ABSTRACT

Tourism has increasingly become a preferred option for rural economic development. Like other economic opportunities, the purpose is to improve community viability and residents’ quality of life. However, the impacts from tourism are sometimes negative and may lead to a decreased quality of life for residents. This empirical study investigates residents’ quality of life using the core–periphery (CP) model. Periphery respondents reported a statistically higher overall quality of life, which is at odds with other research. Signifi cant differences in quality of life scores and subsequent indicators highlight the usefulness of the CP model towards understanding tourism impacts to a rural destination. Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: core–periphery model; quality of life; rural tourism development.

Received 17 June 2010; Revised 12 October 2010; Accepted 3 November 2010

INTRODUCTION

T

he stakes are high in tourism develop-ment — most recognizably for the fi nan-ciers, but also for the local residents. McCool and Martin (1994) stated that the purpose of tourism development, like other economic development strategies, should be to increase the quality of life for local residents. However, Rothman (1998) points out that although many communities may initially see tourism as an economic panacea, in some cases it alters the residents’ lives to the point that they report disillusionment and a lower quality of life. Residents’ quality of life and satisfaction with tourism is also important for tourism stakeholders. Resident dissatisfaction can become a liability for the local tourism industry, which relies on the host society’s hospitality and goodwill (Gursoy et al., 2002). Additionally, to ensure that residents’ dissatisfaction does not become an impediment to a destination’s attractiveness, it is in the interest of tourism stakeholders to identify and understand the host society’s attitudes towards tourism and how it affects residents’ quality of life.The connection between residents’ quality of life and tourism impacts is intuitive and has been addressed in the literature. d’Amore (1992) wrote that the Tourism Industry Asso-ciation of Canada addressed the issue in a 1992 annual meeting as members accepted a code of ethics and guidelines that were intended to ‘improve the quality of life within host Published online 26 November 2010 in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/jtr.823

Exploring Quality of Life Perceptions in

Rural Midwestern (USA) Communities:

an Application of the Core–Periphery

Concept in a Tourism

Development Context

Charles Chancellor*, Chia-Pin Simon Yu and Shu Tian Cole

Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Studies, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

*Correspondence to: Dr Charles Chancellor, Assistant Professor, Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Studies, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA.

communities’ among other issues (p. 65). This move came as a result of the 1987 book Our Common Future also called the Brundtland Report, which was the culmination report of the United Nations Commission on the Envi-ronment and Development. Empirical research has revealed that in some cases, residents indi-cated that attracting tourists leads to an increase in residents’ quality of life (Allen et al., 1993; Andereck and Jurowski, 2006). Carmichael (2006) indicated that residents’ quality of life and tourists’ quality of experiences may be infl uenced by dynamic factors (e.g. type and number of tourists, type and number of resi-dents, social exchange relations, social repre-sentations and type of tourism development). Lankford and Howard (1994) pointed out that several specifi c resident-related variables (e.g. length of residence, distance of tourism centre from the residents’ home, resident involve-ment in tourism decision-making) may infl u-ence the effect tourism has on residents.

In a regional development context, the core– periphery (CP) model posits that a core geo-graphic area attracts investment and subsequent development and is the driving force for plan-ning and decision-making. The periphery geo-graphic area receives less economic benefi t and may become depleted of resources such as labour and capital, which are diverted to support the core area. Tourism development could contribute to regional inequality with residents living in the core receiving the vast majority of economic gains and subsequent benefi ts associated with a higher standard of living (Murphy and Andressen, 1988). Con-versely in a tourism context, it is conceivable that residents living in peripheral locations may experience less negative effects since there are fewer tourists in the periphery.

Determining the spatial distribution of resi-dents’ quality of life, in a tourism development context, could be benefi cial to local tourism stakeholders, community leaders and offi cials. A more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between tourism development and residents’ quality of life would allow tourism planners to better mitigate regional issues and residents’ concerns associated with tourism development. The CP model provides a framework to systematically investigate the spatial aspect to residents’ quality of life.

This study contributes to building a stronger knowledge base of residents’ quality of life perceptions in a tourism development context, which has been lacking in the literature (Andereck et al., 2007). It also provides empiri-cal evidence to enhance the understanding of the CP concept at a local destination level, in this case rural Orange County, Indiana, USA. Much of the previous CP work has been con-ducted on a global, global region or national scale, and there is a dearth of literature focused on smaller geographic units such as a county.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND Tourism impacts and residents’ quality of life

Tourism development, like all economic devel-opment, comes coupled with a variety of impacts (positive and negative) on the destina-tion, usually articulated in the categories of economic, social-cultural and environmental effects. These impacts are often interrelated but are also discussed and studied individually. In essence, the study of impacts is focused on how a destination’s local economy, society, culture and natural environment benefi t, degenerate or are changed due to tourism. Ideally, tourism development provides eco-nomic prosperity, leading to a stronger and more stable society and greater environmental awareness, particularly if the natural environ-ment is part of the destination’s image or attraction. This ideal situation would also lead to an increased quality of life for the residents. However, negative impacts from tourism can lead to a lower quality of life, just as positive impacts can lead to a higher quality of life (Akis et al., 1996).

Quality of life is measured as both an objec-tive dimension that is external to the individ-ual and a subjective dimension that refl ects individual feelings and perceptions (Andereck and Jurowski, 2006). Researchers indicate that perceived impacts may affect residents’ quality of life more than actual impacts (Bricker et al., 2006). Community quality of life is comprised of residents’ subjective perceptions of a set of objective conditions (Cutter, 1985). Andereck and Jurowski (2006) pointed out that even a comprehensive set of objective measures does

not provide a complete picture without indi-viduals’ subjective evaluation of the condi-tions. The subjective dimension of quality of life provides necessary context since it is emotive, value-laden and encompasses factors such as life satisfaction and feelings of well-being (Davidson and Cotter, 1991; Grayson and Young, 1994; Diener and Suh, 1997; Dissart and Deller, 2000; cited in Andereck and Jurowski). Residents have a vested interest that any economic development tool, including tourism development, will improve their quality of life, even if they are not directly employed in the particular industry. Addition-ally, the tourism stakeholders have an interest since the local community plays an important role in a destination’s image and residents are often an integral part of the tourism experi-ence. Residents who support the tourism industry tend to be friendlier, providing a more positive experience for the tourists, which affect intentions to revisit and word-of-mouth recommendations. Numerous studies have examined the community factor as part of the overall tourism experience (Fick and Ritchie, 1991; LeBlanc, 1992; Mo et al., 1993; Perdue et al., 1999; Murphy et al., 2000). Several factors help ensure a successful tourism industry, such as the goodwill of local residents, residents’ support of tourism and the successful opera-tion of tourist-oriented businesses and organi-zations (Jurowski, 1994). These positive and negative effects may infl uence host residents’ perceived quality of life. If the negative effects outweigh the positive effects, the host’s dis-pleasure may eventually be openly displayed to tourists, which is harmful for the destina-tion’s image and ability to attract visitors (Fridgen, 1991). Gursoy et al. (2002) argued that ‘the success of any tourism project is threat-ened to the extent that the development is planned and constructed without the knowl-edge and support of the host population’ (p. 80). To this end, understanding factors that infl uence residents’ quality of life is essential in achieving the goal of favourable support for tourism development. Spatial distribution is one factor suspected to play a role in determin-ing the relationship between tourism develop-ment, tourism impacts, and resident attitudes and residents’ quality of life (Harrill and Potts, 2003; Raymond and Brown, 2007). The CP

model provides a conceptual framework to investigate the role that the spatial factor may play in determining residents’ quality of life.

Core–periphery concept

Tourism impact literature indicates that the spatial factor (the relationship between resi-dents’ home and the tourism development area) infl uences residents’ attitudes towards tourism development (Belisle and Hoy, 1980; Lankford and Howard, 1994; Korça, 1998; Jurowski and Gursoy, 2004). Earlier research revealed that residents living close to attrac-tions had favourable attitudes towards tourism (Belisle and Hoy, 1980; Pearce, 1980; Sheldon and Var, 1984; Mansfeld, 1992). However, more recent research indicates that residents living close to the core of tourism development may have more negative attitudes towards the effects of tourism (Harrill, 2004; Williams and Lawson, 2001; Harrill and Potts, 2003; Jurowski and Gursoy, 2004). Although perhaps contra-dictory, there are several studies investigating the spatial factor’s role in determining resi-dents’ attitudes towards tourism development. However, there are limited empirical investi-gations of spatial factors relation to residents’ quality of life.

The CP concept has been used to systemati-cally understand and develop economic systems geographically (Myrdal, 1957; Hirschmann, 1958; Friedmann, 1966; cited in Murphy and Andressen, 1988), while provid-ing context and explanation for power and development differences between cities, countries and hemispheres (Friedmann, 1966; Frank, 1969; Ibbery, 1984; cited in Weaver, 1998). Core areas are generally considered more urban and contain the majority of eco-nomic, political and social clout for a defi ned geographic region. Periphery areas are typi-cally rural and to some degree dependent upon the core while providing natural resources and labour to support the core (Hughes and Holland, 1994). The CP has been explored in a variety of geographic contexts from global (Krugman and Venables, 1995), to single country (Moore, 1984; Jordon, 2007), to single US state (Hughes and Holland, 1994), to a small region within a Canadian province (Murphy and Andressen, 1988).

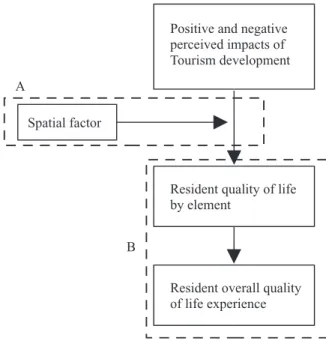

Positive and negative perceived impacts of Tourism development

Resident quality of life by element

Spatial factor

Resident overall quality of life experience A

B

Figure 1. Research framework. Delineating the core versus periphery has

traditionally been based on distance and loca-tion with an emphasis on the periphery’s isola-tion from the core (Prideaux, 2002, p. 308). However, Prideaux (2002) suggests that defi n-ing the periphery as simply distance from the core is now challenged due to transportation technology and its effect on people’s percep-tion of distance and time. Orange County’s tourism is primarily concentrated in two adjoining communities, and given Prideaux’s (2002) assertions, this study operationalized core versus periphery based on the presence (core) or absence (periphery) of tourism development.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

Although many studies investigate resident attitudes towards tourism development, there is a dearth of literature exploring tourism development and residents’ quality of life (Allen, 1990; Andereck et al., 2007). Addition-ally, authors suggest that the spatial factor moderates tourism’s impacts on residents’ quality of life; however, few studies have empirically addressed this issue (Harrill and Potts, 2003). The purpose of this study was to better understand the relationship between tourism development and residents’ quality of life, using the CP model as a conceptual framework. Specifi cally, this study sought to determine if residents’ quality of life varied depending upon if the respondent lived in the core or a periphery location. This study also sought to determine the quality of life variables that contribute to one’s overall measure of quality of life. Specifi cally, this study aims to: (i) examine resident quality of life elements that are affected by tourism development across core and periphery areas and (ii) test how the quality of life elements affect resident overall quality of life in core and periphery areas. Figure 1 illustrates this research framework. METHOD

Study community

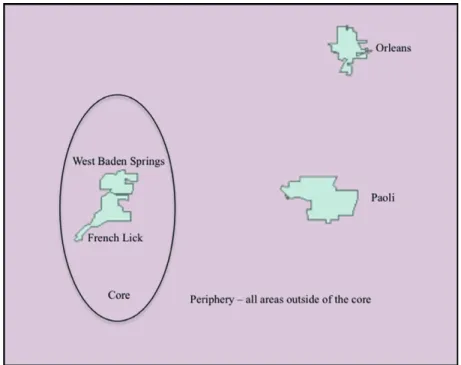

Located in South Central Indiana, Orange County is relatively easily accessible for resi-dents from many sizable Midwestern markets

(Figure 2). In recent history, basic manufactur-ing has been the primary industry (Orange County Economic Development Partnership, 2009). The average earning per job in Orange County for 2006 was 23.7% lower than the state average (STATS Indiana, 2009).

Tourism is re-emerging in this rural county and is expected to diversify and stimulate the local economy as it did early in the 20th century when Orange County was a prominent regional destination. Orange County’s traditional attractions were scenic, hilly topography and a resort built around a natural hot spring consid-ered to contain medicinal properties. Tourism began to decline signifi cantly in the 1940s and for many years played a much smaller role in the local economy. Once the Indiana state government approved a casino license for the county, tourism development began in earnest, and the original resort was refurbished into a four-star accommodation with adjoining casino, which opened in November 2006. Shortly afterwards, a fi ve-star accommodation opened, as did golf courses planned by a prominent course designer, an indoor/outdoor water park, several other smaller attractions, other new lodgings and upscale shopping venues. These new and refurbished attractions

Figure 2. Orange County, Indiana, USA.

joined the more modest offerings of lakes, a ski slope, shopping, museums and antiques.

As indicated in Table 1, recent tourism devel-opment has provided economic growth to Orange County. Tourism-related employment grew from 950 to 2044 individuals between 2006 and 2007, which coincided with the opening of upscale tourism attractions. Data from STATS Indiana (2008) indicated that Orange County’s average earning per job for accommodations and food service sector ranked #1 in the state.

Recent tourism development in Orange County has been focused in the adjacent towns of French Lick and West Baden Springs, which represented 12.9% of the county’s 2006 popula-tion (STATS Indiana, 2009). The upscale and midrange accommodations, waterpark, resort, casino, golf courses and shopping venues were

developed in French Lick and West Baden Springs, which determined the selection of these two towns as the core in this study. The periphery is compromised of all the surround-ing communities, which received very little or no recent tourism development. Figure 3 is a map of the rather rectangular Orange County with its four communities large enough to have local governments. Communities con-taining no local governments were not included but are dispersed throughout the county.

Data collection

Survey instruments were mailed to a random selection of 2000 households in Orange County, Indiana. The household addresses were pur-chased from a marketing fi rm. Using a modi-fi ed Dillman (2000) Tailored Design technique, Table 1. Annual statistics of employment, earnings and average earnings of accommodations and food sector in Orange County, Indiana.

2006 2007 2008

Employment 950 2044 2023

Annual earnings 22 231 000 59 620 000 61 498 000

Average earnings per job 23 401 29 168 30 399

Figure 3. Core and periphery areas of Orange County*.

*Only communities large enough to support a local government were included.

each respondent was contacted fi ve times (pre-notice postcard, letter/questionnaire, reminder postcard, replacement letter/questionnaire and reminder postcard). In addition to the quality of life questions, information was also gathered on residents’ demographics. ZIP code data were used to categorize respondents into either the core (French Lick, West Baden Springs) or periphery (all other locations).

Survey instrument

Quality of life was measured in subjective dimensions, which refl ected residents’ life sat-isfaction, happiness, feelings of well-being and beliefs about their standard of living. Accord-ing to Dissart and Deller (2000), subjective measures are critical to accurately evaluate community quality of life. Thus, the concept of subjective dimension was adopted in this study to measure residents’ quality of life. This study used a fi ve-point scale (1 = Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Fair, 4 = Good, 5 = Very Good) to measure resident perceptions on 12 quality of life items, including emergency services, museums and cultural centres, job opportuni-ties, educational system, cost of living, safety

from crime, conditions of roads and highways, infrastructure, traffi c congestion, parks and recreation areas, overall cleanliness and appearance, and overall community livability (Wilkin, 2006). Additionally, a subjective overall quality of life question was asked using the same fi ve-point scale.

Data management and analysis

Data were stored and analysed using the SPSS 16.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA) software package. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if differences existed between core and periphery respon-dents on each of the quality of life dimensions and the overall quality of life question. Regres-sion analysis was then used to determine which dimensions contributed to the quality of life for respondents in each group.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

There were 649 usable survey instruments returned, for a response rate of 32.5%. Among the respondents, 55.8% were male, and 23.8%

were between 56 and 65 years. Additionally, 50% were employed full time and 32.2% reported a household income between $20 000 and $39 000 annually.

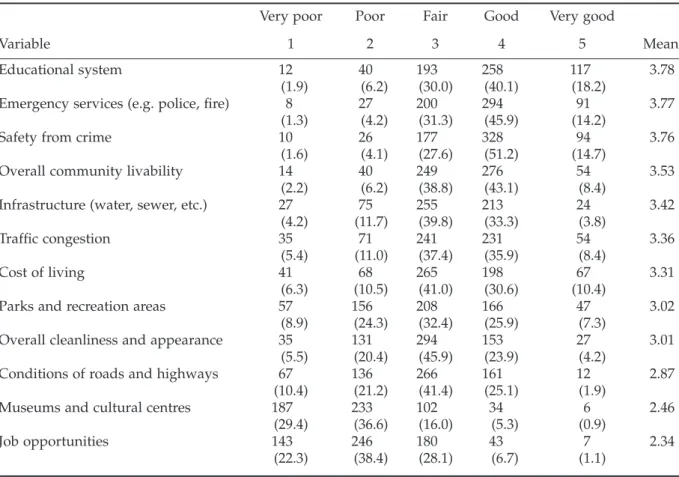

The overall quality of life mean for all respondents was 3.71, very near the equivalent of ‘good’. The results of respondents’ ratings of quality of life elements are illustrated in Table 2. The lowest rated elements, job opportu-nities, museums and cultural centres, and the con-ditions of roads and highways, were considered ‘poor to fair’. The highest rated elements approached a ‘good’ rating and included the educational system, emergency services and safety from crime.

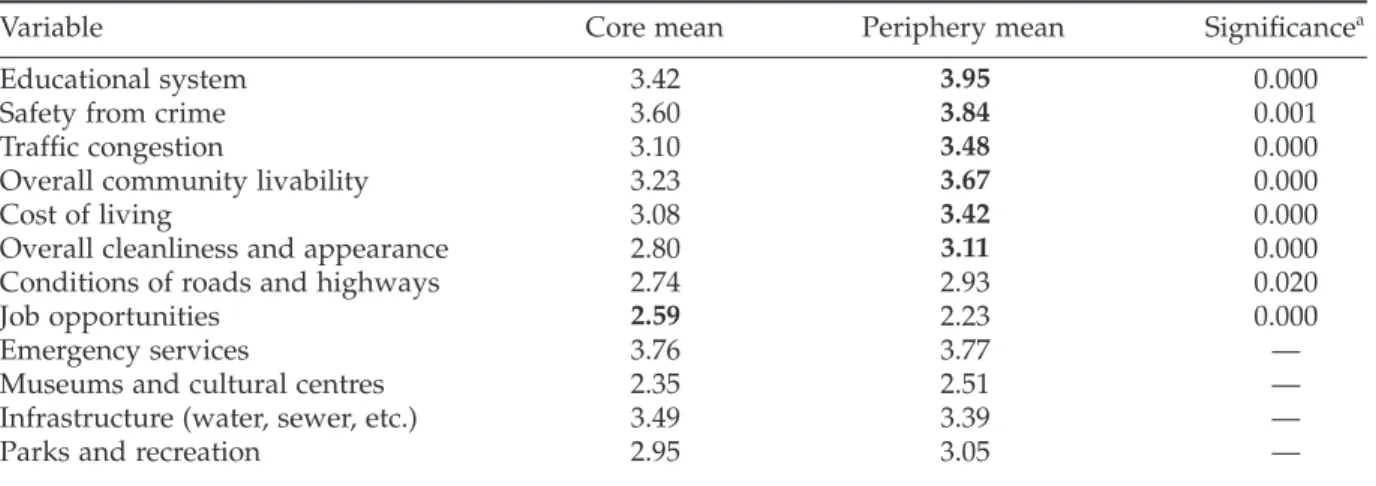

The periphery group reported a statistically signifi cant (p < 0.05) higher overall quality of life score (3.78) than the core group (3.56), which supports the idea that those living in the core might be experiencing negative impacts

from tourism. Further analysis using a t-test found several signifi cant differences (p < 0.05) between the core and periphery groups as illustrated in Table 3. The core group reported lower quality of life scores on seven of the eight signifi cant variables. Specifi cally, the core group reported lower quality of life scores on the variables safety from crime, traffi c congestion, overall community livability, cost of living, overall cleanliness and appearance. These are common issues associated with negative effects of tourism, which may indicate the core group’s quality of life was being negatively affected by tourism. For example and increase in crime, traffi c congestion, cost of living and litter are all possible negative impacts of tourism devel-opment (Akis et al., 1996).

Job opportunities was the only signifi cant (p < 0.05) variable rated higher by the core group. This is not surprising since tourism

Table 2. Rating of the current condition of each of the following quality of life elements in Orange County.

Variable

Very poor Poor Fair Good Very good

Mean

1 2 3 4 5

Educational system 12 40 193 258 117 3.78

(1.9) (6.2) (30.0) (40.1) (18.2)

Emergency services (e.g. police, fi re) 8 27 200 294 91 3.77

(1.3) (4.2) (31.3) (45.9) (14.2)

Safety from crime 10 26 177 328 94 3.76

(1.6) (4.1) (27.6) (51.2) (14.7)

Overall community livability 14 40 249 276 54 3.53

(2.2) (6.2) (38.8) (43.1) (8.4)

Infrastructure (water, sewer, etc.) 27 75 255 213 24 3.42

(4.2) (11.7) (39.8) (33.3) (3.8)

Traffi c congestion 35 71 241 231 54 3.36

(5.4) (11.0) (37.4) (35.9) (8.4)

Cost of living 41 68 265 198 67 3.31

(6.3) (10.5) (41.0) (30.6) (10.4)

Parks and recreation areas 57 156 208 166 47 3.02

(8.9) (24.3) (32.4) (25.9) (7.3)

Overall cleanliness and appearance 35 131 294 153 27 3.01

(5.5) (20.4) (45.9) (23.9) (4.2)

Conditions of roads and highways 67 136 266 161 12 2.87

(10.4) (21.2) (41.4) (25.1) (1.9)

Museums and cultural centres 187 233 102 34 6 2.46

(29.4) (36.6) (16.0) (5.3) (0.9)

Job opportunities 143 246 180 43 7 2.34

(22.3) (38.4) (28.1) (6.7) (1.1)

Table 3. Means of the 12 quality of life elements in core–periphery model.

Variable Core mean Periphery mean Signifi cancea

Educational system 3.42 3.95 0.000

Safety from crime 3.60 3.84 0.001

Traffi c congestion 3.10 3.48 0.000

Overall community livability 3.23 3.67 0.000

Cost of living 3.08 3.42 0.000

Overall cleanliness and appearance 2.80 3.11 0.000

Conditions of roads and highways 2.74 2.93 0.020

Job opportunities 2.59 2.23 0.000

Emergency services 3.76 3.77 —

Museums and cultural centres 2.35 2.51 —

Infrastructure (water, sewer, etc.) 3.49 3.39 —

Parks and recreation 2.95 3.05 —

For signifi cant items, the bold values represent higher means.

a Only signifi cant items have p-value listed.

development increases job opportunities; however, this data indicates that job opportu-nities might be the only positive result of tourism development for core respondents.

In order to better understand the relation-ship between the 12 quality of life items and the overall quality of life score, regression anal-ysis was conducted for all residents and then separately for the core and periphery groups. For all residents, analysis revealed an R2 of

0.376 with the signifi cant contributing vari-ables being emergency services, job opportunities, cost of living, overall community livability, educa-tional system and parks and recreation (Table 4). Respondents living in the core indicated that emergency services, job opportunities, cost of living, overall community livability and infrastructure elements were signifi cant contributors to their overall quality of life with an R2 of 0.384.

Respondents living in the periphery indicated that emergency services, job opportunities, cost of living, educational system and infrastructure made signifi cant contributions to their overall quality of life with an R2 of 0.412. All signifi cant

stan-dardized coeffi cients were positive except for the variable infrastructure in the core group.

Only the four variables of emergency services, job opportunities, cost of living and infrastructure were signifi cant (p < 0.05) to both the core and periphery respondents. Job opportunities and cost of living are basic concerns, and their sig-nifi cance might stem from the fact that Orange County has been economically depressed for

several years. Therefore, it is intuitive that job opportunities and cost of living would be important predictors of quality of life in this area. Emergency services and infrastructure (water and sewer) are also basic needs. Residents of more affl uent and developed areas may take these issues for granted. Additionally, these variables have fewer substitutes, which could make them more signifi cant predictors.

The variables parks and recreation services and museums and cultural centres did not signifi cantly affect quality of life. The lack of signifi -cance could be due to the fact that rural Orange County does not have an abundance of recre-ation services, museums and cultural centres. Alternatively, perhaps the benefi ts derived from these variables are being met through other mediums, which could be an indication that these variables have more substitutes in the area.

The variable educational system is interesting in that it only signifi cantly contributed to the overall quality of life within the periphery group and was the most highly rated quality of life variable (3.95) by the periphery group. Infra-structure is signifi cant in the core and periph-ery but not once combined in the all group due to differences in how each group rated infra-structure. In the core group, the standardized coeffi cient for infrastructure was negative (−0.228), indicating that an increase in infra-structure negatively affected the respondents’ evaluation of quality of life. For context,

signifi cant road, water and sewer construction took place in the core areas before and during data collection, which might have skewed the data and points to the necessity of conducting longitudinal studies to account for the dynamic nature of tourism development. Conversely, the periphery group had a positive standard-ized coeffi cient (0.097) indicating that an increase in infrastructure positively affected the respondents’ evaluation of qualify of life. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH Tourism is a re-emerging industry in Orange County, and tourism offi cials have taken action to ensure that the entire county will benefi t economically, based on the idea that economic benefi ts will lead to a higher quality of life. However, this study indicates that there are factors other than economics to consider. To this end, understanding tourism’s role from the residents’ perspective can aid tourism offi -cials in policy and decision-making.

Further-more, the CP approach provides a systematic method of detecting and understanding the diversity of residents’ perceptions of their quality of life.

This project contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence associating quality of life factors to the CP model. The idea that residents’ quality of life may be affected, whether or not the resident lives in an area of tourism development, was supported by this study. The periphery group reported a statisti-cally signifi cant higher overall quality of life score than the core group. The core group reported lower scores on seven individual quality of life variables, and those variables are common indicators of negative tourism impacts. The one variable, job opportunities, which core respondents rated signifi cantly higher than periphery respondents is a common indicator of a positive economic impact of tourism. Therefore, these fi ndings indicate that tourism development may be contributing to the difference in quality of life scores for the Table 4. Elements affecting the overall quality of life measurement using regression analysis.

Independent variables

Respondents

All Core Periphery

p-values

Standardized

coeffi cients p-values

Standardized

coeffi cients p-values

Standardized coeffi cients Emergency services 0.002* 0.12 0.019* 0.158 0.035* 0.101 Job opportunities 0.000* 0.151 0.003* 0.206 0.001* 0.156 Cost of living 0.000* 0.211 0.001* 0.245 0.000* 0.190 Overall community Livability 0.001* 0.156 0.001* 0.297 0.057 0.105 Educational system 0.002* 0.118 0.280 0.077 0.001* 0.147

Parks and recreation 0.016* 0.096 0.099 0.114 0.062 0.092

Infrastructure (water, sewer, etc.) 0.858 0.007 0.001* −0.228 0.036* 0.097 Museums and cultural Centers 0.307 −0.038 0.341 −0.064 0.604 −0.024

Safety from crime 0.253 0.047 0.845 −0.015 0.100 0.08

Conditions of roads and highways 0.305 0.042 0.307 0.074 0.574 0.027 Traffi c congestion 0.756 0.012 0.907 0.008 0.652 0.02 Overall cleanliness and appearance 0.356 0.041 0.887 0.011 0.708 0.021 R2 0.376 0.384 0.412 * p < 0.05.

Orange County respondents, and that the CP context (presence or absence of tourism devel-opment) might help explain these differences. This study does not necessarily suggest that tourism development lowers residents’ quality of life; rather the fi ndings provide another avenue to consider when investigating the spatial distribution of tourism development impacts. Focus group inquiry techniques would be benefi cial to provide a deeper under-standing of these relationships.

This study also contributes to the identifi ca-tion of variables that contribute to the overall quality of life measurement, and provides rationale and context for those contributions. This study operationalized core and periphery as simply the presence or absence of tourism development, in order to try and account for the complexities of the term ‘distance’, which previous studies have encountered (Prideaux, 2002).

This study was conducted as the fi rst phase of the upscale tourism development projects were opened, capturing resident perceptions of quality of life before the anticipated large numbers of tourists arrived. Locally, this study provides baseline data, which could be useful for future comparisons in a longitudinal study. Future iterations of this study would allow tourism offi cials and researchers to better understand and monitor the patterns of tourism impacts within the CP context. Geo-graphical information system technology could be a useful tool for monitoring the dynamic changes of tourism impacts on resi-dents’ quality of life.

LIMITATIONS

This study has used the CP model to illustrate differences in residents’ perceptions of quality of life elements. Although this project has answered some questions, it has also raised others that are ripe for exploration. These fi nd-ings support conceptual underpinnnd-ings of the CP relationship regarding quality of life; however, more research is needed to better explain the relationship and further quantify the tourism impacts that affect quality of life.

Additionally, understanding the importance of each factor to each respondent would aid in a better application of the results. Perhaps a

factor may be rated poorly because the particu-lar factor is just not important to the resident, or maybe the factor is not an option in that location. For example, most of the periphery locations in this study are very rural and do not offer some of the quality of life variables, e.g. parks and recreation departments, and museums and cultural centres. Lastly, this study was conducted in a very rural area of a developed nation and the fi ndings may be gen-eralizable to similar areas domestically and internationally. However, the fi ndings may be less generalizable to urban areas.

REFERENCES

Akis S, Peristianis N, Warner J. 1996. Residents’ atti-tudes to tourism development: the case of Cyprus.

Tourism Management 17(7): 481–494.

Allen LR. 1990. Benefi ts of leisure attributes to com-munity satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research 22: 183–196.

Allen LR, Hafer HR, Long PT, Perdue RR. 1993. Rural residents’ attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research

31(4): 27–33.

Andereck KL, Jurowski C. 2006. Tourism and quality of life. In Quality Tourism Experiences, Jennings G, Nickerson NP (eds). Elsevier: Oxford; 136–154. Andereck KL, Valentine KM, Vogt CA, Knopf RC.

2007. A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. Journal of Sustainable

Tourism 15(5): 483–502.

Belisle FJ, Hoy DR. 1980. The perceived impact of tourism by residents: a case study in Santa Marta, Columbia. Annals of Tourism Research 7(1), 83–101. Bricker KS, Daniels MJ, Carmichael BA. 2006.

Quality tourism development and planning. In

Quality Tourism Experiences, Jennings G,

Nicker-son NP (eds). Elsevier: Oxford; 171–191.

Carmichael BA. 2006. Linking quality tourism expe-riences, residents’ quality of life, and quality experiences for tourists. In Quality Tourism

Experi-ences, Jennings G, Nickerson NP (eds). Elsevier:

Oxford; 115–135.

Cutter SL. 1985. Rating Places: A Geographer’s View

on Quality of Life. Association of American

Geo-graphers Resource Publications: Washington, DC. d’Amore LJ. 1992. A code of ethics and guidelines

for socially and environmentally responsible tourism. Journal of Travel Research 31(3): 64–66. Davidson WB, Cotter PR. 1991. The relationship

between sense of community and subjective well-being: a fi rst look. Journal of Community Psychology

Diener E, Suh E. 1997. Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social

Indicators Research 40: 189–216.

Dillman D. 2000. Mail and Internet Services: The

Tai-lored Design Method. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken,

NJ.

Dissart JC, Deller SC. 2000. Quality of life in the planning literature. Journal of Planning Literature

15(1): 135–161.

Fick GR, Ritchie JRB. 1991. Measuring service quality in the travel and tourism industry. Journal

of Travel Research 30: 2–9.

Frank A. 1969. Capitalism and underdevelopment in

Latin America. Monthly Review Press: New York.

Fridgen JD. 1991. Dimensions of Tourism. The Educa-tional Institute of the American Hotel and Motel Association: East Lansing, MI.

Friedmann JP. 1966. Regional Development Policy: A

Case Study of Venezuela. MIT Press: Boston.

Grayson L, Young K. 1994. Quality of Life in Cities:

An Overview and Guide to the Literature. The British

Library: London.

Gursoy DJ, Jurowski C, Uysal M. 2002. Resident attitudes: a structural modeling approach. Annals

of Tourism Research 29(1): 79–105.

Hirschmann AO. 1958. The Strategy of Economic

Development. Yale University Press: Boston.

Harrill R. 2004. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: a literature review with implica-tions for tourism planning. Journal of Travel

Research 18(3): 251–266.

Harrill R, Potts TD. 2003. Tourism planning in his-toric districts: attitudes toward tourism develop-ment in Charleston. Journal of the American

Plan-ning Association 69(3): 233–244.

Hughes DW, Holland DW. 1994. Core-periphery economic linkage: a measure of spread and pos-sible backwash effects for the Washington economy. Land Economics 70(3): 364–377.

Ibbery B. 1984. Core-periphery contrasts in Euro-pean social well-being. Geography 69: 289–302. Jordon L-A. 2007. Interorganisational relationships

in small twin-island developing states in the Caribbean — the role of the internal core-periph-ery model: the case of Trinidad and Tobago.

Current Issues in Tourism 10(1): 1–32.

Jurowski C. 1994. The interplay of elements affect-ing host community resident attitudes toward tourism: a path analytic approach. Doctoral dis-sertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Jurowski C, Gursoy D. 2004. Distance effects on resi-dents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism

Research 31(2): 296–312.

Korça P. 1998. Resident perceptions of tourism in a resort town. Leisure Sciences 20(3): 193–212.

Krugman P, Venables AJ. 1995. Globalization and the inequity of nations. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics 110(4): 857–880.

Lankford S, Howard D. 1994. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research

21(1): 121–139.

LeBlanc G. 1992. Factors affecting customer evalua-tions of service quality in travel agencies: an investigation of customer perspectives. Journal of

Travel Research 30: 10–16.

Mansfeld Y. 1992. Group-differentiated perceptions of social impacts related to tourism development.

Professional Geographer 44: 377–392.

McCool SF, Martin SR. 1994. Community attach-ment and attitudes toward tourism developattach-ment.

Journal of Travel Research 32(3): 29–34.

Mo C, Howard DR, Havitz ME. 1993. Testing an international tourist role typology. Annals of

Tourism Research 20(2): 319–335.

Moore, M. (1984). Categorising space: urban-rural or core-periphery in Sri Lanka. The Journal of

Development Studies 20(3): 102–122.

Murphy PE, Andressen B. 1988. Tourism develop-ment on Vancouver Island: an assessdevelop-ment for the core-periphery model. The Professional Geographer

40(1): 32–42.

Murphy P, Pritchard MP, Smith B. 2000. The desti-nation product and its impact on traveler percep-tions. Tourism Management 21: 43–52.

Myrdal G. 1957. Economic Development Theory and

Underdeveloped Regions. Duckworth: London.

Orange County Economic Development Part-nership (2009). Industry Sectors. Available at http://www.ocedp.com/sectors.php (accessed 18 November 2010).

Pearce J. 1980. Host community acceptance of foreign tourists: strategic considerations. Annals

of Tourism Research 7(2): 224–233.

Perdue RR, Long PT, Kang YS. 1999. Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: the marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of

Business Research 44: 165–177.

Prideaux B. 2002. Building visitor attractions in periphery areas: can uniqueness overcome isola-tion to produce viability? Internaisola-tional Journal of

Tourism Research 4: 379–389.

Raymond C, Brown G. 2007. A spatial method for assessing resident and visitor attitudes towards tourism growth and development. Journal of

Sus-tainable Tourism 15(5): 520–540.

Rothman HK. 1998. Devil’s Bargain: Tourism in the

Twentieth-century American West. University of

Kansas Press: Lawrence.

Sheldon P, Var T. 1984. Resident attitudes to tourism in North Wales. Tourism Management 5(1): 40–47.

STATS Indiana. 2008. STATS Indiana Profi le. Orange County, Indiana 2008 Depth Profi le. Indiana Busi-ness Research Center: Bloomington, IN.

STATS Indiana. 2009. STATS Indiana Profi le. Avail-able at http://www.stats.indiana.edu/profi les/ custom_profi le_frame.html (accessed 10 March 2009).

Weaver DB. 1998. Peripheries of periphery: tourism in Tobago and Barbuda. Annals of Tourism Research

25(2): 292–313.

Wilkin J. 2006. Tourism Development in

Butte-Silver Bow: Visitor Profi les and Resident Attitudes

(University of Montana Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Report 2006-2). Avail-able at http://www.itrr.umt.edu/research06/ ButteCTAP06.pdf (accessed 4 January 2009). Williams J, Lawson R. 2001 Community issues and

resident opinions of tourism. Annals of Tourism