國立臺東大學兒童文學研究所 碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Children’s Literature of National Taitung University in Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

指導教授:陳淑芬 博士 Advisor: Dr. Shu-Fen Chen

成長的「通道旅程」:

《第十四道門》中的成長再現

Portal-quest for Growth:

The Representation of Coming of Age in Coraline

研究生:李沛涵 撰

Graduate Student: Karen Pei-Han Lee

中華民國一 ○ 二年七月

國立臺東大學兒童文學研究所 碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Children’s Literature of National Taitung University in Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

成長的「通道旅程」:

《第十四道門》中的成長再現

Portal-quest for Growth:

The Representation of Coming of Age in Coraline

研 究 生:李沛涵 撰 Graduate Student: Karen Pei-Han Lee

指導教授:陳淑芬 博士 Advisor: Dr. Shu-Fen Chen

中華民國一 ○ 二年七月

Acknowledgements

I’m indebted to those teachers who contributed to my education and research at the Graduate Institute of Children’s Literature, National Taitung University. I would like to thank my committee members Dr.

Shu-Fen Chen, Dr. Tzu-Chang, and Dr. Jungchun Roslyn Ko for their help and support. I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Shu-Fen Chen who first inspired me to explore Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of

“The Uncanny” as a psychoanalytical approach to children’s fantasy literature and encouraged me during my thesis writing process. I would like to thank Dr. Tzu-Chang Chang for participating in my thesis defense presentation and giving me useful suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Robert Seelinger Trites for helping me clarify some ideas that shed light on my research. Last but not least, my deepest thanks goes to Dr.

Jungchun Roslyn Ko who was a source of inspiration, support and encouragement to me. I would like to thank her for her valuable suggestions and careful revision of my manuscript with her wealth of knowledge.

成長的「通道旅程」:

《第十四道門》中的成長再現

作者:李沛涵

國立臺東大學兒童文學研究所

摘要

「通道」和「旅程」的概念在兒童奇幻旅程故事中扮演重要的角 色,並具有重要的象徵意義。在這些故事中,成長是一個主要的主題;

其中兒童主角們從真實世界經由「通道」旅行至奇幻世界,在面對及 經歷無數的阻礙與困境後,得以成長和自我實現。尼爾.蓋曼於 2002 年出版的小說《第十四道門》是一個「通道旅程」奇幻故事和成長小 說,其中記錄了主角寇洛琳的心理成長及品德教育的過程。本研究檢 視此小說以成長的再現做為兒童心理及品德的教育方式。本研究的目 的是探討建構《第十四道門》中一些顯著的奇幻元素和民間傳說主題,

像是詭異效果和怪誔元素等。它們不但使得此故事生動有趣,也吸引 讀者關注寇洛琳的心理成長及品德教育的過程。本論文根據《第十四 道門》寇洛琳從真實世界出發前往奇異又危險的反烏托邦奇幻世界後,

之後返家的「通道旅程」中所發生的事件時序,分成五個章節。第壹 章緒論完整地敍述研究背景、目的和理論架構,以及簡介《第十四道

門》中的成長再現和它與「通道旅程」主題的關聯。接下來的三個章 節以冒險旅程故事中建構的「家/離家/家(回家)」的旅程故事模 式來探討「通道旅程」主題。第貮章「家」探討《第十四道門》小說 中,與家/離家/家(回家)旅程故事模式的第一部分與「家」有關 的主題和奇幻元素;第參章「離家」探討旅程故事模式的第二部分; 第 肆章「家(回家)」探討旅程故事模式的最後部分;第伍章為論文結 論。

關鍵字:「通道旅程」、成長小說、詭異效果、怪誕元素、反烏托邦

Portal-quest for Growth:

The Representation of Coming of Age in Coraline

Karen Pei-Han Lee

Abstract

In children’s portal-quest fantasy stories, the concepts of portal and quest play important roles, and they have significant functions and meanings. Growth is the major motif in these stories, in which child protagonists travel from a real world to a fantasy world through portals in order to perform a set task or fulfill a quest for self-fulfillment, acquiring maturity by facing numerous obstacles and going through many hardships.

This study examines the representation of “coming of age” as a means of children’s psychological and moral education in Neil Gaiman’s Coraline (2002) which is a portal-quest fantasy story and Entwicklungsroman that chronicles protagonist Coraline’s psychological and moral growth. The purpose of this study is to discuss some of the prominent fantasy elements and folkloric motifs that help construct Coraline, such as the uncanny effect and grotesque elements that not only make its story appealing but also induce child readers to engage in Coraline’s process of psychological and moral development. This thesis has five chapters that follow the chronology of events that take place in Coraline’s portal-quest in Coraline—starting from the real world, moving towards a fantasy world that is a bizarre and dangerous dystopia, and then finally returning home.

Chapter One, “Introduction,” gives an overall description of the background and purpose of the study, the theoretical frameworks, and a brief introduction of the representation of coming of age and its relation with portal-quest theme in Coraline. The following three chapters explore the portal-quest theme by drawing on the home/away/home (return home) quest-story pattern, a prevalent pattern often constructed in the adventure journey story. Chapter Two ,“Home,” discusses the motifs and fantasy elements employed in Coraline that are germane to “home,” the first part of the quest-story pattern; Chapter Three, “Away,” discusses the second part of the quest-story pattern; Chapter Four, “Home (Return Home),”

discusses the last part of the quest-story pattern; and finally, Chapter Five concludes the thesis.

Keywords: portal-quest, Entwicklungsroman, the uncanny effect, the grotesque elements, dystopia

Acknowledgements……….i

Chinese Abstract………..…………..…ii

Abstract……….……….………...iv

Chapter One Introduction………1

The Representation of Coming of Age in Coraline………..1

Background and Purpose of the Study………….….………2

Theoretical Frameworks……….……..……….9

Chapter Two Home……….……….……..15

The Child Motif……….………..………15

Fear and Anxiety……….………….…………..………22

The Call to Adventure………..…..…………34

The Liminal Space………..………..….38

Chapter Three Away……….………….…42

The World of Imagination…………..………42

Portal-Quest………..………..48

The Uncanny Effect………..….……….…53

Coraline’s Journey to a Dystopia………..…………..………...……65

Chapter Four Home (Return Home)…………..…….…..……….……72

The Grotesque Elements……….………73

Coraline’s Sufferings as Trials………..……..………80

Rites of Passage………..…….……….………..89

Home Again………..…….………..……….….…….99

Chapter Five Conclusion………….……….……….…..…..103

Works Cited……….….…..…107

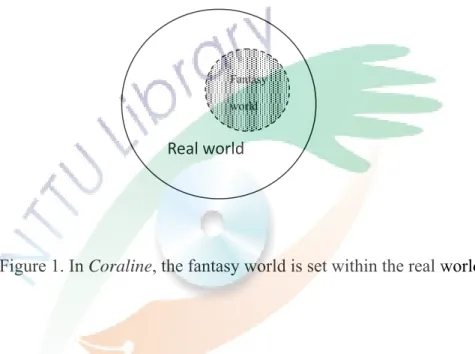

Figure 1. In Coraline, the fantasy world is set within the real world…..39 Figure 2. The uncanny effect often occurs when protagonists travel from

the real world into the fantasy world………57 Figure 3. The circle of Coraline’s portal-quest………...…….101

Chapter One: Introduction

The Representation of Coming of Age in Coraline

In the world of children’s literature, fantasy stories have always been popular with child readers. Through employing myths and fairy tale components as well as literary archetypes, children’s fantasy writers make their stories fascinating and compelling to entertain, enthrall and captivate readers. Children’s fantasy stories are mostly about child protagonist’s growth. In such stories, fantasy elements, folkloric motifs and archetypes are the core components that connect with one another to offer a pattern to represent child protagonist’s maturing process. However, this process is more than just the protagonist’s growing process in any of such stories; in both its internal and external aspects, it is thus an essential component of children’s portal-quest fantasy stories, and has metaphoric meanings in many ways.

The portal-quest is both a motif and concept that plays an important role and has significant functions and meanings in the story of Coraline. Growth is the major theme in Coraline, and it serves as a thread that holds the story together in which protagonist Coraline travels from a real world into a fantasy world through a portal in order to perform a set task or fulfill a quest for self-fulfillment, acquiring maturity by overcoming numerous obstacles and hardships. This study maintains that the representation of coming of age presented with a portal-quest pattern can be literarily constructed and portrayed through narrative, plot, and literary character. This study does not focus so much on the depiction of the Coraline’s development of becoming an adult, as on the portrait of her psychological and moral changes and growth through the representation of plot, narratives, and literary characters in Coraline that

not only engage and develop a sense of wonder in child readers but also contribute to the growth of the protagonist and the reader alike.

Background and Purpose of the Study

Coraline is a 2002 children’s fantasy novella by Neil Gaiman. It is well-received,

and has been adapted into a 3D stop-motion film Coraline (2009) that captures both children’s and adults’ imagination. As a fantasy writer, Gaiman is known for employing folkloric motifs, literary archetypes, myths, and legends into his works of fiction, in which heroes embark on a quest, negotiating and fighting their ways through the perils caused by supernatural forces and mystical beings. Coraline is a modern Gothic novella and a portal-quest fantasy that incorporates portal, fantasy elements, folkloric motifs and literary archetypes to develop a sense of wonder in child readers, while connecting with its young protagonist’s self-discovery quest.

Coraline is also an Entwicklungsroman novella that chronicles protagonist Coraline’s

psychological and moral growth. It has a typical Entwicklungsroman structure of a story about a girl who leaves home and learns moral lessons through her travels and then returns home. In Children’s Literature and Critical Theory, Jill P. May implies that “all children’s books about growth are Bildungsroman” (qtd. in Trites 10).

However, Robert Seelinger Trites argues that May’s definition of the term “ceases to have meaning,” for all children’s books virtually are about growth (10). According to Trites’ definition of Entwicklungsroman and Bildungsroman in Disturbing the Universe: Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature:

the Entwicklungsroman is a broad category of novels in which an adolescent

character grows, and the Bildungsroman, which is a related type of novel in which the adolescent matures to adulthood. Entwicklungsroman can be thought of as novels of growth or development, whereas Bildungsroman are coming-of-age novels that are sometimes referred to as “apprenticeship novels.” (9-10)

Bildungsroman and Entwicklungsroman are both originally from German terms.

“Bildungs” means formation and “Roman” means novel. Generally speaking, Entwicklungsroman refers to “a novel of development” while Bildungsroman refers to

“a novel showing the development of its protagonist.” 1 Coraline is an Entwicklungsroman, for its protagonist doesn’t reach adulthood in the story; however,

the author of the study finds that Coraline offers more meanings to readers than a typical Entwicklungsroman usually offers, for it covers some aspects that are usually depicted in a Bildungsroman (a coming-of-age story). The Bildungsroman, as Jerome Buckley points out, “the novel of youth and moral education, conceives of youth as a process of movement to maturity, and of education as a gradual realization of the lessons of experience” (qtd. in Sircar 163). Although Coraline doesn’t depict protagonist Coraline’s development from childhood to adulthood, it illustrates her psychological and moral growth, her repressed desires of being loved and cared by her busy parents, and her sexual awakening from her supernatural encounters through narratives. Even though she doesn’t become an adult at the end of narratives of the story, she learns to become one through the events occurred during her journeys.

More importantly, all the happenings she goes through during her adventures are related to her psychological and moral developments which are important and inevitable processes before she reaches adulthood, and can be interpreted as the

1 See Random House Publisher’s website “The Maven’s Word of the Day” for more details.

representation (imitation) of her coming of age.

It is acknowledged that children’s fantasy stories are not real; nevertheless people believe that they have a profound influence on young readers especially for educational purpose. The author of the study would like to point out is that imitation is a basic instinct of human nature, and its notion about human psychology and conduct is that children are born to “imitate.” They inherit the instinct the moment they are born, as Aristotle states:

the instinct of imitation is implanted in man from childhood, one difference between him and other animals being that he is the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learns his earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated. (55)

Children imitate what they hear and read, and it’s the imitate action that help them learn. Therefore, children’s stories have the responsibility teaching children right from wrong and helping them making correct decision. The psychological reflections and moral struggles in the story of Coraline serve a didactic purpose by encouraging young readers to make right choices when tempted by evil forces through the representation of protagonist Coraline’s coming-of-age process. The representation here refers to the imitation of the obstacles and hardships a youth must get through before he or she reaches adulthood, and it has a special connection with portal-quest in the story of Coraline.

Portal-quest is the major theme that threads all the events occurred in the story together. Coraline’s portal-quest is about her maturing process, but the process is more than just the course of leaving and returning home. It, in fact, chronicles her

psychological and moral growth during her adventures with growth as the major motif surfacing throughout the story. The story portrays Coraline’s unconventional childhood. Childhood is, without doubt, a stepping stone in children’s lives; therefore, everything that takes place in this period of time is critical to self-development. As a representation of both a fictionalized childhood of a little girl and her psychological and moral developments, Coraline contains that unique move that children’s literature, by its very essence, contains.

This study examines the representation of “coming of age” as a means of children’s psychological and moral education, and investigates the role of portal-quest fantasy story in the moral education and psychological development of the protagonist.

It traces Coraline’s portal-quest as the heroine’s progression from a world she’s familiar with to an unknown world, focusing on the didactic nature implied in the story by drawing on the home/away/home (return home) quest-story pattern, a prevalent story pattern often constructed in children’s fantasy stories. Like many other children’s fantasy stories, Coraline employs the quest-story pattern as its structure of the quest-story plot. Although the pattern is old, it’s molded into a new image and appeal that bring new meanings to the child protagonist and the reader alike.

Through examining the representation of coming of age with portal-quest as the major motif in Coraline, the purpose of this study is to understand what it accomplishes in the realm of children’s literature that distinguishes itself from other children’s fantasy stories. This study also intends to investigate how Gaiman uses fantasy elements and folkloric motifs such as the uncanny effect and grotesque elements to construct the Entwicklungsroman structure of Coraline that not only make the story appealing but also induce child readers to engage in protagonist Coraline’s psychological and moral developments. Coraline is not just a simple children’s

portal-quest fantasy that only entertains readers. In fact, there are many issues employed in the story that readers can chew on. This study divides Coraline’s portal-quest cycle into three stages of both psychological and moral developments that correspond to the home/away/home (return home) quest-story pattern, each involving conflicts or crises that must be solved by Coraline herself. The author of the study has chosen to focus on some fantasy elements, folkloric motifs and literary archetypes employed in Coraline which are pertinent to the growth theme, analyzing how they highlight these stages and contribute to Coraline’s psychological and moral growth. Although they seem to be disparate elements and motifs and not at all representative of the entire scope of the representation of coming of age in Coraline, they are all connected as the indispensable components of the story. This study also aims to investigate how Gaiman uses these components to tell a meaningful story of moral about a girl’s inner struggles against temptation and evil powers, emphasizing the belief that children are supposed to be shaped and molded by severe lessons of how the world really works.

This research is twofold: firstly, this study draws on the home/away/home (return home) quest-story pattern, using Neil Gaiman’s Coraline as an exemplary text on which to base discussion of themes, fantasy elements, folkloric motifs, literary archetypes, narratives, plot and literary characters that are germane to the growth theme. Secondly, these components are chronicled and categorized into three different parts (stages) of the quest-story pattern and discussed throughout the body of the thesis. The main questions addressed in this study are: (1) what is portal-quest and what is its relation with the representation of coming of age as exemplified by Coraline? (2) How do children’s fantasy stories help children deal with their fear and anxiety in their lives? (3) When linked to other fantasy elements and folkloric motifs

employed in Coraline, what kind of meanings and functions do the uncanny effect and the grotesque elements bring to both the protagonist and the reader? (4) Does portal-quest symbolize a ritual for Coraline to get through over the course of her adventures? The author of the study would like to account for these questions through the arguments drawn from several theoretical works that pick up the points the author makes, and integrate those arguments into the ones that support the research.

This thesis has five chapters that follow the chronology of events that take place in Coraline’s portal-quest in Coraline—starting from the real world, moving towards a fantasy world that is a bizarre and dangerous dystopia, and then finally returning home. Chapter One, “Introduction,” gives an overall description of the background and purpose of the study, the theoretical frameworks, and a brief introduction of the representation of coming of age and its relation with portal-quest theme in Coraline.

Chapter Two, “Home,” illustrates the motifs and fantasy elements employed in Coraline that are germane to “home,” the first part of the quest-story pattern. The

child motif and journey (quest) archetypes are the core elements in children’s coming- of-age stories, in which they offer a pattern to present children’s maturing transition through journeys of difficulties and trials. Gaiman’s Coraline, like his other works, is rife with folkloric archetypes and symbols. This chapter examines the ways how Gaiman utilizes the child motif with the image of a little girl as the protagonist in the novella, and how he weaves the elements of fear and anxiety into the fabrics of the story to make it a cautionary tale to young readers. This chapter uses Lucy Lane Clifford’s “The New Mother”, the major influence on the story of Coraline, as a cross-reference. Also, the call to adventure, one of the core elements often employed in journey or adventure stories is explored with Joseph Campbell’s theory from his The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Furthermore, the liminal space is a blurred area

where the real world and the fantasy world intertwine. Instead of representing a clear border, the liminal space serves as a nexus and a critical overlap between the two worlds. As an important literary device and concept used in children’s portal-quest stories, the liminal space is examined in terms of its relation with the setting of the real and the fantasy worlds in the story of Coraline at the end of this chapter.

Chapter Three “Away” explores “away,” the second part of the quest-story pattern. The fantasy world in Coraline is a blurred terrain of the imaginary world where objects and people can be simultaneously real and surreal, and where inanimate objects can display signs of life and free will. This chapter firstly investigates the settings of the story’s fantasy and real worlds in the light of their influences on the plot and characters in Coraline. This chapter then explores the portal-quest motif with regard to its significant meanings and functions, as well as its relation with the representation of coming of age in Coraline. The uncanny effect, portal-quest and dystopia are fantasy elements and folkloric motifs frequently constructed in children’s portal-quest fantasies. The uncanny effect is deftly utilized in Coraline which offers many prominent examples of uncanny narratives, involving inanimate objects with their own volition, phallic imagery, castrating figures and fear of castration. This chapter investigates the ways Gaiman employs the uncanny effect in the setting, plot, and literary characters of the story, using Sigmund Freud’s the uncanny theory as both a means and interpretation of the protagonist’s psychological encounter and development. Furthermore, in order to delve more deeply into the essence of the uncanny, this chapter also utilizes E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” as a second cross-reference. In addition, this chapter investigates Gaiman’s attempt to teach children a moral story by creating a fake utopia that turns out to be a dystopia as a cautionary tale for both the protagonist and the reader.

Chapter Four, “Home (Return Home),” explores “home (return home),” the last part of the quest-story pattern. This chapter deals with the ways Gaiman uses the grotesque elements to structure plot, narratives, scenes and literary characters in Coraline. The novella, whose setting merges the modern world with a fantasy world,

contains grotesqueries in abundance. In addition, it’s worth investigating Gaiman’s attempt to make Coraline suffer during her adventures and its relation with rites of passage. Home (Return Home) part is the main focus of this chapter, and the motifs and fantasy elements that are germane to the part are investigated in relation to their functions in the story. This chapter also discusses Gaiman’s purpose of leading Coraline to a self-discovery quest and depicting her psychological and moral development during her adventures. And finally, Chapter Five, “Conclusion”, concludes the thesis.

Theoretical Frameworks

In this study, the primary theoretical works that are called on are those of Aristotle, Roberta Seelinger Trites, Carl Gustav Jung, Bruno Bettelheim, Sigmund Freud, J. R. R. Tolkien, Joseph Campbell, Maria Nikolajeva, Farah Mendlesohn, David Rudd, and Perry Nodelman. This study uses these works to help investigate the plot, narratives, fantasy components, literary characters and portal-quest as well as the representation of coming of age in Coraline. The concept of portal-quest discussed throughout the study is illustrated firstly by Farah Mendlesohn in Diana Wynne Jones:

Children’s Literature and the Fantastic Tradition. The term “portal-quest” refers to a fantasy story that involves both portal and quest in the plot of portal-quest fantasy stories, in which the protagonist goes on a quest through portals. The author of study

finds that the concept of portal-quest is rather helpful in describing some children’s fantasy stories, in which portal and quest are both employed as literary devices to propel the plots, and also as important symbols to convey deep meanings at the same time.

Chapter One “Introduction,” examines primarily the theoretical works of Aristotle’s Poetics and Roberta Seelinger Trites’ Disturbing the Universe: Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature. This chapter explains Aristotle’s theory,

focusing primarily on the role his theory of “imitation” as “represenation” plays in the plot and purpose of Coraline, and on its relation with those fantasy elements, folkloric motifs and literary archetypes utilized in the story. Moreover, this chapter tries to define what type of an educational novella Coraline is by applying Trites’ theory to differentiate between Bildungsroman and Entwicklungsroman.

Chapter Two “Home,” explores primarily the theoretical works of Carl Jung, Bruno Bettelheim, and Joseph Campbell. Both Jung’s and Bettelheim’s psychoanalytical theories are widely used to analyze the psychological effects children’s literature might have on readers, and investigate the plot of a story and the cause and effect behind the character’s actions from a psychoanalytical point of view.

More importantly, their psychoanalytical theories are germane to the “home” part of the quest-story pattern. This chapter uses Jung’s psychoanalytical theory “the Psychology of the Child Archetype” which he co-authored with C. Kerényi as a way of interrogating the child motif presented in the story of Coraline.

According to Jung, “the child motif represents the preconscious, childhood aspect of the collective psyche” (161). Like Freud’s, Jung’s theories were also originally for psychoanalytical purposes. His “the child archetype” theory can help interpret psychological depiction in the story of Coraline and manifests human’s psyche and behavior as a vestigial motif and action of all human kinds. The powerful

images evoked by the child motif in the collective unconscious encourage readers to explore and appreciate children’s fantasy stories as a rite of its own within literary tradition, proclaiming a new direction for understanding the human psyche.

In The Uses of Enchantment, Bettelheim points out that young child often cannot express his/her feelings of fear or anxiety in words, and even an older child sometimes would keep his/her true feelings inside. He sees overcoming fear and anxiety as an important course in children’s growing up process, using fairy tales as a useful tool in children’s psychological education. This chapter discusses Bettelheim’s ideas about fairy tales as fantasy stories that apply fear and anxiety elements to help child readers deal with their own problems in real life, and contribute to their psychological and emotional growth. This chapter also examines Joseph Campbell’s

“The Call of Adventure” theory from his well-known The Hero with a Thousand Faces to investigate the quest (journey) archetype in Coraline that involves with the

young protagonist’s psychological and emotional obstacles.

In Chapter Three, “Away,” the primary theoretical works that are utilized are J.

R. R. Tolkien’s theoretical essay, “On Fairy-Stories,” and Sigmund Freud’s “The Uncanny,” and Maria Nikolajeva’s theological assumption of “Stereotype of Dystopia”

in Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers. In his well-known essay “On Fairy-Stories” that explicates and maintains the genre of fairy tales as fantasy writing, Tolkien introduces the idea of a secondary world, referring a story-maker as a successful “sub-creator who makes a Secondary World which readers’ mind can enter” (37). This chapter calls on Tolkien’s concept of a secondary world to examine the setting and functions of the fantasy world in the story of Coraline.

The Uncanny (German, Das Unheimliche) became a well-known psychoanalytical concept in 1919, with the publication of Sigmund Freud’s “The

Uncanny.” However, the theory was first introduced by Ernst Jentsch, also a psychiatrist, with his study, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906), in which he proposed a theory of the uncanny, using E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” (1816) (“Der Sandman”) as an example. In 1919, Freud drew on the same story to elaborate and develop the uncanny in greater detail, and introduced the concept of “fear of castration” into an understanding of the uncanny. This study focuses both on the psychological uncertainty proposed by Jentsch as well as the “castration complex”

proposed by Freud as the psychological effect of the uncanny on both protagonists and readers as a literary device used particularly in children’s portal-quest fantasies.

Freud makes it clear in his essay: “the feeling of something uncanny is directed attached to the figure of the Sand-Man, that is, to the idea of being robbed of one’s eyes, and that Jentsch’s point of an intellectual uncertainty has nothing to do with the effect” (205). The author of the study, however, finds that the story of Coraline fits perfectly into the description and employment of both Jentsch’s and Freud’s theories of the uncanny. In addition, some literary critics have interpreted this novella as a story about the sexual discovery of a pre-adolescent girl on the verge of puberty, using the concepts of “fear of castration” and “phallic imagery” from Freud’s “The Uncanny”

(e.g., David Rudd 2008; Chloe Buckley 2010). In his essay “An Eye for an I: Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and Question of Identity” (2008), David Rudd indicates that:

Gaiman has given us a quite overt fictional representation of the Freudian uncanny—not merely by invoking the motifs that Freud enumerates in his essay, but by animating the very etymology of the German term das Unheimliche: heimlich, or homely, with its root in Heim, and its mirror counterpart, the unheimlich” (161).

The author of the study would like to amplify the concepts of the uncanny by linking them with other fantasy elements and folkloric motifs covered in the story, illustrating how the uncanny motifs function as psychological influences that not only provoke uncertainty and disorientation but also remind sexual awakening and repression in the protagonist.

In this chapter the uncanny effect is examined, according to the interpretation of Freud, as it is manifested in Corlaine. This chapter aims to clarify what is meant by

“the uncanny”, and what kind of effect it can produce, and then why it has become a distinctive fantasy element in Coraline, and finally what kind of psychological influences it brings to the protagonist in the story. This chapter also aims to explore how portal-quest is constructed through uncanny and grotesque narratives, what is Gaiman’s attempt to create a dystopia for Coraline to visit, and what are the moral lessons he wants to teach to both the protagonist and the reader. The term and the boundaries of the concept of “dystopia” in this study are demarcated here in the narrow sense of portraying negative vision of paradise, cast mostly in fictional form, which means no realistic, political or historical features are implied in the narrative.

Furthermore, this chapter employs Nikolajeva’s theoretical assumptions to analyze the dystopian tendency in the story of Coraline regarding its relation and meanings with the representation of coming of age.

In Chapter Four “Home (Return Home),” the theoretical works utilized primarily are Wolfgang Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature, Arnold Van

Gennep’s The Rites of Passage, and Perry Nodelman’s The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. In his book, Gennep offers both psychoanalytical and

anthropological studies to examine the rites of passage as important and inevitable stages in each individual’s life and learning process. This chapter utilizes Gennep’s concept to examine the assumption that, for Coraline, the return home process is like

the rites of passage for her go through before she achieves her goals. This chapter also investigates the grotesque elements employed in Coraline and their functions in the story, using Kayser’s theoretical work in which he elaborates the etymology of grotesque and the history of the rise of grotesque as a literary sub-genre. Finally, this chapter examines the quest-story pattern in regard to its functions and meanings with the representation of coming of age in Coraline by drawing on Perry Nodelman’s theoretical work.

Coming of age is generally considered to be a youth’s transition from childhood to adulthood. The focus of the study, however, is not to cover all aspects of the construction and representation of coming of age but to question the ways in which Coraline’s growth is literarily represented in Coraline, and what significant meanings are brought out by weaving some prominent fantasy elements, folkloric motifs and literary archetypes into the story, regardless of the changes of the protagonist’s age or physical appearance in the story. Although this study is far from exhaustive, and less a historical or a social approach of children’s mental growth through reading than an exploration and interpretation of the representation of coming of age in the narratives of Coraline, it attempts to excavate some psychological and moral meanings conveyed through the story, and to integrate psychological analyses and theoretical works in an effort to create a lens through which the understanding of the representation of coming of age in Coraline can be expanded.

Chapter Two Home

This chapter explores those components employed in Coraline that are germane to the “home” part of the quest-story pattern. In this chapter, the questions the author of the study would like to address are: (1) why does Gaiman employ the child archetype to create a child motif for the story? (2) What kind of role does Coraline play as a child archetype? (3) What kind of significant meanings and influences do fear and anxiety bring to both the protagonist and the reader? (4) What are the problems presented in Coraline’s world before she accepts the call to adventure and then embarks on her journeys? (5) What is the liminal space, and what is its relation with the setting and plot of the story? To answer these questions, this chapter calls on primarily the theoretical works of Carl Jung, Maria Nikolajeva, Joseph Campbell, Bruno Bettelheim, using Lucy Lane Clifford’s “The New Mother” as a cross-reference.

The Child Motif

In her book Worlds Within: Children's Fantasy from the Middle Ages to Today, Sheila A. Egoff writes, “Any exploration or investigation of fantasy must therefore begin with its roots, which are deeper than those of any other literary genre, for they lie in the oldest literature of all—myth, legend, and folklore” (3). Rooted from myth, legend, and folklore, children’s literature incorporates many elements from the oldest literature into fascinating stories, providing a guide to life from which children can learn about characters to whom they can relate, and teaching children about the stages

of life such as coming of age as children experience growing transition from childhood to adulthood.

The child motif and journey (quest) archetypes exist in mythology, fairy tales, and fables for thousands of years; still, they inspire and teach child readers about dealing with difficulties and dangers in their own lives. There are many literary archetypes used in literature that reflect the deep unconscious and behaviors of human kinds. The child motif is a common motif that can be recognized easily in most of children’s stories, in which the plots revolve around a child protagonist. As Jung maintains that “[the child motif] represents the preconscious, childhood aspect of the collective psyche,” this motif is one of the archetypes which often appear in children’s literature as a vestigial “memory of one’s own childhood” (161). A motif, according to Nikolajeva, “is a textual element—an event, character, or object—recurring in many works of literature” (Aesthetic 81).The child motif and journey (quest) archetype are the core elements of Coraline in which they offer a pattern for Coraline’s maturing transition through journeys of difficulties and trials. The greatness of this children’s fantasy story comes from its ability to illustrate an archetypal child to whom the reader can relate, bringing out the collective unconscious of the child archetype in the remembering of childhood.

Gaiman is a well-known fantasy writer who utilizes elements from fairy tale tradition and mythology in much of his writing, concerning primarily with encouraging the young protagonist to embark on a quest to a fantasy world, searching valuable treasure and self-fulfillment and probing on moral lessons at the same time.

In many children’s stories, child protagonists lack complexity, which means they neither undergo any changes nor develop much their characters over the course of a story. Often, they stay the same from the beginning to the end, showing no trails of improvement or change as typical flat characters would show. Nikolajeva points out

that those romantic heroes in the early children’s literature possess “a standard set of traits like heroic, moral, and loyal and so on. The premise for the romantic child hero is the idealization of childhood during the Romantic era, based on the belief in the child as innocent and therefore capable of conquering evil” (Power 18). While this assumption of the image of an ideal child can still be found in some contemporary children’s stories, more and more children’s fantasy stories would portray their child protagonists’ weaknesses as well as strengths rather than their invincibility. Coraline, for example, is by no mean a flat character for she goes through psychological and moral changes during the course of her quest which makes her different from other protagonists in children’s stories. Readers can see a vivid image of a girl who changes herself and learns valuable lessons through her adventurous journey, manifesting the humanitarian ideals attributed to both the development and complexity of her character. The story of Coraline demonstrates the concept of what Jung calls the

“invincible child motif” constituted in the plot and embedded in sub-conscious of human minds.

Coraline, as the title suggests, illustrates a child’s archetypal figure in a

children’s fantasy story. In Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers, Nikolajeva claims that the conflict between adults and children has always

been prominent motif in children’s fiction (78). Right at the beginning of Coraline, the story features a conflict between Coraline and her parents. Gaiman uses Coraline and her parents’ moving to a strange old house as causes to unfold the story. Gaiman then hints Coraline into her exploration of the other side of the wall of the old house to start on her adventures.

Coraline’s conflicts revolve around herself and both her real parents as well as the other parents. Her battle between good and evil, in a sense, is less disturbing in the setting of the alternative world than in the realistic environment, for it allows readers

to experience it vicariously through a narrative distance. Her acting like the girl next door impresses child readers when comparing themselves with her. Moreover, readers witness Coraline’s struggle between good and evil and this battle is not only psychological but also moral, as readers can see that Coraline has to make choices between good and evil as the story progresses. More importantly, many valuable lessons such as kindness, bravery, understanding and honesty are slipped into the story to lead her growth, and she can only triumph and experience character growth by her own choices and actions during the course of her quest.

It can be suggested that Gaiman knows well that the best way to educate children is by writing them an exciting story, and it would be a flop if it didn’t have any difficulty and opposition toward the goal. When the other parents lure Coraline into staying with them forever with fancy toys and delicious food, she manages to make correct decision which saves herself, her parents, and three ghost children out of the other mother’s control. Yet, she doesn’t come mature all at once. She develops her character and learns about herself, other people and life gradually through her adventures, and these make her story plausible.

Gaiman creates Coraline as a child character whom child readers can identify with, and encourages them to engage in her adventures. As a children’s fantasy story, Coraline helps child readers deal with their own problems in the real life. While

Coraline solves her problems in the story, readers can learn about how to solve their problems in life, and make difference. This is what Gaiman hopes for, and he doesn’t think “Disney cartoon fiction” type of story can help children handle the situation mentioned above. In his interview for Q (a Canadian radio show) in 2009,2 he said:

2 Transcribed by Karen Pei-Han Lee from Gaiman’s interview on CBC’s Q, an arts, entertainment and culture show on Canada’s public broadcaster. See more details on “No real controversy over scary kids tale Coraline, author Gaiman says.” CBCnews.

I think of is Disney channel cartoon fiction. […] You watch it hoping for some kind of story, and the story you get is something like somebody thinks they haven’t been invited to a birthday party but actually they have. It’s not the story that tells kids that dangerous things can be overcome. Tell them that you can go out and dream. Tell them that you can go out and change the world. (Q n.pag.)

Gaiman portrays Coraline’s psychological and moral developments in the middle of crisis rather than her chronological changes of age or physical appearance, making the plot not just revolves around a battle between Coraline and the evil forces, but also around moral lessons she learns as she struggles through it. Like many other contemporary children’s fantasy novels, Coraline makes its protagonist ordinary in the real world, and then empowers her when she is brought into the magic world. The odds are not in Coraline’s favor at the beginning of her adventures, and she is never a child heroine who possesses supernatural powers or any special ability. In his interview, Gaiman also mentioned what kind of heroine he wanted Coraline to be in the story:

When I went into Coraline that was what I held onto, and I thought, “I’m gonna make my villain as bad a villain as I can. I’m gonna make her dangerous this thing. I’m not gonna give Coraline magic powers, and I’m not gonna make her some kind of special chosen one and she’s not gonna be a secret princess or anything like that. She’s going to be a smart little girl who is going to be scared, and who is going to keep doing the right thing anyway, and that’s what brave is, and she is going to triumph by being

smarter then and braver.” (Q, n.pag.)

As Gaiman mentioned, Coraline’s strength, bravery and wit come from within, and she learns to overcome obstacles through her own experiences and the knowledge she amasses during her adventures. She is not a naive princess type of girl, who is passive and docile.

Due to prejudice and gender stereotype, the female characters in past children’s literature tended to be docile and passive and there were not many strong-minded and resourceful female characters in it (e.g., Becky in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer;

Flopsy, Mopsy and Cotton-tail in The Tale of Peter Rabbit). Those children’s stories were mostly about boys who were chosen to accomplish some sorts of goals or tasks designated by some mystical force or destiny. As Diane M. Turner-Bowker observes:

For many years authors of children's literature have portrayed females with narrow characteristics. They are often secondary characters; are regularly found in domestic settings; and are often in need of rescue by male characters. Male characters are also presented in stereotyped roles, but these roles are positive and sought-after. For example, boys and men more often serve in central roles (as protagonists); are portrayed as leaders, decision-makers, and heroes; and are often involved in occupations and roles outside of the home. (463)

Nowadays, many female characters in children’s literature are portrayed to be intelligent, brave and strong as the chosen ones to perform different tasks alone or work with male characters to solve problems (e.g., Lyra in His Dark Materials

Trilogy, Hermione in the Harry Potter Series, and Violet in A Series of Unfortunate Events). As Nikolajeva observes that “[i]n most fantasy novels for young readers,

there is a prophecy about a child who will overthrow the established order of an evil ruler” (Power 42), Karen Coats makes a similar observation:

messianic children’s fantasies operate according to this principle: children are identified as saviours through prophecies or as possessing some special quality that sets them apart from the norm and makes them the only ones who can solve the mystery. (The Routledge Companion 81)

The child archetype as a motif engraved so deeply into children’s fantasy stories that the child protagonists are destined to perform a difficult task in order to save everybody out of perils and advance their psychological and moral growth at the same time. Why such children’s fantasy stories have such an intriguing appeal to child readers may result from the emotional connection between readers who relate themselves and the heroes in the stories.

Those messianic child heroes all share a certain set of characteristics: they are curious, bold, sympathetic and heroic (Nikolajeva, Mythic, 2000). Coraline features a child heroine to perform the difficult task alone. As Jung notes, “[t]he urge and compulsion to self-realization is a law of nature and thus of invincible power, even though its effect, at the start, is insignificant and improbable. Its power is revealed in the miraculous deeds of the child hero” (171). As Gaiman says that he doesn’t intend to make Coraline “some kind of special chosen one or a secret princess,” but she possesses the typical features that a messianic child heroine usually possesses, and there is no one else but her who can save everybody out of the other mother’s clutches

and set the ghost children free. If it wasn’t her, those ghost children would have no chance to escape from the witch’s control forever. Coraline doesn’t possess any special talent and she learns to cope with her problems with others’ help, and the experiences and knowledge she gathers during her journeys. Her adventurous spirit leads her into the murky passage behind the small door, and enters into an uncharted area, while most children would have avoided touching the small door that opens onto the wall and made a run for it. She has the quality of bravery and curiosity that an explorer usually has before stepping onto an unknown land that signifies a new stage of life.

The child motif has a special place in the imagination of human unconscious.

The employment of the motif in Coraline can be seen as the embodiment of the motif.

The human desire to explain the child motif constructed in the archetypes of stories has been passed down from generation to generation, representing something that lies down deeply into human’s collective unconscious and has existed both in the distant past and the present. The child motif is timeless and prevalent in children’s literature as it can be seen vividly in Coraline that provides readers with an image of a girl whose journey is associated with fear and anxiety, two folkloric motifs constructed in the story.

Fear and Anxiety

H. P. Lovecraft states that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and that the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown” (12). Fear and anxiety are two folkloric motifs often employed in children’s portal-quest fantasy

stories as a way to attract young readers. Children love to seek fear through fantasy stories, in which writers distort reality in ways both frightening and startling to produce emotional and psychological effects in readers. Coraline sets in Britain, where ghost stories and haunted locations have circulated for thousands of years, and where many old and deserted houses have become popular tourist sites, through their association with paranormal activities.

In contrast, home is generally considered a safe place, and is therefore identified with the “canny” or the homely impression of familiarity as Freud points out. Home is the setting for Coraline and the location is old and subject to haunting. A haunted setting plays a crucial role in creating the eerie atmosphere of Gothic fantasy. The narrative of Coraline, revolving around the supernatural and the monstrous, is structured around numinous elements: the presence of monsters and ghosts, uncanny settings, and a mythical atmosphere. In Coraline, Gaiman employs the motifs of fear and anxiety within the security of home. Aside from Coraline, fear and anxiety also play two large roles in other children’s portal-quest fantasies—where the Queen of Hearts wants to behead Alice’s head (Carroll, 1995 [1865]),3 Voldemort threatens Harry Potter’s life (Rowling, 1997),4 and the Wicked Witch of the West seeks revenge against Dorothy and her friends (Baum, 1999 [1900]).5 Many writers, nowadays, still prefer to create a fear-free and trouble-free childhood for children in children’s literature, though the creation is far from truth.

Bruno Bettelheim, however, has different thoughts, and places emphases on childhood experiences in psychological growth. He sees overcoming fear and anxiety as an important process in children’s growing development for, with moral, fairy tales

3 See Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

4 See Harry Potter series.

5 See The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

(fantasy stories) have the capacity to not only captivate child readers but also enrich their lives, rendering themselves useful in children’s psychological education. In The Uses of Enchantment, Bettelheim points out that young children often cannot express

their feelings of fear or anxiety in words, and even older children sometimes would keep their true feelings inside. He suggests that fairy tales are children’s stories that can

hold the child’s attention; entertain him and arouse his curiosity and enrich his life; stimulate his imagination; help him to develop his intellect, and to clarify his emotions; give full recognition to his difficulties, while at the same time suggesting solutions to the problems which perturb him. (5)

Bettelheim states that fairy tales as fantasy stories help young children deal with their emotions and express their fear and anxiety because through considering what the stories seem to hint, child readers may find solutions to their own problems in real life.

Furthermore, the integration of psychoanalysis further helps study the relationships between children themselves and people in their surrounding environment. Nina Mikkelsen makes a similar observation: “Fantasy helps children explore new worlds far from home through adventures that involve risk-taking and danger, and it allows them to explore disturbing questions from a safe distance” (178). This distance enables children to probe into problems and issues without getting themselves into them. Both Bettelheim and Mikkelsen recognize children’s fantasy stories as useful tools for children’s education and examine their reading benefits.

It is easy to ascribe Coraline and other children’s fantasy stories’ popularity to the combination of fantasy and adventure, or children’s fascination with magic. To

child readers, part of the attraction of this subgenre is that it introduces places and ideas different from their own. Like many contemporary children’s fantasy stories, Coraline portrays its protagonist’s dilemmas by taking the issues of fear and anxiety

seriously, which in a way to help offer solutions to children. What Coraline achieves in the realm of children’s literature are: developing a sense of wonder in child readers, helping them find meanings in the story, and finally dealing with their own problems in daily life. When it comes to teaching children about the meaning of life, fantasy stories are better than realistic stories in describing psychological or emotional problems because they allow child readers to imagine what’s being described in the text from a safe distance, and this enriches their textual engagement, as well as real-life experiences and knowledge. As Deborah O’Keefe suggests, “[s]tories, particularly fantasy stories, teach people how to ‘subjunctivize’—how to go beyond their personal selves and the actualities of their everyday reality, and explore all kinds of human possibilities” (20).

Fear and anxiety are two common motifs often constructed into children’s stories, which are not only appealing to child readers but also educative. It was a tradition that the grim didactic moralism permeated the text of traditional Victorian children's literature in which the emphases of faith, morality, humility, and sacrifice along with the mixture of the fantastic and reality could easily be seen. As Anita Moss notes,

In Victorian England one of the most pervasive forms of children’s literature was the moral tale, often cast from the 1830s in the mode of literary fairy tale. Many writers of these didactic fairy tales […] often

profess to believe in the imagination, fairy tale, and liberated possibilities for children; yet they give in finally to explicit moral didacticism. (47)

It’s worth noting that the influences of Victorian didactic moralism can also be found in Coraline, and the moral lessons for a bored and curious girl remain as strict as any traditional Victorian writers would have penned.

Sometimes the inspiration of writing a story comes as a surprise. In his interview, Gaiman revealed that the main plot in Coraline was in fact inspired by his oldest daughter Holly who often came up with gruesome stories when she was five years old:

She would make me write down her stories, which were always about little girls being kidnapped by evil women, witches normally, who would disguise themselves as her mother. They were wonderful. I initially thought I should go and find some of these things and read them to her because she’d like it. Then I realized there wasn’t anything like that on the shelves.

So I started to write one. (Q n.pag.)

The other influences on Coraline can be traced to the two stories that inspired Gaiman’s writing. In his interview for Booklist in 2002, Gaiman acknowledged the two major influences on Coraline are Lucy Lane Clifford’s “The New Mother” and Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (Goss 2009); and between the two,

“The New Mother” is the primary influence (Coats 2008; Sleight 2009; Buckley 2010). Given the fact that both stories have similar Gothic setting, grotesque elements, literary characters and didactic nature, and are both infused with psychological sophistication and emotional forces, there’s no doubt that Coraline is Gaiman’s new translation of “The New Mother” (Buckley 2010) .

“The New Mother” tells a grotesque story of two sisters Blue-eyes and Turkey who live with their mother and a baby sibling in the forest. One day the mother asks the girls to check a letter from their absent father at the post office in the nearest village. There they meet an urchin girl who tempts them by telling them that there are two miniature people in her pear-drum, and she will give it to them as a gift if they behave naughtily at home. To get the gift, the girls behave naughtily and do not listen to their mother’s orders. Disappointed and sad, their mother leaves home with tears and sends a monstrous new mother with glass eyes and a wooden tail to replace her.

There are many similarities between “The New Mother” and Coraline, and one is that they both set up an opposition of order and disaster. The child protagonists from both stories are tempted by curiosity and desire, and eventually are punished for being curious and naughty toward their parents’ orders. Blue-eyes and Turkey keep annoying their mother for the promise gift from an urchin girl that eventually leads to their mother’s abandonment and the arrival of the monstrous new mother: “I should have to go away and leave you, and to send home a new mother, with glass eyes and a wooden tail” (Clifford 80). They hence flee away from home in terror, and live alone in the woods.

As a part of human nature, children are strongly tempted to do what is forbidden to them, even though sometimes they do foresee something unpleasant might happen

to them. Our heroine Coraline is no exception. At the beginning of the story, Coraline’s loneliness permeates the narrative. Child readers would understand Coraline’s anger at being neglected by her parents, and her boredom for having no friends due to just moving into a new neighborhood, and the subsequent curiosity and adventurous spirit she develops that drives her to visit the other side of the old apartment:

Coraline stopped and listened. She knew she was doing something wrong, and she was trying to listen for her mother coming back, but she heard nothing. Then Coraline put her hand on the doorknob and turned it; and, finally, she opened the door. (Coraline 26)

To Coraline’s surprise, behind the door there is a murky passage that mystically leads to a fantasy world. Once the door is open, the space becomes surprisingly hermetic and intriguing waiting for her to explore. When Coraline visits the other world, she’s indulged by the other parents with delicious food and fancy toys. However, there is no such thing as a free breakfast, and it always comes with a price.

The other parents want Coraline to stay with them in that magic world forever, and the first thing she has to do is let the other mother take away her real eyes and sew buttons on her face. The button eyes play a gruesome role in Coraline in evoking fear and anxiety and symbolizing the threat of losing soul. In his perceptive portrayal of Coraline’s first encounter with the supernatural beings in the alternate world, Gaiman personifies her nemesis as a mirrored representation of her real mother, a horrifying monster who replaces children’s eyes with buttons and imprison their souls.

As Gaiman talked about this role in his interview:

The other mother is not actually her mother at all. It’s this creature, the beldam which is an old word for a witch who just lives in this tiny pocket dimension6 and tries very hard to entice children in, and has something to love as almost as pets, and maybe something to eat as well. (Q n.pag.)

It’s worth noting that “The New Mother” and Coraline share themes like magic, curiosity, malicious temptations, the witch-like mother, punishments, as well as moral lessons for protagonists to learn as they struggle through the plots. Moreover, the grotesque imagery of the other mother employed in Coraline is similar to “The New Mother” in many ways: they both appear to be non-humans and evil. Neither the new mother nor the other mother has real eyes;and while the new mother sees things through her glass eyes, the other mother, buttons.7 Furthermore, girls in both stories are not endowed with magical powers to fight against the evil forces. While the two sisters have to put up with the negative consequence of their wrongdoings, Coraline is able to see through the other parents’ malicious intention, and escape from the dire fate luckily.

Both stories are cautionary tales with a didactic and grotesque nature. It would seem, in this comparison, that both “The New Mother” and Coraline are borrowing themes from Victorian gothic traditions that contain both grotesque contents and didactic moralism. Anita Moss points out, “[i]n Victorian England one of the most

6 Pocket dimension refers to a dimension that exists within another dimension. The pocket dimension contains time, energy, space and matter. In Coraline, the pocket dimension as fantasy world exists within the real world and it is dependent on the real world which it’s connected with to stay stable.

7 The symbolic meaning of the grotesque image of non-human eyes employed in both “The New Mother” and Coraline are discussed in more details in the following chapters.

pervasive forms of children’s literature was the moral tale, often cast from the 1830s in the mode of literary fairy tale” (47). Anna Krugovoy Silver suggests that

“The New Mother” has much in common with other nineteenth-century children’s literature, in which fantasy often serves as a vehicle for moral lesson. […] its employment of grotesque imagery and didactic structure […]

create frightening supernatural scenarios in which monsters teach disobedient little girls manners and morals. (728)

The ideology of Victorian moral lessons is that children should obey and listen to parents’ orders for parents are the ones who demarcate boundaries, set up rules and expect children to follow. Silver also suggests that

Clifford’s story falls within the Victorian genre of didactic fairy tales, in which writers use fantasy to maintain social norms rather than for anarchical, revolutionary, or socially progressive ends. Many children’s writers of the nineteenth century tucked moral lessons within the entertaining context of fairy tales and fantasy. (738)

Gaiman is a fantasy writer descending from Lucy Clifford and other Victorian writers, who uses grotesque fantasy stories to teach children moral lessons. Like Clifford and

other Victorian writers, Gaiman challenges the notion that childhood is a trouble-free period of time in one’s life, shielding children from scary stories or the harshness of real life, especially during one’s maturing development. Silver mentions above that,

“The New Mother” is a fairy tale to “maintain social norms rather than for anarchical, revolutionary, or socially progressive ends” while tucking “moral lessons within the text” (738). Gaiman’s Coraline also tucks on moral lessons within Coraline’s adventurous journey, and portrays her psychological and moral developments at the same time. The difference between the two stories is that, the two sisters in “The New Mother” are offered temptation, while Croaline’s temptation seems to come from within herself subconsciously due to the reason that she is often ignored by her busy parents at home.

Nikolajeva, on the other hand, states that Gaiman’s Coraline is a dialogical response to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland with similar characters and plots, such as a girl protagonist, doors and keys, mirror, murky passages, weird people and cat (Power 164). It should be noted, however, that these two stories exhibit two different attitudes and approaches toward intimidation and fear. Gaiman fashions his own version of the Alice story in which he brings a different perspective towards the plot and purpose of it. In Coraline, the desire of exploration, a prevalent theme in children’s fantasy story, is converted into a bad dream. While Alice can wake up comfortably from a horrid daydream, nightmare stalks Coraline until it takes place in her world (Power 164). Tolkien suggests that “the ‘dream’ element is not a mere machinery of introduction and ending, but inherent in the action and transitions. These things children can perceive and appreciate, if left to themselves” (75). Coraline corresponds with Tolkien’s saying, for it is neither a “dream-frame” novella,8 in

8 The term “dream-frame” here refers to the term that Tolkien defines in his essay "On Fairy-Stories"

in which he states that the dream-frame device doesn’t take fairy tales seriously. He categorizes Alice’s

which the child protagonist undergoes many adventures, only to wake up and find it has all been a dream, nor a fairy story, which retains something of “lightness.”9 Instead, the plot becomes thicker and deeper as Coraline’s adventures progress. When she takes on the challenge to explore the strange new world, she faces dangers and suffers from the threat of death, making her aware of her own defects.

In Alice, fear is evoked but unrelieved, and scariness is more like intimidation than actual fear, while in Coraline fear is explored and relieved at the end of the story.

The latter’s conclusion shows the relief of a happy ending through Coraline’s having defeated the monster, mastered her own fear, and learned moral lessons. When child readers read the story, they might link Coraline’s experience to their own real-life experience, trying to figure out the ways to solve their problems.

Maurice Sendak also thinks that fantasy helps children learn to overcome fear and anxiety. When winning the prestigious Caldecott Medal for his picture book Where the Wild Things Are in 1964, Sendak gave his speech:

What is too often overlooked, is the fact that from their earliest years

children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, that fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday live, that they continually cope with frustration as best they can. It is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming the Wild Things.

(qtd. in Griswold 44)

Sendak takes a positive attitude toward the depiction of fear and anxiety in children’s

Adventures in Wonderland as a dream story that uses dream-frame logic and sequences to make the story surrealistic.

9 Children’s stories often deal with the problems faced by protagonists in a surrealistic narratives and lighthearted tone.