跨學科教師發展統整課程之個案研究

摘 要

這個研究的目的是要藉由檢視不同領域和語言的小學教師共同創造統 整課程的過程來對教師專業發展做建議。研究的問題是在職教師如何發展統 整課程。研究資料包括教師的團體討論的錄音帶(以逐字稿呈現)、教師的 檔案夾(收集了教師所有課程設計和研究中所產生文件等資料 )、研究者的 省思札記。研究發現教師發展課程統整的過程包括教師尋找焦點,做連結和 預設課程。研究發現從教師的角度來建構課程統整是與課程統整的學者定義 的課程統整內容和過程是不同,課程學者和專家能夠了解並尊重教師在課程 統整的能夠使用自己的詮釋、連結和願景,並尊重教師能夠發展屬於自己統 整課程自主權。在這基礎上,專家學者和教師可有更好的合作和結果。

關鍵詞:統整課程、跨語言課程、跨科際課程、教師專業學習社群 曾月紅

國立東華大學英美語文學系教授

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the processes of how elementary school teachers from different disciplines (language arts, social studies, art) and from different languages (English or Chinese) co-created an integrated curriculum, and to provide the suggestions for teacher professional development. The research question concerns how in-service teachers developed an integrated curriculum. This study’s data are of three main types: (1) audio tapes of teacher study-group conversations (in transcript form), (2) teachers’ portfolio (which collected teachers’ curriculum and artifacts generated from the research), and (3) reflection entries from my reflection journal. Findings suggest that the processes of teachers integrating curriculum were “searching the focus,” “intertextualizing,”

and projecting. In addation, teachers were successful in creating an integrated curriculum when they were able to use their own interpretation, connections, and vision. Findings also suggest that the teachers’ construction of an integrated curriculum is different from that of academics. Academics and other experts should allow teachers to use their own interpretation, connection and vision, and respect their autonomy. With that foundation, academics and teachers can collaborate with fruitful results.

Keywords: integrated curriculum, inter-language curriculum, interdisciplinary curriculum, professional learning community of teachers

Yueh-Hung Tseng

Professor, Department of English, National Dong Hwa University

A Case Study on Interdisciplinary Teachers Developing an

Integrated Curriculum

The purpose of this study was to investigate the processes of how elementary school teachers from different disciplines co-create an integrated curriculum, and to provide the suggestions for teacher professional development. The research question concerns what the processes of in-service teachers co-creating an integrated curriculum are. Examination of these processes can give suggestions to teachers’ professional development. In the following, the definition of integrated curriculum will be first introduced, followed by review of literature, theoretical framework, methods and findings.

For the purpose of this study, ‘integrated curriculum’ refers to units of study that are interdisciplinary. As such, creating an integrated curriculum is a movement against the notions of both segmented content and segmented learning, notions that disciplines create.

“The disciplines sometimes serve as blinders rather than lenses, limiting vision rather than enhancing it” (Tchudi & Lafer, 1996, p. 7). For this study, ‘interdisciplinary’ is defined as

“a knowledge view and curriculum approach that consciously applies methodology and language from more than one discipline to examine a central theme, issues, problem, topic, or experience” (Jacobs, 1989, p. 8).

Those who advocate an integrated curriculum (Fogarty, 1991, 2002; Beane, 1997;

Jacob, 1989) focus on the richness of the content that can be addressed rather than the process teachers must go through to create an integrated curriculum. Fogarty (1991), for example, suggests that curriculum can be integrated within a particular curricular area, across curriculum areas, or even across and throughout various school years. Integration throughout the school years is a vertical integration in which “mastery of certain material is expected at each level in preparation for building on that mastery at subsequent levels”

(Fogarty, 1991, p. xiii). Fogarty goes on to state that, by contrast, horizontal integration represents the exploration of a given subject in breadth and depth. Integration across the curriculum is defined as “the integration of skills, themes, concepts, and topics across disciplines as similarities are noted” (p. xiii). He states that holistic learning takes place as students connect ideas among subjects. Beane (1997) presents curriculum integration in terms of experience, values, knowledge, and design. “New experiences are integrated into what we already know and past experiences are ‘integrated’ to help us solve new problem situations” (Beane, 1997, p. 4). “Social integration” promotes “the development of a common set of values” (Beane, 1997, p. 5) by forcing those who work together to come to a common set of understandings. “Integration of knowledge” refers to “a schema-

theoretic notion of knowledge in terms of how it is organized and used” (Beane, 1997, p. 7).

Isolated bits of information that are not connected to other knowledge structures are seen as worthless or as not having been learned. For Beane (1997), integration as a curriculum design refers to “a particular kind of curriculum design,” in which curriculum not only is organized around problems and issues relevant to learners’ lives, but also emphasizes the interconnectedness of experience, values, and knowledge.

The curricula that specify contents required to be integrated are pre-determined.

Drake (1998) introduces several approaches of integrated curriculum—multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary curriculums—which vary according to the degree of integration and connection of disciplines. In a multidisciplinary curriculum, “the disciplines are connected through a theme or issue that is studied during the same time frame but in separate classrooms” (Drake, 1998, p. 20). Disciplines in interdisciplianry curriculum are connected beyond common themes, such as guiding questions or a conceptual focus (Drake, 1998). In a transdisciplinary curriculum, the planning process focuses on “real- life contexts” rather than specific disciplines (Drake, 1998). For example, a social issue or a real-life problem, such as “water,” will be the organizing theme of the curriculum (Drake, 1998). Loepp (1999) presents several models for an integrated curriculum:

interdisciplinary, problem-based, and theme-based models. Interdisciplinary curriculum refers to curriculum in which the school groups traditional subjects in a block of time, and teachers from various subjects team together to teach students this set of knowledge (Loepp, 1999). In problem-based curriculum, the learning- or curriculum-content problem is the focus (Loepp, 1999). Different teaching disciplines point to the problem and use different disciplinary approaches to solve the problem posed (Loepp, 1999). In theme-based curriculum, given themes or concepts are identified and explored from the perspective of various disciplines (Loepp, 1999). Within this last construct, discussions on integration of various subjects are undertaken, such as integrating art in a non-art curriculum (Appel, 2006). For example, drawing and painting are related to geometry and the physics of spatial design (Appel, 2006).

This emphasis on curricular integration as the integration of content cuts across all curricular areas. In the area of foreign-language teaching, for example, “content-based instruction is a method of teaching foreign languages that integrates language instruction

with instruction in the content areas. In this approach, the foreign language is used as the medium for teaching subject content, such as mathematics or social studies, from the regular classroom curriculum” (Curtain & Haas, 1995, p. 1). Content-based integration has been further categorized into total or partial immersion programs. The former uses a second language in all curriculum, and the latter uses the second language in part of the curriculum (Curtain, 1986). Immersion programs offer “complete integration of elementary school content and foreign language instruction because the elementary-school curriculum is the immersion curriculum” (Curtain, 1986, p. 19). In this context, children are taught to be bilingual at a young age.

In addition to the above immersion program, the integration of foreign language and content into each other proceeds through “identifying points of coincidence” (Met 1991, p.

284). Using this conceptualization, foreign-language learning’s objective is comparable to the objectives in the core curriculum content (Met 1991). In this context, skills and cultural knowledge can then be taught coinciding with objectives of the content area, such as the topic of family in social studies (Met, 1991). Alternately, the objectives of language at a given level are identified, and then the curriculum content is organized in content areas for instruction relative to these objectives (Met, 1991). From Met’s point of view (1991), for example, colors that are taught in a foreign language are therefore taught in other content areas (and the number and the weight of colored candy in mathematics or physics, for example). Finally, Curtain’s model (1986) presents content-enriched FLES (foreign language in elementary schools), in which teachers reinforce the use of foreign language in other disciplines.

In contrast to these theoretical models, Jacobs (1989), and Etim (2005) offer methods for how to integrate curriculum. Jacobs (1989) proposes a “step-by-step” approach. He explains all the steps as the following (Jacob, 1989). This “step-by-step” approach first involves the teacher selecting an organizing center (a topic, issue, or event) that serves as the focus. Next, the teacher brainstorms about the connection between the organizing center and various disciplines. The third step is for the teacher to organize the associations among the disciplines, and to set up guiding questions. The fourth step is to write up the activities that will be implemented in the class (Jacob, 1989). Etim’s integration model (2005) offers eight different steps of content integration, entailing brainstorming for the

themes, teachers’ selection of the themes, decisions made with student input, decisions regarding the time frame for a unit, writing out the objectives and the requisite skills, implementation of the content integration, culminating events, and evaluation/access. All of the above are prescriptive procedures with predicted result.

The above themes concern chiefly writing about integrated curriculum, drawing on current theories of learning and teaching, prescribing content, and systematically integrating curriculum. Less frequently suggested is the process for integrating curricula.

The purpose of this study was therefore to investigate the processes of how teachers from different disciplines co-created an integrated curriculum.

Available studies on curriculum integration from teachers’ perspectives focus on interdisciplinary teaming in middle grades involving the creation of community for learning in school, ways to implement teaming, organize teachers’ meetings, and assigning duties to participants (Flowers, Mertens, & Mulhall, 1999). Other studies involve the effects or outcomes of interdisciplinary teaming (Flowers, Mertens, & Mulhall, 1999; Jang, 2006). Flowers, Mertens, and Mulhall (1999), for example, found that teaming creates a more positive work climate.

Since educators have proposed integrated curriculum on the basis of learning theories, this study of curriculum-integration methods presents both knowledge and suggestions of these processes in order to enhance the design of effective programs for professional development. This paper’s stance on an integrated curriculum involves the following theoretical framework, which illustrates learning from several perspectives.

Theoretical Framework

The study is grounded in semiotics theory of learning, and theorists for integrated curriculum. Learning is integrated for several reasons. First, cognition is interconnected.

According to semioticians like Peirce (1931-1960) and Eco (1984), cognition functions as an interconnected whole. In addition, brain functions connect patterns automatically. As to how the brain works, Caine and Caine (1991) state that “the search for meaning occurs through patterning” (p. 81), on the basis of which the brain makes automatic connections.

Forgarty (2002) drew on research from Caine’s principles as his theoretical background for integrated curriculum. As the brain makes automatic connections and functions as an

integrated whole, it is therefore difficult to separate cognition into parts.

Second, learning is the united whole connecting our environment and our experience to each other. Smith (1986) states that “children learn by relating their understanding of the new to what they know already, in the process modifying or elaborating their prior knowledge” (p. 90; see also Smith, 2004). Beane (1991) also made the same claim:

“Genuine learning involves interaction with the environment in such a way that what we experience becomes integrated into our system of meanings” (Beane, 1991, p. 9). We learn by interconnecting things to our own existing experience (knowledge or life experience).

Third, learning is a united whole and it cannot be separated from context and purpose (Murdoch & Hornby, 1997) and meaning (Caine & Caine, 1991; Beane, 1991;

Barton & Smith, 2000). “Knowledge, skills, attitudes and actions are integrated toward common purpose” (Murdoch & Hornby, 1997). Caine and Caine (1991) state that brains are searching for meaning, and cannot stop. Drake (1998) expresses the assertion that experiences are connected in meaningful ways. Content of integrated curriculum should be meaningful (Barton & Smith, 2000).

The above rationales regarding how students’ learning occurs are the foundations for integrated curriculum. The above learning theories, as I have assumed, work for teachers who are learning to use an integrated curriculum as a learning process; I’ve also assumed that these learning theories are applicable to teachers while they are integrating curriculum. I therefore assume that teachers generating integrated curriculum might use their own personal experience (knowledge and personal experience), their own purpose, and personally relevant meaning. In this regard, I am interested in examining the processes of how teachers co-created the integrated curriculum.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the processes of how teachers from different disciplines co-created an integrated curriculum, and to provide the suggestions for teacher professional development. The research question is: what are the processes of in- service teachers co-creating an integrated curriculum?

Methods

In order to investigate how teachers generate an interdisciplinary curriculum, I began the present study by inviting three elementary school teachers who taught different

disciplines (language arts, social studies, art) in different languages (Chinese or English) to organize a study group and to collaboratively create an integrated curriculum.

I used case-study methodology, as case studies are the appropriate design for examining phenomena in context (Yin, 1994, in Merriam; Titscher, et al., 2002; see also Tseng, 2003). The data for the current study’s research were collected between 2002 and 2003; the research was sponsored by the National Science Council of Taiwan.

Three in-service teachers participated in the study group: two main-room teachers and one English-language teacher. Among them, one main-room teacher (Cheng-Yu) and the English-language teacher (Li-Lin) were from the same school, while the other main- room teacher (Yin-Chung) was from another school. I knew Cheng-Yu and Li-Lin as I had worked with both of them together on designing alternative curriculum. Yin-Chung was my graduate assistant, and did not know the other two teachers before the study. In this research, these teachers and I (the team) generated a curriculum, and both Cheng- Yu (teaching Chinese and all disciplines) and Li-Lin (teaching English) actualized the curriculum in Cheng-Yu’s grade-one class. At one point, I joined their collaboration and taught English. In general, however, the main-room teacher in grade one taught most of the courses (namely, Chinese, social studies, and science). Among these teachers, Cheng-Yu had some experience with an integrated curriculum because her school had developed an integrated curriculum. Her understanding of an integrated curriculum was driven by topic- related activities. This paper’s stance on an integrated curriculum was illustrated in the theoretical framework above. All names used here are pseudonym.

The team met at least once a month over seven months (an academic year), for a total of nine meetings. Our conversations focused not only on curriculum but also on concerns and questions raised by the three teachers. In these sessions, we designed and actualized curriculum and then discussed the actualization. Each session was audio-taped. Teachers actualized curriculum in regular classes during fall and spring semester in 2002-2003 academic year. Eleven classes, for example, had been used to explore the topic of “knowing yourself.”

The data collected in this study included (1) audio tapes of teacher study-group conversations (in transcript form), (2) teachers’ portfolio (which collected teachers’

curriculum design and artifacts that generated from the research., and (3) reflection journal

entries from me. The principal investigator also recorded thoughts and insights regarding her observations and took field notes from classroom observations.

Data Analysis

I used qualitative-analysis procedures to analyze the data. These procedures are inductive (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; see also Tseng, 2003, 2010, 2011); I read, coded, and categorized (see also Tseng, 2003, 2010, 2011) in order to understand the processes involved in curriculum integration. In this way, theory would be grounded in data (Glaser

& Strauss 1967, cited in Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

All teachers’ notes and reflection journals were filed in different portfolio folders.

Audio-recordings were transcribed. I often asked teachers to clarify data. I read all transcripts, and teachers’ portfolio to understand the processes of how teachers integrated curriculum. Reflection journal was used as reference to verify the other data. While I read and coded the data, I recorded my insights in the previously mentioned reflection journal.

I then further reviewed the insights in order to identify patterns, and I further coded and categorized. I attempted to connect all of these patterns through a process of categorizing, an approach commonly used in qualitative studies (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, cited in Lincoln & Guba, 1985; also see Tseng, 2003, 2010, 2011). Patterns that I observed were shared with three teachers during and after data collection.

As patterns emerged, the data analysis was further guided by two major separated categories that emerged: “inter-language integration” (when teachers integrated Chinese and English into each other) and “interdisciplinary integration.” “Inger-language integration,” which involves two languages, is therefore different from integration of foreign language instruction (only one language) with instruction in the content areas. I would often engage in re-categorizing. Several categories were subsumed and then became the themes for the articles. Finally, I re-categorized the data according to new patterns emerged, which involve the time when teachers were seaching focus, intertextualizing, and projecting the contents as indicated later in this study.

Establishing Validity

The procedures that I used to establish validity in this research involved prolonged engagement, persistent observation, triangulation, member-checking, and peer-debriefing (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Creswell & Miller, 2000). It is clear that I undertook prolonged engagement and persistent observation insofar as the study involved a full year of research (from 2002 to 2003). I achieved triangulation in this study by drawing on multiple and varying sources, methods, investigators, and theories (Denzin, 1978, cited in Lincoln &

Guba, 1985, and in Creswell & Miller, 2000). The multiple and varying sources that I applied to this study comprised data collected from different methods of data collection:

observations, interviews, and reflections. For the current study, I established peer debriefing by engaging in research-oriented discussions with outsiders—colleagues in Taiwan and colleagues in the United States (for further discussion on establishing validity, see Tseng, 2003, 2010, 2011). In addition, I clarified patterns that I observed with three teachers during and after data collection.

The notational system used for referring to the different sources of data in this paper identifies the source and date (shown in parentheses), with the following abbreviations being used for the source: (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002) T=Transcripts, Hua-Lien = place where the discussion took place, and 11-22-02 = Time that the discussion took place (Month-Date-Year). (LP, Li-Lin, 12-20-02) LP = Lesson Plan, Li-Lin = the teacher’s first name. 12-20-02 (Month-Date-Year). For reference, the extract from the transcripts appearing in every section will be labeled 1.1, 1.2, and so on. The first number indicates section (for the purpose of location), and the second number is the sequence of the extracts appearing in the same section. The number in each line of excerpts was the number of original transcript.

Findings

The findings suggest that the processes of in-service teachers integrated curriculum involved “searching focus,” “intertextualizing,” and “projecting.” Although teachers had the educative aims of inter-disciplinary and inter-language curriculum, the aims were not fixed and were co-created. Teachers’ curricular choices and contents were also co-created through discussions.

Searching the focus

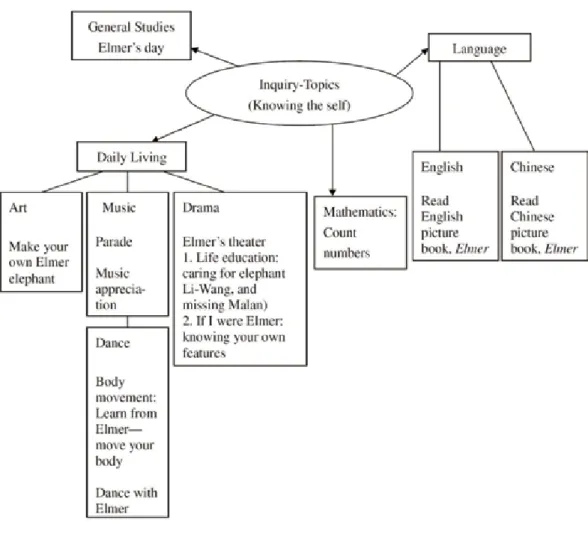

Teachers searching meaningful focuses of an integrated curriculum by stepping back and examining available resources. By searching the focus from the content, teachers made more connections than otherwise would have been the case. For example, in our first meeting (10-16-02), Cheng-Yu suggested that for the curriculum design, the team could first set up the topic for teaching, and that we could use the children’s picture book Elmer (McKee, 1968). Cheng-Yu and Li-Lin further abstracted topics of “knowing the self” from Elmer (McKee, 1968). The following transcriptions reveal how the topics surfaced. In Line 6, Cheng-Yu said that our topic could be “knowing the self.” The draft of our curriculum design showed the topic of “knowing the self” (see figure 1). [For figures 1 and 2, I translated the original Chinese-language web text into English].)

1.1

2.Cheng-Yu: We will first discuss this part.

3.Yueh-Hung: Could you discuss these two pages?

4.Cheng-Yu: Yes, this is from a format that Teacher Tseng gave us. Do we need to use this format when we design curriculum? And this other page is the framework of the topic.

5.Yueh-Hung: Framework?

6.Cheng-Yu: Yes, and I and Li-Lin have noted that our topic should be set up with a “knowing the self” theme. The subject of language can be divided into English and Chinese. (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

The topic was further extended to “be yourself.” Li-Lin described to us the story of Elmer (McKee, 1968) and how she had found the “be yourself” topic from the meaning of the children’s book.

1.2

125.Li-Lin: Elmer is originally an elephant with patchwork. Later on, he finds that if he picks plums from trees and then rolls around on the plums placed on

the ground, he then changes into the plum’s color; that is, he becomes the same gray color as the other elephants. However, he soon discovers that being gray adds no fun and is nothing special. It is better for him to be himself. We discuss the issue regarding the topic of “be yourself.” (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

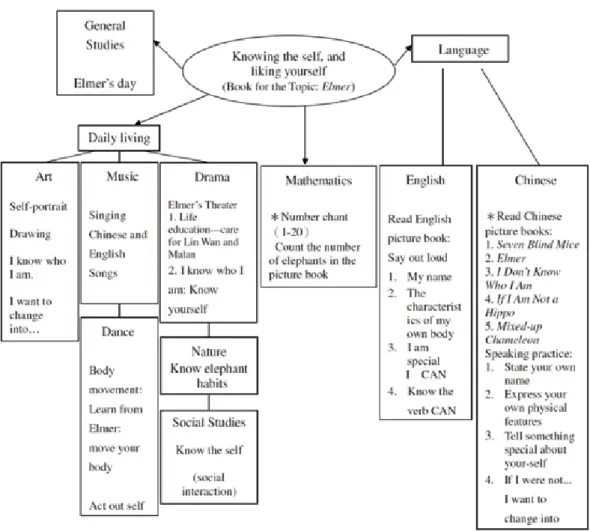

From the above, we understood that discussions allow us to constantly change the topics from “knowing the self” (figure 1) to both “knowing the self” and “be yourself”

(figure 2), and searched for the meaningful topics, from which our design of curriculum progress.

The topic served as a springboard from which we began to generate activities. For example, Cheng-Yu discussed the curriculum that she and Li-Lin had designed and that would invite students to explore the topic “knowing the self” (1.3). Cheng-Yu stated that students could engage in the activity of “knowing your own characteristics” (L 8). In addition, students would explore topics through various disciplines. For example, Cheng- Yu was trying to connect topics to various disciplines, such as language, mathematics, and daily-life practices (art, music, and drama) (L 8). At one point, she mentioned that we could have an Elmer theater, an Elmer life education, and an Elmer-related “knowing your own characteristics” (L8) project.

1.3

7.Yueh-Hung: Hmm ...

8.Cheng-Yu: We can start with the book about Elmer. We can connect the book’s topics to, for early grades, language arts, mathematics, daily living, and general studies. Daily living can be further divided into art, music, and drama.

The following is the draft for activities. For example, for drama, we can use the book to make an Elmer theater. Our activities can involve life education, and also “knowing your own characteristics,” and then music. We can have a parade of model presentations.

9.Yueh-Hung: A parade, oh.... (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

In addition, Yin-Chung began to design more activities and stated that students could make a “be yourself” elephant, could draw themselves (L 161) (1.4), could highlight their own features (L 161), and could play themselves. All of these activities related to the topic at hand.

1.4

161:Yin-Chung: ... Yes. An animal festival. If the topic is to know the self, then, I think, in art, you’re making a “be yourself” elephant. Do we ask them to draw an elephant? Can we ask them to draw a self? Could we ask them to draw the self and to highlight its own features? What are your features? And the students could highlight the features through drawing because we need return to the topic of the self.

162.Cheng-Yu: Know the self.

163.Yin-Chung: And then we can have a dance. In the beginning, we can learn about Elmer’s movements.... We can act out the self. So, we can go back to the self. (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

Cheng-Yu went into greater detail about how she would accomplish this instruction (1.5): she would let students learn about their own merits and shortcomings, or ask the other students to think about how the other would think about their own selves (L 344).

1.5

344.Cheng-Yu: Knowing the self...knowing your own merits and shortcomings, or knowing what the other children think of you. For example, suppose I am Cheng-Yu. The other students will ask, “What do you think about Cheng-Yu?”

And then you could listen to another person’s opinion about the self [you]….

And then, maybe I’ll talk first about what kind of person I am. I may brag that I’ve got a lot of friends, but the others will say, “No, no. I don’t like him. I don’t like him as my friend.” We’ll have an interaction with other classmates.

345.Yueh-Hung: What kinds of activities will you do?

346.Cheng-Yu: What kinds of activities will I do? Hmm….They’d be what I just talked about—let them do role playing about what kind of person I am. It’s like self-clarification. We’ll first talk about what kinds of situations I’m in. (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

Through topics, we designed activities that students, using two languages, would participate in. For example, in the first excerpt (1.6), Li-Lin mentioned that we could teach students both animals’ names and the animals’ characteristics, all in English (L 179) and all referring back to the topic of “knowing the self.” In the second excerpt, Cheng-Yu said that students could say something about their own features in English (L 426).

1.6

179.Li-Lin: We can teach...animals’ names. And then you [the students] would need to discuss your own features. You can introduce yourself to everybody, your names or characteristics....“I am tall” or “My eyes are big.”

180.Yueh-Hung: ... Yin-Chung just said that, during the dance segment, you can act out [play the role of] the self, or when they [the students] act out, you can ask them what they want to talk about, and they would write it in Chinese, and then you would write it in English.

181. Li-Lin: But in English, I think we shouldn’t let them write difficult words.

We could ask them to use some easy words. If you want to describe more things, and to do so in greater depth, you could use more Chinese.

182. Yueh-Hung: Yes. (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

1.7

425. Li-Lin: Eng…Don’t be in a rush.

426.Cheng-Yu: That’s better. What we could do for this semester is to comment orally about one’s own features and to know some corresponding common nouns in English … (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

From 1.3 to 1.5, Cheng-Yu noted that students could engage in “knowing your own characteristics” activities (L 8) (1.3). Yin-Chung suggested that students make a “be yourself” elephant, drawing themselves (L 161) (1.4), highlighting their own features (L 161) (1.4), and playing themselves. Cheng-Yu described how she would accomplish this instruction (1.5): let students know your own merits and shortcomings, or ask other students to think about how the other would think about you (L 344). The above talks were actualized in curriculum. In Chinese class (Cheng-Yu, LP 12/19/02 class 3-4), Cheng- Yu read Elmer to students, and asked students to talk about the styles of elephants, the characteristics of Elmer (L8) (1.3), what Elmer changed himself into, how Elmer changed, and the ending of the story. In the following week (Cheng-Yu, LP 12/26/02 class 6-7), in Chinese and daily-living classes, Cheng-Yu asked students to talk about Elmer and his characteristics. She then asked students to brainstorm about their own characteristics (such as I am tall, and I am fat) and students then drew self-portraits and wrote down and shared their own characteristics (L 161) (1.4), (L344) (1.5) (see appendix, which documented in details about how the lesson plans were actualized from 12/19/02 to 12/26/02).

From the above exchanges, we understand that topics, the conceptual focus, are generated through teachers’ investigation into available resources (in this case, for instance, the children’s book) and from teachers’ and students’ enacting of text and context. The group co-created the topic, which is meaningful and useful.

With the educative aims of inter-displinary and inter-language, the topic created further opportunities in which we could make connections among various languages and various elements of content. We generated inter-disciplinary and inter-language activities that would invite students to participate as teachers would extend more and more invitations to the students. In addition, through discussion, teachers would identify more and more activities that relate to the topic at hand.

Figure 1: Curriculum Design (First Draft) Designers: Cheng-Yu, Li-Lin (11/2002)

Teachers in this study met the requirements of an integrated curriculum for several reasons. First, when teachers in this study developed an integrated curriculum, they found a conceptual focus with which to begin. This focus, however, is not pre-determined, but is generated throughout the discussion. Second, the integrated curriculum is a united whole as it is connected to the context, purpose and meaning, as indicated in the theoretical framework. Caine and Caine (1991) stated that the brain incessantly searches for meaning.

(p. 18)

Figure 2: Curriculum Design: Webs of topics Designers: Cheng-Yu, Li-Lin (12/15/2002)

Intertextualizing

The teachers’ curricular choices and educative aims were co-created through making personal connection with various texts. The team also made connections through

“intertextualization.” “Intertextualizing is the act of using one text to interpret or make sense of another” (Harste, personal communication, 2002). According to Beaugrande,

“intertextuality is the process of interpreting one text by means of a previously composed text” (1981, p. 182, cited in Short, 1986, p. 4). “Intertextualization is the learner’s free association, and is a socio-psychological aspect of transaction between personal experiences and texts in context” (Tseng, 2003, p. 185).

Beaugrande focused on the intertextualization of linguistic texts, where a “text” is taken to mean any language production, whether printed or oral. Short (1986) provided a broader definition that included all sign systems. A text “could therefore be a piece of art or music, a drama, a dance, a conversation, or a piece of writing” (p. 4, see also Tseng, 1999a,b, 2000, 2001a,b, & Tseng 2003). From my previous study, I found that language learners intertextualize not only among printed texts but also between different sign systems (Tseng, 2003).

In this study, I also found that intertextualization opened up other opportunities in which teachers and students could make connections among languages and disciplines. In other words, through intertextualization, we extended the integrated curriculum that might be used in the class.

In the following, intertextualizations occur when teachers intertextualize among various printed texts, between printed texts and real words, or between printed texts and past experiences.

Intertextualizing among Printed Texts

Inter-language Connection. Teachers connected two languages (Chinese and English) to each other by intertextualizing two texts, a Chinese version of a children’s book and an English version of the same book, Elmer (McKee, 1968). Of the team, Cheng- Yu was the first to mention that, by using the shared text, Elmer (McKee, 1968), we could integrate the Chinese language and the English language into each other (L 78). To make a connection between the Chinese text and the English text, Cheng-Yu intertextualized them.

2.1

77. Yueh-Hung: Next time, next time, we can write a curriculum plan first and discuss it.... I would like to move you [the three teachers] toward interdisciplinary curriculum, but we could have something for next time, and then we could understand it little by little.

78. Cheng-Yu: Is that possible? Suppose that we can teach one children’s book.

Right now, I’m interested in the book Elmer, which is a big, big one. Maybe I can collaborate with Li-Lin. She teaches English, and I teach Chinese, and then we can extend ourselves into interdisciplinary teaching …

79. Yueh-Hung: I think it’s a good idea. When we teach the children, we may observe their responses. (T, Hua-Lien, 10-16-02)

In the context of intertextualization among printed texts with different langauges, Elmer (McKee, 1968) lent itself to possible teaching resources that teachers could use. In addition, the book also initiated the generation of the topics, as indicated in the previous section (1.1, 1.2), and activities (1.3-1.7). Intertextualization extended the possibilities for integrating curriculum. This intertextualization continued and enriched teachers’

curriculum. For example, in figure 2, in the section “Chinese,” teachers generated books for teaching, Seven Blind Mice (Young 1992), Elmer (McKee, 1968), You're a Hero (Blake, 1992) [Chinese title: I Don’t Know Who I Am], and Mixed-up Chameleon (Carle, 1988). All of the books have Chinese version.

From the account of the lesson it can be seen that Cheng-Yu read Elmer in Chinese (McKee, 1968) to students in a Chinese class (Cheng-Yu, LP 12/19/02 class 3-4), and in Chinese and daily-living classes (Cheng-Yu, LP 12/26/02 class 6-7), she asked students to talk about Elmer again and about his characteristics. She then asked students to brainstorm about their own characteristics (such as I am tall and I am fat). Students then drew a “self-portrait” and wrote down their own characteristics. Finally, students shared self-portraits with others, and reported their own characteristics. In English class the following day, (Cheng-Yu, LP 12/27/02 class 8; Li-Lin, LP 12/27/02), the “report your own characteristics” activity and the self-portraits were actualized. Li-Lin also described

appearances (such as tall, short, fat, thin, old, young) in English. Students shared with other classmates the self-portraits, and identified their own characteristics in English, such as I am___, I like my ___(from head to toes), and about a personal specialty, such as I can___(climb trees, kick a ball, swim, throw a ball) (see appendix for details).

The following is another example herein when we discussed another topic, I and the nature. I intertextualized Cheng-Yu’s Chinese-language children’s book about a tree (L 223) with another book, The Giving Tree (Silverstein, 1992), which is in English (L 224).

Li-Lin further intertextualized them with the Chinese-language version of The Giving Tree, and inquired about the Chinese wording in the Chinese-language version of The Giving Tree (L 242). Intertextualization helped create more opportunities in which we could identify various activities and make connections through various languages.

2.2

223. Cheng-Yu: [Regarding the classes for the coming semester], I will talk about observing the signs of spring. We could start with fruit from fig trees [or]

some plant. I then want to read several works of children’s literature, like 樹 真好 (Su Cheng Hao, The Tree Is Nice) and我真想有一棵大樹, (Wao Cheng Hsiang Yao Yi Ke Da Su, I Wish I Could Have a Tree). I Wish I Could Have a Tree concerns how children build their dreams in relation to a tree.

224. Yueh-Hung: Why don’t you read the book The Giving Tree?

225. Cheng-Yu: Very difficult. The Giving Tree is … 226. Yin-Chung: But it’s difficult.

227. Cheng-Yu: The Giving Tree is very philosophical.

228. Yueh-Hung: I meant in Chinese [not in English].

.. .

242. Li-Lin: What is the Chinese version of that book?

243. Cheng-Yu: 愛心樹 (Ai Hsin Su). (T, Hua-Lien, 1-20-03)

Connecting with Different Disciplines.

We discovered more ways in which we could invite students to learn, and we did so by intertextualizing various printed texts with one another. In the end, we designed more activities and made stronger connections among disciplines. For example, Li-Lin intertextualized the current text, Elmer (McKee, 1968), with the pictures in another printed text—Da Ke Sheh (Grand Science)—a science encyclopedia (L 242) featuring images of elephants. We were trying to undertake a rigorous “integration of knowledge,” as described by Beane (1997). We continue to discuss the books and the pictures that are in the books (2.4).

2.3

238. Li-Lin: I am an English elephant, and you are a Chinese elephant … then before we finish the story, we should have …

239. Yueh-Hung: Hmm …

240. Li-Lin:….We first teach the easiest subject matter. Cheng-Yu has subscribed to Da Ke Sheh [Grand Science]

241. Yueh-Hung: Oh!

242. Li-Lin: Da Ke Sheh features beautiful pictures….

243. Yueh-Hung: Pictures of elephants? (Cheng-Yu: they’ve got all kinds of animals [pictures of animals]) (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

244. Li-Lin: [You read the passage to the kids] You can let the kids listen to Da Ke Sheh and then bring animal pictures in. (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

2.4

263. Yueh-Hung: Wait a minute. What are you going to do with Da Ke Sheh?

264. Li-Lin: Da Ke Sheh ….the printing inside is good…inside.

265. Yueh-Hung: What’s inside the book?

266. Li-Lin: The pictures are very beautiful. (Cheng-Yu: The pictures are life- like and scaled?) Yes. (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002).

From the above, when the teacher intertextualized among various printed texts, teachers brought up more teaching resources, including Da Ke Sheh, that might facilitate classroom activities. In the example of 2.2, teachers indeed later used the book A Tree Is Nice (Udry 1987) and The Giving Tree (Silverstein, 1992) Intertextualization extended the possibilities of their uses of teaching materials.

Intertextualizing with Previous Experience

As I noted earlier, intertextualizing occurs when we connect one text with another text, including a current text with a previous text, such as a previous experience.

Intertextualizing with previous experience opens up opportunities in which teachers would identify a greater number and a greater variety of activities that invited, as it were, students into the learning process. For example, our discussions on activities (i.e., the current text) prompted Li-Lin to intertextualize her previous teaching experience with the current text.

She stated that in her past EFL teaching, students had liked activities that associated sounds with familiar written English words, and she suggested that students could associate elephants’ sounds with corresponding English lettering (L 290). She therefore intended to teach a particular assignment by drawing associations between sounds and written words.

2.5

288. Li-Lin: …the elephant appears at least four times.

289. Yueh-Hung: Hmm ….

290. Li-Lin: We had some impression [of the elephant] … I found some key words that we had fun with. For example, this week, in one of my English classes for my grade-four students, they talked about the injured kid’s “Ouch!”

Then, every kid wanted to exclaim “Ouch!” When I asked the kids to act out [the meaning of] “Ouch!” every kid’s expression was very cute. They liked it very much…. Maybe we [the teachers] could add “Ouch!” [to the lesson plan]…. I would like to give them [the students] a similar experience. (T, Hua-Lien, 12- 13-2002)

Indeed, Li-Lin actualized her ideas when she asked students to act out different English phrases (such as “laugh at,” “awake,” “slipped quietly away”) (Li-Lin, LP 12/27/02).

Cheng-Yu carried out the same pattern of cognition. In her case, intertextualization enabled her to connect two disciplines to each other. As I state above, Cheng-Yu mentioned the book I Wish I Could Have a Tree. In this discussion, Cheng-Yu intertextualized current texts (our discussion about the book I Wish I Could Have a Tree) with her previous teaching experience, regarding which she recalled that, on the basis of the book, she had asked students to imagine what they could do on trees. She therefore suggested that we should read books about trees and build a tree house. Through intertextualization, she figured out more opportunities in which we could help students connect different experiences to one another.

2.6

261. Cheng-Yu: … I Wish I Could Have a Tree features a big tree. In the book, the kids build a tree house on the tree, and the tree house then becomes their own secret base. It [the book] is about how humans can get close to trees. I used this book before, and imitated the author of this picture book by asking them [the students] to draw a tree and by then asking them what they’d want to do on the tree. So it became a drawing. (T, Hua-Lien, 1-20-03)

Intertextualize with the Text of the Real World

Intertextualizing with the text of the real world brought another dimension to our inter-language and interdisciplinary activities. The teachers’ efforts to intertextualize the text of the real world with the printed text Elmer (McKee, 1968) reminded the team of real elephants in the zoo. The teachers then generated new ideas to connect various disciplines with one another. In the following, the book Elmer (McKee, 1968) reminded teachers of the death of a famous elephant—Ma-Lan in the zoo in Taipei. Cheng-Yu discussed activities that would connect the children’s book with not only the zoo’s real animals but life education, as well.

2.7

78. Cheng-Yu: Is it possible that we can teach one children’s book. I am now interested in the book, Elmer, a big book. Maybe I can collaborate with Li- Lin. She teaches English, and I teach Chinese, and we can then extend [our respective teaching] to interdisciplinary teaching…or to the death of Ma-Lan. I think we can do a little bit and discuss it [the death] with a current topic in life education. (T, Hua-Lien, 10-16-2002)

Cheng-Yu actualized this intertextualization in her own curriculum. For example, Ma Lan was part of the curriculum in life education (figure 1 and 2). Li-Lin also brought up the relationship between Ma-Lan and life education.

2.8

132.Li-Lin: Is there any discussion on life education? When I discussed this point with Cheng-Yu, it came to my attention that Ma-Lan—the female partner of Taipei Zoo’s elephant Lin-Wang—had died of cancer. At that time, we thought we could organize a life-education class [based on this event].

Yueh-Hung: Hmm.… Yes.

133.Yueh-Hung: Hmm…. Yes.

134.Li-Lin: How can we integrate it [the topic] into life education?

135.Yueh-Hung: Movies concerning life education.

136.Li-Lin: … play videos that concern life education, such as caring for elephants and for elephants’ lives. (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

From the conversation shown in 2.7 and 2.8, the teachers designed inter-language and interdisciplinary activities by intertextualizing among the available printed text (Elmer) with other printed texts (such as Da Ke Sheh—Grand Science), experience (such as teaching experience), and real world (an elephant’s death in a real zoo). We therefore understood, in designing this curriculum, that teachers use various connections and multiple sign systems in designing curriculum. Second, we discovered that curriculum can

come into being when teachers interconnect their own experiences and knowledge. Third, and most important, through intertextualization, the integrated curriculum was formulated and enriched. Intertextualization opens up potential for all kinds of teaching resources and activities.

The above findings strongly suggest that an integrated curriculum therefore integrates not only students’ personal experience and knowledge, as Beane stated (1997), but also—and most important in the current study—teachers’ experience. When integrated, the field of language arts treats “language as a part of life itself. Language is integrated into the daily existence of all people. It is integrated into all aspects of their lives” (Sawyer &

Sawyer, 1993, p. 6). It is therefore reasonable to infer that integrated curriculum is part of teachers’ lives and, indeed, is integrated into all aspects of teachers’ lives.

In addition, as teachers make their own connections rather than rely on pre-fabricated connections made by outsiders, curriculum becomes more meaningful for the teachers. In this regard, Sawyer and Sawyer (1993) note that all modes of available resources “exist in such a way that each supports and derives meaning from the others” (p. 6). In short, as teachers derive meaning from their own available resources, the connections that the teachers draw have a stronger connection to the teachers.

Because intertextualization brings out new dimensions in teachers’ efforts to invite students into the learning process and to connect diverse languages and disciplines to one another, we need to use teachers’ experiences as an enriched resource for curriculum design.

When teachers intertextualized, they developed an integrated curriculum. First, interconnected content was one of the features of an integrated curriculum, as indicated in the theoretical framework above. When teachers intertextualized, they interconnected experiences and content. Second, learning is the united whole that connects our environment and our experience. Teachers connected with the book Elmer (McKee, 1968) and the death of a famous elephant—Ma-Lan in the zoo in Taipei.

At times the activities diverted from the topics. The teachers diverted from the topic of “knowing the self, and liking yourself” when they associated different ideas—the book Elmer (McKee, 1968) and the death of a famous elephant—Ma-Lan in the zoo in Taipei.

The story of Ma-Lan was used for teaching life education and was different from the topic.

At this time, teachers did not enact the experts’ definition of an integrated curriculum, in which activities should refer back to the topics (Beane, 1991, 1997). Nevertheless, these occasional diversions were accepted as it was difficult for teachers to strictly follow the experts’ ideas, and most importantly, the teachers’ voices should be valued, and the teachers created activities that were related to their experiences, which were contextual and meaningful to them.

Projecting

From the above, the teachers’ curricular choices and educative aims were co-created through own experiences. Teachers’ curricular choices and aims, however, could move beyond personal experience as teachers can project future activities. As the team made more and more connections, we examined more and more teaching activities, and much of this process rested on our efforts to project future possible connections and topics from the available resources; that is, an actual body of obtainable resources would be our starting point rather than be just a stepping stone leading from a personal experience or an abstraction to an activity. From available resources, we would begin to identify or to develop teaching activities. In one case, we envisioned the teachable content of a children’s book.

For example, Li-Lin noted that, in the book, a passage describes a place where the animals gather, and on the basis of this passage, she discussed both what she could teach about elephant greetings and how she could craft a corresponding lesson plan (L 36 and L 37). She indeed envisioned the possible content that she wanted to teach from the pictures of existing books.

3.1

36. Li-Lin: … [regarding the lesson plan], I will teach an easy greeting to let students practice easy greetings …

37. Yueh-Hung: This is about manners.

38. Li-Lin: He [Elmer] goes to the forest and bumps into different animals.

They say to each other, “Good morning!” connecting names of animals with

greetings…the animal says, “Good morning, Elmer! Good morning, Lion!

Good morning, tiger!” We connect greetings and animal names. (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

The above envisioned activities had been actualized in Li-Lin’s class as she asked students to say “good morning” and “what’s your name?” (Li-Lin, LP,12-20-2002). On another occasion, one of the teachers (Li-Lin) examined the story of a children’s book and imagined the activities that her students and she could use. I talked about teaching various colors after Li-Lin said that an elephant’s color changes during the course of a story (see Elmer, McKee, 1968, above), and our discussion then veered toward the content of the book’s discussion of colors (L 238) (3.2). Cheng-Yu also brought up the page describing Elmer’s different patches, and Li-Lin subsequently explored Elmer’s many colors: yellow, orange, pink, and blue (L 240) (3.2).

3.2

238. Yueh-Hung: Hmm…I think, after they [the students] finish their art, you could ask them to add an English description, for example, to write what kind of elephant they want to be, what kind of name they might give to an elephant.

Li-Lin can therefore teach “What is this?” And when they introduce it [their own elephant] to another [another student], they can say, “This is so-and-so …,”

“This is a so-and-so …,” or “His name is so-and-so …” I just heard that Li-Lin has talked about how the elephant, by rolling around the ground, takes on the color of a normal elephant … this is knowledge of colors.

239. Cheng-Yu: On the page describing Elmer’s different patches …

240. Li-Lin: We can introduce how Elmer was different. And then introduce how many colors Elmer has, yellow, orange, red, pink, purple, blue, green, black, white, nine different colors.

241. Yueh-Hung: [The topic of] color can be brought up [in class] through art.

242. Li-Lin: … his color is different from [that of] the others [the other elephants], a fact that has bothered her, and she wishes to be the same as the

other elephants … in art, you want students to make a “be yourself” elephant.

You can teach them [to express] what color they want the elephant to be … (T, Hua-Lien, 11-22-2002)

By examining children’s literature, the team further envisioned the possible content of course plans that would help students connect languages to one another. In the following discussion, the topic of an elephant’s appearance arose as it was written in one sentence in the book. Cheng-Yu mentioned that, in this regard, we should teach the English- language words ‘tall’, ‘short’, ‘fat’, and ‘slim’ (L 754); and Li-Lin said that there are only descriptions of appearances in the book (L 755).

3.3

753. Li-Lin: There is no description in the front.

754. Cheng-Yu: So, only ‘tall’, ‘short’, ‘fat’, and ‘slim’…

755. Li-Lin: Only the appearance.

756. Cheng-Yu: Appearance. (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

The above discussions (3.2, 3.3) were actualized in Li-Lin’s class (Li-Lin, LP,12-27- 2002), in which Li-lin asked students to tell the colors of Elmer by pointing out the color in the picture book Elmer (McKee, 1968). In addition, ‘tall’ and ‘short’ were taught in the same class by using the sentence pattern, “I am___” and pictures of tall and short objects (Li-Lin, LP, 12-27-2002). In addition, the team discussed more activities. We envisioned more possible content and activities under the theme of personality through an examination of the book’s content. In the following conversation, I suggested that we could introduce elephants’ major characteristics of personality (L 116). Li-Lin said that, by taking such phrases from the book as “the other elephants were standing absolutely still, silent and serious” (McKee, 1968, p. 22), we could discuss elephants’ specific characteristics of seriousness, silence, and stillness (L 117).

3.4

116. Yueh-Hung: … there’s that song “One Elephant Went Out to Play”….

When we introduce elephants’ characteristics, we can integrate English [into the exercise] ….

117. Li-Lin: The descriptive part is easier. We can talk about morning greetings or [elephants’ characteristics of] seriousness, silence, and stillness. We only talk about this. The elephant is serious, quiet, almost motionless….(T, Hua- Lien, 11-22-2002)

We continued to talk about personalities by referring specifically to the content that we could teach, such as “seriousness,” “silence,” and “stillness” (L 746).

3.5

741. Cheng-Yu: … we will give him a personality.

742. Li-Lin: Oh! A cool personality.

743. Cheng-Yu: ….we should talk about personality when we talk about the self.

. .

746.Yin-Chung: When she [Li-Lin] talked about elephants’ personality, she talked only about “seriousness,” “silence,” and “stillness,” and described elephants as “serious,” “silent,” “still,” and “standing.”

747. Cheng-Yu: But, actually …

748. Li-Lin: We can focus on the stillness of the elephant. He is lonely. That’s about personality …

749. Yueh-Hung: But we won’t read through that page [in the book].

750. Cheng-Yu: No? No?

751. Li-Lin: Probably not.

752. Yueh-Hung: Not yet. That personality….(T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

In addition, Li-Lin also discussed elephants’ moods, namely happiness and sadness, which are mentioned in the book.

3.6

744. Li-Lin: ….you selected only “happy” and “unhappy,” right?

745. Yueh-Hung: …yes….Only “happy” and “unhappy,” right? (T, Hua-Lien, 12-13-2002)

In the class (Li-Lin, LP. 12-20-02), Li-Lin introduced English words concerning the personality and the mood of an elephant by teaching the words and by asking students to act out happiness, a smile, seriousness, and silence.

The team made connections among disciplines as we examined another topic, I and the nature. We brought up children’s book, The Giving Tree (Silverstein, 1992), through which we could explore various issues, such as environmental protection and interaction between parents and kids (L 260). Cheng-Yu mentioned herein that we could let students draw and, indeed, build a tree house on a tree (L 261). Cheng-Yu further mentioned that the activity could become a drama (L 263), and I mentioned that the activity could connect to social interaction and mathematics (L 264).

3.7

260. Yueh-Hung: … Yes. See how we could extend it [the activity to various disciplines]. I think that The Giving Tree, like what you said, for example, talks about environmental protection. It talks about environmental-protection issues, interaction between parents and kids, collaboration, appreciation of the self, and human interaction.

261. Cheng-Yu: … I Wish I Could Have a Tree features a big tree. In the book, the kids build a tree house on the tree, and the tree house then becomes their own secret base. It [the book] is about how humans can get close to trees. I used this book before, and imitated the author of this picture book by asking them [the students] to draw a tree and by then asking them what they’d want to do on the tree. So it became a drawing.

262.Yueh-Hung: A drawing …

263. Cheng-Yu: One teacher said that The Giving Tree can become a drama.

264. Yueh-Hung: I think the meaning of The Giving Trees is deep. We could just get one to two meanings [from the book]. We can feel its connection to social interaction, to mathematics, as when a lot of apples drop …(T, Hua- Lien, 1-20-03)

The teachers continued to extend the activities through projecting. Indeed, the teachers searched for meaning by patterning the activities in relation to similarly themed content. As indicated above, the brain functions to connect patterns automatically, and Caine and Caine stated that “the search for meaning occurs through patterning” (p. 81).

Discussions

The findings rigorously infer that the creation and the enrichment of integrated curriculum stem largely from teachers’ search for the focus, connections, and projections.

First, the process by which the teachers integrated the curriculum was a united whole. The process of teachers drawing connections between integrated curriculum (environment) and their own experiences was holistic insofar as such process is the united whole encompassing environment and experience (knowledge and personal experience), a point indicated in the theoretical framework. Teachers drew these connections by applying and further abstracting available resources to find topics, which served learning-activity topics, and by intertextualizing among an available printed text (McKee, 1968), experience (a real elephant in a real zoo), and knowledge (the principles expressed in Da Ke Sheh—

a science book). Teachers themselves also used their own knowledge to project possible activities. In general, all these processes reside in the transaction between environment (integrated curriculum and available resources) and teachers’ personal experiences.

Second, teachers generated integrated curriculum that was meaningful and purposeful for them. The contextualization of the entire integrated curriculum rested on teachers’ own purpose, teaching, and experiences. Teachers were learning as they made progress in searching the focus, designing their own curriculum, and projecting future activities. Therefore, the whole process fit the theory that learning is a united whole, as it

cannot be separated from context and purpose (Murdoch & Hornby, 1997) and meaning (Beane, 1991; Barton & Smith, 2000), as indicated above in the theoretical section.

In addition, discussion is meaningful for teachers who strive to be faithful to meaning boundaries; for example, the teachers were trying to identify and explore topic-related activities rather than forcibly insert topic-unrelated activities from different disciplines into the topic.

According to the findings here, teachers serve as enriched resources while striving for an integrated curriculum, and teachers educators trust teachers as integral components of curriculum development and should invite teachers to engage in integration-themed conversation so that they will be in a better position to generate and to enrich integrated curriculum. A prescriptive approach to integrated curriculum will limit two critical factors:

the beneficial role in which teachers use their enriched experiences to facilitate the creation of effective integrated curriculum; and the beneficial role in which teachers use these experiences to create a meaningful context for integrated curriculum. In both of these roles, teachers are making important connections; and the connection-making that teachers pursue is reflective of various models. However, as this study shows, each model rests significantly on teacher input.

The findings provide insights not only for teachers who are integrating curriculum but also for teachers who are seeking to acquire professional development in general.

Jackson and Davis (2000) stated that effective professional development of teachers is result driven, as it rests on achieving various standards that teachers and students should know and should be able to meet. Moreover, the standards help maintain the high quality of

“the professional development activities themselves” (Jackson & Davis, 2000, p. 111). The current study suggests that teachers’ professional development would be more effective if educators more rigorously examined the processes underlying this development, and if educators developed programs that best support teachers.

Often, the common goal of teacher professional development is to enhance teachers’

knowledge and skills and, thereby, to improve students’ learning (Jackson & Davis, 2000, p. 115). The current study suggests that teachers can successfully develop their own knowledge and skills, and that outside experts’ responsibility is to cultivate teachers’

experience knowledge rather than to lecture knowledge and skill to teachers.

Conclusion/Implications

As teachers’ integration of curriculum can be a holistic learning process, this study suggests that the most effective path toward teachers’ professional development for integrated curriculum is to set up discussion groups where teachers can freely use their own personal experiences and knowledge to engage in all kinds of connections.

Teachers draw all kinds of connections, and engage in rigorous teaching, when the curriculum is meaningful to them; consequently, teachers’ related professional development can benefit greatly from teachers’ full autonomy in designing their own personally meaningful curriculum. They can take charge of selecting their own topics, selecting their own materials, and designing their own activities.

Finally, available resources play a key role in integrating curriculum. Certain types of resources, especially authentic picture books and storybooks, lend themselves to teachers’

generation of all kinds of activities, and teachers should therefore not hesitate to use these resources. Often the limited content of a textbook limits teachers’ thinking and creativity.

References

Appel, M. P. (2006). Arts integration across the curriculum. Leadership, 36(2), 14-17.Barton, K.C.

& Smith, L.A. (2000). Themes or motifs? Aiming for coherence through interdisciplinary outlines. The Reading Teacher, 54(1), 54 - 63.

Beane, J. (1991) Middle School: The Natural Home of Integrated Curriculum. Educational Leadership, 49(2), 9-13.

Beane, J. A. (1997). Curriculum integration: Designing the core of democratic education. New York, NY: Teachers College.

Blake, J. (1992). You're a Hero, Daley B.! Somerville, MA: Candlewick

Caine, R. N, & Caine, G. (1991). Making connections: Teaching and the human brain. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Carle, E. (1988). The Mixed-Up Chameleon. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 125-130.

Curtain, H. A. (1986). Integrating content and language instruction. In F. K. Willetts,(Ed.), Integrating language and content instruction. Proceedings of the Seminar (p.9-11). L.A:

Center for Language Education and Research. California University.

Curtain, H. & Haas, M. (1995). Integrating foreign language and content instruction in grades K-8.

ED381018.

Drake, S. (1998). Creating integrated curriculum: Proven ways to increase student learning.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin

Eco, U. (1984). The role of the reader. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Etim, J. S. (2005). Curriculum integration K-12: Theory and practice. Lanham, MA: University Press of America.

Flowers, N., Mertens, S. B., & Mulhall, P. F. (1999). The impact of teaming: Five research-based outcomes of teaming. Middle School Journal, 36(5), 9-19.

Fogarty, R. (1991). The mindful school: How to integrate the curricula. Arlington Heights, IL: IRI/

SkyLight Training and Publishing.

Fogarty, R. (2002). The mindful school: How to integrate the curricula. 2nd ed. Arlington Heights, IL: IRI/SkyLight Training and Publishing.

Jackson, A. W. & Davis, G. A. (2000). Turning Points 2000: Educating adolescents in the 21st century. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Jacobs, H. H. (1989). The interdisciplinary concept model: A step-by-step approach for developing integrated units of study. In H. H. Jacobs (Ed.), Interdisciplinary curriculum: Design and implementation (pp. 53-65). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curiculum Development.

Jacobs, H. H. (1991). Planning for curriculum intetration. Educational Leadership. 49(2), 27-28.

Jang, Syh-Jong. (2006). Research on the effects of team teaching upon two secondary school team teachers. Educational Research, 48(2), 177-194.

Loepp F. L. (1999). Models of curriculum integration. Journal of Technology Studies, 25(2), 21- 25.

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Lynch, P. (2007). Making meaning many ways: An exploratory look at integrating the arts with classroom curriculum. Art Education, 60(4), 33-38.

Mckee, D. (1968). Elmer. New York, NY: Harper-Collins.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Met, M. (1991). Learning language through content: Learning content through language. Foreign Language Annals, 24(4), 281-295.

Murdoch, K. and Hornsby, D. (1997). Planning curriculum connections whole-school planning for integrated curriculum. Melbourne, Australia: Eleanor Curtain Publishing.

Peirce, C. S. (1931-1960). In C. Hartshorne & P. Weiss (Eds.), Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vol. 2). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sawyer, W. E., & Sawyer, J. C. (1993). Integrated language arts for emerging literacy. New York, NY: Delmar Publishers.

Short, K. G. (1986). Literacy as a Collaborative Experience. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Silverstein, S. (1992). The Giving Tree. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Smith, F. (1986). Understanding reading: A psycholinguistic analysis of reading and learning to read. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Smith, F. (2004). Understanding reading: A psycholinguistic analysis of reading and learning to read. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tchudi, S., & Lafer, S. (1996). The interdisciplinary teacher's handbook. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Titscher, S., Meyer, M., Wodak, R., & Vetter, E. (2002). Methods of text and discourse analysis (B.

Jenner, Trans.). London, England: Sage Publications.

Tseng, Y-H.(1999a).探索兒童英語文學習的內心世界-以全語文兒童英語文教學為

例。(pp. 165-180)。跨世紀國小英語教學研討會論文集。教育部主辦,國立屏

東師範學語文教育學系承辦。[Exploring the EFL learning of children: Examples from a holistic language class.Proceedings of the Cross-century Conference on EFL Learning for Elementary Schools. Ping-Tung: Ping-Tung Teachers' College in Taiwan].

Tseng, Y-H. (1999b).全語文兒童英文教學:以記號學的觀點探索語文教學。行政院

國家科學委員會專題研究計畫成果報告[EFL holistic language: Exploring language teaching from a semiotic perspective. Final Report submitted to the National Council of Science in Taiwan].

Tseng, Y-H. (2000).兒童英語文教學-全語文觀點。臺北市:五南出版社。 [EFL

teaching for children from a holistic-language point of view]. Taipei, Taiwan: Wu-Nan Publishing Co.

Tseng, Y-H. (2001a).全語文兒童英語文教學:課程、認知學習和評量。國科會研究成

果報告。高雄師範大學主辦。六月一至二日,2001年。[EFL holistic language:

Curriculum, cognition, and evaluation. Conference on reported projects sponsored by the National Science Council. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: National Kaohsiung Normal University, June-1-2, 2001].

Tseng, Y-H. (2001b).兒童英語文教學-全語文觀點。臺北市:五南出版社。[EFL

teaching for children from a holistic-language point of view. 2nd edition]. Taipei, Taiwan: Wu- Nan Publishing Co.

Tseng, Y-H. (2003). Help for the Biliteracy Teacher: Classrooms that Work. Taipei, Taiwan: Crane Publishing Co.

Tseng, Y.-H. (2010). “From whole to part": Pre-Schoolers learning EFL. Hwa-Kang English Journal, 16, (July, 2010), 31-60.

Tseng, Y.-H. (2011). Fostering Pre-service Teachers´Critical Perspectives through an Inquiry- based Curriculum. Hwa-Kang English Journal, 17, (April, 2011), 67-94.

Udry, J. M. (1987) A tree is nice. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Young, E. (1992). Seven blind mice. New York, NY: Scholastic.