demographic variables, another on social-psychological constructs, and the other on cultural orientations. A number of studies of the first stream showed consistent effects for education and age and yet weaker and less consistent effects for other variables (Dietz, Stern, & Guagnano, 1998; Jones & Dunlap, 1992; Van Liere & Dunlap, 1980). Furthermore, as noted in Buttel’s (1987). 政 治 大. review of environmental sociology research, social structural variables in general. 立. “explain only modest levels of variance in measures of environmental attitude” (p.. ‧ 國. 學. 473).. Studies of the second stream, which employed social-psychological constructs. ‧. such as values, attitudes, and beliefs, have been more successful in predicting pro-. y. Nat. io. sit. environmental behavioral intentions (Boldero, 1995). These works (e.g., Guagnano,. n. al. er. Stern, & Dietz, 1995; Heberlein & Black, 1981; Taylor & Todd, 1995) are based on. Ch. i Un. v. the premise that individuals’ behavior toward the environment should have something. engchi. to do with what they feel and think with respect to the environment and with respect to pro-environmental action. Several of these works have therefore employed Ajzen’s (1985, 1991) theory of planned behavior that aims to link attitudes with behaviors. In addition, it is reasonable to expect that culture would influence environmental attitudes and behaviors because culture is shared by almost if not all members of a social group and shapes one’s attitudes and behavior. As cultural diversity exists among societies, various dimensions have been proposed to describe cultural orientations (Adler, 1986; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961). Of these dimensions, I adopt Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions in the third stream to.

(13) 8. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. investigate people’s environmental behavioral intentions at the aggregate (countryspecific) level.. Defining Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Environmentally responsible behaviors are said to occur when an individual or group aims “to do what is right to help protect the environment in general daily practice” (Cottrell, 2003, p. 356). Such actions have also been referred to as proenvironmental behavior, environmentally friendly behavior, stewardship behavior, and conservation behavior. According to Stern (2000), there are several types of. 政 治 大. environmentally responsible behavior, which vary according to their location and. 立. extent of visibility: (1) environmental activism, centered in the public realm; (2) non-. ‧ 國. 學. activist political behaviors occurring in the public sphere, including support for certain policy initiatives. The study focuses on the citizen participation in. ‧. environmental policy issues, namely giving part of the premium to protect the. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. environment.. Ch. i Un. v. Socio-demographic Factors and Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. engchi. Relevant literature indicates that socio-demographic variables are consistently used as predictors of behavior. In a study of cohort group differences in environmental concern, Honnold (1984) found decreased levels of environmental concern in almost all age groups since the 1970s. Besides, on examination of the effect of education on environmental knowledge, Ostman and Parker (1987) found significant relationships between education and environmental awareness, environmental knowledge, and subsequent behaviors. In support, Van Liere and Dunlap (1980) stated that education is positively related to environmental knowledge..

(14) 9. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. With regard to gender, McEvoy (1972) argues that because males are more likely to be politically active, more involved with community issues, and have higher levels of education than females, they will be more concerned over environmental problems. Reizenstein, Hills, and Philpot (1974) found that only men were willing to pay more for control of air pollution, and Balderjahn (1988) reported that the relationship between environmentally conscious attitudes was more intensive among men than among women. Additional research suggests a relationship between social class and environmental concern. Some researchers hold the belief that, environmental concern is positively associated with social class as indicated by education and income.. 政 治 大. Because according to Maslow's (1970) hierarchy of needs theory, the upper and. 立. middle classes have solved their basic material needs and thus are free to focus on the. ‧ 國. 學. more aesthetic aspects of human existence. The concern for environmental quality is something of a luxury, which can be indulged only after more basic material needs. ‧. (adequate food, shelter, and economic security) are met. Following Berkowitz and. y. Nat. io. sit. Lutterman’s (1968) study, Henion (1972) also thought that individuals with medium. n. al. er. or high incomes would be more likely to act in an ecologically compatible manner. Ch. i Un. v. due to their higher levels of education and therefore to their increased sensitivity to social problems.. engchi. Lastly, in a study involving 14 countries conducted by Schultz, Zelezny and Dalrymple (2000) suggested that, “respondents who expressed more literal beliefs in the Bible scored significantly lower on the environmental concerns and higher on anthropocentric environmental concerns” (p. 577). Also, White’s (1967) argued that Christian doctrines emphasize human supremacy over nature and Judeo-Christian religious beliefs are fundamentally antienvironmental due to the fact that they believe nature is supposed to be used to serve humans. Another example, Schultz, Zelezny, et al. (2000) examined 14 countries and suggested that, “respondents who expressed.

(15) 10. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. more literal beliefs in the Bible scored significantly lower on ecocentric environmental concerns and higher on anthropocentric environmental concerns” (p. 577). In short, in the context of this literature review, individuals who are younger, males, non Judeo-Christian, and with higher levels of education and higher social status will be more likely to participate in environmentally responsible behaviors. Thus, I will control the effects of these factors so they will not influence the results of the study. Apart from socio-demographic’s influence on behaviors, from the previous research, the theory of planned behaviors also suggests there are three behavior. 政 治 大. determinants that will dominant people’s behavioral intention. Thus, it is needed to. 立. further investigate the three determinants in relationship to people’s environmentally. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. responsible behavioral intention.. io. sit. y. Nat. TPB: Predicting Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intentions at Individual Level. n. al. er. Much of the scholarship on the environmentally responsible behavior draws. Ch. i Un. v. from social-psychological theories of human behavior, including the norm activation. engchi. model (Schwartz, 1977), the theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991). This body of research has proven useful for moving beyond simplistic models of behaviors to incorporate a sequential approach to explaining environmentally responsible behavior. Several researchers have developed models to examine the interactions between cognitive, psychological, socio-demographic, and social situational predictors of environmentally responsible behaviors (Cottrell, 2003; Hines, Hungerford, & Tomera, 1986, 1987; Stern, 2000)..

(16) 11. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. However, in many of the early studies, the premise that a strong relationship exists between attitudes and behavior has not been supported (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1973). McGuire and Walsh (1992) stated that, “the results of the research regarding attitudinal relationships have varied and have been inconclusive” (p. 1). Of primary concern has been the question of whether attitudes, either positively or negatively, influence behavior (Manfredo, Yuan, & McGuire, 1992). In support, Manfredo et al. (1992) wrote that “research in the late 1960s and early 1970s showed weak attitudebehavior relationships, and psychologists debated the utility of the attitude concept” (p. 158). Attitudes are multidimensional, consisting of a number of interrelated constructs. Human behavior is difficult to predict, and single constructs such as. 政 治 大. attitudes cannot accurately forecast behavior. Research efforts now are better served. 立. to focus more on the question of which attitudes predict behavior rather than if. ‧ 國. 學. attitudes predict behavior. Thus, this article is intended to review Fishbein and Ajzen’s theory once again on specific behavioral intentions and see if it can also be. ‧. applied to environmental issues.. y. Nat. io. sit. In the late 1970s, Fishbein and Ajzen developed a model of behavioral. n. al. er. intentions based on their TRA. The theory was developed to both predict and explain. Ch. i Un. v. behaviors of social relevance that are under a person's volitional control. This. engchi. expanded model is appropriate for both volitional and non-volitional behaviors. In both theories, the central variable is intention to perform a behavior, which is considered as the immediate determinant of the behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Intentions are assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence a behavior; they are indications of how hard people are willing to try and of how much of an effort they are planning to exert in order to perform the behavior. As a general rule, the stronger the intention to engage in a behavior, the more likely the behavior will be performed. For example, several studies have demonstrated the relations between behavioral intentions and actual behaviors (e.g., Boldero, 1995; Sparks & Shepherd,.

(17) 12. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. 1992; Taylor & Todd, 1995, 1997). For example, Boldero (1995) found that attitudes toward recycling predicted the recycling intentions and intentions to recycle newspapers directly predicted actual recycling. In another study, attitudes toward green consumerism, subjective norms, and self efficacy were all significantly related to individuals’ intentions to consume organic vegetables (Sparks & Shepherd, 1992). Also in line with the theory, Taylor and Todd (1995) found that both attitudes toward recycling and self efficacy were positively related to individuals’ recycling and composting intentions. In another study, Cheung, Chan, & Wong (1999) found all three predictor variables (i.e., attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy) to predict intentions to recycle wastepaper and in turn recycling intentions predicted actual. 政 治 大. recycling behavior. Some researchers have even successfully applied the enhanced. 立. version of the theory of reasoned action that Ajzen (1991) labeled the theory of. ‧ 國. 學. planned behavior to single culture pro-environmental behavior (Boldero, 1995; Oom Do Valle, Rebelo, Reis, & Menezes, 2005; Taylor & Todd, 1995, 1997) and to cross-. ‧. cultural pro-environmental behavior (Oreg & Katz-Gerro, 2006). Three determinants. y. Nat. io. sit. of the behavioral intention are proposed: attitude, subjective norm, and self-efficacy.. n. al. er. Attitude refers to the evaluation of the behavior, which is an antecedent of. Ch. i Un. v. behavioral intention. Attempts to predict behavior from attitudes are largely based on. engchi. a general notion of consistency. It is usually considered to be logical or consistent for a person who holds a favorable attitude toward some object to also perform favorable behaviors, and not to perform unfavorable behaviors with respect to the object. Similarly, a person with an unfavorable attitude is expected to perform unfavorable behaviors, but not to perform favorable behaviors. A “classical” attitude-behavior paradigm would assume that behaviors can be predicted by attitudes, since behavioral intentions refer to the beliefs enacting a particular behavior, which will confer the benefits that one seeks (Bandura, 1986). In another words, attitude is jointly determined by strengths of belief about the.

(18) 13. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. consequences of the behavior and evaluations of these consequences. More specifically, behavioral intentions are conceptualized as the product of a mental calculus that people perform between the benefits of taking actions and costs associated with those actions (Rogers, 1975; Rosenstock, 1974). To the extent that outcome expectations can be thought of as beliefs that lead to behaviors. In TPB theory, behavioral intention can be treated as part of attitudes toward a behavior. For example, Taylor and Todd (1995) found that both attitudes toward recycling and perceived behavioral control were positively related to individuals’ recycling and composting intentions. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis. The second determinant to the behavioral intention in the theory of planned. 政 治 大. behavior is subjective norm. Norms are fundamental to understanding social order as. 立. well as variation in human behavior (Campbell, 1964; Durkheim, 1951). Subjective. ‧ 國. 學. norm indicates that people may search for social support for their behaviors, reflects the dominant or most typical attitudes, expectations and behaviors.. ‧. Festinger (1954) argued that persons use social comparison processes to. y. Nat. io. sit. evaluate their own beliefs relative to the social reality. These social comparison. n. al. er. processes occur when people look to others for guidance on how to behave in a. Ch. i Un. v. situation, particularly when the situation is characterized by ambiguity. When people. engchi. perceive that social sanctions exist for noncompliance, they are more likely to conform if they also perceive that the behavior is widespread among their peers. Therefore, the subjective norms maintained by an individual’s social network can induce behavior in conflict with the individual’s own attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). In the case of environmental protection, it is also of interest that uncertainty about the consequences of behavior can reinforce the need for social support. When the physical reality is ambiguous, the social reality may assume increased importance for the individual’s choices (Festinger, 1954). Thus, the search for social support for one’s own environmental behavior may be an important determinant of that behavior..

(19) 14. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Self-efficacy is the third determinant to the behavioral intention. It refers to the extent to which people believe that they have the ability to affect outcomes through their own actions (Rotter, 1966). The present view of perceived behavioral control, is most compatible with Bandura’s (1977, 1982) concept of perceived self-efficacy which “is concerned with judgments of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations” (Bandura, 1982, p122). These investigations have shown that people’s behavior is strongly influenced by their confidence in their ability to perform it. It is not restricted to behavior in an environmental context and represents an individual’s perception of whether he or she has the ability to change his or her own environment. The concept is based on the. 政 治 大. belief that some individuals do not attempt to make any change because they attribute. 立. changes to chance or to the power of others rather than to their own behavior.. ‧ 國. 學. Individual concerns about the environmental issues might not easily translate into proenvironmental behaviors; however, individuals with a strong belief that their. ‧. environmentally conscious behavior will result in a positive outcome are more likely. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. to engage in such behaviors in support of their concerns for the environment.. Ch. i Un. v. H1: Environmental attitude, subjective norm and self efficacy will be positively. engchi. associated with environmentally responsible behavioral intention.. Cultural Orientations and Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention. Differing perceptions of environmental issues are in part driven by differing worldviews or values systems (Dietz, Stern, & Rycroft, 1989). It is often suggested that environmental attitudes and environmental behavior are related to people’s values (Dunlap, Grieneeks, & Rokeach, 1983; Karp, 1996; Stern, 2000). Values are typically conceptualized as important life goals or standards that serve as guiding principles in.

(20) 15. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. life. As such, they may provide a basis for the formation of attitudes and act as guidelines for behavior. That is, people consider implications of behavioral choices for the things they value. Intra-individual processes are central when trying to understand why and when individuals act in favor of the environment. Nevertheless, a more complete model of pro-environmental behavior should consider the social context within which the social-psychological processes occur. In this spirit, Stern, Dietz, Kalof, & Guagnano (1995) stressed the importance of considering the cultural values within which individuals are embedded, based on the belief that cultural orientations shape individuals’ experiences and ultimately their personal values, beliefs, and behaviors.. 政 治 大. The hierarchical model presented by Stern, Dietz, Kalof, et al. (1995) extends Ajzen’s. 立. (1985, 1991) models, and although the authors adopt the notion that attitudes guide. ‧ 國. 學. intentions, which in turn guide behavior, they also suggest that individuals’ worldviews precede their attitudes, that their personal values precede their. ‧. worldviews, and that their position within the social structure precedes their values. In. y. Nat. io. sit. a following study, Dietz et al. (1998) tested the relationships between social structure,. n. al. er. worldviews, attitudes, and environmentally relevant behaviors, such as willingness to. Ch. i Un. v. sacrifice for environmental quality and collective or political behavior. The results. engchi. demonstrated that personal beliefs about nature are different in different cultures, which will influence people’s environmentally relevant behaviors. It suggested the necessity to include cultural orientations as a valid predictor of people’s environmental behaviors. Most importantly, although their model elaborates on previous attitudebehavior concepts, all of the variables remain at the level of the individual. In “position within the social structure” Stern, Dietz, Kalof, et al. (1995) referred to socio-demographic variables—such as age, income, and education—all of which are individual-level characteristics. Similarly, values and worldviews have also been.

(21) 16. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. conceptualized at the individual level. Although Stern, Dietz, Kalot, et al.’s (1995) desire to broaden our understanding of the sources of pro-environmental behavior, it is suggested that the context within which individuals behave should be conceptualized at a level higher than the individual. To truly complement socialpsychological variables such as attitudes and personal beliefs, new variables that are considered should be external to the individual. The culture within which individuals behave constitutes a meaningful context for the creation of the attitudes and personal beliefs will ultimately guide behavior.. Cultural Orientations Models. 立. 政 治 大. Cultural orientations denote preference of any one thing before or above. ‧ 國. 學. another (Brown, 1984). They are usually derived using evaluative scales such as good-bad, likable-dislikable, moral-immoral, and pleasant-unpleasant (Tesser &. ‧. Martin, 1996), and are integrated patterns of meanings, beliefs, norms, symbols, and. y. Nat. io. sit. values that individuals hold within a society, with orientations representing perhaps. n. al. er. the most central cultural feature (Hofstede, 2001; Schwartz, in press). In other words,. i Un. v. orientations “express shared conceptions of what is good and desirable in the culture,. Ch. engchi. the cultural ideals” (Schwartz, in press, p. 2). Parallel to individual-level values, cultural orientations involve enduring goals that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives (Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992), and contribute to the formulation of individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Although cultural orientations are often inferred from the aggregation of individuals’ personal values within a society (e.g., Inglehart, 1997; Schwartz, 1994), they are nevertheless distinct from them. As far as personal values are concerned, individuals can vary from one another in their value priorities. Indeed, all of the research to date on values and environmentalism has considered such individual.

(22) 17. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. differences in individual values and attempted to predict personal attitudes and behaviors from personal values (e.g., Axelrod, 1994; Karp, 1996; McCarty & Shrum, 1994; Poortinga, Steg, & Vlek, 2004). On the other hand, cultural orientations represent the common and shared ideals of individuals within a given society. Differences in cultural orientations can therefore be observed only between societies rather than between individuals. Three most widely employed models of cultural orientation systems are Hofstede’s (2001) five-dimensional theory, Inglehart’s (1997) theory of materialist and postmaterialist values, and Schwartz’s (1994, in press) theory of cultural value orientations. Works by all three have demonstrated orientation differences across. 政 治 大. countries such that different societies tend to emphasize different goals (Hofstede,. 立. 2001; Inglehart, 1977; Schwartz, 1994). Accoringly, research shows that these. ‧ 國. 學. contexts influence behavioral patterns at the individual level (Hofstede, 2001; Inglehart, 1997; Schwartz, in press).. ‧. Although all three theories include values that bear relevance to environmental. y. Nat. io. sit. attitudes and behaviors of the three, Hofstede’s five cultural orientation theory. n. al. er. appears most directly related to the context of the present study, as it includes an. Ch. i Un. v. indices reference of different cultural distances. This allows one to examine cultural. engchi. orientations’ impact at level higher than merely a personal one. I will therefore use Hofstede’s cross-national indices to analyze the comparisons between countries.. Hofstede’s Five Cultural Dimensions: Predicting Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intentions at Cultural Level Hofstede (1980a, p. 25) defined culture as ‘the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another’. His framework was developed using data from over 116,000 morale surveys from over 88,000 employees originally from 72 countries and later reduced to 40 countries that.

(23) 18. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. had more than 50 responses each. Data was collected in 20 languages at IBM between 1967 and 1969 and again between 1971 and 1973. He later expanded the database adding 10 countries and three regions from Arab countries to East and West Africa). Hofstede's (1980, 1984) initial conceptualization was a one-dimensional view of human values, with individualism and collectivism at the opposite ends of a continuum. Nations and cultures were defined as residing at one or the other of those extremes or somewhere between the two. In the application of these concepts, a majority of the focus has been placed on explaining cultural or national differences using these constructs (Gudykunst & Ting-Toomey, 1988). These applications range from psychological development to adaptation to social norms, self-identity and group. 政 治 大. membership, and behavioral responses (e.g., Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, &. 立. Tipton, 1985; Dumont, 1986; Gurevich, 1995).. ‧ 國. 學. Hofstede characterizes the sharedness of national culture by a statistical average based on individuals’ views, which is called a ‘national norm’ (Hofstede, 1980). His. ‧. ratings of national character reflecting shared perceptions of the personality traits of. y. Nat. io. sit. the typical member of the culture are one of the most popular measures to perceive. n. al. er. and interpret countries in the world, which permits the culture of a country to be. Ch. i Un. v. summarized across a limited number of common dimensions. As comparisons across. engchi. countries are controlled by matching respondents on age, gender, education, and percentage of the respondents who hold positions in higher management, it is assumed that systematic and stable differences between respondents from different countries can only be explained by the culture of the country (Huo &Randall, 2005). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are operationalized as the mean level of traits in individuals from the culture. In the 1980s, a fifth dimension was added to the four, long-term versus short-term orientation, which was based on a study among students in 23 countries around the world, using a questionnaire designed by Chinese scholars. Values associated with long-term orientation referring to a positive, dynamic, and.

(24) 19. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. future oriented culture with four ‘positive’ Confucian values. Short-term orientation, however, represents a negative, static and traditional and past-oriented culture. To date, scores on the fifth dimension are only available for part of the countries covered by the first four. Therefore, in the present thesis, I will leave out the fifth orientation. Power Distance: “Degree to which members of a society accept as legitimate that power in institutions and organizations are unequally distributed (Gouveia & Ros, 2000, p.26).” This represents a society’s level of inequality is endorsed by the followers as much as by the leaders. A society’s power distance level is bred in its families through the extent to which its children are socialized toward obedience. Members within higher power distance society have tendency to follow group norms. 政 治 大. and goals, and expect other members to perform the same behavior and thus have. 立. greater beliefs in making differences by engaging in the behavior at the aggregate. ‧ 國. 學. level although the behavior is performed individually. An essential attribute of a high power distance society is that individuals will subordinate their personal interests to. ‧. the goals of their society. In-group membership is stable even when the in-group. y. Nat. io. sit. places high demands on the individual. Individuals belonging to an in-group share. n. al. er. common interests and seek collective outcomes or goals. A high power distance. Ch. i Un. v. society emphasizes goal attainment, cooperation, group welfare, and in-group harmony.. engchi. Uncertainty Avoidance: “Degree to which members of a society are uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity (Gouveia &Ros, 2000, p.26).” This leads them to support beliefs that promise certainty and to maintain institutions that protect conformity. According to Kuhn in 2000, when the negative effect of certain environmental hazards is not clearly or immediately apparent, members in uncertainty-avoiding societies may tend to “put it to the back burner” and attend to more relevant, salient worries in their everyday lives. Also, when the risks from a certain environmental hazard are uncertain, many people use the uncertainty to justify.

(25) 20. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. their discounting of the seriousness of any possible threat. Masculinity/Femininity: “A preference for accomplishment, heroism, severity and material success as opposed to a preference for relationships, modesty, attention to the weak and quality of life (Gouveia &Ros, 2000, p.26).” Individuals in a masculine society tend to compete with others for status, which depends on their accomplishments much more than on their group memberships. I suspect that this type of individual is not very conducive to environmental friendliness. On the other hand, a feminine society implies cooperation, helpfulness, and consideration of the goals of the group relative to the individual, which means an individual may forego individual motivations for that which is good for the group. According to Diamond. 政 治 大. and Orenstein (1990), a feminine society is potentially more environmental than. 立. masculine society because of a biospheric orientation (Diamond & Orenstein, 1990).. ‧ 國. 學. This argument may also be read either as a claim that women assign greater weight to biospheric values (care more about the biosphere) or as a claim that women, possibly. ‧. because they are more “rooted” in natural environment, are more likely to become. y. Nat. sit. aware of the consequences of human activity for the biosphere.. n. al. er. io. Individualism/Collectivism: Originated from Hofstede’s work (1980), the. Ch. i Un. v. notion of individualism versus collectivism illustrates differences in basic beliefs that. engchi. individuals hold with respect to their interaction with others, priority of group goals, and perceived importance of unity with others. In general, people from individualistic cultures tend to be independent and self-oriented whereas those from collectivistic cultures are more interdependent and group-oriented. Individuals with a more collectivistic tendency are interdependent with members of their culture and their behaviors are shaped primarily on the basis of group norms and goals. People who have a more collectivistic orientation also rate themselves higher on collectivist traits including respectfulness, obedience, dutifulness, reciprocity, self-sacrifice, conformity, and cooperativeness than those from individualistic cultures. These collectivistic.

(26) 21. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. individuals might expect other members to perform the same behavior and thus have greater beliefs in making differences by engaging in the behavior at the aggregate level although the behavior is performed individually. According to the above, Hofstede’s cultural orientations, introduced as the contextual antecedents, are expected to affect people’s environmental attitude, subjective norm and self-efficacy, and also expected to predict individuals’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention. Therefore, I propose the following research question.. RQ1: How will Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculinity, and Individualism relate to the. 政 治 大. environmentally responsible behavioral intention?. 立. ‧ 國. 學. In addition, it is considered the possibility that the pro-environmental behaviors might exist above and beyond the direct effects. Therefore, after examining the direct. ‧. effects of individual and cultural influences on people’s environmentally responsible. y. Nat. sit. behavioral intention, it is intended to further examine if cultural orientations will. n. al. er. io. serve as a moderating role influencing individuals’ beliefs on environmentally. Ch. i Un. v. responsible behaviors. There are few studies which have examined country level. engchi. moderating effects, which seems curious for a framework that was conceived to explain these differences. Hofstede’s cultural values have important effects on micro and macro level relationships across countries because country level phenomena are far removed antecedents for the relationships being examined. Kogut and Singh (1988) conceptualize country level cultural distance as a main effect, which may have led subsequent researchers to exclusively investigate such effects, rather than moderating effects. Luo et al. (2001), however, demonstrated cultural distances have interesting effects as a moderator. A study by Bagozzi, Wong & Bergami (2000) showed that TRA in several cultures and found that the effect size for the influence of subjective.

(27) 22. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. norms varied for members of different cultural groups. Thus, it is suggested that researchers should consider cultures’ moderating role, which is examined as the following research questions in the study.. RQ2: Do pro-environment attitude, subject norm, and self-efficacy have different effects in different countries?. RQ3: How do the cultural orientations moderate the effect of pro-environmental attitude, subject norm, and self-efficacy?. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(28) 23. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. HOFSTEDE’S CULTURAL ORIENTATIONS Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism, Masculinity. ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOR V1. IMPORTANCE TO LOOK AFTER ENVIRONMENT. 立. SUBJECTIVE NORM. V1. WOULD GIVE PART OF MY INCOME FOR ENVIRONMENT V2. INCREASE IN TAXES IF EXTRA MONEY USED TO PREVENT ENVIRONMENT. sit. io. n. 26 countries al iv n Ch engchi U. er. Nat. y. ‧. V1. HOW MUCH FREEDOM YOU FEEL. ‧ 國. SELF-EFFICACY. PROENVIRONMENT BEHAVIORAL INTENTION =PROENVIRONMENTAL ACTUAL BEHAVIOR. 學. V1. ONE OF MAIN GOAL IN LIFE HAS BEEN TO MAKE MY PARENTS PROUD V2. LIVE UP WHAT MY FRIENDS EXPECT. 政 治 大. FIGURE1. Theoretical framework: A multilevel model predicting behavioral intentions..

(29) 24. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Methods Data. In light of the multi-level design of this study, the data was gathered from different sources. For information at the individual level, this thesis mainly drew on the World Values Survey (WVS) 2005 fourth wave dataset, for it was the latest dataset at the time I composed this dissertation. WVS, one of very few survey programs collecting public opinion information. 政 治 大 consists of representative national surveys of the basic values and beliefs of the 立. worldwide through interviewing representative national samples of individuals,. ‧ 國. 學. general public in a large number of countries in at least one of its waves. For each country there are interviews with a representative national sample of at least 1000. ‧. people, which are weighted to reflect each country’s population. Data collection for. Nat. sit. y. WVS surveys is mostly conducted through face-to-face interviewing. The data. n. al. er. io. collection period for the WVS 2005 was April 1, 2005 through December 31, 2006, with 57 nations included.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. A key feature of the WVS data is that they are available for individuals and have not been aggregated. More importantly, a single survey questionnaire has been used across a large number of countries according to scientific sampling procedures. Data was obtained not only on individual self-rated behaviors, but also on household income, social-demographic variables (i.e. age, sex and academic degree), and other variables pertinent to the Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory. Consequently, these data provide an ideal basis for an empirical test of people’s environmental behaviors in different countries. Research conducting large scale cross-national comparisons often raises questions about validity and reliability. However, by using the WVS data there.

(30) 25. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. are well-known difficulties and errors associated with cross-cultural surveys in many aspects of the design, such as the questions, the sampling, the translations and the interviewing techniques (Jen, Jones, & Johnston, 2009). The validity and reliability limitation in cross-cultural comparability in survey research can be greatly minimized with carefully designed questionnaires and carefully worded and constructed questions (Jen, Jones, & Johnston, 2009). On the other hand, information related to the aggregate characteristics of each country was collected based on Hofstede’s cultural indices (Hofstede, 1980). Specifically, I used the four cultural orientation scores— power distance (PDI),. 政 治 大. uncertainty avoidance (UAI), individualism (IDV), and masculinity (MAS). It is. 立. noteworthy that although WVS 2005 contains 57 countries, I analyzed only 26. ‧ 國. 學. countries because of the availability of Hofstede’s cultural indices and a lack of. ‧. information in several countries on the dependent variable and explanatory variables.. sit. y. Nat. The countries included in this study are as follows: Spain, USA, Canada, Japan, South. io. al. er. Africa, Australia, Norway, Sweden, Finland, South Korea, Swizerland, Brazil, Chile,. n. India, China, Taiwan, Turkey, Peru, Uragray, Tailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Ethiopia,. C Rwanda, Zambia, and Germany. h. engchi. i Un. v. First Level Measures. Pro-environmental behavioral intention, the dependent variable of this study, is conceptualized as behaviors that will minimize the negative impact of one’s actions on the natural and built world. In this thesis, proenvironmental behaviors were measured as an additive index of two variables (M=6.47; SD=2.23; Correlation= .61). The respondents were asked about the extent to which they agree with the following.

(31) 26. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. two statements—“ I would give part of my income for the environment,” and “your opinion on the increase in taxes if extra money used to prevent environment.” The respondents responded to the statements on a five-point scale, with 1 being “not important at all” and 5 being “very important.” Environmental attitude is defined as the general affective response to a denotable psychological object. In this thesis, environmental attitudes were measured by the question “importance to look after environment” (M=3.77; SD=1.03). The question ranges from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “strongly agree” and 5 indicating “strongly disagree.” I reverse coded the question such that a higher value would. 政 治 大. indicate a more favorable attitude towards the environment.. 立. Self-efficacy refers to the extent to which people believe that they have the. ‧ 國. 學. ability to affect outcomes through their own actions. In this thesis, to measure self-. ‧. efficacy (M=4.33; SD=0.82), the respondents were asked about “how much freedom. being “a great deal.”. io. al. er. sit. y. Nat. they think they have.” The answer ranges from 1 to 5, with 1 being “not at all” and 5. Subjective norm is defined here as a norm maintained by significant others, not. n. iv n C by expectations of the society. Ajzen h &e Fishbein i U define subjective norm as a n g c h(1980). function of (a) normative beliefs and (b) the person’s motivation to comply with each of the referents’ expectations. In this thesis, social norms were measured as an additive index of two variables (M=6.85; SD=1.90; Correlation=.29). The respondents were asked about the extent to which they agreed with the following two statements—“one’s goal in life has been to make parents proud” and “one’s goal in life is to live up to what friends expect.” Both questions range from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “strongly agree” and 5 indicating “strongly disagree.” I reverse coded the two questions such that a higher value would indicate more willingness to comply.

(32) 27. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. with the expectation of others.. Second Level Measures. Power distance (PDI) is a dimension that measures perceptions of subordinate’s fear of disagreeing with superiors. The fundamental issue in PDI is how society deals with the fact that people are unequal. To measure PDI, the respondents are asked, “How frequently in your experience that employees being afraid to express disagreement with their managers?” (see Appendix1 of Hofstede, 1980, for complete. 政 治 大 data.) Note that, after analysis, I found PDI and IDV have high contradictory 立. ‧ 國. 學. correlation (-0.65), creating concerns for multicollinearity. Therefore, I decided to leave out PDI and preserve IDV in the analysis.. ‧. Uncertainty avoidance (UAI) is a dimension that measures tolerance for. sit. y. Nat. uncertainty or ambiguity and the degree of need for taking action to reduce the. n. al. er. io. uncertainty. Hofstede examined three components of uncertainty avoidance: 1) the. i Un. v. degree to which people are willing to break company rules, 2) the degree to which. Ch. engchi. employees want employment stability, and 3) the frequency of feeling nervous or tense at work. For example, to measure UAI, respondents are asked, "How often do you feel nervous or tense at work?" (see Appendix1of Hofstede, 1980, for complete data.) Individualism (IDV) is a measure of the extent to which an individual's selfconcept is perceived in individual terms or in collective terms. People who are high on IDV like having a job which allows them time for personal and family life, which provides a personal sense of accomplishment, and which gives them freedom to adapt their own approach to the job. For example, to measure IDV, respondents are asked,.

(33) 28. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. "How important it is to you to have sufficient time left for your personal or family life?'" (see Appendix1 of Hofstede, 1980, for complete data.) Masculinity (MAS) is more complex than the three other dimensions. Respondents scoring high on MAS place relatively higher value on such learned "masculine" work goals as assertiveness, advancement, recognition, and earnings. A low MAS score reflects a higher value on nurturing, interpersonal relations, and cooperation. For example, to measure this construct, respondents are asked, "How important it is to you to have an opportunity for high earnings?" (see Appendix1 of Hofstede, 1980, for complete data.). 政 治 大. It is worth noting that to some extent power distance and individualism are. 立. conceptually and methodologically overlapping with each other. Conceptually, power. ‧ 國. 學. distance refers to the amount of power authorities over subordinates and research. ‧. suggests that people in collectivistic cultures are more deferent to authorities (Parkes,. sit. y. Nat. Bochner, & Schneider, 2001). Also methodologically, the scores of power distance. io. al. er. are statistically highly associated with those of individualism (r =-0.46). Therefore, to. n. avoid multicolinearity (Cohen, Cohen, Atkin, & West, 2003), power distance is left out of the analysis section.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(34) 29. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Table1 Descriptive statistics of all variables. Variable. M. SD. Minimum. Maximum. Proenvironmental behavioral intention. 6.47. 2.23. 2. 10. Female. 0.52. 0.50. 0. 1. Age. 42.22. 16.78. 15. 98. Environmental attitude. 3.77. 1.03. 1. 5. Self efficacy. 4.33. 0.82. 2. 5. Subjective norm. 6.85. 1.90. 2. 10. Education. 0.15. 0.36. 0. 1. 0. 1. 0. 1. 0. 1. Individual-level variables. Income. 立. Social status Religion. 治 0.22 政 0.05 大 0.20 0.40 0.49. 44.42. 24.47. 14. 91. 46.58. 18.88. 5. 95. 61.73. 19.57. 29. 100. Cultural variables IDV MAS UAI. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Analysis. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 0.42. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In this study, I will use hierarchical linear modeling as the analytical approach. Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) or multilevel analysis can be viewed as a modified version of multiple linear regression designed to deal with data with a hierarchical clustering structure (Osborne, 2007). This nested structure is common to many sample designs in which observations are not independent. Ordinary regression analysis (OLS), treating the data as if all observations are independent, produces unreliable standard errors and hypothesis tests because of model misspecification (Osborne, 2007). Multilevel or hierarchical linear models explicitly take into account.

(35) 30. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. the nested data and the related dependency structure by allowing unexplained variability between level-one and level-two. This means that random residuals are postulated for both levels. A classical example of a multilevel structure is provided by educational data where pupils are nested within schools, a two-level structure. It assumes that pupils from the same school do not resemble each other more than pupils attending different schools. In multilevel terminology, the pupils or measurement occasions constitute the first or lowest level, the schools or individuals the second or highest level. In environmental research, there is a growing awareness of the advantages of. 政 治 大. multilevel analysis and the necessity to use it. When examining personal behaviors. 立. across culture, the data have a hierarchical structure: personal beliefs and behaviors. ‧ 國. 學. are nested within cultures.. ‧. Therefore, HLM makes it possible to simultaneously model individual-level. sit. y. Nat. and cultural- level variables and to estimate the percentage of total variance in the. io. Coefficient [ICC]).. al. er. outcome measure that results from each (quantified as the IntraClass Correlation. n. iv n C U software (Raudenbush, Bryk, A multilevel design was applied h eusing n gHLM c h i6.06. Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). The analysis will be conducted as a two-level model, with individuals at Level 1 and cultures at Level 2. Level-one model specifies how environmental attitude, individual subjective norm, and self-efficacy influence environmentally responsible behavioral intention, whereas, level-two model specifies the relations of Hofstede’s cultural orientations and environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. In this study, the hierarchical analyses included five models, from a null model to a random slope model with level 2 predictors. They are (1) a null model, (2) Model.

(36) 31. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. 1: a fixed effect with level-1 predictors, (3) Model 2: a random intercept model with level-1 predictors, (4) Model 3: a random intercept model with both level-1 and level2 predictors, (5) Model 4: a random slope model, and (6) Model5: a random slope model with level-2 variables predicting the differential slopes of level-1 variables.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(37) 32. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Results. The analysis proceeded in several steps. First, a null model, a model without explanatory variables, was estimated. In the null model, I investigated how much of the total variance can be attributed to the individual level and how much to the cultural level. The variance attributable to the cultural level (0.42) turns out to be much smaller than the variance among individuals within countries (4.53). The value. 政 治 大. of the ICC, which is .042 / (.042 + 4.53) = .08: About 8% of the total variance exists. 立. at the national level.. ‧ 國. 學. Next, the hypotheses and research questions are systematically tested and answered in several models. In Model 1 (See Table2), I examined the extent to which. ‧. individual-level explanatory variables are related to individual-level environmental. y. Nat. io. sit. behavioral intention, the dependent variable of this study. Before presenting the. n. al. er. results in relation to H1, I will talk about the contributions of demographic variables,. Ch. i Un. v. included in this study as controls, to people’s willingness to take actions.. engchi. The results indicated that age is negatively related to environmental behaviors (β=-0.01), indicating that younger people are more willing to pay for the environment. Income is positively related to environmental behaviors (β= 0.35), suggesting that higher income groups are more likely to support financial sacrifices for the environment. Additionally, individuals who obtain higher education degree are also more likely to engage in activity beneficial to the environment (β = 0.59). Higher levels of social status are also positively associated to environmental friendly behaviors (β=0.22). Non-Judeo Christians are negatively related to environmentally.

(38) 33. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. responsible behavioral intention (β=-0.37). However, gender is not significantly related to environmental behavioral intentions.. Table 2. Model 1: Predicting environmental behaviors at the individual level Fixed Effect. Coefficient. Standard error. (Variable slope) Intercept. 6.80***. 0.19. Female. -0.00. 0.03 0.00. 0.38***. 0.03. Subjective norm. 0.11***. Education. 0.56***. Religion. 0.07. 0.35**. al. n Social status. 0.02. 0.12. er. io. Income. 0.03. ‧. 0.12***. Nat. Self efficacy. 學. ‧ 國. Environmental attitude. y. 立. 治 政 -0.01* 大. sit. Age. Ch. 0.22**. engchi -0.37**. i Un. v. 0.08 0.13. Note. (1) The model in this table is a fixed effect model. (2) The individual level N=38,511 and the country level N=26. *** p<0.001, ** P<0.01, *p<0.5..

(39) 34. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. H1 stipulated that individuals’ environmental attitude, subjective norm and self efficacy will be positively associated with environmentally responsible behavioral intention. This hypothesis was tested in model 1 (see Table 2), which included all individual-level variables. The results showed that individuals’ environmental attitude (β =0.37, p<0.001), subjective norm (β =0.10, p<0.001), and self efficacy (β =0.12, p<0.001). 政 治 大. are all positively related to their environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. H1 is, therefore, supported.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Table 3.. Variance components of the multilevel models predicting environmental behaviors. 25 22 22 22 22. Predicting the random slope of “environmental behavior” with 2nd level variables 0.014. 22. ***. 22 22. *** ***. y. er. n. al. sit. Null model Intercept Fixed effect model Level 1 predictors + random intercept model Level 1 predictors + random intercept model + Level 2 predictors Random slope of “environmental behavior” Random slope of “subject norm” Random slope of “self efficacy”. ‧. 0.41 0.34 0.014 0.007 0.014. P Value *** *** *** *** *** *** ***. io. Model 5. df. Nat. Null Model Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4. Variance Component 0.43. Ch. engchi nd. i n U. v. Predicting the random slope of “subject norm” with 2 level variables Predicting the random slope of “self efficacy” with 2nd level variables Note. The individual level N=38,511 and the country level N=26. *** p<0.001, ** P<0.01, *p<0.5.. 0.007 0.014. 25.

(40) 35. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. The impact of cultural variables is also significant to note. However, before testing the impact of cultural factors, it is necessary to prove that there exists enough variance across countries in terms of people’s willingness to take actions. This crosscountry variation is tapped by the variance component of the random intercept. Technically, this was tested by making the intercept in Model 1 was made random, which constituted Model 2 of this study. The result showed that the variance component associated with the random intercept is statistically significant (see Table3, p<0.01), suggesting that variation exists among countries. In other words, the level of willingness to take actions varies between countries.. 立. 學. ‧ 國. Table 4.. 政 治 大. Model 2: Predicting environmental behaviors at the individual level (with fixed intercept) Coefficient. Female. -0.00. n. -0.00***. Environmental attitude. Ch. e n0.37*** gchi U. sit er. io. al. y. 6.52***. Nat. Age. Standard error. ‧. Fixed Effect (Variable slope) Intercept. v ni. 0.16 0.03 0.00 0.03. Self efficacy. 0.12***. 0.03. Subjective norm. 0.10***. 0.02. Education. 0.56***. 0.07. Income. 0.28**. 0.08. Social status. 0.23**. 0.08. Religion. 0.05. 0.09. Note. (1) The model in this table is a fixed intercept model. (2) The individual level N=38,511 and the country level N=26. *** p<0.001, ** P<0.01, *p<0.5..

(41) 36. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. In order to answer RQ1, which explored the influence of UAI, MAS, and IDV on the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions, cultural variables were added on top of Model 2 to investigate if cultural values have any direct effect on environmentally responsible behavioral intention, which constituted Model 3 of this study. The results suggested that IDV exhibited a significantly negative effect on environmental behavioral intentions (see Table 5, β =-0.01, p<0.05), suggesting that in higher individualistic countries, people are less likely to perform environmental protection behaviors. However, MAS and UAI showed no significant relations to environmentally responsible behaviors.. 政 治 大. 立. Table 5.. ‧ 國. Fixed Effect (Variable slope) Intercept. Coefficient. ‧. -0.01. al. Ch. -0.00. e n-0.00*** gchi. y. 0.00. sit. -0.01. n. Age. 0.00. er. io. Female. 0.16. -0.01*. Nat. UAI. Standard error. 6.52***. IDV. MAS. 學. Model 3: Predicting environmental behaviors at the cultural level. i Un. v. 0.01 0.03 0.00. Environmental attitude. 0.37***. 0.03. Self efficacy. 0.12***. 0.03. Subjective norm. 0.10***. 0.02. Education. 0.56***. 0.07. Income. 0.28**. 0.08. Social status. 0.23**. 0.08. Religion. 0.05. 0.09. Note. (1) The model in this table is a random intercept model. (2) The individual level N=38,511 and the country level N=26. *** p<0.001, ** P<0.01, *p<0.5..

(42) 37. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. In order to answer RQ2 about whether the impact of individual level variables may vary in different cultural contexts, I added a random slope to Model 3 to examine if variation exists among countries, which constitute Model 4 of this study. This model is exactly identical to Model 3 except that the slopes of environmental attitude, subjective norm, and self efficacy were made random. The result showed that the variance component, associated with the random slopes, is statistically significant (see Table3, p<0.01), which suggests that variation exists among countries. In other words, the level of individuals’ environmental attitudes, subjective norms, and self efficacy toward pro-environmental behavioral. 政 治 大. intentions all have different levels of effects in different countries. RQ2 is thus. 立. answered.. ‧ 國. 學. In addition, as explored by RQ3, this study is also interested in the moderating effects of these cultural orientations, therefore Model 5 (see Table 6, p<0.05) was. ‧. constructed. In Model 5, I added cultural orientation variables to each level-1. Nat. sit. y. variables in an attempt to predict level-1 variables’ random slopes. The results. n. al. er. io. indicated that the level of IDV moderated the effects of people’s environmental. i Un. v. attitudes (β =0.004, p<0.00) and subjective norms (β =-0.003, p<0.001).. Ch. engchi.

(43) 38. PREDICTING PEOPLE’S ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS. Table 6. Model 5: Predicting cultural values’ moderating effects on individuals’ environmental behaviors Fixed Effect (Variable slope) Intercept IDV MAS UAI Female Age Environmental attitude IDV MAS UAI Self efficacy IDV MAS UAI Subjective norm IDV MAS UAI Education Income Social status Religion. Standard error. 6.51*** -0.01** -0.01 -0.01 -0.01 -0.00*** 0.37*** 0.004*** 0.000 -0.001 0.10*** 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.11*** -0.003*** -0.000 -0.001 0.54*** 0.28*** 0.23** 0.07. 0.13 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.03 0.00 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.03 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.07 0.08 0.07 0.08. 政 治 大. 學. Nat. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. Coefficient. sit. n. al. er. io. Note. (1) The models in this table are random intercept and random slope models. (2) The individual level N=38,511 and the country level N=26. *** p<0.001, ** P<0.01, *p<0.5.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. FIGURE 2. A bivariate relationship of the effect of people’s environmental attitude and environmental behavioral intention.

數據

相關文件

7S 強化並且複習英國國定數學能力指標 level 4 的內容、主要學習 level 5 的內 容、先備一些 level 6 的延伸內容。. 8S 完成並且深化 level

“Time Discounting and Time Reference: A Critical Review.” Journal of Economic

In addition, to incorporate the prior knowledge into design process, we generalise the Q(Γ (k) ) criterion and propose a new criterion exploiting prior information about

• 人生在世的一個主要課題,便是了解事物間的 因果關係以及行為對周圍造成的影響,從而學

在二零一二至一三學年,共有 82,165 名來自 924 所學校的學生參加了戶 外教育營計劃,當中包括 31,365 名來自 387 所中學的學生及 50,800 名來 自

[r]

為青少年進行「全人教育」, 提供一個優良的學習 環境, 使青少年能發揮個人的潛能,

We examine how past experiences, perceived behavioral controls, subjective norms, attitudes, and economic pressures affect the behavioral intentions pertaining to