Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 298-308

The Effects of Attitude, Subjective Norm, and

Perceived Behavioral Control on Consumers’

Purchase Intentions: The Moderating Effects

of Product Knowledge and Attention to

Social Comparison Information

JYH-SHEN CHIOU

Associate Professor Dept. Of International Trade National Chengchi University

(Received July 20, 1998; Accepted September 3, 1998) ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research is to investigate whether the relative influences of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control on consumers’ purchase intentions will be different when consumers possess different levels of product knowledge (subjective and objective) and attention to social comparison information (ATSCI). As proposed by the theory of planned behavior, consumers’ purchase intentions are affected not only by their attitudes, but also by their group’s influences and their own perceived control. The relative strength of effects of these three factors on consumers’ purchase intentions is expected to vary across behaviors and situations.

The results showed that the relative importance of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the prediction of intention varies when consumers possess different levels of subjective product knowledge and ATSCI. Subjective knowledge is a moderating variable for the relationship between perceived behavioral control and purchase intention, while ATSCI was a moderating variable for the relationship between attitude and purchase intentions, and for the relationship between subjective norm and purchase intention.

This research has strong implications for marketers. It can help them develop more effective marketing programs to affect consumers’ purchase intentions. In addition, the study is one of a few studies that applies the theory of planned behavior in the marketing field.

Key Words: Theory of Planned Behavior, Product Knowledge, Group Influences, Perceived Behavior Control

I. Introduction

The theory of reasoned action (Fishbein, 1967; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) is one of the most influential models in predicting human behavior and behavioral dispositions. The theory proposed that behavior is affected by behavioral intentions which, in turn, are affected by attitudes toward the act and by subjective norm. The first component, attitude toward the act, is a function of the perceived consequences people associate with the behavior. The second component, subjective norm, is a function of beliefs about the expectations of important ref-erent others, and his/her motivation of complying with these referents. The model received a lot of support in

empiri-cal studies of consumer behavior and social psychology related literature (Ryan, 1982; Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988). It, however, has limitations in predict-ing behavioral intentions and behavior when consumers do not have volitional control over their behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995). The theory of planned be-havior was proposed to remedy these limitations (Ajzen, 1985, 1991). It includes another source that will have in-fluence on behavioral intentions and behavior, perceived behavioral control, in the model.

The theory of planned behavior proposes that per-ceived behavioral control of the focal person in a decision making situation may affect his/her behavioral intentions. Perceived behavioral control is more important in

influ-encing a person’s behavioral intention particularly when the behavior is not wholly under volitional control. For example, when purchasing an innovative product, consum-ers may need not only more resources (time, information, etc.), but also more self-confidence in making a proper decision. Therefore, perceived behavioral control becomes a salient factor in predicting a person’s behavioral inten-tion under this purchasing situainten-tion.

The purpose of this research is to investigate whether the influences of attitude, social norm, and personal con-trol on consumers’ purchase intentions will be different when consumers possess different levels of product knowl-edge (subjective and objective) and different degrees of attention to social comparison information (ATSCI). As described by Ajzen (1991), the relative importance of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral con-trol in the prediction of intention is expected to vary across behaviors and situations. Examining the moderating ef-fects of product knowledge and ATSCI in the planned be-havior model can enhance the knowledge of this research paradigm.

This research has strong implications for marketers. It can help them develop more effective marketing pro-grams to affect consumers’ purchase intentions under dif-ferent situations. In addition, the study is one of a few studies which applies the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1991) in the marketing field.

II. Literature Review

The theory of planned behavior is an extension of the theory of reasoned action made necessary by the original model’s limitations in dealing with behaviors over which people have incomplete volitional control (Ajzen, 1991). As discussed by Liska (1984) and other researchers (Sheppard et al., 1988), the theory of reasoned action can-not deal with behaviors that require resources, cooperation, and skills. In response to the criticism about the model, Ajzen (1985) proposed an adjusted model called “theory of planned behavior.” The extent to which one’s inten-tions to perform behaviors can be carried out depends in part on the amount of resources and control one has over the behavior. That is, the resources and opportunities avail-able to a person must, to some extent, dictate the likeli-hood of behavior achievement.

Perceived behavioral control reflects beliefs regard-ing the access to resources and opportunities needed to perform a behavior. It may encompass two components (Ajzen, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995). The first compo-nent reflects the availability of resources needed to en-gage in the behavior. This may include access to money, time, and other resources. The second component reflects

the focal person’s self-confidence in the ability to conduct the behavior.

The concept of perceived behavioral control is most compatible with Bandura’s (1977, 1982) concept of per-ceived self-efficacy which is concerned with judgement of how well one can execute required actions to deal with specific situations. People’s behaviors are strongly influ-enced by their confidence in their ability to perform them. The theory of planned behavior places the construct of self-efficacy within a more general framework of the rela-tions among attitude, subjective norm, and behavioral intention.

The theory of planned behavior has received broad support in empirical studies of consumption and social psychology related literature (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Driver, 1992; Ajzen & Madden, 1986; Taylor & Todd, 1995).

1. The Moderating Role of Product Knowledge

The level of a consumer’s product knowledge may affect his/her information and decision-making behavior (Brucks, 1985; Park, Mothersbaugh, & Feick, 1994). Two knowledge constructs have been distinguished (Brucks, 1985; Park et al., 1994). The first one is objective knowledge: accurate information about the product class stored in the long term memory. The second one is subjective knowledge: people’s perceptions of what or how much they know about a product class.

Although subjective and objective knowledge are related, they are distinct in two aspects (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Brucks, 1985). First, when people do not accurately perceive how much or how little they actually know, sub-jective knowledge may over or under estimate one’s ac-tual product knowledge. Second, measures of subjective knowledge can indicate self-confidence levels as well as knowledge levels. That is, subjective knowledge can be thought of as including an individual’s degree of confi-dence in his/her knowledge, while objective knowledge only refer to what an individual actually knows.

As discussed in the previous section, one component of perceived behavioral control in the theory of planned behavior reflects a person’s self-confidence in the ability to conduct the behavior. If a person has strong subjective product knowledge, s/he will have higher confidence in the ability to carry on the consumption behavior. His/her attitude toward the act already shows this confidence. The attitude toward the behavior can overshadow the effect of perceived behavioral control. Therefore, the effect of per-ceived behavioral control on behavioral intention will be weaker when consumers have high subjective product knowledge.

On the other hand, if a person has lower subjective product knowledge, s/he will have less confidence in the ability to carry out the consumption behavior. When form-ing behavioral intention, attitude toward the act will not be the dominating antecedent. Perceived behavioral control, on the other hand, will become an important fac-tor of consideration. Therefore, subjective, instead of objective knowledge, may moderate the relationship be-tween perceived behavior control and behavioral intention. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H1a: The effect of attitude on behavioral intention will be stronger when the consumers have a high level of subjective product knowledge than when consumers have a low level of subjective product knowledge H1b: Subjective product knowledge does not moder-ate the relationship between subjective norm and be-havioral intention

H1c: The effect of perceived behavioral control on behavioral intention will be stronger when the con-sumers have a low level of subjective product knowl-edge than when consumers have a high level of sub-jective product knowledge

H2: Objective product knowledge does not moderate the relationship between the three antecedents (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) and behavioral intention

2. The Moderating Role of Attention to Social Comparison Information

People with different types of self concepts may have different types of experiences, cognition, emotions, and motivations (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). For example, people classified as independent believe that they are sepa-rated from the social context. They want to be unique and be able to express themselves. On the other hand, people classified as interdependent think that they are connected to the social context. They want to belong to a group and promote others’ goals. They consider that relationships with others in specific contexts define the self. Therefore, they use others for social comparison and reflected appraisal. Personality factors can be the central reason for affecting the relationship between attitude and behav-ioral intention. Several studies in the attitude function school have demonstrated that personality variation can create significantly different requirements of attitude func-tions (Bearden & Rose, 1990; DeBono, 1987; DeBono & Packer, 1991; Snyder & DeBono, 1985). For example, Snyder

and DeBono (1985) used personality assessment to operationalize attitude functions. They argued that high self-monitoring individuals, who strive to fit into various social situations, should tend to form attitudes that serve the social adjustment function. In contrast, low self-moni-toring individuals, who strive to remain true to their inner values and attributes, will tend to form attitudes that serve the value expressive function. To investigate these hypotheses, they created ads in pictures and words that represented either image oriented or quality oriented mes-sages to consumers. The results showed that high self-monitoring consumers thought the image oriented ad was better, more appealing, and more effective. By contrast, low self-monitoring consumers preferred the quality ori-ented ads. Similarly, in a persuasion study regarding deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill, DeBono (1987) demonstrated that high self-monitoring subjects expressed attitudes that were more opposed to deinstitutionalization when they heard the social adjustment messages opposing deinstitutionalization than when they heard the attribute evaluative messages. On the other hand, low self-moni-toring subjects displayed significantly negative attitudes toward deinstitutionalization after hearing the attribute evaluative message.

DeBono and Packer (1991) also found that high self-monitoring subjects rated the quality of a product higher than low self-monitoring subjects did after watching im-age-oriented ads, while low self-monitoring subjects rated the quality of a product higher than high self-monitoring subjects did after watching quality-oriented ads. Using a different methodological approach, DeBono and Edmonds (1989) showed that the basic theory about personality in-fluences still holds. They induced high and low self-moni-toring subjects to write counterattitudinal essays. One group of subjects was led to believe that their positions was opposed to the majority, while the other group of sub-jects was led to believe that their position was contrary to their personal values. The results showed that high self-monitoring subjects modified their attitudes in the direc-tion of their essays more in the social adjustive situadirec-tion than in the value expressive situation. On the other hand, low self-monitoring subjects modified their attitudes in the direction of their essays more in the value expressive situ-ation than in the social adjustive situsitu-ation.

Although Snyder’s self-monitoring scale achieved several empirical justifications, this scale was criticized for lacking reliability and multidimensionality. The At-tention-To-Social-Comparison-Information (ATSCI) scale is a result of these critiques (Lennox & Wolfe, 1984). ATSCI was demonstrated to be internally consistent, valid, and capable of mediating the relative effects of interper-sonal consideration (Bearden & Rose, 1990; Lennox &

Wolfe, 1984).

Using the Attention-To-Social-Comparison-Informa-tion (ATSCI) scale, Bearden and Rose (1990) found that persons scoring high in ATSCI were more aware of oth-ers’ reactions to their behavior and were more concerned about the nature of those reactions than persons scoring low in ATSCI. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H3a: The effect of attitude on behavioral intention will be stronger when the consumers have low ATSCI than when consumers have high ATSCI

H3b: The effect of subjective norm on behavioral in-tention will be stronger when the consumers have high ATSCI than when consumers have low ATSCI H3c: ATSCI does not moderate the relationship be-tween perceived behavioral control and behavioral in-tention

III. Methodology

1. Experimental Stimuli A. Product type

A laser printer was chosen as the object for this research. In a pre-test, it was found that computer printer can generate a significant amount of statements regarding perceived behavioral control and subjective norm when subjects were asked about their criteria for purchasing a computer printer.

B. Product concept

A product concept for the printer was developed. The concept gives not only the reader the benefit of the product, but also the reason why. The printer employs a new tech-nology called “Neo-Laser Techtech-nology.” The performance of the printer was claimed to be comparable to those of a normal laser printer but at a more reasonable price.

C. Subjects

300 student subjects from universities around north-ern Taiwan were recruited for the study. The subjects were junior or senior college students and majored in business (or other social science related majors). Seven universi-ties (three of them are public universiuniversi-ties and others are private universities) in the northern part of Taiwan were included in the sampling frame. Student subjects were used in this study because the experiment object,

com-puter printer, is a relevant product for college students and college students are important targets for computer printer marketers.

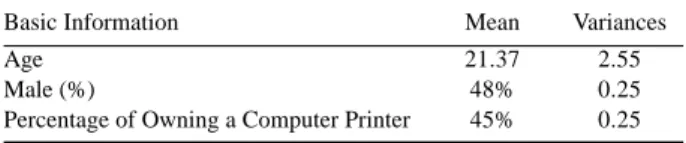

Basic information of the subjects is presented in Table 1. The average age of respondents are around 21.37 years old. Forty-eight percent of the subjects are male. Forty five percent of the subjects own a computer printer.

D. Questionnaire

The Chinese questionnaire was developed by apply-ing Brislin’s (1980) recommendation to minimize the prob-lem of lack of equivalence between the Chinese and En-glish version. The EnEn-glish version of the questionnaire was translated into Chinese and back translated into En-glish to check the translation’s accuracy. Different trans-lators were used in these two stages. When a major incon-sistency occurred in the translation, a discussion between two translators was conducted to reconcile the differences. The precise wording of the questionnaire is decentered away from the original language version and adjusted so that it is smooth and natural sounding, as well as equivalent, in both language.

E. Procedures

The research was conducted in the students’ regular class sections. To increase subjects’ involvement in the study, all subjects were informed that the product or ser-vice would be available in the area in the near future. Af-ter the subjects reviewed the product concept, they were asked about their overall reactions, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and purchase intention.

F. Measures

Attitudes toward the product concept were measured by 7-point semantic differential scales reflecting overall favorable/unfavorable, bad/good, foolish/wise, and harm-ful/beneficial. The four scales were drawn from Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann’s (1983) and Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum’s (1957) attitude measurement scales. Pur-chase intentions were measured by asking whether the sub-ject would actually purchase the product when it is avail-able in the market on three 7-point semantic differential

Table 1. Basic Characteristics of the Sampled Subjects

Basic Information Mean Variances

Age 21.37 2.55

Male (%) 48% 0.25

scales, unlikely/likely, uncertain/certain, and impossible/ possible (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

The measurement of subjective norm and perceived behavioral control were based on scales developed by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), Ajzen (1985, 1991), and Tay-lor and Todd (1995). Subjective norm was measured by asking “Most people who are important to me would prob-ably consider my purchasing this computer printer to be ____.” Respondents were required to answer on 7-point semantic differential scales reflecting foolish/wise, use-less/useful, and worthless/valuable. Respondents were also required to answer the question stated as “Most people who are important to me would probably think I ____ buy this computer printer” on a 7-point differential scale re-flecting definitely should/definitely should not. Perceived behavioral control was measured by asking the following questions, (1) how much control do you have, (2) for me to buy this computer printer is ____, (3) if I want I could easily buy this computer printer, (4) it is mostly up to me whether or not I will buy this computer printer. The re-spondents were asked to answer the above questions on 7-point semantic scales.

The Attention-To-Social-Comparison-Information (ATSCI) scale developed by Lennox and Wolfe (1984) were administrated to each subject. The ATSCI scale is a revision of Snyder’s self-monitoring scale (Appendix A). It was demonstrated to be internally consistent, valid, and capable of mediating the relative effects of interpersonal consideration (Bearden & Rose, 1990).

Subjective product knowledge was measured by asking: (1) compared to average persons, rate your knowl-edge of how much you know about a computer printer; (2) compared to average persons, rate your knowledge of how much you know about different brands of computer printer; (3) compared to average persons, rate your knowledge of how much you know how to buy a computer printer; and (4) please indicate how much information you have searched about computer printers. The subjects were re-quired to answer questions on 7-point semantic scales.

There are two steps in developing objective knowl-edge scales. First, ten true/false questions were developed by consulting computer printer experts. Second, the ten questions were administrated to one expert subject group (i.e., employees from computer printer related industry) and one novice subject group (i.e., college students). The mean scores were calculated to see whether the questions can distinguish expert subjects from novice subjects. The results showed that eight out of the ten questions have strong and significant discriminatory power in separating expert and novice subjects. Therefore, only eight ques-tions were administrated in the final questionnaire. These questions are attached in the Appendix B.

2. Data Analysis Method

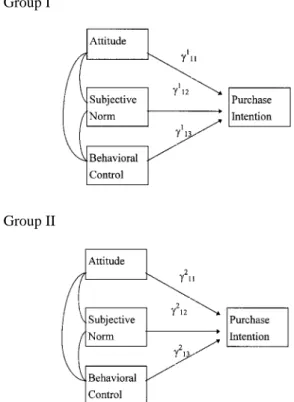

In order to compare the path coefficients between models, LISREL program was applied to analyze the data (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1989). The independent variables are attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. The dependent variable is purchase intention (Figure 1). Similar to the specification of the original model by Ajzen (1985), the correlations among indepen-dent variables were freed in estimating the model coefficients. The scores of the four major constructs were calculated based on the mean score of their indicators. The Cronbach Alpha for the four constructs are presented in Table 2. As shown in the table, the reliabilities of the four

Table 2. The Reliability of Major Constructs

Cronbach α Mean Variance

Attitude 0.95 4.69 1.68

Subjective Norm 0.94 4.43 1.77

Perceived Behavioral Control 0.87 4.61 2.57

Purchase Intention 0.88 3.79 1.97

Attention to Social Comparison 0.80 4.91 1.78 Information

Subjective Product Knowledge 0.93 3.36 2.29 Objective Product Knowledge* 0.63 0.21 0.04 * True/false questions

Fig. 1. Path Model of the Research Framework

Group I

constructs are satisfactory. All of them are higher than 0.80 except the objective knowledge.

To test the moderating effect for each moderating variable (i.e., subjective product knowledge, objective product knowledge, and attention to social comparison information), there are two stages in the data analyzing process. In the first stage, the sample is divided into two groups based on the subject’s score ranking of the specific moderating variable. Therefore, for subjective product knowledge, there is a high subjective knowledge group and a low subjective knowledge group. For objective prod-uct knowledge, there is a high objective knowledge group and a low objective knowledge group. Finally, for ATSCI, there is a high ATSCI group and a low ATSCI group. For each group, a path model using the LISREL program is calculated. Path coefficients (γ in LISREL term) are used to test the significance of each independent variable.

At the second stage, the moderating effect of each moderating variable is tested. Since there are two groups for each moderating variable, two group stacked models are used to test whether the individual gamma coefficients are equal between two groups. For example, to test whether the path coefficient between attitude and purchase inten-tion are equal between two groups, 1

11

γ is specified to be equal to 2

11

γ . The Chi-squared value difference between the restricted model and the base model is used to test the equality of the path coefficient.

3. Results

The results of the model estimation are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

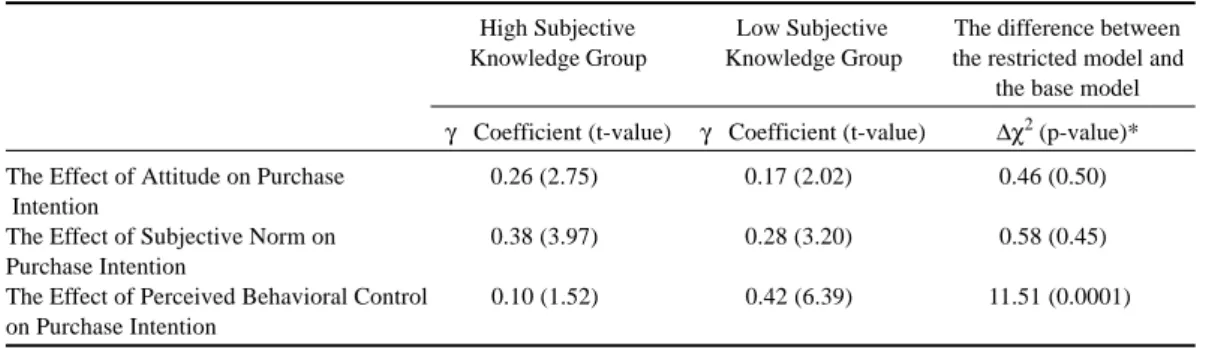

A. The Moderating Effect of Subjective Knowledge

The results of the path coefficients showed that all three independent variables (i.e., attitude, subjective norm,

and perceived behavioral control) had significant effects on purchase intention in the low subjective knowledge group (t = 2.02, p < 0.02; t = 3.20, p < 0.001; t = 6.39, p < 0.0001, respectively) (Table 3). However, only attitude and subjective norm had significant effects on purchase intention in the high subjective knowledge group (t = 2.75, p < 0.001; t = 3.97, p < 0.0003, respectively). This is consistent with the discussion in the literature review section. That is, perceived behavioral control reflects a person’s self-confidence in the ability to form behavioral intention. When a person has a high level of self-confi-dence in evaluating a product purchasing decision, per-ceived behavioral control will not be a major issue in in-fluencing his/her intention. On the other hand, when a person has a low level of self-confidence, perceived be-havioral control will become a salient factor in affecting his/her behavioral intention.

The results of the equality constraint model also showed that γ coefficients depicting the relationship be-tween perceived behavioral control and purchase inten-tion were significantly different between the two groups (χ2

differences = 11.51, p < 0.0001) (Table 3). That is, the effect of perceived behavioral control on behavior inten-tion was stronger when consumers have low subjective product knowledge than when consumers have high sub-jective knowledge. Subsub-jective knowledge moderated the relationship between perceived behavior control and be-havioral intention. Therefore, H1b and H1c were sup-ported by the data.

B. The Moderating Effect of Objective Knowledge

The results of the path coefficients showed that all three independent variables (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) had significant effects on the purchase intention in both the low and the high ob-jective knowledge group (Table 4). The results of the

Table 3. The Results of the Moderating Effects of Subjective Knowledge

High Subjective Low Subjective The difference between Knowledge Group Knowledge Group the restricted model and

the base model γ Coefficient (t-value) γ Coefficient (t-value) ∆χ2 (p-value)*

The Effect of Attitude on Purchase 0.26 (2.75) 0.17 (2.02) 0.46 (0.50)

Intention

The Effect of Subjective Norm on 0.38 (3.97) 0.28 (3.20) 0.58 (0.45)

Purchase Intention

The Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control 0.10 (1.52) 0.42 (6.39) 11.51 (0.0001) on Purchase Intention

equality constraint tests also showed that γ coefficients for all three relationships were not significantly different be-tween the two groups (Table 4). That is, objective knowl-edge did not moderate the relationship between the three antecedents and behavioral intention. This is also consis-tent with the discussion in the literature review section. Objective knowledge reflects one’s true knowledge about the subject matter. It does not contain a person’s self-confidence in the ability to form behavioral intention. Therefore, the effects of the three antecedents on behavior intention were equal between the two groups. Therefore, H2 was supported by the data.

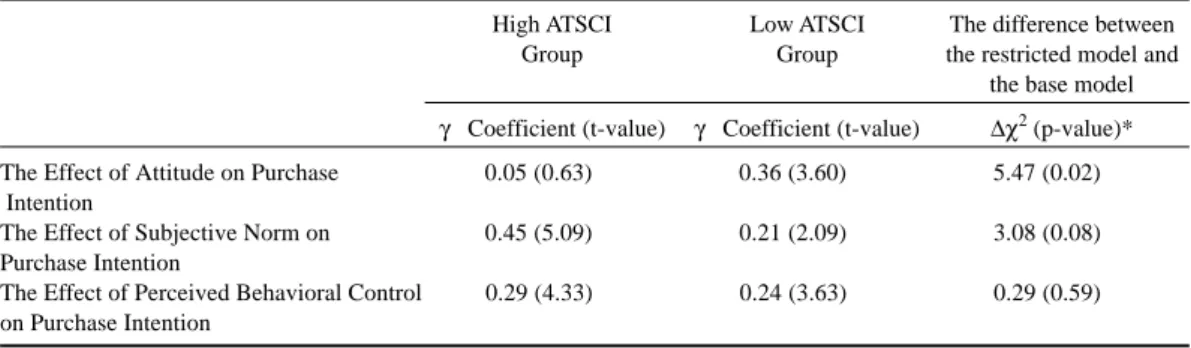

C. The Moderating Effect of ATSCI

The results of the path coefficients showed that all three independent variables (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) had significant effects on the purchase intention in the low ATSCI group (t = 3. 60, p < 0.0004; t = 2.09, p < 0.02; t = 3.63, p < 0.0003, respectively) (Table 5). However, only subjective norm and perceived behavioral control had significant effects on purchase intention in the high ATSCI group (t = 5.09,

p < 0.0001; t = 4.33, p < 0.0001, respectively) (Table 5). The results of the equality constraint model showed that the γ coefficients depicting the relationship between atti-tude and purchase intention, and the relationship between subjective norm and purchase intention were significantly different between the two groups (χ2

differences = 5.47, p < 0.02; χ2

differences = 3.08, p < 0.08, respectively) (Table 5). The effect of attitude on behavioral intention was stronger when consumers have low ATSCI than when consumers had high ATSCI. On the other hand, the ef-fects of subjective norm on behavioral intention were stron-ger when consumers had high ATSCI than when consum-ers have low ATSCI.

These results are also consistent with discussion in the literature review section. When consumers possess high degree of ATSCI, they will pay more attention to other’s opinion than those who have low ATSCI when forming behavioral intention. The results also showed that the effect of attitude on purchase intention will become insignificant when consumers have high ATSCI. This means that for the high ATSCI consumer, personal atti-tude may be overshadowed by other’s opinion. This dem-onstrated that ATSCI is a strong moderator in the

relation-Table 5. The Results of the Moderating Effects of ATSCI

High ATSCI Low ATSCI The difference between

Group Group the restricted model and

the base model γ Coefficient (t-value) γ Coefficient (t-value) ∆χ2 (p-value)*

The Effect of Attitude on Purchase 0.05 (0.63) 0.36 (3.60) 5.47 (0.02)

Intention

The Effect of Subjective Norm on 0.45 (5.09) 0.21 (2.09) 3.08 (0.08)

Purchase Intention

The Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control 0.29 (4.33) 0.24 (3.63) 0.29 (0.59) on Purchase Intention

Table 4. The Results of the Moderating Effects of Objective Knowledge

High Objective Low Objective The difference between Knowledge Group Knowledge Group the restricted model and

the base model γ Coefficient (t-value) γ Coefficient (t-value) ∆χ2 (p-value)

The Effect of Attitude on Purchase 0.19 (2.06) 0.19 (2.01) 0.001 (0.98)

Intention

The Effect of Subjective Norm on 0.38 (4.10) 0.33 (3.24) 0.11 (0.73)

Purchase Intention

The Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control 0.21 (3.05) 0.30 (4.24) 0.92 (0.34) on Purchase Intention

ship between attitude and purchase intention, and the rela-tionship between subjective norm and behavioral intention. Therefore, H3a, H3b, and H3c were supported by the data.

IV. Discussion and Implications

This study showed that the relative importance of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral con-trol in the prediction of intention varies when consumers possess different subjective product knowledge or social information comparison disposition. Subjective knowl-edge was a moderating variable for the relationship be-tween perceived behavioral control and purchase intention, while ATSCI was a moderating variable for the relation-ship between attitude and purchase intention, and the rela-tionship between subjective norm and purchase intention. Based on these results, there are several marketing implications for marketers.

1. Product Marketing

When purchasing a product without much volitional control, consumers may need not only more resources (time, information, etc.), but also more self-confidence in making a suitable decision. Marketers should have to try not only to ease consumers’ effort in processing product message, but also to promote consumers’ perceived be-havioral control. For example, they can use more demon-strations to show the product’s performance. They also can invite expert celebrities to sponsor the product in or-der to enhance consumers’ confidences.

2. Consumer Attitude Measurement

In most types of the standard market studies such as product testing and concept testing, personal attitudes to-ward the product are the major questions in the measurement. Subjective norm normally is not included in the measurement. This kind of omission will not ad-equately capture all antecedents of purchase intention for consumers with high ATSCI requirements. To accurately estimate this group of consumers’ purchase intentions, sub-jective norm must be included in the questionnaire. In addition, for products that need a lot of knowledge and self-confidence for consumers, perceived behavior con-trol should be included in the measurement.

3. Communication Channel

To reach different consumer segments, marketers should be very versatile in adopting communication

channels. To influence high ATSCI consumers effectively, traditional media (i.e., TV, radio, and newspaper, etc.) is not enough. The communication media should be consid-ered as the stimulus for enhancing the effectiveness of the inter-personal channel. In addition, marketers also should explore which kind of reference/social groups has the most influential power in persuading the consumers to adopt their products. The communication program should reach all these groups instead of the target markets only. Let members in the social/reference group get acquainted with the product and know its benefits. This can reduce the resistance from these groups.

V. Limitations and Future Research

Several issues for future research need to be addressed. First, future research should identify more product char-acteristics that can affect the results. In this study only one product type, the computer printer, was examined. Other product types can be explored in future studies. Second, consumers in different countries may have differ-ent sources of social pressure. Researchers can find out the most influential reference group for each specific na-tional culture. For example, the most important reference/ social group for Chinese may be the family and the ex-tended family (Yang, 1972), while for Japanese, it may also include their colleagues (Hall, 1976). Identifing the reference/social groups for each society can help market-ers design a more effective marketing programs. Further-more, different groups may exert a different influencing power on the individual for his/her consumption decisions regarding different product types. Future research should explore more contingency variables for these situations.

Third, the use of student subjects may limit the generalizabilities of the findings. It is possible that people in different generations possess dramatically different ATSCI propensity. For example, older generations are normally considered to be more collectivist than younger generations (Hofstede, 1983; Triandis, 1994). Subjective norm may have stronger effect on purchase intention if older generation subjects were studied.

Finally, this study can be extended to be an interna-tional comparative study. Lee and Green (1991) found that subjective norm was a significant predictor for be-havioral intention in Korea, while attitude was found to overshadow the influence of subjective norm in the United States. These results demonstrated that the strength of social influences are different in different cultural environments. It is important to explore whether the ef-fect of perceived behavioral control on purchase intention varies in different cultures.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported partly by National Science Council Grant NSC 87-2416-H-004-016. The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their help-ful comments.

Appendix A

The Attention to Social Comparison Information Scale

1. It is my feeling that if everyone else in a group is be-having in a certain manner, this must be the proper way to behave.

2. I actively avoid wearing clothes that are not in style. 3. At parties I usually try to behave in a manner that

makes me fit in.

4. When I am uncertain how to act in a social situation, I look to the behavior of others for cues.

5. I try to pay attention to the reactions of others to my behavior in order to avoid being out of place. 6. I find that I tend to pick up slang expressions from

others and use them as part of my vocabulary. 7. I tend to pay attention to what others are wearing. 8. The slightest look of disapproval in the eyes of a

per-son with whom I am interacting is enough to make me change my approach.

9. It’s important for me to fit into the group I’m with. 10. My behavior often depends on how I feel others wish

me to behave.

11. If I am the least bit uncertain as to how to act in a social situation, I look to the behavior of others for cues.

12. I usually keep up with clothing style changes by watch-ing what others wear.

13. When in a social situation, I tend not to follow the crowd, but instead behave in a manner that suits my particular mood at the time.

Appendix B

Please answer the following questions. If the state-ment is true, please circle “True.” If the statestate-ment is wrong, please circle “False.” If you don’t know, please circle “Don’t Know”

Don’t True False Know

T F D 1. Generally speaking , ink-jet car-tridges for ink-jet printers are expensive, making operating costs more expensive than a laser or a dot-matrix printer.

T F D 2. Ink-jet printers use xerographic technology.

T F D 3. An Ink-jet printer normally requires less electronic energy than a laser or a dot-matrix printers.

T F D 4. The term “dbi” is used to measure printing quality.

T F D 5. The image of an ink-jet printer is elec-tronically created on a light-sensitive drum. A powdered toner sticks to the area where light touches the drum and then transfers to a sheet of paper. T F D 6. A daisy wheel printer is one kind of

dot-matrix printer.

T F D 7. Normally “ppm” is used to measure the printing speed of a dot-matrix printer.

T F D 8. Other thing being equal, the larger the memory of a printer, the better the “spooling” function for the com-puter system.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action Control:

From Cognition to Behavior (pp. 11-39). NY: Springer Verlag.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational

Be-havior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Ajzen, I. & Driver, B. L. (1992). Applications of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24, 207-224.

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and

predict-ing social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I. & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal

of Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 453-474.

Alba, J. W. & Hutchinson J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 411-454. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unified theory of

behav-ioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy: Mechanism in human agency.

Ameri-can Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

Bearden, W. O. & Rose, R. L. (1990). Attention to social comparison information: An individual difference factor affecting consumer conformity. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 461-471. Brislin, R. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written

materials. In: H. C. Triandis and J. W. Berry (Eds), Handbook of

Cross-Cultural Psychology (Vol. 2, pp.389-444). Boston, MA:

Allyn and Bacon.

Brucks, M. (1985). The effects of product class knowledge on informa-tion search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 1-16. DeBono, K. G. (1987). Investigating the social-adjustive and value-expressive functions of attitudes: Implications for persuasion processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 279-287.

DeBono, K. G. & Edmonds, A. E. (1989). Cognitive dissonance and self-monitoring: A matter of context?. Motivation and Emotion,

13, 259-270.

DeBono, K. G. & Packer, M. (1991). The effects of advertising appeal on perceptions of product quality. Personality and Social

Psy-chology Bulletin, 17, 194-200.

Fishbein, M. A. (1967). Readings in attitude theory and measurement. New York, NY: Wiley.

Fishbein, M. A. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and

behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Doubleday. Hofstede, G. (1983). The culture relativity of organizational practices

and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14, 75-89.

Joreskog, Karl G. & Sorbom, D. (1989). LISREL 7: A guide to the

pro-gram and applications. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

Lee, C. & Green, R. T. (1991). Cross-cultural examination of the Fishbein behavioral Intentions model. Journal of International Business

Studies, 22, 289-305.

Lennox, R. D. & Wolfe, R. N. (1984). Revision of the self-monitoring scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 1349-1364.

Lessig, V. P. & Park, C. W. (1982). Motivational reference group influences: Relationship to product complexity, consciousness and brand distinction. European Research, 91-101.

Liska, A. E.(1984). A critical examination of the causal structure of the Fishbein/Ajzen attitude behavioral model. Social Psychology

Quarterly, 47, 61-74.

Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implica-tions for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological

Review, 98, 224-253.

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J. and Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The

measure-ment of meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Park, C. W., Mothersbaugh, D. L. & Feick, L. (1994). Consumer knowl-edge assessment. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 71-82. Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and

pe-ripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 135-145. Ryan, M. J. (1982). Behavioral intention formation: The

interdepen-dency of attitudinal and social influence variables. Journal of

Consumer Research, 9, 263-278.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J. & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recom-mendations for modifications and future research. Journal of

Consumer Research, 15, 325-343.

Snyder, M. & DeBono, K. G. (1985). Appeals to images and claims about quality: Understanding the psychology of advertising.

Jour-nal of PersoJour-nality and Social Psychology, 49, 586-597.

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. (1995). Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12, 137-156.

Triandis, H. (1994). Culture and social behavior. New York, NY: Praeger.

Yang, M. C. (1972). Familism and Chinese national character. In: Y. Y. Lee & K. S. Yang (Eds.), Symposium on the Character of the

Chinese (pp. 127-174), Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Ethnology,

(attitude)

Ajzen (1985, 1991) the Theory of Planned Behavior