College Students’ Perceptions of Classroom

Atmosphere and Assessment Criteria in a General

Education Gender Course in Taiwan

Su-fen Liu12Department of Marketing and Distribution Management

National Pingtung Institute of Commerce, Pingtung, Taiwan, Republic of China

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to identify students’ perceptions of classroom atmosphere and assessment criteria in a general education gender course in a four-year college in Taiwan. A total of 312 college students completed questionnaires in the school years of 2007, 2008, and 2009. The students consist of 86 males and 222 females, and 64 freshmen, 104 sophomores, 74 juniors, and 68 seniors. Their data were merged for statistical analysis. The results show that students measured by a semantic differential scale felt relaxed, interested, willing to talk, encouraging, happy, and cheerful during the class. Gender is a significant factor (p<.05) impacting how students felt on four of the six measures with males scoring lower than females. Age is also a significant factor (p<.05) on five of the six measures with freshmen and sophomores scoring lower than juniors and seniors. The study also suggests that the male and female students would have perceived the course differently had a male teacher taught this course. As for students’ assessment criteria, a majority of students agreed with the criteria and percentages assigned by the instructor.

Keywords: Classroom Atmosphere, Assessment Criteria, General Education Gender Course, Taiwan.

1

Address correspondence to Su-fen Liu, National Pingtung Institute of Commerce, Department of Marketing and Distribution Management, No. 51, Min Sheng East Road, Pingtung City, Pingtung County 900, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: sfliu@npic.edu.tw

2

Introduction

The Gender Equity Education Act was passed in 2004 in Taiwan to promote gender equity, eliminate gender discrimination, and improve and establish education resources of gender equity. Article 17 of the Act states, “The school shall design curriculum and activities to encourage students to develop their potential and shall not discriminate students on the basis of their gender. … Universities and colleges shall offer a wide range of courses on gender studies.” As gender equity becomes one of the important issues addressed by many higher education institutions on the global scale, it is important for higher education institutions in Taiwan to embrace the trend, and begin to examine the issue. In other words, the missions of the higher education should address not the traditionally patriarchal values of society, but rather join its counterparts across the globe to address and carefully examine the issue of gender equity in one’s own socio-cultural context (Arnot, 2009). Given that, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education has encouraged universities and colleges to offer gender-related courses to promote gender equity. Many universities in Taiwan have supported this policy through the founding of a new women study department or program. Those institutions with no women study department or program usually offer gender study courses in the general education curriculum (Liu, 2011).

Literature Review

Students’ Perceptions of Classroom Atmosphere in a General Education

Gender Course

At a time when undergraduate education is becoming increasingly valuable and necessary to succeed in the society, there is a rising interest in the characteristics of college and university classrooms that promote student success (Sears & Hennessey, 1996). General education programs help undergraduate students acquire a base of knowledge common to succeed in society. Discovering that current students could not communicate well or produce products with real world applications, Ghaith (2010) stressed the need for better planning and providing more intensive instruction in general education. Students in the U.S. who complete the new General Education Program are expected to be able to think critically and analytically, integrate knowledge, and draw conclusions from complex information (Stone & Friedman, 2002). Women’s study is one of the many courses offered as general education courses. Therefore, in terms of teaching gender courses as a general education course, one should realize the significance of “the classroom be[ing] a vital realm for exploration, critical thinking, and discussion of gender and sexuality” (Clark, Rand, & Vogt, 2003, p. 2). The classroom atmosphere perceived by students can influence their learning effectiveness in the class and is worth an investigation.

Students’ Perceptions of Course Arrangement Based on the Instructor’s

Gender

Some previous research studies have suggested that students might feel closer to same-gender professors. Behling, Curtis, and Foster (1982) found that students who worked with a same-gender field instructor gave more positive ratings to that instructor than did students who worked with an opposite-gender instructor. However, Crawford and MacLeod (1990) discovered that both male and female students may feel closer to female professors than to male professors. Six years later, with data collected from a women’s college, two coed colleges, and a large university, Sears and Hennessey (1996) revealed that students at the women’s college felt closer to female professors than to male professors. This affinity for female professors held true for both male and female students.

Reviewing the literature on students’ ratings about instructors, Smith, Yoo, Farr, Salmon, and Miller (2007) note a mixed result: Some studies revealed that students, especially male students, perceive male instructors as more competent and highly educated than female instructors, whereas other studies showed that students, especially female students, rank female instructors higher than their male counterparts. Researching College of Communication students, Smith, et al. (2007) concluded that student raters gave better scores to female instructors on items concerning providing encouragement to students to express opinions, instructor receptiveness to new ideas and others’ viewpoints, student opportunity to ask questions, and stimulation of class discussion.

Investigating Taiwan’s elementary and high school gender equity education, Hong, Lawrenz, and Veach (2005) recommended for a continued exploration of the impact of gender-equity education interventions in school settings. To expand the body of literature on gender equity education, Hong, et al (2005) also encouraged future researchers to investigate the influence of teacher variables (e.g., gender, age, subjects taught, gender-equity training) and student variables (e.g., gender, age, grade point average, socioeconomic status) on perceptions. Thus, it is worthwhile to study how differently students perceive the course arrangement when the instructor is a male or a female.

Assessment Criteria in a General Education Gender Course

Teaching affective learning, such as gender equity education, requires new paradigms of assessment. Even when affective learning outcomes are clearly articulated and obviously valued, there are challenges to assess students’ learning outcomes. Shephard (2008) contended that “it is notoriously difficult for teachers to assess performance and give credit for achievement … difficulties relate to the practicality of determining a student’s values so that changes may be monitored” (p.94).

The traditional testing culture is heavily influenced by old paradigms, such as the behaviorist learning theory, which is the belief in objective and standardized testing (Shephard 2008). Multiple choice and open-ended assessments are typical test formats for such a testing culture. According to van de Watering, Gijbels, Dochy, and van der Rijt (2008), in the last few decades, a new learning paradigm has emerged, emphasizing the educational outcomes for students in higher education that are necessary for them to function successfully in today’s society. The instructor encourages students to express themselves and helps make the link between their own personal experiences to larger political, social, cultural, and economic structures that shape their lives. Investigating sexual violence pedagogy in higher education, Bertram and Crowley (2012) further encouraged students to engage in reflective speech, for all speech “offers an opening for others to respond, contradict, and clarify” (p.70).

discussion. When students know their contribution is being graded, they adjust their study habits to be better prepared for classroom discussion.

Due to the nature of gender equity education, standardized tests in a paper-pencil format may not be appropriate as the only criterion to evaluate students’ achievement. To better evaluate students’ abilities and for the purpose of general education, a multi-method assessment involving various criteria such as attendance, participation in discussions, mid-term examination, film reflection papers, and final projects is proposed. According to Birenbaum and Feldman (1998), students will be motivated to perform at their best if they are provided with the assessment format they prefer. In order to encourage students to perform their best in a gender equity course, it is legitimate to understand what assessment criteria students prefer and how they would like to change them if applicable.

Purpose of Study and Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to identify students’ perceptions of a general education gender course, including classroom atmosphere, expected change of course arrangement if the instructor is a male, and achievement assessment criteria with a focus on the analysis of gender and age variables. Gender and age, the two most prominent variables in many gender-related studies, are legitimate variables for further analysis in this study. The research questions are:

1.How do students feel in the gender equity class?

2.Is there any gender or age difference in students’ feelings shown during the gender equity class?

3.What would the students expect to change if the instructor is a male?

4.Is there any gender or age difference in students’ expected change of course arrangements if the instructor is a male?

Methods

Participants

A “Gender Relations” general education course was offered to eight classes from different departments for the school years of 2007, 2008 and 2009 at a four-year vocational college in southern Taiwan. It was a 2-credit course and the class sizes were 32, 39, 44, 46, 47, 51, 54, 59, with a total of 372 students. Questionnaires were administered to students at the last class of each semester. A total of 312 students returned their completed questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 83.87%. The participants consist of 86 (28%) male and 222 (72%) female students, among whom 64 (21%) were freshmen, 104 (33%) sophomores, 74 (24%) juniors, and 68 (22%) seniors.

The Course

The course, “Gender Relations”, was offered as a general education course by a female instructor to students from different departments. There weren’t male instructors available to teach this course. The learning objective of the course was to break students’ deep-rooted sexual stereotypes, change their attitudes toward gender relations, and to embrace a broader definition of gender. After finishing this course, students were expected to respect the gender temperaments and sexual orientation of students and to further develop their future career without the limitation of sexual stereotyping. The major readings of the course were the textbook “Gender Dimensions in Taiwanese Society” (Hwang & You, 2007) and supplementary materials. The curriculum based on the textbook included: sexism, language in shaping and reflecting gender stereotype, heterosexual intimacy, sex and media, homosexuality education, gender power and sexual assault on campus, gendered science and technology, fathers’ care giving role, etc. The content was designed to change students’ attitudes toward gender relations. Promoting offering education to young women on resistance to acquaintance sexual assault, Senn (2013) concluded that an educational program was effective in reducing young women’s general acceptance of rape myths and then changed their attitudes toward gender relations.

engagement, perspective sharing via reflection, and appropriate use of multimedia to trigger responses all provide learning activities in those areas of higher education where affective outcomes are sought and respected. The general education gender course was set up for affective learning. Based on instructors’ observation, Hussain (2012) found that collaborative and cooperative work develops contribution spirit among students who can then overcome their shyness and introversion. To evoke students’ interest in the class, the course used group discussions, film shows, debates, and role plays, which required students’ cooperation. In this study, the instructor set the assessment criteria as follows: Attendance and participation in discussion 20%; film refection papers 30%; mid-term examination 20%; and a final project (debates on controversial issues, such as same-sex marriage and decriminalization of adultery, etc.) 30%. A multi-method evaluation was used to encourage students to articulate their opinions about gender equity both in writing and speaking.

Instrument

This study specifically designed a questionnaire based on the literature review and the instructor’s experience. The measurement instrument entitled “Gender Relations Questionnaire” contains four sections. The first section pertains to demographic data. The second section measures students’ perception of the class atmosphere using a semantic differential scale: Tense vs. Relaxed, Bored vs. Interested, Silent vs. Willing to Talk, Hurt vs. Encouraging, Angry vs. Happy, and Frustrated vs. Cheerful, with 1 denoting a negative end and 8 denoting a positive end. Since the instructor was female, students were also asked: if the instructor is a male, how differently would they perceive the course? The third section lists ten statements related to course arrangement for the students to tick either “increase”, “same”, or “reduce”. The fourth section contains an open-ended question, asking how students preferred to change the assessment criteria, such as attendance and participation in discussion, film reflection papers, mid-term examination, and final project.

Procedures

school years of 2007, 2008 and 2009. Students were asked to complete and return the questionnaires in the last class of each semester and they were told that the questionnaires were to be used for research purpose only. They were assured that their identities were protected by the anonymity of the questionnaire and there was no impact on their final grades. The SPSS 12.0 program was used for data entry and statistical analyses.

Analyses

Data were collected from the returned completed questionnaires. Independent t-tests and Chi-square analyses were employed to identify the difference between gender and age groups, respectively. The α value for statistical significance was set at .05. The open-ended question collected qualitative data about students’ preference for changing the assessment criteria, which was analyzed with the content analysis method.

Results and Discussion

Research Question 1: How do students feel in the gender equity class?

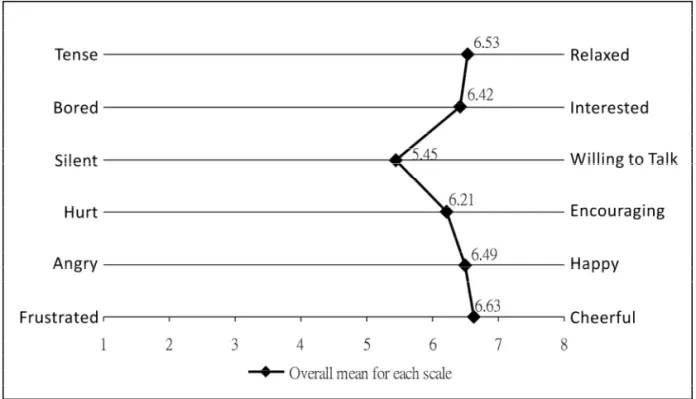

To measure students’ perceptions of the classroom atmosphere, a semantic differential scale was used, with 1 denoting a negative end and 8 denoting a positive end. Figure 1 shows that students felt positively toward the gender course. In the scale from 1 to 8, students rated their feelings from 6.21 to 6.63 toward being Relaxed, Interested, Encouraging, Happy, and Cheerful. Although in the Silent-Willing to Talk scale the average is 5.45, a little less than the other scales, it is still toward the positive side.

Taiwanese students are generally passive in a classroom setting although instructors have tried many ways to encourage them to speak up (Liu, 2011).

Figure 1. Students’ feelings about the general education gender class.

Research Question 2: Is there any gender or age difference in students’

feelings shown during the gender equity class?

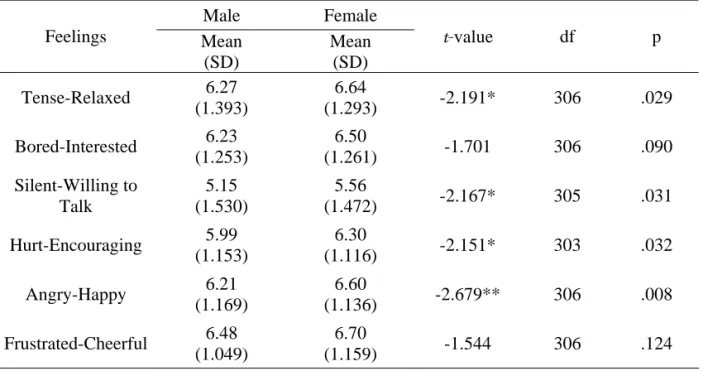

Female students felt more positive than males in four of the six measures. Independent t-tests reveal that female students felt significantly more Relaxed, Willing to Talk, Encouraging, and Happy in the class than males as shown in Table 1. For the Bored-Interested and Frustrated-Cheerful scales, this paper finds no significance. Reviewing the literature, Kahn, Brett, and Holmes (2011) found that women who enter college often have elevated levels of motivation in terms of academic achievement in comparison to their male counterparts. Female students also spend significantly more time studying, completing work, discussing academics outside of the classroom, attending class, and engaging in extracurricular activities. Female students, motivated to learn, tend to feel positive toward a class (Kahn, et al., 2011).

education gender course was designed to break students’ sexual stereotypes, male students faced more challenges when confronted with the criticism against patriarchal society in the class. Therefore, it seemed that men encountered a lesser degree of relaxation, willingness to talk, encouragement, and happiness than women in the gender equity class.

Table 1. The difference between male and female students in their feelings during class sessions Male Female Feelings Mean (SD) Mean (SD) t-value df p Tense-Relaxed 6.27 (1.393) 6.64 (1.293) -2.191* 306 .029 Bored-Interested 6.23 (1.253) 6.50 (1.261) -1.701 306 .090 Silent-Willing to Talk 5.15 (1.530) 5.56 (1.472) -2.167* 305 .031 Hurt-Encouraging 5.99 (1.153) 6.30 (1.116) -2.151* 303 .032 Angry-Happy 6.21 (1.169) 6.60 (1.136) -2.679** 306 .008 Frustrated-Cheerful 6.48 (1.049) 6.70 (1.159) -1.544 306 .124 Note: *: p<.05, ** p<.01.

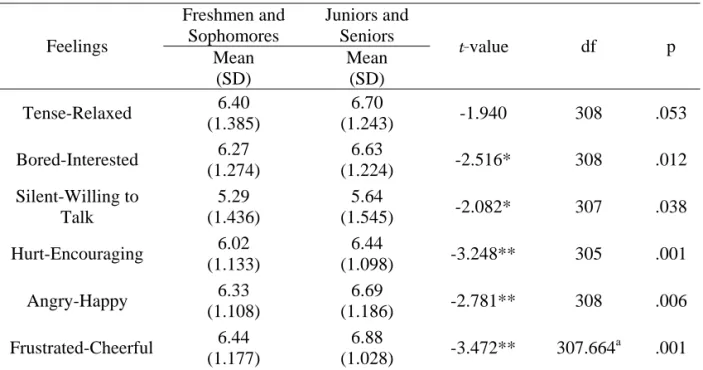

Table 2. The difference between age groups in their feelings during class sessions. Freshmen and Sophomores Juniors and Seniors Feelings Mean (SD) Mean (SD) t-value df p Tense-Relaxed 6.40 (1.385) 6.70 (1.243) -1.940 308 .053 Bored-Interested 6.27 (1.274) 6.63 (1.224) -2.516* 308 .012 Silent-Willing to Talk 5.29 (1.436) 5.64 (1.545) -2.082* 307 .038 Hurt-Encouraging 6.02 (1.133) 6.44 (1.098) -3.248** 305 .001 Angry-Happy 6.33 (1.108) 6.69 (1.186) -2.781** 308 .006 Frustrated-Cheerful 6.44 (1.177) 6.88 (1.028) -3.472** 307.664 a .001 Note: a: Levene test is significant, meaning the distributions of the two groups are not equal and

the degree of freedom is calculated using another complex formula. *: p<.05, **: p<.01.

Research Question 3: What would the students expect to change if the

instructor is a male?

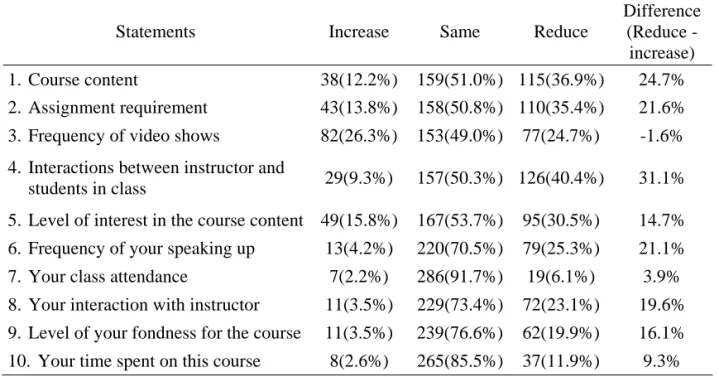

Students were asked to rate their perception of ten statements about the course if the instructor is a male. Table 3 shows that for the things listed on the first five statements pertaining to the instructor’s course arrangement, about half of the students believe a male instructor would do them differently. Among those who expected a change, a higher percentage believe male instructors would do less on (1) course content, (2) assignment requirement, (3) interactions between instructor and students in class, and (4) level of interest in the course content, all of which reflect the instructors’ seriousness towards the course design. The only thing that students would expect a male instructor to do more is “frequency of video shows”, which, in Taiwanese students’ mind, represents a laid-back and not-so-serious class arrangement. The results show that a male instructor is perceived as being less hard-working and less serious than a female counterpart in regard to gender education.

use discussions more than male professors. Basow and Montgomery (2006) also concluded that female professors receive higher ratings than male professors on interpersonal questions, instructor-group interaction, and instructor-individual student interaction. Researching gender gaps in collegiate teaching style, Nelson Laird, Garver, & Niskode-Dossett (2011) found that women faculty members tend toward active and interactive activities to a greater degree than men. Student raters gave better scores to female instructors on items concerning encouragement to students to express opinions, instructor receptiveness to new ideas and others’ viewpoints, student opportunity to ask questions, and stimulation of class discussion (Smith, Yoo, Farr, Salmon, & Miller, 2007).

The last five statements in Table 3 relate to students’ efforts toward the class, and the results show that 70-91% of the students would do the same if the instructor is a male. It is possible that students in this study were self-motivated. Their class attendance and their time spent in the course were not affected, even though they knew that a male instructor would be less serious on most aspects of the course arrangement. Table 3. Perceived change of the course arrangement if the instructor is a male.

Statements Increase Same Reduce

Difference (Reduce - increase)

1. Course content 38(12.2%) 159(51.0%) 115(36.9%) 24.7%

2. Assignment requirement 43(13.8%) 158(50.8%) 110(35.4%) 21.6%

3. Frequency of video shows 82(26.3%) 153(49.0%) 77(24.7%) -1.6%

4. Interactions between instructor and

students in class 29(9.3%) 157(50.3%) 126(40.4%) 31.1%

5. Level of interest in the course content 49(15.8%) 167(53.7%) 95(30.5%) 14.7% 6. Frequency of your speaking up 13(4.2%) 220(70.5%) 79(25.3%) 21.1%

7. Your class attendance 7(2.2%) 286(91.7%) 19(6.1%) 3.9%

Research Question 4: Is there any gender or age difference in students’

expected change of course arrangements if the instructor is a male?

Chi-square analyses reveal three significant differences in Table 4. If the instructor is a male, then male students believed that the course content would remain the same, whereas females believed that it would be reduced (χ2=7.705, p<.05). As for the assignment requirement (χ2=10.633, p<.01) and frequency of speaking up (χ2=16.496, p<.001), male students expect these statements to increase whereas female students expect a reduction. The findings present no significance for the other 7 statements.

Male students perceive a male instructor in a positive way while female students do so negatively. Male students believe that a male instructor will give more assignments and motivate them to speak up, whereas female students believe a male instructor will give fewer assignments and they will feel less comfortable to speak up in the class. The rapport from the same gender instructor is important for students to facilitate learning in the gender class. The study supports the existing literature that female students rank female professors higher (Sears & Hennessey, 1996).

Although there is an implicit assumption that men have no experience of gender oppression and their effectiveness as teachers in a gender class is limited, according to Storrs and Mihelich (1998), similarities in experience of oppression do not provide the only foundation on which rapport is built. Building rapport is also done through acknowledging the diversity of students’ experiences. Storrs and Mihelich (1998) therefore promoted team teaching, involving both male and female instructors. They suggested that teaching about women or gender is not just about oppression, and team teaching would result in better effectiveness.

Table 4. The gender difference in the course arrangement change expected by students if the instructor is a male.

Statements χ2 p

1. Course content 7.705* .021

2. Assignment requirement 10.633** .005

3. Frequency of video shows 0.184 ns

4. Interactions between instructor and students in class 0.490 ns

5. Level of interest in the course content 0.166 ns

6. Frequency of your speaking up 16.496*** .000

7. Your class attendance 0.112 ns

8. Your interaction with instructor 5.445 ns

9. Level of your fondness for the course 0.557 ns

10. Your time spent on this course 0.067 ns

Note: df=2, *: p<.05, **: p<.01, ***:p<.001

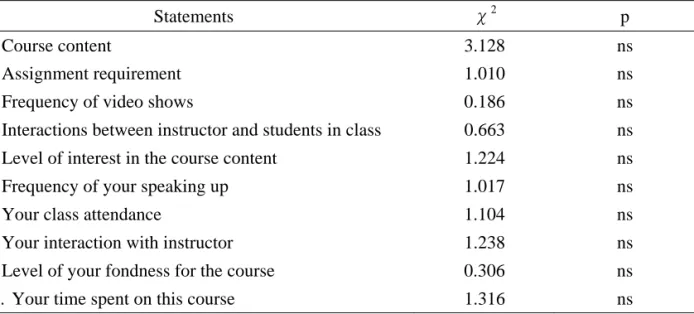

Table 5. The age difference in the course arrangement change expected by students if the instructor is a male.

Statements χ2 p

1. Course content 3.128 ns

2. Assignment requirement 1.010 ns

3. Frequency of video shows 0.186 ns

4. Interactions between instructor and students in class 0.663 ns

5. Level of interest in the course content 1.224 ns

6. Frequency of your speaking up 1.017 ns

7. Your class attendance 1.104 ns

8. Your interaction with instructor 1.238 ns

9. Level of your fondness for the course 0.306 ns

Research Question 5: To what extent do students prefer to change the

percentage of achievement assessment criteria for the gender equity

class?

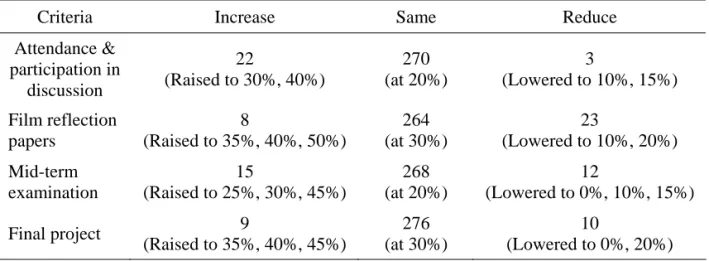

In this study the instructor arbitrarily set the assessment criteria as follows: Attendance and participation in discussion 20%; film reflection papers 30%; mid-term examination 20%; and a final project (both oral and written) 30%. A total of 238 (81%) students agree with the instructor’s assessment criteria and percentage. Fifty-seven (19%) students show a desire to change the percentage.

Table 6 reveals that among the 57 students expressing to change the percentage of achievement assessment criteria, 22 (38.6%) students suggest to raise the percentage of attendance and participation in discussion to 30% or 40%, but 3 of them prefer to lower it to 10% or 15%. As for film reflection papers, 8 students prefer to raise the percentage to 35%, 40% or even 50%, but 23 (40.4%) of them want to lower it to 10% or 20%. As for mid-term examination, 15 (26.3%) students prefer to raise the percentage to 25%, 30%, or 45%, but 12 students wish to lower it to 0%, 10%, or 15%. Among those who prefer to lower the percentages, 5 students suggest no examinations, because they felt students could not learn from them. They prefer to exchange the examination for written papers. As for the final project, 9 students want to raise the percentage to 35%, 40%, or 45%, but 10 others prefer to lower it to 0% or 20%. Among those who want to lower the percentage, 2 students suggest no final project, because they felt there were too many examinations and too high a work load demanded by other courses at the end of the semester.

Ben-Chaim and Zoller (1997) found that students prefer easy-to-take and stress-reducing assessment formats. Studying students’ assessment preferences in a New Learning Environment (NLE), van der Watering, Gijbels, Dochy, and van der Rijt (2008) also noted that students are especially fond of an assessment that allow them to use supporting material. Papers and projects can be considered as assessment formats that allow students to get material from fellow students. This could be one of the reasons why students prefer these assessment formats.

reflection paper criterion. This result is not in line with the existing literature, which shows that papers and projects are preferred. It is possible that students feel it is easier to go to class and spend less time doing so than writing a film reflection paper, which would require students get together to discuss reflection questions after viewing a film. However, this study also testifies that students prefer easy-to-take and stress-reducing assessment formats.

Table 6 shows that the counts for each cell are small and not enough for further investigation. Therefore, this study carries out no further statistical analyses to test gender or age differences in students’ preferred change in the percentage of achievement assessment criteria for the gender equity class.

Table 6. Students’ preferred percentage change of the achievement assessment criteria. Criteria Increase Same Reduce Attendance & participation in discussion 22 (Raised to 30%, 40%) 270 (at 20%) 3 (Lowered to 10%, 15%) Film reflection papers 8 (Raised to 35%, 40%, 50%) 264 (at 30%) 23 (Lowered to 10%, 20%) Mid-term examination 15 (Raised to 25%, 30%, 45%) 268 (at 20%) 12 (Lowered to 0%, 10%, 15%) Final project 9 (Raised to 35%, 40%, 45%) 276 (at 30%) 10 (Lowered to 0%, 20%)

Conclusion

course even if the instructor is a male. Female students tend to engage less in the class when the instructor is a male. Most respondents to the “Gender Relations Questionnaire” agree to the instructor’s assessment criteria. For those who want to change the percentage, mixed results indicate that each individual student may have his/her own preference, and it would be hard for instructors to satisfy them all.

This study observes that female and older students tend to be happy and motivated to learn gender equity knowledge and also agree with multi-method evaluation criteria assigned by the instructor. To motivate male students to learn gender equity knowledge, instructors may need to help them feel more positively toward the class by inviting male instructors to teach gender courses. Accordingly, a mixed-gender team teaching strategy is appropriate for students in gender education courses. Furthermore, it is highly recommended that general education gender courses be offered to older students, such as juniors or seniors instead of younger students, such as freshmen or sophomores in order for them to engage more in the class, feel more positive toward the class, and to learn more.

Limitation and Suggestion for Future Research

References

1. Arnot, M. (2009). Educating the global citizen: The gender challenges of the twenty-first century. In: Educating the gendered citizen sociological engagements with national and global agendas (pp. 223-251). New York, NY: Routledge.

2. Barr, R.B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change Magazine, 27(6), 12-25.

3. Basow, S.A., & Montgomery, S. (2006). Student ratings and professor self-ratings of college teaching: Effects of gender and divisional affiliation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 18, 91-106.

4. Bean, J.C., & Peterson, D. (1998). Grading classroom participation. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 74, 33-40.

5. Behling, J., Curtis, C., & Foster, S. (1982). Impact of sex-role combinations on student performance in field instruction. Journal of Education for Social Work, 18, 93-97.

6. Ben-Chaim, D., & Zoller, U. (1997). Examination-type preferences of secondary school students and their teachers in the science disciplines. Instructional Science, 25(5), 347-367.

7. Bertram, C.C., & Crowley, M.S. (2012). Teaching about sexual violence in higher education: Moving from concern to conscious resistance. Frontiers, 33(1), 63-106. 8. Birenbaum, M., & Feldman, R.A. (1998). Relationships between learning patterns

and attitudes towards two assessment formats. Educational Research, 40(1), 90-97. 9. Centra, J.A., & Gaubatz, N.B. (2000). Is there gender bias in student evaluations of

teaching? Journal of Higher Education, 71, 17-33.

10. Clark, J.E., Rand, E., & Vogt, L. (2003). Climate control, teaching about gender and sexuality in 2003—part 2. Radical Teacher, 67, 2-3.

11. Crawford, M., & MacLeod, M. (1990). Gender in the college classroom: An assessment of the “chilly climate” for women. Sex Roles, 23(3-4), 101-122.

12. Cully, M., & Portuges, C. (Eds.) (1985). Gendered subjects: The dynamics of feminist teaching. New York: Routledge.

13. Findley, B., & Varble, D. (2006). Creating a conducive classroom environment: Classroom management is the key. College Teaching Methods & Styles Journal, 2(3), 1-6.

15. Ghaith, G. (2010). An exploratory study of the achievement of the twenty-first century skills in higher education. Education and Training., 52(6-7), 489-498. 16. Hong, Z., Lawrenz, F., & Veach, P.M. (2005). Investigating Perceptions of Gender

Education by Students and Teachers in Taiwan. The Journal of Educational Research, 98(3). 156-163.

17. Hussain, I. (2012). Use of constructivist approach in higher education: An instructors’ observation. Creative Education, 3(2), 179-184.

18. Hwang, S.L., & You, M.H. (Eds.) (2007). Gender Dimensions in Taiwanese Society, Taipei, Taiwan: Chuliu Publisher.

19. Jaggar, A.M. (1977). Male instructors, feminism, and women’s studies. Teaching Philosophy, 2(3-4), 237-245.

20. Kahn, J.S., Brett, B.L., & Holmes, J.R. (2011). Concerns with men’s academic motivation in higher education: An exploratory investigation of the role of masculinity. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 19(1), 65-82.

21. Kim, Y.K., & Sax, L.J. (2009). Student-Faculty Interaction in Research Universities: Differences by Student Gender, Race, Social Class, and First-Generation Status, 50, 437-459.

22. Klein, S.S. (1985). Handbook for achieving sex equity through education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

23. Landau, J., & Meirovich, G. (2011). Development of students’ emotional intelligence: Participative classroom environments in higher education. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 15(3), 89-104.

24. Liu, S.F. (2011). Instructions and challenges of general education at vocational and technical institutions in Taiwan ─ a focus on gender courses. Taiwan Journal of General Education, 8, 105-133.

25. Nelson Laird, T.F., & Garver, A.K. (2010). The effect of teaching general education courses on deep approaches to learning: How disciplinary context matters. Research in Higher Education, 51, 248-265.

27. Sears, S.R., & Hennessey, A.C. (1996). Students’ perceived closeness to professors: The effects of school, professor, gender, and student gender. Sex Roles, 35, (9/10), 651-658.

28. Senn, C.Y. (2013). Education on resistance to acquaintance sexual assault: Preliminary promise of a new program for young women in high school and university. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 45(1), 24-33.

29. Shephard, K. (2008). Higher education for sustainability: seeking affective learning outcomes. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(1), 87-98. 30. Smith, S.W., Yoo, J.H., Farr, A.C., Salmon, C.T., & Miller, V.D. (2007). The

Influence of Student Sex and Instructor Sex on Student Ratings of Instructors: Results from a College of Communication. Women’s Studies in Communication, 30(1), 64-77.

31. Stone, J., & Friedman, S. (2002). A case study in the integration of assessment and general education: lessons learned from a complex process. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27(2), 199-211.

32. Storrs, D., & Mihelich, J. (1998). Beyond essentialisms: Team teaching gender & sexuality. NWSA Journal, 10(1), 98-118.