行政院國家科學委員會

獎勵人文與社會科學領域博士候選人撰寫博士論文

成果報告

The determinants and performance of R&D

cooperation: evidence from Taiwan high-technology

industries

核 定 編 號 : NSC 95-2420-H-004-067-DR 獎 勵 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 96 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學會計學系 指 導 教 授 : 吳安妮 博 士 生 : 黃政仁 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 96 年 07 月 17 日

國立政治大學會計學系博士班博士論文

Department of Accounting

National Chengchi University

指導教授:吳安妮 教授

Advisor:Professor Anne Wu

研發合作之決定因素與績效:以台灣高科技產業為例

The Determinants and Performance of R&D Cooperation: Evidence from

Taiwan’s High-Technology Industries

研究生:黃政仁撰

Name:Cheng-Jen Huang

中華民國 九十六 年 四 月

To my mother, my wife Mirrian, and two sons Yu-Tang and Yu-Chen 獻給我的母親、我的太太瑞芬、與兩個小孩語棠和語晨

Acknowledgements

This dissertation would not have possible without the invaluable support and encouragement from many persons. My gratitude to my advisor, Professor Anne Wu, is beyond words and will last a life-time. She inspires my interest in management accounting research and initiates me into a researcher’s world. I greatly admire her academic achievement and research spirit. She always says “I want to do research until the last day I die.” Moreover, she not only emphasizes the importance of academic research, but also values honesty and integrity. Professor Wu is the best model for my whole life. I am equally grateful to Professor Jong-Tsong Chiang, Hsion-Wei Lin, Chu-Chia Lin, Chen-Lung Kim, Chung-Jen Chen, Shu-Heng Chen, and Mu-Yen Hsu. Each of them spend lots of time patiently listening to and refining my ill-formed ideas, and providing me constructive suggestions on theory and methodology during my oral defense. Their helpful comments benefit this work.

I was very fortunate to receive the scholarship from National Science Council, and had a one year research visit at University of Arizona. I greatly appreciate the support from my U.S. advisor, Professor Leslie Eldenburg. Her sincere attitude towards teaching and research deeply impressed me. My warmest thanks are also extended to Professor Kendra Gaines, Professor Rabah Amir, Lance Fisher, James Breedlove, William Pack, Hsin-Ming Lu, and Chen-Cheng Chun for their guidance, help, and support during my stay at University of Arizona. Especially, Hsin-Ming helped me to derive the solutions for the theoretical model and collect the empirical data from the website. This dissertation could not have been complete smoothly without his continuing assistance.

My deep thanks also go to my dear friends for their being constantly supportive, including 淩淇, 秋田, 佳琪, 美珠, 心瑤, 玉麟, 全斌, 惠玲, 倩如. 隨樺, 伶珠, 翠菱, 素芳 are also my best partners. Thank you for your great support and encouragement all the time. To 俊 儒 , words cannot fully express my sincere thankfulness for your help during the Ph.D. phase of the program. To 玉元, you not only helped me to complete master thesis more than ten years ago, but also provided me a lot of industrial experience which enriches my dissertation. You are my lucky star. To assistant 育綺, 景良, 順華, 怡霙, thank you for your enthusiastic aid for these years. I also grateful to the colleagues of Accounting Department at the

Overseas Chinese Institute of Technology as well as Tunghai University (my next academic home), for your confidence in me and your support and encouragement for my work.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my mother, my wife, and my two sons: Yu-Tang and Yu-Chen. I am deeply indebted to their unfailing support, both in the emotional and the financial aspects. My mother’s blessing and, especially, my wife’s great sacrifices have made this dissertation possible.

致謝 近七年的博士班生活即將告一段落,回首過往,歷經了許多難得且精彩的人 生,而最大的體會是,論文與博士學位絕非只靠一個人可以完成的,需要許多師 長、朋友、甚至貴人的從旁協助,才能順利度過每一個重要的關卡。 我想,進入政大博士班以來最明智的決定就是選擇了吳安妮教授作為我的指 導教授,吳老師從我入學後就費心地教導我如何作研究,連家裡的事也常常讓她 擔心。老師每天總是工作到晚上 12 點才得以休息,近 20 年來如一日。老師的學 術成就和研究精神是我最敬佩的,她總是說:「我要做研究直到離開人世間的前 一天」,環視整個學術界,應該很難再找到如此對學術研究堅持的學者吧!老師 不僅著重學術研究外,更特別重視品格與道德,強調做一個學者,誠信與正直更 是重要,正如「勇者無懼、智者無惑、仁者無敵」。對於我而言,吳老師做了最 好的身教與言教的典範,是我終生學習的標竿。 口試委員江炯聰老師、林修葳老師、林祖嘉老師、金成隆老師、陳忠仁老師、 陳樹衡老師、許牧彥老師在學生論文口試期間,百忙之中撥冗參與我的論文口 試,每位老師不管在理論或是實證方法上都給予極具建設性的建議與指導,使得 學生論文架構更臻完善,研究方法更為恰當,進而提升本論文的整體價值,在此 致上我最誠摯的謝意。 在博士班求學過程中,有幸獲得國科會「千里馬計畫」之補助赴美國亞利桑 納大學進行為期一年的研究,會計系教授 Leslie Eldendurg 從頭到尾全力地協助 我處理學校與生活的事情,她在教學與研究上敬業的態度,也讓我深深欽佩。感 恩節大餐後與她、師丈 John、及他們家人玩橋牌、玩拼圖的熱絡景象,讓我永 難忘懷。系上博士生 Lance 亦常邀請我參加家庭聚會,他與太太 Krystyl 準備的 美食,五位活潑的小孩 Kaihe、Krykyt、Mela、Piikea、Samuel,加上搞笑又感人 的夏威夷傳奇電影,讓我度過最快樂的週末時光。Kendra 是一位亞利桑納大學 英語文學系退休的老師,她用心地幫我修改論文,下午茶時間與她及師丈 Ken 分享不同文化的差異、卻能激盪出相同的價值觀,聆聽共同喜愛的大樂團時代爵 士樂以及馬友友的大提琴,真是人生一大享受。 撰寫論文過程中若有貴人的話,那非信銘莫屬,他早我一週到亞利桑納大學

居。由於他過去念經濟,又精通程式,因此論文數學模式推導與網路資料蒐集方 面的問題,都是他一一幫我解決,沒有他,我想論文大概很難順利完成的。另外, Rabah Amir 教授是一位研究傑出的經濟系老師,雖然之前我們從未謀面,但他 仍熱心的為我解答模型設定上的問題,讓我更有信心解決理論上所遭遇的困難, 在此一併感謝。而 Jim 是我在美國時的會友,他總是固定每週來看我,不斷鼓 勵我,給我信心與勇氣,希望 2009 年我們有機會在台灣相聚。最後,在美期間, 語言所博士班的鎮城也正在撰寫論文,因此我們成為無所不聊的好朋友,我會珍 惜這難得的友誼。 博士班的生活中,由於修課、準備資格考、長時間在研究室中和學長姐、同 學、學弟妹們的相處,因此培養出特殊的革命情感,包括淩淇、秋田、佳琪、美 珠、心瑤、玉麟、全斌、惠玲與倩如,謝謝妳們無時無刻的關心與鼓勵,隨樺、 伶珠、俊儒、翠菱、與素芳更是互相扶持與勉勵的好伙伴,特別是俊儒,從一年 級到現在(甚至未來),一直受到他的照顧與幫忙,實在難以用筆墨形容,「大 師兄」的稱號實至名歸。碩士班同學玉元早從碩士論文程式與實證分析,他與姊 姊就提供我極大的協助,沒想到在博士論文的撰寫階段,仍借重不少他在實務界 豐富的經驗,使得本論文可以在理論與實務方面有更密切的結合,是我另一位貴 人。感謝我在僑光技術學院任教期間,商學院院長暨會計系主任賴怡君教授與同 事們對我的照顧與支持,也感謝東海大學會計系許恩得主任與各位老師們願意接 納我,讓我加入東大會計的大家庭。最後,我也要特別感謝助理育綺、景良、順 華、及怡霙在博士班過程中的熱心協助。 其實,這七年一路走來最辛苦的人,就是我的太太—瑞芬,六年多前就讀博 士班的同時,我們結婚了,自此,她就承擔起家裡所有的事情。隨著老大語棠與 老二語晨的出生,負擔越來越重,為此還捨棄進修研究所的計畫。尤其在我出國 的一年期間,工作與小孩兩頭忙,心力交瘁。記得剛到美國不久,語棠半夜因細 菌感染發燒而掛急診住院,電話結束前妳流下了無助的眼淚,但我卻一點忙都幫 不上,心裡真的很難受。長時間的睡眠不足,也讓妳身體健康大受影響,大家都 說妳的犧牲太大了,面對這七年來的煎熬,好像也只能用「妳上輩子欠我的」, 才能合理解釋這完全不對等的付出。希望畢業後,我可以為家庭分擔更多的家 事,也能協助妳達成夢想。

最後,我要把這本博士論文獻給我的母親,她年輕時獨自扶養我長大,現在 則總是默默地祝福我做的每一件事,做我最佳的後盾,希望自己有更多的時間陪 伴她,讓過去所有的辛苦與犧牲都值得。博士班學業的結束,只是劃下人生一個 逗點,新的學術生涯才要真正開始,未來的日子,我會盡力投入研究、教學、與 家庭上,期望這一生能為社會作出更大的貢獻。 黃政仁 謹識於政治大學 261143 室 中華民國 96 年 4 月 27 日

Abstract

Innovation is complex, costly, and risky and incurs externalities. R&D cooperation is thus a proper mechanism to encourage firms to innovate. The purposes of this dissertation are to extend the prior theoretical framework and empirical studies to establish a research framework for the R&D cooperation—innovation—financial performance chain. The research questions are as follows:

1. Do absorptive capacity, knowledge spillovers, and uncertainty affect the intensity of R&D cooperation?

2. Does R&D cooperation result in higher R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance?

3. How do different R&D cooperation types influence the determinants of R&D cooperation?

4. How do different R&D cooperation types influence the performance of R&D cooperation?

5. Is the effect of R&D cooperation on financial performance mediated by R&D investments and R&D outputs?

In this dissertation I apply the two-industry, n-firm-per-industry Cournot competition models to theoretically examine the relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments (input perspective of innovation), R&D outputs (output perspective of innovation—non-financial performance), and financial performance. I then use Taiwan’s high-technology industry as a research sample and empirically test my research hypotheses. The results provide academia and practitioners with a more comprehensive view of R&D cooperation and innovation activity among Taiwan’s high-technology industries.

The empirical results support the argument that absorptive capacity has a positive impact on the frequency of R&D cooperation in high-technology industry. In addition, an increase in knowledge spillovers also tends to increase intensity to collaborate in R&D. Under high absorptive capacity and knowledge spillover, generalized R&D cooperation is preferred to other cooperative models.

high-technology firms to invest more resources in R&D, and leads to higher R&D outputs and financial performance under the characteristic of high knowledge spillovers. Relative to other cooperation types, generalized cooperation leads to higher R&D outputs and financial performance and is a superior cooperative model. Due to the nature of market competition, horizontal cooperative firms are not willing to invest too much in R&D relative to vertical cooperation and generalized cooperation. Finally, simply investing in R&D alone is not enough to achieve breakthrough performance and sustain a competitive advantage. The ability to innovate and generate R&D outputs determines the profitability of the cooperative company.

Key words: R&D cooperation, Innovation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, financial performance, high-technology industry, mediating effect.

摘要 創新是複雜、昂貴、且高風險的活動,並且存在外部性,研發合作為促使企 業從事創新的重要機制。本研究目的在於延伸過去理論性架構與實證研究,建立 研發合作—創新—財務績效價值鏈。以下為研究問題: 1. 吸收能力、知識外溢、與不確定性是否會影響研發合作的頻率? 2. 研發合作是否可以提高研發投資、研發產出、與財務績效? 3. 不同的研發合作型態如何影響研發合作的決定因素? 4. 不同的研發合作型態如何影響研發合作的績效? 5. 研發合作與財務績效的關係是否會受到研發投資與研發產出的中介影響?

本研究採用 two-industry, n-firm-per-industry Cournot 競爭模型探討研發合

作、研發投資(創新之投入面)、研發產出(創新之產出面—非財務績效)、與財 務績效的關係,並以台灣高科技產業為研究對象進行實證分析。對於台灣高科技 產業的研發合作與創新活動,研究結果提供學術界與企業界更完整且廣泛的觀 點。 實證結果支持公司擁有較高吸收能力的員工是從事研發合作的決定因素之 一。另外,知識外溢的提高,亦將促使高科技公司進行研發合作。而在高度吸收 能力與知識外溢下,公司採行一般合作之頻率較其他合作模式高。 另外,實證結果也發現研發合作的確鼓勵台灣高科技產業的公司進行更多研 發的投資,並且持續創造較高的研發產出與財務績效。相對於其他合作型態,一 般合作可以創造較高的研發產出與財務績效,因此為較佳的合作模式。而由於市

場競爭的本質,使得水平合作公司之研發投資較垂直合作與一般合作少。最後, 僅有研發投資並不足以提升公司的績效與維持競爭優勢,研發合作公司的創新能 力與研發產出才是獲利力的決定因素。

關鍵字:研發合作、創新、研發投資、研發產出、財務績效、高科技產業、中介 效果

Table of contents

Acknowledgements ... IV 致謝... VI Abstract... IX 摘要... XI Table of contents... XIII List of Figures... XV List of Tables... XVI

Chapter 1: Introduction ...1

1.1 Research background ...1

1.2 Research motivation ...2

1.3 Research purposes and research questions...3

1.4 Significance of the research...5

1.5 Research framework...6

Chapter 2: Literature review ...9

2.1 The theoretical perspectives of R&D cooperation ...9

2.2 The determinants of R&D cooperation...20

2.3 The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-theoretical research ...28

2.4 The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-empirical research ...34

2.5 Extension of this study...41

Chapter 3: Theoretical model and hypotheses development ...47

3.1 The determinants of R&D cooperation...47

3.2 The impact of R&D cooperation on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...51

Chapter 4: Research method ...69

4.1 Conceptual framework ...69

4.2 Research sample and data collection...71

4.3 Variable measurement...72

4.4 Data analysis methods ...81

Chapter 5: Empirical results...83

5.1 Fundamental results ...83

5.2 Hypotheses test ...88

5.2.1 The determinants of R&D cooperation...88

5.2.2 The impact of R&D cooperation on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...94

5.3 Robustness test ...109 5.3.1 Sensitivity analysis for R&D investments, R&D outputs, and

5.3.2 Time-lagged effect analysis ... 114

5.3.3 Industry analysis ...125

5.3.4 Other analysis...132

Chapter 6: Conclusions ...133

6.1 Conclusions and implications...133

6.2 Research limitations...141

6.3 Future research ...142

References ...144

Appendix A: Simulation results ...158

Appendix B: Proofs of the proposition...170

Appendix C: The definition and classification of high-technology industries....172

Appendix D: Interview summary ...174

List of Figures

Figure 1: Research framework of this study ...8

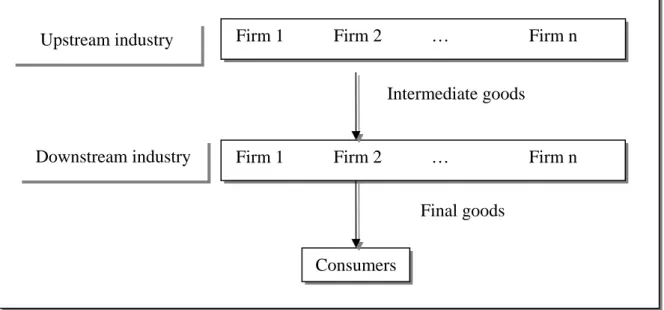

Figure 2: Market structure of the theoretical model of this study...51

Figure 3: The three-stage Cournot competition ...52

Figure 4: Different types of R&D cooperation ...58

Figure 5: Hypothetical research framework of this study — The R&D cooperation — innovation — financial performance chain...70

Figure 6: The path between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...109

Figure 7: The path between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...114

Figure 8: The path between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (One-year lag)...124

Figure 9: The path between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (Two-year lag) ...124

Figure 10: The path between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (Three-year lag) ...125

List of Tables

Table 1: The definitions of R&D cooperation ...10

Table 2: The classifications of R&D cooperation ...13

Table 3: The benefits of R&D cooperation ...15

Table 4: Theoretical perspectives on R&D cooperation...18

Table 5: Literature summary of the determinants of R&D cooperation ...24

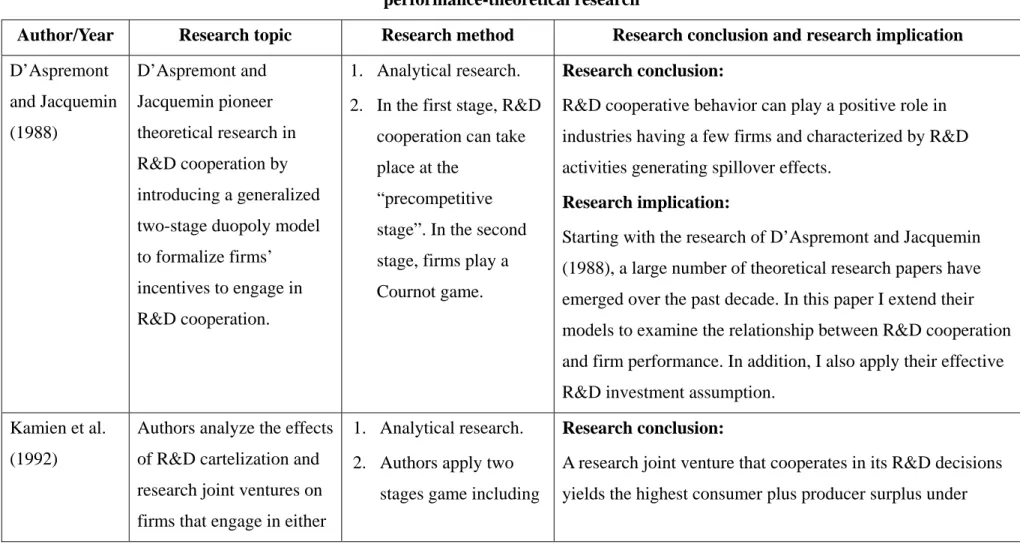

Table 6: Literature summary of the relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-theoretical research ...30

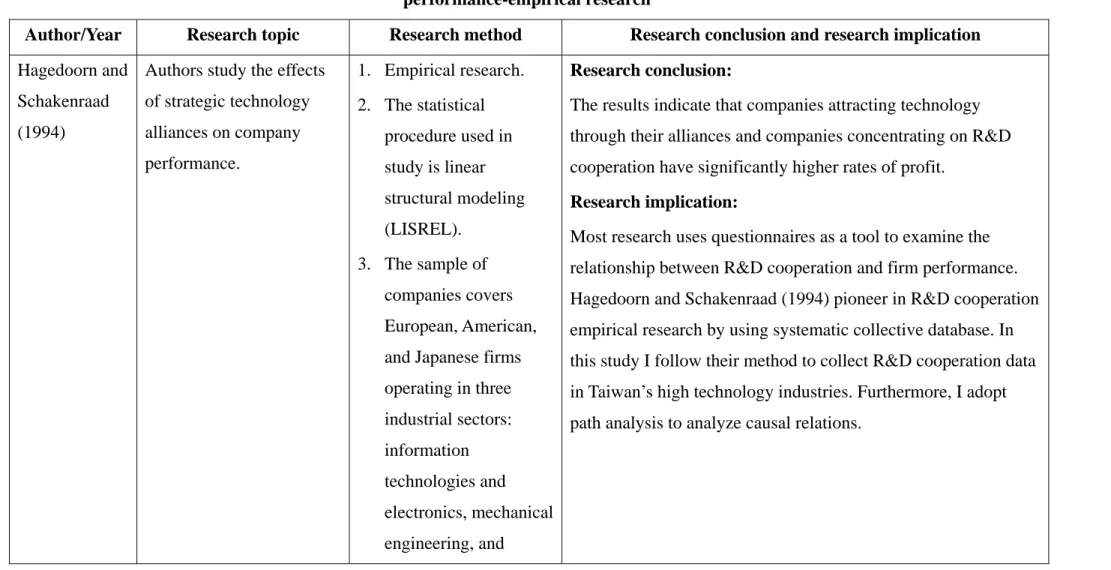

Table 7: Literature summary of the relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-empirical research ...36

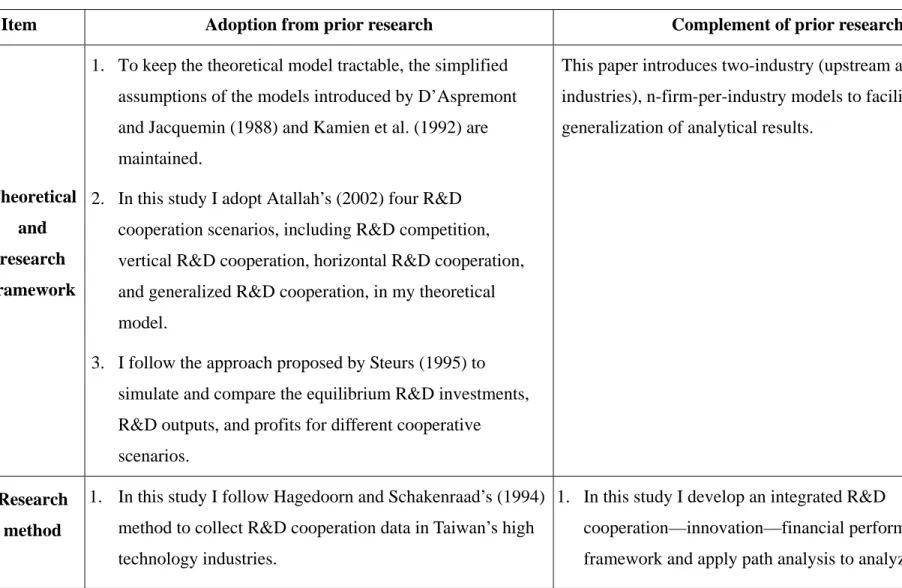

Table 8: Summary of the extension of this study...44

Table 9: Summary of model notation...54

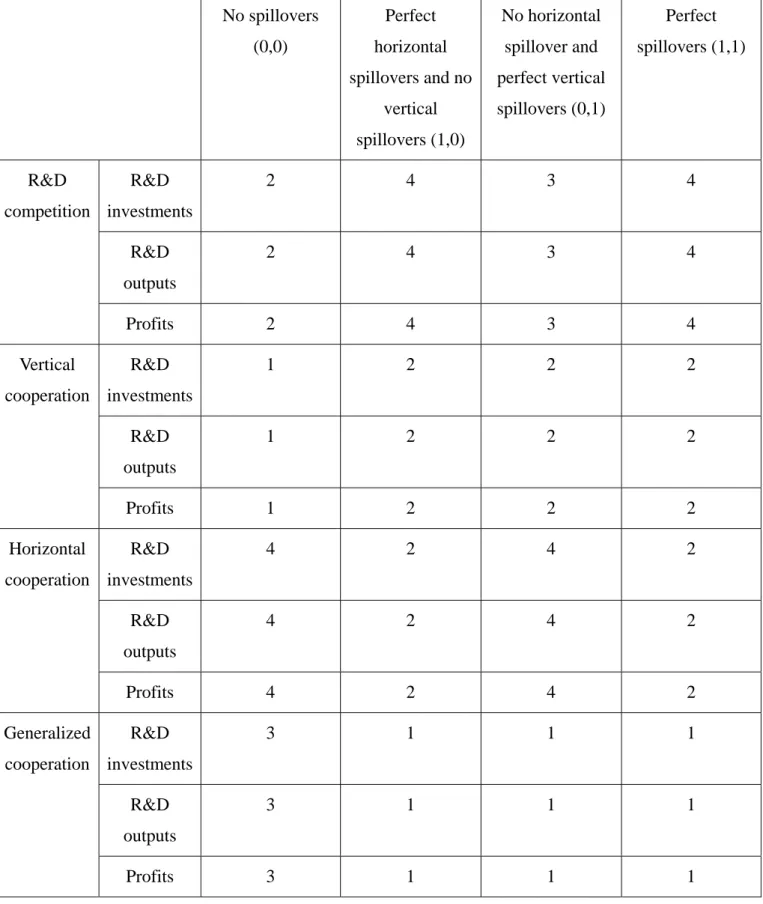

Table 10: Ranking of firms’ R&D investments, R&D outputs, and firm profits ...62

Table 11: Variable measurements for this study...79

Table 12: Descriptive statistics ...85

Table 13: Descriptive statistics for R&D cooperation and R&D competition...86

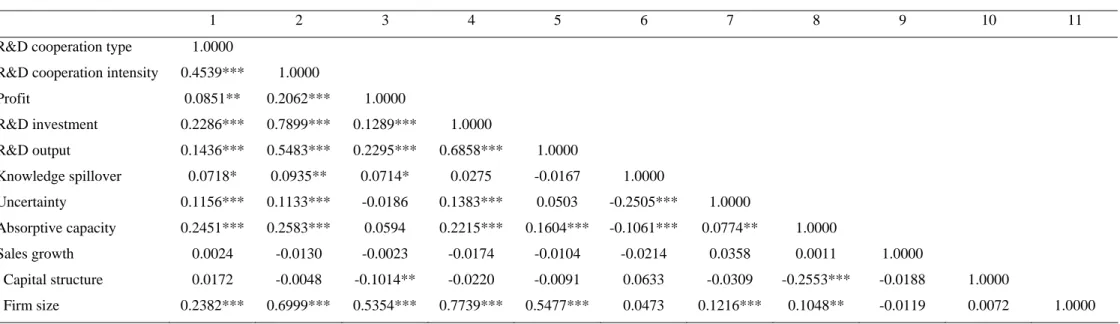

Table 14: Correction matrix among dependent variables and independent variables ...87

Table 15: The interaction between R&D cooperation types and the determinants of R&D cooperation ...92

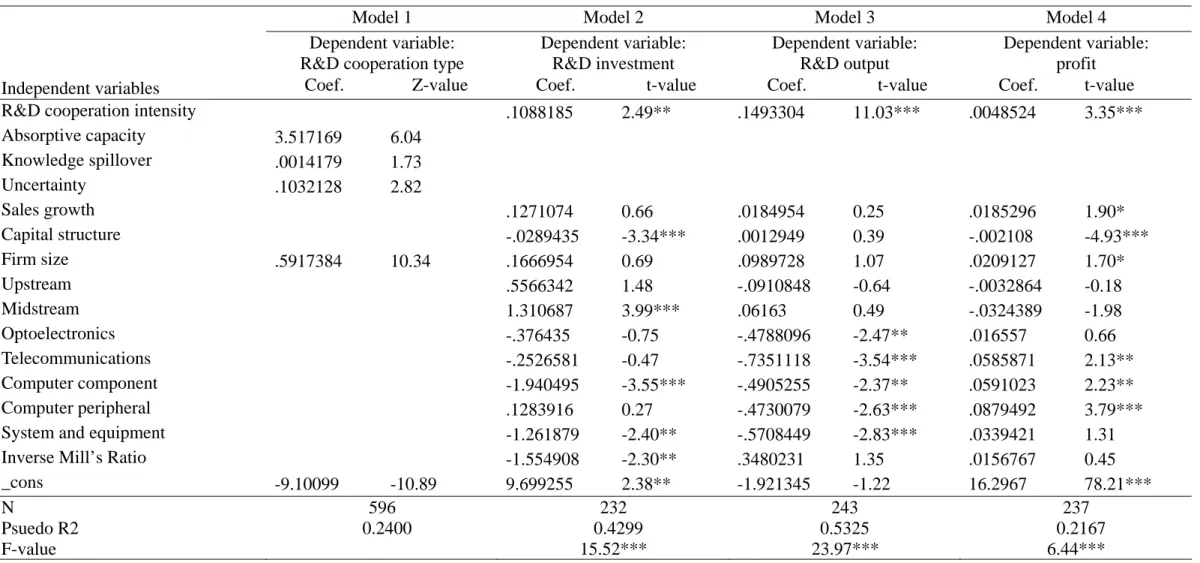

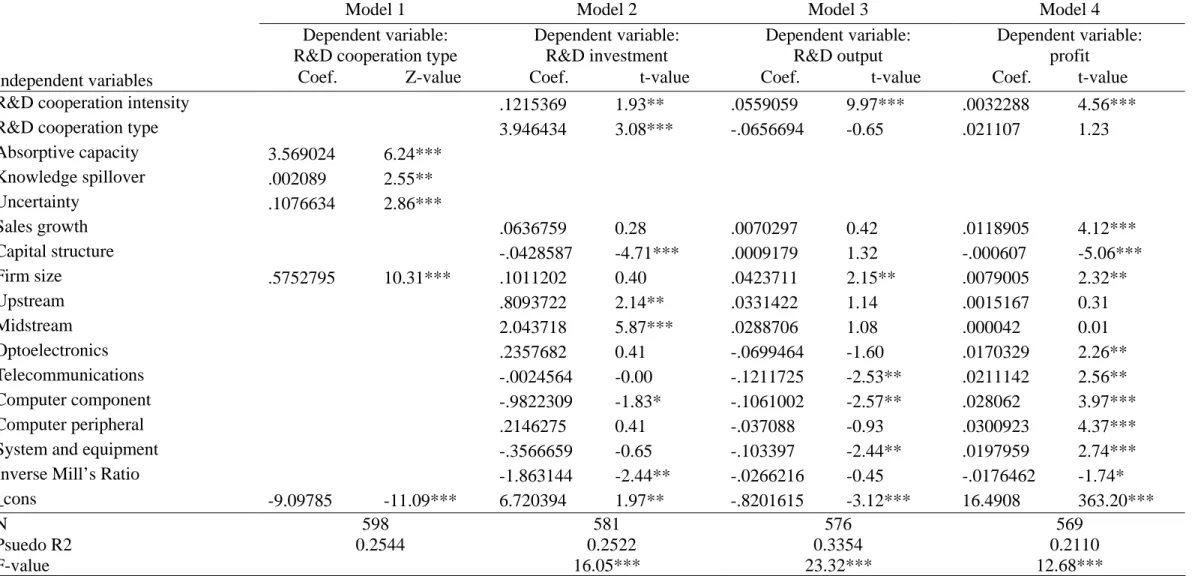

Table 16: The impact of R&D cooperation intensity on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance—Heckman two-step model ...96

Table 17: The impact of R&D cooperation intensity on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance—Treatment effects model ...99

Table 18: The impact of different R&D cooperation types on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...103

Table 19: The path analysis between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance ...107 Table 20: The impact of R&D cooperation on R&D intensity, revised R&D

outputs, and ROA... 111

Table 21: The path analysis between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, revised R&D outputs, and ROA ... 112

Table 22: The path analysis between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (One-year lagged model) ... 118

Table 23: The path analysis between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (Two-year lagged model) ...120

Table 24: The path analysis between R&D cooperation intensity, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance (Three-year lagged model) ...122

Table 25: The descriptive statistics of sub-industries ...126

Table 26: R&D investment regression model for sub-industries...129

Table 27: R&D output regression model for sub-industries ...130

Table 28: Profit regression model for sub-industries ...131

Table 29: Summary of conclusions and implications ...136

TableA1: R&D investments with three firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...158

TableA2: R&D outputs with three firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...159

TableA4: R&D investments with five firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...161

TableA5: R&D outputs with five firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...162

TableA6: Profits with five firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...163

TableA7: R&D investments with ten firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...164

TableA8: R&D outputs with ten firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...165

TableA9: Profits with ten firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition...166

TableA10: R&D investments with twenty firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition ...167

competition ...168 TableA12: Profits with twenty firms R&D cooperation and R&D competition...169 Table D1: The fundamental summary of two interviewed companies ...175

Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Research background

Innovation 1 has been shown to have significant effects on economic development in both academia and practice. In 1934 the well-known economist Schumpeter emphasized that innovation is a critical force that drives economic growth (Schumpeter 1934). Innovation is also one of the central points in Peter Drucker’s publications, “The Practice of Management” and “Innovation and Entrepreneurship” (Drucker 1954, 1985), in which he wrote, “The economy is forever going to change and is biological rather than mechanistic in nature. The innovator is the true subject of economics.” Intellectual property nowadays in fact receives a lot more attention, because innovation has become the most important resource, replacing land, equipment, and raw materials, in the knowledge economy (Lev 2004; Cukier 2005). As much as three-quarters of the value of U.S. publicly-traded companies comes from intangible assets. Alan Greenspan, former Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, also pronounced: “The economic product of the United States has become predominantly conceptual” (Cukier 2005).

Innovation in technology industries shows several interesting trends. First, information technology (IT) has become so complicated that firms are more willing to accept the innovation of others. Second, consumers are demanding “interoperability”2 and common standards rather than proprietary systems, which means that different firms’ technologies must work together smoothly. Third, information technology and telecommunications also rely on “network effects,” suggesting that as more people use a system, interoperability among different technologies becomes essential (Cukier 2005). Therefore, innovative activity, especially in high-technology industries, is increasingly cooperative.

Externalities also exist in innovation process. Externalities occur when a firm invests in research and development (R&D) that spills over to other firms, including competitors. Thus, any one firm benefits from other firms’ research. In this way,

1

Innovation is a creation (a new device or process) resulting from study and experimentation (Webster dictionary, http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/). Innovation is also the implementation of a new or significantly improved idea, good, service, process, or practice that is intended to be useful.

innovative companies will limit their new investments in R&D if they see a decreased likelihood of being able to make exclusive use of the results of their efforts (e.g. Spence 1984). On the other hand, if imitator firms can use the public stock of technological knowledge, then they reduce the level of effort invested in innovation (e.g. Levin and Reiss 1988; Henderson and Cockburn 1996). Therefore, externalities decrease both innovators’ and imitators’ incentives to invest in R&D (e.g. Kamien, Muller, and Zang 1992; Martin 2002).

A proper mechanism3 is needed to encourage firms, or the incentives to innovate will be distorted. According to prior literature (e.g. Kamien et al. 1992), R&D cooperation4 can restore firms’ incentive to engage in R&D, as it not only accelerates the speed of innovation with less risk, but also produces synergetic effects through the combination of new information, teams of specialists, and resources (e.g. Jacquemin 1988; Kamien 1992). Therefore, the cooperation between academies and industries (e.g. the cooperation between Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) and its high-technology industries) and the cooperation in inter-industry and intra-industry (e.g. the technology transfer between AUO, IBM Japan, and Matsushita) represent popular phenomena.

1.2 Research motivation

Starting with the work of D’Aspremont and Jacquemin (1988) and Kamien et al. (1992), a large number of theoretical research papers have emerged over the past decade attempting to formalize a firm’s private incentives to engage in horizontal R&D cooperation5 with horizontal knowledge spillovers (Ishii 2004). Researchers frequently use oligopoly models that allow for strategic interactions between firms. Although there are differences in assumptions across the various models, the results are quite robust: while non-cooperative R&D levels decrease with an increase in

3

Three instruments are usually considered to restore firms’ incentives to engage in R&D: (1) tax policies and direct subsidies, (2) patents and licensing, and (3) ex-ante R&D cooperation. While the first two instruments require government intervention to determine taxes and subsidies or to strengthen property rights, R&D cooperation is assumed to work through private incentives, because of the possibility to internalize R&D spillovers between cooperating firms (Katz and Ordover 1990).

4

R&D cooperation is defined as joint operation or action with R&D (Webster dictionary, http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/). I also use the word “R&D cooperation”, “R&D

collaboration”, “research partnership”, and “research joint venture”, etc, interchangeablely. For a more detailed description of R&D cooperation, please see Chapter 2.

5

Horizontal R&D cooperation means R&D cooperation between competing companies, while vertical R&D cooperation indicates R&D cooperation between buyers and suppliers. Generalized cooperation

knowledge spillovers, it has been shown that cooperative R&D investments, outputs, and social welfare tend to increase with the increase in spillovers (e.g. Veugelers 1998).

Most theoretical studies in R&D cooperation deal with horizontal cooperative R&D, with vertical cooperative R&D receiving little attention until recently (e.g. Atallah 2002; Ishii 2004). Cooperative relationships between final-goods manufacturers and input suppliers are crucial for successful innovation (Ishii 2004). Vertical R&D cooperation is desirable and is often voluntary under buyer-seller relationships, whereas horizontal R&D cooperation is involuntary and undesirable, because innovating firms have to face their competitors (Atallah 2002). Furthermore, the network relationships between firms become more complex, and the opportunities of engaging in R&D cooperation simultaneously among competitors, customers, and suppliers are getting more popular. Therefore, vertical R&D cooperation and generalized R&D cooperation should merit more attention from researchers.

Several studies also indicate that R&D cooperation provides future benefits (e.g. Kamien et al. 1992; Hagedoorn and Schakenraad 1994; Belderbos, Carree, and Lokshin 2004; Ishii 2004). Kamien et al. (1992) indicate that a research joint venture (RJV) that cooperates in its R&D decisions yields the highest consumer and producer surplus. Ishii (2004) points out that a RJV yields the largest social welfare. However, the direct relationship between R&D cooperation and financial performance does raise doubts because R&D cooperation must also invest in R&D and generate R&D outputs in order to lead eventually to profit generation. Therefore, I argue that R&D cooperation does not imply automatically higher levels of financial performance, and the impact of R&D cooperation on financial performance is mediated by R&D investments and R&D outputs (forward-looking measures). The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance needs further examination.

1.3 Research purposes and research questions

The purposes of this study are to extend prior theoretical framework and to introduce two industries, n-firm-per-industry models. In addition, I examine the determinants for engaging in R&D cooperation and the performance of R&D cooperation. I also provide a hypothetical framework for the R&D cooperation —

innovation — financial performance chain (See Figure 5).

Mathews and Cho (2000) show that the importance of R&D cooperation activity is instrumental in explaining the successful development of Taiwan’s high-technology industries. Taiwan’s high-technology industries are highly competitive and play a major role in the world, due to the successful business model of highly vertical disintegration (or vertical specialization).6 Nevertheless, Taiwan has received little attention because of the problem of difficult data collection. In this study, I use Taiwan’s high-technology industries as a research sample and empirically test the research hypotheses. The results provide companies, industries, and academia with a more comprehensive view of R&D cooperation and innovation activity in Taiwan’s high-technology industries.

The research questions are as follows:

1. Do absorptive capacity, knowledge spillovers, and uncertainty affect the intensity of R&D cooperation?

2. Does R&D cooperation result in higher R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance?7

3. How do different R&D cooperation types influence the determinants of R&D cooperation?

4. How do different R&D cooperation types influence the performance of R&D cooperation?

5. Is the effect of R&D cooperation on financial performance mediated by R&D investments and R&D outputs?

6

Vertical disintegration indicates industrial decentralization. Vertical disintegration spreads the risks and costs of R&D investments across multiple firms. In addition, every segment of production operates independently, and so the degree of specialization is high and the management difficulty is relatively lower. Vertical disintegration also enhances a firm’s ability to identify and respond quickly to potential market niches.

7

1.4 Significance of the research

This study contributes significantly to both academia and practice: 1. Contributions to academia:

(1) R&D cooperation studies face the problem of difficult data collection (e.g. Veugelers 1998). Thus, a survey questionnaire becomes a primary tool of R&D cooperation research and allows easy collection of data (e.g. Kaiser 2002a; Caloghirou, Hondroyiannis and Vonortas 2003; Chang 2003; Belderbos et al. 2004). However, certain limitations should be considered, as respondents may not understand or truly express the reality of R&D activity in firms. Respondents are likely influenced by the gaps between individuals’ and researchers’ perceptions of questionnaires. In this study I use archival data to prevent the deficiencies in the questionnaire survey. This is the first comprehensive empirical research discussing the relationships among R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance in Taiwan.

(2) In multiple linear regressions all effects are modeled to occur at a single level. In order to analyze the variance in outcome variables at multiple hierarchical levels, I employ the Hierarchical Linear Model (HLM) to examine the determinants of R&D cooperation. In addition, to avoid sample selection bias, I apply the Heckman two-step model and treatment effects model to estimate the probability of whether or not a firm engages in R&D cooperation. I then use OLS with adjusted items to estimate the impact of R&D cooperation intensity on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance. These methods will enhance the reliability of the empirical results and open new avenues in R&D cooperation research.

2. Contributions to practice:

(1) Prior literature indicates that companies concentrating on R&D cooperation have significantly higher profits (e.g. Hagedoorn and Schakenraad 1994; Ernst 2001). However, I suggest that R&D cooperation does not imply automatically higher levels of financial performance, and leading indicators in fact drive the financial performance of R&D cooperation. Therefore, this study first

outputs—financial performance framework and then applies the Path analysis to empirically test the causal relationship among R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance. The research results may have an important application for practitioners.

(2) Prior research discusses whether R&D cooperation impacts company’s R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance, and what the motivation of R&D cooperation is. This study first points out that not every R&D cooperation type can improve R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance. In addition, the intensity of R&D cooperation is also impacted by different R&D cooperation types.

(3) Taiwan is deemed a core innovator internationally. Based on the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) “Global Information Technology Report 2005-2006”, Taiwan is ranked seventh in the world. It is an innovation powerhouse, with levels of patents registration per capita exceeded only by the United States and Japan (Dutta, Lopez-Claros, and I. Mia 2006). Therefore, Taiwan has a high national competitive ability and has acquired international affirmation in innovation and technology aspects, especially in its high-technology industries. The use of Taiwan’s high-technology industries in the research sample will enable the results of the relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance to provide important meanings for international high-technology industries. 1.5 Research framework

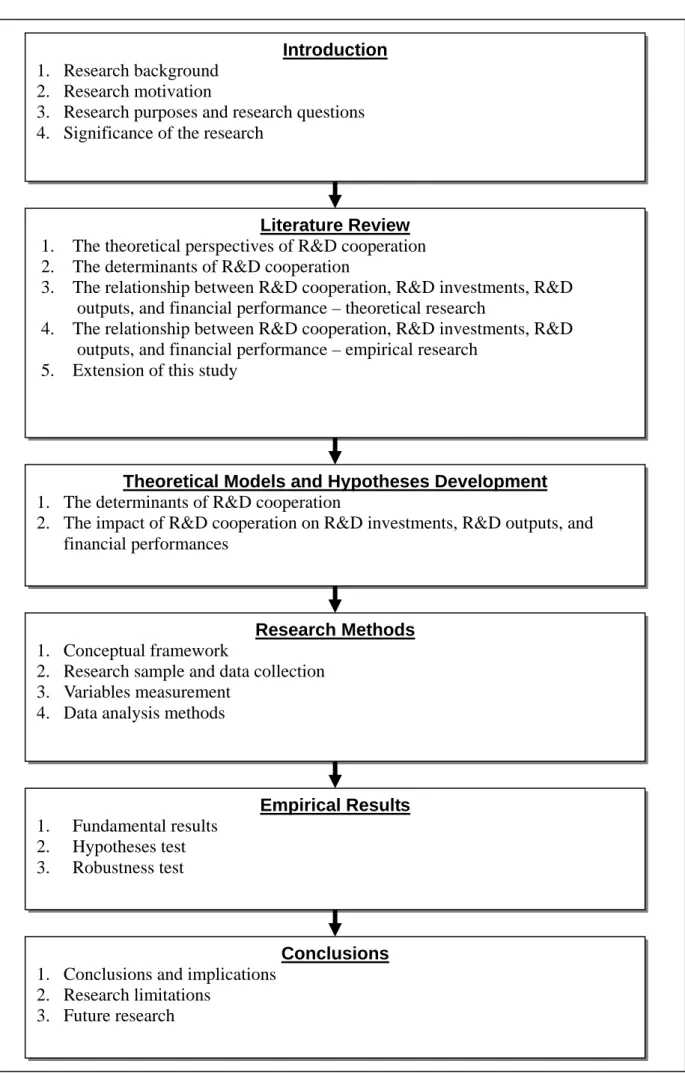

This study is divided into six parts. See Figure 1.

1. Introduction: The first section explains the research background, research motivation, research purpose, research questions, and contributions.

2. Literature review: This section reviews theoretical and empirical findings related to R&D cooperation. First of all, I discuss the definitions, the classifications, the benefits, and the theoretical perspectives of R&D cooperation. Second, I review the related papers of the determinants of participating in R&D cooperation. Third, I present the theoretical research and empirical research related to R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance. I will further discuss the extension of this paper.

3. Theoretical model and hypotheses development: I discuss the hypotheses related to the factors that influence the intensity of R&D cooperation. I then apply Cournot-Nash equilibrium theory to derive the hypotheses regarding the impact of different types of R&D cooperation on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance.

4. Research method: This section describes the conceptual framework, research sample, variables measurement, and data analysis methods.

5. Empirical results: I discuss the findings of the factors of engaging in R&D cooperation. I also examine the results of the relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance.

6. Conclusions: I conclude by reviewing the research findings, and by discussing the implications of this research for academia and practice, the research limitations, and future research.

Figure 1: Research framework of this study Introduction

1. Research background 2. Research motivation

3. Research purposes and research questions 4. Significance of the research

Literature Review 1. The theoretical perspectives of R&D cooperation 2. The determinants of R&D cooperation

3. The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance – theoretical research

4. The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance – empirical research

5. Extension of this study

Research Methods 1. Conceptual framework

2. Research sample and data collection 3. Variables measurement

4. Data analysis methods

Theoretical Models and Hypotheses Development 1. The determinants of R&D cooperation

2. The impact of R&D cooperation on R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performances Empirical Results 1. Fundamental results 2. Hypotheses test 3. Robustness test Conclusions 1. Conclusions and implications

2. Research limitations 3. Future research

Chapter 2: Literature review

This section reviews the literature related to R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance, including: 1. The theoretical perspectives of R&D cooperation; 2. The determinants of R&D cooperation; 3. The relationship among R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-theoretical research; 4. The relationship between R&D cooperation, R&D investments, R&D outputs, and financial performance-empirical research; and 5. Extensions of this study.

2.1 The theoretical perspectives of R&D cooperation 2.1.1 The definitions of R&D cooperation

Given the wide range of R&D cooperation activities, there are different kinds of definitions for R&D cooperation in academia. The synonyms of R&D cooperation used in research include R&D collaboration, research partnership, R&D consortia, R&D joint venture, R&D alliance, R&D strategic alliance, R&D cooperative or collaborative agreement, etc. For examples, research partnership is an innovation-based relationship that involves a significant effort in R&D (Hagedoorn, Link, and Vonortas 2000). R&D agreement is an agreement that regulates R&D sharing and/or transferring between two or more parent companies (Harabi 1998). Siegel (2003) defines strategic research partnership as a cooperative relationship involving organizations that conduct or sponsor R&D, in which there is a two-directional flow of knowledge between the partners. According to Teece (1992), R&D strategic alliance is an agreement characterized by the commitment of two or more firms to reach R&D goals entailing the pooling of their resources and activities. According to prior researchers’ viewpoints, I define R&D cooperation as a cooperative relationship involving two or more organizations that pool their resources and activities to reach an R&D goal. I summarize different definitions of R&D cooperation by prior researchers as follows:

Table 1: The definitions of R&D cooperation

The synonyms of R&D cooperation

Definition Author (year)

R&D

Collaboration

The process of working together with competitors for R&D.

Gibson and Rogers (1994)

Cooperative arrangements engaging companies, universities, and government agencies and laboratories in various

combinations to pool resources in pursuit of a shared R&D objective.

Council on

Competitiveness (1996) Research

partnership

An innovation-based relationship that involves a significant effort in R&D.

Hagedoorn et al. (2000)

R&D partnership The specific set of different modes of inter-firm collaboration where two or more firms that remain independent economic agents and organizations share some of their R&D activities.

Hagedoorn (2002)

R&D consortia R&D consortia are self-governing, usually nonprofit organizations run for the benefit of their members. The owners are the customers, and their purpose is to develop new

technology and put it into practice.

Corey (1997)

R&D joint venture

R&D joint ventures are operations whereby a legally independent and autonomously managed business enterprise is set up by two or more parent companies to run a clearly defined set of R&D activities in the common interest of the founding firms.

Harabi (1998)

R&D agreements R&D agreements cover agreements that regulate R&D sharing and/or transfer between

Cooperative agreements

Common interests between industrial partners that are not connected through ownership.

Hagedoorn et al. (2000)

Strategic research partnerships are primarily entered into by high-technology alliance members to exercise an ‘option’ to acquire first mover advantage resulting from the emergence of a potential dominant design technology or process innovation.

Hemphill and Vonortas (2003)

Strategic research partnership

A cooperative relationship involving

organizations that conduct or sponsor R&D, in which there is a two-directional flow of knowledge between the partners. The implication is that there is a mutually beneficial transfer of knowledge that, in theory, enables all of the partners to achieve a strategic objective.

Siegel (2003)

Agreements characterized by the commitment of two or more firms to reach R&D goals entailing the pooling of their resources and activities.

Teece (1992) R&D strategic

alliance

Strategic alliances embrace a diversity of collaborative forms. The activities covered include supplier-buyer partnerships, outsourcing agreements, technical

collaboration, joint research projects, shared new product development, shared

manufacturing arrangements, common distribution agreements, cross-selling arrangements, and franchising.

Grant and Baden-Fuller (2004)

2.1.2 The classification of R&D cooperation

R&D cooperation can come from either the public sector (e.g. universities and government agencies) or the private sector (e.g. companies). R&D cooperation can also be formal, as expressed in an official pact between the two units detailing the scope and nature of the cooperation; or informal, in which one individual exchanges information with another individual over a period of time without any written or official authorization to do so (Gibson and Rogers. 1994; Hagedoorn et al. 2000). R&D cooperation is an example of formal cooperation. However, very little is known about informal R&D cooperation. The classification of R&D cooperation can also be described as nonexclusive, exclusive, or closed. Nonexclusive cooperation tends to focus on technology for both collective and selective8 products used by a broad membership. Exclusive cooperation also pursues selective technology, but it is organized to advance the interests of some specific group. Closed cooperation seeks to develop proprietary technology, often to enhance members’ market shares in inter-firm and or international competition. Unlike the products of nonexclusive and exclusive cooperation, the more widely proprietary technology is shared, the less its value to any individual cooperative partner (Corey 1997).

Finally, some R&D cooperation is structured horizontally to include firms at only one level of the industry (e.g. competitors). Others are organized vertically to bring together firms at different levels such as suppliers or customers. For example, IC design industry emphasizes system on chip (SOC). SOC is an idea of integrating all components of a computer or other electronic system into a single integrated circuit (chip). However, a single company cannot own all the techniques in the system, so it has to obtain techniques or complete a product together through cooperation with its competitors. Opposite to IC design industry, system assembling companies pay more attention to vertical cooperation. For example, notebook OEM companies, such as Quanta and Compal, emphasize cooperation between suppliers and customers. They

8

Collective products, such as technology for improving the quality of the environment or the development of an industry supply infrastructure, are available to all, consortia members and nonmembers alike. Selective products are R&D achievements made available to individual member firms for such purposes as advancing operations technology, training personnel, and developing new products; their benefits are not easily accessible to nonmembers. Proprietary technology is intended to be appropriable by member only, and is usually undertaken to gain some margin of competitive

have to cooperate with upstream computer component suppliers to insure the specification and yield rate of the components, and rely on the upstream computer component suppliers’ help to complete system design. Upstream firms also cooperate with downstream firms on R&D in order to establish a closed production relationship with downstream customers.9

In this paper, I focus on the influence of horizontal and vertical R&D cooperation, and only include formal cooperation in the private sector. Most of my research samples engage in closed cooperation, but still have some cases of open cooperation. Table 2 summarizes the different classifications of R&D cooperation.

Table 2: The classifications of R&D cooperation

Classifications Description 1. Public vs. private sector

cooperation

R&D cooperation can come from either the public sector (e.g. universities and government agencies) or the private sector (e.g. companies).

2. Formal vs. informal cooperation

R&D cooperation can also be formal, as expressed in an official pact between the two units detailing the scope and nature of the cooperation; or informal, in which one individual exchanges information with another individual over a period of time without any written or official authorization to do so.

3. Open vs. closed cooperation

Nonexclusive cooperation tends to focus on technology for both collective and selective products used by a broad membership. Exclusive cooperation also pursues selective technology, but it is organized to advance the interests of some specific group. Closed cooperation seeks to develop proprietary technology, often to enhance members’ market shares in inter-firm and international competition.

4. Horizontal vs. vertical cooperation

R&D cooperation can be structured horizontally to include firms at only one level of the industry (e.g. competitors). Others are organized vertically to bring together firms at different levels such as suppliers or customers. In addition, generalized cooperation (cooperating with supplier, customer, and competitors simultaneously) is also a widespread form of R&D cooperation.

2.1.3 The benefits of R&D cooperation

The economic reason for the formation of R&D cooperation is the anticipation of a greater benefit through R&D partners than any benefit arising if the partners were to undertake the same activities independently, that is, cost-benefit analyses (Corey 1997). Several types of potential benefits of R&D cooperation can be identified as follows. First, the cost of R&D continues to escalate, taking it beyond the point at which any one company could afford the requisite R&D investment. Therefore, cost sharing opportunities are prime motivators in the formation of consortia for the development of collective and selective R&D products in noncompetitive domains (Corey 1997). Learning from failures is also offered as a benefit of R&D consortia. If ten companies invest in a risky technology and it fails, then each company learns what not to do at one-tenth the cost (Gibson and Rogers 1994). Second, sharing complementary technical knowledge is often the purpose of consortia that are formed to develop proprietary technology to advance competitive advantage (Corey 1997). Third, risk reduction opportunities provide an incentive for collaboration on large-scale projects with a relatively high degree of uncertainty. In addition, risk reduction can provide the opportunity to monitor technological advances in competitors’ R&D activities (Corey 1997). Fourth, synergy allows an R&D consortium with many researchers and resources to enjoy certain benefits that each of its member firms acting alone could not achieve (Gibson and Rogers 1994). By using coalitions, a firm can benefit from a broader scope of activities without spending precious resources to enter new market segments (Porter 1986). Choi (1993) also indicates that the benefits of research joint venture are as follows: pooling of risk and financial resources under market imperfections in capital market, complementary

coordination of research technology choices, etc. Table 3 summarizes the benefits of R&D cooperation.

Table 3: The benefits of R&D cooperation

Benefits Author (year)

Cost sharing opportunities are prime motivators in the formation of consortia for the

development of collective and selective R&D products in noncompetitive domains.

Corey (1997)

Benefits to MCC (Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation) included improved financing and access to low-cost manufacturing.

Gibson and Rogers (1994)

1. Cost sharing

Learning from failures is also offered as a benefit of R&D consortia. If ten companies invest in a risky technology and it fails, then each company learns what not to do at one-tenth the cost.

Gibson and Rogers (1994)

When companies share information completely the R&D process can be divided up into small bits so that the cost of duplicating fruitful and fruitless approaches is avoided.

Kamien, Muller, and Zang (1992). 2. Avoiding

duplication R&D

Avoiding duplication of effort. Scotchmer (2005) Technology know-how for joint technology

development.

Gibson and Rogers (1994)

Sharing complementary technical knowledge is often the purpose of consortia that are formed to develop proprietary technology to advance competitive advantage.

Corey (1997) 3. Sharing

complementary technology

Sharing technical information that might be hidden if firms compete.

Risk reduction opportunities provide an incentive for collaboration on large-scale projects with a relatively high degree of uncertainty.

Corey (1997)

Risk reduction can provide the opportunity to monitor technological advances in competitors’ R&D activities.

Corey (1997) 4. Risk reduction

A firm may decide to enter into a technology alliance that has significant technological or market uncertainties attached to it.

Hemphill and Vonortas (2003)

Coordination of research technology choices. Choi (1993) Synergy allows an R&D consortium with many

researchers and resources to enjoy certain benefits that each of its member firms acting alone could not achieve.

Gibson and Rogers (1994)

5. Synergy

Delegating effort to the more efficient firms. Scotchmer (2005) 2.1.4 Theoretical perspectives on R&D cooperation

There is a vast literature that attempts to explain, from a theoretical perspective, why firms engage in R&D cooperation and what are the results of such cooperation to the partners, industry, and society, respectively. Hagedoorn et al. (2000) distinguish three theoretical perspectives on R&D cooperation: transaction costs, strategic management, and industrial organization theory. First, transaction cost theory is used to explain why an R&D cooperation is formed. One must determine why participating organizations have a cost advantage over the market or a hierarchical organization form of operation for R&D activity (Hagedoorn et al. 2000). Technological transactions in the marketplace can have high transaction costs. Internal R&D limits these costs, but blocks the access to specialized resources in other firms. Through R&D cooperation, firms can get access to these specialized resources, while at the same time allowing for the transfer of technology and knowledge at lower transaction costs (Oerlemans and Meeus 2001).

Second, strategic management scholars use five approaches to discuss strategic technical alliances as below:

1. Competitive force: Cooperation is seen as a means of shaping competition by improving a firm’s comparative competitive position. By using coalitions, a firm can react swiftly to market needs and bring technology to the marketplace faster (Porter 1986).

2. Strategic network: The network is a new form of organization and strategy. Multiple cooperative relationships of a firm can be the source of its competitive strength. Strategic networks can achieve efficiency, synergy, and power (Hagedoorn et al. 2000).

3. Resource-Based View: The resources of sustained competitive advantage are firm resources that are valuable, rare, and not easily substitutable. Access to external complementary resources may be necessary in order to fully exploit the existing resources and develop sustained competitive advantages (Teece 1986). Alliances, including R&D cooperation, can facilitate access.

4. Dynamic capabilities: Dynamic capabilities are defined as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competence to address rapidly changing environments (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen 1997). Inter-firm cooperation can be viewed as a vehicle for organizational learning (Hamel and Prahalad 1989; Mody 1993) and for entering new technological areas (Dodgson 1991).

5. Strategic options to new technologies: This approach to explaining cooperation complements the dynamic capabilities approach by considering how managers can determine prospectively the set of resources and capabilities necessary for superior future performance in uncertain market environments (Sanchez 1993). Cooperation may assist companies to gain valuable experience and increase their exposure to related markets and their ability to sense and respond to new opportunities (Kogut 1991).

models can essentially be categorized into two categories: non-tournament models and tournament models:

1. Non-tournament models: The vast majority of the theoretical work on cooperative R&D has followed the non-tournament approach (e.g. D’Aspremont and Jacquemin 1988; Kamien et al. 1992; Atallah 2002; Ishii 2004). The literature is replete with strategic, static, multistage models comparing the performance of cooperative and non-cooperative industrial setups in the presence of imperfectly appropriable, cost-reducing R&D. A consistent finding is that R&D competition seems better in the absence of knowledge spillovers, while R&D cooperation performs consistently better under the higher rate of knowledge spillovers. The mathematical modeling of this study follows non-tournament approach.

2. Tournament models: Tournaments models emphasize the timing of innovation where the winner of an innovative race (often takes the forms of a patent race) earns the right to an exogenously or endogenously determined monopolistic return. The winner shares the available information with the loser means that partnership will not form unless it is subsidized. In addition, firms choose to cooperate fully when they undertake complementary R&D, while they share no information outside the partnership if they undertake substitutive R&D.

I summarize the theoretical perspectives on R&D cooperation as Table 4: Table 4: Theoretical perspectives on R&D cooperation

Theory Categories

1. Transaction cost: Why participating organizations have a cost advantage over the market or a

hierarchical organization form of operation for R&D activity.

Through R&D cooperation, firms can get access to the specialized resources of other firms, while at the same time allowing for the transfer of technology and knowledge at lower transaction costs than transactions through the market place (Oerlemans and Meeus 2001).

1. Competitive force: Cooperation is seen as a means of shaping competition by improving a firm’s comparative competitive position. By using coalitions, a firm can react swiftly to market needs and bring technology to the marketplace faster (Porter 1986).

2. Strategic network: Multiple cooperative relationships of a firm can be the source of its competitive strength. Strategic networks can achieve efficiency, synergy, and power (Hagedoorn et al 2000).

3. Resource-Based View: The resources of sustained competitive advantage are firm resources that are valuable, rare, and not easily substitutable. Access to external complementary

resources may be necessary in order to fully exploit the existing resources and develop sustained competitive advantages (Teece 1986). Alliances, including R&D cooperation, can facilitate access.

4. Dynamic capabilities: The primary focus is on the mechanisms by which firms accumulate and deploy new skills and

capabilities, and on the contextual factors that influence the rate and direction of this process. Inter-firm cooperation can be viewed as a vehicle for organizational learning (Hamel and Prahalad 1989; Mody 1993) and for entering new technological areas (Dodgson 1991).

2. Strategic management scholars: Five approaches are used to discuss

strategic technical alliances.

5. Strategic options to new technologies: This approach to explaining cooperation complements the dynamic capabilities approach by considering how managers can determine

prospectively the set of resources and capabilities necessary for superior future performance in uncertain market

environments (Sanchez 1993). Cooperation may assist companies to gain valuable experience and increase their exposure to related markets and their ability to sense and

1. Non-tournament models: The vast majority of the theoretical work on cooperative R&D has followed the non-tournament approach. Strategic, static, multistage models comparing the performance of cooperative and non-cooperative industrial setups in the presence of imperfectly appropriable,

cost-reducing R&D are abundant in the literature. A consistent finding is that R&D competition seems better in the absence of knowledge spillovers, while R&D cooperation performs consistently better under the higher rate of knowledge spillovers. The mathematical modeling of this study follows non-tournament approach.

3. Industrial organization: Recent theoretical literature has depended heavily on game-theoretic tools and formal

mathematical modeling.

2. Tournament models: Tournaments models emphasize the timing of innovation where the winner of an innovative race earns the right to an exogenously or endogenously determined

monopolistic return. The winner shares the available

information with the loser means that partnership will not form unless it is subsidized. In addition, firms choose to cooperate fully when they undertake complementary R&D, while they share no information outside the partnership if they undertake substitutive R&D.

2.2 The determinants of R&D cooperation

Ample empirical research and examples exist covering the incentives of engaging in R&D cooperation. Using Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation as a case, Gibson and Rogers (1994) summarize the motivations to form R&D consortia, including the following: efficiencies of shared cost and risk, exploration of new concepts, pooling scarce talent, sharing research or manufacturing facilities, desire for research synergy, diversification of a technology portfolio, developing frameworks into which other technology modules or tools can fit, setting standards, marketing products, pre-competitive sharing of research results, industrial organization and accelerated technology development, big science and large projects, infrastructure development, and facilitating technology transfer or partnering, whether domestic or foreign. Using a database of European research joint ventures (RJVs),

Hernan, Marin, and Siotis (2003) find that R&D intensity, industry concentration, firm size, technological spillovers, and post-RJV participation all positively influence the probability of forming RJVs. Belderbos, Carree, Diederen, Lokshin, and Veugelers (2004) explore the determinants of innovating firms’ decisions to engage in R&D cooperation. They observe that the determinants of R&D cooperation differ significantly across cooperation types. The positive impacts of firm size, R&D intensity, and incoming spillovers are weaker for competitor cooperation. Based on German manufacturing enterprises, Fritsch and Lukas (2001) analyze the propensity to maintain different forms of R&D cooperation with customers, suppliers, competitors and public research institutions. According to their results, enterprises that maintain R&D cooperation relationships tend to be relatively large and have a high share of R&D.

R&D cooperation can be considered to restore private incentives, because of internalizing the knowledge spillovers between cooperating firms (e.g. D’Aspremont and Jacquemin 1988; Kamien et al. 1992; Ishii 2004). Peters and Beck (1997-98) analyze the role of knowledge spillovers between automakers and suppliers in vertical corporate networks, both theoretically and empirically. In the empirical results they find evidence for the importance and effects of the transfer of technological information between manufacturers and their suppliers in the R&D process to develop and produce a custom-tailored good. Cassiman and Veugelers (2002) empirically explore the effects of knowledge flows on R&D cooperation. They discover that there is a significant relation between external information flows and the decision to cooperate in R&D. Firms that generally rate available external information sources as more important inputs to their innovation process are more likely to be actively engaged in cooperative R&D agreements. At the same time, firms that are more effective in appropriating the results from their innovation process are also more likely to cooperate in R&D. Kaiser (2002a) uses innovation survey data from the German service sector to explore research expenditures and research cooperation. The main results show that RJVs are more widespread among vertically-related firms than among horizontally-related firms. An increase in horizontal spillovers tends to increase incentives to collaborate in R&D. In addition, R&D efforts are larger under RJV than under R&D competition with a sufficiently large spillover. Sakakibara and Dodgson (2003) evaluate the role that strategic research partnerships (SRPs) play in

Asia and conclude that SRPs are formed to facilitate technological diffusion in Taiwan. Milliou (2004) analyzes the impact of R&D information flow on the incentives of innovation and social welfare under vertical integration. His results show that R&D information flow has a positive impact on innovation, outputs, and profits for R&D-integrated firms, but a negative impact for the R&D non-integrated firm.

Absorptive capacity and uncertainty10 are also deemed as crucial factors that influence the decision of R&D cooperation. Bayona, Garcia-Marco, and Huerta (2001) test firms’ motivations for cooperative R&D using Spanish firms that carried out R&D activities. The results obtained therein suggest that firms’ motivations for cooperative R&D include technology’s complexity and the fact that innovation is costly and uncertain. To undertake cooperative R&D, it is necessary to have certain internal capacities in this area. Becker and Dietz (2004) investigate the role of R&D cooperation in the innovation process. The results suggest that joint R&D is used to complement internal resources in the innovation process, enhancing the innovation input and output. The intensity of in-house R&D (absorptive capacity) also significantly stimulates the probability and the number of joint R&D activities with other firms and institutions. Caloghirou et al. (2003) investigate partnership performance and find that partnership success depends on the closeness of the cooperative research to the in-house R&D efforts of the firm, as well as on the firm’s effort to learn from the partnership and its partners. Sakakibara (2002) investigates economic and strategic incentives of R&D cooperation. She finds that a firm’s R&D capabilities, network formation through past consortia, encounters with other firms in the product market, age, and past participation in large scale consortia also positively affect its tendency toward consortia formation. Corey (1997) indicates that the risk-reduction opportunities provide an incentive for collaboration on large-scale projects with a relatively high degree of uncertainty. Another form of risk reduction that a collaborative venture provides is the opportunity to monitor technological advances in competitors’ R&D programs. Caloghirou et al. (2003) also find that firms use partnerships as vehicles of risk and uncertain reduction by collaborating with competitors as well as with suppliers and buyers.

Mathews and Cho (2000) indicate the importance of collaborative research

relationships for the development of the industry in Taiwan. However, very little research has focused on R&D cooperation activity because of data availability. In this study I provide a comprehensive analysis of R&D cooperation within Taiwan’s high-technology industries. Furthermore, a common feature in the prior R&D cooperation literature is the absence of uncertainty. Therefore, in addition to the factors used in Sakakibara’s research, I discuss the relationship between uncertainty and R&D cooperation.

Table 5: Literature summary of the determinants of R&D cooperation

Author/Year Research topic Research method Research conclusion and research implication

Atallah (2002) Author studies vertical R&D spillovers between upstream and downstream firms.

1. Analytical research. 2. The model includes two vertically related industries, with horizontal spillovers within each industry and vertical spillovers between the two industries.

Research conclusion:

Author finds that vertical spillovers affect R&D investments directly and indirectly through their influence on the impact of horizontal spillovers and R&D cooperation. In addition, no matter what type the cooperation is, vertical spillovers always increase R&D efforts and welfare.

Research implication:

Based on the two vertical industry model, Atallah (2002) includes four R&D scenarios: R&D competition, vertical R&D cooperation, horizontal R&D cooperation, and

generalized R&D cooperation. In this study I adopt his R&D cooperation scenarios in my theoretical model.

Cassiman and Veugelers (2002)

Authors empirically explore the effects of knowledge flows

1. Empirical research. 2. The data are drawn from the Community

Research conclusion:

They discover that there is a significant relation between external information flows and the decision to cooperate in

Author/Year Research topic Research method Research conclusion and research implication (knowledge spillovers) on R&D cooperation. Innovation Survey (CIS) conducted in Belgian manufacturing firms in 1993.

R&D. Firms that generally rate available external information sources as more important inputs to their innovation process are more likely to be actively engaged in cooperative R&D agreements. At the same time, firms that are more effective in appropriating the results from their innovation process are also more likely to cooperate in R&D.

Research implication:

Authors use survey data to explore the effects of knowledge flows on R&D cooperation and suggest that incoming

spillovers and appropriability have important effects on R&D cooperation. In this study I will use archival data to test the determinants of R&D cooperation.

Kaiser (2002a) Author uses innovation survey data from the German service sector to explore research

expenditures and research

1. Empirical research. 2. The empirical

analysis is based on the survey data of the Mannheim

Research conclusion:

The main results show that RJVs are more widespread among vertically-related than horizontally-related firms. An increase in horizontal spillovers tends to increase incentives to