CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

In this chapter, the results presented in Chapter Four will be interpreted and discussed.

I will first provide an overview of the study with the problem statement and a brief description of the experiment. Following each research question, results will first be summarized and then possible interpretation discussed. Implications for teaching and research will then be drawn and a conclusion will be provided.

Overview of the Study

This study is concerned with alternative approaches of teaching facilitation that appeal to learners’ motivation in an EAP reading situation. Effects of motivational materials and learner preferences of these materials are the major focus of the investigation. Analyses have also been made to explore the relationship between learner preferences and their characteristics.

As introduced earlier, this study employed a within-subject 3 (Vocabulary List treatment, Self Appraisal treatment, and Case Study treatment) by 3 (three articles each on Job Satisfaction, Early Motivation Theories, and Leadership) factorial design. Participants were recruited from two colleges to read EAP texts with three different pre-reading treatments.

Vocabulary Lists were 20-item English-Chinese equivalents that prepared learners to understand the texts. This treatment represented a typical approach EFL teachers use to facilitate EAP reading. Self Appraisals required learners to answer questions to appraise their own personality inclinations. Following Keller’s principle of perceptual arousal, it was hoped that this treatment would “create curiosity, wonderment by using novel approaches, injecting personal and/or emotional material” (Keller, 1987b, p. 3). It was hypothesized that learners would experience some personal exploration in doing such exercises and have an interest in reading further. Case Studies described related real-world business problems.

Following Keller’s principle of inquiry arousal, Case Study was expected to “increase

curiosity by asking questions, creating paradoxes, generating inquiry, and nurturing thinking challenges” (Keller, 1987b, p. 3). The purpose of this treatment was to appeal to learners’

intellectual curiosity and capture their attention. Both Self Appraisal and Case Study were adapted from materials in the selected text and translated into learners’ L1.

Participants from two sites were compared on pretest and posttest scores and it was then decided that all following analyses be done by separating participants from the two sites.

ANCOVA analyses were conducted for participants’ scores on: (1) immediate situational motivation after treatments, (2) situational motivation mediated by reading experiences, and (3) EAP reading comprehension to examine the effects of two attention-arousal treatments versus one cognition-oriented treatment. In addition, participants reported their most preferred and least preferred treatments after they completed the experiment and provided written reasons. In order to see if there existed specific preference patterns, two-way contingency table analyses were conducted to test the homogeneity of proportions among preference/dislike groups. Written responses were collected and analyzed to further examine why participants liked or disliked certain treatments. Finally, participants were grouped according to their preferences and dislikes. Comparisons among preference/dislike groups on pretest motivation scales and proficiency tests were made using MANOVA analyses to investigate if participants with different preferences/dislikes differ significantly in these pretest variables.

Discussion

In this section, each research question will be restated first, results will be summarized immediately following the question, and interpretations on the observed results will be discussed in detail.

Comparison Between Two School Sites

Question 1: Did participants from the vocational-oriented and academic-oriented educational systems differ in (a) pretest motivation scales, (b) pretest proficiency tests, (c) situational motivation, and (d) EAP reading comprehension?

The results of t tests show that Site A participants scored significantly higher on two pretest motivational scales (General Academic Motivation and EFL Learning Motivation) than Site B participants while Site B participants had significantly higher scores on both pretest proficiency tests (EFL Reading Comprehension and Academic Reading Comprehension in L1) and three EAP reading comprehension scores than Site A participants.

Results of t tests on L1 Academic Reading Motivation and six measured situational motivation scores did not show significant difference between the two groups. The comparison on pretests indicated that participants from Site A had higher motivation and lower proficiency than those from Site B. The comparison on posttests also showed a superiority of Site B on comprehension; however, Site A participants did not demonstrate higher situational motivation.

The results of pretest comparison seem to contradict with both Corder’s (1973) famous phrase, “Given motivation, anyone can learn a language,” and the common research findings that motivation results in language achievement (e.g. Gardner, Tremblay, & Masgoret, 1997).

Site A participants, despite their higher EFL Learning and General Academic motivation, were significantly less proficient in EFL Reading and L1 Academic Reading Comprehension.

Tracing back to Site A participants’ past school history, as discussed in Chapter Three, they followed the vocational education track since high school, which was in general an indication of relatively lower academic performance compared to participants from Site B. However, participants from Site A, although they may not represent the majority of vocational students, persisted long enough to have first completed a lower-level two-year program (similar to freshmen and sophomores in a four-year university) and eventually entered this final two-year

program for a bachelor’s degree. Their past academic history may partly explain the observed combination of higher motivation with lower competence. Cautions still have to be exercised when generalizing findings here to other vocational college students since participants were selected through convenience sampling. On the other hand, Site B participants had higher proficiency and lower motivation. It may be that Site B participants, being freshmen who had just relieved from the competition for entering into college and were still far away from concerns about graduating and career planning, were not as serious as Site A participants in their school learning, despite the fact that they demonstrated higher competence. The findings about the different characteristics of participants from the two sites, although not necessarily generalizable to other student populations, may make practitioners and researchers more aware of the possible combination of high/low motivation with low/high proficiency in the same student population and consider necessary adjustments in pedagogy and theory.

Another phenomenon worthy of our attention is that Site A participants had higher motivation in pretests but not in situational motivation than Site B participants. However, Site B participants scored higher in both proficiency pretests (EFL Reading Comprehension and Academic Reading Comprehension in L1) and EAP reading comprehension posttests (three comprehension tests after reading the three EAP articles) than Site A participants.

Although Site A participants scored higher in trait motivation (General Academic Motivation and EFL Learning Motivation), they were not significantly different from Site B participants in any of the six situational motivation scores. The observed phenomenon may provide a piece of evidence for Gardner and Tremblay’s (1994b) claim that situational characteristics may interact with traits to increase or decrease situational motivation. The actual reading experience with the three different texts and other contextual influences may have significantly decreased Site A participants’ original higher trait motivation and brought their situational motivation scores to a lower level that was not different from that of Site B

participants. Another way to explain the result is that proficiency may be a relatively more stable learner attribute, while motivation is more vulnerable to changes from the environment and it fluctuates accordingly.

To sum up, Site A participants, who have followed the technological and vocational education track under the established educational system in Taiwan, should be distinguished from Site B participants, who had been educated for continuing academic purposes in their past experiences. These t test results made it necessary to answer all following research questions by site. Results for Site A and Site B may each be interpreted with reference to the distinctive characteristics of these two different student groups and should only be inferred with caution to the relative student populations.

Effects on Situational Motivation

Question 2: To participants from both or either one of the school sites, which of the three treatments (Vocabulary List, Self Appraisal, or Case Study) best motivated them to read before and after the reading tasks?

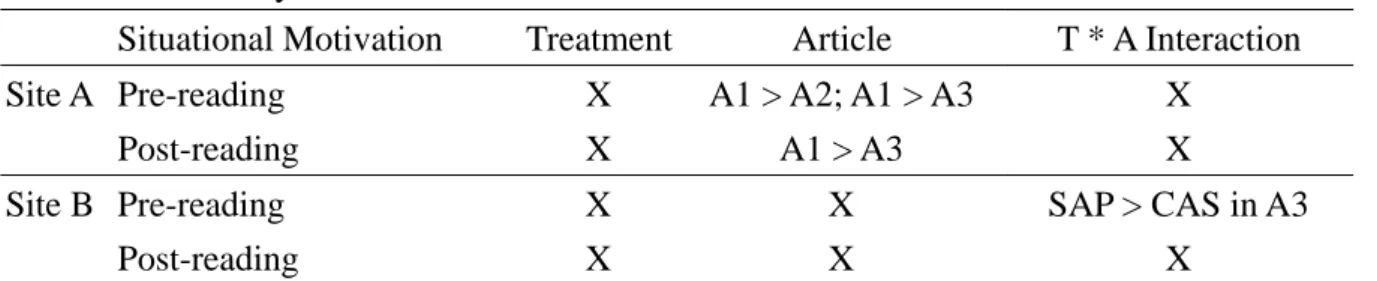

As summarized in Table 33, the results for Question 2 indicate that none of the three treatments better motivated participants to read in either pre-reading or post-reading stage for either group of students. However, article and treatment had significant interaction on pre-reading situational motivation for Site B participants. More specifically, in reading the third article Leadership, those who received the Self Appraisal treatment in Site B had higher pre-reading situational motivation than those who received the Case Study treatment.

Finally, although it was not a concern in the research question, article effect was found to be significant on both pre-reading and post-reading situational motivation for Site A participants.

Participants from Site A had higher pre-reading situational motivation for the first article than for the second and the third; they also had higher post-reading situational motivation for the first article than for the third.

Table 33. Summary of Treatment/Article/Interactive Effect on Situational Motivation Situational Motivation Treatment Article T * A Interaction

Site A Pre-reading X A1 > A2; A1 > A3 X

Post-reading X A1 > A3 X

Site B Pre-reading X X SAP > CAS in A3

Post-reading X X X

Note: A1 = Job Satisfaction; A2 = Early Motivation Theories; A3 = Leadership

SAP = Self Appraisal treatment; CAS = Case Study treatment; X = no significant result

Pre-reading Situational Motivation

Pre-reading situational motivation, as it was measured before participants had a chance to interact with the EAP texts, should be free from the influence of language or content of the articles and the actual reading experience. Therefore, situational motivation measured at the pre-reading stage, compared to post-reading situational motivation, should be a more direct and precise indicator of the effect of treatments.

Site A For Site A participants, the three treatments were not different in bringing about their pre-reading situational motivation. The Vocabulary List treatment, designed to cater to learners’ foreign language needs, did not appear to be inferior to the other two treatments in its motivational effect. Facilitation in language seems to, at least indirectly, contribute to a motivation to read in this EAP setting. A possible explanation is that the Vocabulary List treatment provided participants with concrete information for and easy access to the texts, which in turn gave participants more confidence (another major component in Keller’s ARCS model) that led to a certain degree of situational motivation. The lack of treatment effect may be indicative of the insufficiency of the Self Appraisal and Case Study treatments in enhancing learner motivation for their EAP reading tasks, making us to be more cautious about theories borrowed from outside the L2 field (Gardner & Tremblay, 1994b).

With the presence and potential of an insufficient L2 that may negatively influence learner motivation, L2 motivational theories accounting for situational characteristics should probably consider including a language element.

The observed article effect, i.e. higher pre-reading situational motivation in the first article than in the second and the third, may not be a function of the articles themselves since, as stated earlier, participants had not yet read the articles at this stage. Instead, it may be more likely due to the sequence of the articles. When participants received the treatments for the first time, there may have existed a novelty effect. However, experience in reading the first article may perhaps have influenced their expectation on the following reading experiences and caused their situational motivation to decrease significantly from the first time, making pre-reading situational motivation measured the second and the third time significantly lower than that measured the first time.

Site B The same interpretation for the lack of treatment effect in Site A also holds for Site B. Article effect did not exist in Site B as it did in Site A. This may indicate that the novelty effect for the first pre-reading situational motivation or the negative impact from previous reading experiences on the second and third pre-reading situational motivation, as observed in Site A, did not exist in Site B. Significant interaction between treatment and article was found here for Site B. The Self Appraisal treatment induced significantly higher pre-reading situational motivation than the Case Study treatment in the third article Leadership. Again, since participants had not read the articles at this stage, the interaction should not be a function of the article.

To further examine why the Self Appraisal treatment for the third article had stronger positive effects than the Case Study treatment, I have examined the written reasons of preference participants provided in more detail. Appendix G, a collection of participant responses recorded verbatim, listed the reasons under each individual treatment and provided clues to why participants liked or disliked specific treatments.

As Table G3 shows, participants preferred this Self Appraisal treatment because it was fun, interesting, simple, and it aided self-understanding. Participants disliked it because they perceived no links between the treatment and the subsequent article they read and they felt

their understanding of the text was not aided by this treatment. By comparing this information with those of the other two Self Appraisal treatments, I found the reasons provided were almost identical. In Self Appraisal treatment for the first and the second article, almost equal numbers of responses were given for liking and disliking this treatment.

The reasons were indistinguishable between the more influential Self Appraisal treatment –

“Personal Leadership Style Test” for the third article and the other two Self Appraisal treatments. The only difference was in the number of responses collected. In other words, the relatively stronger effect of the particular treatment may not be one of a different nature, but one of a greater magnitude.

Going further into the literature in the field of Organizational Behavior, one realizes that this Personal Leadership Style Test is a standardized research tool that has received wide attention. Unlike other common self-appraisal questionnaires in which respondents can expect what the test is about as they answer the individual items, the significance of this 16-item questionnaire lies in the unexpected results when a respondent first answers it. The questionnaire asks respondents to think of a co-worker that he or she dislikes the most, and rate that co-worker against 16 sets of extreme adjectives (e.g. pleasant vs. unpleasant, accepting vs. rejecting, and hesitant vs. self-assured, etc). To most respondents’ surprise, the resulting score has nothing to do with the person rated in the questionnaire; instead, it tells whether the respondent is a relation-oriented or a task-oriented leader. This unique nature of the specific treatment has very likely surprised and motivated some participants and hence triggered the effect on pre-reading motivation.

Post-reading Situational Motivation

Post-reading situational motivation is considered as pre-reading situational motivation mediated by the actual reading experience. When pre-reading situational motivation was not different among treatments, we did not expect to see treatment effects on post-reading situational motivation. When there was difference in pre-reading situational motivation, the

change in subsequent post-reading situational motivation might be considered as the function of the relative reading experience. Therefore, discussion in this section will center on the observed change from pre-reading to post-reading situational motivation.

Site A Like the results on pre-reading situational motivation, there was no treatment or interactive effect on post-reading situational motivation. The only change was that post-reading situational motivation for the first time became higher than for the third time, while in the pre-reading stage, motivation was higher for the first time than for both the second and the third time. A possible explanation may be that participants’ better comprehension on the second article (results for Question 3) positively influenced their perception, compensated for the lack of novelty in the pre-reading stage, and brought the post-reading situational motivation to a higher level. This positive influence from the relative reading experience did not exist when participants read the third article that was more difficult, hence resulting in a significantly lower post-reading situational motivation for the third article than for the first.

The above interpretation can be further explained by Crookes and Schmidt’s (1991) emphasis on the importance of a match between learners’ subjective estimates of his/her skill level and the challenge level of the tasks. Functioning in a foreign language setting, EFL learners are more subject to the possible threat of high challenges in the language. Similarly, higher comprehension may contribute to a higher level of situational motivation.

Site B For the third article, the Self Appraisal treatment induced higher pre-reading situational motivation than the Case Study treatment for Site B participants. However, this treatment effect did not last to the post-reading stage. It seems that the reading experience produced a stronger negative effect that offset the higher situational motivation brought from the pre-reading stage for the group of students who received the Self Appraisal treatment, hence making the post-reading situational motivation of the Self Appraisal treatment group

not different from that of the Case Study group. Site B participants’ lower comprehension scores on the third article than on the other two may further support this argument. Crookes and Schmidt’s (1991) claim for an important match between the challenge level of tasks and learners’ own skill level may also apply here to explain the observed results.

Effects on Comprehension

Question 3: To participants from both or either one of the school sites, which of the three treatments (Vocabulary List, Self Appraisal, or Case Study) was best at facilitating comprehension?

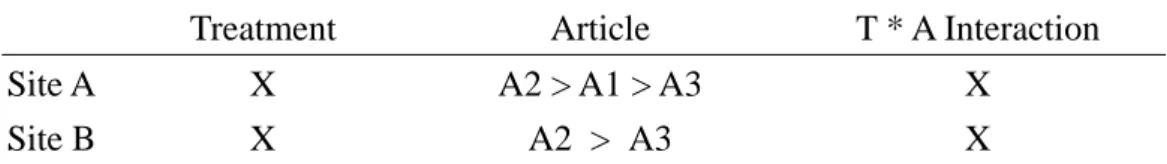

This study found no treatment effect or treatment by article interaction on comprehension in either site. However, it was found that article had strong effects on comprehension for both Site A and Site B participants. In Site A, comprehension scores on three articles were significantly different, with the highest on the second article and the lowest on the third. In Site B, comprehension on the second article was better than on the third, while comprehension level on the first article was not different from that on the other two articles. The results are summarized in Table 34. Since the only difference between results for both sites was the significance of the first article, the results from the two sites will be combined in the discussion here.

Table 34. Summary of Treatment/Article/Interactive Effects on Comprehension

Treatment Article T * A Interaction

Site A X A2 > A1 > A3 X

Site B X A2 > A3 X

Note: A1 = Job Satisfaction; A2 = Early Motivation Theories; A3 = Leadership X = no significant result

Vocabulary List, the traditional approach focusing on language, was expected to have an effect on comprehension rather than on motivation. A possible explanation for the lack of treatment effect or interaction on both sites may be that for such complicated expository texts, lists of 20 key vocabulary items were not enough in facilitating participants’ comprehension of the articles. “Threshold hypothesis” (Clarke, 1980) may be another possible explanation

for the absence of treatment effect on comprehension, especially for most participants from Site A and possibly some from Site B. A closer examination on the readability indices of texts and participants’ low correction rate on pretest comprehension tests can support the hypothesis that most participants did not reach a linguistic threshold to comprehend the three texts.

Article effect, though not the purpose of the study, was found to be significant. The reasons for the observed article effect may be threefold. First, although three articles had been compared with readability indices to make sure they were linguistically equivalent, it was acknowledged at the beginning that difficulty level of concepts may vary. It seemed that the third article contained much more complicated theoretical concepts than the other two.

Second, it is possible that participants may have already taken other courses in their specialized area and learned similar concepts regarding motivational theories in other introductory courses such as Business Psychology, thus making comprehension on the second article the highest with the assistance of background knowledge. Third, a further comparison between the articles shows that iconic signaling (Hauptman, 2000), as discussed in Chapter Two, available in the second article Early Motivation Theories (two figures explaining abstract theories) and in the first article Job Satisfaction (one figure illustrating a concept) probably aided comprehension considerably, while in the third article Leadership iconic signaling by graphs was absent.

Participant Preferences and the Reasons

Question 4: To participants from both or either of the school sites, which of the three treatments (Vocabulary List, Self Appraisal, or Case Study) did they most and least prefer?

Why?

In Site A, the numbers of participants choosing the three treatments as their most and least preferred ones were not different in proportion. In Site B, the homogeneity of proportion also held for groups of participants with different most preferred treatments;

however, a significantly smaller number of participants chose Case Study as their least preferred treatment than those choosing the other two treatments. Reasons provided by participants were already summarized in Chapter Four.

The results for Site A indicate that participants’ preferences were equally distributed among the three treatments for different reasons. All three types of materials have their own unique functions in motivating participants to read.

The results from Site B show a different story. Significantly fewer participants in Site B chose Case Study as their least preferred treatment. As discussed in Chapter Two, L1 reading motivation researcher (McCombs, 1997) has pointed out that what may motivate a particular student to read may not motivate another student to read. The results here provide a piece of empirical evidence to support the claim. Motivation, unlike comprehension, is less straightforward and may be multidirectional. The analyses done in Chapter Four for reasons provided by participants seem to indicate that each learner may be motivated by different elicitations for his or her own unique reasons. Self Appraisal and Case Study, two motivational treatments of different nature, were at the same time liked and disliked by participants. Vocabulary List, though not designed for motivation, was in general indistinguishable from the other two treatments in motivational effect as shown by participants’ reported preferences/dislikes and reasons. This shows that language support may also motivate students if it is perceived as facilitative for comprehension. While an L2 language need is not included in Keller’s (1983a) ARCS model or most other motivational theories, this L2 component can be interpreted as contributing to learners’ competence, which functions as one of the more common motivational factors – confidence. The results for Question 4 seem to point to a need for further analyses into individual differences among groups of learners showing different preferences and this will be answered in Question 5.

Differences Among Preference Groups

Question 5: To participants from both or either of the school sites, did those with different preferences differ from one another in their motivational orientations and/or proficiency levels as measured in the pretests?

In Site A, groups of participants preferring and disliking different treatments did not differ from one another in the pretest motivational scales and proficiency test scores. In Site B, groups of participants with different most preferred treatments did not differ from one another on any of the pretest variables, either. However, those participants who chose Self Appraisal treatment as their least preferred one had significantly lower General Academic Motivation and EFL Reading Comprehension scores than those who chose Case Study.

The phenomenon observed in Site A seems to suggest that, for this group of participants who had higher motivation and lower proficiency, the pretest variables failed to distinguish the three groups of different preferences. It may be that preference was a subjective perception independent of trait motivation and proficiency. A possible alternative explanation is that the difficulty of the texts and the challenges embedded in decoding the texts were high enough to bring highly-motivated students’ (within this group) motivation down to a level indistinguishable from less-motivated students and negatively influence their perception over the treatments and the entire learning task, hence no difference was found among preference groups. Another possible reason is that the five pretest variables were not sufficient in distinguishing the groups of participants with different preferences. There might be other factors that this research did not explore.

As for Site B, the results seem to suggest that more intellectually challenging materials may appeal to students with higher academic motivation and higher EFL proficiency. But the same materials may not have similar effect on students whose academic motivation and EFL proficiency is lower. On the contrary, to those students with lower academic motivation, it seems materials should remain simple and interesting in order to attract their attention.

Reasons participants provided for their preference and dislike seemed to confirm the above reasoning. Positive feelings towards Self Appraisal were fun oriented while positive feelings towards Case Study were based on understanding of the texts. On the other hand, negative feelings towards Self Appraisal were related to its lack of assistance for understanding and negative feelings towards Case Study were mainly complaints about the complicatedness and boredom. That is, Case Study was associated by participants with understanding of texts, while Self Appraisal was associated with fun and not the text.

Teachers’ decision on what types of materials to use should be based in part on a better understanding of students, in particular through an assessment of learners’ academic motivation and EFL proficiency levels. The mismatch in this respect may cause learners to feel negative about the learning materials they receive. This is a point that has never been brought up in the past literature of L2 motivation. To further elaborate this view, I refer to literature outside of the L2 field and explain the above argument in terms of two types of curiosity and, more specifically, the seductive interest in reading.

Epistemic vs. Perceptual Curiosity

In designing the study, Case Study was chosen according to Keller’s (1987b) principle of inquiry arousal and Self Appraisal was chosen according to Keller’s principle of perceptual arousal. Participants’ perception between the two types of motivation-oriented treatment is somewhat analogous to Berlyne’s (1965) distinction, later used both by Keller (1983a) and Arnone and Small (1995), between epistemic and perceptual curiosity discussed in Chapter Two of this study. As indicated by Arnone and Small (1995), epistemic curiosity leads to an information-seeking and problem-solving behavior that occurs as a result of the stimulation of curiosity. On the other hand, perceptual curiosity is a more sensory-level reaction; it is selective attention in response to particular objects in the environment. Other similar pairs of terms representing similar concepts include Malone’s (1981) cognitive and sensory curiosity, Arnone and Small’s (1995) specific and diversive curiosity, as well as Kintsch’s

(1980) cognitive and emotional interest. The Case Study treatments, disliked by students with lower academic motivation and EFL proficiency and preferred by students with higher academic motivation and EFL proficiency, seem to induce a kind of situational motivation similar to the higher-level epistemic curiosity. The Self Appraisal treatments, however, seem to induce situational motivation similar to the lower-level perceptual curiosity and have characteristics that are more controversial and require more caution in research and classroom practices as they resemble the kind of seductive interest discussed in reading literature.

Seductive Interest and Reading

As discussed in Chapter Two, L1 reading researchers (e.g. Wade, Schraw, Buxton, &

Hayes, 1993) have pursued ways to make expository texts more interesting by embedding personalized anecdotes and highly interesting but nonessential details. They found this kind of interesting but unimportant information to be effective in bringing about interests but not necessarily in facilitating learning, and therefore termed it seductive interests (Garner, Gillingham, & White, 1989). Studies (e.g. Wade et al., 1993) have found that adding seductive details to texts does not facilitate, and may even interfere with, the learning of important information. After all, attention given to highly interesting information, as the relative L1 literature suggests, may be quite different from attention given to important but uninteresting kinds of information.

The nature of the Self Appraisal treatment seems to be quite close to those of seductive details embedded in texts by L1 reading researchers. The fact that the majority of participants who preferred Self Appraisal treatment viewed it as interesting and those who disliked it considered it as irrelevant of the EAP text makes the Self Appraisal treatment appear to be similar to the seductive interests. Since most reading researchers have agreed on the effects of seductive details in texts and at the same time revealed their reservation on the possibility of such effects leading to ultimate learning, the effect of Self Appraisal materials should be viewed with similar cautions.

Implications for Foreign Language Pedagogy

Although treatment effects were not found to be significant as expected, the findings of this study have implications on classroom pedagogy and material selection.

Classroom Practice

First, the difference between participants of the two sites in pretest and dependent variables should make us more aware of learner characteristics, in particular, the combination of high/low motivation with low/high proficiency. High achievers may not have high motivation and those having high motivation may not necessarily have higher language proficiency. A better understanding on student characteristics will help us make informed pedagogical decisions.

Second, the fact that treatments made no difference for Site A participants in terms of research questions 2, 3, 4, and 5 while there were differences for Site B participants in research questions 2, 4, and 5 may have to do with the characteristics of these two groups of students. As mentioned in Chapter Two, Keller’s (1987c) guidelines for designing motivation into instruction include an assessment for learners’ original motivation level.

Keller asks teachers not to irritate or demotivate students if the motivation level is already high. The different results from two school sites may be explained by Keller’s caution in applying motivational strategies for students whose original motivation level was already high.

Motivational strategies, according to Keller, should be used for students whose motivation is low, such as those from Site B. For highly-motivated students with low language proficiency, such as those from Site A, we should probably concentrate more on ways to facilitate their language for the major reading tasks.

Third, learners’ individual differences, in particular their general academic motivation and EFL proficiency, may be related to their ready acceptance of specific types of EAP pedagogical materials, such as the attention-getting strategies in this study. Knowledge

about learners’ orientation may help classroom teachers in making informed judgment for choosing the right kind of facilitation materials. If there exist mismatches, intended effects may be seriously diminished.

Fourth, more efforts should be given to design motivational strategies for students with both lower academic motivation and EFL proficiency. Although treatments such as Self Appraisal seemed to arouse a higher situational motivation in them, teachers should be more cautious about such situational effect. Lessons from the seductive interest research in the L1 reading area inform us that materials of this type may bring about attention from learners who originally are not interested in the content itself. However, in order for an aroused initial attention to be directed to learning, subsequent teacher facilitation and guidance to the major objectives of learning are especially important.

Finally, the two types of treatments, language-oriented and motivation-oriented ones, seemed to influence students in the anticipated direction, even though the magnitude of effect did not turn out to be a robust one. The Vocabulary List treatment generally helped participants to comprehend the articles and the Self Appraisal and Case Study treatments enhanced situational motivation in general. From the written responses provided by participants for their preferences over treatments, the Case Study treatment seemed to, in addition to serve its motivational purposes, contribute to comprehension facilitation and may be viewed as having appealed to both motivation and comprehension. Although in the design of this study, the two types of treatments were used for comparison for research purposes, in everyday classroom practices these facilitations do not have to be exclusive of each other and teachers should use discretion in deciding what best serves the learning purposes for their particular learner groups.

Material Selection and Adaptation

The treatment effect on pre-reading situational motivation for Site B participants yields

implications that supplementary materials in the content-area textbooks are at least one resource for language teachers to draw on for the purpose of background facilitation, attention arousal, and maybe eventually language learning. Some of these materials may have been researched and refined over the years by specialists in that field and are usually related to the content of texts. While learners may perceive the relevance of supplementary materials differently, some did indicate higher interest on these materials. In the past, L2 reading research has not reported the use of such materials probably due to the difficulty of the language itself for students or a lack of teacher attention to these types of materials.

Reviewing, selecting, adapting, and translating some short segments of these types of materials into learners’ L1 may help EFL teachers add some unique elements into the EAP lessons and get students to be more involved in the reading of content.

There also seems to be a need for academic-purpose materials that are especially designed for EFL learners. While authentic content-area textbooks are full of supplementary materials that may provide interesting background knowledge, they may be beyond EFL learners’ English proficiency levels. If EFL and content-area professionals can choose and edit the materials, adding linguistic elements and translating useful information into L1, the resulting texts tailored specifically for EFL students may better meet EFL learners’ needs.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study provides some empirical evidence on the effectiveness of motivational strategies in an EAP reading situation and for the first time opens up a possible new research area on the relationship between learner characteristics (General Academic Motivation and EFL Reading Comprehension) and the types of motivational materials they prefer. Some cautions, however, should be exercised in interpreting the results from this study.

On Participants

The participants in this study were either juniors and seniors majoring in International Trade from a private university of science and technology or freshmen in the school of business with various majors from a national university. They were not selected through random sampling and the interpretation of results should be generalized with care.

Differences found in these two school sites may be attributable in part to their specific learner characteristics and learning experiences and therefore the results should be inferred carefully with specific learner groups in mind. Using different learner groups, such as senior Engineering majors from a national university, may reveal different pictures of the nature and impact of motivational strategies on EAP reading motivation and comprehension.

On the Length and Difficulty of Texts

In designing the reading experiments, I tried to maintain the necessary length and difficulty of authentic EAP reading in the articles to reflect the real requirements students encountered in reading their textbooks. However, because of concerns on motivational strategies and the necessity to control unnecessary interference from instruction, whether learners are able to cope with articles of such length and complexity without teacher intervention during the process of reading was not addressed. The results seem to suggest that unless learners are already familiar with micro skills needed in reading long texts, experienced EFL learners as they are, still need much guidance to carry out such learning tasks to a more satisfactory level. In order to rule out possible confounding factors such as tiredness from reading long texts, or frustration encountered in the reading process, future research may break down the authentic articles into more manageable passages for learners to complete during class hours. The difficulty of texts, however, should probably not be altered unless linguistically simplified EAP course books become widely available in the marketplace.

As mentioned in Chapter One, Chang and Lehman’s (2002) study was the only empirical one involving an L2 on the effectiveness of motivational strategies. While Chang and Lehman (2002) found significant positive effect of relevance-oriented motivational strategies on both situational motivation and comprehension, this study, with a more complicated EAP-reading task and more related variables accounted for, found that attention-oriented strategies had effects on pre-reading situational motivation with only one of the two student groups in only one of the three articles, and no effects on comprehension. Among the four differences between these two studies as discussed in Chapter Three, the difference of learning tasks in length and complexity looks like a major cause of the difference in results in addition to the motivational components chosen. Although Chang and Lehman (2002) did not provide readability information for their experiment material, a calculation for the sample content of textual introduction in a video segment they showed in a figure tells us that the grade level required was 8.9, while what required for the texts in this study was a grade level of 12 or so. The levels of task difficulty were thus very different between their study and mine and may induce fundamentally different results on the effectiveness of motivational strategies. Replications for these studies should try to control the length and difficulty of texts to make comparison of results possible.

On the Delivery of Treatment

In order to keep the time spent on treatment materials to a minimum so that enough class time could be allocated to the reading task itself, all treatment materials were designed into a one-page written instruction with similar guiding questions. None of the treatment materials, however, was fully elaborated by the researcher or discussed by students in class. Final written responses from participants indicated that some of them had doubts on the relevance of treatment materials to the articles and some felt that lack of discussion on the guiding questions left them in a state of perplexity. The manipulation of treatment materials in this

experiment thus did not adequately reflect most classroom situations where either more time is given to class discussion or the treatment materials are assigned before class meetings.

The reservations students had on the treatments as indicated in the reasons they provided may lessen if all the guiding questions had been discussed and as a result the effectiveness of these motivational strategies may be fully explored. This technical issue should be considered as an element for future researchers interested in studying similar motivational strategies.

Other than their difference in nature and purpose, the three treatments also differed in their formats. The Vocabulary List treatments were lists of words in isolation for language learning and the format was more familiar to participants in their past learning experiences.

The Self Appraisal and Case Study treatments, both in L1, were self-sufficient units which either involve phrases (Self Appraisal) or have complicated sentential structure and longer paragraphs (Case Study). The different effects observed in this study, though few, may partly be due to such difference in presentation formats in addition to a difference in the nature and purpose of treatments. Future research should account for this difference and keep the observed treatment effect one of content only.

On Research Design

The order effects of treatments were not taken into consideration in the design of this study. Participants were randomly assigned to any of the three groups receiving three treatments in different order. The three orders given were (1) Vocabulary List, followed by Self-Appraisal and Case Study; (2) Self-Appraisal, followed by Case Study and Vocabulary List; and (3) Case Study, followed by Vocabulary List and Self-Appraisal. There still existed three other possible sequences, such as Vocabulary List, followed first by Case Study and then by Self-Appraisal. Although the sequence of treatments did not seem to matter in our understanding of the problem because the possible carry-over effect attributable to treatments at the first 10 minutes of a 60-minute class meeting to the next weekly meeting should have

been diluted by the intensity of the 50-minute reading task, future research may take order effects into consideration in the design of the experiment.

Moreover, because of the design, participants’ preferences over treatments were actually based on their comparison among three treatments for three different articles, instead of three treatments for the same article. If future research can use a design that enables learners to do a direct comparison, factors other than the treatments can be more successfully controlled.

On the Relation Between Preference and Learner Characteristics

One major finding from this study is the relation between learner preference and their individual differences from the fifth research question for Site B participants. Though never discussed in previous L2 motivation literature, this relation seems to point out a potential direction for future research. Efforts should be devoted to a more thorough investigation of learner characteristics and how students with distinctive characteristics perceive motivational materials differently. Research of this type may probably bring our understanding of L2 motivation to another level and benefit the construction of theories on learning motivation.

On the Construction and Refinement of L2 Motivation Theories

As discussed under research questions 2 and 4, learners’ relative language proficiency level compared to the proficiency level required by the task seemed to play a role in influencing their situational motivation. In the discussions for question 2, it was found that when participants with a relatively lower proficiency and a higher trait motivation encountered more difficult L2 tasks, their state motivation level seemed to be brought down.

When we compared the three treatments, Vocabulary List, although not designed for the purpose of motivation, did not appear to be less motivating for students. In the discussions for question 4, participants’ voices indicated that language support may also motivate them when they perceive it as facilitative for comprehension. As discussed earlier, theories outside of the L2 field may not need to account for an L2 element since it could be explained

in other more general components such as confidence or task value. For an L2-specific motivation theory, especially a theory accounting for the situational characteristics of L2 motivation, a component specifically on learners’ relative L2 proficiency level against the proficiency level required by the task is probably necessary. This L2 proficiency component, however, was not included in any of the L2 motivation theories that have been reviewed in this study. In order to explain the various counter-intuitive phenomena observed in this empirical study, the inclusion of an L2 proficiency is worth serious considerations and more research efforts for further refinement of existing L2 motivation theories.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides empirical evidence that attention-getting pre-reading exercises do not generally have strong effects on learners’ situational motivation in an EAP reading situation as theories of motivational strategies have suggested. But in some situations, specific attention-oriented materials did enhance pre-reading situational motivation more successfully. Language-oriented pre-reading materials, on the other hand, did not produce significantly higher comprehension for EAP reading, either. The results remind us to be more cautious about theories borrowed from outside the L2 field and to take into account the complicated nature of EAP reading. Learners’ preferences over different types of treatments seem to be varied with subjective reasons. Students’ preference was related to their level of General Academic Motivation and EFL Reading Comprehension – students with higher academic motivation and EFL proficiency tend to be attracted by inquiry arousal and those with lower academic motivation by perceptual arousal. This result highlights a potentially important direction for L2 motivation research. More importantly, the inclusion of an L2 proficiency element is suggested for the construction and refinement of L2 motivation theories.