國際公司改名對股票市場和借款成本的影響 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………………...iii List of Tables………………………………………………………………………….iv Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………… vi Abstract………………………………………………………………………………vii Chapter Ⅰ. Introduction……………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter Ⅱ.The Wealth Effects of Oil-related Name Changes on Stock Prices: Evidence from the U.S. and Canadian Stock Markets 1. Introduction………………………………………………………..... 7 2. Literature review and hypotheses of corporate name changes…….. 10 3. Data and Methodology…………………………………………….. 14 3.1 Data description ……………………………………………….. 14 3.2 Methodology…………………………………………………... 18 4. Empirical results…………………………………………………… 20 4.1 Wealth effects of corporate name changes involving oil-related terms…………………………………………………………… 20 4.1.1 Addition versus deletion of oil-related terms…………….. 23 4.1.2 Major versus minor name changes……………………….. 25 4.1.3 Oil-related sectors versus oil-unrelated sectors…………... 26 4.2 Cross-sectional Regression Analysis…………………………... 27 4.2.1 The Cross-sectional Regression Analysis of CAR………...27 4.2.2 The Cross-sectional Regression Analysis of Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR)…………………………………………….. 29 5. Conclusions………………………………………………………... 30 Chapter Ⅲ. The Cost to Firms of Changing the Names: Evidence from the Bank. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Loan Market 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 50 2. The effect of name change and loan contracting literature……..…. 54 3. Data………………………………………………………………... 59 3.1 Sample description…………………………………………….. 59 3.2 Univariate analysis…………………………………………….. 60 4. Multivariate analysis………………………………………………. 62 4.1 The effect of corporate name changes on the cost of loan contracting .…………………………………………………………62 4.1.1 The effect on the cost of loan contract among different types of corporate name changes………………………………66 i .

(3) 4.1.2 Wealth effect versus information effect of name change... 68 4.1.3 The effect of positive CAR corporate name change on the cost of loan contract……………………………………...70 4.2 Effect of corporate name change on non-price loan contract terms and loan structure……………………………………………... 71 4.2.1 Loan maturity…………………………………………… 72 4.2.2 Loan collateralization…………………………………... 73 4.2.3 Covenants restriction…………………………………… 74 4.2.4 Number of lenders……………………………………… 76 5. Robustness Checks………………………………………………….77 5.1 Unobservable firm characteristics…………………………77 5.2 Unobservable macroeconomic or industry shock…………77 5.3 Endogeneity of loan maturity …..…………………………78 5.4 Robustness to outliers ……………………………………..79 5.5 Empirical analysis at deal level …………………………80 6. Conclusions………………………………………………………... 81 Chapter Ⅳ. Conclusion and Future Studies .....……………………………………105. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Appendix A …………………………………………………………………………109 References ………………………………………………………………………….112. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. ii .

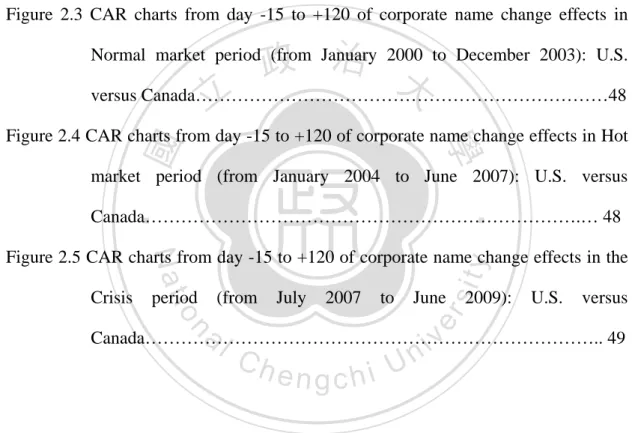

(4) List of Figures Figure 2.1 Oil price trend and changes of corporate names with additions and deletions of oil from their names in the U.S. and Canadian markets (from January 2000 to June 2009)……………………………………………. 47 Figure 2.2 CAR charts from day -15 to +120 of corporate name change effects in combined sample (from January 2000 to June 2009): U.S. versus Canada………………………………………………………………….. 47 Figure 2.3 CAR charts from day -15 to +120 of corporate name change effects in. 政 治 大 versus Canada……………………………………………………………48 立. Normal market period (from January 2000 to December 2003): U.S.. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 2.4 CAR charts from day -15 to +120 of corporate name change effects in Hot market period (from January 2004 to June 2007): U.S. versus. ‧. Canada……………………………………………………………….… 48. Nat. 2007. n. al. July. to. sit. (from. June. 2009):. U.S.. versus. er. period. io. Crisis. y. Figure 2.5 CAR charts from day -15 to +120 of corporate name change effects in the. i Un. v. Canada………………………………………………………………….. 49. Ch. engchi. iii .

(5) List of Tables Table 2.1 Data Description…………………………………………………………. 33 Table 2.2 Occurrences and Characteristics of Name Changes……………………... 34 Table 2.3 Analysis of CARs for the combined sample and three sub-samples ..…… 35 Table 2.4 Analysis of CARs of subcategory 1: additions versus deletions of “oil” terms……………………………………………………………………… 37 Table 2.5 Analysis of CARs of subcategory 2: major versus minor name changes… 39 Table 2.6 Analysis of CARs of subcategory 3: oil-related versus oil-unrelated. 政 治 大 Table 2.7 Cross-sectional regressions of CAR on the event day……………………. 43 立 firms……………………………………………………………………… 41. ‧ 國. 學. Table 2.8 Cross-sectional regressions of CAR (-15, +60)……………………………… 44 Table 2.9 Cross-sectional regressions of CAR (-15, +120) …………………………….. 45. ‧. Table 2.10 Cross-sectional regressions of BHR ………………………...………….. 46. Nat. sit. y. Table 3.1 Description of the sample………………………………………………… 83. n. al. er. io. Table 3.2 Summary statistics of loan contract terms for name change firms……….. 84. i Un. v. Table 3.3 Effect of name change on the cost of bank debt………………………….. 85. Ch. engchi. Table 3.4 Effect of name change on the cost of bank debt among different types….. 87 Table 3.5 Wealth effect versus information effect of name change on the cost of loan……………………………………………………………………….. 89 Table 3.6 Positive CAR effect of name changes on the cost of loan contract………. 91 Table 3.7 The effect of name change on loan maturity …………………………….. 93 Table 3.8 The effect of name change on loan collateralization……………………... 95 Table 3.9 The effect of name change on general covenants restriction……………... 98 Table 3.10 The effect of name change on number of lenders ………………………..99 Table 3.11 Robustness Checkness ..……………………………………………….. 101 iv .

(6) Table 3.12 Deal-level analysis of non-price loan contract terms………..………… 103. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. v .

(7) Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible unless the support, encouragement and assistance of my advisor, professors, friends and family during these four years. Hence, I would like to show my sincerely gratitude to. Professor Yuanchen Chang–My advisor. His invaluable guidance, patient advice, unconditional support and encouragement helped me in all the time of research and writing of this dissertation.. 政 治 大 teachers during my doctor career. As their research assistant, I learned from their 立 Professors Edward H. Chow, Jie-Haun Lee, Yu-Jane Liu, and Yi-Tsung Lee–My. ‧ 國. 學. enthusiasm for research and professional research skills.. Professors Chiuling Lu, Shikuan Chen, ShihChieh Chang and Chenghsien Tsai–The. ‧. member of my dissertation committee. Their valuable comments and precious. Nat. sit. y. suggestion that improve the quality of my dissertation and make it more complete.. n. al. er. io. Wei-Shao Wu, Shu-Hua Liu, and Yumei Hsu–My fellows. We experienced joy,. i Un. v. depression and delicious food together. They gave me useful suggestions when I. Ch. engchi. encountered difficulty. They color my doctor career.. Daniel Yang–My dear fiancé. He always supports the decision I make and accompanies me to face with the happiness and hardness in my life. David Lin, Esther Huang and Sean Lin–My parents and brother. Their unreserved love and support encourage me to accomplish my doctor degree. Hsiao-Mei Lin June 14, 2011. vi .

(8) Abstract Two essays are comprised in this dissertation to examine the benefits and costs of corporate name changes. The empirical investigation on corporate name changes in stock market and loan market provide the entirely different insights on the effect of corporate name changes. With the recent oil price in surge and then crash, I have the opportunity to examine whether firms have the incentives to changes their names when oil price surge. In the first essay, I examine the wealth effect of corporate name changes. 政 治 大 et al. (2005), I argue that firms tend to change their name by adding the words “oil” or 立 involving oil-related terms. Following Cooper, Dimitrov and Rau (2001) and Cooper. ‧ 國. 學. “petroleum” to names when oil price in surge, while deleting the words “oil” or “petroleum” to names when oil price in a crash. I also compare the effect of corporate. ‧. name changes between U.S. and Canadian stock market. Consistent with the. Nat. sit. y. prediction, I provide the evidence that there exists valuation effect of corporate name. n. al. er. io. changes involving oil-related terms in U.S. stock market when the recent oil price. i Un. v. surge. When financial crisis exploded U.S. stock market reacts significant negatively. Ch. engchi. to corporate name changes. This is perhaps because investors expect economic difficulty caused by the financial crisis, which in turn, would hurt the oil industry and high oil price is not expected to be sustainable. On the contrary, relative to U.S. market, Canadian stock market has little reaction on the corporate name changes regardless of the type of name changes or market condition. This opposite results can be attributed to the different economic structure between U.S. and Canadian market. In the second essay, I focus on the effect of corporate name changes from the perspective of bank loan holders. I examine the cost of corporate name changes in the loan contracting. A corporate name changes creates information asymmetry and vii .

(9) uncertainty about the future cash flow of a firms. To reduce the increase of credit risk, bank loan holders would attempt to enhance the efficient monitoring by tighter contracting terms and more concentrated lending structure. Consistent with this argument, the empirical results show that loan after name changes have significantly higher loan spread, higher probability of being secured, more general covenant restrictions and fewer lenders participate in a syndicated loan. Following Wu (2010), I categorize corporate name changes into different types of name changes and examine whether there is different effect among different types of name changes. I find that firms experiencing radical name changes are more likely. 治 政 to bear more financing costs. Lastly, I provide the evidence 大 that firms pay higher 立 borrowing costs when investors experience a significantly positive reaction from ‧ 國. 學. stock market through cosmetic name changes, which illustrate the importance of. ‧. banks playing the role of monitoring and controlling borrowers.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. viii .

(10) Chapter Ⅰ Introduction Corporate name changes have been common in practice in recent years. From 1930 to 2009, more than 35% of the firms in the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) database changed their corporate names.1 For instance, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Esso) changed to Exxon in 1972, Consolidated Foods to Sara Lee in 1985, International Harvester to Navistar International in 1986, UAL became Allegis. 政 治 大 Time Warner and AOL to AOL Time Warner in 2001 and then changing to Time 立. in 1987 and changed back to UAL Corp. in 1988, Dayton-Hudson to Target in 2000,. ‧ 國. 學. Warner in 2003, Andersen Consulting to Accenture in 2001, Benton Oil & Gas Co. to Harvest Natural Resource in 2002, KPMG Consulting to BearingPoint in 2002,. ‧. PriceWaterhouseCoopers Consulting (PWC) to Monday in 2002 and quickly changing. Nat. sit. y. back to PWC in the same year, Tesoro Petroleum Corp to Tesoro Corporation in 2004,. n. al. er. io. Apple Computer to Apple in 2007.. i Un. v. Corporate name changes can be a costly corporate behavior. The direct and. Ch. engchi. indirect cost come from a loss of goodwill or public recognition, confusion to customers, advertising costs, legal fees, printing of new stationery, business cards, signage, packaging and redesigning new logos, which all can amount to hundreds of millions of dollars (Liu, 2010). For example, the change from Esso to Exxon costs an enormous sum of approximately $200 million (McQuade, 1984); Andersen Consulting changed to Accenture at an reported cost of $100 million (Wu, 2010); PWC spent $110 million for marketing campaigns and corporate-name consultancy . 1. From 1930 to 2009, there are 19,440 listed firms without name changes and 7,220 listed firms that made 9,787 name changes. Among these 7,220 firms, there are 5,353 firms (54.69%) made one change, 1,385 firms (14.15%) made two name changes, and 482 firms (4.92%) made more than two name changes. 1 .

(11) (Treadwell, 2003); KPMG Consulting spent $20 to 35 million to change its name to BearingPoint (Stuart and Muzellac, 2004); International Harvester changed to Navistar at an estimated cost of $13 to 16 million (Bennett 1986), and the change from United Airlines to Allegis at an estimated cost of $7.3 million (Koku, 1997). However, there are some benefits associated with corporate name changes. A firm’s name change can convey the information about the changes of their business lines or communicate private information about future prospects with the public (Spence, 1973; Ferris, 1988; Karpoff and Rankine, 1994). Besides, corporate name changes can benefit firms’ current market position and identification (Horsky and Swyngedouw,. 治 政 1987; Tadelis, 1999; Kilic and Dursun, 2006). 大 立 With the prevalence of corporate name changes in practice, their impact on the ‧ 國. 學. welfare of shareholder has attracted market’s attention. The literature in the welfare. ‧. effects of corporate name changes have developed into two sides. The rational. sit. y. Nat. perspective states that market response to corporate name changes if the corporate. io. al. er. name changes covey the information about the changes in future expected cash flow of a firm. The empirical results in 1980s support the rational perspective. Howe (1982). n. iv n C environmenth with information e n g c h i U asymmetry,. states that under the. firms with good. quality can benefit from name changes to increase their stock prices, but his empirical results show that there is no statistically significant reaction in stock price associated with corporate name changes. Horsky and Swyngedouw (1987) argue that a corporate name change is merely a signal, and there should be statistically insignificant difference between major and minor changes. Besides, Bosch and Hirschey (1989) assert that corporate name changes are usually used to create a brand-new corporate image and conclude that the valuation effects of a corporate name change are only modest and transitory. Karpoff and Rankine (1994) also find that little evidence 2 .

(12) supports the hypothesis that the announcement of corporate name changes result in any reaction in stock price. In contrast, a growing body of literature in the irrational perspective argues that markets are inefficient and that investors in financial market do not behave rationally all the time. Recent empirical evidence using data from the internet bubble period support the irrational perspective. Cooper, Dimitrov and Rau (2001) show an economically significant positive reaction to the changes of internet–related dotcom names from 1998 to 1999 in the U.S. stock market and suggest that this positive valuation effect of corporate name changes remains regardless of the industry firms. 治 政 involve. Cooper et al. (2005a) document that investors 大were deceived by companies 立 seeking to be disassociated from internet industry by deleting “dotcom”, “dotnet” or ‧ 國. 學. “internet” from their corporate name changes during 1998-2001 period. In addition,. ‧. Cooper, Gulen and Rau (2005b), Bae and Wang (2009) and Liu (2010) also provide. sit. y. Nat. empirical evidences to support the irrational perspective and suggest that corporate. io. al. er. name change effects are associated with investor mania driven by a price pressure in. n. the stock market, and managers tend to take advantage of investors sentiment by. ni C h gains. changing corporate names to capture U engchi. v. The first essay of this dissertation aims at investigating the benefit of corporate name changes in equity market. With the recent surges and crash in oil price, I attempt to extend these extant literature and examine whether companies tend to add “oil” or “petroleum” terms to their names during the recent oil surge and whether the wealth effect of corporate name changes exist involving oil-related terms. Following Horsky and Swyngedouw (1987), I classify corporate name changes into three subcategories – addition versus deletion, major versus minor, and oil-related versus oil-unrelated. I examine the effect of corporate name changes associated with the words “oil” or 3 .

(13) “petroleum” on stock price. I also compare the valuation effect of corporate name changes underwent in the U.S. and Canadian stock markets from oil price in surge to financial crisis exploded. My findings show that U.S. investors seem to respond more enthusiastically to name changes involving oil related terms than Canadian investors when oil price surge. However, the positive reaction in U.S. stock market vanished as the recent financial crisis exploded. Increasing volatility and uncertainty eliminate the optimisms generated by surging oil prices. The extant literature and the first essay of this dissertation focus mainly on the valuation effect of corporate name changes from the perspective of shareholders, and. 治 政 suggest that when market booms, managers have an opportunity to take advantage of 大 立 investor sentiment to benefit from stock price if firm value is undervalued. These ‧ 國. 學. results are consistent with Almazan, Banerji, and Motta (2008). They argue that the. ‧. discretionary disclosure of corporate information gives managers an opportunity to. sit. y. Nat. take advantage of investors’ attention when firm is undervalued. Nevertheless, to date,. io. al. er. there is little literature to investigate the cost of debt associated with corporate name changes. A corporate name change implies that the information about reputation,. n. iv n C operation and future prospect of a h firm previous known e n g c h i U might be adjusted; therefore, prior beliefs about the credit risk and information asymmetry need to be revaluated. Modern financial theory suggests that financial institutions play an important role in monitoring their borrowers (Leland and Pyle, 1977; Fama, 1985). Some suggest that loan contract reflect the risk and information asymmetry of borrowers. For instance, Rajan and Winston (1995) show that financial institutions use covenants and collateral to monitor their borrowers.. Freixas and Rochet (2008) suggest that credit risk is a. main determinant of loan pricing and higher lending risk result in higher interest rate. Graham, Li and Qui (2008) show that corporate behavior changes can increase credit 4 .

(14) risk and uncertainty regarding firm’s perceived information asymmetry to lenders; to mitigate this problem, financial intermediaries, which are more informed than investors, can strengthen their monitoring mechanism by increasing loan spreads or requiring more restrictions on the loan contracts after corporate behavior changes. Therefore, the focus in the second essay is not on the impact of corporate name change from the perspective of shareholders, but on the effect of corporate name change from the perspective of debt holders. I explore whether corporate names changes can increase credit risk and uncertainty regarding firm’s perceived information asymmetry to lenders and a cosmetic name change results in borrowers. 治 政 face higher loan spreads or bear more non-price restrictions. 大 Following Wu (2010), I 立 classify the reasons behind corporate name changes into different categories to study ‧ 國. 學. which type of name changes is likely to bear the most increase in financing costs.. ‧. My sufficient findings show that because more information asymmetry and. sit. y. Nat. credit risk driven by corporate name changes negatively affect lenders’ belief in the. io. al. er. expected future cash flows of a firm, bank lenders increase loan spread and strengthen the contract terms after corporate name changes. Moreover, consistent with Wu. n. iv n C (2010), a firm would bear most increase costs when the firm experiences h e ningfinancing chi U a radical name change. These results provide the evidence that lenders like financial intermediaries indeed play an important role in monitoring and controlling borrowers. The reminder of this dissertation is organized as follows. Chapter Ⅱ explores the wealth effects of oil-related name changes on stock prices: evidence from the U.S. and Canadian stock markets. Chapter Ⅲ examine the cost to firms of changing the names. Chapter Ⅳ summarize the results of two studies and conclude the dissertation.. 5 .

(15) Chapter Ⅱ The Wealth Effects of Oil-related Name Changes on Stock Prices: Evidence from the U.S. and Canadian Stock Markets. 1. Introduction The purpose of this chapter is to examine the impact of rising oil prices on corporate name change behavior and its impact on the stock returns. The price of crude oil was stable and under $30 per barrel before 2004, and a series of economic. 政 治 大 surpassed $75 in the summer of 2006 and then rise sharply, reaching $90 per barrel by 立. and political events led the price to reach over $60 per barrel by 2005. The oil price. ‧ 國. 學. the end of 2007 and over $140 per barrel in June 2008. In July 2008 there was a dramatic crash in the oil price and declined to $30 per barrel in December 2008. It is. ‧. of interest to examine if the change of oil price has an impact on the stock markets.. Nat. sit. y. The extant literature focused mainly on the effect of oil price changes on the. n. al. er. io. aggregate stock returns (Kilian and Park, 2007). Kilian and Park (2007) show that the. i Un. v. response of aggregate stock returns may differ depending on whether the increase in. Ch. engchi. the price of crude oil is driven by demand or supply shocks in the crude oil market. They show that negative stock returns are associated with higher oil prices when markets are affected by specific demand shocks that reflect fears about the availability of future oil supplies. In contrast, positive shocks to the global aggregate demand for industrial commodities can cause both higher oil prices and higher stock prices. They also identify the sectors most sensitive to oil market disturbances. To the best of my knowledge, remarkable little empirical research has been conducted on the impact of oil price surge on corporate behavior. I ask the following questions: Do companies tend to add the words “oil” or “petroleum” to their names 7.

(16) during the recent oil price surge? If so, what are the valuation effects of name changes involving oil related terms? This chapter explores the effect of corporate name changes associated with the words “oil” or “petroleum” on stock prices. I also compare valuation effects of corporate name changes underwent in the U.S. and Canadian stock markets from January 2000 to June 2009. The academic literature has found mixed evidence on the valuation effects of corporate name changes. Early evidence found no statistically significant valuation effects associated with corporate name changes (Howe, 1982, Karpoff and Rankine, 1994). However, the dot.com phenomenon provides contrasting results. Lee (2001). 治 政 and Cooper, Dimitrov and Rau (2001) documented 大 significant and positive market 立 reactions to the changes of internet-related dot.com names. Cooper, Dimitrov, and ‧ 國. 學. Rau (2001) suggest that effects of corporate name changes are associated with. ‧. investor mania driven by a price pressure induce-bubble in the stock markets. As the. sit. y. Nat. internet bubble burst, valuation effect of corporate name changes seems remains, but. io. al. er. operates in a reverse direction. Cooper et al. (2005a) found positive market reaction to name changes for firms deleting “dot.com”, “dot.net”, and “internet” from their. n. iv n C names after the internet crash. Theyhconcluded that investors e n g c h i U are affected by cosmetic changes and managers try to take advantage of investor sentiment by changing corporate names. According to the extent literature, I attempt to investigate whether there exists the valuation effect of name changes involving oil related terms or whether there exists the difference when oil prices goes up or comes down. In this study, I examine whether valuation effects of corporate name changes related to the oil industry. My study contributes to the current literature in two ways. Firstly, most previous studies on the effects of corporate name changes examine. 8.

(17) sample of firms from different industries.2 As suggested by Koku (1997), aggregation bias may be resulted by lumping firms form different industries together. Ignoring the industry effects may contaminate empirical results. Koku (1997) examined the impact of name changes with a focus on service industry and found positive reactions to corporate name changes. There is no study examined the market effects of corporate name changes in a single energy industry. I try to fill the gap by examining the effects of corporate name changes in the oil industry. The recent surges in oil price provides me an opportunity to revisit the claim that managers take advantage of investors’ bias by changing corporate names conditional on market condition as reported in Cooper. 治 政 et al.(2005). Secondly, I compare the valuation effects 大of corporate name changes 立 between the U.S. and Canadian stock markets. This is the first study directly ‧ 國. 學. comparing the wealth effects of corporate name changes in the U.S. with another. ‧. market.. sit. y. Nat. Previous studies mainly examined the U.S. market with the exception of Josev,. io. al. er. Chan, Faff (2004), Karbhari, Sori and Mohamad (2004), Andrikopoulos et al. (2007) and Mase (2009). They show conflicting results on the valuation effects of corporate. n. iv n C Australian, and United h e Malaysian ngchi U. name changes for the. Kingdom markets,. respectively. Studies on the valuation effects of corporate name changes in more NonU.S. markets are warrant. Many assume that the Canadian market is basically the same as the US market due to the geographic proximity and cultural or economic integration between the two countries, but this assumption has rarely been examined. Except the study by Sati and Douglas (1994), to the best of my knowledge, I am not aware of any published research that compares market effects between the U.S. and. 2. Lee (2001) controlled for industry effect by including dummy variables in the regression analysis. However, no details of the results are provided. It is not clearly how many different industries are included in the sample and whether the coefficients of the industry dummies are significant or not. Moreover, industry dummy is not likely to mitigate the impact of industry effects completely. 9.

(18) Canadian markets.3 It is of interest to examine if investors in these two markets react to corporate name changes differently. My results provide insight into the difference in investor sentiment between the two markets. The results show that stock price reactions to announcements of name changes involving oil related terms are significantly from zero, and different between U.S. and Canada stock markets. In hot market period, U.S. addition and related name change had significantly positive CAR, which is consistent with previous literature. While in Financial crisis period, U.S. deletion and unrelated name change suffered significantly negative CAR, which can be due to higher uncertainty. 治 政 perceived by investors. I find discrepancies between the 大valuation effects in the U.S. 立 and Canadian markets. The results for the Canadian name changes are less significant ‧ 國. 學. in both periods. U.S. investors seem to respond more enthusiastically to name changes. sit. y. Nat. much slower in the U.S. market than in the Canadian market.. ‧. involving oil related terms than Canadian investors, and the valuation effects dissipate. io. al. er. The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses literature and provides hypotheses of valuation effects for corporate name changes.. n. iv n C Section 3 describes the sample andhthe event study methodology that I use. Section 4 engchi U presents and discusses the empirical results. Section 5 concludes.. 2. Literature review and hypotheses of corporate name changes Because corporate name changes are costly and firm names are related to certain. 3. Previous studies on the U.S. and Canadian markets mainly focus on the issues of integration or segmentation between the two countries. For example, Forester and Karolyi (1995) examined the shortrun cross market dependence in returns and volatility between the U.S. and Canadian markets. Forester and Karolyi (1993) investigated the stock price movement of Canadian firms before and after they inter-listed in the U.S. They found evidences of some degree of segmentation between the two markets. Forester and Karolyi (1998) examined the impact on trading costs of the decision to inter-listed on a U.S. exchange. Sati and Douglas (1994) examined the capital market effects of U.S.-Canada GAAP differences. 10.

(19) qualities of firm performance, it is naturally to ask why do firms change their names. Howe (1982) argued that information asymmetries can explain why valuation effects of company name changes exist. He showed that in situation of quality uncertainty, high quality firms can benefit from name changes to their stock prices. He used event study methods to assess name change effects from 1962 to 1980 and concluded that no statistically significant valuation effect in the U.S. Bosch and Hirschey (1989) were the first to separately examined announcements of major and minor name changes. They report that from 1981 to 1985 firms experiencing major name changes have significant excess return for the ten days prior to announcement date, while. 治 政 minor-name-change firms do not. They also show that 大these two types of corporate 立 name changes have post-announcement performance. They concluded that the ‧ 國. 學. valuation effects of corporate name changes are only modest and transitory. Karpoff. sit. y. Nat. found statistically insignificant stock price effects.. ‧. and Rankine (1994) examined U.S. corporate name changes from 1979 to 1987 and. io. al. er. Recent empirical evidence using data from the internet bubble period shows different results. Cooper, Dimitrov, and Rau (2001) document a positive stock price. n. iv n C reaction to the changes of internet-related names from 1998 to 1999 and h e n g dotcom chi U suggest that this positive valuation effect of corporate name changes is not transitory and remains regardless of the industry firms involve in. Cooper et al. (2005a) show that investors were deceived by companies seeking to be disassociated from internet industry by deleting “dot.com”, “dot.net” or “internet” from their corporate names during the period 1998-2001 and these firms that removed their dotcom names earn a 64% significantly cumulative abnormal return for the 60 days surrounding name change announcements. Cooper, Gulen and Rau (2005b) also find that the valuation effect of name changes exists in the mutual fund name changes. Mutual funds tend to 11.

(20) change their names to take advantage of current hot investment styles and gain a cumulative abnormal flow. In addition, Bae and Wang (2009) examine the wealth effects of Chinese firms listed in the U.S. stock exchange from 2002 to 2008 and find that these firms tend to add “China” or “Chinese” to their names when Chinese stock markets experienced a surge in price. More recently, Liu (2010) examine the valuation effect of corporate name changes over 30 years from 1978 to 2008 and finds that firms changing their names earn significant abnormal returns of 1.41% for the three days around the announcement date especially for smaller and younger firms in manufacturing and service industry experiencing major name changes, and 3.58% for. 治 政 the 40 days surrounding name change announcements, 大 which supports a positive 立 valuation effect of corporate name changes. These studies suggest that corporate name ‧ 國. 學. change effects are associated with investor mania driven by a price pressure induce-. sit. y. Nat. changing corporate names to capture gains.. ‧. bubble in the stock markets; and managers take advantage of investor sentiment by. io. al. er. Previous studies show conflicting results of the valuation effects of corporate name changes in different countries. For example, Josev, Chan and Faff (2004). n. iv n C underwent corporate changes from h e n g cname hi U. examined 107 firms. 1995 to 1999 in. Australia. They found that name changes were associated with a negative impact on stock prices in their event periods. Karbhari, Sori and Mohamad (2004) analyzed the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange between 1984 and 1996, and found corporate name changes had no wealth effects on the shareholders of the firms. Andrikopoulos et al. (2007) found that corporate name changes in the United Kingdom have negative market reaction, and the market reacted slowly to the information content of a name change announcement. More recently, Mase (2009) examined the short-term and long-term valuation effects of corporate name change in the United Kingdom, and 12.

(21) found that firms changing their names performed poorly over 3 years after the name change announcement date. Besides, this long-run poor performance was most significant amongst firms that changed their name completely. I am interested in comparing the valuation effects name changes involving oil related terms between the U.S. and Canadian stock markets. Specifically, I test the following null hypotheses:. H1: Stock price reactions to announcements of name changes involving oil related terms are insignificantly from zero.. 立. 政 治 大. A company name change associated with “oil” or “petroleum” provides a signal. ‧ 國. 學. about the firm’s focus on the oil industry. It is of interest to see if the market responds. ‧. to such a signal. I compare valuation effects of corporate name changes between U.S.. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. and Canadian firms. This, in turn, gives rise to the following hypothesis.. H2: The magnitude of stock price reaction to announcements of “name changes. n. iv n C involving oil related terms h is the same between e n g c h i U U.S. and Canadian stock markets.. Market response to corporate name change may not be symmetric across different market conditions. Therefore, I compare valuation effects of corporate name changes during the hot market period and financial crisis period. This gives rise to the following hypothesis.. H3: The magnitude of stock price reaction to announcements of name changes 13.

(22) involving oil related terms is the same between the hot market period and financial crisis period.. To investigate the valuation effects of different types of name changes, I classify corporate name changes into the three categories: (1) adding versus deleting the word “oil” or “petroleum”, (2) major versus minor name changes, and (3) resource-related versus resource-unrelated name changes. I test the following hypotheses regarding the relationship between the valuation effects of corporate name changes and the types of name change.. 立. 政 治 大. H4: The magnitude of stock price reaction to announcements of company’s name. ‧ 國. 學. changes is the same between companies adding “oil” or “petroleum” to their. ‧. names and companies deleting the words from their names.. sit. y. Nat. H5: The magnitude of stock price reaction to announcements of name changes. io. changes.. al. er. involving oil related terms is the same between major and minor name. n. iv n C of name changes is H : The magnitude of stock pricehreaction to announcements engchi U 6. the same between resource-related and resource-unrelated name changes.. 3. Data and Methodology 3.1 Data Description The sample consists of companies that changed names in the U.S. and Canadian markets from January 2000 to June 2009. The U.S. companies are traded in the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), American Stock Exchange (AMEX), National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation System (NASDAQ), or Over 14.

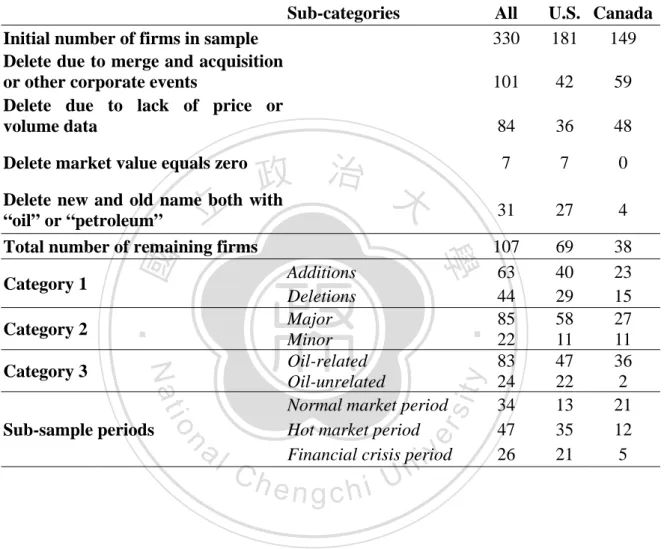

(23) the Counter Bulletin Board (OTCBB). The Canadian companies are traded in the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX), Venture Exchange (TSX Venture), or NEX Board (NEX). I search for corporate name change events that are associated with the words “oil” or “petroleum” from these exchanges and cross check the sample firms with the Mergent Event Data. The initial sample consists of 330 announcements of relevant name changes. Since the information of name changes may be released to the market before it is officially announced by the stock exchanges, I also search for news reports for relevant name changes. I consider two choices regarding the announcement day (or the event day): (1) the day when stock exchanges announced corporate name. 治 政 changes; and (2) the first available day of name changes 大news in the Factiva database. 立 I use the earlier one between these two dates as the event day.. Nat. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 [Insert Table 2.1 here]. io. er. Daily stock returns, benchmark indices, and oil price are obtained from Datastream.4 I delete 84 name changes due to insufficient price data in the event. al. n. iv n C periods; 101 due to concurrent announcement h e n g cofh mergers i U & acquisitions, divestiture, and other major events. The final sample consists of 107 name changes involving the term “oil” or “petroleum.” Table 2.1 summarizes the information of the sample. I divide the sample firms into three categories based on the firm’s characteristics and the nature of name change. Category 1 separates name changes that add the word. “oil” or “petroleum” from those that delete oil-related terms. More than half of the 107 name changes add the words “oil” or “petroleum” to the corporate name for the combined sample. In the U.S. market, there are more firms adding oil related terms to 4. Market value on Datastream is the share price multiplied by the number of ordinary shares in issue. I use the Datastream North America Oil & Gas price index as market index in the market-adjusted model. 15.

(24) their names than deleting those terms (40 vs. 29), Canadian firms show a similar pattern (23 vs. 15). Category 2 separates major name changes from minor name changes following Bosch and Hirschey (1989). A major name change refers to the case that the new corporate name is entirely different from the original name. A minor name change allows investors to identify the association with the original name. For example, the change from Benton Oil & Gas Co. to Harvest Natural Resource represents a major name change since the new name is totally different from the original one. On the other hand, the change from Tesoro Petroleum Corp to Tesoro Corporation represents. 治 政 a minor name change. The majority of corporate name 大changes in the sample firms 立 are major changes. The percentage of major name changes for the combined sample, ‧ 國. 學. U.S. sample, and Canadian sample is 79 percent, 78 percent, and 81 percent,. ‧. respectively. sit. y. Nat. Category 3 separates firms in oil-related sectors from firms in oil-unrelated. io. al. er. sectors. This classification considers the core business of companies which is based on sector specification in Datastream. If a firm’s core business is not belonging to oil. n. iv n C and gas producers or oil equipmenthand service sectors, e n g c h i U the firm is in an oil-unrelated sector. For example, Wilshire Oil Company of Texas changed its name to Wilshire Enterprise, Inc., according to the sector classification of Datastream, Wilhshire Enterprise, Inc. is in the real estate investment and services sector. Therefore, this name change is in the category of oil-unrelated sector’s change. I hypothesize that if a company belong to an oil-related sector, investors are less likely to believe that name changes are artificial. There are more firms in oil-related sectors than those from oil-unrelated sectors in both the U.S. and Canadian markets. To examine the wealth effects of name changes under different market 16.

(25) conditions, I divide the sample into three sub-periods: normal oil market, hot oil market, and the financial crisis period. As shown in Figure 2.1, the crude oil price shows a sustainable upward trend started from the first quarter of 2004. Therefore, I choose January 2004 as the cutoff point between normal and hot markets. While the oil price started surging in 2004 and reached its peak on July 2008, I expect the financial crisis (from July 2007 to June 2009) would affect investor sentiments and thus have impact on investors’ reaction to corporate name changes. There is no consensus on exactly when the recent financial crisis started; however, most agree that the crisis exploded in the mid-2007 when Bear Stearns halted redemptions for two of. 治 政 its hedge funds. As the recent recession triggered by the 大financial crisis was officially 立 ended at June 2009, I define the financial crisis period as July 2007-June 2009. To 5. ‧ 國. 學. isolate the potential impact of financial crisis on market reaction to corporate name. ‧. changes, I focus on the hot oil market period that is not overlapped with the financial. sit. y. Nat. crisis, and thus, end the hot market period at June 2007. For the combined sample,. io. al. er. the number of name changes during the normal period is lower than that for the hot. n. market period (34 versus 47). More U.S. firms have their name changed during the hot market period (35) than. iv n C the h normal period (13), e n g c h i U while. more Canadian firms. change their names during the normal period (21) than the hot market period (12). It seems that U.S firms are more likely to capture investor sentiment by changing corporate names during the hot market. Timing market for corporate name changes is less evident in the Canadian markets. Figure 2.1 shows the number of name changes adding and deleting the word “oil” or “petroleum” together with the trend of crude oil price. Before the first quarter of 2004, I find no particular relations between the number of name changes adding 5. I have employed structure break methodology to choose the cutoff point over the whole period. The empirical result is still robust when I use the structure break methodology. 17.

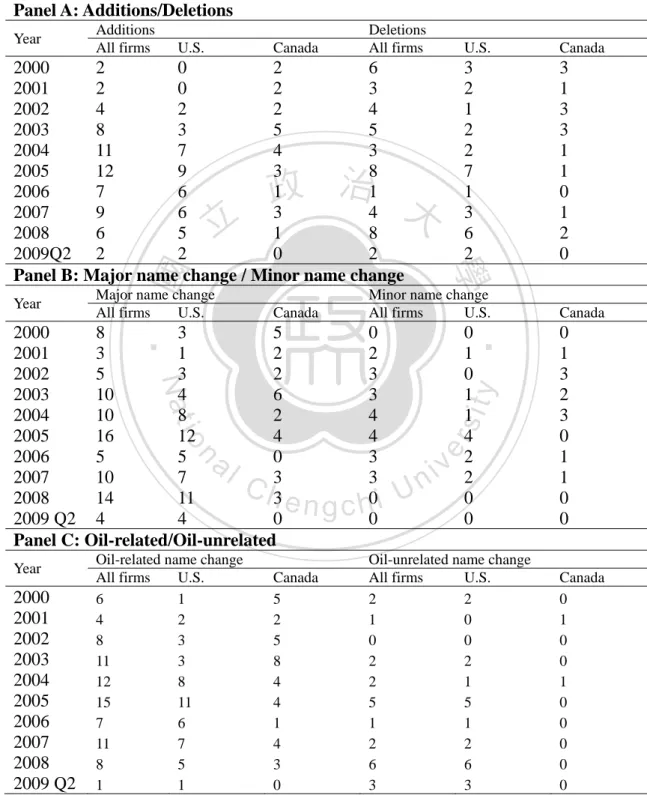

(26) and deleting oil-related terms. However, in the hot market period, the number of name changes adding oil-related terms increases substantially and outweighs the number of name changes deleting oil related terms.. [Insert Figure 2.1 and Table 2.2 here]. Table 2.2 reports the number of different types of name changes during the sampling period. Panel A of Table 2.2 shows that the number of firms experiencing name changes is the largest in 2005 during the sample period. This may due to the. 治 政 fact that oil price is high in 2005 and drops from $77.03 大per barrel in the beginning of 立 2006 to $56.27 per barrel in November 2006. There are more name changes with ‧ 國. 學. addition than deletion of oil-related terms during 2003-2007. Panel B shows more. ‧. major name changes than minor name changes every year. Panel C shows that the. sit. y. Nat. number of oil-related name changes in the U.S. market increases sharply in 2005.. io. al. er. This indicates that U.S. corporations have an urge to signal their association with the. n. oil industry while the oil price is surging; a sign of capturing investor sentiment.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3.2 Methodology Standard event study methodology is used in this chapter. I compute abnormal returns in the following ways. First, for each security i, the market model is used to calculate for day t as follows: Ri ,t = α i + β i Rm ,t + ε i ,t ,. (1). where Rit is the return for firm i on day t and Rmt is the market return using the Datastream North America Oil & Gas stock price index from (-120, -16). I compute abnormal returns (AR) for firm i on day t as follows: 18.

(27) ARit = Rit − αˆ i − βˆi Rmt. (2). I then compute the cumulative abnormal return (CARi) for firm i for various event windows from t = j to t = k as k. CARi = ∑ ARit. (3). t= j. The mean cumulative abnormal return (CAR) of N firms is N. CAR =. ∑ CAR. i. i =1. (4). N. 政 治 大. The corresponding t-statistics that measure whether the CAR is significantly different. 立. from zero is. CAR , Var (CARi ) N. (5). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. t (CAR) =. Nat. sit. y. Where Var(CARi) is the variance of CARi among N firms.. n. al. er. io. I also use a two-sample t-statistics to test whether different CARs in two. i Un. v. subcategories are equal to each other. The t-statistic of two-sample mean cumulative abnormal return is as follows:. t=. Ch. engchi. CARS 1 − CARS 1 S S21 S S22 + N S1 N S 2. ,. (6). Where CARS 1 ( CAR S 2 ) is the CAR of subcategory 1(subcategory 2), S S21 ( S S22 ) is the variance of CARi in subcategory 1(subcategory 2), and N S 1 ( N S 2 ) is the number of firms in subcategory 1(subcategory 2).. 19.

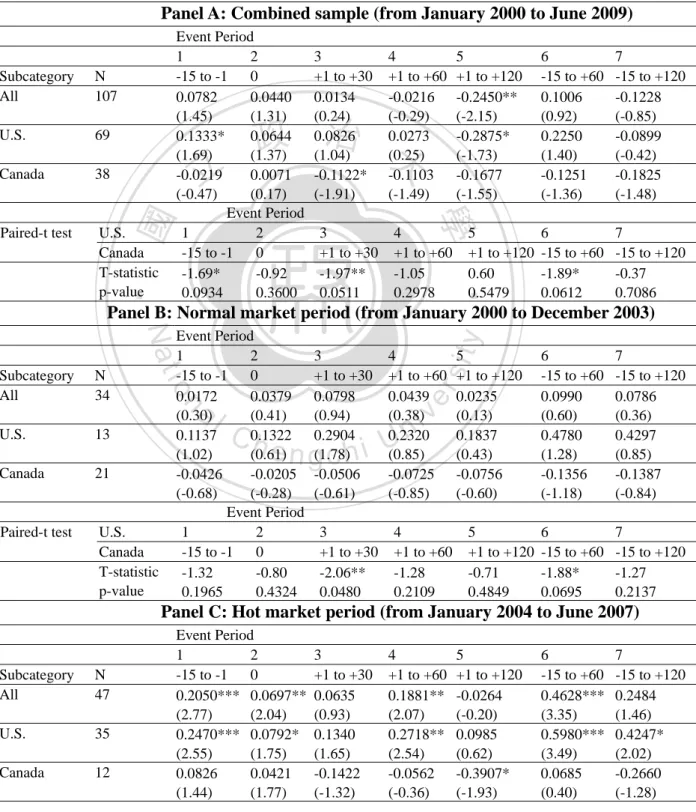

(28) 4. Empirical results 4.1. Wealth effects of corporate name changes involving oil-related terms In estimating abnormal returns around the event day, I exclude firms that have no trading volume from day -1 to day +1 relative to the event day to avoid the impact of stale trading.. I calculated abnormal returns for seven event windows.. As. illustrated in Figure 2.1, there are more companies adding “oil” or “petroleum” to their names than deleting them during the hot market. If investors are affected by cosmetic changes in corporate names and managers take advantage of investors’ irrationality, I expect wealth effects of corporate name changes would be varying. 治 政 across different market conditions. Panels A, B, C,大 and D of Table 2.3 report the 立 abnormal returns during the full sampling period, normal market, hot market, and the ‧ 國. 學. financial crisis period. For each time period, I present the results for the combined. Nat. io. al. er. [Insert Table 2.3 here]. sit. y. ‧. sample, U.S. sample, and the Canadian sample. .. n. iv n C Panel A of Table 2.3 shows no of strong market reaction for the full h eevidence ngchi U sampling period. None of the combined sample, the U.S. sample, and the Canadian sample illustrates a significant abnormal return on the event date. These results on the event day are aligned with previous results in Howe (1982), Horsky and Swyngedouw (1987), Bosch and Hirschey (1989) 6 and Karpoff and Rankine (1994), but are inconsistent with those in Lee (2001), Cooper, Dimitrov, and Rau (2001) and Copper et al. (2005). Both the combined sample and the U.S. sample have a significant and negative CARs in the (+1, +120) window. Most of the CARs for the Canadian sample 6. Bosch and Hirschey (1989) find a positive preannouncement effect followed by a negative postannouncement drift. 20.

(29) are negative, but only the one in the (+1, +30) window is statistically significant. The paired-test indicates that the CARs for the Canadian market are significantly lower than those for the U.S. market in 3 event windows. As shown in Panel B of Table 2.3, when oil prices were relative stable, corporate name change failed to induce significant market reaction. There are no significant CARs across all event windows and all samples during the normal market period. Panel C of Table 2.3 tells a totally different story for the hot market period. There is strong evidence that investors respond positively to corporate name changes involving oil-related words when oil price was surging and the recent financial crisis. 治 政 has not been exploded. For the combined sample and大 the U.S. sample, the abnormal 立 return on the event date is significantly positive (6.97% and 7.92% respectively). The ‧ 國. 學. positive wealth effect carry over to post-announcement periods; CARs for the. ‧. combined sample are significantly greater than zero in the (+1, +60) and (-15, +60). sit. y. Nat. windows. The U.S sample illustrates an even stronger positive reaction. The CARs. io. al. er. for the U.S. sample are significantly positive in six out of seven event windows. The CARs in the pre-event window (-1, -15) for both the combined sample and the U.S.. n. iv n C sample are also positively significant, indicates a possible leakage of information h ethis ngchi U before the announcement date. The finding for the combined sample and the U.S. sample during the hot market period is consistent with the investor mania hypothesis. The results for the Canadian market are similar to those during the normal market period. None of the CARs for the Canadian sample is significantly positive; a significant and negative CAR is found for the post event window (+1, +120). This result is contrary to the conjecture of investor irrationality during an abnormal market condition.. Canadian investors seem not to respond to corporate name change. involving oil-term names regardless of the market condition. The pair-t tests show 21.

(30) that CARs for the Canadian market are significantly lower than those in the U.S. market in five event windows. It is evident that U.S. investors and Canadian investors react to corporate name change involving oil-related terms differently. The above results illustrate that investors react positively to corporate name changes when oil price surge. However, when the financial crisis exploded, the anxiety of overall financial and economic stability may out weight the positive reaction to corporate name change. Even oil price was continued to surge between July 2007 and June 2008, positive market responses are vanished when the period (from July 2007 to June 2008) is added to hot market period; this highlights the. 治 政 adverse impacts of financial crisis. 大 立 To further assess the impact of financial crisis on the wealth effects of corporate ‧ 國. 學. name changes, I examine the market reaction during the crisis period (from July 2007. ‧. to June 2009). The results are shown in Panel D of Table 2.3.. sit. y. Nat. Panel D show negative and significant CARs for relative long event windows for. io. al. er. the combined sample and the U.S. sample. CARs are significantly negative in four event windows (+1, +60), (+1, +120), (-15, 60), and (-15, +120). There are only five. n. iv n C name changes for the Canadian market, large enough to draw meaningful h e n itgiscnot hi U conclusion. As oil price continued surging between July 2007 and July 2008, the negative market reaction found during the financial crisis period implies that overall market sentiment dominates the market condition in the oil industry. Together with the results for the normal and hot oil market periods, I conclude that while oil price surge, investors respond positively to corporate name changes, however, the positive reaction vanished as the recent financial crisis exploded. Increasing volatility and uncertainty wipe out the optimisms generated by surging oil prices.. It is convincible that investors expect economic hardship caused by the 22.

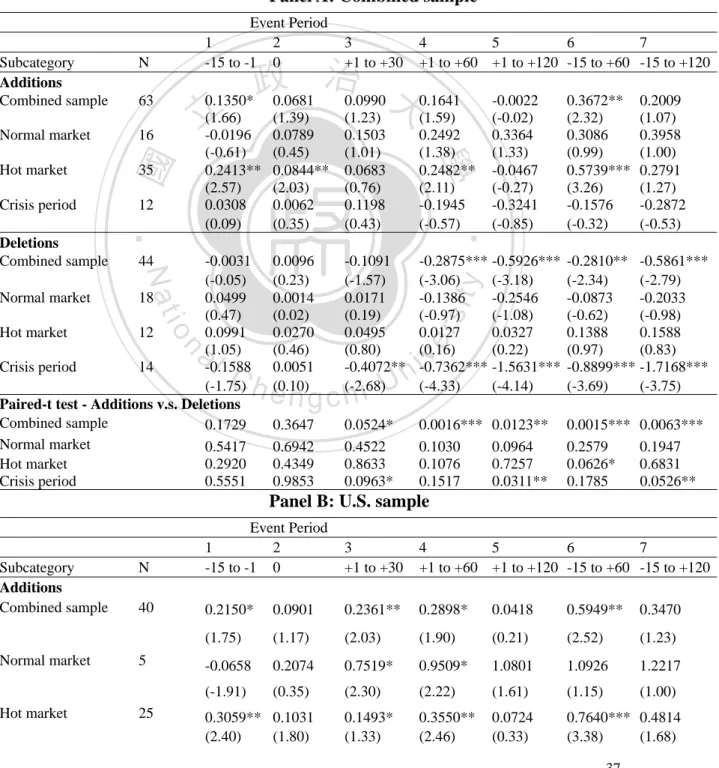

(31) financial crisis, which in turn, would hurt the oil industry and high oil price is not expected to be sustainable. Figures 2.4 and 2.5 compare the CARs for the U.S. and Canadian firms during the hot market period and the financial crisis period, respectively, In Figures 2.4, the CARs for the U.S. sample continue rising after the announcement day. On the other hand, the CARs for the Canadian sample are below zero over a large portion of the event window. As shown in Figure 2.5, during the financial crisis period, the CARs for the U.S. sample are slightly above zero within a short window around the event date, and then. 學 [Insert Figures 2.2, 2.4 and 2.5 here]. Nat. io. al. er. 4.1.1 Addition versus deletion of oil-related terms. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 治 政 show a significant downward drift. For the Canadian 大sample, the CARs never rise 立 above zero and the downward trend is more acute than that for the U.S. sample.. To further explore the impact of corporate name change events, I divided the. n. iv n C sample into addition and deletion of h oil-related i Uand the results for various sube n g c hterms. periods are reported in Table 2.4. Panel A of Table 2.4 shows that companies adding the word “oil” or “petroleum” to their names show significant CARs of 13.5% and 36.7% in event windows (-15, -1) and (-15, +60) respectively for the combined sample. In contrast, CARs of the deletion sample are negative in four event windows. Adding oil-related term seems to provide a positive signal while a deletion conveys negative information. Market conditions have a great impact on the results.. The significant and. positive CARs for firms adding oil-related terms exist only during the hot market, in 23.

(32) which, CARs are significant in four event windows including the event date. None of the CARs during the normal market and the crisis period are significantly different from zero. Similarly, the negative market responses related to deletion of oil-related terms occur only during the crisis period. The CARs during the crisis period are significant negative in five event windows. As for the U.S. firms, Panel B of Table 2.4 shows that adding “oil” or “petroleum” to company names have more positive wealth effects than the combined sample.. Positive CARs are evident during all sampling periods, except for the. financial crisis period. Strongest positive market reactions are found during the hot. 治 政 market period, in which, CARs are significantly greater 大 than zero in five event 立 windows. During the normal market, U.S. firms adding oil-related terms to their ‧ 國. 學. name also show positive market reaction within 2 months after the event date. The. ‧. results for firms deleting oil-related terms are parallel to those for the combined. sit. y. Nat. sample. A deletion of oil-related term is associated with significant and negative. io. al. er. market reaction during the full sampling period and the financial crisis period. As more than 71% of the 35 U.S. name changes during the hot market period add oil-. n. iv n C related terms, these results are consistent the conjecture that managers try to h e n gwith chi U. benefit from investor sentiment by adding oil-related terms to their corporate names when the oil market is hot. The Canadian sample shows no evident of significant market reaction regardless of addition of deletion of oil-related term. As seen in Panel C of Table 2.4, for the full sampling period, Canadian firms adding oil-related term has a marginally significant and positive abnormal return on the event day, but it quickly reverts and shows a significant CAR in the (+1, +30) window. Most of the CARs for other periods are insignificant. Similar results are found for the deletion cases. 24.

(33) Results in Table 2.4 suggest that the U.S. market treats an addition of “oil” or ”petroleum” to corporate names as a major signal for post-announcement windows, while a deletion of “oil” or ”petroleum” from company names conveys less important information.. However the positive effect exists only during hot market period.. Negative market reactions to deletion of oil-related term are intensified during the financial crisis.. [Insert Table 2.4 here]. 治 政 4.1.2 Major versus minor name changes 大 立 In Table 2.5, I provide results for major and minor name changes.. A major. ‧ 國. 學. name change refers to the case that the new corporate name is entirely different from. ‧. the original name. A minor name change allows investors identify the association. sit. y. Nat. with the original name.. io. al. er. As Panel A of Table 2.5 shows for the combined sample, major name changes yield positive wealth effects only during the hot market period. In contrast, the CARs. n. iv n C of major name changes are significantly in four event windows during the h e nnegative gchi U financial crisis period.. Investors do not respond to minor name changes across. different time periods. The significant CARs during the hot market and the crisis period support the claim that major name changes convey stronger information. However, a major name change was received as a positive signal when oil price surged, but a negative signal when the financial crisis exploded. This further indicates that the overall market sentiment caused by the financial crisis plays a dominate role in determining investors response to corporate name changes. The U.S. sample shows the same pattern of CARs as the combined sample during the hot market period and 25.

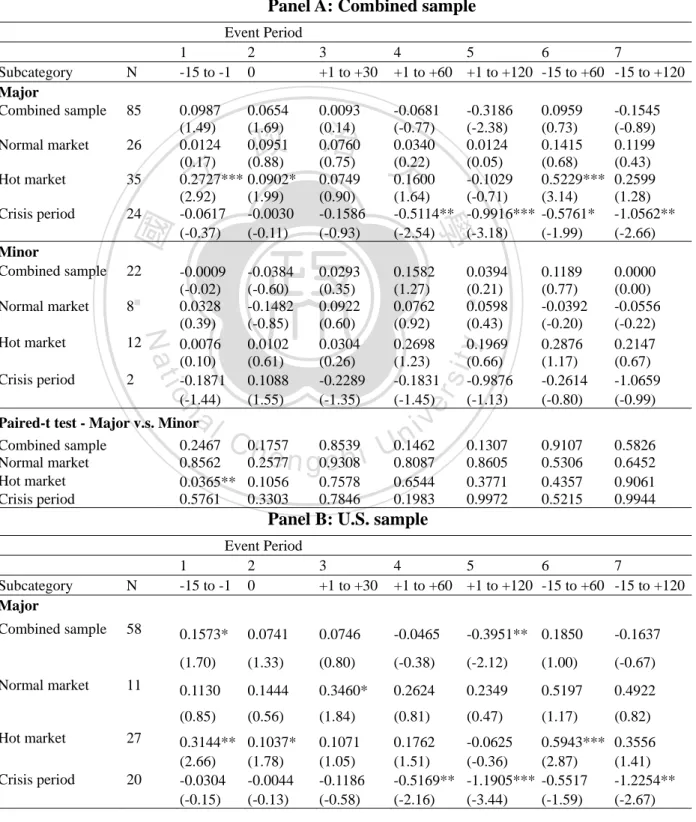

(34) the financial crisis. For the full sampling period, positive abnormal returns exist before the event date but are following by a negative drift. Panel C shows that during the full sampling period, Canadian firms announcing a major name change has a significant and positive abnormal return on the event day, but the positive reaction is not sustainable. The relative sample small size makes it hard to draw conclusion for other sampling periods.. [Insert Table 2.5 here]. 治 政 4.1.3 Oil-related sectors versus oil-unrelated sectors大 立 Results for firms in the oil-related sectors versus firms in oil-unrelated sectors ‧ 國. 學. are presented in Table 2.6. In Panel A of Table 2.6, significant and positive abnormal. ‧. returns are observed for firms in the oil-related sector in the (-15, +60) windows. The. sit. y. Nat. price reactions of oil-unrelated firms are weaker; none of the CARs for firms not. io. al. er. belonging to oil-related sectors are significantly different from zero Results for the U.S. sample are similar to those of the combined sample.. n. iv n C Significant and positive CARs arehfound in the (+1, U e n g c h i 30), (+1, +60) and (-15 to +60). windows for oil-related firms. The positive wealth effects for oil-related firms are stronger and more persistent during the hot market period. On the other hand, name changes of oil-unrelated firms lead to negative market reaction.. The negative. responses are more acute during the crisis period. Results for the U.S. sample are parallel to those of the combined sample (see Panel A).. Significant and positive. market reaction to name changes of oil-related firms are found only during the full sampling period and the hot market period, with much stronger results during the hot market. Similarly, negative market responses are found during the full sampling 26.

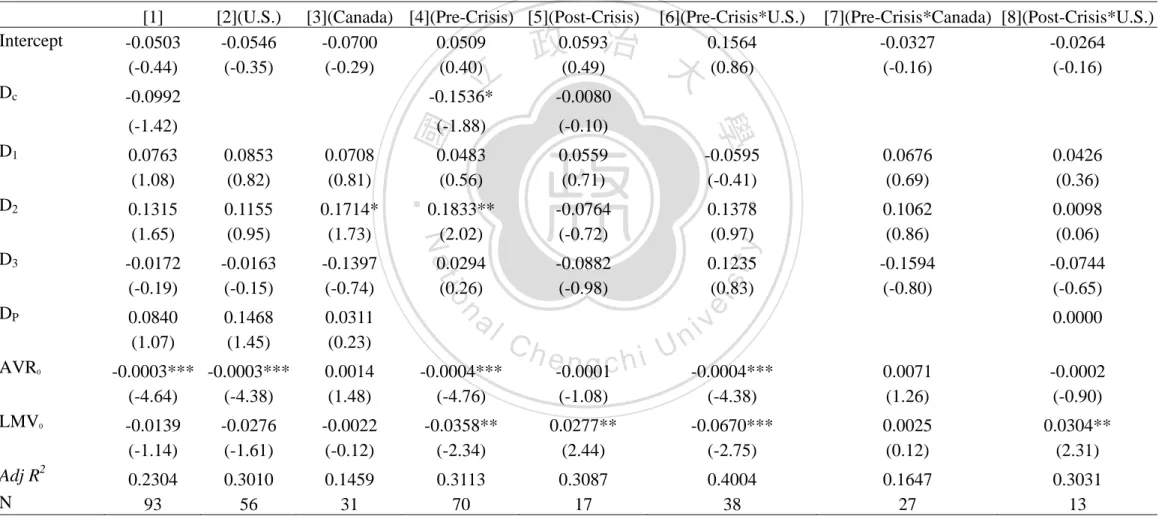

(35) period and the crisis period, with stronger negative CARs in during the financial crisis. Panel C further indicate that Canadian investors are not responsive to corporate name changes regardless of the nature of name changes.. [Insert Table 2.6 here]. 4.2 Cross-sectional Regression Analysis 4.2.1 The Cross-sectional Regression Analysis of CAR. 政 治 大 effect of oil-related name changes on stock prices. I construct three cross-sectional 立 In this section I use cross-sectional regression analysis to examine the wealth. ‧ 國. 學. regressions as follows:. ‧. CAR0 = β 0 + β1 DC + β 2 D1 + β 3 D2 + β 4 D3 + β 5 D P + β 6 AVR0 + β 7 LMV0 + e0. y. (7). sit. Nat. CAR( −15,60) = β 0 + β1 DC + β 2 D1 + β 3 D2 + β 4 D3 + β 5 DP + β 6 AVR( −15,60) + β 7 LMV( −15,60) + e0. (8). n. er. io. CAR( −15,120) = β 0 + β1 DC + β 2 D1 + β3 D2 + β 4 D3 + β 5 DP + β 6 AVR( −15,120) + β 7 LMV( −15,120) + e0. al. (6). Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In these three regressions, each observation represents a single oil-related corporate name event. The dependent variable is the cumulative abnormal return ( CAR ) on the event day (in regression (6)), from the 15 days before the event date to the 120 days after the event date (in regression (7)), and from the 15 days before the event date to the 60 days after the event date (in regression (8)), respectively. To examine the wealth effect difference of name changes between U.S. and Canada stock markets, I define a dummy variable, DC , which equals one for Canadian firms and zero for the U.S. firms. Besides, to examine the wealth effect difference of name changes between pre-financial crisis and financial crisis period, I define a dummy 27.

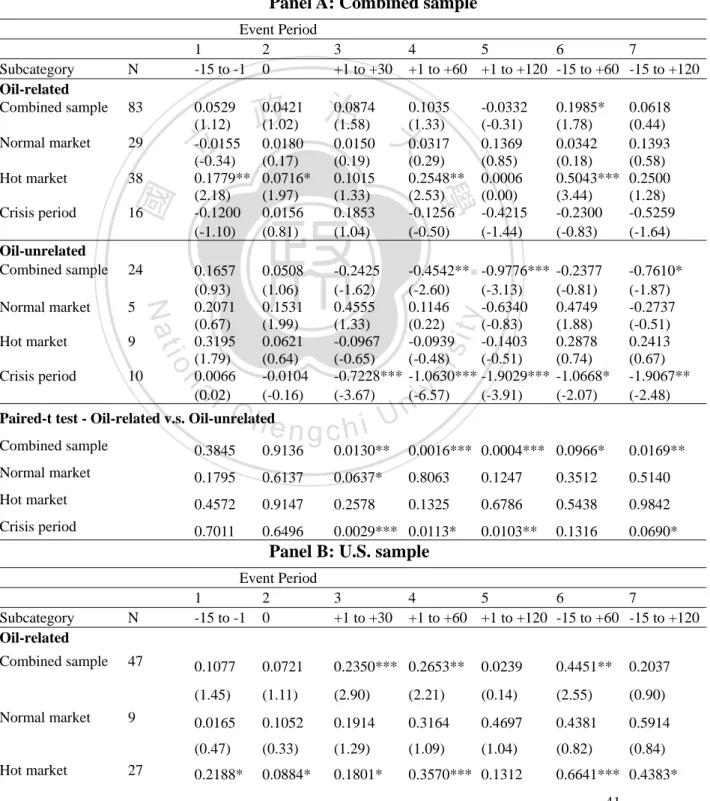

(36) variable, D p , which equals one for the period before financial crisis and zero for financial crisis period. I also define three dummy variables, D1 , D2 , and D3 . D1 takes the value of one for firm adding the words “oil” or “petroleum” and zero for those deleting them. D2 equals one for major name changes and zero for minor name changes. D3 takes the value of one for oil-related firms and zero for oil-unrelated firms. Finally, I include abnormal volume ratio and natural logarithm of the equity market value as explanatory variables. The results of cross-sectional regressions of CARs on the event day, CARs. 政 治 大 from the 15 days before the event date to the 120 days after the event date is reported 立. from the 15 days before the event date to the 60 days after the event date, and CARs. ‧ 國. 學. in Table 2.7, Table 2.8 and Table 2.9, respectively. The result in column 4 of table 2.7 show that U.S. firms with less abnormal volume and less market value announcing. ‧. major name changes are associated with higher cumulative abnormal return.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. [Insert Table 2.7 here]. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The results in column 1 and 2 of Table 2.8 shows that before financial crisis, U.S. firms change their name by adding the words “oil” or “petroleum” are associated with higher cumulative abnormal return. In column 3 of Table 2.8 shows that Canada firms change their name before financial crisis are associated with higher cumulative abnormal return. The results in Table 2.9 show the similar result with Table 2.8. These results of cross-sectional regression are consistent with preceding results in section 4.1. [Insert Table 2.8 here] [Insert Table 2.9 here] 28.

(37) 4.2.2 The Cross-sectional Regression Analysis of Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) In this section, I formally test whether the valuation effect of Oil-related name changes on stock performance exists after controlling for firm risk and firm characteristics in a multivariate regression framework. First, I compute the cumulative return performances (Buy-and-Hold Return, BHR) of Oil-name stocks and Non-Oilname stocks.7 The Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) as follows:. ⎡ τ ⎤ ⎢∏ (1 + Rit ) − 1⎥ ⎣ t =1 ⎦. (9). 政 治 大. where Rit is the daily return of stock i at day t.. 立. I construct the cross-sectional regressions of Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) as:. ‧ 國. 學. BHR = β 0 + β1OilName + β 2 MV + β3 DTA + β 4CashFlow + β5 MTB + β 6 Amihud + β 7 Beta + e0. (10). In the cross-section regression analysis, I use Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) as. ‧. the dependent variable. As for the explanatory variables, I include the Oil-name. y. Nat. io. sit. dummy, which equals one if a sample stock is an Oil-name stock, the logarithm of. n. al. er. market capitalization(MV), which is the product of the stock price and the number of. Ch. i Un. v. shares outstanding at the beginning of each sample period, leverage (DTA), which is. engchi. computed as the ratio of the sum of debt in current liabilities and long-term debt to the book value of assets, cash flow, which is measured as operating income before depreciation scaled by total assets, market-to-book ratio (MTB), which is the ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of assets, Amihud illiquidity measure (Amihud), which is computed as the average ratio of the daily absolute return to the daily trading volume, and market betas (Beta) with respect to Datastream North America Oil & Gas price index. For the firm characteristics variables, I use financial 7. The sample of Non-oil name stocks is a price-matched control group of firms selected from all OTCBB, Toronto and TSX Ventures oil-related firms that did not change their names over each of the subsample periods. 29.

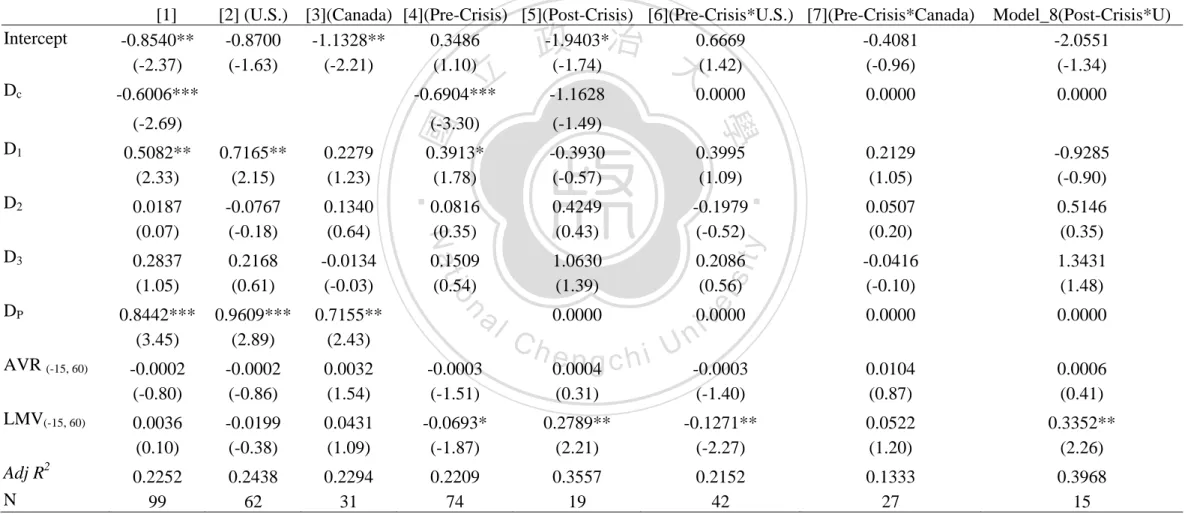

(38) statements data as of the fiscal year end of 2000 for the normal market period, 2004 for the hot market period and 2007 for the financial crisis periods. Table 2.10 presents the results of regression analyses using Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) as the dependent variable. The first three columns 1 to 3 of Table 2.10 examine the effect of an Oil-name change on the Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) for all stocks for each of the three sample periods—the normal market, hot market, and financial crisis periods, respectively. The columns 4 to 6 of Table 2.10 include US stocks, while the columns 7 to 8 of Table 2.10 include Canada stocks. The result in column 5 of Table 2.10 shows a significantly positive effect of the Oil-name dummy. 治 政 on Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR). The coefficient estimate 大 on the Oil-name dummy is 立 0.4669, suggesting that in US stock market Oil-name stocks significantly outperform ‧ 國. 學. non-China-name stocks towards 50 percentage points during the hot market period.. ‧. However, the result in column 8 of Table 2.10 shows that there is no significant. sit. y. Nat. difference in Buy-and-Hold Return (BHR) between Oil-name stocks and Non-Oil-. io. er. name stocks in Canada stock market. This result is consistent with the foregoing. al. n. empirical results. The wealth effect of corporate name changes is stronger in US stock. ni market during there is a surge inC oilhprice. U engchi. v. [Insert Table 2.10 here]. 5. Conclusions I analyze the effects of corporate name changes for a sample of U.S. and Canadian firms from January 2000 to June 2009. There are differences between the market responses to corporate name changes in the U.S. and Canadian markets. In 30.

(39) general, the results show that U.S. companies that changed oil related terms to their company names tend to make major name changes, belong to resource-related category, and make name changes during the oil price surge. Canadian companies are the opposite. With regards to the price reactions, I show that U.S. investors react to name change events more positively than those in Canada. I also observe that U.S. investors seem to respond more enthusiastically to name changes involving oil related terms than Canadian investors. In addition, I find that there is a significant negative post-announcement drift for Canadian firms that change their names during the sample period. The results for the whole sample period indicate that firms that add. 治 政 “oil” or “petroleum” into their corporate names 大 show significant and positive 立 abnormal returns, while those deleted “oil” or “petroleum” from their names shows ‧ 國. 學. negative reaction after the event day. In general, market responses for major name. sit. y. Nat. stronger in the U.S. market.. ‧. changes, changes that adding oil related terms and during the oil hot market are. io. al. er. My findings show that there are different market responses among the different market conditions. There are no significant CARs across all event windows. n. iv n C and all samples during the normalh market period. Canadian investors seem not to engchi U. respond to corporate name change involving oil-term names regardless of the market condition. This might be due to the different economic structure between U.S. and Canada. In recently years, Canada becomes a big oil exporter of the world, while U.S. is an oil importer.8 I consider that the different structure in oil industry between US and Canada that perhaps could explain why investors in Canadian market have less investor mania (insignificant CAR) than those in U.S. stock market. Only the U.S. market shows a significant and positive abnormal return on the event day; a more 8. Until the end of 2009, the percentage of the number of listed firms in oil-related industry to the number of total listed firms in the NYSE and NASDAQ market is 6%, while the percentage in Toronto and TSX Ventures is more than 50%. 31.

數據

相關文件

- Teachers can use assessment data more efficiently to examine student performance and to share information about learning progress with individual students and their

With learning interests as predictors, the increases in mathematics achievement were greater for third- graders and girls than for fourth-graders and boys; growth in learning

最新的權威性的美國市調公司─鮑爾市場研究公司 J.D.Power. 1)

Based on the author's empirical evidence and experience in He Hua Temple from 2008 to 2010, the paper aims at investigating the acculturation and effect of Fo Guang Shan

中國春秋時期 (The period of Spring and Autumn in China) (770-476BC).. I am from the state of Lu in the Zhou dynasty. I am an official and over 60 years old. Her name is Yan

Starting from January 2006, the CPI has been rebased to July 2004 to June 2005, apart from the compilation of the Composite CPI that reflects the impacts of price changes for

Ma, T.C., “The Effect of Competition Law Enforcement on Economic Growth”, Journal of Competition Law and Economics 2010, 10. Manne, H., “Mergers and the Market for

The significant and positive abnormal returns are found on all sample in BCG Matrix quadrants.The cumulative abnormal returns of problem and cow quadrants are higher than dog and