Bulletin of Educational Research

December, 2010, Vol. 56 No. 4 pp. 95-138

Hsiou-Huai Wang, Associate Professor, Center for Teacher Education, National Taiwan University

E-mail: wanghs@ntu.edu.tw

Manuscript received: Dec. 18, 2009; Modified: Oct. 13, 2010; Accepted: Dec. 3, 2010.

Diversity within Uniformity: The Dynamics of Government Control and Program Diversity in

Teacher Education Curriculum in Taiwan

H s i o u - H u a i Wa n g A b s t r a c t

The intertwining forces of government-controlled uniformity and program-based diversification have influenced teacher education policies internationally. It is not clear, however, to what extent teacher education curriculum is subject to such dynamics. This paper intends to fill the gap by analyzing the curriculum of secondary teacher education programs in Taiwan, a society that has experienced a swing back and forth between the two forces on teacher education policies over the past six decades. Data on education/

pedagogy courses of 41 secondary education programs were collected, compared and analyzed. The results show that the teacher education curriculum in Taiwan enjoys a limited degree of diversity within a uniform structure. Discussions on the contexts of teacher education policies in Taiwan and their effect on the quality of teachers are provided.

Keywords: teacher education policy, curriculum, government control, program diversity

教育研究集刊

第五十六輯第四期 2010 年 12 月 頁 95-138

王秀槐,臺灣大學師資培育中心副教授 電子郵件為:wanghs@ntu.edu.tw

投稿日期:2009 年 12 月 18 日;修改日期:2010 年 10 月 13 日;採用日期:2010 年 12 月 3 日

一元中的多元:政府管制與多元培育 機制下我國中等教育學程

教育專業課程分析研究

王秀槐

摘要

各國的師資培育政策大都由兩股勢力,包括政府的一元化管制與市場多元化 機制的牽引;但是,這兩股勢力如何影響師資培育課程的制定,仍有待探討。本 文藉由分析我國中等師資培育學程的教育專業課程來探討,在這兩股力量的影響 下,教育專業課程的結構與內涵究竟呈現何種樣貌。研究蒐集國內 41 所中等教 育學程的教育專業課程資料,針對課程結構、開課類型與領域內涵,進行分析、

對照與比較。研究結果顯示,我國師資培育課程在一元化的政策架構下,僅享有 有限的多元空間。本文進一步就造成此一現象背後的師資培育政策脈絡與沿革,

進行說明與探討。

關鍵字: 師資培育政策、教育專業課程、政府管制、多元培育機 制

1. Introduction

The intertwining forces of government-controlled uniformity and program-based diversification have impacted teacher education policies internationally. It is not clear, however, to what extent teacher education curriculum is subject to such dynamics. This paper intends to fill the gap by analyzing the curriculum of secondary teacher education programs in Taiwan, a society that has experienced a swing back and forth between the two forces on teacher education policies over the past six decades. It is interesting to explore how diversified or uniformed is the course structure and courses content offered by teacher education programs across the country. Such investigation may advance our understanding of how the two forces have an impact on the “process” of teacher education.

This article is organized as follows: An overview of relevant literature is first presented in Section 1, followed by a description of the purpose and specific questions for the study, before an account of the research methods was presented in Section 3.

The research outcomes, including: a detailed account of the course structure, offerings, and content of the 41 secondary teacher education programs in Taiwan will be provided in Section 4, followed by an in-depth discussion on the historical and socio-cultural roots of such developments and implications of the findings in the final sections.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Dynamics between governmental control vs. program diversity

Internationally, two opposing forces have been underlying the recent development of teacher education: first, deregulation of teacher education, which argues for program- based deregulation and diversification; and second, regulation of teacher education, advocating stronger governmental control for uniform standards and criteria (Apple,

2001; Cochran-Smith & Fries, 2005; Furlong, Barton, Miles, Whiting, & Whitty, 2000).

Both approaches attempt to pursue teacher quality, yet through contrasting strategies.

The former assumes that diversity and competition among various teacher training institutions will inspire innovations and creativity and ensure the strongest and best to emerge; the latter argues that only through establishing uniformed standards by central authorities can teacher quality be achieved (Apple, 2001; Furlong et al., 2000; Hill, 2006, 2007).

For instance, in the U.S., while diverse teacher training paradigms and alternative teacher training programs have been multiplied, the government has implemented stricter regulations and higher standards for controlling teacher quality and accountability under the current reform movement (Feiman-Nemser, 1990;

Lucas, 1999; Popkewitz, 1995; Tsai, 1997; Zeichner & Conklin, 2005). In the UK, the government has recently intensified its control over the instalment of teacher education programs while loosening regulations to allow some qualified secondary school consortia to take up teacher training (Landman & Ozga, 1995; Lee, 2008). In Germany, while diverse models for teacher education have been developed across the country, the central government has implemented two levels of national teacher qualification examinations to ensure teacher quality (Yang, 1999, 2006). In addition, Japan allows universities to set up diverse teacher education programs with various admission criteria and curriculum standards; however, the government controls the quality in the end through employment screening tests (Liang, 2008; Morris & Williamson, 2000).

Evidence from these countries has demonstrated the ever intertwining tensions between increasing diversification through diverse forms of teacher training and heightened uniformity due to stricter governmental control (Apple, 1995, 2000, 2001; Hill, 2006).

Such dynamics may have a great impact on the input, process, and output of teacher education.

2.2 Impact on teacher education internationally

“Input” refers to the mechanism with which teacher education programs select

their students. It is found that in these countries, the government tend to maintain a relatively lenient control on the student selection process and allows individual teacher education programs/institutions to set diverse criteria to admit students according to their own institutional goals and definitions of teacher quality. Rarely a centralized selection process or uniformed set of selection standards were prescribed for individual institutions/programs to comply (Halstead, 2003; Wang & Fwu, 2007).

“Output” refers to the certification of qualified teachers at the end point of teacher education. It is found that governments usually take stricter control to ensure the quality of graduates from various teacher education programs by setting regional/

national standards and requiring qualification examinations or certified standardized tests (Blömeke, 2006; Wang, 2004; Yang, Chen, & Chiang, 2008). For example, in the U.S., those who complete teacher education programs have to pass certain qualification exams on aptitude, subject area knowledge, and pedagogical knowledge mandated by the state and offered by different testing institutions, teacher professional associations, or state boards in order to become certified teachers (Clark & McNergney, 1990; Roth

& Pipho, 1990). In the UK, those who complete a teaching internship have to pass the Qualified Teacher Status skills test in numeracy, literacy, and Information and Communications Technology in order to register with the General Teaching Council for England (GTCE) to obtain the Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) (Halstead, 2003;

QTS standards, n.d.). Germany has an even stricter qualification process of two-stage examinations: graduates from teacher education programs have to pass the First State Examination to obtain the qualification for student teaching internship, and after one to two year internship, pass again the Second State Examination in order to obtain the qualified teacher certificate (Blömeke, 2006; Terhart, 2004; Yang, 1999, 2006).

Nevertheless, it is not clear to what degree the “process,” that is, the curriculum offered by teacher education programs, is subject to government control. Relatively little literature is found on systematic analysis of teacher education curriculum, that is, the structure and content of the education/pedagogy courses provided by teacher education programs in a system, to see to what extent it is subject to government

control or program initiatives. Since curriculum is at the very core of teacher education, providing the learning experiences necessary for future teachers, and usually reflects the nation’s political agenda on teacher education and individual institutions/programs’

special missions and goals, it is important to explore how this area of teacher education is shaped by these two opposing forces (Foshay, 2000; Parkay, Anctil, & Hass, 2006).

2.3 The Taiwanese context

In Taiwan, teacher education had been under strict government control since 1949 since the Nationalist government began its nation building process on this island nation. Teachers have been hailed as “guardians of the nation” and teacher education regarded the essential means to educating loyal citizens and efficient labour force. During this era, teacher training was exclusively provided by a small group of government-funded normal universities and teachers’ colleges. Little diversity in teacher education institutions was found (Fwu & Wang, 2002). However, recent reform in teacher education since the enactment of Teacher Education Act in 1994 has opened up the teacher training market to all the universities and colleges in the country. Under the new system, any universities and institutions may join teacher education endeavour and once approved by the Ministry of Education, could recruit students from various departments within the university and train them into future teachers (Fwu & Wang, 2002).

In the new system, there appears to be a much higher level of diversity among teacher training institutions, including: traditional normal universities and teachers’

colleges, academically-oriented public universities and private universities, as well as technological universities and colleges. Depending on their traditions and resources available, these institutions offered teacher education courses through different ways.

Normal universities, blessed with their longstanding status and resources in the field of education, tend to offer teacher education courses through comprehensive colleges of education composed of multiple departments of education. Non-normal academic universities, depending on different degrees of resources and reputations, tend to

provide courses via either college of education, department of education (with several sub-fields in education) or small-scale teacher education program (with a minimum of five faculty members). Technological universities tend to provide courses in a lesser scale through either a department of education or a teacher education program. There seems to be much diversity in the organizational forms of teacher education; however, it is not clear yet if these diverse programs in different types of higher education institutions do offer diverse curriculum to train their students into future teachers.

More specifically, it is not clear if the structure, type and content of courses vary across programs, and if programs differ in their endeavours to initiate program-specific courses.

3. Research Purpose and Questions

The purpose of this study, thus, is to examine the degree of diversification and uniformity in the curriculum of secondary teacher education programs in Taiwan. This issue can be explored in terms of course structure, course offerings, and content areas provided by these programs. The specific research questions include the following:

1) Do the programs vary in their course structure and course taking regulations?

2) Do the programs vary among the number and types of courses they offer?

3) Do the courses offered by these programs vary in their content areas?

4) Do programs’ endeavours to initiate program-specific courses vary with institutional characteristics?

It should be noted that, first, this analysis focuses mainly on the curriculum of secondary school teacher education programs without reference to programs for other levels of education, because these programs comprised the majority of teacher education programs in the country and are thus expected to demonstrate greater, if any, diversity among programs. Second, although the complete curriculum for preparing a well-rounded teacher of a specific teaching subject may include: education/pedagogy courses (such as Educational Psychology, Educational Philosophy etc.), teaching

subjects courses (such as Chinese, Math, Physics, and Biology), and student teaching internship. Among them, the content of teaching subject courses are mainly provided by various academic departments/faculties, and internship depends largely on intern schools’ arrangement; only the education/pedagogy courses are completely provided and controlled by teacher education programs themselves. Thus, this study focuses only on the analysis of education/pedagogy courses; discussion of the teaching subject courses and internship arrangement is beyond the scope of this article.

4. Research Methods

4.1 Data source

As of 2008, a total of 47 secondary teacher education programs had been set up by universities and college in Taiwan (Ministry of Education, 2008). In this study, data was collected from 41 of these programs.1 Data were collected from the following three sources. First, the author downloaded the following documents from the official website of each of the 41 programs during the period of April 2008, including: 1) official program descriptions; 2) course-taking regulations; and 3) course catalogues of each program for the year 2008. A total of 41 catalogues/descriptions of course offering were obtained, and a total of more than 500 pages of data/information were collected as the main source for analysis. As websites are the major channel for teacher education programs to publicize their courses, the information contained on the website is considered official, up-to-date, and accurate. Second, official evaluation reports from the Ministry of Education on the overall performance of teacher education programs were used to corroborate the data obtained from website documents. Third, literature

1 The researchers were unable to obtain data from the other six programs through internet or phone inquiries after successive attempts. Therefore, these programs were not included in this study.

on the comparative studies of teacher education system and curriculum was collected to deepen the researcher’s understanding for data analysis.

4.2 Analysis

This study utilized documentary analysis as the primary method of data analysis (Hsieh, 2006). The author used the following steps: first to determine the main focuses for analysis based on the purpose/question of the study, then to categorize and organize the data according to the main focuses/themes, and then distil conspicuous patterns in the data to obtain meaningful results. Based on the research purpose of this study, that is, to determine whether diversity is achieved among teacher education program courses, the data were analyzed from the following four angles. The first angle focused on the course structure of specific programs. The author analyzed the program descriptions and course-taking regulations of the 41 programs and synthesized the number of credits required, types of courses offered, and distribution of required and elective courses stipulated by these programs. These regulations were compared with the Ministry of Education (MOE) standard version listed on the MOE website to determine how much the program regulations for course structure diverged from the MOE regulations.

The second analysis centred on the diversity of the required and elective courses offered by the 41 programs. Using the information from the course catalogues, the author first made a complete list of all the courses offered by the 41 programs and then calculated the percentages of programs offering each course in order to see the diversity of course offerings among programs. The author further computed the percentages between MOE standard courses and program-initiated elective courses in each program to see what proportions of such program-initiated courses are in the entire curriculum offered by each program.

The third dimension of analysis focused on the content areas of these courses.

In order to delve into the diversity of the substantive knowledge areas contained in the courses offered by the programs, the author classified the courses into six areas

according to their substantive curriculum fields, and then compared and contrasted the courses offered in each area.

Lastly, considering the historical development of higher education and teacher education in Taiwan, the type of institution and scale of programs tend to have a bearing on teacher education course offering. The demarcation of academic vs. technological, public vs. private, and normal vs. non-normal institution is significant. Thus, the author divided the 41 programs based on their institutional traits into the following six types: 1) five normal universities with a comprehensive college of education (NU- CE); 2) eight non-normal universities with a college of education (NNU-CE); 3) eight non-normal universities with a department of education (NNU-DE); 4) seven non- normal universities with a teacher education program (NNU-TE); 5) one technological university with a department of education (TU-DE); and 6) twelve technological universities with a teacher education program (TU-TE).

5. Research Outcomes

The findings from the above analyses are presented in the following three sections, including: course structure, course offerings, and content area.

5.1 Course structure

First of all, it is found that according to MOE regulations, the national curriculum for secondary teacher education are designed based on the discipline-based modularized curriculum model (Null, 2007; Wu, 2006), that is, a curriculum that tends to break up the professional knowledge necessary for a teacher candidate into a series of separate and differentiated courses specialized in various sub-disciplines of education, such as Educational Psychology, Educational Sociology, or Guidance and Counselling etc. A series of well-structured modularized credit courses is designed and it is assumed that after students completed such course sequence, they will acquire the necessary professional knowledge for a teacher.

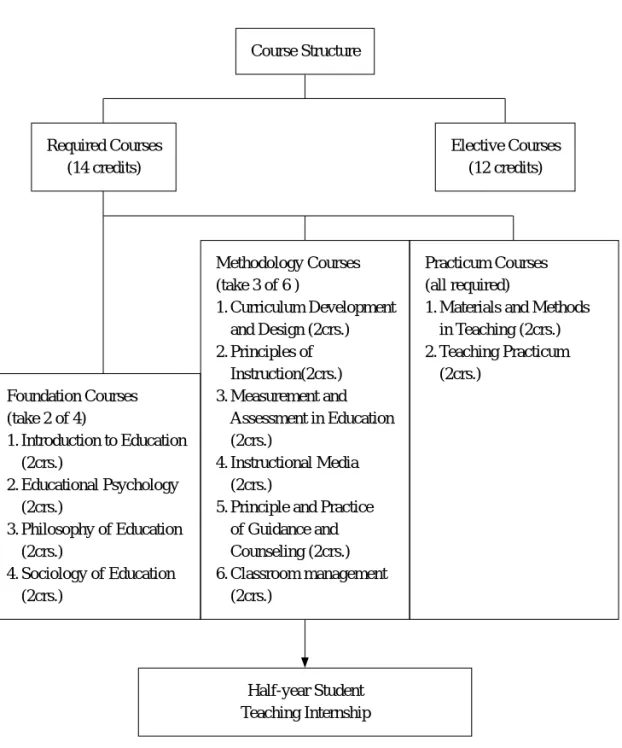

Such curriculum is composed of four categories of courses: 1) four Educational Foundations courses, including: Introduction to Education, Educational Psychology, Philosophy of Education, and Sociology of Education; 2) six Educational Methodology courses, including: Curriculum Development and Design, Principles of Instruction, Measurement and Assessment in Education, Instructional Media, Principles and Practice of Guidance and Counselling, and Classroom Management; 3) two Practicum courses, including: Materials and Methods in Teaching and Teaching Practicum; and 4) a number of Electives courses. A student must take a certain number of courses among these four categories to reach the minimum of 26 credits required, including two (4 credits) out of the four Foundations courses, three (6 credits) out of the six Methodology courses, and the two Practicum courses (four credits), totalling seven required courses (14 credits) and 6 electives (12 credits), and then takes a half-year full-time student teaching internship (equivalent to four credits), in order to fulfil the requirements for obtaining teacher certification (MOE, 2003) (see Figure 1).

After a detailed examination of the course list and course-taking regulations of the 41 programs, it is found that they had extremely similar course structures and course- taking regulations in conformity to the above MOE regulations. All the programs ask their students to take at least 26 credits and to choose 5 of the 10 Foundation and Methodology courses. Only in Practicum courses some variation was found, by adding 1 or 2 more courses or adding the number of credits for the courses. After the students completed the 26 credit courses in university, they are placed in intern schools for half- year full-time student teaching.

In sum, a uniformed course structure does exist among all the secondary teacher education programs in that the category of courses, number of credits required, and

Course Structure

Half-year Student Teaching Internship Methodology Courses (take 3 of 6 )

1. Curriculum Development and Design (2crs.) 2. Principles of

Instruction(2crs.) 3. Measurement and

Assessment in Education (2crs.)

4. Instructional Media (2crs.)

5. Principle and Practice of Guidance and Counseling (2crs.) 6. Classroom management

(2crs.) Foundation Courses

(take 2 of 4)

1. Introduction to Education (2crs.)

2. Educational Psychology (2crs.)

3. Philosophy of Education (2crs.)

4. Sociology of Education (2crs.)

Required Courses (14 credits)

Elective Courses (12 credits)

Practicum Courses (all required)

1. Materials and Methods in Teaching (2crs.) 2. Teaching Practicum

(2crs.)

Figure 1 Course structure for secondary teacher education

distribution of credits among different categories are basically the same. All the programs follow the subject-based curriculum model prescribed by the Ministry of Education. No alternative curriculum models were found. No programs developed their curriculum based on integrated broad-based courses in which courses are organized in a broader field of knowledge, for example, integrating Educational Psychology, Educational Philosophy and Educational Sociology together into a course called Educational Foundation so that students may gain a more holistic understanding of complex educational issues (Kim, Andrews, & Carr, 2004); nor did programs develop

“blended” type of curriculum that rotates university coursework and school-site internship to first place students in school site and then provide university-based classes for theoretical learning and then place them in school again for integrated application (Maxie, 2001); nor did programs develop a field-intensive curriculum that places students mainly in partnership schools and learn through daily school practice with periodical seminars offered on site by joint faculty and school supervisors (Halstead, 2003; Maandag, Deinum, Hofman, & Buitink, 2007). Without such alternative curriculum models, it is found that the course structure of all the programs are basically the same, conforming to government regulations.

5.2 Course offerings

Under such a uniformed curriculum paradigm, it is worth further exploring if there is space for programs to offer diverse courses within the set structures and categories and if they did provide courses other than those stipulated by the Ministry of Education to fulfil specific program goals and meet students’ needs. While a truly uniformed curriculum across programs should see that all the programs offer the same set of courses without variation and a completely diverse curriculum should be the one in which no programs offer the same courses, a detailed analysis of all the courses offered by the 41 programs reveals a mixed picture between the two.

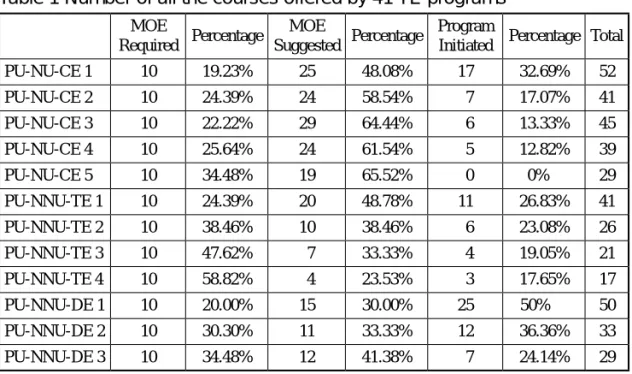

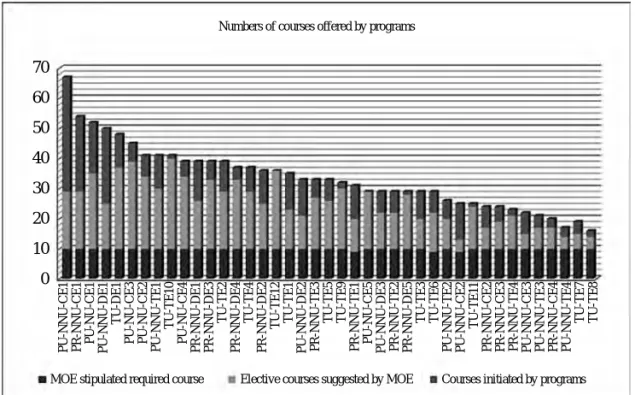

First of all, a total of 183 different courses were offered by these programs in the years 2007-2008. There were three types of courses: 1) 10 MOE stipulated required

courses; 2) 30 MOE suggested elective courses; and 3) the remaining 141 elective courses initiated by individual programs. As the first two types represent the core curriculum stipulated by the government, the third type was the indicator of how diverse these programs offer their courses. Table 1 listed the number and percentage of these three types of courses offered by all the 41 programs. It is found that all the programs (except very few ones) did offer all of the ten MOE stipulated courses;

however, these programs varied greatly in offering the second type (MOE suggested) of courses, from the least of 4 to the maximum of 29 courses. The variation spanned even greater in the third type (program-initiated) of courses, from zero to the maximum of 38. Lastly, the total number of courses offered by each of these programs spanned from the minimum of 17 to the maximum of 67. These programs altogether offered a total of 171 different elective courses beyond MOE stipulation in the third category. To delete redundancy among them, it is found there were a total of 141 different courses initiated by the programs themselves.

Table 1 Number of all the courses offered by 41 TE programs MOE

Required Percentage MOE

Suggested Percentage Program

Initiated Percentage Total

PU-NU-CE 1 10 19.23% 25 48.08% 17 32.69% 52

PU-NU-CE 2 10 24.39% 24 58.54% 7 17.07% 41

PU-NU-CE 3 10 22.22% 29 64.44% 6 13.33% 45

PU-NU-CE 4 10 25.64% 24 61.54% 5 12.82% 39

PU-NU-CE 5 10 34.48% 19 65.52% 0 0% 29

PU-NNU-TE 1 10 24.39% 20 48.78% 11 26.83% 41

PU-NNU-TE 2 10 38.46% 10 38.46% 6 23.08% 26

PU-NNU-TE 3 10 47.62% 7 33.33% 4 19.05% 21

PU-NNU-TE 4 10 58.82% 4 23.53% 3 17.65% 17

PU-NNU-DE 1 10 20.00% 15 30.00% 25 50% 50

PU-NNU-DE 2 10 30.30% 11 33.33% 12 36.36% 33

PU-NNU-DE 3 10 34.48% 12 41.38% 7 24.14% 29

MOE

Required Percentage MOE

Suggested Percentage Program

Initiated Percentage Total

PU-NNU-CE 1 10 14.93% 19 28.36% 38 56.72% 67

PU-NNU-CE 2 9 36.00% 4 16.00% 12 48% 25

PU-NNU-CE 3 10 45.45% 5 22.73% 7 31.82% 22

PU-NNU-TE 1 9 29.03% 11 35.48% 11 35.48% 31

PU-NNU-TE 2 10 34.48% 12 41.38% 7 24.14% 29

PU-NNU-TE 3 10 30.30% 17 51.52% 6 18.18% 33

PU-NNU-TE 4 10 43.48% 11 47.83% 2 8.70% 23

PU-NNU-DE 1 10 25.64% 16 41.03% 13 33.33% 39

PU-NNU-DE 2 10 27.78% 15 41.67% 11 30.56% 36

PU-NNU-DE 3 10 25.64% 23 58.97% 6 15.38% 39

PU-NNU-DE 4 10 27.03% 23 62.16% 4 10.81% 37

PU-NNU-DE 5 10 34.48% 18 62.07% 1 3.45% 29

PU-NNU-CE 1 10 18.52% 19 35.19% 25 46.30% 54

PU-NNU-CE 2 10 41.67% 7 29.17% 7 29.17% 24

PU-NNU-CE 3 10 41.67% 9 37.50% 5 20.83% 24

PU-NNU-CE 4 10 50.00% 7 35.00% 3 15% 20

TU-TE 1 10 28.57% 13 37.14% 12 34.29% 35

TU-TE 2 10 25.64% 19 48.72% 10 25.64% 39

TU-TE 3 10 34.48% 10 34.48% 9 31.03% 29

TU-TE 4 10 27.03% 19 51.35% 8 21.62% 37

TU-TE 5 10 30.30% 16 48.48% 7 21.21% 33

TU-TE 6 9 31.03% 13 44.83% 7 24.14% 29

TU-TE 7 10 52.63% 5 26.32% 4 21.05% 19

TU-TE 8 10 62.50% 4 25.00% 2 12.50% 16

TU-TE 9 10 31.25% 20 62.50% 2 6.25% 32

TU-TE 10 10 24.39% 30 73.17% 1 2.44% 41

TU-TE 11 10 40.00% 14 56.00% 1 4% 25

TU-TE 12 10 27.78% 26 72.22% 0 0% 36

TU-DE 1 10 20.83% 27 56.25% 11 22.92% 48

Table 1 (continued)

To present the result in a more graphical way, Figure 2 clearly showed that on the one hand, almost all the programs offered the ten MOE stipulated required courses (the bottom layer), and all the programs did provide some courses out of the thirty MOE suggested courses (the middle layer), indicating the tendency of these programs to conform to the MOE core curriculum. However, all these programs altogether have created a diverse set of 141 elective courses beyond MOE stipulation in the third category (the top layer), signifying the degree of autonomy the programs enjoy to offer their own courses.

Numbers of courses offered by programs

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0

PU-NNU-CE1 PR-NNU-CE1 PU-NU-CE1 PU-NNU-DE1 TU-DE1 PU-NU-CE3 PU-NU-CE2 PU-NNU-TE1 TU-TE10 PU-NU-CE4 PR-NNU-DE1 PR-NNU-DE3 TU-TE2 PR-NNU-DE4 TU-TE4 PR-NNU-DE2 TU-TE12 TU-TE1 PU-NNU-DE2 PR-NNU-TE3 TU-TE5 TU-TE9 PR-NNU-TE1 PU-NU-CE5 PU-NNU-DE3 PR-NNU-TE2 PR-NNU-DE5 TU-TE3 TU-TE6 PU-NNU-TE2 PU-NNU-CE2 TU-TE11 PR-NNU-CE2 PR-NNU-CE3 PR-NNU-TE4 PU-NNU-TE3 PR-NNU-CE4 TU-TE7 TU-TE8

PU-NNU-CE3 PU-NNU-TE4

Courses initiated by programs MOE stipulated required course Elective courses suggested by MOE

Figure 2 Numbers of courses offered by programs

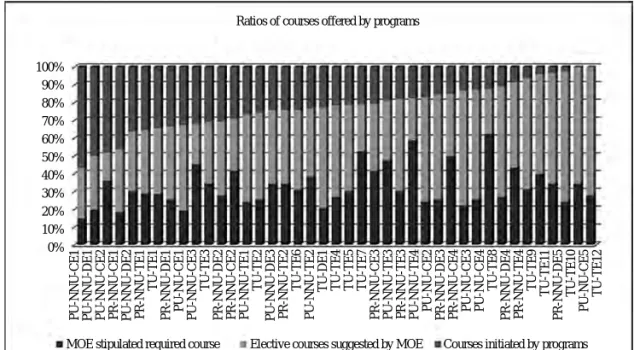

In addition to examining the total number of the three types of courses provided across the programs, the author also calculated the ratio of each type of courses within the entire curriculum of each program to see how substantial the proportion of the curriculum was subject to government control or program autonomy. Figure 3 illustrates the percentages of three types of courses within the curriculum of each of

the 41 programs. As can be seen, the proportions of the first type of courses (MOE stipulated required courses) in the curriculum varied (from 15% to 59%), with an average of 33% across all 41 programs. The ratios of the second type (MOE suggested elective courses) ranged more widely (from 16% to 73%), with an average of 45%

across the programs. And the proportions of the third type (program initiated elective courses) varied even more greatly (from 0% to 57%), with an average of 23% across the programs. Comparing the average proportions of each type of course found that these programs did offer a relatively higher proportion of the first (33%) and second type (45%) of courses, the combination of both types even exceeding 78%, and provided relatively smaller proportions of the third type (23%). While the first two types of courses may represent how programs conform to the MOE control scheme and the third type indicates the degree by which programs are free to develop their own curriculums, such results show that these programs on average were more apt to conform to MOE regulations than to devise a diverse range of courses of their own.

Ratios of courses offered by programs

PU-NNU-CE1 PU-NNU-DE1 PU-NNU-CE2 PR-NNU-CE1 PU-NNU-DE2 PR-NNU-TE1 TU-TE1 PR-NNU-DE1 PU-NU-CE1 PU-NNU-CE3 TU-TE3 PR-NNU-DE2 PR-NNU-CE2 PU-NNU-TE1 TU-TE2 PU-NNU-DE3 PR-NNU-TE2 TU-TE6 PU-NNU-TE2 TU-DE1 TU-TE4 TU-TE5 TU-TE7 PR-NNU-CE3 PU-NNU-TE3 PR-NNU-TE3 PU-NNU-TE4 PU-NU-CE2 PR-NNU-DE3 PR-NNU-CE4 PU-NU-CE3 PU-NU-CE4 TU-TE8 PR-NNU-DE4 PR-NNU-TE4 TU-TE11 PR-NNU-DE5 PU-NU-CE5 TU-TE12TU-TE9 TU-TE10 100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

MOE stipulated required course Elective courses suggested by MOE Courses initiated by programs

Figure 3 Ratio of courses offered by programs

5.3 Content Area

In addition to examining the number and ratio of different types of courses offered by the teacher education programs, it is important to investigate the content areas covered by these courses in order to grasp the width and depth of the professional knowledge delivered to students in the process of teacher education.

The 183 courses provided by all the programs can be classified into six sub-fields.

They are: 1) Educational thoughts & philosophy; 2) Human development, psychology

& counselling; 3) Curriculum, instruction & assessment; 4) Administration and social policy; 5) teacher professional development; and 6) Education for specialized areas.

Within each content area, the author further differentiated the courses into the three types of courses, including MOE required courses, MOE suggested elective courses, and program-initiated elective courses. Further analyses were conducted to examine the diversity in focus within each sub-field to see how the program-initiated courses strengthen, complement, or diverge from the MOE core courses.

5.3.1 Educational thoughts/philosophy

In the area of “Educational Thoughts and Foundations,” the MOE stipulates two required courses and six suggested courses, focusing on the general introduction and fundamental knowledge of educational philosophy and contemporary issues in educational thoughts. In this area, the programs did initiate an additional 19 courses, first adding on some courses on the topics of contemporary thoughts in education, such as contemporary issues of education, educational thoughts in the modern time, post- modernism and feminism, humanistic education, and cultural philosophy; second, adding on courses on some interesting emerging areas, such as open education, affective education, life and death education; further, providing such courses with distinctly indigenous perspectives as inquiry to Taiwan education and meditation on Buddhist wisdom. In this way, we can see that the programs did offer courses both to strengthen and intensify the topics/dialogues covered by MOE core courses, and to develop totally new venues for inquiry to reflect the indigenous Chinese-Buddhist

philosophy and thought (see Table 2).

Table 2 Courses in Educational Thoughts and Foundations Educational Thoughts

and Foundation Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses

Philosophy of Education 41 Introduction to

Education 39

MOE suggested electives

Secondary Education 26 History of Education 18 Contemporary thoughts

on education 24 Anthropology of

Education 9

Moral Education 23 Elementary Education 1 Program initiated

electives

Contemporary Issues of

Education 7 Theory and Practice of Affective Education 1 Inquiry of Educational

Problems 5

Principles and Practice of Life-and-Death Education

1

Introduction to

Philosophy 1 Open Education 1

Cultural Philosophy 1 Meditation on Buddhist

Wisdom 1

Theory of Feminism 1 Lectures on Education 1 Educational Thoughts in

the Modern age 1 Selected Classics in

Education 1

Ethics of Education 1 Pedagogy 1

Theory and Practice of

Humanistic Education 1 Inquiry of Taiwan

Education 1

Humanistic Education 1 International

Educational Reform 1 Post-modernism and

Education 1

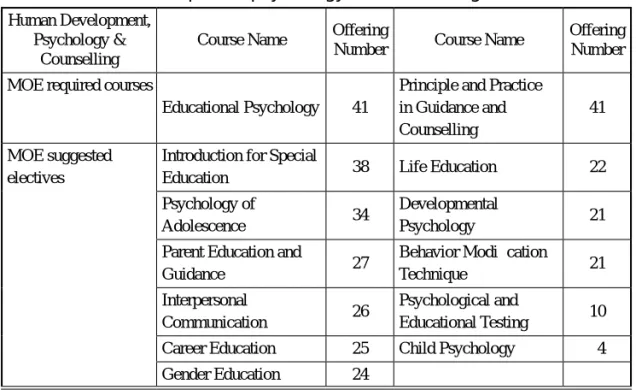

5.3.2 Human development, psychology, and counselling

In the area of “Human development, psychology, & counselling,” the MOE stipulates 2 required courses and 10 suggested courses, concentrating on the general

introduction of educational psychology, human development, student guidance, and education for diverse students’ needs. The teacher programs offered an additional diverse spectrum of 29 courses in this area on more specialized and refined topics, including: 1) various sub-fields of psychology, such as cognitive psychology, social psychology, personality psychology, learning and instructional psychology, abnormal psychology, health psychology, creativity and innovation; 2) human development at various stages, such as adult development, early childhood development, child psychology, adolescent development; 3) guidance and counselling, such as counselling techniques, Gestalt psychotherapy, guidance for at-risk adolescents; and 4) education for students with various types of disabilities, such as mental disabilities, learning disability diagnosis, medial instruction for children with mild disabilities. In this way, the program-initiated courses tend to strengthen and complement the areas/dialogues covered by MOE core courses (see Table 3).

Table 3 Human development, psychology and counselling Human Development,

Psychology &

Counselling

Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses

Educational Psychology 41

Principle and Practice in Guidance and Counselling

41

MOE suggested electives

Introduction for Special

Education 38 Life Education 22

Psychology of

Adolescence 34 Developmental

Psychology 21

Parent Education and

Guidance 27 Behavior Modification

Technique 21

Interpersonal

Communication 26 Psychological and

Educational Testing 10

Career Education 25 Child Psychology 4

Gender Education 24

Human Development, Psychology &

Counselling

Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number Program initiated

electives

Guidance of At-risk

Adolescents 9 Abnormal Psychology 1

Counselling Theory and

Technique 7 Human Intelligence and

Potential 1

Educational and

Vocational Guidance 7

Early Childhood Development and Psychology

1

Health Psychology 6 Youth Development and

Psychology 1

Psychology of Learning 5 Adult Development and

Psychology 1

Adolescent Development and Guidance

5 Theory and Practice of Discipline and Guidance 1

Cognitive Psychology 4

Physical and Mental Development and Guidance

1

Sex Education 3 Instruction for Children Systematic Thinking 1 Learning Disabilities 3 Thinking and Reasoning 1 Psychology and

Education of Child with Special Needs

3 Creativity and

Innovation 1

Group Dynamics 2 Problem-Solving

Strategy 1

Personality Psychology 2 Learning Diagnosis and

Treatment 1

Psychology of

Instruction 1 Mental Disabilities 1

Social Psychology 1

Remedial Instruction for Children with Mild Disabilities

1

Gestalt Psychotherapy 1 Table 3 (continued)

5.3.3 Curriculum, instruction and assessment

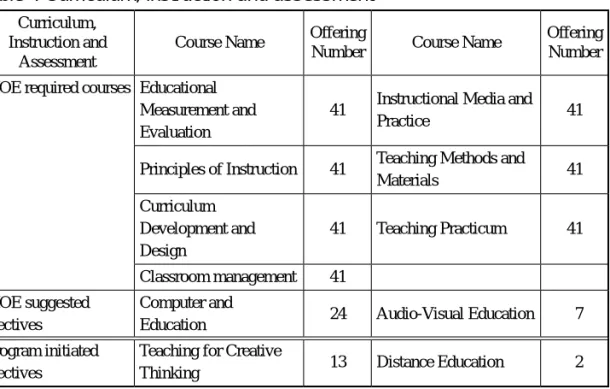

Both MOE and the TE programs appeared to place a great emphasis on the area of

“curriculum, instruction and assessment.” In this area, MOE stipulates seven required courses and two suggested courses, covering the sub-fields of curriculum, instruction, assessment and media instruction, while the teacher programs offered additional diverse spectrum of 32 courses on more specialized and refined topics, covering: 1) curriculum- related courses, including school-based curriculum, curriculum integration, curriculum evaluation, and curriculum reform; 2) instruction-related courses, such as instruction for critical thinking, competency-based instructional design, constructivist instruction, team teaching and instructional supervision; 3) media-related courses, including computer-assisted instruction, multimedia instruction, and distance education. As can be seen, some of the courses opened new avenues for emerging topics/dialogues not covered by MOE core courses, while others tend to add on specialized knowledge to complement the areas/topics in MOE scheme (see Table 4).

Table 4 Curriculum, instruction and assessment Curriculum,

Instruction and Assessment

Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses Educational

Measurement and Evaluation

41 Instructional Media and

Practice 41

Principles of Instruction 41 Teaching Methods and

Materials 41

Curriculum Development and Design

41 Teaching Practicum 41

Classroom management 41 MOE suggested

electives

Computer and

Education 24 Audio-Visual Education 7

Program initiated electives

Teaching for Creative

Thinking 13 Distance Education 2

Curriculum, Instruction and

Assessment

Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number Computer-assisted

Instruction 8 Curriculum Reform 1

Introduction to Nine- Year Integrated Curriculum for Compulsory Education

7 Curriculum Innovation 1

Instructional Design 7 Constructivist in

Instruction 1

Curriculum and

Instruction 5 Instruction of Higher

Order Thinking 1

School-based

Curriculum 5 Instruction of Outdoor

Activities 1

Curriculum Integration 5 Thematic Instruction 1 Computer Network and

Instruction 4 Team Teaching 1

Curriculum Leadership

and Evaluation 3

Introduction to Instructional Technology

1

Instructional

Supervision 3 Competence-based

Instructional Design 1 Compilation of Teaching

Material 2

Seminar on Curriculum, Instruction & Sociology of Technology

1

Instruction for Critical

Thinking 2

Seminar on Curriculum, Instruction &

Philosophy of Technology

1

Multimedia Instruction 2 Evaluation and

Assessment of Science 1 Educational

Communication and Technology

2 Textbook Evaluation 1

Educational Technology 2 Resource Room

Program 1

Table 4 (continued)

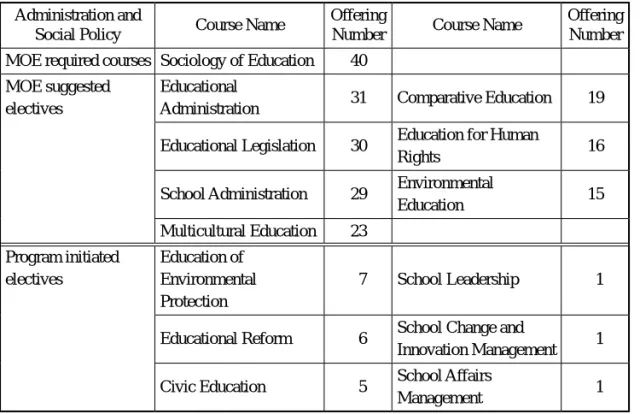

5.3.4 Administration and social policy

In the area of “Administration and social policy,” MOE stipulates only one required course and seven suggested courses covering some of the most important administration and social policy issues, such as educational legislation, school administration, multicultural education and comparative education. In addition, the programs offered an additional diverse spectrum of 24 courses on more specialized and refined topics with the following trends. First, school-based management has become a focal concern in educational administration, as reflected by courses such as school management, school leadership, and school effectiveness. Second, the issue of reform is emphasized with courses such as educational reform and international educational reforms. Third, for educating citizens for the contemporary world, courses including lifelong learning, civic education and environmental protection are provided. And last, education for diverse groups is stressed and provided through courses such as aboriginal education and Southeast Asian Chinese education (see Table 5).

Table 5 Administration and social policy Administration and

Social Policy Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses Sociology of Education 40

MOE suggested electives

Educational

Administration 31 Comparative Education 19 Educational Legislation 30 Education for Human

Rights 16

School Administration 29 Environmental

Education 15

Multicultural Education 23 Program initiated

electives

Education of Environmental Protection

7 School Leadership 1

Educational Reform 6 School Change and

Innovation Management 1 Civic Education 5 School Affairs

1

Administration and

Social Policy Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number Education for Local

Cultures 4 School Effectiveness 1

Organizational Behavior

in Schools 3

Special Subject of Six Main Issues in Taiwan's Education

1

School Education and

Lifelong Learning 3 Culture and Education 1 Service Learning 3 Aboriginal Education 1 Educational Policy in

Nowadays 1 Southeastern Asia

Education 1

International Education

Reforms 1 Education for Southeast

Asian Chinese 1

Policy and Administration in Vocational Education

1 Gender and Intimate

Relationship 1

Study of Issues in

Teacher Education 1 Gender Awareness and

Campus Culture 1

Human Resource Management in Education

1 Marriage and Family 1

Total Quality

Management 1

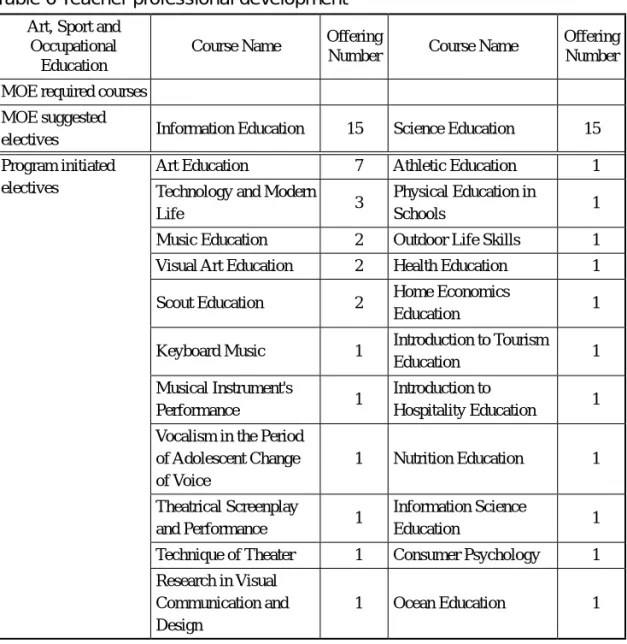

5.3.5 Teacher professional development

In the relatively new and emerging area of “Teacher Professional Education,” the MOE did not stipulate any required courses and only suggested two elective courses focusing solely on research methodology. However, the teacher education programs did manage to put forward a multitude of 17 courses in the following three aspects. First, courses aimed to train a variety of competencies and skills for teachers, including: oral communication, Chinese literacy, blackboard calligraphy, English conversation, and teaching portfolio to enhance future teachers’ instructional capacities. Furthermore, Table 5 (continued)

methodology courses including case study methods, qualitative research, and action research were offered to hone future teachers’ research skills for ongoing inquiry and improvement. Finally, courses such as teacher professional development, teacher career development, and mental health for teachers were offered to help prospective teachers prepare for a well-adaptive and productive professional career. All the courses in this area touched upon new fields of knowledge not covered by MOE core curriculum (see Table 6).

Table 6 Teacher professional development Art, Sport and

Occupational Education

Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses

MOE suggested

electives Information Education 15 Science Education 15

Program initiated electives

Art Education 7 Athletic Education 1

Technology and Modern

Life 3 Physical Education in

Schools 1

Music Education 2 Outdoor Life Skills 1 Visual Art Education 2 Health Education 1 Scout Education 2 Home Economics

Education 1

Keyboard Music 1 Introduction to Tourism

Education 1

Musical Instrument's

Performance 1 Introduction to

Hospitality Education 1 Vocalism in the Period

of Adolescent Change of Voice

1 Nutrition Education 1

Theatrical Screenplay

and Performance 1 Information Science

Education 1

Technique of Theater 1 Consumer Psychology 1 Research in Visual

Communication and 1 Ocean Education 1

5.3.6 Education for specialized areas

Finally, there were some courses for certain specialized areas such as art, athletics, vocational and technological education. As the MOE tends to place more emphasis on general courses that may apply to all types of teacher education programs, courses in those specialized areas were relatively neglected. That’s why in the area of “Education for specialized areas,” MOE stipulated no required courses and only suggested two electives (educational research methodology and educational statistics). However, teacher education programs specializing in these areas did manage to provide a wide spectrum of 23 courses to highlight their own special goals and functions. Programs specializing in art education offered courses such as art education, music education, theatrical screenplays and performance, visual communication, and design education;

programs specializing in athletic education provided courses in athletic education, scout education, and physical education in schools; programs for vocational/

technological education provided courses in tourism education, consumer psychology, nutrition education, home economics, and information science education. This variety of courses appears to be intended to hone students’ knowledge and skills in teaching various occupational subjects in the future (see Table 7).

Table 7 Specialized fields in art, athletic and vocational education Teacher Professional

Development Course Name Offering

Number Course Name Offering Number MOE required courses

MOE suggested electives

Educational Research

Methodology 29 Educational Statistics 26

Program initiated electives

Action Research 9 Crisis Management 2

Mental Health for

Teachers 7 EQ Education for

Teachers 2

Teacher Professional

Development 6 Qualitative Research 2

Oral Communication 5 Classroom Observation

and Research 1